1. Introduction

The interest in the cultivation of pomegranate (

Punica granatum L.) in Italy has led the research to increase the knowledge about this crop, whose fruit is considered a functional product of great benefit from the organoleptic and nutraceutical point of view as well as for the possibility of pharmaceutical applications given the content of active molecules that reduce the risk of vascular diseases, coronary artery problems and canker mortality [

1,

2]. Among the bioactive compounds present in pomegranate juice, there are phenols and tannins such as punicalin, punicalagin, and ellagic acid; moreover, the varieties with red arils contain a large number of anthocyanins including cyanidin, delphinidin, pelargonidin, and the related glycosides with a strong antioxidant capacity [

3,

4,

5].

Some young pomegranate plants in central and southern Italy, the major cultivated areas together with the islands, have experienced phytosanitary problems that, in some cases, caused the loss of fruit production and plants [

6]. This disease, called “Pomegranate canker” or, more generically “Pomegranate decay”, shows progressively worsening conditions of the plant: the first symptoms are leaf chlorosis, and later, the plant shows the formation of cankers on the stem and branches with wood browning below the symptoms. The main fungi isolated from the symptomatic portions of pomegranate wood were:

Coniella granati, already been reported in Italy, Iran, Israel, Turkey, Greece and Spain [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] and

N. parvum (Pennycook & Samuels) Crous, Slippers and Phillips, already reported in Greece [

12], in Florida [

13] and in Italy where it was recently reported in an orchard in Lazio [

14].

N. parvum was also reported on other plants of agricultural interest including the grapevine, kiwifruit, and avocado [

15,

16,

17]. This fungus enters through wounds (e.g., pruning cuts or mechanical damage due to abiotic agents such as frost or hail). The infection causes browning of the bark on the trunk and branches and the discolouration of the wood underlying the affected areas, resulting in the general decay of the plant and subsequent die-off of the shoots. The fungus often causes significant cankers that can affect the whole plant [

14].

The wood decay often represents a disease complex due to the characteristic mixed infections [

18] and the simultaneous presence of several fungal species complicates the diagnosis. The traditional phytosanitary approach requires an initial culturing step, which excludes the detection of the biotrophic, endophytic species and may limit the detection of slow-growing fungi. As trunk pathogens cause mixed infections, it is important to characterize the composition of the species complex. In the last years, due to the growing power and reducing cost of the next generation sequencing technologies, the DNA metabarcoding analysis has been used extensively for the characterization of microbial communities [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) are the most predominant DNA barcode sequences used for fungal metabarcoding since they can be easily amplified and sequenced and they are highly represented in GenBank and other databases [

24,

25]. The Illumina MiSeq NGS technology is the most used in metabarcoding studies [

26], due to its high diversity coverage, high accuracy, low cost and availability of several consolidated data processing pipelines; however, due to the limited sequence lengths, it allows the sequencing of one of the ITS subregions. The choice of using either ITS1 or ITS2 for the best taxonomic resolution is still debated [

27,

28]. ITS2 shows some advantageous features: it is less variable in length, has no intron regions, is better represented in public databases, and has a longer portion of the sequence providing taxonomic information [

29]. This work aims to study and characterise the fungal flora present in diseased pomegranate wood through traditional phytosanitary analysis combined with an ITS metabarcoding analysis and to verify the disease involvement of the more frequently isolated fungi through a pathogenicity test. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study combining culturing and DNA-metabarcoding approaches to assess fungal pathogen diversity associated with pomegranate wood decay.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

Two pomegranate Italian orchards, both in the Lazio region, were monitored: Sermoneta (41.556459, 12.979830) and Pavona (41.742874, 12.603806). The soil of the Sermoneta orchard was classified predominantly as Haplic Luvisols (>75%), with Luvic Phaeozems (10–25%), while the Pavona orchard soil was classified as Haplic Phaeozems (25–50%), Luvic Phaeozems (10–25%), and Cambic Endoleptic Phaeozems (<10%) [

30]. Furthermore, the Lazio region experiences colder winter climatic conditions than southern Italy, where pomegranate cultivation is more successful [

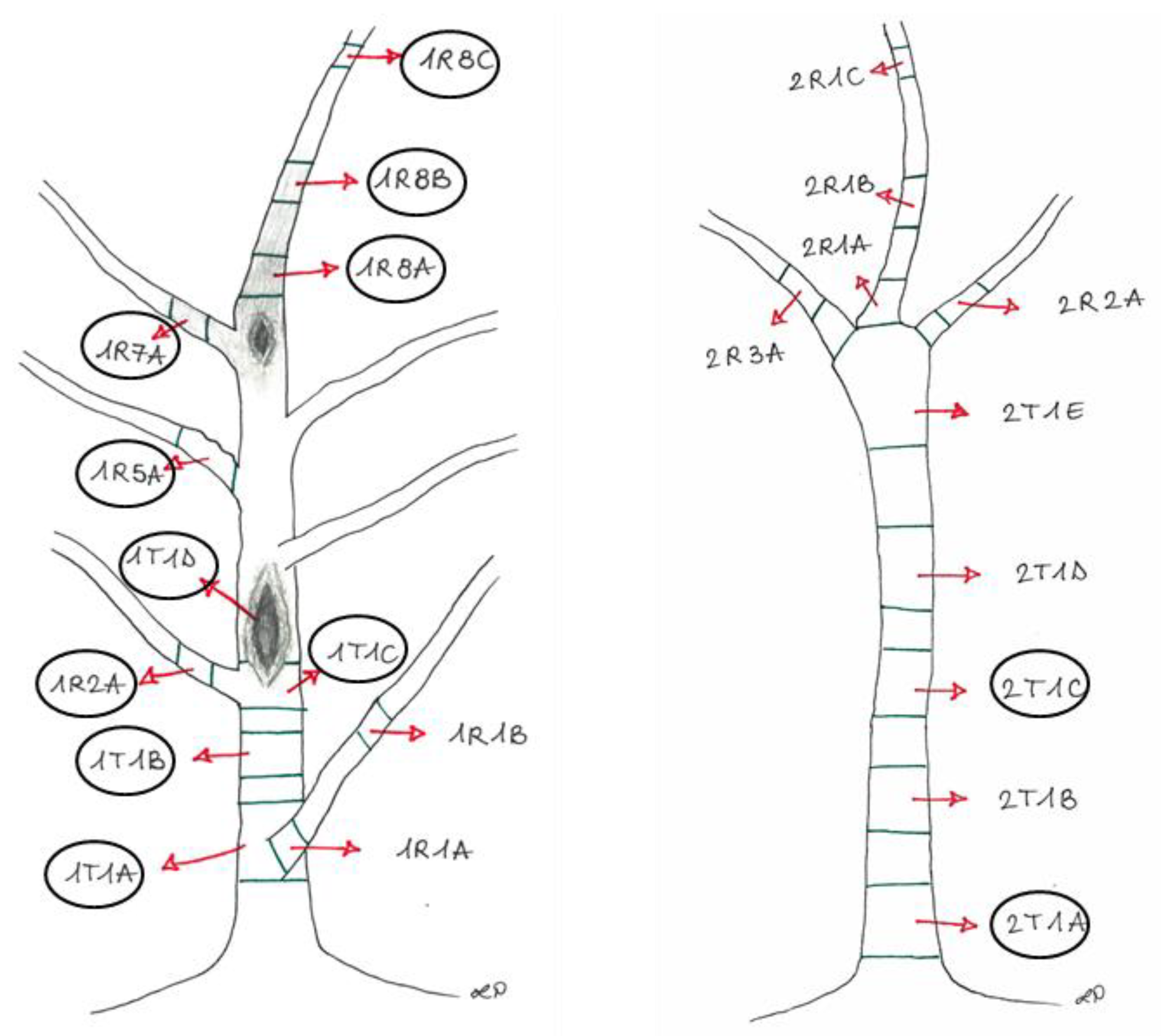

31]. Fifteen symptomatic plants obtained from both the orchards from 2017 to 2019 were transferred to the laboratory of the Research Centre for Plant Protection and Certification (CREA-DC, Roma) and analysed by isolation and morphological and molecular identification of the fungal flora. Two plants, showing the symptoms of pomegranate decay (identified as Plant 1 and Plant 2,

Figure 1), from the Pavona site (2018) were analysed by conventional approach (isolation and identification) and by the metabarcoding NGS tool. Plant 1 presented some cankers on the stem and some branches, subcortical browning of the wood, and yellowing; Plant 2 showed an extended canker on the whole trunk, with extended subcortical browning (

Figure 1).

