1. Introduction

The concept of hydrogen as an energy vector has a long history, dating back to the energy crises of the 1970s. During this period, hydrogen was explored as an alternative fuel due to its combustion properties and potential for vehicle propulsion [

1,

2]. However, production and transportation challenges, coupled with limited technological advancements, led to a decline in interest by the late 1980s. [

3]. A second wave of interest emerged in the 1990s, with projects like Japan’s WE-NET exploring hydrogen for thermoelectric generation. [

4,

5]. The early 2000s saw another peak, fueled by climate concerns and influential publications like Rifkin's Hydrogen Economy, which linked hydrogen to broader economic and environmental transformations. [

6] Despite this renewed enthusiasm, hydrogen remained constrained by its role as an "energy carrier" rather than a resource, contributing to energy systems primarily at the end of the supply chain. [

7]. The recent global focus on decarbonization, catalyzed by the European Green Deal, [

8] and the Fit for 55 package [

9], has revived attention on hydrogen—specifically green hydrogen.

Unlike gray hydrogen (produced by natural gas) or blue hydrogen (natural gas with carbon capture), green hydrogen is derived from renewable energy, making it a cornerstone of sustainable energy systems. Events such as the 2022 war in Ukraine underscored the need for energy security and diversification, further accelerating investments in green hydrogen. These developments align with the unprecedented growth of renewable energy systems (RES), which has expanded from marginal contributions at the beginning of 2000 to over 3000 GW of installed capacity globally, driven by declining costs and supportive policies, [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The introduction of renewable sources into energy systems has often been supported by costly incentive systems for states. This is because renewable energy, while having no resource cost (unlike coal, oil, and natural gas), entail significant costs in terms of installed power. Various global incentive systems (economic capital support, premium tariffs, quota obligations, tax breaks, etc.) were designed to offset these power costs. The penetration of new renewable energies proceeded smoothly for the first 15 years, until around 2015. However, incentives mainly supported simpler energy sources with readily implementable technology, producing limited effects on the diffusion of other RES like concentrated solar power (less than 6 GW installed) and geothermal energy (less than 15 GW installed).

1.1. State of the Art: Green Hydrogen and Its Potential

The penetration of renewables has been transformative, with technologies like photovoltaic and wind power experiencing exponential growth. This progress has been supported by significant incentives, including feed-in tariffs, tax breaks, and quota obligations, which offset the high upfront costs of renewable installations. However, renewable electricity still accounts for about 15% of global energy use, while thermal energy, representing nearly 50% of consumption, remains under-addressed. Green hydrogen offers a pathway to bridge this gap, but there are a lot of additional problems. Although hydrogen has many positive qualities, such as its high energy density (calorific values of 120 and 144 MJ/kg respectively) and zero emissions when used, it also presents significant challenges, [

14]. Its low density (0.08-0.09 kg/m

3 at atmospheric conditions) makes storage and transport difficult, requiring high pressures or low temperatures. Additionally, hydrogen is highly flammable and has a wide flammability range, which increases safety concerns when handling or storing it.

Hydrogen is not readily available in nature and must be produced and as diffusely highlighted, it is not an energy source but an energy carrier. The distinction is important because hydrogen needs to be generated from primary energy sources, which can include renewable energy, but also fossil fuels in some current processes. Not all production systems are low in environmental impact; for instance, methods like Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) paired with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) still pose environmental and efficiency challenges. Moreover, hydrogen production via electrolysis, while promising in terms of reducing emissions, is highly energy-intensive and costly. This process involves splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. The overall efficiency of this process is less than optimal, and the high costs associated with renewable energy can make green hydrogen expensive compared to other energy carriers. Produced via water electrolysis powered by renewables, green hydrogen can contribute in a relevant way to decarbonizing sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as heavy industry, high-temperature processes, and transportation. It also addresses the intermittency and randomness of renewable energy by enabling large-scale energy storage. Furthermore, the potential to transport hydrogen across regions makes it a versatile energy carrier.

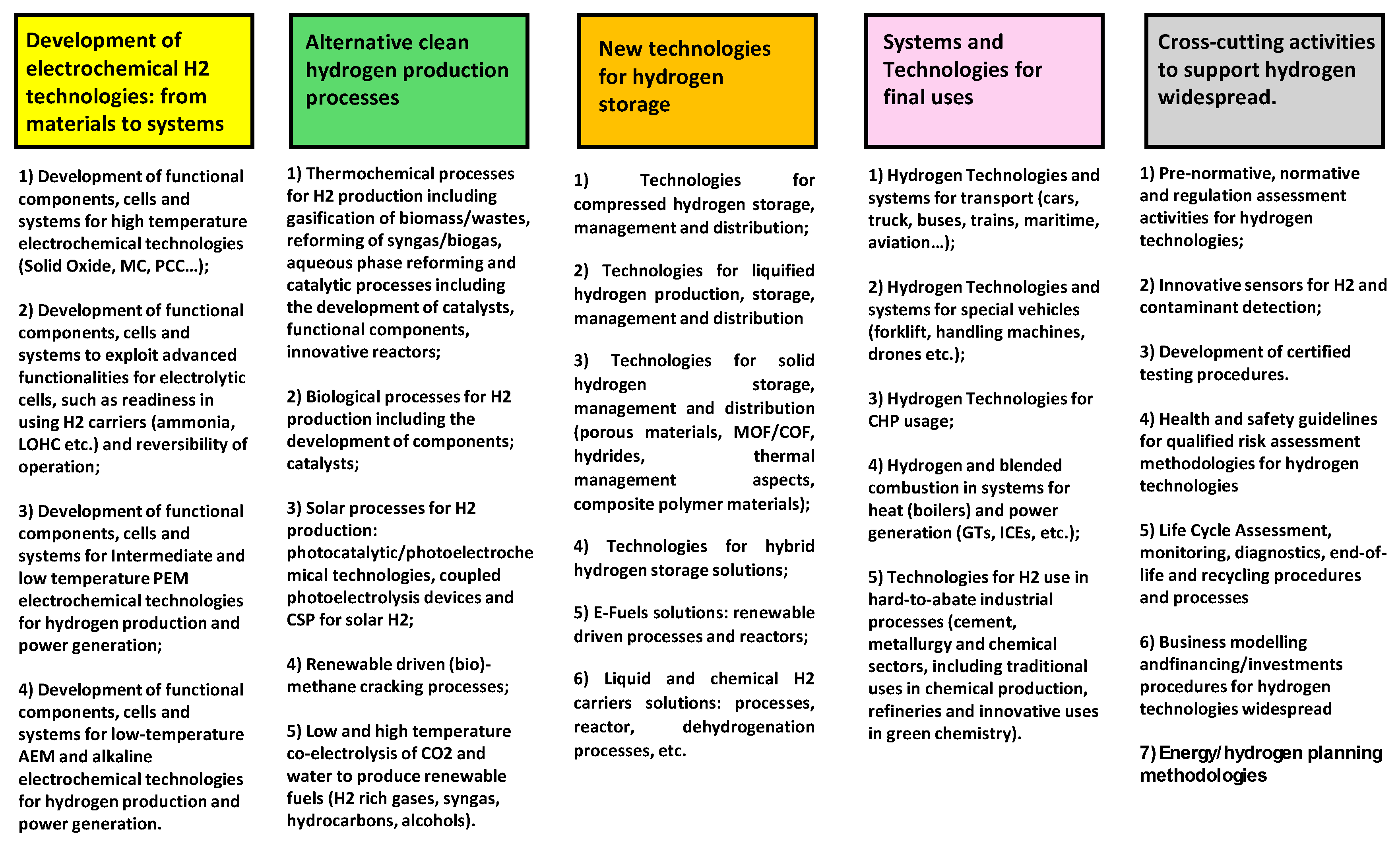

In recent years, numerous research streams on hydrogen have been active, reflecting an innovative dynamism and engagement in the sector, focusing on at least 5 major areas with 25-30 different topics, ranging from hydrogen production to the cross-cutting activities to support hydrogen widespread, as reported in

Figure 1, [

15]. Hydrogen research spans from production and storage methods to end uses and cross-cutting activities. Many projects centered on green hydrogen are currently active worldwide and across Europe, involving research institutions, academia and industry, fostering synergies to accelerate technological development and commercialization. The author has analyzed the problem from different perspectives in recent papers [

16,

17,

18]. The cost of hydrogen, mainly of green hydrogen while declining, remains significant, and the energy efficiency of the hydrogen cycle (production, storage and use) is lower than that of direct electrification, [

19].

Moreover, infrastructure for hydrogen storage and transport is underdeveloped, [

20] and rapid scaling risks unintended consequences, such as increased fossil fuel use for hydrogen production.

The integration of hydrogen must therefore be approached with caution to avoid rebound effects and inefficiencies. In the context of climate targets like those set by the European Union, ambitious hydrogen strategies have emerged. Projects under the Green Deal aim to produce millions of tons of green hydrogen annually, yet they often lack clarity on the production sources and implementation timelines. Green hydrogen can drive the energy transition, but only if used correctly. To unlock its full potential as a decarbonization tool, it's crucial to consider the entire energy chain. Beyond production, storage and transfer present significant technical and economic challenges, making infrastructure changes essential for its success.

1.2. Contribution of This Paper

What seems to be lacking in the current analysis of hydrogen's potential is a comprehensive and strategic perspective that seeks to frame the potential of this energy carrier in a more integrated way. Current contributions certainly focus on a wide range of activities, from the development of hydrogen production technologies (such as numerous studies on electrolysis) to overly general visions that present scenarios and projections. What seems to be missing, at least now, is an intermediate-level connection that delves into potential strategies that could work at a mid-level, starting from relevant and significant proposals for hydrogen use in decarbonization, with specific references to particular contexts. These are undoubtedly difficult to propose and implement, as they require a more specialized understanding of the application sectors, but they represent the only real opportunity to unlock hydrogen's full potential.

This paper aims to critically analyze the role of green hydrogen within the energy transition, with a focus on identifying the most promising strategies for its deployment. It builds on recent technological advances, including the competitive pricing of renewables and improved efficiency of electrolysis, to assess pathways for effective integration. This work aims to focus on the ongoing research on hydrogen, which is receiving numerous contributions, though not always in a coordinated manner. Our objective is to provide a critical and thoughtful analysis of these activities, offering a realistic perspective to distinguish between highly promising developments and those that, while valuable for cultural and scientific exploration, are less likely to have significant practical impact.

Beyond offering a critical assessment, this work seeks to provide a general contribution and a possible overarching vision of hydrogen’s role. While research should continue across all technological fronts, it would be highly beneficial to start outlining clearer pathways for implementation. This process must necessarily include an analysis of the scale and dimensions involved, as these factors play a fundamental role in determining the feasibility and impact of different hydrogen strategies. Without a structured approach that integrates both technological advances and practical constraints, there is a risk of fragmentation in research efforts, leading to inefficiencies and missed opportunities.

This work adopts an energy systems perspective, highlighting the importance of balancing hydrogen production with system-wide efficiency. By evaluating strategies such as sector coupling, energy storage integration, and infrastructure development, this analysis aims to provide actionable insights. Particular attention is given to ensuring that hydrogen's adoption contributes to a net reduction in fossil fuel dependency. By grounding the discussion in historical lessons, recent data, and a critical evaluation of ongoing initiatives, this paper aims to provide a realistic roadmap for leveraging green hydrogen to achieve meaningful decarbonization while also serving as a timely reminder to temper recent enthusiasm with caution, to avoid the risk of progressive disillusionment as challenges and limitations become more apparent. The paper is organized as follows. After an Introduction focusing of the recent history of hydrogen,

Section 2 highlights the potential of green hydrogen as a key element in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors.

Section 3 discusses the diverse final uses of green hydrogen, including industrial applications, energy storage, and mobility solutions.

Section 4 and

Section 5 focus on the technical and economic limitations hindering widespread adoption, such as efficiency losses, storage difficulties, and high production costs.

Section 6 proposes strategies to overcome these challenges, emphasizing innovation, policy support, and cross-sectoral integration. The discussion in

Section 7 provides insights into future perspectives and outlines pathways for enhancing the role of green hydrogen in the global energy transition. Finally,

Section 8 concludes by summarizing key findings and underscoring the need for collaborative efforts to unlock the full potential of green hydrogen.

2. Green Hydrogen and Its Potential for Decarbonization

Over the last five decades, the role of hydrogen as an energy carrier has been proposed and reconsidered multiple times, reflecting evolving technological, economic, and environmental priorities. In the 1970s, the oil crisis spurred interest in hydrogen, which was primarily explored as an alternative fuel for vehicles. At that time, hydrogen was seen as a promising substitute to conventional fossil fuels, potentially paving the way for greater energy independence in transportation, [

21]. By the middle of the 1990s, interest in hydrogen extended to power generation. Early initiatives revisited earlier concepts—exemplified by the WE-NET project—while research into fuel cells for direct conversion also gained momentum. Hydrogen was thus proposed not only for integration into thermodynamic cycles, such as Steam Injected Gas Turbines (STIG), to enhance efficiency and reduce emissions, but also for direct energy conversion, [

22,

23].

In the early 2000s, the hydrogen role was revisited with a stronger focus on environmental sustainability. It was seen as a tool to decarbonize energy systems, but its role as an energy carrier—not a primary energy source—posed challenges, especially given its complexity compared to other energy carriers, [

24]. In the last period, the effort has evolved to align hydrogen with the growing penetration of renewable energy with the perspective of decarbonization [

25]. In each of the previous phases, strong enthusiasm and many activities were generated, which, although they produced a great deal of work and interesting advancements in knowledge, did not always produce the significant effects that were hoped for.

Table 1 outlines the differences in hydrogen use proposals over the years, highlighting the shifting priorities and challenges across these periods.

