Author’s Note

This article builds upon foundational insights first introduced in Unlocking Language: The Law of the Trio, where language, thought, and reality were modeled as structurally equivalent modalities of existence. That work marked a philosophical pivot: away from viewing language as a system of form and contrast, toward a framework rooted in ontological coherence, experiential grounding, and recursive semantic architecture. In that view, language emerged not as a passive code or utilitarian tool—but as a living system that mirrors the architecture of reality and the mechanics of thought itself.

In Reframing Linguistics, the Law of the Trio enters direct critical dialogue with generative grammar, structuralism, functionalism, and cognitive linguistics. Each paradigm has contributed vital theoretical assets: formal precision, oppositional structure, communicative function, and cognitive resonance. But when placed within a triadic lens, their limitations become clear.

Each theory makes vital contributions—but none fully engages with a deeper question: What is language structurally, ontologically, and existentially doing when it creates meaning?

This question forms the premise—not the footnote—of the Law of the Trio. Through recursive modifier notation (EMji/VMji), cross-modal modeling, and structural equivalences between sentences, mental representations, and real-world events, this framework offers more than a theoretical refinement. It proposes a reimagining of what language is—and what it does.

Rather than reject prior scholarship, this work synthesizes and extends it—placing language on firm ontological footing and repositioning linguistics as a natural science of meaning. It also lays groundwork for new frontiers across cognitive science, language education, digital communication, and intercultural understanding.

Above all, it invites renewed dialogue around the metaphysical terrain of language itself. For those drawn to the deeper existential function of meaning-making, this contribution offers a lens—structural, recursive, and ontologically grounded—through which language may be newly seen as a form of existence in its own right.

This philosophical foundation sets the stage for the current inquiry, which begins in

Section 1 by tracing the historical and theoretical lineage of linguistic paradigms that the Law of the Trio now reinterprets.

1. Introduction—From Syntax to Ontology

For over a century, modern linguistics has sought to untangle the complexities of language by segmenting its components—syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and phonology—into discrete analytical domains. This intellectual stratification can be traced to Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics (1916), which framed language as a system of signs defined through opposition, not reference. Saussure’s structuralism laid the groundwork for synchronically analyzing language as a formal system, abstracted from individual utterance or empirical reality.

Decades later, Noam Chomsky’s Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965) and The Minimalist Program (1995) revolutionized linguistic theory by introducing generative grammar and Universal Grammar—models that treated syntax as a self-contained computational system. Chomsky's emphasis on linguistic competence over performance shifted the discourse toward cognitive formalism and deep structural rules, often sidestepping issues of meaning, usage, and contextual interpretation.

Cognitive linguistics responded by reintroducing experiential grounding. Concepts like embodied meaning (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), image schemas (Johnson, 1987), and conceptual metaphor theory proposed that cognition shapes linguistic structure. Langacker’s Foundations of Cognitive Grammar (1987) further asserted that grammar is inherently meaningful and inseparable from usage. These scholars reframed linguistic units not as autonomous rules but as symbolic representations shaped by perception and experience.

Despite these pivotal contributions, prevailing models continue to treat language either as a structural mechanism (Chomsky), a relational code (Saussure), a communicative tool (Halliday, 1994), or a cognitive interface (Lakoff, 1987)—each isolating a fragment of meaning while rarely integrating reality, thought, and language into a unified whole. This fragmentation has obscured deeper ontological questions: What is language doing when it creates meaning—not just technically, but existentially?

This article introduces a new framework: the Law of the Trio, a triadic model that posits language, thought, and reality as structurally equivalent modalities of being. Unlike previous theories that segment linguistic analysis into functional silos, the Trio model proposes that all three domains reflect the same fundamental architecture: the recursive semantic coupling of entity and behavior, enriched by layered modifiers.

To formalize this equivalence, the Trio introduces a core semantic function:

Here, Modality refers to language, thought, or reality—each capable of encoding the same existential event under different symbolic pressures. Language is not merely the shadow of thought, nor a tool of communication—it is a carrier of being, a structured echo of existence filtered through symbolic recursion.

