1. Introduction

Globally, energy consumption is continuously increasing in tandem with economic and population growth, leading to severe environmental problems. In particular, the fossil fuel-centric energy system has been identified as a primary contributor to global warming and climate change due to its substantial emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) [

1]. Against this backdrop, the transition to a sustainable energy system has emerged as a global imperative, with hydrogen garnering significant attention as a key clean energy carrier for achieving a carbon-neutral society. Currently, the majority of commercially produced hydrogen relies on Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) of natural gas; however, this process is constrained by its significant carbon dioxide emissions [

2]. Consequently, there is a pressing need for the development of eco-friendly hydrogen production technologies that can minimize carbon emissions. Among these alternatives, Waste-to-Energy (WtE) technologies, which produce hydrogen from waste resources, are gaining prominence. WtE technologies transcend simple waste disposal by utilizing waste as an energy source, thereby offering the potential to simultaneously address environmental issues and secure energy resources [

3,

4].

Among the WtE technologies, gasification is a thermochemical conversion process that transforms solid waste into synthesis gas (syngas)—composed mainly of hydrogen (H

2) and carbon monoxide (CO)—through pyrolysis at high temperatures under oxygen-limited conditions [

5]. This syngas can be converted into high-purity hydrogen through a reforming process, used as a feedstock for various chemical products such as methanol and ammonia, or utilized for electricity generation. In this respect, gasification technology is evaluated as a key technology that can contribute to establishing a circular economy [

6]. While waste gasification is emerging as a promising alternative for hydrogen production, its commercialization and widespread adoption necessitate an objective and quantitative assessment of its environmental sustainability.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for holistically evaluating the potential environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal. By applying LCA to waste gasification, it is possible to identify the technology’s environmental strengths and weaknesses, derive strategies for improvement, and provide an evidentiary basis for promoting its adoption in pursuit of carbon neutrality. To date, numerous LCA studies have been conducted on hydrogen production via gasification using various feedstocks, such as biomass, municipal solid waste, and plastic waste. Kalinci et al. [

7] performed an LCA of hydrogen production from biomass gasification (downdraft and circulating fluidized bed) to evaluate fossil energy consumption and GHG emissions, proposing a Coefficient of Hydrogen Production Performance (CHPP). Muresan et al. [

8] compared dual fluidized bed biomass gasification with entrained flow coal/biomass co-gasification, analyzing their Global Warming Potential (GWP). Hajjaji et al. [

9] reported that hydrogen production from biogas reforming resulted in GHG emissions approximately half that of the conventional SMR process. Chari et al. [

10] conducted a detailed LCA of a semi-commercial hydrogen production process combining mixed plastic waste (MPW) gasification with 90% carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the UK. Borges et al. [

11] performed a comprehensive technical, economic, and environmental assessment of hydrogen production from biomass gasification, reporting a GWP range of -0.5 to 8.0 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2, significantly lower than that of natural gas reforming (average 11.88 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2), and identified the fluidized bed gasifier as the most practical technology.

Recently, LCA research has actively explored various waste types and utilization pathways, including hydrogen and methanol production from plastic waste gasification, agricultural residue gasification, and comparisons between municipal solid waste gasification and landfilling. These studies demonstrate that environmental impacts can vary significantly depending on the feedstock type, gasification technology, system boundary definition, and the electricity mix utilized [

12,

13]. However, there is a notable scarcity of in-depth LCA studies on the entire process of hydrogen production from the gasification of high-calorific mixed waste based on operational data from actual pilot-scale plants tailored to the domestic context in South Korea. Pilot-scale research is crucial as it bridges the gap between laboratory-scale studies and commercial-scale plants, enabling a more realistic environmental assessment by reflecting the various parameters and efficiencies encountered during actual operation. Furthermore, predicting environmental impacts and identifying areas for improvement by scaling up from pilot plant data is essential for formulating commercialization strategies.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of a hydrogen production system based on the actual design and operational data from a 2 TPD pilot plant for high-calorific mixed waste gasification. Specifically, the LCA model encompasses the processes from waste feeding to gasification, cleaning, reforming (water-gas shift reaction), and final hydrogen separation (PSA). The objectives of this research are to identify the system’s environmental hotspots based on the results, predict the environmental impact at a larger scale (40 TPD), and conduct a comparative analysis of its GWP against other hydrogen production technologies. Through this, we seek to validate the environmental feasibility of hydrogen production via high-calorific mixed waste gasification and contribute to future technology development and policy formulation.

2. Methods

2.1. System Description: Gasification Pilot Plant and Process

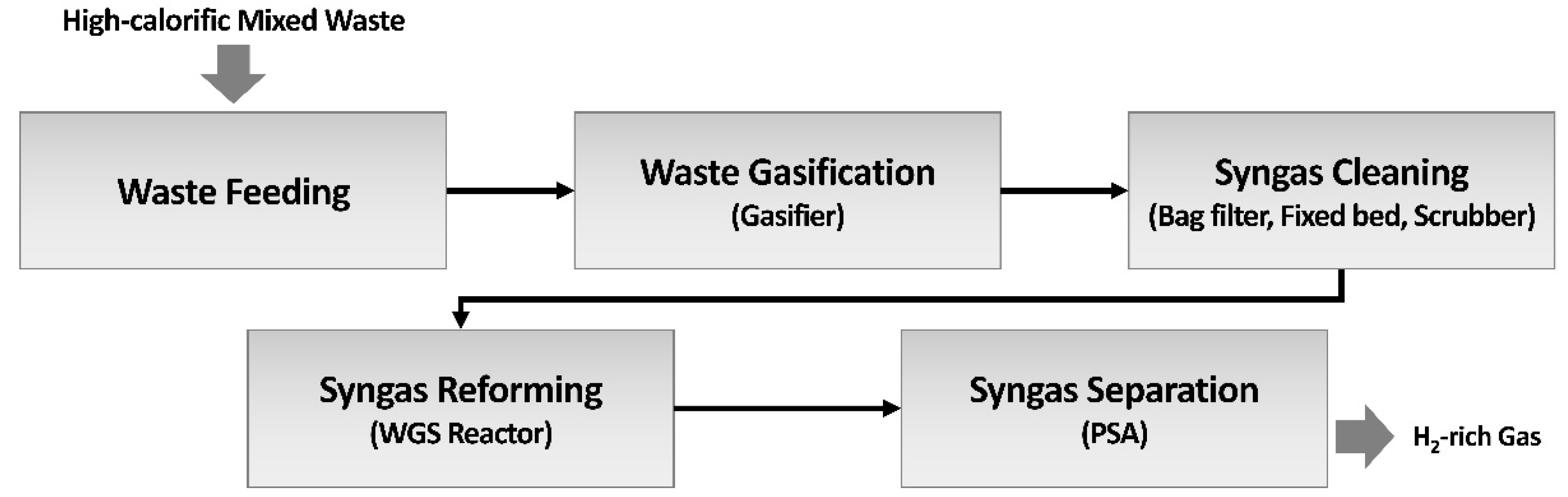

The system under investigation in this study is based on a pilot-scale gasification plant with a processing capacity of 2 tons per day (TPD), designed and operated to produce hydrogen-rich syngas from high-calorific mixed waste. The entire system is composed of sequential process stages, from waste feeding to the final hydrogen separation step, configured to maximize hydrogen yield and purity. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the integrated process consists of (1) a waste feeding system, (2) a gasifier, (3) a syngas cleaning system, (4) a syngas reforming system, and (5) a virtually applied Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) system for hydrogen separation. Collected high-calorific mixed waste is converted into syngas in the gasification reactor, which then undergoes dust removal, desulfurization, and dechlorination in the cleaning system. The purified syngas is reformed into an H

