1. Introduction—Language as Ontological Resonance

The nature of language has long captivated philosophers and linguists alike. Aristotle, in De Interpretatione (350 BC), described language as “sound with meaning,” a formulation that foregrounded the acoustic and symbolic dimensions of speech. Centuries later, Noam Chomsky inverted this view, proposing language as “meaning with sound” (Chomsky, 2013)—a cognitive system where internal semantic structures are externalized through phonological form. While both perspectives offer valuable insights, neither fully captures the dynamic, recursive, and ontologically active nature of language. A sound or symbol does not merely carry meaning—it radiates outward, influencing a web of interconnected nodes: individual cognition, cultural norms, historical memory, and social structures. Language is not a passive mirror of thought; it is a generative force that shapes perception, interaction, and reality itself.

Despite this expansive potential, linguistic inquiry has historically focused on foundational domains such as phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexical semantics. It was not until the 20th century that deeper explorations into structural semantics, discourse analysis, and cognitive modeling began to emerge. The study of sentence meaning, in particular, remains one of the most intricate and multifaceted areas in linguistics. Each word in a sentence carries a semantic load shaped by context, cultural nuance, and syntactic positioning. Moreover, meaning is not confined to lexical content—it is constructed through grammatical relationships, narrative framing, and pragmatic inference (Jackendoff, 2002; Langacker, 1987).

Recent advances in cognitive linguistics have emphasized the embodied and experiential grounding of meaning. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) demonstrated that abstract concepts are structured by metaphorical mappings rooted in bodily experience. Talmy (2000) introduced force dynamics to model how language encodes interaction and energy. Langacker’s cognitive grammar reframed syntax as symbolic structure, asserting that grammatical constructions are meaningful pairings of form and conceptual content. These developments have enriched our understanding of how language reflects thought—but they often treat reality as a backdrop rather than a structurally expressive domain.

Semiotic theory, particularly the triadic model of Charles Sanders Peirce (1931–1958), offers a complementary lens. Peirce posited that meaning arises through recursive interpretation among the representamen (sign), object (referent), and interpretant (understanding). This framework highlights the relational and interpretive nature of signs, but it does not fully account for the structural equivalence between language, thought, and reality. More recent work in semiotics and cognitive science—such as Zlatev’s (2005) theory of bodily mimesis and Fauconnier & Turner’s (2002) conceptual blending—suggests that meaning is enacted across modalities, not confined to symbolic systems alone.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Speaks, 2024) identifies two core questions that any theory of meaning must address:

Most theories of meaning attempt to answer these questions by treating language as a reflection of mental states. When language is used to describe the world, it is often seen as mirroring the mind’s interpretation of reality. However, this perspective is limited. It overlooks the fact that language does not merely reflect cognition—it actively constructs and transforms reality through symbolic invocation.

To develop a universally applicable theory of language, we must consider not only mental representation but also the structural logic of reality and the symbolic architecture of language. Humans possess a remarkable ability to generate speech through a complex system of symbols governed by grammatical rules. Children acquire language naturally, often without formal instruction, suggesting the presence of innate mechanisms or universal cognitive scaffolds (Tomasello, 2003; Pinker, 1996). This raises profound questions about the essence of language: Is it a biological instinct, a cultural artifact, or an ontological system that encodes existence?

Language is indispensable to human life. It shapes communication, perception, memory, and social interaction. In a world increasingly defined by multilingualism and intercultural exchange, understanding the fundamental principles of language is not merely academic—it is essential for education, diplomacy, and technological innovation. Second-language acquisition, in particular, benefits from models that emphasize semantic clarity and cognitive resonance over rote memorization (VanPatten, 2015; Doughty & Long, 2003).

Comparative linguistic studies reveal that, despite surface variation, all languages share deep structural similarities. The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) and cross-linguistic typologies suggest that languages encode similar semantic roles—agents, actions, objects, modifiers—even if they differ in syntax or morphology. Randy Harris (1993) notes that the basic knowledge of a language is shared among its speakers, and that individuals can acquire multiple languages with relative ease. This points to a universal substrate of language—one that transcends grammar and reflects a deeper semantic architecture.

This manuscript introduces the Law of the Trio, a triadic principle that models language, thought, and reality as structurally equivalent modalities of existence. It proposes that meaning arises from the recursive coupling of an entity with its state or behavior, encoded across symbolic, cognitive, and physical domains. This framework reframes the sentence not as a syntactic unit, but as a semantic particle—a symbolic cell that mirrors the architecture of being.

The Law of the Trio formalizes this insight through a core semantic function:

Here, Modality refers to language, thought, or reality—each capable of expressing the same semantic event under different symbolic pressures. This function applies universally, allowing for semantic invariance across languages, cultures, and cognitive systems.

The implications of this model are far-reaching. It offers a unified framework for analyzing:

Communication skills: modeling how meaning is encoded, transmitted, and interpreted across modalities

Universality of language: explaining cross-linguistic consistency through semantic recursion

Complex syntactic structures: reframing grammar as recursive semantic geometry

Language acquisition: supporting event-based learning and modifier mapping in L1 and L2 contexts

Ultimately, the Law of the Trio positions linguistics as a structural ontology—a discipline capable not only of describing language, but of modeling the recursive architecture of existence itself. It invites renewed dialogue across disciplines, from philosophy and cognitive science to education and artificial intelligence, offering a lens through which language may be newly seen as a form of being.

2. The Law of the Trio: Unity of Thought, Language, and Reality

The Law of the Trio posits that thought, language, and reality are structurally and semantically equivalent modalities of existence. Though they differ in form, each encodes the same fundamental architecture: an entity, its state or behavior, and the recursive relationships that bind them. This triadic equivalence mirrors phase-change systems in nature, where a single substance may manifest in multiple forms depending on environmental conditions.

Consider water, which exists as solid, liquid, or gas depending on temperature and pressure. Despite these differences in form, its molecular identity remains constant. Similarly, language, thought, and reality represent distinct modalities of the same semantic substance. Each can transform into the other through symbolic, cognitive, or perceptual processes—akin to boiling, condensation, or sublimation. This analogy finds resonance in conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), which demonstrates how physical experience structures abstract cognition. The Trio extends this principle by modeling semantic phase transitions across modalities.

A parallel can be drawn from telecommunications, where voice signals traverse multiple formats—analog, digital, electromagnetic, and optical pulses—before returning to analog form for human perception. This transformation ensures fidelity across transmission systems. Likewise, meaning traverses modalities: a real-world event becomes a mental simulation, which is then encoded linguistically. This recursive flow echoes Fauconnier and Turner’s (2002) theory of conceptual blending, where mental spaces integrate structure and experience to produce emergent meaning.

In the Trio framework, each modality functions as a semantic lens:

Reality: the perceptual or physical instantiation of an entity and its behavior

Thought: the cognitive simulation or conceptual modeling of that event

Language: the symbolic encoding of the event through structured syntax

These modalities are not hierarchically ordered but

structurally homologous. Each can generate, reflect, or transform the others. This triadic recursion is formalized through the semantic function:

Eq.1: The Universal Model of Language, Thought, or Reality

Here, Modality refers to any of the three domains. The function models how meaning arises from the pairing of an entity with its state or behavior, recursively enriched by modifiers. This structure aligns with Langacker’s (1987) cognitive grammar, which treats grammatical constructions as symbolic pairings of form and meaning. The Trio extends this by proposing that such pairings are ontologically recursive—not merely symbolic, but structurally expressive of existence.

The state of an entity describes its attributes, conditions, or appearance. Changes in state—whether internal (e.g., emotion, intention) or external (e.g., movement, transformation)—are referred to as behaviors. These behaviors are not merely actions but semantic transitions, encoding shifts in identity, relation, or presence. This mirrors Talmy’s (2000) force dynamics, which model how language represents interaction and energy across conceptual domains.

In linguistic expression, sentences depict entities, their states, and the behaviors that modify those states. For example:

“The tired child slowly opened the heavy door.” This sentence encodes:

Each modifier recursively enriches the semantic particle, adding perceptual, temporal, and relational depth. This structure parallels Fillmore’s (1982) frame semantics, where meaning arises from relational roles and experiential domains. The Trio deepens this by modeling modifier hierarchy through EMji/VMji notation, enabling formal tracking of semantic recursion.

