Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Mushroom Samples

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Growth and Maintenance Conditions of Mushroom Strains

2.3.2. Production of β-D-glucan from Basidiomycete Mushroom Strains in Culture Media Containing Agro-Industrial Wastes

2.3.3. Isolation of of β-D-Glucan from Basidiomycete Mushroom Strains

2.3.4. Total Polysaccharides and Protein Assays

2.3.5. Congo Red Assay for Specific Determination of of β-D-glucan with Triple Helical Structure

2.3.6. Alcian Blue Dye Colorimetric Assay for of β-D-Glucan

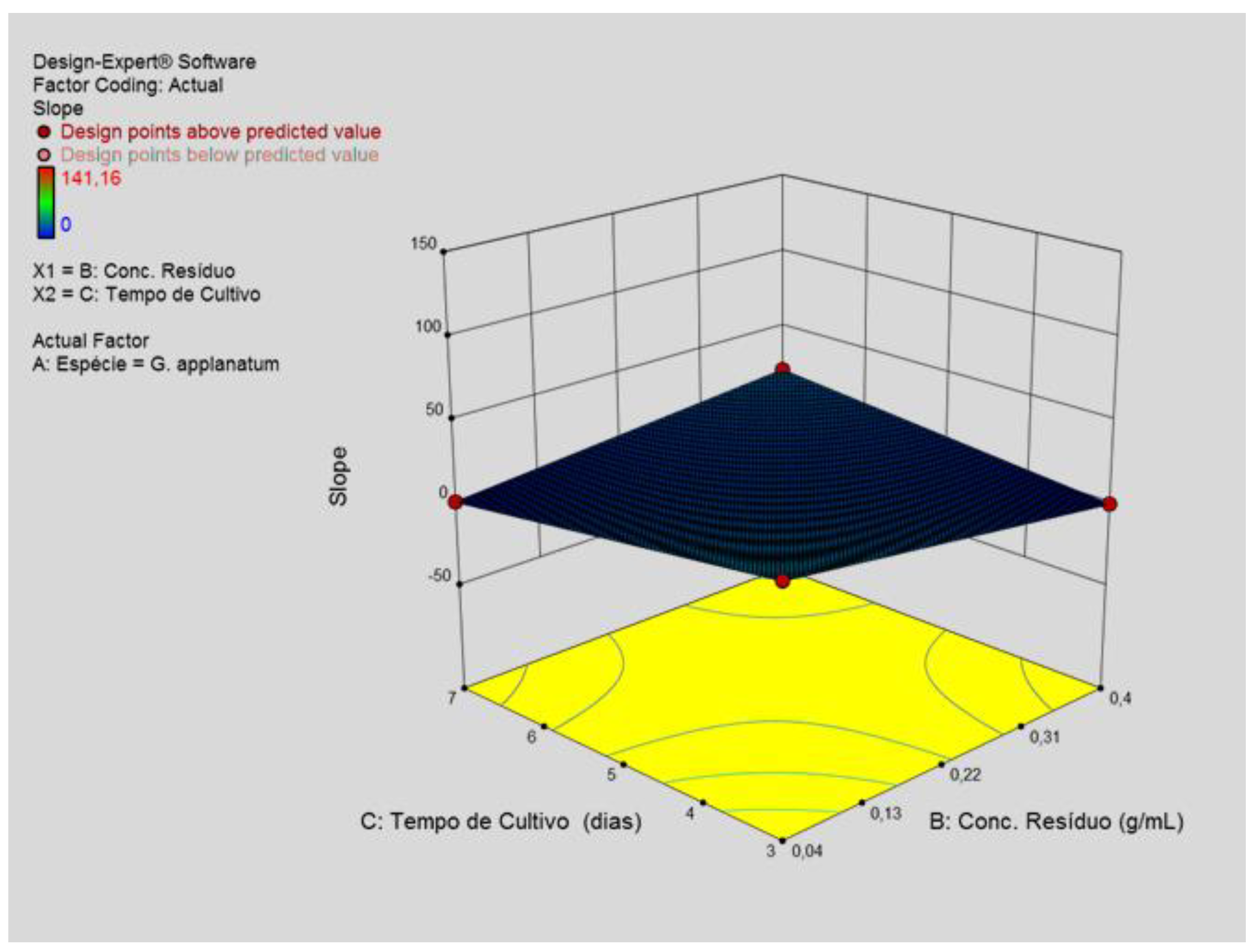

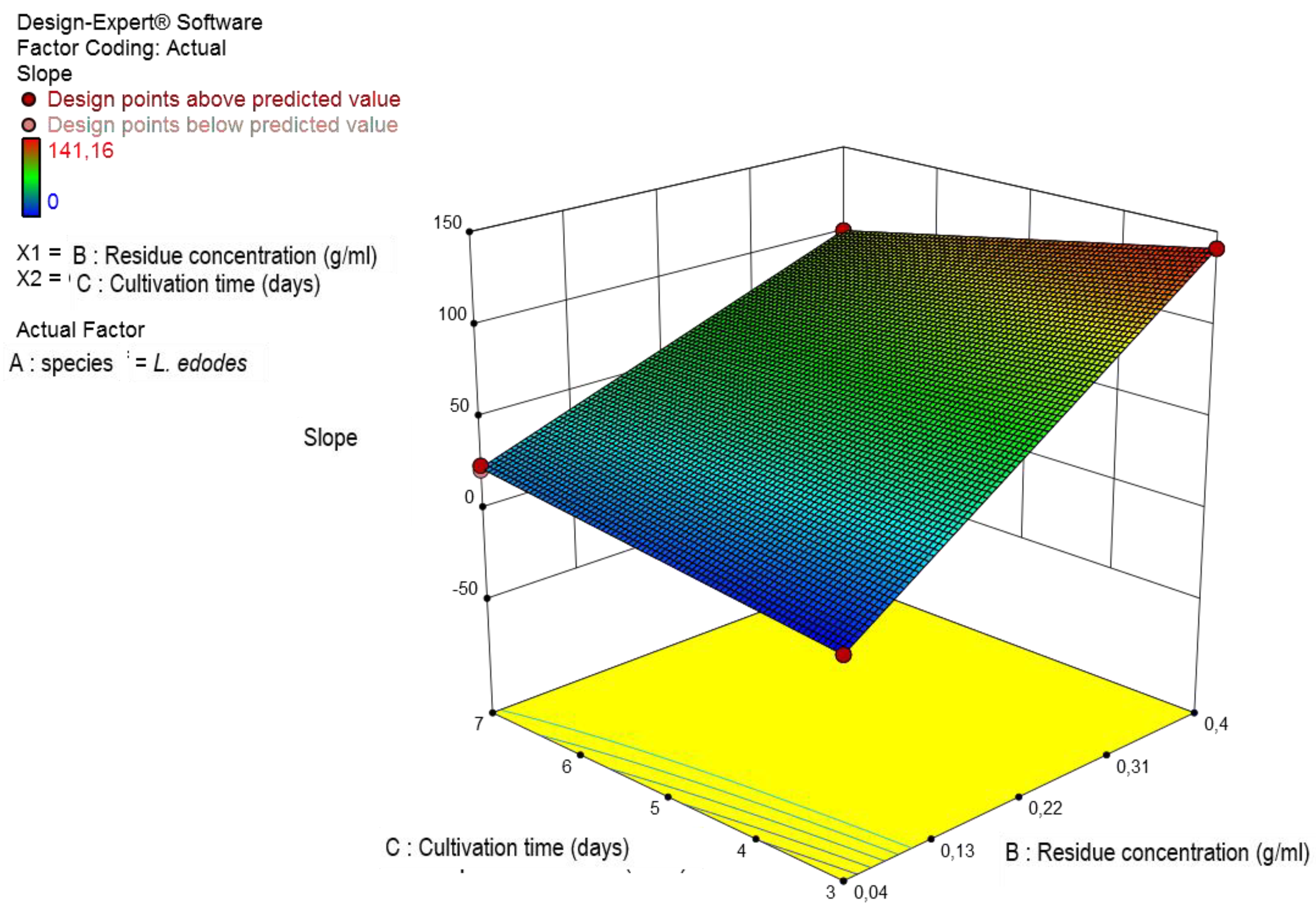

2.3.7. Experimental Design to Optimize Extracellular β-D-Glucan Production

2.3.8. Preparation of Stationary Phases for IMAC:

