1. Introduction

The escalating complexity of global environmental issues, intrinsically linked to societal consumption patterns, has established sustainable development as a critical international priority (Jaca et al., 2018). The concept of sustainable development, which advocates for a balance between environmental integrity, social equity, and economic viability (Dempsey et al., 2011; Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002), has profoundly reshaped policy and business strategy. This urgency is particularly acute in developing nations like Pakistan, which are grappling with severe environmental degradation, including hazardous air quality, persistent smog, and widespread pollution that pose significant threats to public health and economic stability (Hussain et al., 2025; Nasir et al., 2025). Within this paradigm, consumers have been recognized as pivotal agents of change, capable of driving markets toward sustainability through their purchasing decisions (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Tan et al., 2016). This shift is propelled by a rising Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC), which signifies a heightened awareness of the broader consequences of consumption (De Carvalho et al., 2015). Consequently, a growing segment of consumers expresses a willingness to purchase environmentally friendly products, even at a premium (Confente et al., 2020; Lucas et al., 2018), thereby creating a compelling business case for corporate sustainability (Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002).

Despite this growing pro-environmental sentiment, a significant and well-documented gap persists between consumers’ stated attitudes and their actual purchasing behaviors (Nguyen et al., 2019a; Weigel & Weigel, 1978). This “attitude-behavior gap” remains a central challenge in the field, limiting the market success of green products and impeding the transition toward a truly sustainable economy (J. Wang et al., 2021). An extensive body of literature has explored this discrepancy, identifying various antecedents of green consumption, including environmental knowledge, specific attitudes, and socio-demographic factors (Sun et al., 2019; Van Liere & Dunlap, 1981). Furthermore, numerous studies have highlighted the powerful role of external factors, particularly the influence of social norms and peer groups on consumption choices (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Ling et al., 2024; Salazar et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2023). However, the internal psychological mechanisms that translate a general sense of sustainability consciousness into a firm intention to act remain insufficiently understood. Specifically, while the drivers of consciousness are being identified, the process by which this awareness is internalized into an individual’s self-concept has not been adequately examined as a key mediator. This study identifies a critical research gap: the need for an integrated model that explains how specific dimensions of consciousness shape a green self-identity, and how this identity, in turn, drives consumption intention under varying levels of social influence. Therefore, this paper seeks to answer the following research question: How do specific dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness influence Green Consumption Intention, and what is the mediating role of Green Self-Identity and the moderating role of Social Influence in this relationship?

