1. Introduction

The inflationary scenario was originally proposed in cosmology to address several fundamental inconsistencies in the original Big Bang theory, which assumes that the universe began expanding at a relatively low rate. Consequently, issues such as the horizon problem, the flatness problem, and the monopole problem [

1] remained unresolved within the frame work of the "hot Big Bang" model until the advent of the inflationary paradigm [

2,

3].

Focusing on the horizon problem [

4], causality-based arguments highlight the difficulty of explaining the observed isotropy and homogeneity of the universe on large scales, including the minute anisotropies in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), without invoking a period of rapid exponential expansion.

Inflation proposes that the early universe underwent such a phase, expanding far beyond the observable Hubble radius within a tiny fraction of a second [

5]. Once inflation ended, the physical Hubble radius began to grow, gradually encompassing regions that now define the observable universe over cosmic time. The mechanism driving the exponential expansion is typically modeled (for simplicity) by a single slowly rolling scalar field known as the

inflaton, whose fundamental nature remains unknown.

Thus, according to the inflationary paradigm, both primordial scalar (matter density) perturbations and tensor (metric) perturbations generated temperature anisotropies superimposed on an otherwise isotropic and homogeneous background. These fluctuations were enormously amplified during an inflationary phase that are observable today, e.g., in the CMB. Notice, however, that tensor modes contribute to a much lesser extent than scalar modes, making it difficult to disentangle their respective contributions based on temperature anisotropies alone. In contrast, primordial gravitational waves (PGWs) are expected to produce B-mode polarization in the CMB, whereas scalar fluctuations do not (at first order in perturbation theory). This is why the detection of PGWs is often referred to as the

Holy Grail of inflationary cosmology [

6].

However, sources other than PGWs can also induce B-mode polarization, such as gravitational lensing or foreground contamination of Galactic origin, and their contributions must be carefully separated from those of PGWs before any discovery claim can be made. In this regard, it is crucial to point out that the expected pattern generated by PGWs in the CMB power spectrum peaks both at small angular scales (corresponding to multipoles of order ) and at large angular scales (corresponding to low multipoles, of order ). We shall focus on the latter, which, besides its relevance for PGWs, could also provide information on the topology of the early universe, this constituting the main goal of this paper.

A standard approach to studying PGWs is to parametrize the tensor power spectrum in terms of the tensor-to-scalar ratio,

r, and the spectral index,

, and constrain them using measurements of the temperature and polarization spectra. In this paper, following previous work [

7,

8], we analyze and extend an additional observable related to the shape (i.e., the even-odd (im)balance of multipoles) of the temperature and polarization angular correlations, which could potentially reveal the topological structure of the early universe, as already claimed in a different context [

9].

To this aim, we first review the CMB temperature anisotropies by revisiting and extending previous work, further developing the underlying a specific theoretical framework during the GUT epoch, before inflation. Later we shall examine future precision measurement fo B-mode polarizatio by the

LiteBIRD mission [

10].

2. Temperature Anisotropies

One of the most outstanding results from the CMB measurements is its extraordinary homogeneity across the full sky, reflecting the homogeneity of the initial source of perturbations itself, extending over the whole visible universe today. This fact, in turn, implies isotropy along all directions of sky.

However, small but significant departures from this behavior contain important information about the early stages of the universe for both scalar and tensor modes contributing to the CMB. Still, correlations between temperature anisotropies at different points in the sky depend only on the angle between them. Then, the two-point angular correlation function is the appropriate tool for analyzing these fluctuations. It is defined as the ensemble product of the CMB temperature differences

with respect to the average temperature from all pairs of directions in the sky defined by unitary vectors

and

:

where

is the angle defined by the scalar product

.

Assuming isotropy,

is usually expanded in terms of Legendre polynomials as

where

is the order-

ℓ Legendre polynomial, and the sum extends from

since the monopole and dipole contributions have been removed from the analysis.

In the following, we will ignore the transfer function and consider only the Sachs-Wolfe effect [

11] as the main source of primary (scalar) anisotropies, as expected on scales larger than

. Hence, the multipole coefficients of Eq.

2 can be computed in the limit of a flat power spectrum, as

where

is the spherical

ℓ-Bessel function, and

stands for a normalization factor to be determined from the fit to observational data. The resulting theoretical curve for

compared to measured data is far from satisfactory and further action is required [