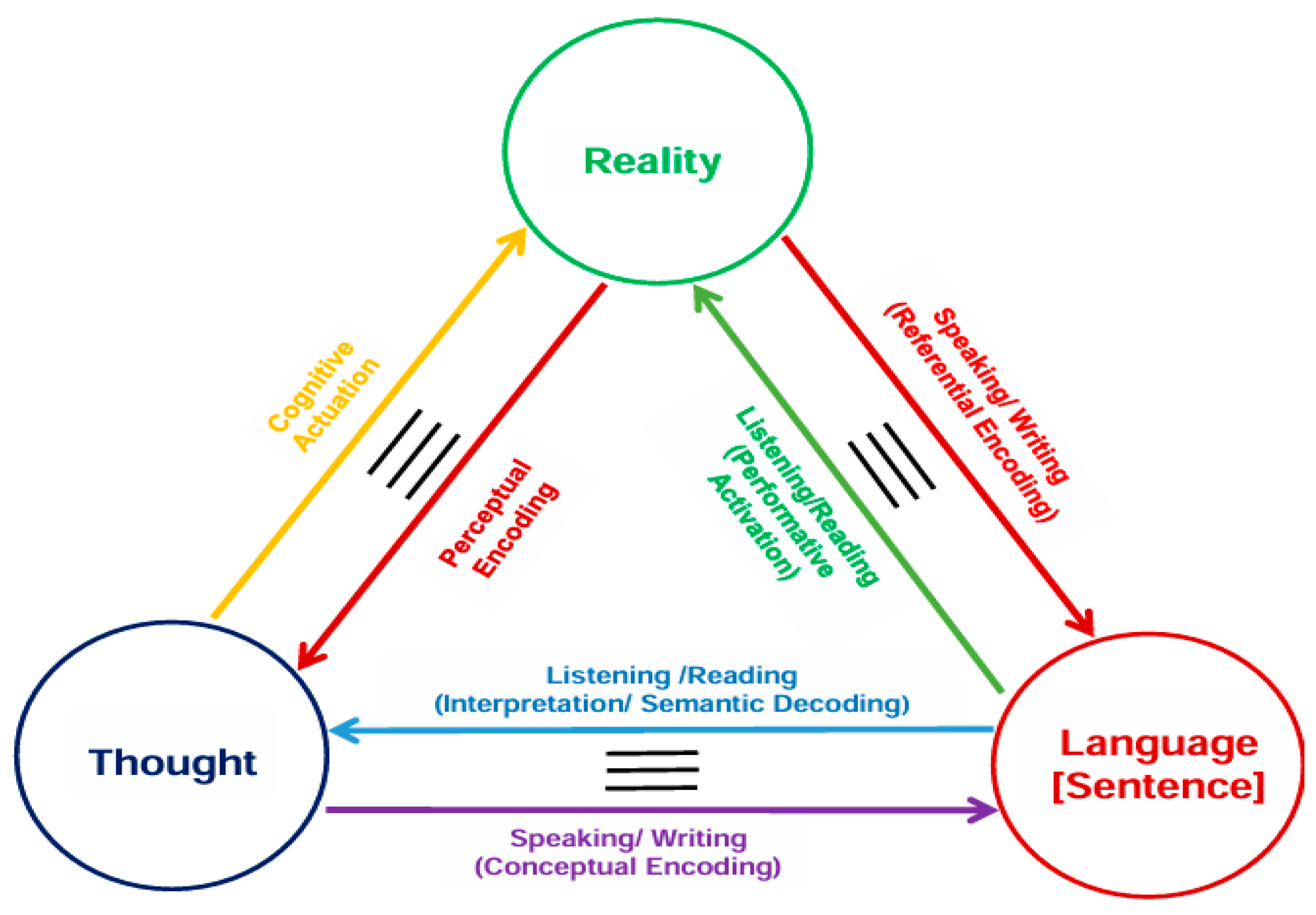

1.1. Structural Equivalence Across Modalities: Framing the Triadic Model

To visualize the foundational premise of the Law of the Trio—that reality, thought, and language are structurally parallel yet formally distinct—

Figure 1 presents a recursive flow map tracing semantic movement across domains.

Each modality functions as a semantic lens:

Reality — the physical or mental event as perceptual experience

Thought — the conceptual modeling of that experience

Language — the symbolic structure that encodes and transmits the experience

This diagram illustrates the foundational premise of the Law of the Trio: that reality, cognition, and language form a structurally equivalent triad. It maps the recursive flow from external events (perceived reality) to mental representation (thought), and then into linguistic encoding (language). Arrows show how sentences emerge from perception and cognition, encode meaning through recursive modifiers, and influence reality through interpretation and action.

Note: The EMji and VMji modifier notation introduced here is elaborated in detail in the foundational article, Unlocking Language: The Law of the Trio. Readers unfamiliar with the notation may refer to that work for a comprehensive modeling framework.

Following

Figure 1, the Law of the Trio unfolds as a phase-change model of communication, wherein symbolic acts mirror ontological shifts. Meaning transforms across modalities much like physical states—each transition marking a new form of semantic pressure.

1.2. Philosophical Lineage and Divergence

The Law of the Trio emerges from a long philosophical lineage rooted in semiotic recursion and ontological inquiry. It builds upon the triadic logic of Charles Sanders Peirce (1931–1958), whose sign theory posited the interdependence of representamen, object, and interpretant—a structure where meaning unfolds through recursive interpretation rather than fixed correspondence. It also resonates with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later work (Philosophical Investigations, 1953), which refuted solipsistic semantics and framed meaning as inherently public—manifest in “forms of life,” not isolated cognition.

Yet the Trio model diverges from these traditions in one decisive respect: it reframes the sentence itself not merely as a vessel of signification but as a semantic particle—a symbolic cell within the architecture of meaning. Just as DNA encodes biological identity via nucleotide sequences, the sentence encodes semantic identity through cascades of entities, states, and modifiers, recursively assembled across modalities. Each sentence thus becomes an ontological construct, reflecting not only internal thought but the structural pressures of reality.

This reconceptualization has immediate ramifications for theoretical and applied domains:

Sentence Formation → Syntax reframed as existential geometry

Second-Language Acquisition → Encoding strategies anchored in event-based recursion

Cognitive Modeling → Recursive scaffolds for symbolic simulation and meaning loops

Intercultural Communication → Modality-neutral structures for semantic transfer across languages

Rather than dismantling previous linguistic paradigms, the Law of the Trio reorients them—absorbing legacy insights while resolving foundational fragmentations.

Figure 1 and

Table 1 have already illustrated how recursion animates transitions across modalities. We now shift to a comparative view of major theoretical traditions, examining their treatment of language, thought, and reality, and how the Trio model reframes each within a unified ontological framework.

To illuminate this dialogue,

Table 2 maps each paradigm’s core assumption and modality lens, followed by the Law of the Trio’s recursive reinterpretation—revealing how structural divergence gives way to ontological integration.

Rather than dividing linguistic insight into competing schools, the Trio model absorbs, synthesizes, and extends their contributions. Contrast becomes recursion; rule becomes resonance; context becomes ontological activation.

Through comparative analysis and recursive modeling, this article explores how the Law of the Trio reframes syntax not as structural engineering but as semantic geometry—where every utterance embodies a triadic mapping of experience. Whether encoding perception, simulating intention, or shaping reality, the sentence becomes the recursive particle through which existence is symbolized and communicated.

“Language is not the shadow of thought—it is the shape of existence, refracted through symbol.”

2. Generative Grammar and Ontological Grammar

Building upon the comparative synthesis outlined in Table 2, we now examine each foundational linguistic paradigm in direct conversation with the Law of the Trio—highlighting not only points of divergence but opportunities for structural reimagining.

The emergence of generative grammar in the mid-20th century, led by Noam Chomsky, marked a profound shift in the study of language. In Syntactic Structures (1957) and Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), Chomsky proposed that the ability to produce and understand language arises from an innate cognitive module—a Universal Grammar (UG)—hardwired into the human mind. This faculty enables speakers to generate infinite expressions from finite sets of rules, transforming abstract deep structures into surface-level utterances through transformational operations.

Generative grammar placed syntax at the center of linguistic theory, largely divorced from meaning and usage. According to Chomsky (1980), grammaticality is determined not by semantic coherence but by conformity to rule systems. Hence, “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” is syntactically well-formed despite being semantically nonsensical. This model situates linguistic competence within a modular cognitive system, with language acquisition unfolding through rule internalization rather than environmental induction (Chomsky, 1975).

While this formalism enriched syntactic theory and inspired models such as Government and Binding and the Minimalist Program (Chomsky, 1995), it also faced critique for marginalizing meaning, embodiment, and communicative function. Scholars like Tomasello (2003) and Newmeyer (2003) argued that usage, interaction, and cognitive generalization play significant roles in language development and structure—suggesting that syntax may not be as autonomous or innate as once believed.

