Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wood Sampling and Processing

2.2. Extraction of the DNA and DNA Pooling

2.3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Meteorological Data

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing

3.2. Relative Abundance

3.2.1. Phylum Level

3.2.2. Class Level

3.2.3. Order Level

3.2.4. Family Level

3.2.5. Genus Level

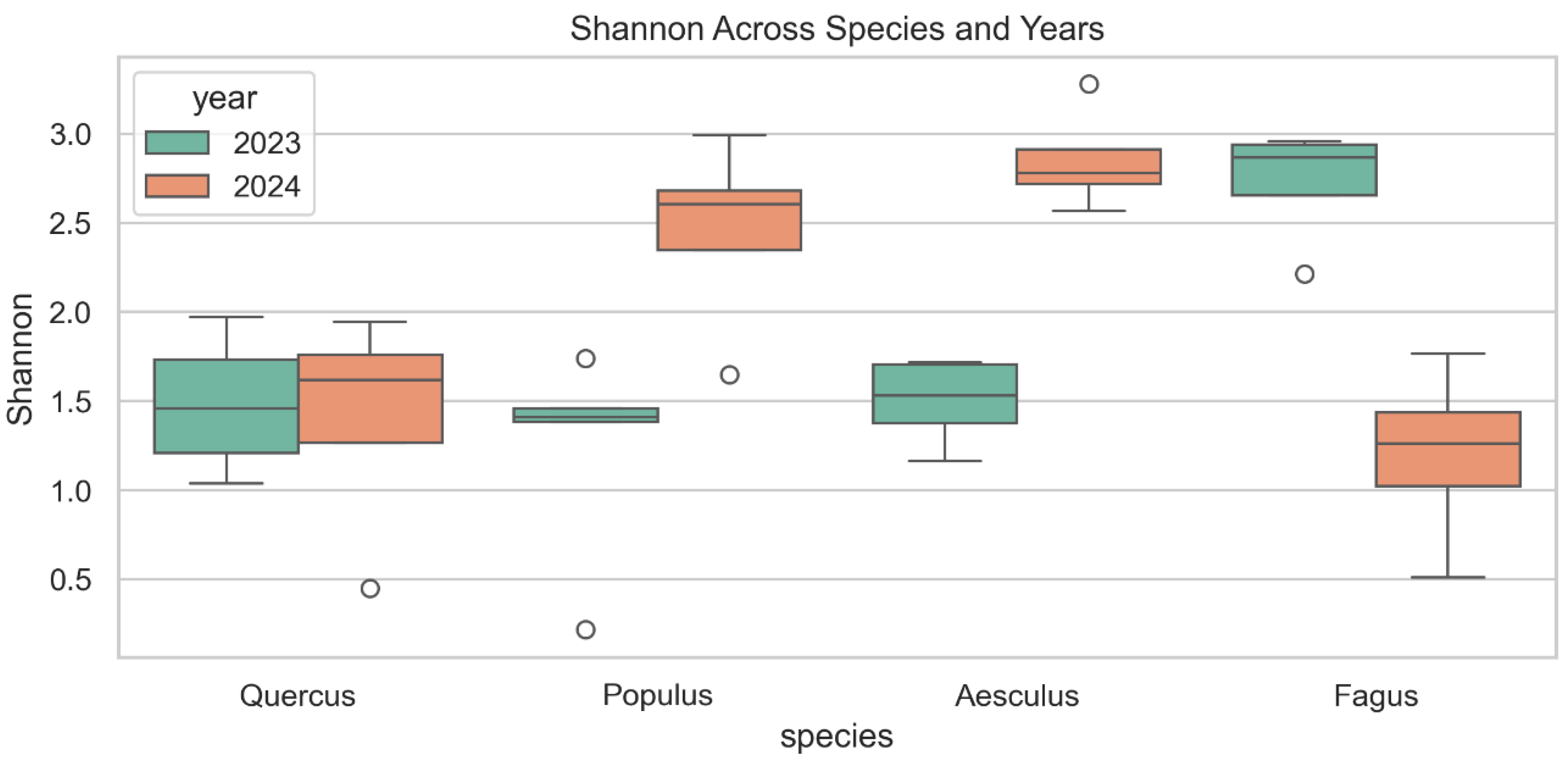

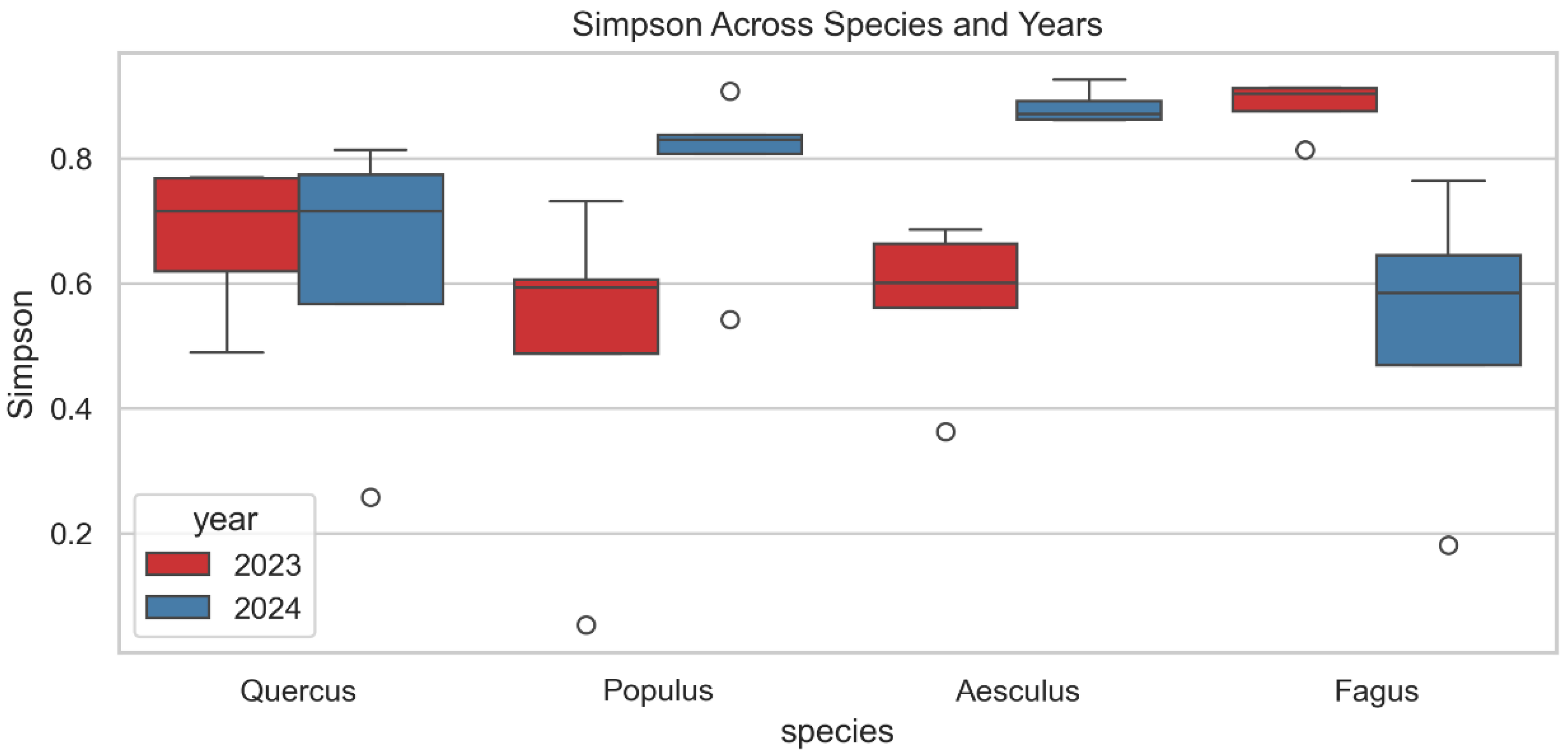

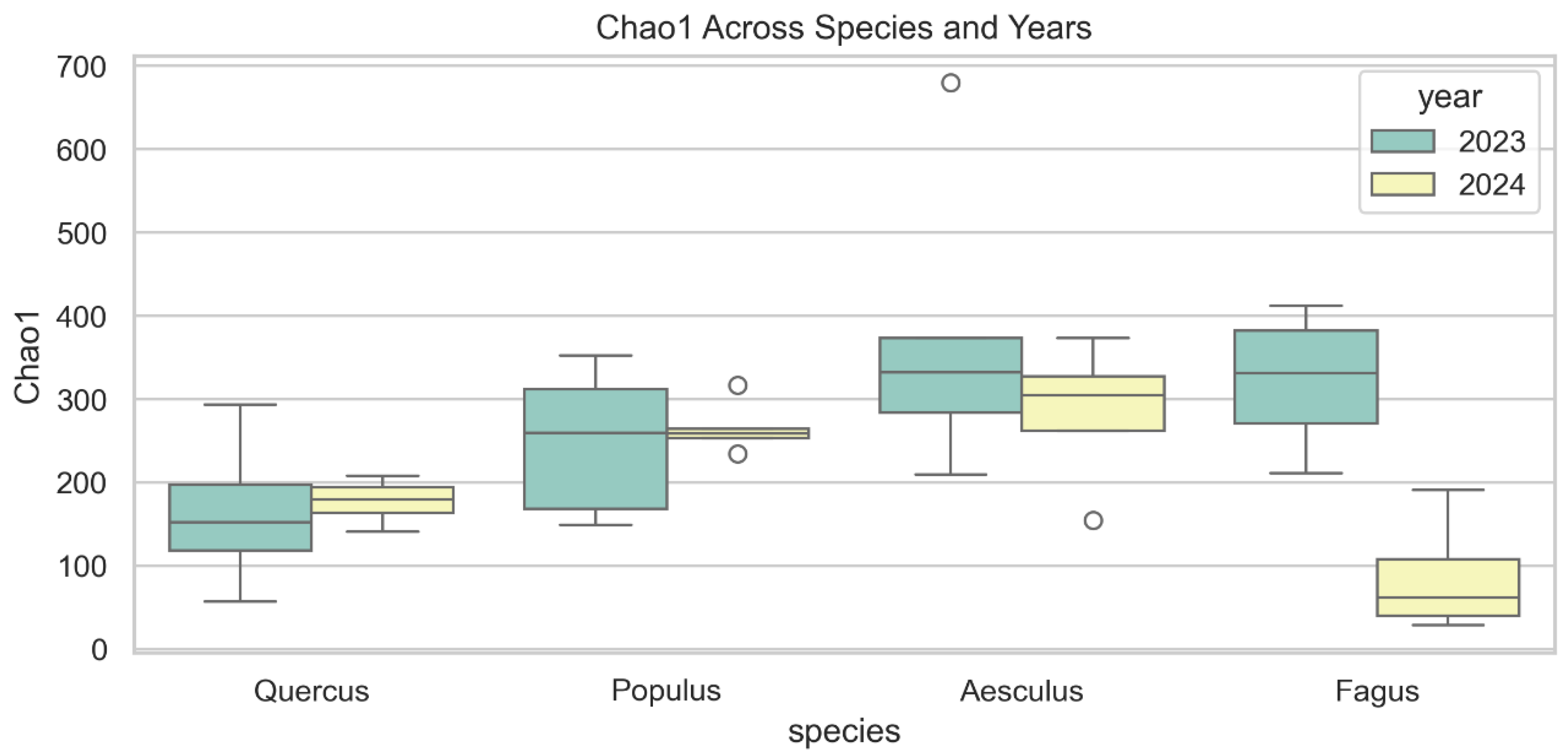

