1. Introduction

Due to several factors, Emerging Infectious Diseases (EIDs) have been increasingly threatening trees in agro-forestry and urban ecosystems [

1] thus posing a growing worldwide problem over the last decades [

2]. Over the centuries, the main cause of the spread of EIDs has been the introduction of alien pathogens into new geographic areas mainly due to the increase in international trade [

3]. However, other factors, such as climate change, also play a key role in the evolutionary and adaptation processes involved in the expansion of pathogens toward new favorable areas. Furthermore, climate change may increase plant susceptibility to infection, thus becoming new hosts of pathogens previously considered less aggressive [

4].

Globalization has certainly favored the spread of previously geographically isolated plant pathogens [

3], also favoring their hybridization with related species (and/or new introduced species) in new environments with different and/or wider host ranges than the parental species [

5], i.e., by the acquisition of novel traits of virulence from other species through horizontal gene transfer. The EIDs can be caused by a multitude of factors, among which, the most relevant are: i) the emergence of new virulent strains or species); ii) new vector-pathogen associations; iii) the introduction of new crops and cultivation practices (e.g., the global use of intensively managed forest plantations of non-native species or of a small number of clones of the same species); v) latent or cryptic plant pathogens [

4]. Cryptic plant pathogens are microorganisms sharing a strong resemblance or morphologically indistinguishable from recognized non-harmful species but possess hidden or unrecognized characteristics that can abruptly cause severe and unforeseen diseases [

6,

7]. Traditionally, host-microbe interactions have been examined primarily from the perspective of disease development and pathogenesis [

7]. However, it is now recognized that various organisms, such as plant endophytes, initially classified as widely distributed nonpathogenic species with generalist characteristics, are including groups of species established and adapted to new hosts or environments [

2,

8,

9].

There are many examples of endophytic fungi commonly isolated from asymptomatic plants that, under changed environmental conditions and/or various stressors altering the host physiology, can evolve as necrotrophic pathogens [

10,

11,

12]. Emerging pathogens characterized by a considerable latency stage are usually difficult to identify without advanced detection methods [

13,

14]. Fungal trunk diseases are classic examples of a very diverse group of microorganisms including well-studied endophytes and latent pathogens of woody plants that typically cause diseases associated with some type of stress [

15]. The species belonging to the

Botryosphaeriaceae family are among the most aggressive pathogens commonly described as endophytic fungi; they are ubiquitous and occur on a variety of plant hosts causing dieback and canker diseases [

16]. Some are also capable of producing several phytotoxins as observed for example in some strains of

Diplodia corticola [

17].

The aim of the present study is to identify the causal agents of the sudden decline of holm oak plants (Quercus ilex L., 1753), which was first observed in 2016 in some woods of the Salento Peninsula in the Apulia Region of Italy. Following inspections in woods affected by canopy decline, cankers, and subcortical necrosis, sampling and isolations were carried out from symptomatic holm oak branches and trunks in a variety of locations in the Salento Peninsula. Following the fungal isolation, the most representative isolates were morphologically and molecularly characterized and used in pathogenicity tests on artificially infected young holm oak plants to demonstrate Koch’s postulates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Visual Inspection of Trees, Sampling and Isolation

Field surveys were carried out in the spring-summer period in seven woodlands of the Salento Peninsula (Province of Lecce, Apulia Region, Italy) (

Table 1) affected by canopy decline, cankers, and subcortical necrosis (

Figure 1). The annual pluviometric data for the past 10 years were taken for each woodland by using the geographical coordinates from Visual Crossing Weather Data database (

https://www.visualcrossing.com/weather-data) and were analysed to assess the annual average precipitation for each woodland and the overall mean for all sites. Six symptomatic plants were selected for each woodland and representative sections of symptomatic branches or trunks were taken for each plant and used for fungal isolation. The samples were superficially sterilized by immersing them for 1 min in a water solution of sodium hypochlorite at 2% of active chlorine, then samples were washed in 70% ethanol for 30 sec, rinsed in sterile distilled water 3 times, and placed to dry in aseptic conditions. The bark was removed with a sterile scalpel from the sterilized branches showing discoloration and necrosis of the subcortical layer, also in depth. From the margin of symptomatic areas, small pieces of inner bark and xylem tissues (about 3-4 mm) were taken and plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) in Petri dishes amended with antibiotics (streptomycin 250 µg/mL and ampicillin 100 µg/mL). The plates were incubated at 24±2°C for 5 days in the dark. All growing colonies were transferred onto fresh PDA plates without antibiotic. To purify fungal colonies, the monoconidial and/or monoiphal culture method was used. Briefly, a small amount of conidia and/or mycelium biomass was scraped from 7-day-old fungal colonies and suspended in 10 ml of distilled water. The solution was vortexed for 30 s at high speed and filtered through four layers of sterile gauze, a drop (10 µl) of conidial or mycelium fragments suspension was inoculated on Water-Agar (WA) and incubated at 24±2°C for 24-48 hours in the dark. The axenic fungal colonies were obtained by taking single germinated conidia or a fragment of germinated hyphal tips, transferred onto PDA, and incubated at 24±2°C in the dark for 1 week. Among the pure isolated colonies, based on their macroscopic and microscopic characteristics, three of the most representative fungal colonies were subjected to further taxonomic investigations.