The

Law of the Trio enters this discourse as a complementary yet divergent framework. Rather than treating language as the output of an innate rule system, the Trio proposes that sentence formation reflects a semantic invocation of existence. A sentence arises when an entity is paired with its state or behavior, encoded through language, conceptualized by thought, or instantiated in reality. This foundational act is modeled by:

Unlike Chomsky’s conception of syntax as a formal computational system, the Trio treats syntax as the semantic geometry of being. It encodes how things are, how they change, and how they relate. This shifts the generative process from transformational derivation to ontological expression.

Let us consider Chomsky’s (1995) minimalist analysis of a simple declarative sentence:

“John ate the apple.”

In generative grammar, this sentence reflects hierarchical phrase structure (e.g., TP, VP, NP) derived through Merge operations. Its acceptability hinges on rule adherence.

In the Trio framework, the sentence is interpreted as:

This structure is not merely acceptable—it is necessary. The sentence reflects a triadic event encoded across modalities:

In reality: a physical action by an entity

In thought: a cognitive simulation of the event

In language: symbolic representation through syntactic assembly

This reconceptualization echoes Jackendoff’s Foundations of Language (2002), which argued that syntax interacts intimately with semantics and conceptual structure, rather than operating in isolation. The Trio builds on this insight, proposing that sentence formation emerges from entity-state/behavior coupling, not rule application.

Modifiers such as adjectives, adverbs, and clauses are treated in the Trio not as syntactic adjuncts, but as recursive layers of semantic enrichment. For example:

“The hungry child quickly devoured the ripe apple under the tree.”

Here we identify:

EM12: hungry (modifier of entity)

VM12: quickly (modifier of behavior)

EM12.2: ripe (modifier of object)

EM14.2: Prepositional phrase modifying the object (apple) — adds locational detail about the apple itself

Each element adds ontological depth, layering perception, state, and context in symbolic form. This parallels Fillmore’s frame semantics, where meaning is structured by domains of experience.

Furthermore, the Law of the Trio is language-neutral. While generative grammar often presumes an English-centric architecture, the Trio’s semantic function applies across typologies. Consider the Japanese sentence:

彼は林檎を食べました。(“He ate an apple.”)

The semantic pairing—entity (彼), behavior (食べました), object (林檎)—remains constant. The surface grammar differs; the semantic cell persists.

In summary, while generative grammar formalized the combinatorial logic of syntax, the Law of the Trio reframes sentence structure as a semantic anatomy of reality. It treats grammatical formation not as recursive computation, but as recursive representation—of entities in transformation, modified across perceptual and symbolic dimensions.

“Generative grammar models possibility. The Trio models presence.”

3. Structuralism and the Semantic Network

Continuing our comparative dialogue, we now turn to structuralism—a paradigm that revolutionized linguistic theory through relational logic, yet often severed meaning from ontological grounding. The Law of the Trio reframes this inheritance by restoring reference, identity, and semantic recursion across modalities.

Structuralism, as developed by Ferdinand de Saussure in his Course in General Linguistics (1916), laid the foundation for viewing language as a system of relational signs. In Saussure’s model, each linguistic unit—termed a sign—is comprised of two components: the signifier (sound/image) and the signified (concept). Crucially, meaning is not derived from referential connection to the external world, but from opposition within the system—signs gain value through what they are not, rather than through what they directly represent.

This insight gave rise to the doctrine of differential meaning, where language is understood as a closed, self-referential network. Saussure’s synchronic focus treated linguistic structure as a static system, abstracted from diachronic change and experiential grounding. Subsequent structuralists such as Roman Jakobson extended the model to functional dimensions, identifying axes of selection and combination (Jakobson, 1960), while Claude Lévi-Strauss applied linguistic principles to myth, culture, and anthropology.

However, the structuralist model introduced a significant philosophical rupture: it severed meaning from reference. Words ceased to reflect reality and became markers within an internal system. This decontextualization laid the groundwork for poststructural critiques—most notably in Derrida’s Of Grammatology (1976), which questioned the stability of signs and highlighted the perpetual deferral of meaning through chains of difference (différance).

The Law of the Trio enters this legacy with a transformative proposition. While affirming the relational nature of meaning, it reinstates reference and reality as essential structural elements. Meaning is not exclusively relational within language—it arises from triadic interaction among:

Entity: a noun or ontological anchor

State/Behavior: a verb or dynamic transformation

Modality: the mode of expression—reality, thought, or language

This model retains structuralism’s systemic elegance but expands its scope from intra-linguistic contrast to intermodal resonance. Language, in this view, is a conduit for encoding semantic events—not merely differentiating signs.

Consider the noun “tree.” In structuralism, tree is defined by its difference from bush, vine, rock, etc. In the Trio model, tree is understood through its entity profile—its ontological attributes (height, rootedness, transformation), cognitive interpretation (shade, symbol, metaphor), and linguistic articulation (tree, árbol, 木, etc.). Meaning arises from alignment across modalities—not systemic contrast alone.

Let us examine the sentence:

“The tree shelters the birds.”

From a structuralist perspective, meaning is generated through the placement and contrast of words within a syntactic chain. In the Law of the Trio, however, the sentence becomes a semantic node encoding a real-world event:

This configuration echoes Fillmore’s frame semantics, where meaning is shaped by relational roles and contextual background. The Trio deepens this model by proposing a universal recursive notation—EMji and VMji—to model modifier hierarchy and semantic layering, independent of linguistic typology.

Rather than a grid of signs in opposition, the Trio conceives language as a semantic network shaped by ontological interaction. Each sentence acts as a symbolic particle in this network, linking cognitive models to real or imagined states of the world.

Metaphorically visualized, structuralism presents a matrix of contrast. The Trio, by contrast, offers a spiral of recursion, with the core entity-behavior pair generating semantic layers that expand outward. Meaning is not static—it evolves through context, perception, and symbolic transformation.

Cross-linguistic validation reinforces this alignment. Consider the Japanese sentence:

木は鳥を守っている。(“The tree is protecting the birds.”)

While syntactically distinct from English, its semantic function remains constant:

Entity: 木 (ki, tree)

Behavior: 守っている (mamotte iru, is protecting)

Object Entity: 鳥 (tori, birds)

The same ontological structure persists—language encodes a reality-state interaction, filtered through cognition and symbol.

By restoring reference, perception, and event structure to the study of meaning, the Law of the Trio resolves a key limitation of classical structuralism: the absence of existential grounding. It proposes that meaning emerges not just from contrast within language, but from semantic resonance across reality, thought, and symbolic form.

