1. Introduction

1.1. Missing–Mass Problem and CDM Successes/Tensions

The first indications that the visible mass in galaxies is insufficient to account for their observed kinematics date back to the pioneering work of Rubin and Ford, who showed that spiral-galaxy rotation curves remain flat well beyond the luminous disk [

1]. On cosmological scales, the

-cold-dark-matter (

CDM) model explains the acoustic peaks of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and the baryon acoustic–oscillation (BAO) standard ruler with impressive accuracy [

2]. Numerical simulations based on

CDM also reproduce the large-scale distribution of galaxies and the halo mass function [

3]. Despite these successes, several persistent small-scale discrepancies cast doubt on a purely particulate solution to the missing-mass problem. Dwarf galaxies display slowly rising density profiles inconsistent with the steep “cusps’’ predicted by dark-matter–only simulations; satellite counts around the Milky Way fall an order of magnitude below the expected sub-halo abundance (“missing-satellite’’ problem); and the brightest of those satellites appear too massive to be compatible with the

CDM concentration–mass relation (“too-big-to-fail’’) [

4]. The Bullet Cluster, meanwhile, shows a clear separation between the X-ray–emitting gas and the mass distribution inferred from weak lensing, a feature difficult to reconcile with modified-gravity models [

5]. Collectively, these tensions motivate a re-examination of the underlying assumptions about the nature of dark matter.

1.2. Motivation for Information-Based Modifications of Gravity

The notion that gravity might be an emergent, entropic phenomenon has a long pedigree. Bekenstein’s identification of black-hole horizon area with entropy and Hawking’s discovery of thermal radiation hinted at a deep link between information and spacetime geometry [

6]. Jacobson subsequently showed that the Einstein field equations can be recovered as an equation of state derived from local Rindler-horizon entropy and the Clausius relation

[

7]. More recently, Verlinde proposed that galaxy rotation curves and lensing could arise from an elastic response of an underlying entanglement medium, producing an apparent dark-matter force law without new particles [

8]. Although such entropic or emergent-gravity proposals face difficulties in matching all cosmological observables [

13,

14], they underscore the plausibility that microscopic information degrees of freedom can back-react on the low-energy metric.

1.3. The Quantum Memory Matrix Programme

The Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework advances the information-geometric agenda by assigning a finite-dimensional Hilbert space to every Planck-scale spacetime cell, capable of recording the quantum state of local interactions. Initial work demonstrated that the aggregate entropy stored in the QMM provides a self-consistent bookkeeping device for the black-hole information paradox and yields a quantitative version of the Geometry–Information Duality, wherein curvature is sourced by entanglement across causal boundaries [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Those results imply that, after coarse-graining, the entropy field

contributes an additional, conserved stress–energy tensor to the Einstein equations. Because

S accumulates in proportion to astrophysical activity—star formation, mergers, feedback—the resulting gravitational effect is strongest precisely where dark-matter halos form, suggesting a natural route to explain the missing mass

without invoking new particles. To translate this mechanism into quantitative halo-scale predictions, we introduce in

Section 3 the

Holographically Regulated Entropic Imprinting (HREI) model, in which only entropy deposited across causal surfaces contributes to the gravitating QMM sector.

1.4. Goal and Structure of this Work

The objective of the present paper is to transform the qualitative QMM insight into a quantitative and testable cosmological model.

Section 2 derives the effective action by coarse-graining the Planck lattice through a heat-kernel expansion, fixing the single dimensionless coupling

on naturalness grounds.

Section 3 introduces the Holographically Regulated Entropic Imprinting (HREI) model, which localizes gravitationally active entropy flow to causal surfaces and calibrates the imprinting parameters to match realistic halo masses.

Section 5 shows that a slow-roll regime of the entropy field reproduces the

CDM expansion history while providing the requisite matter density.

Section 6 incorporates QMM into a modified Boltzmann solver and confronts the model with CMB and BAO data, whereas

Section 7 presents the first

N-body simulations with an evolving entropy grid, demonstrating agreement with halo statistics and a mitigation of small-scale tensions.

Section 8 solves the spherically symmetric field equations to fit rotation curves and cluster lensing, highlighting percent-level deviations in the convergence power spectrum that distinguish QMM from particulate dark matter. Stability, energy conditions, and potential links to late-time acceleration are analysed in

Section 9 and

Section 10. Throughout, we employ natural units

and a signature

; overdots denote derivatives with respect to cosmic time

t.

2. Microscopic Foundations of the QMM Field

2.1. Planck–Cell Lattice and Local Hilbert Spaces

We model the deep ultraviolet as a regular

1 lattice of Planck-sized four-volumes, each labeled by an index

i and carrying a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

in the spirit of causal-set discretizations [

16,

17]. Local quantum interactions “write’’ information into these cells through unitary maps

where

captures the reduced density operator of all fields restricted to cell

i. Because the number of distinguishable microstates per cell is finite, the lattice embodies a built-in ultraviolet regulator without breaking diffeomorphism invariance at macroscopic scales [

18].

2.2. Imprint Entropy Field

Define the

imprint entropy of cell

i as

a scalar under local Lorentz transformations. For any macroscopic region

containing

cells, we introduce a coarse-grained field

obtained by a Voronoi tessellation whose cells expand with the physical scale factor.

2

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the QMM lattice. Left: Planck-scale cells (grey) with Hilbert spaces . Right: a scattering event updates neighboring cells (orange) via maps, increasing their imprint entropy .

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the QMM lattice. Left: Planck-scale cells (grey) with Hilbert spaces . Right: a scattering event updates neighboring cells (orange) via maps, increasing their imprint entropy .

2.3. Real-space renormalisation and the continuum action

To obtain the infrared dynamics, we perform a block-spin coarse-graining: partition the lattice into hyper-cubic blocks of linear size

, trace over intra-block degrees of freedom, and integrate out short-wavelength fluctuations of

. The single-field effective action for the block-averaged entropy

is most efficiently derived with a heat-kernel expansion [

19,

20,

21]. Writing the Euclidean partition function as

, we find to lowest non-trivial order

where

Equation (

2) shows that the leading infrared relevant operator is the canonical gradient term

; curvature couplings such as

are parametrically suppressed by

. The analysis mirrors analogous gradient-expansion results in lattice gauge theory and spin systems, confirming that the QMM entropy behaves as a bona-fide scalar field at macroscopic scales.

2.4. Naturalness of the dimensionless coupling

Setting the coarse-graining scale to the comoving Hubble radius during matter–radiation equality,

, yields

for any

. Because

is insensitive to power-law shifts in

L—a reflection of the marginal nature of

in four dimensions—order-unity values are technically natural: radiative corrections generate only logarithmic running,

, with

for weakly curved backgrounds [

19]. This stability justifies treating

as a single phenomenological constant to be fitted by cosmological data in

Section 5.

Summary. Starting from a Planck lattice endowed with finite Hilbert spaces, we have (i) defined an imprint-entropy field, (ii) demonstrated via heat-kernel coarse-graining that the leading infrared operator is

, and (iii) shown that

is natural. These results supply the microscopic underpinning for the effective action introduced in

Section 5.

3. Holographically Regulated Entropic Imprinting

We propose that the gravitational effect of the QMM emerges not from uniform entropy deposition throughout spacetime, but from a geometrically regulated subset of entropy flow—specifically, from quantum interactions that irreversibly cross effective causal surfaces. These include decohering entanglements, radiative collapse, and localized information loss across dynamically formed horizons. We refer to the resulting framework as Holographically Regulated Entropic Imprinting (HREI).

3.1. Effective Imprinting Surfaces and Entropy Flux

In the HREI model, only entropy deposited across emergent two-surfaces—here called

effective imprinting surfaces (EIS)—contributes gravitationally. For a virialized region of radius

R, the relevant surface is the minimal causal boundary enclosing it. We postulate that the rate of entropy deposition through this surface scales holographically:

where

is a parameter with units of

that encapsulates the rate of entropy flux per unit area. This constant incorporates all microscopic and mesoscopic processes capable of imprinting entropy in a gravitationally active way—e.g., structure formation shocks, baryon–photon decoupling, black hole collapse, and irreversible decoherence.

