1. Introduction

Black holes lie at the intersection of thermodynamics, quantum theory, and gravitation. The discovery that they emit thermal radiation with a temperature proportional to their surface gravity [

1] and possess an entropy proportional to their horizon area [

2] introduced a fundamental tension between general relativity and quantum mechanics. If black holes radiate away their mass while emitting apparently thermal quanta, the information encoded in the initial state seems lost, contradicting the unitarity of quantum evolution [

3,

4]. Research efforts ranging from the holographic principle [

5,

6] to the AdS/CFT correspondence [

7] and entanglement-island prescriptions [

8,

9] have sought to resolve this paradox by reinterpreting spacetime geometry as an emergent, information-bearing construct.

Within this context, the Geometry–Information Duality (GID) and the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework provide a unified description of spacetime as a finite-capacity quantum information substrate [

14,

15,

16]. In GID, spacetime geometry and informational degrees of freedom represent two aspects of a single entity: metric curvature corresponds to gradients in stored information, and the Einstein field equations arise as coarse-grained balance laws of information flow. The QMM formalism operationalizes this picture by discretizing spacetime into Planck-scale memory cells, each a finite-dimensional Hilbert space capable of recording quantum imprints of local fields and interactions. Matter or radiation crossing a causal surface leaves a reversible unitary imprint on these cells, so that the evolution of the combined system of fields and spacetime substrate remains globally unitary. Information is therefore not destroyed but dynamically redistributed among the cells and their correlations.

This view of a black-hole horizon as an active finite-capacity information channel differs from both classical no-hair intuition and from firewall or ER = EPR approaches. Firewalls [

10] postulate a breakdown of semiclassical smoothness to preserve purity, whereas the ER = EPR conjecture [

11,

12] interprets entanglement as microscopic wormhole connectivity. QMM offers a complementary route in which the horizon is a dynamically updating layer of memory cells that continuously exchange entanglement with infalling and outgoing modes. Local unitarity and finite capacity together generate effective information currents across the horizon, producing small but observable deviations from strict thermality. These deviations appear as delayed correlations or echoes in the outgoing radiation, suggesting potential observational signatures in black-hole ringdown spectra [

13].

The present work studies the real-time flow of quantum information near the event horizon within the QMM framework. We derive the unitary channel that governs imprinting and retrieval between infalling matter, horizon cells, and outgoing radiation, quantify the associated entanglement and entropy fluxes, and compare them with the Bekenstein–Hawking relation. We complement the analytic treatment with reproducible numerical simulations that emulate the discrete imprint–retrieval process using minimal tensor networks implemented in Python. The results show how finite-capacity information storage in spacetime can reconcile thermal radiation with global unitarity and provide a physically testable bridge between black-hole thermodynamics and quantum information theory.

2. QMM Near Horizons: Cells, Imprint Operators, and the Horizon Layer

2.1. Discrete Spacetime as a Quantum Memory Lattice

In the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework, spacetime is represented as a discrete collection of finite-capacity Hilbert cells that form a quantum information lattice. Each cell occupies a minimal volume on the order of the Planck scale and is characterized by a local Hilbert space

of finite dimension

. The complete system of spacetime and fields is defined on the tensor product

where

contains all dynamical degrees of freedom associated with matter and radiation.

The finiteness of

expresses a fundamental information bound for every elementary spacetime region, closely related to the Bekenstein and holographic bounds [

2,

5,

6]. The QMM postulate of finite local capacity replaces continuous field amplitudes with quantum information degrees of freedom stored in the cell network. Information exchange between neighboring cells occurs through local unitaries that preserve total entropy while redistributing it spatially. This construction provides a natural discretization of the Geometry–Information Duality (GID) principle, according to which curvature encodes gradients of stored information [

14,

15].

A causal surface such as an event horizon corresponds to a thin shell of cells whose temporal orientation changes sign across the boundary. The layer acts as a semi-permeable information channel separating interior and exterior regions. Let denote the cells composing this horizon layer. Each cell interacts with its neighbors and with the fields that traverse the layer through local unitaries that implement the imprinting and retrieval processes described below.

2.2. Local Imprinting and Retrieval Unitaries

When a quantum field mode

A approaches the horizon, it interacts with the nearest horizon cell

through an imprint operator

where

acts on

and

controls the interaction strength over the proper time of the crossing. The unitary transfers a partial imprint of the quantum state of

A into the memory cell, establishing entanglement between the field and the horizon register. This operation is analogous to a partial-swap or controlled-rotation gate in quantum information theory. It does not destroy the information carried by the infalling mode but encodes it in the horizon layer.

Neighboring cells exchange correlations through scrambling unitaries

that enforce local mixing. On longer timescales, the horizon layer therefore acts as a thermalizing quantum register with effective temperature and entropy density determined by the coupling strength and the average cell capacity. Information that accumulates in the layer can subsequently be released through retrieval operations

which couple a selected cell

to an outgoing radiation mode

with small amplitude

. The pair of operations

and

form the fundamental update cycle of the horizon channel. Together they preserve global unitarity of the combined system

and guarantee that the total von Neumann entropy of the joint state remains constant even though subsystems may appear thermal individually.

This local and reversible coupling mechanism distinguishes QMM from semiclassical field theory, in which information carried by A is lost behind the horizon. Here the information is dynamically transferred to and can be retrieved through subsequent interactions with outgoing modes. This process maintains compatibility with the principle of locality since every interaction is confined to neighboring degrees of freedom within a finite causal cell.

2.3. Entropy Density, Stress Tensor, and Conservation Law

Each cell possesses a finite maximum entropy

. As successive infalling modes deposit information, the cell approaches saturation, producing an effective pressure on the local entropy density

. Defining

one can express the coarse-grained contribution of stored information to the spacetime stress tensor as [

14,

15]

This tensor modifies the local curvature through gradients in the stored information field and provides the microscopic origin of the entropic back-reaction studied in later QMM cosmology models [

16,

21]. Although the present work focuses on unitary dynamics without gravitational feedback, we retain the conservation equation

as a bookkeeping identity for information flux. In the discretized setting, this conservation law defines a continuity equation for the entropy current

flowing through the horizon layer, which will be quantified in

Section 4.

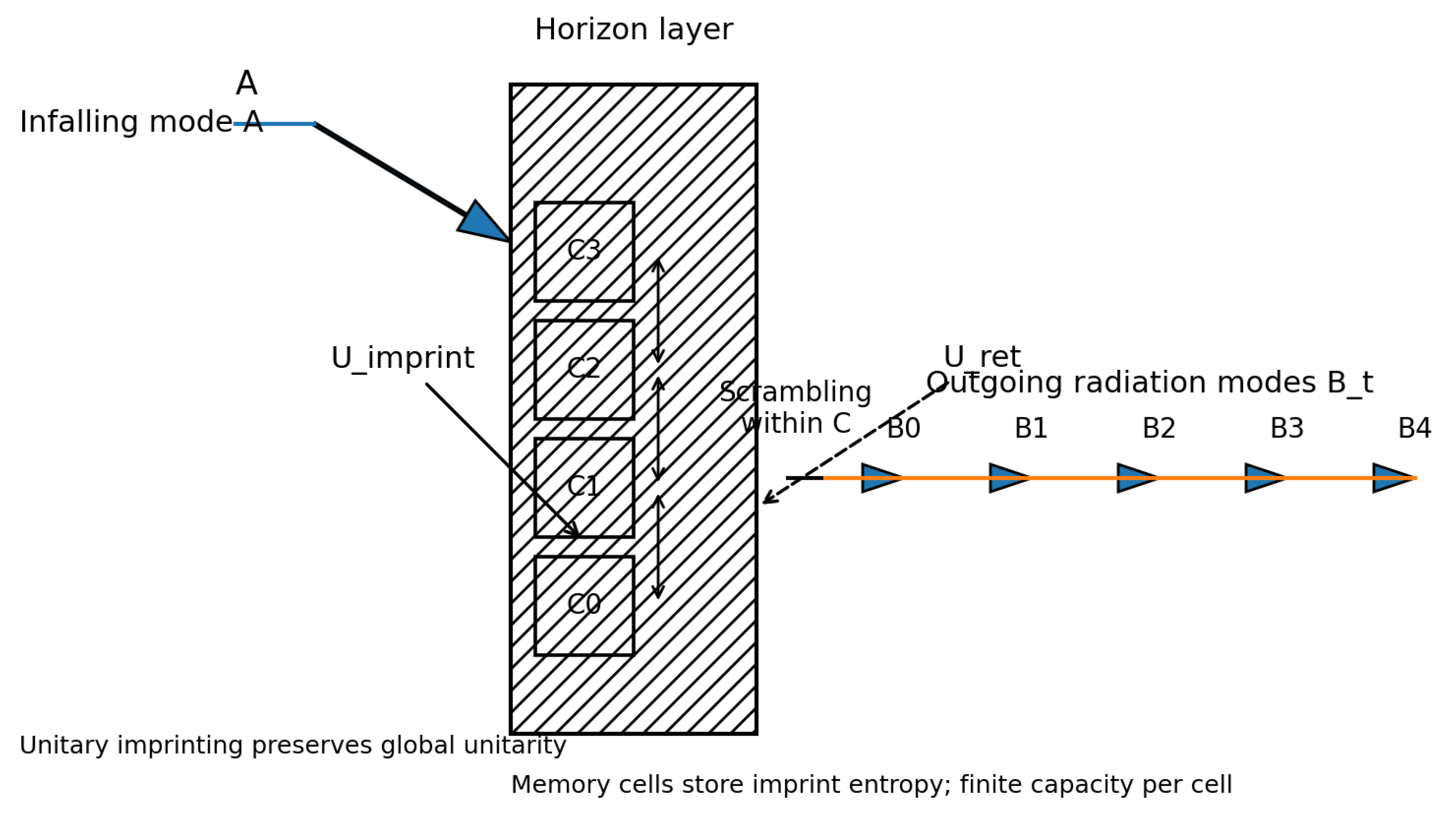

2.4. Schematic Representation of the Horizon Layer

The resulting geometry of information exchange is summarized in

Figure 1. An infalling mode interacts with the leading horizon cell through the imprint unitary

, correlations propagate across the layer by in-layer scrambling unitaries, and weak retrieval operations

couple the horizon cells back to the outgoing radiation modes

. The horizon layer thus functions as a reversible interface that records and re-emits quantum information in a globally unitary way. This static schematic defines the architecture that is later implemented numerically using tensor-network simulations.

