1. Introduction

The quest to reconcile quantum mechanics (QM) with general relativity (GR) remains one of the most profound challenges in theoretical physics. While quantum field theory (QFT) and the Standard Model have successfully described three of the four fundamental forces—electromagnetism, the weak interaction, and the strong interaction—gravity still defies a complete quantum treatment. Approaches such as loop quantum gravity [

1,

2,

3,

4], string theory [

5,

6,

7], and asymptotic safety scenarios [

8,

9] have provided valuable insights, yet a fully consistent and experimentally testable quantum theory of gravity remains elusive. A central difficulty is encapsulated by the black hole information paradox [

10,

11,

12,

13]: while Hawking radiation—predicted by QFT in curved space–time—appears nearly thermal, its implications for the unitarity of quantum evolution pose a serious conceptual challenge.

In this context, the

Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM ) hypothesis [

19] offers a distinct perspective by treating space–time itself as a dynamic quantum information repository. In the QMM framework, the classical continuum is replaced at the Planck scale by a discretized structure of quantum cells, each endowed with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space. Interactions of quantum fields with these cells produce

quantum imprints—local records encoding the state of the fields and events—thereby providing a mechanism to preserve unitarity even in extreme gravitational scenarios such as black hole evaporation.

This paper extends the QMM approach to include electromagnetic interactions—a task that, despite the familiarity of U(1) gauge theory in the continuum, poses significant challenges in a discretized, memory-based setting. In conventional quantum electrodynamics (QED), the U(1) gauge field and its gauge symmetry are well understood. However, embedding these concepts into the QMM framework requires a nontrivial reformulation. In our approach, the electromagnetic field is represented using link variables defined on the edges connecting Planck-scale cells, which naturally implement the covariant derivative while preserving locality. This demands the construction of novel gauge-invariant imprint operators—operators defined on the combined space of field degrees of freedom and the QMM cells—that encode electromagnetic field strengths and matter currents in a manner consistent with the discrete geometry. Thus, our formulation goes beyond a straightforward application of standard gauge theory by providing a structured, operator-level treatment that maintains gauge invariance, locality, and unitarity at the Planck scale.

Our approach differs from methods that invoke extra spatial dimensions or rely on asymptotic boundary conditions. Instead, it embraces a fundamentally discrete and background-independent picture, akin to causal sets and loop quantum gravity, but with a crucial emphasis on the quantum informational role of space–time quanta. By integrating electromagnetism into the QMM, we propose a finite, gauge-invariant discretization scheme that has the potential to tame ultraviolet divergences and shed new light on the high-energy behavior of QED within a quantum gravitational regime.

The manuscript is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we briefly recapitulate the foundational principles of the QMM hypothesis, summarizing the discretization scheme and the concept of quantum imprints. In

Section 3 we extend the QMM framework to electromagnetism by constructing gauge-invariant imprint operators and formulating the corresponding interaction Hamiltonian on a discrete lattice.

Section 4 applies this extended framework to analyze charged black hole evaporation and possible modifications to vacuum polarization and cosmological phenomena. In

Section 5 we critically compare our approach with other unification attempts, highlighting its unique local and quantum informational features. Finally,

Section 6 discusses potential experimental and observational strategies to test the predictions of the QMM framework. Throughout, we work with the metric signature

, set

, and denote space–time coordinates by Greek indices

. Standard references in QFT, GR, and gauge theories (e.g., [

20,

21]) are employed where appropriate.

2. Foundations of the Quantum Memory Matrix

In this section we briefly recapitulate the key elements of the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) hypothesis that underpin our later extension to electromagnetism. The QMM framework posits that, at the Planck scale, the smooth continuum of classical space–time is replaced by a discrete assembly of finite-sized cells—each acting as an active repository of quantum information. Although many details of the construction have been elaborated in our previous work [

19], here we review the essential principles: the discretization of space–time into finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, the mechanism by which local interactions leave

quantum imprints, and the way in which unitarity, locality, and covariance are preserved. These features provide the foundation for later incorporating gauge fields such as electromagnetism.

2.1. Discretization of Space–Time and Finite-Dimensional Hilbert Spaces

A central assumption of QMM is that the classical continuum is not valid at the Planck scale (); instead, space–time is composed of discrete, finite-sized cells (or space–time quanta). These cells serve both as the fundamental geometric building blocks and as the sites at which quantum information is actively stored.

Let each cell be labelled by an index

, where

denotes the complete set of cells. Each cell

x is associated with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

. The total Hilbert space of the QMM is then given by

Within each a finite basis of states encodes both geometric properties (such as discrete spectra of length, area, and volume, analogous to those found in loop quantum gravity or spin foam models) and quantum information relevant to local field interactions.

By conferring a finite dimension on each , the QMM naturally imposes an ultraviolet (UV) cutoff at the Planck scale. While conventional continuum theories suffer from high-momentum divergences, the discretization guarantees that operators such as those measuring area and volume have discrete spectra, thereby providing an inherent regularization similar in spirit to lattice gauge theory—but with the additional feature that each cell actively stores quantum information.

Even though the fundamental description is discrete, the familiar continuum physics emerges at scales much larger than . In this regime, the collective behavior of many space–time quanta approximates smooth geometry, and Lorentz invariance, as well as the predictions of general relativity and quantum field theory, are recovered. This continuum limit is achieved by constructing imprint operators and interactions that respect the local symmetries of the low-energy effective theory.

2.2. Quantum Imprints and Local Encoding of Information

A cornerstone of the QMM hypothesis is the concept of quantum imprints—local records left in the QMM cells when quantum fields interact with them. When a field interacts at a cell x, an imprint is recorded in the local Hilbert space . Crucially, the imprint operators are defined on the combined tensor product space of the field degrees of freedom and the QMM cell. This joint action guarantees that the imprint operators, denoted , capture the full local configuration (e.g., amplitude, phase, and internal quantum numbers) while preserving the unitarity of the global evolution.

For a generic matter field

, the minimal coupling to the QMM can be expressed via an interaction Hamiltonian of the form

Here, the imprint operator encodes how the local state of the field modifies the state of the QMM cell, and vice versa, ensuring a bidirectional flow of quantum information.

Since these imprint operators are incorporated into an overall unitary evolution, the quantum coherence of the full system is preserved. Apparent information loss in semiclassical analyses (e.g., in black hole evaporation) is reinterpreted within QMM as a temporary inaccessibility: the information remains encoded in the QMM degrees of freedom and may later be retrieved through appropriate interactions.

2.3. Physical Requirements: Unitarity, Locality, and Covariance

For the QMM framework to serve as a consistent bridge between quantum field theory and gravity, it must adhere to three fundamental principles:

Unitarity: The global evolution operator is unitary. When the Hamiltonian includes contributions from both the QMM and the fields (along with their interaction terms), the evolution of the combined system conserves probability and preserves quantum coherence.

Locality: Interactions occur solely within individual cells; the imprinting mechanism operates only at the cell x where the interaction takes place. This ensures that causality is respected and no acausal influences propagate between distant cells.

Covariance: Although space–time is discretized, the formulation must remain independent of any particular coordinate system at scales much larger than the cell size. By constructing imprint operators and Hamiltonians from appropriate tensorial or scalar combinations of the field and geometric operators, the QMM framework preserves the coordinate invariance inherent to general relativity.

In our construction, the imprint operators are defined on the full tensor product space , ensuring that all field degrees of freedom are incorporated and that the global evolution remains unitary.

2.4. Retrieval Mechanisms and Information Restoration

The QMM hypothesis posits that any information embedded in the discrete cells remains preserved in the global Hilbert space, even if semiclassical reasoning suggests that it might be lost. For example, consider a black hole formed from collapsing matter described by . As the matter crosses the event horizon, the corresponding imprint operators record the infalling state in the QMM cells near the horizon. During Hawking radiation, the outgoing modes interact with these imprinted degrees of freedom, gradually revealing correlations that restore the information. In this way, what appears as information loss in a semiclassical analysis is reinterpreted within QMM as a delayed but complete retrieval of quantum information.