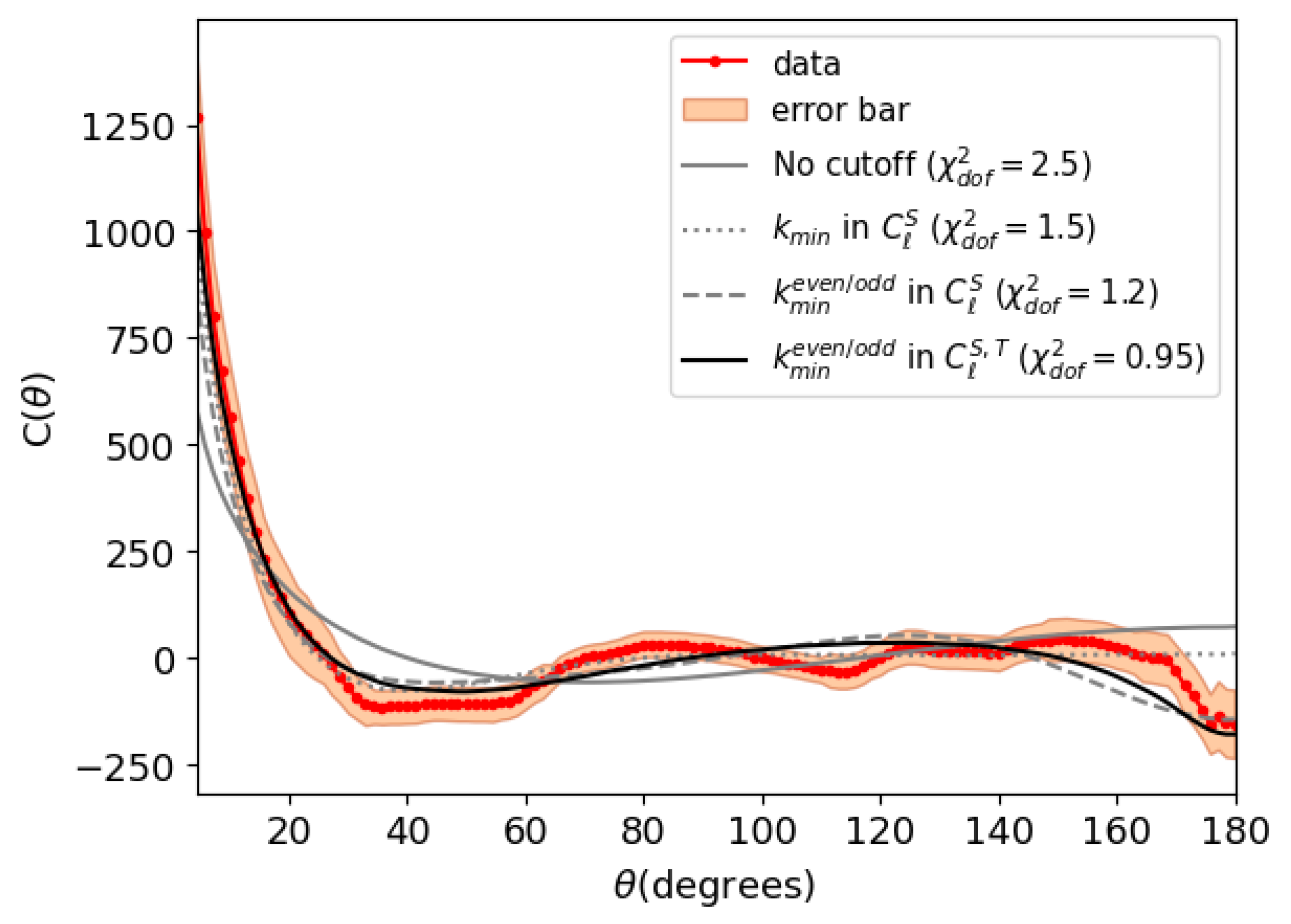

12].

2.1. Infrared Cutoff in the Scalar Power Spectrum

In order to improve the above-mentioned quite unsatisfactory fit, an infrared (IR) cutoff

was introduced to the CMB power scalar spectrum in Ref. [

13], implying a lower limit

in the integral of the multipole,

coefficients in Eq.

3:

where

and

denotes the co-moving distance to the last scattering surface, typically about 14,000 Mpc.

The authors of ref. [

13] introduced the IR cutoff essentially in a heuristic way whose purpose was removing the unseen (positive) correlations at large angle expected in standard cosmology. Thus, fitting the

correlation function to

Planck data, they obtained

[

13,

14], corresponding to

A compatible result with a single cutoff was also obtained in Ref. [

15], taking into account the odd-parity preference indicated by

Planck data.

2.2. Double Infrared Cutoff in the Scalar Power Spectrum

However, the odd-parity dominance [

16,

17,

18,

19] could not be fully achieved using a single cutoff, whose main effect on the multipole coefficients is limited to the first few terms. Therefore, in Ref. [

7], a doublet of IR cutoffs, rather than a single cutoff, was introduced to enhance the differing impact of the lower limits of the integral on even and odd

ℓ-values. Let us adopt the same notation as in Ref.[

7] and write

corresponding to two IR cutoffs (instead of one) in the scalar power spectrum, to be associated with the odd/even multipoles.

Taking into account the two IR cutoffs, we rewrite the integral of Eq.

