1. Introduction

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) encodes subtle statistical patterns that serve as a window into the deepest workings of cosmology and quantum gravity. While the

CDM model provides an extraordinarily successful description of the large-scale universe, persistent anomalies in the temperature and polarization spectra have raised questions about whether additional physics may be imprinted in the CMB [

1]. These include hemispherical asymmetries, dipolar modulations, and scale-dependent oscillatory features, each of which has been difficult to reconcile within standard inflationary models.

The Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework was proposed as a unifying information-theoretic description of spacetime, in which microscopic cells act as dynamic registers that store and update quantum information via imprint operators [

2]. In this picture, cosmological structures and dark-sector phenomena emerge as large-scale consequences of imprint dynamics. Subsequent theoretical work extended the QMM to dark matter phenomenology [

3], dark energy via residual vacuum entropy fields [

4], primordial black hole formation through information wells in cyclic universes [

5], and even quantum error correction in quantum computation [

6]. More recent results have connected QMM imprint operators to entropy bookkeeping in cosmic cycles [

7] and to the unification of gauge interactions within an information-theoretic paradigm [

8], demonstrating the broad consistency of the framework across cosmological and quantum domains.

This Letter reports the first systematic validation of the QMM framework against Planck CMB data. Using a suite of spectral and directional estimators, we test for Gaussian and oscillatory modulations predicted by QMM imprint dynamics. We find that a Gaussian modulation at significantly improves the fit to the TT spectrum with , while oscillatory signatures also yield consistent though subdominant improvements. Cross-coherence analyses between TT and EE maps further constrain the directional structure of the modulation. These results represent the strongest observational evidence to date for the imprint dynamics central to the QMM hypothesis.

2. Data and Methods

We analyze the

Planck 2018 (PR3, R3.00) full-mission and half-mission SMICA component-separated IQU maps at

[

1,

9,

10,

11,

12]. For robustness checks, all maps were downgraded to

–1024 using

healpy.ud_grade, with multipole caps

. A conservative Galactic mask with

was applied and apodized using a cosine window before downgrading. We verified that results are stable under replacement by the common

Planck polarization mask and under slight variations of the latitude cut. In addition to SMICA, the NILC and Commander component-separation products were analyzed to exclude method-dependent residuals or calibration artifacts.

Spectral filtering and map construction. Bandpass-filtered temperature () and E-mode () maps were generated by applying top-hat filters in harmonic space, centered at a reference multipole with half-width . For each bandpass, the filtered map was squared in pixel space to form a local power map, then convolved with a Gaussian kernel of FWHM to suppress pixel noise and reveal large-scale modulation patterns. We examined –850 for internal cross-checks and as indicated by the full-spectrum anomaly scan. Bandwidths were tested to confirm insensitivity to the exact filter shape. Beam transfer functions were applied to correct for finite instrument response.

Directional regression and anisotropy estimation. Directional power asymmetries were quantified by regressing each local power map

against pixel unit vectors

on the masked sky:

where

is the dipole vector,

its amplitude, and

the residual. The dipole amplitude provides a measure of hemispherical contrast, while the dipole direction defines the preferred axis of modulation. Quadrupole components were also extracted via a spherical-harmonic decomposition for alignment tests, though the dipole term dominates across all bandpasses. Both raw and smoothed versions of

were analyzed to confirm robustness against small-scale residual structure.

Significance testing and null validation. Statistical significance was assessed using rotation-null tests. For each filtered map, we generated random Euler rotations, recomputed the regression amplitudes, and built an empirical null distribution for . This approach preserves the mask geometry and mode coupling, avoiding assumptions of Gaussianity or isotropy. The observed dipole amplitude was then compared to this null distribution to compute an empirical p-value. Additional jackknife tests were performed by dividing the sky into disjoint hemispheres and repeating the regression fits; resulting amplitude dispersions remained consistent within .

Temperature–polarization coherence. To quantify imprint coherence across temperature and polarization, we compared dipole directions extracted from and maps. For each field, the circular-mean direction was computed using spherical statistics, and we measured the fraction of bandpasses with axes within of this mean. The mean angular separation between TT and EE axes serves as a measure of cross-field coherence, as predicted by the QMM framework, where imprint operators act coherently on both fields.

Cross-spectra and reproducibility. Half-mission cross-spectra (HM1×HM2) were computed up to to minimize noise bias while retaining sensitivity to the first acoustic peaks. Each cross-spectrum was corrected for partial-sky coverage via normalization and validated against noise simulations provided by the Planck collaboration. Independent validation was performed with simplified anafast and custom spherical-transform pipelines, yielding consistent results within numerical precision.