In sum, structuralism laid the groundwork for understanding linguistic systems as relational architectures. The Law of the Trio builds upon this legacy—transforming static contrast into dynamic interaction, and positioning the sentence as a semantic cell capable of transmitting not only differential meaning, but structured echoes of being.

“Structuralism defined meaning by what it wasn’t. The Trio defines meaning by how it is—where reality, thought, and symbol converge.”

4. Functionalism and the Ontological Function of Language

Where generative grammar abstracts language into formal rules and structuralism fragments meaning into oppositional signs, functionalism re-centers language around communicative purpose. Yet despite its pragmatic elegance, functionalism often treats language as reactive rather than existential. The Law of the Trio shifts this posture—modeling grammar not as adaptation, but as invocation of being.

Functionalist theories of language emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century as a corrective to the abstract formalism of generative grammar. Rather than focusing on innate syntactic modules or autonomous grammatical systems, functionalism placed use and context at the center of linguistic analysis. Scholars such as Michael Halliday (1978, 1994), Simon Dik (1989), and Talmy Givón (1979, 1995) argued that linguistic structures evolve through—and are shaped by—the communicative needs of speakers in specific discourse environments.

Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) reframed grammar as a meaning-making resource, not a static rulebook. In this model, clauses serve three simultaneous functions: ideational (representing experience), interpersonal (enacting social roles), and textual (organizing messages coherently) (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). Grammar becomes inherently multifunctional—adaptable to the speaker’s purpose and the hearer’s interpretive frame.

Similarly, Givón (1979) emphasized that form follows function: syntactic structures crystallize from patterns of use and variation over time. He argued that discourse shapes grammar and that linguistic complexity often reflects cognitive and pragmatic motivations.

While these insights reinvigorated the study of usage and intention, functionalism frequently describes language in reactive terms—an instrument for conveying information, negotiating roles, or responding to context. Meaning, in this view, is emergent and situational rather than formally structured.

The Law of the Trio reorients this premise. While acknowledging communication as one output of linguistic expression, it posits that the primary function of language is ontological. Sentences are not merely tools of interaction—they are symbolic enactments of reality across modalities.

Every sentence begins with a triadic coupling:

Entity (noun or subject of existence)

State/Behavior (verb or transformation)

Recursive modifiers, layered hierarchically

Unlike functionalism’s focus on discourse pragmatics, the Trio models grammar as a recursive scaffold for expressing the conditions and transformations of being. Linguistic categories become semantic coordinates—anchoring perception, cognition, and reality within symbolic form.

Let us compare analyses of the sentence:

“The student carefully revised her essay.”

A functionalist account might examine:

Intentionality: carefully indicates volition

Information structure: topic-focus dynamics

Interpersonal tone: implications in context

In the Trio model, however, this becomes a semantic invocation:

Each component reflects not just usage—but structured presence. The action is encoded as a recursive semantic unit—expressing cognition, agency, and transformation.

The Law of the Trio deepens functionalist insights into modifier hierarchy, particularly those explored by Hopper & Thompson (1984), who examined transitivity and discourse prominence. While functionalist approaches parse modifiers for pragmatic effects, the Trio treats them as recursive expressions of ontological depth. For example:

“The exhausted hiker slowly descended the icy slope despite the wind.”

Mapped triadically:

Entity: hiker (the embodied experiencer)

EM12: exhausted (modifier of entity)

Behavior: descended

VM12: slowly (modifier of behavior)

Object: the icy slope

VM14: Prepositional phrase expressing a challenging condition

These modifiers form not a surface function, but a semantic anatomy of experience—nested representations of physical state, perceptual quality, spatial orientation, and resistance.

Cross-linguistic consistency supports this modeling. Consider:

彼は風の中でゆっくりと氷の斜面を下った。(“He slowly descended the icy slope in the wind.”)

Despite typological variation, semantic structure persists:

The Trio allows modality-neutral semantic alignment—supporting universal expression without syntactic equivalence. This significantly advances multilingual modeling and intercultural understanding.

Pedagogically, the Trio enriches functionalist curricula by shifting focus from communicative outcome to ontological encoding. Learners are guided not to replicate forms, but to observe events, identify entity-state /behavior couplings, and recursively encode detail. This reality-based approach aligns with Content-Based Instruction (Doughty & Long, 2003), while adding structural clarity.

Computationally, the Trio provides new scaffolding for semantic parsing. Functionalist models inform natural discourse flow; the Trio complements them with EMji/VMji stratification—supporting semantic role labeling and recursive depth modeling in NLP systems.

In sum, while functionalism elevated purpose, interaction, and usage, the Law of the Trio illuminates structure as existence. Sentences become symbolic expressions of being—not adaptations to context, but geometries of transformation.

“Functionalism sees language as adaptation. The Trio sees it as invocation—of existence, through structure, in symbol.”

5. Cognitive Linguistics and Triadic Cognition

Building on the experiential turn introduced by functionalism, cognitive linguistics deepens the inquiry into how language reflects thought. Yet while it anchors meaning in embodiment and metaphor, it often treats reality as peripheral—a backdrop rather than a modality of expression. The Law of the Trio reframes this relationship, modeling cognition not as interface but as structural recursion.

Cognitive linguistics emerged in the late twentieth century as a decisive counterpoint to the modular formalism of generative grammar. Spearheaded by theorists such as George Lakoff, Ronald Langacker, Leonard Talmy, and Gilles Fauconnier, it proposed that language is not an isolated mental faculty, but deeply embedded in general cognition—shaped by perception, embodied experience, and conceptual abstraction (Lakoff, 1987; Langacker, 1987; Talmy, 2000).

Central to this paradigm is the idea that linguistic meaning arises through conceptual mapping. Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (1980) demonstrated how abstract thought is structured by metaphorical projections rooted in embodied domains: “time is motion,” “affection is warmth,” “communication is transfer.” Talmy extended this through force dynamics, showing how language reflects basic cognitive construals of interaction and energy. Meanwhile, Langacker’s cognitive grammar models syntax as symbolic structure—arguing that grammatical constructions are pairings of form and meaning shaped by attentional salience and event structure.

While cognitive linguistics restored meaning to linguistic analysis, its emphasis remains largely on the interface between thought and language. Reality, though referenced, is often treated as a passive canvas rather than as a structurally expressive domain. As Zlatev (2005) observes, linguistic models must account for both internal conceptual structure and external embodied intersubjectivity.