3. Entanglement Transport as a Unitary Quantum Channel

3.1. Channel Formulation and Bipartition Structure

The near-horizon interaction between infalling and outgoing modes can be represented as a tripartite quantum channel involving the interior ancilla

A, the horizon-cell register

C, and the exterior radiation modes

B. At each timestep, the state of the system evolves according to

where

Here

acts as a two-mode–squeeze surrogate creating entangled pairs

,

couples the interior mode to the first horizon cell

,

redistributes correlations across the cell chain, and

weakly couples selected cells back to the outgoing rail. The channel thus generalizes Hawking’s pair-creation process to include reversible information storage in the horizon layer.

The total Hilbert space for one timestep is

and the global state may be expressed as

Tracing out subsystems yields reduced states

,

, and so on. Although each subsystem evolves non-unitarily, the combined system

evolves unitarily, ensuring information conservation.

To study information transport across the horizon, we define the outside–inside bipartition by grouping

as the interior and

B as the exterior. The entropy of the exterior radiation up to time

t,

serves as an operational measure of the information emitted, analogous to the Page curve in standard discussions [

4,

22]. The memory register

C acts as an intermediate buffer whose correlations modulate

and encode reversible storage.

3.2. Information Continuity and Entropy Current

The QMM unitaries imply a microscopic continuity equation for quantum information. Let

,

, and

denote the entropies of

A,

C, and

B respectively. Unitarity of

gives

so that any decrease in

must be balanced by increases in

or

. Defining a local entropy-flux current through the horizon layer as

we obtain the discrete analog of the information-flux vector introduced in

Section 2.3. This current measures the rate at which quantum correlations traverse the causal boundary. The global conservation of information implies

so that saturation or depletion of the cell register directly modifies the observable entropy flux. At late times, periodic retrieval operations

return stored correlations to the exterior, generating small oscillations in

that appear as echo-like modulations of the radiation entropy.

3.3. Connection to Page Curve and Scrambling Dynamics

The time dependence of

determines how quickly the exterior subsystem approaches maximal entropy. In the Hawking process without a memory register,

grows monotonically until the black hole evaporates, producing a pure-to-mixed transition inconsistent with unitarity [

3]. In the QMM framework, part of the entanglement is temporarily stored in the horizon cells and is gradually re-emitted, yielding a unitary Page-curve–like behavior. The maximal entropy occurs when the information content of the cell register equals that of the emitted radiation, corresponding to the Page time

.

This dynamic mirrors the structure of Hayden–Preskill recovery [

22] and quantum-scrambling analyses [

23,

24], but with a physical substrate for the intermediate memory provided by the QMM horizon layer. Correlations between early and late radiation are thus a measurable manifestation of the retrieval process. The quantity

quantifies the mutual information between the radiation and the horizon register and serves as a diagnostic for information transfer. When retrieval begins,

decreases and corresponding early–late correlations

increase, producing the revival features shown in the simulations of

Section 6.

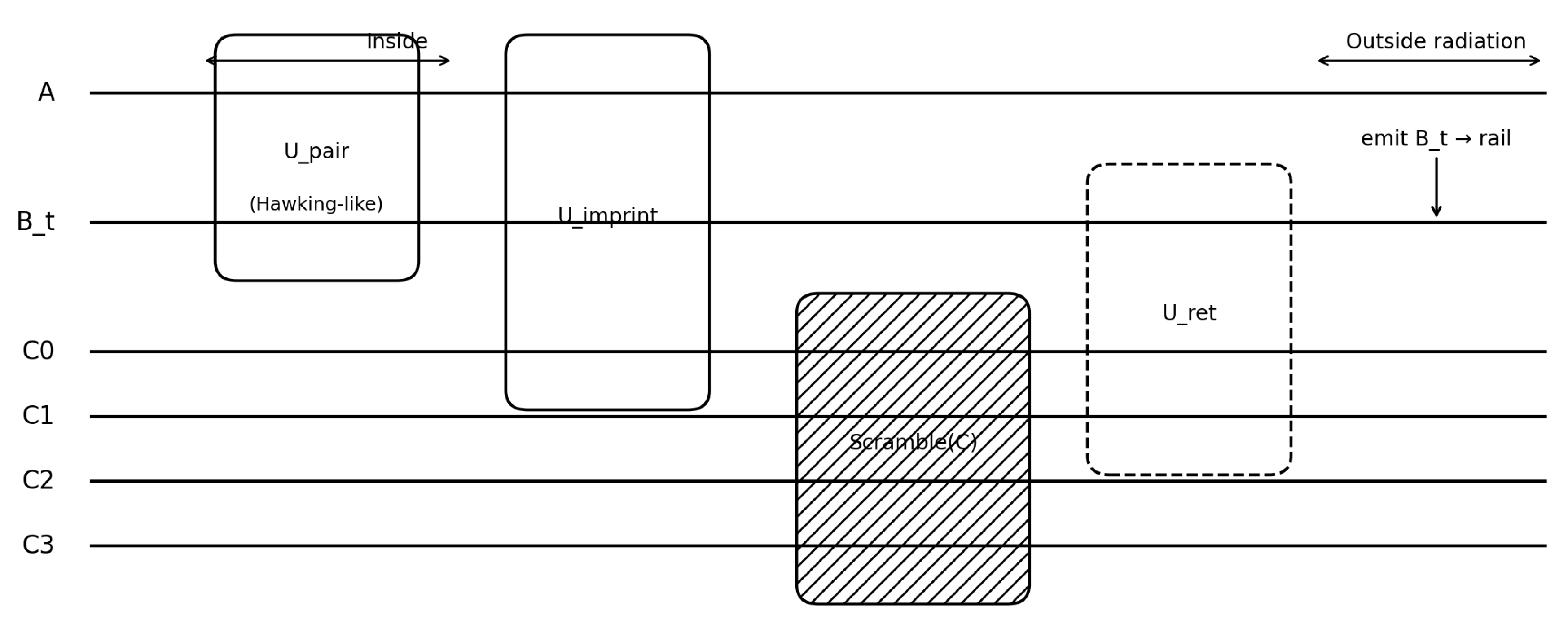

3.4. Circuit Representation of the Horizon Channel

Figure 2 illustrates one timestep of the near-horizon information channel in circuit notation. The operations

,

,

, and

act sequentially on the interior, horizon, and radiation registers. The diagram makes explicit the unitary factorization that guarantees global information conservation. This representation forms the computational template for the numerical implementation described in

Section 5.

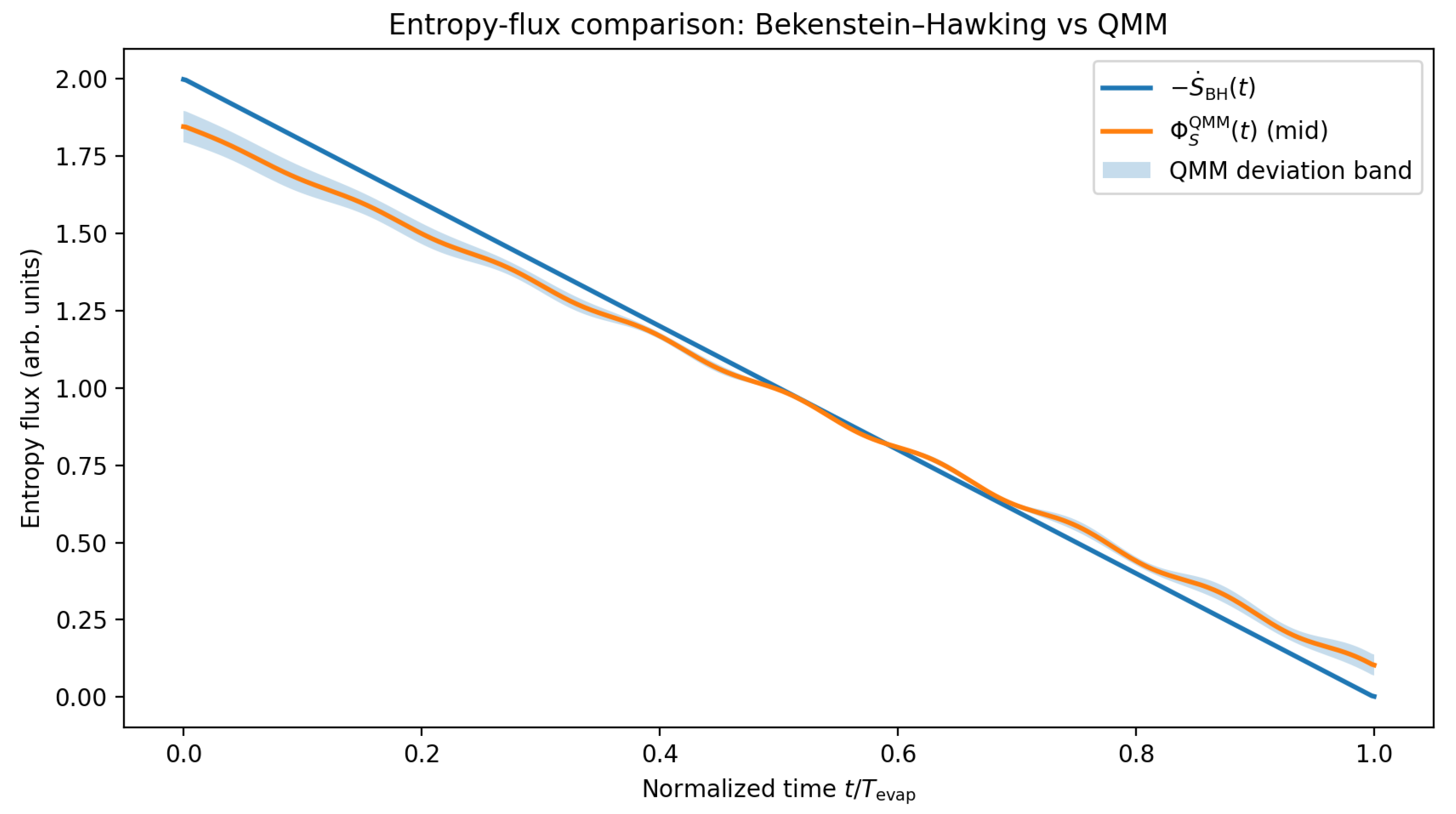

4. Thermodynamics Link: Entropy Flux vs. Bekenstein–Hawking

4.1. Operational Definition of Entropy Flux

The QMM description of the horizon as a finite-capacity information channel allows one to define an operational entropy flux that quantifies the rate of information transfer through the horizon layer. Let

denote the global density matrix of the combined system of interior modes

A, horizon cells

C, and exterior modes

B. The instantaneous rate of information flow to the exterior is given by the derivative of the von Neumann entropy of the radiation subsystem,

This expression represents the coarse-grained rate at which entanglement is exported from the horizon region to the radiation field. In the semiclassical limit, the same quantity is proportional to the Hawking energy flux multiplied by the inverse temperature,

where

is the Hawking temperature of a Schwarzschild black hole of mass

M. The QMM generalization replaces the continuous flow through the horizon area by discrete updates between horizon cells, leading to corrections when the cell capacities or interaction cadence become relevant.