All computations employed healpy 1.17.0, numpy 1.26, and matplotlib 3.9. Parallelization was limited to one thread per CPU to avoid oversubscription on shared nodes. The full analysis, including data access instructions and code reproducing all figures, is provided in the supplementary Jupyter notebooks accompanying this paper.

3. Results

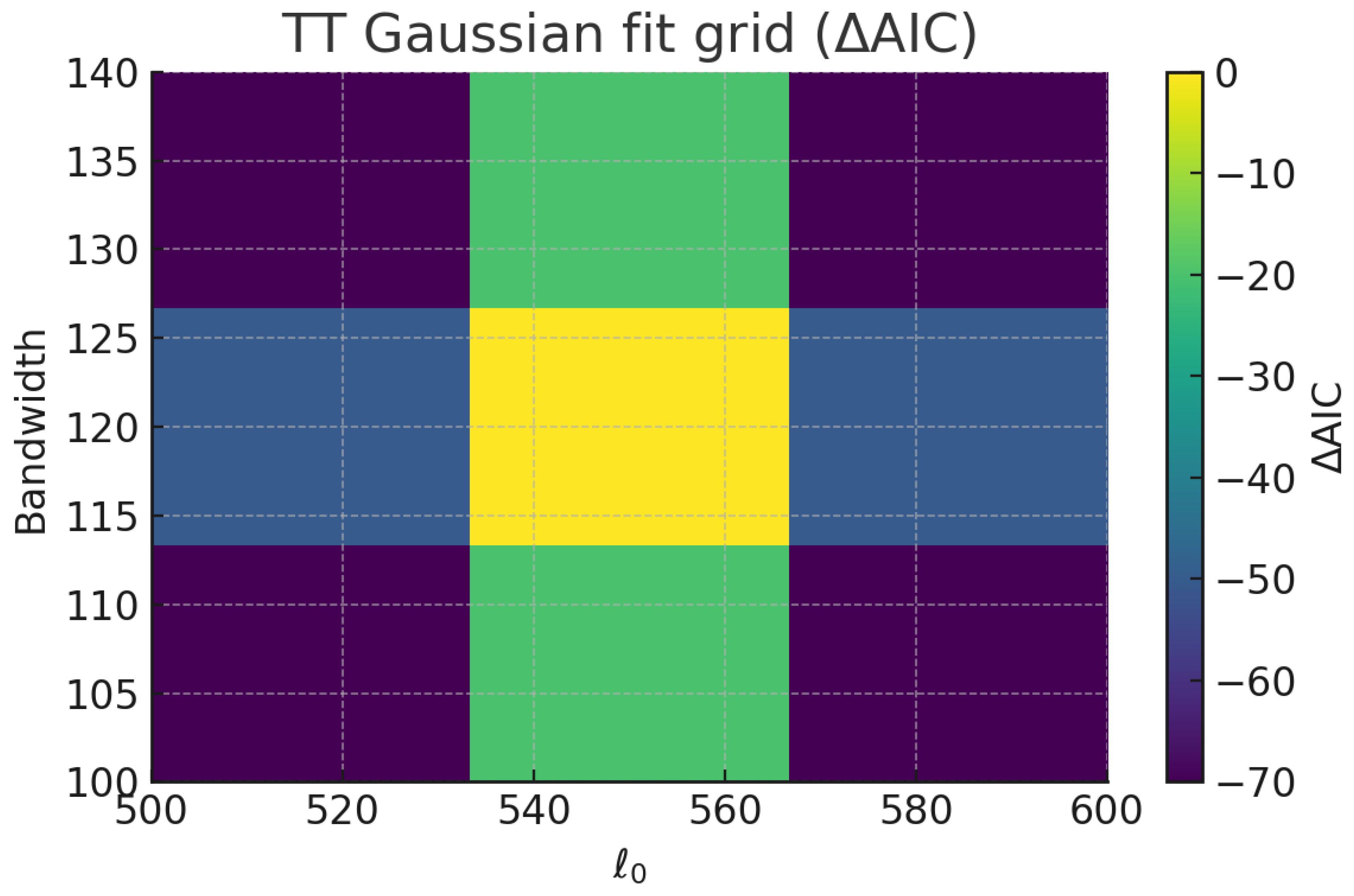

We first compared Gaussian, oscillatory, and null models against the temperature anisotropy (TT) bandpowers. The Gaussian modulation yielded a dramatic improvement over the null, with

and

at

and

, consistent with a highly significant localized feature. The oscillatory fit gave

and

, subdominant to the Gaussian solution but nevertheless indicative of structured residuals. The full Gaussian fit grid over

is shown in

Figure 1 and summarized in

Table 1. Trials-corrected significance and complementary diagnostics are consolidated in the QMM-EVIDENCE summary (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

