1. Introduction

Bioeconomy uses renewable biological resources to produce basic building blocks for materials, chemicals and energy [

1]. Bioeconomy may play a key role in the use of renewable raw materials for production of added value substances in several fields of industrial biotechnology such as food, feed, paper and pulp and biofuels production [

2]. Food processing industries and agriculture generate annually huge volumes of wastes that are both a disposal and an environmental problem. These wastes contain a large diversity of functional chemical substances which could be valorised into higher value products [

3,

4,

5]. Basidiomycete mushroom strains have been known since ancient times to grow on agro-industrial wastes producing high value products such as enzymes, beta-glucans, lectins, vitamins, lipids and several secondary metabolites [

6,

7]. Among these biomolecules,

β-glucans play a major role as biological response modifiers (BRM) in several clinical disorders such as cardiovascular, HIV, diabetes, cancer, neurological and immunological disorders [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Basidiomycete mushroom strains produce a heterogeneous mixture of several

β-glucans of different sizes, structures and either bound to proteins or in free forms [

13]. The purification of such

β-glucan in homogeneous preparations is of crucial interest to investigate their structure-function relationship [

14,

15]. Therefore, it is of great interest to use specific assay methods for monitorization of

β-glucan production in submerged fermentation from basidiomycete strains. Furthermore, purification procedures for such

β-glucans require the use of specific assay methods to monitor their levels in chromatographic techniques.

Some colorimetric and fluorimetric assay methods have been published in the literature for assay of

β-D-glucans by using phenol-sulphuric acid, Congo red, alcian blue as well as aniline blue, respectively [

16,

17,

18,

19]. As far as ELISA assay methods are concerned, there are few publications on

β-D-glucan assay [

20,

21,

22].

The present work involves the use of monoclonal antibodies of IgG and IgM class to monitor the production of β-glucans from basidiomycete strains by using several agro-industrial wastes. These β-glucans will be extracted and purified by ion-exchange and gel filtration chromatography and they will be characterized by immunochemical techniques and FTIR analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Polystyrene miocroplates 96-well MicroWell™ PolySorp® flat bottom plates were from Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™ (Nunc 475094). Sephacryl S-300HR and DEAE-cellulose anion exchange media DE-52 GE Whatman® were supplied by GE (Healthcare Bio-Science Corp., United Kingdom). Nitrocellulose transfer membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (USA). BioWhittaker™ RPMI 1640 (with 25 mM HEPES, L-Glutamine, 100 units/mL Penicillin and 50 µg/mL Streptomycin) was obtained from Lonza Ltd. (Visp, Switzerland) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from GIBCO®- Life Technologies Corp. (USA).

Potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium was supplied by HiMedia Laboratories (Mumbai, India). Milk permeate, orange and apple peels, pine sawdust, yellow lupine, rice husk, apple pomace, yellow lupin and waste coffee grounds were homemade. All disposable plastic ware were obtained from Orange Scientific (Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium) and all other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Mushroom Samples

Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma carnosum were isolated from old growth forests of the Olympic Peninsula in Port Townsend - WA (USA). Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom stems were a kind gift of a mushroom grower in Amsterdam (Netherlands).

Agaricus blazei, Inonotus obliquus, Polyporus umbellatus, Poria cocos, Ganoderma lucidum, Hericium erinaceus, Coriolus versicolor and Lentinula edodes young fruiting body powders were obtained from Mycology Research Laboratory, Ltd. (United Kingdom).

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Maintenance and Growth Conditions of Mushroom Strains

The strains of P. ostreatus and G. carnosum were maintained at 4ºC on PDA.

2.3.2. Production of Extracellular β-Glucans from Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma carnosum in Culture Media Containing Agro-Industrial Wastes

P. ostreatus and G. carnosum were grown in media containing 1 g/L KH2PO4, 1 g/L MgSO4, 1g/L (NH4)2SO4 and 4 g/L either rice husk, 40 g/L orange peels or waste coffee grounds. Actively growing mycelia of P. ostreatus or G. carnosum were transferred to the seed culture medium by punching out 5 mm of PDA with a sterilized cutter. The seed culture was grown in a 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 mL medium and incubated at 28 ºC on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm for 14 days. The fermentation process was monitored by using Mabs 3F8_3H7 and 1E6_1E8_B5 by indirect ELISA to detect the β-glucan in fermentation broth as well as protein and total polysaccharide levels at 0, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11 and 14 days of fermentation.

2.3.3. Production and Isolation of Extracellular β-Glucans from Pleurotus ostreatus

P. ostreatus was grown for 14 days by submerged fermentation in media supplemented with 50 % (v/v) milk whey, 2 % (w/v) glucose, 0.6 % (w/v) yeast extract, 0.2 % (w/v) (NH

4)

2SO

4, 0.2 % (w/v) KH

2PO

4, 0.05 % (w/v) MgSO

4.7H

2O and 0.05 % (w/v) KCl at initial pH 5.5. The cultivation conditions were 28 ºC and 150 rpm on an orbital shaker, as described previously Mycelia biomass was separated from culture broth by vacuum filtration and extracellular

β-glucans (EBG) were precipitated with 95 % (v/v) ethanol from the culture filtrate. Precipitated polysaccharides were dissolved in 15 mM phosphate buffered saline pH 7.2 (PBS) [

23].

2.3.4. Production of Intracellular β-Glucans from Ganoderma carnosum

G. carnosum was grown in media containing 1 g/L KH2PO4, 40 g /L orange peels, 2 g/L MgSO4 pH 5.8, 200 rpm at 25 ºC for 10 days by submerged fermentation.

2.3.5. Isolation of Intracellular β-D-Glucans

Mycelial biomass from the fermentation broth of

P. ostreatus and

G. carnosum was separated by suction in a Büchner funnel [

23].

The isolation of intracellular

β-D-glucans (IBG) from mycelial biomass pellet from

P. ostreatus and

G. carnosum and from young fruiting bodies powder from

A. blazei,

I. obliquus,

P. umbellatus,

P. cocos,

G. lucidum, H. erinaceus, C. versicolor and

L. edodes was performed by multistep water extraction followed by extraction with alkali and acidic solutions as described previously [

17]. Several fractions for each mushroom strain were obtained called FW1, FW2, FKOH, FNaOH and FHCl, according to the solvent used.

These extraction steps were also carried out for EBG from P. ostreatus which was obtained by precipitation with 95 % (v/v) ethanol.

2.3.6. Total Polysaccharides and Protein Assays

Total polysaccharides in several samples were quantified by the phenol–sulfuric acid method, using polygalacturonic acid as the standard [

16] while protein quantification was performed by Coomassie blue dye-binding method with BSA as standard [

24].

2.3.7. Congo Red Assay for Specific Determination of β-D-Glucans with Triple Helical Structure

Congo red dye colorimetric assay was carried out to quantify the concentration of

β-glucans in several samples as described previously, using

β-D-glucan from barley as standard [

17].

2.3.8. Mabs Against EBG from P. ostreatus

The hybridoma cell line 3F8_3H7 secreting Mabs of IgM class and the hybridoma cell line 1E6_1E8_B5 secreting Mabs of IgG class against EBG from

P. ostreatus were produced previously [

21,

22]. The Mabs were produced from 3F8_3H7 and 1E6_1E8_B5 clones in culture in vitro (RPMI 1640 + 10% (v/v) FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO

2.

2.3.9. Indirect Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA)

In order to detect β-glucans in isolated fractions from the mushroom strains and in fermentation broths, indirect ELISA was performed by using Mabs 3F8_3H7 and 1E6_1E8_B5. PolySorp

® microplate wells were incubated overnight at 4ºC with

β-glucans from several mushroom strains as the antigen (50μg/well). Either rabbit anti-mouse IgM-alkaline phosphatase conjugate or rabbit anti-mouse IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was used as the second antibody and

p-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate [

25]. One antibody unit is defined as the amount of Mab required to give a change in absorbance of 1.0 per 30 min at 415 nm due to the action of rabbit anti-mouse IgM-alkaline phosphatase conjugate on

p-nitrophenyl phosphate under the standard conditions of ELISA. All screenings assays were carried out in triplicate.