6 as

where The lower limits of the integral

(defined in

6) affect differently the odd and even multipole coefficients (only up to

, respectively), thereby altering the shape of

.

From a best

fit of

to the

Planck data on temperature anisotropies, the following values were obtained in [

7]:

and

. In the next section, we revisit these lower cutoffs, this time including tensor modes, which yield numerical values that do not differ significantly from the previous ones.

2.3. Incorporating Tensor Modes into the Analysis

In addition to the dominant scalar modes, the contribution of tensor modes to the temperature anisotropies of the CMB has been examined in a series of previous papers [

7,

8], with particular focus on angular correlations. To improve the fit to observational data from the Planck mission, a set of IR cutoffs was introduced into both the primordial scalar and tensor power spectra.

The corresponding multipole coefficients for temperature correlations,

, are given by [

20]

distinguishing odd and even modes by different lower cutoffs, as for the scalar case.

Despite the rather modest effect of tensor modes on temperature angular correlations, their inclusion in the analysis leads to a slight but noticeable improvement in the best

fit of of

to the

Planck 2018 dataset, especially on large angles (

), as discussed in Ref.[

8]. Also the associated parity statistic measuring the deviation from odd-even balance and the odd-parity preference at large angle, improves once tensor modes are included in our analysis [

8].

Needless to say, these improvements are not statistically significant enough on their own to support any definitive claim. However, they do motivate an extension of our study to include CMB polarization. We address this issue after introducing the theoretical framework based on a Kaluza–Klein extra dimension.

3. Early Universe Topology from a Kaluza-Klein Model

In this section we provide a specific scenario such that those cutoffs in the angular power spectra emerge naturally from the theoretical framework. We rely on a simple model in five-dimensions (5D) of space-time, which leads to a 4D low energy theory when the fifth dimension is compactified to a circle of radius R at some time of the remote past, close to the exit of the Planck epoch. This compactification leads to the appearance of 4D Kaluza-Klein (KK) towers whose mass spectra dictate the cutoffs of the Fourier expansion of the fields, relevant in our study on the CMB.

The inverse of the radius of the compactified extra dimension

sets the lowest mass of the KK tower, acting as an IR cutoff for fields in our 4D world. On the other hand, the origin of the IR doublet could be related to the fulfillment of different combinations of (Dirichlet/Neumann) boundary conditions (BCs) [

8], following orbifold compactification.

3.1. Orbifold Compactification of the Fifth Dimension

As previously anticipated, we postulate that the fifth extra dimension of the 5D world becomes compactified just before the onset of inflation. For the moment, we will also assume that the five-dimensional spacetime is described by a flat geometry, specifically with a 5D Minkowski metric:

where

i=1, 2 and 3, and

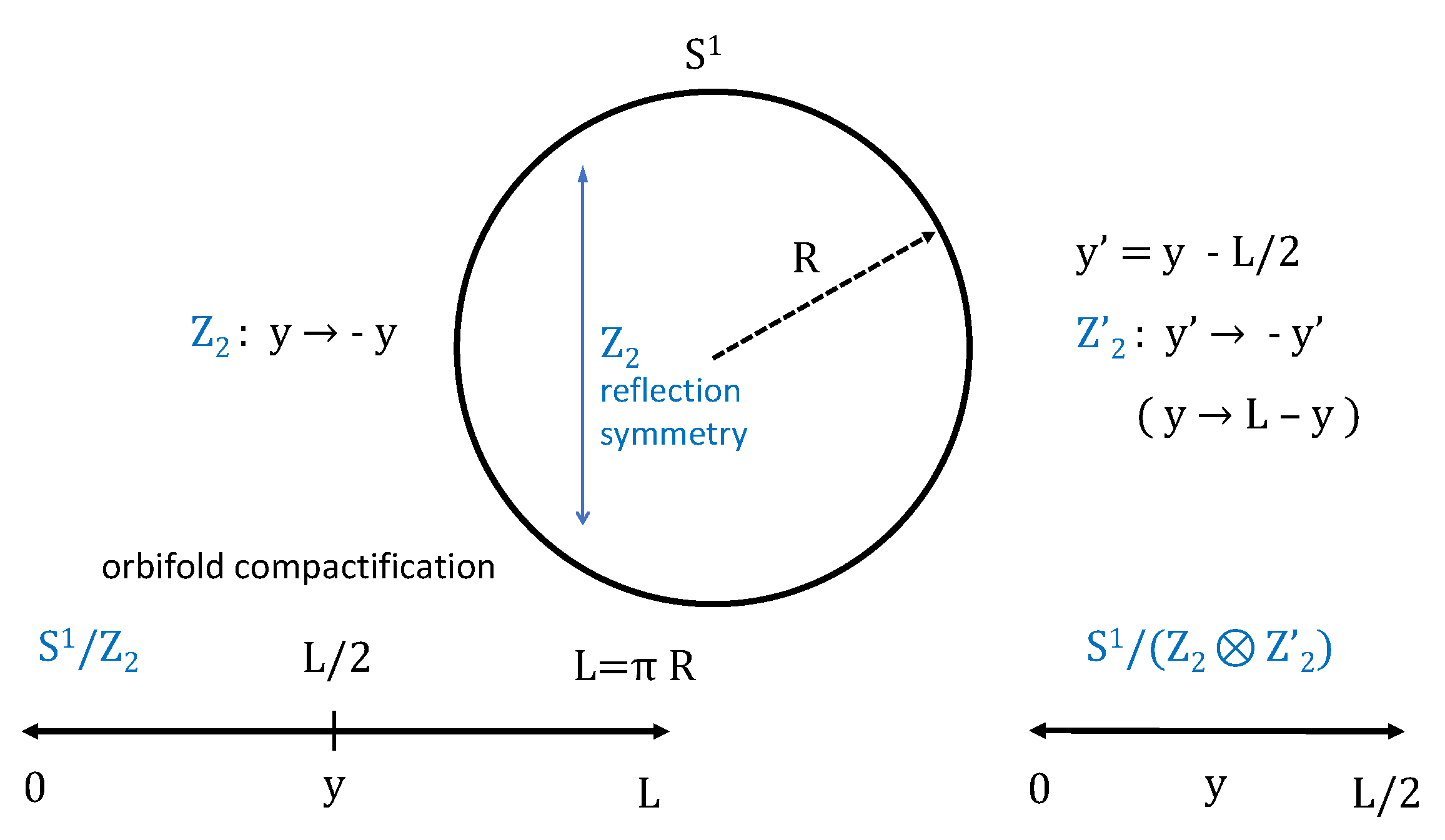

y denotes the 5-th dimension. Following orbifold compactification [

21], the fifth dimension ranges over the interval

, where

(see

Figure 2)· Moreover, only scalar fields, and no fermionic fields [

22] will be considered on our approach

Scalar fields propagating in this geometry can be factorized in the so-called KK decomposition as

where the 4D field

satisfies the Klein-Gordon equation of motion, while

satisfies a wavefunction equation which depends on the geometry and BCs at both ends of the interval. Under certain assumptions, the parity of the KK profile

determines the 3D parity of the corresponding 4D component

, making it a key element in our analysis.

Our later development can proceed in two ways:

- (i)

orbifold compactification requiring invariance under some parity operations in the fifth dimension. In particular, we will consider

orbifold (see

Figure 2).

- (ii)

Neumann/Dirichlet BCs at both ends of the compactified dimension. Both procedures actually lead to the same physics as we shall see.

By defining additional parities on the compactified extra dimension beyond the symmetry:

, distinct topologies are obtained, ultimately leading to observational consequences in the 4D world. Here, we will focus on a minimal

orbifold in a 5D space-time, which has been already applied to the GUT epoch [

23]:

: reflection , with a fixed point at

: defining , followed by amounts to the reflection , with a fixed point at .

In our setup, the symmetry provides a global discrete label for the 4D fields, ultimately determining the 3D spatial parity of the 4D scalar and tensor modes, and, in turn, their correspondence to even and odd multipoles in the expansion of the angular correlation functions.

4. Boundary Conditions on a Flat Geometry

Alternatively, one can define a theory directly on the segment , where . By choosing appropriate Neumann and Dirichlet BCs at the endpoints, one can mimic the mode spectrum and parity structure of the orbifold compactification yielding the same physics. Let us write down the KK mode wavefunctions for a scalar field compactified on a segment , with under the four possible combinations of Neumann (N) and Dirichlet (D) BCs at the end points.

-

Neumann-Neumann (+,+) with BCs: .

The set of solutions and allowed mass spectrum (including zero mode) can be written as:

Note that all modes are even under both and . The combined parity turns out to be even.

-

Dirichlet-Dirichlet (-,-) with BCs: ,

Solutions and mass spectrum (no zero mode):

The combined parity is even.

-

Neumann-Dirichlet (+,-) with BCs: ,

Solutions and mass spectrum (no zero mode):

The combined parity is odd.

-

Dirichlet-Neumann (-,+). BCs: ,

Solutions and mass spectrum (no zero mode):

The combined parity is odd.

Thereby, the mass spectrum of scalar fields with BCs

and

would be related as follows,

For 5D fields, the lowest mass in their spectrum (

) provides a natural IR cutoff for their physical behaviour in 4D. The IR cutoffs represented by

are thus related by a simple factor 2,

This ratio matches the value obtained for scalar modes in our phenomenological analysis of temperature angular correlations in the CMB. In a prior study [

7], the

magical" value equal to 2 was interpreted in terms of periodic and anti-periodic boundary conditions satisfied by a Dirac field.