The plants (stem and branches) were divided into sections (

Figure 2) representative of different asymptomatic and symptomatic wood tissues, from the trunks and the branches.

2.2. Fungal Isolation and Identification

Longitudinal and transversal sections of tissues sampled as described above were obtained aseptically; small portions between the healthy and symptomatic tissue were explanted from the browned wood and placed on the Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) culture medium amended with 100 µg/mL of streptomycin and ampicillin sodium salt antibiotic and incubated at 22°C until the development of the fungal colonies. The fungal identification was carried out based on the morphological features of the colonies and of the fruiting structures. The morphological identification was confirmed by the sequencing of the ITS region amplified with ITS4/ITS5 primers [

32] performed at BioFab Research laboratory (Rome, Italy). The sequences were blasted in the GenBank database by using the nBLAST search. The isolated and identified species were preserved in the fungal collection of CREA-DC (Rome).

2.3. DNA Extraction

The DNA from the fungal mycelium was extracted with the rapid protocol of Cenis [

33] starting from 100 mg of mycelium modified for plate-grown mycelium [

34]. Pomegranate wood was ground in liquid nitrogen; an aliquot of ground wood (about 100 mg) was used for DNA extraction performed with the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of purified DNA extracts were determined using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and DS-11 FX spectrophotometer (DeNovix Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) respectively.

2.4. Metabarcoding Analysis

A metabarcoding analysis was carried out on Plant 1 and Plant 2 from the Pavona pomegranate orchard to confirm the data derived from the isolation and identification of the fungal flora, and to have more information about the fungal communities in the asymptomatic and symptomatic wood tissues. The different samples were combined in 8 experimental units (

Table 1), 7 from Plant 1 and 1 from Plant 2.

DNA samples were amplified by PCR targeting the ITS2 region of the fungal rDNA using ITS3 and ITS4 primers [

32]. These primers were modified by the 5′ end Illumina overhang adapter sequences (34 and 35 nucleotides) and by different 5′-end identifier (index) sequences of 6 nucleotides generating 8 oligo pairs of unique tags (

Table S1). PCR was conducted for the 8 samples with each of the 8 newly designed primer pairs to test for variability in amplification success. Each sample was assigned a different forward/reverse index combination for sample-specific labelling..

The amplification reaction was performed following the protocol proposed by Miller

, et al. [

35]. The reaction mix contained 10 ng template DNA, 1× BioTaq PCR NH

4-based reaction buffer, 4 mM MgCl

2, 0.8 mM dNTP mix (Bioline, London, UK), 0.8 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 2.5 U BioTaqTM DNA polymerase (Bioline, London, UK), and 0.5 μM of each forward and reverse primers in a 25 μL reaction volume. For each sample, three PCRs were carried out at three different annealing temperatures:combining PCR products using a range of annealing temperatures reduces primer bond distortion and decreases the stochasticity of individual PCRs [

19]. The following cycling conditions were used for the amplification: initial denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50/53/56°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 30 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 2 min. The PCR products were visualised in 1% agarose gel electrophoresis using GelRed™ dye (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA). Purification of the amplicons was performed using the Isolate II PCR and Gel Kit (Bioline, London, UK). The cleaned PCR products were then quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and mixed in equimolar amounts (75 ng for each sample). A single sample, consisting of the pooled amplification products was sent to the BioFab Research laboratory (Rome, Italy). The sequencing was performed on the Illumina platform (Miseq) with a 2×300 paired-ends run and a reading depth of 100000 reads. The reads forward and reverse have been merged and filtered by quality (Q> 30). Subsequently, a demultiplexing of the sequenced sample was carried out obtaining the results of the 8 separate experimental units. Bioinformatic processing of the sequences was conducted using the USEARCH pipeline and UPARSE-OTU algorithm [

36].

The paired-end (PE) sequences were merged using the -fastq_mergepairs command. Next, PE reads were quality-filtered (maximum e-value: 1.0), trimmed 340 bp, dereplicated, and sorted by abundance (singletons removed). Chimaera detection and OTU (operational taxonomic unit) clustering at 97% sequence identity followed. The original sequences were then mapped to OTUs at the 97% identity threshold, generating separate OTU tables for prokaryotic and fungal communities.

The taxonomic affiliation of each OTU was assigned using the -syntax algorithm against the UNITE_all_eukaria database [

37] with an 80% confidence threshold. Sequencing depth was normalized across libraries, and the resulting OTU tables were used for downstream analyses.

2.5. Pathogenicity Test

Artificial inoculations were performed using the 5 fungal species isolated with higher incidence and belonging to the most represented

Genus in metabarcoding analysis (

N.

parvum, isolate ER 2123;

D. eres (Nitschke), isolate ER 2111;

D.

phaseolorum (Cooke & Ellis) Sacc., isolates ER 2126 and ER 2126;

D. rudis (Sacc.) Sacc., isolate ER 2127;

D.

foeniculina (Udayanga et al., 2014), isolates ER 2125 and ER 2128.

N.

parvum ER 2123 was used as a positive control since it is reported as a pathogen of pomegranate wood [

14].

The pathogenicity was evaluated through a test carried out on cut twigs and plants. The twigs were prepared in sections approximately 20 cm long, harbouring at least two buds between which were performed the inoculation. The inoculation area was previously surface sterilised with denatured ethyl alcohol.

Three inoculation procedures were performed.

First procedure: Detached pomegranate twigs at least one year old as described by Palavouzis

, et al. [

12]. The test was carried out with 5 mm diameter mycelium plugs taken from the margin of fungal colonies, about one week old, grown in purity on PDA medium. A 5 mm diameter disc of the bark was previously removed from the twigs with a cork borer to expose the cambium to the mycelium applied with a PDA plug. Then the twigs were placed in the dark in a humid chamber at room temperature to promote the infection (

Figure 3). After 3 days, when presumably the mycelium colonised the wood, the humid chambers were opened. The test was completed in 7 days post inoculation (DPI).

Second procedure: detached twigs of at least four years old placed in water were inoculated wounding the bark with a razor blade in a basipetal orientation exposing the youngest wood; then the strip of tissue was pulled back to place the PDA with the mycelium on the exposed xylem. The inoculation area was covered with a cotton disc soaked with 3 ml of sterile tap water, wrapped with tinfoil strips, and stuck with paper tape as shown in

Figure 4 [

38]. They were placed in water at 25°C with photoperiod 13 h of light (13/11) and weekly checked to change the water. After seven days tinfoil strips were removed. The test was completed in 90 DPI.

Third procedure. In vivo, plants were inoculated as described in the second procedure and placed outdoors in the nursery. After 30 days, when presumably the mycelium colonized the wood, the tinfoil strips and the paper tape were removed; The test was completed in 90 days.

At the end of these tests, the first layers of the bark were removed with a razor blade to show and measure the length of the browned area in the longitudinal direction of the twig (

Figure 5).

