Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

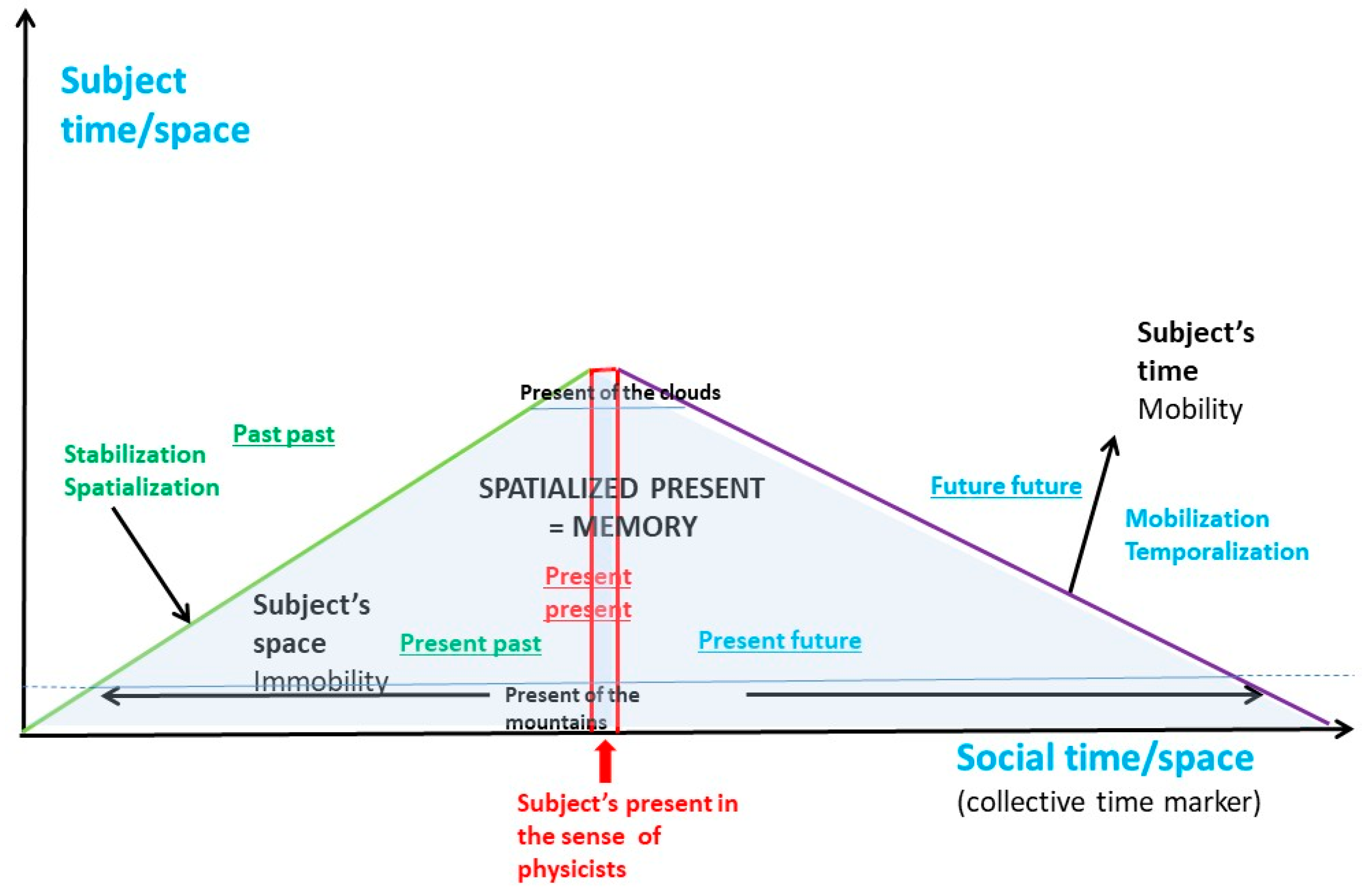

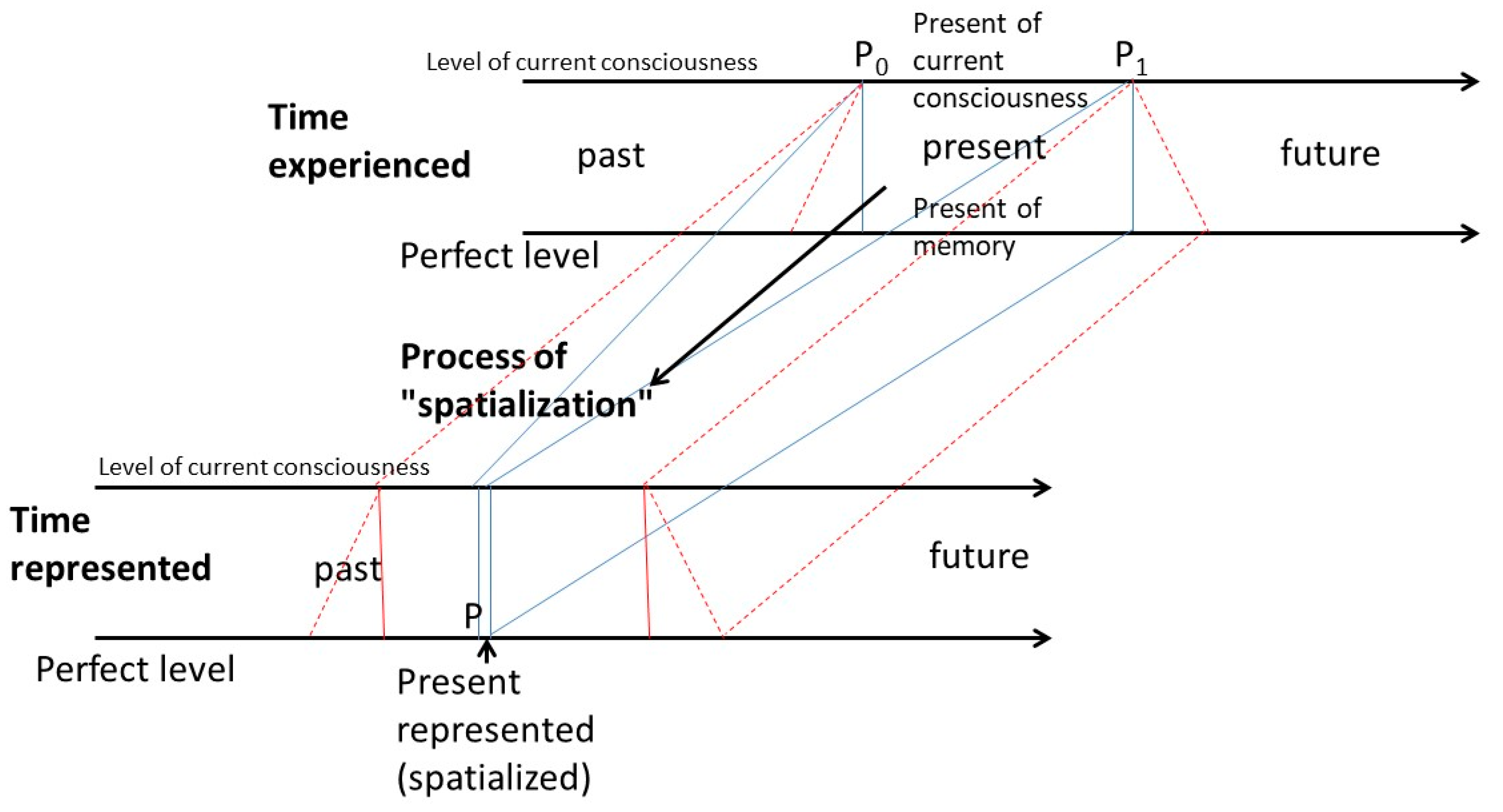

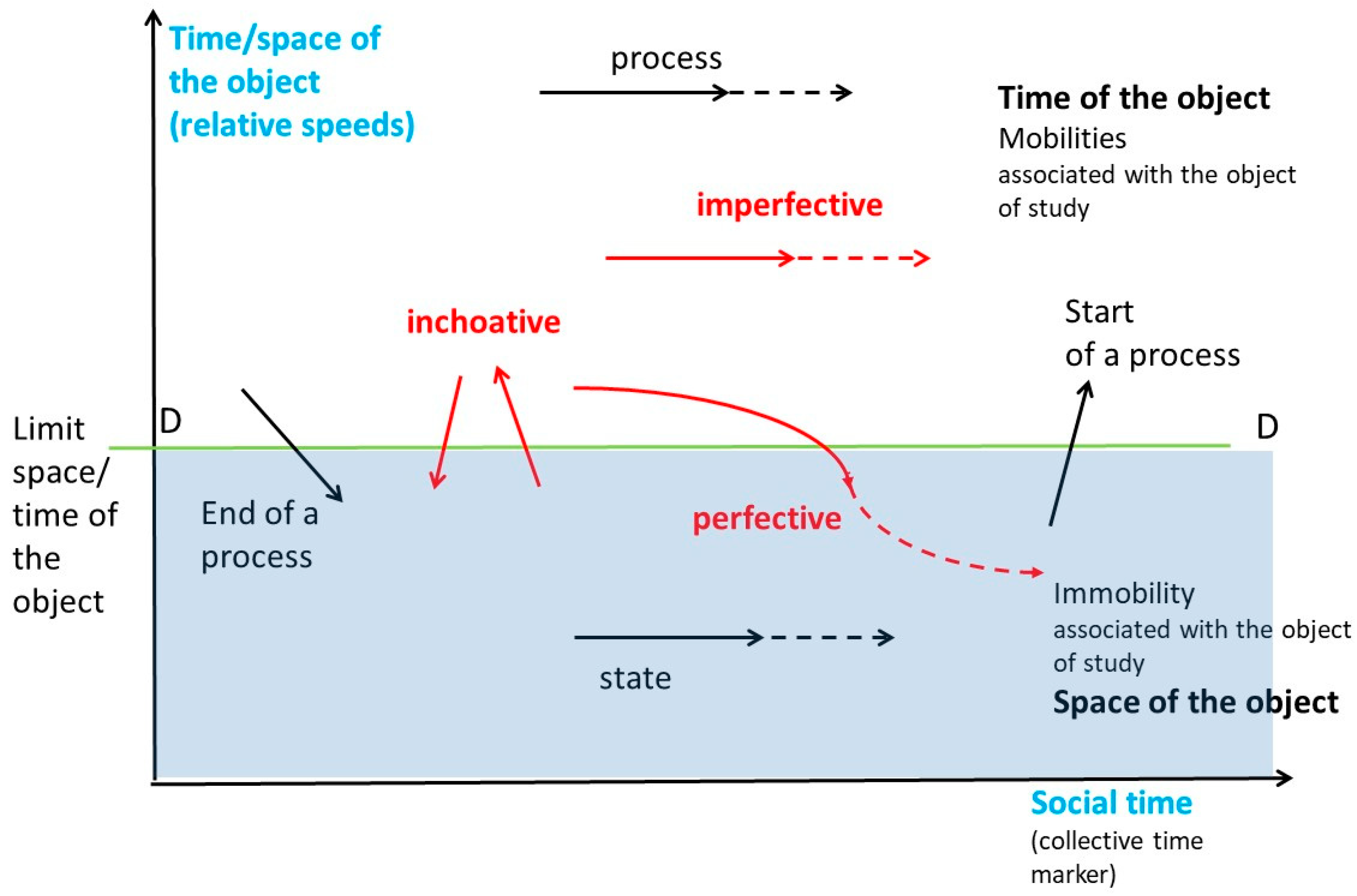

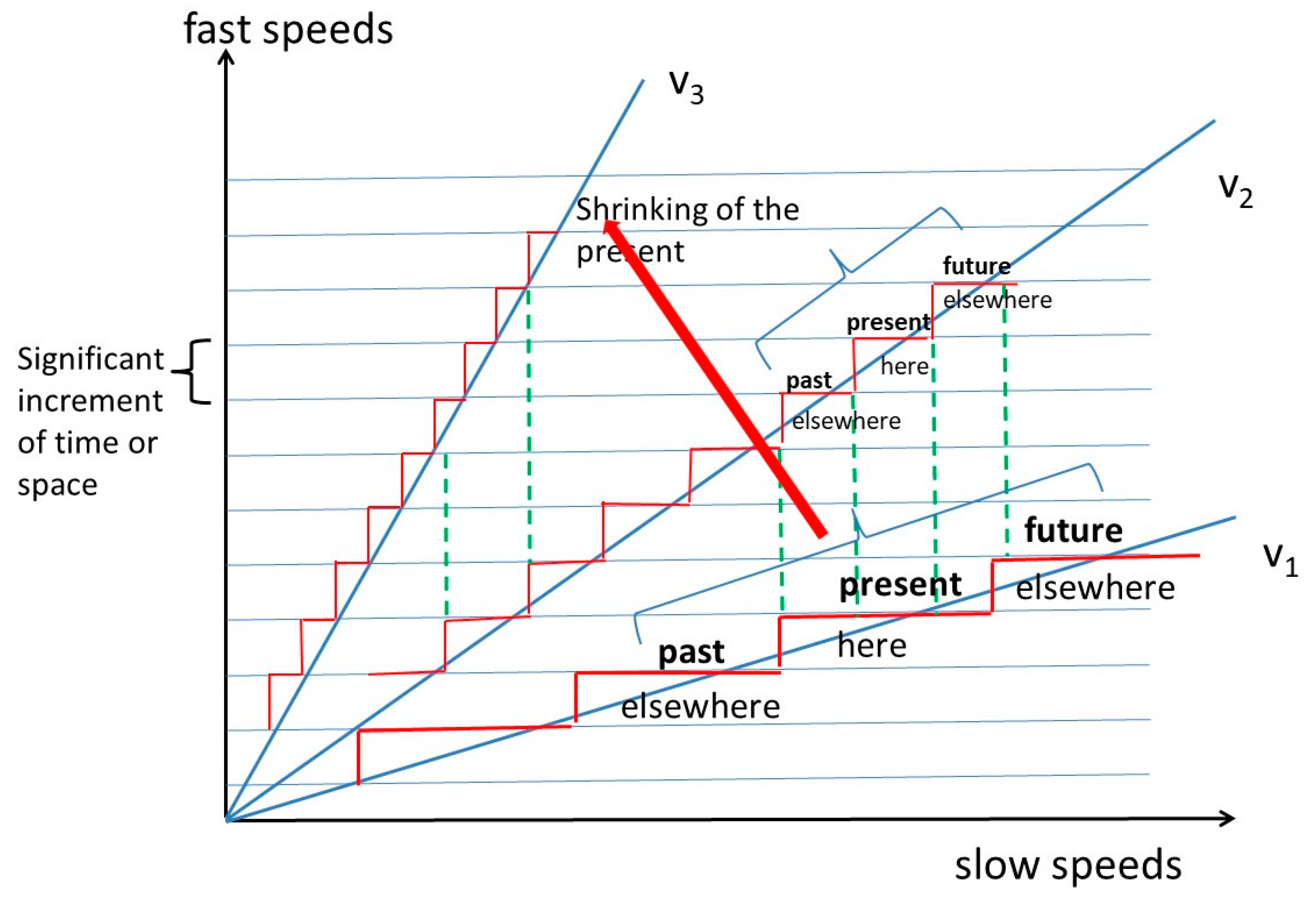

The convergence of words for space and words for time in languages has long been noted. Through the hypothesis of linguistic localism, authors express that space has cognitive primacy, and is used to talk about time. Based on our reflection on the (revisited) foundations of physics, we formulate a different hypothesis. We limit ourselves to an epistemological analysis, without in-depth work on specific linguistic situations. The common root of time and space is movement, which is also the source of language (our approach is based on embodied cognition, as well as on a relational epistemology: words are defined in opposition/composition to each other). In this understanding, there are not, in advance, words attributed to space on one side and, separately, words attributed to time on the other. There are only words of movement; there is a discourse of/in movement within which words, through