2.3.9. Chromatographic Behaviour of β-D-glucans from Mushroom Strains on Immobilized Metal Chelates (IMAC):

2.3.10. Purification of β-D-Glucan from Basidiomycete Mushroom Strains by IMAC

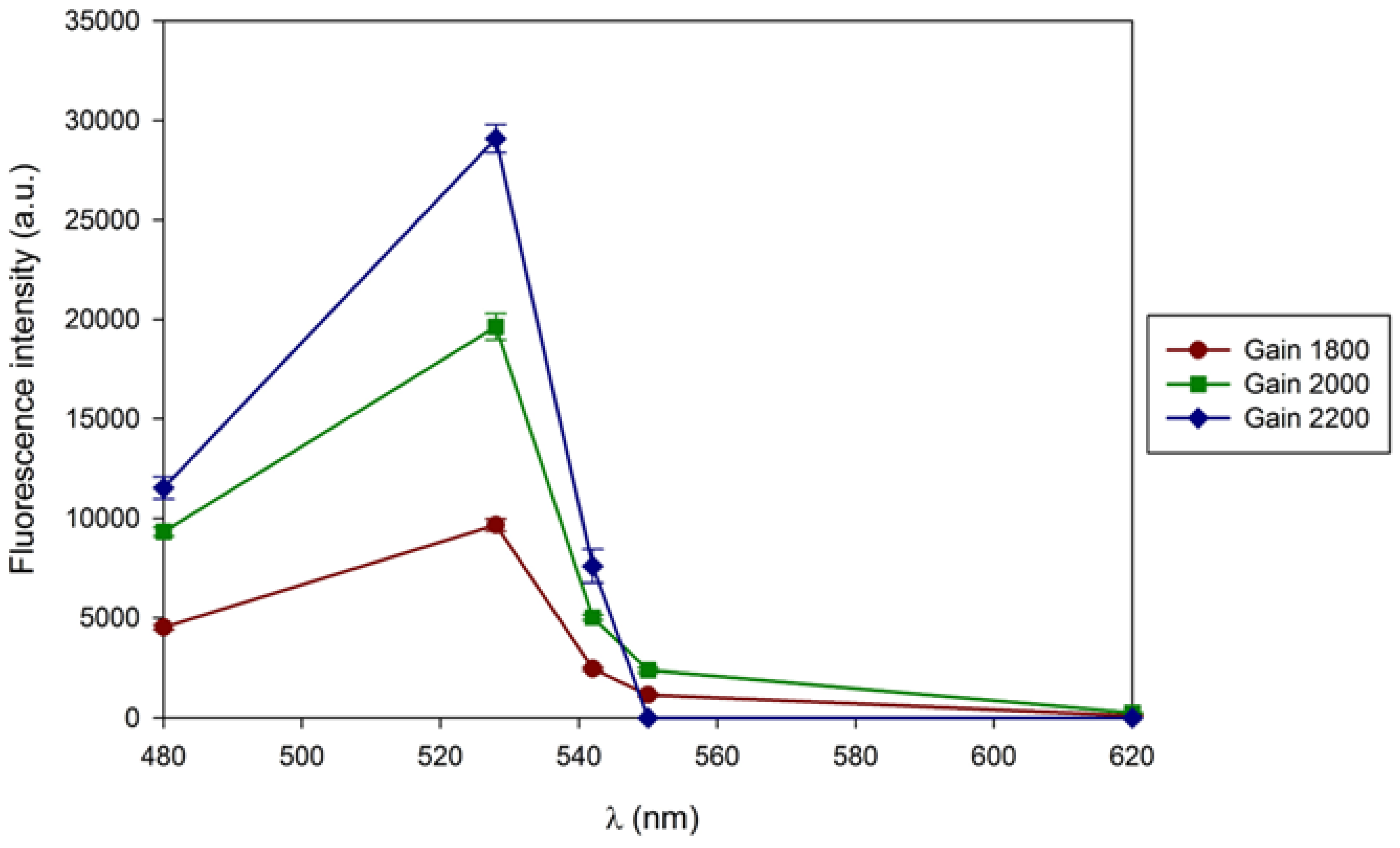

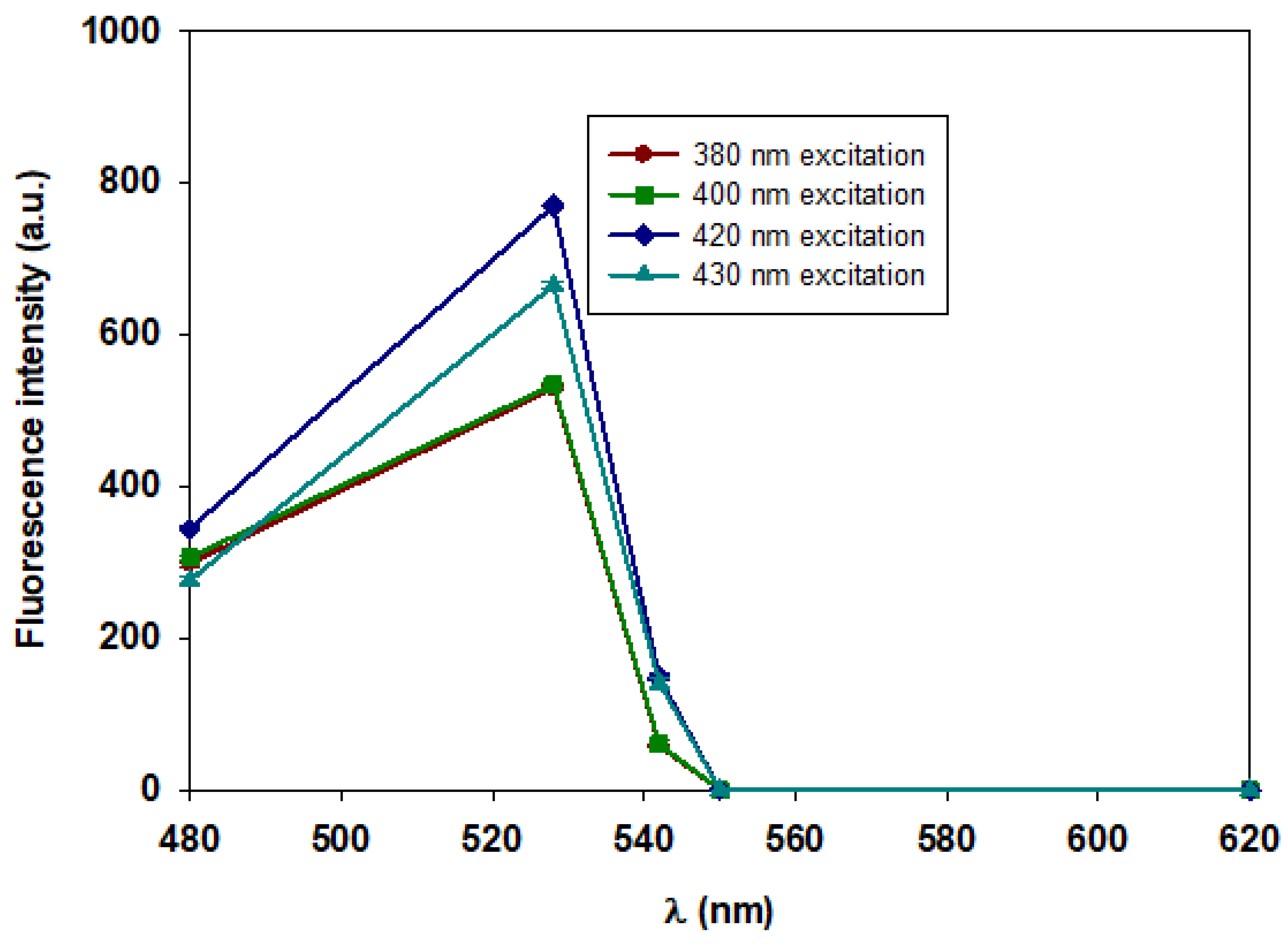

2.3.11. Intrinsic Fluorescence Measurements of β-D-Glucans

2.3.12. FTIR Analysis of β-D-Glucans

2.3.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

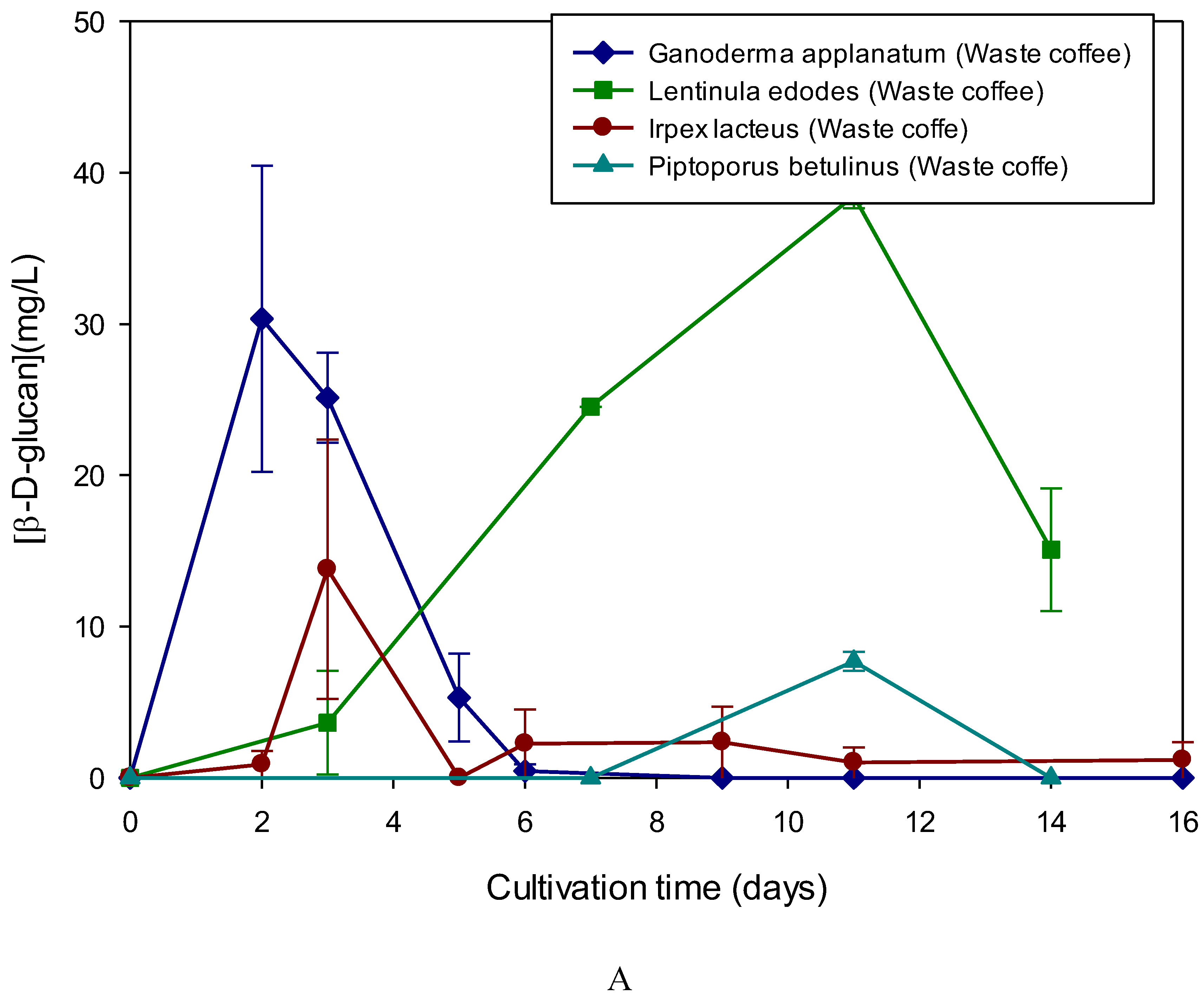

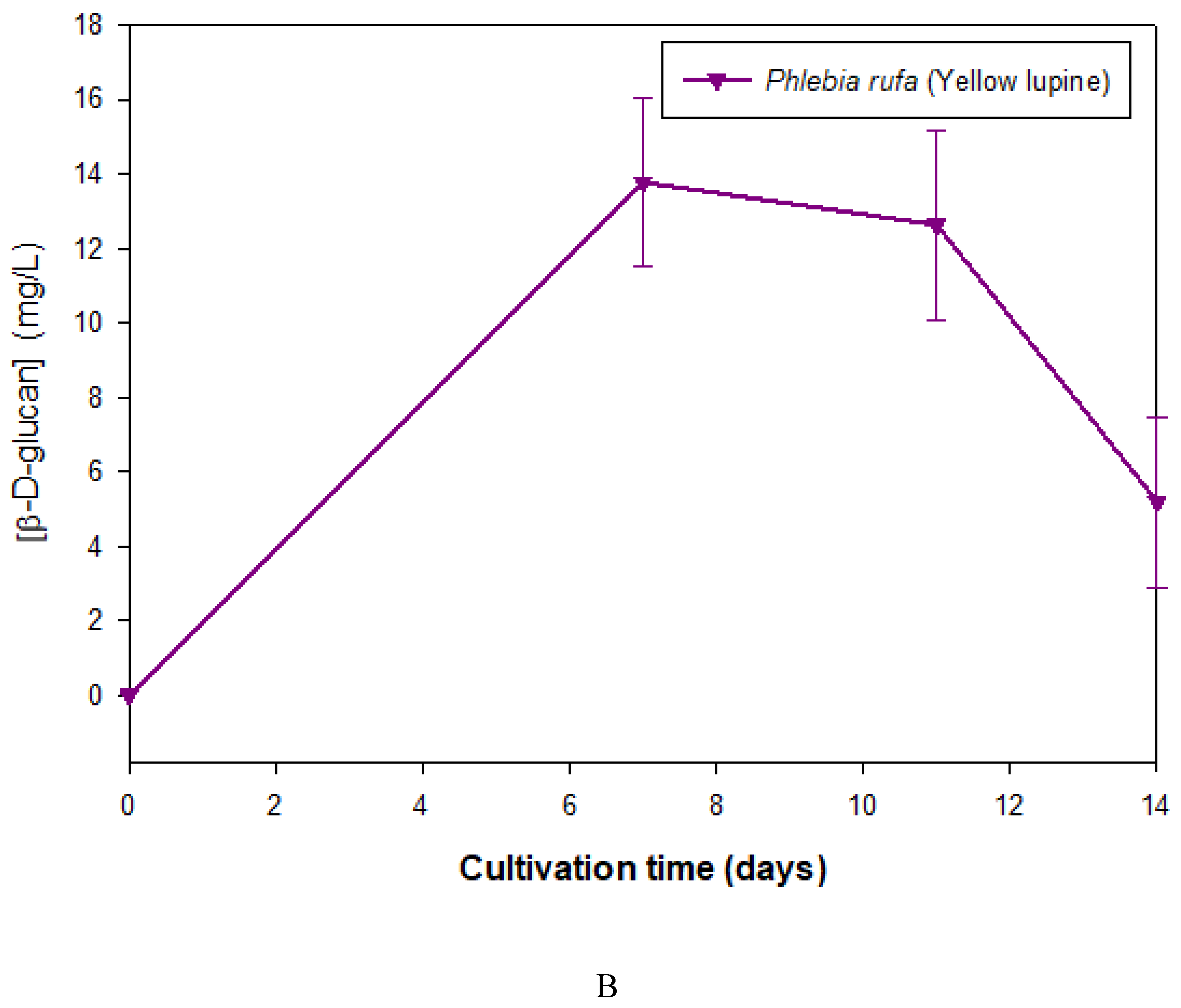

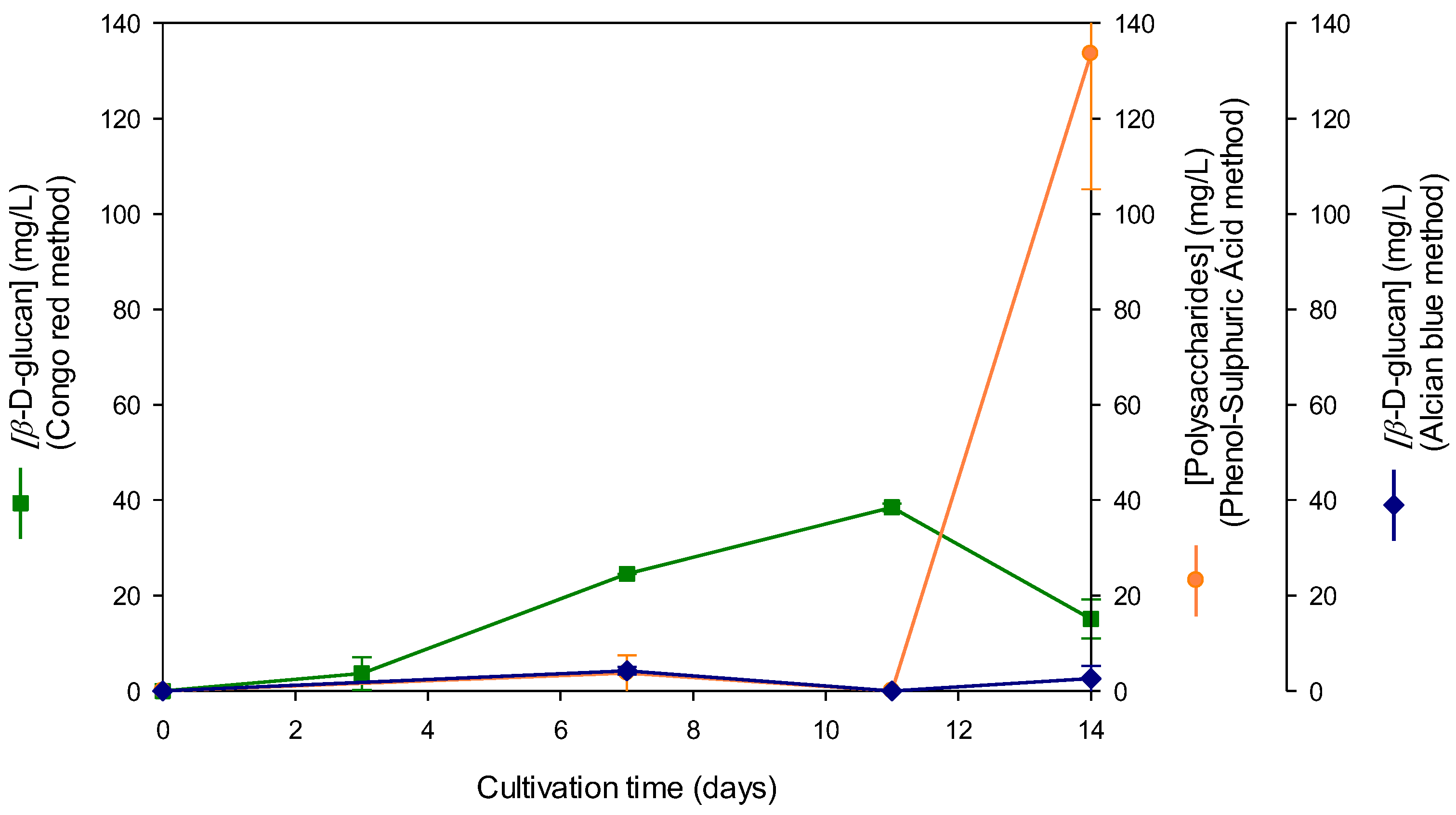

3.1. Optimization of Cultivation Conditions for β-D-Glucan Overproduction

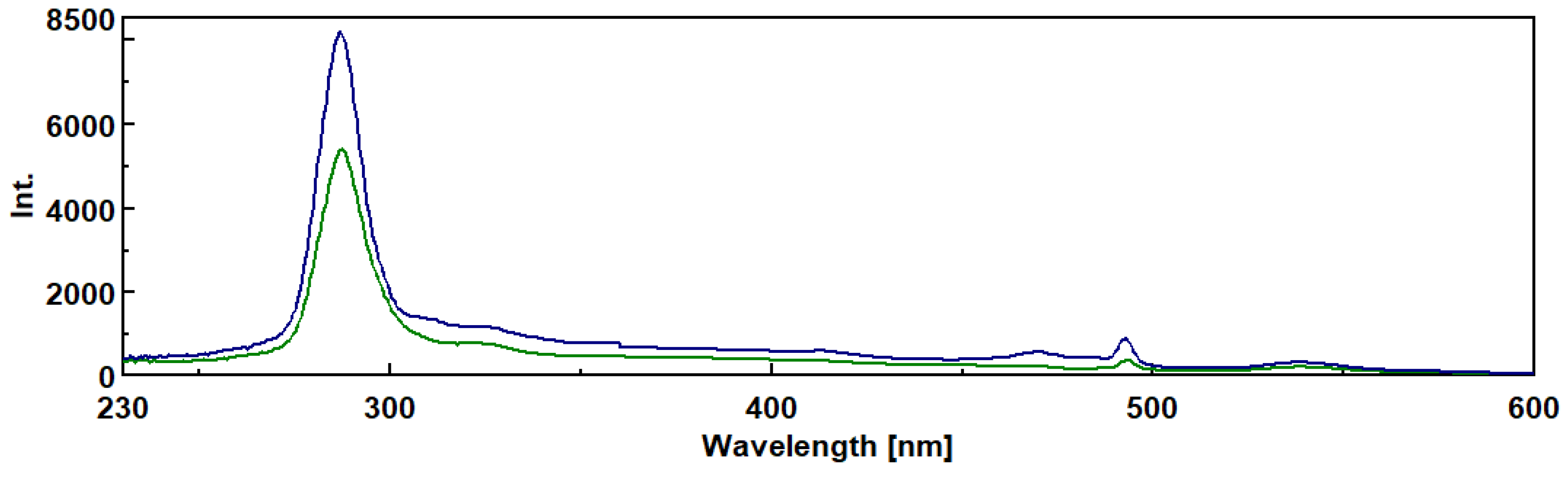

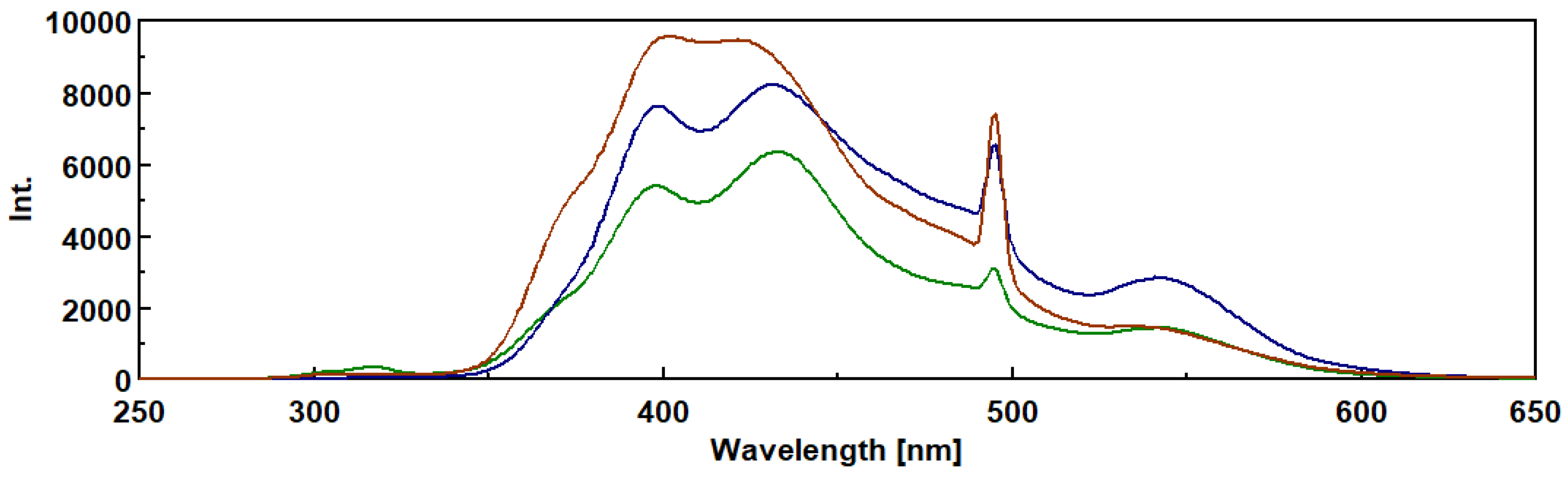

3.2. Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectroscopy

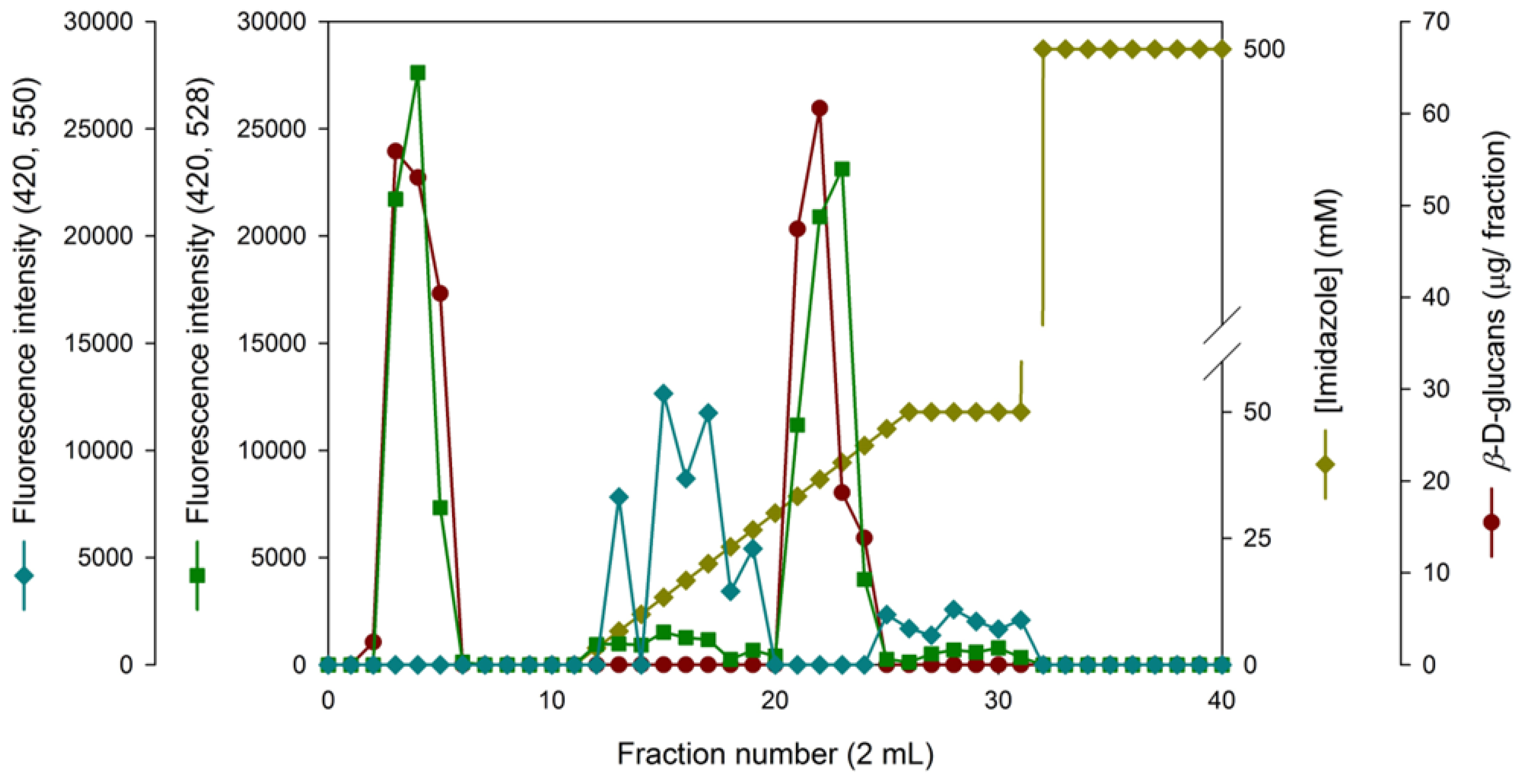

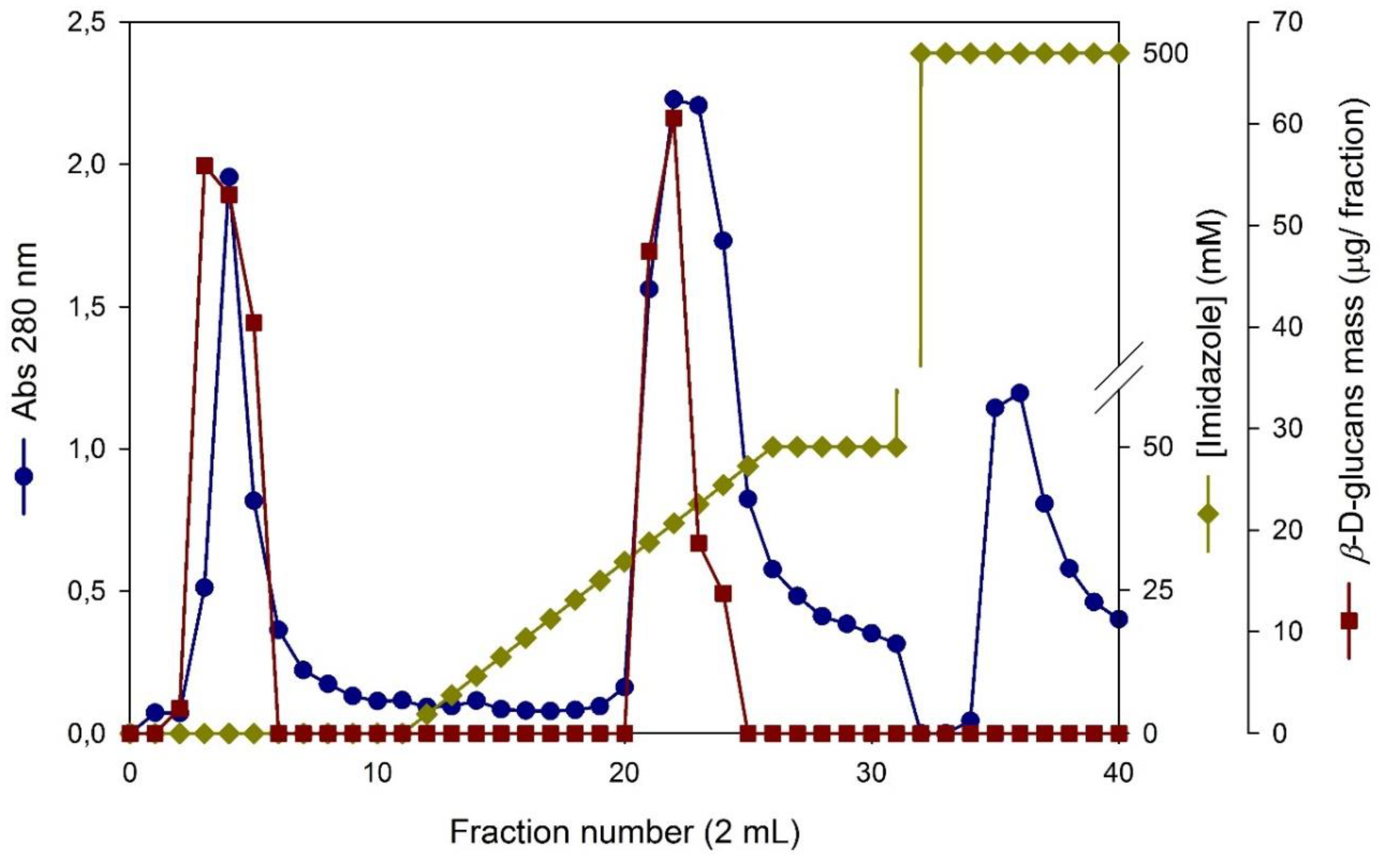

