Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Trajectorial Turn in Semantic Theory

2. From Traces to Trajectories: Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Trace Logic: The Hoffman-Prakash Framework

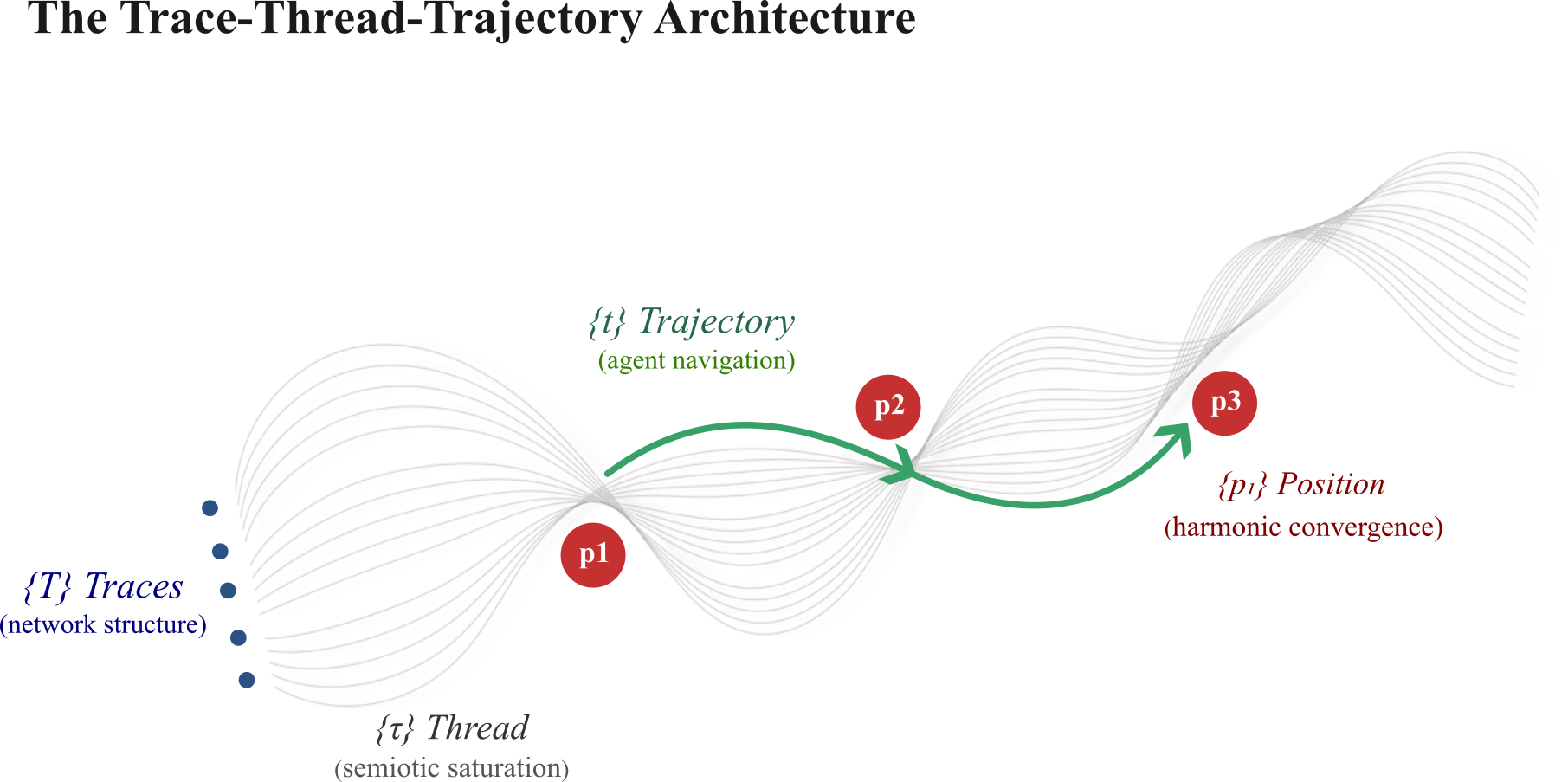

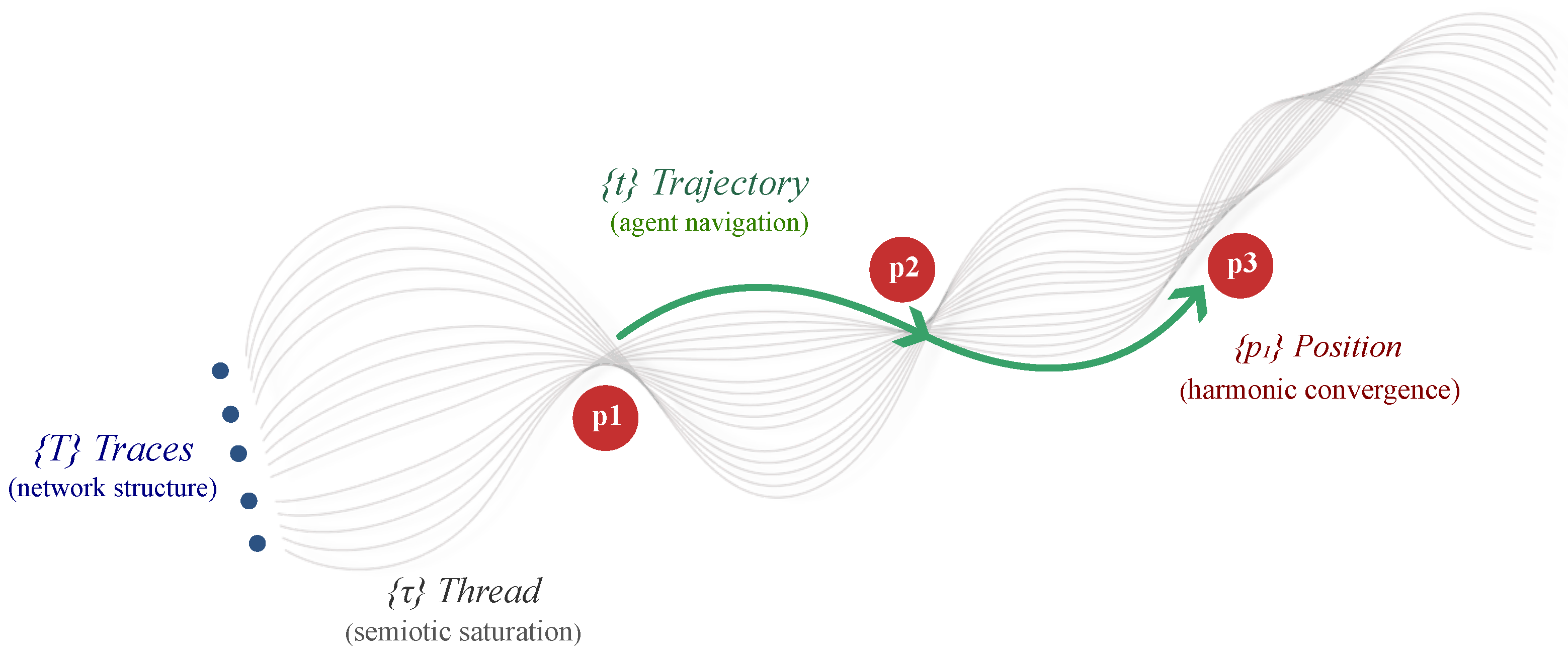

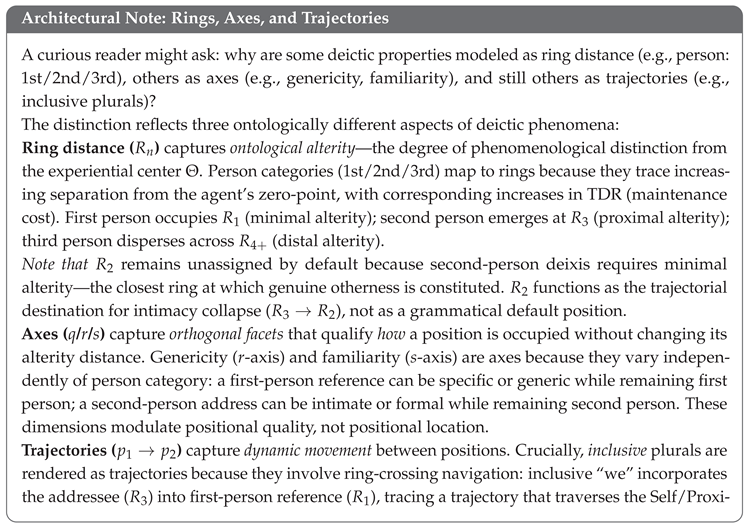

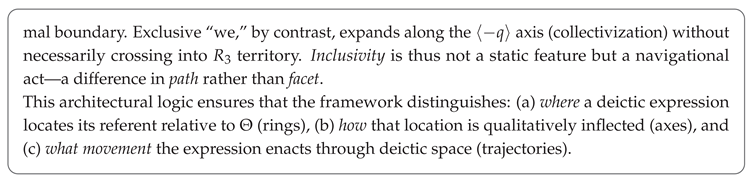

2.2. The Substrate: Trace → Thread → Trajectory

2.2.1. Trace

- Exist in the Network Environment of Traces (NET)—the substrate reality theorized by Conscious Agents Theory (Hoffman et al. 2024)

- Pre-phenomenal: exist before conscious observation renders them into experience

- Provide navigational affordances without determining specific trajectories

- Stabilize through repeated traversal (saturation)

2.2.2. Thread

- : Phenomenal thread bundle (rich experiential detail)

- : Archetypal thread bundle (abstract theoretical patterns)

2.2.3. Trajectory

- for individual trajectory (the analytical unit)

- for movement notation (from position 1 to position 2)

- for blocked transitions (IIP barriers)

- Have onset phase, informational “sweet spot,” and dissipation phase

- Follow asymptotic functions (approach targets without discrete endpoints)

- Length varies: extended trajectories versus compressed trajectories

- Measured by informational distance, not temporal duration

2.2.4. Position : Harmonic Coherence Points

- for position (coherence point within )

- Coordinate system where

- Exist within thread bundles, not independently

- Have Temporal Dissipation Rate (TDR)—maintenance cost

- Distance from zero-point () indicates informational investment

- Connected via possible movements (some facilitated, some blocked by Information Interchange Protocols)

