Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

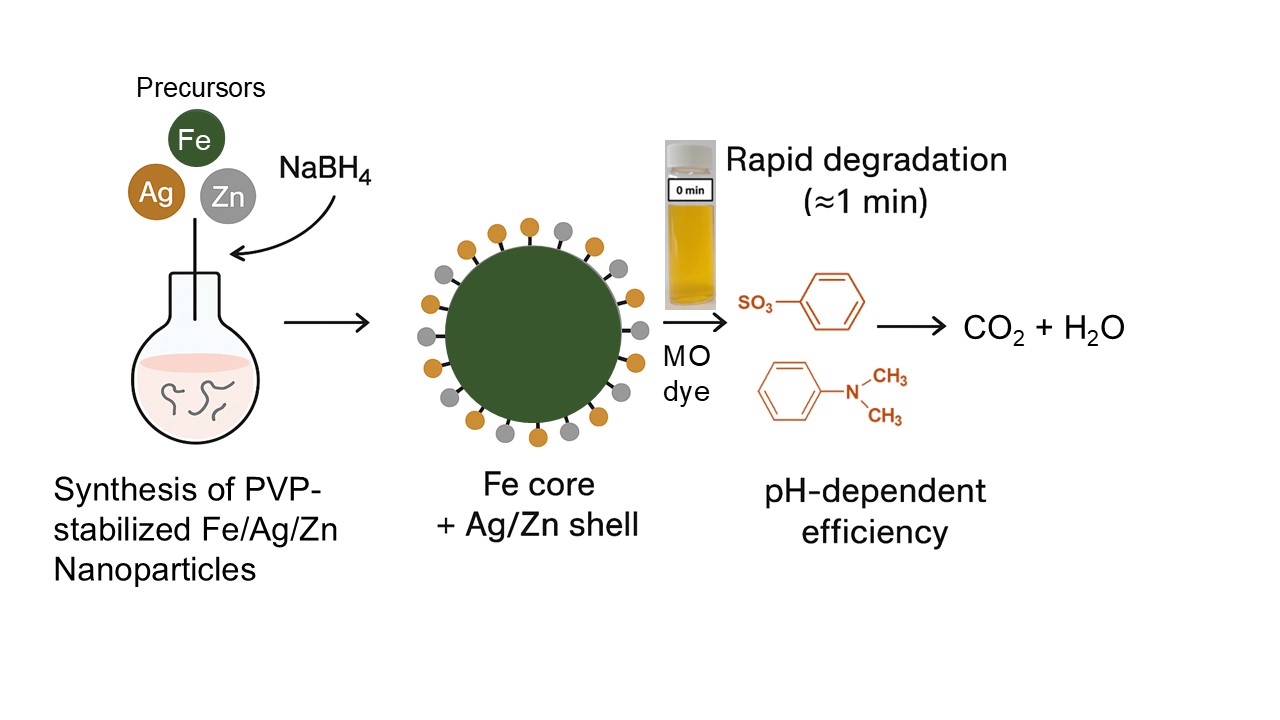

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

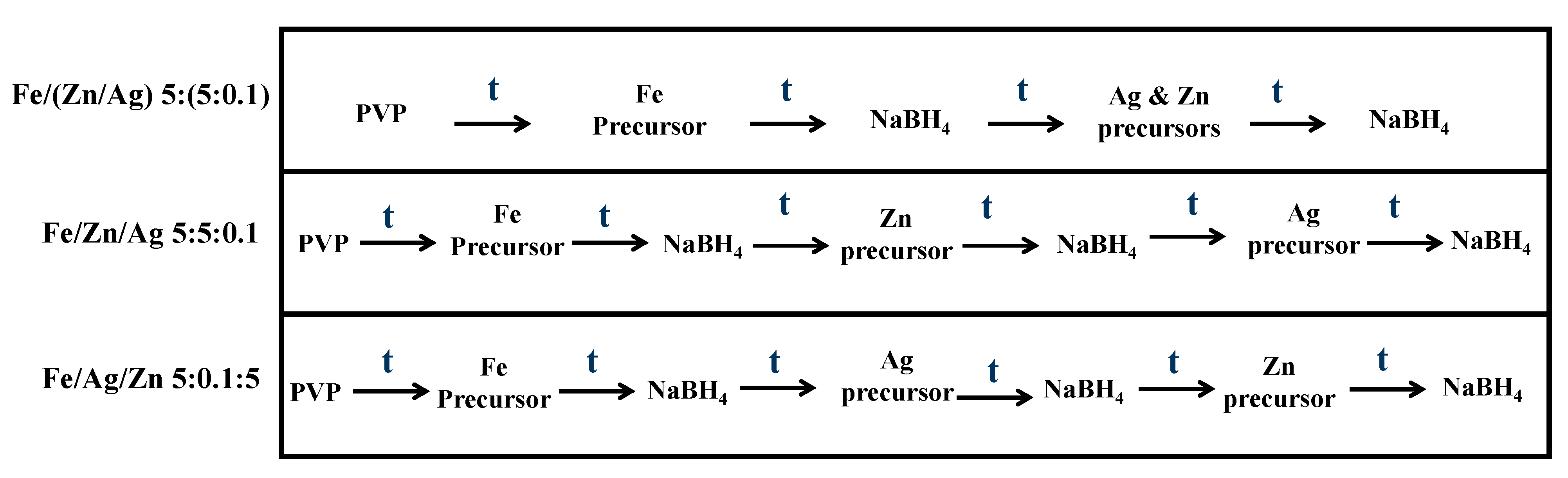

2.2.1. Synthesis of Nanoparticles

2.2.2. Characterization of Nanoparticles