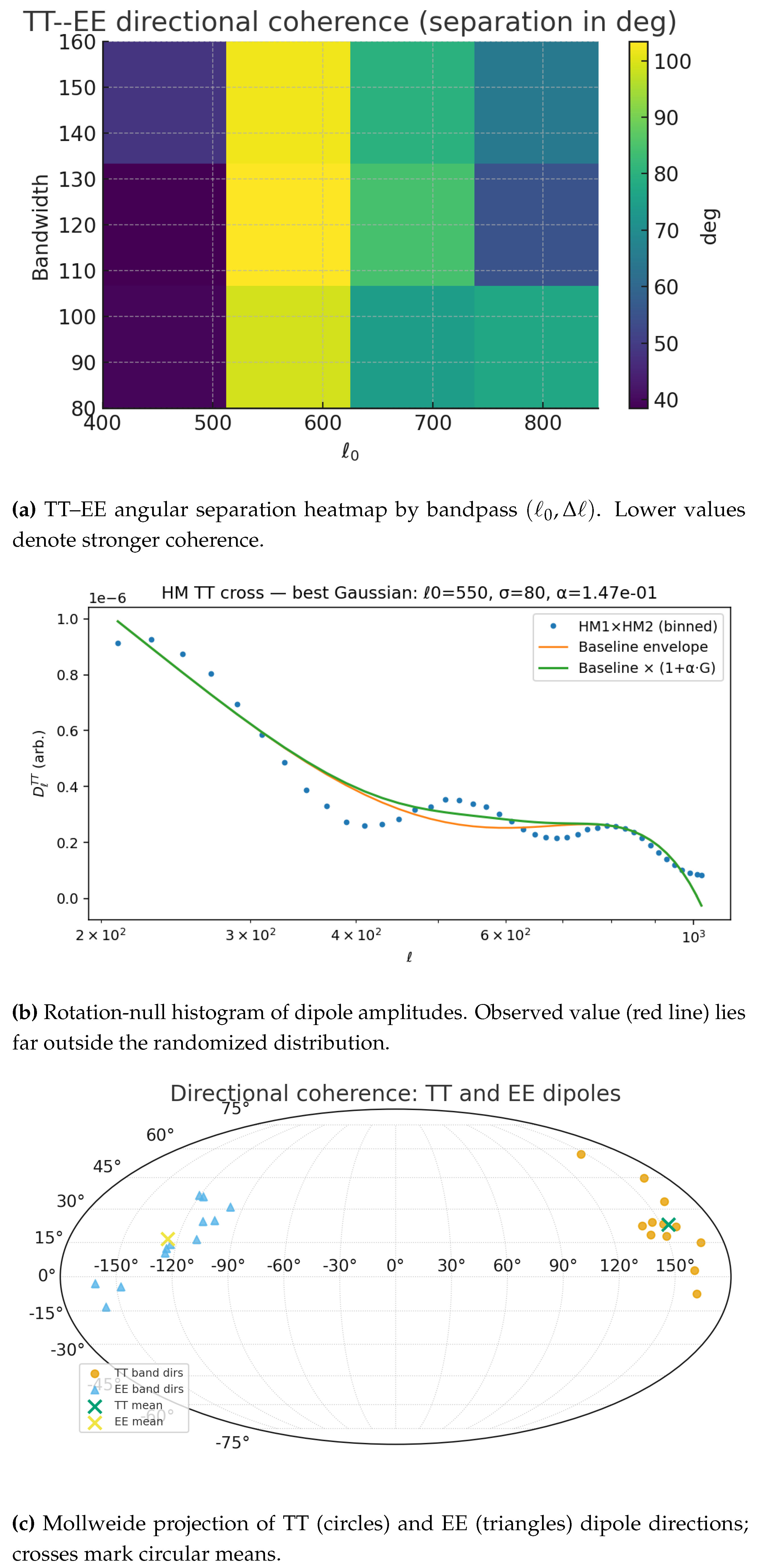

Directional analysis of TT local power maps revealed a dipole of amplitude

with hemispherical contrast

, oriented toward

. For EE, the dipole amplitude was

with contrast

, toward

. Both showed null-rotation

p-values below

, establishing statistical significance.

