1. Introduction

Bacterial cellulose (BC) is an emerging biopolymer with unique properties such as high purity, crystallinity, and mechanical strength, making it superior to plant-derived cellulose for various applications [

1,

2]. However, scaling industrial BC manufacturing remains restricted by the high costs of conventional culture media [

2]. Solid-state fermentation (SSF) has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance the nutritional potential of carbohydrate-rich waste streams, offering advantages such as reduced reactor volume, lower energy requirements, and simplified downstream processing [

3].

Rice bran and cereal dust, abundant waste of grain processing, represent promising yet underutilised substrates for BC production. Annually, rice bran production exceeds 29 million tonnes globally, while cereal dust constitutes approximately 2-3% of grain weight during milling [

4,

5]. These materials are rich in complex carbohydrates, proteins, and essential nutrients, potentially supporting microbial growth and metabolism [

6,

7]. Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using rice bran as an alternative nitrogen source for BC production, with yields increasing up to 2.4-fold compared to standard medium [

5]. However, the fibrous architecture of these residues can limit nutrient accessibility without preprocessing.

SSF has emerged as an optimal bioprocessing strategy to enhance the nutritional and functional potential of carbohydrate-rich waste streams from cereal milling and rice production [

8]. SSF offers advantages such as being suitable for tiny effluent amounts and simple substrates, being cost-effective, and having no extra consideration for standard procedure control. This technique is usually applied to agro-industrial waste resources [

9]. SSF utilises filamentous fungi perfectly adapted to solid substrates in nature to break down complex matrix polysaccharides through secreted enzyme cocktails into readily assimilable sugars, proteins, and metabolites.

Aspergillus niger,

A. oryzae,

A. parasiticus,

Acremonium crysogenum, and

Rhizopus oryzae, are some of the microorganisms which have been explored for SSF of rice bran, wheat bran and other agricultural wastes and by-products [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Literature confirms SSF significantly increased the protein accessibility of rice bran by unlocking nutrients entrapped within fibrillar networks using natural enzymatic biocatalysts [

14].

SSF is particularly advantageous for bioprocessing agro-industrial waste streams, as it operates with low moisture content (typically <70%), making it well-suited for materials with low water activity, such as lignocellulosic biomass. The technique offers several economic and sustainability benefits, including reduced reactor volume, lower energy requirements for aeration and mixing, and simplified downstream processing compared to submerged fermentation. SSF also allows for the direct use of unfractionated solid substrates, minimising the need for costly pretreatment steps. Moreover, the low water activity in SSF helps prevent bacterial contamination, allowing for a semi-sterile process without the need for strict aseptic conditions. These advantages have made SSF an attractive bioprocessing strategy for the valorisation of agro-industrial wastes into value-added products like enzymes, organic acids, and biofuels.

To address the challenge of producing BC sustainably and at a reduced cost, this study aimed to develop an SSF-based bioprocess for valorising rice bran and cereal dust into BC using three fungal strains: Rhizopus oryzae, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Rhizopus oligosporus. The specific objectives were to: (a) assess the impact of SSF pretreatment on nutrient bioavailability and BC production potential; (b) compare the yield and physicochemical properties of BC produced from untreated and SSF-treated waste streams; and (c) characterise the resulting BC materials using a suite of analytical techniques. By addressing these objectives, this study provides a proof-of-concept for sustainable valorisation of agro-food wastes into high-value BC biomaterials, potentially paving the way for cost-effective and eco-friendly BC production processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and Preparation of Inoculum

A novel

Novacetimonas sp., an acetic acid bacterium isolated from apple cider vinegar was used in this study [

15]. The isolation process involved screening multiple fermented liquid samples by subculturing in Hestrin-Schramm (HS) medium to test for consistent bacterial cellulose pellicle formation. This isolate from apple cider vinegar demonstrated stable BC production in repeated subcultures. Initial characterisation through biochemical testing revealed that this isolate belongs to the acetic acid bacteria group. Further identification was performed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which identified the isolate belongs to the

Novacetomonas genus with 99% similarity to known sequences. The 16S rRNA sequence was submitted to NCBI with the accession number PP421219. Gram staining and electron microscopy illustrated the rod-shaped morphology characteristic of this species [

15]. Growth profile analysis exhibited an extended exponential phase, faster cell growth in agitated cultures, and higher BC production in static cultures [

15]. This isolate represents a promising candidate for BC production due to its robust growth and cellulose-synthesizing capabilities. Comparative genomic analyses are currently ongoing to identify this novel isolate down to species level and to characterise its BC biosynthetic and secretion pathways.

The isolate was grown in HS culture medium, for two weeks at 28°C by static cultivation method to prepare the inoculum. After the incubation period, the flask used to prepare inoculum was shaken vigorously each time to let the bacterial cells detach from the BC pellicle and mix with the HS inoculate culture medium. This cell suspension, adjusted to 0.1 OD, served as the inoculum. A 10% (v/v) inoculum concentration was used for all experiments.

2.2. Waste Materials used For the Reformulation of Bacterial Cellulose Media

Stabilised rice bran, which was exposed to heat to deactivate lipase enzyme while preserving its nutritional value was sourced from SunRice, Yanco, New South Wales, Australia, and the cereal dust was sourced from Rex James Stockfeed Ltd, Nathalia, Victoria, Australia. Proximate analyses of these cereal waste substrates were conducted to estimate the amount of carbohydrate and protein for media reformulation (Supplementary Table 1).

2.3. Reformulation of HS Culture Medium using Agro Wastes for BC Production

Based on proximate analysis, the standard HS bacterial cellulose production medium was reformulated by substituting key carbon and nitrogen sources. The reformulated media composition is presented in Supplementary Table 2.

2.4. Solid-State Fermentation of Rice Bran (RB) and Cereal Dust (CD)

Solid-state fermentation of rice bran and cereal dust were carried out using three fungal species:

Rhizopus oryzae (RO) from NATURITAS, Barcelona, Spain;

Pleurotus osteratus (PO) from Urban Spores, Queensland, Australia; and

Rhizopus oligosporus (T) from Nourish me Organics, Victoria, Australia. The pre-treatment of RB and CD using SSF was carried out in 5L Erlenmeyer flasks for a better surface area and controlled aeration during the treatment. For each substrate, 200g of material was evenly distributed at the bottom of the flask. The samples were moistened with distilled water prior to sterilisation. Each flask was inoculated with a fungal spore suspension containing 4.0 x 10

6 spores medium [

16]. The flasks were covered with sterile gauze to allow ventilation and incubated at 25°C for 14 days. After incubation, the fermented samples were sterilised at 121°C for 16 minutes to decontaminate the fungal spores. The treated substrates were then oven-dried at 60°C for 48 hours until moisture-free, ground into a fine powder, and used as culture media components for BC production [

9].

2.5. BC Production from Treated and Untreated Waste Substrates

Small-scale and large-scale experiments compared BC production using treated and untreated rice bran (RB) and cereal dust (CD) against standard HS medium. For small-scale trials, 50 ml tubes contained waste media formulations substituting HS carbon and nitrogen sources. SSF treated and untreated substrates were used in equal amounts. Media were sterilised, adjusted to pH 6.2, and inoculated with

N. entanii (0.1 OD). Cultures were incubated statically at 28°C for 14 days. BC pellicles were harvested, purified, and weighed after oven-drying or lyophilisation. On the other hand, large-scale production used 1L Schott bottles to increase surface area, following the same protocol. This approach was based on studies showing BC yield is proportional to vessel surface area [

17,

18]. Inoculum size, pH, temperature, incubation period, and processing methods remained consistent with small-scale trials.