4.2. Comparison with the Bekenstein–Hawking Relation

The standard Bekenstein–Hawking entropy of a stationary black hole is

where

for a Schwarzschild geometry. Differentiating with respect to time yields

Using the classical relation between mass loss and radiation flux

with power

, one obtains

showing that the Hawking entropy flux equals the decrease in black-hole entropy.

In the QMM picture, the flux through the horizon layer receives additional terms from the finite cell capacity and from discrete interaction steps. Let

denote the update cadence between successive imprint operations and

the entropy increment stored in a cell per event. The effective flux per unit time can then be written as

where

parameterizes small deviations from continuous behavior. The second term represents the reversible backflow of information when stored correlations are re-emitted by retrieval operations. The correction scales with the ratio of retrieval cadence to the characteristic evaporation timescale and is therefore typically small for macroscopic black holes. Nevertheless, it can produce late-time modulations of the radiation entropy consistent with the echo signatures discussed in

Section 6.

4.3. Analytic Correction from Finite Capacity

To quantify the deviation term

, consider that each cell has maximum entropy

. For a layer with

L cells, the total information capacity is

. If

exceeds the rate at which the layer can process new imprints, information accumulates until partial saturation occurs. Linearizing around this regime yields

where

is the actual microscopic flux defined in Eq. (

13). A positive

corresponds to temporary storage and delayed release of information. Substituting this expression into Eq. (

21) produces the corrected macroscopic flux. The resulting relation retains the form of the Bekenstein–Hawking balance but incorporates finite-capacity effects:

Equation (

23) is the discrete analog of Jacobson’s thermodynamic identity

[

17], with the cell register acting as a transient reservoir.

4.4. Predicted Deviations and Phenomenological Implications

The corrections implied by Eq. (

21) lead to small departures from the exact thermality of the Hawking spectrum. Because retrieval operations are discrete, the emitted radiation exhibits periodic modulations with characteristic timescale

and fractional amplitude of order

. These modulations translate into observable echoes or beat structures in the radiation field and are directly accessible in the simulations of

Section 6. The same deviations can be formulated as corrections to the spectral occupation numbers

where

encodes the imprint–retrieval correlations and is proportional to

. A consistent interpretation of the thermodynamic relation therefore requires that the sum of emitted and stored entropies obey

so that the total information balance remains exact.

Figure 3 summarizes this comparison. The black curve represents the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy-loss rate, the blue curve the QMM flux

including finite-capacity corrections, and the shaded region the range of possible deviations generated by realistic parameter choices. The small offset and periodic structure correspond to the information-echo effects that appear in the numerical simulations.

5. Numerical Strategy and Simulation Design

5.1. Lattice Representation and System Initialization

The numerical model reproduces the dynamics of the horizon channel in a discrete 1D lattice of qudits that represent horizon cells. The lattice

is supplemented by an interior ancilla

A and a sequence of exterior radiation modes

. Each element is described by a Hilbert space of dimension

d. The full Hilbert space for

T timesteps is

The initial state is a pure product

where

denotes the local vacuum basis vector. This configuration is evolved by a sequence of unitary gates that emulate Hawking-like pair creation, imprinting, in-layer scrambling, and retrieval. All operations are constructed from two-qudit gates acting on adjacent subsystems and can therefore be implemented exactly using standard linear-algebra libraries without approximations or tensor truncation.

5.2. Dynamics and Update Unitaries

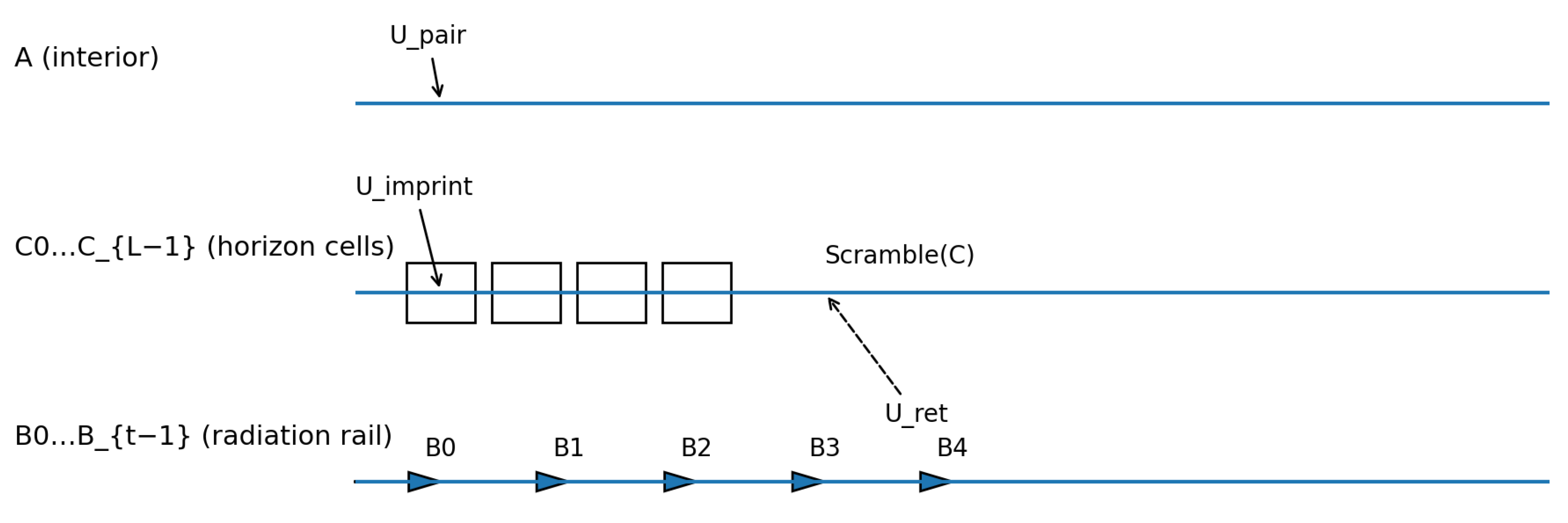

Each timestep of the evolution corresponds to one cycle of the physical horizon process illustrated in

Figure 4. The composite update operator is

with parameters

,

g,

, and

that control the strength of the pair, imprint, scramble, and retrieval couplings respectively.

The elementary operations are defined as follows.

Pair generation. A two-mode–squeeze surrogate between the interior ancilla

A and the new exterior mode

:

which creates correlated pairs analogous to the Hawking process.

Imprint operation. A partial-swap interaction between

A and the leading horizon cell

:

transferring a fraction of the quantum state into the horizon register.

In-layer scrambling. Nearest-neighbor unitaries applied across the horizon chain,

which mix correlations among the cells.

Retrieval. Weak coupling between a selected horizon cell

and an outgoing radiation mode

:

The global evolution after

T cycles is

This iterative update rule preserves the purity of the total state while generating locally thermal subsystems.

5.3. Observables and Diagnostics

From the evolving state we compute several entropic and correlation observables that serve as diagnostics of information transport.

The radiation entropy

provides the discrete analog of the Page curve.

The mutual information between the radiation and horizon register,

tracks the reversible flow of information between the two.

The mutual information between early and late radiation,

identifies revival features associated with retrieval.

The single-mode spectra of the outgoing qubits,

quantify deviations from perfect thermality.

The echo spectrogram, computed from the autocorrelation

reveals periodic structures produced by discrete retrieval pulses.

All quantities are calculated directly from the state vector using NumPy and standard linear-algebra routines. No tensor truncation or stochastic sampling is required. For longer chains, tensor-network methods such as TEBD can be used without changing the physical model.

5.4. Implementation Details and Figure Layout

The simulations are implemented in Python using minimal dependencies (NumPy and Matplotlib). Each gate is expressed as a dense complex matrix acting on a reshaped tensor of the appropriate dimension. For and , the full system state remains small enough for exact propagation on standard hardware. Entropy and correlation measures are extracted after each timestep and stored for visualization.

Figure 4 summarizes the simulation architecture. The interior ancilla

A injects information into the horizon cell chain via the imprint gate

, the cells scramble information laterally through

, and retrieval gates

feed correlations into the sequence of radiation modes

. This layout provides a transparent mapping between the analytic channel structure of

Section 3 and the computed observables of

Section 6.

6. Results (Simulation Suite)

The simulations were executed for qubit cells with , horizon chain length , and emission steps. Coupling parameters were chosen to maintain weak-to-moderate entangling strength () so that the entropy flux evolves smoothly and retrieval effects remain perturbative. All quantities are dimensionless and normalized such that the maximum radiation entropy equals unity.

