1. Introduction

Nowadays, several compounds have been found that have been of great importance either in human health or in their industrial, food, pharmaceutical applications, among others. These compounds are called polyphenolics, these are secondary metabolites found in plants and fruits [

1], they have been classified into several groups, among them are condensed tannins which are olimgomers or polymers of flavan-3-ols and flavan-3,4-diols [

2], these are also considered proanthocyanidins and among the most common are epicatechin, gallocatechin, catechin and epigallocatechin; there are also the so-called hydrolyzable tannins, esters of gallic acid considered gallotannins and ellagic acid considered ellagitannins, which have a sugar core and are easily hydrolyzed by enzymatic action [

3,

4].

These compounds have been of great interest since it has been proven that they have biological activities such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, chemotherapeutic, antiglycemic and other properties, and they are also beneficial to health and can be applied in medicines, food supplements, dermatological products, even cosmetics, among others [

3,

5]. Bioactive compounds have been found in various fruits such as grape, orange, pomegranate, rambutan and pineapple is no exception, these compounds have been found in the fresh fruit, which corresponds to 70% of the total fruit, however there is a drawback in the industrialization of this fruit as it generates about 60% of waste consisting of the skins, heart, leaves and crown [

6]. For this reason, alternatives are being sought to use this type of waste, among the possible uses are the manufacture of textiles, paper, animal feed [

7], bioethanol production [

8], production of recycled packaging [

9], preparation of natural pigments [

10], among others.

However, it has been shown that pineapple waste are also a potential source for obtaining polyphenols [

11]. Minerals (magnesium, potassium, zinc, sodium, among others), different vitamins such as A, C, K and E [

12], aromatic compounds such as limonene, ethyl hexanoate, butyl acetate, 1-butanol, furfural, among others [

13]. Several conventional and emerging technologies have been used to obtain this type of compounds, including soxhlet-assisted extraction, liquid-liquid extraction, vapor extraction, infusion, ultrasound extraction [

14], autohydrolysis [

15], microwave, supercritical fluid extraction [

16].

Currently, new environmentally friendly alternatives are being sought for obtaining polyphenolic compounds, among the alternatives are biotechnological ones such as fermentation, either in the solid state (which is considered as such because it is in the absence of water but at optimum moisture levels so that the microorganism can grow) [

17,

18] or fermentation in the liquid state, as its name suggests, is carried out in a liquid medium under certain conditions of pH, inoculum, oxygen and aeration; these biotechnological processes produce enzymes that help the release of polyphenolic compounds, which is why it is a promising alternative [

18].

Although fermentation methods were already known, nowadays it has gained more interest due to its simplicity and proximity to the natural conditions of the microorganisms used, whether yeast or fungi [

17]. Within the fermentation processes, agro-industrial waste have been used, since the aim is to make better use of these waste, such is the case of pineapple. In order to take advantage of these waste, the objective of the present work is to evaluate the conditions of the solid-state fermentation process using

Aspergillus niger spp. for the release of polyphenolic compounds from pineapple peels and to determine the best conditions for obtaining them, as well as to determine their antioxidant capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining Pineapple Husk Waste

Pineapple husk waste were collected from a local market located in the center of the city of Saltillo, Coahuila. The waste was cut into small pieces, washed, and placed in containers and dried in an oven (Blast Drying Oven, WGL-65B) at 60 °C for 72. Once dried it was ground in a blender finally obtaining a powder.

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Pineapple Waste

The water absorption index (WIA) and the critical moisture point (HCP) were determined according to the methodology reported by Buenrostro-Figueroa et al. [

19]. For IAA, 1.5 g of dry matter was placed in a 50 mL falcon tube with 15 mL of distilled water, shaken manually for 1 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the IAA was calculated from the remaining weight of the gel expressed in g gel/g dry weight. The HWP was estimated by the addition of 1 g of sample on a thermobalance (OHAUS, Parsippany, UN, USA).

2.3. Proximate Analysis of Pineapple Waste

The proximate analysis consisted of the determination of moisture content, ash content and fat content according to the AOAC methodology according Polania-Rivera et al. [

20]. Total carbohydrate content was determined by the phenol-sulfuric method according to Polonia-Rivera et al. [

20] with some modifications where a standard curve was performed with dextrose with a concentration of 0 - 140 ppm, reducing sugars were determined according to Amaya-Chantaca et al. [

21]. The protein content was carried out according to the Lowry spectrophotometric method according to the methodology reported by Redmile-Gordon et al. [

22] Fiber determination was determined according to that reported by Púa et al. [

23].

2.4. Evaluation of Fungal Strains with Invasive Capacity on Pineapple Peel Waste

Five fungal strains from the Food Research Department of the Autonomous University of Coahuila, which were previously identified and characterized (

Aspergillus HT3,

Aspergillus niger GH1,

Aspergillus niger Aa20,

Aspergillus Aa120,

Aspergillus oryzae) were evaluated. The strains were reactivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 30 °C for 5 days. The invasive growth capacity of the microorganism was evaluated using ground pineapple husk as substrate according to the methodology reported by Espita-Hernández et al. [

24]. Growth kinetics was performed by taking measurements every 24 h for 5 days and determining the growth rate [

25]. Subsequently, extractions were performed by recovering with 15 mL of ethanol (50%), for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Quantification of Polyphenolic Compounds

Hydrolyzable tannins (HT) were determined according to the methodology described by Espita-Hernández et al. [

24], with some modifications, 20 µL of fermentation extract (samples were diluted at 1:100) were placed in a microplate well, then 20 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent were added and allowed to stand for 5 min, then 20 µL of sodium carbonate (0.01M) were added and allowed to stand for 5 min, finally diluted in 125 µL of distilled water and read at 750 nm in a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan). Values were calculated using a gallic acid calibration curve (0 - 200 ppm). Hydrolyzable tannin content was expressed as mg/g pineapple peel weight. Condensed tannins (CT) were determined according to the methodology described by Palacios et al. [

26], with some modifications, a solution of HCl-Terbutanol was prepared in a ratio of 1:9 (10 mL of HCl at 37% volumetric in 100 mL of terbutanol), then 70 mg of FeSO

4.7H

2O were added. The fermentation extract was taken 333 µL (the samples were diluted 1:100), then 2 mL of HCl-Butanol were added and capped, placed in a tube rack and heated for 1 h at 100 ºC, after which time they were allowed to cool to room temperature and 180 µL were taken from each tube and placed in a microplate well and read at 450 nm. Values were calculated using a catechin calibration curve (0 - 1500 ppm). The CT content was expressed as mg/g of pineapple peel weight.

2.6. Evaluation of Solid-State Fermentation (SSF) Conditions Using Pineapple Peel Waste for the Release of Bioactive Compounds

An exploratory Plackett-Burman design for the release of polyphenols was used to evaluate the SSF conditions. The design used two levels (+1, -1), 7 factors which were temperature, humidity, inoculum, NaNO

3, MgSO

4, KCl and KH

2PO

4 and 8 treatments, which were performed in triplicate, the factors and treatment are shown in

Table 1. The response variable was the amount of HT and CT, its quantification was performed according to the methodologies of section 2.5. The extracts were recovered by adding 15 mL of an ethanol: water mixture (50% v/v) and then filtered and stored for further analysis.

2.7. Analysis of the Polyphenolic Content of the Fermentation Extracts by RP-HPLC-ESI-MS

For the identification of the polyphenolic content of the fermentation extracts, they were filtered with a 0.45µm nylon membrane, then 1.5 mL were taken and placed in a vial for chromatography. The identification was carried out according to the methodology reported by Ascacio et al. [

27]. The analyses by Reverse Phase-High Performance Liquid Chromatography were performed on a Varian HPLC system including an autosampler (Varian ProStar 410, USA), a ternary pump (Varian ProStar 230I, USA) and a PDA detector (Varian ProStar 330, USA). A liquid chromatograph ion trap mass spectrometer (Varian 500-MS IT Mass Spectrometer, USA) equipped with an electrospray ion source also was used.