2.2. Morphological and Molecular Identification of the Fungal Isolates

The fungal isolates were subjected to further observation of the main morpho-cultural characteristics (growth rate, colour, structure of the mycelium, production of diffusible pigments) at different temperatures and on different substrates. Discs (Ø 6 mm) of mycelium were taken from the margin of 4-day-old colonies and placed in the centre of Petri dishes (Ø 90 mm) containing a range of substrates: Carrot Agar (CA), Corn Meal Agar (CMA), Malt Extract Agar (MEA), PDA or Water Agar (WA). The plates were then incubated in the dark at three different temperatures: 18±2°C, 24±2°C and 30±2°C. The diameters of the colonies were assessed after 1, 2 and 4 days of incubation, while the morphology of the colonies was assessed after 7 and 14 days [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Three strains were selected as the most representative based on macroscopic observations and subjected to further investigation. These strains were unable to produce the forms of the spores during a conventional cultivation on PDA, even after many days of incubation. For this purpose, agar plugs with mycelium were transferred onto agarised media poor in nutrients (10-time diluted PDA), incubated at 24±2°C, and, after 5 days, the fungal colonies were exposed to UV light (320 nm of wavelength) for 1 min per day. Isolated coded as QLE1 and QLE2, after 7 and 14 days respectively, developed pycnidia at the edges of the plates embedded between agar and fungal mycelium. Pycnidia and conidia were sampled from each plate and observed under a light-microscope, analysing the shape and dimensions of each structure. The pictures were acquired by an Olympus microscope (mod. BH-2) and a Zeiss stereomicroscope (Stemi 2000-C). The dimension of the conidia was assessed by using the measuring eyepiece of the microscope with a magnification of 400-1000x, and measuring at least 10 conidia per each fungal isolate.

2.3. Pathogenicity Tests

To evaluate the pathogenicity and virulence of the three selected fungal isolates, preliminary biological tests were carried out on 2-year-old potted holm oak grown in plastic pots filled with a soil-peat mixture (2:1) (Quercus ilex L., 1753). To promote the infectious process and the subsequent development of symptoms, for each fungal isolate, nine plants (3*9 plants) and nine control plants were stressed placing them in conditions of root asphyxia by dipping in water for 7 days, followed by a period of 5 days of dryness in a screen house under natural light condition (Temperature 28°C, and humidity <45%). The inoculation area (about 30 cm above the root collar) was surface disinfected on the bark with 70% ethanol, then a portion of the bark was removed with a sterile cork borer (Ø 6mm) and then a disk of fungal mycelium (Ø 6mm), taken from the margin of a 5-day-old PDA culture, was placed in contact with the wood. The inoculation point, including the agar disk, was covered with cotton wool soaked in sterile distilled water and then with a layer of parafilm to preserve moisture. As a negative control, the plants were subjected to the same treatment, but using an agar disk of the same medium without fungal mycelium. The surveys were carried out 40 days after inoculation, at the appearance of slight foliar symptoms on the inoculated plants. To this end, the inoculation points were revealed by removing the parafilm and cotton wool and with a sharp blade starting from the inoculation point downwards and upwards. The cortex was removed in order to reveal any subcortical discoloration/necrosis, the extension of which was appropriately measured and analysed. The same protocols reported in the previous two paragraphs were followed to isolate the fungal pathogens from the symptomatic tissues and characterise the pathogens.

2.4. Molecular Characterization of the Isolates

The most aggressive fungal isolates capable of producing symptoms like those observed in nature were subjected to molecular characterization. To this aim, the genomic DNA was isolated from the fungal mycelium (200 mg) collected from 7-day-old inoculated PDA plates. The mycelium was then transferred into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes in which was added 500 μL of extraction buffer (0.1 MNaCl, 0.5M Tris-HCI, pH 8.0, 5% sodium dodecyl sulphate) and approximately 0.2 grams of glass beads required for cell lysis. The tubes were then vortexed for 10 min at maximum intensity. To facilitate the lysis, the tubes were placed at -30°C for 15 min, and subsequently centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 RPM, then 200 μL of the supernatant was collected. An equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25: 24: 1) was added to the supernatant and then vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 RPM. Next, 250 μL of the aqueous phase was taken and 625 uL of isopropanol was added to the tube. Subsequently, the tubes were kept at 2°C for 1 hour and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 RPM. The isopropanol was discarded, and the pellet deposited on the bottom of the tubes was washed with 70% ethanol, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 RPM. The supernatant was discarded, and the DNA pellets were left to dry at room temperature for 1 hour and finally resuspended in 50 μL of TE buffer at pH 8 and stored at 4°C or at -20°C for analysis. Through PCR analysis, the ITS and TEF-1α regions were amplified by using the pairs of primers ITS1 and ITS4 [

22] and EF1-688F and EF1-986R [

23], respectively. The PCR reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 μL containing: 6.5 μL of H

2O; 2 μL of each primer; 12.5 μL of PCR Master Mix (Promega); 2 μL of DNA template.

The amplifications were performed using a T Gradient Thermal Cycler (Techne, mod. 512) under the following conditions: initial denaturation of 2 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation of 30 sec at 94°C, annealing of 30 sec at 55°C and extension 1 min at 72°C with a final extension of 5 min at 72°C.

The PCR products were loaded onto an agarose gel (50 mL TAE 1x, 0.4 g agarose, with the addition of 2μL of ethidium bromide) run at 80 V for 1 h and visualized by the Gel Doc 2000 transilluminator (Bio-Rad).

All the obtained ITS and TEF-α amplicons were first purified using the NucleoSpin extract II purification kit (Macherey-Nagel) and sent for sanger sequencing at Eurofins Genomics. The nucleotide sequence of each isolate was then compared with those present in the GenBank database using the "Nucleotide BLAST" tool (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in order to verify the similarity with sequences already present in the database (similarity percentages varying from 99 to 100%).