2.5. Comparison with Other Discrete Quantum Gravity Approaches

The QMM framework shares with loop quantum gravity and spin foam models the notion of discretized geometry; however, it extends beyond mere geometric quantization by explicitly incorporating quantum information storage into each cell. Unlike causal set theory—which focuses on the causal ordering of events—QMM assigns a finite Hilbert space to every cell and introduces imprint operators that mediate local, unitary interactions with matter and gauge fields. This explicit emphasis on quantum information processing provides a direct route for coupling to quantum fields while maintaining gauge invariance.

2.6. Implications and Transition to Electromagnetism

By embedding quantum information directly into a discretized space–time, the QMM framework offers a novel resolution to problems at the intersection of quantum mechanics and gravity. Until now, the focus has been on scalar and gravitational fields. However, incorporating electromagnetism—governed by local U(1) gauge symmetry—poses new challenges. In particular, one must construct imprint operators that remain invariant under local gauge transformations, and design a formulation in which photon states and electromagnetic field strengths are faithfully encoded within each cell. In the next section, we extend the QMM framework to include electromagnetism by explicitly constructing gauge-invariant imprint operators and formulating an interaction Hamiltonian that respects unitarity, locality, and covariance. This extension provides the basis for a more comprehensive unified approach that may ultimately be generalized to non-Abelian gauge fields and the full Standard Model.

3. Incorporation of Electromagnetism into QMM

In this section we extend the QMM framework to incorporate the electromagnetic field in a manner that rigorously preserves local U(1) gauge invariance, unitarity, and locality on a discretized space–time. This extension is far from trivial: while continuum QED is well understood, embedding its gauge structure into a Planck-scale discretized, quantum-information–oriented framework requires rethinking both the representation of the gauge field and the construction of imprint operators. In what follows, we detail our choice of representation, develop gauge-invariant imprint operators tailored for electromagnetic interactions, and derive the corresponding interaction Hamiltonian. Key illustrative figures are included to clarify the structure of the theory.

3.1. Gauge Symmetry and the Discretized Electromagnetic Field

In continuum QED the electromagnetic field is described by the gauge potential

with the standard local U(1) transformation

where

is an arbitrary real function. The corresponding field strength,

is manifestly gauge invariant.

In the QMM framework, space–time is discretized into Planck-scale cells labeled by

. To implement U(1) gauge symmetry in this discrete setting, we adopt the lattice gauge theory paradigm by representing the electromagnetic field via link variables. Concretely, we define

where

a is the lattice spacing (of order the Planck length) and

q is the charge coupling. This formulation offers several advantages:

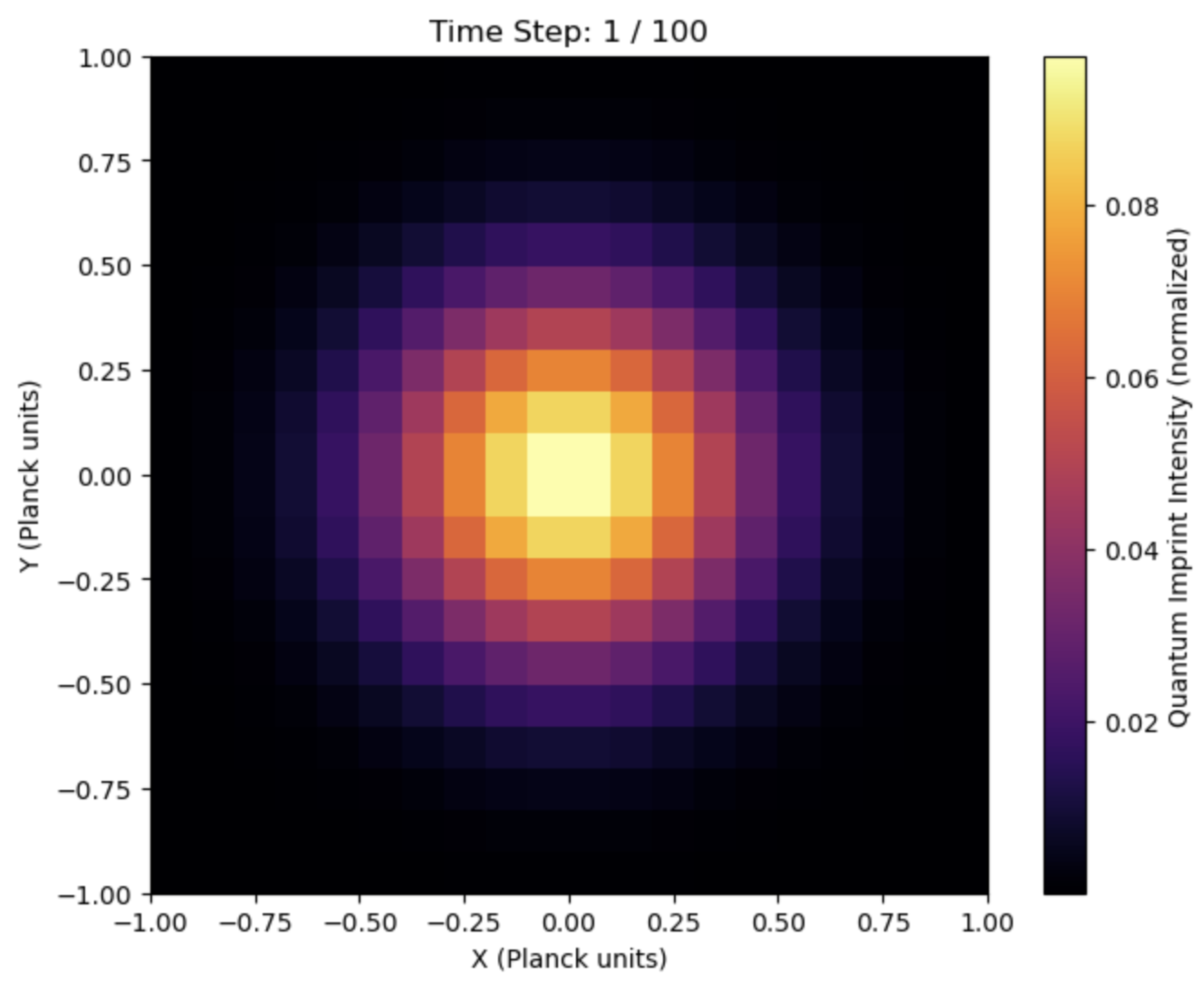

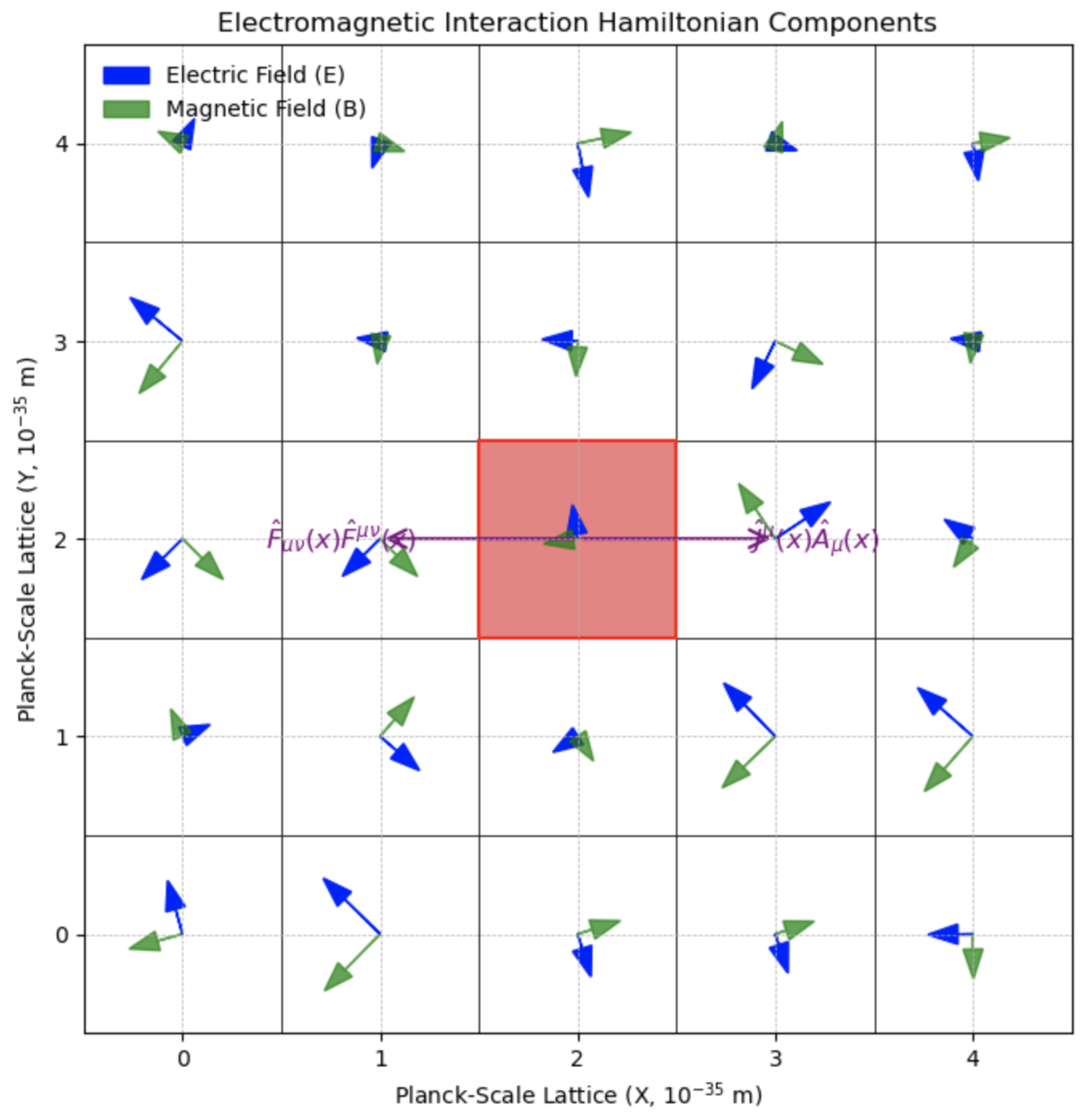

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the encoding of gauge-invariant electromagnetic information into QMM cells via link variables.

3.2. Constructing Gauge-Invariant Electromagnetic Imprint Operators

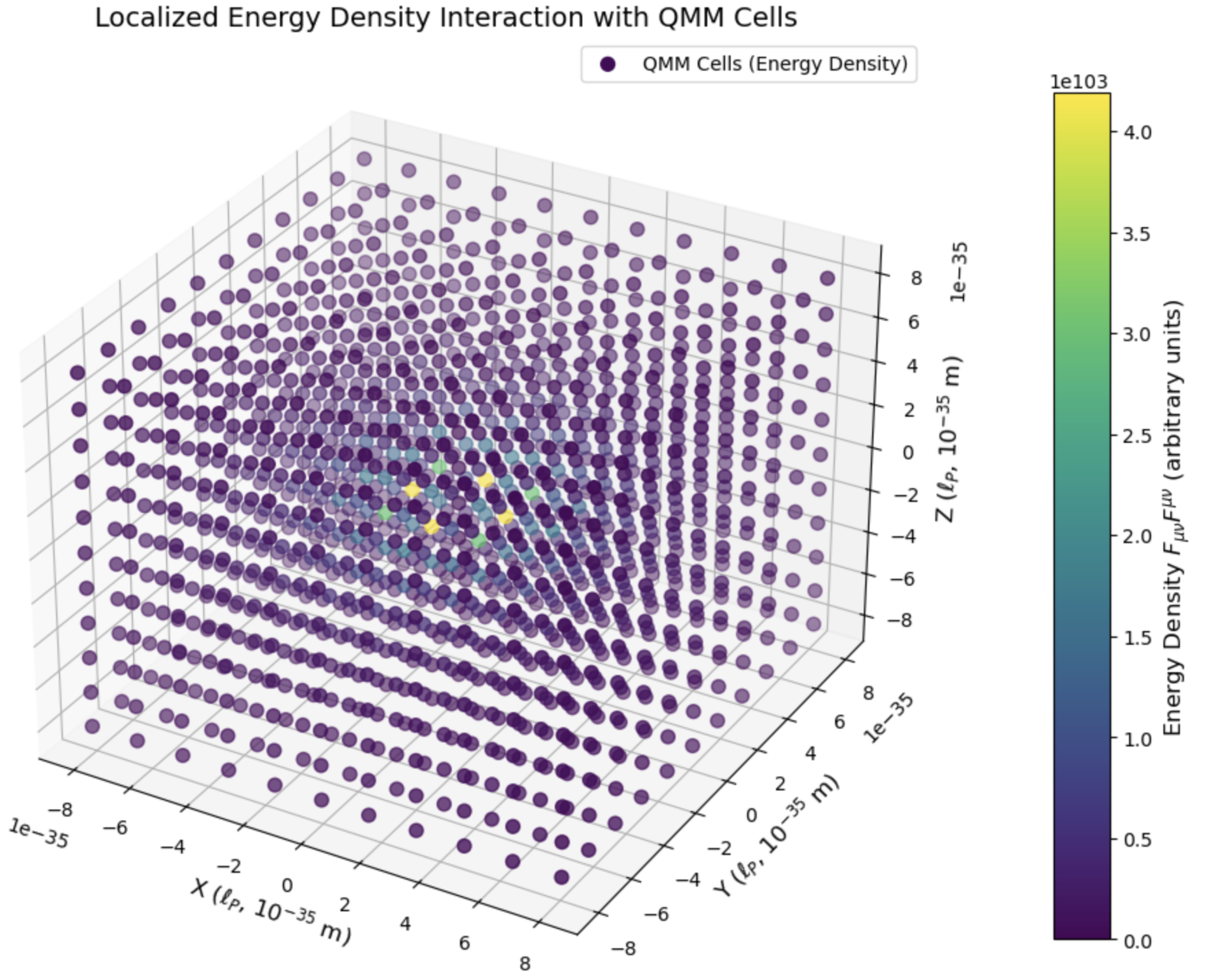

A central challenge in extending QMM to electromagnetism is constructing imprint operators that record electromagnetic data in a gauge-invariant manner. In our approach, these imprint operators are built from combinations of gauge-invariant quantities (e.g., the field strength tensor) and, when necessary, matter currents. They act on the full tensor product Hilbert space .

A natural candidate for encoding the free electromagnetic field is

where

is a coupling constant with appropriate dimensions. Here,

is defined through the discretized analog of Eq. (

4) (or equivalently via plaquette constructions using the link variables). Since

is gauge invariant for an Abelian field, this operator reliably captures the local electromagnetic energy density.

