1. Introduction

Environmental pollution resulting from increased industrial activities poses numerous risks to human, animal, and ecosystem health [

1]. Over the past decades, major water sources, including lakes, rivers, and groundwater, have been contaminated by a wide range of pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, halogenated compounds, dioxins, pesticides, and synthetic dyes used in the textile, food, paper, and cosmetics industries [

1,

2]. Given the growing environmental crisis, urgent measures are required to enhance water quality, as conventional treatment techniques have proven largely ineffective in eliminating persistent organic contaminants [

3]. In this context, semiconductor-based nanocomposites have been extensively investigated for their potential in addressing these environmental challenges [

4]. Among the various photocatalysts, TiO₂ stands out due to its low cost, chemical inertness, non-toxicity, and high photostability. However, its practical application is hindered by two major drawbacks: a wide band gap (3.2 eV), which limits light absorption to the ultraviolet region, and a high recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [

5,

6,

7]. This rapid recombination reduces charge carrier migration to active sites, significantly lowering catalytic efficiency.

To overcome these limitations, various strategies were proposed to enhance TiO₂’s visible-light absorption and reduce its band gap. One promising approach involves doping with metal ions, such as manganese, which exhibits strong potential for broad optical absorption across the visible and infrared regions of the solar spectrum [

8,

9,

10]. However, metal doping introduces defect sites that can increase electron-hole recombination thereby compromising photocatalytic efficiency. Consequently, incorporating a non-metallic dopant has been explored as an effective means to suppress recombination and enhance photocatalytic performance under visible light [

4]. Since their discovery, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have emerged as ideal candidates for modifying TiO₂ due to their exceptional mechanical strength, large specific surface area, unique electronic properties, and outstanding chemical stability [

11]. The integration of CNTs into MTiO₂/CNT composites significantly mitigates electron-hole recombination, as excited electrons in the conduction band of MTiO₂ readily migrate to the CNTs [

6,

12]. Moreover, adsorbed O₂ molecules on the CNT surface can accept electrons, generating reactive species such as superoxide ions (O₂

•⁻) or hydroxyl radicals (

•OH), which accelerate the degradation of organic pollutants [

13]. Additionally, CNTs improve electron mobility and contribute to bandgap reduction, further enhancing TiO₂’s reactivity under visible light. These synergistic effects collectively optimize the photocatalytic efficiency of TiO₂ for environmental remediation applications [

11]. The sol-gel method is widely employed for nanomaterial fabrication due to its advantages, including low cost, low processing temperature, and the ability to produce highly pure and homogeneous materials [

14,

15].

The present work focuses on the synthesis and characterization of an MTiO₂/CNT composite using the sol-gel method for the degradation of organic pollutants in water. The photocatalysts were analyzed using various techniques (XRD, XPS, UV-Vis), and their photocatalytic performance was evaluated by investigating the removal of methylene blue as an example of organic pollutants. The incorporation of CNTs in the MTiO2 is expected to significantly enhance photocatalytic activity compared to metal oxides alone.

XPS analysis revealed the presence of mixed-valent manganese, including Mn³⁺ and Mn⁴⁺. In addition, we were able to use a low concentration of manganese, which promotes the stability of the anatase phase. This approach contrasts with other studies that use higher concentrations and report mainly Mn²⁺ and Mn³⁺ [

16]. This is what has motivated this contribution.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Titanium tetra isopropoxide [Ti(OC3H7)4] and Manganese (II) acetate tetrahydrate (CH3COO)2Mn · 4H2O were purchased from BIOCHEM and used as starting precursors for Ti and Mn source, respectively, CNT (Nanocyl 7000, diameter 1−10 nm, length 60−100 nm, purity >90%) were purchased from Nanocyl. Other chemical reagents such as Nitric acid 65%, Ethanol 98.8 %, Sodium hydroxide and methylene blue were obtained from Sigma Aldrich

2.2. Preparation of Oxidized CNT and MTiO2/x-CNT Nanocomposites

CNTs were purified and oxidized before use. The oxidation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes was performed to purify them, open their ends, and cut them to facilitate their functionalization in composites. In this process, the CNTs were treated with an HNO3 solution. Briefly, a small amount of CNTs was oxidized with a 3M HNO3 solution and then sonicated for 6 hours at 70˚C. The mixture was subsequently rinsed and filtered with distilled water until the filtrate became neutral. The obtained material was then dried at 80˚C.