comparisons between them, construct time and space. Following changes in context (more or less distant from our human scales, but revealing), we can imagine transformations from one to the other. We propose a graphic representation of comparisons between movements. At the heart of our article, it provides a framework for thought, to be compared with those proposed by the linguist G. Guillaume. It allows us to envisage a broad field in which to represent the different times and spaces that encompass the subject. We situate what we might call the past past, the present past, the present present, the present future, and the future future (the present of mountains does not have the same meaning as the present of clouds, nor as the present of mathematical physics, a simple reference point of limited material value). Some characteristics of how languages function in terms of verb aspects and tenses, and noun/verb duality, are briefly discussed in light of the proposed representation. The question of the multiplicity of spatio-temporal "strands" of the discourse, and their interweaving, alternating between visible/explicit and invisible/implicit parts, is discussed. The text proposes preliminary research directions to be tested and compared with other linguistic theories.

Keywords:

Introduction

Everything is time,Immobile time, I call it space.Everything is space,Moving space, I call it time.

1. The Trilogy of Time/Space/Movement (Our Work)

2. The Words of Space and Time

2.1. Epistemological Analysis

2.2. Examination of Some Objections

- -

- When did it happen? Was the sun to the right or left of the church steeple? (for a small community in a specific space). Or for a larger community, a village: was the sun to the right or left of such-and-such peak21 ? Or again: was the store of this brand on your right or left (while walking around town)?

- -

- Answer: on the right

- -

- When did it happen? Was it above or below your camp? (for mountaineers climbing a difficult rock face over several days). Or for cavers descending into a chasm: was it above or below the hall of gours? Or, for passengers on an airplane taking off: was it above or below the cloud layer?

- -

- Answer: above, on.