2.2.5. The Architectural Relationship

2.3. The Trajectorial Extension: From Static Traces to Dynamic Navigation

2.3.1. Fractal Autosimilarity and Scalar Relativity

2.4. Attractor Basins and Semantic Stability

3. T&T Operative Principles

Overview

Foundational Architecture

-

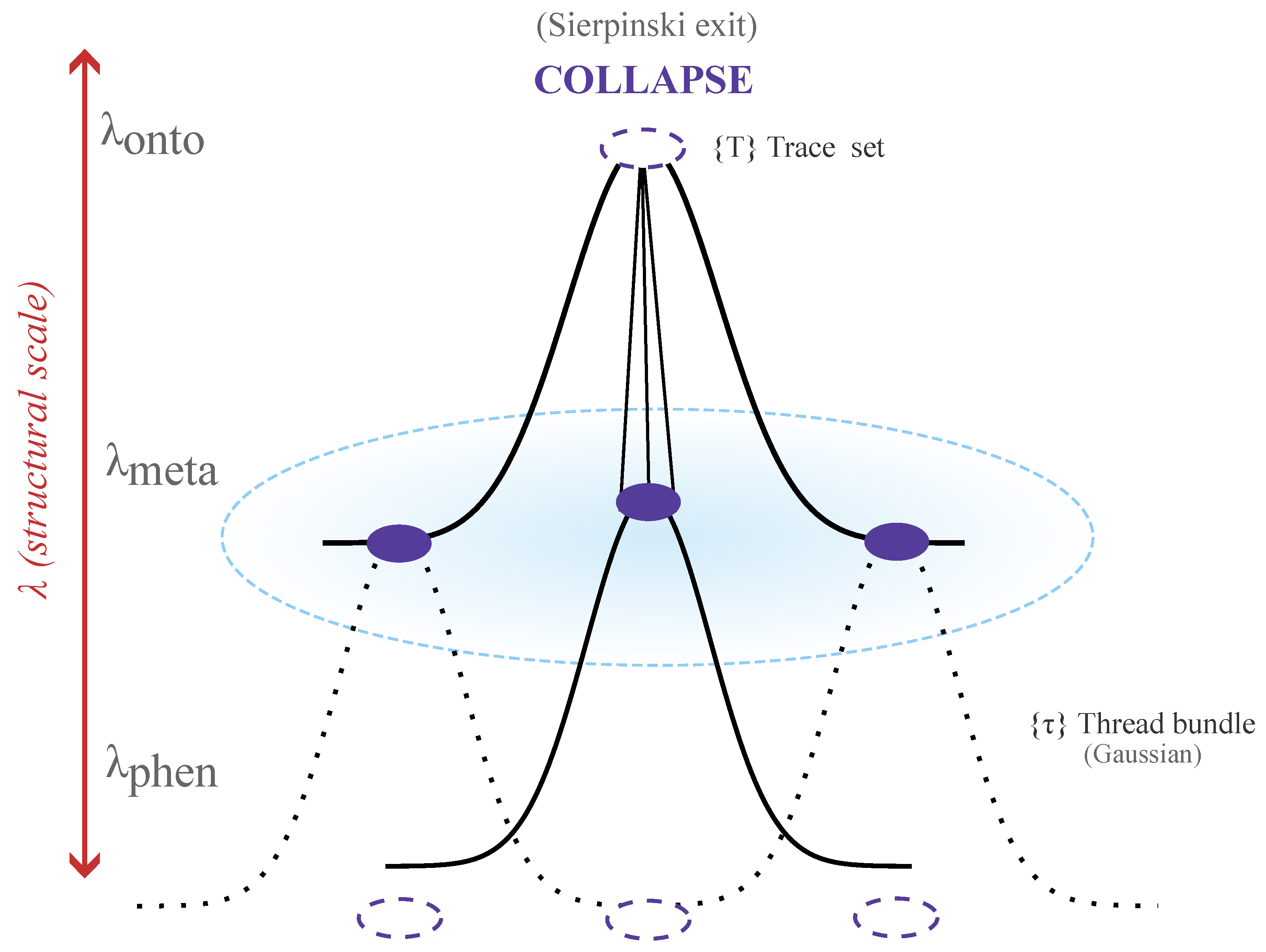

“Four levels structure informational dynamics: with ”Notation convention: = trace sets (pre-representational substrate in NET); = thread bundles (stabilized trace convergences); = trajectories (conscious navigation, analytical units); = positions (coherence points within ). Traces generate threads through repeated traversal; threads structure trajectories; positions emerge as harmonic convergence nodes within threads.

-

“A trajectory is a conscious agent (CA) activity; Meaning is trajectorial”Trajectories require conscious observation to manifest. Without CA activity, only trace patterns exist. Semantic content is not stored but enacted through navigational dynamics.

-

“NET is the base system, CA is a function”The Network Environment of Traces (NET) constitutes fundamental reality. Conscious agents emerge as functional operators within this substrate, not as ontological primitives.

Informational Architecture

- 4.

-

“Direction and attention are indexical CCI principles”Deixis occurs only within Contextual Convergence Interfaces (CCIs). Outside these interfaces, neither pointing nor attention have semantic anchor.

- 5.

-

“CCI is contiguous with Present Moment Experience”CCIs are not abstract but phenomenologically immediate—they constitute the experiential field where trajectories unfold in real-time navigation.

- 6.

-

“Trace is ontological, a non-representational memory at NET”Traces are not mental representations but informational imprints in the substrate itself. They exist prior to and independent of conscious access from the perspective of the AC cognitive delimitation—it’s persona.