2.6. Characterisation of BC produced from SSF-Treated Substrates

Analytical techniques such Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) were used to study and evaluate the comparable properties of BC produced from SSF-treated waste media. The physico-chemical characterisations of these BC films were compared to the BC films generated from HS medium taken as control, nata de coco as a commercially available BC control, and untreated BC samples (RB and CD). The comparable properties of these BC films generated from different waste media formulations were also studied based on two drying techniques: oven-drying (OD) in a hot air oven at 60°C for 8 hours and freeze-drying (FD) by lyophilising the samples at -80°C for 6 hours and moving them to freeze dryer at a condenser temperature of -120°C and vacuum pressure of 0.5 mbar until the weight remains constant. Following are the methods used for the preparation and analysis of BC films for each characterisation performed:

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

A field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Supra 40 VP) was used to observe the structural morphology of the ultrafine fibre network. BC pellicles obtained after the oven and freeze-drying were cut into small pieces and coated with a thin layer of gold onto the sample by a sputter coating device for 15 seconds, followed by the attachment of double-sided conducting carbon tape to the slide for better conductivity. The coated samples were viewed at different magnifications. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscope (EDS) (Oxford Inca Energy 200) was also performed simultaneously on the same samples coated for SEM analysis.

2.8. Fourier-Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The infrared spectra of BC were recorded using FTIR-VERTEX 70 Burker. BC samples were prepared as films to analyse performing over the range of 400-4000 cm-1 with a resolution of 16 cm-1 and averaged over 200 scans. The spectrum line was baseline-corrected and optimised on the generated IR spectra using Quasar 1.7.0 and Origin 2023 software to compare and study the spectra of BC film samples from different reformulated media and drying methods.

2.9. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Bacterial cellulose crystal structure was analysed using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance) 5-80, 0.02, 0.5 s, 0 rpm, 10x10 mm variable slit, automatic air scatter (32min). The oven and freeze-dried samples of BC were prepared as thin and flat layers using glass slides and mounted on the sample stage. The samples were scanned at the rate of 0.5 s per step. The X-ray diffractogram was analysed and processed using Origin 2023 Peak Analyser Software.

The crystallinity index (CI) was calculated from the obtained diffractogram using the following equation [

19]:

The I200 represents the highest intensity of the 2θ peak (200), which is around 22.5°, and IAM represents the intensity of the peak situated between (110) and (200) peaks, that is 18°.

2.10. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The analysis of phase transitions and decomposition behaviours of BC films were performed using Mettler Toledo TGA analyser. Around 20-30 mg of finely cut dried BC samples were used. The sample’s weight was continuously monitored while subjected to a controlled temperature increase from 30°C to 800°C.

3. Results

This study demonstrated the successful production of bacterial cellulose (BC) from rice bran and cereal dust pretreated by SSF using R. oryzae, P. osteratus and R. oligosporus. SSF pretreatment enhanced BC yield compared to untreated substrates, with rice bran fermented by R. oligosporus producing the highest yield. The BC produced from SSF-treated substrates showed comparable nanostructure to that produced in standard HS medium and commercial nata de coco. Both the choice of fungal strain for SSF and the drying method (oven-drying vs. freeze-drying) significantly influenced BC nanostructure, fibre diameter, and morphology. The physicochemical properties of BC, including crystallinity, thermal stability, and surface chemistry, were affected by the substrate type and processing conditions. Lastly, cost analysis revealed that using SSF-treated agro-food wastes could reduce BC media costs by up to 90% compared to the standard HS medium. These results highlight the potential of SSF-treated agro-food wastes as sustainable and cost-effective substrates for BC production. The following subsections will discuss these findings in detail, including the characterisation of BC properties through various analytical techniques.

3.1. Solid-State Fermentation of Rice Bran and Cereal Dust

After 14 days of SSF, extensive fungal growth was observed on all samples (Supplementary Figure 1), with all three strains effectively colonising the rice bran (RB) and cereal dust (CD) substrates. Visual inspection indicated successful bioconversion of the substrates by the fungal strains, as evidenced by the visible mycelial growth and changes in substrate texture. It must be noted that the SSF process was completed without the addition of harsh chemicals or energy-intensive treatments, using only the native enzyme systems of the fungal strains to modify the substrates.

3.2. Media Substitution using SSF-Treated Rice Bran and Cereal Dust

Substituting the carbon and nitrogen sources in the HS medium with SSF-treated rice bran (RB) and cereal dust (CD) significantly enhanced bacterial cellulose (BC) yields compared to untreated substrates. This was demonstrated through both small-scale and large-scale experiments. Small-scale screening revealed that rice bran fermented with Rhizopus oryzae (RB-RO) yielded the highest BC (0.5 g/L), matching the conventional HS medium and surpassing untreated RB (Supplementary Figure 2). This improvement can be attributed to the action of fungal lignocellulolytic enzymes and proteases, which increased the bioavailability of nutrients. Large-scale experiments in 1L Schott bottles confirmed these findings, with rice bran fermented with

Rhizopus oligosporus (RB-T) yielding the highest BC (1.5 ± 0.6 g/L dry weight), surpassing even the HS medium (

Figure 1). This scale-up demonstrated the potential for industrial-scale production using SSF-treated agricultural wastes.

The superior performance in larger vessels aligns with previous studies reporting the influence of surface area to volume ratio on BC yield [

18,

20,

21,

22]. The wet weight BC yields obtained are comparable to or higher than those reported for other pre-treated agro-wastes, such as rice bark (2.4 g/L), oat hulls (2.2 g/L), wheat straw (8.3 g/L), and potato peel waste (4.7 g/L) [

7,

23]. These findings underscore the promise of combining SSF with the biosynthetic capabilities of

N. entanii for cost-effective and sustainable BC production from abundant waste streams.

3.3. Comparative Analyses of the BC produced from SSF-Treated Rice Bran and Cereal Dust

3.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis revealed distinct differences in BC nanostructure based on both the substrate source and drying method.

Figure 2 compares the nanostructure of BC produced in HS medium with commercially available nata de coco, while

Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 3 show BC derived from SSF-treated cereal dust and rice bran, respectively.

Across all samples, freeze-dried (FD) BC exhibited a more open, porous structure with visible spaces between fibre bundles, while oven-dried (OD) samples displayed a dense, interconnected network of nanofibers (

Figure 2). This trend was consistent for BC produced from HS medium, nata de coco, and SSF-treated agricultural wastes. The effect of substrate source on BC nanostructure was evident in the comparison of cereal dust and rice bran-derived BC (

Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 3). BC from CD fermented with

Pleurotus osteratus showed a particularly dense and interconnected network, similar to that observed by Mohammadkazemi et al. (2015) in BC produced from mannitol and sucrose media [

24]. Samples pretreated with

Rhizopus oryzae and

Rhizopus oligosporus exhibited slightly more varied fibre arrangements.

Fibre diameter analysis (

Figure 4 for cereal dust and Supplementary Figure 4 for rice bran) revealed that OD samples consistently produced smaller average fibre diameters (around 30 nm) compared to FD samples (40-50 nm for rice bran, 30-80 nm for cereal dust). This trend aligns with observations by Du et al. (2018), confirming the influence of drying methods on BC nanostructure across various production conditions [

25]. Interestingly, the effect of fungal strain on fibre diameter was less pronounced in the RB samples compared to cereal dust, suggesting that substrate composition may interact with fungal pretreatment to influence the final BC nanostructure.