3.3. Alfa Diversity

3.3.1. Shannon Diversity Index

3.3.2. Simpson Diversity Index

3.3.3. Chao1 Richness

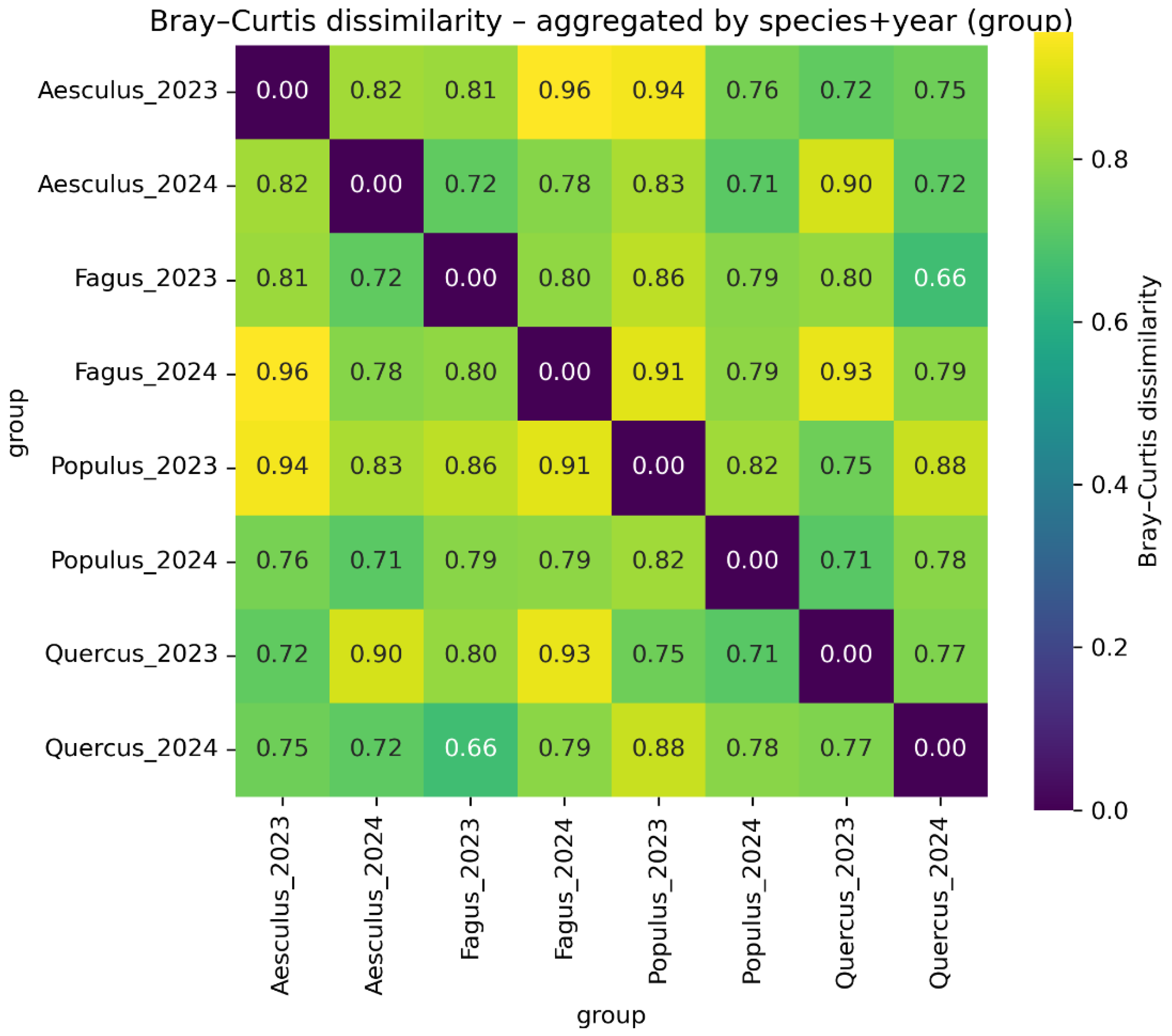

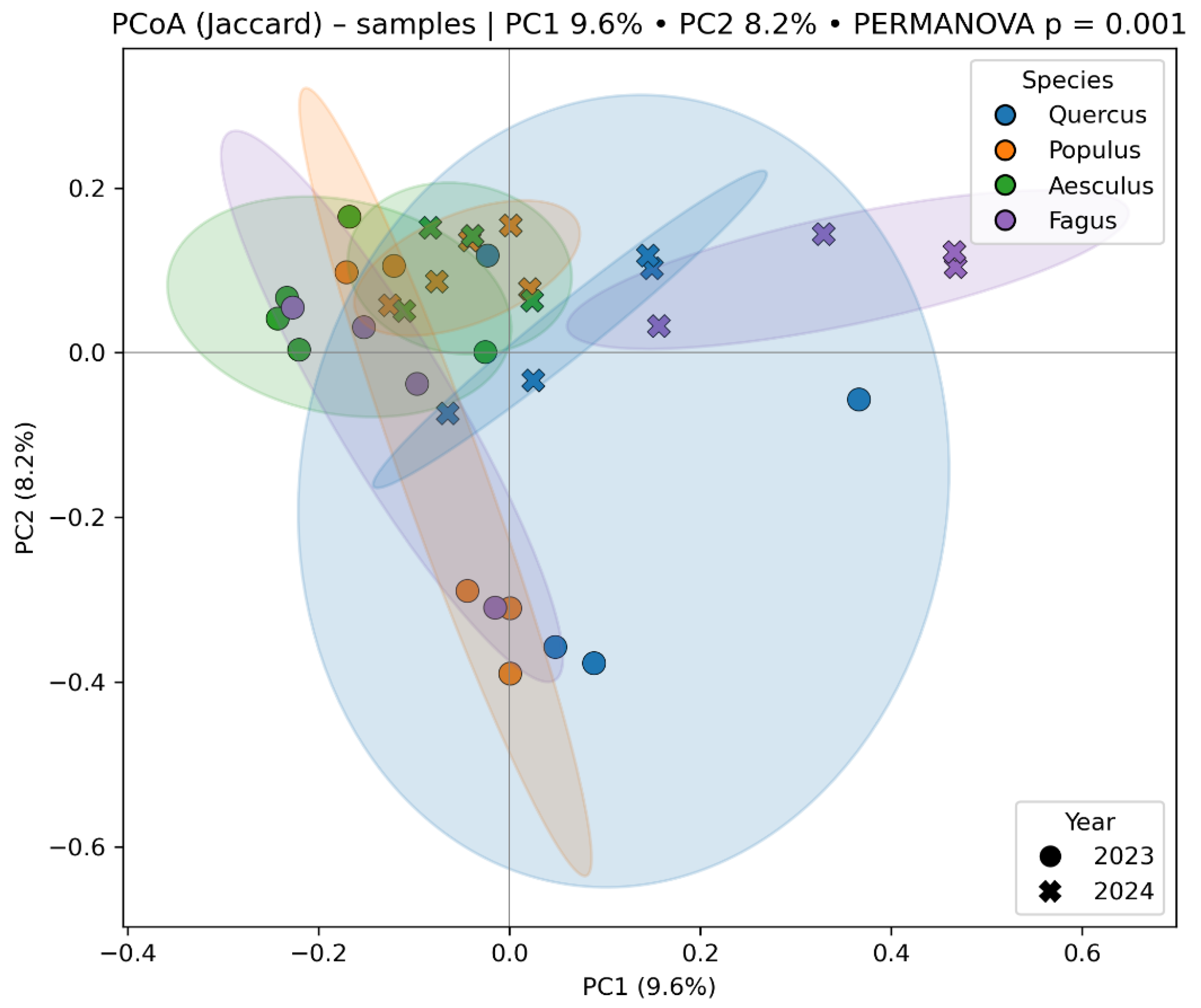

3.4. Beta Diversity

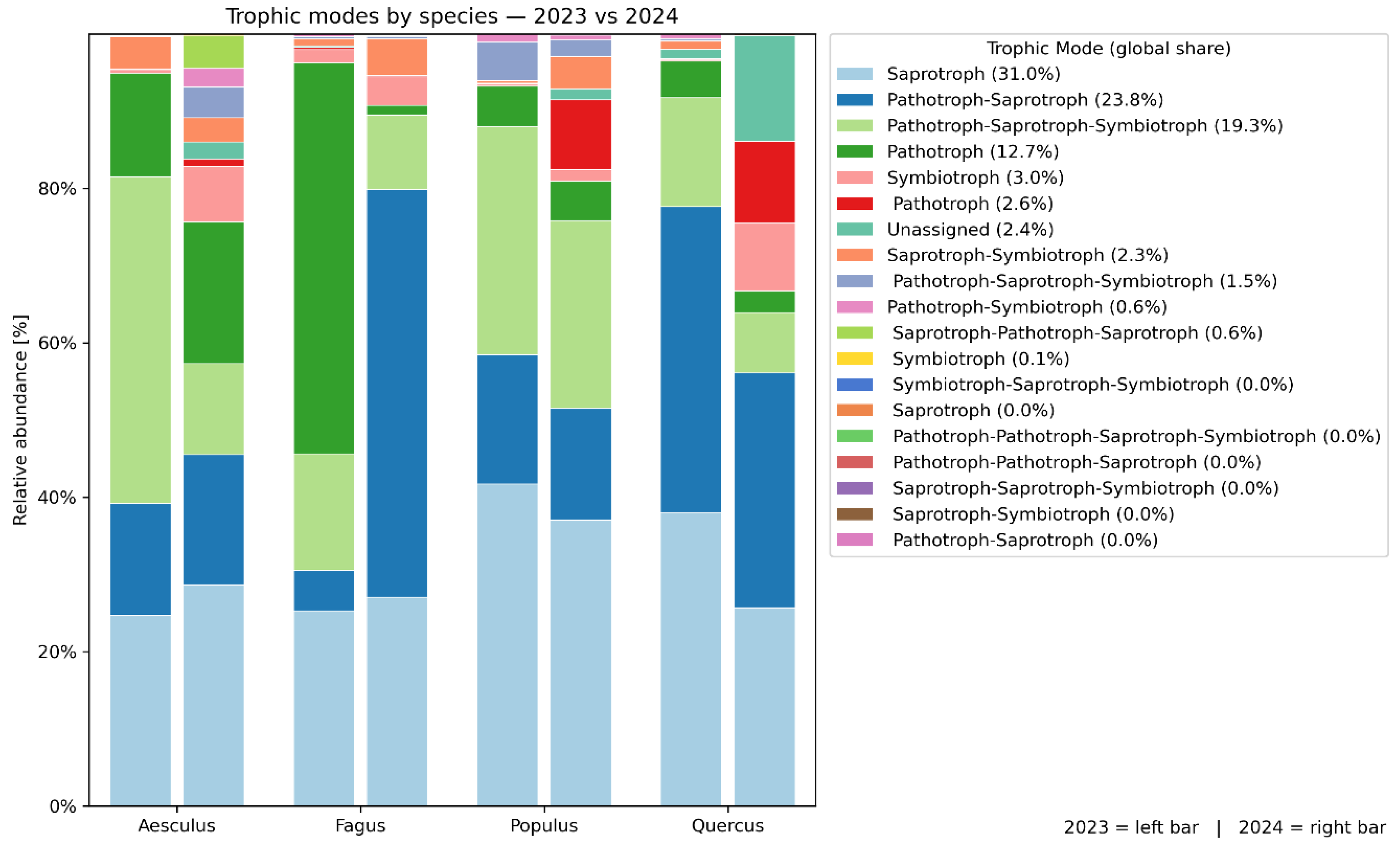

3.5. FUNGuild Trofic Groups

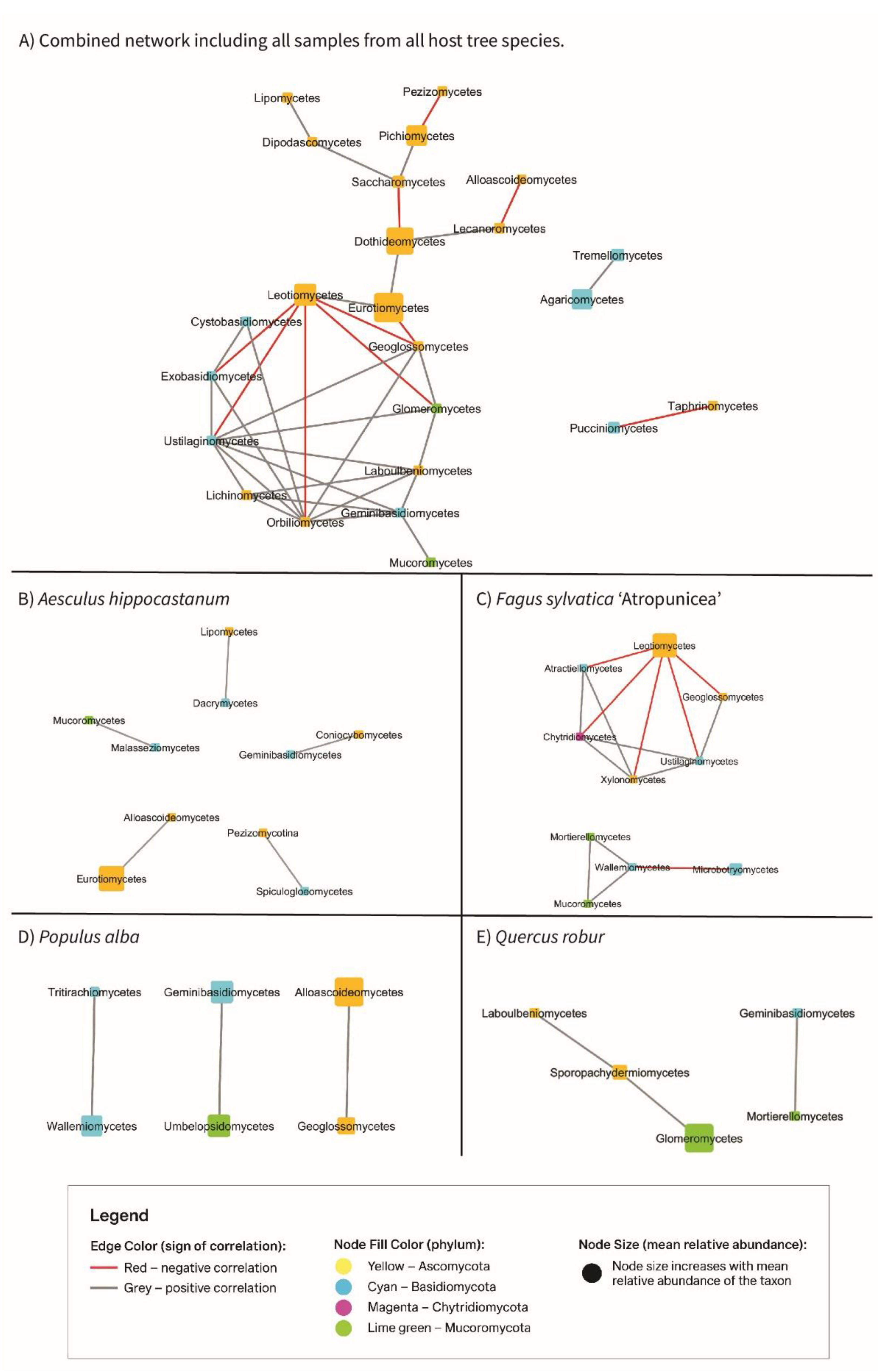

3.6. Cytoscape

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Blicharska, M.; Mikusinski, G. Incorporating Social and Cultural Significance of Large Old Trees in Conservation Policy. Conservation Biology 2014, 28, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C. The Forest and the City - the cultural landscape of urban woodland; 2008.

- Stagoll, K.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Knight, E.; Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D. Large trees are keystone structures in urban parks. Conservation Letters 2012, 5, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Laurance, W.F.; Franklin, J.F. Global Decline in Large Old Trees. Science 2012, 338, 1305–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, N. Environmental arboriculture, tree ecology and veteran tree management. Arboricultural Journal 2002, 26, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, F.W.M.R.; Engels, J.; Mattheck, C. Fungal Strategies of Wood Decay in Trees; Springer: 2000.

- Lonsdale, D. Principles of Tree Hazard Assessment and Management; Stationery Office: 1999.

- Parfitt, D.; Hunt, J.; Dockrell, D.; Rogers, H.J.; Boddy, L. Do all trees carry the seeds of their own destruction? PCR reveals numerous wood decay fungi latently present in sapwood of a wide range of angiosperm trees. Fungal Ecology 2010, 3, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, L.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Chapter 12 Basidiomycete community development in temperate angiosperm wood. In British Mycological Society Symposia Series, Boddy, L., Frankland, J.C., van West, P., Eds.; Academic Press: 2008; Volume 28, pp. 211–237.