Dynamics and Convergence

- 7.

-

“Thread bundles are stabilized trace convergences; trajectories navigate through them”When multiple agents repeatedly traverse similar informational terrain, individual traces stabilize into thread bundles . Threads are not trajectories but the structured pathways that trajectories navigate through. Phenomenologically, threads are what we move along as meaning and experience, including the subset we call “linguistic meaning”. Thread saturation (how established a pathway is) and trajectory compression (how much informational distance is covered) are orthogonal—a highly saturated thread can support both extended and compressed trajectories.

- 8.

-

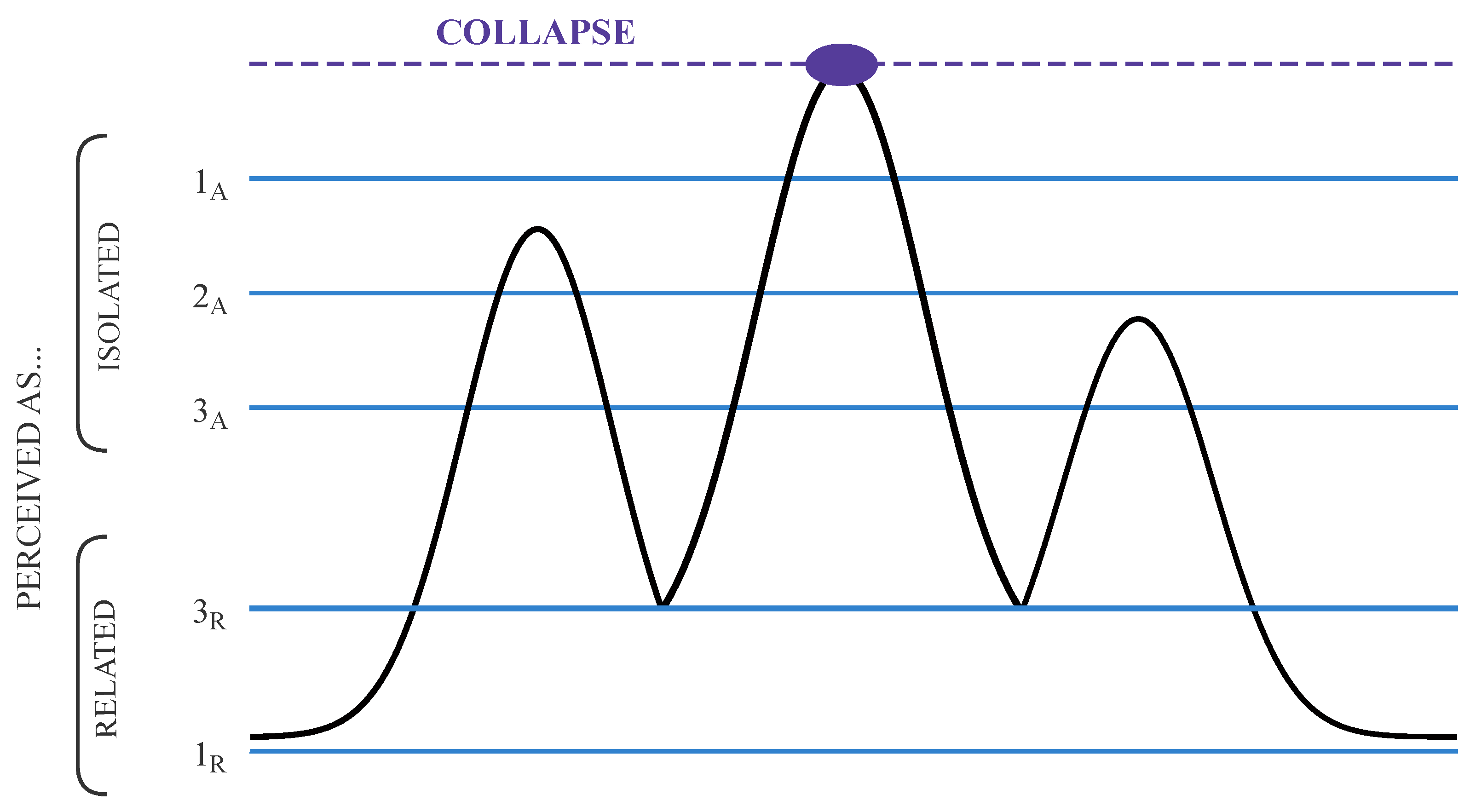

“Positions are harmonic coherence points within thread bundles ”A position is not a categorical box but a point of high informational coherence within a thread bundle—like multiple vibrating strings crossing at a point where their vibrations align. Positions exist only within threads; they have Temporal Dissipation Rate (TDR) as maintenance cost; their distance from indicates informational investment. Movement between positions () constitutes trajectory; blocked transitions () indicate IIP barriers.

- 9.

-

“Trajectories are fundamentally networking, but a subset maintains apparent CA individuation”Most trajectorial activity is transpersonal networking. The trajectories that maintain agent boundaries are a special subset requiring continuous energetic investment.

- 10.

-

“Shared Reality is a function of transductor properties of SSP manifested in CCI”Semiotic Stabilization Patterns (SSPs)—like language, books, films—transduce individual trajectories into collective convergence when manifested through CCIs.

- 11.

