To achieve the objectives of this research, extensive literature reviews (using Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) were conducted to assemble the relevant quantitative and qualitative data. Subsection 2.1 highlights the key findings of the literature reviews. The collated information was mapped to specific decision criteria that support the comparative assessment. In addition, the steam-methane reforming (SMR) technology, with and without carbon capture and storage (CCS), was used as the benchmark H2 production technology. The employed decision criteria are detailed in subsection 2.2, while Subsection 2.3 provides an overview of the evaluated H₂ production technologies.

2.1. Literature Reviews and Key Findings

As an introduction to this subsection, it is worth noting that by 2050, the global energy demand is anticipated to be around 30 terawatts (TW), which is double that of 2011 [5]. Hydrogen is specifically being considered as an alternative fuel in the transportation sector to power fuel cell electric vehicles [6] and for electrifying the commercial aviation (viz., the hybrid-electric and all-electric aircraft). The U.S. DOE projected that clean H2 could be produced for $2/kg H2 by 2025 (H2New, 2021)1 and in its 2021 ‘Hydrogen Shot’ Summit, DOE drafted its long-term goal to reduce the cost of clean H2 production to $1 per kg H2 in 1 decade (Hydrogen Shot, 2021).[2]

Herein, a literature review of 102 published sources was conducted on various H2-producing technologies, specifically the most prominent conventional technologies and the most promising greener technologies. With a couple exceptions, only papers and reports published in the last decade (2013-2024) were consulted, with an effort to rely on publications from the past 5 years whenever possible, in order to ensure the comparative analysis contained the most updated information. From these sources, both quantitative and qualitative data was extracted to support the comparative assessment of H2 production technologies.