2-rich gas in the reforming system (Water-Gas Shift), and finally, the PSA unit separates high-purity hydrogen of over 99.9%. Process simulations based on heat and mass balance calculations were conducted to determine the design specifications for each unit, leading to the construction of the 2 TPD-class gasifier and hydrogen production pilot plant.

2.1.1. Waste Feeding

To select the feedstock for gasification, three types of mixed waste were collected: waste from a Refuse-Derived Fuel (RPF) manufacturing process, containing various materials like synthetic resins, paper, and wood; Automotive Shredder Residue (ASR); and incinerator feed waste. For optimal thermal efficiency in the gasification process, it is crucial to use waste with a high calorific value and a low ash content [

14]. Elemental and calorific value analyses were performed to measure the moisture, ash, elemental composition, and heating value of each waste type (

Table 1). Among the three candidates, the waste from the RPF manufacturing process was ultimately selected as the feedstock for this study, as it exhibited the highest calorific value and the lowest ash content. The collected waste undergoes crushing to ensure smooth feeding into the gasifier.

2.1.2. Gasification

The primary objective of the waste gasification process is to convert the solid waste into a combustible gaseous fuel with a high conversion efficiency. The collected and pre-treated high-calorific waste is fed into the gasifier via a constant-rate feeding system to ensure stable operation. Inside the gasifier, the waste undergoes a series of thermochemical reactions at high temperatures, ranging from 800 to 1,200°C, under oxygen-limited conditions. The carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) components in the feedstock undergo various reactions, including combustion (

Table 2), and are converted into a primary syngas composed of CO, H

2, CO

2, and HCl [

15].

The gasifier was designed based on the reaction kinetics and process simulation results. A fixed-bed reactor was employed due to its flexibility with varying waste shapes and minimal pretreatment requirements [

16]. The designed operating conditions for the gasifier are a waste feed rate of 2 tons/d, an oxygen supply rate of 1,700 Nm

3/d, and a temperature of 1,100°C. During the initial start-up, an auxiliary fuel (LPG) was used to raise the gasifier temperature. Once stabilized, the temperature was maintained by adjusting the waste feed rate

2.1.3. Syngas Cleaning

The high-temperature syngas produced in the gasifier contains various impurities that can cause corrosion of downstream equipment or catalyst deactivation [

17,

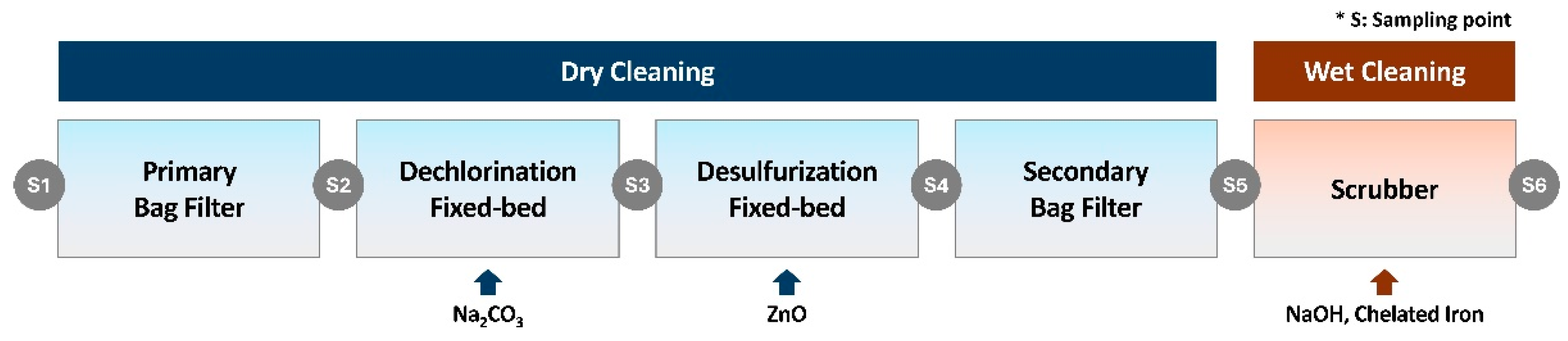

18]. Therefore, a cleaning system was implemented to maximize the efficiency of the subsequent catalytic reforming and separation processes. The cleaning system consists of a high-temperature dry-cleaning system and a low-temperature wet-cleaning system, installed sequentially (

Figure 2).

The dry high-temperature cleaning system was configured to remove high concentrations of pollutants (dust, HCl, H

2S) from the syngas and comprises a primary bag filter, a dechlorination fixed-bed reactor, a desulfurization fixed-bed reactor, and a secondary bag filter. The process begins with cooling the syngas to approximately 600°C using a cooler, followed by the physical removal of particulate matter (e.g., dust, ash) with a ceramic filter. The gas then sequentially passes through reactors packed with dry sorbents to remove acid gases (HCl, H

2S). Sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3), which demonstrates excellent hydrogen chloride removal performance without requiring special processing, was used in the dechlorination reactor. For the desulfurization reactor, zinc oxide was utilized due to its superior removal efficiency compared to iron-based desulfurizing agents (Fe

2O

3, Fe

3O

4) [

19,

20,

21]. To prevent catalyst deactivation in the WGS reactor and ensure high-purity hydrogen production in the PSA unit, trace impurities remaining after the dry high-temperature cleaning were removed using a wet low-temperature cleaning system. This wet system consists of a rapid cooler (quencher) to prevent dioxin synthesis and a wet scrubber for pollutant removal [

22,

23]. In the wet scrubber, not only water but also NaOH and chelated iron were injected for dechlorination and desulfurization, respectively.