2.8. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity

The free radical trapping capacity was performed using the methodology described by Sepúlveda et al. [

15], with some modifications, a standard solution of Trolox was prepared from 0 to 200 ppm. The DPPH radical (Sigma Aldrich) was prepared at a concentration of 60 µM in methanolic solution. 193 µL of DPPH-Methanol solution and 7 µL of fermentation extract were added, methanol alone was used as blank and DPPH-methanol solution was used as control absorbance. The absorbance wavelength of the radical was determined by scanning in the visible range at 540 nm. The radical uptake activity will be obtained according to equation (1):

where

Ac is the control absorbance and

Am is the absorbance of the sample.

The decolorization of the ABTS radical was performed using the methodology of Sepulveda et al. [

15], with some modifications, a standard solution was prepared from a range of 0 to 200 ppm. Subsequently, a 7 mM ABTS solution (Sigma Aldrich) was prepared and mixed with a solution of K₂S₂O₂O₈ until the latter had a concentration of 2.45 mM. It was allowed to stand in the dark for 12 h at room temperature. 193 µL ABTS solution and 7 µL fermentation extract were placed, ethanol was used as the reading blank and ABTS-ethanol as the control absorbance. A wavelength of 750 nm was used. The results were expressed according to equation 1.

The FRAP method was carried out according to Espita-Hernández et al. [

24] with some modifications. FRAP reagent was prepared daily, and maintained at 37 °C, by mixing acetate buffer (0.3 M pH 3.6) with a 10 mM solution of TPTZ (Sigma Aldrich) in 40 mM HCl, and a 20 mM solution of FeCl

3.6H

2O, in a 10:1:1 ratio. Assay solutions were prepared by mixing 180 μL of FRAP reagent with 24 μL of a 3:1 ratio water/sample mixture. A wavelength of 595 nm was used. The polyphenolic content was analyzed according to the methodology of section 2.7, of the treatments with the best antioxidant activity.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Pineapple Peel

In order to carry out the SSF process, it is necessary to know certain parameters, such as the water absorption index (WIA), which is the amount of water absorbed by the support [

28], and the critical moisture point (CMP), which is the water bound to the support [

29]. In the present study, pineapple peel obtained values of 5.42 ± 0.47 g gel/g dry peel and 4.60 % ± 1.03 of IAA and PCH, respectively. According to the methodologies used for proximate analysis of pineapple peel, it presented a moisture content of 8.90% ± 0.86, as well as an ash content of 1.62% ± 0. 99, regarding fat content, a value of 3.78% ± 0.46 was obtained, total sugars were determined giving a value of 39.63% ± 6.04, and reducing sugars were determined resulting in 34.88% ± 1.26, as for the protein content, a value of 6.63% ± 0.45 was determined and for fiber content a result of 20.90% ± 1.53 was obtained.

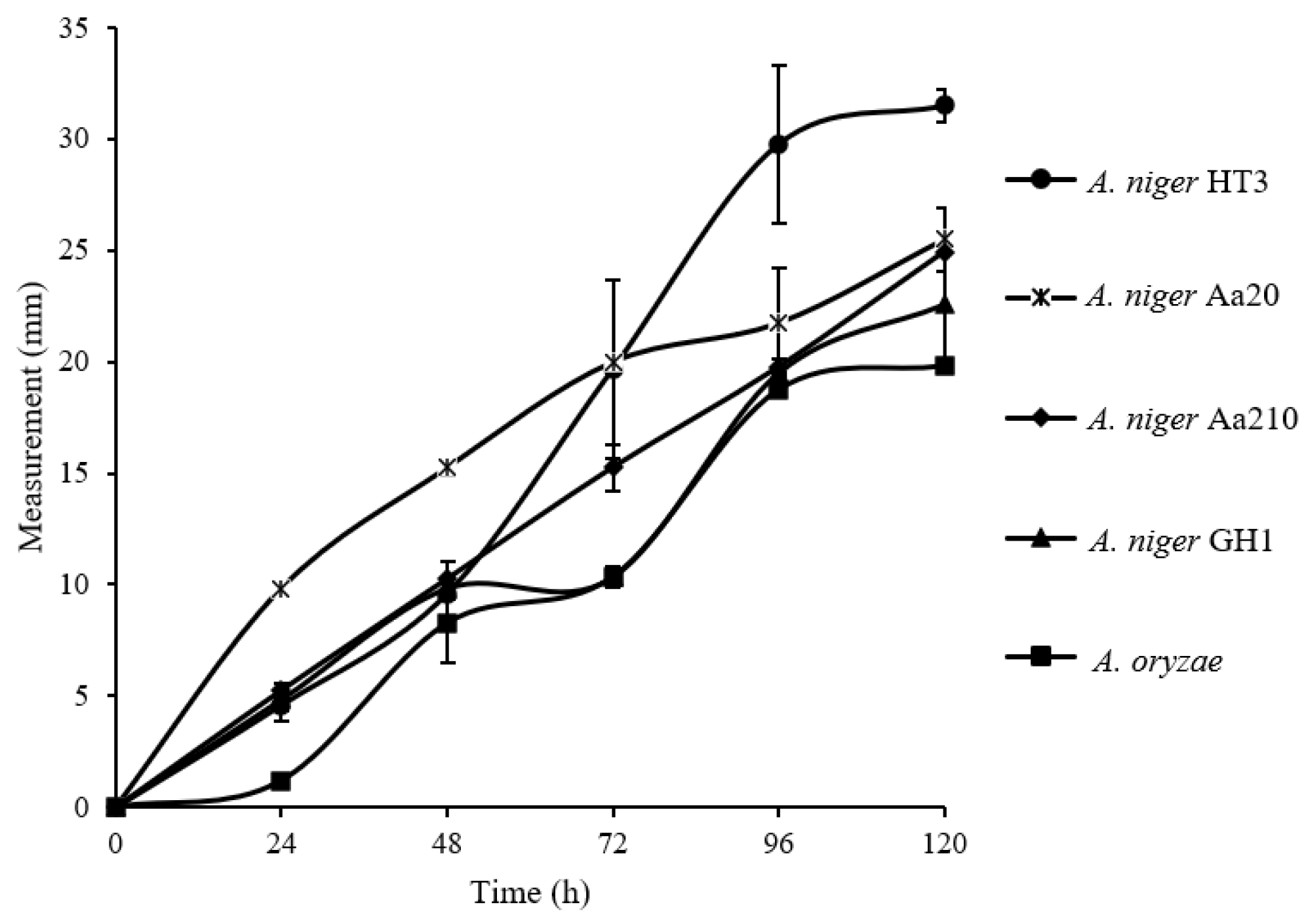

3.2. Evaluation of Fungal Strains with Invasive Growth Capacity

For the radial growth evaluation, six

Aspergillus strains were used (

A. niger HT3,

A. niger Aa210,

A. niger Aa20,

A. niger GH1,

A. oryzae), according to

Figure 1, it is observed that there is no significant difference between the

Aspergillus strains, however, determining the growth velocity,

A. niger A20 and

A. niger HT3 were the ones that adapted better to the substrate since a result of 0.039 mm/h and 0.038 mm/h was obtained, respectively, compared to the others, a lower growth rate was obtained, having as a result 0.036 mm/h, 0.033 mm/h, 0.033 mm/h, from the strains of