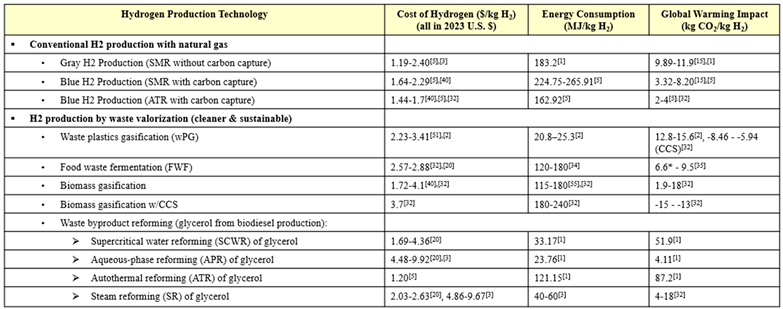

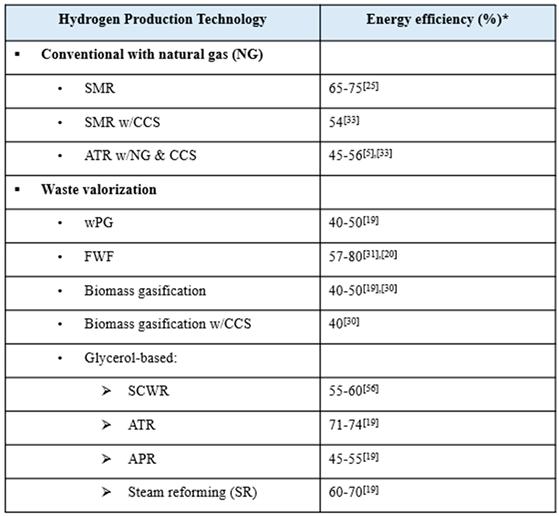

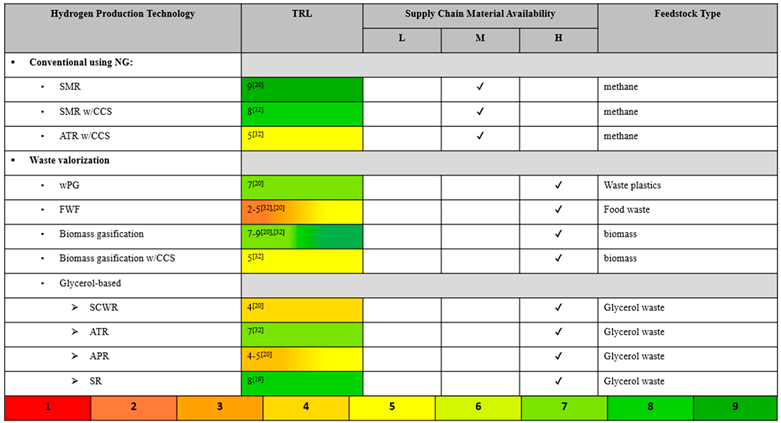

The conventional methods of H2 production provide either ‘gray’ or ‘blue’ hydrogen. Steam- methane reforming (SMR) is widely acknowledged as the most well-established method [3], and it is often used as a point of reference to analyze and compare the performance and feasibility of the none conventional methods. Because SMR is a very mature technology, it is thoroughly studied and producing low-cost hydrogen, but it also has low potential for technical improvements that will improve efficiency or performance [7,8]. Several papers studying the conventional methods of producing blue H2 discuss how CCS reduces emissions significantly, but also increases production cost and decreases energy efficiency [8,9,10,11,12].

Waste valorization was evaluated as a more sustainable H2 production technology. Utilizing waste streams eliminates both the polluting effects of waste build-up and the need for energy-intensive and high-emitting waste incineration. Biomass is a broad term that can be prepared as a feedstock from organic sources, such as grass, wood, agricultural products, animal waste, food scraps, municipal solid waste, and algae, and it can be valorized by methods, such as gasification, pyrolysis, supercritical water gasification, and dark fermentation [11,13]. One study noted that food waste is specifically suitable for H2 production for a number of reasons, such as its carbohydrate richness, wide availability, and low cost [14]. Another study explained that converting food waste to H2 via dark fermentation is energetically advantageous because it can be achieved under ambient temperature and pressure with low chemical energy requirements, but it must be performed onsite to be feasible due to the high-water content and biodegradability of food waste [15]. Even more so than food waste fermentation, gasification of biomass is a highly studied process due to its convenient utilization of diverse waste streams and production of clean biohydrogen. Biomass gasification is currently faced with low conversion and thermal efficiencies, but they can be improved with the optimization of the process temperature, the catalyst used, and the biomass content [16].

Glycerol is another promising waste stream to utilize for H2 generation, as it is produced abundantly as a byproduct of the transesterification of biomass to biodiesel. By strategically incorporating H2 production plants into existing biodiesel production plants, glycerol could even become a free material stream. A simulation-based life cycle assessment (LCA) compared the environmental and health impacts of several glycerol-based hydrogen production technologies–ATR, APR, and SCWR–versus those of the conventional method of SMR [17]. A techno-economic analysis (TEA) compared the cost of hydrogen produced from APR and steam reforming of glycerol, revealing that APR is slightly less expensive but still not competitive with SMR [18]. Another report on pathways to produce H2 from biomass provided H2 production costs and TRLs of SCWR, APR, and SR of glycerol [16].

