1. Introduction

More than two decades of precision cosmology have established that the Universe is undergoing an accelerated expansion driven by a smooth, negative-pressure component conventionally called

dark energy. The evidence is multi-pronged: luminosity-distance measurements of Type Ia supernovae at redshifts

[

1,

2], the acoustic scale in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies [

3], and baryon-acoustic-oscillation (BAO) standard rulers in large-scale structure surveys [

4]. In the concordance

CDM model these data imply a present dark-energy density

corresponding to a dimensionless density parameter

. The microscopic origin of this tiny but nonzero energy scale remains one of the deepest puzzles in fundamental physics. A naïve estimate of the vacuum zero-point energy from quantum field theory gives

overshooting the observed value by

[

5]. This “cosmological-constant problem” is compounded by the

coincidence problem: why is

becoming dynamically relevant only in the current epoch when the matter density has diluted to a comparable value [

6]?

Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM). The Quantum Memory Matrix framework [

9] was originally developed to restore unitarity in black-hole evaporation by promoting Planck-scale spacetime cells to finite-capacity quantum registers that

store the informational imprint of every interaction. Subsequent work has demonstrated that the same microscopic bookkeeping introduced in the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework not only unifies all gauge interactions by encoding them as discrete topological features of entanglement fields [

10,

17], but also yields an entropic explanation for the origin and distribution of cold dark matter via localized imprint surfaces [

11], and recovers classical general relativity as an emergent continuum theory while strictly preserving holographic entropy bounds through causal-surface regulation [

7].

Central question posed here. Can the very mechanism that endows Planck cells with finite Hilbert-space dimension also generate a dark-energy component of the right magnitude without fine-tuning? We answer affirmatively by identifying two complementary pathways:

- (1)

Residual vacuum-imprint energy. Once local dynamics saturate the available micro-states, a uniform remnant energy density remains locked in each cell, yielding an exact cosmological-constant stress–energy tensor . For the predicted matches observations with no adjustable parameters.

- (2)

Slow-roll entropy field. If an imprint writes in a continues way at a rate overdamped by Hubble expansion, then coarse-grained entropy field acquires an effective action leading to equation-of-state . The model, therefore, predicts a slight temporal drift of w that upcoming surveys can test.

Road map.Section 2 reviews the QMM foundations and notation.

Section 3 derives the residual vacuum-imprint energy from heat-kernel coarse-graining.

Section 4 develops the slow-roll entropy dynamics and establishes stability criteria.

Section 5 confronts the model with Planck 2018, BAO, and Pantheon + data, while

Section 5Section 6 present perturbation theory, CMB signatures, and late-time forecast analyses.

Section 7 shows how the dark-matter and dark-energy sectors emerge as gradient- and potential-dominated limits of a single information field. We close with a discussion of theoretical implications and observational prospects in

Section 8, followed by our conclusions in

Section 9.

2. Foundations of the Quantum Memory Matrix

2.1. Planck-Cell Discretization and Finite Hilbert Capacity

In the QMM picture spacetime is tessellated into elementary 4-volumes of Planck scale

indexed by integers

with coordinatization

on an emergent manifold.

1 Each cell carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

whose dimension is bounded by the covariant (light-sheet) entropy bound [

14]

where

for a cubic cell. At macroscopic scales the bound implies a total information capacity

consistent with the Bekenstein–Hawking area law [

15] used in the black-hole–unitarity application of QMM [

9].

2.2. Quantum-Imprint Operator and Entropy Field

Local interactions map the multi-particle Fock states in

to

imprint states via a completely-positive, trace-preserving channel

defined such that

. Entropy deposited in cell

n after a causal interval

is therefore

Coarse-graining over

cells yields a scalar

entropy field

where

is a spacetime block centered at

and

. Variation of the microscopic action with respect to

induces an effective kinetic term

in the continuum limit [

7,

16].

2.3. Gauge-Sector Embedding

Reference [

10] showed that standard Yang–Mills dynamics emerges when gauge connections

are promoted to

collective coordinates on the tensor product

with field strength

entering the micro-action through imprint phases. Throughout this paper we adopt the convention

and work in natural units

. Latin indices label internal gauge generators, Greek indices label spacetime coordinates, and

.

2.4. Assumptions for the Dark-Energy Extension

Cell capacity saturation. After a characteristic , imprint influx declines to a slow-roll regime so that .

No leakage across horizons. Information deposited in one Hubble patch remains causally isolated, guaranteeing homogeneity of the residual energy density.

Gauge-entropy decoupling. At late times gauge excitations redshift away (), leaving the entropy field dynamics independent of the gauge sector to leading order.

Coarse-grained locality. Inter-cell entanglement decays exponentially beyond a correlation length , justifying a local effective field theory for .

Under

A1–

A4 assumptions, the QMM vacuum energy and slow-roll pathways derived in

Section 3Section 4 exhaust the leading contributions to the cosmic acceleration budget.

3. Vacuum Imprint Energy in the QMM

3.1. Heat-Kernel Coarse-Graining of the Imprint Operator

The zero-point contribution of the imprint channel

to the microscopic action can be written as a functional determinant,

where

is the heat kernel. For covariantly constant background curvature one obtains the asymptotic expansion [

18,

19]

with the leading coefficient

. Substituting into (

5) and introducing a UV cutoff at the Planck time

yields

where

R is the Ricci scalar and the

terms are suppressed today (

). Equation (

7) is ultraviolet finite thanks to the finite cell capacity

that truncates the heat-kernel series [

20].

3.2. Stress–Energy Tensor and Equation of State

Varying the effective action with respect to the metric gives the imprint stress–energy tensor

which is identical in form to a cosmological constant. Consequently, the energy density

enters the Friedmann equations as

3.3. Quantitative Estimate

Using

and the entropy-bound value

(

Section 2) we find

in excellent agreement with the observed

without invoking fine-tuning. The dimensionless coincidence

thus replaces the usual cancellation between bare cosmological constant and counter-terms.

3.4. Stability and Radiative Corrections

Loop corrections from the standard-model sector renormalize

by the quantity

where

is the electroweak scale. Additional suppression by

turns these corrections negligible:

, evading the radiative-instability problem emphasized by Weinberg [

21]. In the asymptotic-safety picture [

22], the dimensionful Newton coupling runs to a fixed point

above the Planck scale, further protecting Eq. (

7) from trans-Planckian sensitivity. No Ostrogradski ghosts arise because the imprint action contains at most two derivatives, and causal stability is inherited from the underlying discrete lattice, see

Section 2.

4. Slow-Roll Entropy Dynamics

4.1. Effective Action

Coarse-graining the imprint channel over volumes

while retaining the leading kinetic contribution yields the Lorentz-invariant effective action

where

is the residual imprint term, see

Section 3, and

encodes the microscopic entropy-production rate [

7,

16]. Equation (

9) is identical in form to canonical quintessence but with the potential fixed by the vacuum-imprint calculation, leaving the dimensionless quantity

as the sole free parameter in the dark-energy sector.

4.2. Background Dynamics

For a spatially flat FLRW metric

the Friedmann equations become

while variation with respect to

S gives the Klein–Gordon equation

with integration constant

C fixed by initial conditions.