4.1. Tensor Modes

As previously mentioned, tensor modes of the CMB, generated by metric perturbations in the early universe but imprinted much later, contribute to both temperature and polarization anisotropies, albeit to different degrees. Despite their distinct origins and natures, scalar and tensor perturbations will be treated within a unified theoretical framework based on an additional KK dimension, as developed below.

Indeed, spin-two fields are unavoidably present in any KK spacetime geometry. From the four-dimensional perspective, the KK decomposition of the spin-two graviton field includes a massless mode (responsible for mediating 4D gravity) as well as a tower of massive excited states (the KK gravitons). By imposing the same boundary conditions as in the scalar case, one can write down the following ratio of the lowest massive modes with different parity:

where

denotes the first excited (non-zero mass,

) KK state.

Thus, we can write for the tensor IR cutoffs he equivalent relation to Eq.

16:

where their numerical values are again basically set by

. Therefore one naively expects:

in flat geometries. However, still there is a way of modifying the masses of tensor modes (and hence the IR cutoffs) in warped geometries, as discussed below.

5. Warped Geometries

The above construction can be generalized to metrics with curvature in the extra-dimension, commonly called

warped geometries [

21,

26,

27], employed in different fields and applications (see, e.g., [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Warped geometries can be parametrized in terms of a warp factor

in a factorizable metric

where conformal coordinates have been used. For example,

in the Randall-Sundrum model [

26].

The following sum rule allows one to obtain the behavior of the even and odd parity KK towers in warped extra-dimensions for scalar modes,

where

and

are related to the AdS curvature and the warp factor;

, see [

35] for more details. Using this sum rule, we recover the relation of Eq.

20 for the flat metric case, where

. In general, the above ratio

continues to hold for unwarped geometries, so we write for scalar modes

, or equivalently

for computation of the multipole coefficients. Note that

q captures the influence of the warped geometry on the mass spectrum (in particular on the lowest excited states), such that

for a flat geometry while

is typically expected for the warped ones. A relative small

q value is expected in mild warped extra-dimensions [

36,

37].

5.1. tensor Modes

Tensor modes would display a similar behavior in the presence of curvature, as explained in Refs. [

38,

39], so that we shall write

, or equivalently

.

Moreover, another hierarchy between the tensor and scalar IR cutoffs can be established as: , where corresponds to a flat geometry. Similarly, one can define Depending on the model, Q or/and could be smaller or larger than unity.

To summarize, the following relations can be established:

where, as already commented,

applies to flat geometries, while

and/or

applies to warped geometries. It is interesting to highlight the relation between the above ratios:

Any observational signature of the postulated topology via angular correlations would require . This condition is easily achieved if the behaviors of both Q and remain similar when transitioning from a flat geometry to a warped one.

6. Even and Odd Multipole Contributions to the 2-Point Correlation Angular Function

In light of the discussion in

Section 4 and 5, let us reexamine the association between the odd/even multipoles (arising in the expansion of the two-point correlation function in Eq.

2) and the corresponding odd/even IR cutoffs, as well as their subsequent extension to B-mode polarization.

To this end, as previously mentioned, we assume for simplicity a 5D scalar field

, whose 4D component

represents a scalar inflaton field. Accordingly, the parity of a 4D KK mode under 3D spatial reflections

must satisfy:

where

is the intrinsic spatial parity of the 5D field,

is the orbifold parity of the KK wavefunction

, and

is the resulting 3D parity of the 4D field mode

. Thus, the relationship between the parity of the multipole terms and the corresponding IR cutoffs used to compute the coefficients

becomes well justified

7. B-Mode Polarization Versus Early Universe Topology

B-mode polarization is often regarded as the smoking gun for PGWs and, by extension, for inflation itself. Upcoming high-precision measurements, such as those anticipated from the

LiteBIRD mission [

10], are expected to provide extremely valuable insights into the early universe, enabling the discrimination between different cosmological scenarios, those related to the inflationary epoch. In Ref.[

36], the authors already studied focused on the impact of a truncated primordial power spectrum on B-mode polarization of CMB, beyond temperature at large-angle correlations.

Moreover, measurements from LiteBIRD may also shed light on the quantum nature of gravity and uncover potential new physics beyond the Standard Model of particles and interactions. In particular, the imprints on the polarization of CMB photons are expected to carry information from epochs preceding inflation. These signals could potentially complement, or even surpass, the information derived from temperature angular correlations, especially regarding the topology of the universe, which is the central focus of this work.

Not all sources of B-mode polarization in the CMB originate from PGWs. On the one hand, gravitational lensing can convert part of the E-mode polarization (generated by density fluctuations) into B-modes, with a peak at large values of

ℓ. On the other hand, additional foreground sources, such as thermal emission from interstellar dust and synchrotron radiation from electrons spiraling in the Galactic magnetic field, also contribute. These foreground signals, however, exhibit a frequency dependence that differs significantly from that of the primordial signal, likely enabling their suppression through multi-frequency observations [

10].