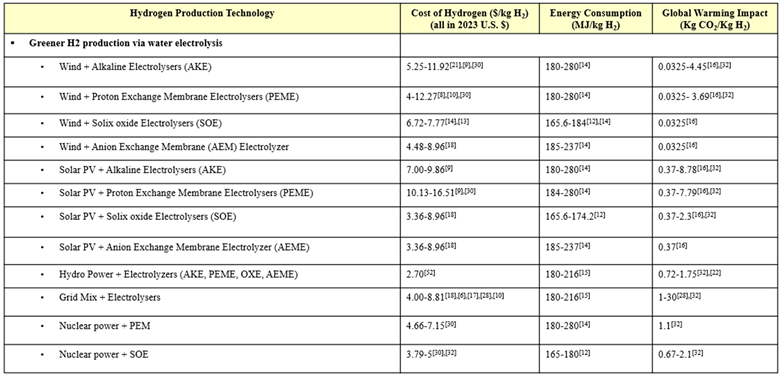

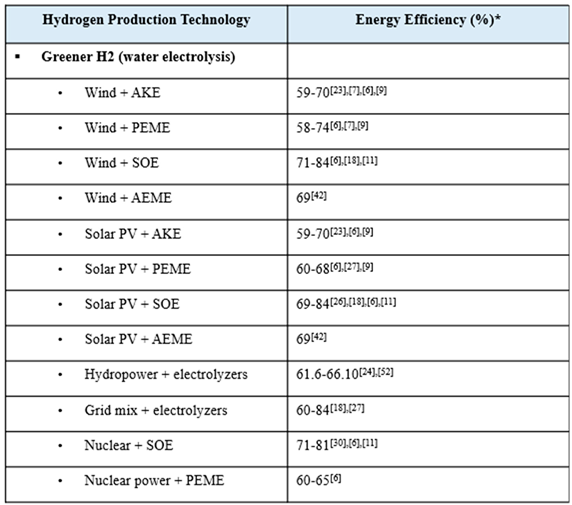

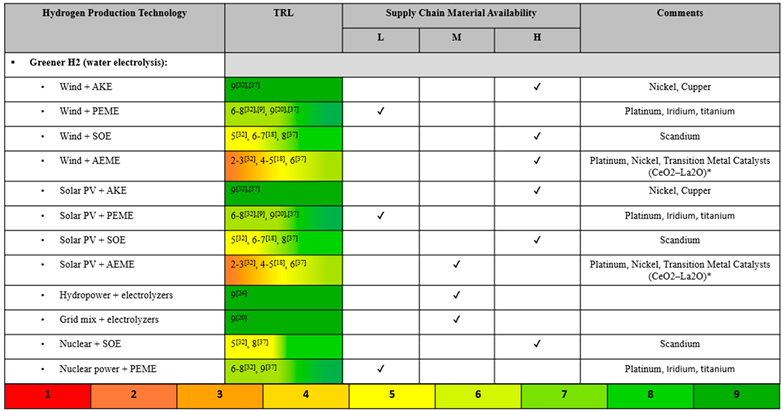

Water electrolysis is widely considered a promising method of sustainably producing H2 due to fairly negligent carbon emissions [19,20,21]. A number of sources compared powering electrolyzers with the local electricity grid mix versus renewables. Because the grid mix varies so widely, a wide range of H2 cost values were reported, but in general, it is agreed that costs could be reduced by strategically utilizing renewable power sources rather than relying on the grid mix [22,23,24,25,26]. Research has recently explored utilizing wind power and solar PV power to produce green H2 by electrolysis [20]. While discussed to a lesser extent, other renewables like hydropower and nuclear power are also contenders for more sustainable electrolysis power sources [27,28,29]. While hydropower is a well-established renewable electricity source, one report noted that it will be overtaken by solar PV power due to its lower levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) and higher energy capacity [30]. Nuclear energy is also a firmly established renewable energy source, but still setbacks such as social apprehension keep it from becoming the focus of green H2 research [28]. Different renewable energy sources make more sense for different areas, depending on what natural resources are most abundant and consistent in a given region [25]. Therefore, cost and energy efficiency analyses [31] are further complicated with the additional variable of energy source.

The TRL of water electrolysis varies depending on the technology and the energy source utilized. However, as explored in a variety of reports, electrolysis is a fairly well-developed technology, particularly AKE, PEM, and SOE more so than AEM [9,16,22,32,33,34,35]. In addition to its nearly negligible global warming impact, its high TRL makes electrolysis an attractive green H2 production technology. However, high H2 production costs and high energy requirements are setbacks that are keeping electrolysis from replacing the conventional methods. One paper noted that despite its low GWP and high technological readiness, solar PV-powered electrolysis will only be able to take the forefront as a potential option for H2 production when its energy efficiency is improved, which will also subsequently lower its high production costs [5,36].