Thought, in this framework, is not a passive reflection of reality but a cognitive simulation—a mental enactment of entity-state-behavior couplings. This aligns with Barsalou’s (1999) theory of perceptual symbol systems, which posits that cognition is grounded in sensory-motor experience and structured through simulation. The Trio treats thought as a modality of semantic invocation, structurally equivalent to linguistic and perceptual expression.

Reality, likewise, is not an inert backdrop but a structurally expressive domain. Entities and behaviors manifest physically, but their semantic architecture remains consistent with thought and language. This echoes Zlatev’s (2005) work on bodily mimesis, which argues that meaning arises from embodied intersubjectivity and structural alignment across modalities.

The mutual influence among thought, language, and reality is central to the Trio model. Each modality can generate, reshape, or reinforce the others. A spoken word can alter cognition, which in turn can transform behavior and reshape reality. Consider the example of a child whose mother tells him he will become the seventh king of his country. This linguistic act—though symbolic—may induce a cognitive shift, prompting the child to internalize royal qualities. Over time, this mindset may manifest in behavior, interpersonal dynamics, and environmental shaping, effectively reinstantiating the symbol into reality.

This phenomenon reflects performative language theory (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969), where utterances do not merely describe but enact change. The Trio extends this by modeling performative recursion: symbolic input (language) generates cognitive simulation (thought), which actuates behavioral transformation (reality). This recursive loop is not linear but structurally cyclical, allowing for feedback, reinforcement, and semantic layering.

In educational contexts, this model supports event-based language acquisition. Learners observe real-world events, simulate them cognitively, and encode them linguistically—mirroring the triadic recursion. This approach aligns with Tomasello’s (2003) usage-based theory, which emphasizes interaction and intention in language development. The Trio adds structural clarity, enabling learners to map entity-state-behavior couplings and recursively enrich meaning through modifiers.

In computational linguistics, the Trio offers a scaffold for semantic parsing. EMji/VMji notation allows for depth-aware tracking of modifiers, supporting semantic role labeling (Gildea & Jurafsky, 2002) and enhancing interpretability in transformer-based models (Vaswani et al., 2017). Sentences become semantic cells, not token sequences—structured reflections of reality.

Philosophically, the Law of the Trio reframes debates on meaning, reference, and symbol. Frege’s distinction between sense and reference becomes a recursive coupling. Wittgenstein’s insight that “meaning is use” gains ontological extension: use becomes recursive expression of being. Peirce’s triadic semiotics finds formal elaboration here—not merely interpretant chains, but structural recursion across modalities.

In sum, the Law of the Trio models language, thought, and reality as structurally equivalent systems, each capable of encoding the same semantic event. This triadic recursion offers a unified framework for understanding meaning—not as isolated symbol or mental representation, but as recursive enactment of existence. It invites linguistics to move beyond descriptive formalism toward ontological modeling, where every sentence becomes a symbolic invocation of being.

3. Meaning, Existence, and the Law of the Trio: An Intricate Interconnection

Meaning is not a static property nor a mere linguistic artifact—it is the fundamental essence of existence. It emerges from the state and conditions of an entity, as well as from its interactions with other entities and systems. This view aligns with contemporary theories in cognitive science and semiotics, which treat meaning as a dynamic, relational construct shaped by perception, context, and symbolic mediation (Barsalou, 1999; Peirce, 1931–1958). The Law of the Trio builds upon this foundation, proposing that meaning manifests in three structurally equivalent yet formally distinct modalities: thought, language, and reality. Each modality not only embodies meaning but also participates in its recursive generation and transformation, forming a unified semantic fabric.

3.1. Meaning as the Essence of Existence

At its core, meaning is inherent in the very state of being. Every entity carries meaning through its attributes, conditions, and the interactions it establishes with its environment. This echoes the ecological semantics proposed by Zlatev (2005), where meaning arises from embodied intersubjectivity and environmental embeddedness. Consider a tree: its meaning is not confined to its physical form—branches, leaves, roots—but extends to its ecological role, its symbolic associations, and its perceptual impact. It produces oxygen, shelters organisms, and evokes cultural metaphors. In this sense, meaning is not a property but a relational emergence—a product of interaction, perception, and systemic integration.

This perspective resonates with frame semantics (Fillmore, 1982), which posits that meaning is structured by experiential domains and relational roles. The tree’s meaning is framed by its function in the ecosystem, its affordances, and its symbolic resonance. Similarly, conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) shows how entities acquire layered meaning through metaphorical projection—e.g., “growth” as both botanical and personal development.

The Law of the Trio extends these insights by modeling meaning as a recursive coupling of entity, state, and behavior, expressed across modalities. Meaning is not merely interpreted—it is enacted through structural recursion.

3.2. The Law of the Trio: Thought, Language, and Reality

The Law of the Trio posits that meaning, as a reflection of existence, encapsulates the attributes and behaviors of entities and their interactions. It manifests in three interdependent dimensions:

Language

Representation: Language encodes entities and their states through structured syntax, symbols, and signs.

Role: It externalizes meaning, enabling communication, analysis, and preservation across time and space.

This view aligns with Langacker’s (1987) cognitive grammar, which treats linguistic constructions as symbolic pairings of form and meaning. Language is not a neutral conduit—it is a semantic architecture that mirrors cognition and reality.

Thought

Representation: Thought models entities as mental images or conceptual structures.

Role: It constitutes the subjective process of understanding, simulating, and interpreting existence.

This echoes Barsalou’s (1999) theory of perceptual symbol systems, where cognition is grounded in sensory-motor experience and structured through simulation. Thought is not abstract—it is embodied recursion.

Reality

Representation: Reality denotes the physical instantiation of entities, where their states and behaviors unfold.

Role: It provides the empirical substrate for meaning—observable, measurable, and interactive.

This dimension reflects Peirce’s object domain in triadic semiotics, where the referent anchors the sign’s meaning. Reality is not passive—it is a semantic source, shaping and shaped by thought and language.

Together, these dimensions form a

triadic circuit of meaning. Each modality encodes the same semantic event under different symbolic pressures. This is formalized by the Trio’s core function:

where

Modality may be language, thought, or reality. This function models how meaning arises from recursive coupling, enabling cross-modal alignment and semantic invariance.

3.3. Interplay Between Dimensions

The relationship among thought, language, and reality is not linear but cyclical and reciprocal. Each modality influences and is influenced by the others:

Thought generates meaning, shaping perception and guiding behavior. Cognitive models simulate events, anticipate outcomes, and structure interpretation (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002).

Language organizes thought into communicable structures. It transforms internal models into external symbols, enabling shared understanding and cultural transmission (Jackendoff, 2002).

Reality grounds both thought and language, providing empirical feedback and perceptual anchoring. It validates or challenges symbolic representations, prompting cognitive and linguistic adjustment.

This triadic interplay reflects conceptual blending theory (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002), where mental spaces integrate structure and experience to produce emergent meaning. The Trio formalizes this integration across modalities, treating each as a recursive lens on existence.

For example, consider the utterance: “The exhausted hiker slowly descended the icy slope.”

In reality: A physical event involving terrain, movement, and environmental resistance.

In thought: A cognitive simulation of fatigue, effort, and spatial orientation.

In language: A structured sentence encoding entity (hiker), behavior (descended), and modifiers (exhausted, slowly, icy).

Each modality reflects the same semantic event, recursively enriched by modifiers. This recursive layering is modeled through EMji/VMji notation, enabling formal tracking of semantic depth.

The cyclical nature of this interplay also supports performative language theory (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969), where utterances enact change. A spoken word can reshape cognition, which in turn alters behavior and transforms reality. The Trio extends this by modeling performative recursion—symbolic input becomes cognitive simulation, which actuates real-world transformation.

This recursive loop is foundational to language acquisition. Learners observe events, simulate them mentally, and encode them linguistically. This mirrors usage-based models (Tomasello, 2003), but adds structural clarity. The Trio provides a scaffold for event-based encoding, supporting retention, transfer, and semantic coherence.