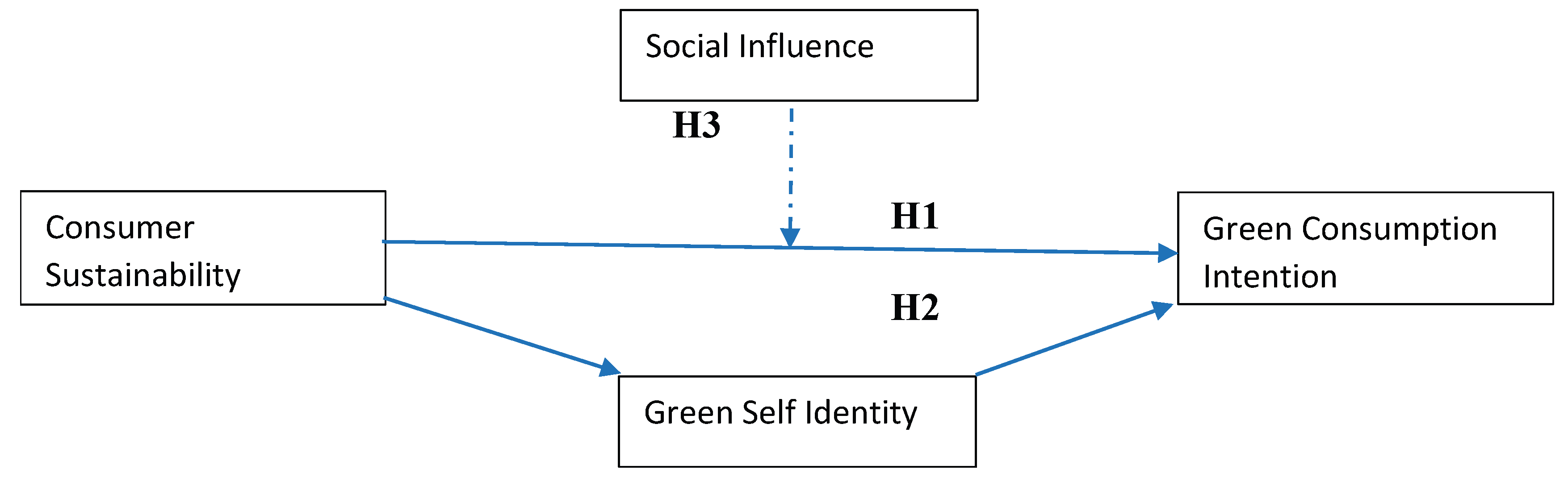

To address this question, this research investigates a moderated mediation model built upon several key constructs. The independent variables are three core dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness, a framework designed to identify the triggers of sustainable behavior (De Carvalho et al., 2015). These dimensions are: (1) Sense of Retribution, which captures the positive emotional and moral rewards individuals derive from making sustainable choices; (2) Access to Information, which pertains to the role of media and other informational sources in elevating awareness of environmental issues; and (3) Labelling and Peer Pressure, which reflects the combined influence of formal market cues (e.g., eco-labels) and informal social signals from an individual’s peer group (De Carvalho et al., 2015; Jaca et al., 2018). The proposed mediating variable is Green Self-Identity (GSI), defined as the degree to which an individual views being an environmentally responsible person as a central and important aspect of their self-concept (Barbarossa et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2020). The dependent variable is Green Consumption Intention, a measure of an individual’s readiness and motivation to purchase green products (Zhu et al., 2013).

The theoretical foundation for this research synthesizes concepts from social psychology to construct a comprehensive model of green consumption. The overarching construct of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (De Carvalho et al., 2015) provides the framework for the model’s antecedents. To explain the psychological pathway that connects this consciousness to behavioral intention, the model incorporates principles from Identity Theory. This theory posits that individuals possess multiple identities tied to their various social roles and group memberships, and they are motivated to behave in ways that are consistent with the meanings associated with these identities (Stets & Burke, 2000) Accordingly, a consumer who has developed a strong green self-identity will be more likely to form consumption intentions that verify and affirm this salient aspect of their self-concept (Neves & Oliveira, 2021). Furthermore, the model draws on Social Influence Theory to explain the contingent role of the social environment. This theory suggests that social norms and perceived pressures can either amplify or attenuate the relationship between an individual’s internal dispositions and their subsequent behavioral intentions (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Salazar et al., 2013). In this model, high social influence is hypothesized to strengthen the link between a consumer’s green self-identity and their intention to purchase green products.

This study makes several important contributions to the sustainable consumption literature. Theoretically, it proposes and tests a novel moderated mediation model that clarifies the psychological pathway from awareness to intention. By positioning green self-identity as a key mediator, this research offers a mechanism-based explanation for how external triggers are internalized into a self-concept that subsequently drives pro-environmental intent (Barbarossa et al., 2017; Silintowe & Sukresna, 2022). Empirically, the study provides a more integrated analysis than previous work by simultaneously examining the interplay of cognitive triggers (information, labels), self-concept (identity), and the social context (social influence). From a practical standpoint, the findings offer valuable guidance for companies, marketers, and consumer organizations. The model suggests that effective strategies must move beyond simply providing information and should instead focus on interventions that help consumers build and reinforce a green self-identity (Jaca et al., 2018). Leveraging social influence by highlighting pro-environmental community norms, including through social media influencers (Rajput et al., 2024) can further strengthen the connection between this identity and actual consumption behavior, thereby helping to close the persistent green gap (J. Wang et al., 2021).

2. Literature Review

The scholarly discourse on green consumption is extensive, yet it is characterized by a persistent puzzle: the gap between consumers’ pro-environmental attitudes and their corresponding behaviors. To unravel this complexity, this study synthesizes multiple theoretical streams, primarily drawing upon the tenets of Identity Theory and Social Influence Theory to build a comprehensive model. This section will first elucidate the core theoretical frameworks that underpin the research model. Following this, it will define the key constructs - Consumer Sustainability Consciousness, Green Self-Identity, Social Influence, and Green Consumption Intention - grounding them in the extant literature. Finally, it will logically develop the study’s hypotheses, articulating the expected relationships between these variables and providing a robust theoretical rationale for the proposed moderated mediation model.