3.3. Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography

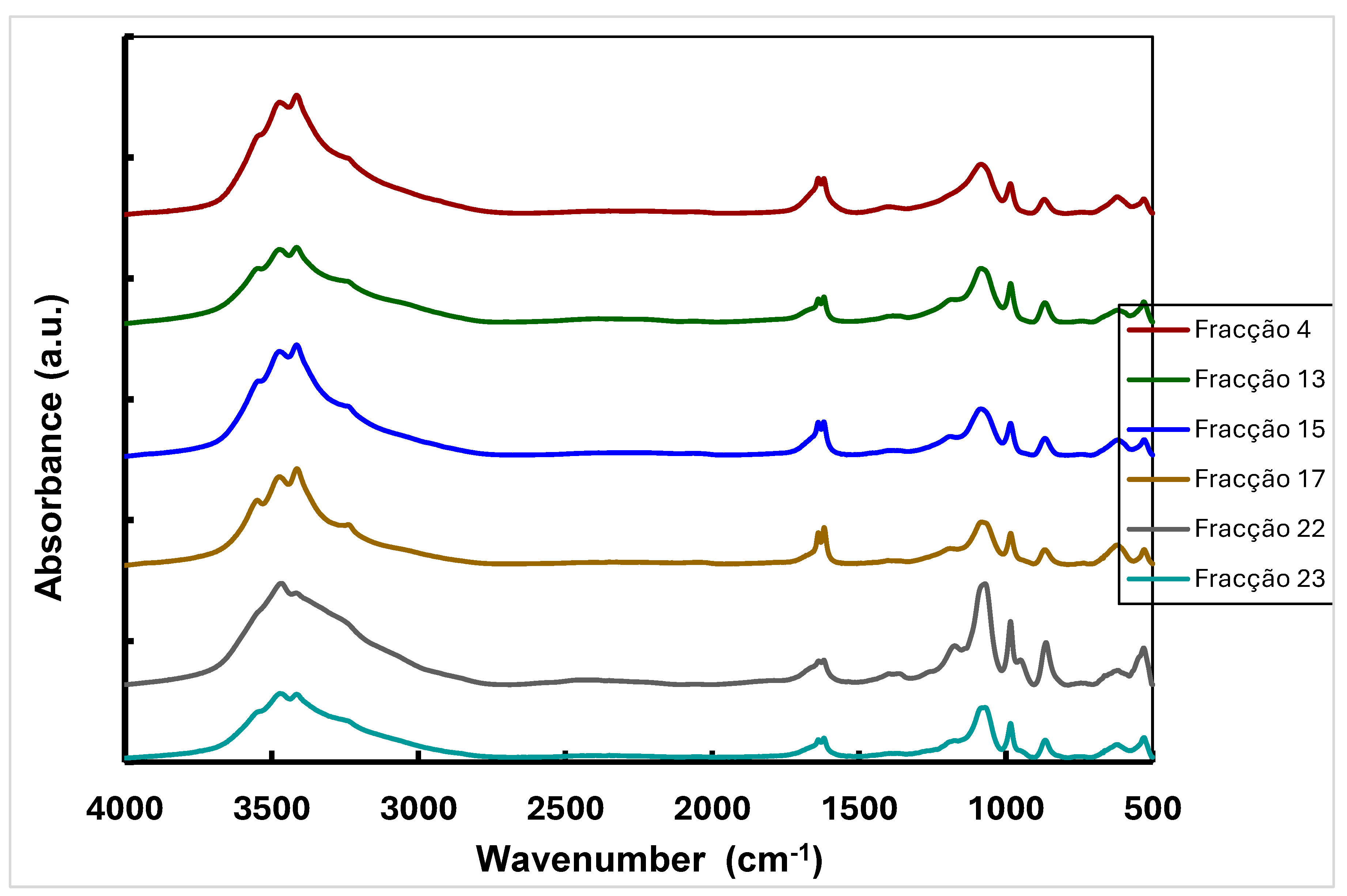

3.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

.

.

.

.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author’s contribution

Financial support

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| BDGE | 1,4-Butanediol diglycidyl ether |

| EPI | Epiclorohydrin |

| IDA | Iminodiacetic acid |

| IMAC | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography |

| NTA | Nitrilotriacetic acid |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

References

- Luna, K.A.; Aguilar, C.N.;Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Ruiz, H.A.;Martínez, J.L.; Chávez-González, M.L. Bioprocessing of Spent Coffee Grounds as a Sustainable Alternative for the Production of Bioactive Compounds. Fermentation 2025, 11,366. [CrossRef]