2.3. Methyl Orange Degradation Tests and Analysis

2.4. Kinetic Study

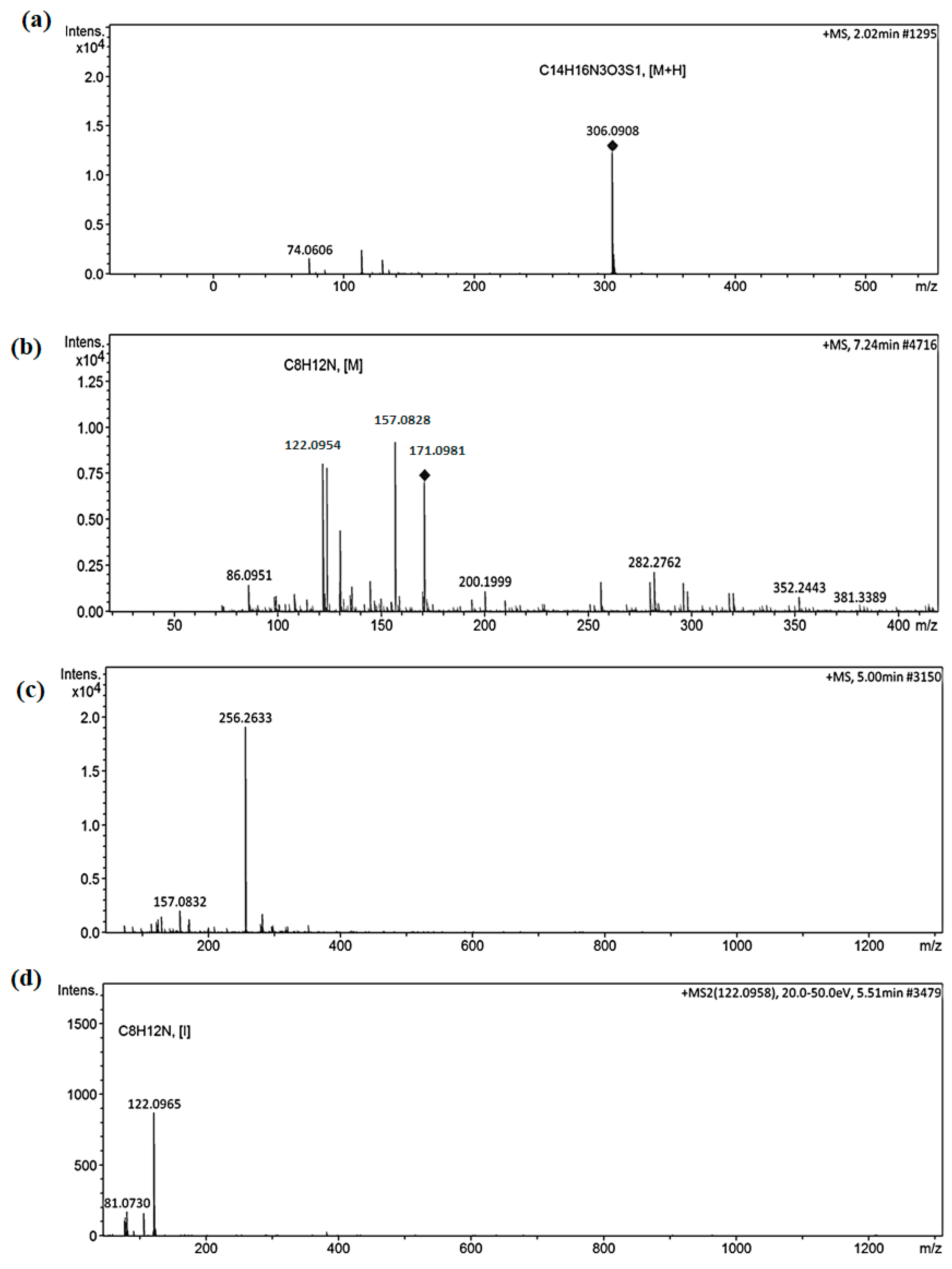

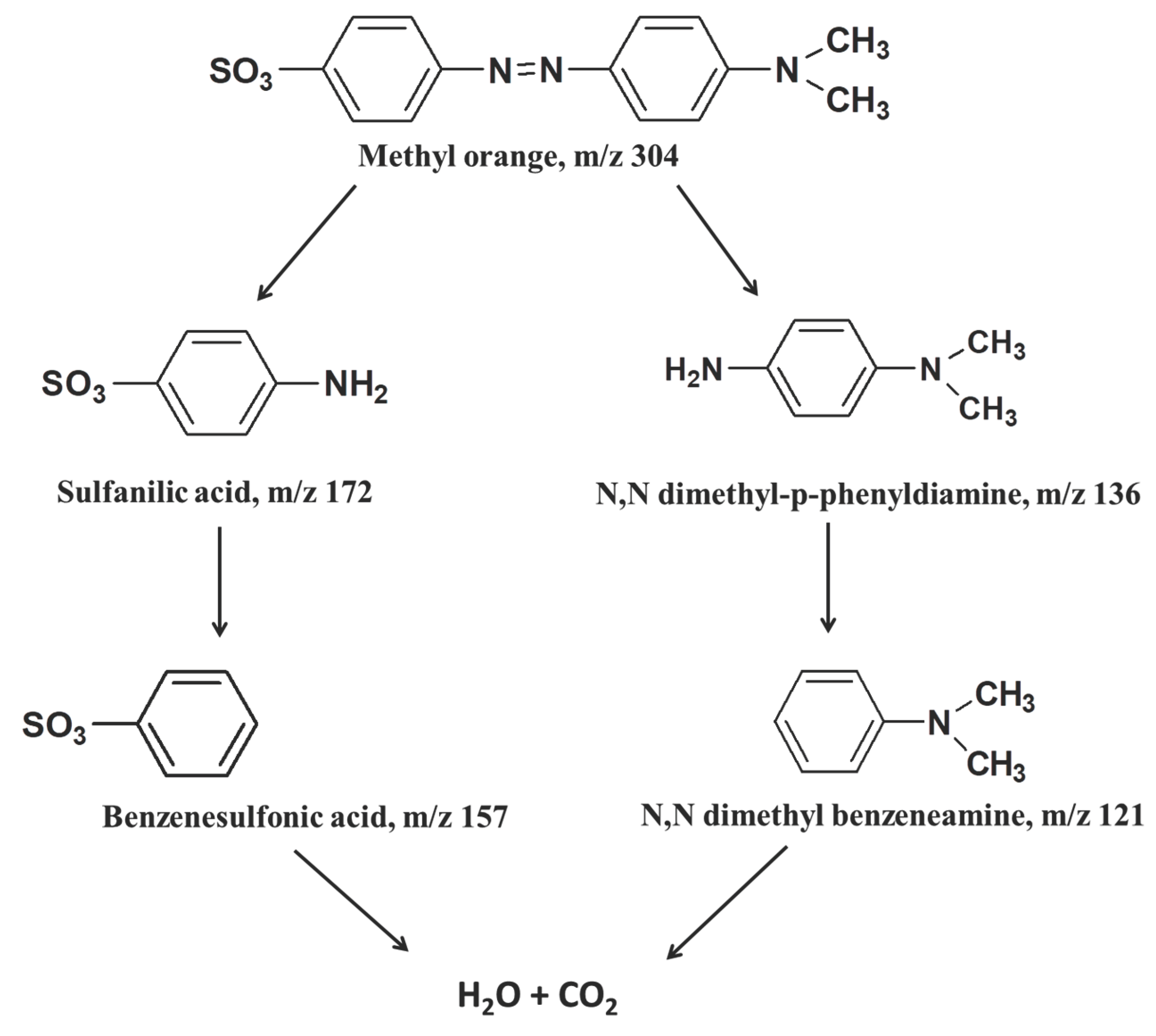

2.4.1. Analysis of Methyl Orange Degradation Products and Pathway

3. Results and Discussion

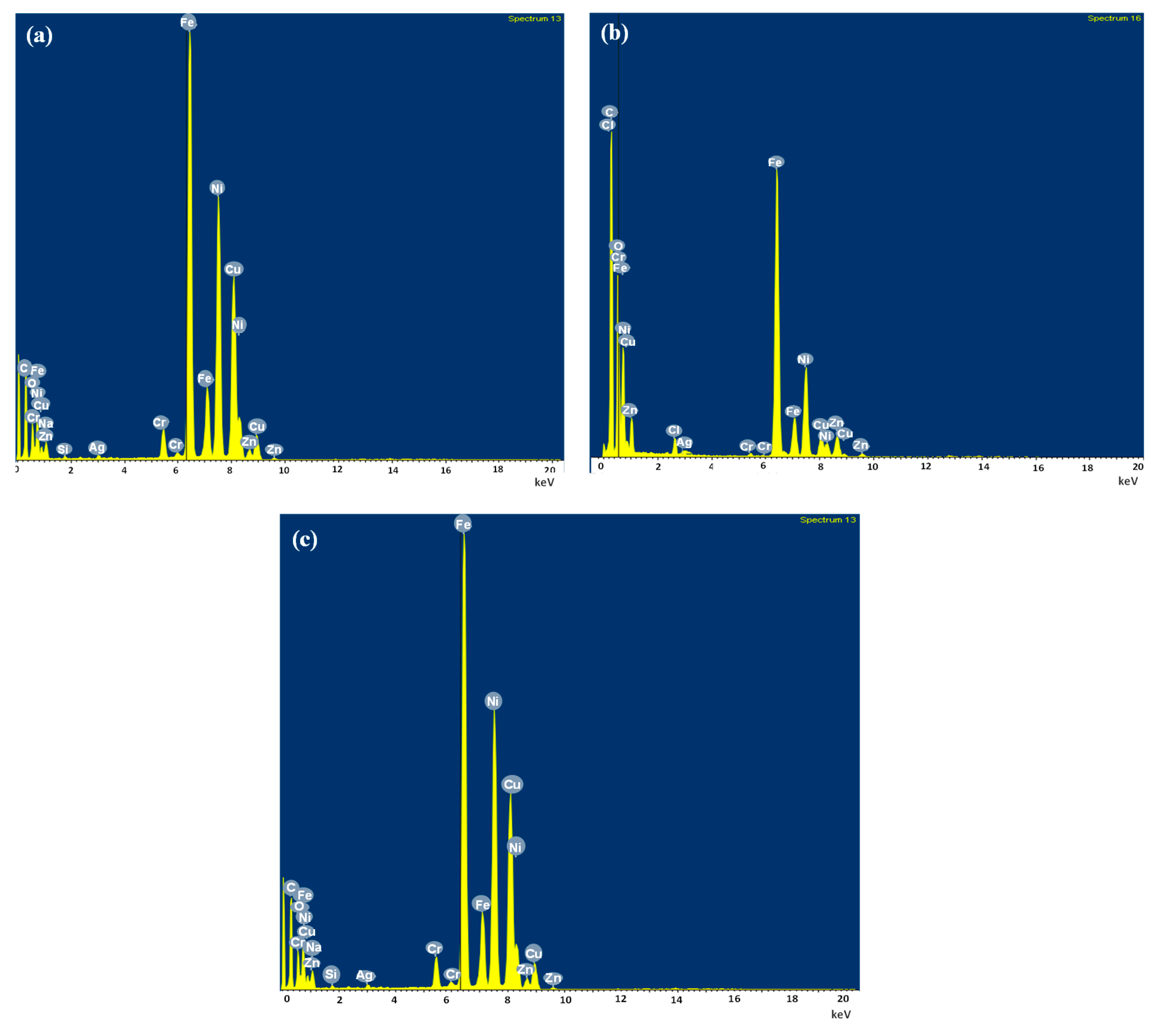