The theoretical bedrock of this research is Identity Theory, which posits that the self is a multi-faceted structure composed of various identities, each tied to an individual’s roles and group memberships (Stets & Burke, 2000). A central premise of this theory is the principle of self-verification, which suggests that individuals are fundamentally motivated to act in ways that are congruent with the meanings and expectations associated with their most salient identities. When a particular identity is activated, it creates a perpetual control system where individuals compare their self-perceptions to the standards of that identity and adjust their behavior to minimize any discrepancy. In the context of sustainable consumption, this framework is exceptionally potent. When being an environmentally conscious person becomes a core component of an individual’s self-concept, a green self-identity is formed (Sharma et al., 2020). This identity is not merely a passive label but an active motivational force that compels individuals to align their intentions and behaviors with the values of environmentalism (Van der Werff et al., 2013). This perspective moves beyond purely cognitive models like the Theory of Planned Behavior by suggesting that green consumption is not just a calculated decision but an affirmation of “who I am” (Sparks & Shepherd, 1992). This study leverages Identity Theory to propose that green self-identity is the crucial psychological mechanism through which broader sustainability awareness is translated into a specific intention to act.

Complementing this internal, identity-based perspective is Social Influence Theory, which emphasizes the powerful role of the social environment in shaping individual behavior. Social influence operates through various mechanisms, including normative pressures (the desire to conform to the expectations of significant others) and informational influences (the tendency to accept information from others as evidence about reality) (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016). In the domain of green consumption, the influence of peers, family, and the wider community can be a formidable force, either facilitating or inhibiting pro-environmental choices (Salazar et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2023). A supportive social context that values and normalizes green behaviors can validate an individual’s green self-identity and provide the encouragement needed to overcome barriers to sustainable consumption (Lucas et al., 2018). Conversely, a social environment that is indifferent or hostile to environmentalism can create significant friction, making it more difficult for an individual to act on their pro-environmental intentions, even if they possess a strong green identity (Nguyen et al., 2019). This study incorporates Social Influence Theory to conceptualize the social context not merely as a direct predictor of behavior but as a critical moderator that can amplify or attenuate the psychological processes linking consciousness, identity, and intention.

The antecedent in our model is Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC), a multidimensional construct that captures the various triggers motivating a shift toward more responsible consumption (De Carvalho et al., 2015). This framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of consumer motivations than a singular “green awareness” metric. This study focuses on three key dimensions of CSC as identified by De Carvalho et al. (2015) and subsequently applied in the literature (Jaca et al., 2018). The first dimension, Sense of Retribution, relates to the intrinsic rewards and positive feelings consumers experience when they engage in sustainable behavior. It is closely linked to personal values and a sense of responsibility for one’s impact on social and environmental challenges, manifesting as moral emotions like anticipated pride (De Carvalho et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2015). The second dimension, Access to Information, recognizes the crucial role of information in shaping consumer awareness and behavior. The proliferation of information through various media has made consumers more conscious of environmental problems, providing the cognitive foundation necessary to understand the consequences of their choices and learn about sustainable alternatives (Jaca et al., 2018). The third dimension, Labelling and Peer Pressure, captures the dual influence of formal market signals and informal social cues. Eco-labels serve as a source of credible information that can simplify decision-making (Chi, 2021), while peer pressure reflects the significant impact of one’s social circle on consumption choices (Jaca et al., 2018).

The central mediating variable in our proposed framework is Green Self-Identity (GSI). GSI refers to the degree to which an individual integrates pro-environmental beliefs and values into their core self-concept, thereby seeing themselves as an environmentally conscious person (Barbarossa et al., 2017; Confente et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). When being “green” becomes a salient part of an individual’s identity, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that reinforce and express that identity (Costa Pinto et al., 2016; Whitmarsh & O’Neill, 2010). GSI thus functions as a powerful internal driver, transforming general environmental concerns into a personalized moral imperative to act (B. Wu & Yang, 2018). In this capacity, it can serve as a crucial psychological bridge, or mediator, between the external triggers of sustainability consciousness and the formation of a firm intention to consume sustainably (Silintowe & Sukresna, 2022). The moderating variable in our model is Social Influence (SI), which encompasses the various ways in which individuals are affected by their social environment, including the perceived expectations and behaviors of their family, friends, and community (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Salazar et al., 2013; S. T. Wang, 2014). Finally, the dependent variable is Green Consumption Intention (GCI), a measure of an individual’s readiness and motivation to engage in green purchasing behavior (Neves & Oliveira, 2021; Zhu et al., 2013). Although intention does not always translate perfectly into behavior - the well-known “intention-behavior gap” (Nguyen et al., 2019) - it remains the most immediate and significant predictor of action, making it a critical focal point for research.