-

“Common Knowledge is basic trajectorial networking; what we `know’ combines NET, access (IIP), and awareness ()”Knowledge is not possession but participatory access—a function of substrate availability (NET), interchange protocols (IIP), and tuning resolution (commonly at pasive ).

Operational Distinctions

- 12.

-

“ configures the board; active builds on it; CA navigates either way”Lambda () sets structural granularity—the scale at which the informational table is configured (, , ). Sigma () actively constructs perceptual patterns and modulates epistemic access. Conscious agents navigate regardless of whether is actively modulated or habitually fixed. Critical: and are orthogonal dimensions— determines structural scale while modulates access mode within that scale.

- 13.

-

“No creativity without -movement; everything else is trajectory recurrence”Innovation requires shifting epistemic perspective ( or ). Without such movement, agents merely repeat established trajectorial patterns.

Language & Intersubjectivity in CCIs

- 14.

-

“CCI is co-extensive with present experience; spatiotemporal deixis marks convergence salience”A Contextual Convergence Interface (CCI) does not represent external reality but constitutes the phenomenological field of “present experience.” Spatiotemporal coordinates (here, now, I, you) are not labels for pre-existing entities but salience markers stabilizing the convergence field—they function as IIPs (Information Interchange Protocols) that constrain attention and reduce informational entropy within the interface.

- 15.

-

“Language is trajectorial dynamics pre-stabilized via SSPs; it assumes objective worlds as pre-packed CCIs”Linguistic meaning-making operates primarily through Stabilized Semiotic Patterns (SSPs)—collectively grooved trajectorial sequences with low Temporal Dissipation Rate (TDR). This stabilization creates the phenomenological illusion of an “objective world” (entities in space, events in time, causal relations) by packaging architecture into readily navigable form. Language does not describe a pre-given world; it provides highly efficient CCI templates that allow rapid convergence without requiring agents to negotiate basic ontological commitments at each interaction. The “world” is thus a pre-packed CCI—a collectively maintained informational structure that functions as default convergence substrate for linguistic exchanges.

- 16.

-

“Language transduces stochastic infinity of egocentric into shared navigational space”Each conscious agent operates from an egocentric (experiential zero-point) defining their unique projection. Language functions as the primary transducer enabling convergence: it maps the stochastic multiplicity {, , ..., onto a shared navigational substrate (CCI) where agents can coordinate trajectories despite originating from distinct -centers. This is not telepathy but structural coordination—agents navigate isomorphic SSPs from different starting positions, producing experiential “sharedness” as emergent alignment effect.

- 17.

-

“Language is a mechanism that stabilizes trans- regions, enabling trajectories to traverse granularities”Ordinary trajectories navigate within a configured -granularity: the thread bundle maintaining phenomenal hexid coherence operates predominantly within . However, certain semiotic mechanisms—preeminently language (understood broadly: verbal, gestural and social communication)—stabilize regions between granularities, enabling trajectories that traverse from the phenomenological () toward the meta-conceptual ().This trans- bridging capacity is not accidental but functional. Language transforms interface objects into classes: nouns do not designate entities but stabilize categorical regions that exist at coarser granularity than phenomenal particulars. What appears in immediate experience as this dog (phenomenal, ) becomes navigable as dog (categorical, ) through linguistic stabilization.Typological variation: Languages differ in their characteristic -positioning. English has abundant trajectories predominantly at , with extensive nominal abstraction and systematic tense marking that presupposes temporal objectification. Languages like Tzotzil (Haviland 1994) or Navajo (Smith et al. 2007) show, in contrast, trajectories closer to , with evidential systems, aspect-prominence, and classificatory verbs that track phenomenal salience rather than categorical membership. This is a different navigational calibration—distinct trans- stabilization patterns shaped by cultural-ecological trajectorial histories.Metaphor as trans- trajectory: What cognitive linguistics describes as “conceptual metaphor” (Lakoff Johnson 1980) are precisely these trans- trajectories: stabilized routes enabling navigation of abstract domains () by parasitizing the thermodynamic economy of embodied domains (). The coupling is structural (-traversal), though the mode of access () determines whether navigation is automatic or deliberate. Crucially, metaphoric saliency correlates with the informational density gradient between scales: the steeper the differential between phenomenologically rich and informationally compressed , the more it will strike the curious linguistic eye as a metaphor par excellence.

- 18.

-

“Language stabilizes or destabilizes shared reality; high TDR regions threaten convergence protocols”Language plays the most crucial role in maintaining or fracturing “shared reality” within CCIs. Effective linguistic coordination lowers TDR (sustained informational coherence), enabling fine-grained intersubjective navigation. However, when dissipative environments generate high-TDR regions—semantic drift, ambiguity, incommensurable framing—agents may stabilize at coarse hexid-meta positions that override convergence protocols. This manifests as polarization: agents occupy meta-level abstractions () with minimal trace-level anchoring ( blocked), producing apparent “communication” (shared vocabulary) without genuine convergence (incompatible navigational structures). The TDR gradient thus indexes fragility of shared reality.

- 19.

-

“Linguistic reference is an IIP lowering TDR via recursive stabilization”Reference functions as an Information Interchange Protocol (IIP) that constrains informational continuity across utterances, lowering TDR by creating recursive stability. When agents successfully “speak about the world” or “speak to others,” they are not mapping words to objects but coordinating trajectories through SSP-stabilized regions. Each successful referential act reinforces the IIP: “DOG” refers not because it points to entities but because it reliably navigates convergent trajectorial patterns across agents. Breakdown of reference = IIP failure: agents go through incompatible SSPs, trajectories diverge, TDR spikes, convergence dissolves.