The Law of the Trio addresses this limitation by positioning reality, thought, and language as structurally homologous and ontologically co-equal. Each modality enacts the same semantic function: the recursive pairing of an entity with its state or behavior.

Where Modality may be:

Reality: physical entities and transformations

Thought: cognitive representations and simulation

Language: symbolic expression through structured syntax

This recursive model extends Langacker’s notion of construal into a triadic circuit. Meaning is no longer a projection of embodied experience alone—it becomes a structural interaction where:

This echoes Fauconnier and Turner’s Conceptual Blending theory (2002), where mental spaces fuse structure and experience into emergent meaning. The Trio formalizes this fusion through semantic recursion.

Consider the sentence:

“The tired woman carefully folded the wrinkled blanket before the guests arrived.”

A cognitive linguistic reading might note:

Image schemas: containment, force, motion

Conceptual mappings: fatigue, care, sequence

Attention profiles: agent-focused construal

Trio mapping translates this into recursive notation:

The result is not just metaphor—but semantic anatomy. Each element encodes presence, transformation, and relation through layered recursion.

The Law of the Trio deepens cognitive grammar’s event-based modeling by introducing modifier stratification. EMji and VMji notation allows researchers and educators to map semantic complexity in formal terms—enabling quantifiable analysis in working memory studies, sentence processing, and narrative cognition.

In acquisition contexts, the Trio complements usage-based models (Tomasello, 2003) by offering a generative scaffold. Rather than mimicking syntactic templates, learners build sentences by observing events, identifying entity-state couplings, and recursively enriching detail. Language becomes an encoding of experience—not just a construction of use.

Consider:

“A man buys fruit at a market.”

Trio modeling yields:

Entity: man

Behavior: buys

Object Entity: fruit

VM14: at the market

Further details unfold recursively, supporting clarity, retention, and cross-linguistic alignment.

In cognitive science, the Trio supports symbolic modeling of perception and memory. EMji and VMji notation provides parameters for tracking depth, specificity, and modifier density—advancing event representation and semantic load analysis.

Ultimately, the Law of the Trio reframes cognition itself—not as neural mapping alone, but as ontological recursion. Language ceases to be metaphor alone—it becomes symbolic transduction, where reality flows into thought, and thought into structured symbol.

“Cognitive linguistics traced meaning to the body. The Trio traces meaning through the body—into reality, symbol, and back again.”

6. The Sentence as Semantic DNA

Across linguistic paradigms, the sentence has been defined as a propositional unit, a combinatorial structure, or a functional construction. The Law of the Trio reframes it as something more elemental: a symbolic cell of existence, recursively encoding identity, transformation, and relation through semantic structure.

In most linguistic theories, a sentence is defined as a minimal grammatical unit composed of hierarchically organized phrases that convey meaning. In generative grammar, sentence structure is derived from syntactic rules and transformations operating on formal categories (Chomsky, 1965; Radford, 2004). In cognitive grammar, sentences are symbolic assemblies of conceptual content paired with linguistic form (Langacker, 1987). Construction Grammar treats sentences as stored pairings of form and function (Goldberg, 2006). Frame Semantics links sentences to experiential domains and conceptual templates (Fillmore, 1982).

While each paradigm illuminates a structural or functional facet, few treat the sentence as a recursive representation of ontological logic. The Law of the Trio intervenes with a paradigm-shifting proposition: that every sentence is not merely linguistic, but existential—a semantic particle mirroring the triadic modalities of reality, thought, and language.

Here, Modality represents any of the three structurally equivalent domains—language, thought, or reality. The sentence, under this framing, becomes an expression of that function, modeling the conditions under which something exists, acts, or transforms.

The metaphor of semantic DNA captures this recursive architecture. Just as biological DNA encodes organismal identity through nucleotide sequences, the sentence encodes semantic identity through entity-state-modifier cascades. Modifiers—traditionally treated as syntactic adjuncts—are reconceived here as recursive layers of meaning, revealing depth, perception, temporality, and relational nuance.

To systematize this recursion, the Trio introduces:

EMji: Entity Modifiers, where i is the modifier type and j the recursion depth

VMji: Verb Modifiers, parallel in structure

This notation builds on linguistic traditions of constituency and dependency, but shifts their interpretive focus from grammatical structure to semantic modeling.