Building on these theoretical foundations, we develop our hypotheses. The dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness are proposed as direct antecedents of Green Consumption Intention. A strong Sense of Retribution - the positive feeling of doing good - can directly motivate individuals to intend to engage in further pro-environmental behaviors (Jaca et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2015). Similarly, having Access to Information about environmental problems and solutions can raise awareness and directly foster an intention to act (De Carvalho et al., 2015). Finally, Labelling and Peer Pressure provide both informational cues and normative pressures that can directly shape a consumer’s intention to choose green products (Chi, 2021; Jaca et al., 2018). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1a: Sense of Retribution has a positive and significant influence on Green Consumption Intention.

H1b: Access to Information has a positive and significant influence on Green Consumption Intention.

H1c: Labelling and Peer Pressure have a positive and significant influence on Green Consumption Intention.

We further posit that Green Self-Identity acts as a crucial mediator in these relationships. The external triggers of CSC contribute to the formation of a green identity, which then becomes a more powerful and proximate driver of consumption intentions (Confente et al., 2020; Silintowe & Sukresna, 2022). This suggests that the influence of CSC on GCI is not just direct, but is also channeled through the self-concept. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H2: Green Self-Identity mediates the relationship between the dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (Sense of Retribution, Access to Information, and Labelling & Peer Pressure) and Green Consumption Intention.

Finally, we propose that the strength of these relationships is contingent on the social environment. When a consumer perceives high Social Influence in favor of green consumption, the impact of their sustainability consciousness on their consumption intention is likely to be amplified (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Salazar et al., 2013). Social validation and normative cues can make the adoption of green intentions more attractive and socially rewarding (Islam et al., 2024; Le, 2024; Lucas et al., 2018). Conversely, in a social context that is indifferent or hostile to environmentalism, the link between consciousness and intention may be weakened. Thus, we propose:

H3: Social Influence positively moderates the relationship between the dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (Sense of Retribution, Access to Information, and Labelling & Peer Pressure) and Green Consumption Intention, such that the relationships are stronger when social influence is high.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the comprehensive research methodology employed to empirically test the proposed conceptual model and address the research questions. It provides a detailed account of the research design, data collection procedures, sample characteristics, the development and validation of measurement instruments, control variables, and the analytical strategy used to examine the data and test the hypotheses. Also, ethical approval was secured from the Research Excellence Committee of our institution. All participants, aged 18 and above, provided informed verbal consent. Their anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained, and data collection was conducted ethically, free from any harm, coercion, or undue influence.

3.1. Data and Sample

This study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to investigate the relationships between consumer sustainability consciousness, green self-identity, social influence, and green consumption intention. The data collection was meticulously planned and executed in two waves to mitigate the potential for common method bias, a common concern in survey-based research where all data are collected from the same source at the same time (Podsakoff et al., 2003, as cited in Liang et al. (2022). This temporal separation of measurements helps to reduce the likelihood of spurious correlations arising from transient mood states or consistency motifs on the part of the respondents.

The target population for this study was specifically defined as consumers of products from key manufacturing sectors in Pakistan. The selection of these sectors was informed by the Pakistan Economic Survey 2024-25, which identifies several industries as major contributors to the national economy and, concurrently, as significant sources of environmental pollution. Given the pressing issues of a rising Air Quality Index (AQI), persistent smog, and general pollution in the country’s urban centers (Hussain et al., 2025; Nasir et al., 2025), focusing on consumers of these sectors provides a particularly relevant context for studying green consumption intentions. The selected sectors include: (1) Textile and Apparel, (2) Food, Beverages, and Tobacco, (3) Pharmaceuticals and Chemicals, (4) Coke and Petroleum Products, (5) Non-metallic Mineral Products (e.g., cement, glass), and (6) Electrical Appliances and Electronics. The rationale for this purposive targeting is that consumers who frequently use products from these industries are more likely to have a salient and developed consciousness regarding the environmental impact of their consumption patterns, making them a suitable population for testing the study’s hypotheses.

A non-probabilistic convenience sampling technique was employed for data collection. Respondents were approached in public places such as shopping malls and university campuses, as well as through online social media platforms. The selection criteria were that respondents must be consumers of products from at least one of the six specified sectors. In the first wave, a structured questionnaire was administered to collect data on the independent variables (the three dimensions of CSC) and the dependent variable (Green Consumption Intention). A few weeks later, in the second wave, the same respondents were contacted again to collect data on the mediating variable (Green Self-Identity) and the moderating variable (Social Influence). After a rigorous data screening process, which involved removing incomplete questionnaires and identifying outliers, a final sample of 1,092 valid responses was retained for analysis. The sample comprised a diverse mix of demographic profiles, including a balanced distribution of gender and a wide range of age groups, educational qualifications, and income levels, providing a robust foundation for testing the proposed theoretical model.