- 20.

-

“Indexicality only exists in CCI; it reinforces convergence via attentional focusing”Deixis (I, here, now, that) and ostension (pointing, demonstratives) are not context-dependent reference but CCI-constitutive operations. They have zero existence outside active convergence interfaces; “that” does not point to an object but focuses intersubjective attention on a shared informational region within the CCI, further stabilizing discursive representations by making them “relevant.”

- 21.

-

“Cognitive semantic relations occupy different /phenomenological strata; not all reflect empirical ”What cognitive semantics identifies as “conceptual structure”—image schemas (trajector-landmark), semantic hierarchies (hypernym-hyponym), figure-ground organization, lexical categories (parts of speech)—occupies three distinct architectural strata:

- Hexid-onto (): Basic trajectorial bundles echoing through interfaces as pre-representational invariants. Example: trajector-landmark asymmetry as fundamental force-dynamic template accessible via .

- Hexid-meso (): Representational accumulation at phenomenological granularity—semantic categories, prototype effects, schematic organization. These are saturation effects: collective convergence produces stable attractor regions that function as navigational landmarks (see Figure 4).

- Hexid-meta (): Meta-representations from scientific analysis—metalanguages, theoretical diagrams, formal models. These operate at and may provide excellent structural narratives without necessarily bearing direct relation to empirical base at (finest-grained phenomenological access still within conscious navigation).

The key distinction: hexid-onto relations are trace-level constraints (exist in NET regardless of observation); hexid-meso relations are saturational attractors (emerge from collective trajectorial activity); hexid-meta relations are analytical constructs (of coarse -granularity). Cognitive semantics has often conflated these levels, treating hexid-meta constructs (theoretical schemas) as if they were hexid-onto architecture (archetypal structure).Critical implication for lexical categories: So-called “parts of speech” (noun, verb, adjective, etc.) are not universal cognitive primitives but likely branches of —products of European grammatical traditions (Greek technē grammatikē, Latin ars grammatica) that reify analytical convenience into ontological necessity. These metalinguistic categories operate at hexid-meta () and may provide excellent pedagogical or cross-linguistic comparison tools, but they should not be projected onto as if speakers “think in nouns and verbs.” This is epistemic flattening: universalizing a particular analytical framework (literate, alphabetic, Indo-European-derived) as if it revealed cognitive architecture rather than reflected specific historical-intellectual traditions.

- 22.

-

(Self): First-person deixis (I) centers at the innermost ring, internally structured along q/r/s axes. The interpretation of these axes depends on the active thread bundle , the operative granularity , and the Semiotic Stabilization Patterns (SSPs) instantiated in the hexid heuristic.Before specifying axis content, a notational clarification is necessary. Following the conventions established in Radial Analysis (Escobar L.-Dellamary 2025), each axis possesses bidirectional polarity: and denote movement toward the positive or negative pole of the q-axis, respectively. This creates six angular zones rather than three undifferentiated axes. The polarity nomenclature carries no evaluative implication—“positive” and “negative” are purely geometric, with semantic interpretation assigned contextually based on the phenomenon under analysis. For personal deixis at , one common directional configuration—grounded in cross-linguistic pronoun research (Kitagawa Lehrer 1990,Siewierska 2004)—maps as follows:

- q-axis (Individuation): Individuated self (emphatic singular I, highly differentiated self-reference) ↔ Collectivized self (we as group, self-as-member-of-community). Movement along the q-axis corresponds to the associative expansion characteristic of pronominal plurality: “I” does not multiply into “I + I” but rather combines with non-speaker referents (, ), rendering trajectories inherently heterogeneous.

- r-axis (Genericity): Contextual/specific reference (this speaker, this moment, this utterance) ↔ Generic/impersonal reference (role-based construals like “as researchers, we...”, dedicated impersonal forms like one, man, or repurposed second-person generics). This axis tracks the scope of reference from deictic particularity to universal applicability.

- s-axis (Stance): Personal/intimate (solidarity-marked, informal register, affective proximity) ↔ Formal/institutional (authority-marked, detached, professional distance). This axis captures the social-relational dimension of self-positioning—what the typological literature terms “familiarity” or the vertical/horizontal dimensions of social deixis.

This is not a claim about multiple selves but a recognition that first-person reference navigates distinct facets within self-positioning. The axes reflect trajectorial patterns documented across diverse pronominal systems (Bhat 2004,Siewierska 2004) rather than universal grammatical primitives. - 23.

-

(Proximal, minimal): Second-person deixis (you) occupies the third ring by default—close enough for direct address, distant enough to constitute alterity. However, is minimal positioning; actual intersubjective distance is trajectorized:

- Intimacy trajectory: — In close friendship or romantic contexts, you is navigated inward, collapsing intersubjective distance. Under (descent to pre-reflective immersion), even the – boundary may dissolve momentarily in highly intimate CCI regions.

- Alienation trajectory: — In betrayal, epistemic distrust, or hostile framing, you is navigated outward, increasing affective/epistemic distance. At (Distal), second-person becomes Alienated Alter—grammatically still “you” but experientially remote or adversarial.