2.1.4. Syngas Reforming

The purified syngas is transferred to the reforming system to achieve a composition optimized for hydrogen production. The core process in this stage is the Water-Gas Shift (WGS) reaction (CO + H

2O ↔ CO

2 + H

2), which was carried out in a fixed-bed reactor. The primary purpose of the WGS reaction is to reduce the concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) while simultaneously increasing the concentration of hydrogen (H

2) in the syngas, thereby adjusting the H

2/CO molar ratio to be suitable for the final product synthesis. A commercial Fe

2O

3-based catalyst, known for its thermal stability and poison resistance, was used for the reforming reaction. To maintain a high CO conversion rate, the reactor was operated at a steam/CO ratio of 2.0–2.5 and a reaction temperature of 400–450°C [

24,

25,

26]. The steam was self-supplied, generated using energy recovered from the syngas produced in the gasifier.

2.1.5. Hydrogen Separation

For the final separation of hydrogen, a Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) system was virtually applied to the process model in this study. The syngas, enriched with hydrogen and carbon dioxide after passing through the WGS reactor, is fed into the PSA unit. This process produces a high-purity hydrogen product by utilizing pressure changes to selectively adsorb impurities (e.g., CO

2, CH

4, residual CO) onto a sorbent material, thereby separating the hydrogen. PSA typically separates hydrogen with a recovery rate of 85–90% and a purity of 99.99% [

27,

28,

29]. In this study, the virtual application of PSA post-syngas reforming assumed a hydrogen separation with a recovery rate of 85% and a purity of 99.99%. It was also assumed that the separated off-gas was captured separately rather than being vented to the atmosphere.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of a product throughout its entire life cycle (from cradle to grave). The life cycle encompasses all stages from raw material acquisition to production, use, and end-of-life (EoL), and the system boundaries can be adjusted according to the scope of the study. The international standards ISO 14040 and 14044 define the framework for LCA in four phases: (1) Goal and Scope Definition, (2) Life Cycle Inventory Analysis, (3) Life Cycle Impact Assessment, and (4) Interpretation [

30]. In this study, an LCA was conducted following this framework to quantitatively assess the potential environmental impacts of a hydrogen production system based on high-calorific mixed waste gasification.

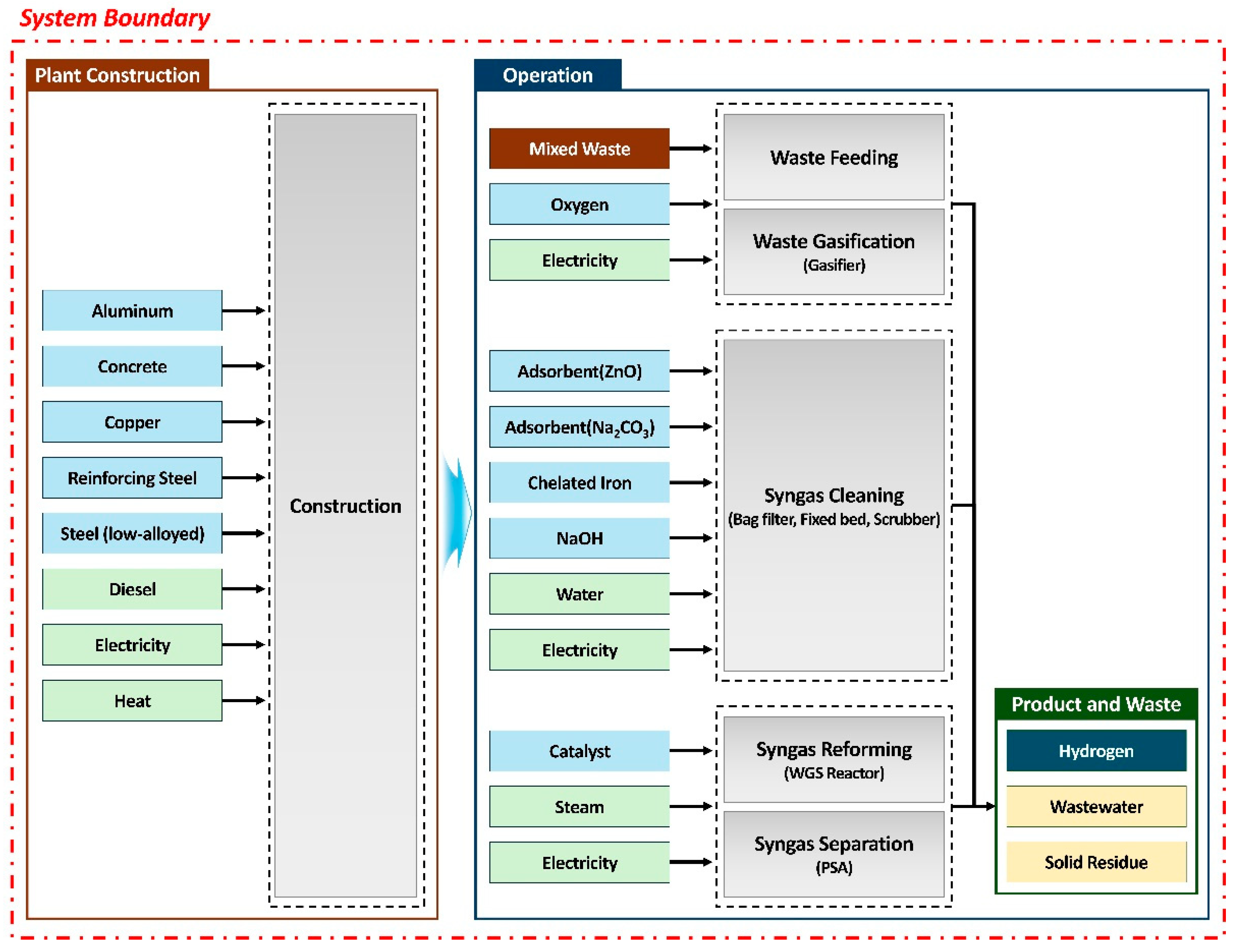

2.2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The primary goal of the LCA in this study is to identify the environmental hotspots that arise throughout the life cycle of the hydrogen production system via high-calorific mixed waste gasification. Furthermore, this study aims to ascertain the environmental positioning of the system by comparing its environmental impact results with those of existing hydrogen production technologies (e.g., coal gasification, methane reforming). The functional unit for this analysis was defined as 1 kg of produced hydrogen. The system boundary encompasses a “cradle-to-gate” perspective, including the processes from waste collection and sorting to final hydrogen production (

Figure 3). The system boundary includes not only the operational phase of the plant—comprising gasification, syngas cleaning, reforming, and separation—but also the plant construction phase.