A. niger Aa210,

A. niger GH1 and

A. oryzae, respectively.

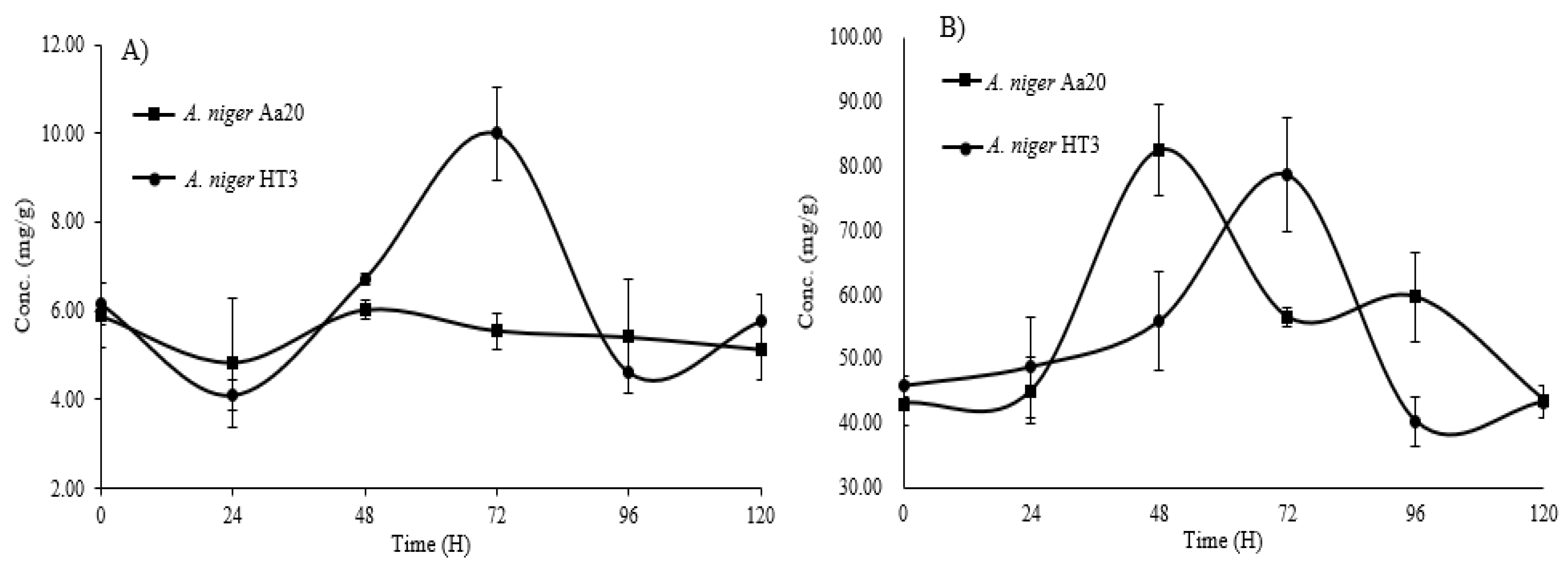

3.3. Quantification of Polyphenols from Fermentation Kinetics.

The

A. niger Aa20 and

A. niger HT3 strains were used for the quantification of HT and CT.,

Figure 2 A shown the quantification of HT with each of the strains used, for the

A. niger Aa20 strain there was a greater release of HT at 48 h, obtaining a result of 6.02 mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, however, for the

A. niger HT3 strain, it is observed that at 72 h there was a greater release of HT with a concentration of 10.00 mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, according to what was obtained,

A. niger HT3 was the strain that favored the release of these bioactive compounds.

Figure 2 B shown the quantification of CT for each of the strains used, it is observed that for the

A. niger Aa20 strain, at 48 h, the release of these bioactive compounds was the highest, with a concentration of 82.59 mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, for the strain of

A. niger HT3 at 72 h was the highest release of CT with a concentration of 78.71 mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, both strains favored the release of these bioactive compounds, however, the strain of

A. niger Aa20 was the one with the highest release of CT.

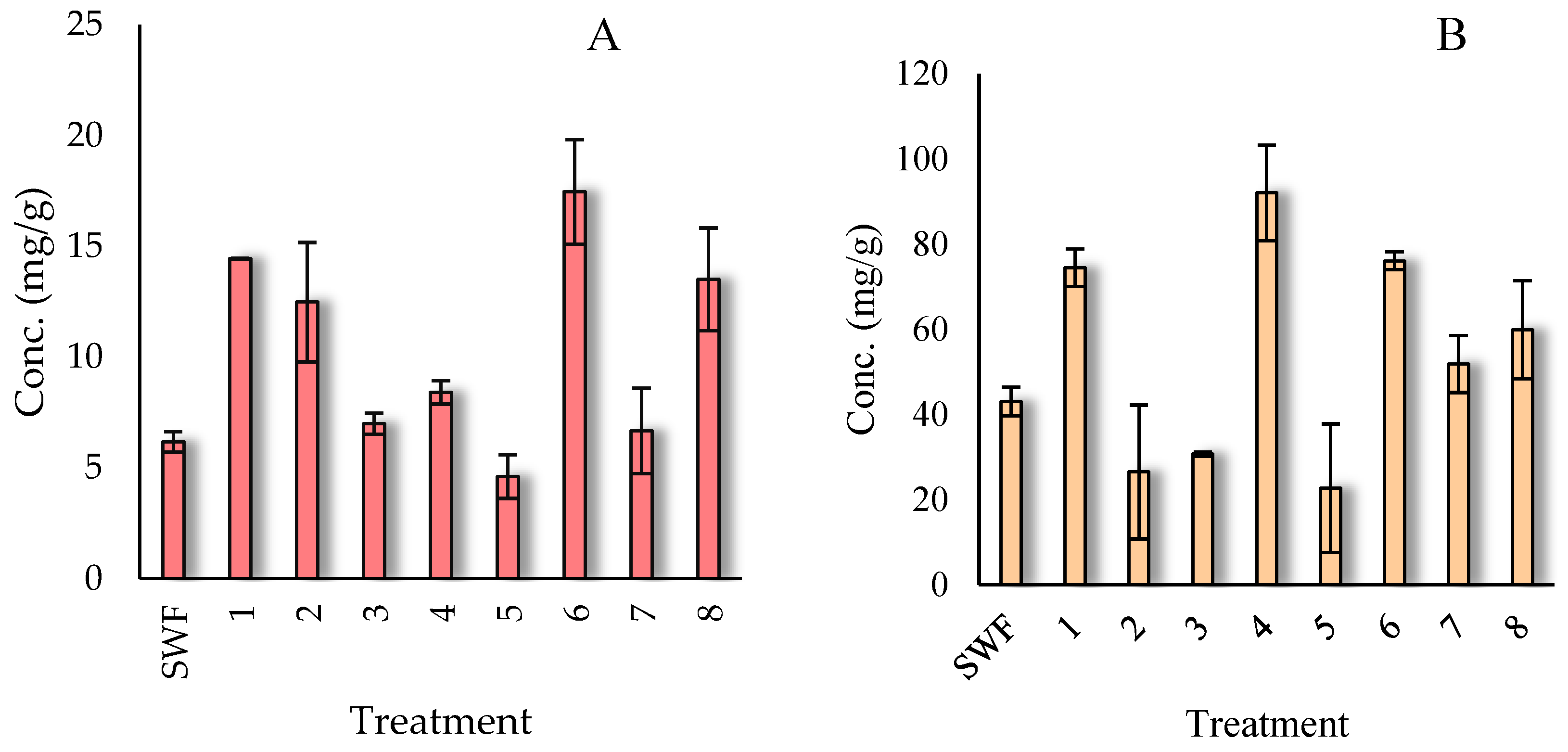

3.4. Evaluation of the SSF Conditions for the Release of HT and CT

According to the methodology used in section 2.6, 7 factors were evaluated, which were at a low level and a high level, in

Figure 3A the treatments used for the release of bioactive compounds are shown, for the

A. niger HT3 strain a fermentation time of 72 h was used, and it was treatment 6 that obtained the highest release of HT with a concentration of 17.46 ± 2.35 mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, where a temperature of 30 °C at 70% humidity was used with an inoculum of 1x10

7, with a concentration of salts of NaNO

3 (7.65 g/L), MgSO

4 (3.04 g/L), KCl (1.52 g/L), KH

2PO

4 (3.04 g/L), we can observe that in comparison to the unfermented sample (SWF), fermentation favored the release of H.T. For CT release,

A. niger strain Aa20 was used with a fermentation time of 48 h., as shown in

Figure 3B, treatment 4 favored the release of bioactive compounds with a concentration of 92.03 ± 11.23 mg/g mg/g of dry sample of pineapple peel, where a temperature of 30 ºC at 80% humidity was used with an inoculum of 1x10

6, with a concentration of salts of NaNO

3 (15.6 g/L), MgSO

4 (1.52g/L), KCl (1.52 g/L), KH

2PO

4 (3.04 g/L).