The MTiO2/x-CNT nanocomposites (x = 1, 2, 5, 10%) were synthesized using a sol-gel method. Specific amounts of titanium tetra-isopropoxide (TiO4C12H28, 98%) and manganese (II) acetate tetrahydrate (Mn(CH3CO2)2·4H2O) were mixed with ethanol in a 100 mL beaker. Different amounts of oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (1%, 2%, 5%, and 10% CNTs) were then added to the solution. The mixture was dispersed using an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic S60H, 220-240 V, 50-60 Hz, P 550 W) for 30 minutes. Subsequently, the precipitating agent, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at a concentration of 1 mol/L, was added dropwise under stirring until the pH reached 9. The solution was continuously stirred at room temperature for 3 hours, followed by aging at room temperature for 12 hours. The obtained precipitates were filtered using a Büchner funnel and washed several times with distilled water to remove residues and impurities until a neutral pH was achieved. The products were then dried in an oven at 100°C for 6 hours and subsequently calcined at 400°C for 2 hours. The synthesis of TiO2 and MTiO2 was carried out in the same way but without the presence of carbon nanotubes.

2.3. Characterization methods

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded for phase analysis and crystallite size measurement using an X’pert-PRO Panalytical powder diffractometer. The data recording was carried out within an angle range from 20° to 80° with a step of 0.013° using a 0.154056 nm wavelength radiation of copper anode (CuKα radiation, 45KV, 40 mA). The diffraction data were analyzed with a PanalyticalX’s Pert High Score Plus software. The crystallite size was estimated using Scherer’s equation.

XP spectra were recorded using a K Alpha+ apparatus (Thermo) fitted with a micro-focused, monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The samples were pressed on sample holders using double-sided adhesive tapes and outgassed in the fast-entry airlock overnight. The Avantage software, version 6.8.0, was used for digital acquisition and data processing. The spectra were calibrated against the C1s main peak component C-C/C-H set at 285 eV. The surface composition was determined by considering the manufacturer’s sensitivity factors.