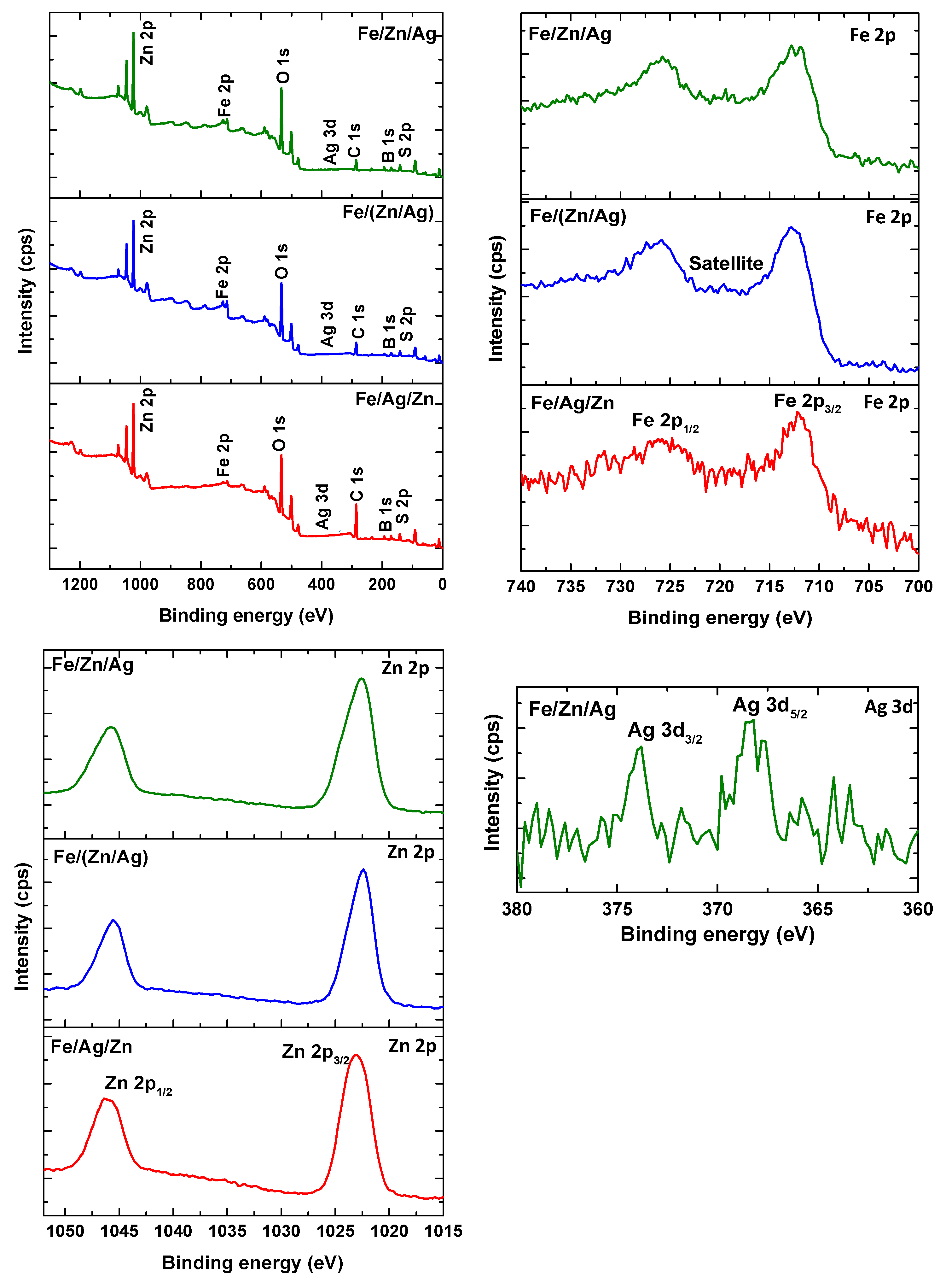

3.1. Characterization of the Catalyst

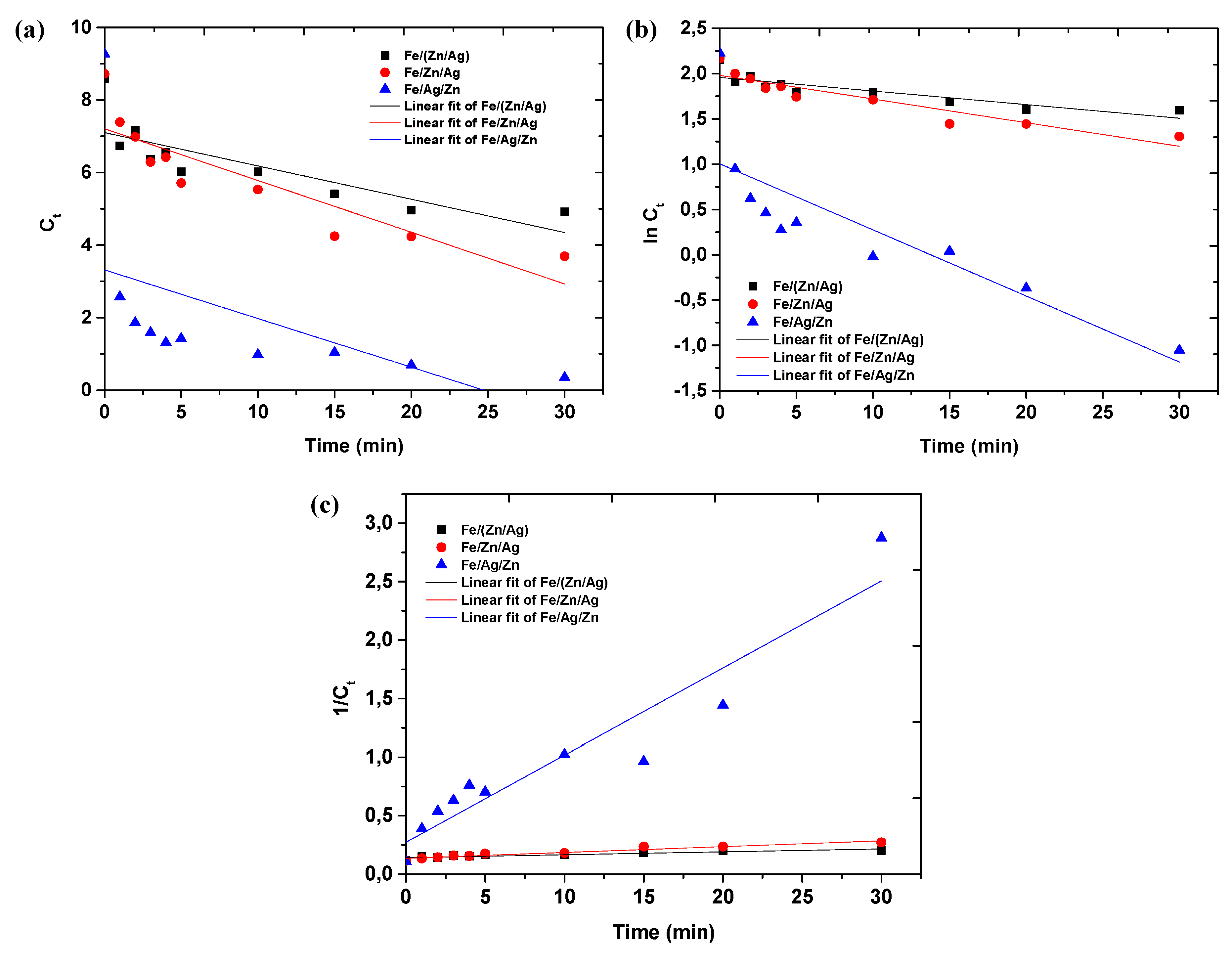

3.2. Effect of Metal Addition Sequence on Methyl Orange Degradation

| R2 values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeroth-order | First-order | Second-order | |