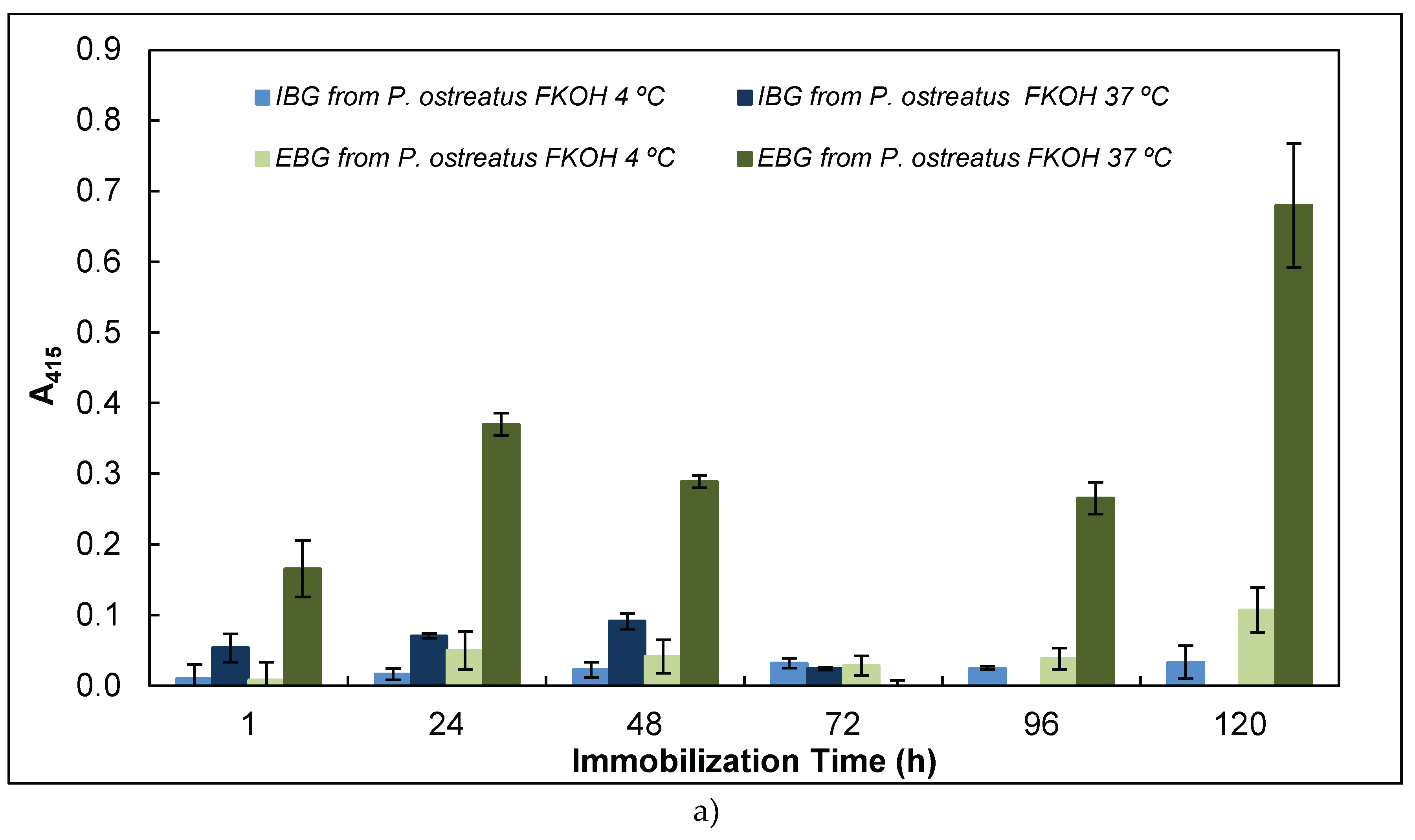

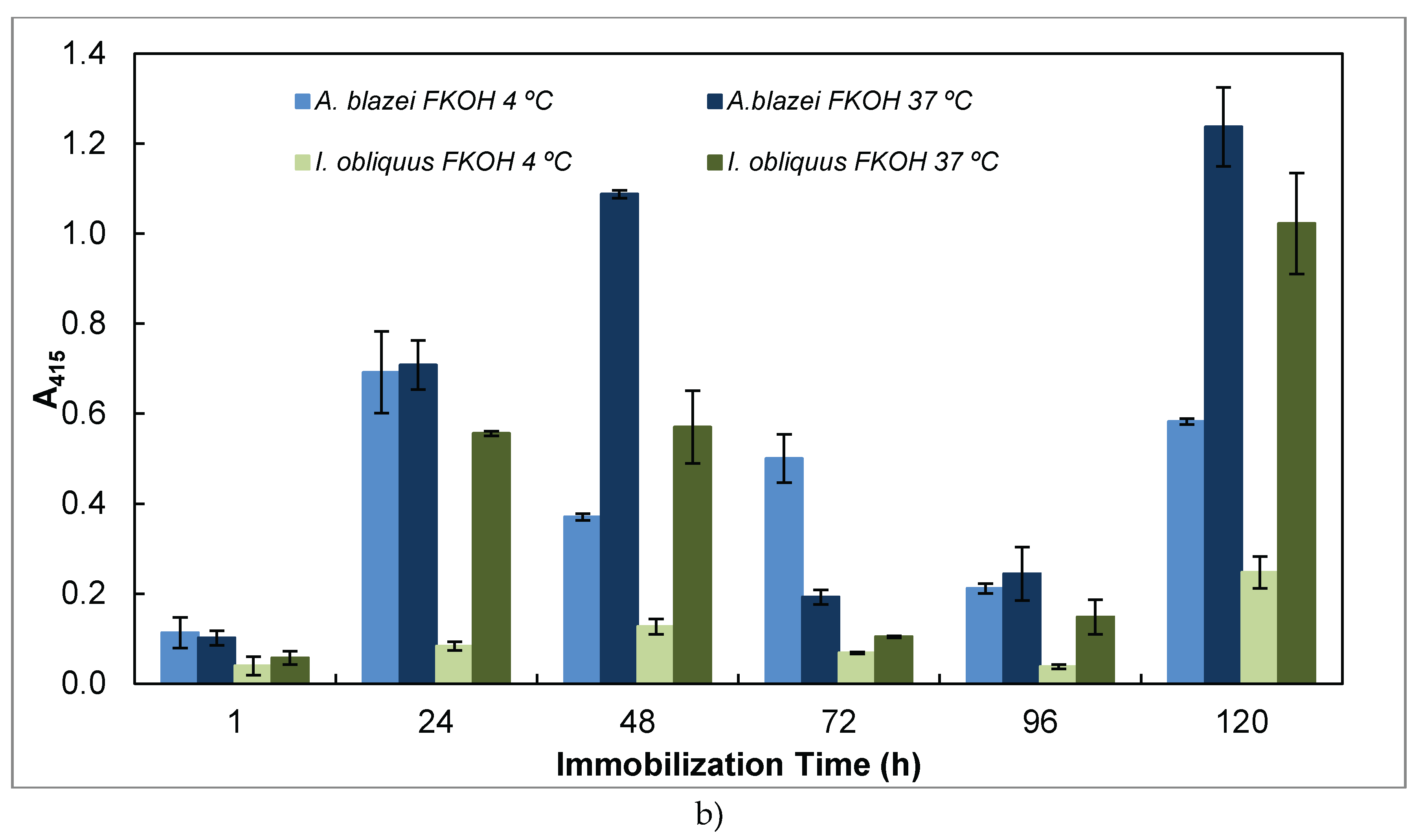

2.3.10. Study of the Effects of Temperature and Time on Adsorption of β- Glucans in PolySorp® 96-Well Plates

The effect of temperature (4 and 37ºC) and time (1, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h) of antigen immobilization on flat-bottom PolySorp® 96-well plates was investigated by measurements of A415. The following samples were used as antigens: EBG P. ostreatus and extraction fractions (FW1, FW2, FKOH, FHCl and FNaOH) from P. ostreatus, G. carnosum, G. lucidum, H. erinaceus, C. versicolor, L. edodes, I. obliquus, A. auricula, G. frondosa, P. umbellatus, C. sinensis, P. cocos and A. blazei . The indirect ELISA method was performed as described above.

2.3.11. Purification of EBG by Gel Filtration Chromatography

Extracellular β-glucans from P. osreatus were purified by gel filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-300 HR column (1 cm × 100 cm) eluted with PBS at a flow rate of 40 mL h−1. Column fractions were analysed for total polysaccharide at A200, protein and monitored by using 3F8_3H7 and 1E6_1E8_B5 Mabs in indirect ELISA.