2.2.2. Inventory Data Acquisition and Impact Assessment

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) analysis is a critical phase of an LCA, involving the collection of data on all inputs and outputs required to produce the functional unit [

31]. In this study, operational data, including materials and utilities for the main processes, were established based on actual operational data from the 2 TPD pilot plant. Although the operational data originated from the 2 TPD pilot plant, the construction data were established using data for a syngas production plant from the Ecoinvent database, representing a 40 TPD scale, to facilitate comparison with other commercialized hydrogen production technologies. The collected data were quantified for the functional unit assuming a plant lifespan of 20 years and 8,000 annual operating hours, based on the total amount of hydrogen produced during this period. Data for background processes, such as electricity generation and raw material production, were sourced from the Ecoinvent v3.11 database.

To calculate the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from hydrogen production via high-calorific mixed waste gasification, the environmental impacts were assessed using the GaBi software. The CML methodology, developed by Leiden University in the Netherlands, was employed for the impact assessment. The scope of the assessment was focused on the Global Warming Potential (GWP), which is associated with the increase in the Earth’s average temperature caused by greenhouse gases such as CO2, CH4, and N2O. The environmental impact calculation included materials input into the plant, waste generated during the hydrogen production process, and plant construction. Steam was excluded from the environmental impact assessment as it was produced and utilized internally within the plant.

3. Results

3.1. Performance of the Gasification Plant

Continuous operation of the 2 TPD pilot gasification plant was conducted to verify its performance and hydrogen production rate. As illustrated in

Figure 1, hydrogen was produced from the residual waste of the RPF manufacturing process through sequential stages of gasification, syngas cleaning, syngas reforming, and syngas separation. The waste feed rate into the gasifier was approximately 2 ton/d, and the oxidant (oxygen) was supplied at a rate of approximately 1,700 Nm

3/d. The average composition of the syngas generated after the gasification reaction was found to be 24.78% hydrogen, 38.78% carbon monoxide, and 33.40% carbon dioxide (

Table 4).

To determine the purification efficiency of contaminants in the syngas, sampling was performed at the inlet and outlet of each unit within the cleaning process. A total of six sampling points were established: the syngas inlet (S1), downstream of the primary bag filter (S2), downstream of the dechlorination fixed-bed reactor (S3), downstream of the desulfurization fixed-bed reactor (S4), downstream of the secondary bag filter (S5), and downstream of the wet scrubber (S6) (

Figure 2). The parameters measured to verify cleaning efficiency were dust, HCl, and H

2S. The sampling results indicated a removal efficiency exceeding 99.99% for all contaminants (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Pollutant concentrations at different stages of the cleaning system.

Table 3.

Pollutant concentrations at different stages of the cleaning system.

| |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S6 |

| Dust(mg/Nm3) |

36922.66 |

4351.21 |

- |

- |

7.20 |

< 0.001 |

| HCl(ppm) |

170.21 |

- |

21.99 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| H2S(ppm) |

1050.27 |

- |

822.75 |

0.23 |

0.05 |

ND |

Table 4.

Syngas composition at different process stages.

Table 4.

Syngas composition at different process stages.

| |

After Gasifier |

After WGS |

After PSA |

| H2(vol%) |

24.78 |

38.93 |

99.99 |

| CO(vol%) |

38.78 |

12.66 |

< 0.001 |

| CO2(vol%) |

33.40 |

45.93 |

< 0.001 |

| CH4(vol%) |

1.55 |

1.26 |

< 0.001 |

| CXHY(vol%) |

1.50 |

1.22 |

< 0.001 |

The purified syngas is subsequently converted into high-purity hydrogen via the WGS reactor and the PSA system. Through the WGS reaction, the syngas reacted with a CO conversion rate of approximately 60%, increasing the hydrogen composition from an initial 24.78% to 38.93%. Following syngas reforming, a hydrogen separation process is carried out using the PSA unit. The reformed syngas was fed into the PSA unit at a controlled flow rate of 100 Nm 3 /h, ultimately yielding a hydrogen production rate of 2.95 kg/h from the gasification of high-calorific waste (

Table 4).

3.2. Gasification Plant LCA

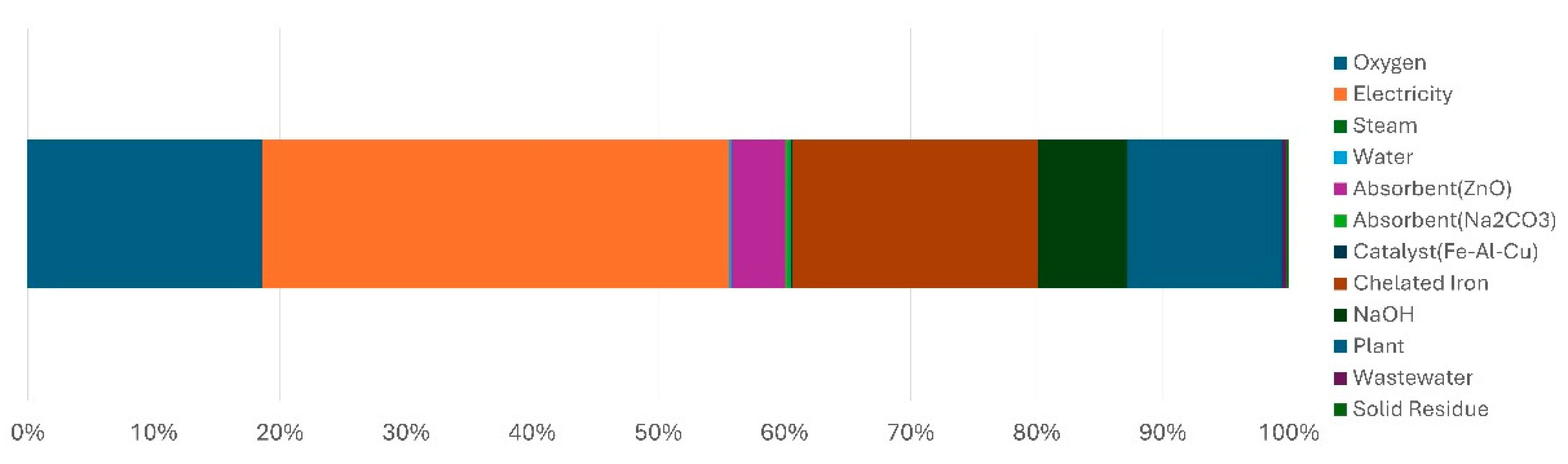

3.2.1. Life Cycle Inventory

Table 5 presents the key inventory data for the inputs and outputs required to produce 1 kg of hydrogen via high-calorific waste gasification. The LCI analysis revealed that approximately 28.8 kg of waste and 23.8 Nm

3 of oxygen were consumed to produce 1 kg of hydrogen. For pollutant removal, water, sorbents (for desulfurization and dechlorination), NaOH, and chelated iron were utilized. Steam and catalyst were supplied for the WGS reaction, and electricity was consumed for the overall plant operation (gasification, cleaning, reforming, and separation). The auxiliary fuel (LPG), used only during the initial start-up phase, was excluded from consideration due to its negligible quantity. The materials and utilities for plant construction, considered as a one-time input, were allocated by dividing their total amounts by the total quantity of hydrogen produced over the plant’s operational lifetime (160,000 hr). The outputs of the plant consist of hydrogen, wastewater from the cleaning unit, and a solid residue composed of ash and slag from the gasifier.