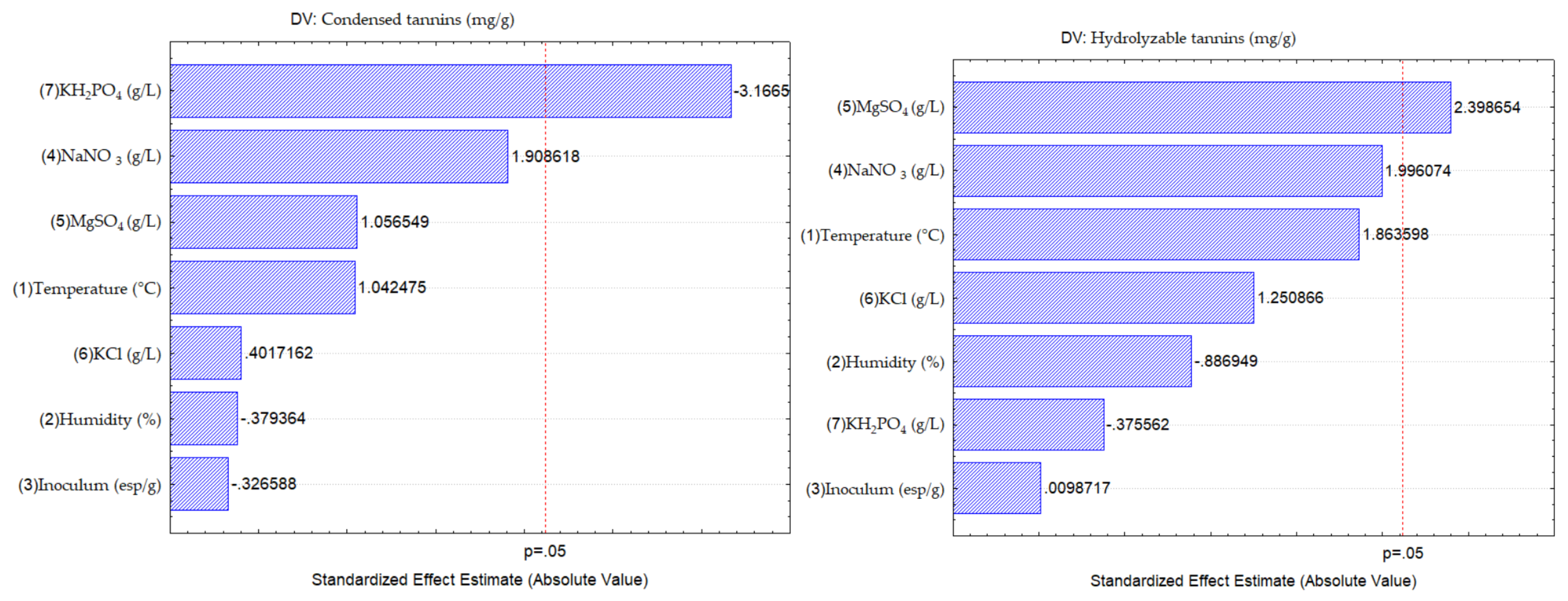

In the Pareto chart (

Figure 4) shown the influence of each of the factors observed in this work, the factors above the central line influenced the release of HT, being the MgSO

4 salt, which indicates that as the concentration of the salt is increased, they can increase the release of HT, while the other factors did not have a significant effect. While for the release of CT the KH

2PO

4 salt, had a significant effect, indicating that the lower the concentration of the salt, the higher the release of CT, can this be attributed to the cation exchange of Mg

2+ and K

+, since they can be a substitute source of the essential elements needed by the microorganism for its growth [

28].

3.5. Identification of HT and CT by HPLC-MS

The polyphenolic content (

Table 2) of the unfermented sample and of the SSF extracts of pineapple peel with

A. niger HT3 (Treatment 6) and

A. niger Aa20 (Treatment 4) was determined by HPLC-MS.; for the unfermented sample 10 main compounds were identified, for the first strain 10 main polyphenolic compounds were identified, likewise for the second strain 6 main bioactive compounds were identified, compounds of the curcuminoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, methoxycinnamic acids, flavonols, lignans, catechins and anthocyanins families were found.

3.6. Antioxidant Activity of the Fermentation Extracts

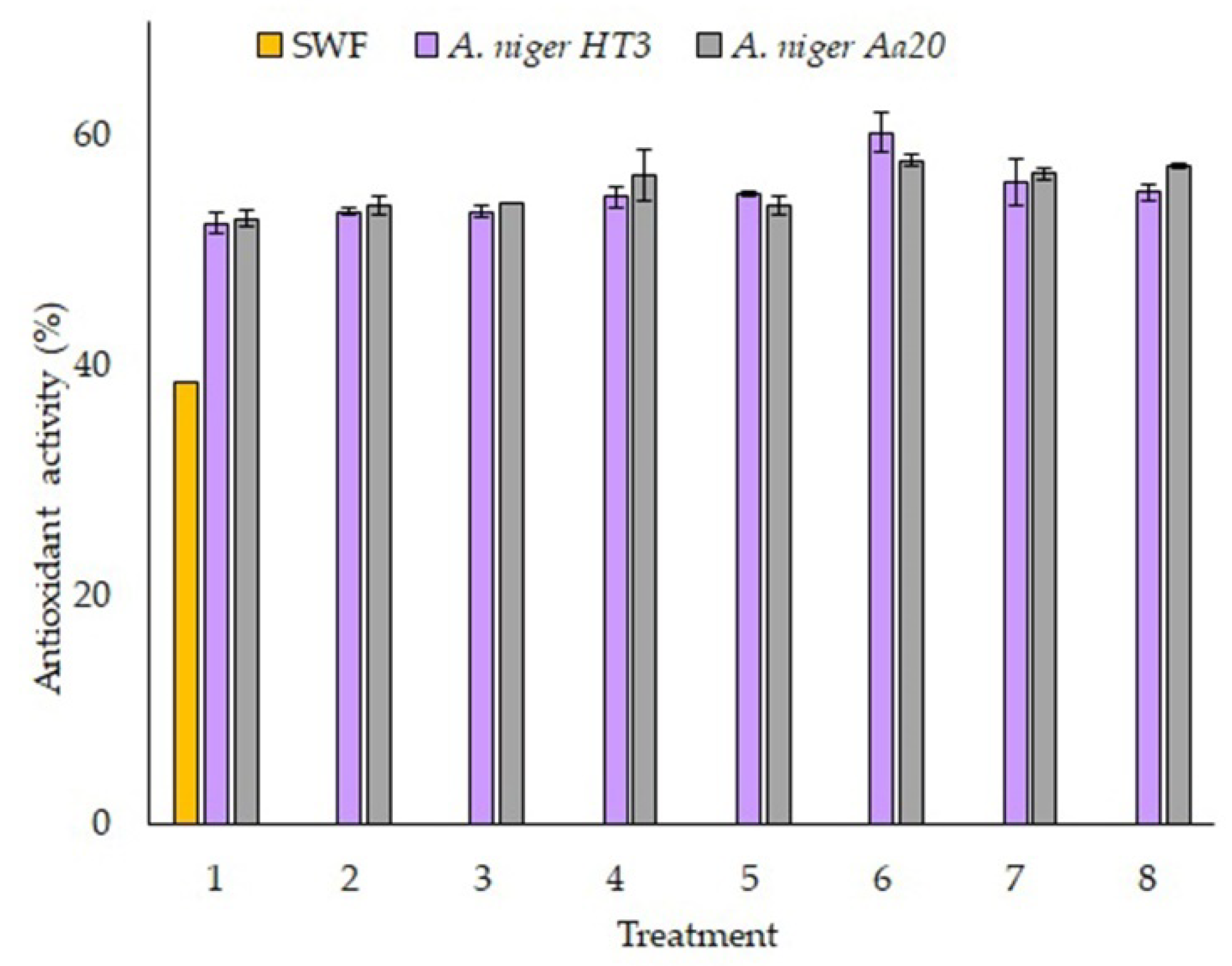

The antioxidant activity was carried out according to the methodology of section 2.8 for DPPH, in

Figure 5, the unfermented sample (SWF) and the treatments of each of the strains used are observed, the treatments presented superior values compared to SWF, which had a result of 38.61% ± 4.19, for the strain of

A. niger HT3 it is observed that there was a correlation with the release of polyphenolic compounds since treatment 6 was the one that obtained the highest percentage of inhibition (60.28% ± 1.74), for the

A. niger Aa20 strain it is observed that treatment 6 was the one that presented the highest percentage of inhibition (57.87% ± 0.46), where it is observed that there was no correlation with respect to the release of bioactive compounds.