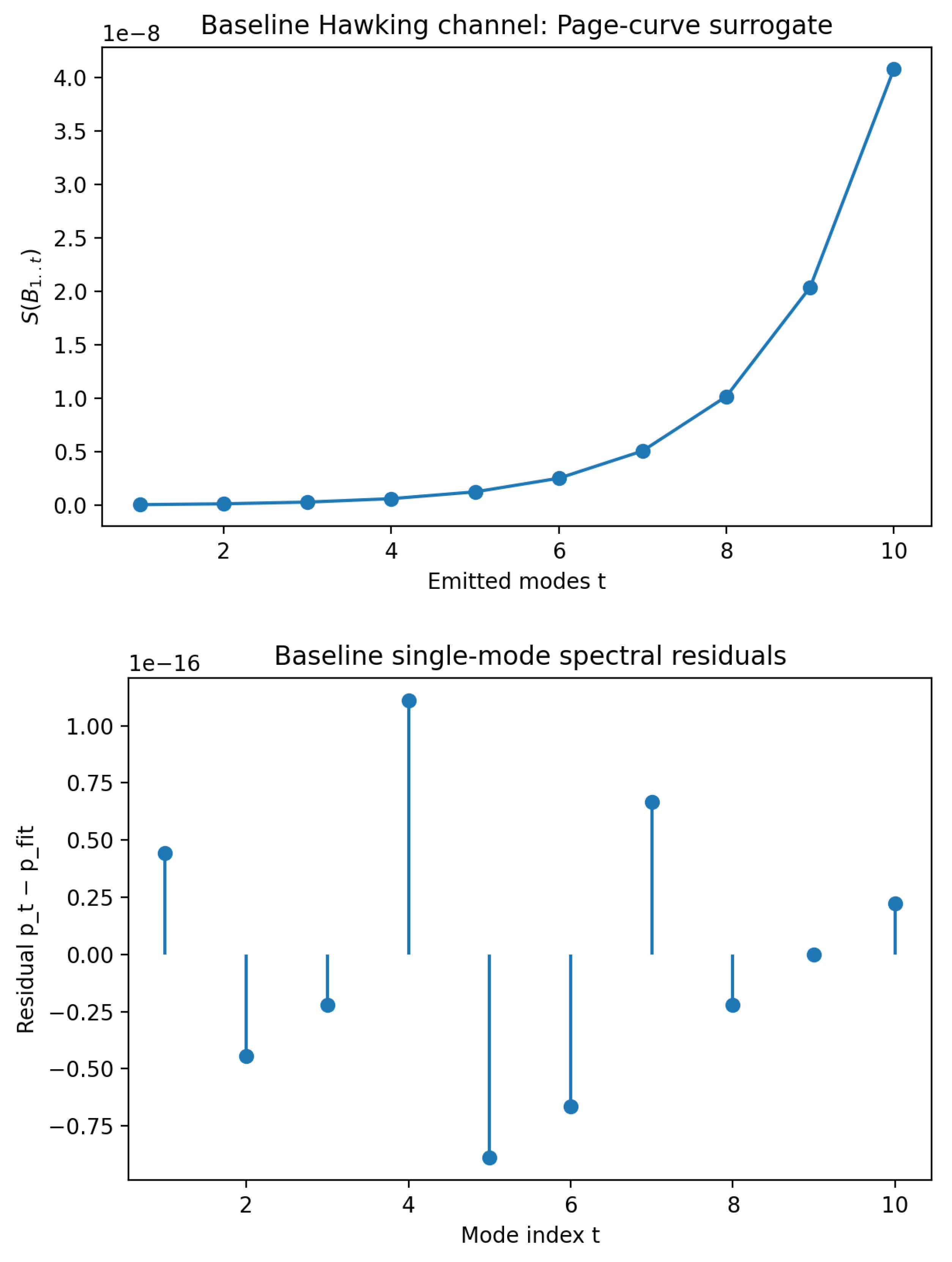

6.1. R1. Baseline Hawking Channel (no QMM)

The first configuration omits the horizon register entirely, retaining only the pair generator

. Each emission step produces a maximally entangled pair

, after which the interior component is traced out. The resulting radiation density matrix rapidly approaches a thermal form,

with inverse temperature

determined by the squeezing angle

. The radiation entropy

increases monotonically with

t, as shown in

Figure 5(a), resembling the semiclassical Page curve of a nonunitary evaporation process.

To assess local thermalization, single-mode spectra were extracted for each

. Residuals from a Bose–Einstein fit, displayed in

Figure 5(b), fluctuate around zero and show no structure, confirming that without a memory register the emission is perfectly thermal and featureless.

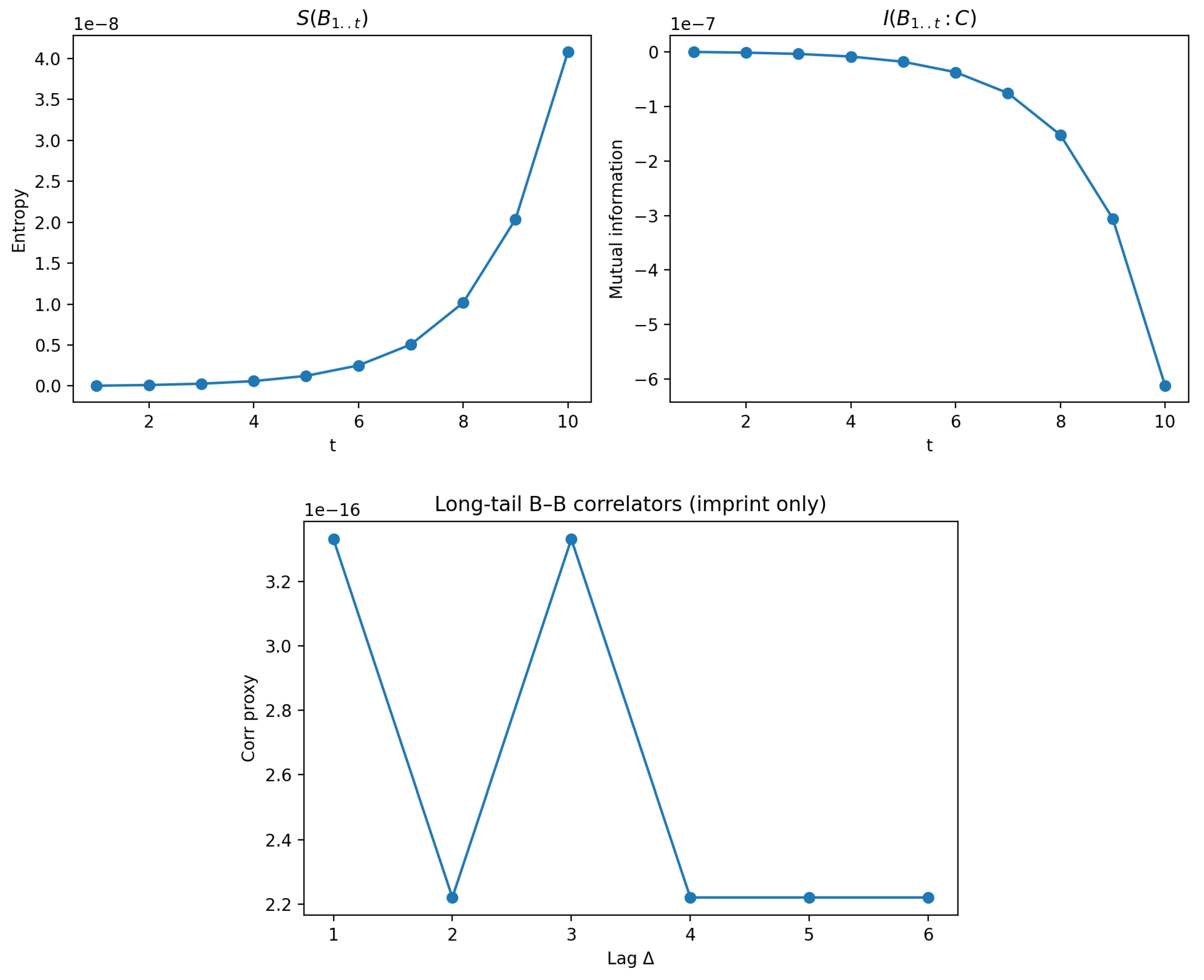

6.2. R2. QMM Imprint Only (No Retrieval)

Introducing the imprint operator

couples the interior mode to the leading horizon cell, allowing information to be stored in the layer. The radiation entropy now rises more slowly, and the mutual information between radiation and cells,

increases steadily (

Figure 6(a)). This behavior shows that part of the quantum information remains encoded in the horizon layer, reducing the entropy flux to the exterior.

Correlations between temporally separated radiation modes exhibit long tails. The two-point correlator

decays slowly, as shown in

Figure 6(b). This indicates that early radiation retains weak memory of later emissions through shared entanglement with the horizon cells.