| Fe/(Zn/Ag) | 0.6363 | 07229 | 0.8052 |

| Fe/Zn/Ag | 0.7655 | 0.8578 | 0.9506 |

| Fe/Ag/Zn | 0.1662 | 0.6537 | 0.9107 |

3.3. Evaluating the Catalytic Activity of the Trimetallic Systems

3.4. Effect of Reaction Conditions on Catalyst Performance

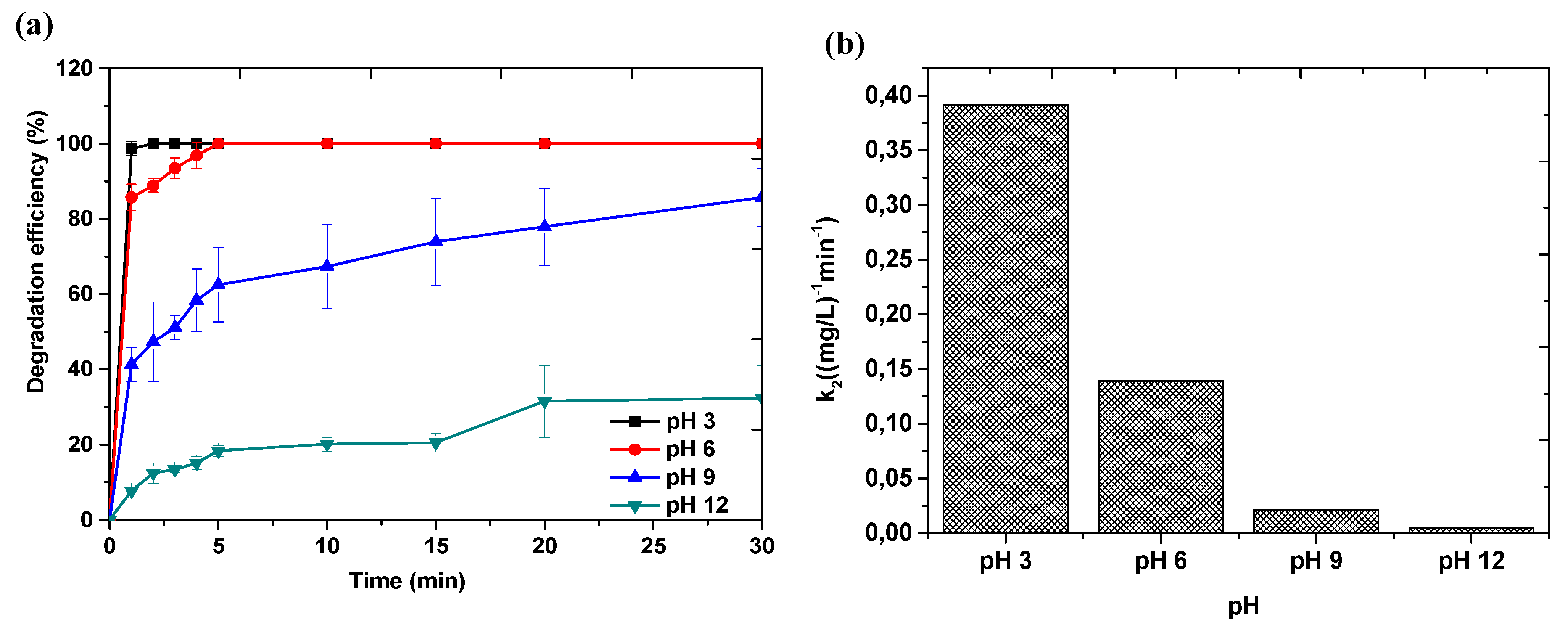

3.4.1. Effect of Initial Solution pH

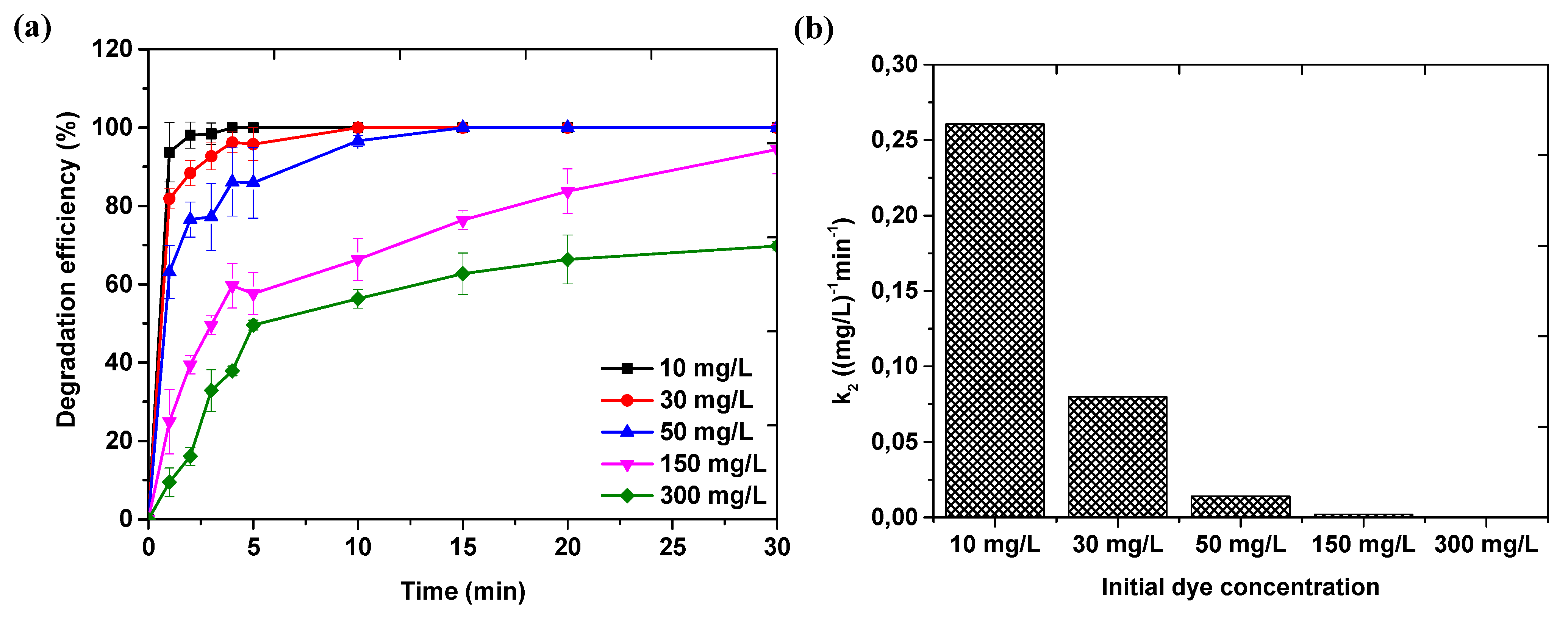

3.4.2. Effect of Initial Methyl Orange Dye Concentration

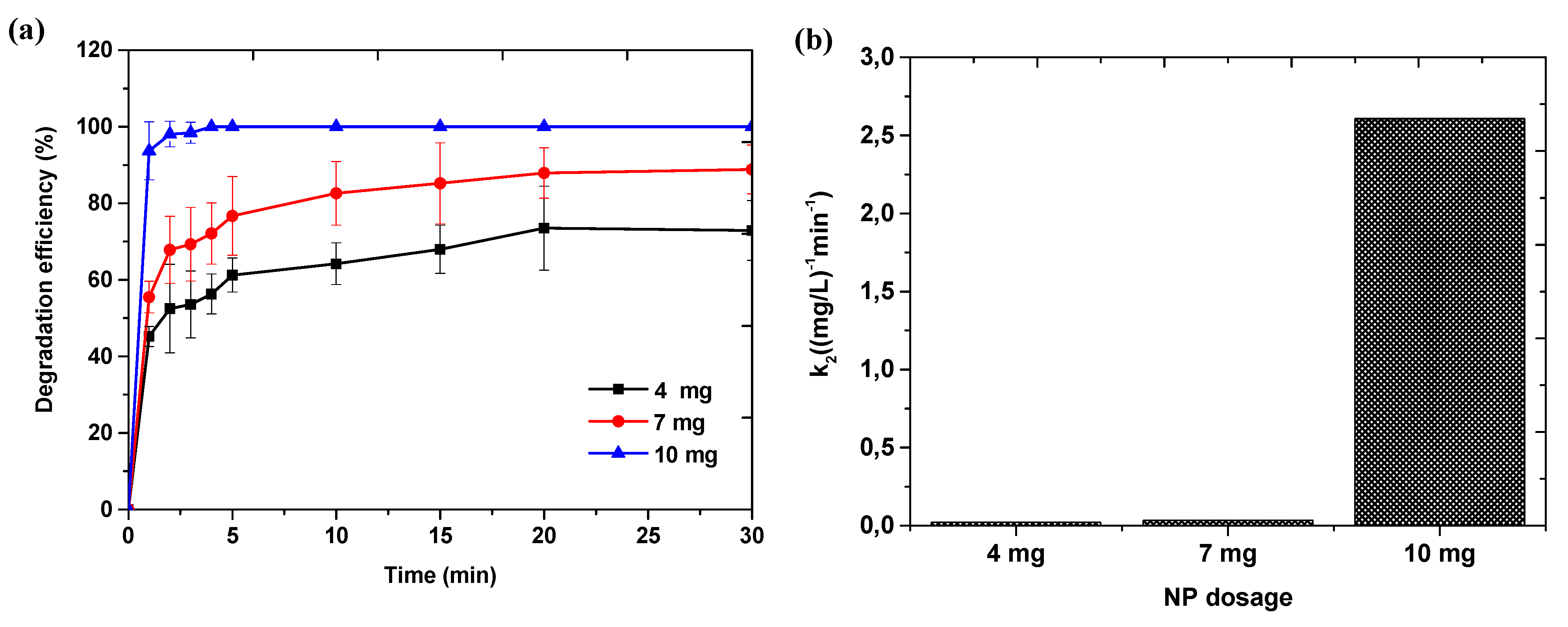

3.4.3. Effect of Initial Nanoparticle Dosage

3.5. Methyl Orange Degradation Products and Pathway

3.6. Probable Methyl Orange Degradation Mechanism by Fe/Ag/Zn Trimetallic Nanoparticles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- H. Yukseler, N. Uzal, E. Sahinkaya, M. Kitis, F.B. Dilek, U. Yetis, Analysis of the best available techniques for wastewaters from a denim manufacturing textile mill. J. Environ. Manage. 203 (2017) 1118–1125. [CrossRef]

- L. Aljerf, High-efficiency extraction of bromocresol purple dye and heavy metals as chromium from industrial effluent by adsorption onto a modified surface of zeolite: Kinetics and equilibrium study. J. Environ. Manage. 225 (2018) 120–132. [CrossRef]

- I.G. Laing, The impact of effluent regulations on the dyeing industry. Rev. Prog. Color. Relat. Top. 21 (1991) 56–71. [CrossRef]

- F. Gahr, F. Hermanutz, W. Oppermann, Ozonation-an important technique to comply with new German laws for textile wastewater treatment. Interciencia 30 (1994) 255–263. [CrossRef]

- P.C. Vandevivere, R. Bianchi, W. Verstraete, Review treatment and reuse of wastewater from the textile wet-processing industry: review of emerging technologies. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 72 (1998) 289–302. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Yaseen, M. Scholz, Textile dye wastewater characteristics and constituents of synthetic effluents: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16 (2019) 1193–1226. [CrossRef]