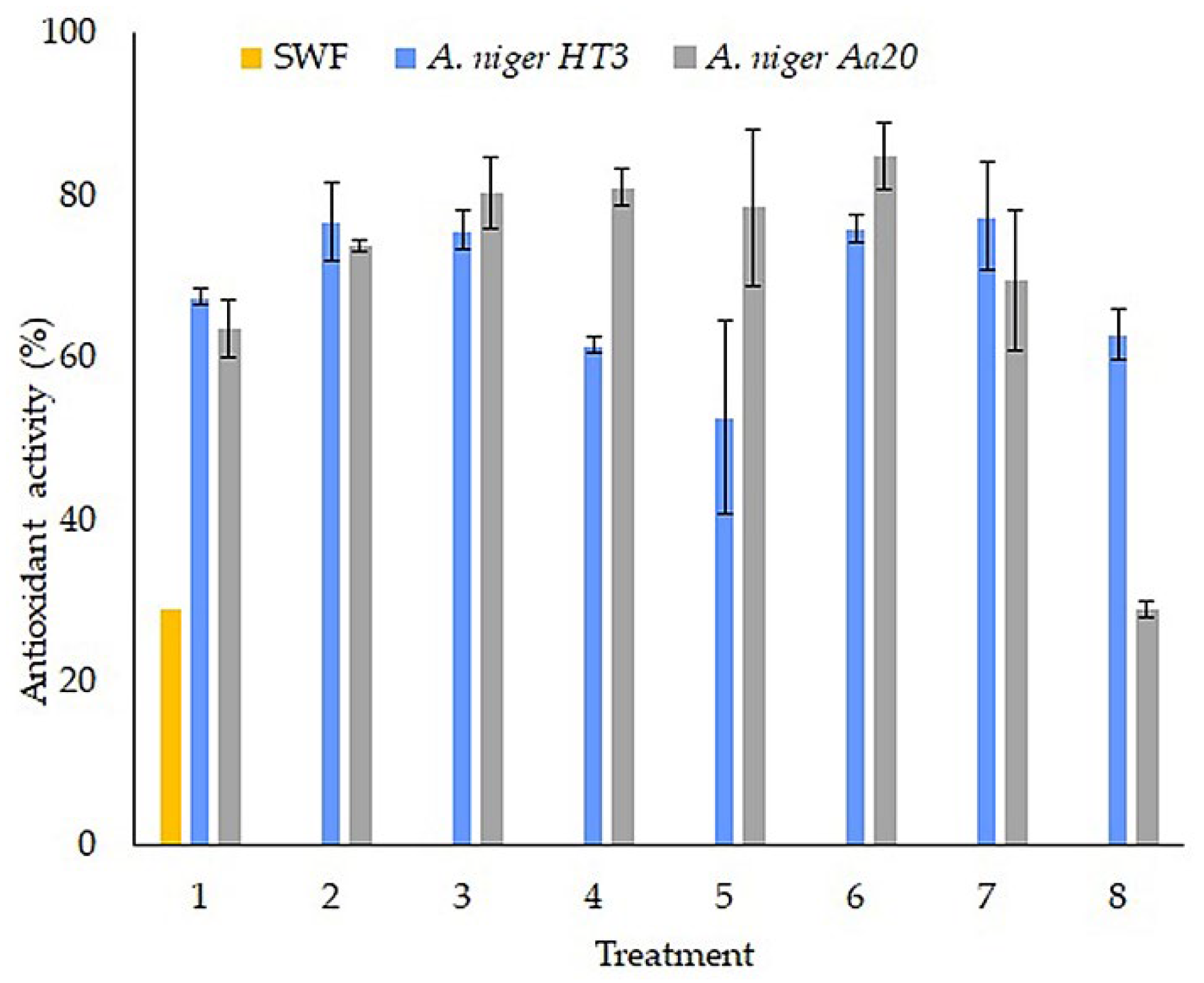

Figure 6 shows the elimination of free radicals by ABTS, for SWF an inhibition percentage of 29.18% ± 0.96 was obtained, it is observed that in comparison with the treatments the value was lower, for the strain of

A. niger HT3 treatment 7 was the one that obtained a higher percentage of inhibition (77. 38% ± 6.64), while for strain

A. niger Aa20 treatment 6 (81.41% ± 4.06), the values obtained did not correlate with the best fermentation treatments for obtaining polyphenolic compounds.

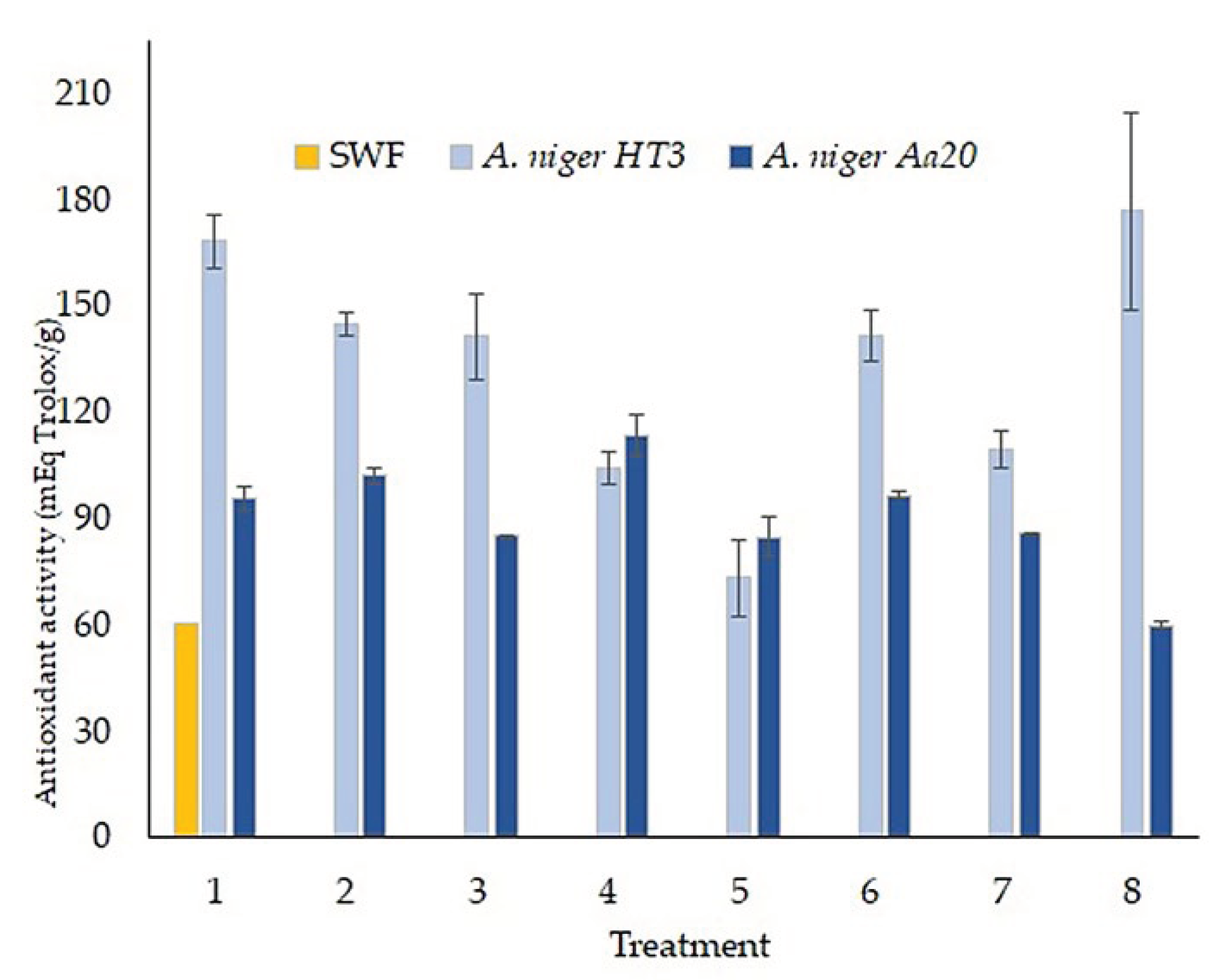

In

Figure 7, the iron reducing capacity (FRAP) is observed, where SWF obtained a result of 60.77 mEq Trolox/g ± 7.23, on the other hand, a significant increase is seen in the already fermented treatments, of

A. niger HT3 the highest concentration was from treatment 8 (176. 64 mEq Trolox/ g ± 27.80), as for the

A. niger Aa20 strain, treatment 4 was the one that obtained the highest concentration (113.39 mEq Trolox/g ± 5.99), showing a correlation with the release of bioactive compounds.