These results collectively emphasize the importance of both substrate choice and processing conditions in determining BC nanostructure. The ability to fine-tune fibre dimensions and network morphology through substrate selection, fungal pretreatment, and drying method offers a versatile toolkit for engineering BC with specific properties suited to various applications [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

3.3.2. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) Analysis

EDS analysis revealed that BC produced from SSF-treated rice bran and cereal dust primarily consisted of carbon and oxygen, confirming the preservation of cellulosic composition (

Table 1). BC from SSF-treated rice bran showed higher carbon content (65-69%) compared to cereal dust (53-64%), while cereal dust-derived BC exhibited higher oxygen content (35-46% vs. 31-35% in rice bran-derived BC). These differences were consistent across oven-dried and freeze-dried samples. The higher oxygen content in cereal dust-derived BC suggests a greater presence of O-containing functional groups, potentially influencing fibre interactions and network compactness. The observed variations in C/O ratios between substrates and fungal treatments indicate that the choice of waste substrate and SSF conditions can influence BC surface chemistry. These findings align with previous studies showing that BC composition can be affected by bacterial strain, growth conditions, and carbon source [31, 32]. Importantly, EDS analysis confirmed that SSF pretreatment did not introduce detectable contaminants, demonstrating the potential of this method for producing pure BC from agricultural wastes.

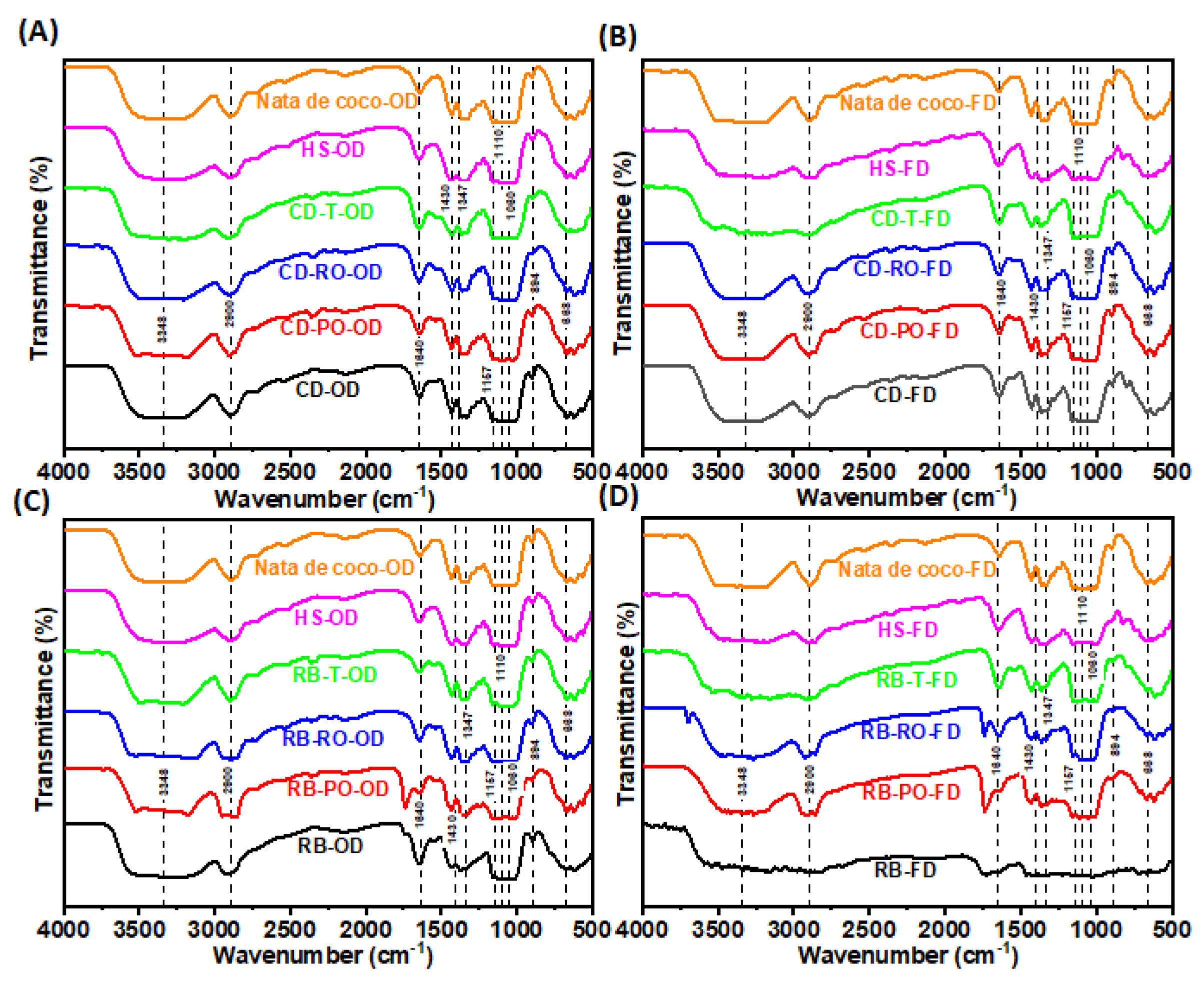

3.3.3. Fourier-Transformed Infrared Spectroscope (FTIR)

FTIR analysis of BC produced from SSF-treated rice bran and cereal dust revealed characteristic cellulose peaks, confirming the preservation of cellulose type I structure (

Figure 5). Key spectral peaks included O-H stretching (3300 cm

-1), C-H stretching (2900 cm

-1), adsorbed water (1640 cm

-1), CH

2 bending (crystallinity band, 1427 cm

-1), C-H bending (1350 cm

-1), C-O-C stretching (1160-1110 cm

-1) and C-O stretching (1060 cm

-1). These peaks are consistent with those reported for BC produced from conventional media [33, 34]. Some rice bran-derived samples (RB-FD, RB-PO-OD, RB-PO-FD, RB-RO-FD) showed an additional peak around 1700 cm

-1, potentially indicating slight oxidation of surface hydroxyls. In general, the FTIR spectra confirm that BC produced from SSF-treated agricultural wastes maintains the essential chemical structure of cellulose, with minor variations that may offer opportunities for tailoring physicochemical properties. These findings align with previous studies using other waste substrates for BC production [23, 35, 36] demonstrating the versatility of RB and CD wastes as feedstocks for BC synthesis.