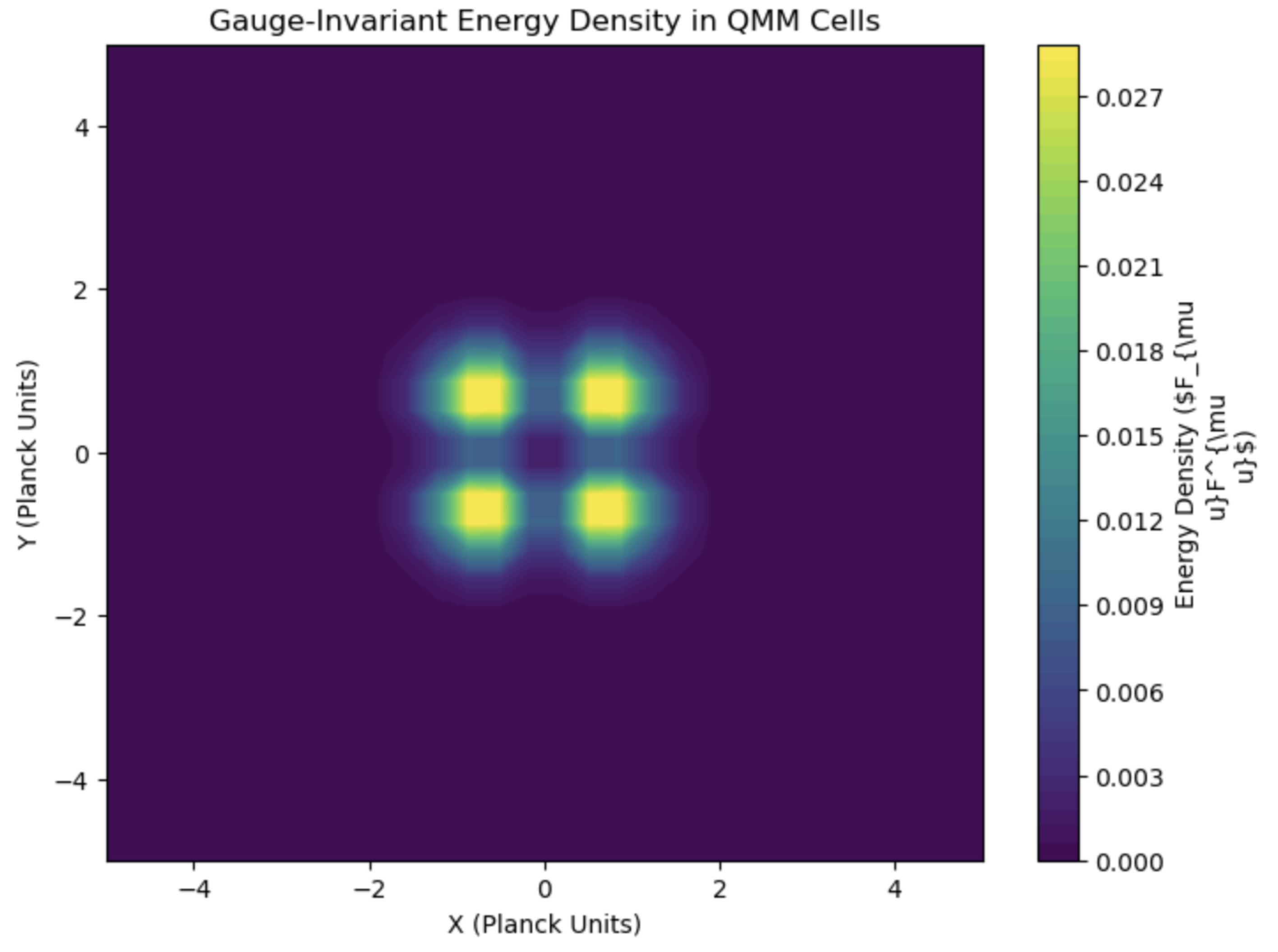

Figure 2 illustrates how electromagnetic field lines are imprinted on the QMM cells via

.

For charged matter fields, such as a Dirac field

, additional imprint operators must capture local charge-current interactions. The minimal coupling is implemented via the discretized covariant derivative,

where

corresponds to the link variable. A gauge-invariant imprint operator that incorporates the interaction between the electromagnetic field and matter is then given by

with

and

as coupling constants and

constructed in the standard manner from the matter fields. Although

is gauge dependent in isolation, by expressing it in terms of link variables or by constructing the combination appropriately, the full operator remains gauge covariant. The expansion or truncation of this operator depends on the finite-dimensional structure of

; for instance, in a qudit model of dimension

d, only a finite basis is necessary.

3.3. Interaction Hamiltonian for QMM–Electromagnetism Coupling

The complete Hamiltonian is composed of three contributions:

: The discretized version of the standard QED Hamiltonian, including the kinetic term for the electromagnetic field and the matter Hamiltonian.

: The Hamiltonian governing the intrinsic dynamics of the QMM cells.

: The interaction Hamiltonian that couples the electromagnetic (and matter) fields to the QMM via the imprint operators.

In the discretized setting,

includes, for example, the photon kinetic term

(with the corresponding matter Hamiltonian terms).

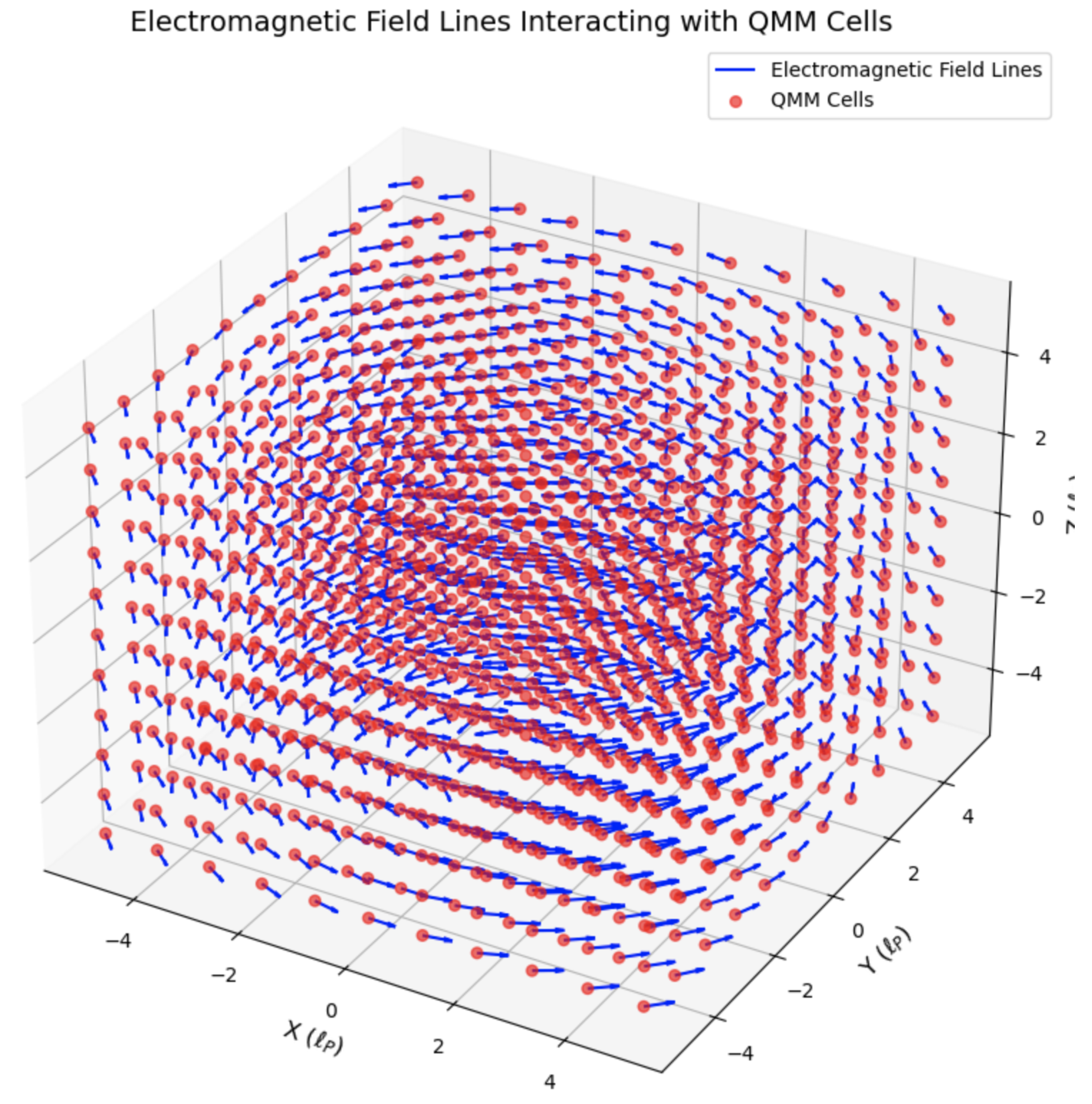

Figure 3 visually represents the role of the interaction Hamiltonian in coupling electromagnetic fields with QMM cells, highlighting the bidirectional flow of information and the preservation of gauge invariance.

A representative form for the electromagnetic interaction Hamiltonian is:

where:

acts on the electromagnetic (and matter) Hilbert spaces as defined in Eq. (

6).

and act on the QMM cell , ensuring the overall operator is gauge invariant and unitarity is preserved.

The ellipsis represents possible higher-order corrections (such as self-interactions or nonlinear effects).

