Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The genus Tilia (Malvaceae) comprises long-lived broadleaf trees of considerable ecological, cultural, and historical importance in temperate Europe and Asia. Among these, Tilia × europaea L. is a key native species in Central and Northern Europe, with individuals documented to live for several centuries. While the external and soil-associated microbiomes of linden have been studied, the internal fungal communities inhabiting ancient trees remain poorly understood. Wood-inhabiting fungi (the wood mycobiome) include endophytes, saprotrophs, and potential pathogens that can strongly influence host vitality and ecosystem processes. Advances in high-throughput amplicon sequencing (HTAS) now provide unprecedented opportunities to characterize these hidden communities. In this study, we investigated the trunk wood mycobiome of an ancient Tilia × europaea L. individual using a culture-independent HTAS approach. The results reveal a diverse fungal assemblage, including taxa like Arthinium or Phialemonium not previously reported from living linden wood, and highlight potential implications for tree health and longevity. This work provides a first baseline characterization of the internal mycobiome of ancient Tilia trees and contributes to broader efforts to conserve their biological and cultural value.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

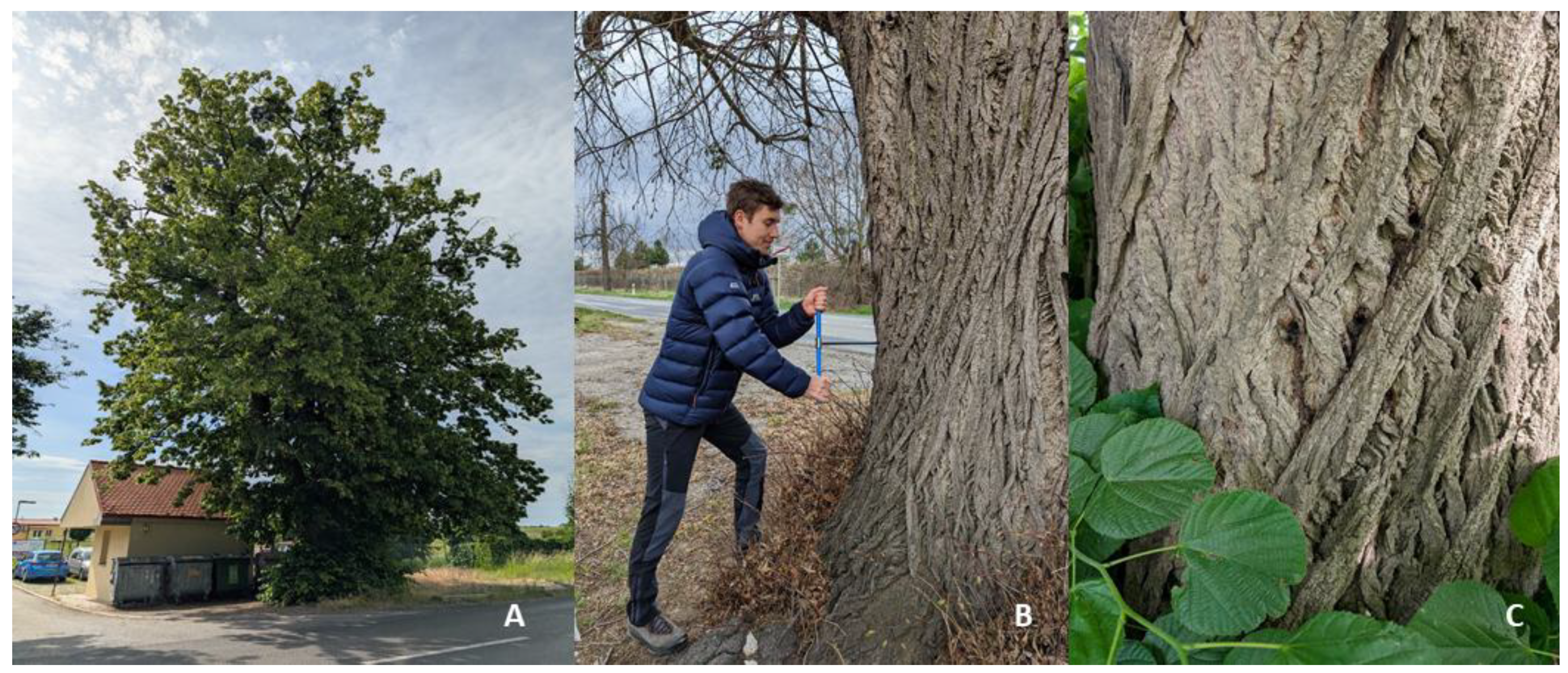

2.1. Linden Tree

2.2. Sampling