3. Results and discussion

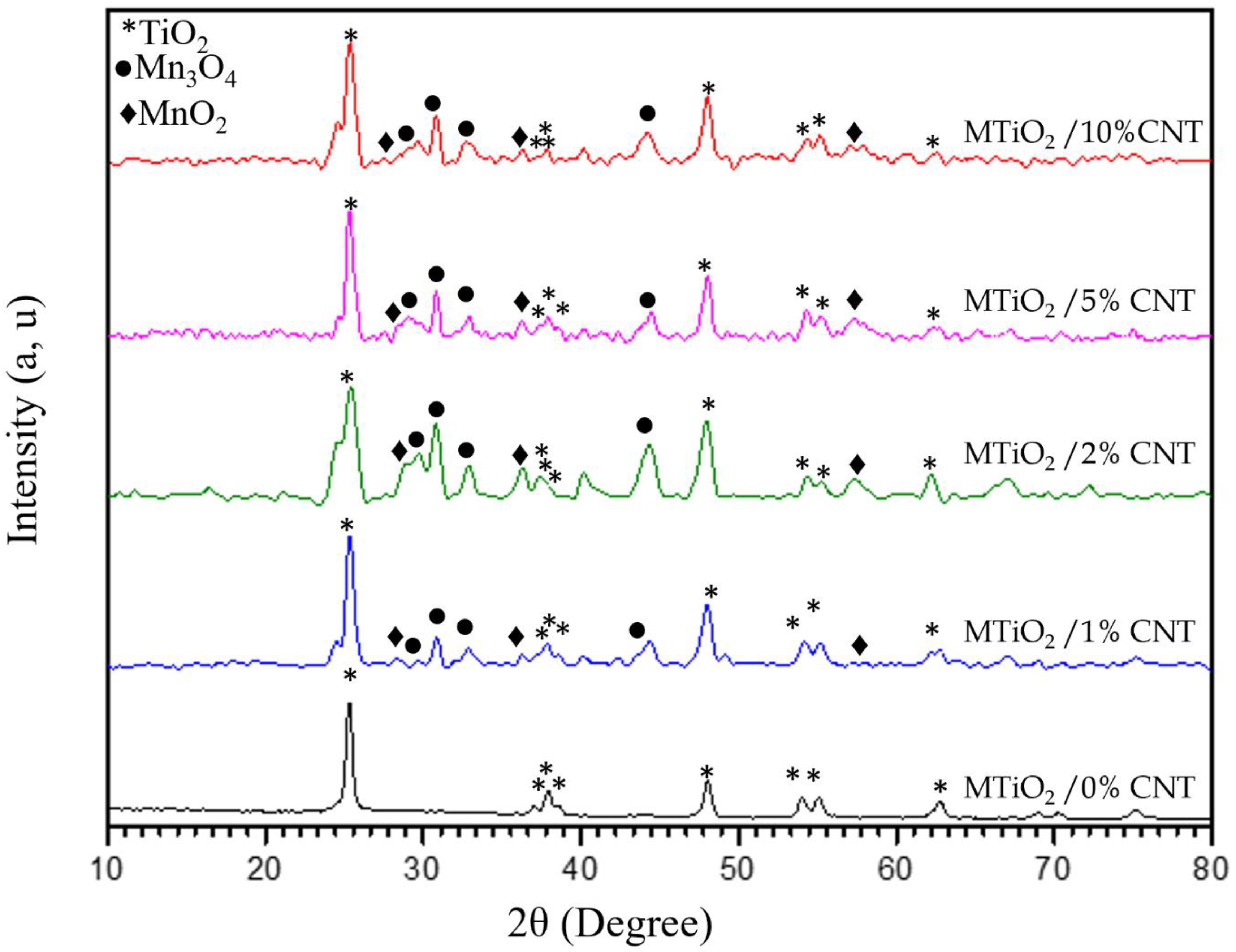

3.1. XRD analysis

XRD analysis of MTiO

2/x-CNT composites are shown in

Figure 1, where x takes values of 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10%. The diffraction patterns of these composites exhibit the same peaks as MTiO

2 (0%), located at the positions 2θ = 25.27°, 36.88°, 37.21°, 37.78°, 47.76°, 53.83, 55.02°, and 62.65. corresponding to corresponding to the diffraction planes (101), (103), (004), (112), (200), (105), (211), (116), (220), and (204). In addition to the TiO₂-related peaks, additional diffraction peaks indicate the presence of two manganese phases. The first phase corresponds to hausmannite (Mn₃O₄), with peaks observed at 2θ = 30.96°, 32.98°, 33.7°, 34.6°, and 43.40°, which can be assigned to the (100), (110), (111), (023), and (131) planes. The second identified phase is pyrolusite (MnO

2), confirmed by its characteristic peaks at 2θ = 28.62°, 35.77°, and 57.86°, corresponding to the (110), (101), and (211) planes. The results reveal that manganese-related diffraction peaks appear only after the incorporation of CNT into the composite. This suggests that the presence of CNT plays a crucial role in the formation of manganese phases. The absorption capacity of CNT contributes to the fixation of manganese to this phenomenon by facilitating the nucleation and stabilization of manganese-containing phases [

17].

The X-ray diffraction spectra data allowed us to approximately estimate the average size of the nanoparticles using the Debye-Scherrer formula.

where β (rad): The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction; θ (rad): The Bragg’s diffraction angle and λ=1.54060 A0 the X-Ray wavelength of the copper (Cu) radiation used in XRD. The grain sizes of all the samples with CNT percentages ranging from 0 to 10% vary from 8.56 to 16.43 nm. It is observed that there is a decrease in grain size with the increasing percentage of CNT, suggesting an influence of the CNT on the size of the nanoparticles.