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

Merged ITS and TEF-1 α nucleotide sequences were aligned, corrected, and analysed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA X) software together with reference sequences downloaded from GenBank (

www.ncbi.nlm.gov), utilizing as outgroups a strain of

Lasiodiplodia mediterranea and

Xylaria hypoxylon (

Table 1). After the alignment and the exclusion of incomplete portions from both ends, using the same software, the most suitable models for the creation of the dendrogram and subsequently to carry out the phylogenetic analysis of the aligned sequences using the maximum statistical method were analysed. The maximum likelihood model (MLM) was used to evaluate the robustness of the tree obtained by setting the bootstrap number to 1000 replicates using the parameter model Tamura 3 and Gamma distributed function, with 5 discrete Gamma Categories, and Gaps/Missing data treatment as complete deletion.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Rainfall data were first subjected to a normality test. Subsequently, significant differences were assessed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey post hoc test for multiple comparisons, employing a 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05).

Data from pathogenicity tests were analysed by nonparametric tests comparing the cumulative distributions of the dataset, significant differences were determined by the two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with 95% of confidence level (P < 0.05).

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA,

www.graphpad.com.

4. Discussion

Emerging infectious plant diseases have complex causes related to the current dramatic global-scale changes in climate, economy, and human behaviour [

4]. Consider that biological invasion, a generally human-mediated event linked to economic growth and climate change, provides multiple opportunities for the introduction and spread of alien pathogens [

3]. In the last century alone, the range of the distribution of many plant pathogens has been artificially extended beyond the natural limits, causing enormous ecosystems disturbances and serious socio-economic impacts. The factors determining the emergence of the disease are often multifaceted and their effects should generally be considered and studied in relation to their possible multiple interactions [

31].

The emergence of new diseases, latent or cryptic, or caused by fungal pathogens that colonize new areas due to climate change, is a recent phenomenon of particular concern. In Italy as well as in the rest of Europe increasingly frequent reports of tree decline in oak forests have been recorded and a range of oak pathogens, for example,

Armillaria spp.,

Cephalosporium spp.,

Cladosporium spp.,

Cylindrocarpon spp.,

Diplodia spp.,

Biscogniauxia mediterranea (

Hypoxylon mediterraneum),

Phoma cavae, Phomopsis quercina, Sporotrix spp.,

Phytophthora spp. were found to be associated with this decline [

26,

32,

33,

34,

35]. It is not yet clear whether the disease development in many of these cases is primarily caused by emerging pathogens, as for example found in Italy for

Diplodia corticola and

Phytophthora cinnamomi on declining holm oak in Caprera Island (Sardinia) [

26], and in the Salento Peninsula (Apulia) [

36], or whether tree decline is due to physiological stresses caused by climate change, as in the case of the Lucanian Apennine (Basilicata Region) in Italy [

37]. In most cases, the increase in these reports derives from the negative interaction of both factors, phytopathogens and environmental stresses [

4]. On the one hand, environmental stress weakens the plants’ natural defences and can create conditions favourable to phytopathogens, increasing the likelihood of plant health problems. At the same time, phytopathogens may weaken the plants' natural resistance, making them more vulnerable to the adverse effects of environmental stresses such as extreme temperatures, drought, or excessive moisture.

In this work, following recent reports of holm oak (Quercus ilex) declining in woods of the Salento Peninsula (Apulia Region of Italy), we carried out several surveys, samplings, and fungal isolations from seven representative woodlands of the interested area. From the collected samples, fungal colonies belonging to the Botryosphaeriaceae family were the most frequently isolated.

Three isolates, coded as QLE1, QLE2, QLE3, were found as the most representative fungal morphotypes. Experimental tests were carried out to investigate the main morphological characteristics which allowed the identification of the three isolated fungi in two genera: two isolates belong to the genus Diplodia, and one to the genus Neofusicoccum. A careful microscopic analysis of the multiplication/reproduction structures of these isolates confirmed the characteristics of the species described by Phillips et al. (2013).