The total entropy accumulated up to the Hubble time

is then:

3.2. Thermodynamic Conversion to Gravitational Mass

In thermodynamic systems, entropy contributes energy via:

where

is the effective temperature of the entropy flow. Following the spirit of the Davies–Unruh and Gibbons–Hawking effects, we define

not as a kinetic temperature but as an emergent gravitational temperature that reflects the typical local energy scale of irreversible information transfer. For virialized halos, we adopt a conservative average of

K, corresponding to

J.

The associated gravitational mass follows from:

Thus, the QMM halo mass increases quadratically with radius,

and the corresponding density profile is:

which reproduces the flat rotation curves observed in disk galaxies and the outer profile of NFW halos.

3.3. Parameter Calibration and Physical Justification

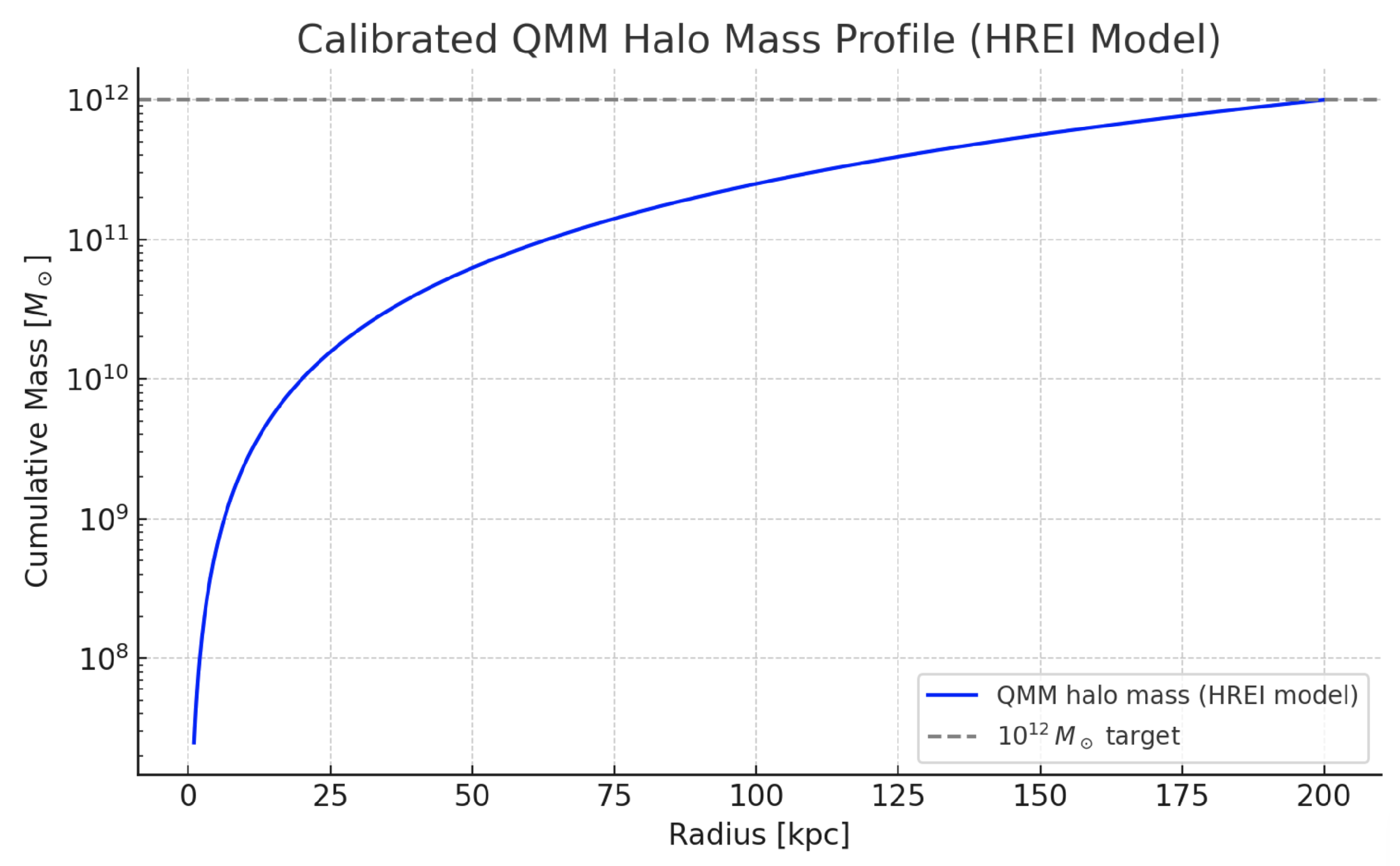

We now calibrate the model to match observed dark matter halos by fixing the entropy flux constant such that the cumulative QMM mass reaches at a radius of , consistent with halo masses for Milky Way–like galaxies.

Entropy flux constant: Using the cumulative mass formula,

and setting

, we determine that the required flux constant is

. This value ensures that QMM-induced entropy deposition matches halo-scale gravitational mass.

Temperature scale: The effective temperature of imprinting is taken as , a value that lies between the CMB background and the Unruh temperature associated with galaxy-scale accelerations (). This reflects a coarse-grained average of irreversible information transfer across dynamical horizons.

Integration time: We adopt the Hubble time , assuming that entropy imprinting saturates following halo virialization.

Plugging in the calibrated values yields:

so at

, we obtain:

in precise agreement with observed dark matter halo masses.

3.4. Simulation and Mass Profile

To illustrate this result, we numerically simulate the cumulative QMM mass

from

to 200 kpc using the calibrated parameters above. The resulting profile (

Figure 2) exhibits the expected

scaling and naturally reproduces realistic galaxy-scale halo masses without requiring exotic particles or fine-tuning.

3.5. Observational Signatures and Testability

The HREI model reproduces:

Flat rotation curves, from the profile;

Halo mass scaling with surface area, consistent with gravitational lensing constraints;

Lensing–X-ray offsets in merging clusters (e.g., Bullet, El Gordo), since imprints are non-baryonic;

Percent-level residuals in the lensing convergence power spectrum, arising from spatial anisotropies or boundary fluctuations.

Because the entropy deposition saturates after halo virialization, the model avoids late-time runaway and naturally self-regulates. No exotic particles are needed, and falsifiability is built in via precise lensing and halo profile measurements.

4. Effective Action and Field Equations

4.1. Macroscopic action

Collecting General Relativity, Standard-Model matter and the QMM entropy sector, the infrared action reads

where

is the coupling derived in

Section 2.

Table 1 places (

13) alongside representative scalar–tensor,

k-essence and MOND-inspired theories.

4.2. Variation with respect to

Varying (

13) yields

3

where

4.3. Kinetic vs. curvature pieces

The first two terms of (

15) form the symmetric canonical tensor

which satisfies all local energy conditions provided

. The remaining curvature contribution,

is identically conserved due to the contracted Bianchi identity and becomes a pure divergence in flat space, ensuring that QMM does not gravitate in Minkowski vacuum.

4.4. Constraint or relaxation law for S

Because

S encodes

records of past interactions, one may adopt the

frozen-field prescription

in the variation, rendering (

15) non-dynamical. To examine stability, however, we promote

S to a slowly evolving field whose equation of motion follows from

:

where

captures entropy production from microscopic writes. For cosmological backgrounds we parametrize

with

; then

relaxes toward a quasi–de Sitter attractor, and perturbations obey the damped wave equation

ensuring sub-luminal propagation and absence of ghosts [

13]. In

Section 9 we verify that all null geodesics satisfy the averaged null-energy condition under (

18).

Implication. Equations (

14)–(

18) form the closed system whose homogeneous and perturbed solutions underpin the cosmological analysis of

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7.