3.7. Polyphenolic Profile of the Treatments with the Highest Antioxidant Activity

Table 2 shows the compounds identified in the treatments with the highest antioxidant activity of the

A. niger HT3 strain. In treatment 6 (DPPH), 10 compounds were identified, the main compound being lariciresinol, which belongs to the group of lignans, which are considered secondary metabolites with great potential for antioxidant activity [

48], this is because the compounds identified have double bonds in the aromatic rings they possess, helping to stabilize free radicals by resonance. For treatment 7 (ABTS) 6 compounds were identified and for treatment 8 (FRAP) 5 compounds were identified, in both treatments the major compound was 3-Hydroxyphloretin 2’-O-xylosyl-glucoside, this compound belongs to the family of dihydrochalcones which are secondary metabolites, These come to present different biological activities including antioxidant activity, this is because they have unsaturated carbon bonds that help stabilize free radicals, these compounds characteristic of apples, but have not been found reported in pineapple peel. [

51,

52].

In the

A. niger Aa20 strain, in treatment 4 (FRAP), 6 compounds were identified, where it was determined that the major compound was 3-feruloylquinic acid, belonging to the group of feruloylquinic acids, which are composed of esters between a ferulic acid and a quinic acid [

51]. In treatment 6 was the one that obtained the most positive antioxidant activity according to the DPPH and ABTS methodology, 7 bioactive compounds were identified, of which caffeic acid was the major compound, it is a polyphenolic compound of the family of hydroxycinnamic acids, which are characterized by being of smaller structures and with a high antioxidant capacity due to its ability to eliminate free radicals, this is due to the presence of hydroxyl groups of the aromatic ring, since it allows stabilizing the radical that is witnessed; caffeic acid is one of the most studied compounds since it is found in different fruits, vegetables and plants [

52,

53].

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicochemical Characterization

The value of IAA was similar or higher than that reported by Polania-Rivera et al. [

20] in pineapple peel ( 5.61 g/g dry peel ± 0.03), in grape pomace (3.38 g gel/g ± 0.01) [

21], in mango seeds (3.4 - 4 g/g dry material) [

29]. In the case of PCH the value was like that reported by Buenrostro-Figueroa et al. [

28] in fig by-products (4.63%), however, it was lower than that reported with Polania-Rivera et al. [

20] (14.37% ± 0.08). According to the reported results, pineapple peel is a promising substrate for SSF.

As for moisture content, it was higher and like that reported by Selani et al. [

30] (3.77 ± 0.52), Morais et al. [

31] (8.8 ± 0.2), however, it was lower than that reported by Huang et al. [

32] (12. 04 ± 0.02 - 14.43 ± 0.06), for ash content, the value obtained in the present study was like that reported by Sanchez-Prado et al. [

33] (1.5 ± 0. 00), however, a higher ash content has been reported by Selani et al. [

30] (2.24% ± 0.58), on the other hand, Aparecida-Damasceno et al. [

34] (4.57 ± 0.04), this may be attributed to the fact that they are different varieties of pineapple and are grown in different areas of the country and the world, as well as it may also depend on the type of soil and the time of ripening of the fruit [

35]. As for fat content, the value reported in the present work is within the range already reported by different authors, Huang et al. [

32] (1.5 ± 0.1 - 2.8 ± 0.1), Akhtar-Zakaria et al. [

36] (4.87 ± 0.10), Aparecida-Damasceno et al. [

34] (1.17 ± 0.08).

As for the total sugars content, the value reported in the present study is within the reported by Diaz-Vela et al. [

37] (22.59 ± 1.99), Huang et al. [

32] (69.5 ± 0.8 - 83.4 ± 0. 1), while the results obtained for reducing sugars was lower than reported by Huang et al. [

32] (38.1 ± 2.20 - 41.4 ± 0.65), the accumulation of sugars is attributed to the time of harvest and fruit ripening [

35]. Pineapple agro-industrial residues have been found to contain several types of sugars, according to reports by Sepulveda et al. [

15] and Polania-Rivera et al. [

20] the sugars found mostly are glucose, fructose, and sucrose.

For protein content the value reported is within the values already reported by different authors Diaz-Vela et al. [

37] (0.32 ± 0.05), Selani et al. [

30] (4.71 ± 0.28), Morais et al. [

31] (7.3 ± 0.09), pineapple is low in protein, however, bromelain as well as polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase can be found in different amounts [

35]. For fiber content the value is within the previously reported by different authors, Huang et al. [

32] (7.1 ± 0.1 - 19.8 ± 0.9), Morais et al. [

31] (15.9 ± 2.4), Apareciada-Damasceno [

34] (4.92 ± 0.5).

4.2. Quantification of Tannins

According to Andrade-Damián et al. [

25] and Buenrostro-Figueroa et al. [

28], filamentous fungi are the most widely used in SSF, thanks to their ability to adapt to the substrate that presents similarities with the medium in which they grow, in addition to having a great potential for the release of bioactive compounds. The decrease of polyphenols is attributed to a decomposition or a large consumption of bioactive compounds in the exponential phase [

38].

4.3. Evaluation of the Solid-State Fermentation

According to what was reported in the present study, the results were superior to those reported by Polania-Rivera et al. [

20] where they performed a SSF process with pineapple peel, using

Rhizopus oryzae having as results for total polyphenols 83.77 mg GAE/g and for C.T. 66.5 mg QE/g, according to Correia et al. [

39] the low polyphenolic content during fermentation of pineapple residues combined with soybean meal with

Rhizopus oligosporus could be related to the fact that most of the compounds are bound to the inner membrane and only few free polyphenols are found. According to reports from different authors, Aspergillus spp. strains using the SSF biotechnological process help to release polyphenols, as they also naturally produce enzymes that degrade the cell wall and produce hydrolysis, as reported by Torres-León et al. [

29] who used SSF mango seeds with the A. niger strain GH1, where an increase in total phenolic content was obtained (984 mg GAE/100 g to 3288 mg GAE/100 g), likewise, Buenrostro-Figuero et al. [

28] using fig residues in SSF with

A. niger HT4, obtained an increase in total polyphenol content obtaining a value of 10.19 ± 0.04 mg GAE/g. Amaya-Chantaca et al. [

21] who used a SSF method with a strain of

A. niger GH1, in grape pomace observed that it is an effective method for obtaining polyphenolic compounds where they obtained a concentration for HT 2.262 g/L and for CT 3.684 g/L. Rajan et al. [

40] used the SSF process with

A. niger and

A. flavus strains on Indian black plum fruit to obtain polyphenolic compounds, obtaining favorable results as each strain obtained a significant increase from 182.42 mg GAE/100 g of the unfermented sample to 526.37 mg GAE/100 g for

A. niger strain and 685.88 mg GAE/100 g for

A. flavus strain. The results indicate that SSF is a promising biotechnological process for obtaining bioactive compounds, likewise pineapple peels were a promising substrate, and it is advisable to continue studying this type of by-product, for its use since there are not enough with the SSF process.

4.6. Activity Antioxidant

The results obtained are favorable according to Sepulveda et al. [

15] since they are within those already reported, reporting that DPPH values ranged from 27.4% ± 0.1 to 82.1% ± 1.4, while ABTS values ranged from 57.1 ± 0.2 to 95.0% ± 0.1, on the other hand, Polania et al. [

42] used pineapple waste fermented from

Rhizopus oryzae to subsequently subject them to ultrasonic treatment, according to the results obtained from fermented extracts (61.46 ± 1.05 and 77.39% ± 1.18, DPPH and ABTS respectively) and combined fermentation with ultrasound (63.53% ± 2.02 and 80.06% ± 1.02, DPPH and ABTS respectively); they are similar to those obtained in the present study. On the other hand, Dulf et al. [

43], obtained methanol extracts of peach pomace from SSF using

A. niger and

R. oligosporus, although the antioxidant activity did not correlate with the bioactive compounds, positive results were obtained for inhibition by DPPH. While Torres-Leon et al. [

29] found a correlation of polyphenols obtained from mango seed, subjected to a SSF process with

A. niger GH1 with their antioxidant activity, this is attributed to the fact that the fermentation process increases the antioxidant activity of bioactive compounds. On the other hand, Paz-Artega et al. [

38] using SSF with

A. niger GH1 in pineapple peels and core saw a positive correlation with respect to the release of polyphenols and antioxidant activity by DPPH since there was an increase of 25%.