3. Comparisons of Movements: A Graphical Representation

3.1. Horizontal Axis

3.2. Vertical Axis, First Step

3.3. Interlude: Changes in Speed Scales

3.4. Vertical Axis, Second Step: The Subject's Environment

3.5. G. Guillaume's Representations

3.6. The Light Year: From Geological Time to Astronomical Time

4. Aspects and Tenses of Verbs

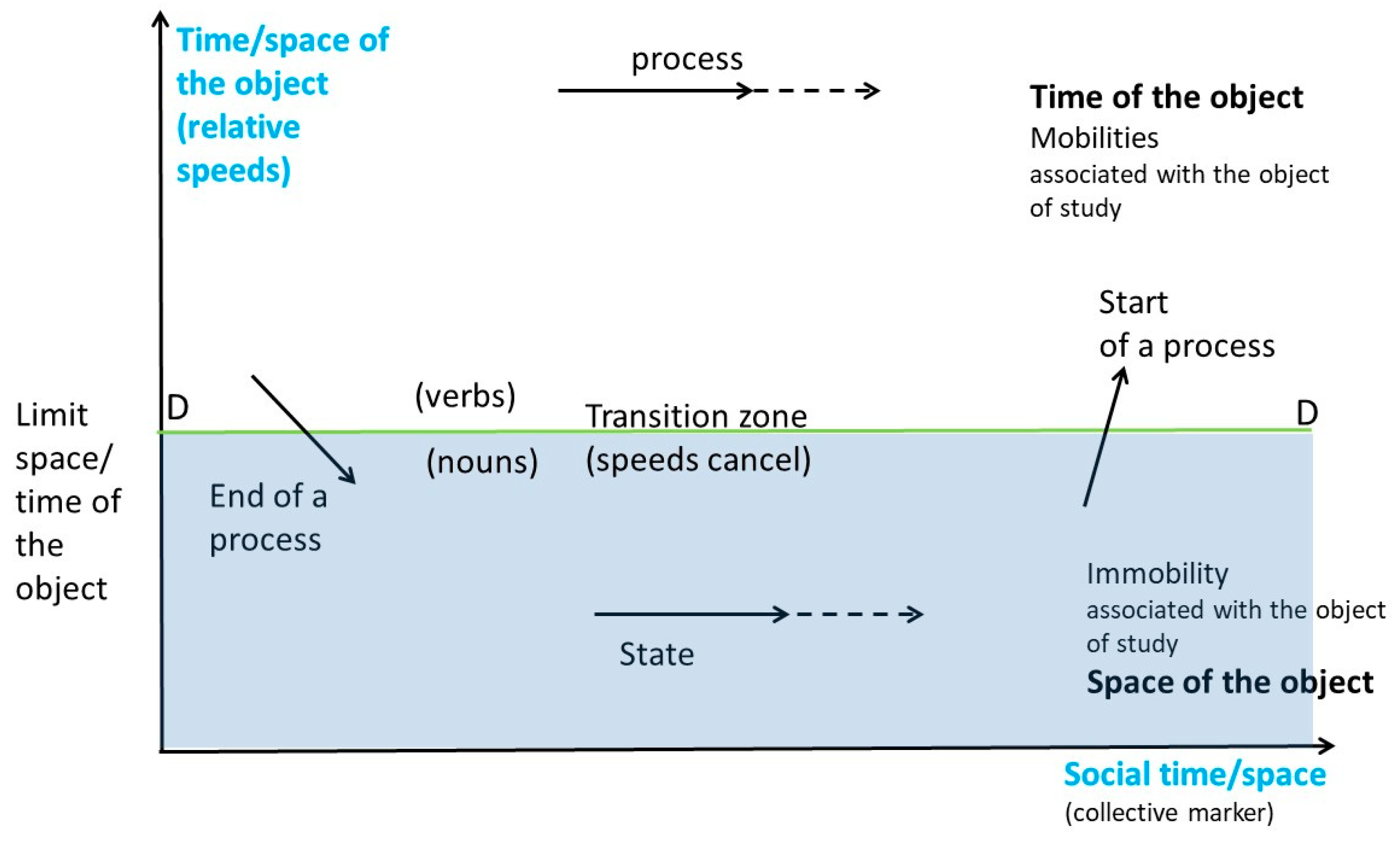

4.1. The Verb/Noun Opposition

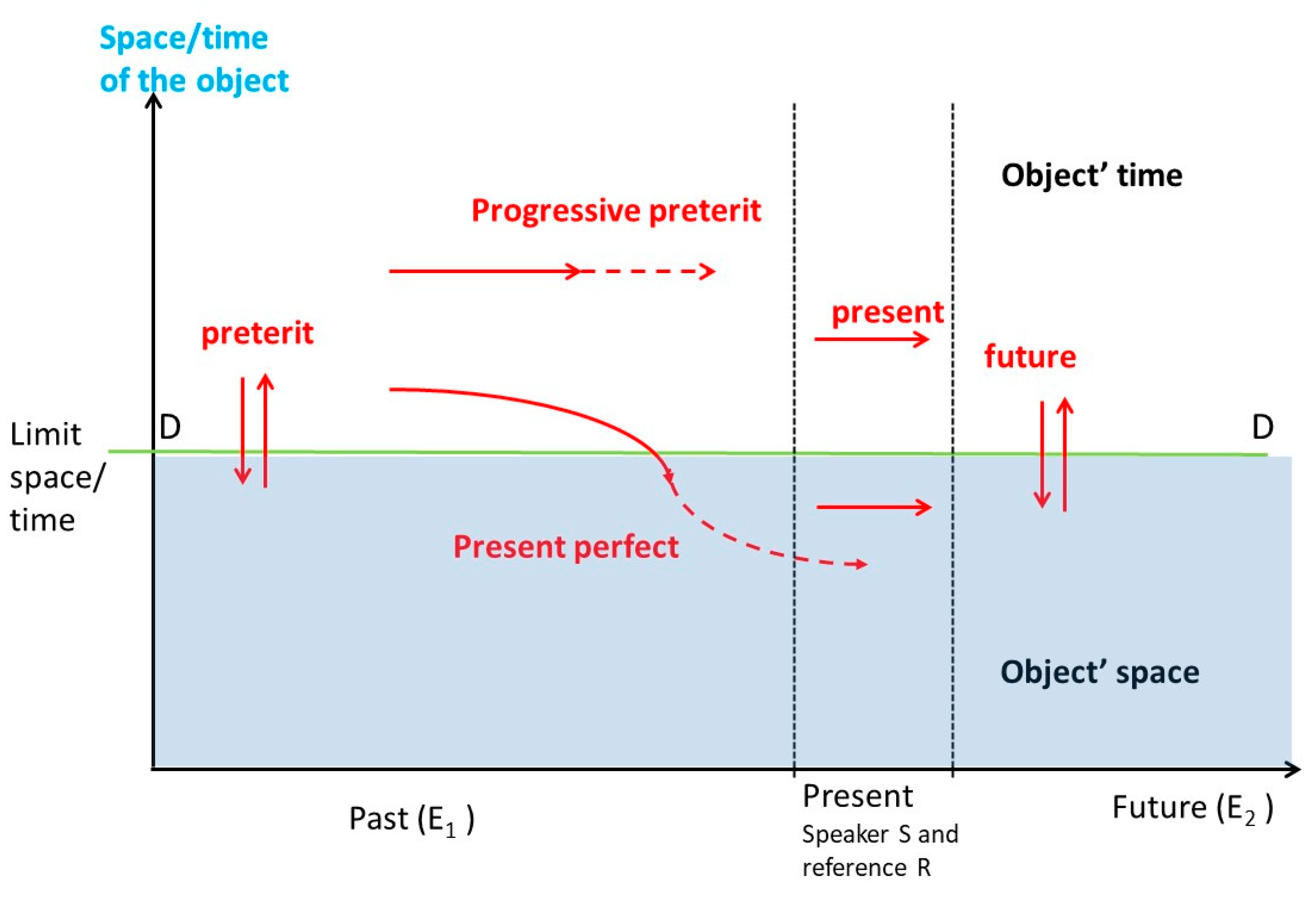

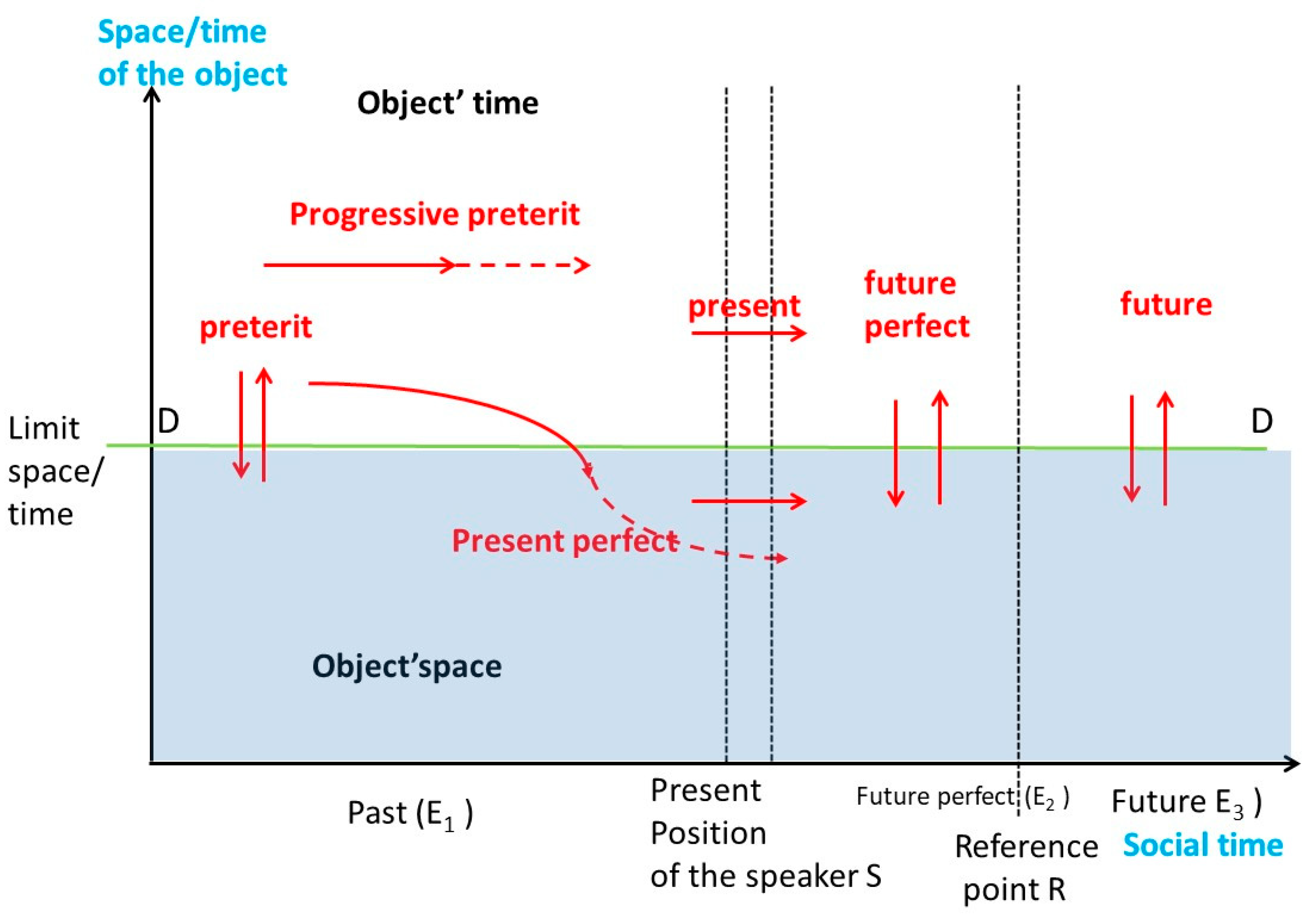

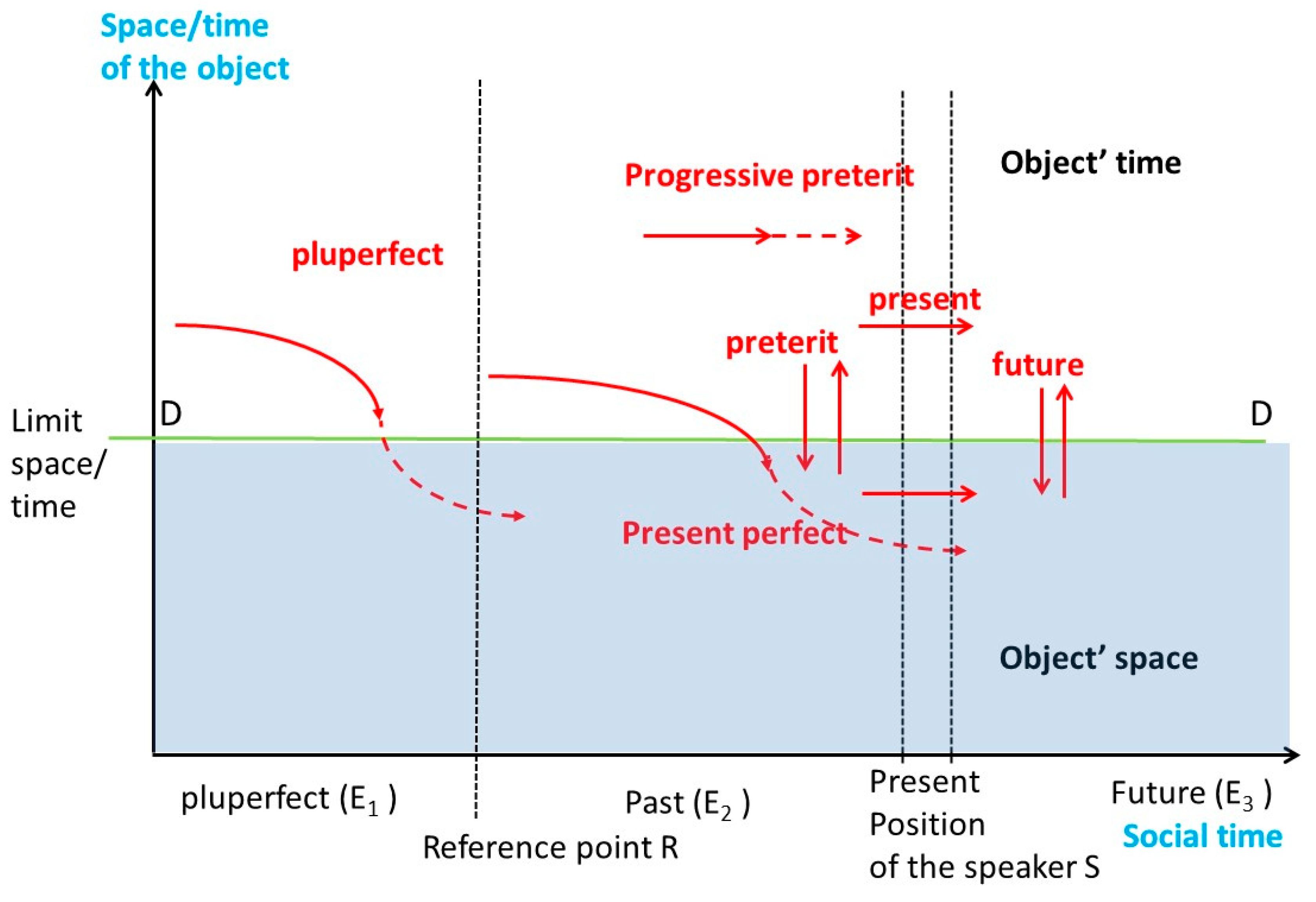

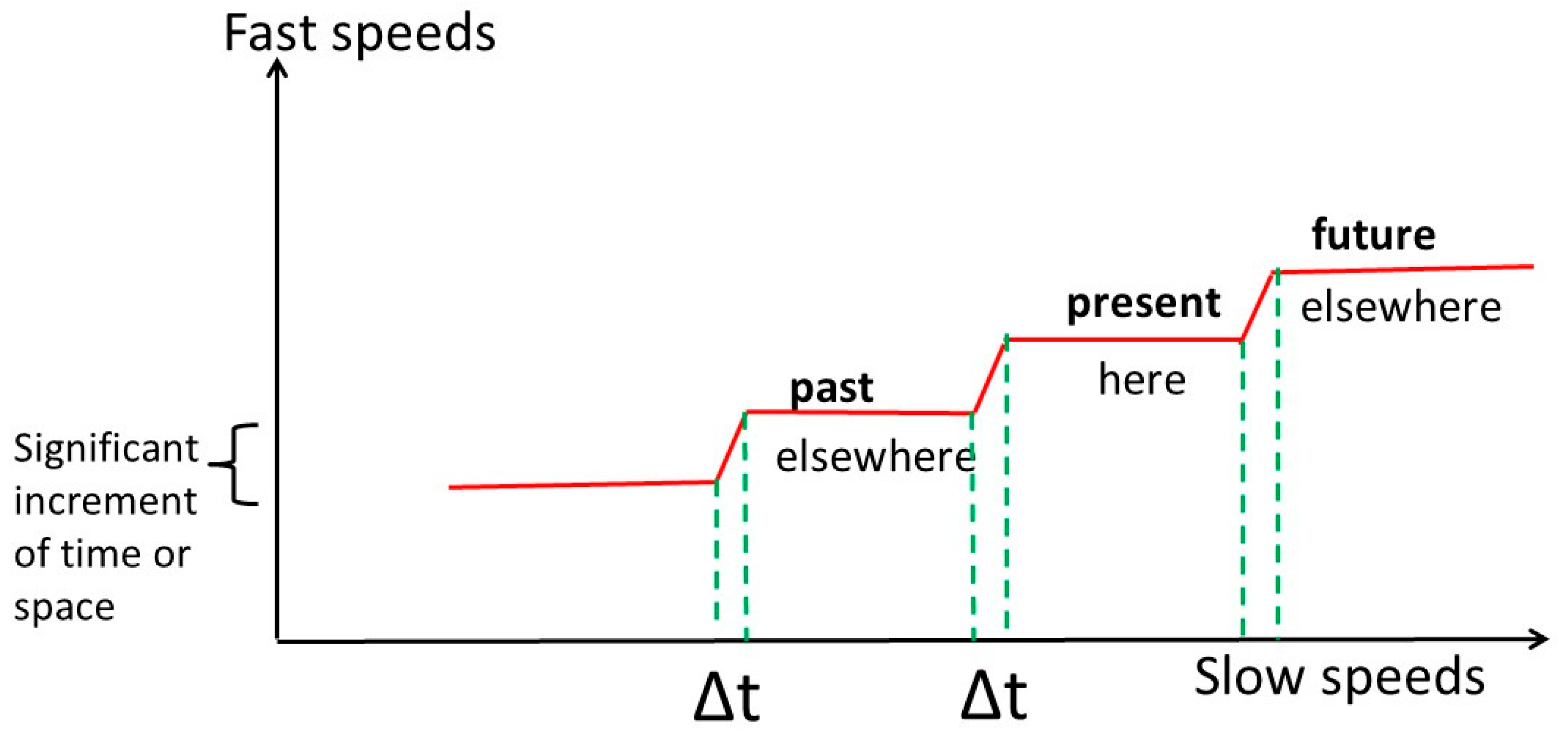

4.2. Verb Aspects (Figure 4)

4.3. Verb Tenses (Figures 5a, b, and c)

4.4. Tenses and Aspects

4.5. Verb Moods

5. Elements for Discussion

5.1. The Thread of Thought/Language Has Several Strands

5.2. The Words and Silences of Language; the Blacks and Whites of Writing

6. Conclusions

Appendix A. Linguistic Localism: Some Comments

Acknowledgments

References

- Asic T. (2004) The cognitive representation of time and space: a pragmatic study of linguistic data in French and other languages. Thesis, L. Lumière Lyon 2 University.

- Asic T. (2008) Space, time, prepositions, Droz, 320 p.

- Asic T. & Stanojevic V. (2013a) The expression of time through space: presentation. Langue française, 179, 3, 3-12.

- Asic T. & Stanojevic V. (2013b) Space, verbal tenses, temporal prepositions, Langue française, 179, 3, 29-48.

- Bakhtin M. (1978) Aesthetics and Theory of the Novel. Gallimard, Paris.

- Bara F., Rivier C. & Gentaz E. (2020) Understanding the beneficial role of the body in learning to read in light of embodied cognition theory, A.N.A.E., 168, 553-563.

- Bergson H. (1938) La pensée et le mouvant, Presses Universitaires de France, 294 p.

- In Space and time in language; Brdar M., Omazic M., Pavicic Takac V., Gradecak-Erdeljic T. & Buljan G. (eds) (2011) Space and time in language, Peter Lang, 372 p.