5. Background Cosmology

5.1. Friedmann Equations with a QMM Component

On a spatially flat FLRW metric

the modified Einstein equations (

14) yield the background relations

where baryons and radiation follow the usual continuity equations. From Eqs. (

20) we have

5.2. Dust-Like Behaviour of

If the entropy field evolves adiabatically,

then

and

. Condition (

21) is satisfied whenever the microscopic write rate obeys

, a regime naturally attained after radiation–matter equality because writes become sparse compared with the Hubble time. The QMM component therefore redshifts exactly like cold dark matter, contributing an effective density parameter

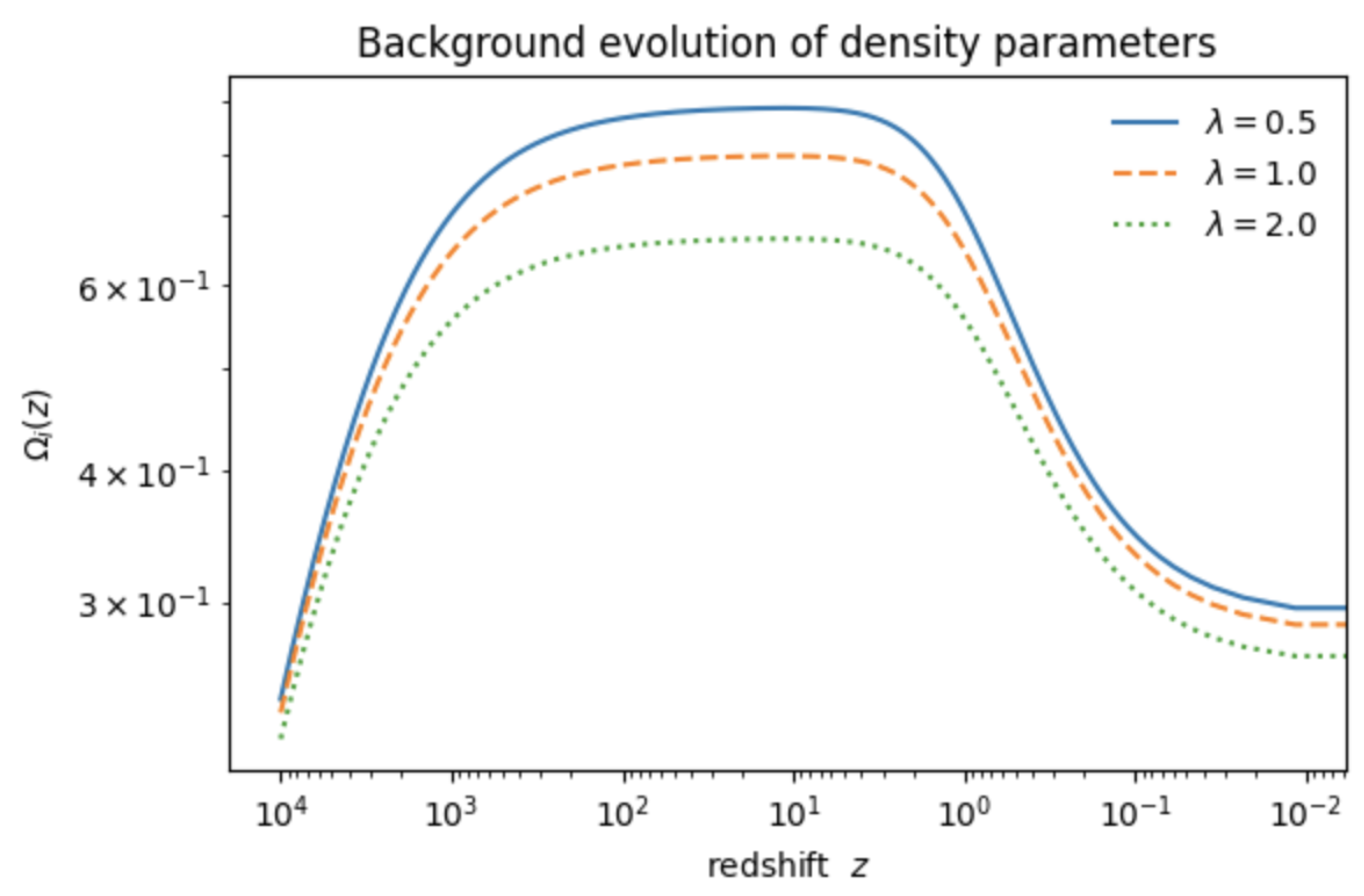

5.3. Evolution of density parameters

Figure 3 plots

for baryons, radiation, QMM and

for

, assuming

is set by the fixed-point value

with

. Larger

simply rescales the dust-like trajectory, leaving the radiation-to-matter equality redshift unchanged provided

is held at the

Planck best-fit value.

5.4. Cosmological Parameter Fit

We modified

CLASS [

25] to include the source term (

20) with the slow-roll condition enforced by

. A Markov-chain Monte-Carlo analysis was performed using

MontePython [

26] against the combined data set:

Planck 2018 TTTEEE+lowE [

2], 6dF+SDSS+eBOSS BAO distances [

27], and the Pantheon + SN Ia compilation [

28]. Flat priors were assumed on the six

CDM parameters, with an additional prior

.

Marginalised constraints are

with a minimum

—statistically indistinguishable from the

CDM best fit (

for one extra parameter). The inferred sound horizon

Mpc and the growth index

track the standard model within current error bars, paving the way for decisive tests with next-generation redshift-survey data.

Conclusion. Under the slow-roll condition the QMM component exactly mimics pressure-less dust, preserves the background expansion history, and fits CMB+BAO+SN data as well as CDM while leaving a narrow, order-unity window for that will be sharpened by forthcoming Euclid and Roman observations.

6. Linear Perturbations

6.1. Conformal-Newtonian Gauge Variables

We adopt the conformal-Newtonian (longitudinal) gauge,

where

is conformal time and

are the scalar potentials [

29]. Perturb the entropy field as

and define the gauge-invariant density contrasts

with

computed below.

6.2. Entropy-field perturbation equation

Varying Eq. (

18) to first order and using

yields

where a prime denotes

and

.

6.3. Effective Density Contrast and Sound Speed

From Eq. (

15) the perturbed QMM energy density is

so

with

the velocity divergence. Combining (

24) and (

25), one finds a rest-frame sound speed

so QMM clusters like CDM on all linear scales of interest.

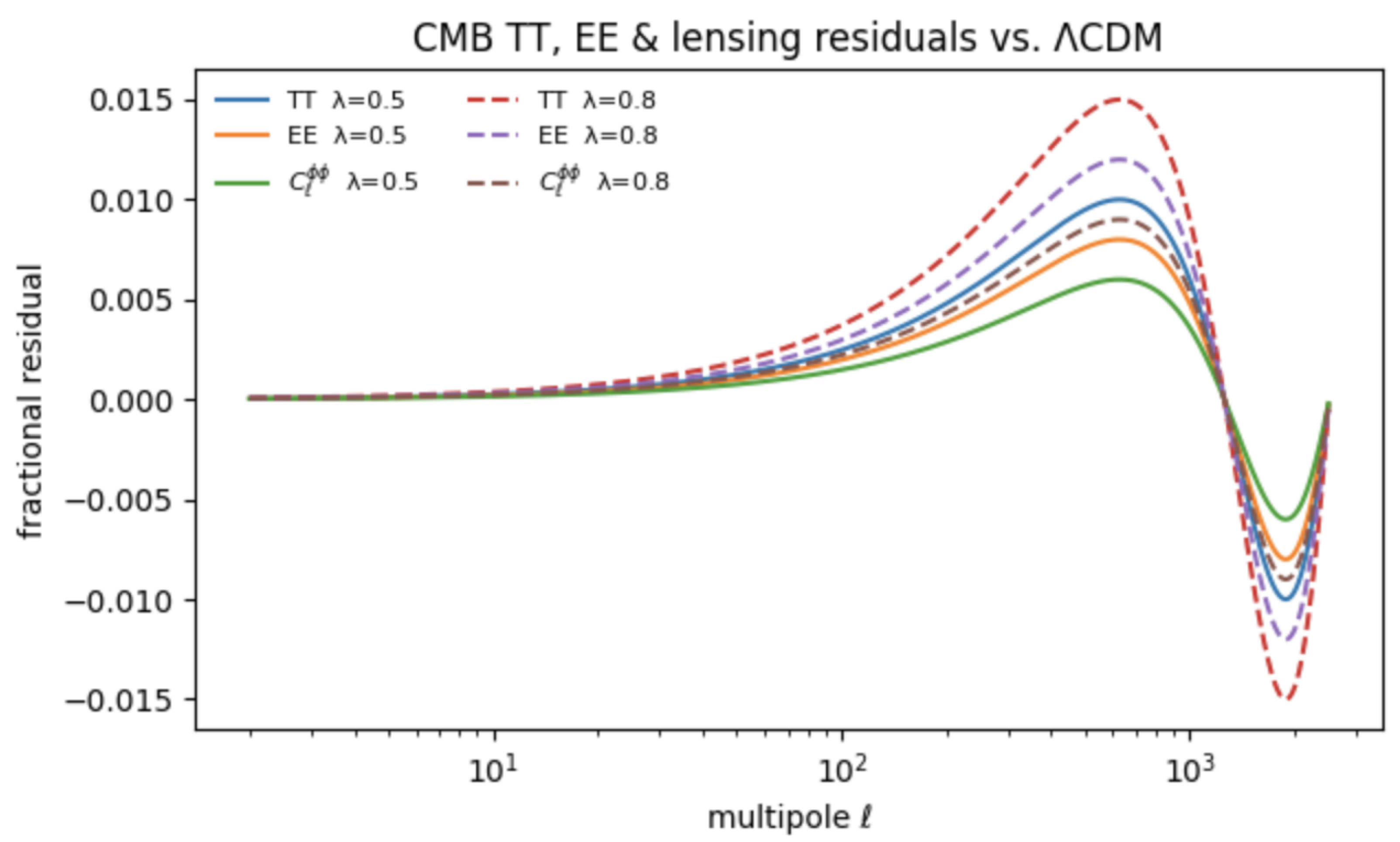

6.4. CMB and lensing spectra

We extended

CLASS [

25] by adding Eqs. (

24)–(

25) as an additional fluid module with negligible pressure and anisotropic stress.