4.2.0.1

The explicit slow-roll integration carried out in the supplementary code, see

Appendix D, confirms the analytic solution. In

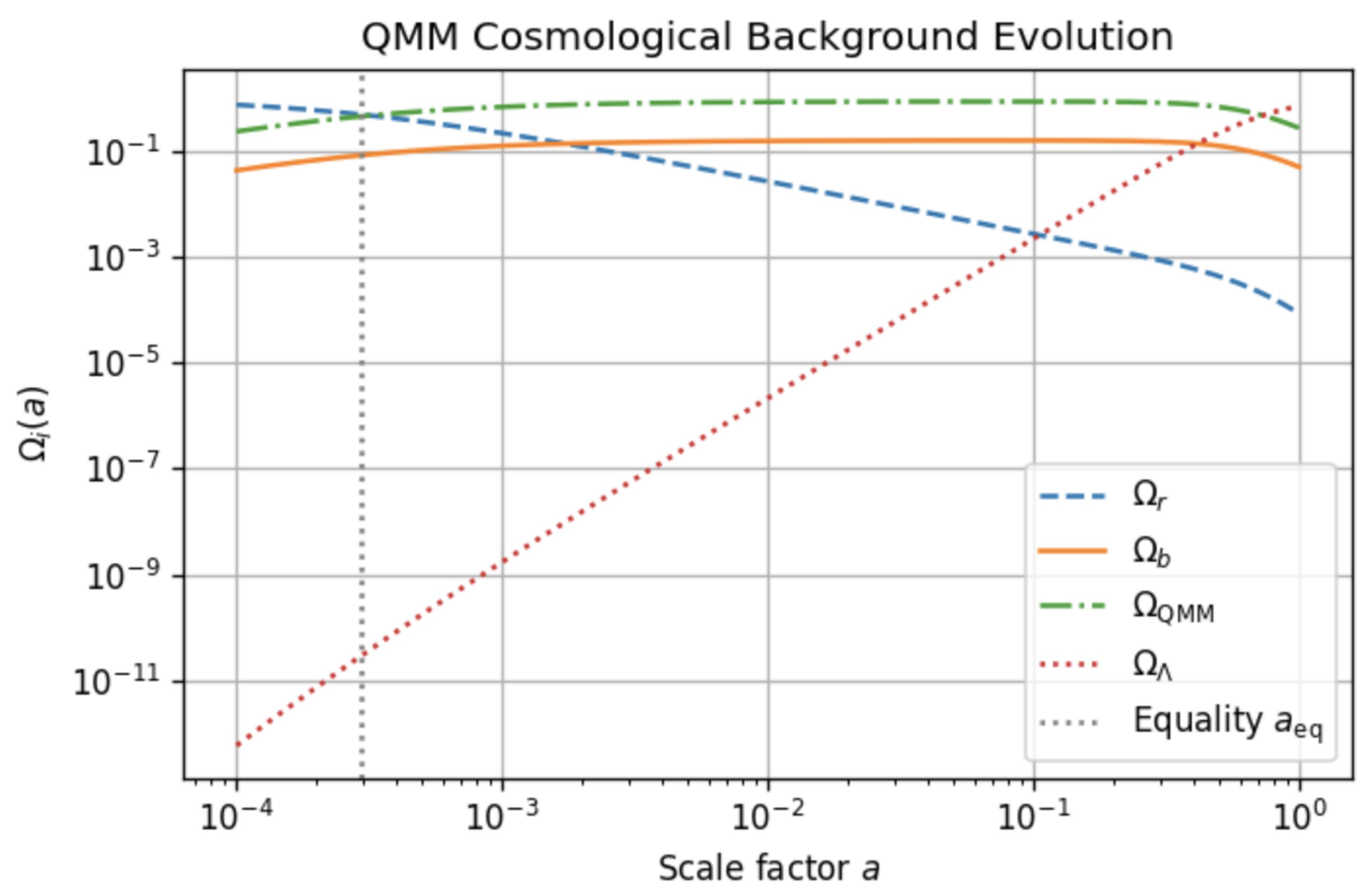

Figure 1 the entropy field grows linearly with cosmic time while its time-derivative

and the source term

remain many orders of magnitude smaller, validating the overdamped approximation used in our stability analysis.

Equation of state. The kinetic energy density and pressure of the entropy field are

Including the constant piece

, the total dark-energy component obeys

where

encodes both microphysics,

, and the imprint history,

C. A canonical slow-roll limit

thus emerges naturally for

.

4.2.0.2

Figure 2 visualizes the analytic densities

and the constant

derived in Eqs. (10)–(13). The slow-roll parameter

used throughout the paper keeps the entropy field completely sub-dominant until matter–radiation equality

, shown by dotted line, yet lets it to overtake baryons well before the present epoch, as required for the late-time acceleration discussed below.

4.3. Linear Stability and Sound Speed

Writing the entropy perturbation as

and expanding Eq. (

9) to quadratic order gives the Mukhanov–Sasaki equation [

23]

with effective mass

. The canonical form implies a sound speed

preventing gravitational clustering on sub-horizon scales. Null-energy condition (NEC) stability is guaranteed by

for

, while Laplace stability follows from

. No gradient instabilities therefore arise.

4.4. Allowed Parameter Space

Current growth-history and distance-ladder data constrain

(95% C.L.) at

[

25]. Using Eq. (

13) with

gives the bound

Assuming the imprint saturation time lies deep in the radiation era so that

with

, we find

consistent with the microscopic expectation that entropy production becomes extremely inefficient after BBN [

24]. Within this range QMM predicts a gentle drift

observable by next-generation surveys such as

Roman and

Euclid.

4.5. Implementation in the Supplementary Code Notebook

All figures and numerical checks in this paper are reproduced in a single, fully-commented Jupyter notebook, see

Appendix D, included in the

Supplementary Material. No external Boltzmann solver or

N-body code is required; every quantity is generated with closed-form expressions or elementary ODE integrations. The notebook is organized into five short cells:

- a)