- Calame-Griaule G. (1970) Towards an ethnolinguistic study of African oral literatures. In: Langages, 5th year, 18, Ethnolinguistics, 22-47.

- Chen S. (2021) A contrastive study of temporal-spatial metaphors in English, French and Chinese. Lecture notes on language and literature, 4, 20-29.

- Chetcuti Y. (2012) The deer, mythical time and space, Thesis, University of Grenoble.

- Dahan-Gaida L. (2020) Visual imagination in scientific invention: schemas, thought images, diagrams. In: Imaginarios tecnoscientificos, volume 1, Juliana Michelli S. Oliveira, Rogerio de Almeida, David Sierra G. (eds), FEUSP, Open Book Portal of the University of São Paulo, pp. 17-36.

- Demagny A.-C. (2013) The expression of time and space in French and English: typological perspectives on language acquisition by adults, Langue française, 179, 3, 109-127.

- Depaule J.-C. (2006) By dint of walking... On descriptive wanderings, In: S. Naïm (ed.) The encounter of time and space, linguistic and anthropological approaches, Peeters, 7-34.

- Fournier J.-M. (2013) History of theories of time in French grammars, ENS Editions, Lyon, 330 p.

- Fusellier-Souza I. & Leix J. (2005) The expression of temporality in French sign language, La nouvelle revue AIS, 31.

- Geld R. & Krevelj S. L. (2011) Centrality of space in the strategic construal of up in English particle verbs, in: Space and time in language, Brdar M. et al. (eds) Peter Lang, 145-166.

- Girel M. (2016) Gestures in the making, European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, 4 p.

- Gradecak-Erdeljic T. (2011) Spatial and temporal relations in the conceptual metaphor EVENTS ARE THINGS, in: Space and time in language, Brdar M. et al. (eds) Peter Lang, 41-54.