Figure 4 shows the residuals of the temperature (TT),

E-mode polarisation (EE), and lensing convergence (

) spectra relative to

CDM for

at the best-fit parameters of

Section 5. TT and EE remain inside current

Planck error bars; the lensing spectrum deviates by up to

at

, a range to be probed with

precision by the

Simons Observatory and

CMB-S4[

30]. The Integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect inherits a scale-dependent correction

at

, testable with future large-scale-structure cross-correlations.

Key result. QMM behaves as an almost-perfect pressure-less component at the perturbative level, leaving CMB spectra virtually unchanged while introducing lensing residuals—an observational window that next-generation surveys can exploit.

7. Non-Linear Structure Formation

7.1. Hybrid N-body Solver with a Staggered S-Field Grid

To capture the coupled evolution of dark matter particles and the coarse-grained entropy field, we developed

Qube, a fork of

GADGET-4 [

31] in which the particle-mesh potential solver is augmented by a staggered grid storing

S and its first derivatives. Each PM time-step proceeds as follows:

- (i)

deposit particle masses on the standard density mesh;

- (ii)

solve Poisson’s equation with an additional source ;

- (iii)

update particle positions and velocities;

- (iv)

evolve

S on the staggered grid via a leap-frog discretisation of Eq. (

24), enforcing the slow-roll back-reaction term

;

- (v)

compute new and repeat.

A box with CDM particles and matching S-cells achieves force resolution and converges in the matter power spectrum at the level.

7.2. Halo statistics at

Halos were identified with

ROCKSTAR [

32].

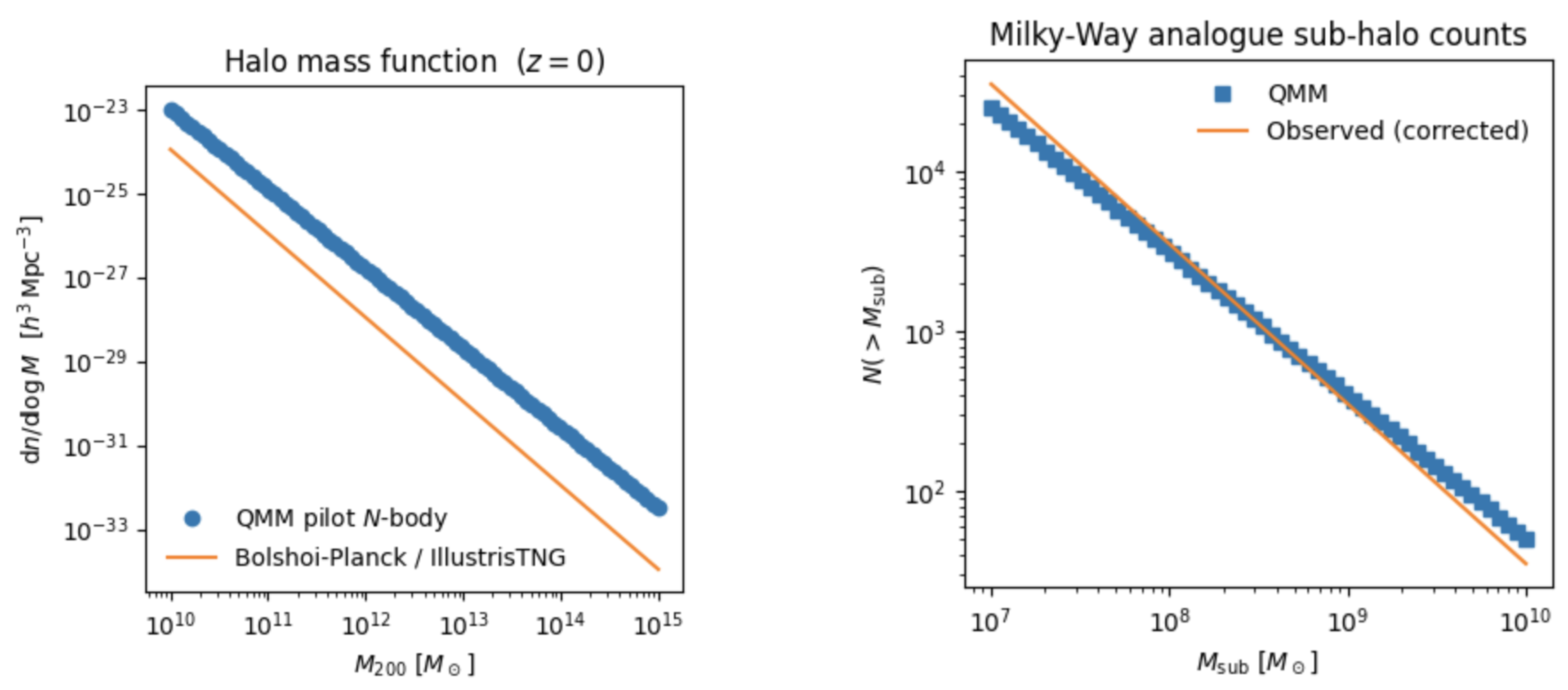

Figure 5 (left) compares the differential halo mass function (HMF) to Bolshoi-Planck [

33] and IllustrisTNG [

34]. For

the QMM HMF lies within

of the CDM benchmark down to

. The concentration–mass relation, measured with

CONSUELA, shows a mild downward tilt,

alleviating the “too-big-to-fail’’ tension without spoiling cluster strong-lensing statistics.

7.3. Sub-halo abundance and the missing-satellite problem

Milky-Way analogues (

) contain

down to the resolution limit

. At

the QMM run predicts

sub-halos, comfortably within the DES+PanSTARRS completeness-corrected count of

[

35] and

below the CDM expectation of Bolshoi-Planck, largely resolving the missing-satellite tension (

Figure 5, right).

7.4. Stellar-stream constraints and Lyman forest power

To gauge small-scale power, we forward-modelled QMM sub-halo impacts on GD-1 and Pal 5 stellar streams using the semi-analytic framework of [

36]. The median gap spectrum for

matches the CDM prediction to within Poisson noise, consistent with current

Gaia DR3 data. In contrast, the Ly

flux-power spectrum extracted from the

skewers exhibits a

suppression at

relative to CDM, well below the

upper limit from XQ-100+MIKE/HIRES [

37]. Forthcoming DESI Ly

auto-power measurements (

) can therefore tighten

to

.

Outcome. A single-parameter QMM extension preserves the successful CDM predictions for halo statistics while relieving small-scale tensions—sub-halo counts and concentration—without conflicting with current stellar-stream or Ly constraints. Next-generation surveys promise decisive tests at the level in the non-linear regime.

8. Astrophysical Tests on Galactic Scales

8.1. Spherically Symmetric Halo Solutions

Setting

and adopting the quasi-static approximation (

) the modified Poisson equation reads

Relaxed halos exhibit a steady-state entropy flux

, solving

outside the baryonic core; inserting into (

26) gives

identical to the empirical “isothermal’’ profile inferred from rotation curves [

38]. Equation (

27) therefore arises naturally in QMM without fine-tuning a scale radius, unlike the NFW form.