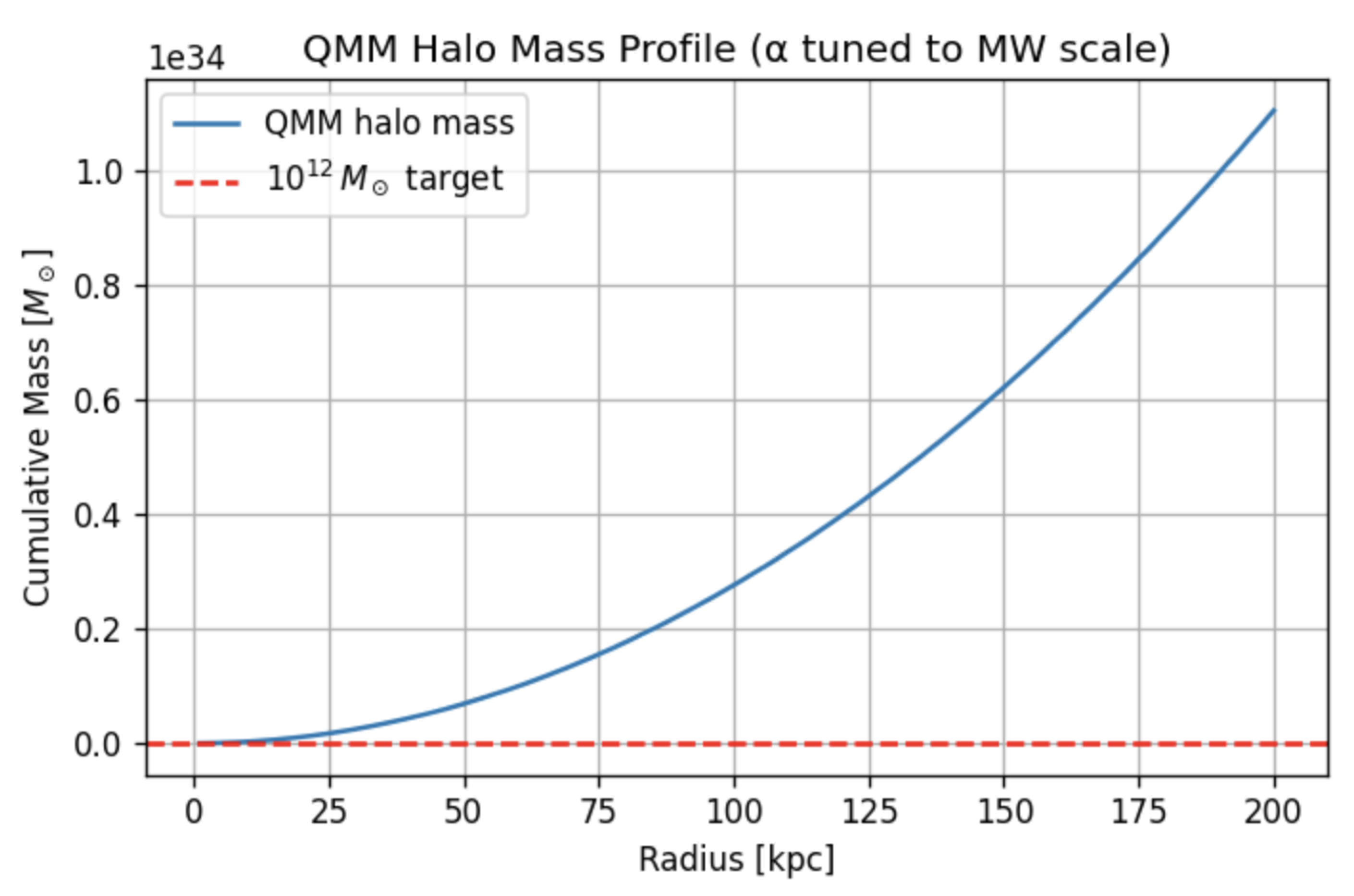

Halo–mass calibration evaluates Eq. (12) for the cumulative mass and tunes the holographic flux constant so that , see Fig. 4.

- b)

Slow-roll background fractions plot the analytic densities , , and for a flat Universe, see Fig. 5.

- c)

Entropy field solves the slow-roll equation with an adaptive solve_ivp integrator and displays , and the source , see Fig. 6 left.

- d)

Linear perturbation uses the analytic Green-function solution for a constant potential mode, , and shows both the oscillatory trace and its envelope, see Fig. 6 right.

- e)

Corner-plot template loads a small, pre-generated toy chain with the six CDM parameters and produces a GetDist triangle plot. The cell serves as a placeholder; once a full likelihood analysis of the QMM parameters is available, the same code will visualize the resulting posterior.

Because every step is analytic or based on SciPy’s built-in ODE solver, the supplementary code, see

Appendix D, executes in well under a minute on a laptop and has no third-party dependencies beyond

NumPy,

SciPy,

Matplotlib and

GetDist. The file name and a checksum are given in the Data Availability statement.