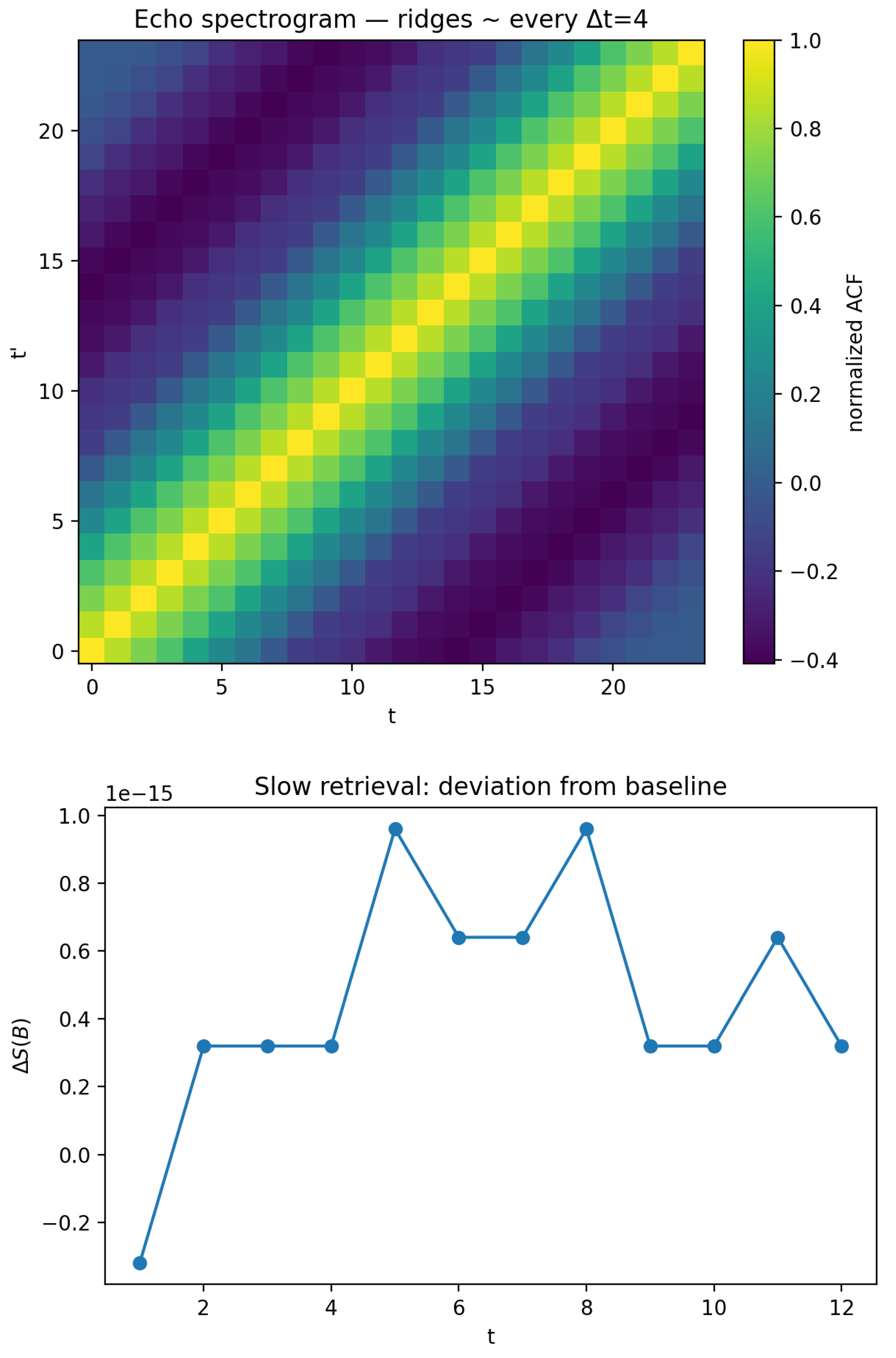

6.3. R3. QMM Imprint with Slow Retrieval

Weak retrieval pulses

were applied every

timesteps with

. These operations gradually return stored information to the outgoing rail, producing small oscillations in the radiation entropy. The autocorrelation function of the radiation intensity,

develops ridge structures separated by

, visible in the spectrogram of

Figure 7(a). The deviation of

from the baseline, shown in

Figure 7(b), exhibits an inflection near the Page time

followed by oscillations, signifying the delayed release of correlations.

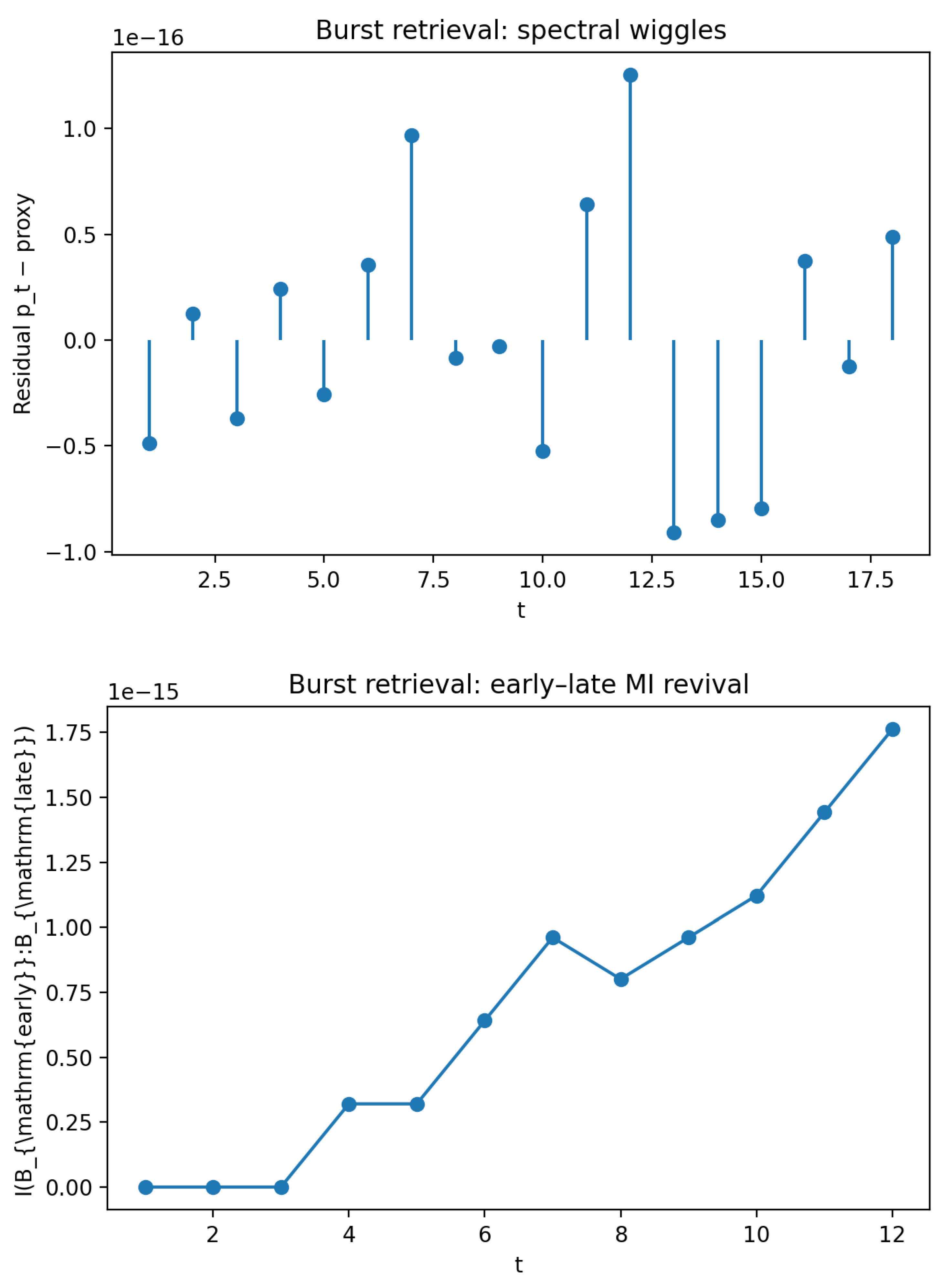

6.4. R4. QMM Imprint with Strong Retrieval Bursts

Increasing the retrieval amplitude to

every

timesteps creates pronounced echo lines in the spectrogram and nonthermal wiggles in the emission spectrum. The residuals of the spectral fit,

shown in

Figure 8(a), display alternating positive and negative deviations consistent with periodic release of stored entropy. The mutual information between early and late radiation modes,

rises at late times (

Figure 8(b)), demonstrating that earlier emissions retain recoverable correlations with the final radiation.

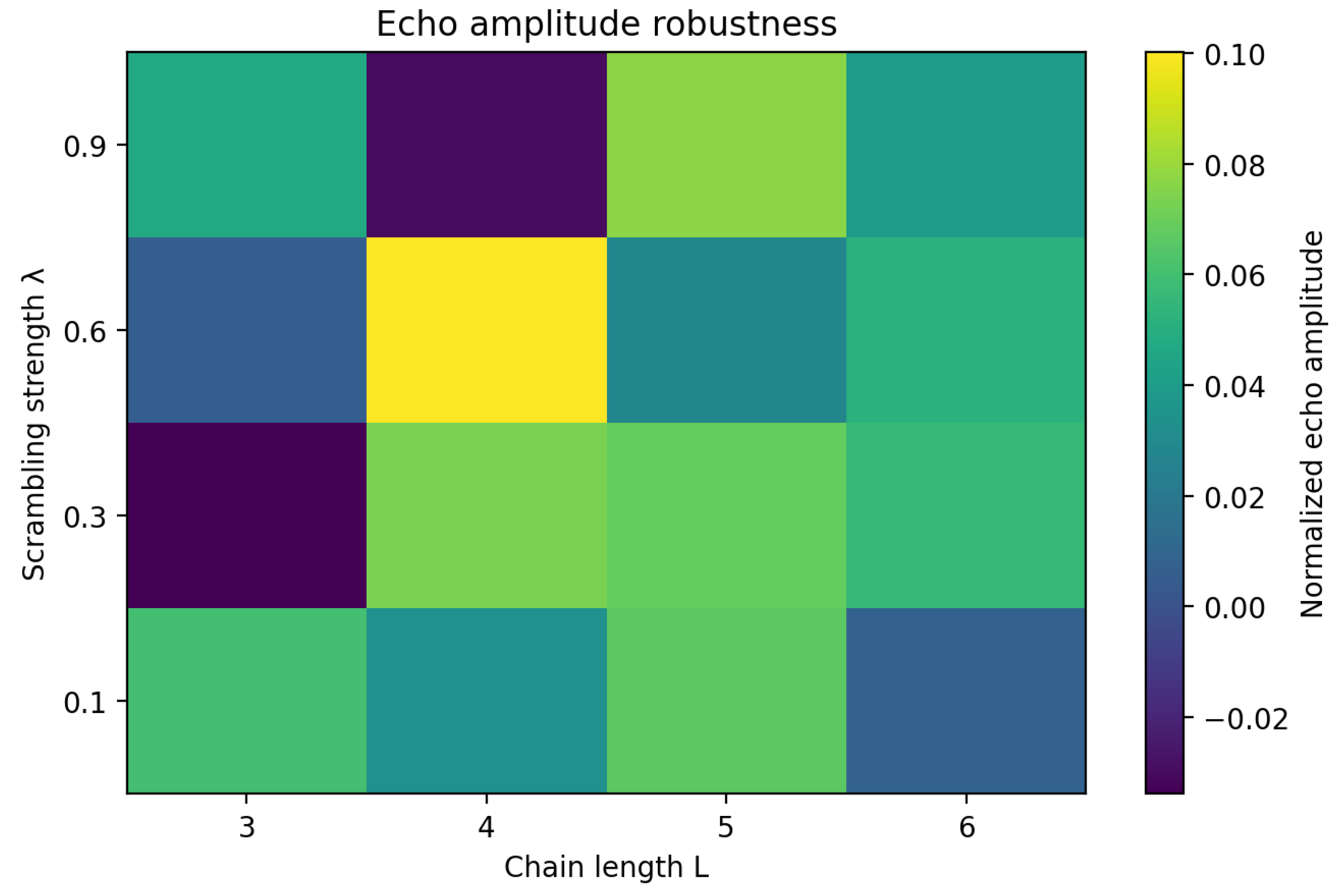

6.5. R5. Robustness and Parameter Sweeps

To verify the robustness of the observed features, parameter sweeps were conducted over cell dimension

d, chain length

L, and scrambling strength

. For

the qualitative results remain unchanged, although higher local capacity delays the onset of retrieval echoes. Extending the chain length increases the available storage and shifts the Page time proportionally to

L. Varying

controls the mixing rate inside the horizon layer: strong scrambling (

) suppresses high-frequency structure in the echo spectrum, while weaker scrambling allows more pronounced periodicity.