- (Distal): Positions occupied by Alienated Alters—not merely “distant” but experientially inaccessible or epistemically opaque. This includes depersonalized institutional agents (“the system,” “the administration”), hostile outgroups, or individuals perceived as fundamentally untrustworthy, in regions of “institutional and impersonal” conflation. Crucially, alienation is not spatial but trajectorial: the path from to passes through convergence protocol failure—whether as blocked IIPs (), unsustainable TDR gradients, or -incommensurability where apparent CCI engagement masks incompatible threads ( locked, blocked, see principles 14-18 starting on page 11).

Convergence Protocol Failure (CPF) could manifest through three mechanisms:- (a)

- IIP-blocked alienation: Direct barrier preventing trajectory completion

- (b)

- TDR-dissipative alienation: High maintenance cost makes convergence unsustainable

- (c)

- -incommensurable alienation: Shared vocabulary without navigational alignment

Core insight: The position (, , ) provides geometric potential, but the trajectory (movement sequence) enacts meaning. Intersubjective proximity is not a fixed property of pronouns but a dynamic function of navigational patterns.Consider a discourse shift from “you could argue...” to “some people claim...”. The first expression positions the addressee at in the zone—a specific, individuated interlocutor whose perspective is being invoked. The second expression enacts a compound trajectory: movement toward (collectivizing the referent from “you” to “people”) and toward (generalizing from contextual addressee to impersonal class). This compound trajectory may additionally involve radial displacement toward if the speaker is simultaneously signaling epistemic distance from the claim. What traditional grammar treats as a simple substitution of lexical items, Radial Analysis (Escobar L.-Dellamary 2025) reveals as multi-dimensional positioning strategy: the speaker depersonalizes the interlocutor, collectivizes the source of the claim, and optionally alienates the position—all through a single phrasal shift.These micro-movements remain invisible to frameworks that treat person as a static morphosyntactic feature. T&T’s trajectorial lens exposes discourse-level positioning strategies operating beneath the threshold of traditional grammatical analysis.