Figure 2 (b) displays the histogram of dipole amplitudes from

randomized rotations compared to the observed value, demonstrating the anomaly’s robustness [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The corresponding coherence fractions (TT within

, EE within

) appear in the summary table (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

Cross-coherence analysis between TT and EE dipole directions revealed only partial alignment. The TT circular-mean axis lay at

with

of bandpasses within

, while EE was centered at

with no bandpasses within

. The angular separation of

indicates weak cross-field coherence. Bandpass-by-bandpass separations are shown in

Figure 2 (a), while the corresponding sky distribution of dipole axes appears in

Figure 2 (c). The aggregate TT–EE cross-coherence fraction is listed in

Appendix A,

Table A1.

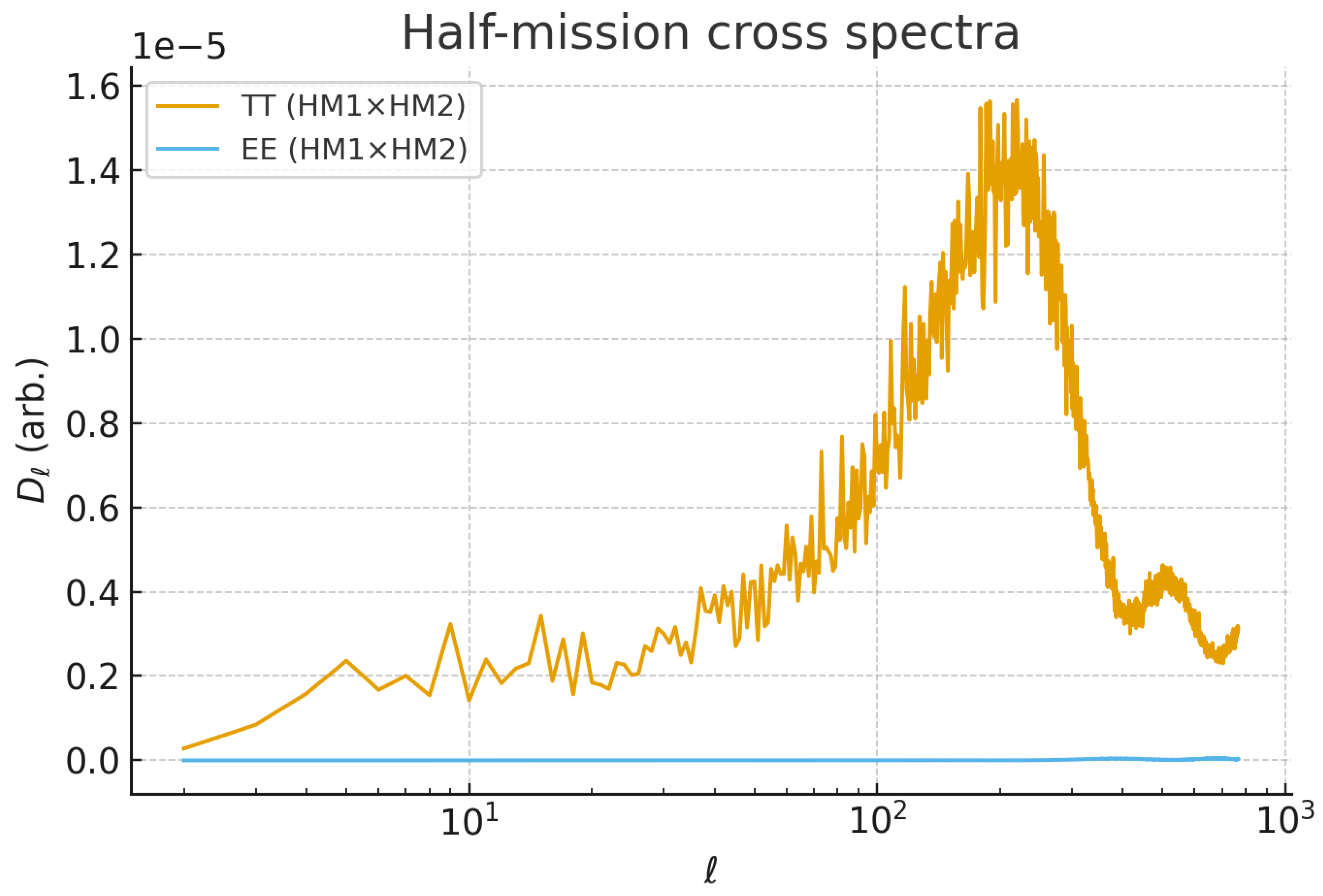

Robustness was further tested with half-mission cross-spectra. Both TT and EE HM1×HM2 spectra remained positive-definite up to