In computational contexts, this triadic recursion informs semantic parsing. EMji/VMji notation enables depth-aware modifier tracking, supporting semantic role labeling (Gildea & Jurafsky, 2002) and enhancing interpretability in transformer-based models (Vaswani et al., 2017). Sentences become semantic particles, not token sequences—structured reflections of reality.

Philosophically, the Law of the Trio reframes meaning as ontological recursion. It synthesizes Frege’s sense-reference distinction, Wittgenstein’s “forms of life,” and Peirce’s triadic logic into a unified model. Meaning is not inferred—it is constructed across modalities.

In sum, the Law of the Trio reveals meaning as a recursive enactment of existence. Thought, language, and reality are not separate domains—they are structurally equivalent systems that encode the same semantic architecture. This triadic model offers a new lens for linguistics, cognitive science, and semiotics—one that treats every sentence, concept, and perception as a recursive invocation of being.

4. Communication as Ontological Recursion Across Modalities

Communication is not a linear transmission of information—it is a recursive invocation of existence across the triadic modalities of reality, thought, and language. What we commonly refer to as “communication skills”—reading, writing, listening, and speaking—are in fact structured processes of semantic transduction, wherein experience is encoded into symbolic form and symbolic input is decoded into cognitive and perceptual resonance.

Each communicative act enacts a transformation:

From perceived or imagined entities and their states or behaviors (reality/thought)

Into linguistic expression, or vice versa

This transformation is governed by the

Law of the Trio, which formalizes communication as:

Here, modality refers to the ontological domain in which meaning is instantiated:

Reality: perceptual instantiation

Thought: cognitive modeling

Language: symbolic encoding

These modalities operate in recursive interplay. Each sentence becomes a semantic particle—encoding identity, transformation, and relational depth. Communication, therefore, is not merely a technical skill but a structured resonance of being. The subsections that follow unpack this recursive cycle across linguistic, pedagogical, and computational dimensions, revealing how the Law of the Trio reframes communication as ontological recursion rather than syntactic manipulation or pragmatic exchange.

4.1. Encoding and Decoding Across Modalities

In speaking and writing, individuals begin with perceptual or conceptual input—an observed event, an imagined scenario, or a remembered experience. This input is cognitively modeled as a mental representation, which is then transduced into linguistic form. This process aligns with Jackendoff’s (2002) parallel architecture model, where conceptual structure interacts with syntax and phonology to produce coherent expression.

Conversely, in listening and reading, linguistic input is decoded into mental imagery and interpreted against the backdrop of real-world knowledge. This decoding process reflects Kintsch and van Dijk’s (1978) model of text comprehension, where surface linguistic forms are transformed into macrostructures of meaning through cognitive integration.

The Law of the Trio formalizes this bidirectional flow through its core semantic function:

Here, Modality may be language (symbolic encoding), thought (cognitive modeling), or reality (perceptual instantiation). Communication involves recursive movement across these modalities, with sentences serving as semantic particles that encapsulate identity, transformation, and relational depth.

4.2. Sentence as Semantic Unit of Communication

In any language system, the fundamental structure of communication is typically expressed through a single sentence. This sentence encodes:

Entity: the subject or ontological anchor

State or Behavior: the action, condition, or transformation

Modifiers: recursive enrichments that specify quality, manner, temporality, and context

This triadic structure mirrors Langacker’s (1987) cognitive grammar, where grammatical constructions are symbolic assemblies of conceptual content. It also resonates with Fillmore’s (1982) frame semantics, which models meaning as structured by relational roles and experiential domains.

For example, consider the sentence: “The exhausted hiker slowly descended the icy slope.”

This sentence encodes:

Entity: hiker

EM12: exhausted (modifier of entity)

Behavior: descended

VM12: slowly (modifier of behavior)

Object: slope

EM12.2: icy (modifier of object)

Each modifier adds semantic depth, reflecting perceptual, emotional, and environmental dimensions. This recursive layering is modeled through the EMji/VMji notation, which enables formal tracking of modifier hierarchy and semantic recursion.