Hydrogen is now being reconsidered for its potential to store excess RES production and facilitate grid balancing. The concept of introducing green hydrogen for decarbonization is appealing for several reasons. In principle in combustion processes. Unlike fossil fuels, hydrogen combustion produces no CO2 emissions, and its versatility makes it suitable for a wide range of applications, from mobility to high-temperature industrial processes. Over the past 30 years, there has been significant penetration of renewable energy sources into international energy systems.

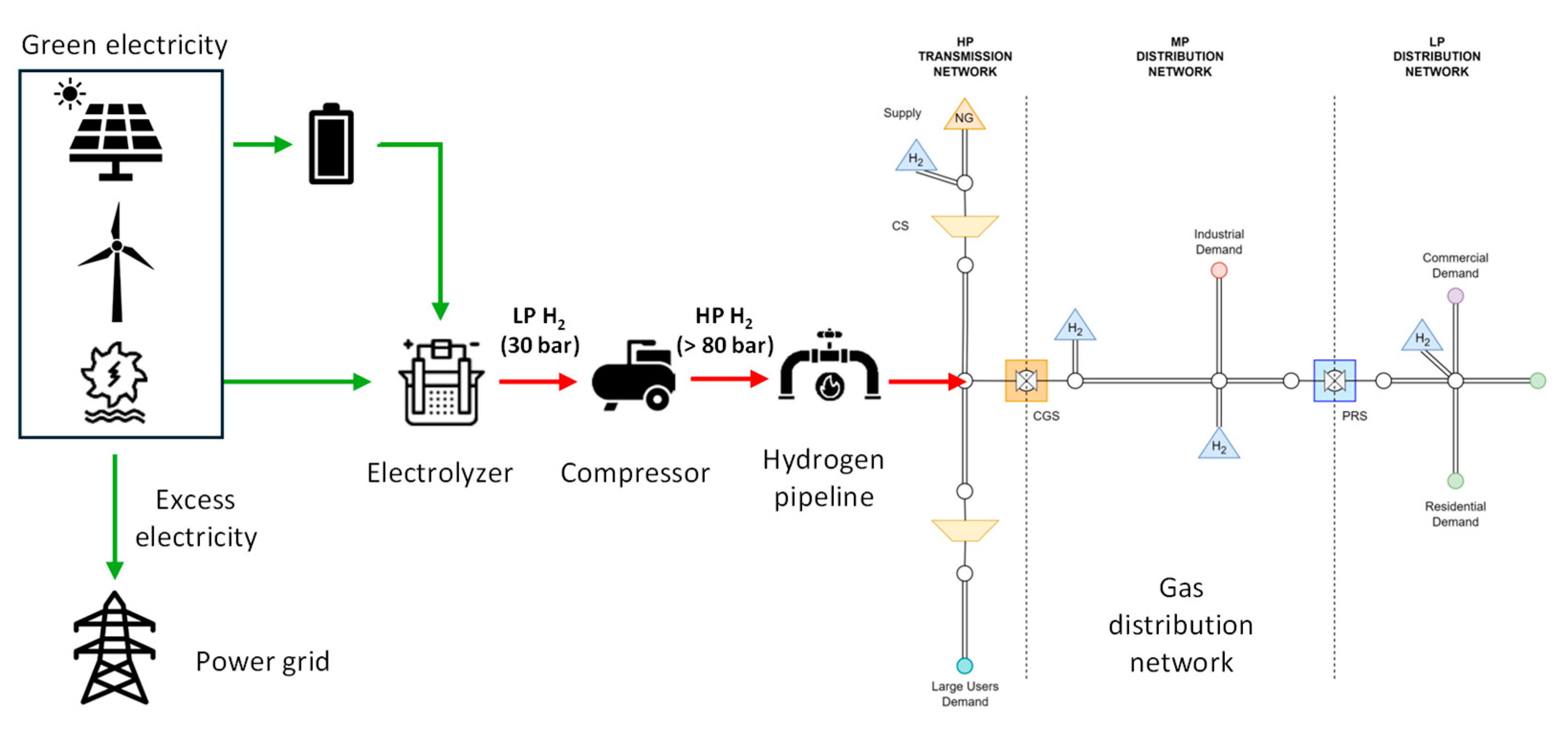

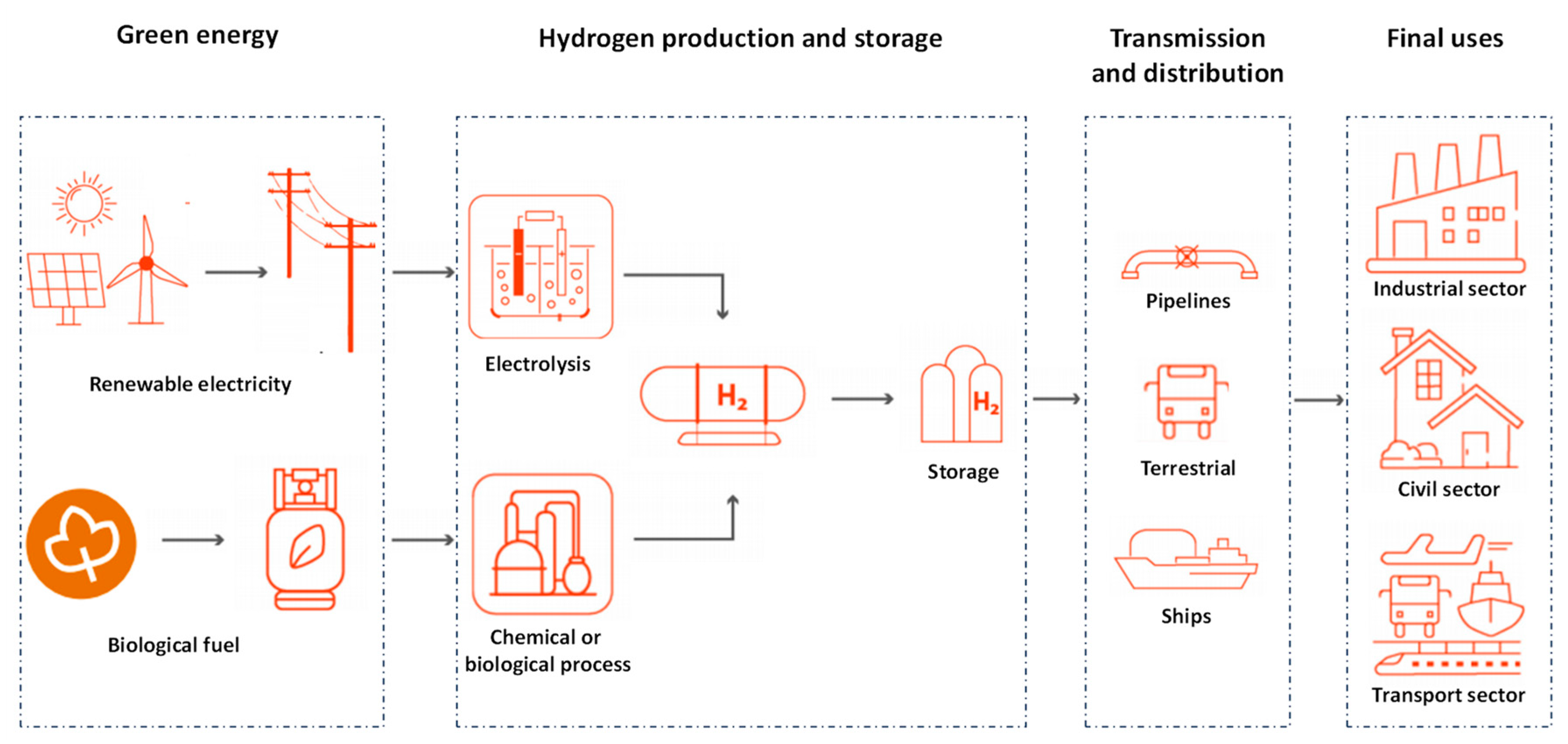

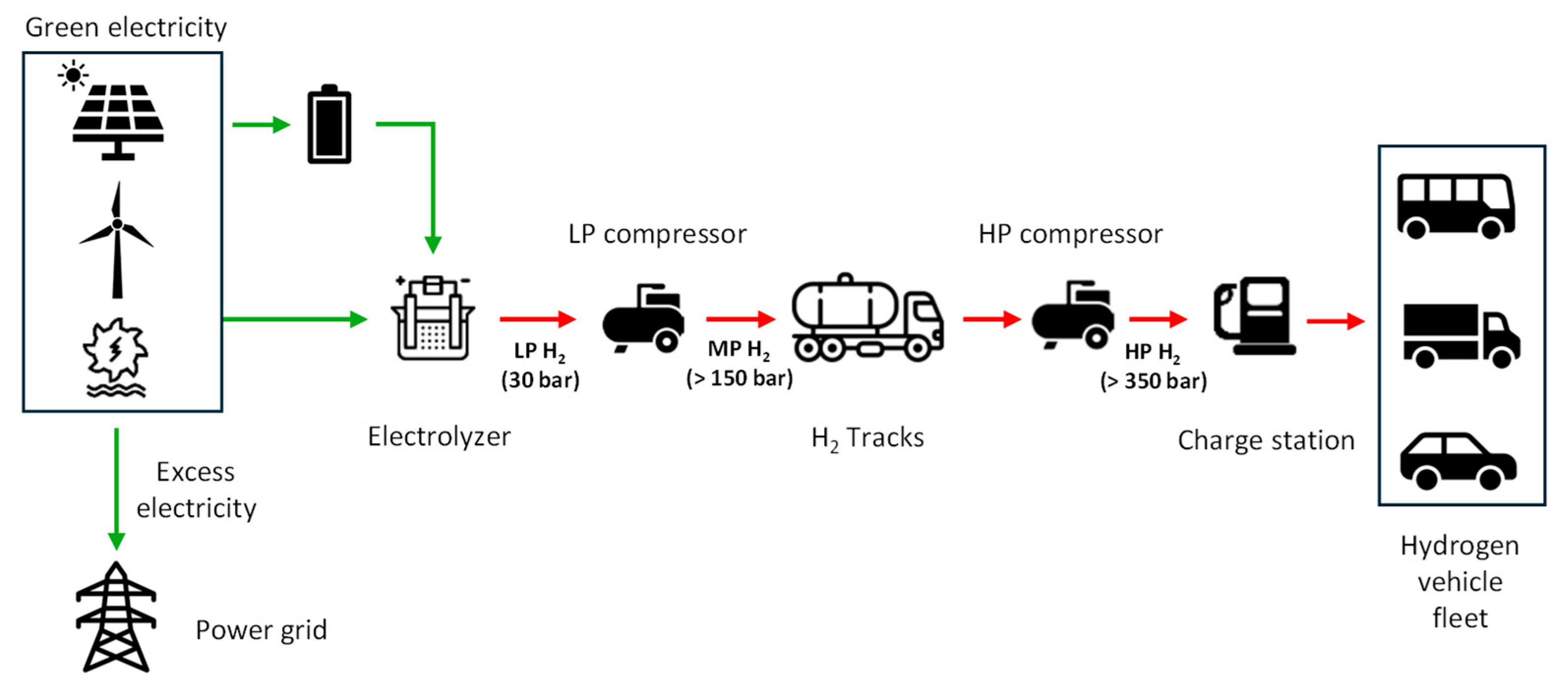

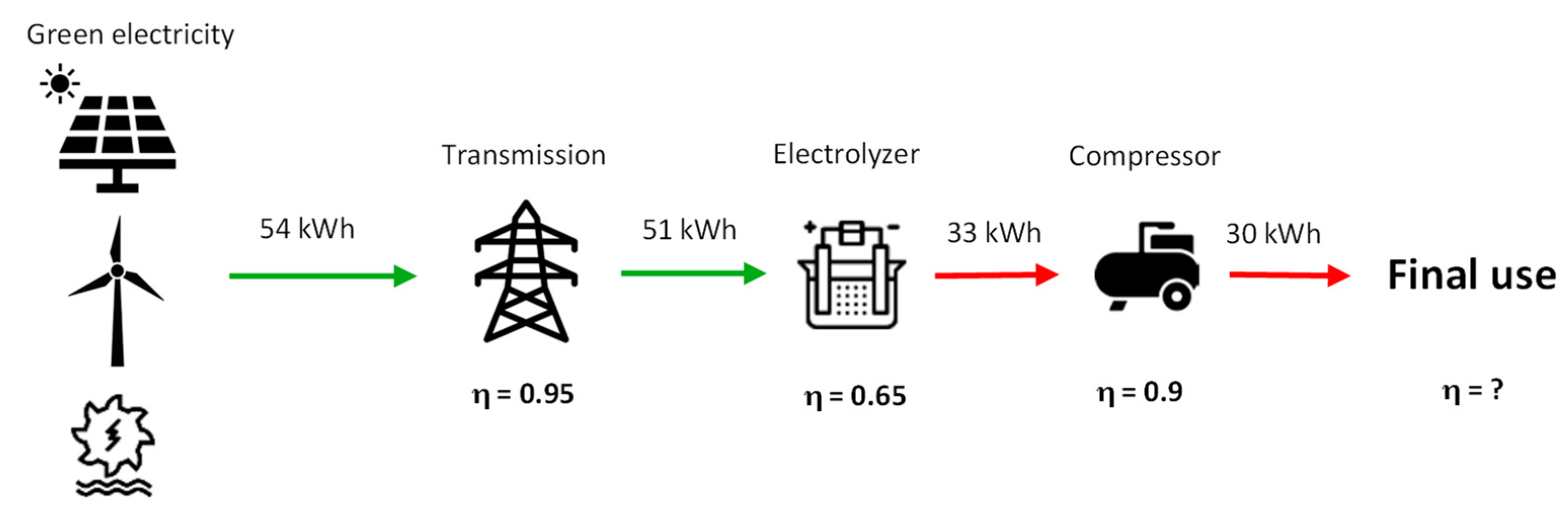

This growth has been driven primarily by technological advancements, though it has also been supported by economic incentives and the imposition of international rules and protocols. The most easily implemented technologies, particularly wind and later solar power, have seen the most widespread adoption. Looking at the last decade, we can observe that the installed capacity of wind and solar has surpassed that of the historically dominant renewable energy source, hydropower. As a result, renewable energy now accounts for at least 30% of the electricity sector. However, the electricity sector still represents only a small share of total energy consumption. Penetration has been more challenging in the thermal and mobility sectors, which are precisely the areas where greater integration is needed. It is in these sectors that hydrogen can play a key role in promoting further decarbonization. Moreover, green hydrogen offers the potential to leverage renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, to decarbonize sectors that are difficult to electrify and to provide long-term energy storage solutions for balancing the intermittency of renewables. This versatility positions green hydrogen as a critical component of a sustainable energy future. However, one of the fundamental challenges of green hydrogen lies in its overall energy efficiency. The hydrogen supply chain (

Figure 2) is inherently serial, involving multiple stages: electricity generation from renewable sources, hydrogen production through electrolysis, storage, transportation, and final use. Each step incurs energy losses, with the combined efficiency often dropping below 30% when considering the entire chain. For example, electrolyzers typically operate at 60-70% efficiency, hydrogen storage and transport introduce additional losses, and the final use introduces further efficiency problems. This stands in stark contrast to direct electrification, which retains a much higher efficiency and avoids the complexity of intermediate steps. These inefficiencies make the role of green hydrogen highly situational, emphasizing the need for careful evaluation of its optimal use cases. The economic aspect further complicates the picture. Green hydrogen, produced via water electrolysis powered by renewables, currently costs between

$4 and

$6 per kilogram, a value significantly higher than that of blue hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS) at a cost of

$1 to

$2.5 per kilogram. [

26,

27,

28].