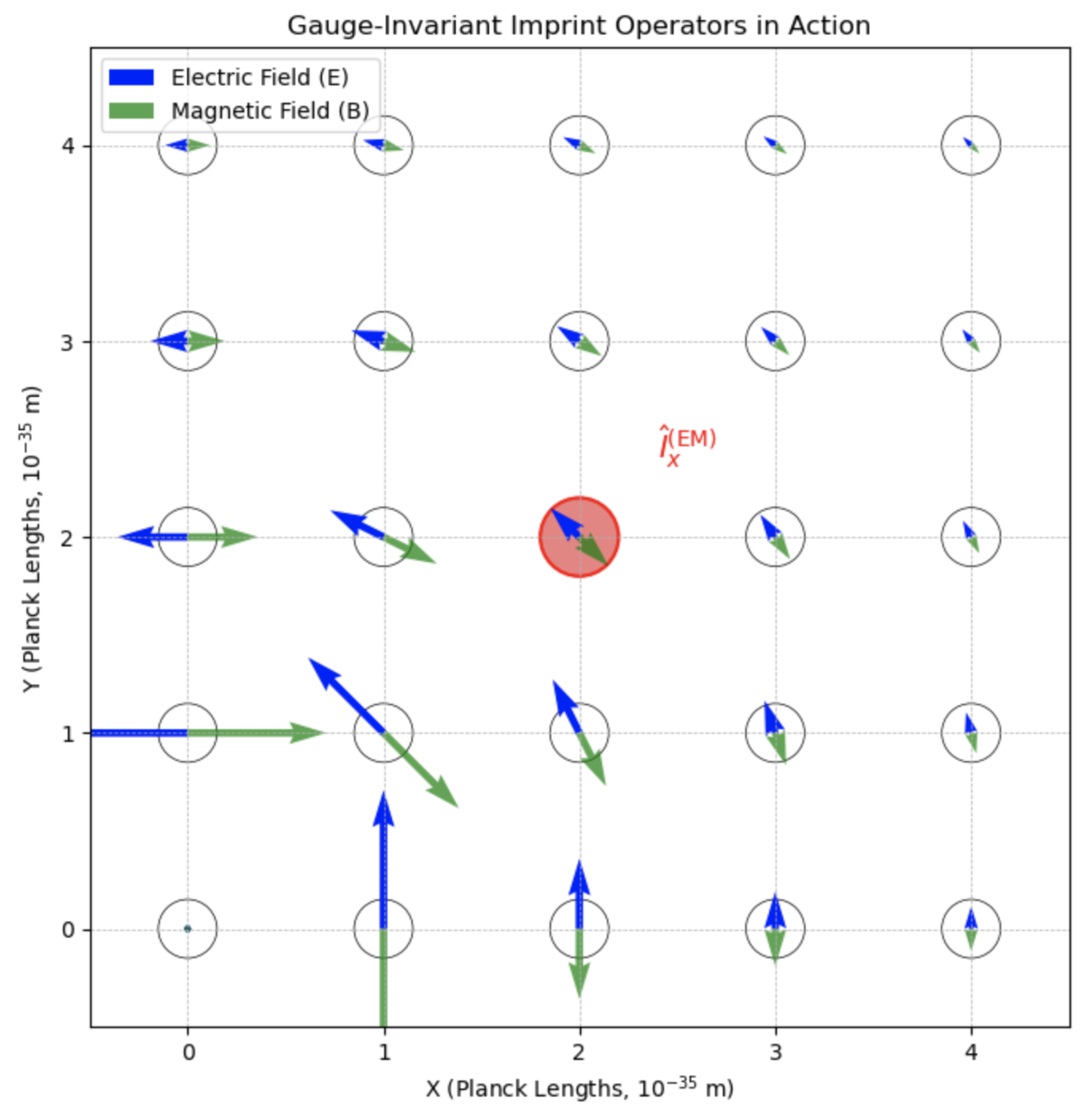

Figure 4 breaks down the components of this interaction Hamiltonian, showing the coupling between QMM cell operators and the electromagnetic field operators.

3.4. Preserving Unitarity, Locality, and Gauge Invariance

The overall Hamiltonian is constructed to be manifestly Hermitian, so that the time evolution operator

remains unitary. Locality is enforced by ensuring that all imprint interactions occur strictly within the same cell

x; any nonlocal correlations develop only via successive, causal interactions between adjacent cells. Gauge invariance is maintained by constructing imprint operators from gauge-invariant or gauge-covariant components; the use of link variables in Eq. (

5) ensures that these operators transform appropriately under local U(1) transformations.

3.5. Implications for Charged Black Holes and QED Vacuum Structure

Embedding electromagnetism into QMM has several significant implications:

Charged Black Hole Evaporation: In charged black holes (e.g., described by the Reissner–Nordström or Kerr–Newman metrics), imprint operators record both gravitational and electromagnetic degrees of freedom near the horizon. As the black hole evaporates, outgoing photons and charged particles interact with these QMM cells, resulting in non-thermal correlations in the Hawking radiation that can, in principle, allow complete retrieval of the initial quantum information.

Vacuum Polarization and Running Couplings: The inherent UV cutoff due to discretization transforms divergent QED loop integrals into finite sums over discrete modes. This may modify the running of the electromagnetic coupling at trans-Planckian energies, potentially leading to a leveling-off or novel behavior of the coupling constant.

Cosmological Photon Fields: In the early universe, the QMM-encoded electromagnetic field may influence magnetogenesis and reionization, leaving observable imprints (such as subtle modifications in CMB polarization or large-scale structure) that could provide indirect evidence of Planck-scale physics.

3.6. Towards a Fully Unified Field Theory

The construction presented here for electromagnetism within the QMM framework is an essential step toward a unified theory of fundamental interactions. Future work will involve:

Non-Abelian Gauge Fields: Extending the formulation to include SU(2) and SU(3) gauge fields requires developing imprint operators capable of capturing non-Abelian field strength tensors and their corresponding link variables.

Full Standard Model Integration: Incorporating quark and lepton fields, their Yukawa couplings, and the Higgs mechanism into the QMM framework to form a comprehensive quantum gravitational description.

Dynamical Quantum Geometry: Ultimately, the QMM framework should transition from an imposed discretization to a dynamical generation of space–time quanta, achieving full background independence.

In summary, we have introduced a detailed scheme for embedding the electromagnetic field into the Quantum Memory Matrix framework by constructing gauge-invariant imprint operators and formulating an interaction Hamiltonian that preserves unitarity, locality, and gauge invariance. This development not only permits the QMM to store and retrieve electromagnetic information but also opens the door to QMM-based treatments of charged black hole evaporation, modified vacuum polarization effects, and distinctive cosmological signatures. In the next section, we explore the physical consequences of these constructions and discuss potential observational tests.

4. Applications to Black Hole Information, Vacuum Structure, and Cosmology

Having extended the QMM framework to incorporate U(1) gauge invariance and electromagnetic fields, we now explore three key arenas in which electromagnetism and gravity intersect: charged black holes, vacuum polarization at trans-Planckian energies, and early-universe cosmology. These applications illustrate how QMM, by encoding quantum information locally at the Planck scale, offers new mechanisms for preserving unitarity and for introducing observable deviations from standard predictions.

4.1. Charged Black Holes and Information Retrieval

In classical general relativity, charged black holes are described by the Reissner–Nordström or Kerr–Newman solutions, which depend solely on the macroscopic parameters: mass

M, charge

Q, and angular momentum

J. According to the no-hair theorems, such black holes seem to lack any detailed internal structure. Within the QMM framework, however, the process of gravitational collapse is accompanied by the imprinting of quantum information in the nearby QMM cells. In particular, when charged matter fields collapse to form a black hole, imprint operators such as

record the local electromagnetic field strengths and charge-current distributions in cells near and even inside the event horizon. This detailed quantum memory, stored in the Hilbert spaces

, supplements the coarse macroscopic parameters and ensures that the complete initial state is not lost.