According to results obtained are similar or even superior to those reported by Chiet et al. [

44] they extracted the polyphenolic content of three different pineapple cultivars, during 2 hours with 80% methanol with a shaking of 200 rpm, where they obtained results for Josapine (118.29 µg ascorbic acid equivalents/ g ± 9.20), Morris (85.23 ± 2.65) and Sarawak (73.92 ± 5.10). Brito et al. [

45] obtained methanol and ethanol extracts by maceration from pineapple crown, where the extracts showed positive antioxidant effect using the FRAP method. Larios-Cruz et al. [

46] recovered bioactive compounds from grapefruit waste by SSF using

A. niger GH1, the compounds obtained were subjected to FRAP antioxidant activity, obtaining lower values (14.43 mg/g) than those reported in the present study.

Antioxidant activities are due to the fact that they have a protective activity against oxidation compounds, such is the case of polyphenols that help to capture free radicals that are absorbed by humans, although antioxidant activity is not correlated with the release of polyphenolic compounds, since it may be due to the fact that there may be interferences with the techniques used, in addition to the fact that polyphenols act in different ways and not all of them may have the same biological activity [

15]. However, it has been proven that by using the SSF method a large amount of bioactive compounds are released and with it a high antioxidant activity, this is attributed to the fact that a microbial hydrolysis is generated that helps the release of these bioactive that are bound to the plant matrix [

47].

4.5. Identification of Bioactive Compounds by HPLC-MS

According to Banerjee et al. [

41] different bioactive compounds have been found in pineapple waste, of which phenolic acids, flavonoids, catechin, gallic acid, and ferulic acid stand out. Polania-Rivera et al. [

20] identified 8 compounds by the SSF method using

Rhyzopus oryzae, these being gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, catechin, caffeic acid, epicatechin, coumaric acid, scopoletin and quercetin. Paz-Arteaga et al. [

38] using SSF with

A. niger GH1 identified 15 major compounds which were caffeoyl hexoside, 5-caffeoylquinic acid, spinacetin 3-

O-glucosyl-(1- > 6)-[apiosyl(1- >2)]-glucoside,

p-coumaric acid ethy ester, banzoic acid,

p-coumaroyl tyrosine,

p-coumaryl alcohol hexoside, 4-vinylphenol,

p-coumaroyl glycolic acid, feruloyl aldarate, psoralen, caffeic acid 4-

O-glucpside,

p-coumaroyl hexoside, (+)-gallocatechin and gallagyl-hexoside.

Among the compounds identified in previous works, as well as in the present study, similarities have been found in the families such as the flavonoid family, hydroxycinnamic acid, catequins hydrolyzable tannins, however, using different strains of filamentous fungi, it was demonstrated that they release different compounds, This can be attributed to the fact that the strains used have different metabolisms, they can use different enzymes for the biodegradation process of the compounds or the location where the pineapple was grown, since they can be in different types of soils, it can also be attributed to the ripening of the fruit. It has also been proven that the bioactive compounds contained in pineapple peel are beneficial to human health.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained in the present study show that solid state fermentation using Aspergillus niger spp. strains and pineapple peels as substrate are effective for a higher release of bioactive compounds and thus a favorable antioxidant activity. A. niger HT3 strain assisted in the release of hydrolyzable tannins, while A. niger Aa20 strain assisted in the release of condensed tannins. HPLC analysis aided in the identification of 33 bioactive compounds of which 4 were major compounds, 3-Feruloylquinic acid, caffeic acid, lariciresinol and 3-hydroxyphloretin 2’-O-xylosyl-glucoside, which have been shown to have diverse biological activities that aid human health. The SSF process using pineapple peels as substrate was shown to be a promising alternative for the release of bioactive compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.C.R. and L.S.T.; methodology, ADC.R.; software, L.S.T.; validation, A.D.C.., L.S.T. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, A.D.C.R and L.S.T.; investigation, A.D.C.R.; resources, CONAHCYT., J.A.A.V., and L.S.T; data curation, A.D.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.C.R.; writing—review and editing, A.D.C.R., J.A.A.V., M.D.D.M., L.L.H, and L.S.T.; visualization, A.D.C.R.; supervision, L.S.T.; project administration, CONAHCYT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

A.D. Casas Rodríguez thanks the CONAHCYT for his postgraduate scholarship (No. 1150329). The authors thank the Autonomous University of Coahuila.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Teshome, E.; Teka, T.A.; Nandasiri, R.; Rout, J.R.; Harouna, D.V.; Astatkie, T.; Urugo, M.M. Fruit By-Products and Their Industrial Applications for Nutritional Benefits and Health Promotion: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, C. The effects of regions and the wine aging periods on the condensed tannin profiles and the astringency perceptions of Cabernet Sauvignon wines. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, N.; Faruk, O.; Ashaduzzaman; Dungani, R. Review on tannins: Extraction processes, applications and possibilities. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.P. Tannin degradation by phytopathogen's tannase: A Plant's defense perspective. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muanda, F.N.; Dicko, A.; Soulimani, R. Assessment of polyphenolic compounds, in vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammation properties of Securidaca longepedunculata root barks. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2010, 333, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. A. Sanchez-Hernandez, S. M. A. Sanchez-Hernandez, S. Huja-Mendoza, R. Acevedo-Gomez, Producción de piña Cayena Lisa y MD2 (Ananas comosus L.) en condiciones de Loma Bonita, Oaxaca, In: E. Figueroa, L. Godinez, F. Pérez (Eds.), Ciencias de la Biología y Agronomía, Handbook T-I, ©ECOFRAN, Texcoco de Mora, México, 2015, pp. 100-110.

- Prado, K.S.; Spinacé, M.A. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from pineapple crown waste and their potential uses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 122, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casabar, J.T.; Ramaraj, R.; Tipnee, S.; Unpaprom, Y. Enhancement of hydrolysis with Trichoderma harzianum for bioethanol production of sonicated pineapple fruit peel. Fuel 2020, 279, 118437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani, D.C.; Nole, K.S.O.; Montoya, E.E.C.; Huiza, D.A.M.; Alta, R.Y.P.; Vitorino, H.A. Minimizing Organic Waste Generated by Pineapple Crown: A Simple Process to Obtain Cellulose for the Preparation of Recyclable Containers. Recycling 2020, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidin, N.A.S.; Abdullah, S.; Nor, F.H.M.; Hadibarata, T. Isolation and identification of natural green and yellow pigments from pineapple pulp and peel. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 63, S406–S410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shen, P.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Liang, R.; Yan, N.; Chen, J. Major Polyphenolics in Pineapple Peels and their Antioxidant Interactions. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.-M. Sun, X.-M. G.-M. Sun, X.-M. Zhang, A. Soler, y P. Marie-Alphonsine, Nutritional composition of pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.), in: M.S.J. Simmonds, V.R. Preedy (Eds.). Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars, Elsevier, USA, 2016, pp. 609-637. [CrossRef]

- Elss, S.; Preston, C.; Hertzig, C.; Heckel, F.; Richling, E.; Schreier, P. Aroma profiles of pineapple fruit (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.) and pineapple products. LWT 2005, 38, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampar, G.G.; Zampar, I.C.; Souza, S.B.d.S.d.; da Silva, C.; Barros, B.C.B. Effect of solvent mixtures on the ultrasound-assisted extraction of compounds from pineapple by-product. Food Biosci. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L.; Romaní, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J. Valorization of pineapple waste for the extraction of bioactive compounds and glycosides using autohydrolysis. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 47, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Paz, J.E.; Aguilar-Zárate, P.; Veana, F.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B. Impacto de las tecnologías de extracción verdes para la obtención de compuestos bioactivos de los residuos de frutos cítricos. 2020, 23. [CrossRef]