Electrolyzers are oftentimes divided into two classes: low-temperature electrolyzers (LTEs) and high-temperature electrolyzers (HTEs). The U.S. DOE has invested R&D funding into these two types of electrolysis in order to promote the most durable, effective, and efficient system of green H2 production. The characteristics of LTE, such as PEM, is that it is commercially available, but it isn’t durable, efficient, or affordable enough, while the characteristics of HTE, such as SOE, is that it is less mature, but has potential for higher efficiency and a longer lifespan [37]. According to one paper, SOEs are advantageous because of their ability to co-electrolyze steam and carbon dioxide in a single step and, thus, eliminating the need for an expensive and maintenance-intensive water-gas shift reactors [38]. SOEs operate at high temperatures, meaning they require greater energy input, but also that they can utilize low-cost active metals rather than expensive noble metals [38]. The Global Hydrogen Review claims that AEME electrolysis combines the benefits of PEME and AKE, since it does not require expensive platinum utilized by PEME nor the corrosive electrolyte used in AKE, but it is a less mature technology [22].

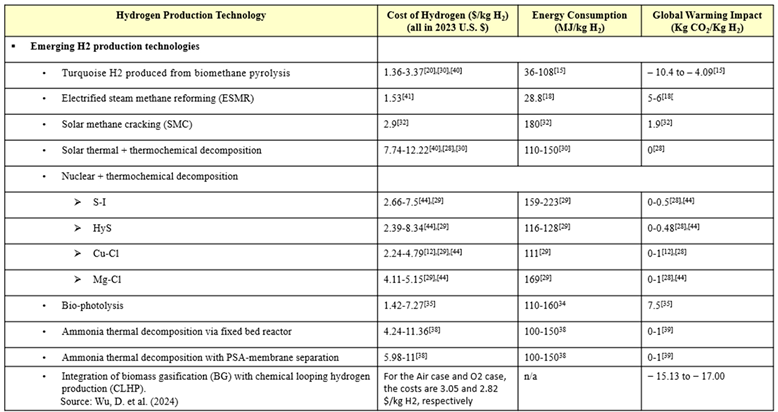

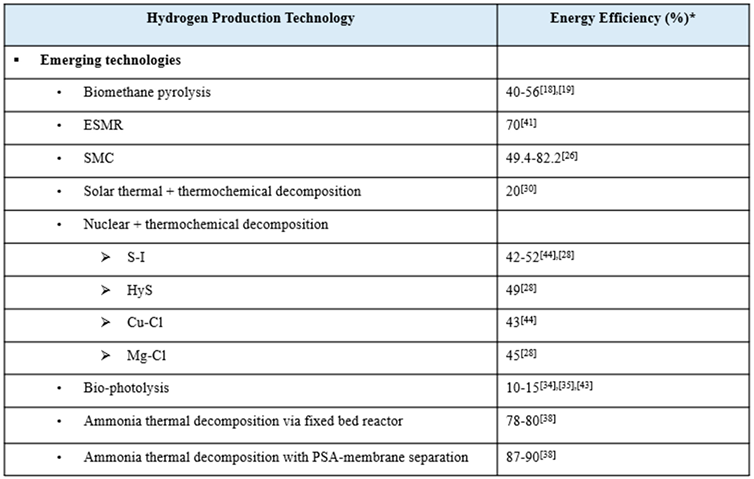

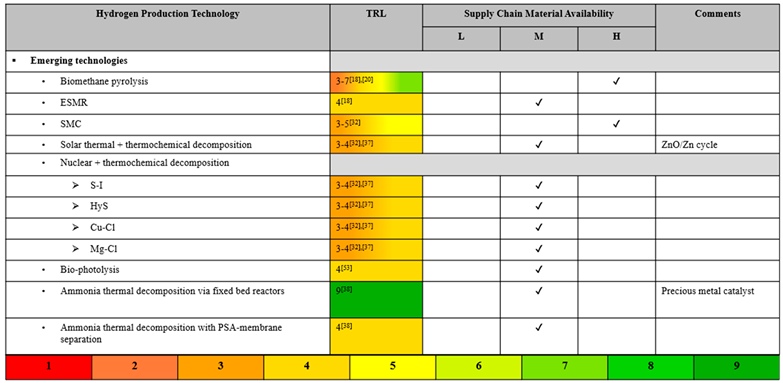

Emerging technologies for clean H2 production are also evaluated in this research. Because of the novelty of these technologies, they will not have very high TRLs, with most still being in the research and early development stages [16,22,39]. Several studies of thermochemical decomposition via both solar and nuclear power demonstrate that these technologies are far from being commercially mature [9,34]. However, even though the technologies are immature, their TEA reveal that several of the emerging technologies, like bio-photolysis, biomethane pyrolysis. and ESMR, are potentially able to produce H2 for competitive prices [11,28,40,41]. ESMR is especially attractive when considered as an easily implemented technology to help aid in the transition from gray to cleaner H2. It utilizes the same natural gas feedstock, but incorporates renewable electricity to lower emissions, resulting in a system that is more sustainable than the conventional methods and more economically and technically feasible than the other emerging technologies [41]. Among the emerging H2 production technologies is the so-called white color, from natural origin, however due to its rare occurrence in the Earth’s rock, there is no commercial interest at this point in time [42]. This geologic H2 (aka., white, gold, or natural H2) is found beneath Earth’s surface and is postulated to be produced by high-temperature reactions between water and iron-rich minerals.[3]