The tests were conducted in randomized blocks with four repetitions for procedures 1 and 2, and five repetitions for procedure 3. This was applied to each fungal isolate, as well as to the negative control (sterile PDA plugs) and the positive control.

Moreover, control isolations were carried out from the symptomatic areas to verify the Kock’s postulates.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data from the pathogenicity test were analysed using R software version 4.2.1 to perform a One-Way ANOVA, assessing significant differences in browning length (cm) among treatments to evaluate the virulence of the fungus compared to negative controls.

Before the ANOVA, normality was checked using shapiro.test function, while homoscedasticity and non-additivity were verified with bartlett.test and leveneTest functions, respectively, considering p > 0.05 as the threshold for homogeneity. The ANOVA was performed using the aov function, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test with Tukey HSD function to identify significant differences between treatment groups (p = 0.05). The ANOVA results were considered significant at p < 0.05 and highly significant at p < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Phytosanitary Analysis of Pomegranate Plants Affected by Decay

Plants exhibiting wood decay symptoms, including reduced growth, leaf yellowing, and reddening, were sampled. Their trunks and twigs displayed cortical cankers, some located above the collar and others extending along the entire trunk. In the early stages of the disease, before canker formation, the bark appeared darker, and the underlying cambium showed distinct darkening and damage.

Laboratory dissections revealed browned wood, particularly beneath the cankers, with necrosis spreading in both basipetal and acropetal directions. In cases of multiple cankers, browning could extend throughout the entire trunk.

Fungal isolations from 325 symptomatic tissues yielded 188 colonies. Morphological and DNA sequence analyses identified 11 distinct species (

Table 2).

N. parvum was detected at both the Pavona and Sermoneta sites but only in early autumn.

Diaporthe spp. and

Gliocladium spp. were more frequently isolated and exhibited a high incidence.

3.2. Metabarcoding Analysis

A fragment of the expected size (340 bp) was obtained from ITS2 amplification in all the samples investigated.

The dataset comprises 114,486 reads distributed across eight samples, with a total of 41 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) identified. Notably, all OTUs and samples contain nonzero counts with no missing data or singleton OTUs.

In terms of OTU abundance and distribution, none of the OTUs have a total count of one, meaning that all identified taxa are represented by multiple reads across samples. A total of 328 counts were recorded, with 44.5% (146 counts) being zero and 55.5% (182 counts) showing at least ten occurrences. This suggests a relatively balanced distribution of microbial taxa, although a portion of the OTUs remains rare across samples.

Regarding the core microbiome and ubiquity of OTUs, 13 OTUs (31.7%) are present in all samples, defining a core microbiome that is consistently detected across the dataset; 23 OTUs (56.1%) are detected in at least 50% of the samples, indicating a moderate level of species turnover across different sampling points.

The sample size and sequencing depth vary, with the smallest sample containing 3,749 reads and the largest 19,253 reads. The median sample size is 15,599 reads, while the mean is 14,310 reads, suggesting an overall well-balanced sequencing depth across samples. The lower quartile (14,171 reads) and upper quartile (19,157 reads) indicate that most samples fall within a reasonable range, minimising the risk of uneven sequencing depth affecting downstream analyses.

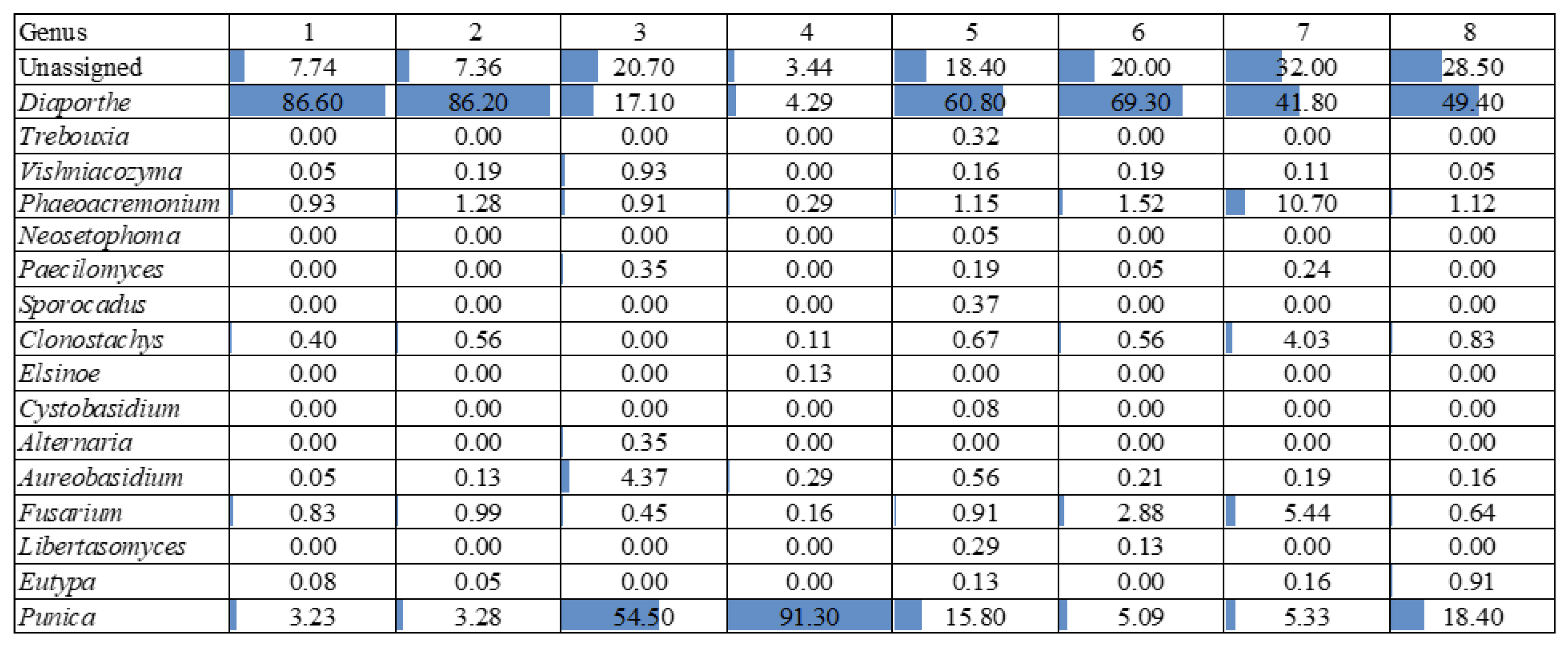

Based on

Figure 6, the most frequently occurring taxon across samples was

Diaporthe, which shows consistently high relative abundances, ranging from 17.10% to 86.60%. This genus dominates several samples, particularly in samples 1, 2, 5, and 6, where its relative abundance exceeds 60%.

Another notable taxon is Punica, which exhibits the highest relative abundance in sample 4 (91.30%) and sample 3 (54.50%), which were asymptomatic sections. In contrast, taxa such as Vishniacozyma, Phaeoacremonium, and Fusarium are present in lower proportions but show some variability across samples, with Phaeoacremonium reaching 10.70% in sample 7.

Regarding species richness, sample 7 (symptomatic section) appears to have the highest diversity, as it contains multiple taxa with substantial relative abundances, including Diaporthe (41.80%), Phaeoacremonium (10.70%), Fusarium (5.44%), and Clonostachys (4.03%). This indicates a more heterogeneous microbial community in this sample.

Conversely, samples 3 and 4 (asymptomatic sections) exhibited the lowest species richness, as it is overwhelmingly dominated by Punica (54.50% and 91.30%, respectively) and Diaporthe (17.10% and 4.29%, respectively), with other taxa either absent or present in very low amounts.