- Otieno, O.D., Mulaa, F.J., Obiero, G., Midiwo, J., Utilization of fruit waste substrates in mushroom production and manipulation of chemical composition. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 39, (2022), 102250 . [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.; Gumul, D. The Use of Waste Products from the Food Industry to Obtain High Value-Added Products. Foods 2024, 13, 847. [CrossRef]

- Khatam , K., Qazanfarzadeh, Z.,Jim’enez-Quero, A., Fungal fermentation: The blueprint for transforming industrial side streams and residues. Bioresource Technology 440 (2026) 133426 . [CrossRef]

- (5) Lysakova, V.; Streletskiy,A.; Sineva, O.; Isakova, E.;Krasnopolskaya, L. Screening of Basidiomycete Strains Capable of Synthesizing Antibacterial and Antifungal Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9802. [CrossRef]

- Bhambri A, Srivastava M, Mahale VG, Mahale S and Karn SK (2022) Mushrooms as Potential Sources of Active Metabolites and Medicines. Front. Microbiol. 13:837266. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Zábó, V.; Varga, J.T.; Bálint, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípo˝, T.; Rza˛sa-Duran, E.; Varga, P. Functional Foods in Modern Nutrition Science: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2153. [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A., Joshi, P. B., Ahmad, Z.,Hemeg, H. A., Olatunde, A., Naz, S., Hafeez, N., &Simal-Gandara, J. (2023). Edible mushrooms as potential functional foods in amelioration of hypertension. PhytotherapyResearch, 37(6), 2644–2660. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, M.; Chinou, I.; Gortzi, O. A Systematic Review of the Seven Most Cultivated Mushrooms: Production Processes, Nutritional Value, Bioactive Properties and Impact on Non-Communicable Diseases. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1329. [CrossRef]

- Case S, O’Brien T, Ledwith AE, Chen S, Horneck Johnston CJH, Hackett EE, O’Sullivan M, Charles-Messance H, Dempsey E, Yadav S, Wilson J, Corr SC, Nagar S and Sheedy FJ (2024) b-glucans from Agaricus bisporus mushroom products drive Trained Immunity. Front. Nutr. 11:1346706. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Dutta, S.D.; Ganguly, K.; Cho, S.-J.; Lim, K.-T. Mushroom-Derived Bioactive Molecules as Immunotherapeutic Agents: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 1359. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y-L., Li, W.Q., Wu X-Q., Cheng, J-W., Ma S-Y., Statistical optimization of media for mycelial growth and exo-polysaccharide production by Lentinus edodes and a kinetic model study of two growth morphologies Biochemical Engineering Journal, 49, 2010,104-112 . [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Gupta, O.P.; Sagwal, V.; Kumar, A.; Patwa, N.; Mohan, N.; Ankush; Kumar, D.; Vir, O.; Singh, J.; et al. Beta-Glucan as a Soluble Dietary Fiber Source: Origins, Biosynthesis, Extraction, Purification, Structural Characteristics, Bioavailability, Biofunctional Attributes, Industrial Utilization, and Global Trade. Nutrients 2024, 16, 900. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bassart, Z., Fabra, M.J., Martínez-Abad, A., López-Rubio, A., Compositional differences of β-glucan-rich extracts from three relevant mushrooms obtained through a sequential extraction protocol Food Chemistry 402, 2023, 134207.