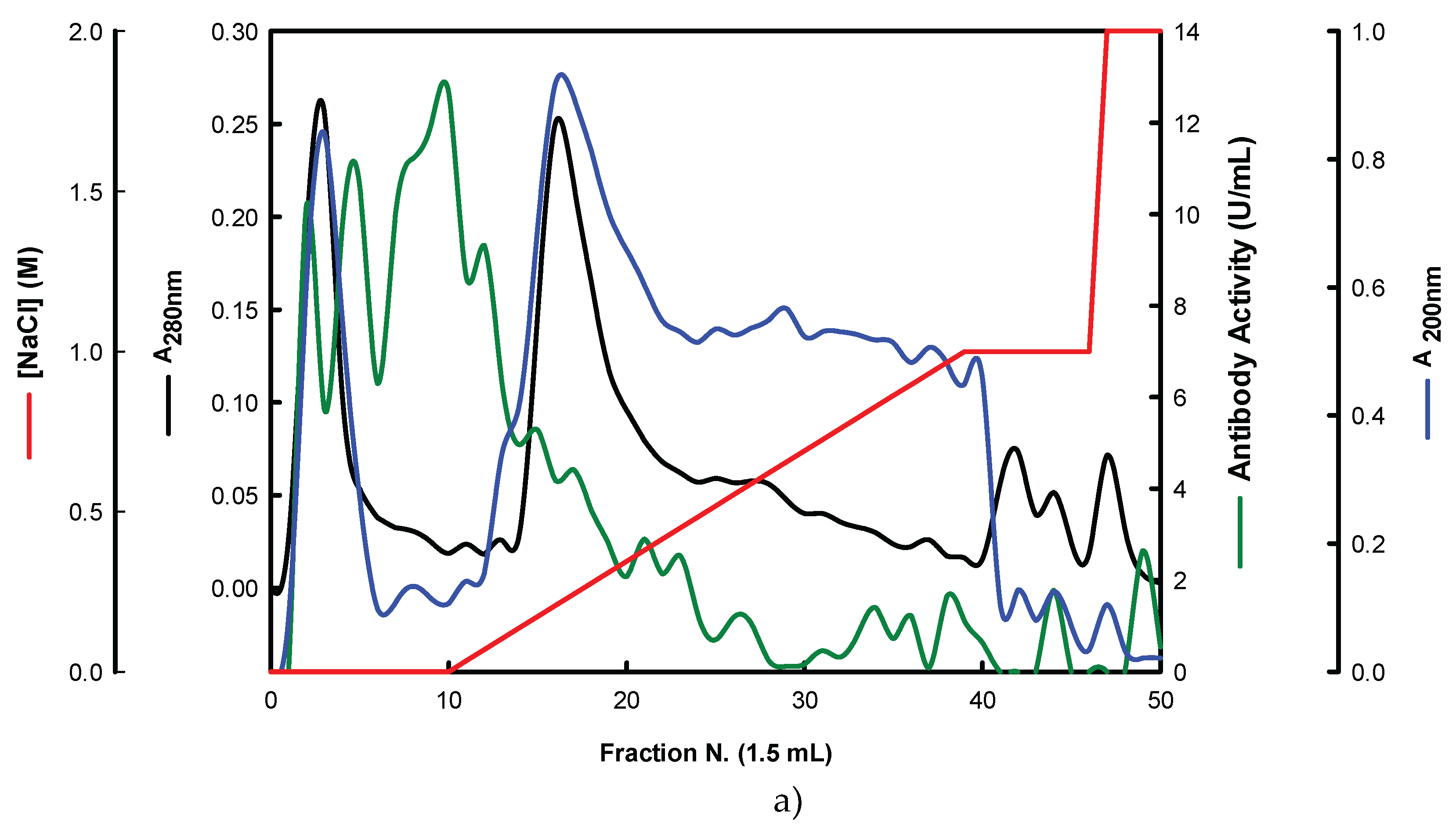

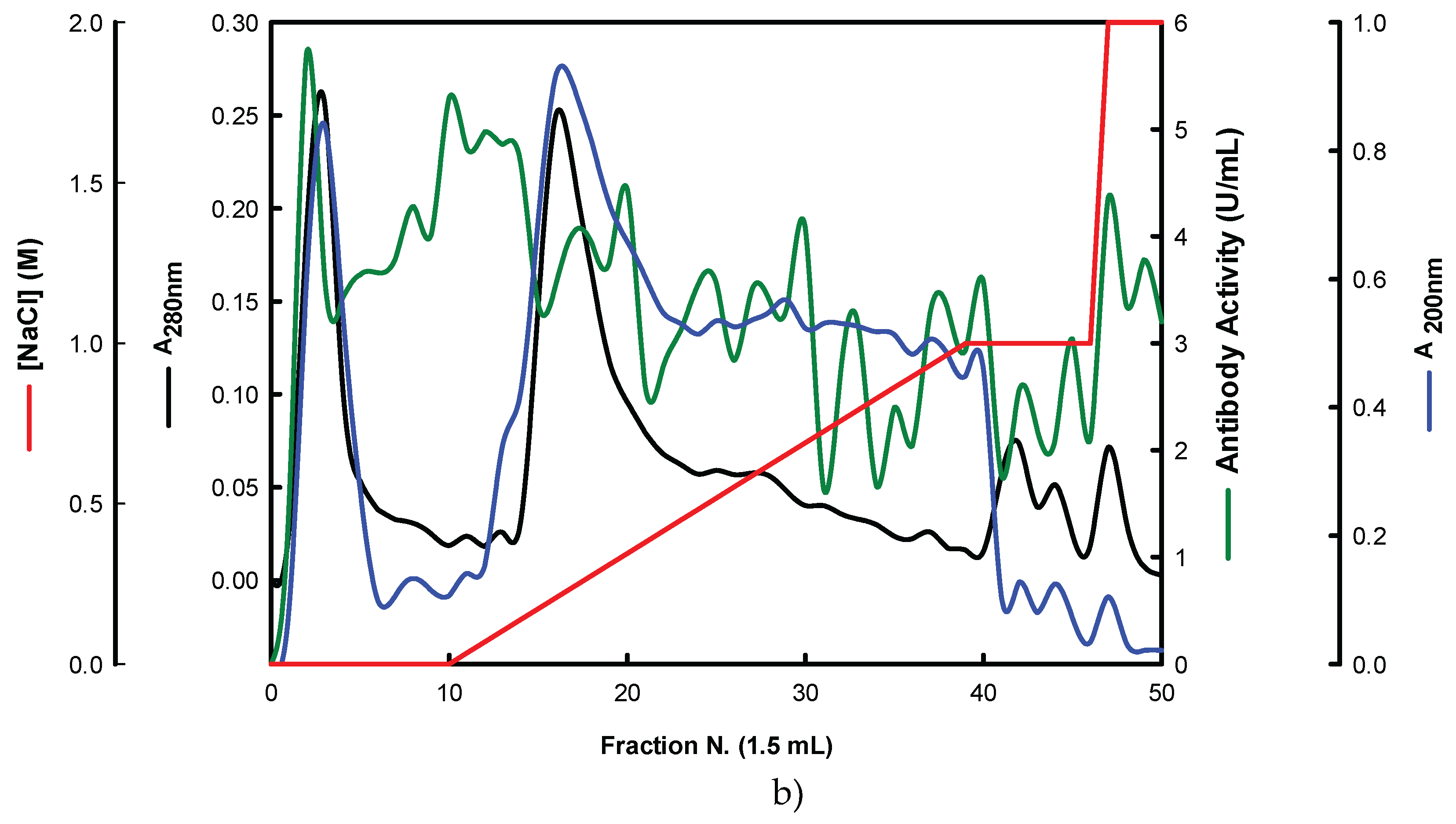

2.3.12. Purification of EBG by Anion-Exchange Chromatography

Extracellular β-glucans from P. osreatus were also purified by anion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-cellulose column (1 5 cm) which was previously equilibrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.8. The EBG were eluted from the column with a linear gradient of 0-1 M NaCl in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.8 at a flow rate of 20 mL/h. At the end of the linear gradient, the last four fractions were eluted with 2 M NaCl. The fractions (1.5 mL) were collected and analysed for total polysaccharide at A200, protein and as well as with Mabs 3F8 _3H7 and 1E6_1E8_B5.

2.3.13. FTIR Analysis of β-Glucans

In order to exploit the structural features of β-glucans, FTIR analysis was performed. All samples were previously freeze-dried with a UNICRYO MC2L. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vertex 70 (with OPUS 5.5 software) as KBr pellets, a total of 128 scans at a resolution of 2 cm-1 in a range of 400–4000 cm−1.

2.3.14. Interaction of Mabs with Native and Heat-Treated Antigens

The interaction of Mabs to native and heat-treated

β-glucans was also studied by indirect ELISA. EBG from

P. ostreatus and KOH extraction fractions from

C. versicolor and

A. blazei were incubated in a thermocycler at 100°C for 1h. The antigen was immobilized either immediately in the microtiter plates after heating or it was cooled in ice bath for 10 min before it was immobilized in microtiter plates in order to investigate the Mab reactivity. In the present assay, the EC

50 is defined as the amount of Mab required to give a 50% response on the dose–response sigmoid curve plotted with increasing concentration of Mabs [

26]. The EC

50 values were determined by using GraphPad Prism software v.6.05.

2.3.15. Assay of β- Glucans by Competitive ELISA

A constant concentration of Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 was incubated with different concentrations (0 – 25 μg/ ml) of selected antigens (i.e FNaOH from L. edodes and FKOH from H. erinaceus) at 37ºC for 1h. The resulting Mab–antigen complexes were transferred to the PolySorp® microplate wells (50 μL) which were previously coated with the same antigen for 120 h at 4ºC. Subsequently, the microtiter plates were washed to remove unbound Mab and treated the same way as in the indirect ELISA method.