Its production relies on fossil fuels, specifically methane, and the steam methane reforming (SMR) process generates large amounts of CO

2. While CCS can theoretically capture up to 90% of these emissions, technical limitations and high energy costs often result in lower capture rates. Additionally, methane leakage along the natural gas supply chain poses a major environmental concern, as methane is a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential far greater than CO2. While blue hydrogen could provide short-term benefits, its heavy reliance on fossil fuel infrastructure raises concerns about locking in high-carbon systems and diverting resources from fully renewable solutions. Moreover, the long-term viability of CCS is uncertain, given the risks of CO2 leakage from geological storage sites and the economic challenges of scaling this technology. In contrast, green hydrogen represents the only truly sustainable option, albeit with significant hurdles to overcome. Its high production costs, low overall efficiency, and reliance on robust renewable energy deployment require targeted strategies to enhance competitiveness and ensure its integration into energy systems without unintended consequences. The strategic emphasis on green hydrogen as a cornerstone of decarbonization reflects its unique ability to address the limitations of direct electrification in specific sectors, [

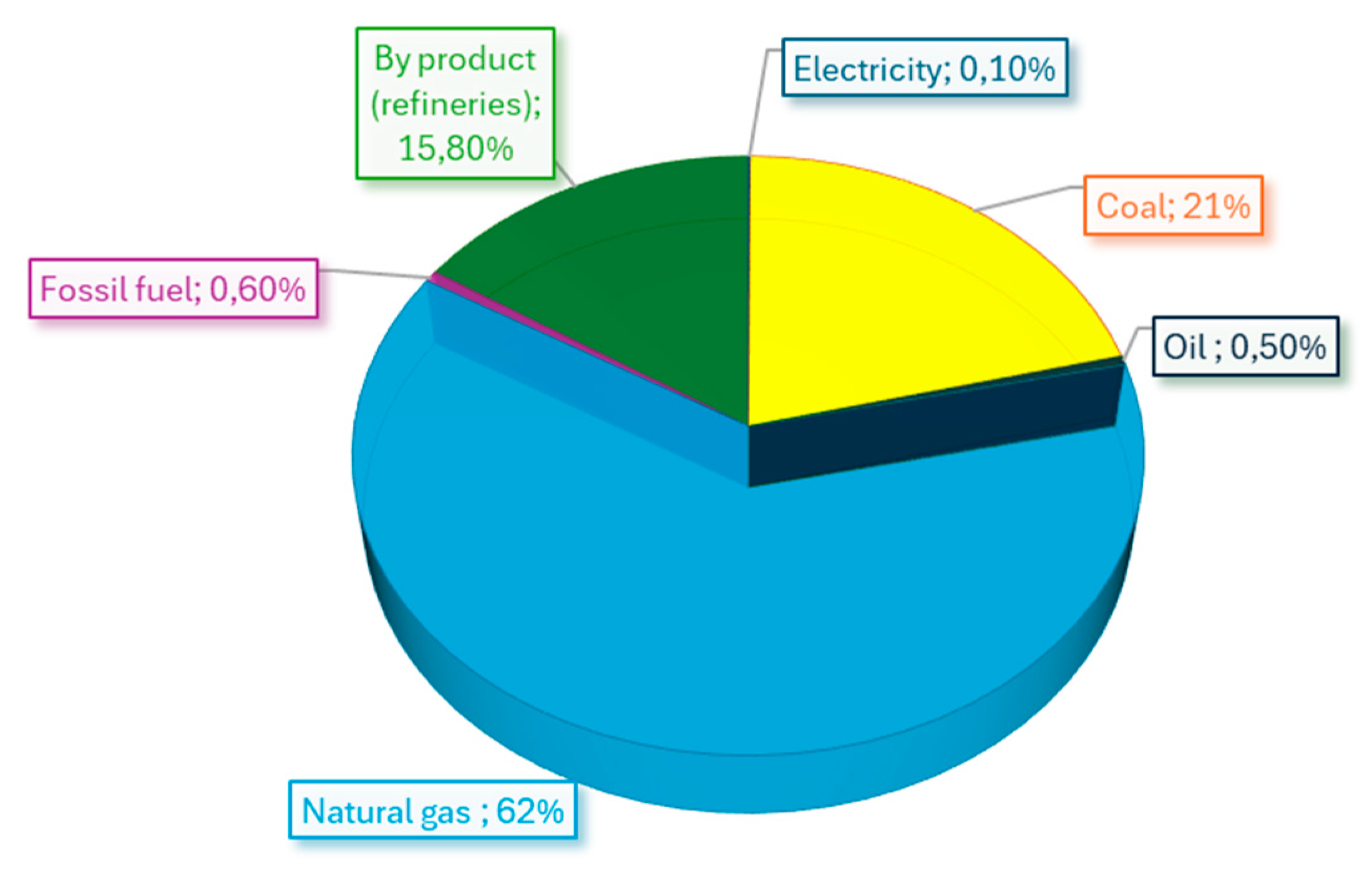

29]. At the same time, the pathway to its widespread adoption must account for the current technological and economic realities, prioritizing applications where its benefits outweigh its inefficiencies. The following sections will explore these strategies, focusing on promising technologies, infrastructure needs, and policies that could accelerate the transition while avoiding reliance on transitional solutions that may hinder long-term sustainability. Despite the significant momentum driven by decarbonization policies in recent years, hydrogen production has grown at a modest pace. More importantly, the share of green hydrogen remains particularly low. As of late 2023, green hydrogen accounted for approximately 0.1% of global hydrogen production, highlighting the limited progress in this critical area. To date, the growth in hydrogen demand has not been triggered by political efforts, but rather by general global energy trends. Hydrogen demand, in fact, remains concentrated in industry and refining, with less than 0.1% coming from new applications in heavy industry, transport or power generation. Low-emission hydrogen is implemented to a very small extent in existing applications, which represent only 0.7% of demand. The annual growth rate of hydrogen production is still around 1-2 percentage points, far below the levels required to meet ambitious decarbonization targets. These figures underscore the gap between current efforts and the scale of transformation needed to make green hydrogen a major contributor to the energy transition. Hydrogen demand is currently concentrated in traditional sectors like refining, chemical production (ammonia and methanol), and steel manufacturing (via the direct reduced iron process), with most of this demand being met by hydrogen produced from unabated fossil fuels.

Table 2 and

Figure 2 illustrate the current state of hydrogen production, offering a clearer picture of the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. The data illustrates how the growth trend in hydrogen production (1-2% for year), and particularly in green hydrogen, remains relatively modest. The presented

Table 3 and

Figure 4 collectively highlight a critical observation about the hydrogen sector's evolution. Despite the considerable emphasis placed on green hydrogen as a possible pillar of decarbonization strategies, recent data does not show a definitive trend of robust growth. The key sectors for green hydrogen remain refining, ammonia production, methanol production, and steel manufacturing. Moreover, it is evident that the marginal contribution of green hydrogen, which remains a small fraction of overall production. This analysis suggests a need to reevaluate strategies, ensuring that technical, economic, and policy barriers are addressed effectively to unlock hydrogen’s full potential in the energy transition.

Table 4 provides a concise summary of the current state of hydrogen, offering key data points that reflect its production levels, distribution, and applications. Despite some encouraging signals, current data shows that hydrogen has limited market penetration. Alongside technological and economic challenges, a coherent strategic vision seems lacking. A more integrated approach could follow four stages: first, medium-scale production for major consumers; second, expansion with semi-centralized hubs for local markets; third, market maturation; and finally, a cross-regional or intercontinental hydrogen market (

Table 5). While this roadmap provides clarity, many initiatives are already developing in parallel.

3. Green Hydrogen Production

The field of green hydrogen research and application is vibrant and rapidly evolving, as evidenced by the wide array of ongoing studies and initiatives. Despite the current achievements being relatively modest, substantial efforts are underway across various fronts, from production technologies to storage solutions and integration into energy systems. However, many of these activities lack a cohesive and overarching strategic vision. The realization of green hydrogen’s potential as a key driver of decarbonization will require progress on two interconnected levels: the optimization of individual technologies and the development of a more integrated and strategic framework.

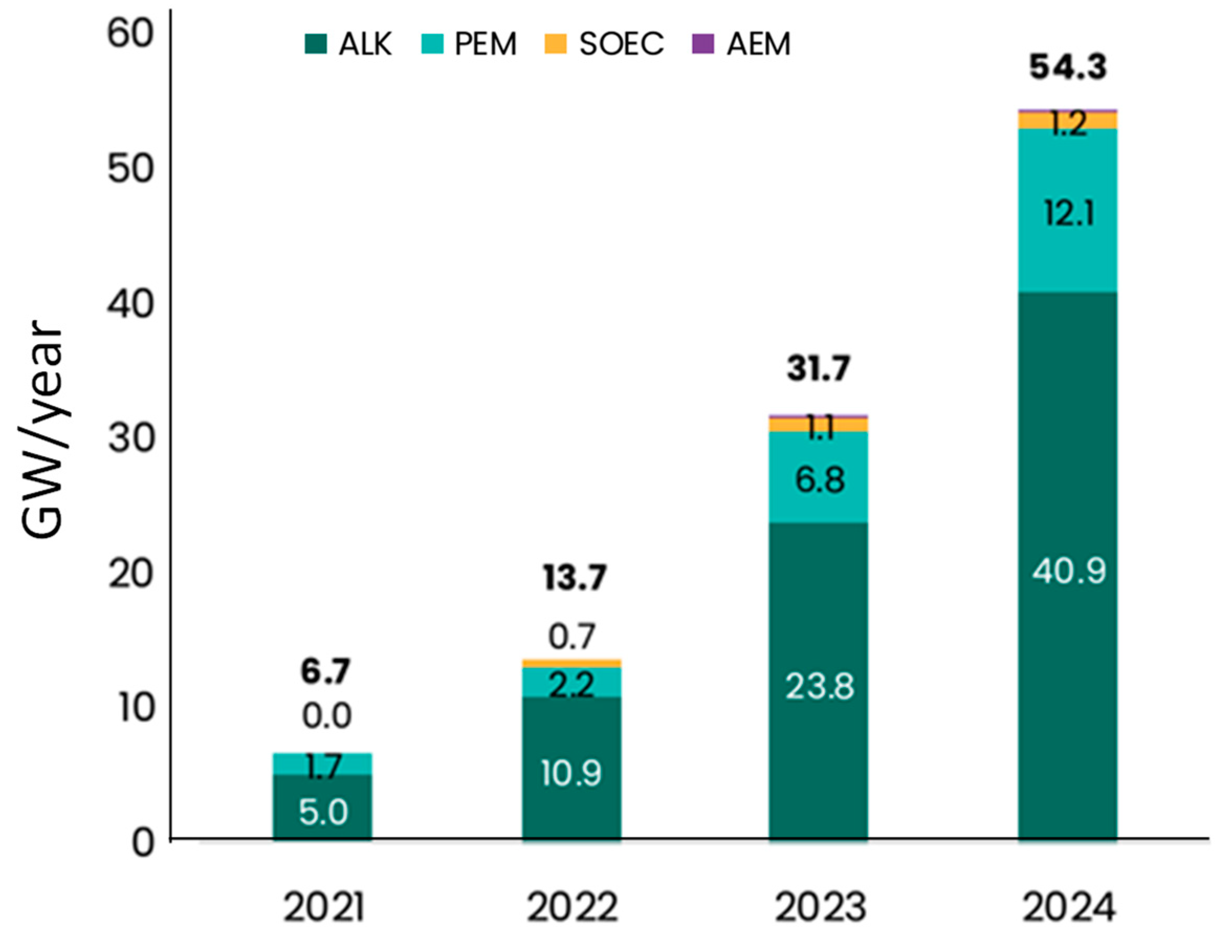

3.1. Technologies for Green Hydrogen Production: The Water Electrolysis

The advancement of water electrolysis technologies is surely a cornerstone of green hydrogen production, for example solar and wind, allowing for the mitigation of fluctuations between load demand and generation phases. Electrolytic hydrogen production is the most promising large-scale method for "green" hydrogen, while fuel cells provide the most efficient power conversion. A lot of research activities focus on developing electrochemical technologies for hydrogen production and use, covering both low-temperature (PEM, ALK, AEM) and high-temperature systems. Activities include multiscale modeling, material and component optimization, prototyping, testing, and defining guidelines for upscaling. Research aims to enhance performance, durability, and characteristics like gas permeability by functionalizing commercial materials. The goal is the development of advanced technologies for fuel cells and electrolyzers to improve efficiency and scalability.