4.3. Communication as Recursive Semantic Conversion

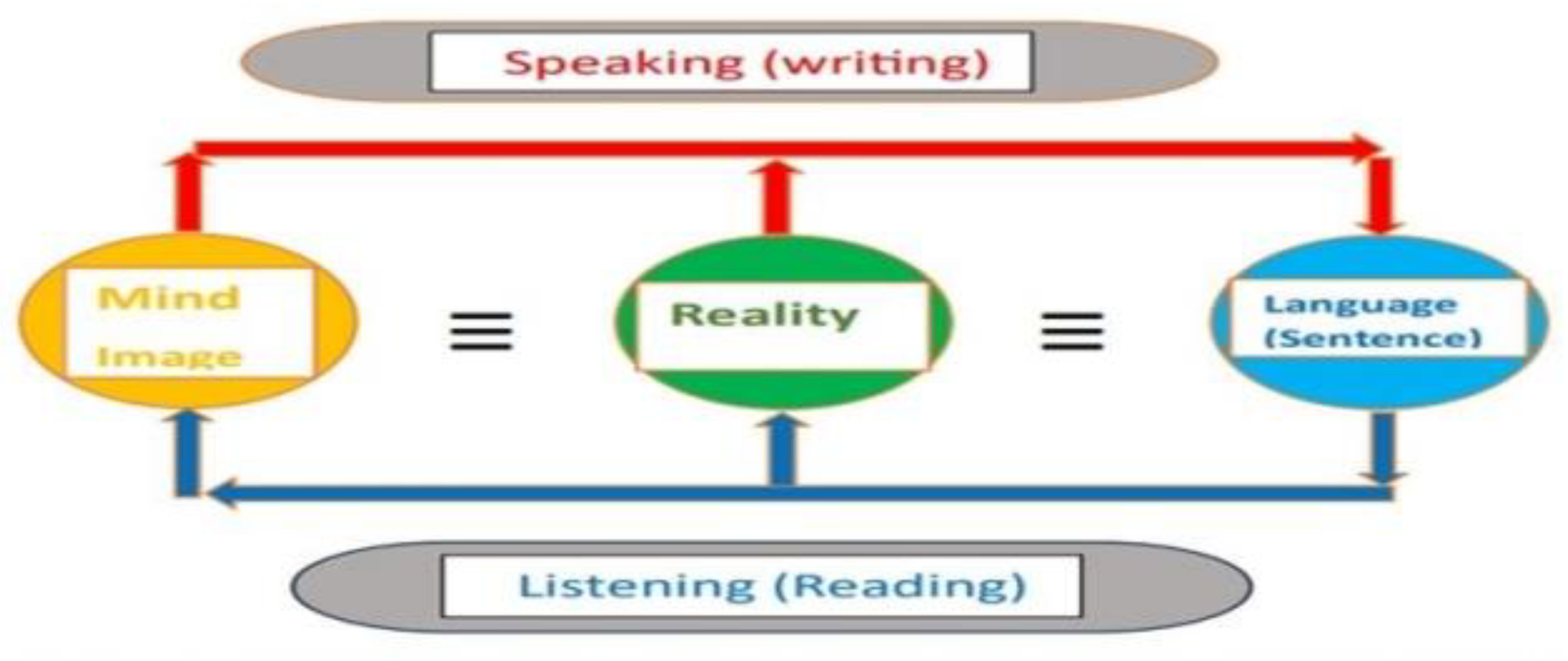

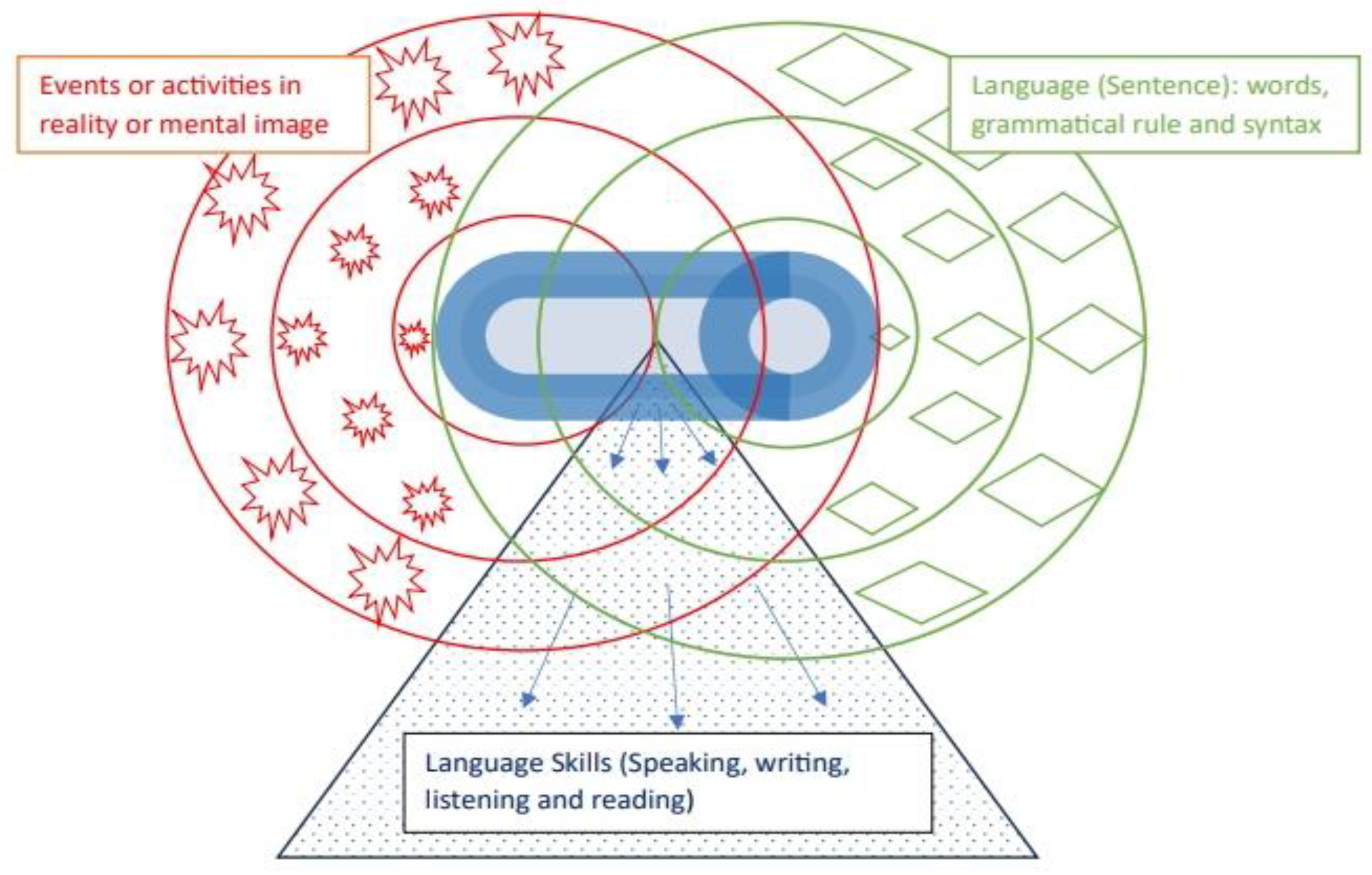

Figure 1.

Illustrates communication as a process of semantic conversion across modalities. It maps the recursive flow from:.

Figure 1.

Illustrates communication as a process of semantic conversion across modalities. It maps the recursive flow from:.

Reality → Thought: perceptual encoding and experiential simulation

Thought → Language: conceptual encoding and linguistic transduction

Language → Thought: symbolic decoding and cognitive reconstruction

Thought → Reality: cognitive actuation and behavioral manifestation

Language → Reality: performative activation and ontological reinstantiation

This model aligns with Fauconnier and Turner’s (2002) conceptual blending theory, where mental spaces integrate structure and experience to produce emergent meaning. The Trio formalizes this integration across modalities, treating each communicative act as a recursive semantic invocation.

4.4. Comparative Insights from Linguistic Paradigms

Traditional linguistic paradigms offer partial models of communication:

Generative grammar (Chomsky, 1965) models sentence formation as rule-based derivation, but abstracts away from meaning and context.

Functionalism (Halliday, 1994; Givón, 1995) emphasizes communicative purpose, treating language as adaptive behavior.

Cognitive linguistics (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Langacker, 1987) anchors meaning in embodied experience and conceptual mapping.

The Law of the Trio synthesizes these insights while resolving their limitations. It treats communication not as rule application, pragmatic adaptation, or metaphorical projection—but as ontological recursion. Each sentence becomes a symbolic enactment of existence, encoding entity-state-behavior couplings across modalities.

4.5. Pedagogical and Computational Implications

In language education, this model supports event-based instruction. Learners observe real-world events, simulate them cognitively, and encode them linguistically. This approach complements Content-Based Instruction (Doughty & Long, 2003) and Processing Instruction (VanPatten, 2015), but adds structural clarity through semantic recursion.

In computational linguistics, the Trio provides scaffolding for semantic parsing. EMji/VMji notation enables depth-aware modifier tracking, supporting semantic role labeling (Gildea & Jurafsky, 2002) and enhancing interpretability in transformer-based models (Vaswani et al., 2017). Communication becomes not statistical prediction, but structured semantic modeling.

In sum, communication—whether spoken, written, heard, or read—is a recursive semantic cycle. It transforms experience into symbol and symbol into cognition, guided by the triadic architecture of the Law of the Trio. Each sentence becomes a semantic particle, encoding the architecture of reality through structured recursion. This reframing elevates communication from transmission to ontological invocation—a structured resonance of being across modalities.

5. Universality and Variation of Languages

Are the 6,000 to 7,000 spoken languages that exist today completely different, or do they share a deeper structural unity?

The Law of the Trio—which posits reality, thought (or mental image), and natural language as structurally equivalent modalities—offers a compelling answer: all languages are fundamentally the same in their semantic architecture, even as they diverge in surface form. Each language encodes the coupling of entities and their states or behaviors, whether drawn from perceptual reality, cognitive simulation, or a blend of both. This coupling is universally expressed through the sentence, which serves as the semantic particle of communication.

5.1. Structural Universality: Sentence as Semantic Particle

Across linguistic systems, the sentence remains the core unit of meaning. Whether in English, Amharic, Japanese, or Quechua, a sentence encodes:

Entity: the ontological anchor (subject or noun)

State/Behavior: the transformation or condition (verb)

Modifiers: recursive enrichments of quality, manner, temporality, and context

This triadic structure reflects the semantic function formalized by the Law of the Trio:

Here, Modality may be reality (perception), thought (mental image), or language (symbolic expression). The sentence becomes a recursive invocation of existence—translating experience into structured symbol.

5.2. Cognitive Grounding: From Perception to Thought

The human sensory system converts environmental stimuli into electrical signals, which are processed by the central nervous system. This results in mental images—cognitive representations of entities characterized by properties or behaviors. When these images arise from sensory input, we call them perceptions. As experience accumulates, the mind organizes these images into hierarchical categories:

Entities and their attributes

Sub-entities and sub-sub-entities

Relational networks connecting entities across contexts

This cognitive architecture mirrors Barsalou’s (1999) theory of perceptual symbol systems, where mental representations are grounded in sensory experience and recursively enriched through conceptual layering.

5.3. Semantic Networks: Interconnected Mental Imagery

As entities interact across varied circumstances, the mind constructs semantic networks—interconnected mental images enriched by relational depth. These networks resemble frame semantics (Fillmore, 1982), where meaning emerges from structured domains of experience. The perceived realities are thus mental reconstructions of experienced realities, filtered through attention, memory, and conceptual abstraction.

This recursive modeling aligns with Langacker’s (1987) cognitive grammar, which treats linguistic constructions as symbolic assemblies of conceptual content.

5.4. Thought as Ontological Simulation

Driven by internal desire or external stimuli, the mind processes information to form new or modified mental images—what we call thoughts. These thoughts are capable of reshaping physical reality when conditions permit. Whether solving complex problems or pursuing distant goals, thought operates through recursive coupling:

This mirrors Fauconnier and Turner’s (2002) conceptual blending theory, where mental spaces fuse structure and experience to generate emergent meaning.