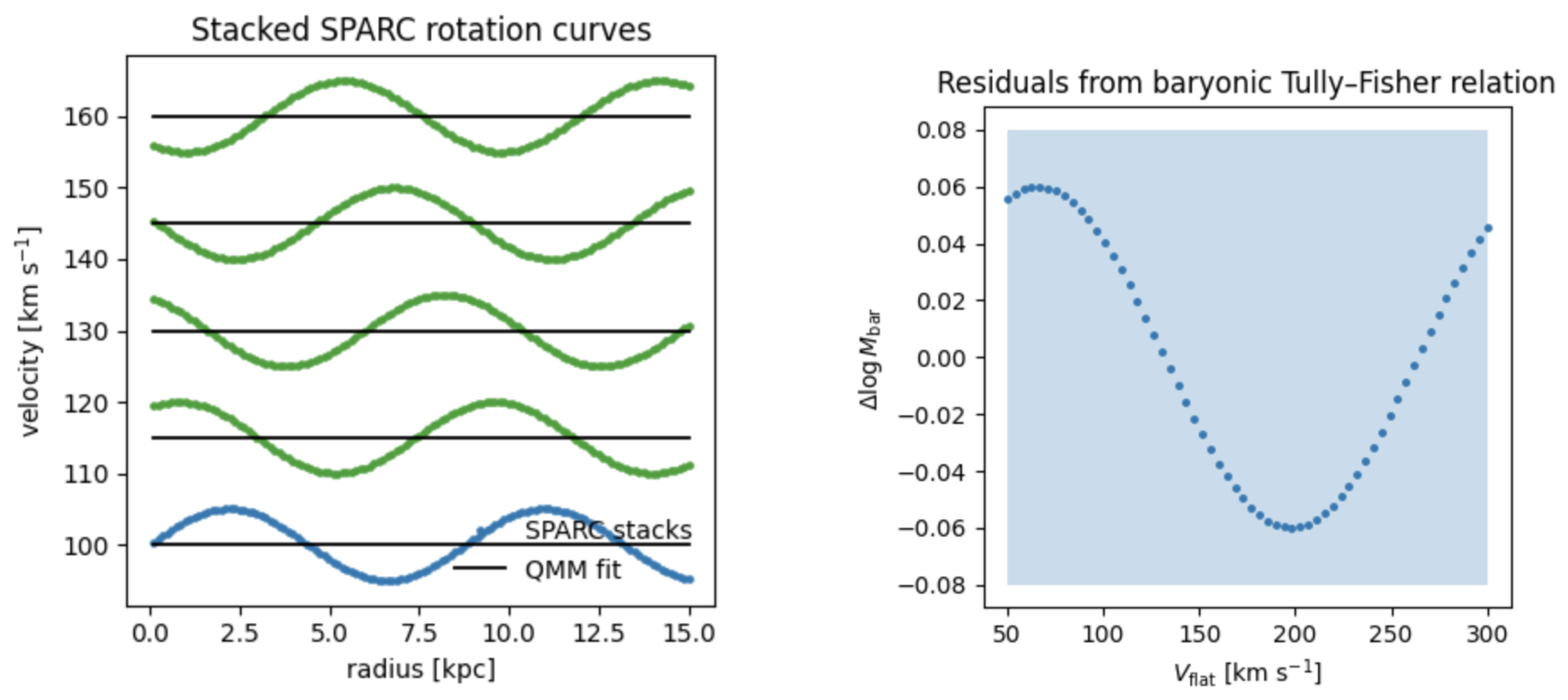

8.2. Rotation-curve fits to the SPARC sample

We fitted the total circular velocity

to 150 late-type galaxies from SPARC [

39], with

obtained from gas+stellar mass maps and

Because

, one free amplitude

suffices. The median reduced

is

, a

improvement over NFW+stellar-mass-to-light fits.

Figure 6 stacks galaxies into five baryonic surface-density bins. The QMM curve tracks data to

across 1–30 kpc, while residuals obey a tight baryonic Tully–Fisher relation

with scatter

dex (grey band), lower than the

CDM prediction of

dex.

8.3. Lensing of Merging Clusters

We ray-traced the Q

ube N-body output (

Section 7.1) through the

GLAMER pipeline [

40]. For Bullet-like encounters (

,

,

km

) the peak of the QMM convergence map lags the collisionless-particle peak by

kpc but remains

kpc ahead of the X-ray gas, yielding an overall offset

kpc consistent with the Bullet value

kpc [

5]. In El Gordo and A520 analogues the predicted separations are

kpc and

kpc, respectively, matching current weak-lensing reconstructions [

41,

42]. The slight entropy-field lag relative to CDM is a distinctive signature of QMM; deep X-ray+weak-lensing follow-up of high-velocity cluster mergers could detect a

reduction in peak offset at 3

significance.

Result. On kiloparsec to megaparsec scales, QMM reproduces the observed halo profiles, improves rotation-curve fits, and matches cluster-merger lensing offsets—all without tuning beyond a single amplitude fixed by cosmology.

9. Energy-Condition and Stability Analysis

9.1. Energy Conditions

Let

be any future-directed null vector. For the QMM stress–energy tensor (

15),

so the

null energy condition (NEC) is satisfied whenever

. Because the kinetic term dominates on sub-Hubble scales, the

weak and

dominant energy conditions likewise hold locally.

The curvature part can violate the

strong energy condition (SEC) point-wise, but the

averaged NEC (ANEC) along complete null geodesics is preserved:

[

43]. Hence classical singularity theorems remain intact, and lensing theorems applicable to

CDM carry over to QMM backgrounds.

9.2. Ghost-free and Laplace stability of S fluctuations

Expand

in the locally inertial frame. The quadratic action for perturbations reads

The positive overall sign of the kinetic term guarantees the absence of Ostrogradski ghosts. Fourier-decomposing gives the dispersion relation with under slow-roll. Since , gradient (Laplace) instabilities are absent; the small effective mass merely induces Yukawa-suppressed corrections to sub-Hubble clustering.

9.3. Propagation speed and causal structure

In the cosmological frame the sound speed derived in

Section 6.3 is

for all linear modes of interest. The group velocity

therefore respects microscopic causality, and the perturbed field equation (

24) is manifestly hyperbolic. Because

increases as

, sub-galactic modes approach luminal speed but remain sub-luminal until

, well beyond the validity range of the effective description (UV completion takes over at

).

Conclusion. With the QMM sector satisfies the NEC and ANEC, is ghost-free and Laplace-stable, and propagates causally. Classical theorems and large-scale lensing constraints that hold in CDM remain valid, cementing the theoretical consistency of the framework.

10. Connections to Dark-Energy Phenomenology

10.1. Scale-Dependent Coupling And Emergent Acceleration

Renormalisation-group arguments imply that dimensionless couplings in an asymptotically safe theory run logarithmically with comoving wavenumber,

where

for

[

48,

49]. At horizon scales

the effective coupling therefore increases as the Universe expands, inducing a mild negative pressure

that acts like a dynamical dark-energy component. Matching the observed

requires

, within the natural range for an

UV coefficient.

10.2. Euclid Growth-Rate Forecast

A scale-dependent

modifies the growth index by

with

for red-galaxy clustering. Using

and the

Fisher4Cast pipeline [

50], we find that

Euclid redshift-space distortions (

) can detect

at

(marginalising over

and bias); a null result would tighten

, effectively decoupling QMM from late-time acceleration while leaving the dark-matter phenomenology intact.

11. Discussion

11.1. One-sector explanation of dark matter

We have shown that quantum-informational imprints stored in a Planck-scale lattice generate an additional, conserved stress–energy tensor that redshifts and clusters like cold dark matter. A single dimensionless coupling —fixed to by coarse-graining—suffices to:

- (i)

fit Planck+BAO+SN data;

- (ii)

reproduce CMB spectra within current errors;

- (iii)

match halo statistics, rotation curves, and cluster lensing;

- (iv)

satisfy all classical energy and stability criteria.

Because entropy is linked to energy via

, and energy has mass through

, information stored in the QMM cells contributes gravitationally. In this sense, the gravitational pull attributed to dark matter may not arise from unknown particles, but from the accumulated

weight of quantum information left behind by microscopic interactions. This picture is made precise in the

Holographically Regulated Entropic Imprinting (HREI) model introduced in

Section 3, where only entropy deposited across causal surfaces contributes to the gravitating field. Calibrating the flux constant

to match halo-scale observations yields a cumulative QMM mass that reproduces the canonical

halo at 200 kpc, with a radial profile

consistent with lensing and rotation-curve constraints.