Overall, the results highlight a strong predominance of Diaporthe, variations in microbial community structure across samples, and a marked difference in species richness, with sample 7 exhibiting the highest diversity and sample 4 the lowest.

The results confirmed the correlation between isolated fungal and fungal genera detected with metabarcoding analysis.

3.3. Pathogenicity Test

The artificial inoculation tests on a twig were able to reproduce the symptoms of browning of the wood by all tested fungi, which had been obtained from diseased wood of pomegranate plants affected by decay, and to highlight their greater or lesser aggressiveness. The positive control

N. parvum (ER 2123 tube) caused the expected symptoms in the three tests to confirm that the inoculation method works properly (

Tables S2–S4, Figure S1). The ANOVA results highlighted highly significant differences in terms of the length of browning between the treatments in all three tests (

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5).

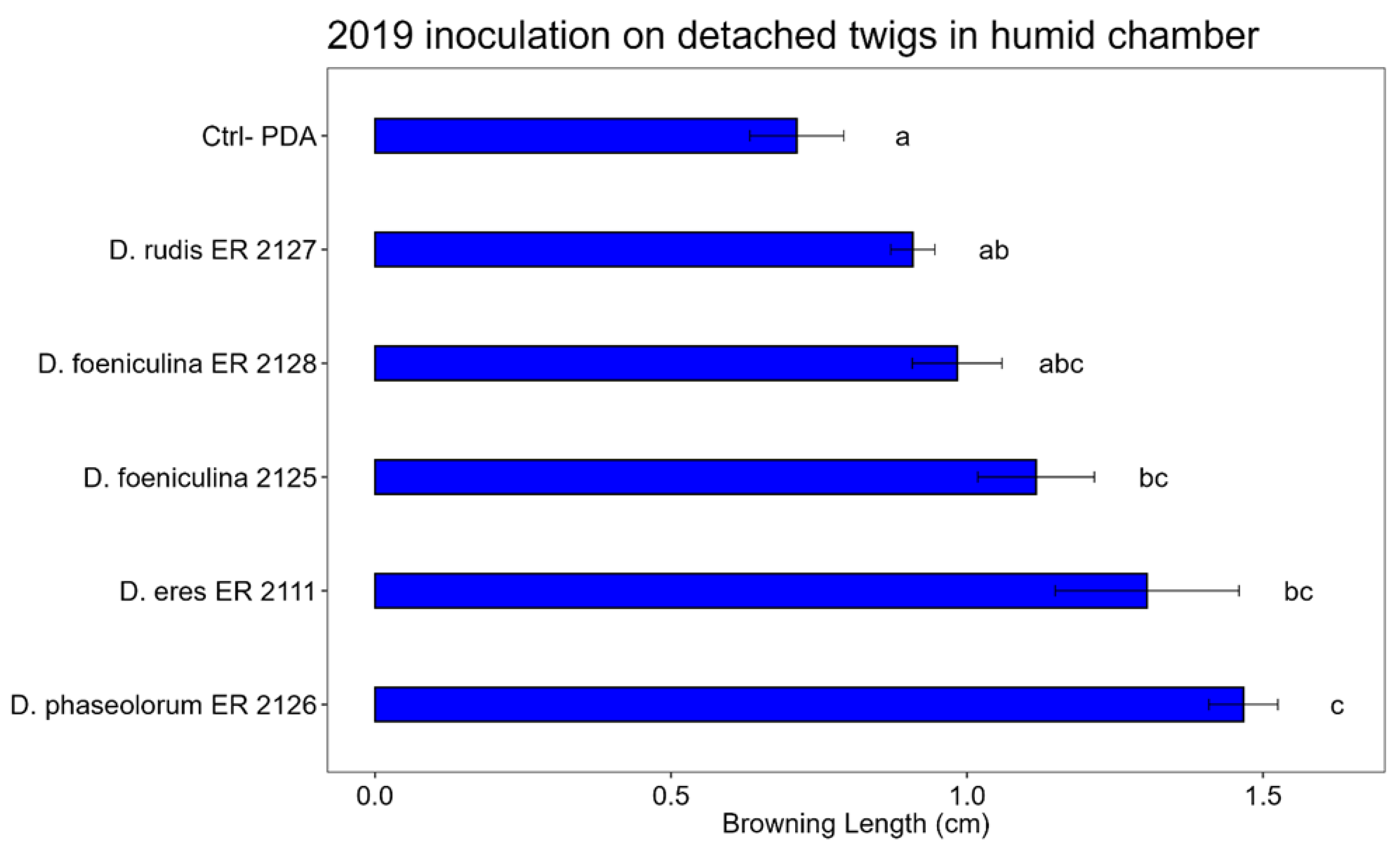

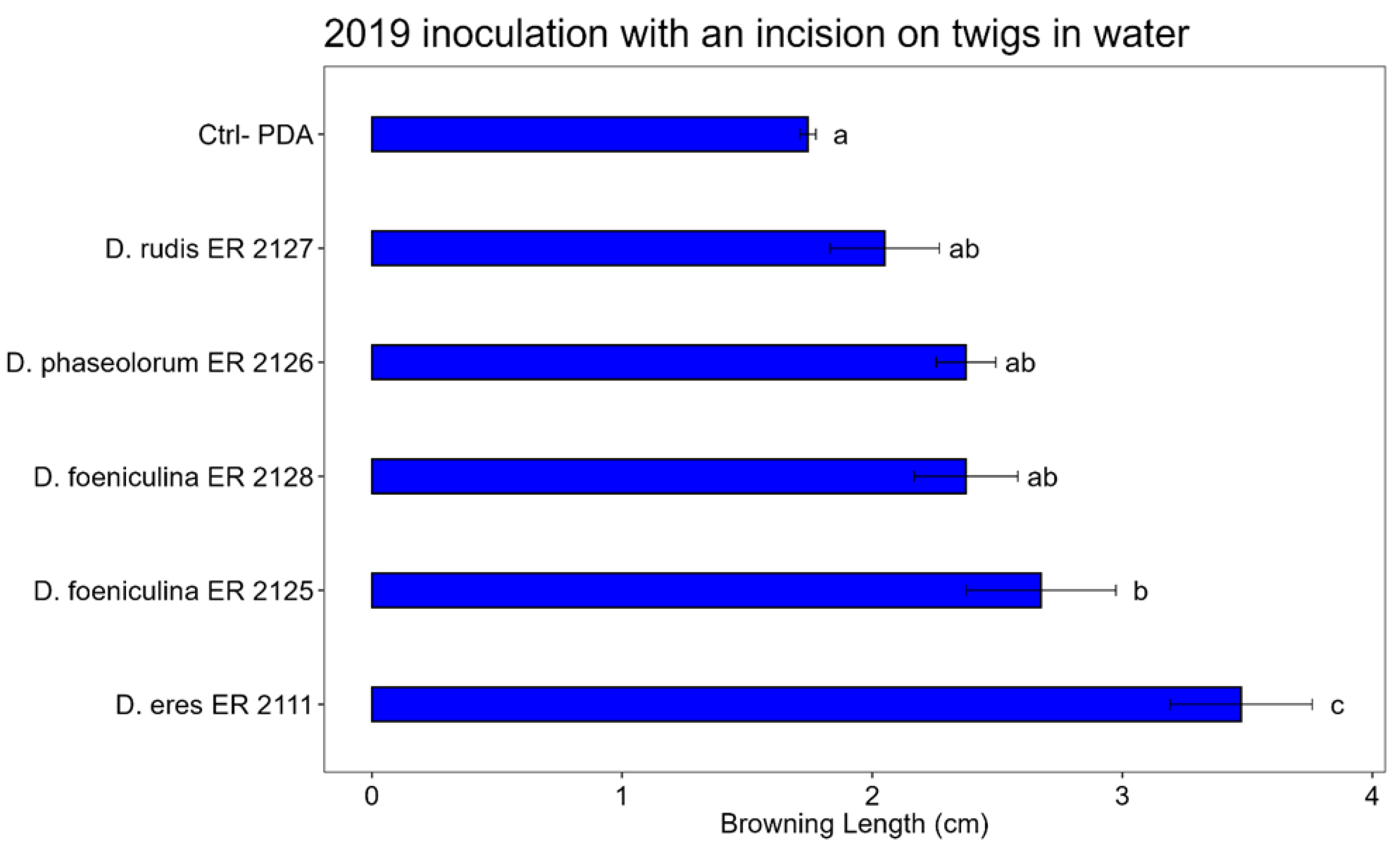

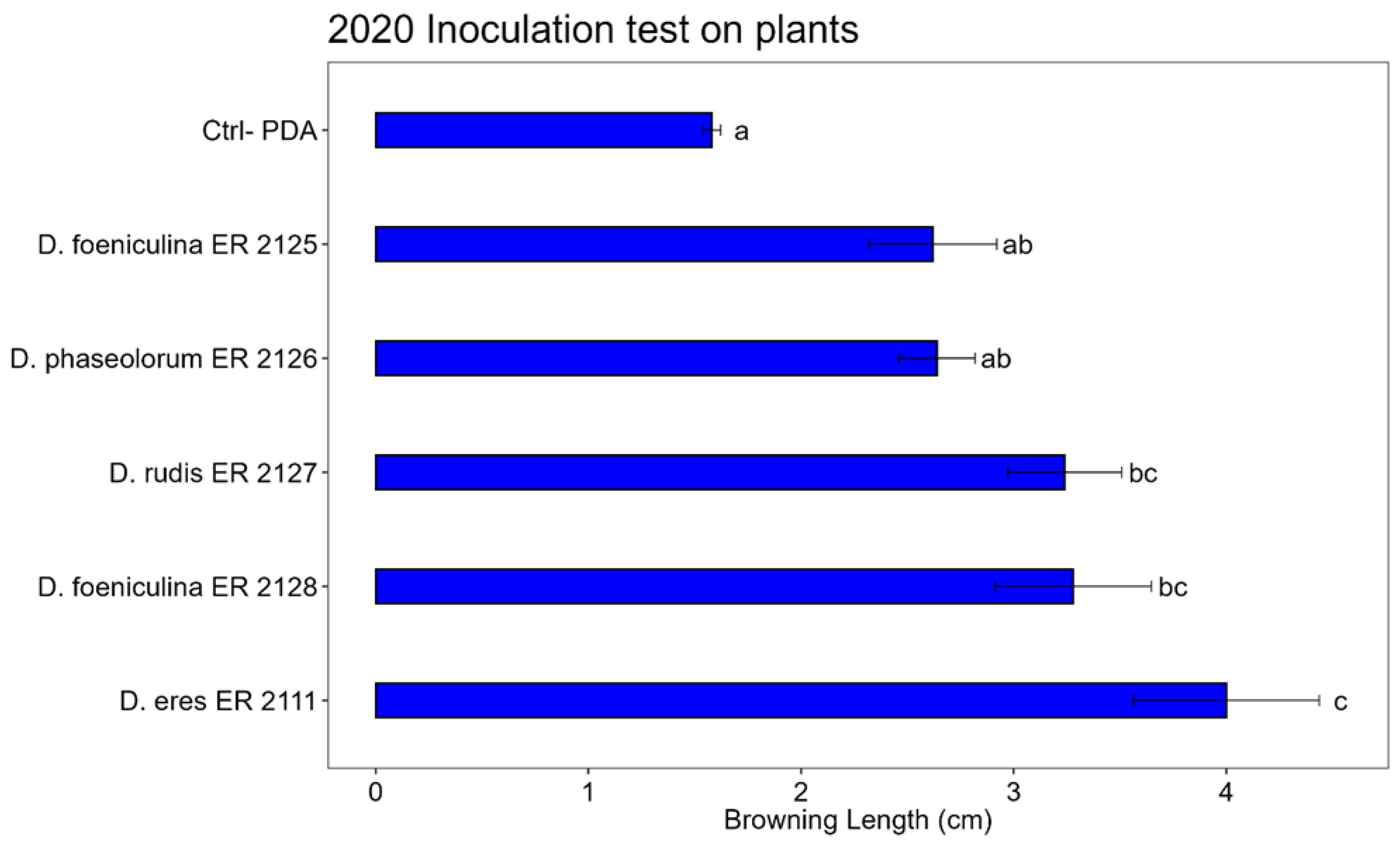

D. eres (ER 2111 tube) is the only isolate that shows constant pathogenicity in the three analyses (

Figure 9). The other isolates,

D. phaseolorum (ER 2126 tube),

D. foeniculina (ER 2128 and ER 2125 tubes) and

D. rudis (ER 2127 tube) were less aggressive and showed no statistically significant differences compared to the control. Despite this, their presence on symptomatic wood is not completely negligible and although with less aggression the mycelium manages to develop through the tissues of pomegranate wood.

The Tukey’s HSD test, performed on the data of the inoculations on detached twigs placed in humid chamber, shows that: D. phaseolorum (ER 2126 tube) and D. eres (ER 2111 Tube) shows statistically significant differences compared to the control. Among D. foeniculina (tubes ER 2128 and ER 2125) and D. rudis (ER 2127), there are no significant differences compared to the control, so they have not pathogenicity activity.

The Tukey’s HSD test, performed on the data of the inoculations on detached twigs in water, shows that: D. foeniculina (ER 2125 tube) and D. eres (ER 2111 Tube) showed statistically significant differences compared to the control. Among D. phaseolorum (ER 2126 tube) D. foeniculina (ER 2128 tube) and D. rudis (ER 2127 tube), there are no significant differences compared to the control, so they have not pathogenicity activity.