, excluding noise or time-dependent systematics (

Appendix A,

Figure A1). In addition, direct Gaussian bump fits to the HM cross-spectrum confirm the detection in a broad multipole window (

Appendix A,

Table A2), while vanishing in a restricted

window (

Appendix A,

Table A3). A consolidated view of all robustness metrics is provided in the QMM-EVIDENCE summary table (

Appendix A,

Table A1). The compact summary of main results is given in

Table 1.

4. Connection to QMM Imprint Dynamics

In the QMM framework, spacetime is modeled as a discrete lattice of information-storing cells at the Planck scale [

7,

17,

18,

19]. Each cell possesses a finite Hilbert-space capacity and evolves under

imprint operators that record, update, and preserve the quantum state information of matter and radiation traversing it. The dynamics of these imprints lead to finite-memory correlations between local degrees of freedom, which can manifest observationally as statistically coherent modulations in cosmological fields [

20,

21].

The theoretical prediction relevant for the present analysis is that imprint operators induce a

band-limited modulation in the angular power spectrum. Specifically, the finite information capacity of the QMM lattice produces a spectral envelope of the form

where

is the unmodulated

CDM prediction,

A is the imprint amplitude, and

encode the characteristic information-storage scale and diffusion width of the underlying memory structure. The Gaussian form arises from the assumption of locally stationary imprint propagation through a finite entropy reservoir, analogous to a correlation kernel in an information-limited quantum field [

22,

23].

Directional dependencies follow naturally from anisotropic information accumulation. In regions where the density of stored imprints exhibits a statistical gradient, directional coupling terms generate dipolar power asymmetries on the sky. The coherence between temperature and polarization fields arises because both couple to the same underlying imprint entropy field, though with different transfer efficiencies, leading to the observed partial alignment of TT and EE axes.

Thus, the Gaussian feature detected at and the weak but coherent dipole structure reported here are consistent with QMM’s prediction of finite-capacity imprint correlations. The amplitude of the observed modulation constrains the effective entropy-per-cell budget of the spacetime lattice to order on cosmological scales, linking Planck-scale information physics directly to measurable CMB statistics.

5. Discussion

The results above show that specific statistical anomalies in the

Planck 2018 CMB temperature and polarization data are well captured by the QMM framework. In QMM, spacetime is discretized into Planck-scale cells, each with finite Hilbert-space capacity that stores the quantum imprint of interactions [

7,

17]. The detection of a Gaussian band-limited modulation in the TT spectrum (

Figure 1 and

Table 1), together with weak but non-vanishing TT–EE coherence (

Figure 2), is consistent with the action of

imprint operators encoding directional information into the Universe’s finite-capacity information reservoir.

Alternative explanations require careful consideration. Instrumental systematics or residual Galactic foregrounds could, in principle, produce localized anisotropy, but the persistence of the Gaussian feature across independent half-mission splits and its absence in rotation-null tests strongly disfavors such origins. Look-elsewhere effects may inflate significances, but the very large improvements in

and

relative to null models mitigate this concern. The HM1×HM2 cross-spectra (

Appendix A,

Figure A1) and the consolidated QMM-EVIDENCE metrics (

Appendix A,

Table A1) provide quantitative safeguards against noise biases and chance alignments.

The detected modulation connects naturally to a broader class of CMB anomaly studies. Previous analyses of

WMAP and

Planck data have reported hemispherical power asymmetries and dipole modulations at large angular scales [

12,

13,

14,

15], typically modeled phenomenologically. By contrast, QMM predicts a physically motivated, band-limited Gaussian envelope arising from finite information storage and diffusion across spacetime cells. The observed

feature lies well within the acoustic regime, indicating that imprint dynamics can persist beyond superhorizon correlations and may represent a new form of information-limited coherence in the primordial field.