When considering a green hydrogen production chain, a relevant element to evaluate is undoubtedly the energy loss associated with the production process. The production method that must be considered is water electrolysis. The energy content of hydrogen produced via electrolysis is inevitably lower than the energy required for the electrolysis process itself.

Table 4 provides a summary of data that effectively frames the current state of the technology. Several papers, as [

30] critically examine recent innovations and prospects in electrolyzer design, focusing on improving efficiency and reducing costs. The great part of the contributions highlights the need for ongoing research to address bottlenecks such as material degradation, energy loss, and scalability. Enhancing electrolyzer performance is crucial to making green hydrogen competitive with hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, particularly in terms of cost and energy efficiency.

Data from literature and the market, summarized in

Table 6, show that actual energy consumption for hydrogen production exceeds theoretical values. Electrolysers with nominal powers above 100 kW demonstrate specific electricity consumption (SEC) averaging 55–60 kWh/kg for low-temperature systems and 48–50 kWh/kg for high-temperature ones (in this case no market data are available). The state of the art evidences a value of 0.6 for the efficiency of the electrolysis process by the following synthetic equation, in which the water and energy requirements to obtain 1 kg of hydrogen are outlined:

These figures underscore efficiency losses and higher energy demands in practical hydrogen production. The current production capacity of electrolyzers is still relatively low and predominantly focused on low-temperature technologies. This reflects the early stage of development of high-temperature electrolysis technologies, which, although promising, are not yet mature for large-scale production.

Figure 5 clearly illustrates how the majority of electrolyzer manufacturing capacity is still dedicated to low-temperature technologies, with limited growth in high-temperature technologies, which are expected to remain a niche in the coming years.

Electrochemical hydrogen technologies—spanning water electrolysis for green hydrogen production and fuel cells for efficient power generation—are under active investigation across multiple research fronts (

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9). Solid oxide-based electrolysis technologies appear to be the most promising conceptually, as they could require less energy to operate. However, this is true only if residual heat is available. Moreover, their high operating temperatures make the operation of these systems significantly more complex. Efforts include exploring both low-temperature systems (PEM, ALK, AEM) and high-temperature solutions (SO) through multiscale and multicomponent modeling, innovative design and optimization of materials, components, and system layouts, as well as prototyping, testing, and validation. In parallel, the synthesis of novel materials and the functionalization of commercial ones aim to enhance performance, durability, and properties. Water electrolysis has seen the most significant development, with currently available systems demonstrating enormous potential for decarbonization. Although further evolution is needed, these technologies are ready to be effectively considered.

3.2. Green Hydrogen Production Beyond Electrolysis

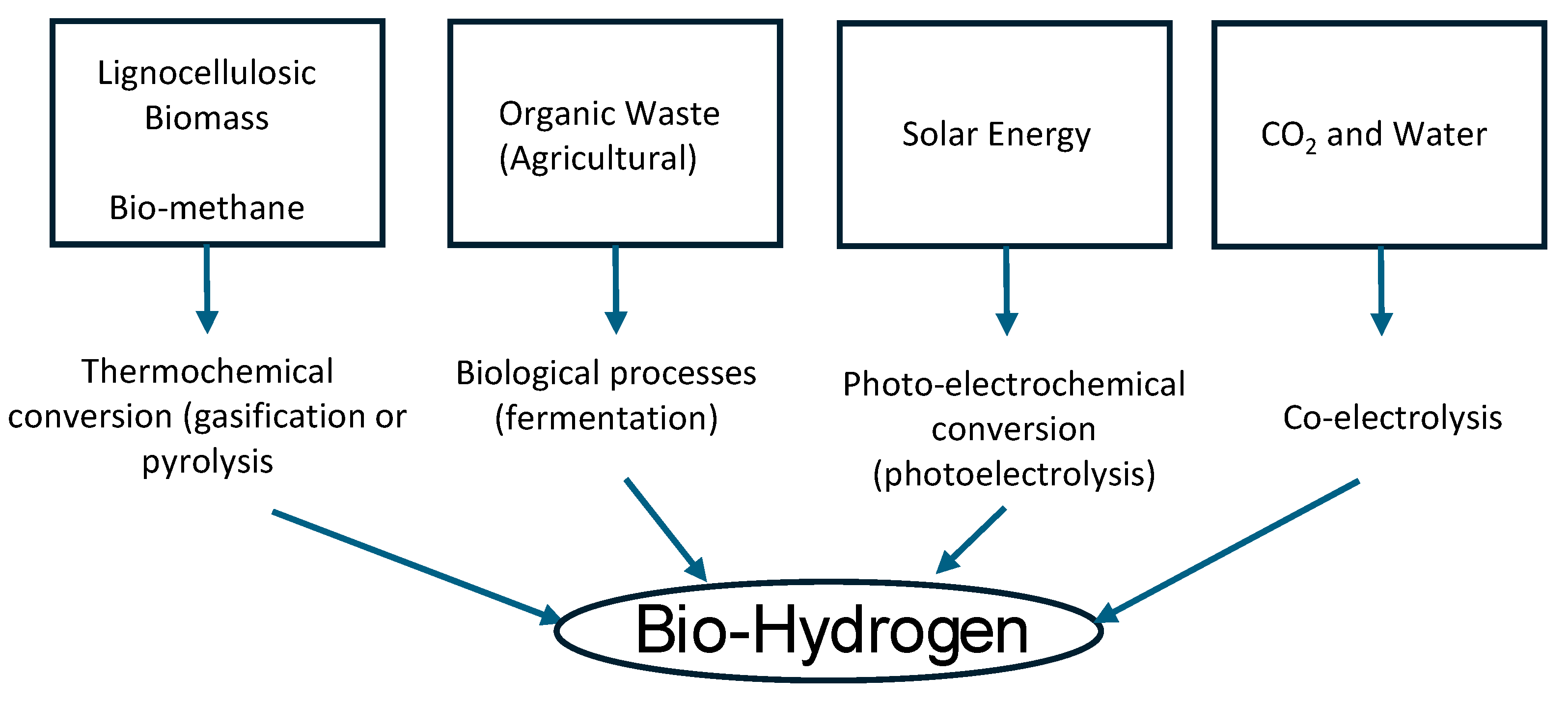

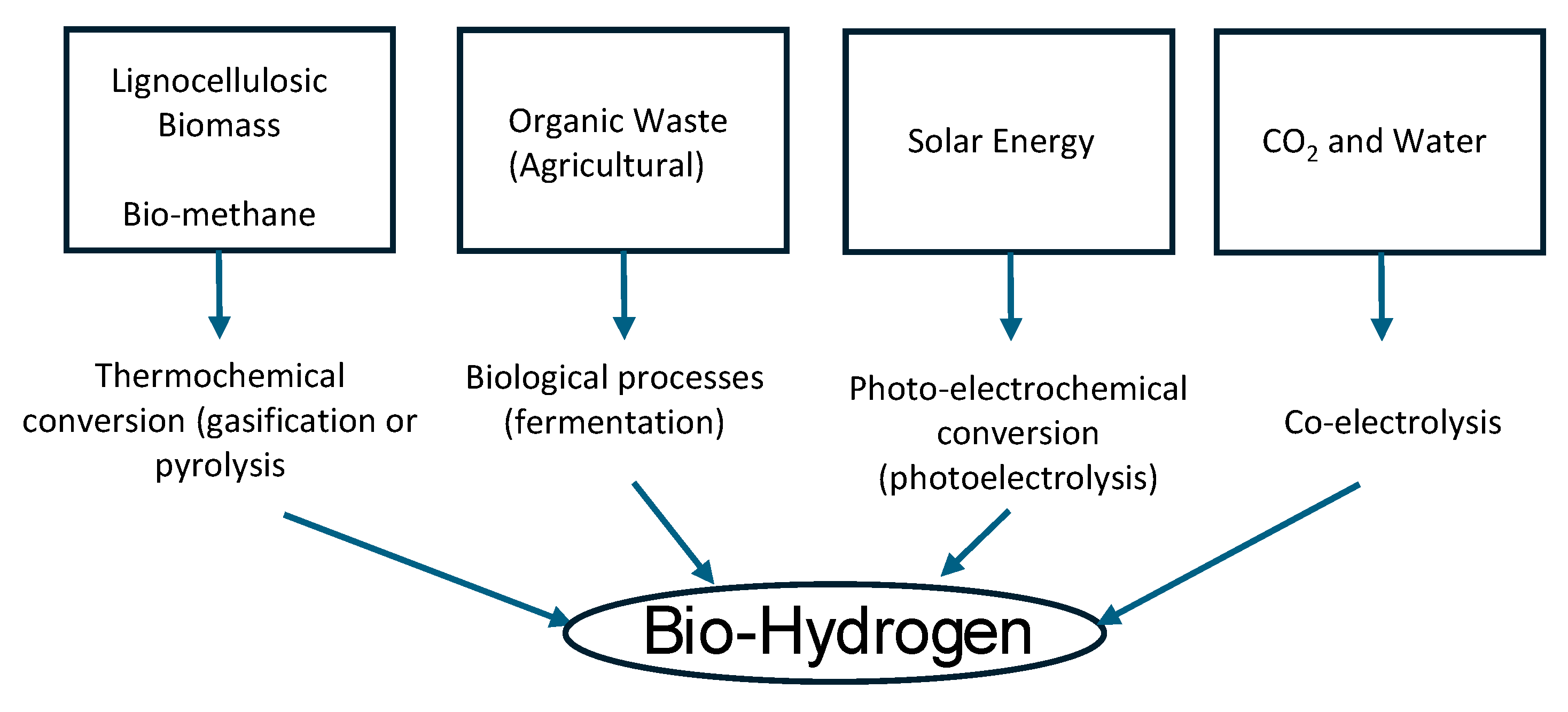

A relevant research activity deals with the exploration and development of the most promising alternatives to the electrolytic route to produce clean hydrogen. In the present heterogeneous and continuously evolving society to have access to different sustainable and efficient technologies to produce hydrogen is fundamental to assure its availability not only in urban and industrial areas, but also in remote communities or in agriculture and animal husbandry-based economies. The utilization of the most appropriate hydrogen production technology, contextualized to the local socio-economic reality, is essential, also considering the difficulties and the relevant costs related to the transport and storage of this energy carrier. The targets of the selected technologies will be, respectively, the production of clean hydrogen from renewable feedstocks, such as bio-methane or lignocellulosic biomass, toward thermochemical processes, the direct bio-hydrogen production, the study of photoelectrochemical systems to produce solar hydrogen, the electrolytic production from carbon dioxide and water of reduced products.

While electrolysis remains the most discussed method for producing green hydrogen, numerous alternative routes present promising opportunities for clean hydrogen generation. As shown in

Figure 6, alternative processes such as pyrolysis, biomass gasification, and biohydrogen production using microorganisms offer diverse renewable options, each with distinct efficiencies and challenges. This variety of technologies highlights that sustainable hydrogen production is not limited to a single approach but can evolve through multiple pathways, depending on specific conditions and advancements.

These methods broaden hydrogen production possibilities across diverse socio-economic and geographic contexts. However, their long production chains and energy balance challenges raise efficiency and economic concerns. Still, they deserve attention, especially in niche applications where they offer advantages. Diversification is crucial to ensuring hydrogen availability not only in urban and industrial hubs but also in remote regions reliant on agriculture or livestock. Considering the type of process, it is essential to account for its energy efficiency, defined as the ratio between the energy content of the produced hydrogen to be destined to final uses and the total energy input, including both the feedstock and all additional energy contributions required during processing. A proper analysis of hydrogen production processes from biomass should consider the ratio between the energy obtained and the total energy used in the process. Assuming a generic efficiency parameter,

this would be given by the ratio of the useful energy produced to the total energy expended in the process, including the feedstock, vapor and the mechanical energy:

3.2.1. Thermochemical Processes

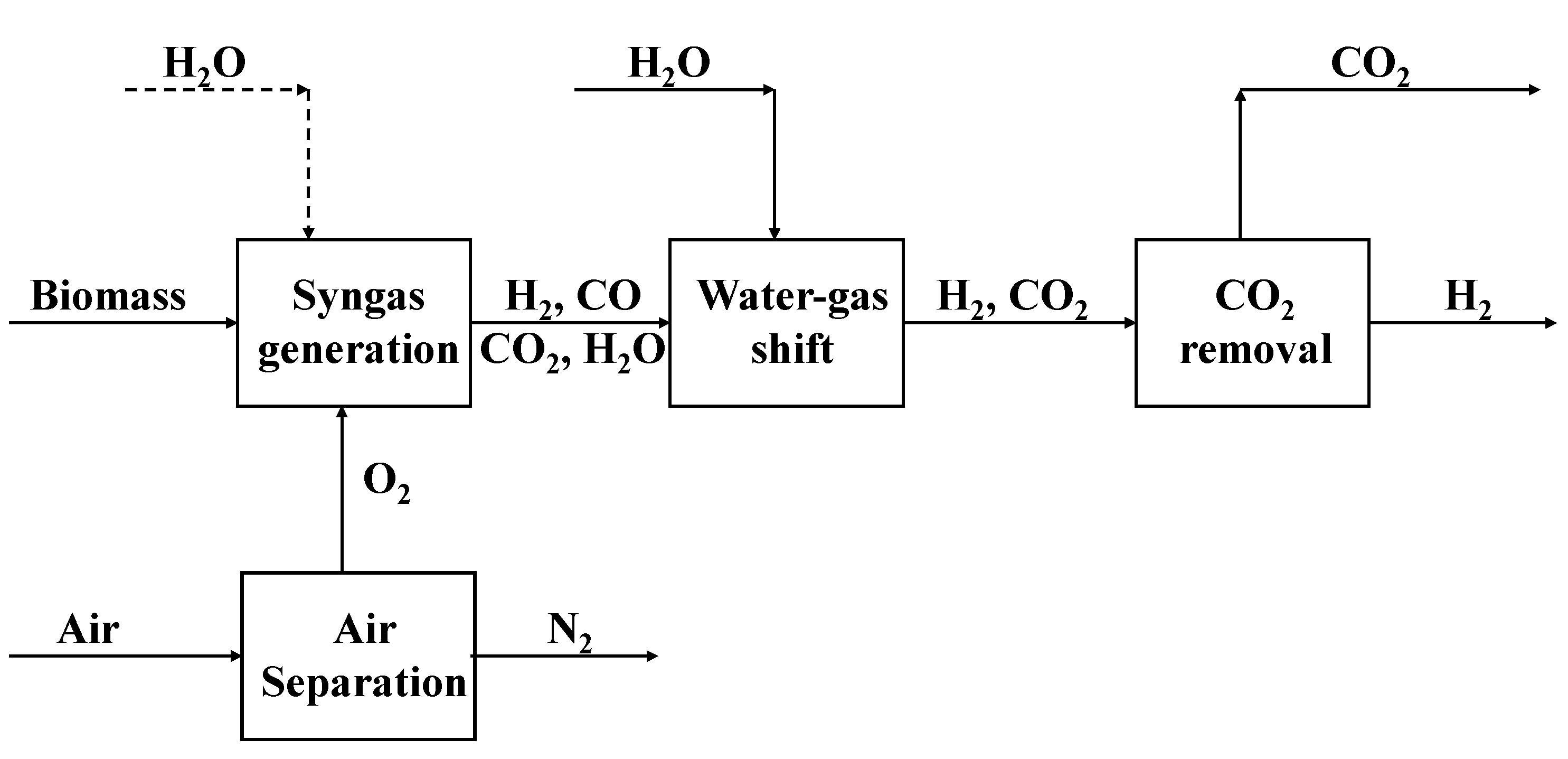

Hydrogen can be generated from biomass or from bio-methane obtained by biomasses through thermochemical conversion, utilizing organic waste and offering benefits like waste reduction, especially in agricultural regions. The raw material for bio-hydrogen production could be obtained from a wide range of sources, e.g., energy crops, agricultural residues, forestry waste and residues. Excluding some typical laboratory processes, the themochemical processes are pyrolysis and gasification, according to the schematic flow described in

Figure 7. Currently, biomass gasification is considered as one of the most promising thermochemical technologies [

31]. The energetic efficiency of a gasification process, generally known as the cold-gas efficiency,

can be determined as:

where LHV

gas and LHV

biomass are the net heats of combustion (lower heating values) of hydrogen and biomass, respectively and the energy required to produce oxygen and steam. Considering the chemical composition of biomasses, shifting them towards hydrogen generation requires the use of accurate chemical pathways, balancing input of feedstock, oxygen (air) and vapor, though they are inefficient from an energy perspective. In general, the biomass gasification reaction can be expressed as:

If it is considered that the fractions of CO

2, O

2 and H

2O formed in the gasification are mainly the products of the combustion to get the necessary energy to perform the gasification and cover the energy losses are included in the efficiency of the gasification reactor, and that the CH

4 production is negligible, the reaction to obtain hydrogen from biomass can be reduced to:

followed by the shift reaction:

Despite the topic being widely debated, there is a lack of experimental data on gasification processes aimed at hydrogen production. Therefore, we must rely on analyses that consider energy balances, which allow for upper-bound estimates at the mass balance level. These estimates can then be extrapolated into energy balances that often appear overly optimistic. Referring to biomass, whose chemical composition is extrapolated from [

32], and provided in

Table 8, it is possible to estimate hydrogen production from biomass, like reported in

Table 9. n real processes, all associated energy uses must be considered. Hydrogen production from biomass is inherently limited by the hydrogen content of the feedstock, typically 5–8% of dry biomass. While theoretical yields may seem promising, overall process efficiency drops below 10% when factoring in all energy inputs, many hard to quantify. Even in an ideal scenario where all hydrogen is extracted, the energy yield remains around 5%. Current technology enables hydrogen production, but actual yields are lower, and purification further reduces overall efficiency.

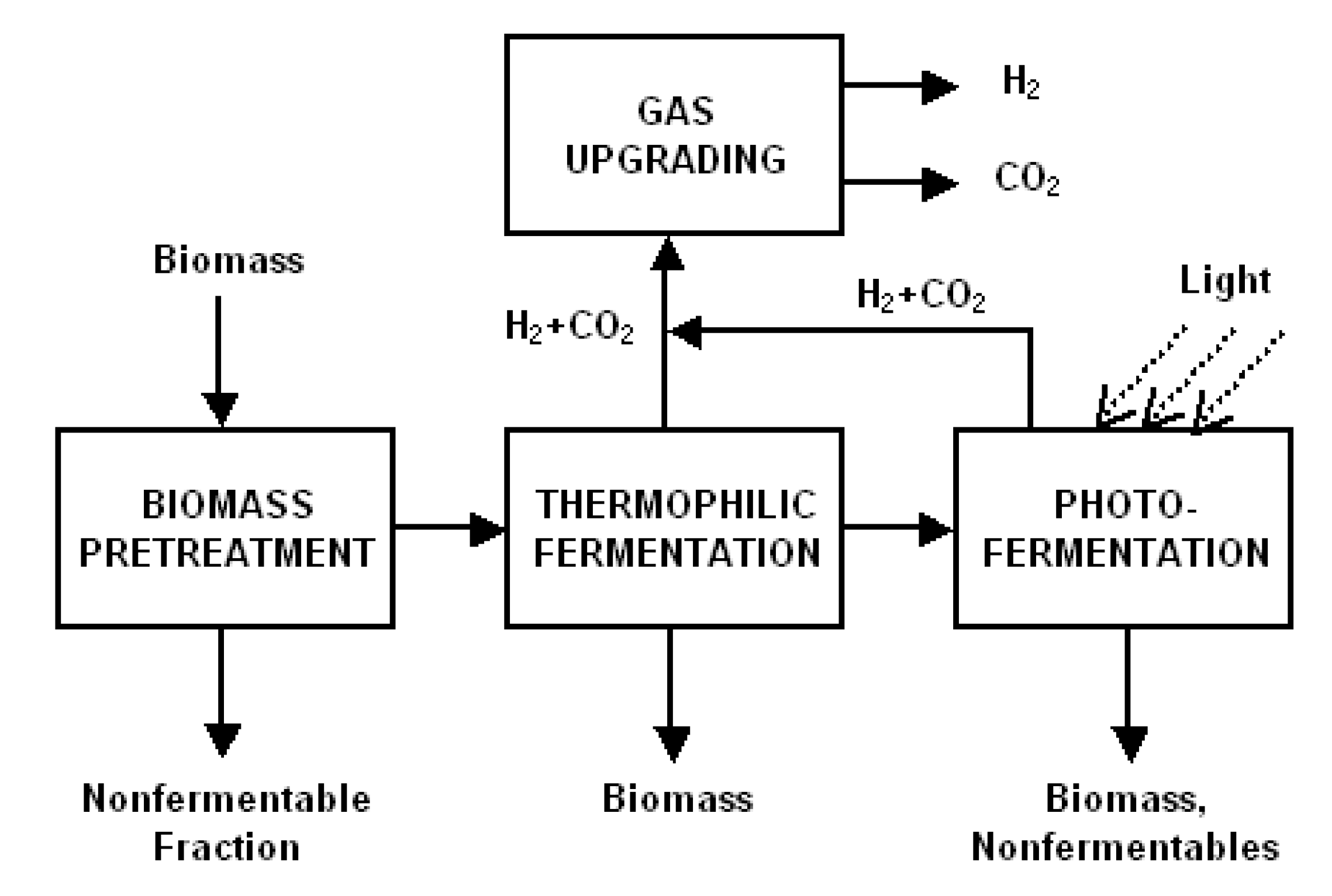

3.2.2. Biological Processes

Similar raw material considered for thermochemical conversion can be used for Bio-Hydrogen production through biological processes, like [

33]. Biological hydrogen production methods involve distinct processes based on the conversion of glucose and acetic acid. Biological hydrogen production processes are diverse and largely rely on solar radiation as the primary energy input, coupled with the catalytic action of various bacteria that convert substrates like glucose and acetic acid into hydrogen (

Table 10). Biological processes can also be combined, as demonstrated in

Figure 8.

Table 11 provides a general description of each process and the energy yield.

3.2.3. Photoelectrochemical Systems

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) processes have the peculiarity of converting solar energy into hydrogen via water splitting, relying on semiconductor materials to generate electron-hole pairs. A photoelectrochemical (PEC) system combines the harvesting of solar energy with the electrolysis of water. The basics of the process can be found in [

34].

When a semiconductor of the proper characteristics is immersed in an aqueous electrolyte and irradiated with sunlight, the energy can be sufficient to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Depending on the type of semiconductor material and the solar intensity, this current density is 10-30 mA/cm2. At these current densities, the voltage required for electrolysis is much lower, and therefore, the corresponding electrolysis efficiency is much higher. Efficiency is measured by solar-to-hydrogen (STH) conversion, currently at 10–20% in labs devices, and incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE), often 50–90% for specific wavelengths. Key challenges include optimizing bandgap (1.6–2.2 eV), reducing charge recombination, and improving stability against photodegradation. Materials like TiO₂ offer durability but low efficiency, while perovskites and GaAs achieve higher performance but lack stability. Advances in catalysis, light absorption, and system design are crucial to achieving scalable, high-efficiency hydrogen production for renewable energy applications. The solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency (η

STH) is commonly used as an indicator to evaluate the performance of PEC devices. The formula is as follows:

where ΔG is the Gibbs free energy of water splitting, Y

H2 is the yield of hydrogen (mol s

−1), I

sun is the intensity of the incident light, expressen in W/m

2 and S is the irradiated area. In a recent review, [

35], several laboratory-scale devices are cited, featuring diverse configurations and materials, such as GaInP/GaInAs, MAPbI3, CuInGa, and BiVO4, with hydrogen conversion efficiencies ranging from 1% to 16%. The interest in those systems is since they use solar energy to split water directly, integrating hydrogen production with renewable energy, though scalability and efficiency remain challenges, [

36,

37]. It is advantageous to develop photoelectrochemical conversion systems that harness both direct solar radiation and the electrical power generated by a photovoltaic system. This integrated approach can enhance overall efficiency by fully utilizing the available renewable energy resources. From a more practical perspective, the efficiency of a photoelectrochemical conversion system can be expressed as

where

is the electricity input is applied to the reactor from a PV module,

is the solar irradiance and A is the illuminated electrode area. The PEC conversion system could become of significant interest if conversion efficiencies reach 20%. Although photoelectrochemical devices that convert sunlight into hydrogen are promising on a small scale, they appear to be quite far from achieving widespread scalability.

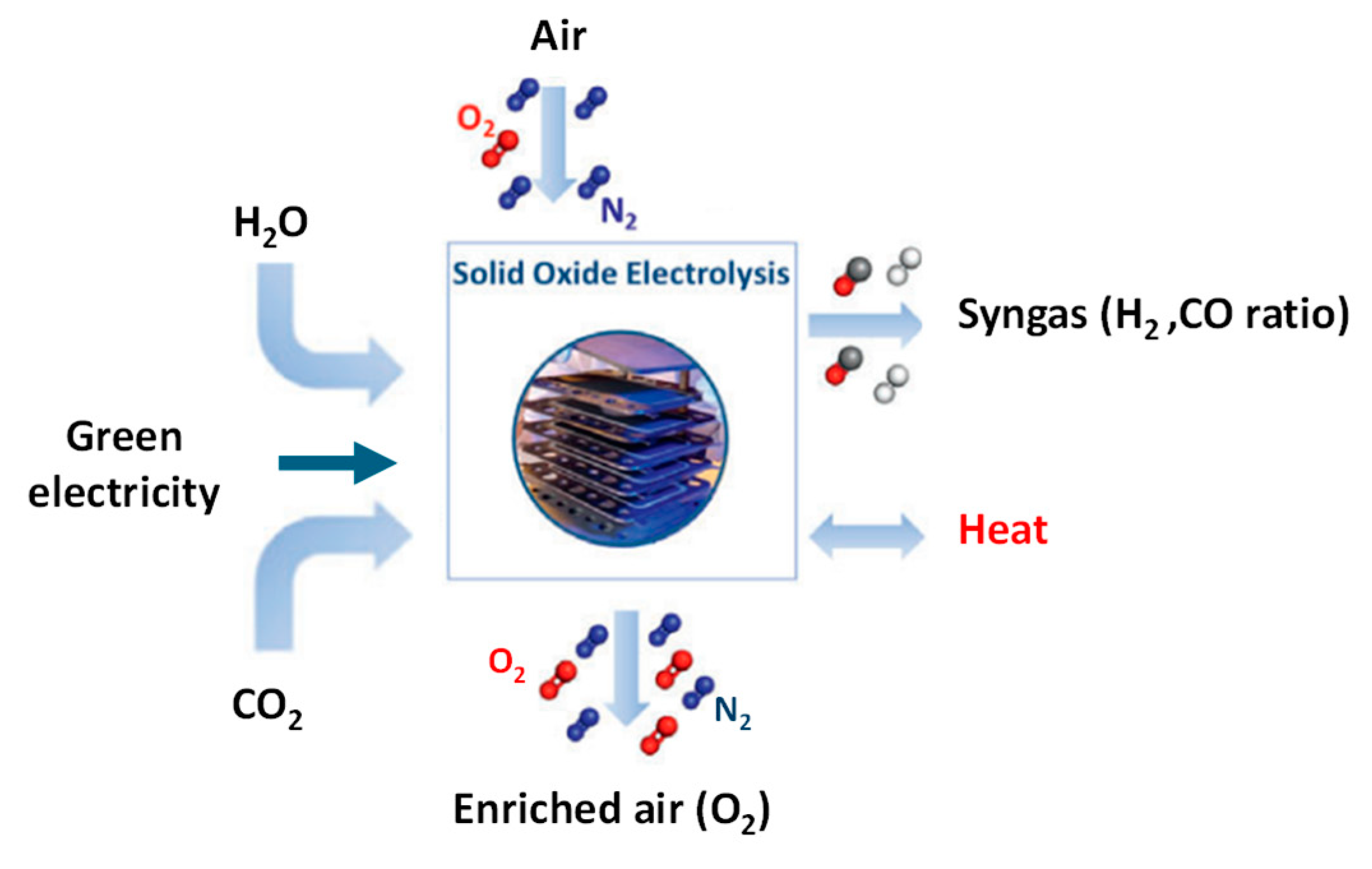

3.2.4. Electrolytic Production from CO2 and Water

This concept involves converting CO

2 and water into hydrogen, aiming to address carbon emissions, but it is still largely experimental and energy-intensive (

Figure 8). Co-electrolysis of CO₂ and water uses electricity, often from renewable sources, to simultaneously reduce CO₂ and H₂O into hydrogen and other carbon-based products. At the anode, water oxidation produces oxygen, protons, and electrons, while CO₂ reduction at the cathode generates hydrogen and carbon monoxide (CO), or other compounds like methane.