- Guillaume G. (1947) Temps et verbe. Théorie des aspects, des modes et des temps. L’architectonique du temps dans les langues classiques. Paris: H. Champion, reprinted 1984.

- Guy B. (2015) Urban ruptures, a spatio-temporal pragmatics, Parcours anthropologiques, 10, 46-64.

- Guy B. (2016a) From the space and time of nature to the space and time of man (on the relationship between geography and prehistory), .

- Guy B. (2016b) Dance, space, time, .

- Guy B. (2019) SPACE = TIME. Dialogue on the system of the world. Penta, Paris,.

- Guy B. (2020) Are there relativistic effects (in the sense of the relativity theory) in the perception of time? Elements for interpreting the experiments of Caruso et al. (2013), .

- Guy B. and Brachet T. (2023) Visit the karst of psychoanalysis, dive into the unconscious, Penta Editions, Paris.

- Guy B. (2024) Refreshing the theory of relativity, Intentio, no. 5, special issue, Relativity, 9-55.

- Guy L. (2001) Psychomotor therapy for adolescents in a medical-educational institute. Setting the body in motion, a privileged tool for working on identity. Thesis, Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University, 115 p.

- Haspelmath M. (1997) From Space to Time. Temporal Adverbials in the World's Languages. Munich/Newcastle: Lincom Europa.

- Ingold T. (2025) The Past to Come, Seuil, Paris.

- Jackendorff R. (1985) Semantics and cognition, The MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass.).

- Jacob A. (2016) Time and Language. Essay on the Structures of the Speaking Subject, Penta Editions, Paris, Pentathèque, 472 p.

- Laplane D. (2001) Thought Without Language, Studies, 394, 3, 345-357.

- Leblic I. (2006) The Kanak chronotope. Kinship, space, and time in New Caledonia. In: Naïm S. (ed.), The encounter of time and space, linguistic and anthropological approaches, Peeters, 63-80.