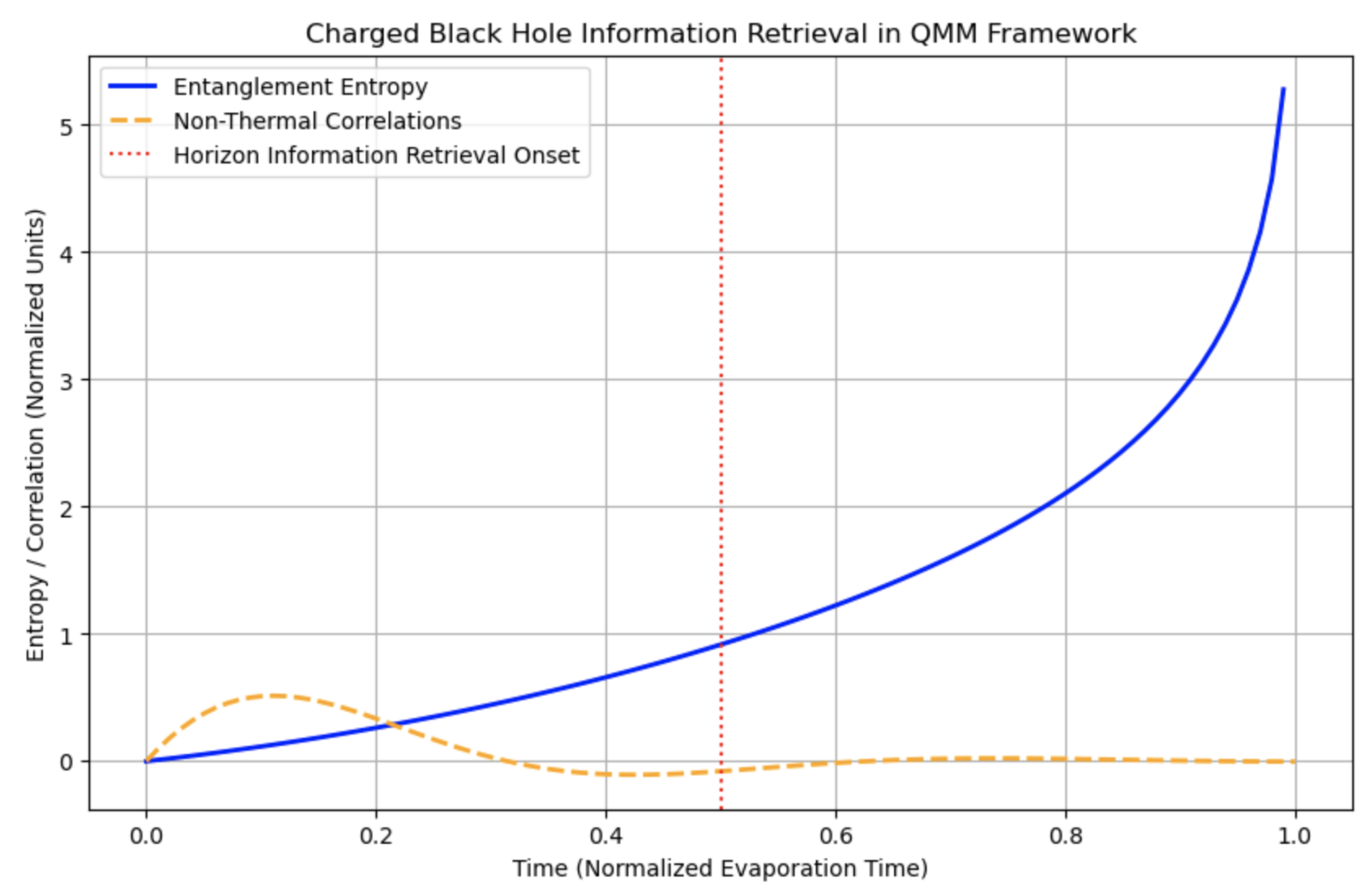

During the evaporation process, Hawking radiation is modified by the presence of these electromagnetic imprints. Outgoing radiation modes (both photons and charged particles) interact with the QMM degrees of freedom, acquiring phase shifts and nontrivial correlations that reflect the initial conditions. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the entanglement entropy of the radiation deviates from the semiclassical Page curve and eventually returns to zero once full evaporation occurs, thus restoring unitarity. Preliminary estimates suggest that the correction to the entanglement entropy may scale as

, where

d is the effective dimension of the local Hilbert space—a parameter that encodes the richness of the quantum imprints. Although a complete dynamical calculation is beyond the present scope, these ideas indicate that charge-dependent correlations in Hawking radiation, if detected, would serve as a signature of QMM-based information retrieval.

4.2. Vacuum Polarization and UV Behavior

A longstanding puzzle in quantum field theory is the appearance of divergences in loop integrals, notably in vacuum polarization diagrams in QED. In the QMM framework, discretization at the Planck scale naturally introduces an ultraviolet cutoff:

where

is the Planck length. With this physical cutoff, integrals over momentum space are replaced by finite sums over discrete modes corresponding to excitations of the QMM cells. Consequently, quantities that diverge in the continuum become finite and well regulated.

This cutoff also affects the running of the electromagnetic coupling . In conventional QED, the effective coupling runs logarithmically with energy scale . However, in QMM the renormalization group (RG) flow is modified at high energies such that, as approaches the Planck scale, the coupling may saturate or exhibit novel behavior. For instance, one may anticipate corrections suppressed by factors of (with the Planck energy and ) so that deviations are negligible at low energies but become significant near the cutoff. Such a scenario suggests a UV-complete version of QED, free from the Landau pole and other divergences.

Furthermore, the discrete structure of QMM implies that zero-point energies and Casimir-like forces, typically derived from integrals over an infinite number of modes, are modified. The finite Hilbert space of each cell truncates the mode sum, potentially leading to a revised estimate of the vacuum energy density. Although a detailed renormalization analysis is required, these effects may contribute to addressing the cosmological constant problem.

4.3. Early-Universe Cosmology and Primordial Fields

The early universe offers another promising arena for testing QMM-induced modifications. In standard cosmology, the origin of large-scale magnetic fields is often attributed to mechanisms of magnetogenesis during inflation or phase transitions. In the QMM framework, the discrete imprinting of electromagnetic fluctuations at the Planck epoch could seed primordial magnetic fields. Quantum fluctuations in the electromagnetic field, once encoded in the QMM cells, might evolve into observable anisotropies or non-Gaussian signatures in the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

For example, if the QMM imprint mechanism introduces deviations in the primordial power spectrum on small scales, these could manifest as subtle modulations in the E-mode or B-mode polarization of the CMB. Preliminary, order-of-magnitude estimates suggest that if the relative deviation in the electromagnetic fluctuations is of order

(with

x determined by the specific QMM parameters), then next-generation CMB experiments (such as LiteBIRD or CMB-S4) or 21-cm line surveys might be sensitive to these effects.

Figure 6 provides a schematic visualization of how primordial electromagnetic fluctuations encoded in QMM cells could leave observable imprints on cosmological scales.

4.4. Analog Models and Prospects for Experimental Tests

Directly probing Planck-scale physics is beyond current experimental capabilities. Nevertheless, laboratory analogs and quantum simulators offer promising routes to test aspects of the QMM framework. For example, engineered U(1) lattice gauge theories in cold-atom systems or superconducting qubit arrays can be designed to mimic the imprinting process. A discretized model with appropriately defined imprint operators,

can be used to study the dynamics of local information encoding and retrieval. By measuring emergent entanglement patterns and correlation functions, such experiments could validate key predictions of the QMM approach in a controlled setting.

Similarly, analog models of event horizons—such as sonic horizons in Bose–Einstein condensates or optical analogs in waveguide arrays—can be used to simulate Hawking-like radiation. In these systems, deviations from thermal behavior that mirror the imprint-and-retrieval cycle predicted by QMM could provide indirect evidence supporting the framework.

4.5. Toward a Unified QMM-Based Field Theory

Ultimately, the goal of the QMM approach is to achieve a fully unified description of gravity, gauge fields, and matter within a single discretized, quantum-information–based framework. The present work, focusing on electromagnetism, represents an essential step toward that goal. Future extensions will involve:

Non-Abelian Extensions: Generalizing the construction to include SU(2) and SU(3) gauge fields requires the development of imprint operators that can handle non-Abelian field strength tensors and the corresponding non-Abelian link variables.