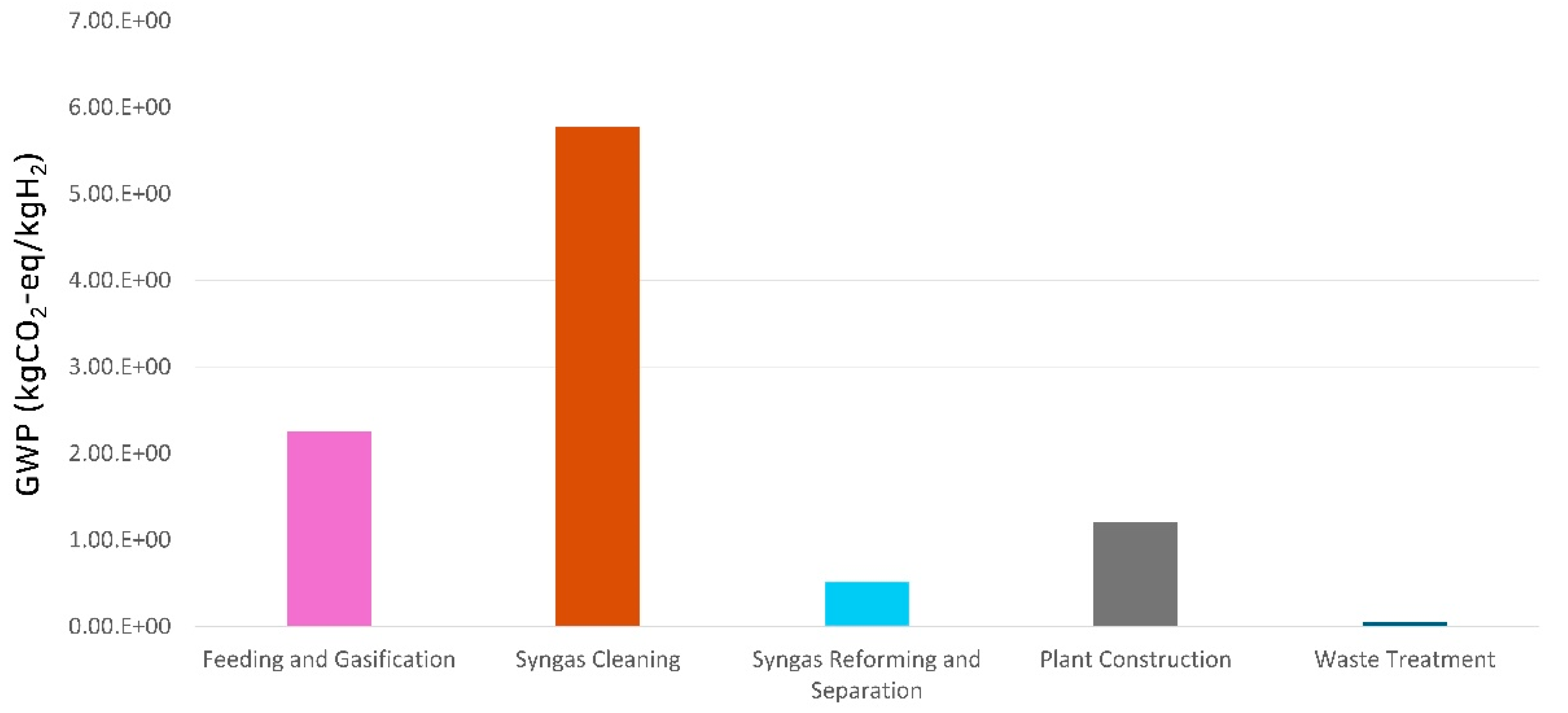

3.2.2. Life Cycle GHG Emissions

Table 6 shows the GWP environmental impact for the production of 1 kg of hydrogen from high-calorific waste gasification, and

Figure 4 illustrates the contribution analysis (hotspot) results by process stage. The total GWP for producing 1 kg of hydrogen was determined to be 9.80 kgCO

2−eq. The syngas cleaning process exhibited the highest environmental impact at 5.78 kgCO

2−eq, accounting for the largest share (58.95%) of the total impact. This was followed by the feeding and gasification process with 2.25 kgCO

2−eq (22.99%), plant construction with 1.21 kgCO

2−eq (12.30%), reforming and separation with 0.515 kgCO

2−eq (5.25%), and waste treatment with 0.049 kgCO

2−eq (0.50%). Within the feeding and gasification process, the impact from oxygen was identified as the most significant contributor, at 1.82 kgCO

2−eq (80.73%). For the syngas cleaning and the syngas reforming and separation processes, the impact of electricity was dominant, accounting for 46.70% (2.70 kgCO

2−eq) and 96.59% (0.497 kgCO

2−eq) of the GWP within each process, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 5, which presents the contribution analysis by material, the impact of electricity was the highest contributor to the GWP for producing 1 kg of hydrogen, accounting for 39.3% (3.99 kgCO

2−eq). This was followed by chelated iron at 18.8% (1.91 kgCO

2−eq), oxygen at 17.9% (1.82 kgCO

2−eq), and plant construction at 11.9% (1.21 kgCO

2−eq). Collectively, electricity, chelated iron, oxygen, and plant construction accounted for approximately 88% of the total GWP, with the remaining items contributing 12%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Hotspots and Improvement Strategies

The contribution analysis revealed that the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of hydrogen production from high-calorific mixed waste primarily stems from external electricity consumption, oxygen supply, chelated iron, and plant construction. The significant environmental impact attributed to electricity consumption is a characteristic feature of typical gasification and syngas production plants, resulting from the power required to operate various units, including the gasifier, cleaning, reforming, and separation facilities [

32,

33]. To address this, several strategies can be considered. First, an approach to reduce the fundamental electricity demand by enhancing the process’s intrinsic energy efficiency can be employed. For instance, the environmental burden from electricity consumption can be directly lowered by introducing high-efficiency equipment for major power-consuming facilities, such as gasifiers, compressors, and pumps, or by minimizing unnecessary energy losses through process optimization. Second, transitioning the power supply to low-carbon energy sources. If the electricity required for plant operation is sourced directly from renewables, such as solar or wind, instead of the national grid, the greenhouse gas emissions generated during the electricity consumption phase can be drastically reduced. These strategies can play a pivotal role in improving the environmental performance of this technology [

34].