Next, we study the influence of one or more IR cutoffs on the BB angular correlations, focusing on small

ℓ values, in order to examine their impact on the tensor power spectrum. This analysis follows the same approach and methodology as in Ref. [

40,

41].

Following common practice and already done for temperature anisotropies, we expand the BB two-point correlation function in terms of Legendre polynomials as

where the

factor has been extracted from the respective multipole term to show the impact of the lower cutoff(s) on the behavior of the curve, slightly different from

. Indeed, this factor may conceal the influence of the cutoff as it enhances the dependence of

on higher

ℓ-values. This would be especially the case for a single IR cutoff (see Ref.[

40]), but the influence of the two tensor IR cutoffs turns out to be potentially observable. To this end, our analysis focuses on small

ℓ values, i.e.,

. Moreover, beyond this range, contributions from non-cosmological sources, such as gravitational lensing, become dominant and are therefore removed.

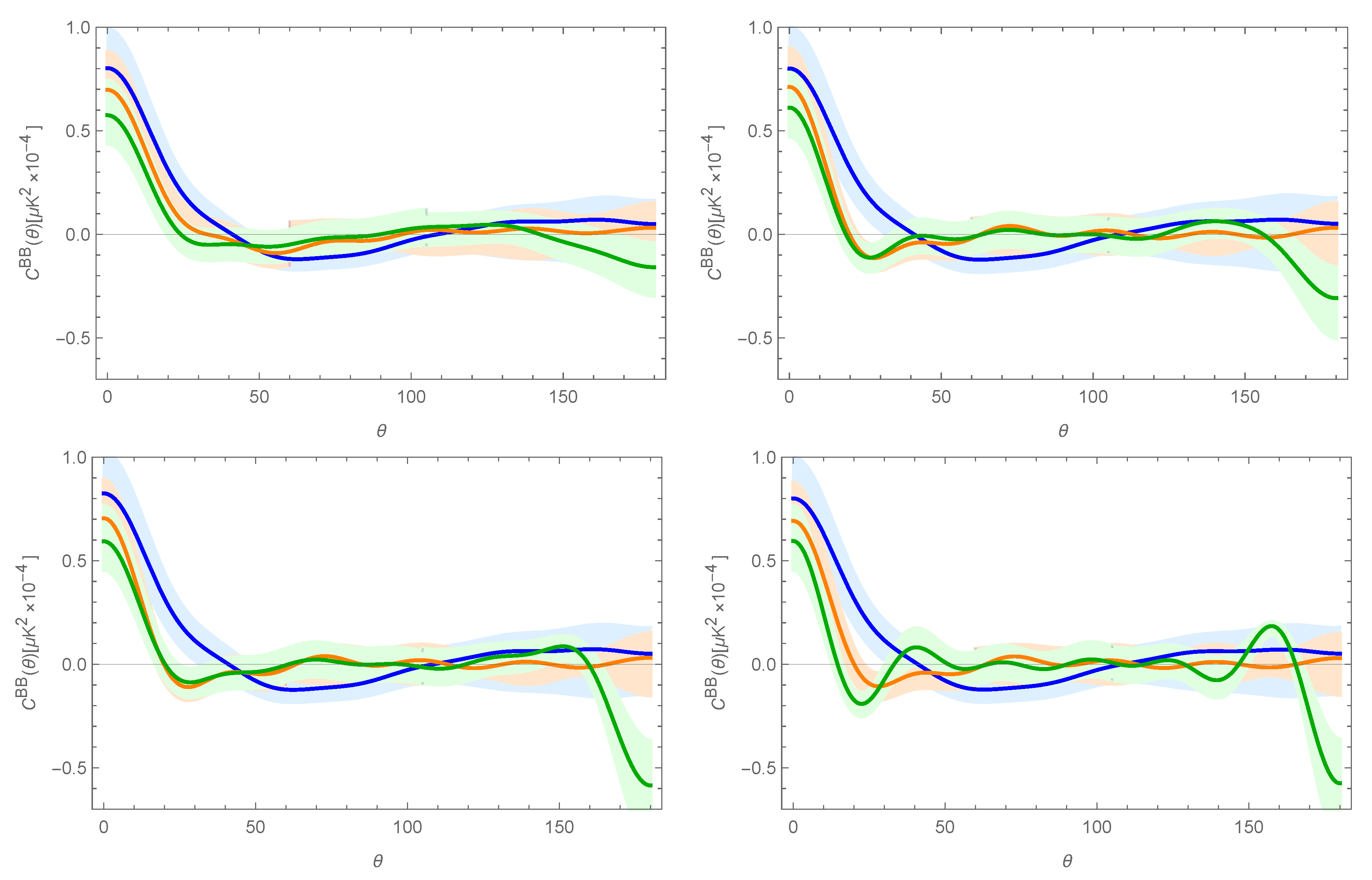

In

Figure 3, we present a set of plots of

(for

) as a function of

, for various values of

(tensor) and a fixed tensor-to-scalar ratio of

. Each plot includes curves corresponding to the three scenarios considered in this study: (a) no IR cutoff (blue), (b) a single IR cutoff (red), and (c) two IR cutoff doublets (green). One-

error bands are shown for all curves to assess the discrimination power of our approach.