This paper offers an in-depth exploration of the fundamentals, performance metrics, and challenges of co-electrolysis, [

38]. Current system efficiencies are typically below 50% with respect to the electricity generated, due to the high overpotentials needed for CO₂ activation. While the co-electrolysis process appears less efficient than traditional electrolysis, its relevance grows in the context of decarbonization, as it offers a way to transform CO₂ emissions into valuable products, contributing to carbon reduction and a more sustainable energy system. This process can recycle CO₂ emissions, supporting a carbon-neutral fuel cycle. Ongoing research focuses on enhancing catalyst selectivity, stability, and overall efficiency [

39]. Each of these technologies has specific targets and applications, but they share the challenge of overcoming energy inefficiencies and high operational costs. Despite the various studies on the subject, as summarized in

Figure 9, it will be very difficult for some of these processes to become widely adopted.

Figure 8.

Alternative Pathways for Green Hydrogen Production from Renewable Sources.

Figure 8.

Alternative Pathways for Green Hydrogen Production from Renewable Sources.

While their viability as widespread solutions is uncertain, they represent critical areas for research and innovation, particularly for localized or specialized hydrogen production scenarios. The goal is to identify and refine pathways that balance technical feasibility with economic practicality, contributing meaningfully to the broader hydrogen economy. The prospects for hydrogen production from renewable, using methods other than electrolysis, do not seem particularly encouraging at this stage. The primary challenges include the low energy density of biomass and the relatively low efficiencies of conversion processes, which will likely limit the production capacity of hydrogen through these methods. Biomass-based processes, such as thermochemical conversion or biological production, may offer benefits in terms of waste reduction, but their overall contribution to large-scale hydrogen production remains constrained by technical and economic limitations. Among the various alternative pathways, co-electrolysis processes, especially when combined with certain "hard-to-abate" processes—could hold potential. Co-electrolysis, which involves the simultaneous conversion of CO2 and water into hydrogen and carbon monoxide, presents an interesting route for integrating hydrogen production with industrial processes. This approach could facilitate the production of green hydrogen while addressing emissions from sectors such as steel or chemicals. Nonetheless, the technology is still in its developmental stages and scaling it up to commercial levels will require significant innovation in both efficiency improvements and cost reductions.

Table 13.

Overview of key processes for green hydrogen production from renewable energy sources, highlighting their physical constraints and main limitations.

Table 13.

Overview of key processes for green hydrogen production from renewable energy sources, highlighting their physical constraints and main limitations.

| Production Method |

Description |

Key Advantages |

Challenges/Considerations |

Maximum

efficiency |

Potential Applications |

| Thermochemical processes using renewable feedstocks |

Hydrogen production from bio-methane or lignocellulosic biomass |

Leverages organic waste materials, reduces waste, utilizes biomass |

Long production chains, energy balance concerns, complex logistics. |

30-40%

(based on feedstock and process) |

Agricultural economies, biomass-rich regions. |

Bio-Hydrogen

production |

Hydrogen production by biological processes (fermentation or microbial electrolysis) |

Aligns with circular economic principles, potential for low-cost local production |

Still in the early stages, low efficiency, scalability issues. |

15-30% |

Rural areas, agricultural economies. |

| Photoelectrochemical systems for solar Hydrogen |

Hydrogen production via solar energy to directly split water by photoelectrochemical systems (PEC) |

Integrates hydrogen production with solar energy, offers promising sustainability |

Scaling and efficiency challenges, high energy input requirements. (early research) |

10-20% |

Remote communities, solar-rich areas. |

| Electrolytic production from CO2 and Water |

Converting CO2 and water into H2 and other reduced products by electrolysis. |

Potential to address carbon emissions while producing hydrogen |

High energy input required, still experimental, energy inefficiency. |

30-40%

(depending on technology and energy source) |

Carbon capture and utilization, experimental setups. |

Summarizing, while alternative methods of hydrogen production from renewable fuels have some potential, their current limitations—particularly in terms of energy efficiency and scalability—suggest that they are unlikely to play a major role soon. Co-electrolysis, though promising, represents a niche technology that may be more relevant in specific applications rather than as a broad solution for green hydrogen production.

4. Limitations of Green Hydrogen for Energy Transition: Technical Challenges

There are numerous limitations to hydrogen that may prevent it from becoming a dominant element in the energy transition. These limitations encompass technical and technological aspects related to its production by electrolysis, the entire production cycle, and its final uses, as well as safety concerns. These factors significantly influence the economic impact and reduce the cost-effectiveness of hydrogen produced from renewable sources. At the core of these challenges are surely technical issues related to the energy chain, diffusely discussed in the previous section. The energy losses associated with hydrogen production, storage, and transportation are substantial, making it a less efficient energy carrier compared to other forms of energy. Moreover, the technological infrastructure needed to support hydrogen on a large scale remains underdeveloped, with many of the processes still in early stages of commercialization. Additionally, there is a strategic challenge in the way hydrogen is currently being positioned.

Hydrogen is often presented as a universal solution that could be applied across various sectors, but this broad, indiscriminate vision can be counterproductive. A lack of clear, focused objectives often hampers the development of effective solutions. In our view, hydrogen’s path to widespread adoption will be best served by a more targeted approach—one that connects hydrogen to specific sectors where its potential impact can be maximized. Identifying these key sectors and creating tailored strategies for hydrogen integration is crucial. For example, hydrogen could play a key role in decarbonizing "hard-to-abate" industrial sectors or in supporting renewable energy systems. Only through a clear, focused strategy will hydrogen be able to fulfil its role in the global energy transition. In addition to production challenges, hydrogen must be transported and stored. This requires the establishment of an extensive industrial supply chain, which is currently either non-existent or extremely limited. Hydrogen storage solutions, such as high-pressure tanks or cryogenic storage, and transportation infrastructure, including pipelines and fueling stations, are still under development and pose significant logistical and safety challenges. Many of these technologies are still experimental, with no guarantee of their efficacy on a large scale. Developing the necessary infrastructure, improving production efficiencies, and ensuring safety in storage and transportation demand tens of billions of euros. Despite these investments, it remains unclear whether the benefits associated with hydrogen's widespread adoption will meet the high expectations set by its proponents. While hydrogen promises substantial climate benefits and potential advantages for citizens, the economic feasibility and real-world efficacy of these benefits are still under scrutiny. In conclusion, while hydrogen has significant potential as part of the energy transition, the current technical, technological, and economic barriers suggest that it may not be the leading solution.

Table 14.

Current Prospects for Hydrogen.

Table 14.

Current Prospects for Hydrogen.

| Aspect |

Current Situation |

Challenges |

| Production Methods |

Primarily electrolysis, limited alternative methods |

High energy costs, low efficiency, limited scalability |

| Sector Focus |

General application in various sectors |

Lack of sector-specific strategies and clear objectives |

| Storage & Transport |

Storage at low pressure (~30 bar), costly transport |

Energy loss, high costs, limited infrastructure |

| Technical Limitations |

Early-stage technology, high energy consumption |

High capital investment, technical scalability issues |

| Economic Feasibility |

Hydrogen produced from renewable sources is still costly |

High production, storage, and transport costs |

Table 15.

Prospects for Hydrogen.

Table 15.

Prospects for Hydrogen.

| Aspect |

Future Potential |

Opportunities |

| Target Sectors |

Hard-to-abate industries, thermal energy generation |

Decarbonizing industrial sectors, reducing reliance on natural gas |

| Energy Chain Integration |

Hydrogen as both energy carrier and chemical agent in processes |

Support renewable energy integration, enhance energy storage systems |

| Technological Advances |

Advanced electrolysis, bio-hydrogen, photoelectrochemical systems |

Improved efficiency, lower costs, new production technologies |

| Strategic Focus |

Sector-specific strategies for targeted hydrogen application |

Clear objectives, focused policy and regulatory framework |

| Economic Viability |

Targeted applications in specific sectors, gradual scaling up |

Economies of scale, improved cost-effectiveness over time |

4.1. Hydrogen Storage and Infrastructure Challenges

An often-underestimated aspect of hydrogen utilization is that its application requires a comprehensive view of the entire energy chain. Beyond production, multiple critical steps—such as storage, transfer, and distribution—introduce significant technical and economic challenges. In many cases, upgrading existing infrastructure to accommodate hydrogen can raise capital costs by 20–30% compared to conventional systems, underscoring that these modifications are far from trivial. One major challenge is storage. Hydrogen produced by standard electrolyzers typically exits at a relatively low pressure (around 30 bar), requiring further compression—often to pressures above 200 bar—to meet storage and pipeline specifications. This additional compression can demand an extra 10–15% of the total energy input, a factor that must be carefully considered when assessing overall system efficiency. Numerous studies have analyzed hydrogen compression technologies, highlighting trade-offs between energy consumption and storage density that are critical for both local distribution and long-distance transport. This research demonstrates that fully realizing the potential of green hydrogen hinges not only on production advancements but also on substantial improvements in storage technologies and infrastructure.

4.2. Green Hydrogen and Blending with Natural Gas

Green hydrogen is progressively being integrated into blended combustion systems for both heat and power generation. Owing to its unique properties—such as higher diffusivity, increased flame speed, and elevated adiabatic flame temperatures, its use in burners and combustors poses significant challenges that require innovative design solutions. Advanced experimental and modeling efforts are addressing these issues by optimizing flame structure, enhancing combustion stability (e.g., mitigating flashback and blowoff), and reducing NOx emissions. Blending hydrogen with conventional fuels like natural gas or biogas is emerging as a transitional strategy, offering improved performance while facilitating a smoother shift toward fully renewable energy systems.

4.3. Green Hydrogen and Final Uses in Energy Systems: Applications in Industrial Decarbonization

Recent advances in integrating green hydrogen into renewable energy systems have demonstrated its potential as a flexible energy carrier capable of balancing the intermittency of renewable sources and stabilizing energy grids through the storage of surplus wind or solar power. A growing body of literature—including significant contributions from Italian research groups—has explored diverse aspects of this integration. For instance, techno-economic analyses have evaluated solid oxide fuel cell cogeneration systems for decarbonizing energy-intensive industries, [

40] and assessed the decarbonization potential via hydrogen integration in different sectors like for example paper [

41] and steel sectors, [

17,

42]. Other studies have addressed energy modeling challenges for fully decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors, [

43] and investigated the viability of essential infrastructure elements such as hydrogen refueling stations, [

44,

45], liquid hydrogen supply chains for ship refueling, [

46]. Although these studies have generated significant interesting contribution and advanced our understanding, the transformative impacts expected from hydrogen integration are not yet fully realized. A balanced perspective that considers efficiency, infrastructure, and economic viability at multiple scales remains essential for unlocking hydrogen’s full potential in the energy transition.

4.4. Cross cutting Activities for Hydrogen Introduction in Energy Systems

Achieving widespread hydrogen adoption goes beyond technical breakthroughs and demands coordinated progress in several cross-cutting areas. Alongside improving production technologies, ongoing research must update regulatory frameworks and develop normative standards to streamline hydrogen’s integration. Safety initiatives, such as creating advanced sensors and comprehensive guidelines for industrial and commercial use, are essential. Similarly, life cycle assessments and strategies for material recovery are critical for ensuring environmental sustainability and circularity. Finally, planning tools that support techno-economic analyses and strategic investment are needed to scale hydrogen projects. Together, these efforts provide a crucial roadmap for overcoming non-technical barriers and realizing hydrogen’s full potential in the energy transition.

4.5. Policy and Market Considerations

Across these studies, a recurring theme is the importance of coordinated policy and market development to support green hydrogen. Authors emphasize the need to create favorable market conditions through subsidies, carbon pricing and targeted incentives to accelerate adoption. However, it must be recognized that hydrogen's potential cannot rely solely on these incentives. For the hydrogen value chain to become truly sustaining, a critical focus must be placed on the bankability of investments. This means developing robust financial models and risk-mitigation strategies that attract private capital and ensure long-term project viability. Achieving such bankability is complex and, if not properly addressed, could emerge as another barrier to the widespread adoption of hydrogen technologies. Therefore, alongside policy support, concerted efforts are needed to secure the financial sustainability of the hydrogen sector, ensuring that investments are both attractive and resilient over time, paving the way for a complete shift to fully renewable solutions without overreliance on transitional technologies like blue hydrogen.