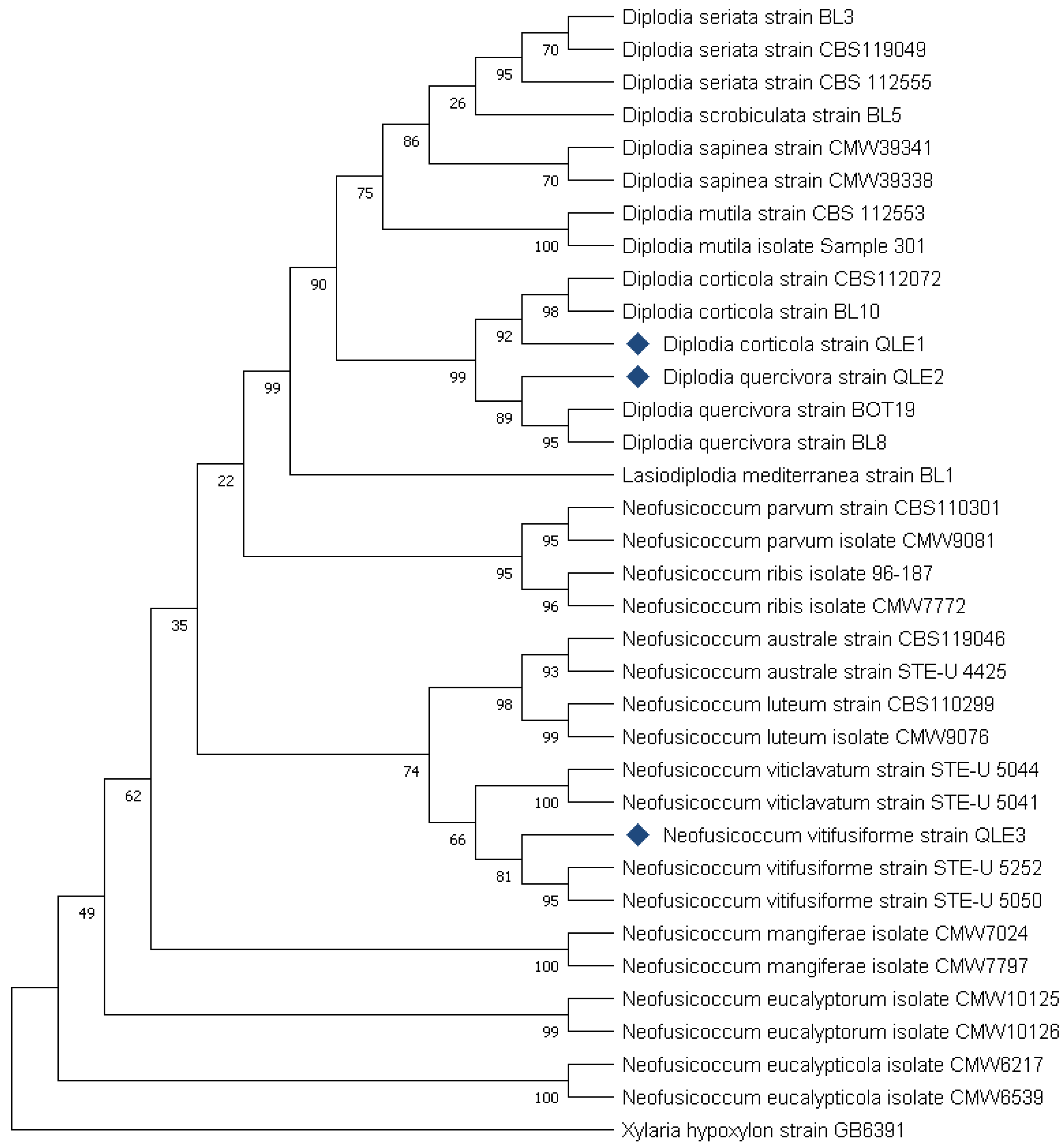

For the molecular analysis, the genomic DNA was extracted, subsequently, ITS regions and TEF-1α gene were amplified, sequenced, and processed. The result of the alignment of the sequences revealed the identity of fungal isolates in three different species: i) Diplodia corticola isolate QLE1, ii) Diplodia quercivora isolate QLE2 and iii) Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme isolate QLE3.

The identification was also confirmed by the phylogenetic analysis which ascribed the isolated species in the respective clades and therefore the amplicons resulted closely related to strains of the same species already described and deposited in the GenBank database (https: //

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

Preliminary, pathogenicity tests have shown that the three fungal strains isolated from holm oak (Q. ilex) are able to generate severe disease symptoms on artificially inoculated healthy plants. Furthermore, in line with Koch's postulates, the fungal strains were re-isolated at the conclusion of the tests and their morphological characteristics coincided with those of the initially inoculated strains.

Diplodia corticola isolate QLE1 and D. quercivora QLE2 proved to be particularly aggressive, indeed, 40 days after inoculation they produced intense subcortical browning and necrosis and severe leaf margin necrosis, while Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme isolate QLE3 proved to be less aggressive, but still capable of causing subcortical alterations and leaf marginal necrosis.

Diplodia corticola is a fungal species already known and described in Italy as a causal agent of decay of holm oak woods [

26], whereas

Diplodia quercivora, although already found as a pathogen on

Quercus spp. in other countries [

25,

28,

29], based on our information, our present study reports this species for the first time as a pathogen on holm oak in Italy.

As regards

Neofusiccocum vitifusiforme, this species was described in association with other

Botryosphaeriaceae on

Quercus suber declining forests in Algeria [

30], and, to the best of our knowledge, our study represents the first report of this species as a potential oak pathogen in Europe.

The interaction between

Botryosphaeriaceae and forest plants reveals a complex nature in which the infectious entity, the host, the environment and their interaction with other microorganisms and organisms, such as insect pests, may be equally important [

16]. Some species of these fungi are pathogens that can cause serious diseases in forest plants. These infections can cause severe damage to the plants’ foliage, branches, and stems, leading to reduced growth, premature defoliation, and, in severe cases, even plant death. In some cases, the infections can also weaken the plant and make it more susceptible to insect damage and/or other diseases. However, not all species of

Botryosphaeriaceae are pathogens. The transition from a non-pathogenic to a pathogenic stage in endophytic fungi may be due to alterations in the host physiology (plant stresses or mechanicals damage), and/or environmental changes or stressors (pollution, drought, climate change, etc.) [

11,

12]

Future research will be aimed at better studying the distribution of these fungal species in declining woods and clarifying their role in depth as well as their possible interaction with other oak pathogens, pests and environmental stresses. For N. vitifusiforme, in particular, further studies will also be important to better understand and evaluate its pathogenicity.

5. Conclusions

Forest decline phenomena have a complex origin involving several biotic and abiotic factors (infections by multiple pathogens, attacks by insect pests, drought, nutrient imbalances, climate change and air pollution). Identifying new declining forest factors may be critical for their prevention and management.