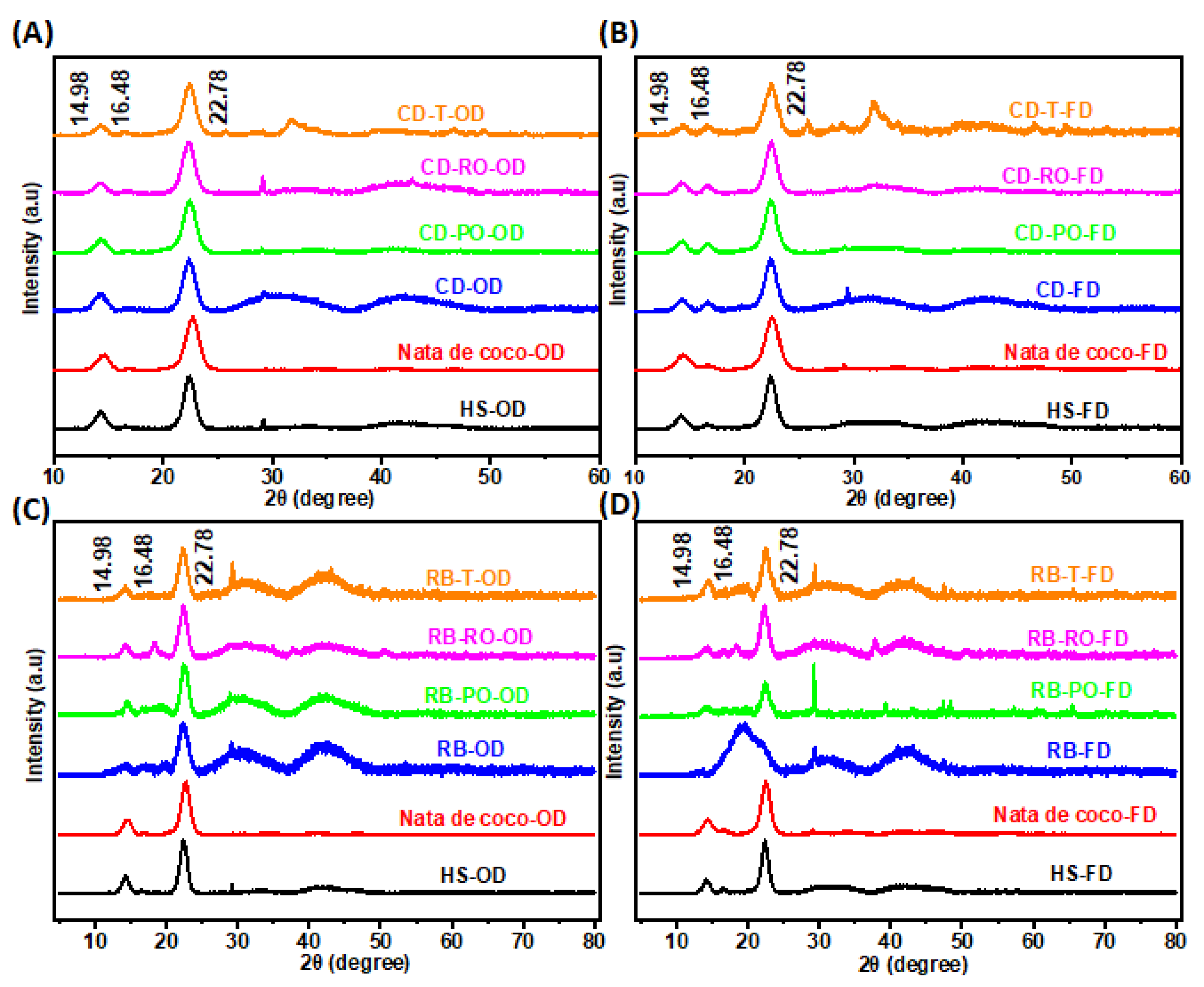

3.3.4. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD patterns of BC produced from SSF-treated RB and CD revealed characteristic peaks at 2θ = 14.9°, 16.5°, and 22.8°, corresponding to the typical cellulose I structure (

Figure 6A-D). These peaks were consistent across all samples, including the nata de coco and HS medium controls, confirming the preservation of BC's crystalline structure. However, some subtle differences were observed between samples. The BC from SSF-treated substrates showed additional broad peaks centred at 30° and between 40-50°, not present in the control samples. The freeze-dried rice bran samples exhibited a significant peak at 30°, corresponding to the (1̅22) plane, which was absent in most oven-dried samples. Lastly, the freeze-dried rice bran samples generally showed broader peaks, indicating lower crystallinity compared to oven-dried samples. These variations suggest that both the SSF pretreatment and drying method influence the crystalline structure of the produced BC. The presence of additional peaks and changes in peak intensity indicate potential modifications in cellulose arrangement and crystallinity, which could affect the material properties of the resulting BC.

The crystallinity index (CI) of BC samples was calculated based on the intensity of peaks at 2θ = 22.5° and 18.5°, corresponding to (110) and (200) planes (

Table 2) of the crystalline form of cellulose I [

1]. It was revealed that the BC from cereal dust showed high CI (94-99%), with oven-dried samples reaching ~99%. In contrast, the BC from rice bran exhibited lower CI, particularly in freeze-dried samples (69-79%). In terms of drying, oven-dried samples consistently showed higher CI than freeze-dried samples for both substrates. Lastly, the SSF treatment with different fungi had minimal impact on CI for cereal dust but affected rice bran samples more noticeably. These results align with XRD patterns, where sharper, more defined peaks correlate with higher crystallinity. The high CI of cereal dust-derived BC suggests a well-ordered cellulose structure, while the lower CI in rice bran-derived BC, especially freeze-dried samples, indicates increased amorphous regions. The variations in CI between substrates and drying methods demonstrate the potential to modulate BC crystallinity through feedstock selection and processing conditions. Higher crystallinity generally correlates with improved mechanical properties, while lower crystallinity may enhance properties such as swelling and drug loading capacity. These findings suggest opportunities for tailoring BC properties for specific applications by controlling crystallinity through waste media substrate choice and processing methods.