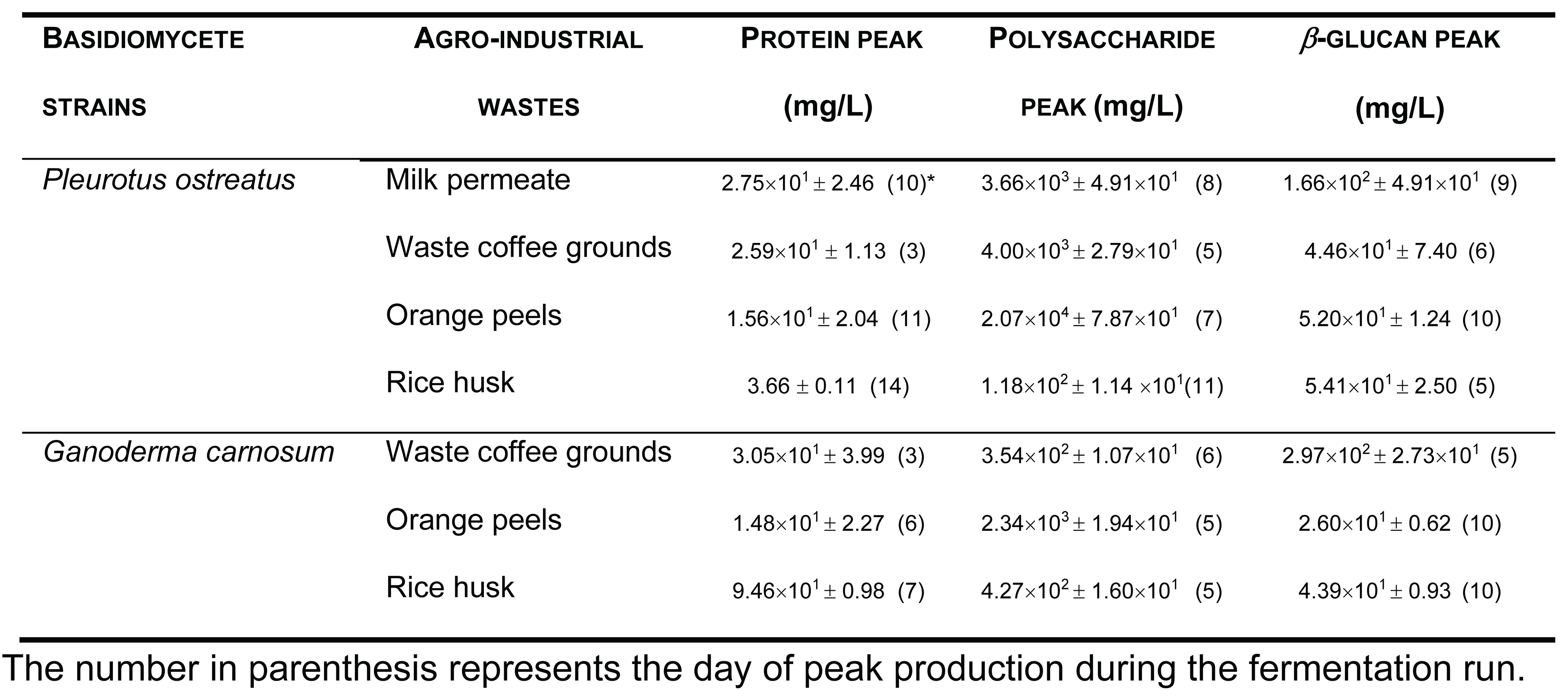

4. Discussion

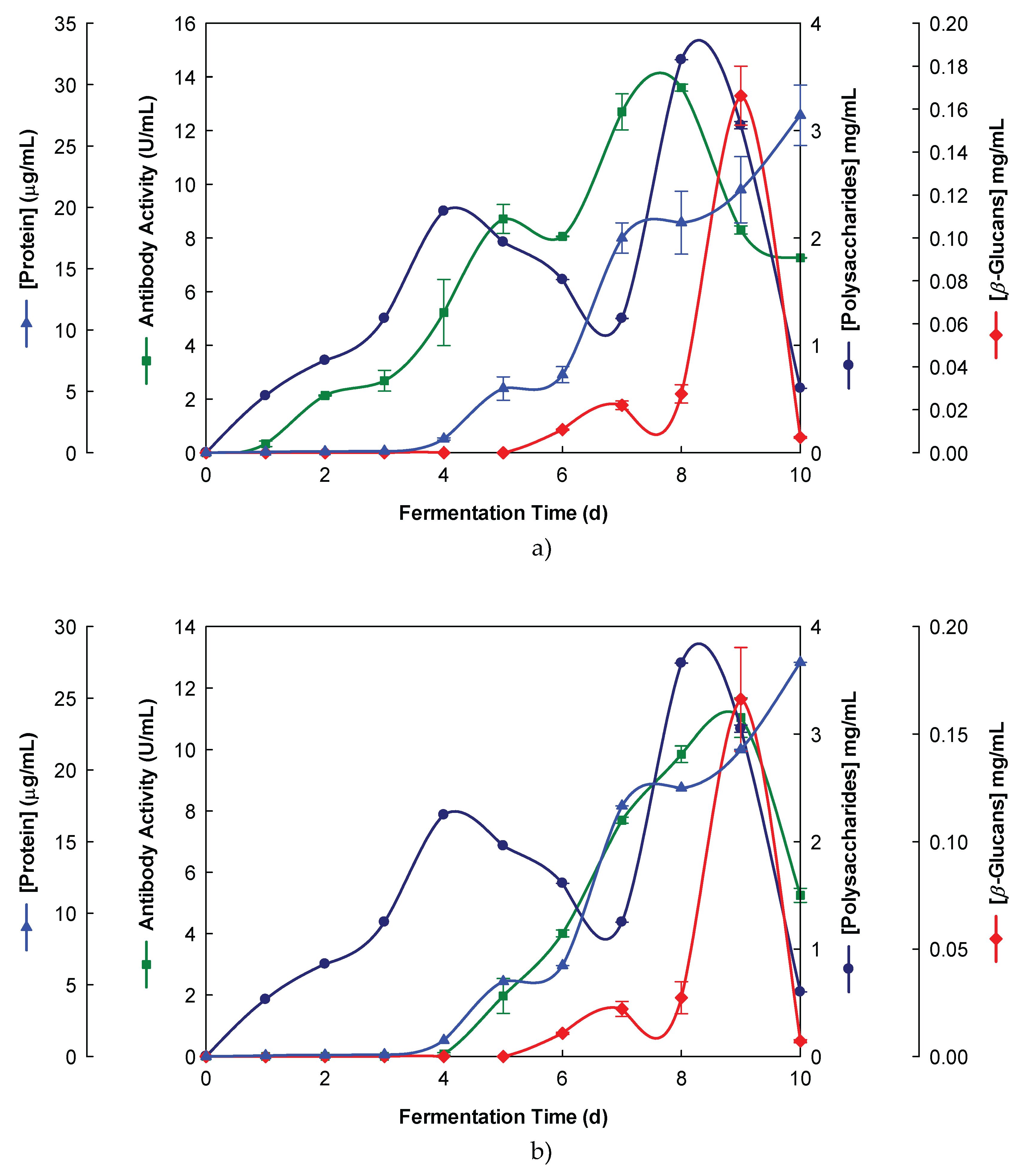

The peak production of β-glucans from

P. ostreatus by submerged fermentation occurred on the 9th day of fermentation by using milk permeate (

Figure 1 A and B). However, the fermentation profile for

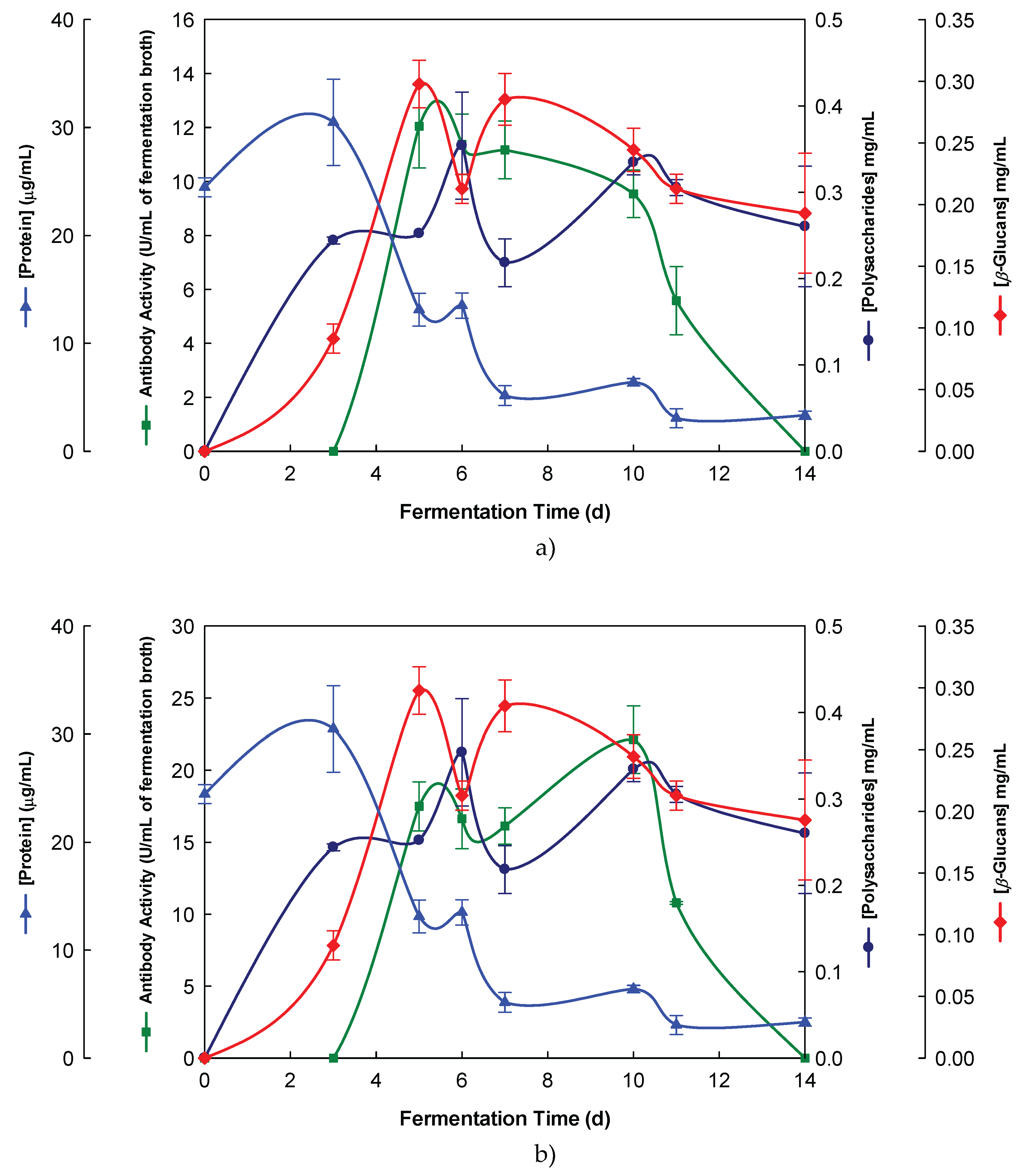

G. carnosum grown in waste coffee grounds exhibited the peak production of

β-glucan on the 5th day of fermentation (

Figure 2). The data in

Table 1 strongly suggest that peak production of