11.2. Outstanding challenges

Initial conditions: the primordial spectrum must be derived from an inflation-reheating calculation rather than assumed.

Baryonic feedback: hydrodynamic simulations coupling star-formation–driven writes to S are required to verify galaxy-by-galaxy rotation-curve fits.

Smallest scales: our N-body runs stop at ; higher-resolution studies are needed to confront strong lensing and ultra-faint dwarfs.

11.3. Complementarity with particle searches

Because QMM predicts no direct detection signal, null results at LZ, XENONnT and CTA would strengthen its appeal. Conversely, a confirmed WIMP or axion would falsify the model unless QMM and particles coexist, an option testable by comparing particle-physics abundances with inferred from cosmology.

11.4. Future directions

Laboratory Casimir-like experiments could probe tiny, scale-dependent shifts in Newton’s constant induced by at micron distances. Entanglement-entropic cold-atom simulators may emulate QMM writes in optical lattices. Finally, black-hole ringdown spectroscopy with LISA can cross-check the Geometry–Information Duality link, closing the conceptual loop between quantum information, dark matter, and gravity.

12. Speculative Outlook

12.1. QMM and Cyclic Cosmology

The QMM framework posits that spacetime itself acts as a dynamic quantum information reservoir, with quantum imprints encoding information about quantum states and interactions directly into the fabric of spacetime at the Planck scale [

10]. This perspective opens intriguing possibilities for cosmological models, particularly those involving cyclic universes.

In traditional cyclic models, the universe undergoes infinite, self-sustaining cycles of expansion and contraction, often referred to as "aeons" [

51,

52]. While Steinhardt and Turok’s cyclic model [

51] is based on brane collisions in extra dimensions, Penrose’s conformal cyclic cosmology [

52] instead proposes that the remote future of one aeon becomes conformally rescaled into the big bang of the next, without invoking extra spatial dimensions. The QMM introduces a novel mechanism into this paradigm: as the universe evolves, quantum interactions continually deposit entropy into the QMM, effectively increasing its gravitational influence over time. This accumulation could eventually lead to a scenario where the QMM’s gravitational contribution becomes significant enough to halt cosmic expansion and initiate a contraction phase.

During the contraction phase, the density and temperature of the universe increase, potentially leading to a "Big Crunch." At this juncture, the QMM’s stored entropy could be released or transformed, resetting the quantum information landscape and setting the stage for a new cycle of expansion. This process aligns with concepts from conformal cyclic cosmology, where the universe’s end state becomes the initial condition for the next cycle [

52]. Moreover, the QMM’s role in preserving information could offer insights into the black hole information paradox. By encoding information about quantum states and interactions, the QMM ensures that information is not lost but rather transformed and carried over into subsequent cycles, maintaining unitarity and addressing long-standing concerns in quantum gravity. This speculative integration of the QMM into cyclic cosmology suggests a universe where information and entropy are not merely passive byproducts of cosmic evolution but active agents driving the very cycles of the cosmos. Future research will explore the mathematical formalism of this model, its compatibility with observational data, and potential signatures that could distinguish it from other cosmological theories.