Full Standard Model Integration: Incorporating quark and lepton fields, their Yukawa couplings, and the Higgs sector into the QMM framework will pave the way toward a comprehensive quantum gravity theory encompassing all fundamental interactions.

Dynamical Quantum Geometry: A complete theory would dynamically generate the discretization of space–time rather than imposing it by hand, thereby achieving background independence in a fully unified context.

In summary, by incorporating electromagnetism into the QMM framework, we have examined how charged black hole evaporation, modified vacuum polarization, and early-universe electromagnetic fluctuations can be understood through Planck-scale quantum information encoding. Although experimental verification remains challenging, the proposed laboratory analogs and next-generation cosmological observations may eventually provide indirect tests of these ideas. This work thus lays a conceptual and technical foundation for a unified, finite, and unitary description of all fundamental interactions.

5. Comparison with Existing Approaches and Theoretical Consistency

In the preceding sections, we have introduced the QMM framework as a unifying approach that encodes quantum information locally within Planck-scale cells and integrates gravitational as well as electromagnetic degrees of freedom via gauge-invariant imprint operators. In this section, we compare QMM with several prominent approaches to quantum gravity and the black hole information paradox, emphasizing its advantages and discussing the challenges that remain in achieving a fully unified theory.

5.1. Holography and the Holographic Principle

The holographic principle—exemplified by the AdS/CFT correspondence—asserts that the entire bulk gravitational system can be encoded on a lower-dimensional boundary field theory. In contrast, QMM postulates that every Planck-scale cell in the bulk possesses a finite-dimensional Hilbert space that stores quantum information locally. Key distinctions include:

Bulk versus Boundary Encoding: Holographic approaches confine the fundamental degrees of freedom to a continuum boundary, whereas QMM distributes them throughout the entire bulk, making it applicable even in cosmologies that lack a clear asymptotic boundary.

Locality: Holographic mappings are inherently nonlocal, involving an isomorphism between bulk and boundary Hilbert spaces. In QMM, information is stored and processed locally at each cell, thereby naturally respecting the causal structure of space–time.

Robustness to Asymptotics: By not relying on a specific asymptotic geometry (such as AdS), QMM can be more readily extended to realistic cosmological settings, including de Sitter space.

5.2. ER=EPR, Wormholes, and Nonlocal Mechanisms

The ER=EPR conjecture posits that nonlocal wormhole structures (Einstein–Rosen bridges) are equivalent to quantum entanglement, offering a geometric mechanism for information recovery. QMM, on the other hand:

Enforces a strictly local encoding of information in finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces assigned to each cell, eliminating the need for exotic topological constructs.

Avoids the introduction of nonlocal bridges or wormhole-mediated correlations by attributing both storage and retrieval of information to the imprint operators acting within each cell.

Provides an operational distinction that, in principle, can be tested: if observational data were to reveal only local correlations without signatures of wormhole-like connectivity, it would favor the QMM paradigm.

5.3. Firewalls, Complementarity, and Observer Dependence

The firewall paradox challenges the smooth-horizon picture by suggesting that an infalling observer may encounter a high-energy barrier at the horizon, violating the equivalence principle. QMM addresses this issue by:

Ensuring smooth horizons at the macroscopic level since the imprinting of information occurs only at the Planck scale. There is no need for a firewall because the local storage of information disperses any potentially large energy densities.

Guaranteeing observer-independent encoding of quantum information; the imprints are stored in the QMM cells regardless of the observer’s frame.

Restoring unitarity gradually through local, causal interactions rather than via dramatic, nonlocal phenomena.

5.4. Loop Quantum Gravity, Spin Foams, and Causal Sets

Loop quantum gravity (LQG) and related approaches (such as spin foam models and causal set theory) discretize space–time and quantize its geometry. QMM distinguishes itself by:

Emphasizing Quantum Information: In QMM, each discrete cell not only represents a quantum of geometry but also functions as an active information storage unit, with imprint operators encoding details of field interactions.

Providing a framework for the direct coupling of gauge fields and matter, via explicitly constructed imprint operators—an aspect that is less transparent in LQG or causal set approaches.

Addressing the black hole information paradox by ensuring that local unitarity is preserved through the reversible imprinting and retrieval of quantum data.

5.5. Minimal Length Scenarios and UV Regularization

Minimal length scenarios postulate the existence of a smallest operational scale, typically identified with the Planck length, and often impose this through ad hoc momentum cutoffs. In contrast, QMM inherently incorporates this idea by:

Associating a finite-dimensional Hilbert space with each cell, thereby naturally limiting the resolution of physical processes.

Providing an operational ultraviolet cutoff that regularizes loop integrals and prevents divergences, offering a promising route toward a UV-complete theory.

5.6. Challenges, Open Questions, and Future Directions

Despite its promising features, the QMM framework faces several challenges:

Non-Abelian Gauge Groups: Extending QMM to incorporate non-Abelian fields (e.g., SU(2) and SU(3)) requires the development of imprint operators that accurately capture the complexities of non-Abelian dynamics, including self-interactions and confinement.

Dynamical Quantum Geometry: While the current formulation imposes discretization by hand, a fully dynamical model that generates the space–time lattice from first principles remains an important goal.

Renormalization and Low-Energy Limits: A thorough analysis of how QMM discretization affects renormalization group flows and how it connects with established low-energy effective field theories is needed.

Empirical Signatures: Identifying distinctive and quantitative observational signatures—such as subtle deviations in black hole radiation spectra, modifications of the CMB anisotropy or polarization, or anomalies in gravitational wave signals—remains an ongoing experimental challenge.

5.7. Advantages of QMM and the Path Ahead

QMM offers several compelling strengths:

A local, unitary mechanism for information storage and retrieval that avoids the pitfalls of nonlocality.

A natural and explicit incorporation of gauge symmetries via gauge-invariant imprint operators, which directly encode electromagnetic and, potentially, non-Abelian interactions.

An intrinsic UV cutoff emerging from the finite-dimensionality of the local Hilbert spaces, which offers a pathway to UV completion.

The ultimate goal is to extend QMM to a fully unified framework that includes non-Abelian gauge fields and dynamically generated quantum geometry. Such a theory would be discrete, background-independent, and capable of describing all fundamental interactions in a unified, unitary manner—a framework that could be tested through indirect astrophysical observations and laboratory analog experiments.

By situating QMM alongside holographic approaches, ER=EPR scenarios, LQG/spin foam models, and minimal length theories, we highlight its unique emphasis on local quantum information processing in space–time quanta. While challenges remain, QMM provides a coherent and promising foundation for addressing the black hole information paradox and achieving a full unification of fundamental forces. In the next section, we discuss potential experimental strategies and observational tests that could eventually validate or constrain the QMM paradigm.

6. Experimental and Observational Perspectives

While direct tests of Planck-scale physics remain beyond current technological capabilities, the QMM framework’s unique predictions—stemming from its discrete, locally encoded quantum information structure—may lead to observable deviations from standard quantum field theory, general relativity, and semiclassical black hole thermodynamics. In this section we outline several promising experimental and observational avenues to test QMM-specific signatures, with an emphasis on quantitative estimates and distinctive correlation structures that can differentiate QMM from other new physics scenarios.

6.1. Non-Thermal Features in Black Hole Evaporation

A central prediction of QMM is that Hawking radiation is modified by the imprinting of electromagnetic information on the QMM cells near the horizon. In standard semiclassical analyses, Hawking radiation is nearly thermal; however, if QMM imprint operators encode detailed charge and field configurations, outgoing quanta (photons and charged particles) acquire non-thermal correlations. In particular, one may expect deviations in the energy spectrum or in the entanglement entropy evolution. Preliminary back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that if the effective dimension d of a QMM cell induces corrections of order , then for modest values of d (e.g., –100) the relative correction to the thermal spectrum may lie in the few-percent range. Although such small deviations would be challenging to detect in astrophysical black holes due to low temperatures and environmental noise, primordial black holes (PBHs) nearing the end of their lifetimes could emit high-energy gamma rays or cosmic rays with discernible non-thermal features. Future gamma-ray observatories (such as CTA or advanced Fermi instruments) and cosmic-ray detectors may thus constrain or reveal such QMM-induced deviations, even if only by placing upper bounds on the fraction of PBHs that exhibit these effects.