With regard to pathogens, it is important to conduct systematic surveys of forests and analyse the collected samples using a range of tools such as culture-based techniques, microscopy, and molecular analysis (DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis). In this study, we isolated and identified two important and dangerous pathogens involved in declining holm oak stands in the Salento Peninsula of Italy: Diplodia corticola and Diplodia quercivora, the latter reported here for the first time as an oak pathogen in Italy. Furthermore, a third fungal species, Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme was identified and reported for the first time as a potential new pathogen of holm oaks in Europe. It was well known from the literature and demonstrated by our pathogenicity assay that the two Diplodia species are particularly aggressive on Quercus ilex and can also be dangerous for other oak species. In addition, N. vitifusiforme has never been reported as a pathogen on holm oak, or on any other oak species. Further investigations are needed to better clarify the biology, ecology, epidemiology and impact of these fungal species on oak wood ecosystems in order to set up adequate control strategies to protect our forests.

Figure 1.

Representative symptoms observed in analysed declining plants in holm oak forest. A-C, Cankers and subcortical necrosis; D-E, stunting and decline of young holm oak plants.

Figure 1.

Representative symptoms observed in analysed declining plants in holm oak forest. A-C, Cankers and subcortical necrosis; D-E, stunting and decline of young holm oak plants.

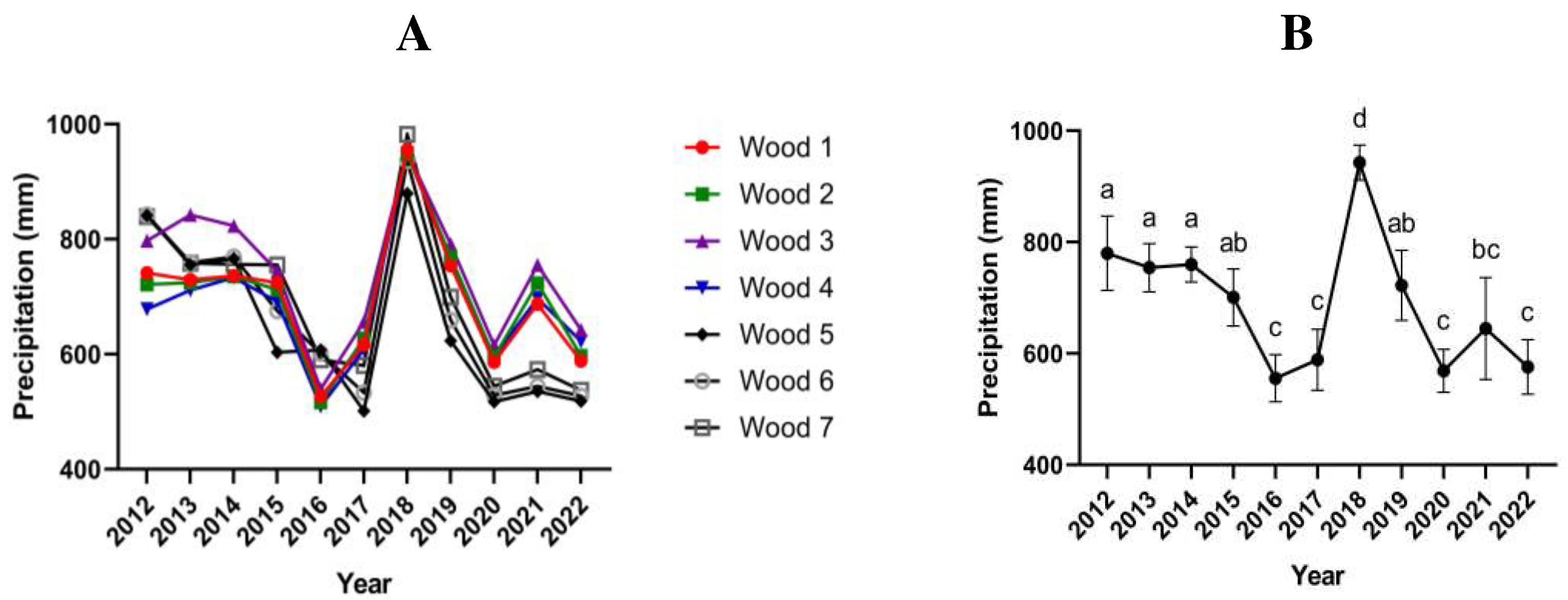

Figure 2.

A: Annual precipitation of the last 10 years in each woodland; B: Annual precipitation averages across all woodlands of the last 10 years. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test with a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

A: Annual precipitation of the last 10 years in each woodland; B: Annual precipitation averages across all woodlands of the last 10 years. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test with a 95% confidence interval.