- Gilmartin, E.C.; Jusino, M.A.; Pyne, E.J.; Banik, M.T.; Lindner, D.L.; Boddy, L. Fungal endophytes and origins of decay in beech (Fagus sylvatica) sapwood. Fungal Ecology 2022, 59, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Gazis, R.; Skaltsas, D.; Chaverri, P.; Hibbett, D. Unexpected diversity of basidiomycetous endophytes in sapwood and leaves of Hevea. Mycologia 2015, 107, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukasawa, Y. Ecological impacts of fungal wood decay types: A review of current knowledge and future research directions. Ecological Research 2021, 36, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Guo, L.-D. Endophytic fungal diversity: review of traditional and molecular techniques. Mycology 2012, 3, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoim Pablo, R.; van Overbeek Leonard, S.; Berg, G.; Pirttilä Anna, M.; Compant, S.; Campisano, A.; Döring, M.; Sessitsch, A. The Hidden World within Plants: Ecological and Evolutionary Considerations for Defining Functioning of Microbial Endophytes. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2015, 79, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Doilom, M.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D.; Manawasinghe, I.S.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Balasuriya, A.; Thakshila, S.A.D.; Luo, M.; Mapook, A.; et al. Challenges and update on fungal endophytes: classification, definition, diversity, ecology, evolution and functions. Fungal Diversity 2025, 131, 301–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Kennedy, P.G.; Liew, F.J.; Schilling, J.S. Fungal endophytes as priority colonizers initiating wood decomposition. Functional Ecology 2017, 31, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Barron, E.S.; Boddy, L.; Dahlberg, A.; Griffith, G.W.; Nordén, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Perini, C.; Senn-Irlet, B.; Halme, P. A fungal perspective on conservation biology. Conservation Biology 2015, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth David, L.; Lücking, R. Fungal Diversity Revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 Million Species. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Nilsson, R.H.; Tedersoo, L.; Abarenkov, K.; Carlsen, T.; Kjøller, R.; Kõljalg, U.; Pennanen, T.; Rosendahl, S.; Stenlid, J.; et al. Fungal community analysis by high-throughput sequencing of amplified markers – a user's guide. New Phytologist 2013, 199, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M. The Fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 million species? American Journal of Botany 2011, 98, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toju, H.; Tanabe, A.S.; Yamamoto, S.; Sato, H. High-Coverage ITS Primers for the DNA-Based Identification of Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes in Environmental Samples. PLOS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Baldrian, P.; Tedersoo, L. Mycobiome diversity: high-throughput sequencing and identification of fungi. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordoni, E.; Ametrano, C.G.; Banchi, E.; Ongaro, S.; Pallavicini, A.; Bacaro, G.; Muggia, L. Integrated eDNA metabarcoding and morphological analyses assess spatio-temporal patterns of airborne fungal spores. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desprez-Loustau, M.-L.; Aguayo, J.; Dutech, C.; Hayden, K.J.; Husson, C.; Jakushkin, B.; Marçais, B.; Piou, D.; Robin, C.; Vacher, C. An evolutionary ecology perspective to address forest pathology challenges of today and tomorrow. Annals of Forest Science 2016, 73, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmeier, A.; Spetik, M.; Frejlichova, L.; Pecenka, J.; Cechova, J.; Stefl, L.; Simek, P. Survey of the Trunk Wood Mycobiome of an Ancient Tilia × europaea L. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N. Endophytic fungi in forest trees: are they mutualists? Fungal Biology Reviews 2007, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhonen, E.; Blumenstein, K.; Kovalchuk, A.; Asiegbu, F.O. Forest Tree Microbiomes and Associated Fungal Endophytes: Functional Roles and Impact on Forest Health. Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.K.; Berglund, H.; Ovaskainen, O.; Jonsson, B.G.; Snäll, T.; Ottosson, E.; Jönsson, M. Fungal trait-environment relationships in wood-inhabiting communities of boreal forest patches. Functional Ecology 2024, 38, 1944–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.T.; Edman, M.; Jonsson, B.G. Colonization and extinction patterns of wood-decaying fungi in a boreal old-growth Picea abies forest. Journal of Ecology 2008, 96, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.-L.; Bonito, G.; Rojas, J.A.; Hameed, K.; Wu, S.; Schadt, C.W.; Labbé, J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Martin, F.; Grigoriev, I.V.; et al. Fungal Endophytes of Populus trichocarpa Alter Host Phenotype, Gene Expression, and Rhizobiome Composition. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2019, 32, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, M.; Ahlholm, J.; Sieber, T.N.; Hinneri, S.; Saikkonen, K. Fragmented environment affects birch leaf endophytes. New Phytologist 2007, 175, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtysik, A.; Unterseher, M.; Otto, P.; Wirth, C. Spatio-temporal dynamics of endophyte diversity in the canopy of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior). Mycological Progress 2013, 12, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrmark, K.; Bödeker, I.T.M.; Cruz-Martinez, K.; Friberg, H.; Kubartova, A.; Schenck, J.; Strid, Y.; Stenlid, J.; Brandström-Durling, M.; Clemmensen, K.E.; et al. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region – evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2012, 82, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols, Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, N.A.; Cavalcanti, A.R.O. Using NCBI BLAST. Current Protocols Essential Laboratory Techniques 2017, 14, 11.11–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babraham, B. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data.