- Šelo, G.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Martinović, J.; Perković, G.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Bioconversion of Grape Pomace with Rhizopus oryzae under Solid-State Conditions: Changes in the Chemical Composition and Profile of Phenolic Compounds. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, C.L.; de Lima, F.S.; Guelfi, M.F.G.; Fernandes, M.d.S.; Georgetti, S.R.; Ida, E.I. Parameters of the fermentation of soybean flour by Monascus purpureus or Aspergillus oryzae on the production of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2018, 271, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.; Ascacio-Valdés, A.; Sepúlveda, L.; De la Cruz, R.; Prado-Barragán, A.; Aguilar-González, M.A.; Rodríguez, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Potential use of different agroindustrial by-products as supports for fungal ellagitannase production under solid-state fermentation. Food Bioprod. Process. 2013, 92, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.M.P.; Toro, C.R.; Londoño, L.; Bolivar, G.; Ascacio, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N. Bioprocessing of pineapple waste biomass for sustainable production of bioactive compounds with high antioxidant activity. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 17, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Chantaca, D.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Iliná, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Sepúlveda-Torre, L.; A Ascacio-Vadlés, J.; Chávez-González, M.L. Comparative extraction study of grape pomace bioactive compounds by submerged and solid-state fermentation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 97, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmile-Gordon, M.; Armenise, E.; White, R.; Hirsch, P.; Goulding, K. A comparison of two colorimetric assays, based upon Lowry and Bradford techniques, to estimate total protein in soil extracts. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 67, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Púa, A.L.; Barreto, G.E.; Zuleta, J.L.; Herrera, O.D. Análisis de Nutrientes de la Raíz de la Malanga (Colocasia esculenta Schott) en el Trópico Seco de Colombia. 2019, 30, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Hernández, P.; Ruelas-Chacón, X.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Flores-Naveda, A.; Sepúlveda-Torre, L. Solid-State Fermentation of Sorghum by Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus niger: Effects on Tannin Content, Phenolic Profile, and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2022, 11, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Damián, M.F.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Wong-Paz, J.E.; Veana-Hernández, F.; Reyes-Luna, C.; Aguilar-Zárate, P. Estudio exploratorio de la extracción de pigmentos de Curcuma longa L. por fermentación en estado sólido utilizando cinco cepas fúngicas. Mex. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.E.; Nagai, A.; Torres, P.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Salatino, A. Contents of tannins of cultivars of sorghum cultivated in Brazil, as determined by four quantification methods. Food Chem. 2020, 337, 127970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md. Nazmul Islam, Kusay Faisal Al-tabatabaie, Md. Ahasan Habib, Sheikh Sharif Iqbal, Khurram Karim Qureshi and Eid M. Al-Mutairi, Design of a Hollow-Core Photonic Crystal Fiber Based Edible Oil Sensor, Crystals 2022, 12, 1362. [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.; Velázquez, M.; Flores-Ortega, O.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Aguilar, C.; Prado-Barragán, L. Solid state fermentation of fig ( Ficus carica L.) by-products using fungi to obtain phenolic compounds with antioxidant activity and qualitative evaluation of phenolics obtained. Process. Biochem. 2017, 62, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.; Serna-Cock, L.; Correia, M.T.d.S.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Solid-state fermentation with Aspergillus niger to enhance the phenolic contents and antioxidative activity of Mexican mango seed: A promising source of natural antioxidants. LWT 2019, 112, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selani, M.M.; Brazaca, S.G.C.; Dias, C.T.d.S.; Ratnayake, W.S.; Flores, R.A.; Bianchini, A. Characterisation and potential application of pineapple pomace in an extruded product for fibre enhancement. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, D.R.; Rotta, E.M.; Sargi, S.C.; Bonafe, E.G.; Suzuki, R.M.; Souza, N.E.; Matsushita, M.; Visentainer, J.V. Proximate Composition, Mineral Contents and Fatty Acid Composition of the Different Parts and Dried Peels of Tropical Fruits Cultivated in Brazil. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.W.; Lin, I.J.; Liu, Y.; Mau, J.L. Composition, enzyme and antioxidant activities of pineapple. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, M.; Pardo, S.; Ramos Cassellis, E.; Escobedo, R.M.; García, E.J. Chemical Characterisation of the Industrial Residues of the Pineapple (Ananas comosus). J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 2014, 3, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparecida Damasceno, K.; Alvarenga Gonçalves, C.A.; Dos Santos Pereira, G.; Lacerda Costa, L.; Bastianello Cam-pagnol, P.C.; Leal De Almeida, P.; Arantes-Pereira, L. Development of Cereal Bars Containing Pineapple Peel Flour (Ananas comosus L. Merril). J. Food Qual. 2016, 39, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z. Othman, J. Siriphanich, Pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merr.), in: Elhadi M. Yahia (Eds.). Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits, Elsevier, 2011, pp. 194-218e.

- Zakaria, N.A.; Rahman, R.A.; Zaidel, D.N.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Jusoh, M. Microwave-assisted extraction of pectin from pineapple peel. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2021, 17, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vela, J.; Totosaus, A.; Cruz-Guerrero, A.E.; de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M. In vitroevaluation of the fermentation of added-value agroindustrial by-products: cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indicaL.) peel and pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel as functional ingredients. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Arteaga, S.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Cadena-Chamorro, E.; Serna-Cock, L.; Aguilar-González, M.A.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Torres-León, C. Bioprocessing of pineapple waste for sustainable production of bioactive compounds using solid-state fermentation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.T.; McCue, P.; Magalhães, M.M.; Macêdo, G.R.; Shetty, K. Production of phenolic antioxidants by the solid-state bioconversion of pineapple waste mixed with soy flour using Rhizopus oligosporus. Process. Biochem. 2004, 39, 2167–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, M.; Andrade, J.K.S.; Barros, R.G.C.; Guedes, T.J.F.L.; Narain, N. Enhancement of polyphenolics and antioxidant activities of jambolan (Syzygium cumini) fruit pulp using solid state fermentation by Aspergillus niger and A. flavus. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ranganathan, V.; Patti, A.; Arora, A. Valorisation of pineapple wastes for food and therapeutic applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanía, A.M.; Londoño, L.; Ramírez, C.; Bolívar, G. Influence of Ultrasound Application in Fermented Pineapple Peel on Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity. Fermentation 2022, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C.; Dulf, E.-H.; Pintea, A. Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, lipids and antioxidant potential of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) pomace fermented by two filamentous fungal strains in solid state system. Chem. Central J. 2017, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiet, C.H.; Zulkifli, R.M.; Hidayat, T.; Yaakob, H. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity analysis of Malaysian pineapple cultivars. 4TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MATHEMATICS AND NATURAL SCIENCES (ICMNS 2012): Science for Health, Food and Sustainable Energy. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Brito, T.; Lima, L.R.; Santos, M.B.; Moreira, R.A.; Cameron, L.; Fai, A.C.; Ferreira, M.S. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, volatile and phenolic profiles of cabbage-stalk and pineapple-crown flour revealed by GC-MS and UPLC-MSE. Food Chem. 2020, 339, 127882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-Cruz, R.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.; Prado-Barragán, A.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Montañez, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Valorization of Grapefruit By-Products as Solid Support for Solid-State Fermentation to Produce Antioxidant Bioactive Extracts. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2019, 10, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, E.; Ozkan, G.; Lu, B.; Capanoglu, E. Effects of Fermentation Process on the Antioxidant Capacity of Fruit Byproducts. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 4543–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patyra, A.; Kołtun-Jasion, M.; Jakubiak, O.; Kiss, A.K. Extraction Techniques and Analytical Methods for Isolation and Characterization of Lignans. Plants 2022, 11, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stompor, M.; Broda, D.; Bajek-Bil, A. Dihydrochalcones: Methods of Acquisition and Pharmacological Properties—A First Systematic Review. Molecules 2019, 24, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Zengin, G.; Ak, G.; Saber, F.R.; Montesano, D.; Lucini, L. The UHPLC-QTOF-MS Phenolic Profiling and Activity of Cydonia oblonga Mill. Reveals a Promising Nutraceutical Potential. Foods 2021, 10, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Wada, R.; Muguruma, H.; Osakabe, N. Analysis of Chlorogenic Acids in Coffee with a Multi-walled Carbon Nanotube Electrode. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, N.N.M.A.; Ahmad, F.; Teoh, S.L.; Yahaya, M.F. Caffeic Acid on Metabolic Syndrome: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birková, A. Caffeic acid: a brief overview of its presence, metabolism, and bioactivity. Bioact. Compd. Heal. Dis. 2020, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).