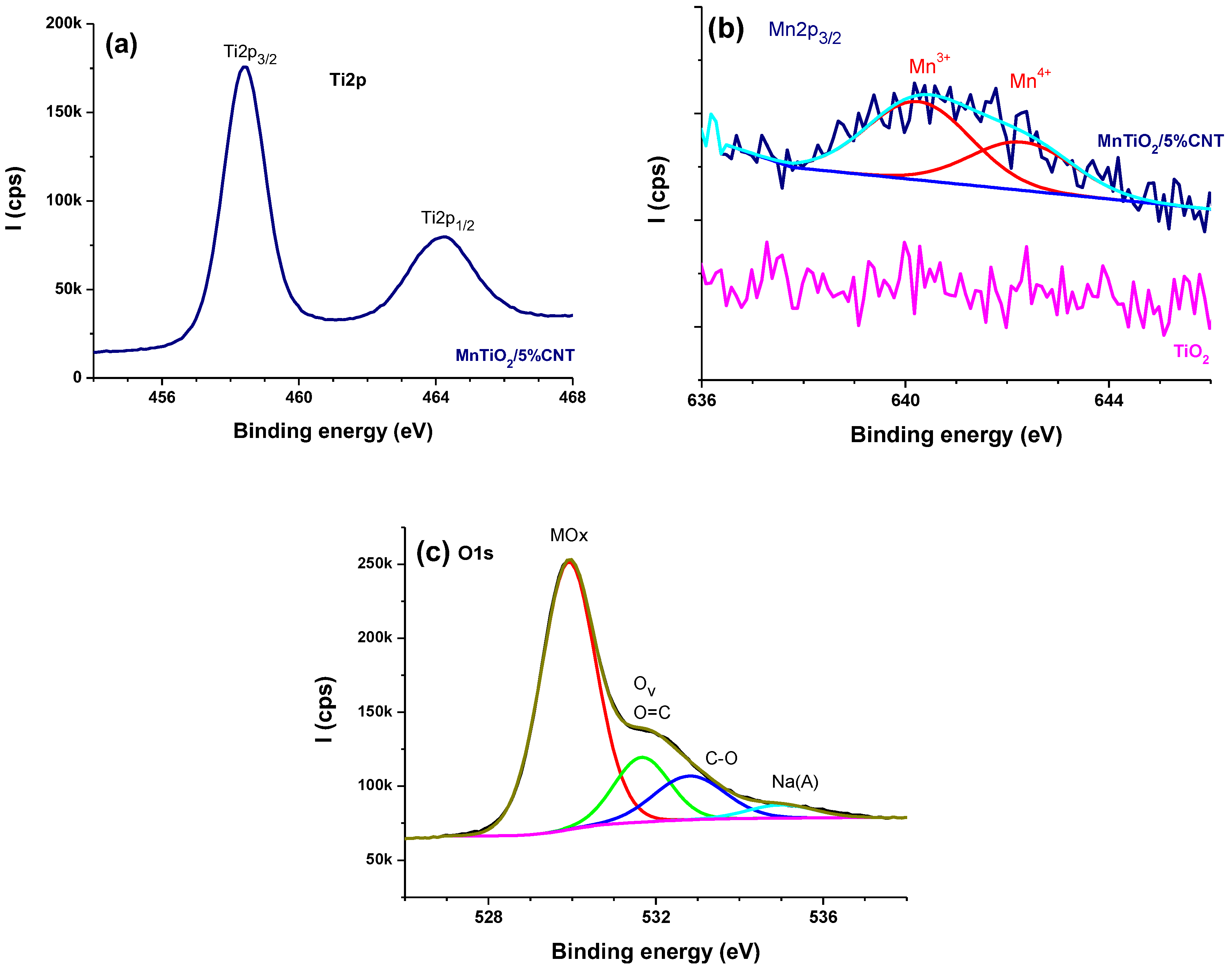

3.2. XPS analysis

Figure 2a-c displays the high resolution Ti2p (

Figure 2a) with Ti2p

3/2 main peak centered at 458.4 eV, typical of TiO

2 [

18].

Figure 2b displays the reference Mn2p region from TiO

2 without any manganese signal. For MTiO

2/5%CNT, Mn2p

3/2 (

Figure 2b) is fitted with two components centered at 640.4 and 642.7 eV, assigned to Mn

3+ and Mn

4+ oxidation states, respectively [

19], hence the mixed valence manganese in MTiO

2. This shows the formation of mixed The peak is a little bit noisy due to the low doping extent (1%).

Figure 2c displays the high-resolution O1s from MTiO

2/5%, peak-fitted with 3 main components due to Mox, mostly TiO

2, oxygen vacancy, and O=C, and O-C components centered at ~529.9, 531.7 and 532.8 eV, respectively. The peak centered at 529.9 eV is assigned to lattice oxygen and is mostly due to TiO

2 of which the binding energy position is 530.1±0.4 eV (deduced from the NIST XPS database, see (

https://srdata.nist.gov/xps/). MnOx cannot significantly contribute to this peak component. A fourth, minor component is due to the Na Auger peak, possibly due to sodium which remained physisorbed on the catalyst. Sodium is highly sensitive in XPS and could be probed easily. This peak is frequently, erroneously assigned to adsorbed water. It is to be noted that the peak centered at 531.7 eV is usually assigned to oxygen vacancy, indirectly probed by adsorbed O

=/O

2=species [

18]. However, this assignment is controversial as reported recently by the team of Ethan Crumlin [

20]. This peak is reported in the 531-532 eV range, which is indeed the case here, but it is to note that inorganics get easily contaminated with hydrocarbons. Surface contamination involves C-C/C-H, C-O, and O-C=O functional groups; therefore obviously at least O=C species contribute to the 531-432 eV component which could overestimate the proportion of oxygen vacancy (indirectly probed by XPS). Nevertheless, oxygen vacancies are in line with the catalytic properties of the materials, as will be discussed in the application section.

The surface elemental composition is reported in

Table 1. One key feature is that Mn/Ti is 0.011±0.002 for MTiO

2-CNT catalysts, matching 0.011 for pristine MTiO

2. The standard deviation is acceptable for such low doping of TiO

2 with Mn. Moreover, Mn/Ti is not affected by the introduction of CNTs in the reaction medium where MTiO

2 is synthesized. Concerning the manganese mixed valence, the Mn

3+/Mn

4+ atomic ratio for MTiO

2/CNT samples is 2.3±0.5, whereas that of pure MTiO

2 equals 2.2, suggesting no major effect of CNTs on the mixed valence distribution. There is very little oxidation of the CNTs as judged by 3.7 % oxygen, which points to the implementation of conductive CNTs in the composite catalyst.

Table 1 indicates a fairly high surface extent of carbon, due to hydrocarbon contamination, which is very prone to occur on inorganics. The addition of CNTs has no major effect on the carbon content, except for a 10% CNT addition. This is because CNTs have not been loaded on the surface of MTiO

2 but added before the co-precipitation process. It follows, that most of the CNTs are in the bulk and for this reason, they are better probed by XRD and not by XPS. The CNT

S could thus affect the overall catalytic process, facilitating charge transfer within the composite catalyst.