- N.C. Cinperi, E. Ozturk, N.O. Yigit, M. Kitis, Treatment of woolen textile wastewater using membrane bioreactor, nanofiltration and reverse osmosis for reuse in production processes. J. Clean. Prod. 223 (2019) 837–848. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Sarker, M. Chowdhury, A. Deb, Reduction of color intensity from textile dye wastewater using microorganisms: A review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 8 (2019) 3407–3415. [CrossRef]

- D. Mikucioniene, D.M. García, R. Repon, R. Mila, G. Priniotakis, Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review. AUTEX Res. J. 24 (2024) 1–27. [CrossRef]

- S. Popli, U.D. Patel, Destruction of azo dyes by anaerobic–aerobic sequential biological treatment: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 12 (2015) 405–420. [CrossRef]

- I.K. Konstantinou, T.A. Albanis, TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations: A review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 49 (2004) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- K.-T. Chung, C.E. Cerniglia, Mutagenicity of azo dyes: Structure-activity relationships. Mutat. Res. 277 (1992) 201–220. [CrossRef]

- P.A. Carneiro, G.A. Umbuzeiro, D.P. Oliveira, M.V.B. Zanoni, Assessment of water contamination caused by a mutagenic textile effluent/dyehouse effluent bearing disperse dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 174 (2010) 694–699. [CrossRef]

- P.I.M. Firmino, M.E.R. da Silva, F.J. Cervantes, A.B. dos Santos, Colour removal of dyes from synthetic and real textile wastewaters in one- and two-stage anaerobic systems. Bioresour. Technol. 101 (2010) 7773–7779. [CrossRef]

- D. Chandran, Review of the textile industries waste water treatment methodologies. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 7 (2015) 392–403.