5.5. Language as Symbolic Encoding of Thought and Reality

In language, the connection between an entity and its behavior is encoded as a sentence. This is the universal feature of all languages. While languages differ in:

Lexical encoding (e.g., “tree” vs. “木” vs. “arbre”)

Grammatical rules (e.g., SVO vs. SOV vs. VSO)

Syntax structures (e.g., inflectional vs. isolating vs. agglutinative)

They all encode the same semantic function: the coupling of entities and behaviors across modalities. This universality supports Greenberg’s (1963) typological insights, while extending them into a triadic semantic framework.

5.6. Cross-Linguistic Equivalence: Surface Variation, Deep Unity

While speakers of different languages have unique life experiences, the mental processes underlying language use are structurally similar. Cognitive operations such as categorization, simulation, and recursive enrichment occur across cultures and linguistic systems. This echoes Slobin’s (1996) concept of “thinking for speaking,” where language shapes—but does not fundamentally alter—cognitive modeling.

The Law of the Trio reframes this insight: languages differ in symbolic surface, but converge in semantic structure. Each sentence, regardless of language, encodes a triadic event—an entity in transformation, recursively enriched by modifiers.

5.7. Philosophical and Semiotic Resonance

This structural unity finds philosophical support in Peirce’s triadic semiotics, where meaning arises from the interplay of representamen (symbol), object (referent), and interpretant (cognition). It also resonates with Wittgenstein’s later work, which framed meaning as public and experiential—manifest in “forms of life.”

The Law of the Trio extends these traditions by treating the sentence as a semantic particle—a symbolic cell that encodes reality, thought, and language in recursive alignment.

In sum, the diversity of languages is a surface phenomenon. Beneath lexical variation and syntactic difference lies a universal semantic architecture—the triadic coupling of entity and behavior, recursively enriched and symbolically expressed. The Law of the Trio reveals that all languages are not merely similar—they are structurally homologous, ontologically equivalent, and cognitively resonant.

6. Recursive Semantic Geometry: Structuring Meaning Through Modifier Architecture

The architecture of information—whether in the physical realm, mental processes, or linguistic expression—is fundamentally relational. It is built upon the coupling of

entities and their

characteristics or actions, recursively enriched by modifiers. This triadic structure is formalized by the Law of the Trio:

Here, Modality may be reality (perception), thought (mental image), or language (symbolic expression). The sentence becomes the semantic particle through which this coupling is encoded, modeling events across modalities.

6.1. Core Sentence Structure: Entity–Behavior Coupling

As shown in Equation 1 (

Section 2), the core of a sentence links an

entity to its

attributes or behaviors within an event. This reflects the ontological logic of existence: entities exist in states, perform actions, and interact with other entities. In linguistic terms:

Subject (Head Noun): the entity in focus

Predicate (Head Verb + Complements): the state or activity of the entity, often in relation to others

This structure mirrors cognitive modeling, where mental representations simulate events by pairing entities with transformations. It also reflects perceptual reality, where external and internal factors alter an entity’s state.

6.2. Cross-Linguistic Variation and Semantic Invariance

While sentence structures vary across languages—e.g., English employs five verb types to depict status or behavior—semantic function remains invariant. The Law of the Trio ensures that:

Entity–Behavior coupling is universal

Modifier recursion enables depth and specificity

Sentence structure reflects semantic anatomy, not just grammatical form

Languages use finite grammatical tools to express infinite experiential scenarios. This is achieved through recursive modification, where adjectives, adverbs, phrases, and clauses enrich the core sentence.