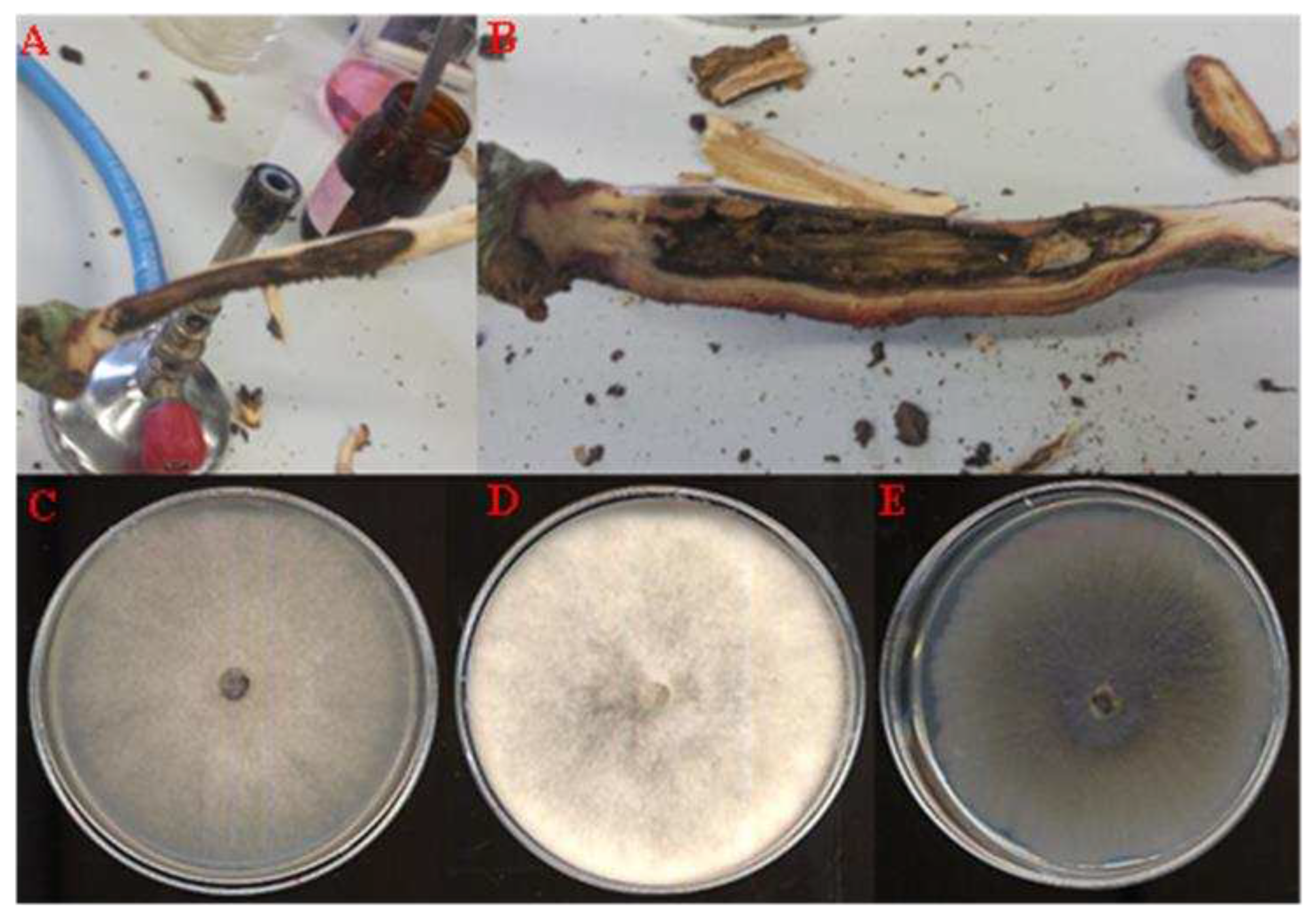

Figure 3.

A-B: Representative symptomatic oak holm samples used for the fungal isolation. C-E: Axenic culture obtained after 7 days of incubation on PDA for the most frequent fungal isolates QLE1 (C), QLE2 (D) and QLE3 (E).

Figure 3.

A-B: Representative symptomatic oak holm samples used for the fungal isolation. C-E: Axenic culture obtained after 7 days of incubation on PDA for the most frequent fungal isolates QLE1 (C), QLE2 (D) and QLE3 (E).

Figure 4.

Diplodia corticola isolate QLE1: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, 40x stereomicroscope pycnidia; D, 40x light microscope pycnidia; E, 100x light microscope conidia leakage; F, conidia under light microscopy at 800x.

Figure 4.

Diplodia corticola isolate QLE1: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, 40x stereomicroscope pycnidia; D, 40x light microscope pycnidia; E, 100x light microscope conidia leakage; F, conidia under light microscopy at 800x.

Figure 5.

Diplodia quercivora isolate QLE2: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, 20x stereomicroscope pycnidia; D, 20x light microscope pycnidia; E, 100x light microscope conidia leakage; F, conidia under light microscopy at 600x.

Figure 5.

Diplodia quercivora isolate QLE2: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, 20x stereomicroscope pycnidia; D, 20x light microscope pycnidia; E, 100x light microscope conidia leakage; F, conidia under light microscopy at 600x.