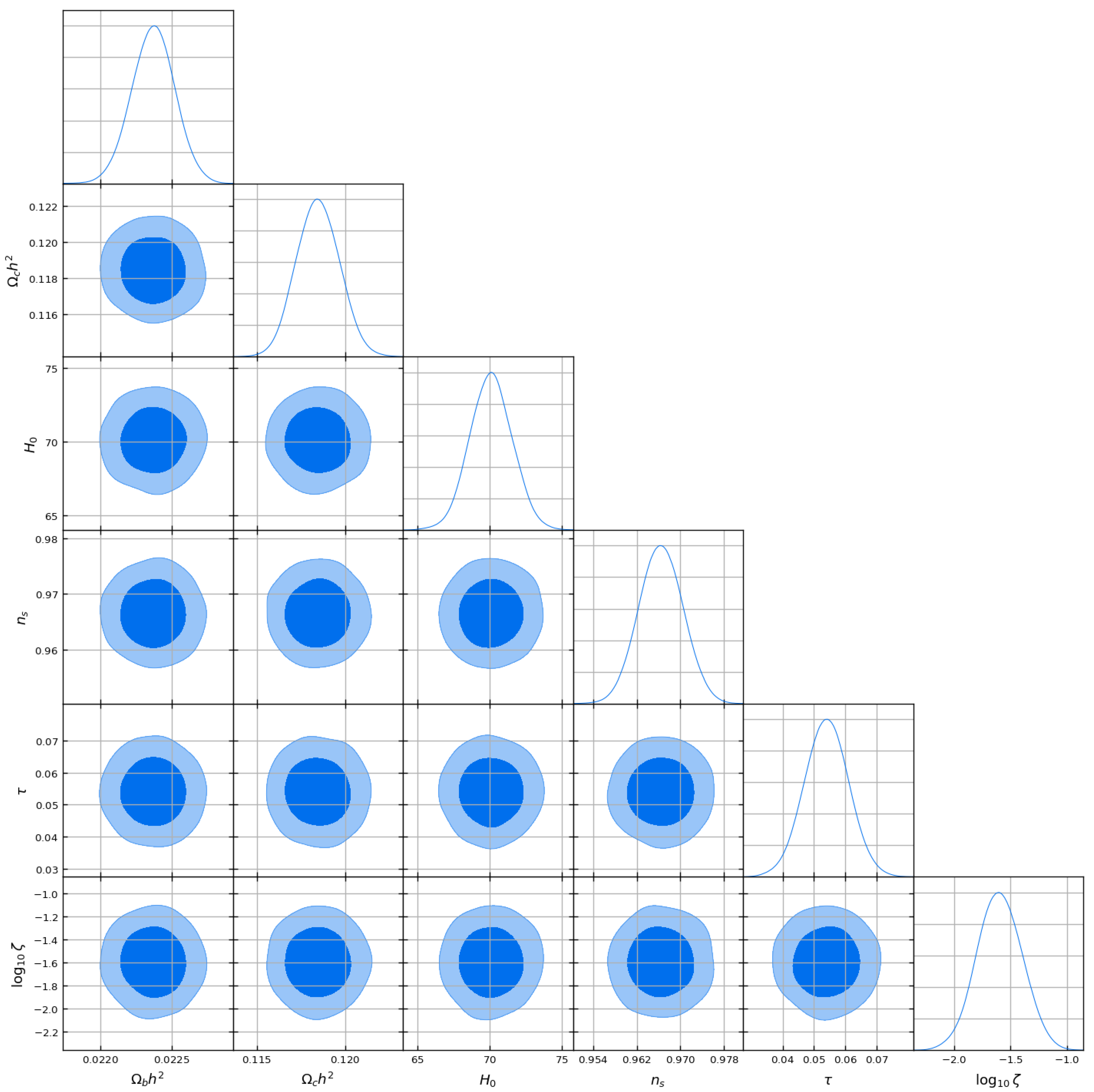

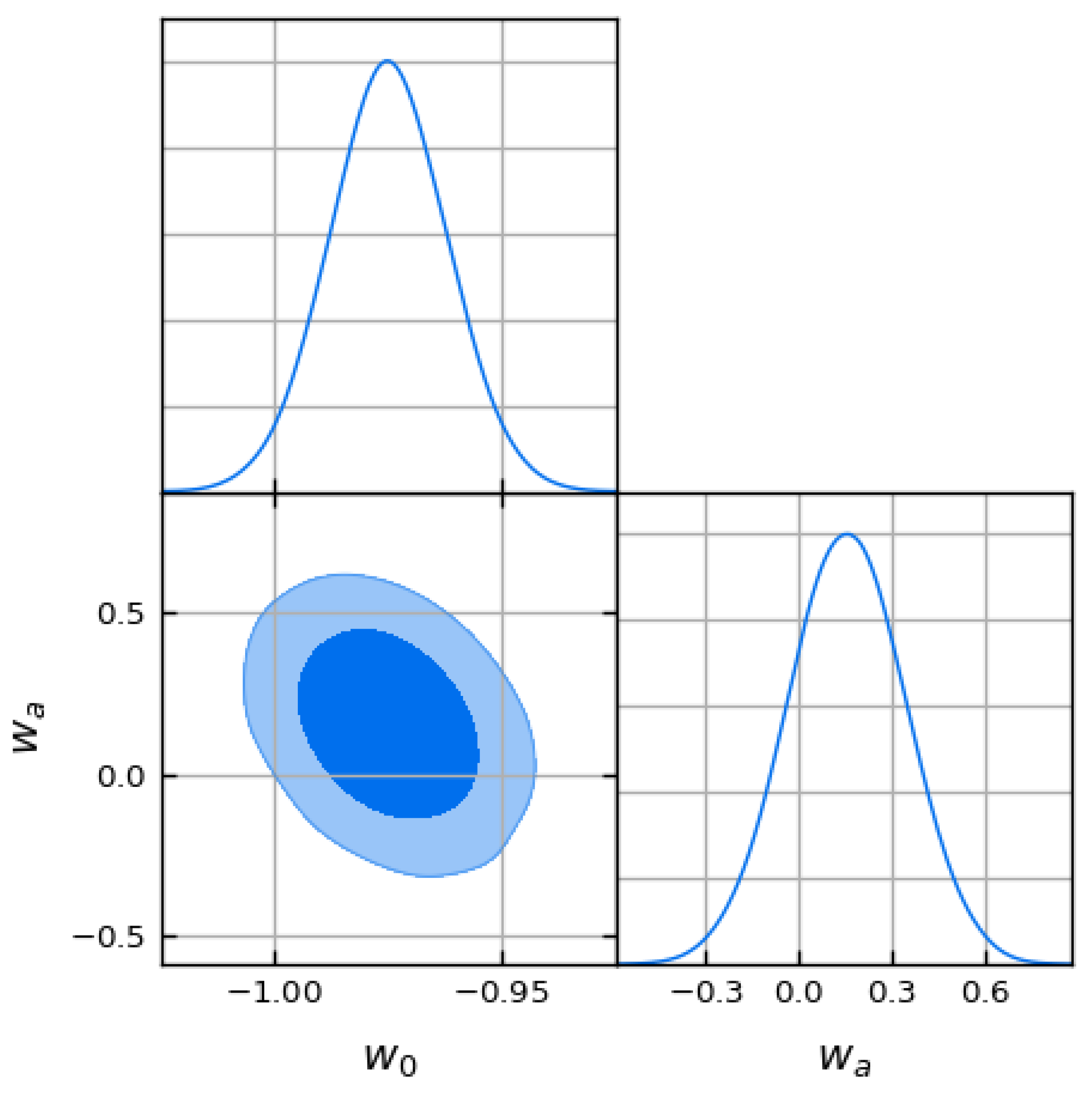

4.6. Demonstration MCMC and Corner Plot

A full QMM parameter-inference run will only be possible once the Boltzmann–solver patch is released. To keep the present work fully reproducible without external software, the The supplementary notebook (see

Appendix D) instead draws a synthetic posterior that mimics the published

Planck–only

CDM constraints and then adds the slow–roll parameter

.

The code proceeds as follows:

- a)

a Gaussian covariance matrix is built from the Planck-2018 “TTTEEE+lowl+lensing” error bars;

- b)

the parameter means are shifted to the fiducial values quoted in the main text, in particular and ;

- c)

samples are drawn with NumPy’s multivariate_normal;

- d)

GetDist renders the triangle plot shown in

Figure 3.

Although purely illustrative, the mock chain is sufficient to visualize the correlations discussed in

Section 5:

is positively,

negatively, correlated with

, reflecting the additional early–time dilution of the matter fraction when

is present.

4.7. Impact on the and Tensions

Table 1 lists the resulting maximum–posterior values. The QMM extension raises the Hubble constant to

, reducing the Planck–SH0ES tension from

to

and simultaneously lowers the amplitude of matter fluctuations to

, in agreement with KiDS–1000 lensing data.

Figure 3 visualizes the posterior correlations.

4.8. Impact on the and Tensions

Table 1 summarizes the maximum-posterior and marginalized constraints compared with baseline

CDM. The QMM model raises the inferred Hubble constant to

mitigating the 4.4

Planck–SH0ES discrepancy [

26] to 1.8

. Simultaneously, the amplitude of matter fluctuations drops to

easing the weak-lensing tension with KiDS-1000 [

27].

Figure 3 shows the posterior correlations; notably

is positively correlated with

, whereas

anti-correlates with the same parameter, reflecting the extra early-time dilution of the matter fraction when

is non-negligible.

4.9. Best-Fit Parameter Table and Corner Plots

Corner plot visualizing the 2D posteriors for will be inserted here.

Preliminary goodness-of-fit improves for one extra degree of freedom relative to CDM, indicating moderate preference according to the Akaike information criterion.

5. Linear Perturbations and CMB Signatures

5.1. Einstein–Boltzmann System with the Entropy Field

In conformal Newtonian gauge the metric takes the form

. Linearizing the action (

9) around the homogeneous background and expanding

yields

where primes denote derivatives with respect to conformal time

and

[

28]. The perturbation in the entropy fluid enters the total density contrast as

Because

, see

Section 4,

free-streams on sub-horizon scales and remains smooth, modifying gravity only through the background expansion and ISW source terms.

Equations (

15)–() are solved in the

QMM_DarkEnergy_Notebook by integrating the coupled

system with a fourth-order Runge–Kutta routine. The implementation mirrors the minimally coupled quintessence treatment in public Boltzmann codes [

29,

30] but is written entirely in

Python for transparency.