- M. T. Moghadam, F. Qaderi, Modeling of petroleum wastewater treatment by Fe/Zn nanoparticles using the response surface methodology and enhancing the efficiency by scavenger. Results Phys. 15 (2019) 102566. [CrossRef]

- P.K. Boruah, B. Sharma, I. Karbhal, M. V. Shelke, M.R. Das, Ammonia-modified graphene sheets decorated with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the photocatalytic and photo-Fenton degradation of phenolic compounds under sunlight irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 325 (2017) 90–100. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, S. Zhou, F. Yang, H. Qin, Y. Kong, Degradation of phenol in industrial wastewater over the F-Fe/TiO2 photocatalysts under visible light illumination. Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 24 (2016) 1712–1718. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Alamo-nole, S. Bailon-Ruiz, T. Luna-Pineda, O. Perales-Perez, F.R. Roman, Photocatalytic activity of quantum dot–magnetite nanocomposites to degrade organic dyes in the aqueous phase. J. Mater. Chem. A 1 (2013) 5509–5516. [CrossRef]

- N. Rahman, Z. Abedin, M.A. Hossain, Rapid degradation of azo dyes using nano-scale zero valent iron. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 10 (2014) 157–163. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang, L. Gu, N. Zhu, K. Feng, H. Yuan, Z. Lou, Y. Li, A. Shan, Heavy metal recovery from electroplating wastewater by synthesis of mixed-Fe3O4@ SiO2/metal oxide magnetite photocatalysts. Green Chem. 16 (2014) 2696–2705. [CrossRef]

- T.N. Boronina, L. Dieken, I. Lagadic, K.J. Klabunde, Zinc-silver, zinc-palladium, and zinc-gold as bimetallic systems for carbon tetrachloride dechlorination in Water. J. Hazard. Subst. Res. 1 (1998) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- P. Srinoi, Y.T. Chen, V. Vittur, M.D. Marquez, T.R. Lee, Bimetallic nanoparticles: enhanced magnetic and optical properties for emerging biological applications. Appl. Sci. 8 (2018) 1106. [CrossRef]

- R.K. Gautam, V. Rawat, S. Banerjee, M.A. Sanroman, S. Soni, S.K. Singh, M.C. Chattopadhyaya, Synthesis of bimetallic Fe–Zn nanoparticles and its application towards adsorptive removal of carcinogenic dye malachite green and Congo red in water. J. Mol. Liq. 212 (2015) 227–236. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, J. Su, X. Jin, Z. Chen, M. Megharaj, R. Naidu, Functional clay supported bimetallic nZVI/Pd nanoparticles used for removal of methyl orange from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 262 (2013) 819–825. [CrossRef]

- Z. Marková, K.M.H. Šišková, J. Filip, J. Čuda, M. Kolář, K. Šafářová, I. Medřík, R. Zbořil, Air stable magnetic bimetallic Fe−Ag nanoparticles for advanced antimicrobial treatment and phosphorus removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (2013) 5285–5293. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, C. Liu, L. Tong, J. Li, R. Luo, J. Qi, Y. Li, L. Wang, Iron–copper bimetallic nanoparticles supported on hollow mesoporous silica spheres: an effective heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for orange II degradation. RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 69593–69605. [CrossRef]

- N. Basavegowda, K. Mishra, Y.R. Lee, Trimetallic FeAgPt alloy as a nanocatalyst for the reduction of 4-nitroaniline and decolorization of rhodamine B: A comparative study. J. Alloys Compd. 701 (2017) 456–464. [CrossRef]

- A. Roy, S. Kunwar, U. Bhusal, D.S. Idris, S. Alghamdi, K. Chidambaram, A.A. Qureshi, N.F. Qusty, A.A. Khan, K. Kaur, A. Roy, Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles. Green Process. Synth. 13 (2024) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Z. Khan, Trimetallic nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic degradation of formic acid for hydrogen generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44 (2019) 11503–11513. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, D. Yuan, Y. Zhang, B. Lai, Exploring the mechanism and kinetics of Fe-Cu-Ag trimetallic particles for p-nitrophenol reduction. Chemosphere 186 (2017) 132–139. [CrossRef]

- M. Kgatle, K. Sikhwivhilu, G. Ndlovu, N. Moloto, Degradation kinetics of methyl orange dye in water using trimetallic Fe/Cu/Ag nanoparticles. Catalysts 11 (2021) 428. [CrossRef]

- M. Rabiei, A. Palevicius, A. Monshi, S. Nasiri, A. Vilkauskas, G. Janusas, Comparing methods for calculating nano crystal size of natural hydroxyapatite using x-ray diffraction. Nanomaterials 10 (2020) 1–21. [CrossRef]

- M. Boudart, Turnover rates in heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 95 (1995) 661–666. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Ruiz-Torres, R.F. Araujo-Martínez, G.A. Martínez-Castañón, J.E. Morales-Sánchez, J.M. Guajardo-Pacheco, J. González-Hernández, T.J. Lee, H.S. Shin, Y. Hwang, F. Ruiz, Preparation of air stable nanoscale zero valent iron functionalized by ethylene glycol without inert condition. Chem. Eng. J. 336 (2018) 112–122. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Dhal, B.G. Mishra, G. Hota, Hydrothermal synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic activity of ternary Fe2O3/ZnFe2O4/ZnO nanocomposite through cascade electron transfer. RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 58072–58083. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, C. Liu, I. Hussain, C. Li, J. Li, X. Sun, J. Shen, W. Han, L. Wang, Iron–copper bimetallic nanoparticles supported on hollow mesoporous silica spheres: the effect of Fe/Cu ratio on heterogeneous Fenton degradation of a dye. RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 54623–54635. [CrossRef]

- X. Weng, Z. Chen, Z. Chen, M. Megharaj, Clay supported bimetallic Fe/Ni nanoparticles used for reductive degradation of amoxicillin in aqueous solution: Characterization and kinetics. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 443 (2014) 404–409. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhou, Y. Li, T.T. Lim, Catalytic hydrodechlorination of chlorophenols by Pd/Fe nanoparticles: Comparisons with other bimetallic systems, kinetics and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 76 (2010) 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fang, X. Qiu, J. Chen, X. Qiu, Debromination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers by Ni/Fe bimetallic nanoparticles: Influencing factors, kinetics, and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 185 (2011) 958–969. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Ruiz-Torres, R.F. Araujo-Martínez, G.A. Martínez-Castañón, J.E. Morales-Sánchez, T.J. Lee, H.S. Shin, Y. Hwang, A. Hurtado-Macías, F. Ruiz, A cost-effective method to prepare size-controlled nanoscale zero-valent iron for nitrate reduction. Environ. Eng. Res. 24 (2019) 463–473. [CrossRef]

- P. Scardi, M. Leoni, K.R. Beyerlein, On the modelling of the powder pattern from a nanocrystalline material. Zeitschrift Fur Krist. 226 (2011) 924–933. [CrossRef]

- K. Shameli, M. Bin Ahmad, A. Zamanian, P. Sangpour, P. Shabanzadeh, Y. Abdollahi, M. Zargar, Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Curcuma longa tuber powder. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7 (2012) 5603–5610. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Abdullah, S. Awad, J. Zaraket, C. Salame, Synthesis of ZnO nanopowders by using Sol-gel and studying their structural and electrical properties at different temperature. Energy Procedia 119 (2017) 565–570. [CrossRef]

- H. Wasly, X-Ray analysis for determination the crystallite size and lattice strain in ZnO nanoparticles. J. Al-Azhar Univ. Eng. Sect. 13 (2018) 1312–1320. [CrossRef]

- P. Vanysek, Electrode Potentials. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 92nd Edition, 1982.