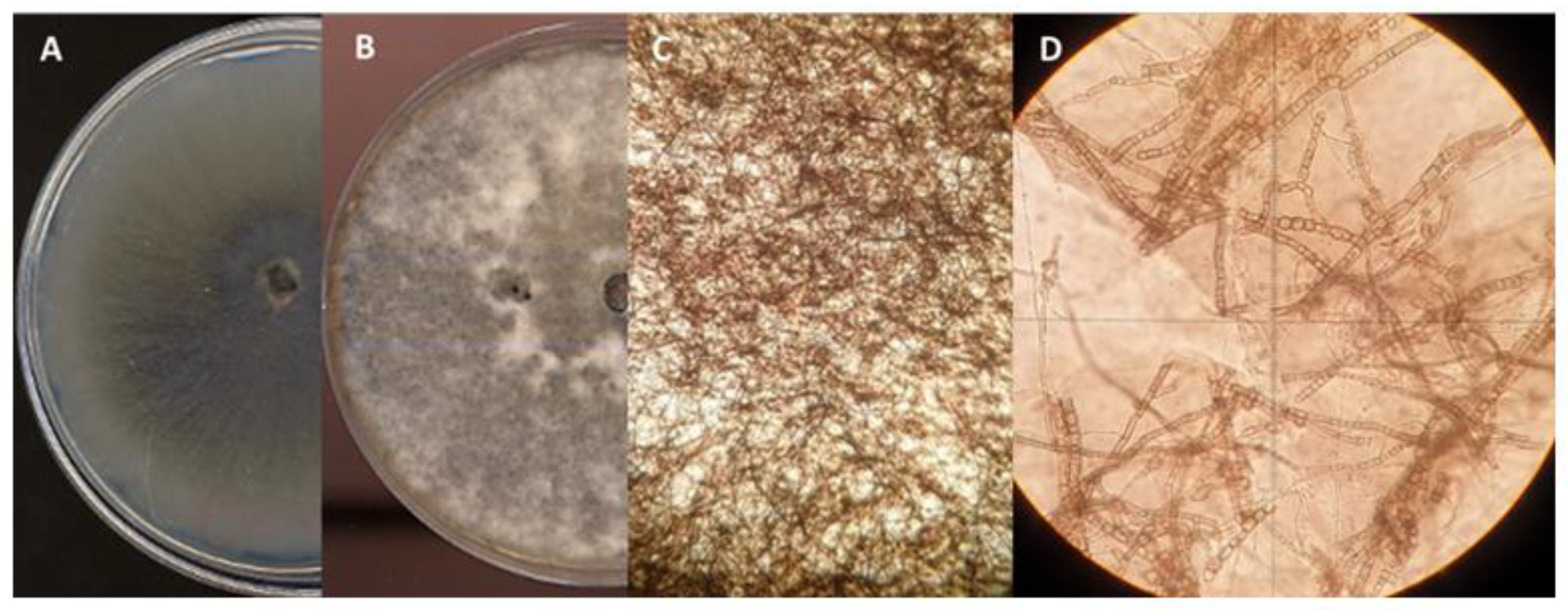

Figure 6.

Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme isolate QLE3: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, mycelium under light microscope at 40x; D, arthroconidia under light microscope at 400x.

Figure 6.

Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme isolate QLE3: A, 7-day PDA culture; B, 14-day PDA culture; C, mycelium under light microscope at 40x; D, arthroconidia under light microscope at 400x.

Figure 7.

Pathogenicity assays on young holm oak plants in controlled condition. Representative images of wood discoloration and necrosis extension in plants used for the pathogenicity assay at 40 dpi: A, non-inoculated control; B, plant inoculated with isolate QLE1; C, plant inoculated with isolate QLE2; D, plant inoculated with isolate QLE3. Typical leaf symptoms observed on inoculated plants with QLE1(E), QLE2 (F) and QLE3 (G). In the graph (H), the average and standard deviation of the length of the subcortical necrosis caused by the three strains on inoculated young holm oak at 40 dpi are reported. A nonparametric test comparing the cumulative distributions of the dataset was used, and significant differences were determined by the two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with 95% of confidence level (*, P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Pathogenicity assays on young holm oak plants in controlled condition. Representative images of wood discoloration and necrosis extension in plants used for the pathogenicity assay at 40 dpi: A, non-inoculated control; B, plant inoculated with isolate QLE1; C, plant inoculated with isolate QLE2; D, plant inoculated with isolate QLE3. Typical leaf symptoms observed on inoculated plants with QLE1(E), QLE2 (F) and QLE3 (G). In the graph (H), the average and standard deviation of the length of the subcortical necrosis caused by the three strains on inoculated young holm oak at 40 dpi are reported. A nonparametric test comparing the cumulative distributions of the dataset was used, and significant differences were determined by the two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with 95% of confidence level (*, P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic analysis conducted using the ITS and TEF-1 α sequences of the three isolates used in this study. At least two sequences belonging to the same species and at least two sequences for each species isolated from agricultural and forestry plants have been included as reference sequences. The two "outgroup" strains are represented by Lasiodiplodia mediterranea strain BL1 and Xylaria hypoxylon strain GB6391. The “bootstrap” values represent the result of 1000 replicates.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic analysis conducted using the ITS and TEF-1 α sequences of the three isolates used in this study. At least two sequences belonging to the same species and at least two sequences for each species isolated from agricultural and forestry plants have been included as reference sequences. The two "outgroup" strains are represented by Lasiodiplodia mediterranea strain BL1 and Xylaria hypoxylon strain GB6391. The “bootstrap” values represent the result of 1000 replicates.

Table 1.

Geographic specifications of woodland involved in this study.

Table 1.

Geographic specifications of woodland involved in this study.