The current practice of purchasing liquid oxygen from external suppliers induces a high environmental burden from a life-cycle perspective, owing to the substantial energy consumption inherent in oxygen production. As a potential mitigation strategy, the adoption of a non-cryogenic air separation unit, appropriately scaled for the plant, can be considered. Non-cryogenic air separation consumes approximately 20–35% of the energy required for liquid oxygen production, and it is therefore posited that this approach could substantially reduce the GWP associated with oxygen supply [

35,

36]. Alongside oxygen, chelated iron used for syngas cleaning was identified as another major environmental load, accounting for a significant 18.8% of the total GWP. To mitigate the associated environmental impact, strategies could include optimizing the operating conditions of the chelated iron regeneration (oxidation) reactor, such as air injection rate and pH, and enhancing the efficiency of the sulfur separation and washing systems to minimize the decomposition and loss of the chelated iron [

37].

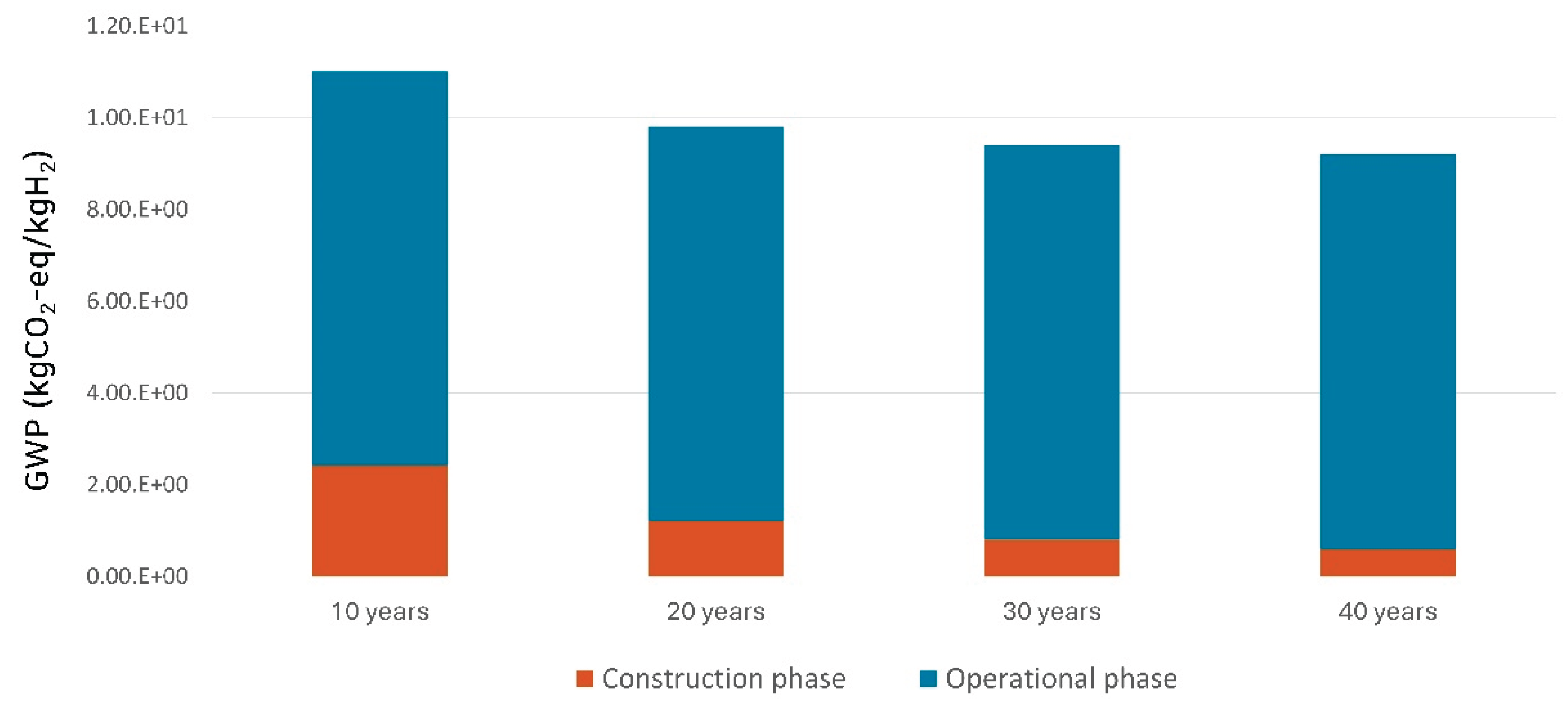

The environmental impact attributed to plant construction varies depending on the operational lifetime of the plant.

Table 7 and

Figure 6 present the environmental impact resulting from operating the plant for 10, 20, 30, and 40 years, assuming 8,000 annual operating hours. For a 10-year operational lifetime, the GWP impact from plant construction is 2.41 kgCO

2−eq, which constitutes 21.91% of the total GWP of 11.0 kgCO

2−eq. However, as the operational lifetime extends to 20, 30, and 40 years, the contribution of plant construction to the GWP diminishes to 12.30%, 8.55%, and 6.56%, respectively. Furthermore, it was confirmed that with the increase in the operational period, the GWP per 1 kg of hydrogen produced decreases by 15.91%, from 11.0 kgCO

2−eq for a 10-year lifetime to 9.20 kgCO

2−eq for a 40-year lifetime.

4.2. Comparison with Other Hydrogen Production Technologies

The life-cycle greenhouse gas (GWP) emissions from hydrogen production via high-calorific mixed waste gasification, as determined in this study (9.80 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2), were comparatively analyzed with results from previous LCA studies on other hydrogen production technologies (

Table 8). For a fair comparison, differences in system boundaries, feedstocks, and key processes of each study were carefully reviewed, and the GWP values were normalized to a functional unit of 1 kg of hydrogen produced. The technologies selected for comparison include those similar to this study, such as waste plastic or municipal solid waste (MSW) gasification, as well as traditional fossil fuel-based technologies and eco-friendly biomass-based technologies.

The most directly comparable study is that of Afzal et al. [

38], which investigated mixed plastic waste (MPW) gasification. In their research, the GWP for hydrogen production from MPW gasification was estimated at 12.8 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2, a value slightly higher than that of the present study. The primary difference is analyzed to stem from the energy supply methodology of the process; their study reported higher GHG emissions due to a significant reliance on natural gas combustion to supply the heat required for multiple endothermic reaction stages, including the gasifier, tar reformer, and steam reformer. This indicates that even in similar waste gasification processes, the level of internal heat integration and the choice of external energy sources can have a substantial impact on the overall GWP. Furthermore, their study reported an even higher GWP of 15.6 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2 for MSW gasification, which was attributed to the lower hydrogen yield resulting from the lower calorific value and hydrogen content of MSW.