- Han B, Baruah K, Cox E, Vanrompay D and Bossier P (2020) Structure-Functional Activity Relationship of b-Glucans From the Perspective of Immunomodulation: A Mini-Review. Front. Immunol. 11:658. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tan. J.; Nima, L.; Sang. Y.; Cai. X.; Xue, H.; Polysaccharides from fungi: A review on their extraction, purification, structural features, and biological activities Food Chemistry: X 15 (2022) 100414.

- Flores, G.A.,Cusumano, G., Venanzoni, R., Angelini, P.The Glucans Mushrooms: Molecules of Significant Biological and Medicinal Value. Polysaccharides 2024, 5(3), 212- 224; [CrossRef]

- Martins, S., Karmali, A., Serralheiro, M.L. Chromatographic behaviour of monoclonal antibodies against wild-type amidase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on immobilized metal chelates. Biomedical Chromatography 2011 . [CrossRef]

- Theint, P.P., Sakkayawong, N. Buajarern, S. Singkhonrat, J. (2025) Development of an analytical fluorescence method for quantifying β-glucan content from mushroom extracts; utilizing curcumin as a green chemical fluorophore Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 137, Part A . [CrossRef]

- Koenig, S., Rühmann, B., Sieber, V., Schmid, J. (2017) Quantitative assay of β-(1,3)–β-(1,6)–glucans from fermentation broth using aniline blue Carbohydrate Polymers, 174, 2017, 57-64 . [CrossRef]

- Semedo, M.C., A. Karmali, and L. Fonseca (2015) A high throughput colorimetric assay of β-1,3-D-glucans by Congo red dye. J. Microbiol. Meth. 109: 140–148.

- Masuko, T., A. Minami, N. Iwasaki, T. Majima, S.-I. Nishimura, and Y.C. Lee (2005) Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol–sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 339: 69–72.

- Bradford, M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72: 248–254.

- Semedo, M.C., A. Karmali, and L. Fonseca (2015) A novel colorimetric assay of β-D-glucans in basidiomycete strains by alcian blue dye in a 96-well microtiter plate. Biotechnol. Prog. 31: 1526-1535.

- Freixo, MR., Karmali, A., Frazão, C., Arteiro, J.M. Production of laccase and xylanase from Coriolus versicolor grown on tomato pomace and their chromatographic behaviour on immobilized metal chelates. Process Biochemistry, 43, 2008, 1265-1274.

- Martins, S., Karmali, A., Andrade, J., Serralheiro, M. (2006), “Immobilized metal affinity chromatography of monoclonal immunoglobulin M against mutant amidase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa”, Molecular Biotechnology, 33, 103-113.

- Gaberc-Porekar, V., Menart, V. (2001), “Perspectives of immobilized-metal affinity chromatography”, Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods, 49, 335-360.

- Block, H. Maertens, B., Spriestersbach, A., Brinker, N., Kubicek, J.,Fabis, R., Labahn, J., Schäfer, F. Methods in Enzymology, Volume 463, 2009 Chapter 27 Immobilized-Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC): A Review ,439-473.

- Kozarski, M., Klaus, A., Nikšić, M., Vrvić, M., Todorović, N., Jakovljević, D., Griensven, L. (2012), “Antioxidative activities and chemical characterization of polysaccharide extracts from the widely used mushrooms Ganoderma applanatum, Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinus edodes and Trametes versicolor”, Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 26, 144-153.

| Cultivation Time (days) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agro-Industrial wastes | Oatmeal | Yellow lupine | Waste coffee ground | Banana peel | Pear peel | Pineapple peel | Mango peel | |

| Basidiomycete strains | ||||||||

| F. fomentarius | 11 | 11 | 11 | +60 | 11 | 28 | 28 | |

| G. applanatum | +60 | 56 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| G. carnosum | 37 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 14 | |

| G. lucidum violeta | 37 | 16 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| I. lacteus | 5 | 5 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 13 | |

| L. edodes | 18 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 11 | 14 | 11 | |

| P. rufa | 37 | 30 | 15 | 30 | 15 | 14 | 30 | |

| P. betulinus | 50 | 18 | 18 | 18 | +60 | 45 | 45 | |

| P. ostreatus | 37 | 31 | 23 | 18 | 18 | 28 | 28 | |

| Basidiomycete strains | Agro-Industrial Residue | β-Glucan Concentration (mg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media Filtrate | Cold Water Fraction | Hot Water Fraction | KOH Fraction | HCl Fraction |

||

| G. applanatum | Banana Peel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Waste Coffee Ground | 2,96x101± 5,79x10-1 | 0 | 8,04x10-1± 2,57x10-1 | 1,38± 2,82x10-1 | 3,16± 5,19x10-1 | |

| G. carnosum | Banana Peel | 0 | 0 | 1,83x10-1± 1.24x10-2 | 4,16± 1,69x10-1 | 9,76± 1,88 |

| Waste Coffee Ground | 4,26± 1,91 | 0 | 1,57± 1,31x10-2 | 1,03x101± 8,64 | 1,83x101± 1,27 | |

| L. edodes | Banana Peel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,46± 4,02x10-2 | 7,56± 5,19x10-1 |

| Waste Coffee Ground | 3,85x101± 4,41 | 0 | 9,14x10-1± 2,99x10-3 | 1,48x101± 2,97 | 1,56± 1,96x10-1 | |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | P-Value, Prob>F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3,87x104 | 7 | 5,53x103 | 1,34x104 | <0,0001 |

| A- Species | 1,13x104 | 1 | 1,13x104 | 2,74x104 | <0,0001 |

| B- Residue Concentration | 1,10x104 | 1 | 1,10x104 | 2,66x104 | <0,0001 |

| C- Time of Cultivation | 1,41x102 | 1 | 1,41x102 | 3,41x102 | <0,0001 |

| AB | 1,30x104 | 1 | 1,30x104 | 3,16x104 | <0,0001 |

| AC | 2,56x101 | 1 | 2,56x101 | 6,21x101 | <0,0001 |

| BC | 4,40x101 | 1 | 4,40x101 | 1,07x102 | <0,0001 |

| ABC | 3,23x103 | 1 | 3,23x103 | 7,83x103 | <0,0001 |

| Residual | 3,30 | 8 | 4,10x10-1 | ||

| Corrected Total | 3,87x104 | 15 |

| Stationary phase | pH | Cu(II)-IDA | Ni(II)-IDA | Co(II)-IDA | Zn(II)-IDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepharose 6B- BDGE (S1) | 8 | ± | - | - | ± |

| Sepharose 6B- EPI (S2) | 8 | - | - | - | ± |

| Sepharose 4B- BDGE (S3) | 8 | ±/- | - | - | ± |

| Sepharose 4B- EPI (S4) | 8 | + | ± | - | ± |

| Stationary phase | pH | Cu(II)-NTA | Ni(II)-NTA | Zn(II)-NTA | Co(II)-NTA |

| Sepharose 6B- BDGE (S5) | 8 | - | - | - | - |

| Sepharose 6B- EPI (S6) | 8 | ± | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).