β-glucan occurred in the range of 5th-10th day of fermentation runs for both strains grown in agro-industrial wastes.

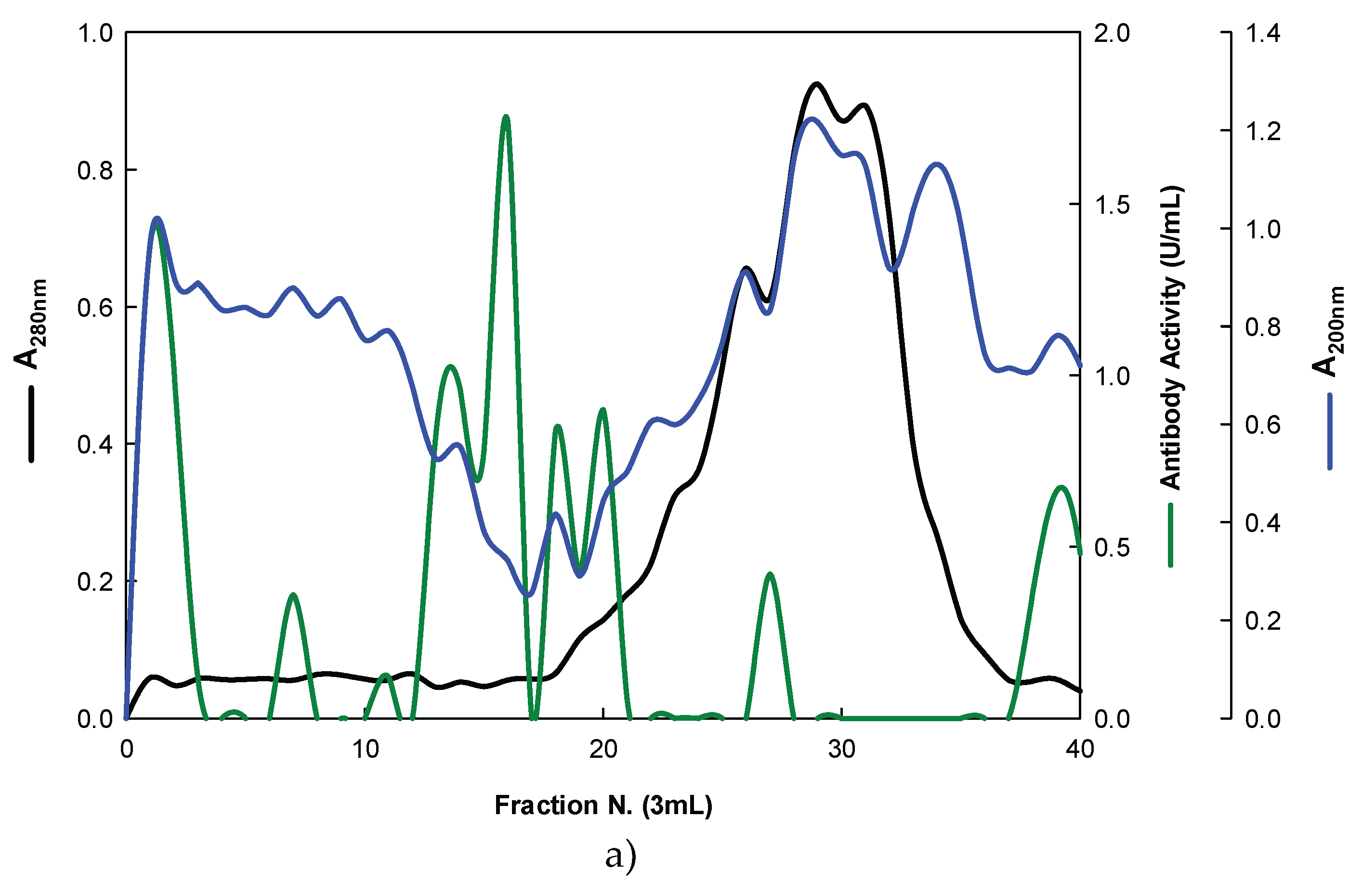

The results obtained for the purification of EBG from

P. ostreatus by gel filtration chromatography are in agreement with published work which reported a heterogeneous mixture of

β-glucans in mushroom basidiomycete mushroom strains with different Mr values and degree of ramification of

β-glucan chains [

13,

14,

15,

27]. The specific detection of polysaccharides in column fractions by Mab IgM is apparently in agreement with Mab IgG (