Most of the other emerging technologies still require more technological development to compete with the standard hydrogen prices [24,43]. Strategic plant optimization can help lower production costs. For example, H2 costs from ammonia thermal decomposition via fixed bed reactors and PSA-membranes are expected to decrease if plants are built to be larger and centralized, which would lead to economies of scale and less expensive ammonia costs [44,45]. One article discussed how the fluctuations in H2 production costs via thermochemical processes are mainly due to variable electricity prices, but the utilization of reliable green electricity from renewable sources like solar PV and wind turbines can greatly reduce production costs [11]. The lack of comprehensive studies of promising emerging technology, like biomethane pyrolysis and SMC, has been called out and discussed. These turquoise-H2 producing technologies [46] are preferable to SMR due to lower emissions and energy requirements, but still the information on them is sparse and the data is often conflicting and inconsistent [47]. There tends to be a disproportionate focus on green-H2 production technologies, particularly water electrolysis, despite other promising candidates. Further analysis of these emerging technologies will open up a slew of diverse avenues for clean hydrogen production.

Another reason to invest more resources in a wider range of promising clean H2 production technologies is their potential to be combined and integrated into hybrid systems. This integration process can strategically lower H2 production cost, decrease energy requirements and carbon emissions, increase efficiency, and utilize waste to make useful products. A well-established example of technology integration is the addition of CCS to gray H2 production technology, a method that succeeds in reducing emissions, but also tends to increase production cost and energy consumption, while reducing process efficiency [7,8,10,17,47]. More technically advanced and economically and energetically efficient combinations can be devised. One paper performed an energy analysis of an integrated system with SMC and SOE for the production of turquoise H2 and clean methanol [38]. Another paper examined hybrid wind and solar PV energy systems, finding that the combination of power sources meets the load demand and minimizes emissions and system costs [48]. A study reported that the energy output of FWF can be increased by 7-9 times with a 2-stage fermentation process that results in H2 produced via dark fermentation and methane produced via anaerobic digestion [15]. This methane could then be utilized as renewable natural gas to be injected into the existing natural grid infrastructure.