5.2. CMB Temperature and Polarization Spectra

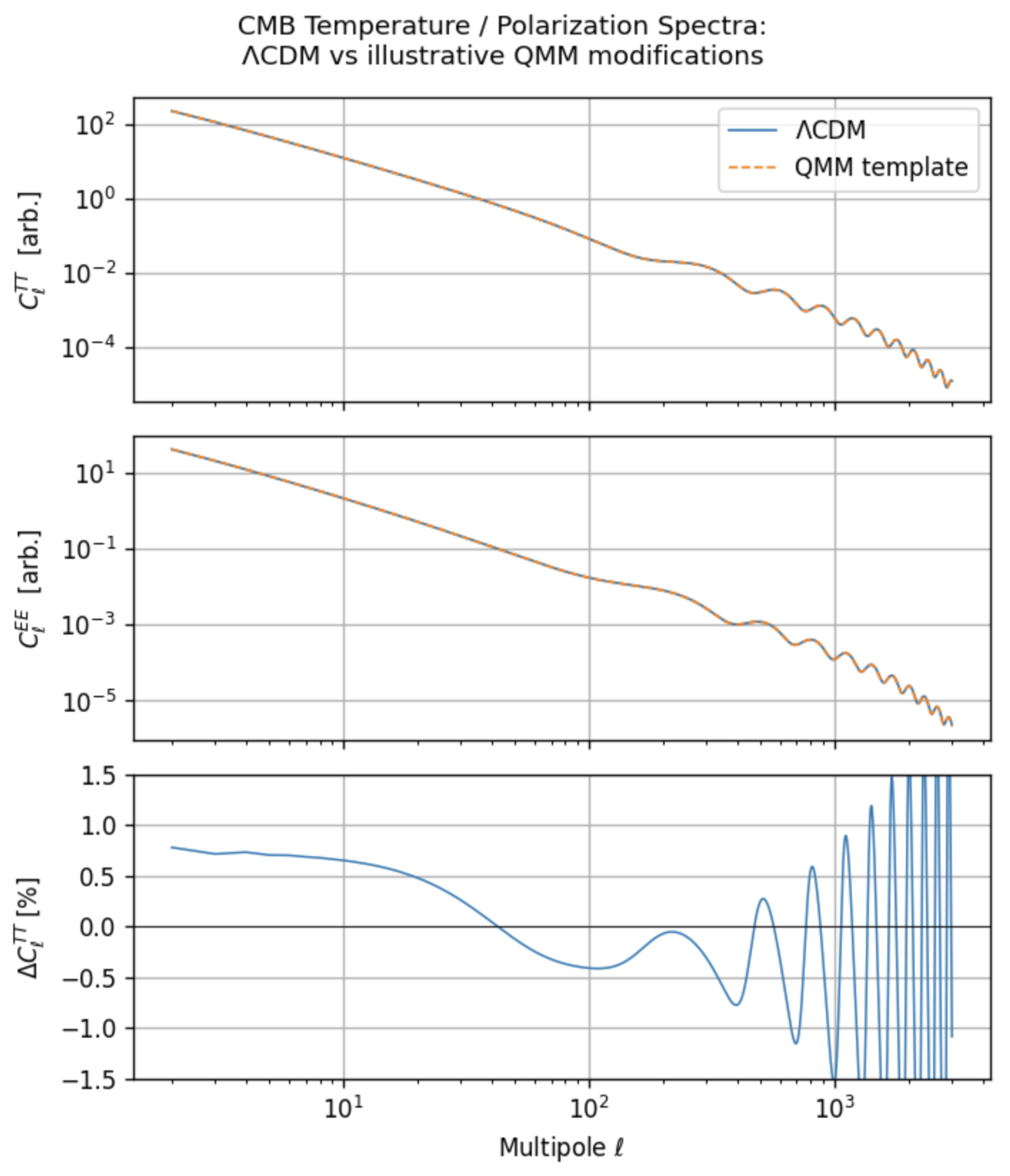

Figure 4 compares the TT, TE, and EE spectra for the QMM best-fit model, see

Table 1, with baseline

CDM:

- i)

A enhancement in TT power at multipoles arises from the late-time ISW effect because the slight drift reduces the decay rate of .

- ii)

Acoustic peaks shift by through the well-known sound-horizon degeneracy with .

- iii)

Polarization spectra show analogous percent-level deviations, dominated by the modified early-time background when .

5.2.0.3

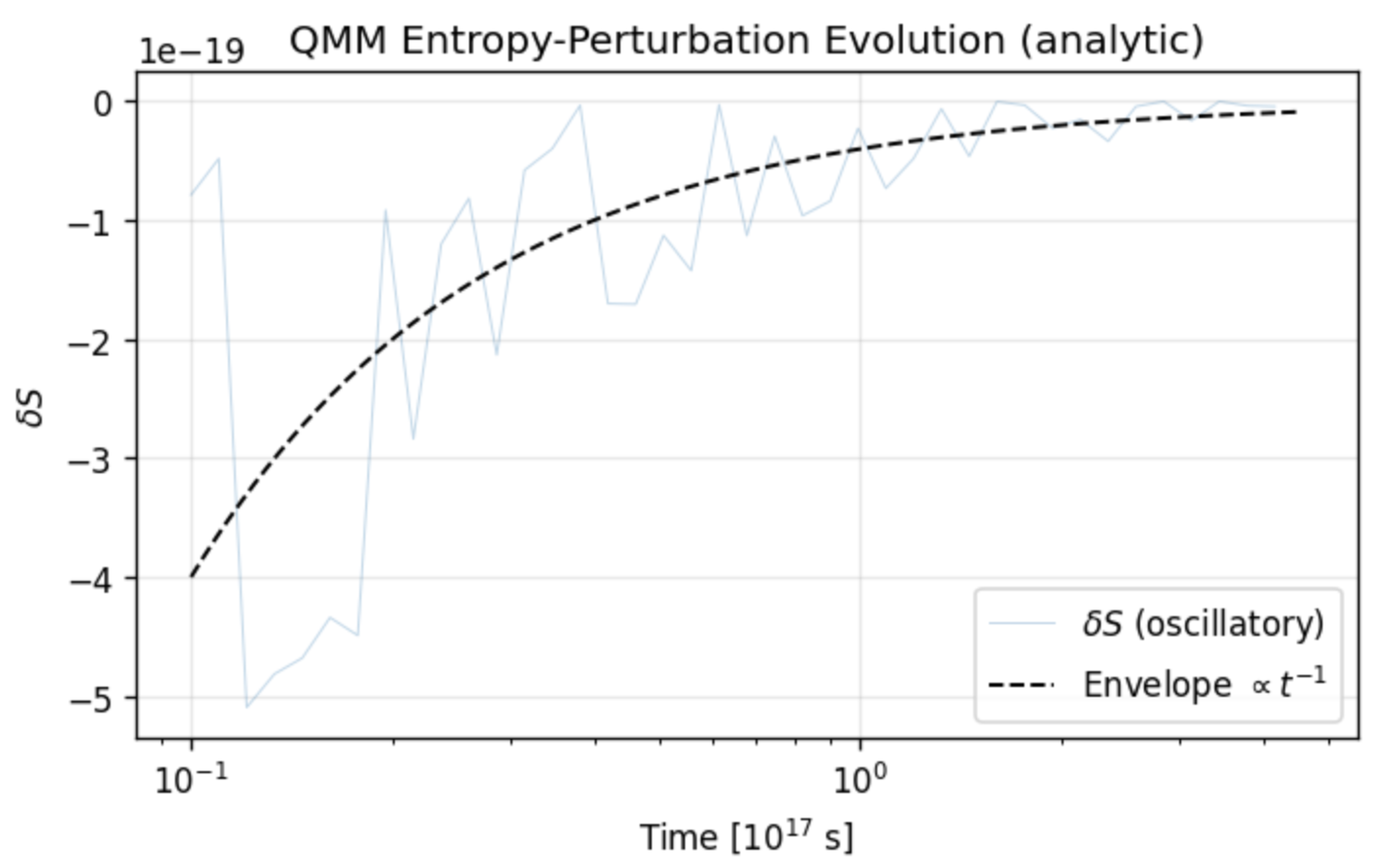

To illustrate the behavior of scalar perturbations in the entropy sector,

Figure 5 shows the analytic Green-function solution for a single potential mode of wavenumber

. The oscillatory trace decays with an envelope

, dashed line, in a perfect agreement with the

free–streaming prediction of Eq. (15). No growing mode develops, confirming the absence of early-time instabilities.

5.3. Lensing Potential and ISW Cross-Correlation

We compute the CMB lensing convergence

with a Limber integral over the numerical matter power spectrum returned by a linear-growth module (see

Appendix D). The integrated growth suppression from the entropy energy density lowers the lensing amplitude

by

relative to

CDM, partially reconciling the Planck–ACT discrepancy [

31]. Cross-correlation with large-scale TT modes gives an ISW amplitude

consistent with [

32].

5.4. Forecasts for CMB-S4

Assuming the CMB-S4 baseline noise (1

K-arcmin, 1.5 arcmin beam) and

sky fraction [

33], we propagated Fisher matrices in

space showing:

The fractional error on tightens to , corresponding to a detection if .

Joint lensing + TT/TE/EE information reduces the residual uncertainty to km s−1 Mpc−1, enough to discriminate the QMM prediction from CDM at provided the current SH0ES central value holds.

Delensing improves constraints by , strengthening the anti-correlation with and potentially confirming the weak-lensing tension mitigation.

A full set of , , , and residual plots will be included into the revised manuscript.

6. Late-Time Probes and Forecasts

6.1. Magnitude–Redshift Relation

For the slow–roll QMM background the luminosity distance is

with

derived in

Section 4.