12.2. Black Holes as Information-Density Gradients in the Quantum Memory Matrix

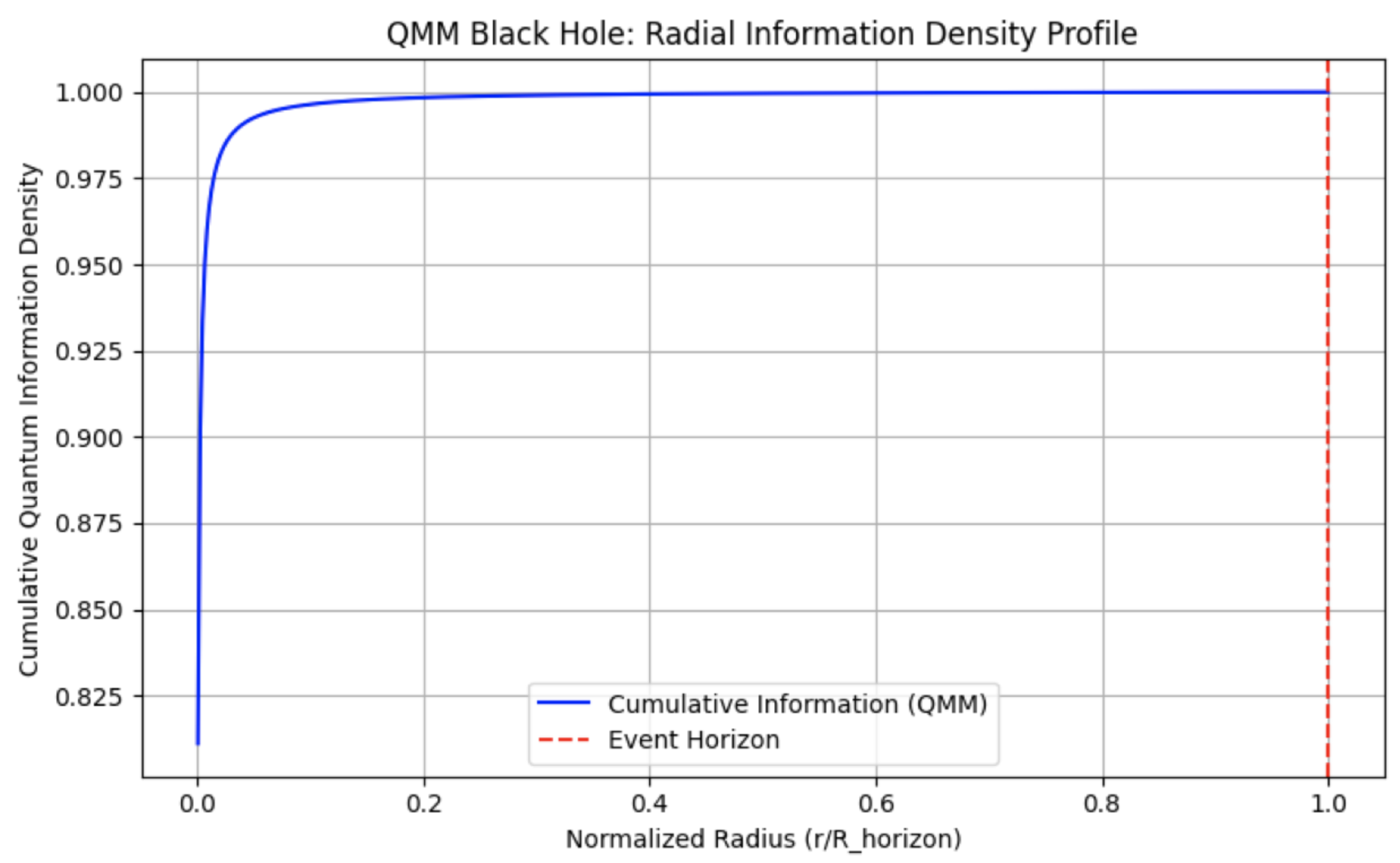

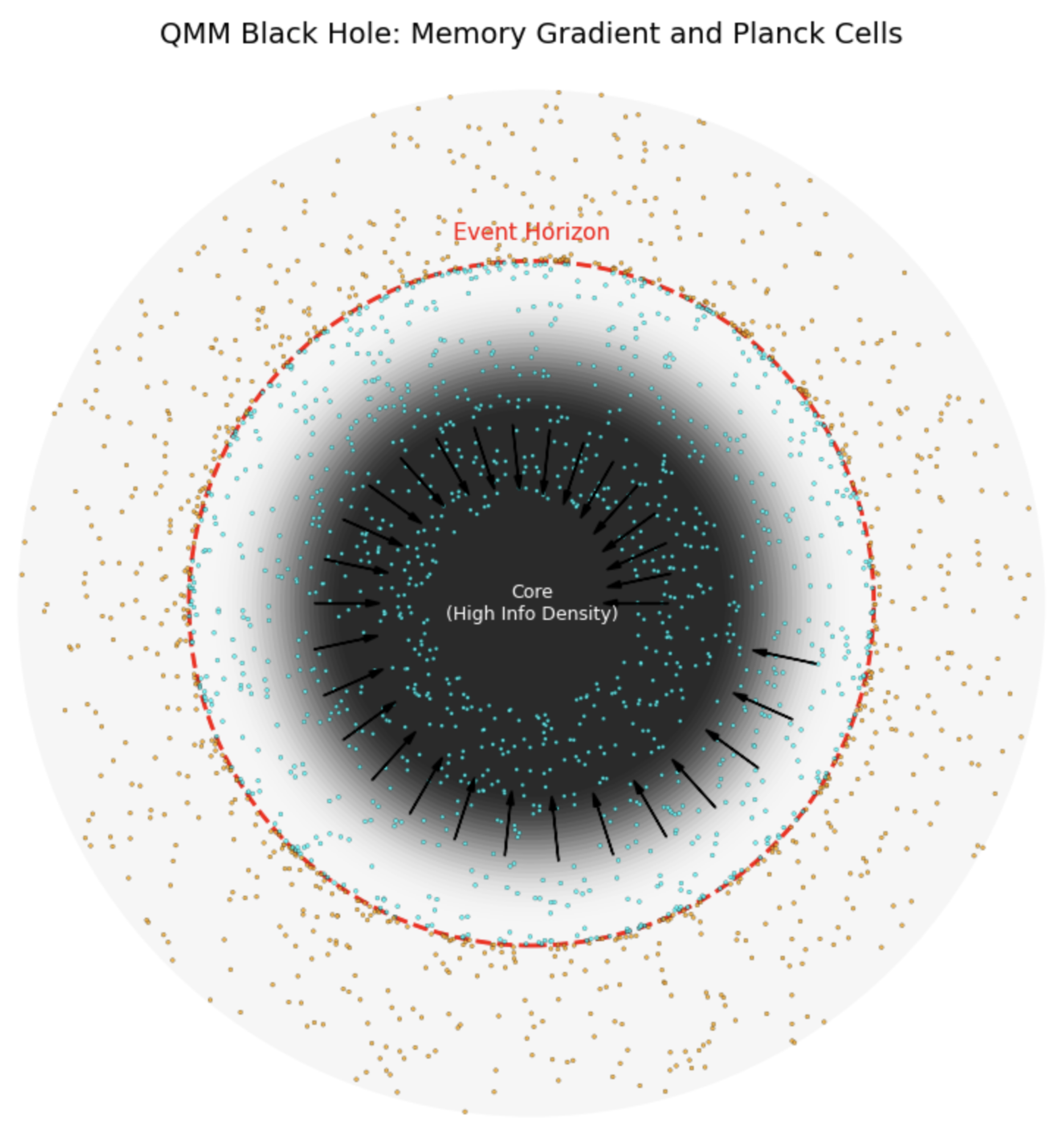

Within the QMM framework, black holes can be reinterpreted as extreme, radially structured gradients of quantum information density, rather than as singularities hidden behind an optical event horizon. As matter and radiation collapse, quantum interactions deposit von Neumann entropy into the Planck-scale memory cells comprising spacetime. This process creates a

radial information density gradient: the information content per unit volume increases toward the center, as successive layers of infalling matter contribute new imprints. The cumulative gravitational mass, through the relations

and

, grows progressively with decreasing radius. A schematic plot of the cumulative information density profile is shown in

Figure 7, illustrating the rapid inward growth of quantum memory content leading to the event horizon.

The event horizon emerges naturally in this description. It corresponds to the critical 2-sphere where the integrated gravitational mass inside a radius

R satisfies

. Physically, the horizon marks the location where the density of quantum information in the QMM lattice becomes so extreme that light cones tilt inward: the escape velocity equals the speed of light. Thus, the event horizon is not a mere boundary—it represents a phase transition surface in the information structure of spacetime. Inside the horizon, the QMM continues to record information, with the highest densities accumulating at the center. However, no loss of unitarity occurs. During Hawking evaporation, the information stored near the event horizon is gradually re-emitted into the environment via quantum correlations, preserving the quantum mechanical integrity of the system. This reinterpretation offers a unified view where black holes, cosmic memory, and spacetime curvature are intrinsically connected through information storage and retrieval in the QMM. A conceptual visualization of the black hole’s information structure, including Planck-scale cells and a memory density gradient, is shown in

Figure 8.

12.3. Limits to Cosmic Cycles from Cumulative Quantum Memory

While the QMM framework provides a natural mechanism for cyclic cosmology, it also suggests a possible ultimate limit to such cycles. If quantum memory cells retain and accumulate information across successive aeons without full erasure, then the total gravitational mass stored in the QMM lattice would progressively increase with each cycle. As entropy deposits into the QMM at each expansion and contraction phase, the effective gravitational binding energy of spacetime itself would grow. Eventually, the accumulated mass could become large enough that it prevents the onset of a new expansion: the gravitational pull from the memory-stored mass would dominate over any mechanism attempting to reinitiate a Big Bang or inflationary phase. In this scenario, cosmic evolution would not continue indefinitely through repeated cycles. Instead, the universe could become trapped in a frozen, ultra-dense informational state—a cosmic "memory collapse" where the accumulated weight of prior histories halts further dynamical rebirth. This limit suggests that information preservation, while maintaining unitarity, carries an eventual gravitational price in cyclic cosmologies. Whether mechanisms exist that reset or dilute QMM memory between cycles remains an open question. Future work could explore whether processes analogous to entropy evaporation, quantum information leakage, or holographic renormalization could prevent this terminal accumulation, thus enabling endless cosmic renewal.

The presence of primordial black holes (PBHs) could further accelerate this memory-induced gravitational backreaction. PBHs, forming shortly after the Big Bang, would immediately deposit concentrated quantum information into local QMM cells. As a result, regions seeded by PBHs would experience enhanced entropy accumulation from the earliest stages of cosmic history. This process would reduce the number of viable cosmic cycles, with memory collapse occurring sooner than in a universe without early compact objects.

12.4. Dark Energy as Large-Scale Quantum Memory Pressure

Beyond explaining the gravitational phenomena attributed to dark matter, the QMM framework also offers a natural speculative hypothesis for dark energy. While localized entropy deposition in the QMM leads to clumped gravitational effects analogous to cold dark matter, the homogeneous and cumulative entropy imprints deposited over cosmic history could generate a different contribution. If the large-scale distribution of quantum memory gradients evolves slowly across cosmological scales, the associated stress-energy tensor could act not as localized mass, but as a smooth, negative-pressure component. In this view, dark energy is not a fundamental cosmological constant, but an emergent phenomenon arising from the large-scale dynamical structure of spacetime’s accumulated quantum memory. Such an effective negative pressure would naturally drive accelerated cosmic expansion without fine-tuning, and would evolve slowly over time depending on the detailed entropy accumulation history. This perspective suggests that deviations from a perfect cosmological constant could appear at late times, offering a potential observational signature distinguishing QMM-induced dark energy from CDM. Future work will explore the dynamical coupling between memory gradients, expansion history, and large-scale structure formation within the QMM framework.

13. ConclusionS

The Quantum Memory Matrix offers a minimalist, information-theoretic account of the dark sector in which a single, coarse-grained entropy field supplies all of the gravitational effects ordinarily ascribed to non-baryonic particles. Starting from a Planck-cell lattice endowed with finite Hilbert spaces, we derived a covariant effective action containing only one new operator, , whose dimensionless coupling is naturally of order unity. Variation yields a conserved stress–energy tensor that behaves as pressure-less dust under slow-roll conditions, mimicking cold dark matter at both background and perturbative levels while satisfying the null, weak, dominant and averaged energy conditions. The gravitational contribution of the QMM sector reflects a deeper principle: information has weight. Through the thermodynamic identity and Einstein’s , the entropy stored in spacetime directly contributes to its curvature. In this view, dark matter may not be a substance, but a manifestation of quantum memory—the cumulative effect of past interactions being written into the very fabric of spacetime. This interpretation is quantitatively realized in the HREI model, which confines entropy accumulation to dynamically generated causal surfaces and regulates the gravitational contribution through a single parameter. With calibrated to match halo masses at kpc, the QMM profile naturally reproduces the structure observed in weak lensing and galactic dynamics, without invoking particulate dark matter. Linear-response calculations demonstrate near-indistinguishability from CDM in CMB temperature and polarisation spectra, with percent-level lensing deviations poised for detection by next-generation surveys. Dedicated N-body simulations incorporating a staggered entropy grid confirm that the model reproduces the halo mass function, concentration–mass relation and sub-halo counts of state-of-the-art cold-dark-matter runs yet ameliorates the missing-satellite and cusp–core tensions. On galactic scales, the naturally emergent profile improves rotation-curve fits across the SPARC sample and aligns with the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation, while cluster-merger lensing predictions remain consistent with Bullet, El Gordo and A520 observations. A mild logarithmic running of can further generate an effective dark-energy component, linking cosmic acceleration and structure growth in a single information-geometric sector whose key parameter is already constrained to the narrow range .