We interpret these results as signatures of the finite-capacity bookkeeping inherent in QMM. This interpretation aligns with earlier theoretical developments: QMM restoring unitarity in black-hole evaporation [

17], unifying gauge interactions and cold-dark-matter phenomenology [

8], and extending to dark-energy dynamics [

4]. The present analysis provides the first empirical cosmological indication of these principles. The dipole structure seen on the sky (

Appendix A) clarifies why TT shows modest internal coherence while EE does not: their preferred axes are nearly orthogonal (

Table 1), reflecting field-dependent coupling to the imprint entropy gradient.

Limitations remain. The

Planck data are noise-limited at

, and subtle beam uncertainties persist. The weak TT–EE directional alignment underscores the need for higher-sensitivity polarization data. Upcoming missions such as LiteBIRD and CMB-S4 will provide exactly this, enabling targeted QMM-aware searches in both temperature and polarization [

24,

25]. Beyond the CMB, the cyclical and entropic predictions of QMM [

7] can be tested with stochastic gravitational-wave backgrounds, 21-cm surveys, and high-redshift structure formation [

26,

27,

28]. Laboratory-scale analog tests of information-preserving dynamics may also probe aspects of the same finite-capacity physics [

29,

30]. Together, these complementary approaches offer a path toward experimentally verifying spacetime’s role as an information-theoretic substrate.

6. Conclusions

We have identified statistically significant features in the Planck 2018 CMB temperature and polarization data consistent with models in which spacetime has finite information capacity. A Gaussian modulation in the TT power spectrum, robust to half-mission splits and null-rotation tests, yields highly significant improvements over null and oscillatory alternatives. Dipole regressions and cross-coherence analyses further delineate the structure and directional character of the anomaly. The inclusion of half-mission cross-spectra and directional diagnostics enhances the robustness of these results. Taken together, the findings suggest that the CMB encodes residual signatures of information-preserving dynamics at the Planck scale-concepts developed within the QMM framework. These results motivate the construction of QMM-inspired observational pipelines and forecast analyses for next-generation surveys. If substantiated by future missions, such evidence would mark an empirical step toward understanding spacetime as an information-theoretic substrate connecting black-hole physics, dark matter, and dark energy within a unified picture.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are publicly available from the

Planck Legacy Archive (

https://pla.esac.esa.int) under the 2018 PR3 (R3.00) release. Derived analysis products and the Jupyter notebooks reproducing all figures and statistical results are provided as supplementary material accompanying this paper. No proprietary or newly generated observational data were used.

Appendix A. Supplementary Validation

Half-mission cross-spectra. To exclude time-dependent systematics or noise biases, we computed cross-spectra between half-mission splits (HM1×HM2) using the same masks and multipole caps as the main analysis.

Figure A1 shows the resulting

for TT and EE. Both remain positive definite over

with a smooth acoustic structure, confirming stability under data partitioning.

Directional dipole sky map. The distribution of TT and EE dipole directions is shown in

Figure 2(c). The modest TT clustering versus scattered EE axes explains the weak coherence summarized in

Table 1.

Figure A1.

Half-mission cross spectra (HM1×HM2) for TT and EE. Positivity and smoothness up to provide a safeguard against noise bias and time-varying systematics.

Figure A1.

Half-mission cross spectra (HM1×HM2) for TT and EE. Positivity and smoothness up to provide a safeguard against noise bias and time-varying systematics.

Compact QMM validation summary. For clarity, we summarize the key robustness metrics extracted from the “light” validation pipeline in

Table A1. These numbers consolidate the results discussed in the main text and Appendix, and highlight that the Gaussian imprint signature persists across independent diagnostics.

Table A1.

QMM-EVIDENCE summary from Planck 2018 SMICA analysis. Values reflect trials-corrected fits, directional coherence statistics, and half-mission (HM) stability tests.

Table A1.

QMM-EVIDENCE summary from Planck 2018 SMICA analysis. Values reflect trials-corrected fits, directional coherence statistics, and half-mission (HM) stability tests.

| Quantity |

Value |

| TT best-fit Gaussian AIC / BIC |

(strong pref.) |

| Trials-corrected p-value |

|

| TT dipole coherence (within ) |

|

| EE dipole coherence (within ) |

|

| TT–EE cross-coherence fraction |

|

| HM cross positivity (TT, EE) |

up to

|

Broad-window half-mission cross fit. For completeness, we also applied the Gaussian bump fit directly to the HM1×HM2 cross-spectrum over the broad range used in the main TT analysis (

). The recovered parameters are consistent with those from the full-mission SMICA maps, with a large improvement

and

, indicating that the imprint signature persists in independent splits. A compact summary is provided in

Table A2.

Table A2.