Figure 3 A and B). The EBG from

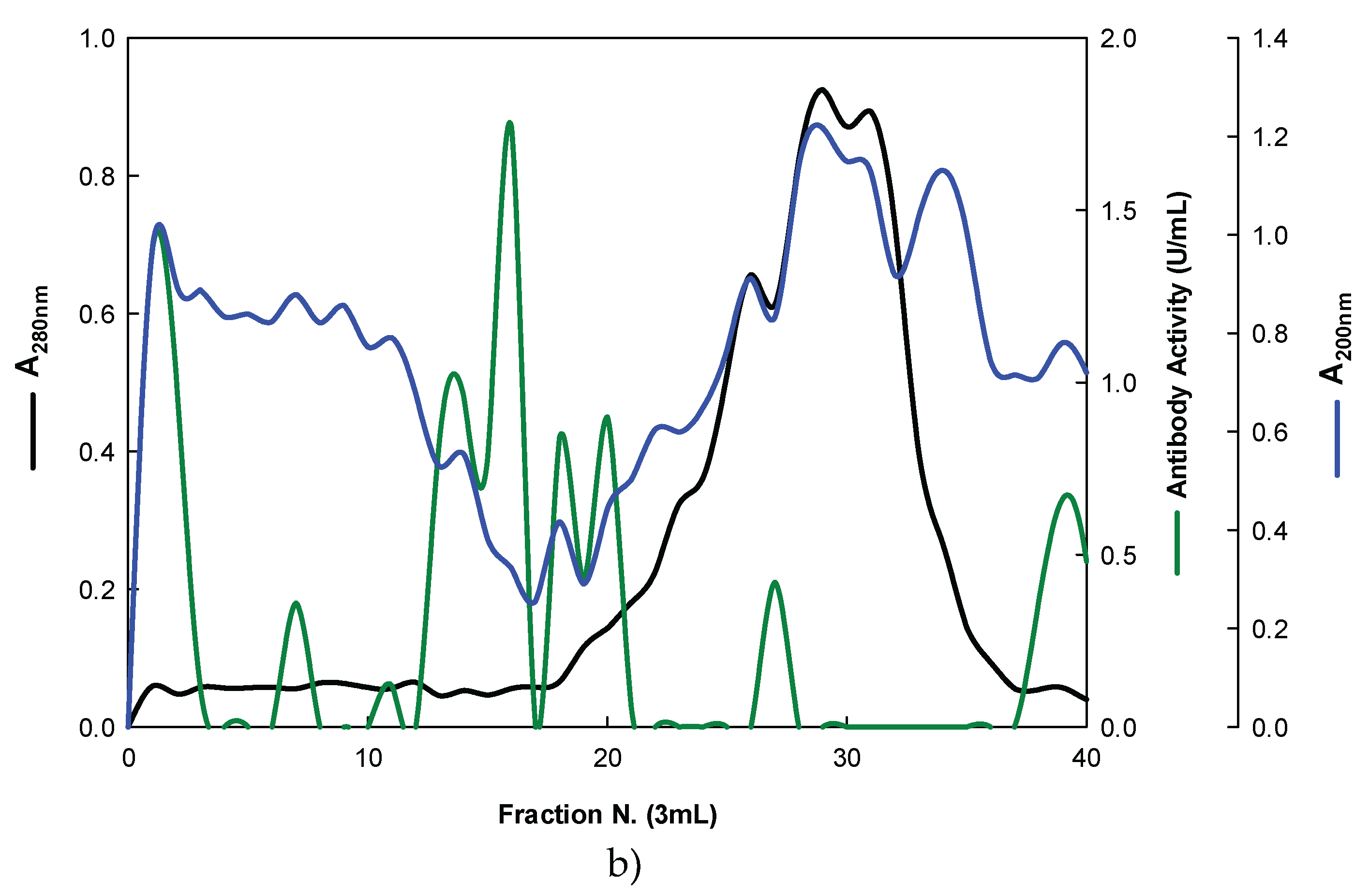

P. ostreatus was also purified by ion-exchange chromatography which revealed two main polysaccharide peaks (

Figure 4). One of the peaks was adsorbed to the column whereas the other peak did not bind to the column which suggests that apparently the latter is uncharged (data not shown). However, Mabs recognized strongly the neutral polysaccharide peak that did not bind to the column (

Figure 4 A and B) whereas the Mab reacted weakly to the charged peak. It is not possible to compare these results with data in the literature since there are no published reports regarding the purification of

β-glucans from

P. ostreatus by these two chromatographic techniques.

The study of the effect of time and temperature on adsorption of

β-glucans as antigens on microtiter plates revealed that the signal obtained in indirect ELISA was highest at higher temperature and longer periods of antigen immobilization for EBG from

P. ostreatus whereas IBG exhibited higher signal at 37º C and shorter periods of immobilization (

Figure 5 A). Although,

Figure 5 B presents the data on

A. blazei and

I. obliquus which revealed the highest signal at higher temperature and longer periods of

β-D-glucan immobilization. It can be observed in

Figure 5 C that the highest value was obtained either at lower or higher temperature and longer periods of

β-D-glucan immobilization for

P. cocos whereas

C. versicolor and

P. umbellatus exhibited at higher temperature (i.e., 37ºC) and longer periods of immobilization.

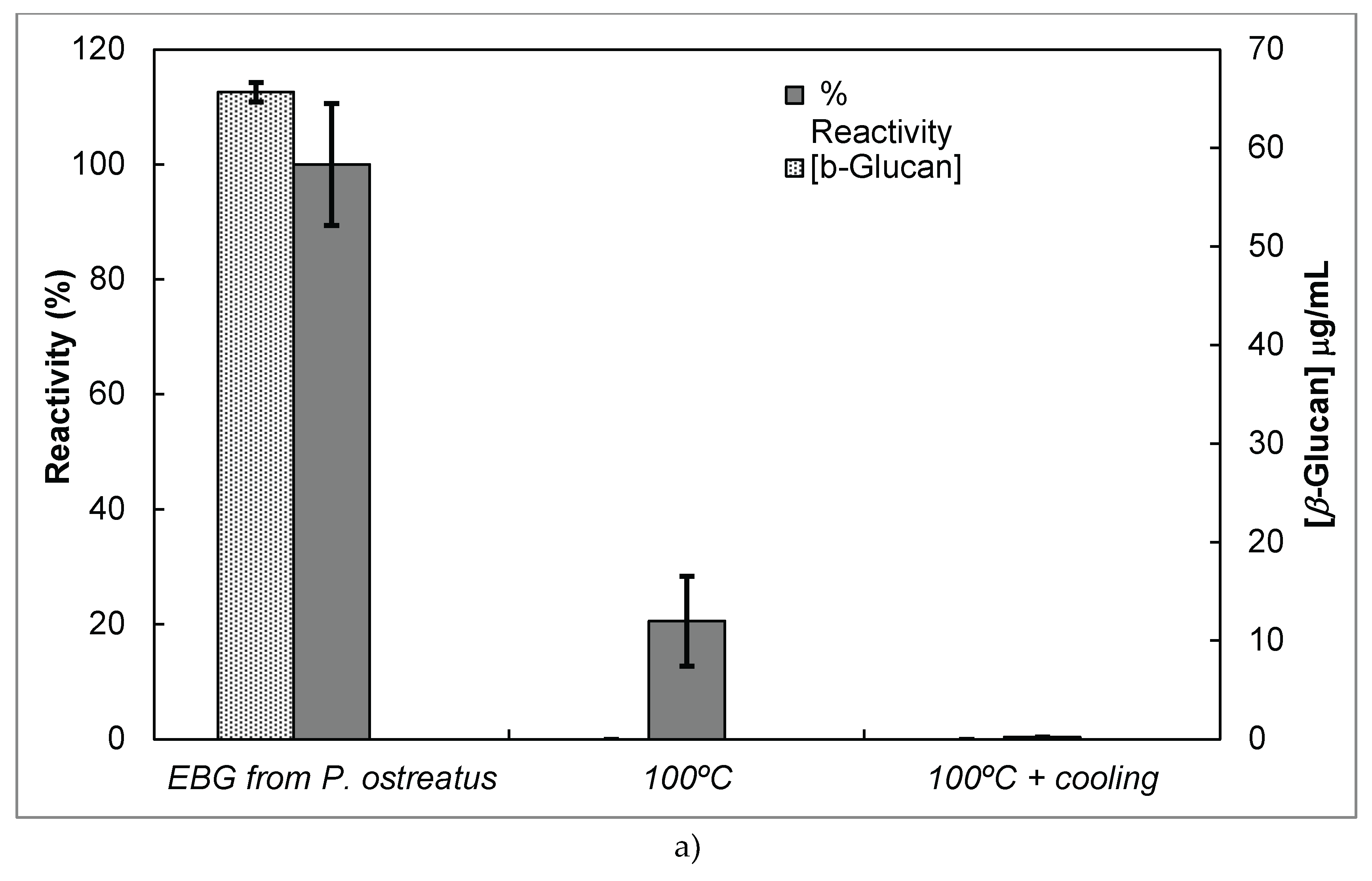

Several published reports have presented significant evidence for conformational changes of heat-treated β-glucans from several basidiomycete strains because of their structural transition from triple helix to random coil [

13,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Similar data have been published by other researchers on Mabs raised against porcine growth hormone and troponin subunits, which detected conformational changes on the antigen molecule [

26,

31]. On the other hand, some research workers have found that some Mabs raised against native proteins have revealed preferential binding to the denatured form of proteins [

32]. In the present work, Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 exhibited a lower affinity for heat-treated

β-glucans from

P. ostreatus compared with the native

β-D-glucans (

Figure 6 A). However, this Mab has revealed a higher and lower affinity for the heat-treated

β-glucans from

A. blazei and

C. versicolor than for the native

β-glucans, respectively (

Figure 6 B and C). The effect of cooling after the heat treatment was investigated on EC

50 which suggests that the Mab did not recognize cooled

β-glucans from

P. ostreatus. However, the Mab has revealed a lower and higher affinity for

β-glucans from

A. blazei and

C. versicolor, respectively (

Figure 6 B and C). During this investigation, the data on Mab reactivity was compared with Congo red assay which only recognizes and monitors

β-glucans with a triple helix structure [

30]. Therefore, Congo red assay did not detect heat-treated

β-glucans from

P. ostreatus which strongly indicates that heat treatment damaged its triple helix structure (

Figure 6 A). On the other hand, Congo red assay detected higher levels of heat-treated

β-glucans from

A. blazei and

C. versicolor compared with the native forms (

Figure 6 B and C). The effect of cooling after the heat treatment on β-glucan concentrations by Congo red assay shows that it did not detect cooled

β-glucans from

P. ostreatus whereas it exhibited lower values for

β-glucans from

A. blazei and

C. versicolor compared with the heat- treated forms (

Figure 6). Therefore, the data presented in

Figure 6 exhibits strong evidence that Mabs detected conformational changes in

β-glucans from mushroom strains as a result of heating and cooling treatments.