Figure 7.

Schematic depiction of charged black hole formation and the subsequent imprinting of electromagnetic data into QMM cells near the horizon. This mechanism is expected to induce non-thermal correlations in the emitted Hawking radiation.

Figure 7.

Schematic depiction of charged black hole formation and the subsequent imprinting of electromagnetic data into QMM cells near the horizon. This mechanism is expected to induce non-thermal correlations in the emitted Hawking radiation.

Gravitational wave detectors (LIGO, Virgo, and future observatories like LISA, the Einstein Telescope, and Cosmic Explorer) may also be sensitive to subtle modifications of the quasi-normal mode spectrum during the post-merger ringdown phase. QMM-induced corrections to the horizon’s quantum memory could introduce phase shifts or amplitude modulations at the percent level in the ringdown waveform—a signal that, although extremely challenging to extract, would offer a direct window into horizon-scale information recovery.

6.2. Cosmic Microwave Background and Large-Scale Structure

The imprinting of electromagnetic fields in QMM during the early universe could leave signatures in cosmological observables. In particular, if QMM discretization modifies the primordial power spectrum of electromagnetic fluctuations, this may manifest as:

Non-Gaussian Correlations: Deviations from the Gaussian statistics predicted by standard inflation, potentially detectable in high-sensitivity measurements of the CMB’s E-mode and B-mode polarization.

Scale-Dependent Spectral Features: Slight modulations or running in the spectral index at scales approaching the horizon at recombination, with estimated fractional deviations on the order of (where x is model-dependent, typically estimated to be in the range 2–3).

Moreover, QMM effects could subtly alter magnetogenesis processes, affecting the coherence length and strength of primordial magnetic fields. These alterations might be observed via Faraday rotation measurements or gamma-ray observations of blazar halos. Upcoming missions such as LiteBIRD, CMB-S4, and advanced 21-cm line surveys could thus provide indirect tests of QMM-induced modifications.

6.3. Laboratory Analog Experiments and Quantum Simulators

Although direct experiments at the Planck scale are infeasible, laboratory analogs offer a promising means to test key aspects of the QMM hypothesis. For instance:

Sonic and Optical Horizons: Experiments in Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs) and optical waveguide arrays can simulate event horizons. By engineering local imprint-like interactions in these systems, one can study deviations from thermal emission analogous to those predicted by QMM.

Quantum Simulators: Advances in quantum computing platforms (such as Rydberg atom arrays, trapped ions, or superconducting qubits) allow the simulation of discretized U(1) lattice gauge theories. In such systems, one can define operators on each lattice site that mimic QMM imprint operators and monitor the resulting entanglement dynamics. Observation of emergent non-thermal correlation patterns in these simulators would serve as a proof-of-concept for the imprint-and-retrieval cycle central to QMM.

These analog experiments not only provide a test bed for theoretical ideas but may also help refine the quantitative predictions of the QMM framework.

6.4. Distinguishing QMM Effects from Other New Physics

A critical challenge is to differentiate QMM-induced deviations from those arising in alternative theories, such as wormhole-mediated ER=EPR scenarios or extra-dimensional models. The key diagnostic of QMM is its strictly local, gauge-invariant imprint mechanism:

QMM predicts specific correlation structures in Hawking radiation and cosmological observables that are tied to the finite-dimensional Hilbert space of each cell.

In contrast, models invoking nonlocal processes typically lead to signatures such as long-range entanglement patterns or topological effects not present in the QMM description.

Thus, if observational anomalies—whether in black hole radiation spectra, gravitational wave ringdowns, or CMB polarization—can be consistently explained by local modifications and correlated with the expected QMM parameters, this would favor the QMM framework over more exotic alternatives.

6.5. Long-Term Outlook: Indirect Probes and Future Missions

While direct detection of Planck-scale physics remains a distant goal, a multi-pronged strategy combining astrophysical observations, precision cosmology, and laboratory analog experiments holds promise. High-sensitivity gamma-ray telescopes may eventually detect non-thermal features in PBH evaporation spectra, and next-generation gravitational wave observatories might reveal minute deviations in ringdown waveforms. At the same time, advanced CMB and 21-cm surveys could identify subtle polarization or non-Gaussian signals consistent with QMM-induced discretization. Finally, quantum simulators may reproduce the imprint-and-retrieval dynamics in controlled settings, providing a complementary route to validating the QMM paradigm.

Collectively, these efforts could not only constrain the parameter space of the QMM framework but also lend indirect support to the notion that space–time itself functions as a dynamic, locally encoded information reservoir—a cornerstone of our unified approach to gravity and gauge fields.

7. Conclusion

We have developed an extended QMM framework that incorporates electromagnetism into a discretized quantum gravitational setting. By quantizing space–time into finite-sized cells and embedding quantum information directly within their finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, our approach enables both gravitational and electromagnetic fields to leave detailed imprints at the Planck scale. These imprints act as local information reservoirs that preserve unitarity and record the full quantum history of interactions, thereby offering an alternative to nonlocal mechanisms such as wormholes. In particular, by rigorously integrating U(1) gauge invariance through the construction of gauge-invariant imprint operators, we have demonstrated how even charged black holes can evaporate unitarily, with non-thermal correlations in the emitted radiation gradually revealing the underlying quantum microstates.

Moreover, the QMM framework naturally introduces an ultraviolet cutoff, which regularizes otherwise divergent loop integrals and may modify the running of the electromagnetic coupling at trans-Planckian energies. Such modifications open new perspectives on vacuum polarization and charge renormalization, and they suggest that observable signatures—ranging from deviations in the Hawking radiation spectrum of primordial black holes to subtle non-Gaussian features in the cosmic microwave background—could provide indirect tests of Planck-scale physics. Laboratory analog experiments and quantum simulators of discretized gauge theories further offer promising avenues for probing the imprint-and-retrieval dynamics predicted by QMM in controlled settings. While our work lays a theoretically sound foundation, several open questions remain. Future efforts will focus on extending the framework to incorporate non-Abelian gauge fields and full Standard Model interactions, developing a dynamical mechanism for the emergence of space–time discretization, and formulating a comprehensive renormalization scheme that connects high-energy QMM predictions with established low-energy effective theories. We anticipate that continued research in these directions will deepen our understanding of how quantum information and geometry coalesce into a unified description of fundamental physics.

Author Contributions

F.N. developed the research concept and prepared the initial manuscript draft. V.V. and E.M. critically reviewed the manuscript, contributed to the formalism, and aided in its revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. All theoretical results are derived from the proposed Quantum Memory Matrix framework, and no datasets are associated with this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rovelli, C. Loop Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 1998, 1, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Class. Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53–R152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Black Hole Entropy from Loop Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3288–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Pawlowski, T.; Singh, P. Quantum Nature of the Big Bang: Improved Dynamics. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maldacena, J. The Large-N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Lippert, M. The Information Paradox and the Black Hole Partition Function. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 024006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet Divergences in Quantum Theories of Gravitation. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 790–831. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, M.; Saueressig, F. Renormalization Group Flow of Quantum Einstein Gravity in the Einstein-Hilbert Truncation. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 65, 065016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of Predictability in Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on Black-Hole Evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J. Do Black Holes Destroy Information? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 1992, 1, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional Reduction in Quantum Gravity. Conf. Proc. C 1993, 930308, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball Proposal for Black Holes: An Elementary Review. Fortschr. Phys. 2005, 53, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool Horizons for Entangled Black Holes. Fortschr. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Brasher, R.; Marx, E. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, F.J. Divergent Series in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 631–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Koul, R.K.; Lee, J.; Sorkin, R.D. A Quantum Source of Entropy for Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 1987, 34, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal Length Scale Scenarios for Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 2013, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G. Confinement of Quarks. Physical Review D 1974, 10, 2445–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).