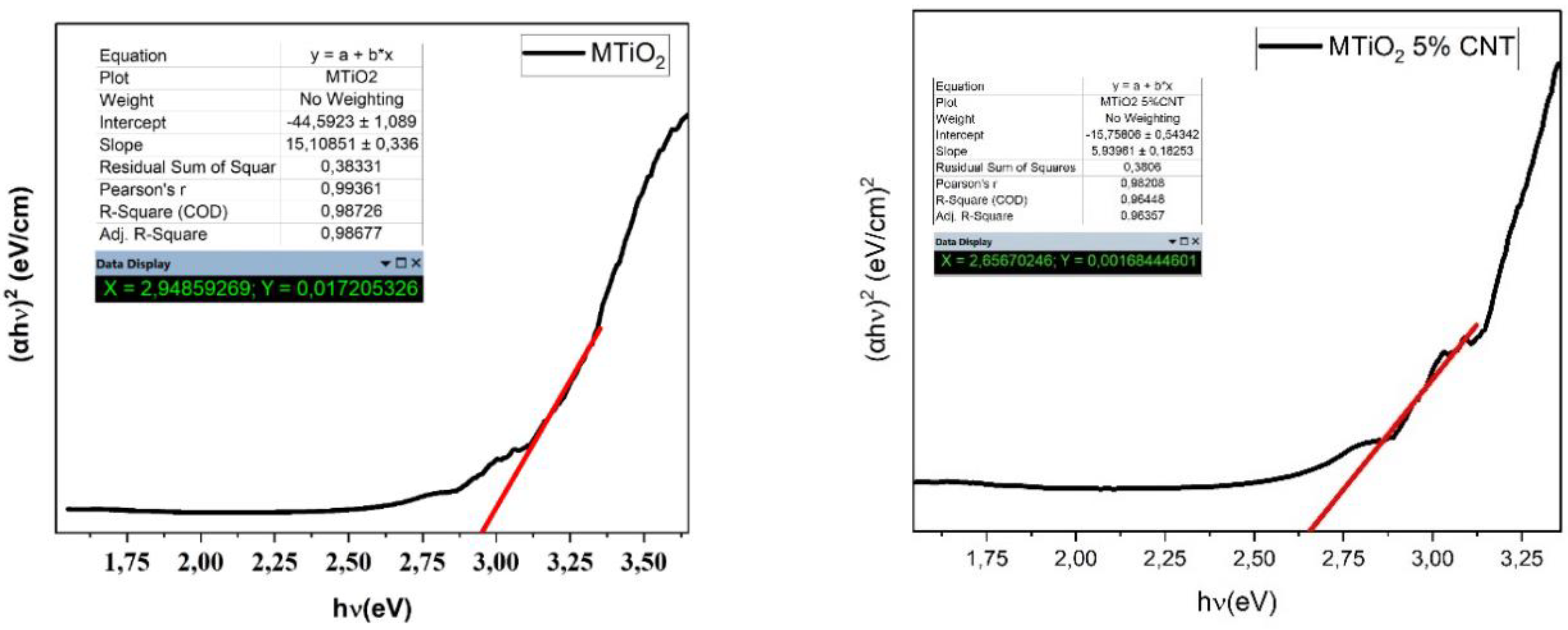

3.3. Optical properties

The band gap energy of MTiO₂ and MTiO₂/xCNTs nanocomposites was determined using UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, with the Kubelka-Munk equation applied to convert reflectance (R) into an equivalent absorption coefficient. Eq. (1)[

21,

22]

The optical band gap energy of all samples was estimated using Tauc’s equation

where α is the absorption coefficient, k is constant, h is the Planck’s constant, ѵ is light frequency, n =1 for direct electronic transition, n=4 for indirect electron transition, and Eg is the energy gap.

Table 2 shows The band gap values of MTiO

2, and MTiO

2/x%CNT nanocomposites, illustrating that the Eg value of MTiO

2 was 2.94 eV and decreased to 2.84, 2.70, 2.65 and 2.62 eV for the MTiO

2/CNT nanocomposites at 1, 2, 5, and 10% CNT, respectively. The decrease in the band gap (Eg) observed in the MTiO

2/CNT nanocomposites compared to MTiO

2 is possibly related to the narrowing of the bandgap energy and reflected the chemical bonding between MTiO

2 and the specific sites of carbon[

23]. This modification in band gap energy, induced by Mn and CNT doping, can further lead to a shift of the absorption edge toward the visible region in the MTiO₂/CNT sample compared to MTiO₂.

Figure 3.

Kubelka-Munk curves for estimating the band gap of MTiO2 (a) and MTiO2 5% CNT (b).

Figure 3.

Kubelka-Munk curves for estimating the band gap of MTiO2 (a) and MTiO2 5% CNT (b).