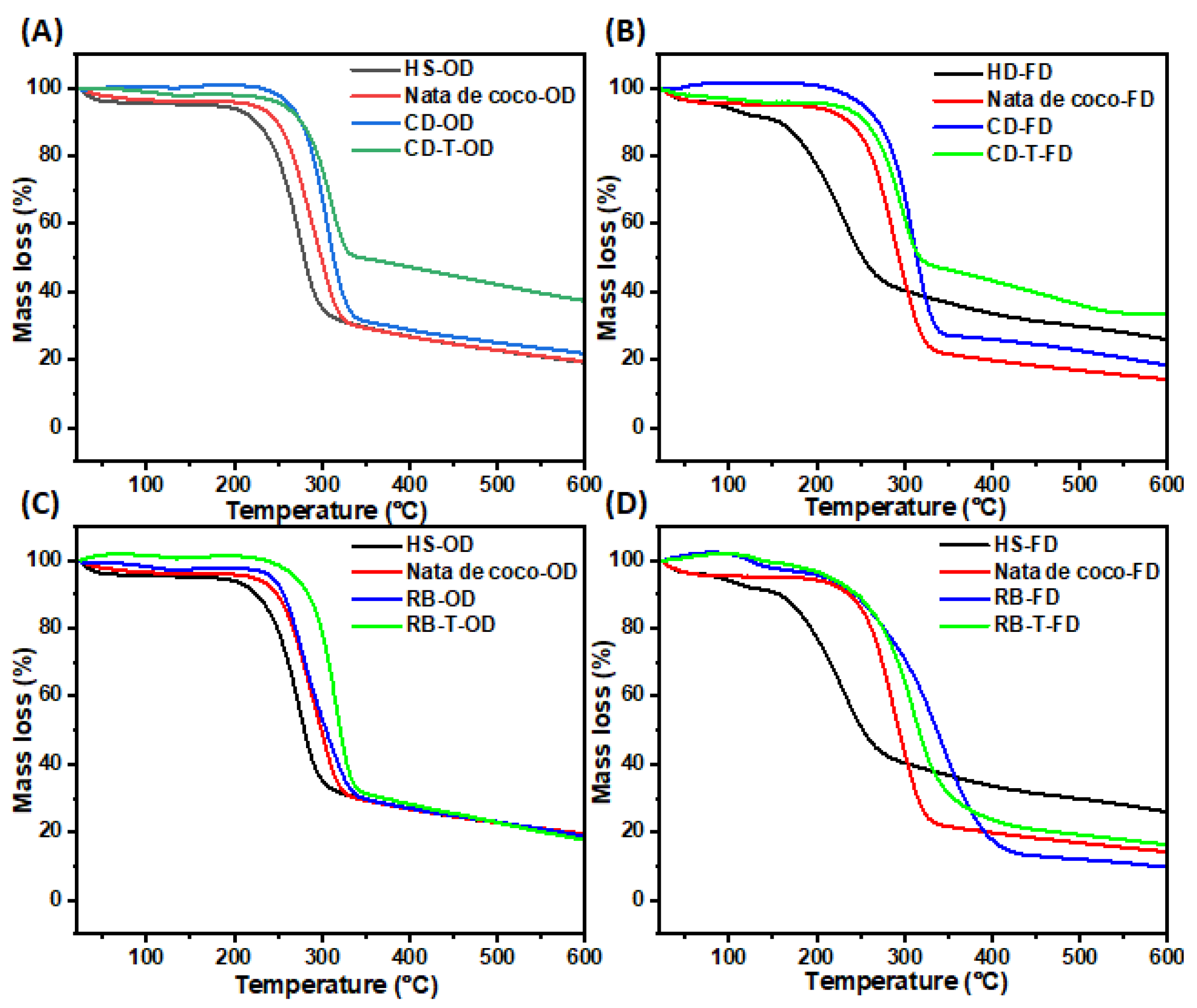

3.3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis of BC samples produced from untreated and SSF-treated cereal dust and rice bran revealed distinct thermal degradation profiles (

Figure 7). The initial mass loss for most samples occurred around 250°C, indicating the onset of thermal degradation. The BC from SSF-treated cereal dust (CD-T-OD) showed the highest thermal stability, with only ~60% mass loss at 600°C (

Figure 7A). It was also noted that the freeze-dried samples generally exhibited lower thermal stability compared to oven-dried counterparts. Moreover, the BC from SSF-treated rice bran (RB-T-OD) maintained its structure up to 290°C, showing improved thermal stability compared to untreated samples (

Figure 7C). In contrast, HS medium-derived BC, particularly freeze-dried (HS-FD), showed the lowest thermal stability, with degradation starting at 150°C. It was also observed that the SSF treatment generally improved the thermal stability of BC from both RB and CD media compared to untreated samples and control BC (nata de coco and HS medium). These results suggest that both the substrate type and SSF treatment influence the thermal properties of the resulting BC. The enhanced thermal stability of SSF-treated samples indicates potential improvements in BC structure and composition, which could be beneficial for applications requiring heat resistance.

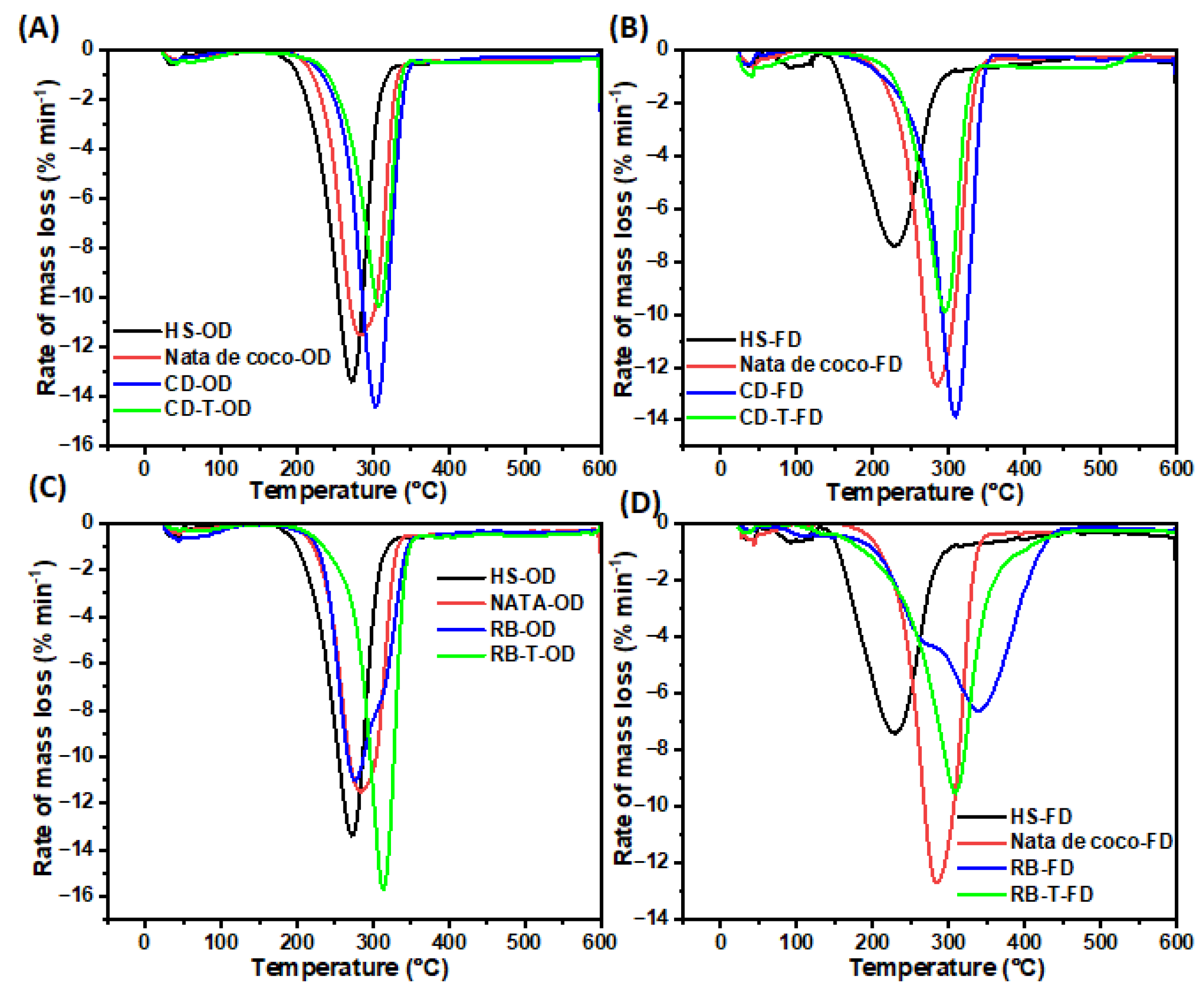

Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG) analyses revealed distinct thermal degradation profiles for BC samples produced from SSF-treated and untreated cereal dust and rice bran (

Figure 8). The SSF-treated cereal dust BC (CD-T-OD) showed improved thermal stability with a lower mass loss rate (10%) at 300°C compared to untreated samples (14%) (

Figure 8A). The freeze-dried SSF-treated cereal dust BC (CD-T-FD) exhibited the lowest mass loss rate (9.8%) at 290°C among cereal dust samples (

Figure 8B). The SSF-treated rice bran BC (RB-T-OD) showed a higher mass loss rate (16%) at a higher temperature (320°C) compared to untreated samples (11% at 280°C) (

Figure 8C). Lastly, the freeze-dried rice bran BC (RB-FD) demonstrated the lowest mass loss rate (7%) at 320°C among all samples (

Figure 8D). These results indicate that SSF treatment generally enhances the thermal stability of BC, with the effect more pronounced in cereal dust samples. The improved thermal properties likely result from increased crystallinity and better-organised cellulose structures, as suggested by XRD analysis (

Figure 6 and

Table 2). Our findings align with the previous studies which showed enhanced thermal stability in BC produced from agricultural wastes [

24]. The enhanced thermal stability of SSF-treated BC samples suggests potential applications in areas requiring heat-resistant materials, such as biomedical devices or electronics. Furthermore, the ability to modulate thermal properties through substrate selection and processing conditions offers opportunities for tailoring BC for specific applications.