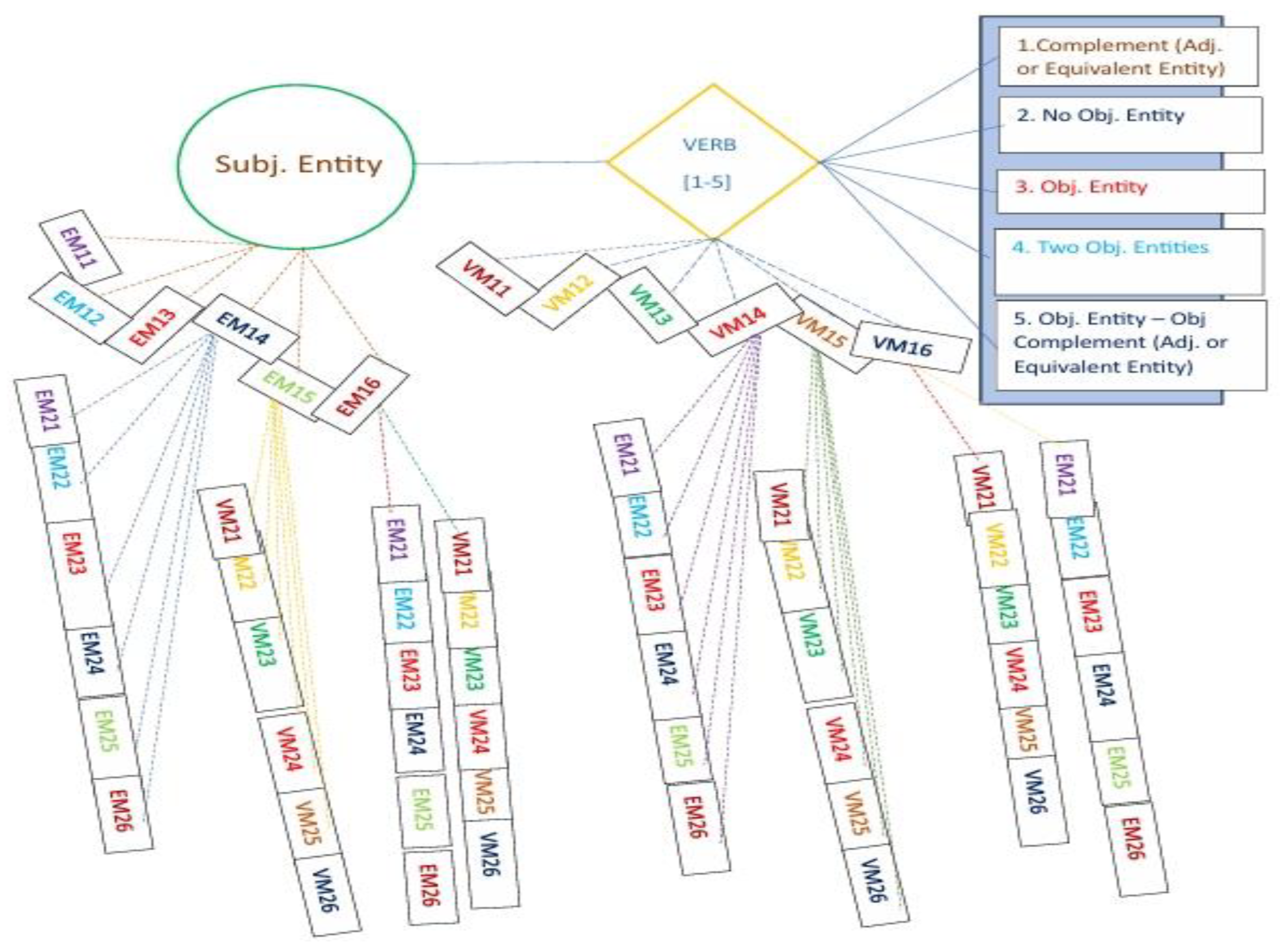

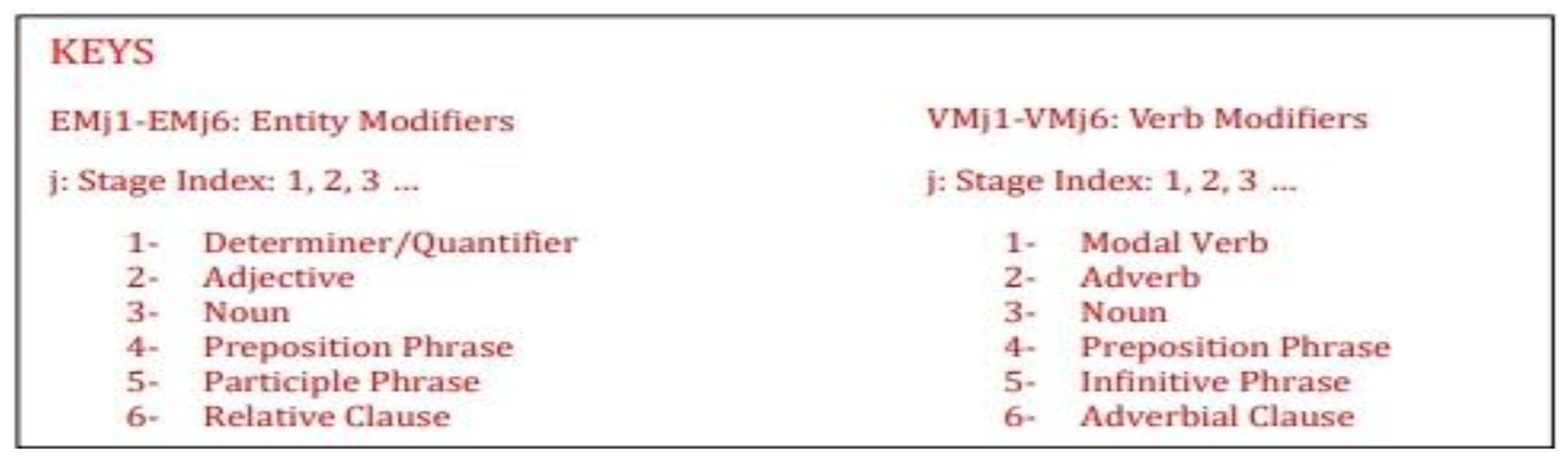

6.3. Modifier Hierarchy: EMji and VMji Notation

Modifiers transform simple sentences into complex ones by adding layers of semantic detail. In the Trio framework, these are modeled as:

EMji: Entity Modifiers, where i is the modifier type and j is the recursion level

VMji: Verb Modifiers, with parallel structure

6.3.1. Noun Modification Techniques (EMji)

English typically employs six techniques to modify noun entities:

Table 1.

Triadic Modifier Techniques for Noun Entities (EMji Notation).

Table 1.

Triadic Modifier Techniques for Noun Entities (EMji Notation).

| Modifier Type |

Description |

EMji Notation |

| 1.Determiner/Quantifier |

Specifies scope or quantity |

EM11 |

| 2. Adjective |

Describes quality or state |

EM12 |

| 3. Noun |

Compound or appositional modifier |

EM13 |

| 4. Prepositional Phrase |

Relational context |

EM14 |

| 5. Participle Phrase |

Describes action or condition |

EM15 |

| 6. Clause |

Adds event-based information |

EM16 |

Example: “The exhausted hiker admired by critics who follow avant-garde trends…”

6.3.2. Verb Modification Techniques (VMji)

English also employs six techniques to modify verbs:

Table 2.

Recursive Verb Modification Techniques (VMji Notation).

Table 2.

Recursive Verb Modification Techniques (VMji Notation).

| Modifier Type |

Description |

VMji Notation |

| 1. Modal Verb |

Indicates possibility or necessity |

VM11 |

| 2. Adverb |

Describes manner or intensity |

VM12 |

| 3. Noun |

Temporal or circumstantial indicator |

VM13 |

| 4. Prepositional Phrase |

Adds relational context |

VM14 |

| 5. Infinitive Phrase |

Purpose or result |

VM15 |

| 6. Adverbial Clause |

Event-based elaboration |

VM16 |

Example: “She confidently presented the piece at the theatre near the river to find a seat despite the rain.”

VM12: confidently

VM14: at the theatre

VM14.2: near the river

VM15: to find a seat

VM16: despite the rain

Each modifier recursively enriches the verb, adding layers of semantic depth and experiential realism.

6.4. Recursive Modification and Hierarchical Structure

Modifiers are not limited to head nouns or verbs. Any noun or verb functioning as a modifier can itself be modified using the same techniques. This creates a hierarchical structure within the sentence—an open-ended semantic scaffold.

For example: “The student revised her essay written during the storm in the library.”

This recursive layering mirrors cognitive modeling, where mental images are enriched by nested attributes and relational contexts.

6.5. Multi-Entity Sentences and Cross-Modal Mapping

In events involving multiple independent entities, the sentence must encode the status or action of each entity, along with associated modifiers. This requires:

Multiple entity–behavior couplings

Cross-modal alignment of semantic roles

Recursive modifier tracking across domains

Languages may vary in how they express subject–verb agreement, tense, or aspect, but the underlying semantic structure remains consistent.

6.6. Figure 2: Recursive Modifier Mapping

Entity Modifiers (EMji): layered enrichments of noun identity

Verb Modifiers (VMji): layered elaborations of action or state

Recursive Depth (j): levels of semantic nesting

This schematic reframes syntactic structure as semantic geometry—a recursive map of meaning across modalities.

In sum, syntactic structures—whether simple or complex—are recursive semantic architectures. They encode the triadic coupling of entity and behavior, enriched by modifiers that reflect perception, cognition, and symbolic expression. The Law of the Trio elevates syntax from grammatical engineering to ontological modeling, where every sentence becomes a symbolic particle of existence.

7. Acquisition of First Language: A Triadic Ontological Perspective

The process by which children acquire language without formal instruction remains one of the most debated topics in linguistics and cognitive science. The lack of consensus on the fundamental nature of language has given rise to a spectrum of theories—from nativist models that posit innate grammatical structures (Chomsky, 1965; Pinker, 1996) to usage-based and interactionist frameworks that emphasize environmental input and cognitive generalization (Tomasello, 2003; Bybee, 2010). Rather than adjudicating among these paradigms, this section offers a reframing of first language acquisition through the lens of the Law of the Trio, which models language, thought, and reality as structurally equivalent modalities of existence.

7.1. Developmental Modality Shifts: From Reality to Language

In early childhood, the role of thought as a distinct modality is minimal. Infants and toddlers primarily engage in a recursive loop between language and reality, absorbing symbolic input from their environment and mapping it onto perceptual experience. This aligns with Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory, which posits that external speech precedes internal thought, and that language acquisition is mediated by social interaction and environmental scaffolding.

The observed slowdown in language acquisition around ages 7 to 8 may reflect the increasing influence of thought—as children begin to generate abstract representations, simulate hypothetical scenarios, and manipulate symbolic structures internally. This developmental shift marks the emergence of triadic recursion, where language, thought, and reality begin to interact more dynamically.

7.2. Language–Reality Coupling in Early Childhood

Contrary to nativist claims that language emerges spontaneously as an instinctive behavior (Pinker, 1996), the Law of the Trio suggests that children acquire language through recursive coupling of linguistic symbols with perceptual events. This process is grounded in the equivalence between language and reality—a relationship that children intuitively grasp. They exhibit remarkable adaptability to their surroundings, attending to both linguistic input and concurrent physical activity with equal sensitivity.

This observation resonates with Tomasello’s (2003) usage-based theory, which emphasizes intention-reading, joint attention, and pattern recognition as foundational mechanisms of language acquisition. Children do not merely absorb words—they map them onto entities, states, and behaviors observed in their environment, forming semantic particles that mirror the structure of experience.

7.3. Perceptual Grounding and Semantic Mapping

Children perceive each sound from caregivers and role models alongside a rich tapestry of nonverbal cues—facial expressions, gestures, body movements, and environmental context. This multimodal input supports

semantic mapping, where sounds are linked to real-world referents and actions. The Law of the Trio formalizes this process as:

Here, Language functions as a modality that encodes perceptual reality. The child hears the word “dog” while observing a barking animal, and recursively enriches this mapping with modifiers—“big dog,” “running dog,” “dog under the table.” Each sentence becomes a semantic particle, encoding identity, transformation, and relational depth.

This recursive mapping aligns with Barsalou’s (1999) theory of perceptual symbol systems, which posits that cognition is grounded in sensory-motor experience and structured through simulation. Children simulate events mentally, then encode them linguistically—mirroring the triadic recursion of the Law of the Trio.