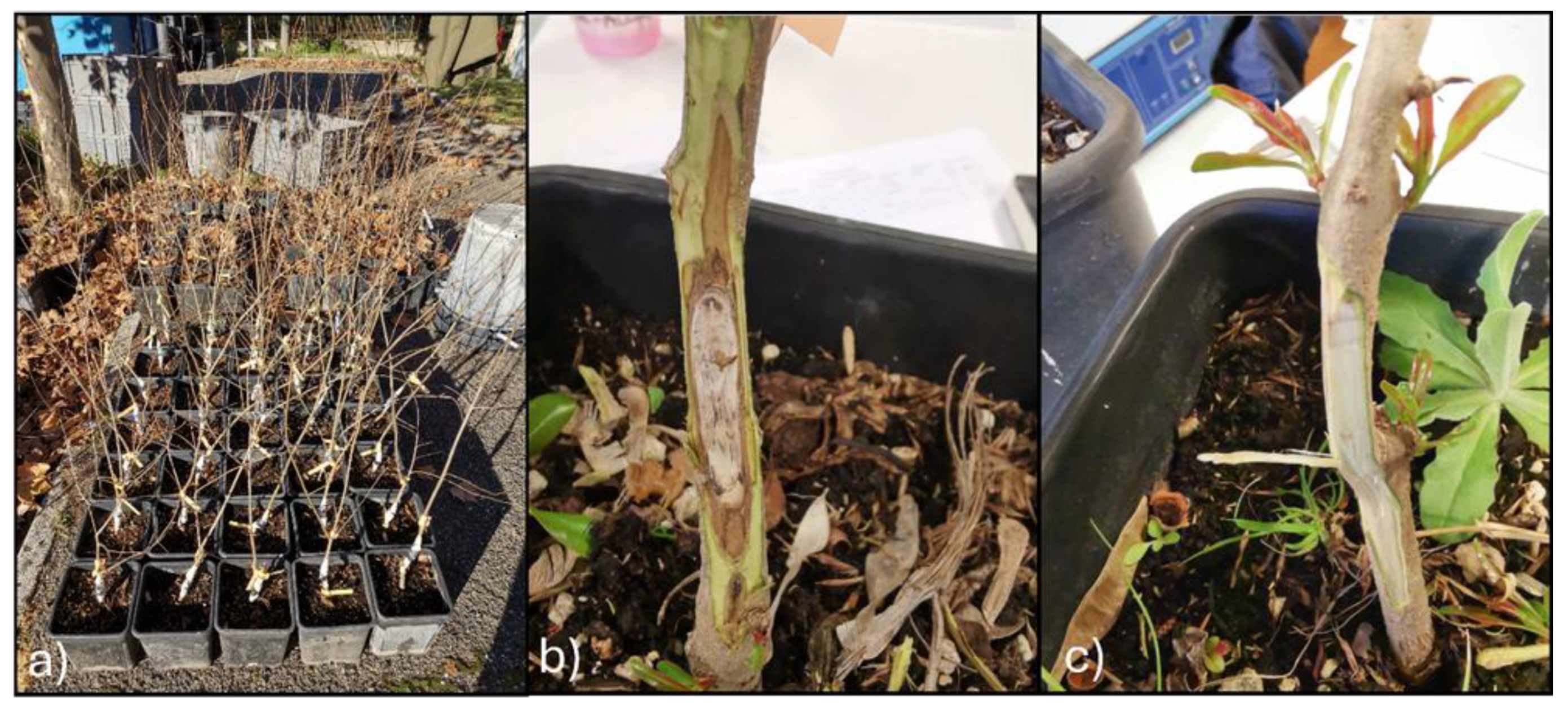

The Tukey’s HSD test, performed on the data of the inoculations on pomegranate plants, showed that

D. eres (ER 2111 Tube),

D. foeniculina (ER 2125 tube), and

D. rudis (ER 2127 tube) showed statistically significant differences compared to the control (

Figure 13). Among

D. phaseolorum (ER 2126 tube) and

D. foeniculina (ER 2128 tube), there were no significant differences compared to the control, so they had no pathogenicity activity.

4. Discussion

The rapid expansion of pomegranate cultivation in central and southern Italy, primarily using foreign varieties, has revealed unexpected phytosanitary issues. This is notable for a plant traditionally considered hardy and relatively free from phytosanitary concerns, apart from well-documented issues affecting the fruit. Over the past three years, the first cases of plant decline and mortality have been reported, with losses reaching 30–40% in 2015 and escalating to 90% in subsequent years. In Puglia, in 2016, Pollastro

, et al. [

6] identified

C.

granati, a pathogen already known in various pomegranate-growing regions worldwide, as the causative agent of fruit rot. However, in China, Iran, and Spain,

C.

granati has also been associated with cankers and pomegranate tree mortality, while in Greece and Turkey, it has been reported as a cause of stem cankers [

39]. In central Italy, particularly in Lazio, this issue was initially unknown at the start of our investigation. However, following reports and subsequent inspections and analyses described in this study, two potential fungal pathogens were identified:

N.

parvum and

Diaporthe spp., which are likely to act synergistically. Initially,

N.

parvum was considered the only causal agent [

14] and was, therefore, the primary focus of further investigations.

The metabarcoding analysis had limitations due to the availability of ITS2 sequences in the UNITE database, which, at present, does not allow for taxonomic resolution sufficient to classify all DNA in the sample at the species level. As a result, a proportion of fungal DNA could only be identified at the division or, at best, genus level. Additionally, a significant proportion of DNA (on average 29.3%) remained unassigned, potentially concealing other pathogenic fungi. The metabarcoding analysis, even within its limits, allowed us to highlight in the two plants analysed that N. parvum and C. granati were not present in the diseased wood where it was not isolated, nor even in the healthy wood, excluding the possibility that it was present as an endophyte.

This result was significant as it validated the test performed, confirming the presence of a substantially richer fungal community in symptomatic tissue, which exhibited clear signs such as cankers and wood browning. In contrast, the fungal DNA detected in asymptomatic samples was likely associated with the endophytic fungal flora naturally present in pomegranate wood.

Different diseases are already known as the Esca of Grapevine [

40] and Esca-like symptoms of

Actinidia [

41] caused by fungi complex. Today, there are other diseases, such as “Kiwifruit Vine Decline Syndrome” (KVDS), caused by different microorganisms and abiotic disorders. The causes of the decline are still discussed; currently are involved and reported pathogenic species such as

Phytopythium vexans [

42,

43],

Phytophthora spp [

44],

Cylindrocarpon [

45] and, anaerobic bacteria

Clostridium [

46].

Similarly to other complex syndromes, abiotic stress could represent a trigger factor for the disease. The pomegranate, mainly the ’Wonderful’ cultivar, is widely cultivated in warm climates and originates from regions such as Iran and surrounding regions, from where it spreads to other parts of the world [

47], where temperature conditions are more similar to those of southern Italy rather than central regions like Lazio. This difference is attributed to the latitudinal gradient, as well as variations in altitude and proximity to the sea, which influence mean winter temperatures [

31] For this reason, climatic conditions play a central role as a trigger for wood decay.

Few studies have dealt with the taxonomic resolution obtained using both the ITS1 and the ITS2 barcodes on the same dataset [

27,

48,

49,

50,

51]. They have been carried out on both

Ascomycota [

52,

53] and

Basidiomycota [

54]. The choice of primers can introduce taxonomic bias, as they may produce a higher number of mismatches in certain taxa [

53,

55,

56]. Some studies also reported that the two spacers are prone to preferential amplification at different levels [

48,

49,

50,

52,

53]. Basidiomycetes have on average longer amplicon sequences for the ITS2, and since the shorter sequences are preferentially sequenced with high-throughput sequencing (HTS), the use of ITS2 would favour the detection of ascomycetes [

53]. On the other hand, ITS1 often contains an intron that extends its sequence at the 5′-end [

57], thereby promoting an over-representation of those sequences that lack the intron [

49]. Because ITS2 is more frequently represented in public databases, has a higher number of available sequences, and offers a better taxonomic resolution, it has been proposed as the better choice for parallel sequencing [

52]. In some cases, however, no substantial differences between ITS1 and ITS2 were recovered [

27,

54]. Finally, there are numerous studies that consider a single spacer, either the ITS1 or ITS2 [

35,

53,

58,

59].

As fungal metabarcoding studies have used different HTS platforms [

60], different bioinformatic pipelines have been proposed [

61,

62]. These have been developed based on experience gained from data analyses of prokaryote datasets [

63]. However, no standard procedure has been established so far for fungal sequence data. The analyses seem strongly dependent on the working hypotheses of each study and on the type of sequence at hand. As the majority of studies target fungal communities to uncover unknown diversity, an important and ongoing problem is the definition of those sequences lacking an assigned taxonomy [

52]. For this reason, many sequences remain identified as “unassigned”. In addition, many fungi have not yet been sequenced and cannot offer reference sequences for ongoing studies [

63].

The molecular markers used in this investigation have a broad level of fungal species identification, so the failure to detect Coniella granati among the identified species allows us to speculate that other species are implicated in pomegranate wood decay syndrome. In fact, the metabarcoding results suggested a relatively stable microbial community, with a substantial proportion of OTUs present in multiple samples. C. granati, in the two plants object of our study, it can be said with certainty that it was not present and, therefore, was not involved with the cankers and deaths found in Pavona and Sermoneta. This is confirmed both by the isolations carried out on diseased plants and by the metagenomic analysis where the presence of Schizoparmaceae was not found.