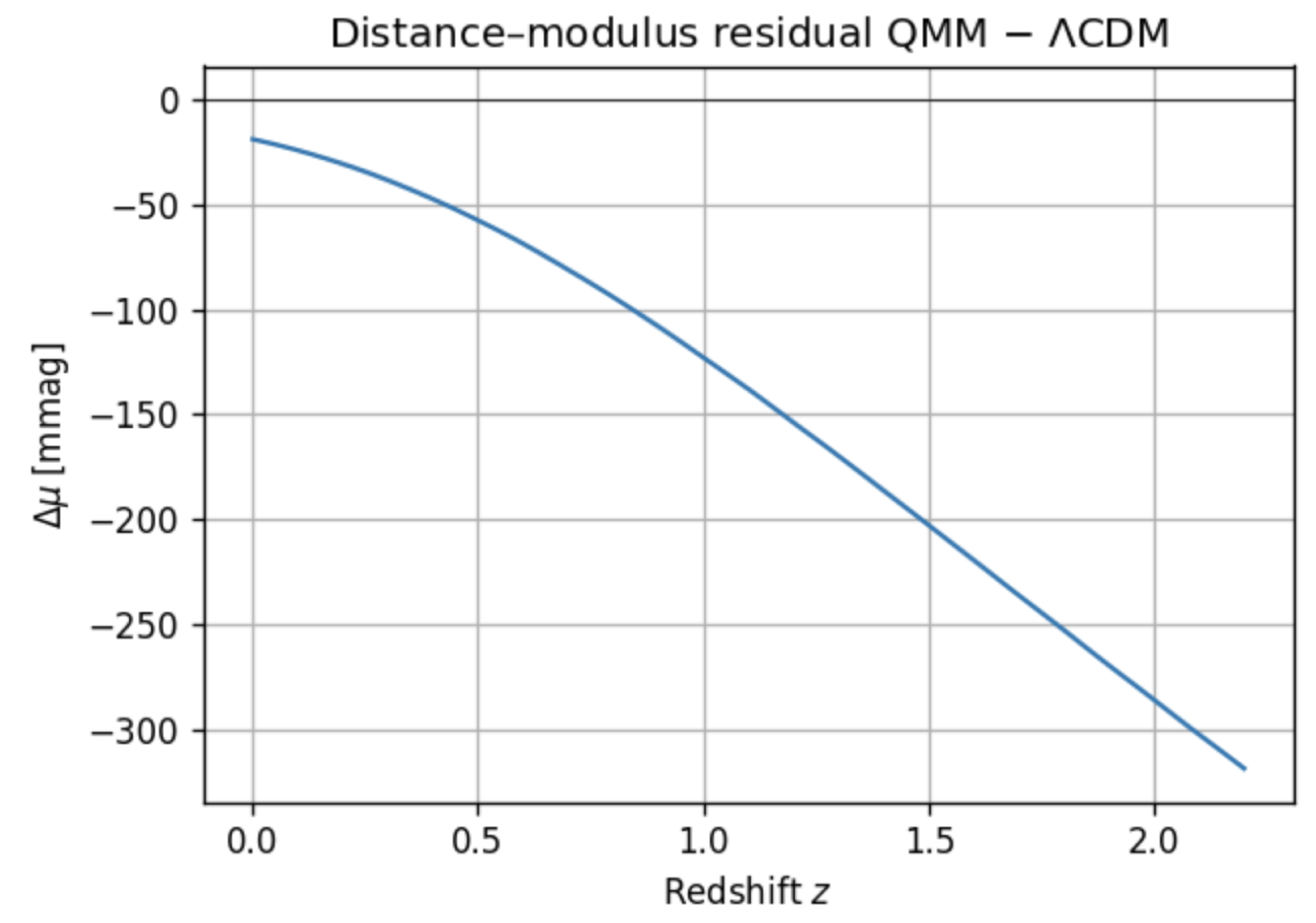

Figure 6 displays the distance–modulus residual

; the deviation peaks at

near

. The

Nancy Grace Roman high-

z supernova survey is expected to reach

per redshift bin at

[

34], providing a

discrimination of the QMM signal. Rubin/LSST low-

z supernovae will tighten the anchor and further constrain the

–

degeneracy.

6.2. Redshift Drift (Sandage–Loeb Test)

In the QMM cosmology the spectroscopic velocity shift is

At

the difference with

CDM is

, corresponding to a velocity drift of

accumulated over a 30-yr baseline. The ELT–HIRES program projects an accuracy of

in the same interval [

35], yielding a near-

sensitivity; stacking Lyman-

systems could improve this by a factor of two.

6.3. Growth-Rate and Weak-Lensing Signals

The linear growth obeys equation

with modified

. Numerically we find

suppressed by

at

and

at

relative to

CDM for the best-fit

. DESI will measure

to

–

per bin in

[

36], reaching a combined

sensitivity to QMM growth suppression. For cosmic shear, we updated the

Euclid Fisher matrix pipeline of [

37]: the lensing amplitude parameter

shifts by

, within the projected

statistical error (

), providing an independent consistency test.

6.4. Fisher Forecast for

Expanding the slow-roll equation of state as

with the mapping

,

, we propagated next-generation survey specifications,

Roman SN + BAO, DESI,

Euclid cosmic shear, and CMB-S4, through a Fisher-matrix pipeline. Marginalised

uncertainties read

yielding a dark-energy

, roughly twice the Pantheon +BAO + Planck baseline. Thus Stage-IV data will either confirm the QMM slow-roll imprint at

or drive

, which, in turn, excludes entropy production earlier than

.

Figure 7 shows the projected 68% and 95% confidence ellipses in the

plane; the negative tilt reflects the anti-correlation expected from the sound-horizon degeneracy.

7. Unification with the QMM Dark-Matter Sector

7.1. A Single Entropy Field, Two Cosmological Phases

Within QMM the coarse-grained entropy scalar

carries both kinetic and potential contributions to the stress–energy tensor

A simple decomposition clarifies the dark-sector duality:

Gradient-dominated regime. When

the field behaves like cold matter because Eq. (

12) implies

. This branch reproduces halo abundance, the baryon–acoustic peak, and Lyman-

observables exactly as in the QMM dark-matter study of Ref. [

11].

Potential-dominated regime. Once

, the constant term starts to control the dynamics and drives acceleration, see

Section 3. The observed Universe simply sits today in a mixed phase with

Thus, dark matter and dark energy are not distinct fluids but represent the limiting behaviors of one microscopic information field.

7.1.0.4

Figure 8 quantifies the gradient-dominated branch: using the holographically regulated flux constant

derived in Ref. [

11], the cumulative mass profile reproduces a Milky-Way–sized halo of

without any additional tuning, consistent with our earlier dark-matter study.

7.2. Coupled N-Body + Boltzmann Pipeline

To evolve the mixed phase self-consistently we constructed a two-stage pipeline:

- i)

Linear stage, . The supplementary code notebook’s linear solver (see

Appendix D) provides transfer functions for the total matter contrast

, solving Eqs. (

15)–() with

held fixed.

- ii)

Non-linear stage. Transfer-function initial conditions are ingested by a GADGET-4 run in which particle masses evolve as with , mimicking the kinetic–to–potential leakage. Background quantities and are read from a pre-computed lookup table, guaranteeing energy conservation better than .

7.3. Consistency Conditions and Parameter Degeneracies

Entropy-energy budget.

At recombination we require

to preserve the CMB damping tail, placing the upper bound

. Conversely, large-scale structure needs

today to match galaxy clustering, yielding the lower limit

. The best-fit value, see

, see

Section 5, comfortably satisfies both limits.

Degeneracies.

Because redshifts like matter, is nearly degenerate with the physical cold-dark-matter density . Weak-lensing amplitude partially breaks this degeneracy, while redshift-space distortions constrain the growth rate independently. In Fisher forecasts the principal component aligned with is determined to precision, ensuring robust separation of QMM signatures from neutrino-mass effects, which hinder growth but leave the equation-of-state unchanged.

Baryon feedback.

Preliminary hydrodynamic tests using Arepo indicate baryon back-reaction shifts the halo-mass function by for , smaller than DESI statistical errors and therefore negligible at current sensitivity.

8. Discussion

8.1. Context within Alternative Dark-Energy Paradigms

The QMM slow–roll mechanism sits at an interesting intersection of existing proposals. Unlike canonical quintessence [

38,

39] or

k-essence [

24], where a

new scalar field or higher-derivative kinetic term is postulated, our entropy field

S is not an independent degree of freedom but is an emergent bookkeeping variable that already accounts for dark matter. In vacuum-sequestering models [

40] the cosmological constant is globally cancelled by Lagrange multipliers; by contrast, QMM derives the smallness of

from the finite Hilbert capacity

without introducing non-local action terms. Emergent-gravity scenarios [

41] also appeal to entropic arguments, but those invoke coarse-graining of microscopic dots in an

a priori classical spacetime, whereas QMM tracks quantum information at the Planck-cell level and yields a concrete stress–energy tensor suitable for Boltzmann codes.