Upon inspection, one can clearly observe distinct patterns in the behavior of

, particularly at large angular scales. A large value of

effectively removes the contribution from even multipoles, causing

to become dominated by odd multipole contributions. This results in a downward trend in the B-mode polarization, analogous to the effect observed in the temperature correlations shown in

Figure 1. The eventual detection of such a feature would provide strong support for the proposal advanced in this and previous works [

7,

8], which aims to probe the topology of the early universe through angular correlations in the CMB.

Let us finally remark that the angular correlation function contains essentially the same information as the tensor power spectrum, since both are derived from the same set of multipole coefficients. However, the former offers a clearer view of the large-angle (low-ℓ) region, where the preference for odd-parity multipoles emerges as a combined and cumulative effect of several odd and even multipoles. This can ultimately facilitate physical observation and interpretation.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we first reviewed the significant deviation of the observed temperature two-point correlation function,

, from the predictions of the standard cosmological model, with a focus on large angular scales, where there is a lack of positive correlations accompanied by a marked change in slope toward negative values, as shown in

Figure 1.

Building on previous work [

8,

15], we developed further a possible physical origin for the observed behavior of the temperature angular correlations, now including polarization correlations. Again, two IR cutoffs are introduced in both the scalar and tensor power spectra, theoretically interpreted as consequences of a specific topology of the early universe.

In particular, we employed a model featuring a Kaluza-Klein setup, compactified during the GUT epoch and subject to Neumann and Dirichlet BCs on the extra dimension. As a result, two doublets of scalar and tensor IR cutoffs naturally emerge from the KK tower(s), associated with the even and odd parity transformation of multipoles in the Legendre expansion of the two-point correlation functions.

Admittedly, a simple KK model was invoked, while many other possibilities remain open, either in flat or warped geometries. Nevertheless, the key motivation of this work, i.e. the introduction of IR cutoff doublets in the power spectra, is adequately captured by our basic theoretical framework.

Finally, we examined the B-mode polarization using the two-point correlation function

as a potential tool to distinguish between different possible topologies of the early universe. Of course, in general, new physics that violates parity can be probed through other frameworks [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. However, our proposal offers specific signatures as shown in this paper. As with the temperature anisotropies, introducing two distinct IR cutoffs in the tensor power spectrum produces a markedly different pattern in the plot of

as a function of

, particularly at large angular scales.

On the other hand, it is important to emphasize that temperature and polarization anisotropies of the CMB represent two distinct and independent types of measurements of the same early universe. Therefore, an eventual coincidence in an odd-parity preference would be unlikely to arise from a statistical fluke.

Based on our analysis, we conclude that forthcoming high-precision data from

LiteBIRD [

10] on the B-mode polarization of the CMB could shed light on the tantalizing prospect of testing the topology of the early universe, in addition to enabling the detection of primordial gravitational waves, potentially confirming inflation.

Acknowledgments

I warmly thank Jingwei Liu and Verónica Sanz for illuminating discussions. I also acknowledge support from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigacion under Grant PID2023-151418NB-I00 funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ FEDER, UE and by GV under grant CIPROM/2022/36.

References

- Kolb, E.W.; Turner, M. The early universe, Fontiers in Physics, Westview Press 1994.

- Guth, A. H. , Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D, 23(2), 347–356. [CrossRef]

- Linde, A. D. , A new inflationary universe scenario: A possible solution of the horizon, flatness, homogeneity, isotropy and primordial monopole problems. Physics Letters B, 108(6), 389–393. [CrossRef]

- Barbara Ryden, Introduction to Cosmology, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- D. Baumann. [arXiv:0907.5424 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- M. Kamionkowski and E. D. Kovetz, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 54, 227-269 (2016). [arXiv:1510.06042 [astro-ph.CO]]. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Sanchis-Lozano, Stringy Signals from Large-Angle Correlations in the Cosmic Microwave Background?, Universe 8, no.8, 396 (2022) [arXiv:2205.13257 [astro-ph.CO]]. arXiv:2205.13257 [astro-ph.CO]].

- M. A. Sanchis-Lozano and V. Sanz, Observable imprints of primordial gravitational waves on the temperature anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background, Phys. Rev. D 109, no.6, 063529 (2024) [arXiv:2312.02740 [astro-ph.CO]]. [CrossRef]

- Branderberger, R.H., 1994, IJMP-A, 9, 2117.