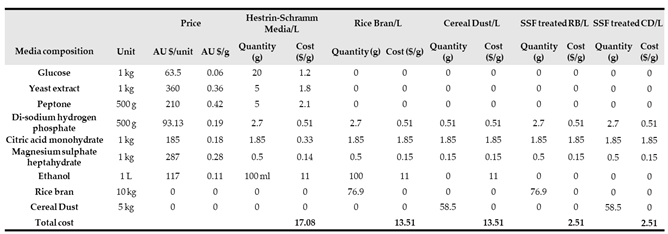

3.3.6. Cost Analysis

Table 3 shows the cost analysis of the conventional HS medium with unfermented and fermented RB and CD. The comparison of BC production cost for culture media revealed that replacing carbon and nitrogen sources in HS medium with unfermented RB and CD lowers the cost by up to 40%. Meanwhile, using SSF process to ferment these wastes has not only increased the yield of BC but also reduced the cost of media by around 90%.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the successful production of bacterial cellulose (BC) from rice bran and cereal dust pretreated by SSF, representing a significant step towards sustainable and cost-effective BC production. The use of these abundant agricultural waste addresses two critical challenges: the high cost of conventional BC production media and the environmental impact of agro-industrial waste. SSF pretreatment effectively enhanced the bioavailability of nutrients in rice bran and cereal dust, resulting in improved BC yields compared to untreated substrates. Notably, rice bran fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus produced the highest BC yield (1.52 g/L dry weight), surpassing even the standard HS medium. This finding aligns with previous studies showing the potential of SSF to unlock nutrients from complex biomass (Sukma et al., 2021), and extends this approach to BC production.

Comprehensive physicochemical characterisation revealed that BC produced from SSF-treated substrates maintains the fundamental nanostructure and chemical identity of cellulose, with some variations that could be advantageous for specific applications. SEM analysis showed that both the choice of fungal strain for SSF and the drying method (oven-drying vs. freeze-drying) significantly influenced BC nanostructure, fibre diameter, and morphology. These structural differences could be leveraged to tailor BC properties for various applications, from tissue engineering scaffolds to filtration membranes (Ul-Islam et al., 2020). FTIR and XRD analyses confirmed the preservation of cellulose I structure in BC from SSF-treated substrates, with some samples showing additional peaks that suggest slight modifications to surface chemistry or crystallinity. These subtle changes could potentially enhance certain properties, such as thermal stability or reactivity, without compromising the essential cellulose structure. The observed variations in crystallinity index between substrates and drying methods demonstrate the potential to modulate BC properties through feedstock selection and processing conditions. On the other hand, thermogravimetric analysis revealed that SSF treatment generally improved the thermal stability of BC from both rice bran and cereal dust media. This enhanced thermal resistance could expand the potential applications of BC to areas requiring heat-stable materials, such as biomedical devices or electronics components (Mohammadkazemi et al., 2015).

Perhaps most significantly, the cost analysis revealed that using SSF-treated agro-food wastes could reduce BC media costs by up to 90% compared to standard HS medium. This dramatic cost reduction, coupled with the valorisation of agricultural waste streams, presents a compelling case for the industrial adoption of this approach. The potential for significant cost savings while maintaining or improving BC quality could be advantageous for the large-scale production of this versatile biopolymer. The findings of this study have broad implications for both sustainable materials production and waste management in the agro-food industry. By demonstrating the feasibility of using minimally processed agricultural wastes for high-value biopolymer production, this research contributes to the growing body of work on circular bioeconomy strategies (Sheldon, 2020). The approach developed here could be extended to other types of agro-industrial wastes, potentially revolutionising the production of bio-based materials while simultaneously addressing waste management challenges. Moreover, the ability to modulate BC properties through substrate selection, SSF conditions, and drying methods offers new avenues for tailoring this material for specific applications. This versatility could expand the use of BC across various sectors, from biomedical applications to advanced materials for electronics and environmental remediation (Azeredo et al., 2019). Hence, this study provides a proof-of-concept for the sustainable valorisation of agro-food wastes into high-value BC biomaterials. The demonstrated improvements in yield, cost-effectiveness, and potential for property customisation pave the way for scaled-up, environmentally friendly BC production processes. Future research should focus on optimising SSF conditions for different waste streams, exploring the full range of attainable BC properties, and developing specific applications that leverage the unique characteristics of waste-derived BC.

5. Conclusion

SSF fungal bioprocessing successfully enhanced the digestibility and bioavailability of agricultural waste media, boosting BC yields by up to 2-fold. Tailored enzyme biocatalysis liberated nutrients from protective fibrillar matrices without loss of fundamental nanostructure or chemistry. The drying technique emerged as a useful handle to bespoke tailor hierarchical length scales from nanofiber widths to macro void pores for intended bio-functionality. The cost analysis of BC production from agri-food wastes revealed that BC produced from fermented rice bran and cereal dust is almost 90% cheaper than HS medium. Overall, the outcomes pioneer an integrated cereal crop waste valorisation and cellulose manufacturing platform reconciling circularity, affordability and customisability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Shriya Henry and Dr Vito Butardo Jr; methodology, Shriya Henry, Dr Sushil Dhital and Dr Vito Butardo Jr; software, Shriya Henry; validation, Dr Vito Butardo Jr and Shriya Henry; formal analysis and investigation, Shriya Henry; writing—original draft preparation, Shriya Henry; writing—review and editing, Dr Vito Butardo Jr, Dr Sushil Dhital and Dr Huseyin Sumer. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. The data 16S rRNA data for the molecular identification of the isolate is available in NCBI as Genbank PP421219.1.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr Francois Malherbe for his technical support and suggestions. Shriya would like to acknowledge the Swinburne Tuition Fee Scholarship from Swinburne University. The authors would also like to thank SunRice and Rex James Stockfeed Ltd for the rice bran and cereal dust used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hussain, Z., et al., Production of bacterial cellulose from industrial wastes: a review. Cellulose, 2019. 26(5): p. 2895-2911. [CrossRef]

- Dungani, R., et al., Agricultural waste fibers towards sustainability and advanced utilization: A review. Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, 2016. 15(1-2): p. 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, T., et al., Cost-Effective Synthesis of Bacterial Cellulose and Its Applications in the Food and Environmental Sectors. Gels, 2022. 8(9). [CrossRef]

- Brunschwiler, C., et al., Direct measurement of rice bran lipase activity for inactivation kinetics and storage stability prediction. Journal of Cereal Science, 2013. 58(2): p. 272-277. [CrossRef]

- Christopher Narh, et al., Rice Bran, an Alternative Nitrogen Source for Acetobacter xylinum Bacterial Cellulose Synthesis. Bioresources.com, 2018. 13(2): p. 4346-4363. [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M., Recovery of high added-value components from food wastes: Conventional, emerging technologies and commercialized applications. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2012. 26(2): p. 68-87. [CrossRef]

- Urbina, L., et al., A review of bacterial cellulose: sustainable production from agricultural waste and applications in various fields. Cellulose, 2021. 28(13): p. 8229-8253. [CrossRef]

- Hayder Kh. Q. Ali1, a.M.M.D.Z., Utilization of Agro-Residual Ligno-Cellulosic Substances by Using Solid State Fermentation: A Review. Croatian Journal of Food Technology, Biotechnology, 2011. 6 (1-2), 5-12.