- S. Mülhopt, S. Diabaté, M. Dilger, C. Adelhelm, C. Anderlohr, T. Bergfeldt, J.G. de la Torre, Y. Jiang, E. Valsami-Jones, D. Langevin, I. Lynch, E. Mahon, I. Nelissen, J. Piella, V. Puntes, S. Ray, R. Schneider, T. Wilkins, C. Weiss, H.R. Paur, Characterization of nanoparticle batch-to-batch variability. Nanomaterials 8 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Su, X. Zhou, C. Dai, A.A. Keller, A new insight on the core–shell structure of zerovalent iron nanoparticles and its application for Pb(II) sequestration. J. Hazard. Mater. 263 (2013) 685– 693. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liang, C.-C. Wang, Surface crystal feature-dependent photoactivity of ZnO–ZnS composite rods via hydrothermal sulfidation. RSC Adv. 8 (2018) 5063–5070. [CrossRef]

- N.T. Mai, T.T. Thuy, D.M. Mott, S. Maenosono, Chemical synthesis of blue-emitting metallic zinc nano-hexagons. CrystEngComm 15 (2013) 6606. [CrossRef]

- N.M. Shamhari, B.S. Wee, S.F. Chin, K.Y. Kok, Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles with small particle size distribution. Acta Chim. Slov. 65 (2018) 578–585. [CrossRef]

- M.T. Zin, J. Borja, H. Hinode, W. Kurniawan, Synthesis of bimetallic fe/cu nanoparticles with different copper loading ratios. Int. J. Chem. Nucl. Metall. Mater. Eng. 7 (2013) 669–673. [CrossRef]

- R. Sharma, A. Dhillon, D. Kumar, Mentha-Stabilized silver nanoparticles for high-performance colorimetric detection of Al(III) in aqueous systems. Sci. Rep. 8 (2018) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- J. Trujillo-Reyes, V. Sánchez-Mendieta, A. Colín-Cruz, R.A. Morales-Luckie, Removal of indigo blue in aqueous solution using Fe/Cu nanoparticles and C/Fe–Cu nanoalloy composites. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 207 (2010) 307–317. [CrossRef]

- S. Luo, S. Yang, X. Wang, C. Sun, Reductive degradation of tetrabromobisphenol using Iron–Silver and Iron–Nickel bimetallic nanoparticles with microwave energy. Environ. Eng. Sci. 29 (2012) 453–460. [CrossRef]

- S. Mossa Hosseini, B. Ataie-Ashtiani, M. Kholghi, Nitrate reduction by nano-Fe/Cu particles in packed column. Desalination 276 (2011) 214–221. [CrossRef]

- K.J. Carroll, D.M. Hudgins, S. Spurgeon, K.M. Kemner, B. Mishra, M.I. Boyanov, L.W. Brown, M.L. Taheri, E.E. Carpenter, One-pot aqueous synthesis of Fe and Ag core/shell nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 22 (2010) 6291–6296. [CrossRef]

- W.J. Tseng, Y.-C. Chuang, Chemical Preparation of Bimetallic Fe/Ag core/shell composite nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 18 (2017) 2790–2796. [CrossRef]

- M. Fiedot, O. Rac, P. Suchorska-Woźniak, I. Karbownik, H. Teterycz, Polymer-surfactant interactions and their influence on zinc oxide nanoparticles morphology. Manuf. Nanostructures (2014) 108–128.

- S.N. Zhu, G. hua Liu, K.S. Hui, Z. Ye, K.N. Hui, A facile approach for the synthesis of stable amorphous nanoscale zero-valent iron particles. Electron. Mater. Lett. 10 (2014) 143–146. [CrossRef]

- W. Liang, C. Dai, X. Zhou, Y. Zhang, Application of zero-valent iron nanoparticles for the removal of aqueous zinc ions under various experimental conditions. PLoS One 9 (2014) e85686. [CrossRef]

- R.P.P. Singh, I.S. Hudiara, S.B. Rana, Effect of calcination temperature on the structural, optical and magnetic properties of pure and Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Pol. 34 (2016) 451–459. [CrossRef]

- B. Akbari, M.P. Tavandashti, M. Zandrahimi, Particle size characterization of nanoparticles: A practical approach. Iran. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 8 (2011) 48–56.

- A. Ruys, Processing, Structure, and Properties of Alumina Ceramics, Alumina Ceramics: Biomedical and clinical applications. First edition, Woodhead Publishing, Sawston, United Kingdom, 2019, pp. 71-121.

- T.A. Tengku Sallehudin, M.N. Abu Seman, S.M.S. Tuan Chik, Preparation and characterization silver nanoparticle embedded polyamide nanofiltration (NF) membrane. MATEC Web Conf. 150 (2018) 02003. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, R. Jin, Catalysis by gold nanoparticles: carbon-carbon coupling reactions. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2 (2013) 529–545. [CrossRef]

- K.H. Kumar, N. Venkatesh, H. Bhowmik, A. Kuila, Metallic nanoparticle: A review. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 4 (2018) 3765–3775. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Bransfield, D.M. Cwiertny, K. Livi, D.H. Fairbrother, Influence of transition metal additives and temperature on the rate of organohalide reduction by granular iron: implications for reaction mechanisms. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 76 (2007) 348–356. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Zhang, N. Yang, S.Q. Ni, V. Natarajan, H.A. Ahmad, S. Xu, X. Fang, J. Zhan, One-pot synthesis of highly active Ni/Fe nanobimetal by simultaneous ball milling and in situ chemical deposition. RSC Adv. 8 (2018) 26469–26475. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, D. Ji, X. Wang, L. Zang, Review on Nano zerovalent Iron (nZVI): From modification to environmental applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 51 (2017) 012004. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghauch, H.A. Assi, H. Baydoun, A.M. Tuqan, A. Bejjani, Fe0-based trimetallic systems for the removal of aqueous diclofenac: Mechanism and kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 172 (2011) 1033–1044. [CrossRef]

- L.P. Zhu, B.K. Zhu, L. Xu, Y.X. Feng, F. Liu, Y.Y. Xu, Corona-induced graft polymerization for surface modification of porous polyethersulfone membranes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253 (2007) 6052–6059. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao, F. Wang, Y. Wu, R. Naidu, Z. Chen, Comparison of degradation mechanisms of microcystin-LR using nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) and bimetallic Fe/Ni and Fe/Pd nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 285 (2016) 459–466. [CrossRef]

- R. Rodrigues, S. Betelu, S. Colombano, G. Masselot, T. Tzedakis, I. Ignatiadis, Reductive dechlorination of hexachlorobutadiene by a Pd/Fe microparticle suspension in dissolved lactic acid polymers: Degradation mechanism and kinetics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56 (2017) 12092–12100. [CrossRef]

- G.G. Muradova, S.R. Gadjieva, L. Di Palma, G. Vilardi, Nitrates removal by bimetallic nanoparticles in water. Chem. Eng. Trans. 47 (2016) 205–210. [CrossRef]

- F. Parvin, O.K. Nayna, S.M. Tareq, S.Y. Rikta, A.K. Kamal, Facile synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticle and synergistic effect of iron nanoparticle in the presence of sunlight for the degradation of DOM from textile wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 8 (2018) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- D.F. Paris, W.C. Steen, G.L. Baughman, J.T. Barnett, Second-Order model to predict microbial degradation of organic compounds in natural waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41 (1981) 603–609. [CrossRef]

- K.V.G. Ravikumar, S. Dubey, M. pulimi, N. Chandrasekaran, A. Mukherjee, Scale-up synthesis of zero-valent iron nanoparticles and their applications for synergistic degradation of pollutants with sodium borohydrideJ. Mol. Liq. 224 (2016) 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Z.X. Chen, X.Y. Jin, Z. Chen, M. Megharaj, R. Naidu, Removal of methyl orange from aqueous solution using bentonite-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 363 (2011) 601–607. [CrossRef]

- L. Han, S. Xue, S. Zhao, J. Yan, L. Qian, M. Chen, Biochar supported nanoscale iron particles for the efficient removal of methyl orange dye in aqueous solutions. PLoS One 10 (2015) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- A.D. Bokare, R.C. Chikate, C. V. Rode, K.M. Paknikar, Effect of surface chemistry of Fe-Ni nanoparticles on mechanistic pathways of azo dye degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41 (2007) 7437–7443. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Lin, S.L. Lo, Y.H. Liou, Dechlorination of trichloroethylene in aqueous solution by noble metal-modified iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 116 (2004) 219–228. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Lien, W. Zhang, Enhanced dehalogenation of halogenated methanes by bimetallic Cu/Al. Chemosphere 49 (2002) 371–378. [CrossRef]

- L.G. Devi, R. Shyamala, Photocatalytic activity of SnO2-α-Fe2O3 composite mixtures: Exploration of number of active sites, turnover number and turnover frequency. Mater. Chem. Front. 2 (2018) 796–806. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Kondrat, J.A. van Bokhoven, A perspective on counting catalytic active sites and rates of reaction using X-ray spectroscopy. Top. Catal. 62 (2019) 1218–1227. [CrossRef]