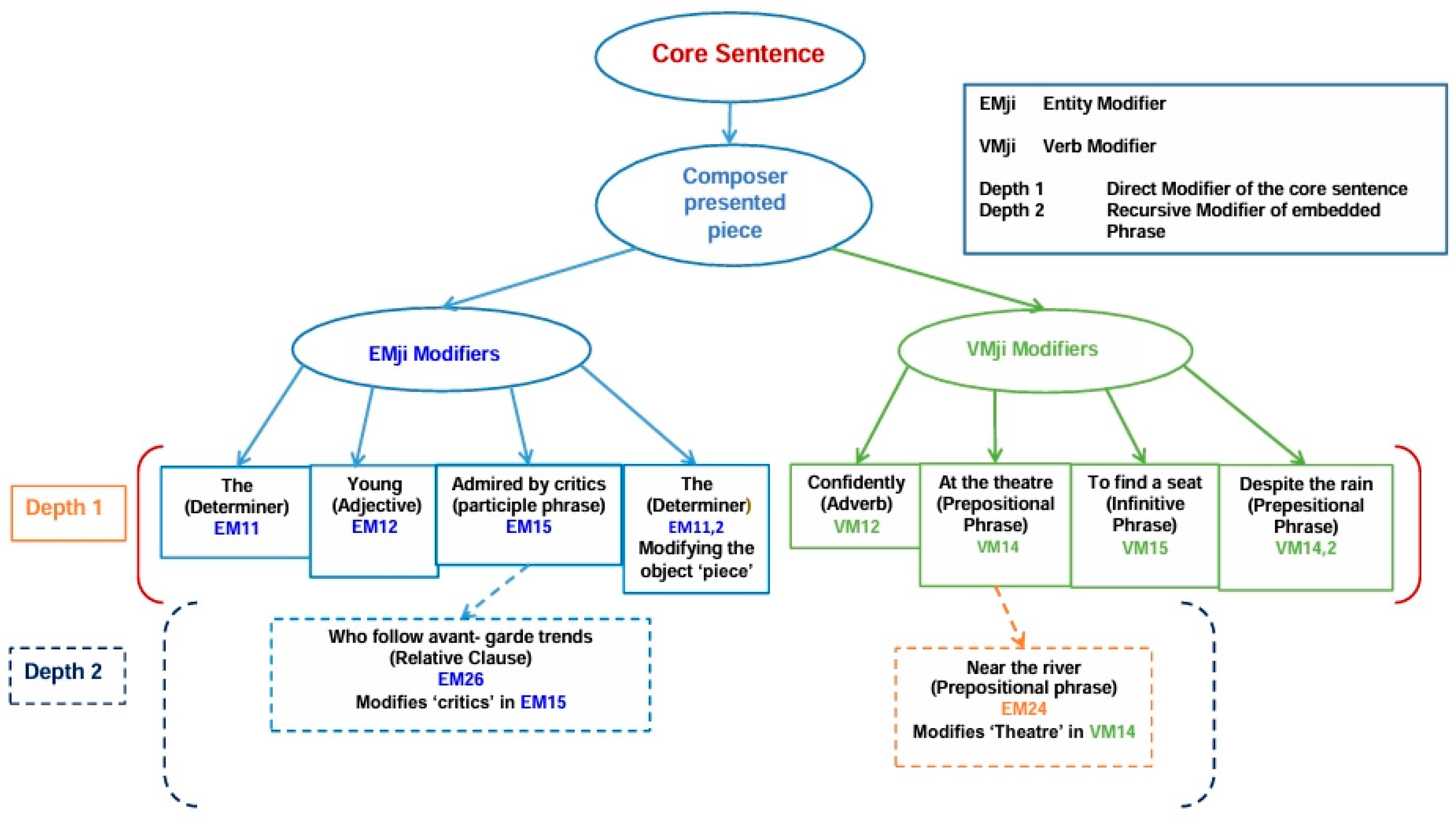

Figure 2 offers a recursive modifier mapping of the sentence:

"The young composer admired by critics who follow avant-garde trends confidently presented the piece at the theatre near the river to find a seat despite the rain."

Figure 2.

Recursive Semantic Architecture of EMji and VMji Modifiers.

Figure 2.

Recursive Semantic Architecture of EMji and VMji Modifiers.

Traditional grammars interpret this sentence via hierarchical phrase structure rules, yielding major constituents like:

NP (Noun Phrase): The young composer admired by critics who follow avant-garde trends

VP (Verb Phrase): Confidently presented the piece…

PP (Prepositional Phrases): At the theatre, Near the river, Despite the rain

While such parsing yields surface-level syntactic groupings, it obscures the

ontological layering underlying human interpretation—where entities and actions are recursively defined by semantic modifiers.

Figure 2 replaces constituent trees with

Trio-based recursion, distinguishing:

EMji Modifiers: Entity-layer enrichments—determiners, adjectives, and clauses that specify “who” or “what” in existential terms.

VMji Modifiers: Verb-layer modifiers—adverbials, locatives, and purpose phrases that explain “how,” “why,” and “under what conditions.”

For instance:

Who follow avant-garde trends (EM26) modifies critics nested inside EM15 (admired by critics), recursively defining the social prestige of the composer.

Despite the rain (VM14,2) overlays a concessive real-world constraint on the act of presentation—adding experiential realism often lost in phrase-based parsing.

This comparison foregrounds the Trio’s cognitive orientation: modifiers are not mere syntactic appendages but ontological amplifiers. They deepen our understanding of agency, behavior, and circumstance across recursive layers—a structure that mirrors how learners intuitively build meaning.

By contrasting phrase structure with EMji–VMji recursion,

Figure 2 exemplifies how Trio theory reframes sentence interpretation—not as a mechanical parsing exercise, but as a semantic model of reality-in-language.

This diagram models a complex sentence using the Law of the Trio’s recursive framework. Entity and behavior domains are recursively enriched through modifiers: adjectives, prepositional phrases, infinitive phrases, and nested relative clauses. Each modifier reflects layered semantic depth-from core meaning to circumstantial elaboration-mapping language as a structural mirror of cognition and reality.

This layered structure becomes a semantic scaffold, revealing the symbolic anatomy of the event—agent, action, object, and context—recursively articulated.

Langacker’s (2000) view that grammatical structures reflect symbolic meaning finds strong resonance here. The Trio extends this principle by showing how meaning is recursively encoded through modifier stratification—not as adjuncts, but as ontological threads.

Fillmore’s frame semantics is deepened in the Trio’s recursive approach. Frames are not merely evoked—they are dynamically constructed across semantic layers. Every EMji and VMji modifier constitutes a dimension of conceptual and experiential specificity.

Cross-linguistic alignment further validates this architecture. In Korean:

피곤한 아이가 천천히 무거운 문을 폭풍 속에서 열었다。 (“The tired child slowly opened the heavy door during the storm.”)

Mapped semantically:

Despite surface syntactic variation, semantic recursion persists. The Trio preserves ontological constancy across linguistic expression—a notion more robust than generative grammar’s universal syntax.

Pedagogically, the Trio provides a new paradigm. In language education, students construct sentences by observing real events, identifying entities and actions, and enriching meaning through recursive modifiers. This reality-driven approach enhances retention and supports transfer across languages and modalities.

In computational systems, EMji/VMji notation supports semantic parsing in AI models—offering a formal method for tracking modifier depth, event structure, and referential relationships. This supplements statistical language models with ontologically grounded semantic scaffolding.

Philosophically, the sentence becomes not a surface utterance but a symbolic microcosm of reality. Each element enacts presence, transformation, and relational depth. Grammar evolves into existential geometry—a structured invocation of being.

“Every sentence contains the blueprint of an event. Its nouns are identities, its verbs are transformations, and its modifiers are the threads of reality woven into symbol.”

7. Applications Beyond Linguistics

The Law of the Trio, while rooted in linguistic structure, transcends the boundaries of language theory. By modeling reality, thought, and language as parallel modalities governed by the same ontological logic—recursive pairing of entity and behavior—it becomes a versatile framework for representing, teaching, generating, and transferring meaning across diverse domains.

7.1. Education: Semantic Mapping as Curriculum

Traditional language instruction often detaches grammar from meaning. Students learn rules abstracted from reality, leading to mechanical output and superficial retention. The Law of the Trio offers a meaning-first alternative, reinforcing principles of Content-Based and Task-Based Learning (Doughty & Long, 2003) while introducing semantic modeling as pedagogical practice.

Learners observe real-world events

Identify entities and transformations

Encode those events recursively using EMji and VMji scaffolding

This approach complements Tomasello’s usage-based acquisition model (2003), but goes further—transforming sentences into structured reflections of experience. Grammar becomes lived logic, not rule memorization.