7.4. Progression from Lexical Acquisition to Sentence Construction

Language acquisition begins with basic elements: naming objects, identifying actions, and expressing emotions. These are the building blocks of entity–behavior coupling. As children gain experience, they begin to comprehend sentence sequences, recognize modifier hierarchies, and combine multiple sequences to express complex ideas.

This progression reflects the development of recursive semantic architecture, modeled through EMji/VMji notation:

EMji: Entity Modifiers (e.g., “red ball,” “tired dog”)

VMji: Verb Modifiers (e.g., “runs quickly,” “sleeps under the bed”)

Children intuitively layer modifiers, constructing sentences that reflect not only grammatical rules but ontological structure. This recursive layering supports retention, clarity, and cross-modal alignment.

7.5. Environmental Input and Semantic Resonance

The Law of the Trio challenges the notion that language is biologically hardwired and emerges independently of experience. Instead, it posits that language and reality are absorbed from the environment, and that acquisition is driven by semantic resonance—the recursive alignment of symbol with experience.

This view complements VanPatten’s (2015) Processing Instruction, which emphasizes form–meaning connections and input-driven learning. It also aligns with Kintsch and van Dijk’s (1978) model of text comprehension, where meaning is constructed through macrostructural integration of linguistic and experiential input.

7.6. Ontological Implications for Language Development

From a Trio perspective, language acquisition is not merely a cognitive achievement—it is an ontological enactment. Each sentence constructed by a child reflects a triadic event:

In reality: a perceptual experience

In thought: a cognitive simulation

In language: a symbolic encoding

This recursive loop supports not only linguistic fluency but conceptual development, emotional regulation, and social interaction. Language becomes a scaffold for being—not just a tool for communication.

In sum, the acquisition of first language is best understood as a recursive process of semantic alignment across modalities. Children do not acquire language by memorizing rules or activating innate modules—they build it by observing reality, simulating experience, and encoding meaning through structured symbol. The Law of the Trio reframes language learning as ontological recursion, where every word, phrase, and sentence becomes a symbolic invocation of existence.

8. Acquisition of Second Language: Event-Based Recursion and Ontological Encoding

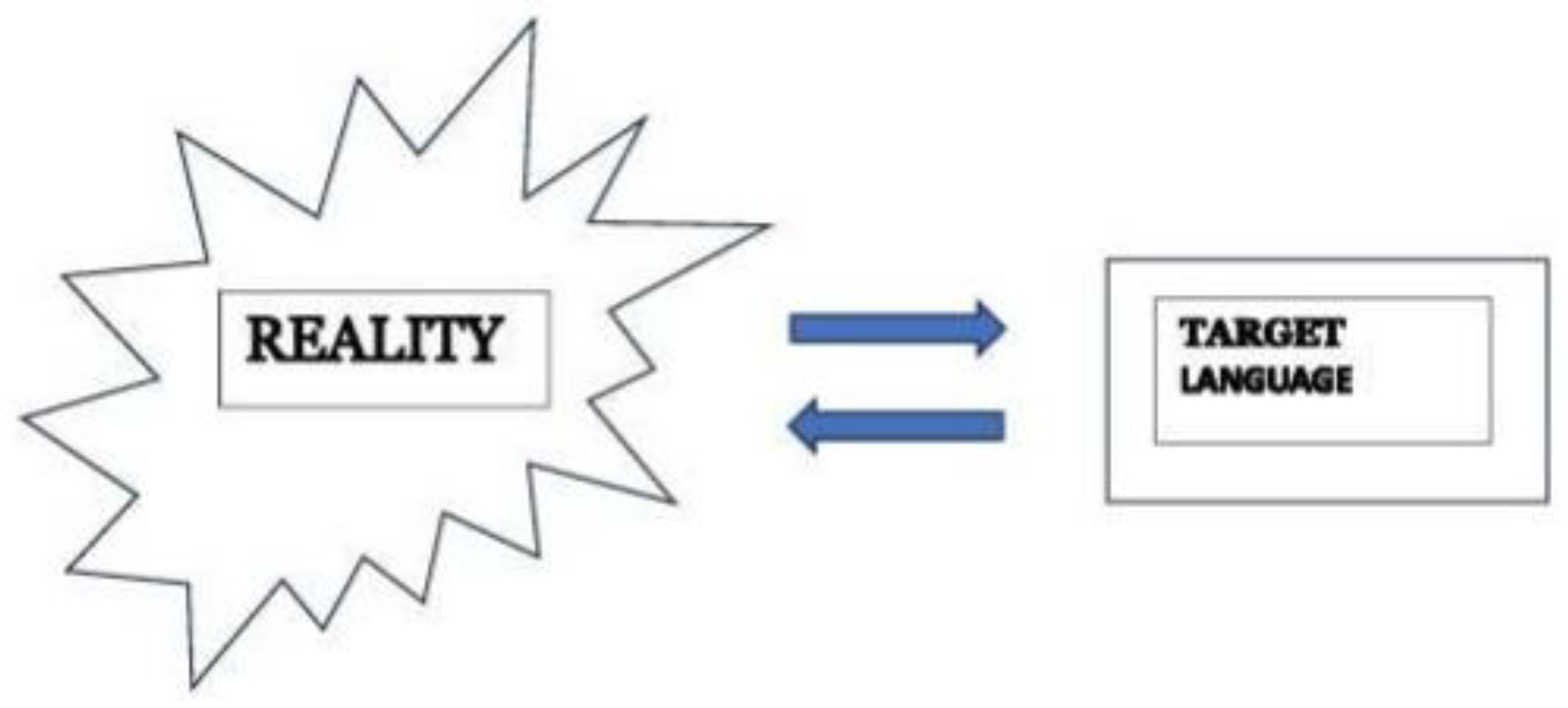

Second language acquisition (SLA) presents a unique cognitive and ontological challenge: the learner must reconcile thought and reality through the symbolic structures of a new linguistic system. While the learner’s first language and the target language share the same existential purpose—encoding events through sentence formation—their surface grammars differ. This section reframes SLA through the Law of the Trio, positing that the most effective path to mastery lies in event-based recursion, where reality serves as the primary referent for linguistic encoding.

8.1. Structural Equivalence Across Languages

Both the acquired and target languages function as symbolic mirrors of reality. Each sentence represents a triadic coupling:

Entity: the subject or object of existence

State/Behavior: the transformation or action

Modifiers: recursive enrichments of context, condition, and relation

This structure is formalized by the Trio’s semantic function:

Here, Modality refers to language, thought, or reality—each capable of encoding the same existential event. Thus, SLA is not the memorization of foreign forms, but the reconstruction of reality through a new symbolic lens.

8.2. Reality as Anchor: Eliminating L1 Interference

Traditional SLA methods often rely on translation or syntactic mapping from the first language (L1), leading to transfer errors and cognitive overload (VanPatten, 2015). The Law of the Trio proposes a reversal: learners should anchor their acquisition in reality, not in L1 structures. By observing events and encoding them directly in the target language (L2), learners bypass interference and engage in semantic modeling.

This approach aligns with

Content-Based Instruction (Doughty & Long, 2003) and

usage-based theories (Tomasello, 2003), but adds ontological depth.

Figure 3 illustrates this recursive loop:

8.3. Sentence as Semantic Bullet: Encoding Events with Precision

A sentence is not a linear string of words—it is a semantic projectile, aimed at a specific event in reality. Like a bullet hitting a target, a sentence encapsulates:

This metaphor echoes the Trio’s view of the sentence as a semantic particle—a symbolic cell encoding identity, transformation, and relation (Tesfa, 2025). Sentence-based learning allows simultaneous acquisition of vocabulary, syntax, and grammar, grounded in perceptual experience.

However, initial input must be carefully curated. Learners should begin with familiar events—those already understood in L1—before attempting to encode unfamiliar realities. This scaffolding supports cognitive resonance and semantic retention.

8.4. Event–Sentence Coupling: The Ontological Basis of Meaning

Language should not be reduced to word processing or syntactic manipulation. Each sentence reflects an event—either in physical reality or mental simulation. The meaning of a sentence arises from its effect on reality, not merely its internal structure.

For example, the sentence “The dog is barking” encodes a perceptual event. Yet its interpretation depends on context, prior experience, and relational dynamics. The barking may signal danger, familiarity, or emotional resonance. Thus, meaning is event-driven, not form-driven.