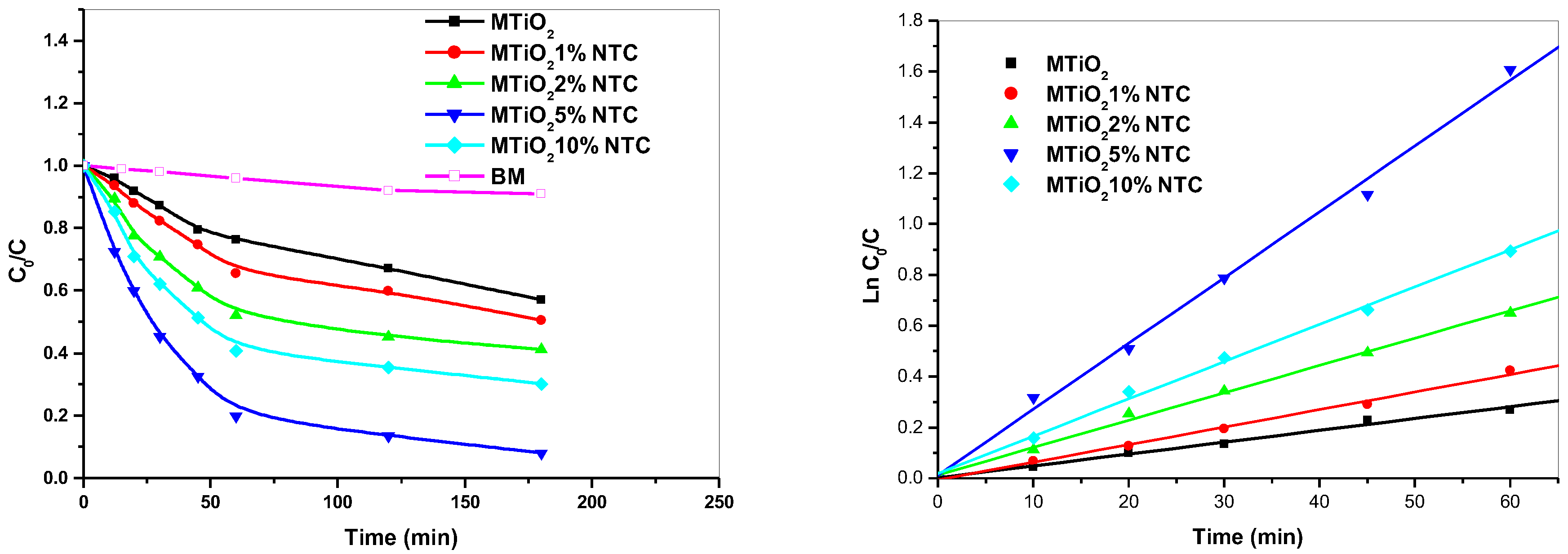

5. Catalytic performance of MTiO2 and MTiO2/x-CNT in the catalyzed MB degradation

The experiments were conducted in a 500 ml capacity cylindrical Pyrex reactor. A Philips TLAD 15W 05 lamp, emitting wavelengths in the UV-visible range between 300 and 450 nm with a maximum of emission at 365 nm, was used as the light source and positioned at 15 cm from the edge of the reactor. The Pyrex vessel and light sources were placed inside a closed chamber to prevent any UV radiation from escaping.

The photocatalytic activity was evaluated by measuring the degradation of methylene blue (MB) in a 250 mL aqueous solution of MB at a concentration of 8 ppm and a free pH, containing 0.125 g catalyst. To achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium, the suspension was stirred in the dark for 30 minutes. The experiments were then subjected to irradiation with polychromatic light (300–450 nm) for 180 minutes. At different time intervals, 3 mL of the suspension was taken and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 16 minutes to separate the composite particles. The resulting samples were analyzed using a Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 665 nm. A control experiment carried out under irradiation under irradiation with polychromatic light (300–450 nm) in the absence of MTiO2/x-CNT confirmed that the direct photolysis of MB was negligible, thus demonstrating the important catalytic role of the photocatalyst in degradation processes.

Figure 4(a) shows the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of the organic pollutant MB using various catalysts percent: MTiO

2 and MTiO

2/x-CNT (x = 1%, 2%, 5%, 10%). To evaluate the catalytic performance of these catalysts in the degradation of the MB dye, we compared the profiles of MB loss in various catalysts percent. The comparative tests were performed under identical conditions, specifically at ambient temperature and with an uncontrolled pH of the solution. The consumption of MB (8 ppm) under irradiation with polychromatic light (300–450 nm) was very slow in the presence of MTiO

2 about 40% had disappeared after 180 minutes of reaction. However, a larger enhancement of the reaction rate was observed in the presence of MTiO

2 dopant catalyst during the first 60 minutes, followed by a slower decrease that tends to stabilize towards the end of the reaction. This phenomenon suggests that the efficiency of the photocatalysts in the degradation of MB could be limited by the adsorption of intermediate molecules formed during the photo-reaction, which compete with MB molecules for reactive species [

24].