- E. Allys et al. [LiteBIRD], PTEP 2023, no.4, 042F01 (2023). [arXiv:2202.02773 [astro-ph.IM]]. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, R. K., Wolfe, A. M., 1967, ApJ, 147, 73.

- Melia F. Angular Correlation of the CMB in the Rh=ct Universe, A&A2012561 A80.

- Melia, F.; López-Corredoira, M. Evidence of a truncated spectrum in the angular correlation function of the cosmic microwave background. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 610, A87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Melia, Q. Ma, J. J. Wei and B. Yu, Astron. Astrophys. 655, A70 (2021). arXiv:2109.05480 [astro-ph.CO]].

- Sanchis-Lozano, M.A.; Melia, F.; Lopez-Corredoira, M.; Sanchis-Gual, N. Missing large-angle correlations versus odd-parity dominance in the cosmic microwave background. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Land, K.; Magueijo, J. Is the Universe odd? Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copi, C.J.; Huterer, D.; Schwarz, D.J.; Starkman, G.D. Large angle anomalies in the CMB. Adv. Astron. 2010, 2010, 847541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Santos, L. Preferred axis in cosmology. Universe 2015, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Naselsky, P. Asymmetry of the CMB map: Local and global anomalies. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 2021, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhanov, V. F. Physical Foundations of Cosmology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- C. Csaki, [arXiv:hep-ph/0404096 [hep-ph]].

- G. von Gersdorff, L. Pilo, M. Quiros, A. Riotto and V. Sanz, Phys. Lett. B 598, 106-112 (2004). [arXiv:hep-th/0404091 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- Hebecker, Arthur and March-Russell, John, The structure of GUT breaking by orbifolding, Nucl. Phys. B, 625, 128-150 2002 [arXiv: hep-ph/0107039].

- Aluri, P.K.; Jain, P. Parity Asymmetry in the CMBR Temperature Power Spectrum. MNRAS 2012, 419, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Aluri, P.K.; Samal, P.K.; Rath, P.K. Parity in Planck full-mission CMB temperature maps. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 125, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Randall and R. Sundrum, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3370-3373 (1999) [arXiv:hep-ph/9905221 [hep-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- L. Randall and R. Sundrum, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4690-4693 (1999) [arXiv:hep-th/9906064 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Maldacena. The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 231-252 1998.

- J. Hirn and V. Sanz. Interpolating between low and high energy QCD via a 5-D Yang-Mills model. JHEP 12, 030 2005.

- A. Donini, V. Enguita-Vileta, F. Esser and V. Sanz, “Generalising Holographic Superconductors,” Adv. High Energy Phys. 2022 (2022), 1785050 [arXiv:2107.11282 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- J. Hirn and V. Sanz. A Negative S parameter from holographic technicolor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 121803 2006.

- J. Hirn and V. Sanz. The Fifth dimension as an analogue computer for strong interactions at the LHC/. JHEP 03, 100 2007.

- T. Sakai and S. Sugimoto, “Low energy hadron physics in holographic QCD,” Prog. Theor. Phys. 113 (2005), 843-882 [arXiv:hep-th/0412141 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- J. Hirn, N. Rius and V. Sanz, “Geometric approach to condensates in holographic QCD,” Phys. Rev. D 73 (2006), 085005 [arXiv:hep-ph/0512240 [hep-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- J. Hirn and V. Sanz. (Not) Summing over Kaluza-Kleins. Phys. Rev. D 76, 044022 2007.

- K.L. McDonald, Little Randall-Sundrum model and a multiply warped spacetime, Phys. Rev. D 77 (2008), 124046.

- A. D. Medina and E. Ponton, JHEP 06, 009 (2011) [arXiv:1012.5298 [hep-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- R. Fok, C. Guimaraes, R. Lewis and V. Sanz. It is a Graviton! or maybe not. JHEP 12, 062 2012.

- B.M. Dillon and V. Sanz. Kaluza-Klein gravitons at LHC2. Phys. Rev. D 96 no.3, 035008 2017.

- J. Liu and F. Melia, Phys. Lett. B 853, 138645 (2024) [arXiv:2404.08170 [astro-ph.CO]]. [CrossRef]

- Work in progress.

- A. Lue, L. M. Wang and M. Kamionkowski, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1506-1509 (1999) [arXiv:astro-ph/9812088 [astro-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- B. Feng, H. Li, M. z. Li and X. m. Zhang, Phys. Lett. B 620, 27-32 (2005) [arXiv:hep-ph/0406269 [hep-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- G. C. Liu, S. Lee and K. W. Ng, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 161303 (2006) [arXiv:astro-ph/0606248 [astro-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- S. Saito, K. Ichiki and A. Taruya, JCAP 09, 002 (2007) [arXiv:0705.3701 [astro-ph]]. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Contaldi, J. Magueijo and L. Smolin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 141101 (2008) [arXiv:0806.3082 [astro-ph]]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).