5. Limitations of Green Hydrogen: Economic Challenges

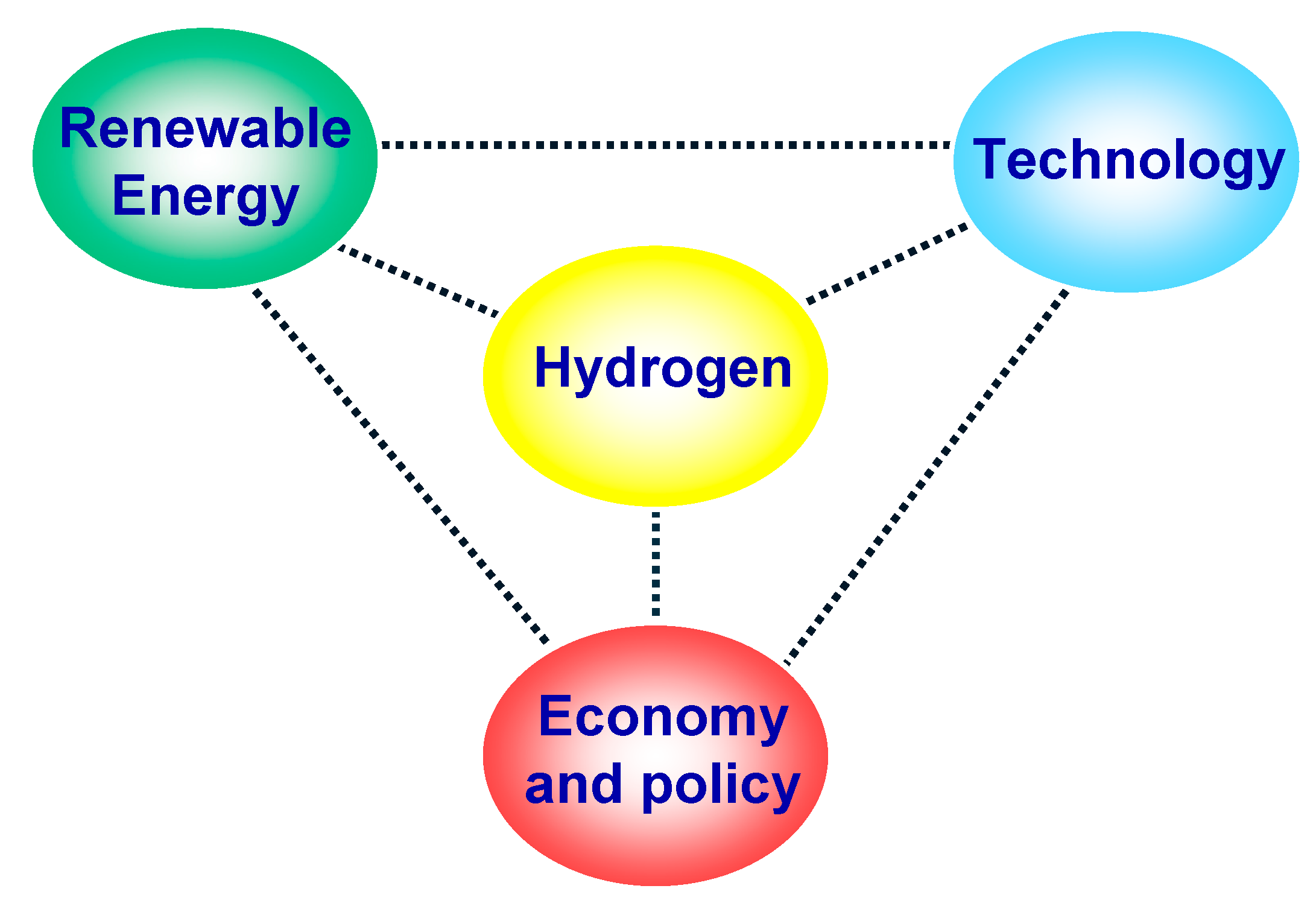

This renewed interest reflects its foundational role as an energy carrier, though challenges such as energy losses, storage, and economic feasibility remain central to the discussion. Hydrogen has returned to the center of the debate, attracting significant interest. However, discussions often overlap with different perspectives—renewable sources, technological aspects of the supply chain, and economic and regulatory factors. As illustrated in

Figure 1, hydrogen sits at the heart of a complex equilibrium. What is clear is that green hydrogen can become competitive, with costs reaching an acceptable level. A relevant problem connected to the future hydrogen development is the high economic cost. The transition to a green hydrogen economy still faces numerous challenges when considering green hydrogen as a potential significant fuel source to replace fossil fuel sources in industrial applications.

Figure 9.

The marginal contribution of green hydrogen to global hydrogen production.

Figure 9.

The marginal contribution of green hydrogen to global hydrogen production.

These challenges include financial, technological, social and political aspects, more specifically: (i) the cost of green hydrogen is still quite high compared to other fuels; (ii) the demand for green hydrogen in the future is not guaranteed; (iii) the impacts of green hydrogen projects on water and land resources; (iv) the lack of international regulations and standards; and (v) the general public acceptance of hydrogen. One of the methods to estimate the hydrogen cost is the levelized cost of hydrogen. Hydrogen is expected to become particularly significant in industrial sectors as a substitute for natural gas. However, the persistently low price of natural gas poses a major challenge, complicating the economic case for such a transition. The problem of analysing the economic aspects related to hydrogen production appears to be quite difficult due the uncertainty correlated to the emerging technologies. The production cost analysis for various hydrogen technologies is based on a levelized cost approach, where all expenditures (both CAPEX and OPEX) as well as revenues from co-products are discounted using a discount rate reflecting the average risk of hydrogen production projects.

Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) as Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) appears to be a good tool for comparing energy technologies like the use of hydrogen, more than traditional financial metrics like Net Present Value (NPV). LCOH provides a standardized cost per unit of hydrogen produced, making comparisons across technologies straightforward. One key advantage of LCOH analysis is its independence from market prices, focusing solely on production costs. This makes it highly useful for policy makers and investors assessing long-term energy strategies. Additionally, LCOH accounts for all costs over an asset’s lifetime, including capital, operation, and maintenance, providing a clearer picture of economic feasibility. Moreover, it is particularly useful for emerging technologies, helping evaluate when renewable energy or hydrogen production will become cost competitive. In contrast, NPV relies on uncertain future revenues. The formula for estimating

LCOH (in €/kg

H2) is presented:

where

[kg] is the mass of hydrogen produced during j-th year,

is the lifetime of the project,

is the investment rate set at 5%,

is the investment cost of the k-th component [€],

are the operation and maintenance costs for the k-th component during the j-th year, and

are the project costs estimated at 12.5% of

CAPEX excluding PV and battery. Current estimates for green hydrogen vary widely.

The European Hydrogen Observatory, [

47] estimates green hydrogen costs at around 7 €/kg, with a range between 4.18 and 9.60 €/kg. BloombergNEF in [

48] on the other hand, reports a wider range of 4.5–12

$/kg. While some optimistic forecasts suggest prices as low as 3 €/kg, actual projects in Central Europe indicate costs between 5 and 8 €/kg by 2030. These discrepancies—further exacerbated by additional expenses such as transport and storage—highlight the uncertainties in achieving cost-competitive green hydrogen.

6. Solution for Green Hydrogen Promotion in Connection with Specific Sectors

Green hydrogen holds a significant promise for enhancing renewable energy integration by acting as a buffer to smooth supply fluctuations. However, its successful adoption requires more than technological breakthroughs alone—it must be linked to specific, practical applications that result in self-sustaining, cost-effective systems. Although literature is rich with innovative ideas and varied development pathways, not every approach will lead to scalable, viable solutions. In this section, we examine several promising concepts that demonstrate how hydrogen can be effectively integrated into broader energy systems, underscoring that technology, by itself, is not enough.

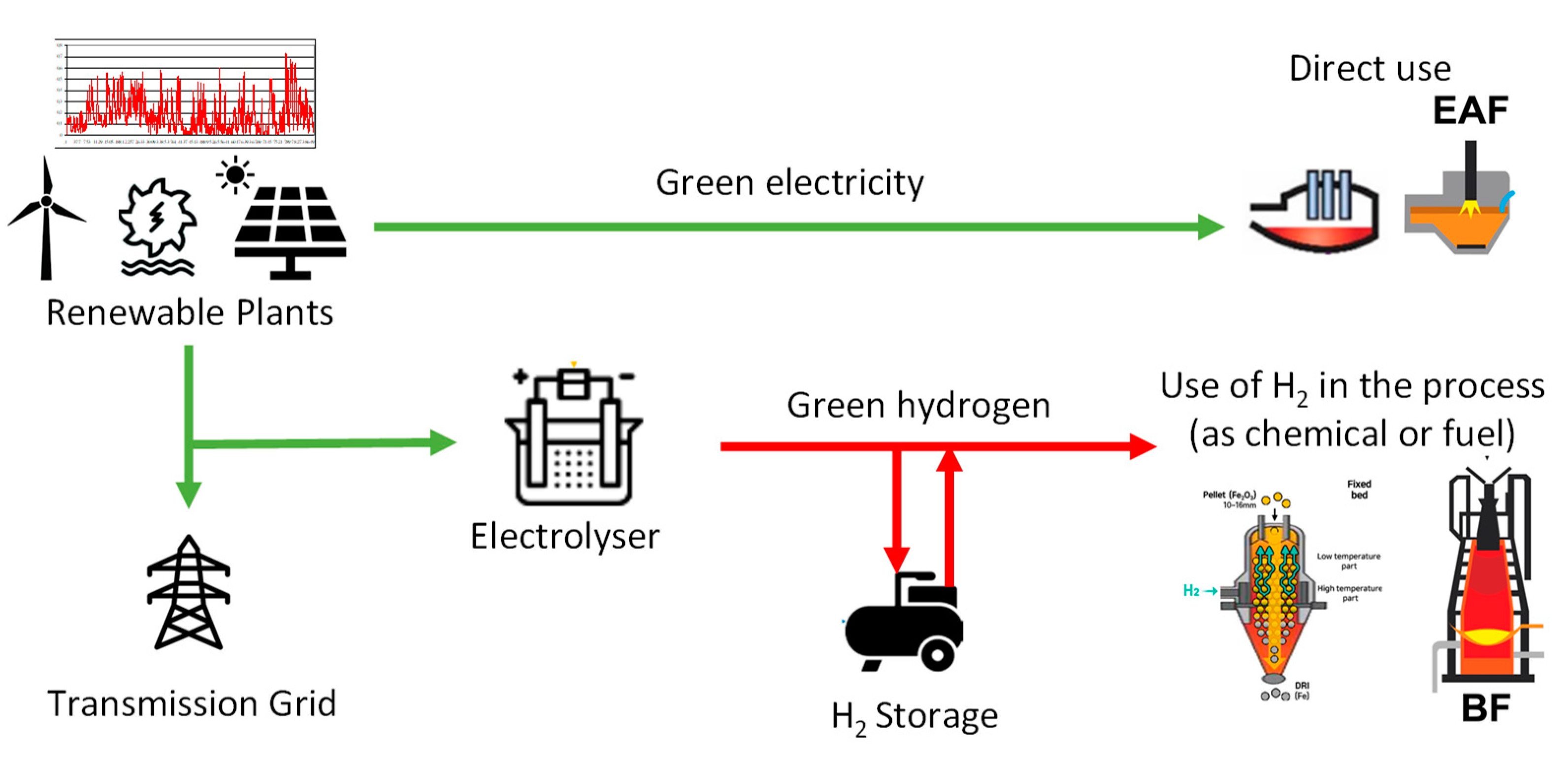

6.1. Large-Scale Energy Storage Integrated with Renewable Sources

One of hydrogen's most compelling advantages lies in its potential for large-scale energy storage, especially in areas with significant renewable energy production, such as wind and solar power. In many regions, there has been a rapid increase in renewable energy capacity, driven by the need to reduce carbon emissions and take advantage of favorable conditions for renewable generation, such as high numbers of full-load hours. These areas were chosen primarily for the bankability of renewable projects, ensuring stable returns for investors. However, as renewable energy generation has expanded, many regions are now reaching the saturation point of their electrical grids, where further integration of renewable sources becomes increasingly difficult due to the limited capacity of existing infrastructure. In these situations, the next logical step is to connect the surplus renewable generation directly to industrial applications. Hydrogen can play a pivotal role in this shift. By using excess renewable electricity to produce hydrogen through electrolysis, energy that would otherwise go unused can be stored and later used in industrial processes, as well as for thermal applications. Hydrogen’s ability to store energy for extended periods—much longer than batteries—makes it an ideal solution for addressing the intermittency of renewable generation.

6.2. Hydrogen Integration in Energy Districts

Hydrogen can also play a crucial role in energy district clusters of buildings or industrial areas with shared energy resources. In these districts, hydrogen can serve as an energy carrier that facilitates the integration of renewable energy, providing a flexible solution for both electricity and heat demands. Whether in the form of district heating or for industrial processes, hydrogen’s ability to decarbonize thermal energy use is a key differentiator from other renewable solutions. Unfortunately, given the considerable challenges in rapidly deploying hydrogen boilers in urban settings, a promising area of interest is the blending of increasing amounts of hydrogen produced from renewable plants into the gas grid, according to the schematic view illustrated in

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Alternative Pathways for Green Hydrogen Production from Renewable Sources.

Figure 10.