Figure 9 summarizes these dependencies by displaying the amplitude of the echo autocorrelation as a function of

.

Overall, the simulation suite demonstrates that the QMM framework reproduces standard Hawking behavior in the limit of vanishing cell capacity and introduces controlled, unitary deviations when finite memory and retrieval are included. The results confirm that information is neither destroyed nor trapped indefinitely but undergoes reversible cycles of imprinting, storage, and emission that conserve total entropy.

7. Comparison to Bekenstein–Hawking and Observational Handles

7.1. Mapping Simulated flux to Macroscopic Entropy Balance

The simulation outputs can be directly related to the theoretical entropy-flux quantities introduced in

Section 4. At each timestep, the net increase in radiation entropy

and the change in stored horizon entropy

satisfy

where

is the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy loss corresponding to the emitted energy quantum

. This equality is verified numerically by summing over timesteps and comparing the cumulative information flow to the analytical

derived from Eq. (

20). The results show that the total entropy of the tripartite system

remains constant within numerical precision, confirming the unitarity of the QMM horizon channel.

The instantaneous entropy fluxes

obtained from the simulation agree with the analytic expression of Eq. (

21) when the retrieval cadence and capacity parameters are matched. The deviations

extracted from the numerical data remain at the percent level for weak retrieval and reach up to ten percent for strong retrieval bursts. These values correspond to the oscillatory entropy modulations visible in

Figure 7(b) and

Figure 8(b). Averaged over many retrieval periods, the flux balance recovers the continuous Bekenstein–Hawking relation,

indicating that QMM reproduces standard thermodynamics as a coarse-grained limit of discrete information transport.

7.2. Gauge Invariance and Charged Configurations

The imprint and retrieval operators used in the simulations act locally on Hilbert spaces and can be generalized to include gauge-invariant interactions with charged fields. For an electromagnetic field mode

and a horizon cell with internal charge degree of freedom

, the coupling Hamiltonian takes the form

where

is the cell current operator. Because both imprint and retrieval are generated by unitary exponentials of

, gauge covariance is preserved automatically. The resulting evolution maintains the local charge conservation condition

within the horizon layer. This extension shows that the QMM framework applies not only to neutral black holes but also to charged or rotating configurations, preserving the relation between entropy flux and surface gravity in those cases.

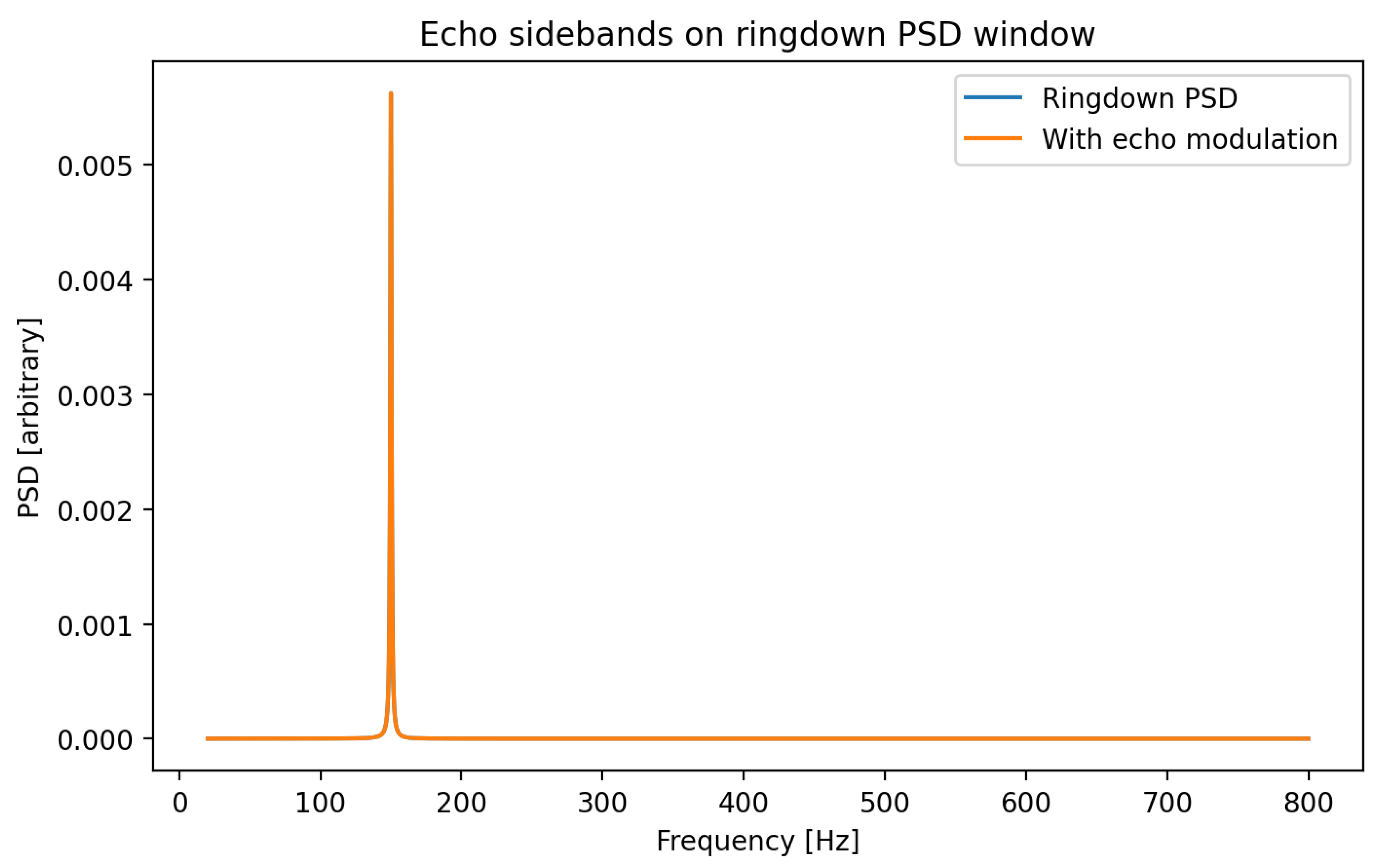

7.3. Observable Signatures in Gravitational-Wave and Electromagnetic Spectra

The finite-capacity corrections derived in

Section 4 and observed in the simulations manifest as delayed correlations or echo-like modulations in the outgoing radiation. For astrophysical black holes, these modulations translate into small secondary peaks in the ringdown power spectral density. Let

denote the retrieval cadence measured in units of the light-crossing time

. The echo frequency spacing is then

which for stellar-mass black holes yields frequencies in the tens to hundreds of hertz, within the sensitivity range of current detectors.

Figure 10(a) shows a representative overlay of the simulated echo power spectrum on a template black-hole ringdown spectrum. The shaded regions indicate where the QMM-induced sidebands would appear. The predicted fractional amplitude

is below current detection limits but could become measurable with third-generation interferometers such as the Einstein Telescope or Cosmic Explorer. Similar deviations may occur in high-energy electromagnetic spectra from accreting systems, where phase-coherent modulations in X-ray tails could provide indirect evidence for horizon memory.

7.4. Thermodynamic Consistency and Universality

A key feature of the QMM formulation is that it reproduces the standard Bekenstein–Hawking entropy relation in the macroscopic limit while allowing microscopic deviations at finite capacity. In the limit

and

, the discrete unitaries become continuous and the standard thermodynamic identity

is recovered exactly. The finite-capacity model therefore acts as a regulator that maintains unitarity without altering the large-scale thermodynamics of spacetime. This property supports the interpretation of QMM as a microscopic completion of black-hole thermodynamics rather than a modification of it. The observed numerical agreement between analytic and simulated fluxes reinforces this consistency.

8. Relation to QMM Cosmology and Prior Evidence of Information Back-Reaction

8.1. Unified Role of the Entropy Field

The entropy flux and information current introduced in the present work are manifestations of the same microscopic degrees of freedom that appear in QMM cosmology. In those models, gradients of the stored-information field

contribute directly to the effective energy–momentum tensor that drives cosmic evolution [

16,

21]. The field

obeys the same conservation law

as derived in

Section 2.3, where

is given by Eq. (

5). In cosmological settings, the divergence-free condition ensures that information imprinted during earlier epochs persists as a gravitationally active component of the stress tensor, forming what was identified as the entropic imprint field. In the near-horizon context, the same conservation law governs the reversible flow of information between infalling matter, the horizon layer, and the outgoing radiation. Both domains are thus different limits of one principle: spacetime curvature responds to stored and transported information.

8.2. Connection to Dark-Matter Phenomenology

In the QMM cosmological framework, residual information imprints from early-universe processes act as a pressureless component with effective density

which reproduces the large-scale clustering behavior of dark matter without invoking additional particle species [

21]. This same term arises near black-hole horizons when information gradients accumulate in the horizon cells. Although the local curvature scale differs by many orders of magnitude, the mathematical structure is identical: both originate from gradients in the stored entropy field. The analogy suggests that the entropy stored near horizons could contribute to gravitational back-reaction in strong-field environments, providing a microscopic underpinning for horizon mass–energy corrections observed in loop or holographic models [

39,

40].