This view aligns with frame semantics (Fillmore, 1982) and conceptual blending theory (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002), which emphasize the role of context and experiential mapping in meaning construction.

8.5. Narrative Expansion: From Sentence to Semantic Chain

Events are rarely isolated. One event leads to another, forming semantic chains that evolve into narratives. A sentence becomes the seed of a story—its modifiers and clauses recursively enriching the ontological depth.

This recursive expansion is modeled through EMji/VMji notation, where:

EMji: Entity Modifiers

VMji: Verb Modifiers

Each modifier adds a layer of specificity, enabling learners to construct complex expressions from simple observations. This mirrors the developmental trajectory of L1 acquisition, where children build meaning by linking words to events (Tomasello, 2003).

8.6. Language Skills as Event Transformation

As shown in

Figure 1, language skills—speaking, writing, listening, and reading—are processes of

transforming events into symbolic form and vice versa. SLA involves mastering this transformation in the target language.

Each sentence corresponds to an event. The learner must observe, simulate, and encode that event using L2 structures. This process is metaphorically represented as a dumbbell (Figure 4)—with one plate as the event, and the other as the sentence. The learner lifts meaning by balancing both.

Words and syntax are best memorized when inextricably linked to events. The mind functions as an event–word processor: it perceives reality, then selects appropriate linguistic structures to describe it. This recursive loop supports retention, fluency, and semantic clarity.

8.7. Avoiding Word Processing: The Pitfall of Surface Learning

If SLA is reduced to word processing—memorizing isolated vocabulary and assembling sentences mechanically—the results are often disastrous. Learners produce grammatically correct but semantically hollow utterances.

The event processing approach, by contrast, integrates:

Perceptual grounding

Semantic recursion

Skill development

This integration is illustrated in

Figure 4:

This model supports deep learning, where language becomes a structured reflection of experience—not a disconnected code.

In sum, second language acquisition is not a technical exercise in grammar—it is an ontological enactment. By anchoring learning in reality, modeling events recursively, and encoding meaning through structured sentences, learners engage in a process that mirrors the architecture of existence itself. The Law of the Trio reframes SLA as semantic invocation, where every utterance becomes a symbolic act of being.

9. Conclusions—Language as Ontological Geometry

The enigma of language—its origin, structure, and existential function—has long challenged scholars across disciplines. Through the lens of the Law of the Trio, this manuscript offers a resolution that is both conceptual and structural: language, thought, and reality are not merely interrelated—they are structurally homologous modalities of existence. Each encodes the same semantic architecture: the recursive coupling of entities with their states or behaviors, enriched by layered modifiers and expressed through symbolic form.

This triadic framework reframes language not as a passive mirror of cognition or a utilitarian tool of communication, but as a

semantic invocation of being. Meaning is revealed as both

inherent—embedded in the structure of existence—and

emergent—shaped by recursive interaction across modalities. The Law of the Trio formalizes this through the semantic function:

This function underpins a wide array of linguistic phenomena explored throughout the manuscript:

Universality across languages: Despite surface variation, all languages encode the same triadic semantic structure.

Syntactic organization: Sentence formation is modeled as recursive semantic geometry, not rule-based derivation.

Language acquisition: Both first and second language learning are reframed as event-based semantic modeling.

Communication skills: Speaking, writing, listening, and reading are recursive transformations across reality, thought, and language.

The introduction of EMji/VMji notation provides a formal scaffold for tracking modifier hierarchy and semantic depth, enabling precise modeling of linguistic complexity across typologies and modalities. This recursive architecture positions the sentence as a semantic particle—a symbolic cell that encodes identity, transformation, and relational nuance.

Philosophically, the Law of the Trio synthesizes and extends foundational insights from Peirce’s triadic semiotics, Wittgenstein’s public meaning, and Frege’s sense–reference distinction. It transforms these constructs into a unified model of structural ontology, where language is not merely descriptive but constitutive of reality.

Cross-disciplinary implications abound:

In education, the Trio supports reality-based curriculum design, enhancing retention and learner fluency.

In cognitive science, it offers a framework for modeling perception, memory, and semantic load.

In artificial intelligence, it provides depth-aware scaffolding for semantic parsing and symbolic cognition.

In intercultural communication, it enables modality-neutral semantic alignment across languages.

In philosophy, it reframes meaning as recursive enactment, not abstract inference.

Ultimately, the Law of the Trio invites a reimagining of linguistics—not as a fragmented study of form, function, or cognition, but as a science of meaning grounded in ontological recursion. It offers a lens through which language may be newly seen—not as a system of signs, but as a structured resonance of existence.

“A sentence is not built—it becomes. Not through rules, but through recursion. Not through function, but through form-as-being.”

This work marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of linguistic thought—one that bridges theory and practice, symbol and experience, structure and meaning. It lays the foundation for a new linguistic science: one capable of articulating the recursive logic of existence through the symbolic geometry of language.

Author Contributions

The author independently conceived, developed, and refined the theoretical architecture of the Law of the Trio, including its semantic function modeling, recursive modifier notation (EMji/VMji), and cross-modal framework. All writing, comparative synthesis, structural design, and philosophical integration were undertaken solely by the author. AI dialogue systems were engaged recursively throughout the revision process to support editorial clarity, structural coherence, and semantic precision.

Funding

This research was conducted without external funding. All conceptual development, manuscript preparation, and iterative refinement were carried out independently by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study is theoretical and does not involve human participants, empirical data collection, or ethical review procedures.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The manuscript contains no personal data, identifiable imagery, or content requiring publication consent.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No datasets were generated, collected, or analyzed during the course of this theoretical inquiry.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the recursive editorial partnership with AI-based dialogue systems, whose semantic scaffolding and structural feedback contributed meaningfully to the clarity and depth of the manuscript across multiple revision phases. Special thanks to the broader academic community—colleagues, readers, and interlocutors—whose engagement with Unlocking Language and its earlier iterations helped shape key refinements and philosophical expansions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing financial, institutional, or personal interests related to the content, methodology, or dissemination of this work.

References

- Aristotle. (350 BC). De Interpretatione.

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford University Press.

- Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4), 577–660.

- Bybee, J. (2010). Language, usage and cognition. Cambridge University Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2013). Problems of projection. Lingua, 130, 33–49.

- Doughty, C. J., & Long, M. H. (Eds.). (2003). The handbook of second language acquisition. Blackwell Publishing.

- Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. Basic Books.

- Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame semantics. In Linguistics in the morning calm (pp. 111–137). Hanshin Publishing.

- Frege, G. (1892). On sense and reference. Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, 100, 25–50.

- Gildea, D., & Jurafsky, D. (2002). Automatic labeling of semantic roles. Computational Linguistics, 28(3), 245–288. [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. (1995). Functionalism and grammar. John Benjamins.

- Greenberg, J. H. (Ed.). (1963). Universals of language. MIT Press.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold.

- Harris, R. (1993). The linguistics wars. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85(5), 363–394. [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of cognitive grammar: Theoretical prerequisites (Vol. 1). Stanford University Press.

- Peirce, C. S. (1931–1958). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vols. 1–8, C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss, & A. W. Burks, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

- Pinker, S. (1996). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. Harper Perennial.

- Saussure, F. de. (1916). Course in general linguistics (C. Bally & A. Sechehaye, Eds.; W. Baskin, Trans.). McGraw-Hill.

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Slobin, D. I. (1996). From “thought and language” to “thinking for speaking.” In J. J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96). Cambridge University Press.

- Speaks, J. (2024). Theories of meaning. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/meaning/.

- Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a cognitive semantics (Vols. 1–2). MIT Press.

- Tesfa, T. (2025). EMji/VMji notation and the Law of the Trio. Unpublished manuscript.

- Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language: A usage-based theory of language acquisition. Harvard University Press.

- VanPatten, B. (2015). While we’re on the topic: BVP on language, acquisition, and classroom practice. ACTFL.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Blackwell.

- World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS). (n.d.). https://wals.info/.

- Zlatev, J. (2005). The semiotic hierarchy: Life, consciousness, signs and language. Cognitive Semiotics, 1, 169–200.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).