Alternative Pathways for Green Hydrogen Production from Renewable Sources.

6.3. Supporting Industrial Decarbonization in “Hard to Abate” Sectors

One of the most challenging aspects of decarbonization is the industrial sector, particularly in “hard-to-abate” industries like steel, cement, and chemicals. Green hydrogen offers a direct path to decarbonize these industries, which are heavily reliant on fossil fuels for both electricity and thermal energy. By replacing carbon-intensive fuels with hydrogen, industries can significantly reduce their emissions, making hydrogen indispensable for achieving relevant decarbonization in these sectors. Another powerful opportunity is the combined production of hydrogen and heat. In sectors where both electricity and thermal energy are required—such as refineries, chemical plants, and certain manufacturing processes—hydrogen can be used to provide both, enabling an efficient and clean energy solution. This integration enhances the value proposition of hydrogen by simultaneously addressing both electricity and heat needs. Hydrogen is a promising decarbonization vector due to its clean combustion and potential to replace fossil fuels in high-temperature industrial processes.

However, its adoption faces significant challenges: its high combustion velocity and low heat transfer efficiency complicate monitoring and performance, while safety issues related to storage and handling add further complexity. Moreover, substantial modifications to existing equipment and materials are needed to mitigate issues like corrosion and brittleness, and the intermittent nature of renewable hydrogen supply remains a concern. In general, the integration of renewable energy and hydrogen into hard-to-abate sectors is a promising avenue for decarbonization. However, it is crucial to understand the significant dimensional constraints of these industries. For example, production facilities in sectors such as steel, cement, glass, and paper operate on a very large scale, with power demands typically ranging from tens to hundreds of megawatts.

Any effective decarbonization strategy must account for these high energy requirements and the substantial capacity of the equipment involved.

Table 16 provides a summary of the typical scale dimensions for these sectors. Understanding these dimensional benchmarks is essential for designing renewable energy and hydrogen systems that can effectively meet the large-scale energy demands of these industries.

6.4. Hydrogen Integration with Mobility Systems

Hydrogen’s potential in the mobility sector, particularly in heavy-duty transportation, is well-documented. From trucks to trains and even ships, hydrogen-powered vehicles offer a practical alternative to battery-electric solutions, especially for long-range or high-load applications. By developing a network of refueling stations and improving hydrogen fuel cell technology, we can accelerate the decarbonization of transport and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Achieving a significant impact in the transport sector requires substantial investment and a large volume of hydrogen, as demonstrated in the table below. Even under the optimistic assumption of using 1 kg of hydrogen per 100 km traveled, the required quantities remain considerable.

Table 17 includes some dimensional parameters to help illustrate what minimal hydrogen penetration in the transport sector might entail. This analysis considers light-duty vehicles (assuming a consumption of 1 kg of hydrogen per 100 km) and heavy-duty vehicles (assuming a consumption rate that is double that of light vehicles).

7. Discussion and Future Perspectives

Although there are genuine opportunities to develop supply chains incorporating green hydrogen, it is crucial to consider the magnitude of the challenges involved. In typical scenarios, effective solutions would require the deployment of high-capacity plants.

While all the approaches analyzed in

Section 6 are conceptually interesting, assessing the actual impact and sustainability of these plant solutions requires a thorough evaluation of their producibility. Let’s provide some rough estimates by attempting sizing calculations to understand the scale of the necessary installations. Let's take a photovoltaic plant as a reference. The production of a PV plant, is dependent on the site of installations can be estimated by means of the following equation

In

Table 18, some data are provided to illustrate the amount of hydrogen that can be generated per installed kW peak, depending on the solar irradiation of the location. The values highlight how hydrogen production varies significantly based on solar availability, affecting the overall efficiency and yield of the system.

It is also important to consider that before the final use, hydrogen needs to be compressed. As shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the supply chain includes a compression system capable of storing hydrogen at a pressure of at least 80 bars, ensuring compatibility with standard industrial storage and distribution requirements. The estimation of the energy required for compression can be derived by the following model, according to [

18]. The minimum work for compression can be obtained in isothermal compression such as:

To obtain a realistic estimation of the work required it will be necessary to consider the efficiency of the compression (that according to data available in the literature can be estimated as 0.6), [

18]. So that the specific work really required can be estimated as:

So that the efficiency of the compressor phase can be estimated as

As illustrated in

Figure 13, due to losses occurring at various stages of production, conversion, and transportation, the energy that ultimately reaches end-use applications is significantly reduced compared to the original primary energy input. In most cases, these losses amount to at least 40%, meaning that only a fraction of the initial energy is effectively utilized. This fundamental constraint must be carefully considered to avoid inefficient applications and to ensure that hydrogen is directed toward the most suitable and impactful uses. Similar considerations can be made for PV plants, wind and hydroelectric plants. The last two plants typically operate for a greater number of hours than PV systems. When evaluating the role of hydrogen, it is crucial to consider the entire energy chain. While hydrogen is increasingly regarded as a key option for decarbonizing sectors where direct electrification or other low-carbon alternatives are not viable, many of the fundamental challenges that have hindered its widespread adoption in the past remain unchanged. Despite growing momentum driven by climate concerns and the expansion of renewable energy, hydrogen’s physical and chemical properties continue to limit its scalability and economic feasibility in several applications, [

49]. A pragmatic approach to hydrogen deployment should recognize four distinct categories of applications.

Established Industrial Uses with Clear Benefits – The most effective and immediate way to reduce emissions with low-carbon hydrogen is to replace its current fossil-based production in industries where it is already essential. This includes sectors like oil refining, ammonia and methanol synthesis, and steelmaking, where hydrogen plays a fundamental role in existing processes.

Sectors with Potential but Significant Challenges – Some industries, such as long-haul transport by air, sea, and heavy-duty road vehicles, could benefit from hydrogen-based solutions, but technical and cost barriers remain considerable, requiring further advancements before large-scale deployment becomes viable.

Specialized or Limited-Scale Applications – In certain contexts, hydrogen may be useful for specific energy-related purposes, such as balancing electricity grids or providing long-duration energy storage. However, its role in these areas is highly situational and dependent on technological progress and economic feasibility.

Uses with Weak Justification – Some proposed applications of hydrogen, such as its use in residential heating or passenger vehicles, appear inefficient compared to more practical and cost-effective alternatives like direct electrification through heat pumps and battery electric vehicles.

Hydrogen will play a role in the transition to a low-carbon economy, but a realistic and evidence-based approach is necessary to ensure that resources are directed toward applications where it can deliver genuine and cost-effective emissions reductions.

8. Conclusions

Decarbonization strategies, such as those promoted in Europe through the Green Deal, increasingly position hydrogen as a key element. While often described as a clean fuel due to its combustion producing only water vapor, hydrogen is not a naturally available resource and must be produced, making it an energy carrier. Not all production methods guarantee a low environmental impact, and the enthusiasm surrounding hydrogen’s role in decarbonization often relies more on theoretical potential than on realistic application. This optimism can lead to misjudging the infrastructure needs, and scalability challenges. A critical issue is the frequent overestimation of future hydrogen availability and the underestimation of technical and infrastructure constraints.

Moreover, excessive reliance on hydrogen risks diverting resources from more efficient solutions, such as direct electrification in many applications. A pragmatic approach requires assessments based on empirical data and careful trade-offs between technologies to ensure hydrogen is deployed where it adds real value, rather than as a universal solution. Ultimately, hydrogen’s role in the energy transition must be evaluated based on its overall energy efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and scalability and on the main technical and economic considerations.

- -

Energy Efficiency Challenges: water electrolysis, the main method for producing green hydrogen, suffers from high energy losses. Converting renewable electricity into hydrogen and then using it for final uses results in an overall efficiency of around 25-35%, meaning that at least 65-75% of the original energy is lost.

- -

Production Scalability: while alternative methods such as biomass gasification or solar-driven processes exist, they typically operate in the kW range, making them unsuitable for large-scale applications. Electrolysis remains the only viable method for industrial-scale production.

- -

Hydrogen and Hard-to-Abate Sectors: Key industrial sectors such as refining, ammonia, methanol, and steel production require continuous energy supply at scales between 10 MW and 1000 MW, necessitating large electrolyzers and infrastructure that are still in early development. Lower power level, but of 1-100 MW scale concerns different hard to abate sectors like glass, paper and cement industrial processes.

- -

Hydrogen in Transport: while hydrogen fuel cells offer a zero-emission solution for transportation, their efficiency is significantly lower than direct electrification. Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) achieve an overall efficiency of around 70-80%, while hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) operate at about 25-35% due to energy losses in production, compression, and conversion. This makes FCEVs less competitive in passenger cars and short-haul transport, where BEVs dominate. However, hydrogen could play a role in the heavy transport sector.

- -

Hydrogen in the Civil Sector: hydrogen’s role in residential and commercial heating remains controversial. While it can be blended into natural gas networks (typically up to 20% by volume without major modifications) the use of green hydrogen for space heating would require large-scale production and distribution systems, making it an unlikely solution.

- -

Economic Viability: Current green hydrogen production costs range from €5 to €10 per kg, significantly higher than fossil-based hydrogen (around €1.5–2/kg). For hydrogen to be competitive, production costs must fall below €2/kg, which will require advances in electrolyzer technology, lower electricity prices, and economies of scale.

- -

Infrastructure Gaps: large-scale hydrogen deployment depends on the development of a robust industrial supply chain, including storage and transport infrastructure. Currently, over 95% of global hydrogen is produced using fossil fuels (gray and blue hydrogen), highlighting the gap between ambition and reality.

Concluding, while hydrogen has strong potential for decarbonization, particularly as an energy buffer for renewables, addressing its dimensional scaling challenges will be crucial for widespread adoption. Industrial applications require large, cost-effective production facilities, while the transport and storage of hydrogen remain major technical and economic hurdles. Many key technologies are still in an experimental phase, with no guarantee of cost reductions or scalability in the near term. Despite these uncertainties, significant public and private investments are driving the sector forward. However, to avoid repeating past cycles of enthusiasm followed by disillusionment, hydrogen must be integrated strategically within a broader energy system. This means prioritizing applications where it provides clear added value, investing in infrastructure, and making data-driven decisions. Only through such a coordinated, pragmatic approach can hydrogen play a meaningful role in a low-carbon future.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3—Call for tender No. 1561 of 11.10.2022 of Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR); and by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. Award Number: Project code PE0000021, Concession Decree No. 1561 of 11.10.2022 adopted by Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR), CUP I53C22001450006, according to attachment E of Decree No. 1561/2022, Project title “Network 4 Energy Sustainable Transition—NEST”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Symbols and Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A |

Electrode area [m2] |

| ALK |

Alkaline |

| BOS |

Balance of System |

| CAPEX |

Capital expenditure [€] |

| C |

Cost [€] |

| CCS |

Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CGE |

Cold Gas Efficiency |

| Comp |

of compressor |

| E |

Energy generated [kWh] |

| Feed |

Feedstock |

| Fuel |

of the input fuel |

| HSN

|

Irradiance [kWh/ (m2 day)] |

| Hyd |

Reference cost of hydrogen [€/kg] |

| Isun

|

Specific solar power input [W/m2] |

| ICE |

Internal Combustion Engines |

| lc,id |

Specific work for compression, ideal value [kJ/kg] |

| lc,real |

Specific work for compression, real value [kJ/kg] |

| LCOE |

Levelized Cost of Energy [€/kWh] |

| LCOH |

Levelized cost of hydrogen [€/kg] |

| LHV |

Lower Heating Value |

|

Mass flow rate [kg/s] |

| M |

Mass [kg] |

| Mech |

Mechanical |

| N |

lifetime of the project [years] |

| NPV |

Net present value [€] |

| O&M |

Operation and management |

| OPEX |

Operational expenditure [€] |

| P |

Power [W] |

| P |

pressure [bar] |

| PEC |

Photo Electro Chemical |

| PEM |

Polymer Electrolyte Membrane |

| Proj |

of the project |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| R |

Constant of the gas [J/kg K] |

| RES |

Renewable Energy Systems |

| S |

Surface [m2] |

| SEC |

Specific electricity consumption [kWh/kg H2] |

| SMR |

Steam Methane Reforming |

| SO |

Solid Oxide |

| STH |

Solar to Hydrogen |

| T |

Temperature [K] |

| Vap |

of the vapour |

| ΔG |

Gibbs free energy [kJ/kmol] |

| Ψ |

Generic efficiency parameter |

| H |

Efficiency |

References

- Bockris, J. O. M. A hydrogen economy. Science 1972, 176, 1323–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, C. On hydrogen and energy systems. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 1976, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C.-J.; Klaiβ, H.; Nitsch, J. Hydrogen as an energy carrier: What is known? What do we need to learn? A consideration of the parameters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1990, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsugi, C.; Harumi, A.; Kenzo, F. WE-NET: Japanese hydrogen program. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 1998, 23, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veziroǧlu, T.N. Quarter century of hydrogen movement 1974–2000. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2000, 25, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. (2003). The hydrogen economy. Penguin.

- Andrews, J.; Shabani, B. Re-envisioning the role of hydrogen in a sustainable energy economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1184–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, The European Green Deal, Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent, available at https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (last accessed on 30 January 2025).

- European Council of the European Union, Fit for 55, available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fit-for-55/ (last accessed on 30 January 2025).

- IEA (2024), IEA World Energy Statistics & Balances“, International Energy Agency, www.iea.org/data-andstatistics/data-product/world-energy-balances (last accessed on 30 January 2025).

- IRENA (2024), Renewable energy statistics 2024, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, www.irena.org/Publications/2024/Jul/Renewable-energy-statistics-2024 (last accessed on 30 January 2025).

- REN21 (2024), Renewables 2024 Global Status Report,Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century, www.ren21.net/gsr-2024/modules/global_overview (last accessed on 30 January 2025).