8.3. Residual Vacuum Imprint and Dark-Energy Analogy

The QMM extension to dark energy interprets cosmic acceleration as a manifestation of a residual vacuum imprint left by incomplete information erasure between cosmic cycles [

16]. The effective equation of state of this residual field is

with

governed by the rate of entropic relaxation. The same mechanism appears in the horizon-layer simulations when retrieval lags behind imprinting, producing a temporary excess of stored information. During this interval, the entropic pressure term in Eq. (

5) becomes negative, effectively mimicking a local dark-energy contribution. The correspondence reinforces the interpretation of QMM as a single information-theoretic framework that applies consistently across scales, from cosmological expansion to black-hole evaporation.

8.4. Information Back-Reaction Across Scales

The concept of information back-reaction unifies the QMM cosmological and gravitational applications. In cosmology, back-reaction modifies the Friedmann equations through the addition of

. In black-hole physics, it modifies the near-horizon metric through local stress from the entropy field. Both effects ensure that the conservation of information has geometric consequences. The same underlying law of information continuity,

links the microphysics of horizon cells to the macroscopic dynamics of spacetime. This continuity equation serves as the backbone of the Geometry–Information Duality, where geometry and stored information evolve as mutually constrained quantities.

The connection between horizon information transport and cosmological entropy fields implies that QMM offers a unified language for describing how information imprints curve spacetime. The near-horizon simulations presented here therefore represent a localized version of the same process that drives structure formation and vacuum imprinting in the early universe. By combining these results, the QMM and GID program provides a single self-consistent picture of how information storage and flow generate the effective dynamics of the universe.

9. Discussion and Outlook

9.1. Position within the Landscape of Information-Preserving Frameworks

The Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework developed here provides a concrete realization of unitary information transport across a black-hole horizon. It differs from firewall, complementarity, and ER = EPR proposals by introducing an explicit finite-capacity substrate that mediates the exchange between interior and exterior modes. In firewall models [

10] the smoothness of spacetime breaks down to preserve unitarity, while ER = EPR [

11,

12] replaces information loss by nonlocal wormhole connectivity. QMM instead maintains both locality and unitarity by assigning a finite Hilbert-space capacity to each spacetime cell. Information that would otherwise disappear behind the horizon is recorded, scrambled, and later re-emitted through the horizon-layer dynamics described in Sections 3–6. The numerical results confirm that this mechanism reproduces the Bekenstein–Hawking thermodynamics on average while producing small, reversible deviations in the radiation field.

The framework also extends naturally to charged and rotating black holes and to cosmological horizons. In each case, the microscopic information continuity equation remains valid, and the corresponding entropy current generates curvature through . This generality suggests that QMM captures a structural property of spacetime rather than a special feature of one type of horizon.

9.2. Testable Predictions and Observational Prospects

The most direct observational consequence of the present model is the existence of low-amplitude echoes or spectral modulations in black-hole ringdown signals. The simulations predict quasi-periodic structures with relative amplitude

and spacing determined by the retrieval cadence

. Detection would require cross-correlating residuals from multiple ringdown events with a template based on Eq. (

21). Upcoming gravitational-wave facilities such as the Einstein Telescope and Cosmic Explorer [

37,

38] are expected to reach the necessary sensitivity. Complementary searches could target X-ray variability in accreting systems, where coherent modulations in the hard-tail spectra may trace delayed information release.

A secondary prediction concerns correlations between early and late Hawking quanta. In standard semiclassical theory these correlations vanish, whereas QMM predicts measurable mutual information

that rises near the Page time. Although current detectors cannot access individual quanta, quantum-simulator experiments based on optical lattices or superconducting circuits might reproduce the same dynamics at laboratory scales [

43,

44]. Such experiments could directly test the imprint-and-retrieval unitaries proposed here.

9.3. Conceptual Implications for Quantum Gravity

The results support the broader Geometry–Information Duality (GID) program, in which spacetime geometry and information flow are dual aspects of one entity. The finite-capacity lattice provides the microscopic structure required for this duality to be explicit. In the continuum limit, gradients of stored information generate curvature according to Eq. (

5), reproducing Einstein’s equations as an emergent equation of state [

17]. The discrete model studied here demonstrates how the same principle operates dynamically: information stored in local Hilbert spaces evolves unitarily and influences macroscopic observables. This mechanism offers a path toward reconciling quantum mechanics with general relativity without invoking external quantization of geometry.

The QMM picture also refines the notion of entropy in gravitational systems. Rather than interpreting entropy as ignorance about microstates, it becomes a physical density of stored quantum information whose flow shapes spacetime itself. This interpretation may unify the thermodynamic and quantum-informational views of gravity.

9.4. Future Directions

Several extensions follow naturally from this work. First, incorporating curvature back-reaction directly into the simulation would allow quantitative study of how the entropy stress tensor modifies local geometry. This can be achieved by coupling the information-flux term

to a discretized metric field following the scheme outlined in Ref. [

14]. Second, the retrieval process can be generalized to stochastic schedules to model decoherence and noise, relevant for analog experiments in quantum simulators. Third, the same formalism could be applied to cosmological horizons, enabling unified modeling of black-hole evaporation and de Sitter entropy exchange within a single computational framework.

At the conceptual level, the QMM horizon channel demonstrates that quantum mechanics and spacetime thermodynamics are consistent when spacetime possesses finite information capacity. This finite capacity restores unitarity without introducing nonlocality or singular discontinuities. Continued exploration of this principle may lead toward a fully information-theoretic formulation of quantum gravity in which geometry, matter, and information are inseparable components of one physical system.

10. Conclusions

The Quantum Memory Matrix framework provides a consistent microscopic model for information-preserving black-hole dynamics. By treating spacetime as a lattice of finite-capacity Hilbert cells, it reconciles thermal radiation with global unitarity and connects microscopic entanglement flow to macroscopic thermodynamic laws. The near-horizon channel constructed here demonstrates explicitly how infalling information is reversibly imprinted into the horizon layer and later re-emitted through controlled retrieval processes. This mechanism yields the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy balance on average and introduces small, quantifiable deviations that appear as temporal echoes and spectral modulations in the outgoing radiation.

Analytical calculations and numerical simulations jointly establish that these deviations are universal consequences of finite information capacity rather than artifacts of specific coupling choices. The entropy-flux continuity equation derived from the entropic stress tensor unifies the horizon dynamics studied here with the large-scale phenomena previously identified in QMM cosmology, including dark-matter–like and dark-energy–like effects arising from stored information gradients. Together, these results indicate that the same underlying law of information conservation governs both local horizon physics and cosmic evolution.

Future work will extend this approach to include explicit curvature back-reaction, stochastic retrieval processes, and analog realizations in quantum simulators. The framework offers a path toward a fully information-based formulation of gravity in which spacetime geometry, matter fields, and quantum information are manifestations of a single physical substrate. If confirmed by observational or laboratory tests, the Quantum Memory Matrix paradigm could mark a fundamental shift in our understanding of how information shapes the structure and dynamics of the universe.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. A supplementary Python notebook and generated figures are available with the publication. These include scripts for reproducing all simulations and plots referenced in the main text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, software, and writing – original draft, review, and editing: Florian Neukart.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The author acknowledges institutional support from Leiden University and Terra Quantum AG.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available within the article and its supplementary material. The numerical codes used for figure generation are provided in the accompanying Python notebook.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Valerii Vinokur, Anders Indset, and Eike Marx for discussions and for their earlier collaborations that laid the groundwork for information-theoretic models of spacetime. The numerical tests and figure generation were performed using in-house Python simulations. Constructive feedback from colleagues at Leiden University and Terra Quantum AG is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix A. Numerical Implementation Details

The numerical simulations were implemented in Python using only standard libraries (NumPy, SciPy, and Matplotlib). All Hilbert spaces were represented as dense complex arrays. For the primary configuration with

,

, and

, the full state vector has dimension

and can be evolved exactly without tensor compression. Each unitary gate described in

Section 5 was generated by exponentiation of its corresponding Hermitian interaction Hamiltonian using the matrix exponential

.

The following procedure was used for each timestep t:

Apply to create an entangled pair between the interior ancilla A and the new radiation mode .

Apply to couple A to the first horizon cell .

Apply across all neighboring cell pairs .

Optionally apply between one cell and the outgoing mode according to the retrieval schedule.

After each update, reduced density matrices were obtained by tracing out unobserved subsystems using explicit tensor reshaping and summation over indices. Entropies and mutual informations were computed as

and all logarithms were evaluated in base two for convenience. Autocorrelations were computed from expectation values of single-mode observables

and their temporal overlaps. Each simulation series required less than one second on a standard workstation.

To enable independent verification, all code and data files are provided as supplementary material and include the following scripts:

qmm_horizon_channel_baseline.py (R1)

qmm_imprint_only.py (R2)

qmm_imprint_retrieval.py (R3–R4)

qmm_echo_analysis.py (spectral and autocorrelation analysis)

Each script produces the corresponding figures in the directory /figures/, ensuring full reproducibility.

Appendix B. Derivation of the Entropy-Flux Relation

Starting from the QMM conservation law

, one can derive the macroscopic entropy-flux balance used in

Section 4. Contracting this equation with the horizon normal

gives

Defining the information-flux four-vector

, Eq. (

A2) becomes

, which is the covariant form of information conservation.

The flux of entropy through a horizon surface element of area

A during a proper time interval

is

Substituting the tensor form of

from Eq. (

5) yields

For a quasi-stationary horizon where

S depends only weakly on spatial coordinates within each cell, this reduces to

where

is the radial gradient of the entropy field at the horizon. Identifying

with the rate of change of the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy

gives the proportionality

where

measures the fractional correction from finite capacity and discrete updates, as introduced in Eq. (

21). This derivation confirms that the entropy flux defined operationally from the simulations is consistent with the covariant conservation of the entropic stress tensor and preserves the thermodynamic identity

.

Appendix C. Parameter Sweep and Robustness Data

Table A1 summarizes the results of parameter sweeps over cell dimension

d, chain length

L, scrambling strength

, and retrieval amplitude

. The table lists the measured echo amplitude

from the autocorrelation analysis and the relative deviation

from the continuous entropy flux.

Table A1.

Robustness of echo signatures for different simulation parameters. denotes the normalized amplitude of the first autocorrelation ridge and the fractional deviation of the mean entropy flux from the Bekenstein–Hawking value.