- S. Navalon, D. Amarajothi, A. Mercedes, M. Antonietti, H. Garcia, Active sites on graphene-based materials as metal-free catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (2017) 4501–4529. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Benck, T.R. Hellstern, J. Kibsgaard, P. Chakthranont, T.F. Jaramillo, Catalyzing the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) with molybdenum sulfide nanomaterials. ACS Catal. 4 (2014) 3957−3971. [CrossRef]

- N. Sobana, M. Swaminathan, The effect of operational parameters on the photocatalytic degradation of acid red 18 by ZnO. Sep. Purif. Technol. 56 (2007) 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Tsachpinis, Photodegradation of the textile dye Reactive Black 5 in the presence of semiconducting oxides. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 74 (1999) 349–357. [CrossRef]

- F. Rezaei, D. Vione, Effect of pH on zero valent iron performance in heterogeneous Fenton and Fenton-like processes: A review. Molecules 23 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Shih, C.P. Tso, L.Y. Tung, Rapid degradation of methyl orange with nanoscale zerovalent iron particles. Sustain. Environ. Res. 20 (2010) 137–143.

- N.A. Youssef, S.A. Shaban, F.A. Ibrahim, A.S. Mahmoud, Degradation of methyl orange using Fenton catalytic reaction. Egypt. J. Pet. 25 (2016) 317–321. [CrossRef]

- P. Niu, Photocatalytic Degradation of methyl orange in aqueous TiO2 Suspensions. Asian J. Chem. 25 (2013) 1103–1106. [CrossRef]

- S. Luo, S. Yang, X. Wang, C. Sun, Reductive degradation of tetrabromobisphenol A over iron–silver bimetallic nanoparticles under ultrasound radiation. Chemosphere 79 (2010) 672–678. [CrossRef]

- J. Singh, Y.Y. Chang, J.R. Koduru, J.K. Yang, D.P. Singh, Rapid Fenton-like degradation of methyl orange by ultrasonically dispersed nano-metallic particles. Environ. Eng. Res. 22 (2017) 245–254. [CrossRef]

- E.M. El-Sayed, M.F. Elkady, M.M.A. El-Latif, Biosynthesis and characterization of zerovalent iron nanoparticles and its application in azo dye degradation. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 24 (2017) 541–547.

- T. Chen, Y. Zheng, J.M. Lin, G. Chen, Study on the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in water using Ag/ZnO as catalyst by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization ion-trap mass spectroscopy. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 19 (2008) 997–1003. [CrossRef]

- T. Shen, C. Jiang, C. Wang, J. Sun, X. Wang, X. Li, TiO2 modified abiotic-biotic process for the degradation of azo dye methyl orange. RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 58704–58712. [CrossRef]

- S. Xie, P. Huang, J.J. Kruzic, X. Zeng, H. Qian, A highly efficient degradation mechanism of methyl orange using Fe-based metallic glass powders. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- K. Dai, H. Chen, T. Peng, D. Ke, H. Yi, Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous suspension of mesoporous titania nanoparticles. Chemosphere 69 (2007) 1361–1367. [CrossRef]

- Q.B. Nguyen, D.P. Vu, T.H.C. Nguyen, T.D. Doan, N.C. Pham, T.L. Duong, D.L. Tran, G.L. Bach, H.C. Tran, N.N. Dao, Photocatalytic activity of BiTaO4 Nanoparticles for the degradation of methyl orange under visible light. J. Electron. Mater. 48 (2019) 3131–3136. [CrossRef]

- B. Lai, Q. Ji, Y. Yuan, D. Yuan, Y. Zhou, J. Wang, Degradation of ultrahigh concentration pollutant by Fe/Cu bimetallic system at high operating temperature. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 33 (2016) 207–215. [CrossRef]

- H.M.D.R. Herath, P.N. Shaw, P. Cabot, A.K. Hewavitharana, Effect of ionization suppression by trace impurities in mobile phase water on the accuracy of quantification by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24 (2010) 1502–1506. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Lu, J.K. Wang, S. Ferguson, T. Wang, Y. Bao, H.X. Hao, Mechanism, Synthesis and Modification of nano zerovalent iron in water treatment. Nanoscale 8 (2016) 9962–9975. [CrossRef]

- H. Lu, J. Wang, M. Stoller, T. Wang, Y. Bao, H. Hao, An overview of nanomaterials for water and wastewater treatment: Review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016 (2016) 4964828. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Tratnyek, A.J. Salter, J.T. Nurmi, V. Sarathy, Environmental applications of zerovalent metals: Iron vs. Zinc. ACS Symp. Ser. 1045 (2010) 165–178. [CrossRef]

- B. Kakavandi, A. Takdastan, S. Pourfadakari, M. Ahmadmoazzam, S. Jorfi, Heterogeneous catalytic degradation of organic compounds using nanoscale zero-valent iron supported on kaolinite: Mechanism, kinetic and feasibility studies. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 96 (2019) 329–340. [CrossRef]

- A.D. Bokare, R.C. Chikate, C. V Rode, K.M. Paknikar, Iron-nickel bimetallic nanoparticles for reductive degradation of azo dye Orange G in aqueous solution. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 79 (2008) 270–278. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, L. Wei, Q. Huang, L. Wang, S. Han, Reducing degradation of azo dye by zero-valent iron in aqueous solution. Chemosphere 38 (1999) 565–571. [CrossRef]

- T. Raychoudhury, T. Scheytt, Potential of zerovalent iron nanoparticles for remediation of environmental organic contaminants in water: A review. Water Sci. Technol. 68 (2013) 1425–1439. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Element | Peak binding energy (eV) | Atomic % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe/Zn/Ag | C 1s | 286.0 | 19.7 |

| O 1s | 533.0 | 48.7 | |

| Fe 2p | 712.4 | 2.5 | |

| Zn 2p | 1022.9 | 14.0 | |

| Ag 3d | 368.8 | 0.1 | |

| Fe/(Zn/Ag) | C 1s | 286.0 | 25.6 |

| O 1s | 532.9 | 45.4 | |

| Fe 2p | 713.4 | 6.8 | |

| Zn 2p | 1022.8 | 10.9 | |

| Fe/Ag/Zn | C 1s | 285.9 | 43.2 |

| O 1s | 533.4 | 33.3 | |

| Fe 2p | 712.9 | 2.3 | |

| Zn 2p | 1023.0 | 9.0 |

| NP used | Dosage (mg/L) | pH | Temperature (°C) | Dye concentration (mg/L) | Removal % | Reaction time (min) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nZVI | 150 | 7.0 | Room temperature | MO-40 | 98 | 30 | [78] |

| 2 | B nZVI | 500 | 6.5 | 30 | MO-100 | 79.5 | 10 | [79] |

| 3 | B* nZVI | 600 | 4.1 | Room temperature | MO-300 | 98.5 | 10 | [80] |

| 4 | B Fe/Pd | 500 | 6.2 | 25 | MO-200 | 91.9 | 20 | [25] |

| 5 | Fe/Ni | 3000 | - | 28±2 | Orange G-150 | 99.9 | 10 | [81] |

| 6 | Fe/Cu/Ag | 200 | 3.0 | Room temperature | MO-10 | 100.0 | 1 | [32] |

| 7 | Fe/Ag/Zn | 200 | 3.0 | Room temperature | MO-10 | 100.0 | 1 | Current study |

| Degradation efficiency (%) | Number of active sites (moles) | TON | TOF (min-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe/(Zn/Ag) | 42.21 | 4.09×10-5 | 1.5669 | 0.3134 |

| Fe/Zn/Ag | 46.73 | 4.09×10-5 | 1.7534 | 0.3507 |

| Fe/Ag/Zn | 100.00 | 4.09×10-5 | 3.7307 | 0.7461 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).