| Wood # |

Wood name |

Municipalities |

Province |

Latitude (DD) |

Longitude (DD) |

| 1 |

Fraganite |

Muro Leccese |

Lecce, Italy |

40.099761 |

18.313251 |

| 2 |

Pozzo Mauro |

Muro Leccese |

Lecce, Italy |

40.098289 |

18.346773 |

| 3 |

Baia dei Turchi |

Otranto |

Lecce, Italy |

40.191555 |

18.463726 |

| 4 |

Maramonti |

San Cassiano |

Lecce, Italy |

40.052636 |

18.315900 |

| 5 |

Solicara |

Lecce |

Lecce, Italy |

40.435958 |

18.201963 |

| 6 |

Bosco Fiore |

Lecce |

Lecce, Italy |

40.385044 |

18.255363 |

| 7 |

Bosco San Biagio |

Calimera |

Lecce, Italy |

40.253310 |

18.303520 |

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers, hosts and species identity for all Botryosphaeriaceae used in the phylogenetic analyses.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers, hosts and species identity for all Botryosphaeriaceae used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Acession n. (GenBank) |

| Genus |

Species |

Strain |

Host |

Locality |

Note |

ITS |

TEF-1 α |

| Neofusicoccum |

vitifusiforme |

strain QLE3 |

Quercus ilex |

Italy |

isolated in this study |

OQ876772 |

OQ750144 |

| Neofusicoccum |

australe |

strain CBS119046 |

Rubus sp. |

Portugal |

/ |

DQ299244.1 |

EU017541.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

australe |

strain STE-U4425 |

Vitis vinifera |

South Africa |

/ |

AY343388.1 |

AY343347.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

luteum |

strain CBS110299 |

Vitis vinifera |

Portugal |

/ |

AY259091.1 |

AY573217.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

luteum |

isolate CMW9076 |

Malus x domestica |

New Zeland |

/ |

AY339257.1 |

AY339265.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

vitifusiforme |

strain STE-U5252 |

Vitis vinifera |

South Africa |

/ |

AY343383.1 |

AY343343.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

vitifusiforme |

strain STE-U5050 |

Vitis vinifera |

South Africa |

/ |

AY343382.1 |

AY343344.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

viticlavatum |

strain STE-U5044 |

Vitis vinifera |

South Africa |

/ |

AY343381.1 |

AY343342.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

viticlavatum |

strain STE-U5041 |

Vitis vinifera |

South Africa |

/ |

AY343380.1 |

AY343341.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

parvum |

strain CBS110301 |

Vitis vinifera |

Portugal |

/ |

AY259098.2 |

AY573221.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

parvum |

isolate CMW9081 |

Populus nigra |

New Zeland |

/ |

AY236943.1 |

AY236888.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

ribis |

isolate 96-187 |

Ribes rubrum |

Not known |

/ |

AF241177.1 |

AY236879.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

ribis |

isolate CMW7772 |

Ribes sp. |

USA |

/ |

AY236935.1 |

AY236877.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

mangiferae |

isolate CMW7024 |

Mangifera indica |

Australia |

/ |

AY615185.1 |

DQ093221.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

mangiferae |

isolate CMW7797 |

Mangifera indica |

Australia |

/ |

AY615186.1 |

DQ093220.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

eucalyptorum |

isolate CMW10125 |

Eucalyptus grandis |

South Africa |

/ |

AF283686.1 |

AY236891.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

eucalyptorum |

isolate CMW10126 |

Eucalyptus grandis |

South Africa |

/ |

AF283687.1 |

AY236892.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

eucalypticola |

isolate CMW6217 |

Eucalyptus rossi |

Australia |

/ |

AY615143.1 |

AY615135.1 |

| Neofusicoccum |

eucalypticola |

isolate CMW6539 |

Eucalyptus grandis |

South Africa |

/ |

AY615141.1 |

AY615133.1 |

| Lasiodiplodia |

mediterranea |

strain BL1 |

Quercus ilex |

Italy |

Outgroup Genera |

KJ638312.1 |

KJ638331.1 |

| Diplodia |

corticola |

strain QLE1 |

Quercus ilex |

Italy |

isolated in this study |

OQ876772 |

OQ750142 |

| Diplodia |

quercivora |

strain QLE2 |

Quercus ilex |

Italy |

isolated in this study |

OQ831537 |

OQ750143 |

| Diplodia |

corticola |

strain CBS112072 |

Quercus ilex |

Spain |

/ |

AY259108.1 |

JX894221.1 |

| Diplodia |

quercivora |

strain BOT19 |

Quercus suber |

Algeria |

/ |

MF535381.1 |

MF535391.1 |

| Diplodia |

corticola |

strain BL10 |

Quercus ilex |

Italy |

/ |

JX894191.1 |

JX894210.1 |

| Diplodia |

quercivora |

strain BL8 |

Quercus canariensis |

Tunisia |

/ |

JX894205.1 |

JX894229.1 |

| Diplodia |

scrobiculata |

strain BL5 |

Arbutus unedo |

Italy |

/ |

GU722102.1 |

JX894231.1 |

| Diplodia |

seriata |

strain BL3 |

Ulmus minor |

Italy |

/ |

JX894207.1 |

JX894232.1 |

| Diplodia |

mutila |

strain CBS112553 |

Vitis vinifera |

Portugal |

/ |

AY259093.2 |

AY573219.1 |

| Diplodia |

mutila |

isolate Sample301 |

Juglans regia |

Chile |

/ |

MW412902.1 |

MW574125.1 |

| Diplodia |

sapinea |

strain CMW39341 |

Cedrus deodara |

Montenegro |

/ |

KF574998.1 |

KF575028.1 |

| Diplodia |

sapinea |

strain CMW39338 |

Cedrus atlantica |

Serbia |

/ |

KF574999.1 |

KF575029.1 |

| Diplodia |

seriata |

strain CBS112555 |

Vitis vinifera |

Portugal |

/ |

AY259094.2 |

AY573220.1 |

| Diplodia |

seriata |

strain CBS119049 |

Vitis sp. |

Italy |

/ |

DQ458889.1 |

DQ458874.1 |

| Xylaria |

hypoxylon |

strain GB6391 |

isolated from soil |

Mexico |

Outgroup Order |

AM993138.1 |

AY327490.1 |