The degradation rate increases with the percentage of CNT, reaching 50%, 60%, and 92% of the consumption of MB, for x equal 1%, 2%, and 5% respectively, after the same reaction time. The CNT dopant can act as an electron conductor, thus reducing the accumulation of electrons in MTiO

2 and decreasing the recombination of electron-hole pairs. This observation is consistent with previous studies that have shown that the presence of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) creates trapping sites to capture photogenerated electrons from the conduction band of TiO

2, thereby allowing the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [

25]. This leads to a decrease in the electron-hole recombination rate, which increases the degradation efficiency. It was also noted that the decay of MB at 10% CNT decreased, about 70% of MB disappeared after 180 minutes of reaction. This is explained by the fact that CNT nanoparticles tend to aggregate on the surface of MTiO

2, which reduces light absorption and photocatalytic activity [

26].

The rate constants were determined by plotting ln C

0/C vs irradiation time, where

C0 is the initial MB concentration and

C is the concentration at t (

Figure 4(b)). In all cases, MB consumption followed pseudo-first-order kinetics. The rate coefficients, k, and R

2 values are reported in

Table 3.

The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of MTiO2 and MTiO2/x-CNT (x = 1%, 2%, 5%, 10%) decreased in the order:

MTiO2/5%-CNT > MTiO2/10%-CNT > MTiO2/2%-CNT > MTiO2/1%-CNT >MTiO2.

Photocatalytic degradation mechanisms

The degradation of MB initiates with the absorption of UV light by the MTiO2/CNT nanocomposite, generating excited electrons that migrate to the conduction band of MTiO₂. The separation of e⁻/h⁺ pairs is favored, limiting their recombination. In the presence of oxygen, the excited electrons form superoxide radicals, while the positive holes generated on the CNT oxidize hydroxide anions to produce hydroxyl radicals. These reactive species then decompose MB molecules through radical attack. The main reactions involved are presented in equations (3) to (7) [

17,

27]:

6. Conclusion

This work aimed to synthesize and characterize a ternary composite material based on titanium dioxide, manganese, and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MTiO₂/x-CNT) for application in the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB). The MTiO₂/x-CNT nanocomposites were prepared using the sol-gel method. The study revealed that the photocatalytic activity of this composite increases with the addition of CNTs up to a concentration of 5 %, beyond which it decreases. An excessive CNT content limits the light absorption of MTiO₂. Thus, the optimal CNT proportion in the MTiO₂/CNT composite is approximately 5 %.

The decrease in the band gap energy (Eg) observed in MTiO₂/CNT nanocomposites compared to MTiO₂ is possible due to the narrowing of the band gap energy, reflecting the chemical interaction between MTiO₂ and specific carbon sites. This band gap modification, induced by CNT doping, can also lead to a shift of the absorption edge toward the visible region, leading to a synergistic effect in the photocatalytic removal of methylene blue (MB). This effect is attributed to the ability of CNTs to act as excellent electron acceptors and conductors, thereby reducing the recombination of electron-hole pairs (e⁻/h⁺) and enhancing photon efficiency. Consequently, these nanocomposites show great potential as new photocatalytic materials. The optimal MTiO₂/CNT sample exhibited the best performance in removing MB, with a degradation rate exceeding 92% and a rate constant of 2.59 × 10⁻² min⁻¹, significantly higher than that of pure MTiO₂, which is 40%. These results suggest that this compound could have potential applications in other fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization : HA, HSTT, SH