The presence of a well-defined core microbiome (31.7% of OTUs in all samples) indicates a consistent microbial signature across different conditions. The data also suggest good sequencing depth, with minimal bias from zero or low-count OTUs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; methodology, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; formal analysis, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; investigation, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; resources, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; data curation, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; visualization, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.; supervision, V.B., M.T.V. and R.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Sub-cortical browning on the sampled Plant 2 in Pavona (RM).

Figure 1.

Sub-cortical browning on the sampled Plant 2 in Pavona (RM).

Figure 2.

Sampling points of Plant1 (left) and Plant2 (right), showing the cankers and browning wood, with the identification legend of each sampled section, later described in

Table 1. The circled sections were used for the metabarcoding analysis.

Figure 2.

Sampling points of Plant1 (left) and Plant2 (right), showing the cankers and browning wood, with the identification legend of each sampled section, later described in

Table 1. The circled sections were used for the metabarcoding analysis.

Figure 3.

Pomegranate twigs inoculated and placed in the humid chamber.

Figure 3.

Pomegranate twigs inoculated and placed in the humid chamber.

Figure 4.

Pomegranate twigs (4 years old) inoculated and placed in water.

Figure 4.

Pomegranate twigs (4 years old) inoculated and placed in water.

Figure 5.

Pomegranate branches without the first layers of the bark to discover the browned area and measure its length in the longitudinal direction (highlighted in red).

Figure 5.

Pomegranate branches without the first layers of the bark to discover the browned area and measure its length in the longitudinal direction (highlighted in red).

Figure 6.

Fungal relative abundance at genus level in the different sections of the 8 experimental units. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

Figure 6.

Fungal relative abundance at genus level in the different sections of the 8 experimental units. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

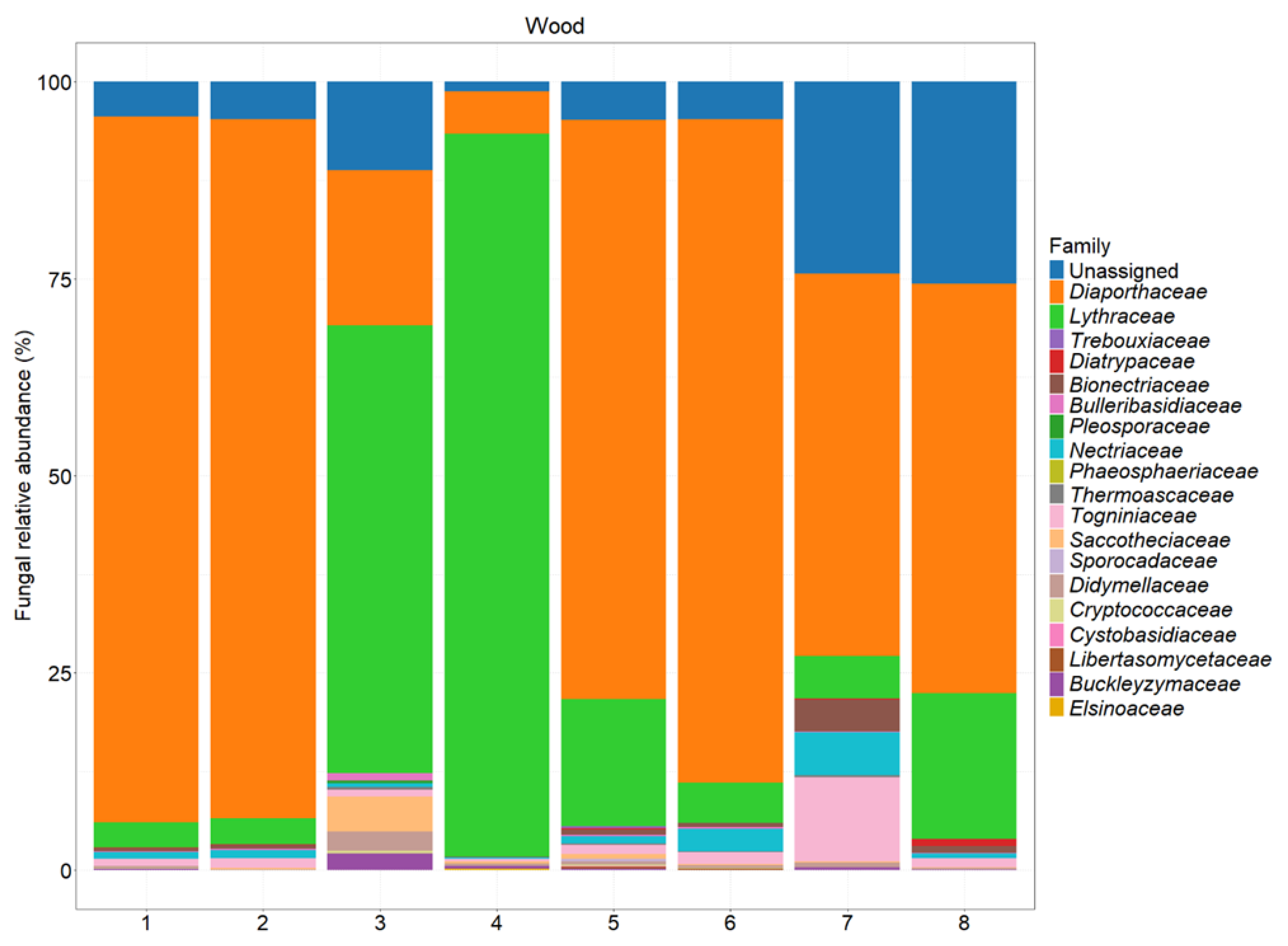

Figure 7.

Fungal abundance at the family level in different sections of the tested plants. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

Figure 7.

Fungal abundance at the family level in different sections of the tested plants. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