|

|

Interpretive Notes

4. Architecture of Multi-Scale Dynamics: Self-Similar Collapse and Fractal Meaning

4.1. The Autosimilarity Mechanism

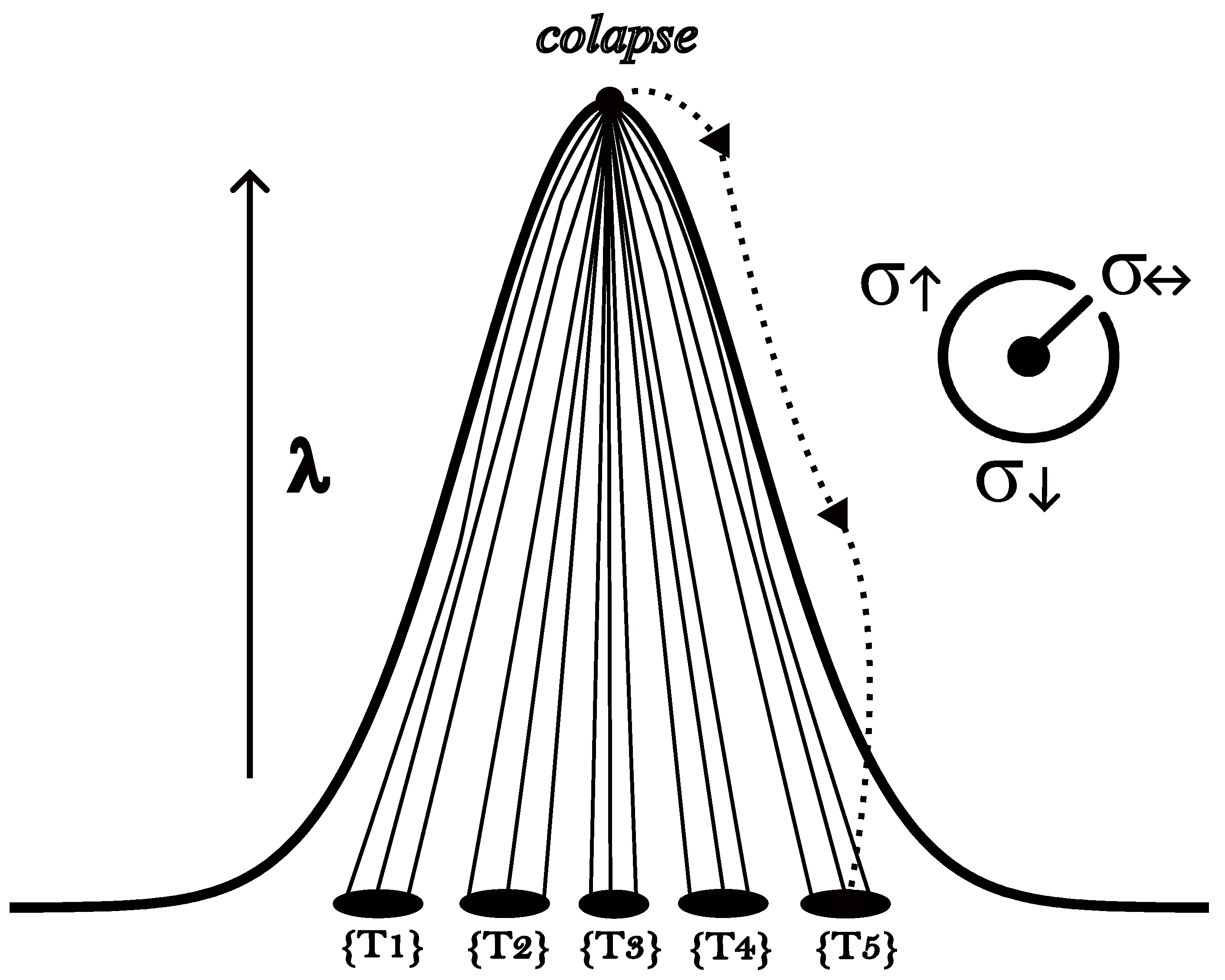

4.1.1. Pyramidal Saturation Structure

4.1.2. Temporal Convergence: Multiple Pyramids Achieving Isomorphism

4.1.3. Two Temporal Regimes of Accumulation

4.1.4. Granular Slicing: The One-and-Many Problem

4.2. Why No Permanent Meta-Representational Traps

5. Empirical Translations: Bridging to Cognitive Research Traditions

5.1. Prototype Effects: Phenomenal Primacy and Categorical Superstrate

5.2. Metaphor as Trans- Trajectory

5.2.1. Conventionalization vs. Deliberate Metaphorizing

- determines what structure the trajectory traverses (phenomenal → meta-conceptual)

- determines how the agent navigates ( deliberate vs. automatic)

- Thread saturation determines efficiency (conventionalized vs. novel)

5.3. Image Schemas as Stable Attractors

5.4. Bridging Cognitive Grammar’s Diagrammatic Heuristics

6. Conclusion: Meaning as Trajectorial Dynamics

References

- Bhat, D. N. S. (2004). Pronouns. Oxford University Press.

- Binder, J. R. (2016). In defense of abstract conceptual representations. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23(4), 1096–1108. [CrossRef]

- Copley, B., & Harley, H. (2015). A force-theoretic framework for event structure. Linguistics and Philosophy, 38(2), 103–158. [CrossRef]

- Cuccio, V., & Caruana, F. (2019). Rethinking the abstract/concrete concepts dichotomy. Physics of Life Reviews, 29, 157–160. [CrossRef]

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. (2025a). CLOUD: Language, identity and meaning as fields of information. Peter Lang.

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. (2025b). Radial Analysis: A T&T Framework for Language and Cognition. Preprints.Org. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. A. (2020). Advances in Embodied Construction Grammar. Constructions and Frames, 12(1), 149–169. [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.

- Gärdenfors, P. (2000). Conceptual spaces: The geometry of thought. MIT Press.

- Gärdenfors, P. (2014). The geometry of meaning: Semantics based on conceptual spaces. MIT Press.

- Grosfoguel, R. (2008). Hacia un pluri-versalismo transmoderno decolonial. Tabula Rasa, 9, 199–216.

- Harnad, S. (1990). The symbol grounding problem. Physica D, 42, 335–346.

- Haviland, J. B. (1994). “Te xa setel xulem” [The buzzards were circling]: Categories of verbal roots in (Zinacantec) Tzotzil. Linguistics, 32(4–5), 691–742. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. (2019). The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hoffman, D. D. (2016). The Interface Theory of Perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3), 157–161. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D., Prakash, C., & Chattopadhyay, S. (2024). Traces of Consciousness (No. 2024101305). Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Hutto, D. D., & Myin, E. (2017). Evolving enactivism: Basic minds meet content. MIT Press.

- Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press.

- Kitagawa, C., & Lehrer, A. (1990). Impersonal uses of personal pronouns. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(5), 739–759. [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Mithun, M. (1999). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge University Press.

- Noë, A. (2004). Action in perception. MIT Press.

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533–580.

- Quilty-Dunn, J., Porot, N., & Mandelbaum, E. (2023). The best game in town: The reemergence of the language-of-thought hypothesis across the cognitive sciences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46, e261. [CrossRef]

- Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 192–233.

- Siewierska, A. (2004). Person. Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, C., Perkins, E., & Fernald, T. (2007). Time in Navajo: Direct and indirect interpretation. International Journal of American Linguistics, 73(1), 40–71. [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G. (2017). Integrated information theory of consciousness: Some ontological considerations. In S. Schneider & M. Velmans (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to consciousness (2nd ed., pp. 621–633). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Van Valin, R. D. (2005). Exploring the Syntax-Semantics Interface. Cambridge University Press.

- Varela, F., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations. Blackwell.

- Yee, E. (2019). Abstraction and concepts: When, how, where, what and why? Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 34(10), 1257–1265. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Intent here should not be understood as prior mental representation or propositional attitude but as the agentic capacity of a conscious agent (Choice Maker, Campbell, 2007) to navigate informational space. While intent operates through directional constraints on informational flow—what Hoffman et al. (2024) formalize as attractor bias within trace dynamics—its ontological status is not reducible to structural mechanism. Intent functions thermodynamically (weighting transition probabilities without requiring a homunculus “deciding”), yet it introduces indeterminacy operators: the agent’s navigational choices are co-determinants of phenomenal rendering, not epiphenomenal outputs of base-level structure. This aligns with but exceeds Spinoza’s conatus (striving toward organized persistence) and Whitehead’s appetition—historical precedents for pre-representational directedness that nonetheless lacked the explicit co-constitutive role between agent and structure. T&T’s critical move is recognizing that structural constraints and agentic intent are intrinsically coupled: neither alone determines the phenomenal render. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).