- Kupski, L., et al., Solid-state fermentation for the enrichment and extraction of proteins and antioxidant compounds in rice bran by Rhizopus oryzae. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 2012. 55(6): p. 937-942. [CrossRef]

- Ellaiah, P., et al., Production of lipase by immobilized cells of Aspergillus niger. Process Biochemistry, 2004. 39(5): p. 525-528. [CrossRef]

- Adinarayana, K., P. Ellaiah, and D.S. Prasad, Purification and partial characterization of thermostable serine alkaline protease from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis PE-11. AAPS PharmSciTech, 2003. 4(4): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Baysal, Z., F. Uyar, and Ç. Aytekin, Solid state fermentation for production of α-amylase by a thermotolerant Bacillus subtilis from hot-spring water. Process Biochemistry, 2003. 38(12): p. 1665-1668. [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, H.K., et al., Production of a thermostable α-amylase from Bacillus sp. PS-7 by solid state fermentation and its synergistic use in the hydrolysis of malt starch for alcohol production. Process Biochemistry, 2005. 40(2): p. 525-534. [CrossRef]

- Sukma, A.C.T., H. Oktavianty, and S. Sumardiono, Optimization of solid-state fermentation condition for crude protein enrichment of rice bran using Rhizopus oryzae in tray bioreactor. Indonesian Journal of Biotechnology, 2021. 26(1). [CrossRef]

- Shriya Henry, V.B.J., Huseyin Sumer, Production of Bacterial Cellulose from Agricultural Wastes for Tissue Scaffold Application. Swinburne University of Technology, 2024.

- Oliveira, M.d.S., et al., Changes in lipid, fatty acids and phospholipids composition of whole rice bran after solid-state fungal fermentation. Bioresource Technology, 2011. 102(17): p. 8335-8338.

- Borzani, W. and S.J.d. Souza, Mechanism of the film thickness increasing during the bacterial production of cellulose on non-agitated liquid media. 1995. 17(11): p. 1271–1272.

- Ruka, D.R., G.P. Simon, and K.M. Dean, Altering the growth conditions of Gluconacetobacter xylinus to maximize the yield of bacterial cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012. 89(2): p. 613-622. [CrossRef]

- Nam, S., et al., Segal crystallinity index revisited by the simulation of X-ray diffraction patterns of cotton cellulose Ibeta and cellulose II. Carbohydr Polym, 2016. 135: p. 1-9.

- Wang, J., J. Tavakoli, and Y. Tang, Bacterial cellulose production, properties and applications with different culture methods – A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019. 219(May): p. 63-76.

- Holmes, D., Bacterial Cellulose. Master of Engineering, Department of Chemical and Process Engineering University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand, 2004.

- Aytekin, A.Ö., D.D. Demirbağ, and T. Bayrakdar, The statistical optimization of bacterial cellulose production via semi-continuous operation mode. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2016. 37: p. 243-250. [CrossRef]

- Abdelraof, M., M.S. Hasanin, and H. El -Saied, Ecofriendly green conversion of potato peel wastes to high productivity bacterial cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019. 211: p. 75-83.

- Mohammadkazemi, F., M. Azin, and A. Ashori, Production of bacterial cellulose using different carbon sources and culture media. Carbohydr Polym, 2015. 117: p. 518-523. [CrossRef]

- Du, R., et al., Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose produced by Gluconacetobacter xylinus isolated from Chinese persimmon vinegar. Carbohydr Polym, 2018. 194: p. 200-207. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S., et al., Physicochemical characterization of high-quality bacterial cellulose produced by Komagataeibacter sp. strain W1 and identification of the associated genes in bacterial cellulose production. RSC Advances, 2017. 7(71): p. 45145-45155. [CrossRef]

- Dórame-Miranda, R.F., et al., Bacterial cellulose production by Gluconacetobacter entanii using pecan nutshell as carbon source and its chemical functionalization. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019. 207: p. 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.U. and A. Appaiah, Optimization of culture conditions for bacterial cellulose production from Gluconacetobacter hansenii UAC09. Annals of Microbiology, 2011. 61(4): p. 781-787. [CrossRef]

- Slapšak, N., et al., Gluconacetobacter maltaceti sp. nov., a novel vinegar producing acetic acid bacterium. Systematic and applied microbiology, 2013. 36(1): p. 17-21. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.C., et al., Morphology and structure characterization of bacterial celluloses produced by different strains in agitated culture. Journal of applied microbiology, 2014. 117(5): p. 1305-1311. [CrossRef]

- Kongruang, S., Bacterial Cellulose Production by Acetobacter xylinum Strains from Agricultural Waste Products. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2008. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, K.C., et al., Production of bacterial cellulose biopolymers in media containing rice and corn hydrolysate as carbon sources. Polymers and Polymer Composites, 2021. 29(9_suppl): p. S1466-S1474.

- Popescu, C.-M., et al., Spectral Characterization of Eucalyptus Wood. Applied Spectroscopy, 2007. 61(11): p. 1168-1177. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.J., et al., Controlling the transparency and rheology of nanocellulose gels with the extent of carboxylation. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2020. 245: p. 116566. [CrossRef]

- Castro, C., et al., Structural characterization of bacterial cellulose produced by Gluconacetobacter swingsii sp. from Colombian agroindustrial wastes. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2011. 84(1): p. 96-102. [CrossRef]

- Tayo Adebayo Bc, M.O.A.J.F.S., Effect of different fruit juice media on bacterial cellulose production by Acinetobacter sp. BAN1 and Acetobacter pasteurianus PW1. J Adv Biol Biotechnol, 2017. 14: p. 2394-1081.

Figure 1.

Large-scale BC production yield from untreated and treated waste media formulations. The (A) wet and (B) dry weight, was determined on different waste formulations; Hestrin-Schramm (HS), rice bran (RB), cereal dust (CD), rice bran fermented with R. oryzae (RB-RO), rice bran fermented with R. oligosporus (RB-T), rice bran fermented with P. osteratus (RB-PO), cereal dust fermented with R. oligosporus (CD-T), cereal dust fermented with P. osteratus (CD-PO), cereal dust fermented with R. oryzae (CD-RO). The error bar represents standard deviation. Different letters represent significant differences.

Figure 1.

Large-scale BC production yield from untreated and treated waste media formulations. The (A) wet and (B) dry weight, was determined on different waste formulations; Hestrin-Schramm (HS), rice bran (RB), cereal dust (CD), rice bran fermented with R. oryzae (RB-RO), rice bran fermented with R. oligosporus (RB-T), rice bran fermented with P. osteratus (RB-PO), cereal dust fermented with R. oligosporus (CD-T), cereal dust fermented with P. osteratus (CD-PO), cereal dust fermented with R. oryzae (CD-RO). The error bar represents standard deviation. Different letters represent significant differences.

Figure 2.