7.2. Intercultural Communication: Modality Convergence

Cross-linguistic exchange often fails when form-based translation overrides semantic alignment. Intercultural pragmatics (Kecskes, 2014) focuses on context negotiation, yet the Trio offers a deeper architecture: modality-neutral semantic invariance.

Across languages:

The entity-state structure remains

Modifier recursion adjusts for context

Meaning survives grammatical variation

This allows for true conceptual equivalence across cultures—supporting Kramsch’s vision (2009) of intercultural competence rooted in symbolic depth, not surface politeness.

7.3. Second-Language Acquisition: Reality-Based Encoding

Transfer errors in L2 learning often stem from native syntactic habits. Traditional instruction builds form first, meaning second. The Trio framework reverses this:

Learners begin with perceptual input

Identify the semantic event

Encode it directly in the target language

This process mirrors VanPatten’s Processing Instruction (2015), but adds recursive semantic scaffolding. The learner doesn’t translate—they model reality anew, structurally and recursively.

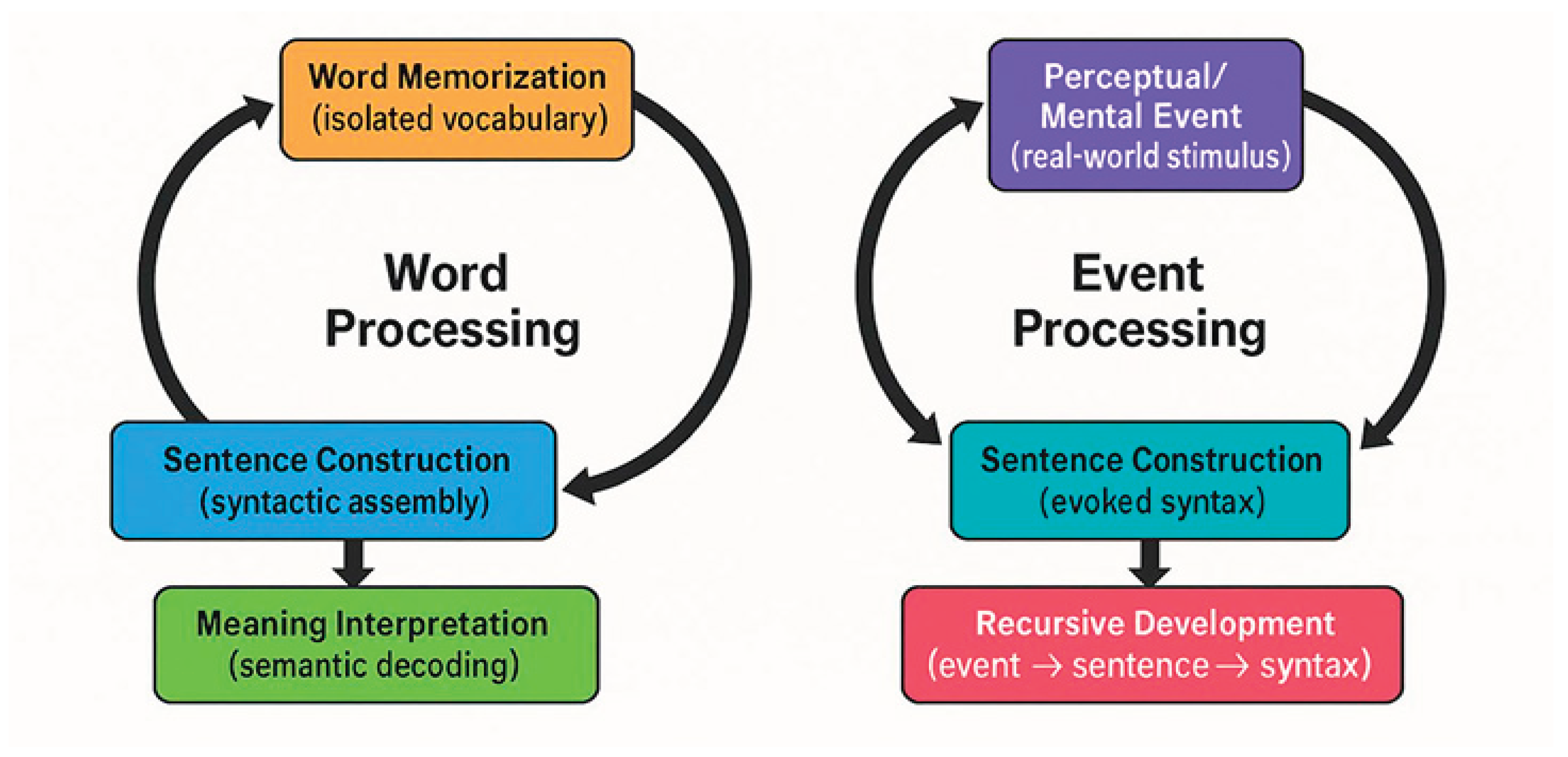

Figure 3.

Recursive Cycles of Language Processing: Traditional Word-Based vs. Event-Based Acquisition Models.

Figure 3.

Recursive Cycles of Language Processing: Traditional Word-Based vs. Event-Based Acquisition Models.

This dual-cycle diagram compares two distinct approaches to second language acquisition. The Traditional Word-Based Model (left) follows a linear, surface-level sequence: learners begin by memorizing isolated vocabulary, then assemble sentences, and ultimately attempt to decode meaning. This path often results in cognitive overload and semantic disengagement. In contrast, the Event-Based Model (right), grounded in the Law of the Trio, begins with a perceptual or conceptual event that evokes communicative intent. Language emerges recursively: sentences are constructed in response to real-world stimuli, and vocabulary is shaped by the syntactic and semantic demands of the event. This triadic loop fosters deeper retention, semantic coherence, and learner-centered fluency.

7.4. Artificial Intelligence & NLP: Semantic Architecture for Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) excel in fluency, but often lack structural understanding. Transformer architectures (Vaswani et al., 2017) rely on statistical sequence modeling—not ontological clarity. The Trio provides a formal scaffold:

EMji/VMji layers enable depth-aware parsing

Entity-state modeling supports event extraction

Sentences become semantic cells, not token sequences

This advances work in semantic role labeling (Gildea & Jurafsky, 2002) and enhances interpretability in AI systems. Symbolic cognition becomes structurally possible—not just predicted.