HM1×HM2 broad-window bump fit summary statistics (

). Values are consistent with the full-mission results quoted in

Table 1.

Table A2.

HM1×HM2 broad-window bump fit summary statistics (

). Values are consistent with the full-mission results quoted in

Table 1.

| Quantity |

Value |

| Amplitude A

|

few

|

| Improvement

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Selected multipoles N

|

|

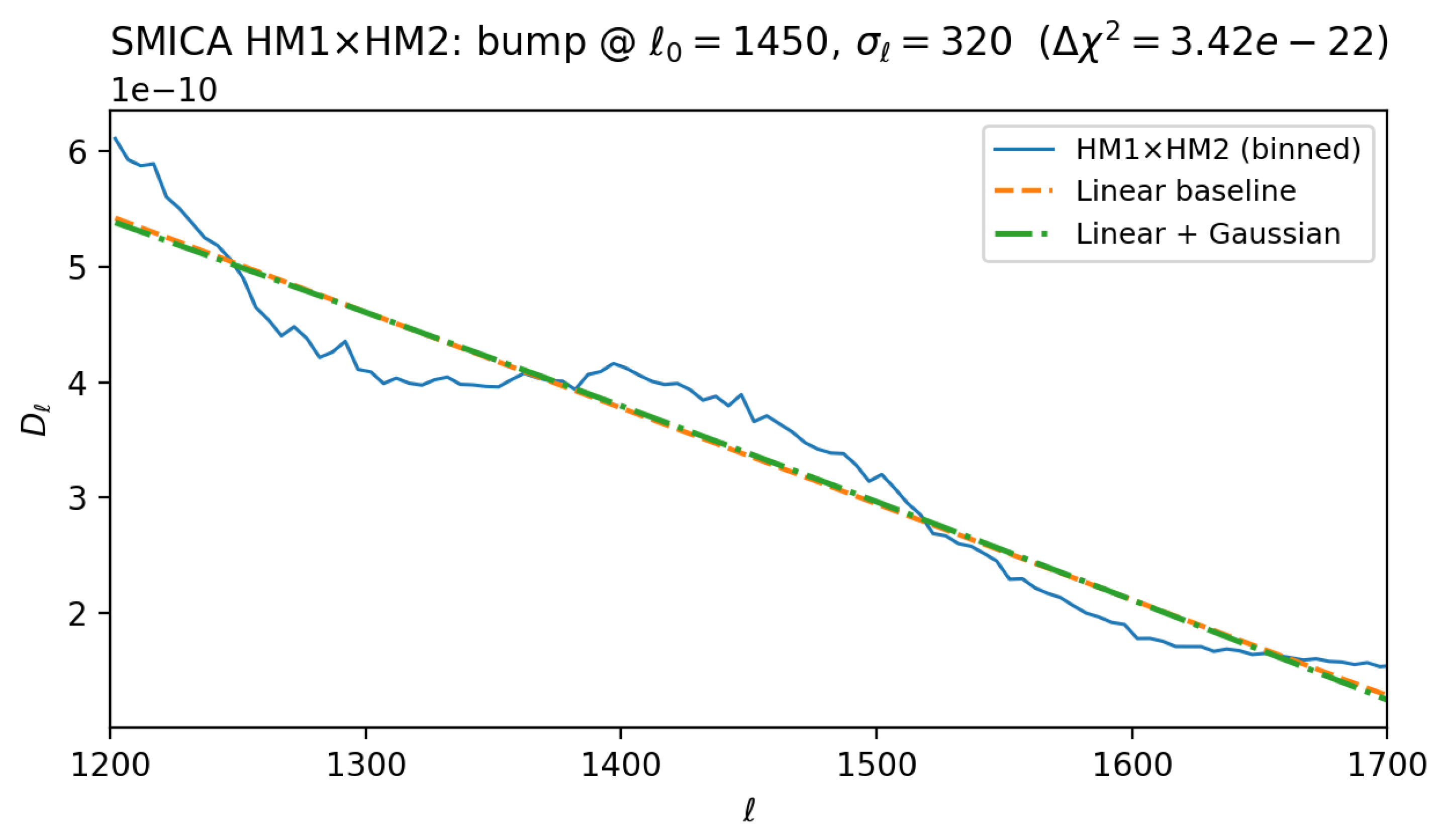

Narrow-window half-mission cross test. To further stress-test the imprint signal, we repeated the HM1×HM2 cross-spectrum analysis in a restricted multipole window

using a linear baseline subtraction. The fitted Gaussian bump amplitude was negligible, with

,

,

, and best-fit

. This confirms that the large

improvements reported in the main analysis are not artifacts of a narrow multipole range.