Methodology : HA, HSTT, SH

Formal analysis : HA, HSTT, IB, NEHB, MB, MMC

Data curation : HA, MMC

Original draft : HA and HSTT

Writing, review and editing : HA, HSTT, MB, MMC

Acknowledgements

P. Decorse (Experimental Officer, ITODYS Lab) is acknowledged for assistance with XPS analyses.

References

- Ullah, R.; Naeemullah; Tuzen, M. Photocatalytic Removal of Organic Dyes by Titanium Doped Alumina Nanocomposites: Using Multivariate Factorial and Kinetics Models. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1285, 135509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Rasheed, T.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Yan, Y. Peroxidases-Assisted Removal of Environmentally-Related Hazardous Pollutants with Reference to the Reaction Mechanisms of Industrial Dyes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri, R.A.; Safni, S.; Jamarun, N.; Septiani, U.; Kim, M.-K.; Zoh, K.-D. Degradation and Mineralization of Violet-3B Dye Using C-N-Codoped TiO2 Photocatalyst. Environ. Eng. Res. 2019, 25, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, P.S.; Patil, S.B.; Ganganagappa, N.; Reddy, K.R.; Raghu, A.V.; Reddy, Ch.V. Recent Progress in Metal-Doped TiO2, Non-Metal Doped/Codoped TiO2 and TiO2 Nanostructured Hybrids for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 7764–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Xiao, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Meng, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y. TiO2-Based Catalysts with Various Structures for Photocatalytic Application: A Review. Catalysts 2024, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, N.-B.; Nguyen, T.A.; Vu, S.V.; Vo, H.-G.T.; Lo, T.N.H.; Park, I.; Vo, K.Q. Modified Hydrothermal Method for Synthesizing Titanium Dioxide-Decorated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites for the Solar-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34037–34050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Calebe, V.C.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Lei, Y. Interstitial N-Doped TiO2 for Photocatalytic Methylene Blue Degradation under Visible Light Irradiation. Catalysts 2024, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, N.; Lai, C.W.; Johan, M.R.B.; Mousavi, S.M.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Gapsari, F. Progress in Photocatalytic Degradation of Industrial Organic Dye by Utilising the Silver Doped Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposite. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, A.; Ikram, M.; Ali, S.; Niaz, F.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Using Semiconductor Photocatalysts to Clean Industrial Water Pollution. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 97, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.-Z.; Cao, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Li, S.-H.; Zhang, S.-N.; Deng, S.; Li, Q.-S.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Lai, Y.-K. Synthesis, Modification, and Photo/Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation Applications of TiO2 Nanotube Arrays: A Review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liang, X.; Liu, Y. Co-CNT/TiO2 Composites Effectively Improved the Photocatalytic Degradation of Malachite Green. Ionics 2024, 30, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, V.B.; Ke, S.-C.; Dodamani, A.G.; Deshmukh, S.P.; Kim, J.-S. Boron-Doped TiO2-CNT Nanocomposites with Improved Photocatalytic Efficiency toward Photodegradation of Toluene Gas and Photo-Inactivation of Escherichia Coli. Catalysts 2020, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.H.; Chen, W.J. Synthesis and Characterization of TiO2/CNT Nanocomposites for Azo Dye Degradation. Mater. Sci. Forum 2017, 909, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir, O.; Ait-Karra, A.; Idouhli, R.; Khadiri, M.; Dikici, B.; Aityoub, A.; Abouelfida, A.; Outzourhit, A. A Review on TiO2 Nanotubes: Synthesis Strategies, Modifications, and Applications. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2023, 27, 2289–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkhali, N.; Prasad, C.; Malkappa, K.; Choi, H.Y.; Govinda, V.; Bahadur, I.; Abumousa, R.A. Recent Update on Photocatalytic Degradation of Pollutants in Waste Water Using TiO2-Based Heterostructured Materials. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, R.; Córdoba, G.; Padilla, J.; Lara, V.H. Influence of Manganese Ions on the Anatase–Rutile Phase Transition of TiO2 Prepared by the Sol–Gel Process. Mater. Lett. 2002, 54, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue on Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes–TiO2. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 398, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, J.; Luo, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3 Over Mn–Ti Oxide Catalyst: Effect of the Synthesis Conditions. Catal. Lett. 2021, 151, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Youn, S.; Kim, D.H. Characteristics of Manganese Supported on Hydrous Titanium Oxide Catalysts for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with Ammonia. Top. Catal. 2016, 59, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mueller, D.N.; Crumlin, E.J. Recommended Strategies for Quantifying Oxygen Vacancies with X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 116709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Kauch, B.; Szperlich, P. Determination of Energy Band Gap of Nanocrystalline SbSI Using Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2009, 80, 046107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, B.A.; Mohamed, W.A.A.; Galal, H.R.; Abd El-Bary, H.M.; Ahmed, M.A.M. Photocatalytic Study of Some Synthesized MWCNTs/TiO2 Nanocomposites Used in the Treatment of Industrial Hazard Materials. Egypt. J. Pet. 2019, 28, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. P25-Graphene Composite as a High Performance Photocatalyst. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houas, A. Photocatalytic Degradation Pathway of Methylene Blue in Water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2001, 31, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, J.C.; Yu, J.-G.; Kwok, Y.-C.; Che, Y.-K.; Zhao, J.-C.; Ding, L.; Ge, W.-K.; Wong, P.-K. Enhancement of Photocatalytic Activity of Mesoporous TiO2 by Using Carbon Nanotubes. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2005, 289, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ramezani Motlagh, H.; Jaafarzadeh, N.; Mostoufi, A.; Saeedi, R.; Barzegar, G.; Jorfi, S. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline and Real Pharmaceutical Wastewater Using MWCNT/TiO2 Nano-Composite. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 186, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ramezani Motlagh, H.; Jaafarzadeh, N.; Mostoufi, A.; Saeedi, R.; Barzegar, G.; Jorfi, S. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline and Real Pharmaceutical Wastewater Using MWCNT/TiO2 Nano-Composite. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 186, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).