2.3. High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatics and Data Evaluation

2.5. Fungal Diversity and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

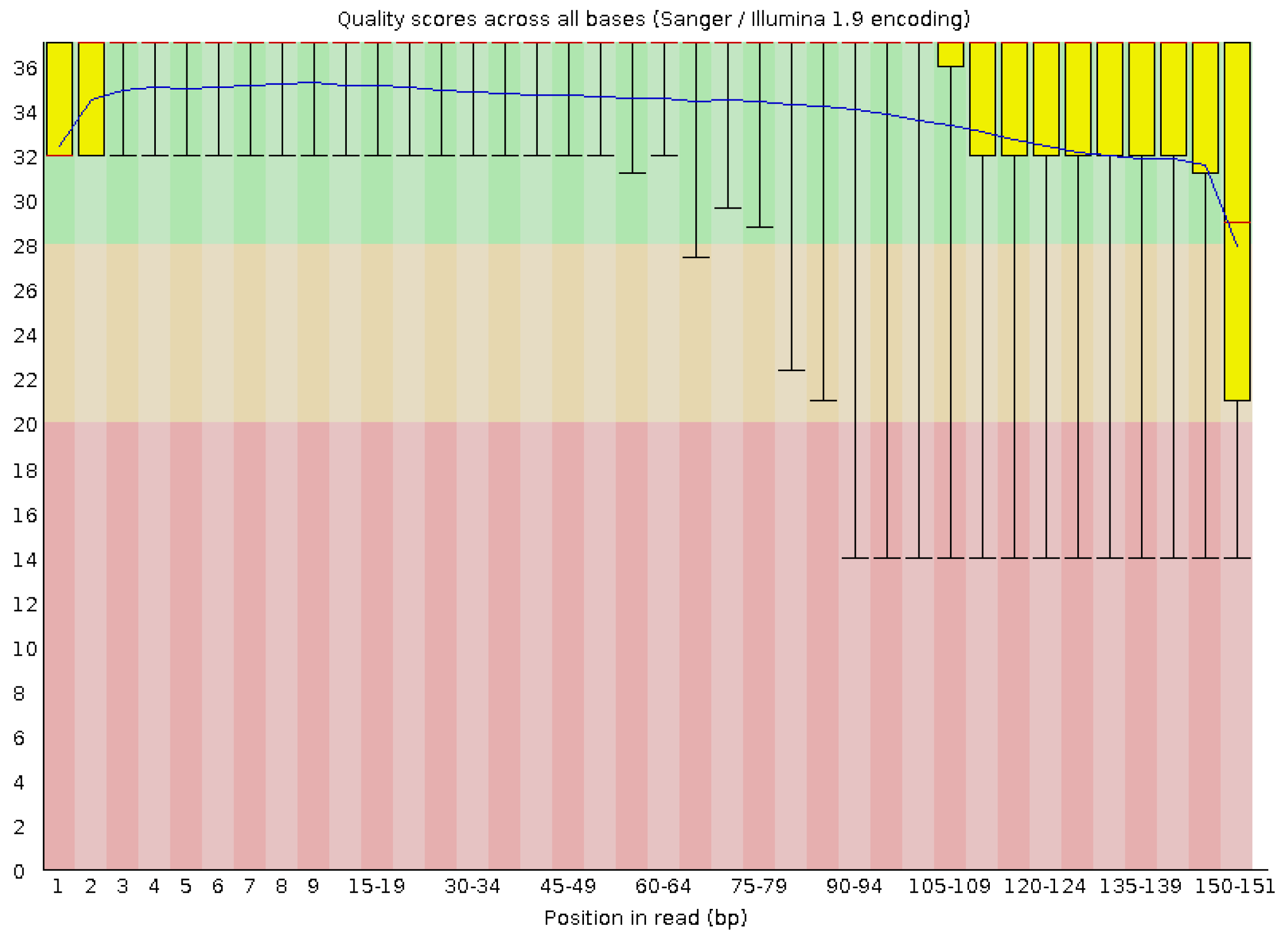

3.1. High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing

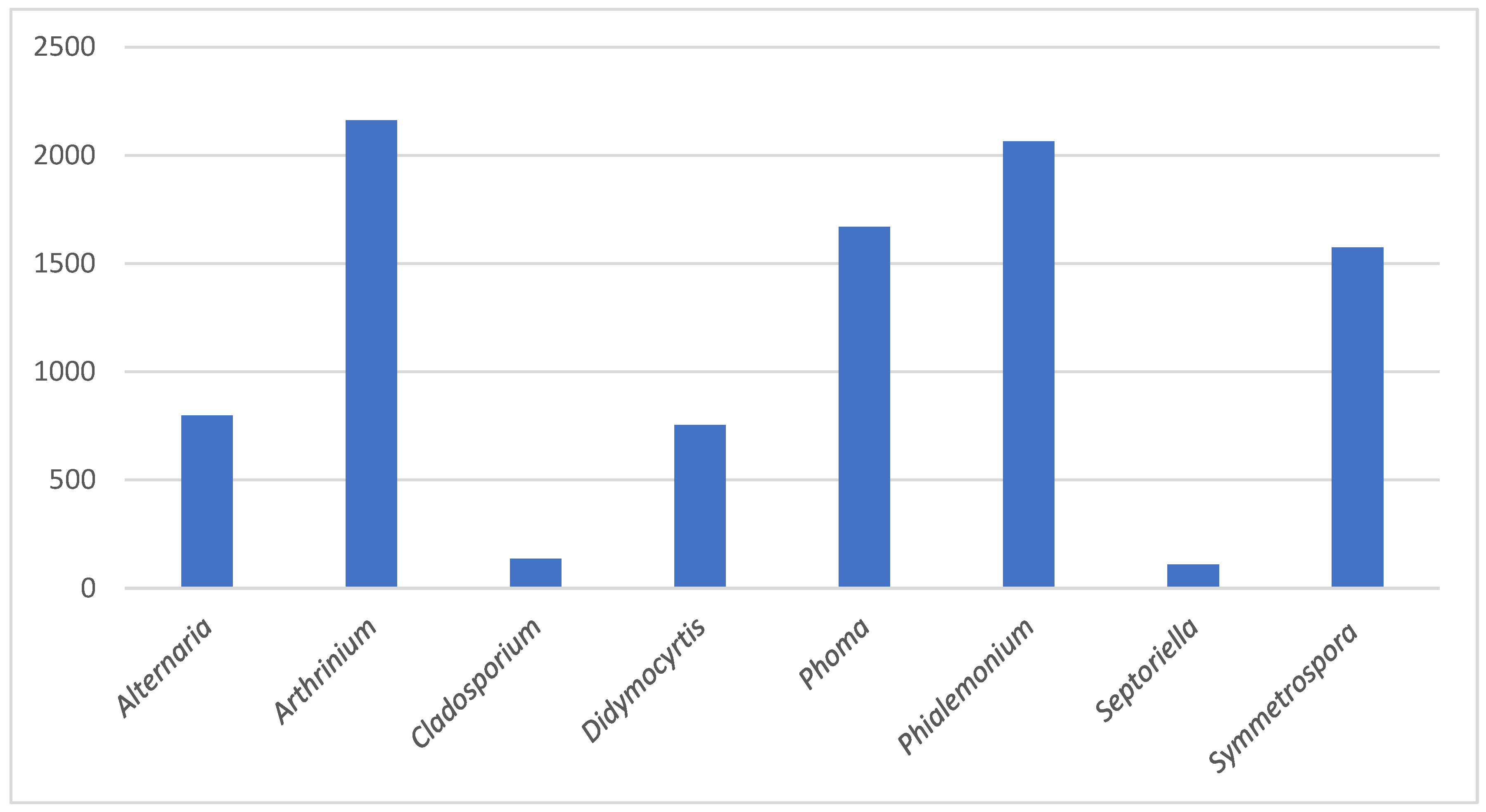

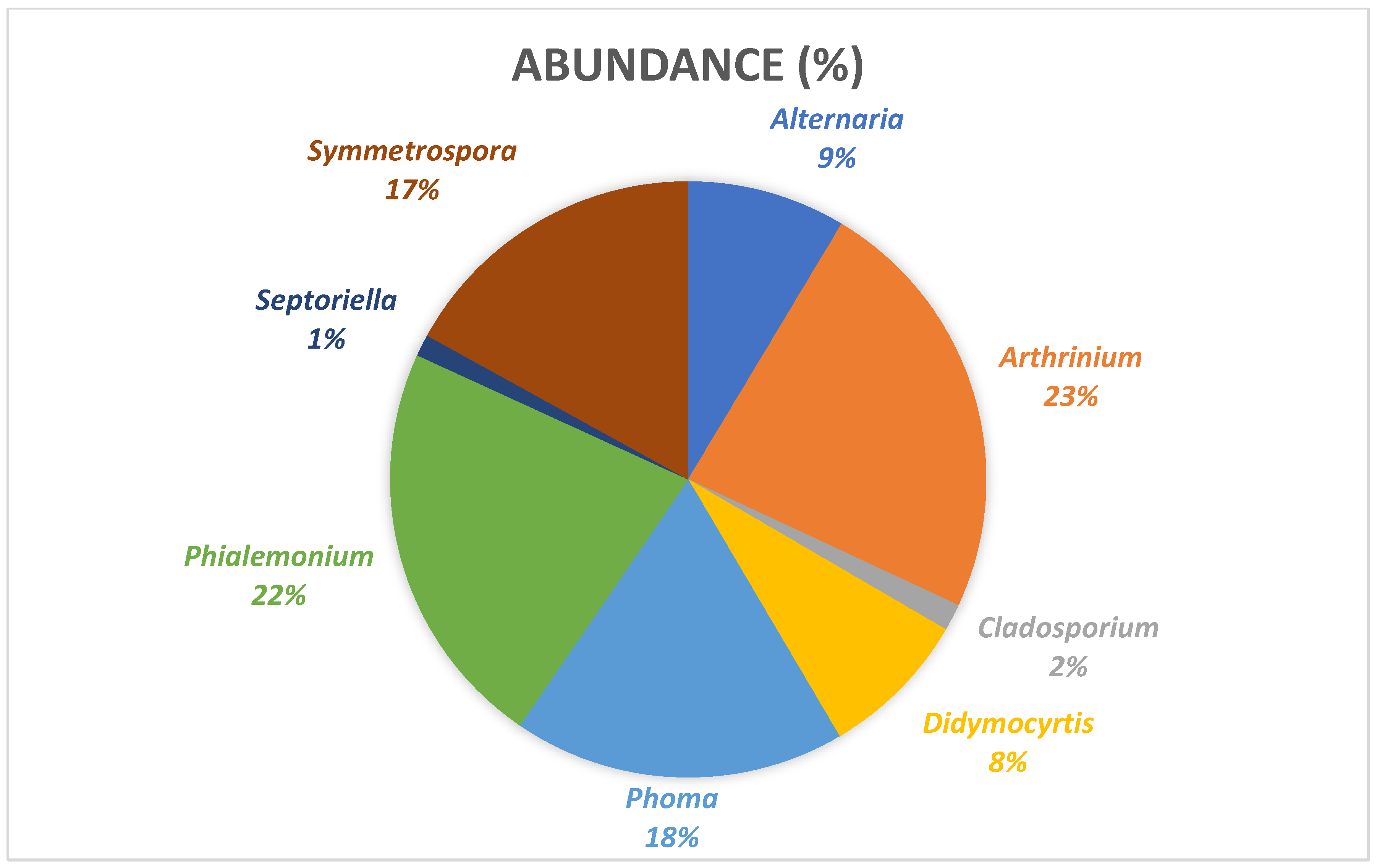

3.2. Taxonomy

3.3. Morphological Evaluation of the Linden Tree

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lukaszkiewicz, J.; Kosmala, M.; Chrapka, M.; Borowski, J. Determining the Age of StreetsideTilia cordataTrees with a DBH-Based Model. Arboric. Urban For. 2005, 31, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilous, S.Y.; Prysiazhniuk, L.M. DNA analysis of centuries-old linden trees using SSR-markers. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2020, 11, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Pietsch, K.A.; Lentendu, G.; Schöps, R.; Bruelheide, H.; Wirth, C.; Buscot, F.; Wubet, T. Characterization of Unexplored Deadwood Mycobiome in Highly Diverse Subtropical Forests Using Culture-independent Molecular Technique. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Mapook, A.; Wu, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-T. Characterization of the Castanopsis carlesii Deadwood Mycobiome by Pacbio Sequencing of the Full-Length Fungal Nuclear Ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS). Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on day month year).

- Tamiru, M.; Hardcastle, T.J.; Lewsey, M.G. Regulation of genome-wide DNA methylation by mobile small RNAs. New Phytol. 2017, 217, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, E.G.; Ellis, M.B. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes. IV. Mycologia 1964, 56, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, K. , Morgan-Jones, G., Gams, W., & Kendrick, B. 2011. The genera of Hyphomycetes (CBS Biodiversity Series 9). Utrecht, The Netherlands: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre.

- McNeill, J. , Barrie, F. R., Buck, W. R., Demoulin, V., Greuter, W., Hawksworth, D. L., Herendeen, P. S., Knapp, S., Marhold, K., Prado, J., … Turland, N. J. 2012. International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, 11 (Regnum Vegetabile 154). Königstein: Koeltz Scientific Books. 20 July.