2.3. Hydrogen Production Technologies Being Evaluated

The production technologies being evaluated are as follows:

- ▪

Conventional via steam-methane reforming (SMR)

The conventional method for H2 production is steam-methane reforming (SMR), which accounts for around 50% of H2 production [5]. This method converts natural gas (primarily methane) and steam to H2 and carbon CO2, a byproduct which contributes to global warming. The second conventional method of producing gray hydrogen is coal gasification, but it is not included in this research because it is less common than SMR. Autothermal reforming (ATR) of natural gas in yet another conventional technology for H2 production. ATR is similar to SMR in that it produces H2 and CO2 but it has the advantage of producing more exothermic from the partial oxidation that occur in the [8]. The produced H2 from SMR, coal gasification, ATR is denoted as ‘gray’ H2. Integration of carbon capture and storage (CCS) with any of these conventional technologies produces the so-called ‘blue’ H2. While integration with CCS results in CO2 emission reduction, both production cost and energy consumption are shown to increase compared to the case without CCS.

- ▪

Hydrogen production by waste valorization

The utilization of various waste streams for hydrogen production is examined in food waste fermentation (FWF), waste plastics gasification (wPG), and biomass gasification with and without CCS. The valorization of biodegradable food waste by dark fermentation, can help alleviate the waste management crisis and reduce the production of carbon emissions and toxic pollutants in overcrowded landfills, while also producing more eco-friendly H2 [49,50,51]. Data-driven interpretation, comparison and optimization of H2 production from supercritical water gasification of biomass. Gasification is the high temperature partial oxidation of waste feedstocks, like plastics or biomass, to produces syngas, which is a mixture of CO and H2. Syngas can be further converted to make other useful chemicals using the Fischer–Tropsch (FT) process or combusted to generate steam for electricity generation [52].

- ▪

Waste byproduct reforming (glycerol from biodiesel production)

A promising waste stream to utilize for H2 production is the glycerol byproduct that results from biodiesel production via the transesterification of agricultural crops [17]. The technologies studied that convert glycerol into hydrogen are supercritical water reforming (SCWR), aqueous-phase reforming (APR), autothermal reforming, and steam reforming (SR).

- ▪

Greener hydrogen production via water electrolysis

The water electrolysis technologies considered herein are alkaline electrolyzer (AKE), proton exchange membrane electrolyzer (PEME), anion exchange membrane electrolyzer (AEME), and solid oxide electrolyzer (SOE) via solar photovoltaic (PV) power, wind power, hydropower, grid mix electricity, and nuclear power. Hydrogen produced via water electrolysis with renewable energy is called green H2 and is characterized by its low global warming impact. Electrolysis powered by grid mix electricity does not produce green H2, but it benefits from utilizing the current electricity grid. The US grid electricity mix is roughly as follows: 38% natural gas, 17% coal, 20% nuclear, 11% wind, 7% hydropower, 5% solar, and 2% other [53].

- ▪

Emerging hydrogen production technologies

Various emerging clean H2 production technologies were evaluated in this comparative analysis. The high-temperature processes biomethane pyrolysis and solar methane cracking (SMC) produce the so-denoted ‘turquoise’ H2 and carbon-black. SMC utilizes concentrated solar energy to power the high-temperature process, resulting in even cleaner hydrogen [38]. Biophotolysis, electrified steam-methane reforming (ESMR), and ammonia (NH3) thermal decomposition via fixed-bed reactor and via PSA-membrane technology were also evaluated in this research. Biophotolysis utilizes sunlight energy to convert water to hydrogen through biological systems [40]. ESMR combines traditional SMR with renewable electricity. Both solar thermal powered thermochemical decomposition of water and nuclear-powered thermochemical decomposition of water were researched. There are many variations in nuclear-powered thermochemical decomposition, but only four of the most promising cycles were included in this study. These are the three-step sulfur-iodine (S-I) cycle, the two-step hybrid sulfur (HyS) cycle, the four-step copper-chlorine (Cu-Cl) cycle, and the three-step magnesium-chlorine (Mg-Cl) cycle.