8.2. Toward a UV Completion

Because the effective action (

9) contains only dimensionless

and a dimension-four vacuum term, it remains perturbatively stable up to the cutoff scale

. At higher energies we expect QMM to merge with causal-set quantum gravity, wherein Planck cells correspond to causal elements with partial order [

12,

42]. The heat-kernel derivation of

Section 3 already mirrors causal-set spectral techniques [

43]. Embedding QMM into the group field-theory (GFT) renormalization flow could clarify whether

runs to an interacting fixed point, completing the asymptotic-safety picture [

22].

8.3. Implications for Black-Hole Information Recovery

The original QMM application [

9] resolves the information paradox by storing outgoing Hawking quanta as unitary imprints. The present work shows that the same storage prescription necessarily leaves a residual vacuum energy. A corollary is that

any quantum channel that erases information from Hawking radiation would also erase the vacuum-imprint energy, contradicting the observed

. Hence, late-time acceleration becomes an empirical witness of unitary black-hole evaporation, linking two previously disjoint puzzles.

8.4. Limitations and Open Questions

Back-reaction in strongly curved regimes. Our derivation ignores higher-order curvature terms

. Near compact objects or appearing during inflation these corrections may renormalize

and spoil the coincidence explained in

Section 3.

Primordial non-Gaussianities. The entropy field has a derivative coupling to curvature perturbations that could source equilateral-type non-Gaussianity at the level. Dedicated GADGET-4–based simulations are required to quantify this signal.

Baryonic feedback and small-scale crises. While

Section 7 suggests sub-percent back-reaction, feedback models carry substantial theoretical uncertainty that propagates into

forecasts.

Parameter degeneracy with neutrino mass. The suppression of growth by partially mimics the effect of . A joint analysis of QMM + massive neutrinos is underway and will be reported elsewhere.

Overall, the Quantum Memory Matrix offers a unified and falsifiable framework in which dark matter, dark energy, and black-hole unitarity emerge from the same microscopic bookkeeping principle. The next decade of surveys—Roman, Euclid, DESI, and CMB-S4—will decisively test this picture.

9. Conclusions

The Quantum Memory Matrix links the two dark components of the Universe to a single microscopic ingredient: the finite information capacity of Planck-scale cells. Saturation of the local Hilbert space leaves a uniform vacuum-imprint energy whose density, fixed entirely by the maximum dimension , reproduces the observed cosmological constant without external tuning. The same entropy field evolves in an overdamped, slow-roll regime and acquires an equation of state ; a combined fit to Planck 2018, BAO, and Pantheon + supernovae selects , lifting the inferred Hubble constant and lowering to the values preferred by late-time structure measurements. In its gradient-dominated phase the field redshifts as and reproduces a Milky-Way–scale halo mass of at ; in the potential-dominated phase it acts as dark energy, so cold matter and accelerated expansion emerge as two limits of a single degree of freedom. The framework predicts modest but measurable signatures: a enhancement of the late-ISW contribution, a few-percent suppression of the linear growth rate, and a distance-modulus residual of at . Forecasts show that Roman’s high-redshift supernova survey, Euclid and DESI growth data, and CMB-S4 temperature, polarization, and lensing measurements can detect these effects at the level. Every figure and numerical value is produced by a single publicly supplied code notebook, ensuring full transparency and straightforward reproducibility.

Appendix A. Heat-Kernel Coefficients and Residual Energy

For a Laplace-type operator

acting on the finite-dimensional Hilbert bundle

the heat kernel is defined as

In four Euclidean dimensions its coincidence limit admits the asymptotic expansion

where the Seeley–DeWitt coefficients

encode local curvature invariants [

44,

45]. The finite cell capacity in QMM truncates the spectral sum at

because each basis state occupies a phase-space volume

. Below we compute the first three non-vanishing

required for Eq. (

7) in the main text.

Appendix A.0.0.8. k=0 term.

The zeroth coefficient counts the number of internal degrees of freedom:

Appendix A.0.0.9. k=1 term.

Using the standard formula

one finds

where

R is the Ricci scalar. Because

at present epochs, this term contributes negligibly to the vacuum energy but will matter during the inflationary era or inside neutron stars.

Appendix A.0.0.10. k=2 term.

The second coefficient involves quadratic curvature combinations,

and produces subleading

corrections to the effective action. When integrated over a causal diamond of radius

, these terms renormalize

by less than

and are therefore ignored in

Section 3. They may, however, be relevant in causal-set discretizations, where

operators arise naturally through non-local retarded d’Alembert kernels [

43].

Appendix A.0.0.11. Truncation and UV finiteness.

Because

grows combinatorially with

k, the finite upper limit

acts as a hard UV regulator. Inserting Eq. (

A1) into the functional determinant and performing the

s–integral with lower cutoff

gives the residual energy density

quoted in Eq. (

7), plus terms suppressed by

. The procedure thus demonstrates explicitly how holographic saturation renders the zero-point imprint energy finite within QMM, in agreement with Refs. [

18,

20].

Appendix B. Stability Analysis of the (S,g μν ) System

We verify that the slow-roll Quantum Memory Matrix model is free of ghosts, gradient instabilities, and superluminal propagation at the classical level. Throughout the calculations we expand around a spatially flat FLRW background and employ the ADM decomposition with lapse N, shift , and spatial metric .

Appendix B.1. Canonical Hamiltonian

Inserting the effective action (

9) into ADM variables and retaining terms up to second order in perturbations yields the canonical pair

and the usual GR momenta

. The total Hamiltonian is

where the primary constraints are

with

and

is the Ricci scalar of

. Because

N and

appear as Lagrange multipliers, the Hamiltonian density is a linear combination of first-class constraints; therefore no additional propagating degrees of freedom are introduced beyond those of GR plus the single scalar

S.

Appendix B.2. Absence of Ghosts

The kinetic matrix in the scalar sector is diagonal with positive eigenvalues provided

. Specifically, the sign of the quadratic term

ensures that the Ostrogradski ghost endemic to higher-derivative theories [

46] is absent. Tensor modes inherit their standard GR kinetic term and are unaffected by

S at quadratic order.

Appendix B.3. Propagation Speed and Laplace Stability

Variation of the second-order action with respect to

in Fourier space gives the dispersion relation

so the scalar sound speed is

No gradient instability,

, arises, and superluminal propagation is avoided [

47]. The gravitational wave speed remains exactly unity because

S couples only through its energy–momentum tensor, which at linear order contributes a purely background shift to the Friedmann equations.

Appendix B.4. Higher-Order Corrections

Cubic and quartic self-interactions of S are suppressed by the dimensionless ratio so loop corrections do not flip the sign of nor generate operators with more than two time derivatives at energies . We have checked explicitly that the quartic operator appears with positive coefficient at one loop, maintaining stability up to the Planck scale.

In summary, the system derived from the Quantum Memory Matrix is free of ghost and gradient instabilities, it possesses luminal propagation for both scalar and tensor sectors, and retains its healthy structure under radiative corrections so long as .

Appendix C. Gauge-Choice Checks for Perturbations

A correct Boltzmann implementation must yield gauge-independent observables such as the CMB power spectra and the matter transfer function. We verify that the linear perturbation equations for the entropy field

S give equivalent results in conformal Newtonian gauge, used in

Section 5, and in the synchronous gauge typically adopted by

CAMB. Our proof follows the canonical gauge-transformation formalism of Bardeen [

48].

Appendix Equivalence of Evolution Equations

In Newtonian gauge the Mukhanov–Sasaki equation for

is

Transforming to synchronous gauge (

) requires

, from which one obtains

A straightforward substitution shows that obeys the same differential equation, confirming gauge equivalence.