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z. A phylogenetic re-evaluation of Arthrinium. IMA Fungus 2013, 4, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Jiang, N.; Liang, L.-Y.; Yang, Q.; Tian, C.-M. Arthrinium trachycarpum sp. nov. from Trachycarpus fortunei in China. Phytotaxa 2019, 400, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Dong, Z.; Yun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, J.; Zhang, X. Phylogeny, Taxonomy and Morphological Characteristics of Apiospora (Amphisphaeriales, Apiosporaceae). Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerin, D.; Nigro, F.; Faretra, F.; Pollastro, S. Identification of Arthrinium marii as Causal Agent of Olive Tree Dieback in Apulia (Southern Italy). Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gams, W.; McGinnis, M.R. Phialemonium, A New Anamorph Genus Intermediate Between Phialophora and Acremonium. Mycologia 1983, 75, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manici, L.M.; De Meo, I.; Saccà, M.L.; Ceotto, E.; Caputo, F.; Paletto, A. The relationship between tree species and wood colonising fungi and fungal interactions influences wood degradation. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, Y.; Chakravarty, P. Role of Phialemonium curvatum as a potential biological control agent against a blue stain fungus on aspen. Eur. J. For. Pathol. 1999, 29, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Strobel, G.; Stierle, A.; Hess, W.; Lee, J.; Clardy, J. A fungal endophyte-tree relationship: Phoma sp. in Taxus wallachiana. Plant Sci. 1994, 102, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migheli, Q.; Cacciola, S.O.; Balmas, V.; Pane, A.; Ezra, D.; Lio, G.M.d.S. Mal Secco Disease Caused byPhoma tracheiphila: A Potential Threat to Lemon Production Worldwide. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, F. , Ippolito, A., & Salerno, M. G. 2011. Mal secco disease of citrus: A journey through a century of research. Journal of Plant Pathology, 93(3), 523–560. https://www.jstor. 4199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.-M.; Yurkov, A.M.; Göker, M.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Leavitt, S.D.; Groenewald, M.; Theelen, B.; Liu, X.-Z.; Boekhout, T.; Bai, F.-Y. Phylogenetic classification of yeasts and related taxa within Pucciniomycotina. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 81, 149–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haelewaters, D.; Toome-Heller, M.; Albu, S.; Aime, M. Red yeasts from leaf surfaces and other habitats: three new species and a new combination of Symmetrospora (Pucciniomycotina, Cystobasidiomycetes). Fungal Syst. Evol. 2020, 5, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Han, S.; Ren, X.; Sichone, J.; Fan, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Cai, W.; Sun, F. Succession of Fungal Community during Outdoor Deterioration of Round Bamboo. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Deyett, E.; Stajich, J.E.; El-Kereamy, A.; Roper, M.C.; Rolshausen, P.E. Microbiome diversity, composition and assembly in a California citrus orchard. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherabadi, S.; Zafari, D. Isolation and characterization of Alternaria malorum as a causal agent of bark canker on walnut trees. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2022, 62, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauiyakh, O.; EL Fahime, E.; Ninich, O.; Aarabi, S.; Bentata, F.; Chaouch, A.; Ettahir, A. SHORT NOTES: FIRST REPORT OF THE PHYTOPATHOGENIC FUNGUS ALTERNARIA TENUISSIMA IN CEDARWOOD (CEDRUS ATLANTICA M.) IN MOROCCO. Wood Res. 2023, 68, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakunyingcharoen, T.; Lombard, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Toanun, C.; Alfenas, A.C.; Crous, P.W. Mycoparasitic species of Sphaerellopsis, and allied lichenicolous and other genera. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, D.; Diederich, P.; Lawrey, J.D.; Berger, F.; Freebury, C.E.; Coppins, B.; Gardiennet, A.; Hafellner, J. Phylogenetic insights resolve Dacampiaceae (Pleosporales) as polyphyletic: Didymocyrtis (Pleosporales, Phaeosphaeriaceae) with Phoma-like anamorphs resurrected and segregated from Polycoccum (Trypetheliales, Polycoccaceae fam. nov.). Fungal Divers. 2015, 74, 53–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; I Burgess, T.; Hardy, G.E.S.J.; A Barber, P.; Alvarado, P.; Barnes, C.W.; Buchanan, P.K.; Heykoop, M.; Moreno, G.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 558–624. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2017, 38, 240–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.; Wingfield, M.; Burgess, T.; Hardy, G.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Baseia, I.; García, D.; Gusmão, L.; Souza-Motta, C.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 716–784. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2018, 40, 239–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, K.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jung, H.-Y. Morphology and Phylogeny of Two Novel Species within the Class Dothideomycetes Collected from Soil in Korea. Mycobiology 2020, 49, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensch, K.; Braun, U.; Groenewald, J.; Crous, P. The genus Cladosporium. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 72, 1–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diversity indices | Value |

| Taxa_S | 8 |

| Individuals | 9262 |

| Dominance_D | 0.1798 |

| Simpson_1-D | 0.8202 |

| Shannon_H | 1.813 |

| Evenness_e^H/S | 0.7662 |

| Brillouin | 1.81 |

| Menhinick | 0.08313 |

| Margalef | 0.7664 |

| Equitability_J | 0.8719 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.8618 |

| Berger-Parker | 0.2333 |

| Chao-1 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).