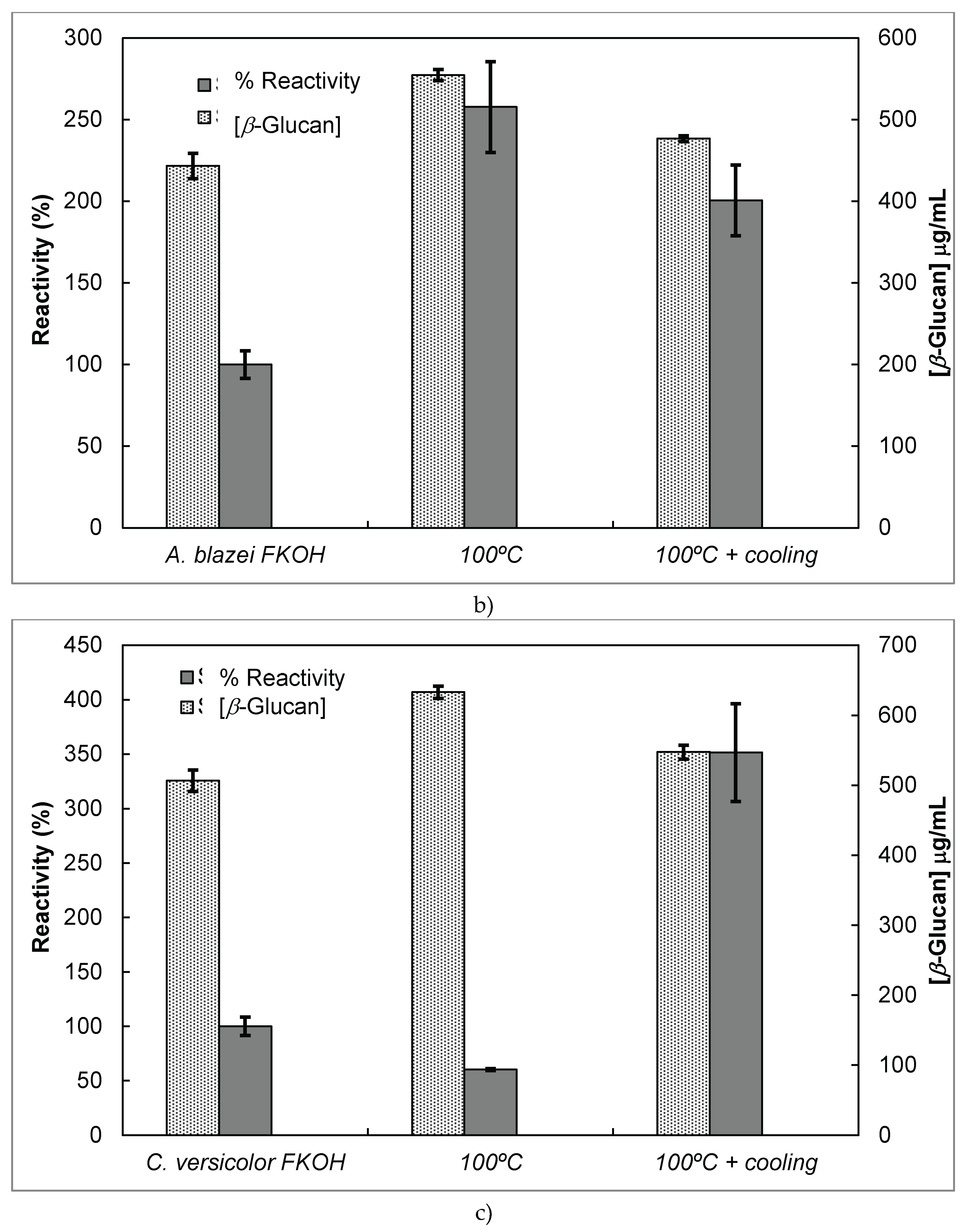

The data presented in

Figure 7 strongly suggest that Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 can be used in

β-D-glucans assay by competitive ELISA in mushroom strains since A

415 was inversely proportional to soluble

β-D-glucan concentration.