- Větrovský, T.; Baldrian, P.; Morais, D. SEED 2: a user-friendly platform for amplicon high-throughput sequencing data analyses. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2292–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronesty, E. "Comparison of Sequencing Utility Programs". The Open Bioinformatics Journal 2013, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Ryberg, M.; Hartmann, M.; Branco, S.; Wang, Z.; Godhe, A.; De Wit, P.; Sánchez-García, M.; Ebersberger, I.; de Sousa, F.; et al. Improved software detection and extraction of ITS1 and ITS2 from ribosomal ITS sequences of fungi and other eukaryotes for analysis of environmental sequencing data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2013, 4, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, M.; Mann, J.; Chapman, T.; Thomas, F.; Whitton, C.; Floyd, R.; Abebe, E. Defining operational taxonomic units using DNA barcode data. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2005, 360, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nature Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A. F S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldrian, P.; Větrovský, T.; Lepinay, C.; Kohout, P. High-throughput sequencing view on the magnitude of global fungal diversity. Fungal Diversity 2022, 114, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloor, G.B.; Macklaim, J.M.; Pawlowsky-Glahn, V.; Egozcue, J.J. Microbiome Datasets Are Compositional: And This Is Not Optional. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenacre, M.; Martínez-Álvaro, M.; Blasco, A. Compositional Data Analysis of Microbiome and Any-Omics Datasets: A Validation of the Additive Logratio Transformation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O. Diversity and Evenness: A Unifying Notation and Its Consequences. Ecology 1973, 54, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.D. Rarefaction, Alpha Diversity, and Statistics. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. Distance-Based Tests for Homogeneity of Multivariate Dispersions. Biometrics 2006, 62, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecology 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, M.; Wiese, S.; Warscheid, B. Networks. In Data Mining in Proteomics: From Standards to Applications, Hamacher, M., Eisenacher, M., Stephan, C., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; pp. 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Krah, F.-S.; Bässler, C.; Heibl, C.; Soghigian, J.; Schaefer, H.; Hibbett, D.S. Evolutionary dynamics of host specialization in wood-decay fungi. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2018, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, P.; Junninen, K.; Edman, M.; Kouki, J. Assemblage composition of fungal wood-decay species has a major influence on how climate and wood quality modify decomposition. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2017, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Poorter, L.; Kuramae, E.E.; Sass-Klaassen, U.; Leite, M.F.A.; Costa, O.Y.A.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; van Hal, J.; Goudzwaard, L.; et al. Stem traits, compartments and tree species affect fungal communities on decaying wood. Environmental Microbiology 2022, 24, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menkis, A.; Redr, D.; Bengtsson, V.; Hedin, J.; Niklasson, M.; Nordén, B.; Dahlberg, A. Endophytes dominate fungal communities in six-year-old veteranisation wounds in living oak trunks. Fungal Ecology 2022, 59, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cregger, M.A.; Veach, A.M.; Yang, Z.K.; Crouch, M.J.; Vilgalys, R.; Tuskan, G.A.; Schadt, C.W. The Populus holobiont: dissecting the effects of plant niches and genotype on the microbiome. Microbiome 2018, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ding, C.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q.; Huang, R.; Su, X. Endophytic Communities of Transgenic Poplar Were Determined by the Environment and Niche Rather Than by Transgenic Events. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, C.F.J.; Moyo, P.; Halleen, F.; Mostert, L. Phaeoacremonium species diversity on woody hosts in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 2018, 40, 26–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travadon, R.; Lawrence, D.P.; Rooney-Latham, S.; Gubler, W.D.; Wilcox, W.F.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Baumgartner, K. Cadophora species associated with wood-decay of grapevine in North America. Fungal Biology 2015, 119, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spetik, M.; Pecenka, J.; Stuskova, K.; Stepanova, B.; Eichmeier, A.; Kiss, T. Fungal Trunk Diseases Causing Decline of Apricot and Plum Trees in the Czech Republic. Plant Disease 2023, 108, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Mostert, L.; Crous, P.W.; Fourie, P.H. Novel Phaeoacremonium species associated with necrotic wood of Prunus trees. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 2008, 20, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiroff William, A.; Carrell Alyssa, A.; Klingeman Dawn, M.; Dove Nicholas, C.; Muchero, W.; Veach Allison, M.; Wahl, T.; Lebreux Steven, J.; Webb Amber, B.; Peyton, K.; et al. Seasonality and longer-term development generate temporal dynamics in the Populus microbiome. mSystems 2024, 9, e00886–00823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-P.; Lin, Y.-F.; Liu, Y.-C.; Lu, M.-Y.J.; Ke, H.-M.; Tsai, I.J. Spatiotemporal dynamics reveal high turnover and contrasting assembly processes in fungal communities across contiguous habitats of tropical forests. Environmental Microbiome 2025, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Lentendu, G.; Hoppe, B.; Jariyavidyanont, K.; Arnstadt, T.; Baber, K.; Otto, P.; Kellner, H.; Hofrichter, M.; et al. Determinants of Deadwood-Inhabiting Fungal Communities in Temperate Forests: Molecular Evidence From a Large Scale Deadwood Decomposition Experiment. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, B.; Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Kahl, T.; Bauhus, J.; Arnstadt, T.; Hofrichter, M.; Buscot, F.; Krüger, D. Linking molecular deadwood-inhabiting fungal diversity and community dynamics to ecosystem functions and processes in Central European forests. Fungal Diversity 2016, 77, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscox, J.; Savoury, M.; Müller, C.T.; Lindahl, B.D.; Rogers, H.J.; Boddy, L. Priority effects during fungal community establishment in beech wood. The ISME Journal 2015, 9, 2246–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.L.; Weatherhead, E.; Koide, R.T. The potential saprotrophic capacity of foliar endophytic fungi from Quercus gambelii. Fungal Ecology 2023, 62, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, L.C.; Schilling, J.S.; Menke, J.; Groenhof, E.; Kennedy, P.G. Ecological and functional effects of fungal endophytes on wood decomposition. Functional Ecology 2018, 32, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanney, J.B.; Kemler, M.; Vivas, M.; Wingfield, M.J.; Slippers, B. Silent invaders: the hidden threat of asymptomatic phytobiomes to forest biosecurity. New Phytologist 2025, 247, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosner, J.; Pandharikar, G.; Tremble, K.; Nash, J.; Rush, T.A.; Vilgalys, R.; Veneault-Fourrey, C. Fungal endophytes. Current Biology 2025, 35, R904–R910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnel, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Krah, F.-S.; Piepenbring, M.; Scheepens, J.F.; Hollert, H.; Johann, S.; Meyer, N.; Bässler, C. Toward harnessing biodiversity–ecosystem function relationships in fungi. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2025, 40, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peay, K.G.; Kennedy, P.G.; Talbot, J.M. Dimensions of biodiversity in the Earth mycobiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2016, 14, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Dsouza, M.; Lou, J.; He, Y.; Dai, Z.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J.; Gilbert, J.A. Geographic patterns of co-occurrence network topological features for soil microbiota at continental scale in eastern China. The ISME Journal 2016, 10, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toju, H.; Peay, K.G.; Yamamichi, M.; Narisawa, K.; Hiruma, K.; Naito, K.; Fukuda, S.; Ushio, M.; Nakaoka, S.; Onoda, Y.; et al. Core microbiomes for sustainable agroecosystems. Nature Plants 2018, 4, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Montoya, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Chen, L.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.B.; et al. Co-occurrence networks reveal more complexity than community composition in resistance and resilience of microbial communities. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagami, Y.; Matsuda, Y. Forest types matter for the community and co-occurrence network patterns of soil bacteria, fungi, and nematodes. Pedobiologia 2024, 107, 151004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordén, B.; Andreasen, M.; Gran, O.; Menkis, A. Fungal diversity in wood of living trees is higher in oak than in beech, maple or linden, and is affected by tree size and climate. Biodiversity and Conservation 2025, 34, 3609–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