7.5. Cognitive Science: Modeling Semantic Perception

Cognitive studies of memory, attention, and event representation require models that map complexity transparently. The Trio’s recursive modifier system provides:

It aligns with Kintsch & van Dijk’s macrostructure theory (1978) and Barsalou’s perceptual symbol systems (1999), translating experimental cognition into recursive semantic form.

7.6. Philosophical Inquiry: Language as Structural Ontology

The Trio reframes philosophical debates on meaning and reference. Frege’s sense-reference distinction becomes structural enactment. Wittgenstein’s view that “meaning is use” gains ontological extension: use becomes recursive expression of being.

Peirce’s triadic semiotics—representamen, object, interpretant—finds formal elaboration here. Trio recursion is not just interpretive—it models semantic structure across modalities.

7.7. Universal Digital Language: Toward Semantic Interoperability

Projects like Meta’s No Language Left Behind (2022) aim for translation universality via pattern recognition. The Law of the Trio suggests a new architecture:

Semantic invariance across modalities

Recursive modifier stratification

Ontologically grounded syntax usable across systems

It echoes Leibniz’s characteristica universalis—but grounds symbol in reality. A digital language built on the Trio would unify expression and perception, serving AI, education, diplomacy, and research alike.

In sum, the Law of the Trio reshapes disciplines beyond linguistics. It transforms language learning into semantic modeling, intercultural dialogue into conceptual alignment, AI into symbolic cognition, and philosophy into recursive articulation of being. Meaning is no longer inferred—it is constructed.

“Language doesn’t describe the world—it recreates it—one triadic sentence at a time.”

8. Conclusion—Toward Ontological Linguistics

Across theoretical paradigms—from generative computation to embodied cognition—linguistics has illuminated facets of language’s complexity. Yet fragmentation persists. Syntax is treated as rule, semantics as use, and meaning as context—rarely as a recursive expression of being. The Law of the Trio brings these strands together, reframing linguistics as structural ontology.

This inquiry has traced the contours of foundational linguistic thought—from the syntactic architectures of generative grammar (Chomsky, 1965; Radford, 2004), through the oppositional logic of structuralism (Saussure, 1916), the discourse-functional frameworks of Halliday and Givón, and the experiential grounding of cognitive linguistics (Lakoff, Langacker, Talmy). Each paradigm enriches our understanding—yet each isolates language within its own silo.

The Law of the Trio does not negate these insights—it synthesizes them. By modeling reality, thought, and language as structurally parallel modalities, it reveals syntax not as code, but as existential geometry—recursive invocation of identity, transformation, and relation.

This triadic structure is expressed through:

Modality=f(Entity, State or Behavior)

And rendered formally through:

EMji/VMji notation: recursive modifier hierarchy

Semantic particle modeling: sentences as symbolic cells

Cross-modal alignment: meaning preserved across reality, cognition, and symbol

Peirce’s triadic semiotics finds evolved expression here: not merely interpretant chains, but ontological recursion. Wittgenstein’s insight that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world” becomes structural—language does not only limit, it constructs. Frege’s distinction between sense and reference is translated into recursive coupling—each modifier an enrichment of presence.

Practically, the Trio reshapes:

Language learning → into semantic modeling

Computational parsing → into event scaffolding

Philosophical inquiry → into structural ontology

Intercultural translation → into recursive equivalence

Digital language design → into symbolic transparency

Its implications extend across pedagogy, AI, cognitive science, and cross-linguistic semantics. It offers not just a lens—but a language for modeling existence.

Ultimately, the Law of the Trio invites a new linguistic science—one capable of articulating meaning not as artifact or adaptation, but as recursive enactment of being.

“A sentence is not built—it becomes. Not through rules, but through resonance. Not through function, but through form-as-existence.”

Author Contributions

The author independently conceived, developed, and refined the theoretical framework of the Law of the Trio. All writing, comparative analysis, semantic modeling, and manuscript structuring were undertaken by the author. AI tools were engaged dialogically throughout the revision process to support editorial clarity, formatting decisions, and structural consistency.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research. All work was conducted independently by the author.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable. The study is theoretical and does not involve human participants or ethical review procedures.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. The manuscript does not contain personal data, images, or identifiable material requiring consent.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the recursive editorial partnership with AI-based dialogue systems in shaping the clarity, structure, and depth of the manuscript over multiple revision phases. Special thanks to the broader academic community whose engagement with Unlocking Language and early versions of this article helped inform critical refinements.

Data Availability

Not applicable. No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing financial or non-financial interests related to the content or dissemination of this work.

References

- Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4), 577–660.

- Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1975). Reflections on Language. Pantheon Books.

- Chomsky, N. (1980). Rules and Representations. Columbia University Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2013). What is language and why does it matter. Lecture presented at the Linguistic Society of America Summer Institute, University of Michigan.

- Dik, S. C. (1989). The Theory of Functional Grammar. Foris Publications.

- Doughty, C. J., & Long, M. H. (2003). The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Blackwell Publishing.

- Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. Basic Books.

- Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (Ed.), Linguistics in the Morning Calm (pp. 111–137). Hanshin Publishing.

- Gildea, D., & Jurafsky, D. (2002). Automatic labeling of semantic roles. Computational Linguistics, 28(3), 245–288. [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. (1979). On Understanding Grammar. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. (1995). Functionalism and Grammar. John Benjamins.

- Goldberg, A. E. (2006). Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford University Press.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2014). Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Harris, R. A. (1993). The Linguistics Wars. Oxford University Press.

- Hopper, P. J., & Thompson, S. A. (1984). The discourse basis for lexical categories in universal grammar. Language, 60(4), 703–752.

- Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, R. (1960). Linguistics and poetics. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in Language (pp. 350–377). MIT Press.

- Johnson, M. (1987). The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. University of Chicago Press.

- Kecskes, I. (2014). Intercultural Pragmatics. Oxford University Press.

- Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85(5), 363–394.

- Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind. University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

- Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Stanford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R. W. (2000). Grammar and Conceptualization. Mouton de Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books. [CrossRef]

-

No Language Left Behind.

- Pinker, S. (1996). The Language Instinct. Harper Collins. [CrossRef]

- Saussure, F. de. (1916). Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye.

- Speaks, J. (2024). Theories of Meaning. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter Edition).

- Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Harvard University Press.

- VanPatten, B. (2015). While We're on the Topic: BVP on Language, Acquisition, and Classroom Practice. ACTFL.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing.

- Zlatev, J. (2005). What’s in a schema? Bodily mimesis and the grounding of language. In B. Hampe (Ed.), From Perception to Meaning: Image Schemas in Cognitive Linguistics (pp. 313–342). Mouton de Gruyter.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).