- Le Draoulec A. & Borillo A. (2013) When here is now, Langue française, 179, 3, 69-87.

- Le Draoulec, A. & Stosic D. (2019) Space and time: what asymmetries? Scolia, linguistics journal, University of Strasbourg, 33, 192 p.

- Leenhardt M. (1947) Do Kamo, la personne et le mythe dans le monde mélanésien, 1976, Gallimard, Paris, 314 p.

- Leger P. (2022) On the origins of embodied cognition. Phenomenology and cognitive sciences. In: Embodied cognition, a research program between psychology and philosophy, Editions Mimesis, 75-90.

- Lobo C. (2021) Locus communis. From the crisis in science to the analytics of technical evidence. Towards a broader and deeper critique of logical reason. Academia Vivarium Nostrum, Frascati, Rome, In defesa dell’uomo, 25 p.

- Manga Qespi A. E. (1994) Pacha: an Andean concept of space and time, Revista Espanola de Antropologia Americana, 24, 155-189, Edit. Complutense, Madrid.

- Marcolongo A. (2018) La langue géniale, 9 bonnes raisons d’aimer le grec, Les Belles Lettres.

- Mondala L. (2014) Corps en interaction. Participation, spatialité, mobilité, ENS Editions, Lyon, 400 p.

- Naïm S. (ed.) (2006), The Encounter of Time and Space, Linguistic and Anthropological Approaches, Peeters, 268 p.

- Orlov P. (2019) The limits of comparison between spatial and temporal parts. Elements for reflection. In: Le Draoulec, A. & Stosic D. Space and time: what asymmetries? Scolia, linguistics journal, University of Strasbourg, 33, 43-60.

- Pavelin Lesic B. (2011) The metaphorization of space in speech and gesture, in: Space and time in language, Brdar M. et al. (eds) Peter Lang, 183-200.

- Poincaré H. (1902) Science and Hypothesis, Flammarion, Paris.

- Poincaré H. (1905) The value of science, Flammarion, Champs sciences 2011, 190 p.

- Radden G. (2011) Spatial time in the West and the East. In: Space and time in language, Brdar M. et al. (eds), Peter Lang, 1-40.

- Reichenbach H. (1947) Elements of symbolic logic, The Macmillan Co., New York.

- Raymond P., Hallier J.E. (1982) The Resistible Fate of History, Albin Michel, 162 p.

- Rinehart R.E., Kidd J. & Garcia Quiroga A. (2018) Southern hemisphere ethnographies of space, place and time, Peter Lang, 396 p.

- Rochat P. (2015) Global engagement of the body and early knowledge, Enfance, 4, 453-462.

- Rossi C. (2010) The expression of movement and its acquisition in French and English: from early forms to early constructions, thesis, Université Lumière Lyon 2.

- Rossi C. (2013) The expression of manner of movement and its acquisition in French and English. Faits de langues, sémantique des relations spatiales 2, (42) 191-208 .

- Sadoulet P. (2010) Opposites in semiotics, analyses of a novel of discernment: Le journal d'une femme de chambre by Octave Mirbeau, in: Ateliers sur la contradiction, B. Guy (ed.), Presses des Mines, 145-154.

- Stanford J.L. (2011) The spatial relations of color: linguistic categorization of LIGHT-DARK and NEAR-FAR. in: Space and time in language, Brdar M. et al. (eds) Peter Lang, 69-78.

- Stajonevic V. (2024) Reichenbach revisited in the context of formal semantics: formal treatment of tense and aspect in French, Publication Univ. Belgrade, Faculty of Philology.

- Stanojevic V. & Asic T. (2010) The imperfective aspect in French and Serbian in: Interpreting verb tenses, Bern: Peter Lang, 107-127.

- Stosic D., Stanojevic V. & Sotra T. (2012) The expression of space and time in French: comparative perspectives, Filoloski pregled, 9-18, .

- Teissier B. (2006) Geometry and cognition: the example of the continuum, 22 p.

- Vaudène D. (2019) A path towards the question of writing, Intentio, 1.

- Virole B. (2014) Sign language for the deaf. Iconic language and ideogrammatic systems at the heart of semiotics, Proceedings of the 3rd workshops on contradiction, B. Guy (ed.) Presses des Mines, Paris, 163-170.

- Wallon H. (1959) Importance of movement in the psychological development of the child. Childhood, 3-4.

- Weinberg A. (2010) Do we think in words or images? Sciences humaines.

| 1 | These references provide access to a wealth of literature. |

| 2 |

Words of space and time, we understand this in the broadest sense: words and their possible variations, phrases, collections of words, expressions, sentences, various ways of marking space and time: prepositions, nouns, verbs and their conjugations, adverbs, etc. |

| 3 | Our approach is general, and we provide these words by way of illustration. |

| 4 | We take this hypothesis in a basic way. It is a gateway to presenting our understanding of the relationship between time and space. Appendix A contains some comments on the subject. |

| 5 | We reproduce and modify a few excerpts from it here, in an expanded text. Our text was written in French, primarily concerning the French language. In this English translation, we find ourselves in a hybrid position where both languages are involved, although the issues addressed are dealt with in different ways. Explanations of the translation will be provided where useful. |

| 6 | We remain at the threshold of a vast field. This text reflects only a few months of reflection accompanying its writing: we must bring it to a provisional conclusion, while the data that informs it continues to grow, along with the desire to discuss them. |

| 7 | What is important is relative movement, whether it is attributed primarily to the observer or to the landscape that comes toward him. Linguists (cf. Guillaume, 1947) have distinguished between two registers for time itself: ascending (from the past to the future, I am moving towards the future), and descending (from the future to the past, the future is coming towards me) depending on whether or not the observer is the hand of the clock, i.e., whether it relates to his own movement (moving-ego) or to that of the objects he sees passing by (moving-time) (cf. Sadoulet, 2010). |

| 8 | For us, change is resolved into movements, however microscopic they may be. |

| 9 | From mountains to photons, including the pieces of a table being assembled! There is no need for extreme speeds (neither in terms of light nor geological relief). The cessation of movement in what is called space (as opposed to time) as associated with a given object is subject to convention: see below what we have called "spatio-temporal pragmatics." |

| 10 | This discomfort is implicitly acknowledged by Haspelmath (op. cit.; S. Naïm, pers. comm., 2016), who emphasizes both the independence, and the relationship, between space and time: "space and time are the two important basic conceptual domains of human thinking. Neither space nor time are part of a more basic conceptual domain, and neither can be reduced to the other. But space and time seem to show a peculiar relatedness that is perhaps not evident to a naïve philosophical observer." See also Asic and Stanojevic (2013a). |

| 11 | This is particularly true when it comes to understanding the sequence of numbers by "moving" along the line of real numbers in our minds. |

| 12 | In terms of communication, it is also said that nonverbal communication (gestures, facial expressions) dominates verbal communication by 80%, given that words account for only 7% of the latter, with the rest residing in intonation, tone of voice, silences, etc. Words are only the tip of the iceberg of movements in the broadest sense... |

| 13 | We can distinguish between exchange between time and space through a change of context, and transformation from one into the other through continuous variation of context. |