Gasification technologies utilizing biomass as a feedstock present a stark contrast to the results of this study. Abawalo et al. [

39] evaluated the GWP for hydrogen production from agricultural residue (rice straw) gasification to be as low as 1.30 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2. This is because biomass is considered a ‘carbon-neutral’ feedstock due to its absorption of carbon dioxide during growth, and the process minimized fossil fuel use by recycling by-product gases as an energy source. Abawalo et al. [

39] also conducted a study on a process that produces hydrogen by reforming biogas generated from the anaerobic digestion of organic waste, assessing the GWP from biogas reforming at 5.05 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2. The GWP of the biogas reforming process was primarily attributed to methane leakage during anaerobic digestion and the consumption of grid electricity required for process operation. The reason the GWP of the high-calorific mixed waste gasification process in this study is higher than that of biogas reforming can be interpreted as twofold: the feedstock plastic is a fossil fuel-based material lacking the carbon fixation effect of biomass, and more energy (particularly electricity and oxygen) is consumed in the high-temperature gasification and purification processes.

A comparison with traditional fossil fuel-based hydrogen production technologies provides a crucial benchmark for understanding the current environmental position of this technology. Franchi et al [

40] and Elgowainy et al. [

41] have reported that the GWP of Steam Methane Reforming (SMR), the most prevalent technology today, ranges from 8.0 to 12.4 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2. According to studies by Verma [

42] and Elgowainy et al. [

41], coal gasification is assessed at a level of 11.6 to 18.0 kgCO

2−eq/kgH

2. The GWP value derived from this study falls within the range of SMR technology and is slightly lower than that of coal gasification. This suggests that, in its current unoptimized state, the waste gasification process does not demonstrate a distinct GHG reduction effect compared to existing fossil fuel-based technologies. Particularly, as the hotspot analysis in this study identified external electricity and liquid oxygen production as major contributors to the GWP, replacing these utility supplies with renewable energy could significantly improve the environmental performance.

Through this comparative analysis, it was confirmed that the GWP of the high-calorific mixed waste gasification technology evaluated in this study is comparable to that of traditional fossil fuel-based SMR and is markedly higher than that of biomass-based gasification technologies. This disparity is primarily due to the origin of the feedstock (fossil-derived plastics vs. bio-based biomass) and the types of external energy sources supplied to the process. Therefore, it is evident that enhancing process energy self-sufficiency and utilizing renewable energy are imperative for securing the environmental competitiveness of waste gasification technology in the future.

5. Conclusions

This study performed a cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA) of hydrogen production via high-calorific mixed waste gasification, utilizing actual operational data from a 2 TPD pilot plant. The Global Warming Potential (GWP) was determined to be 9.80 kgCO2−eq per kg of H2 produced. This figure falls within the emission range of Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) ( 8.0∼12.4 kgCO2−eq/kgH2) and is lower than that of coal gasification (11.6~18.0 kgCO2−eq/kgH2), suggesting a competitive environmental performance against conventional fossil fuel-based technologies. Furthermore, it exhibited slightly lower emissions than gasification methods using mixed plastic waste (MPW) or municipal solid waste (MSW). However, the emissions were significantly higher than those from biomass-based pathways. The primary environmental hotspots were identified as electricity consumption (39.3%), the production and use of chelated iron for gas cleaning (18.8%), the supply of externally produced oxygen (17.9%), and plant construction (11.9%).

These findings indicate that, in its current pilot-scale configuration, this Waste-to-Hydrogen (WtH) technology serves a critical dual purpose: valorizing problematic waste streams while producing a valuable energy carrier. Therefore, it is positioned as a strategic transitional pathway rather than a fully ‘green’ solution. However, this study has several limitations. The analysis relies on a linear scale-up from pilot data, which may not fully capture economies of scale and could potentially overestimate the GWP of a commercial-scale plant. Additionally, the system boundary was restricted to cradle-to-gate, the final hydrogen purification unit (PSA) was a virtual model rather than an actual facility, and the off-gas generated was assumed to be captured separately.