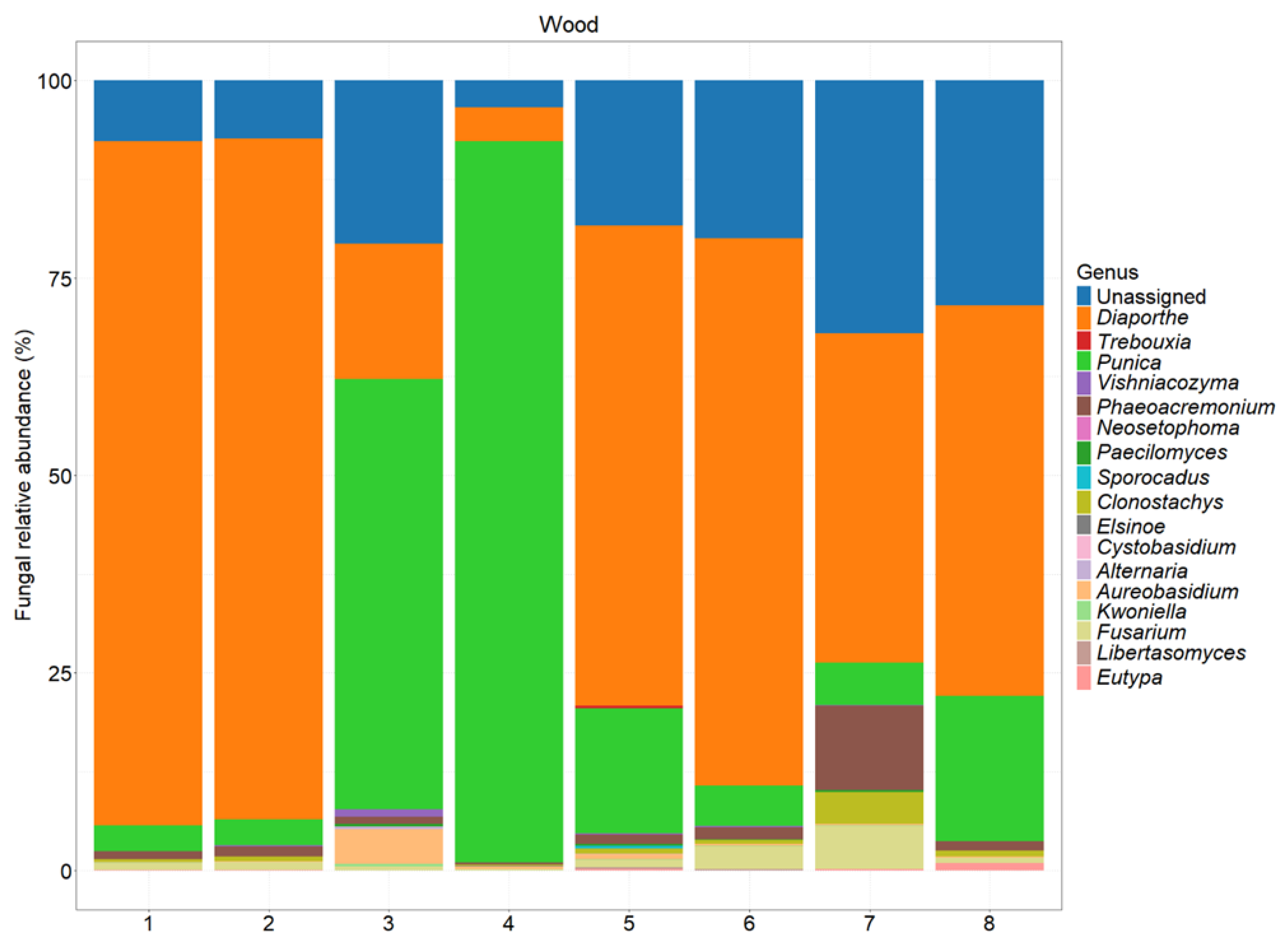

Figure 8.

Fungal abundance at the family level in different sections of the tested plants. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

Figure 8.

Fungal abundance at the family level in different sections of the tested plants. A description of each sample is provided in

Table 1.

Figure 9.

On the left (4 branches), is the result of the inoculation of D. foeniculina (ER 2128 tube); on the right (4 branches), is the result of the inoculation of D. eres (ER 2111 tube), using procedure 1.

Figure 9.

On the left (4 branches), is the result of the inoculation of D. foeniculina (ER 2128 tube); on the right (4 branches), is the result of the inoculation of D. eres (ER 2111 tube), using procedure 1.

Figure 10.

Bar plot showing the average lengths (cm) of browning caused by inoculations on the detached twigs placed in a humid chamber are reported. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 10.

Bar plot showing the average lengths (cm) of browning caused by inoculations on the detached twigs placed in a humid chamber are reported. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 11.

Bar plot showing the average lengths (cm) of browning caused by inoculations on the detached twigs in water a is reported. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 11.

Bar plot showing the average lengths (cm) of browning caused by inoculations on the detached twigs in water a is reported. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 12.

Bar plot showing the average browning length (cm) caused by inoculations on pomegranate plants in 2020. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 12.

Bar plot showing the average browning length (cm) caused by inoculations on pomegranate plants in 2020. The letters above the bars indicate significant statistical differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences based on One-Way ANOVA results at p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (4 replicates).

Figure 13.

(a) Pomegranate plants immediately after inoculation. (b) Pomegranate trunk with the outer bark layers removed, revealing a browned area at the end of the trial with D. eres. (c) Negative control: pomegranate trunk with the outer bark layers removed, inoculated with sterile PDA, showing healthy tissue.

Figure 13.

(a) Pomegranate plants immediately after inoculation. (b) Pomegranate trunk with the outer bark layers removed, revealing a browned area at the end of the trial with D. eres. (c) Negative control: pomegranate trunk with the outer bark layers removed, inoculated with sterile PDA, showing healthy tissue.

Table 1.

Description of the experimental units reported in

Figure 2.

Table 1.

Description of the experimental units reported in

Figure 2.

| Experimental Units |

Section |

Phenotypic Features |

| 1 |

1R8A+1R8B |

Brown tissues above the canker from the apical portion (Plant 1) |

| 2 |

1R7A |

Brown tissue from the lateral branch close to the canker (Plant 1) |

| 3 |

1R2A+1R8C |

Asymptomatic tissues from branches (Plant 1) |

| 4 |

1R5A |

Asymptomatic tissue (showing bark roughness) from the lateral branch (Plant 1) |

| 5 |

1T1A |

Brown tissue from the basal area of the trunk, corresponding to the collar (Plant 1) |

| 6 |

1T1B |

Brown tissue below the canker from the trunk (Plant 1) |

| 7 |

1T1C+1T1D |

Brown tissues into the canker area (Plant 1) |

| 8 |

2T1A+2T1C |

Brown tissues from the trunk (Plant 2) |

Table 2.

List of fungal species isolated from symptomatic pomegranate wood in the two sampling sites, with sampling time, representative strains and GenBank numbers. *Samples used for metabarcoding analysis, from all the 8 Experimental Units.

Table 2.

List of fungal species isolated from symptomatic pomegranate wood in the two sampling sites, with sampling time, representative strains and GenBank numbers. *Samples used for metabarcoding analysis, from all the 8 Experimental Units.

| Strain CREA-DC Collection Code |

Species |

Isolation incidence (% of the total fungal colonies) |

Pavona |

Sermoneta |

GenBank Accession Number |

| July 2017 |

October 2017 |

March 2018* |

September 2018 |

February 2019 |

| ER2123 |

N. parvum |

27.6 |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

MW020287 |

| ER2111 |

D. eres |

20.7 |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

MW020285 |

| ER2125, ER2128 |

D. foeniculina |

17.2 |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

MW020288, MW032268

|

| ER2126 |

D. phaseolorum |

3.4 |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

MW020289 |

| ER2127 |

D. rudis |

3.4 |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

MW032267 |

| ER2145 |

Cytospora acaciae |

3.4 |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

/ |

| / |

Eutypa lata |

0.5 |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

/ |

| ER2130 |

Gliocladium spp. |

24.1 |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

/ |

| / |

Phoma glomerata |

5.3 |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

/ |

| / |

Neopestalotiopsis clavispora |

1 |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

/ |

| / |

Fusarium spp. |

18.6 |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

/ |

Table 3.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate detached twigs in the humid chamber in 2019.

Table 3.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate detached twigs in the humid chamber in 2019.

| EFFECT |

SS |

DF |

MS |

F |

ProbF |

| Isolate |

1.49215 |

5 |

0.29843 |

13.64701997 |

3.93174E-05 |

| Residual |

0.328016667 |

15 |

0.021867778 |

|

|

| Total |

1.94685 |

23 |

0.084645652 |

|

|

Table 4.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate detached twigs in water in 2019.

Table 4.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate detached twigs in water in 2019.

| EFFECT |

SS |

DF |

MS |

F |

ProbF |

| Isolate |

8.419153439 |

5 |

1.683831 |

14.04785 |

4.26E-06 |

| Residual |

2.517142857 |

21 |

0.119864 |

|

|

| Total |

10.9362963 |

26 |

0.420627 |

|

|

Table 5.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate plants in 2020.

Table 5.

ANOVA results conducted on length (cm) of browning caused by the inoculated fungi on the pomegranate plants in 2020.

| EFFECT |

SS |

DF |

MS |

F |

ProbF |

| Isolate |

16.79066667 |

5 |

3.358133 |

9.631358 |

3.84E-05 |

| Residual |

8.368 |

24 |

0.348667 |

|

|

| Total |

25.15866667 |

29 |

0.86754 |

|

|

| C.V. (%): 20,4082959922632 |

|

|

|

|