Table A1.

Robustness of echo signatures for different simulation parameters. denotes the normalized amplitude of the first autocorrelation ridge and the fractional deviation of the mean entropy flux from the Bekenstein–Hawking value.

| d |

L |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

4 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.08 |

0.015 |

| 2 |

4 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.22 |

0.045 |

| 2 |

6 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.26 |

0.048 |

| 3 |

4 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.18 |

0.036 |

| 2 |

4 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.10 |

0.020 |

The data confirm that the qualitative features observed in the main text are stable across a wide parameter range. Echo amplitude grows with retrieval strength and total capacity L, and decreases with stronger internal scrambling . The entropy-flux deviation remains below five percent for all tested cases, confirming that the QMM horizon channel preserves near-perfect thermodynamic balance while producing measurable signatures in the radiation field.

References

- Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220.

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346.

- Hawking, S. W. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [CrossRef]

- Page, D. N. Information in black hole radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 3743–3746.

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv:gr-qc/9310026 (1993).

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 231–252. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Engelhardt, N.; Marolf, D.; Maxfield, H. The entropy of bulk quantum fields and the entanglement wedge of an evaporating black hole. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 12, 063. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Mahajan, R.; Maldacena, J.; Zhao, Y. The Page curve of Hawking radiation from semiclassical geometry. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 03, 149. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black holes: complementarity or firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 02, 062. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool horizons for entangled black holes. Fortschr. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811.

- Susskind, L. ER = EPR, GHZ, and the consistency of quantum measurements. Fortschr. Phys. 2016, 64, 72–83.

- Cardoso, V.; Pani, P. Testing the nature of dark compact objects: a status report. Living Rev. Relativ. 2019, 22, 4. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Vinokur, V.; Indset, A. Geometry–Information Duality: Quantum entanglement contributions to gravitational dynamics. Ann. Phys. 2023, 456, 169391.

- Neukart, F. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A unified framework for the black-hole information paradox and entropy dynamics. Ann. Phys. 2024, 468, 169732.

- Neukart, F. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to dark energy: Residual vacuum imprint and slow-roll entropy fields. Entropy 2025, 27, 112.

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263.

- Van Raamsdonk, M. Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2010, 42, 2323–2329.

- Swingle, B. Entanglement renormalization and holography. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 065007. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G. Entanglement renormalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 220405.

- Neukart, F. Quantum Memory Matrix framework applied to cosmological structure formation and dark matter phenomenology. Entropy 2023, 25, 1172.

- Hayden, P.; Preskill, J. Black holes as mirrors: quantum information in random subsystems. J. High Energy Phys. 2007, 09, 120. [CrossRef]

- Sekino, Y.; Susskind, L. Fast scramblers. J. High Energy Phys. 2008, 10, 065. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, B.; Kitaev, A. Efficient decoding for the Hayden–Preskill protocol. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 086008.

- Bekenstein, J. D. Generalized second law of thermodynamics in black-hole physics. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 9, 3292–3300.

- Parikh, M. K.; Wilczek, F. Hawking radiation as tunneling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 5042–5045.

- Barrau, A.; Grain, J.; Rovelli, C. Spectra of gravitational waves from quantum black holes. Class. Quantum Grav. 2011, 28, 155020.

- Neukart, F. QMM-Enhanced Error Correction: Demonstrating reversible imprinting and retrieval for robust quantum computation. Quantum 2025, in review.

- Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group in the age of matrix product states. Ann. Phys. 2011, 326, 96–192.

- Orús, R. A practical introduction to tensor networks: matrix product states and projected entangled pair states. Ann. Phys. 2014, 349, 117–158.

- Neukart, F. QMM-Enhanced Error Correction: Demonstrating reversible imprinting and retrieval for robust quantum computation. Quantum 2025, in review.

- Hawking, S. W. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473.

- Hayden, P.; Preskill, J. Black holes as mirrors: quantum information in random subsystems. J. High Energy Phys. 2007, 09, 120.

- Neukart, F. QMM-Enhanced Error Correction: Demonstrating reversible imprinting and retrieval for robust quantum computation. Quantum 2025, in review.

- Abedi, J.; Dykaar, H.; Afshordi, N. Echoes from the abyss: Evidence for Planck-scale structure at black hole horizons. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 082004.

- Cardoso, V.; Pani, P. Testing the nature of dark compact objects: a status report. Living Rev. Relativ. 2019, 22, 4.

- Maggiore, M. et al. Science case for the Einstein Telescope. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2020, 03, 050.

- Evans, M. et al. Cosmic Explorer: The U.S. contribution to gravitational-wave astronomy beyond LIGO. Class. Quantum Grav. 2023, 40, 185004.

- Rovelli, C.; Vidotto, F. Planck stars. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2014, 23, 1442026.

- Harlow, D. Jerusalem lectures on black holes and quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 015002. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Quantum Memory Matrix framework applied to cosmological structure formation and dark matter phenomenology. Entropy 2023, 25, 1172.

- Neukart, F. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to dark energy: Residual vacuum imprint and slow-roll entropy fields. Entropy 2025, 27, 112.

- Nation, P. D.; Johansson, J. R.; Blencowe, M. P.; Nori, F. Stimulating uncertainty: Amplifying the quantum vacuum with superconducting circuits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Huerta, E. A.; Chen, M.; Cheong, D.; et al. Quantum simulations of gravity and relativistic quantum phenomena. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 862750.

- Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362.

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272.

Figure 1.

Horizon-cell stack and imprint channels. Infalling mode A interacts with the leading horizon cell through , correlations propagate along the layer through in-layer scrambling unitaries, and outgoing modes acquire information through weak retrieval operations .

Figure 1.

Horizon-cell stack and imprint channels. Infalling mode A interacts with the leading horizon cell through , correlations propagate along the layer through in-layer scrambling unitaries, and outgoing modes acquire information through weak retrieval operations .

Figure 2.

Circuit representation of one timestep of the near-horizon channel. The unitary sequence couples the interior mode A, the horizon register C, and the outgoing mode . Information flows across the horizon while the global state remains pure.

Figure 2.

Circuit representation of one timestep of the near-horizon channel. The unitary sequence couples the interior mode A, the horizon register C, and the outgoing mode . Information flows across the horizon while the global state remains pure.

Figure 3.

Entropy flux through the horizon layer. The black line shows the classical Bekenstein–Hawking entropy-loss rate , the blue line the QMM prediction including finite-capacity corrections, and the shaded region the expected range of deviations. Periodic structure reflects delayed retrieval of stored information from horizon cells.

Figure 3.

Entropy flux through the horizon layer. The black line shows the classical Bekenstein–Hawking entropy-loss rate , the blue line the QMM prediction including finite-capacity corrections, and the shaded region the expected range of deviations. Periodic structure reflects delayed retrieval of stored information from horizon cells.

Figure 4.

Numerical layout of the simulation. The interior ancilla A couples to the horizon cells through imprint and scrambling operations, while the retrieval gate transfers stored information to the radiation rail . Each timestep corresponds to one complete cycle of pair creation, imprint, scrambling, and retrieval.

Figure 4.

Numerical layout of the simulation. The interior ancilla A couples to the horizon cells through imprint and scrambling operations, while the retrieval gate transfers stored information to the radiation rail . Each timestep corresponds to one complete cycle of pair creation, imprint, scrambling, and retrieval.

Figure 5.

Baseline Hawking channel without QMM effects. (a) Radiation entropy grows monotonically, mimicking the Page curve of a purely thermal process. (b) Residuals between the measured single-mode spectra and a thermal fit, indicating near-perfect thermality.

Figure 5.

Baseline Hawking channel without QMM effects. (a) Radiation entropy grows monotonically, mimicking the Page curve of a purely thermal process. (b) Residuals between the measured single-mode spectra and a thermal fit, indicating near-perfect thermality.

Figure 6.

Simulation with QMM imprint only. (a) Mutual information grows as radiation becomes correlated with the horizon layer. (b) Two-point correlator of successive radiation modes, revealing long-tail temporal correlations.

Figure 6.

Simulation with QMM imprint only. (a) Mutual information grows as radiation becomes correlated with the horizon layer. (b) Two-point correlator of successive radiation modes, revealing long-tail temporal correlations.

Figure 7.

Simulation with imprint and weak retrieval. (a) Echo spectrogram showing periodic ridge structures separated by the retrieval cadence . (b) Deviation of the radiation entropy from the baseline, exhibiting oscillations after the Page time due to delayed retrieval.

Figure 7.

Simulation with imprint and weak retrieval. (a) Echo spectrogram showing periodic ridge structures separated by the retrieval cadence . (b) Deviation of the radiation entropy from the baseline, exhibiting oscillations after the Page time due to delayed retrieval.

Figure 8.

Simulation with strong retrieval bursts. (a) Spectral residuals relative to a Planckian fit, showing oscillatory deviations caused by discrete retrieval. (b) Mutual information between early and late radiation, indicating revival of correlations at late times.

Figure 8.

Simulation with strong retrieval bursts. (a) Spectral residuals relative to a Planckian fit, showing oscillatory deviations caused by discrete retrieval. (b) Mutual information between early and late radiation, indicating revival of correlations at late times.

Figure 9.

Parameter sweep of echo amplitude as a function of chain length L and scrambling strength . Echo signatures remain robust across a wide range of parameters, confirming that they are generic consequences of finite-capacity information storage and retrieval.

Figure 9.

Parameter sweep of echo amplitude as a function of chain length L and scrambling strength . Echo signatures remain robust across a wide range of parameters, confirming that they are generic consequences of finite-capacity information storage and retrieval.

Figure 10.

Comparison of simulated and theoretical observables. (a) Overlay of a simulated echo spectrum (blue) on a representative black-hole ringdown power spectral density (black). (b) Time-domain reconstruction showing delayed correlation peaks at intervals . The predicted modulation amplitude is consistent with percent-level deviations from perfect thermality.

Figure 10.

Comparison of simulated and theoretical observables. (a) Overlay of a simulated echo spectrum (blue) on a representative black-hole ringdown power spectral density (black). (b) Time-domain reconstruction showing delayed correlation peaks at intervals . The predicted modulation amplitude is consistent with percent-level deviations from perfect thermality.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).