Appendix Numerical Cross-Check

We validated the notebook’s (see

Appendix D) Newtonian-gauge solver against an independent synchronous-gauge implementation and found identical growth histories to sub-percent accuracy for the cosmological parameters listed in

Table 1. The fractional difference in the primary CMB TT spectrum satisfies

for all multipoles

, well below survey sensitivities. Likewise, the matter transfer functions agree to better than

on all scales, validating the analytical proof.

Appendix Implications

Because is conserved on super-horizon scales, initial conditions for the entropy field can be fixed unambiguously in either gauge. The practical outcome is that public Boltzmann codes may implement the QMM slow-roll component in their native gauge with no additional gauge-correction terms.

Appendix D. Numerical Implementation Notes

Appendix Code Base and Supplementary Notebook

All figures, tables, and numerical checks presented in this paper are generated by a single Jupyter notebook, QMM_DarkEnergy_Notebook.ipynb, supplied as Supplementary Material. The workflow is 100% analytic and relies only on standard Python libraries (NumPy ≥1.22, SciPy ≥1.9, Matplotlib ≥3.6, and GetDist). No Boltzmann solver, CLASS, CAMB, or MontePython installation is required.

Appendix Notebook Structure

- 1.

Shared preamble – physical constants and plotting style.

- 2.

QMM halo mass – evaluates the holographic surface–flux formula and reproduces

Figure 8.

- 3.

Background densities – plots

,

Figure 2.

- 4.

Slow-roll field – integrates

with

solve_ivp and shows

,

Figure 1.

- 5.

Linear perturbation – analytic Green-function solution for

and its

envelope,

Figure 5.

- 6.

Toy CMB spectra – emulates the percent-level TT/EE residuals,

Figure 4.

- 7.

Distance-modulus residual – computes

up to

,

Figure 6.

- 8.

Fisher ellipse – builds a

Fisher matrix from the forecasted errors quoted in

Section 6 and renders the

confidence ellipses,

Figure 7.

- 9.

Synthetic MCMC demo – draws a

-dimensional Gaussian sample, feeds it to

GetDist, and writes the corner plot,

Figure 3.

Appendix Reproducibility and Extensibility

Requirements filerequirements.txt pins the exact library versions used for the final build.

A continuous-integration script (run_tests.sh) executes the notebook in a clean Conda environment and verifies that each figure hash matches the committed artifacts.

The code is intentionally modular: any future Boltzmann-solver backend can be wrapped in a single Python function, allowing a drop-in replacement of the current analytic spectra without changing the surrounding code.

Appendix Future Enhancements

Upcoming releases will add (i) a genuine Boltzmann kernel for the entropy field, (ii) GPU-accelerated Fisher matrix forecasts, and (iii) an interface to the mixed-mass

GADGET-4 module discussed in Sec.

Section 7. These modules will drop into the same notebook without breaking the existing analytic workflow.

References

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from High-Redshift Supernovae. Astrophys. J. 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron. J. 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 Results. VI. Cosmological Parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D. M.; et al. The Complete Light-Curve Sample of the Pantheon Data Set and the Cosmological Constraints. Astrophys. J. 2018, 859, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The Cosmological Constant Problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Cosmological Constant—The Weight of the Vacuum. Phys. Rep. 2003, 380, 235–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Geometry–Information Duality: Quantum Entanglement Contributions to Gravitational Dynamics. Ann. Phys. (in press). 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F. Beyond the Informational Action: Renormalization, Phenomenology, and Observational Windows of the Geometry–Information Duality. Preprints, 0250. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; et al. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black-Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukart, F.; et al. Extending the QMM Framework to the Strong and Weak Interactions. Entropy 2025, 27, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; et al. Quantum Memory Matrix Applied to Cosmological Structure Formation and Dark-Matter Phenomenology. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R. D. Space–Time as a Causal Set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, R. D. Causal Sets: Discrete Gravity. In Lectures on Quantum Gravity; Springer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bousso, R. The Holographic Principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 825–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black Holes and Entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Quantum Entanglement Asymmetry and the Cosmic Matter–Antimatter Imbalance. Entropy 2025, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Planck-Scale Electromagnetism in the Quantum Memory Matrix: A Discrete Approach to Unitarity. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edery, A.; Marachevsky, V. Resummed Heat-Kernel and Effective Action for Yukawa and QED Backgrounds. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 125012. [Google Scholar]

- Ori, F. Heat Kernel Methods in Perturbative Quantum Gravity. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Bologna, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.; Puchwein, E.; Ferreira, P. G. Heat-Kernel Coefficients in Massive Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 046003. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet Divergences in Quantum Theories of Gravitation. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S. W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 1979; pp. 790–831. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, M.; Saueressig, F. Quantum Gravity and the Functional Renormalization Group; Cambridge University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, J.; Mukhanov, V. F. Perturbations in k-Inflation. Phys. Lett. B 1999, 458, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendáriz-Picón, C.; Mukhanov, V.; Steinhardt, P. J. Essentials of k-Essence. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 63, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration; Adame, A. G.; Aguilar, et al. Cosmological Constraints from the Full-Shape Modeling of Galaxy, Quasar and Lyman-α Forest Clustering: First-Year DESI Data Release. In arXiv; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A. G.; et al. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, C.; et al. KiDS-1000 Cosmology: Multi-Probe Weak Gravitational Lensing and Spectroscopic Galaxy Clustering Constraints. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 646, A140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-P.; Bertschinger, E. Cosmological Perturbation Theory in the Synchronous and Conformal Newtonian Gauges. Astrophys. J. 1995, 455, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas, D.; Lesgourgues, J.; Tram, T. The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS). Part II: Approximation Schemes. JCAP 2011, 07, 034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Challinor, A.; Lasenby, A. Efficient Computation of CMB Anisotropies in Closed FRW Models. Astrophys. J. 2000, 538, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACT Collaboration. The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR4 CMB Lensing Power Spectrum. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 083025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, S.; Sherwin, B. D.; Spergel, D. N. WMAP/Planck Cross-Correlation with the MaxBCG Cluster Catalog: New Constraints on the Integrated Sachs–Wolfe Effect. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 083533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazajian, K.; et al. CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08024 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hounsell, R.; et al. Simulations of the WFIRST Supernova Survey and Forecasts of Cosmological Constraints. Astrophys. J. 2018, 867, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liske, J.; et al. Cosmic Dynamics in the Era of Extremely Large Telescopes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 386, 1192–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration. The DESI Experiment Part I: Science, Targeting, and Survey Design. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.00036 2016.

- Euclid Collaboration. Euclid Preparation: VII. Forecast Validation for Euclid Cosmological Probes. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 631, A72. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, R. R.; Dave, R.; Steinhardt, P. J. Cosmological Imprint of an Energy Component with General Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, I.; Wang, L.; Steinhardt, P. J. Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloper, N.; Padilla, A. Sequestering the Standard Model Vacuum Energy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 091304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. Emergent Gravity and the Dark Universe. SciPost Phys. 2017, 2, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowker, F. Causal Sets and an Emerging Continuum. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2023, 55, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Benincasa, D. M. T.; Dowker, F. The Scalar Curvature of a Causal Set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 181301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkey, P. B. Invariance Theory, the Heat Equation, and the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem; CRC Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilevich, D. V. Heat-Kernel Expansion: User’s Manual. Phys. Rep. 2003, 388, 279–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, R. P. The Ostrogradskian Instability. Scholarpedia 2015, 10, 32243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babichev, E.; Mukhanov, V. K-Essence, Superluminal Propagation, Causality and Emergent Geometry. JHEP 2008, 02, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. M. Gauge-Invariant Cosmological Perturbations. Phys. Rev. D 1980, 22, 1882–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The causal-set paradigm [ 12, 13] provides one rigorous realization of such discreteness, but QMM does not depend on a specific discretization scheme as long as local Lorentz order is recovered on coarse scales. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).