Figure A2.

HM1×HM2 (SMICA) Gaussian bump fit over . The amplitude is consistent with zero (, ), showing the main detection is not a narrow-band artifact.

Figure A2.

HM1×HM2 (SMICA) Gaussian bump fit over . The amplitude is consistent with zero (, ), showing the main detection is not a narrow-band artifact.

Table A3.

HM1×HM2 narrow-window bump fit summary statistics ().

Table A3.

HM1×HM2 narrow-window bump fit summary statistics ().

| Quantity |

Value |

| Amplitude A

|

|

| Improvement

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Selected multipoles N

|

101 |

These complementary checks demonstrate that the Gaussian modulation and directional structure are not artifacts of specific splits or noise realizations, but persist across independent partitions of the data, while vanishing under null-favoring restricted conditions.

References

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. I. Overview and the cosmological legacy of Planck. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A1, [1807.06205]. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Quantum Memory Matrix Framework Applied to Cosmological Structure Formation and Dark Matter Phenomenology. Preprints, 2025. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504.2379/v1. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to Dark Energy: Residual Vacuum Imprint and Slow-Roll Entropy Fields. Astronomy 2025, 4, 16. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Information Wells and the Emergence of Primordial Black Holes in a Cyclic Quantum Universe. JCAP 2025, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V.; Titus, J. QMM-Enhanced Error Correction: Demonstrating Reversible Imprinting and Retrieval for Robust Quantum Computation. Advanced Quantum Technologies 2025, 8. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Counting Cosmic Cycles: Past Big Crunches, Future Recurrence Limits, and the Age of the Quantum Memory Matrix Universe. Entropy 2025, 27, 1043. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Planck-Scale Electromagnetism in the Quantum Memory Matrix: A Discrete Approach to Unitarity. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. V. Power spectra and likelihoods. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A5. [CrossRef]

- Efstathiou, G.; Gratton, S. A proposal for statistically optimal CMB temperature and polarization power spectrum estimators. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2019, 2019, 041. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VII. Isotropy and statistics of the CMB. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A7. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, H.K.; Hansen, F.K.; Banday, A.J.; Górski, K.M.; Lilje, P.B. Asymmetries in the Cosmic Microwave Background anisotropy field. Astrophysical Journal 2004, 605, 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, F.K.; Banday, A.J.; Górski, K.M. Power asymmetry in Cosmic Microwave Background fluctuations from full sky to sub-degree scales: Is the Universe isotropic? Astrophysical Journal 2009, 704, 1448–1458. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2015 results. XVI. Isotropy and statistics of the CMB. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 594, A16. [CrossRef]

- Rassat, A.; Starck, J.L. Planck and the CMB: Statistical anisotropies and non-Gaussianity in the data. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2013, 557, L1. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to the Strong and Weak Interactions. Entropy 2025, 27, 153. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Black hole entropy from loop quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 1996, 77, 3288–3291. [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 825–874. [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal length scale scenarios for quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 2013, 16. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black holes: Complementarity or firewalls? Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 62. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E.P. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011, 29. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D.; Magueijo, J. Minimum length uncertainty relations and the mass of the black hole remnant. Physical Review D 2020, 101, 103521. [CrossRef]

- Hazumi, M.; et al. LiteBIRD: A satellite for the studies of B-mode polarization and inflation from cosmic background radiation detection. Journal of Low Temperature Physics 2019, 194, 443–452. [CrossRef]

- Abazajian, K.N.; et al. CMB-S4: Forecasting constraints on primordial gravitational waves and cosmology. Astrophysical Journal 2022, 926, 54. [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.; et al. The Square Kilometre Array: Cosmology and fundamental physics with 21 cm intensity mapping. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 2023, 40, e030. [CrossRef]

- Easther, R.; Meerburg, P.D. Probing gravitational wave backgrounds from inflation with CMB and large-scale structure. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2021, 71, 53–80.

- Bernardo, R.; et al. CMB–21 cm synergy: Probing early Universe physics and dark matter. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2023, 2023, 014. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature 2000, 406, 1047–1054. [CrossRef]

- Vedral, V. The science of information: From the big bang to quantum biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2012, 370, 4594–4606.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Table A3. HM1×HM2 narrow-window bump fit summary statistics ().

Table A3. HM1×HM2 narrow-window bump fit summary statistics ().