SEM images of commercially available cellulose Nata de coco and cellulose produced from N. entanii in HS culture medium. The (A) and (C) freeze (FD) and oven dried (OD) Nata de coco, (B and D) freeze (FD) and oven dried (OD) cellulose from N. entanii (scale bar- 200 nm).

Figure 2.

SEM images of commercially available cellulose Nata de coco and cellulose produced from N. entanii in HS culture medium. The (A) and (C) freeze (FD) and oven dried (OD) Nata de coco, (B and D) freeze (FD) and oven dried (OD) cellulose from N. entanii (scale bar- 200 nm).

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of BC produced from fermented rice bran, with P. osteratus, R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) P. osteratus oven-dried (RB-PO-OD), (D) freeze-dried (RB-PO-FD), (B) R. oryzae oven-dried (RB-RO-OD), (E) freeze-dried (RB-RO-FD), (C) R. oligosporus oven dried (RB-T-OD), and (F) freeze-dried and (RB-T-FD) (scale bar- 200 nm).

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of BC produced from fermented rice bran, with P. osteratus, R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) P. osteratus oven-dried (RB-PO-OD), (D) freeze-dried (RB-PO-FD), (B) R. oryzae oven-dried (RB-RO-OD), (E) freeze-dried (RB-RO-FD), (C) R. oligosporus oven dried (RB-T-OD), and (F) freeze-dried and (RB-T-FD) (scale bar- 200 nm).

Figure 4.

Fibre diameter graphs of BC produced from fermented rice bran, with P. osteratus, R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) P. osteratus, oven-dried (RB-PO-OD), (D) freeze-dried (RB-PO-FD), (B) R. oryzae oven-dried (RB-RO-OD), (E) freeze-dried (RB-RO-FD), (C) R. oligosporus oven dried (RB-T-OD), and (F) freeze-dried (RB-T-FD). The curve represents the mean value of the fibre diameter.

Figure 4.

Fibre diameter graphs of BC produced from fermented rice bran, with P. osteratus, R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) P. osteratus, oven-dried (RB-PO-OD), (D) freeze-dried (RB-PO-FD), (B) R. oryzae oven-dried (RB-RO-OD), (E) freeze-dried (RB-RO-FD), (C) R. oligosporus oven dried (RB-T-OD), and (F) freeze-dried (RB-T-FD). The curve represents the mean value of the fibre diameter.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of oven and freeze-dried BC synthesised from SSF treated cereal dust with P. osteratus), R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) and (B) P. osteratus (CD-PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (CD-RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (CD-T-OD/FD). The (C) and (D) BC synthesised from SSF treated rice bran with P. osteratus (RB-PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (RB-RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (RB-T-OD/FD).

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of oven and freeze-dried BC synthesised from SSF treated cereal dust with P. osteratus), R. oryzae and R. oligosporus. The (A) and (B) P. osteratus (CD-PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (CD-RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (CD-T-OD/FD). The (C) and (D) BC synthesised from SSF treated rice bran with P. osteratus (RB-PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (RB-RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (RB-T-OD/FD).

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction patterns of BC synthesised from SSF treated cereal dust and rice bran. The (A) and (B) cereal dust (CD) and (C) and (D) rice bran (RB) with P. osteratus (PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (T-OD/FD) compared to nata de coco and HS medium, oven-dried (OD) and freeze-dried (FD).

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction patterns of BC synthesised from SSF treated cereal dust and rice bran. The (A) and (B) cereal dust (CD) and (C) and (D) rice bran (RB) with P. osteratus (PO-OD/FD), R. oryzae (RO-OD/FD) and R. oligosporus (T-OD/FD) compared to nata de coco and HS medium, oven-dried (OD) and freeze-dried (FD).

Figure 7.

Thermogravimetric analysis of BC samples produced in untreated and treated cereal dust and rice bran with R. oligosporus. The (A) BC samples produced in cereal dust R. oligosporus oven-dried (OD) and (B) freeze-dried (FD). The (C) BC samples produced in rice bran R. oligosporus (T) oven-dried (OD) and (D) and freeze-dried (FD).

Figure 7.

Thermogravimetric analysis of BC samples produced in untreated and treated cereal dust and rice bran with R. oligosporus. The (A) BC samples produced in cereal dust R. oligosporus oven-dried (OD) and (B) freeze-dried (FD). The (C) BC samples produced in rice bran R. oligosporus (T) oven-dried (OD) and (D) and freeze-dried (FD).

Figure 8.

Derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) analysis of BC samples produced in untreated and treated cereal dust and rice bran with R. oligosporus. The (A) BC samples produced in cereal dust (CD) with R. oligosporus oven-dried (OD), (B) freeze-dried (FD), (C) BC samples produced in rice bran with R. oligosporus (T) oven-dried (OD), and (D) freeze-dried (FD).

Figure 8.

Derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) analysis of BC samples produced in untreated and treated cereal dust and rice bran with R. oligosporus. The (A) BC samples produced in cereal dust (CD) with R. oligosporus oven-dried (OD), (B) freeze-dried (FD), (C) BC samples produced in rice bran with R. oligosporus (T) oven-dried (OD), and (D) freeze-dried (FD).

Table 1.

Elemental composition of C and O in BC produced from fermented rice bran and cereal dust in OD and FD samples.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of C and O in BC produced from fermented rice bran and cereal dust in OD and FD samples.

| Samples |

Oven-dried |

Freeze-dried |

| C |

O |

C |

O |

| Rice bran |

68.0% |

32.0% |

75.1% |

24.9% |

| Rice bran (Pleurotus osteratus) |

68.7% |

31.3% |

63.7% |

36.3% |

| Rice bran (Rhizopus oryzae) |

67.0% |

33.0% |

57.6% |

42.4% |

| Rice bran (Rhizopus oligosporus) |

65.2% |

34.8% |

59.6% |

40.4% |

| Cereal Dust |

65.4% |

34.6% |

59.8% |

40.2% |

| Cereal Dust (Pleurotus osteratus) |

64.3% |

35.7% |

57.1% |

42.9% |

| Cereal dust (Rhizopus oryzae) |

63.2% |

36.8% |

53.8% |

46.2% |

| Cereal dust (Rhizopus oligosporus) |

59.9% |

40.1% |

53.8% |

46.2% |

Table 2.

The crystallinity index of the oven and freeze-dried samples of unfermented and fermented rice bran and cereal dust.

Table 2.

The crystallinity index of the oven and freeze-dried samples of unfermented and fermented rice bran and cereal dust.

| |

Crystallinity Index |

| Bacterial cellulose samples |

Oven-dried |

Freeze-dried |

| Rice bran |

94.3% |

- |

| Rice bran (Pleurotus osteratus) |

83.8% |

69.3% |

| Rice bran (Rhizopus Oryzae) |

72.0% |

72.0% |

| Rice bran (Rhizopus oligosporus) |

95.2% |

79.0% |

| Cereal Dust |

98.8% |

99.6% |

| Cereal Dust (Pleurotus osteratus) |

98.6% |

97.4% |

| Cereal dust (Rhizopus Oryzae)

|

99.8% |

96.2% |

| Cereal dust (Rhizopus oligosporus) |

94.9% |

89.8% |

Table 3.

Cost analysis of bacterial cellulose produced from HS medium vs unfermented and fermented rice bran (RB) and cereal dust (CD) in g/L.

Table 3.

Cost analysis of bacterial cellulose produced from HS medium vs unfermented and fermented rice bran (RB) and cereal dust (CD) in g/L.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).