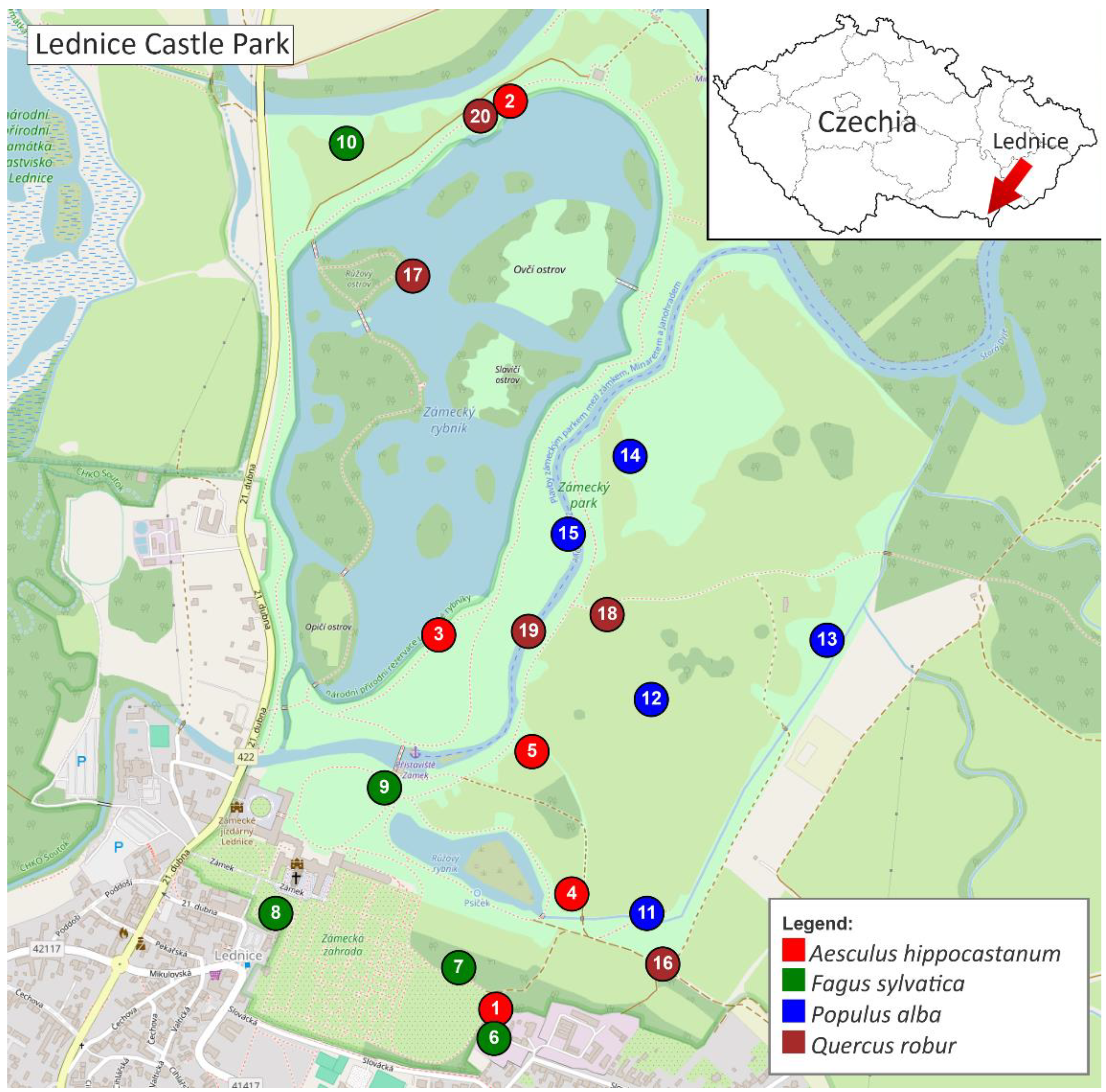

| No. | Species | GPS coordinates | Tree age estimate* [years] | Stem diam.** [cm] | Stem circumference** [cm] |

| 1 | Aesculus hippocastanum | 48°47'58.1"N 16°48'35.6"E | 80 - 100 | 79 | 248 |

| 2 | Aesculus hippocastanum | 48°48'49.7"N 16°48'38.0"E | 80 - 100 | 75 | 236 |

| 3 | Aesculus hippocastanum | 48°48′19.1″N 16°48′32.1″E | 60 - 80 | 78 | 245 |

| 4 | Aesculus hippocastanum | 48°48'04.7"N 16°48'42.3"E | 100 - 120 | 111 | 349 |

| 5 | Aesculus hippocastanum | 48°48'12.9"N 16°48'38.8"E | 100 - 120 | 89 | 280 |

| 6 | Fagus sylvatica ʻAtropuniceaʼ | 48°47'56.4"N 16°48'35.5"E | ≈ 150 | 114 | 358 |

| 7 | Fagus sylvatica ʻAtropuniceaʼ | 48°48'00.5"N 16°48'32.4"E | 150 - 200 | 136 | 426 |

| 8 | Fagus sylvatica ʻAtropuniceaʼ | 48°48'03.6"N 16°48'16.4"E | ≈ 150 | 125 | 393 |

| 9 | Fagus sylvatica ʻAtropuniceaʼ | 48°48'10.7"N 16°48'25.9"E | ≈ 150 | 109 | 343 |

| 10 | Fagus sylvatica ʻAtropuniceaʼ | 48°48'47.9"N 16°48'22.6"E | 150 - 200 | 121 | 381 |

| 11 | Populus alba | 48°48'03.4"N 16°48'48.8"E | 80 - 100 | 117 | 367 |

| 12 | Populus alba | 48°48'15.9"N 16°48'49.2"E | 60 - 80 | 87 | 273 |

| 13 | Populus alba | 48°48'19.3"N 16°49'04.6"E | 60 - 80 | 80 | 251 |

| 14 | Populus alba | 48°48'29.9"N 16°48'47.4"E | ≈ 100 | 120 | 377 |

| 15 | Populus alba | 48°48'25.4"N 16°48'42.0"E | 100 - 120 | 133 | 418 |

| 16 | Quercus robur | 48°48'00.7"N 16°48'50.2"E | 150 - 200 | 157 | 493 |

| 17 | Quercus robur | 48°48'40.3"N 16°48'28.4"E | 150 - 200 | 129 | 405 |

| 18 | Quercus robur | 48°48'20.8"N 16°48'45.4"E | 150 - 200 | 153 | 480 |

| 19 | Quercus robur | 48°48'19.8"N 16°48'38.5"E | 150 - 200 | 163 | 512 |

| 20 | Quercus robur | 48°48'48.9"N 16°48'37.1"E | 150 - 200 | 148 | 465 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).