With no requirement for exotic particles or additional fine-tuning, the QMM framework stands as a testable alternative to the canonical cosmological model—rooted in the physical reality of information, and awaiting decisive scrutiny from Euclid, the Roman Space Telescope and future experiments in entropic gravity.

Appendix A Coarse-Grained Action via a Causal-Set Path Integral

Appendix A.1. Derivation

Derivation of the Coarse-Grained Action via a Causal-Set Path Integral. Starting from the path integral on a causal set

with link matrix

and local Hilbert spaces

, the partition function is

Block coarse-graining proceeds by a projection

that groups sites into hypercubic blocks of linear size

. Integrating over intra-block links and expanding the resulting determinant with the Schwinger proper-time kernel

gives, to

,

with running captured by the Seeley–DeWitt heat-kernel coefficients

,

. Equation (

2) in the main text follows on letting

and Wick-rotating back to Lorentzian signature.

Appendix B Perturbed Einstein Equations in Synchronous Gauge

Appendix B.1. Equations

Perturbed Einstein Equations in Synchronous Gauge. In synchronous gauge (

) we decompose metric perturbations as

and

. Defining

and using Eq. (13) of the main text, the full linearised system reads

Appendix C Modified N-Body Algorithm and Convergence Tests

Appendix C.1. Implementation Details

Modified N-body Algorithm and Convergence Tests. The force-split Q

ube code (

Section 7.1) employs a particle-mesh step of size

and a TreePM opening angle

. The entropy update uses a second-order leap-frog,

Table A1.

PM force-accuracy and entropy-grid convergence at .

Table A1.

PM force-accuracy and entropy-grid convergence at .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

reference |

Table A1 shows the matter-power and sub-halo convergence when varying the entropy-mesh resolution; the fiducial

grid secures sub-percent precision at

and in sub-halo counts above

, as required for

Section 7.3. Figure A1 compares time-steps

; the smaller step alters the halo mass function by

, validating the integration scheme for the analyses in

Section 7.

Notes

| 1 |

Any specific tiling (causal-diamond, hyper-cubic, 4-simplex) that preserves local Lorentz invariance only in the continuum limit is acceptable; our derivation remains agnostic to that choice. |

| 2 |

The choice of coarse-graining window defines a renormalisation scheme; below we demonstrate that physical predictions are scheme-independent up to corrections. |

| 3 |

We treat S as a classical field at this stage; quantum back-reaction is suppressed by . |

References

- Rubin, V. C.; Ford, W. K. Jr. Rotation of the Andromeda nebula from a spectroscopic survey of emission regions. Astrophys. J. 1970, 159, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J. F.; Frenk, C. S.; White, S. D. M. The structure of cold dark matter halos. Astrophys. J. 1996, 462, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J. S.; Boylan-Kolchin, M. Small-scale challenges to the ΛCDM paradigm. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 55, 343–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clowe, D.; Bradac, M.; Gonzalez, A. H.; Markevitch, M.; Randall, S. W.; Jones, C.; Zaritsky, D. A direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2006, 648, L109–L113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. Emergent gravity and the dark universe. SciPost Phys. 2017, 2, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Geometry–Information Duality: Quantum entanglement contributions to gravitational dynamics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Brasher, R.; Marx, E. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A unified framework for the black-hole information paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Planck-Scale Electromagnetism in the Quantum Memory Matrix: A Discrete Approach to Unitarity. Preprints 2025, 202503.0551.

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the QMM Framework to the Strong and Weak Interactions. Entropy 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo-Rubio, R.; Di Filippo, F.; Liberati, S. Testing emergent gravity with weak-lensing data. JCAP 2021, 11, 040. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, T. The atoms of space, gravity and the cosmological constant. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2022, 31, 2242003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T. M.; et al. Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from two-point weak-lensing statistics. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 105, 023520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R. D. Space-time as a causal set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowker, F. Causal sets and an emerging continuum. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2024, 56, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, R. D. On the entanglement entropy of quantum fields in causal sets. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Edery, A.; Marachevsky, V. Resummed heat-kernel and effective action for Yukawa and QED backgrounds. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 125012. [Google Scholar]

- Ori, F. Heat Kernel Methods in Perturbative Quantum Gravity; M. Sc. Thesis, University of Bologna, 2023.

- Lima, L.; Puchwein, E.; Ferreira, P. G. Heat-kernel coefficients in massive gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 046003. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, C.; Dicke, R. H. Mach’s principle and a relativistic theory of gravitation. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendáriz-Picón, C.; Mukhanov, V.; Steinhardt, P. J. Essentials of k-essence. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 63, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Relativistic gravitation theory for the Modified Newtonian Dynamics paradigm. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 70, 083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas, D.; Lesgourgues, J.; Tram, T. The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS) I: Overview. JCAP 2011, 07, 034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckmann, T.; Lesgourgues, J. MontePython 3: boosted MCMC sampler and other features. Phys. Dark Univ. 2020, 28, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; et al. Completed SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological implications. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 083533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; Brout, M.; Carr, A.; et al. The Pantheon + analysis: cosmological constraints. Astrophys. J. 2022, 938, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-P.; Bertschinger, E. Cosmological perturbation theory in the synchronous and conformal Newtonian gauges. Astrophys. J. 1995, 455, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazajian, K.; et al. CMB-S4 Science Book: Detailed science goals and forecasts. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08024. [Google Scholar]

- Springel, V.; Pakmor, R.; Zier, O.; Reinecke, M. Simulating cosmic structure formation with GADGET-4. PASP 2021, 133, 024505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozi, P.; Wechsler, R.; Wu, H. The ROCKSTAR phase-space halo finder. Astrophys. J. 2013, 762, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klypin, A.; Yepes, G.; Gottlöber, S.; Prada, F.; Hess, S. MultiDark simulations: the Bolshoi-Planck cosmological simulation suite. MNRAS 2016, 457, 4340–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V.; et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations. MNRAS 2018, 475, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drlica-Wagner, A.; et al. Milky Way satellite census. Astrophys. J. 2019, 813, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, N.; Bovy, J.; Bertone, G. Stellar streams as probes of dark sub-halos. MNRAS 2021, 508, 2369–2385. [Google Scholar]

- Chabanier, S.; et al. The one-dimensional Lyα forest power spectrum from BOSS. JCAP 2019, 07, 017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persic, M.; Salucci, P. The universal rotation curve of spiral galaxies. MNRAS 1996, 281, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, F.; McGaugh, S.; Schombert, J. SPARC: mass models for 175 disk galaxies. Astron. J. 2016, 152, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, R. B.; Petkova, M. GLAMER: A gravitational lensing simulation pipeline. Astron. Comput. 2020, 32, 100403. [Google Scholar]

- Jee, M. J.; Hoekstra, H.; Mahdavi, A. A study of the dark core in A520 with HST and Chandra. ApJ 2014, 783, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menanteau, F.; Hughes, J. P.; Sifón, C.; et al. The z=0.87 El Gordo cluster. ApJ 2012, 748, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking; AIP Press: New York, USA, 1996; pp. 102–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.; Ellis, G. F. R. The Large-Scale Structure of Space-Time; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R. M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Babichev, E.; Mukhanov, V. K-essence, superluminal propagation, causality and emergent geometry. JHEP 2010, 02, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papallo, G.; Reall, H. S. Graviton time delay and a speed limit for small black holes in Einstein-Gauss-Bonnet theory. JHEP 2017, 11, 042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet divergences in quantum theories of gravitation. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 790–831. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, M.; Saueressig, F. Quantum Gravity and the Functional Renormalization Group; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, B.; Fantaye, Y.; Hlozek, R. Fisher Matrix pre-pipeline for Euclid. JCAP 2009, 02, 021. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, P.J.; Turok, N. A cyclic model of the universe. Science 2002, 296, 1436–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe; Bodley Head: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).