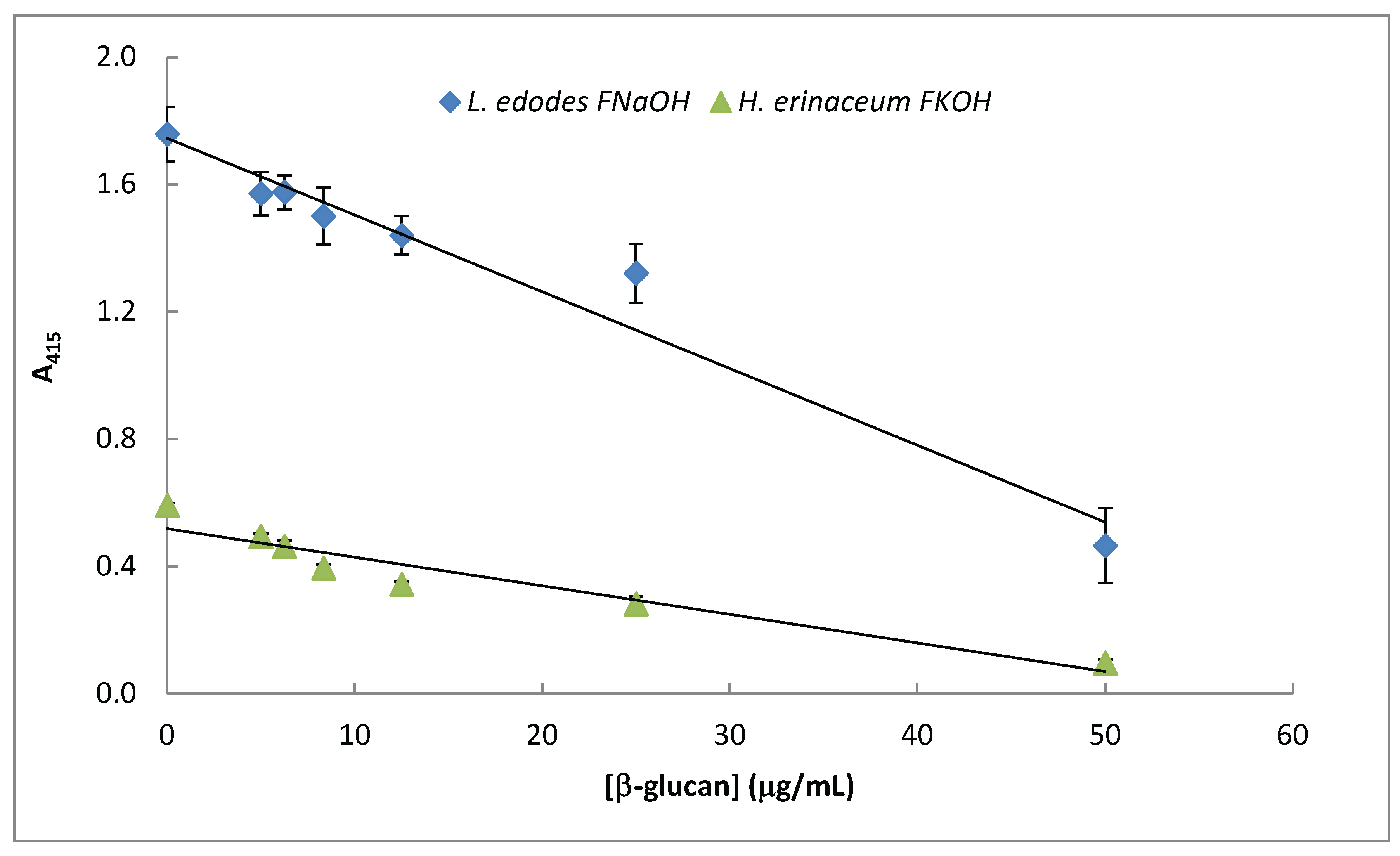

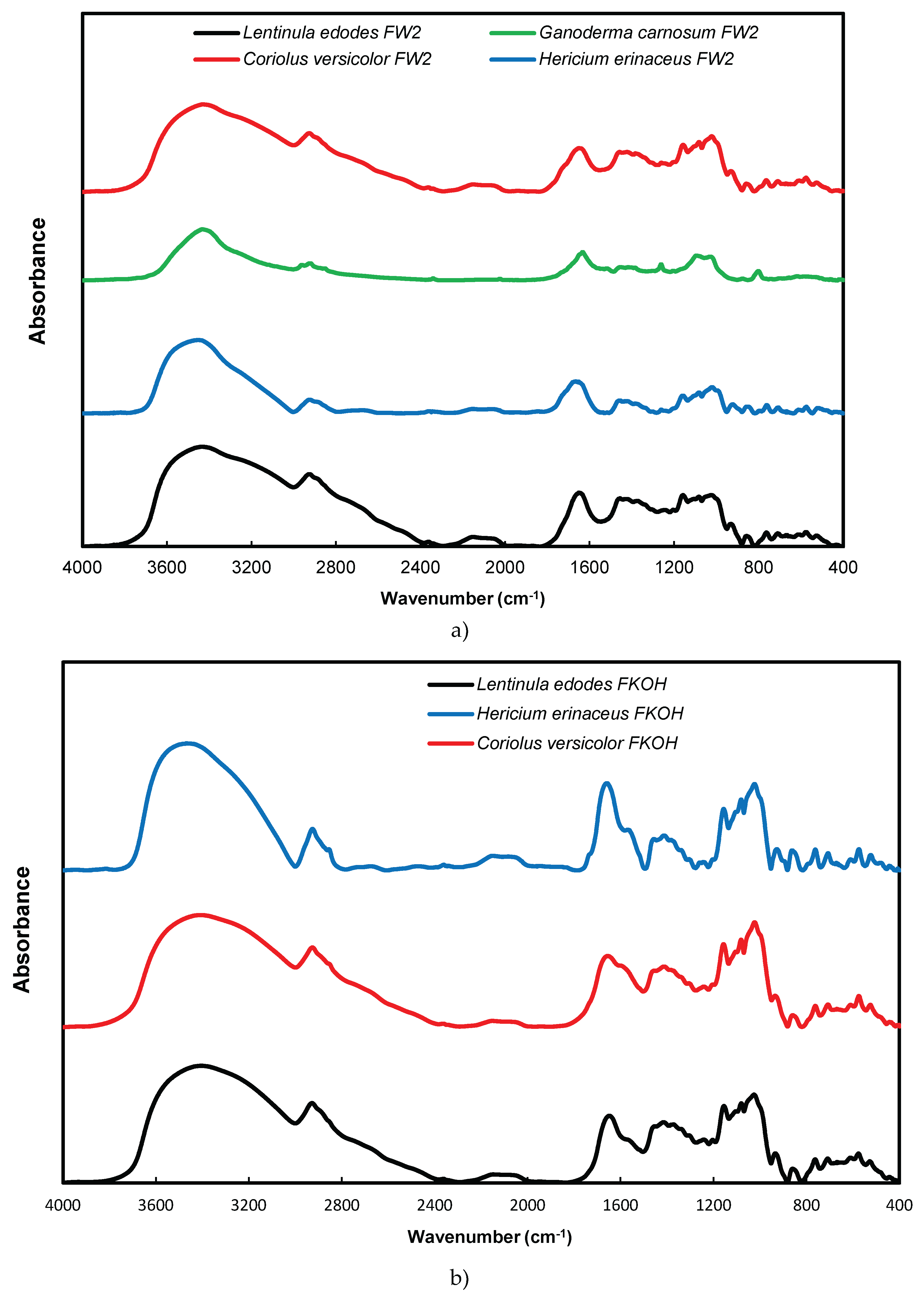

In order to identify some structural characteristics of β-glucans some FTIR spectra from basidiomycete fractions were obtained and the data are in agreement with some reports in the literature on mushroom

β-D-glucans [

14,

23,

33].

To author’s knowledge, this is the first report about the use of Mabs of IgG and IgM for monitorization of β-D-glucan production from basidiomycete mushroom strains in agro-industrial wastes. The immunochemical detection of these β- glucans correlated well with Congo red assay for β-D-glucan. These Mabs are powerful tools to detect changes in conformation in β-glucans from basidiomycete strains due to heat and cooling treatments. Since this Mab was successfully used in competitive ELISA assay, it could be used to design an immunosensor for motorization and quantification of these polysaccharides from novel mushroom strains. Moreover, since it detects changes in conformation in β-D-glucan molecules, this biosensor would be very useful to find novel polysaccharides with novel biological activities.

Abbreviations

BRM – Biological response modifiers

EBG – Extracellular β-glucans

ELISA - Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

IBG - Intracellular β-glucans

Mabs - Monoclonal antibodies

PBS - Phosphate buffered saline

PDA – Potato dextrose agar

Figure 1.

Production of β-glucans from P. ostreatus in culture medium containing milk permeate. The fermentation broth was monitored for levels of protein, total polysaccharides, β-glucans and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using (a) Mab 3F8_3H7 and (b) Mab 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 1.

Production of β-glucans from P. ostreatus in culture medium containing milk permeate. The fermentation broth was monitored for levels of protein, total polysaccharides, β-glucans and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using (a) Mab 3F8_3H7 and (b) Mab 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 2.

Production of β-glucans from Ganoderma carnosum in culture medium containing waste coffee grounds. The fermentation broth was monitored for levels of protein, total polysaccharides, β-glucans and immunochemical detection of β-D-glucans by indirect ELISA using (a) Mab 3F8_3H7 and (b) Mab 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 2.

Production of β-glucans from Ganoderma carnosum in culture medium containing waste coffee grounds. The fermentation broth was monitored for levels of protein, total polysaccharides, β-glucans and immunochemical detection of β-D-glucans by indirect ELISA using (a) Mab 3F8_3H7 and (b) Mab 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 3.

Purification of EBG from P. ostreatus by gel filtration chromatography on Sephacryl S-300HR. Column fractions were analysed for levels of polysaccharides, proteins and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using Mabs: (a) 3F8_3H7; (b) 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 3.

Purification of EBG from P. ostreatus by gel filtration chromatography on Sephacryl S-300HR. Column fractions were analysed for levels of polysaccharides, proteins and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using Mabs: (a) 3F8_3H7; (b) 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 4.

Purification of EBG from P. ostreatus by Ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-cellulose anion exchange media. Column fractions were analysed for levels of polysaccharides, proteins and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using Mabs: (a) 3F8_3H7; (b) 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 4.

Purification of EBG from P. ostreatus by Ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-cellulose anion exchange media. Column fractions were analysed for levels of polysaccharides, proteins and immunochemical detection of β-glucans by indirect ELISA using Mabs: (a) 3F8_3H7; (b) 1E6_1E8_B5.

Figure 5.

Adsorption of antigens on microtiter plates by using different temperatures (4 and 37ºC) and time periods (1-120h) for indirect ELISA. Polysorp® microtiter plates were coated with FKOH fractions of β-glucans (20 μg) and were incubated at 4 and 37ºC between 1 and 120 h to perform indirect ELISA with Mab 1E6_1E8_B5; (a) – EBG and IBG from P. ostreatus; (B) – β- glucans from A. blazei and I. obliquus; (C) – β-D-glucans from P. umbellatus, P. cocos and C. versicolor.

Figure 5.

Adsorption of antigens on microtiter plates by using different temperatures (4 and 37ºC) and time periods (1-120h) for indirect ELISA. Polysorp® microtiter plates were coated with FKOH fractions of β-glucans (20 μg) and were incubated at 4 and 37ºC between 1 and 120 h to perform indirect ELISA with Mab 1E6_1E8_B5; (a) – EBG and IBG from P. ostreatus; (B) – β- glucans from A. blazei and I. obliquus; (C) – β-D-glucans from P. umbellatus, P. cocos and C. versicolor.

Figure 6.

Reactivity of Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 to native and heat-treated forms of β-glucans and Congo red assay for β-glucan with triple helix conformation. Β-glucan fractions (25 μg) from mushroom strains were heated at 100°C and the antigens were immobilized to microtiter plates as described in Materials and Methods. The antigen-binding with Mab, to native and heat-treated forms of β-glucan was determined by indirect ELISA. The conformational changes in β-glucan were detected by Congo red assay in both native and heat-treated β-glucans. (a) – Reactivity of Mabs to EBG from P. ostreatus and Congo red assay for β-glucans; (b) – Reactivity of Mabs to FKOH from A. blazei as well as the Congo red assay; (c) – Reactivity of Mabs to FKOH from C. versicolor as well as the Congo red assay.

Figure 6.

Reactivity of Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 to native and heat-treated forms of β-glucans and Congo red assay for β-glucan with triple helix conformation. Β-glucan fractions (25 μg) from mushroom strains were heated at 100°C and the antigens were immobilized to microtiter plates as described in Materials and Methods. The antigen-binding with Mab, to native and heat-treated forms of β-glucan was determined by indirect ELISA. The conformational changes in β-glucan were detected by Congo red assay in both native and heat-treated β-glucans. (a) – Reactivity of Mabs to EBG from P. ostreatus and Congo red assay for β-glucans; (b) – Reactivity of Mabs to FKOH from A. blazei as well as the Congo red assay; (c) – Reactivity of Mabs to FKOH from C. versicolor as well as the Congo red assay.

Figure 7.

Assay of mushroom β-D-glucans by competitive ELISA. A constant concentration of Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 was incubated with different concentrations (0 – 25 μg/ ml) of selected β- glucans ( i.e FnaOH from L. edodes and FKOH from H. erinaceus) at 37ºC for 1h. The resulting Mab–β- glucans complexes were transferred to the PolySorp® microplate wells (50 μL) which were previously coated with the same antigen for 120 h at 4ºC. Subsequently, the microtiter plates were washed to remove unbound Mab and treated the same way as in the indirect ELISA method.

Figure 7.

Assay of mushroom β-D-glucans by competitive ELISA. A constant concentration of Mab 1E6_1E8_B5 was incubated with different concentrations (0 – 25 μg/ ml) of selected β- glucans ( i.e FnaOH from L. edodes and FKOH from H. erinaceus) at 37ºC for 1h. The resulting Mab–β- glucans complexes were transferred to the PolySorp® microplate wells (50 μL) which were previously coated with the same antigen for 120 h at 4ºC. Subsequently, the microtiter plates were washed to remove unbound Mab and treated the same way as in the indirect ELISA method.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of FW2 and FKOH from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor- FTIR spectra. (a) – FW2 from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor; (b) - FKOH from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of FW2 and FKOH from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor- FTIR spectra. (a) – FW2 from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor; (b) - FKOH from L. edodes, H. erinaceus and C. versicolor.

Table 1.

Fermentation runs by using these two basidiomycete strains in the presence of several agro-industrial wastes.

Table 1.

Fermentation runs by using these two basidiomycete strains in the presence of several agro-industrial wastes.