| 14 | Movements in the environment are the primary source of attention to that environment, as studies on the gaze of animals, small children, etc. attest. |

| 15 | Material "particles" in the broad sense, which serve as a support for spatial and temporal relationships, have, through their respective "weights" in a particular context, more spatial than temporal meanings. Thus, the Eiffel Tower is both an object and a place, while a simple flower does not have as much spatial value (where am I? near a rose?). |

| 16 | Leblic (2006) documents the links between space, time, and kinship in New Caledonia. Chetcuti (2012) shows how a particular animal (a deer) "engenders" time and space. See also Calame Griaule (1970). |

| 17 | But the relationship between these speeds is not necessarily secondary to the speeds themselves: we are faced with the same epistemological subtlety, see Guy (2024): we call the relationship between two terms (we separate them into two) what was initially only the result of a single measurement. |

| 18 | For Leblic (2006), this unique reference point for a society is related to the relief of its place of residence, the mountain range of New Caledonia. |

| 19 | Pierre Sadoulet (2010): "in order to represent space, the semiotic subject does not seem to be able to do without temporal succession." Is this the reciprocal of linguistic localism? See also Depaule (2006). |

| 20 | See also the summary in section 6. |

| 21 | The zenith of the sun's course at noon is a position: it divides two times, morning and afternoon. |

| 22 | Leblic (op. cit.) tells us about Melanesian communities where time is also marked by the top and bottom of the Caledonian central mountain range. Chen (2021) tells us about a vertical metaphor of time in China, where the upward direction refers to the past and the downward direction to the future. The image of water falling from top to bottom is a justification for this. |

| 23 | So much so that we could have referred in the title of the article to the convergence of the words time, space, and movement, highlighting, with this expanded title, a circularity (movement is defined by movement) specific to relational epistemology. |

| 24 | G. Guillaume (op. cit.) speaks of "schemes in which complex movements of thought lend themselves better to graphic representation than to verbal description." We are talking here about a representation with two axes; we could consider three (as Guillaume discusses), or even more... |

| 25 | This possibility is not available to the inhabitants of the planet described in the novel The Three-Body Problem.

|

| 26 | This is a way of expressing the second postulate of the theory of relativity. |

| 27 | The horizontal time axis therefore also has spatial value: events can be ordered in space using prepositions, which are essentially equivalent to classification by verb tenses. |

| 28 | The "temporal" part above the DD' limit (see below) is not empty space, but the speeds associated with movements there are not negligible, and we do not construct space there in the sense separate from time.

|

| 29 | |

| 30 | The scope of this section is as much anthropological as it is linguistic. It takes advantage of the possibilities of our graphic representation. In his book Le passé à venir (such as translated into French), anthropologist Tim Ingold (2025) challenges the representation of the succession of generations as a stack of watertight strata. For us, this point of view is a way of revisiting, as we do here, the relationships between time, space, and movement. |

| 31 | Ph. Coueignoux (pers. comm. 2025) proposes an image to capture the variation in speeds and the stacking of scales along the vertical axis: the temporal quality upwards becomes spatial downwards, with speeds decreasing. One can think of a train journey where the passenger sees objects passing by at a very high angular velocity (this is the temporal part); in contrast, objects located further and further away eventually come to a standstill and appear fixed, with an angular velocity tending towards zero (spatial part). |

| 32 | This operative time could be compared to the instant in A. Jacob (2016), or duration in H. Bergson (1938). In our works, we have contrasted lived time ("primary," associated with movement) with time represented spatially, from the moment it is separated from space! T. Brachet (pers. comm. 2025) points us to another work by G. Guillaume: La mécanique intuitionnelle, in which the author addresses the relationship between time and space. We leave its examination to future research, as well as the re-examination of the works of Kant, Humboldt, Hegel, Schelling, Heidegger, Kojève, etc., in addition to Jacob, cited by T. Brachet, which would support our thesis. |

| 33 | Inflected languages express this duality in their own way: noun cases refer to spatial relationships, while verb conjugations refer to temporal or aspectual relationships. |

| 34 | There is then an augment that marks a past reference point. But in other moods, the aorist has no augment. The perfect tense in ancient Greek also expresses an aspect (the passé composé, in French). |

| 35 | An "anti- or a-perfective" (we do not say imperfective), such as the effect of an atomic bomb on a Japanese city (which it is better not to have to describe too often)? |

| 36 | We are not discussing the wide variety of possible tenses, including in French, nor specifically the duality of simple and compound tenses (in French, there is a past perfect tense and even a double compound past tense: "nous l'avons eu fait" [we had it done]). |

| 37 | At this stage, we are not sure we have understood this point. |

| 38 | Our senses function thanks to biological cells; our measuring devices function thanks to sensors. Information is acquired in a discrete manner: the cell or sensor must reach a state of saturation, triggering a switch: the information is then sent to a "central" memory and the cell or sensor, once emptied, is ready for another acquisition. During unloading, there is a gap in recording (this type of behavior is exemplified by the functioning of visual cells). The size of the different pieces seen/forgotten depends on the physical characteristics of the cells or sensors. The quantum of acquisition is a way of seeing a piece of the present as it is experienced (before it dies in the past: we tell ourselves that something has changed and that it is no longer the present). |

| 39 | These authors challenge the generality of localism, based on an analysis of how verbs work. |

| Names | niche, range, zone, region, interval, amplitude, start, departure, origin, beginning, end, arrival, continuation, figure, rhythm, on the spot (for at the moment), with the benefit of hindsight, where (relative pronoun: the moment when, the place where), progress, priority, anteriority, posteriority, odyssey, journey... |

| Verbs | go, come, leave, arrive, return, exit, enter, go up, go down, pass, come back, flee, sail, fly, jump, walk, run, dive, take place, be located, be found, precede, follow, coincide, progress, advance, retreat, regress, finish, begin, accomplish... |

| Prepositions | under, above, below, on, in front of, opposite, behind, to the left of, to the right of, since, as soon as, in, between, towards, around, in the vicinity of, across, near, far from, close to, at the moment of, during, after, before, behind, in front of, from, to, first... |

| Adverbs | previously, then, here, there, now, presently, yesterday, once, formerly, previously, today, immediately, tomorrow, soon, after, later, finally, never, rarely, occasionally, often, always, for a long time, already, simultaneously, elsewhere, everywhere, in front, behind, above, below, outside, near, inside, before, around... |

| Adjectives | greater than, less than, high, low, long, short, narrow, tight (in the sense of narrow), narrowed, limited, unlimited, finite, infinite, large, small, endless, (a duration) measured to the millimeter... |

|

Expressions (compound: nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) |

The revolution is underway; to fall into poverty; a difficult moment, a difficult passage; to be on the brink of disaster; distant memories; the future is ahead of us, the past behind us; to see far ahead; the moment, the time has come for...; pressed for time; the passing, the course, the passage of time; it's two hours from here; when the sun is up; sunrise, sunset; in the blink of an eye; it took us three minutes to see it; chasing time, catching up with time, turning back time; postponing, putting off until later; wandering in one's thoughts; crossing the threshold... |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).