Future research should focus on validating these findings through an LCA of a commercial-scale plant using empirical data. In particular, the reliability of the assessment should be enhanced by re-performing the LCA after obtaining data from the actual construction and operation of the PSA process and off-gas capture unit, which were virtually applied in this study. Furthermore, an integrated Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) is essential to evaluate the financial feasibility of GWP mitigation strategies, such as improving equipment efficiency, process optimization, and adopting renewable energy. Additional research into alternative materials and processes with lower environmental impacts for syngas cleaning is also warranted. In conclusion, high-calorific mixed waste gasification is a promising enabling technology that bridges waste management and the emerging hydrogen economy, presenting a clear and actionable pathway for improving environmental sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K. and Y.P.; methodology, G.K.; software, G.K.; validation, J.G., Y.P.; data curation, G.K. and Y.P; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.P.; visualization, G.K. and J.G; supervision, J.G.; project administration, J.G.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (Grant RS-2024-00417444).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarwal, R. Transition to a hydrogen-based economy: possibilities and challenges. Sustainability 2014, 14, 15975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, R.; Rosen, M. A.; Dincer, I. Assessment of CO2 capture options from various points in steam methane reforming for hydrogen production. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20266–20275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Gupta, S. K.; Rajamohan, N.; Yusuf, M. Waste-to-energy technologies: a sustainable pathway for resource recovery and materials management. Mater Adv 2025, 6, 4598–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M. H.; Ahmad, A.; Rehan, M.; Musharavati, F.; Nizami, A. S.; Khan, M. I. Advancing Sustainable Energy: Environmental and Economic Assessment of Plastic Waste Gasification for Syngas and Electricity Generation Using Life Cycle Modeling. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlo, G.; Ali, I.; Mangi, K. H.; Ali, S.; Maitlo, H. A.; Unar, I. N.; Pirzada, A. M. Thermochemical conversion of biomass for syngas production: Current status and future trends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, U. H.; Ksepko, E. Advancing Municipal Solid Waste Management Through Gasification Technology. Processes 2025, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinci, Y.; Hepbasli, A.; Dincer, I. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen production from biomass gasification systems. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14026–14039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, M.; Cormos, C. C.; Agachi, P. S. Comparative life cycle analysis for gasification-based hydrogen production systems. J Renew Sustain Energy, 2014; 6, 013131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjaji, N.; Martinez, S.; Trably, E.; Steyer, J. P.; Helias, A. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen production from biogas reforming. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 6064–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, S.; Sebastiani, A.; Paulillo, A.; Materazzi, M. The environmental performance of mixed plastic waste gasification with carbon capture and storage to produce hydrogen in the UK. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2023, 11, 3248–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares Borges, P.; Silva Lora, E. E.; Venturini, O. J.; Errera, M. R.; Yepes Maya; D. M.; Makarfi Isa, Y.; Alexander, K.; Zhang, S. A comprehensive technical, environmental, economic, and bibliometric assessment of hydrogen production through biomass gasification, including global and brazilian potentials. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, M. P.; Longo, S.; Cellura, M.; Miccichè, G.; Ferraro, M. Critical review of life cycle assessment of hydrogen production pathways. Environments 2024, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moftah, A. M. S.; Marsh, R.; Steer, J. Life cycle assessment of solid recovered fuel gasification in the state of Qatar. Chem Eng 2021, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shukla, S. K. A review on recent gasification methods for biomethane gas production. Int J Energy Eng 2016, 6(1A), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Artetxe, M.; Amutio, M.; Alvarez, J.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Recent advances in the gasification of waste plastics. A critical overview. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2018, 82, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, C.; Cobo, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Environmental sustainability assessment of hydrogen from waste polymers. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2023, 11, 3238–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuter, P.; Fendt, S.; Spliethoff, H. Requirements on synthesis gas from gasification for material and energy utilization: a mini review. Front Energy Res 2024, 12, 1382377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanarasimhan, A.; Pathak, R. M.; Shivapuji, A. M.; Rao, L. Tar formation in gasification systems: a holistic review of remediation approaches and removal methods. ACS omega 2024, 9, 2060–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J. I.; Eom, T. H.; Lee, J. B.; Jegarl, S.; Ryu, C. K.; Park, Y. C.; Jo, S. H. Cleaning of gaseous hydrogen chloride in a syngas by spray-dried potassium-based solid sorbents. Korean J Chem Eng 2015, 32, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcantonio, V.; Müller, M.; Bocci, E. A review of hot gas cleaning techniques for hydrogen chloride removal from biomass-derived syngas. Energies 2012, 14, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Y.; Chen, Y. Y.; Wei, W. C. J. Reforming and Desulphurization of Syngas by 3D-printed Catalyst Carriers. Innov Ener Res 2017, 6, 1000172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibamoto, T.; Yasuhara, A.; Katami, T. Dioxin formation from waste incineration. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2007, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gong, H. Oxidative degradation stability and hydrogen sulfide removal performance of dual-ligand iron chelate of Fe-EDTA/CA. Environ Technol 2018, 39, 3006–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddi, I.; Chibane, L. Parametric study of high temperature water gas shift reaction for hydrogen production in an adiabatic packed bed membrane reactor. Rev Roum Chim 2020, 65, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G. K.; Kim, S. J.; Dong, J.; Smirniotis, P. G.; Jasinski, J. B. Long-term WGS stability of Fe/Ce and Fe/Ce/Cr catalysts at high and low steam to CO ratios—XPS and Mössbauer spectroscopic study. Appl Catal A Gen 2012, 415, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. L.; Kim, K. J.; Jang, W. J.; Shim, J. O.; Jeon, K. W.; Na, H. S.; Kim, M.K.; Bae, J.W.; Nam, S.C.; Jeon, B.H.; Roh, H. S. Increase in stability of BaCo/CeO2 catalyst by optimizing the loading amount of Ba promoter for high-temperature water-gas shift reaction using waste-derived synthesis gas. Renew Energy 2020, 145, 2715–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krótki, A.; Bigda, J.; Spietz, T.; Ignasiak, K.; Matusiak, P.; Kowol, D. Performance Evaluation of Pressure Swing Adsorption for Hydrogen Separation from Syngas and Water–Gas Shift Syngas. Energies 2025, 18, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; You, Y. W.; Lee, D. G.; Kim, K. H.; Oh, M.; Lee, C. H. Layered two-and four-bed PSA processes for H2 recovery from coal gas. Chem Eng Sci 2012, 68, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D. K.; Lee, D. G.; Lee, C. H. H2 pressure swing adsorption for high pressure syngas from an integrated gasification combined cycle with a carbon capture process. Appl Energy 2016, 183, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040. Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Principles and Framework 2006; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lijó, L.; González-García, S.; Bacenetti, J.; Fiala, M.; Feijoo, G.; Lema, J. M.; Moreira, M. T. Life Cycle Assessment of electricity production in Italy from anaerobic co-digestion of pig slurry and energy crops. Renew Energy 2014, 68, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Wu, Z.; Chen, D.; Huang, Y.; Ordomsky, V. V.; Khodakov, A. Y.; Van Geem, K. M. State-of-the-art and perspectives of hydrogen generation from waste plastics. Chem Soc Rev 2025, 54, 4948–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Huang, Y.; Jin, B.; Wang, X. Simulation of syngas production from municipal solid waste gasification in a bubbling fluidized bed using aspen plus. Ind Eng Chem Res 2013, 52, 14768–14775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Hu, L.; Xie, K.; Wang, P. A Study of the Life Cycle Exergic Efficiency of Hydrogen Production Routes in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszuba, M.; Ziółkowski, P.; Mikielewicz, D. Comparative study of oxygen separation using cryogenic and membrane techniques for nCO2PP. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 25-30 June 2023., Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems (ECOS 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Tolley, J.; Estupinan, L. Energy Consumption of Pressure Swing Adsorption vs. Vacuum Swing Adsorption - A Thermodynamic Study; Benchmark Oxygen Solutions: Alberta, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Song, W.; Zhai, L. F.; Cui, Y. Z. Effective sulfur and energy recovery from hydrogen sulfide through incorporating an air-cathode fuel cell into chelated-iron process. J Hazard Mater 2013, 263, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, S.; Singh, A.; Nicholson, S. R.; Uekert, T.; DesVeaux, J. S.; Tan, E. C.; Dutta, A.; Carpenter, A.C.; Baldwin, R.M.; Beckham, G. T. Techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment of mixed plastic waste gasification for production of methanol and hydrogen. Green Chem 2023, 25, 5068–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawalo, M.; Pikoń, K.; Landrat, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Production via Biogas Reforming and Agricultural Residue Gasification. Appl Sci 2025, 15, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, G.; Capocelli, M.; De Falco, M.; Piemonte, V.; Barba, D. Hydrogen production via steam reforming: A critical analysis of MR and RMM technologies. Membranes 2020, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgowainy, A.; Vyawahare, P.; Ng, C.; Frank, E. D.; Bafana, A.; Burnham, A.; Sun, P.; Cai, H.; Lee, U.; Reddi, K.; Wang, M. Environmental life-cycle analysis of hydrogen technology pathways in the United States. Front Energy Res 2024, 12, 1473383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. Life Cycle Assessment and Greenhouse Gas Abatement Costs of Hydrogen Production from Underground Coal Gasification. Master of Science Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).