3.2. Measures

All constructs in the research model were measured using multi-item scales adapted from established and validated literature to ensure content validity. A five-point Likert scale, with anchors ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”), was utilized for all measurement items. The questionnaire was initially developed in English and then translated into the local language to ensure clarity and comprehension for all participants, following a standard back-translation procedure.

Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC): This was conceptualized as a second-order construct comprising three first-order dimensions, with measurement items adapted from (De Carvalho et al., 2015). Sense of Retribution (SR) dimension was measured with six items designed to assess the positive emotional and moral rewards associated with sustainable consumption (e.g., “ I started making an effort to buy products in recyclable packaging.”). The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α=0.891). Access to Information (AI) was measured using four items that evaluate the role of various information sources in raising sustainability awareness (e.g., “I saw a documentary or shocking information that led me to be more careful about what I buy”). The scale showed high reliability (α=0.843). Labelling and Peer Pressure (LPP) dimension was assessed with four items capturing the influence of product labels and peer recommendations on consumer choices (e.g., “I began to be interested in information on product labels (eco-labels)”). The scale had good internal consistency (α=0.827).

Green Self-Identity (GSI), the mediating variable, was measured using a three-item scale adapted from (Khare & Pandey, 2017). These items capture the extent to which an individual perceives being an environmentally friendly person as integral to their self-concept (e.g., “ I am very very certain about being an environmentally responsible person.”). The reliability of this scale was acceptable (α=0.822).

Social Influence (SI), the moderating variable, was assessed with a four-item scale adapted from (Salazar et al., 2013) and (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016). The items measure the perceived social pressure from significant others to engage in green consumption (e.g., “ All of the people important to me advise me to use green products.”). This scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α=0.850).

Green Consumption Intention (GCI), the dependent variable, was measured using a three-item scale adapted from (Zhu et al., 2013) to gauge the likelihood of a consumer intending to purchase green products in the future (e.g., “ Soon, I am willing to buy green products for myself and my family.”). The scale showed good reliability (α=0.757).

3.3. Control Variables

In consumer behavior research, demographic factors can often influence attitudes and intentions. To account for potential confounding effects and to ensure that the relationships observed in the model are not spurious, several key demographic variables were included as control variables in the analysis. These included Generation (Millennials/Gen Z) and Income. While these variables were not central to the hypothesized theoretical framework, controlling for their effects helps to isolate the relationships between the primary constructs of interest (Sun et al., 2019). The inclusion of these controls is consistent with prior research in green consumption, which has often found significant, albeit sometimes inconsistent, effects of demographic characteristics on pro-environmental behavior (Lin & Niu, 2018; Van Liere & Dunlap, 1981). These variables were incorporated into the PLS-SEM model as direct predictors of the dependent variable, Green Consumption Intention, allowing their variance to be partialled out before assessing the significance of the hypothesized paths.

3.4. Analytical Strategy

The collected data were analyzed using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique, with the aid of SmartPLS 3 software. PLS-SEM was chosen as the primary analytical method for several reasons. First, it is particularly well-suited for testing complex predictive models that include multiple mediating and moderating relationships, as is the case in this study (Ali et al., 2023). Second, PLS-SEM is a variance-based approach that is robust to issues of data non-normality, a common feature of survey data collected on Likert scales (Hair et al., 2013, as cited in Shanmugam et al., 2022). Third, the primary objective of this research is to explain the variance in the dependent variable (GCI), which aligns with the predictive focus of PLS-SEM.

Following the well-established two-stage analytical approach recommended by (Hair et al., 2013, as cited in (Shanmugam et al., 2022), this study employed a systematic procedure for data analysis to ensure methodological rigor and empirical robustness. In the first stage, the measurement model was meticulously assessed to verify the reliability and validity of the constructs. This involved evaluating indicator reliability through outer loadings, ensuring that all measurement items exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70. Internal consistency reliability was further examined using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability, with values of 0.70 or higher considered satisfactory. Convergent validity was confirmed by verifying that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct surpassed the minimum benchmark of 0.50, while discriminant validity was established through the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, maintaining values below the conservative cut-off of 0.85 to confirm empirical distinctiveness among constructs.

Upon establishing the soundness of the measurement model, the second stage focused on the structural model assessment to test the hypothesized relationships among constructs. This included the analysis of path coefficients, where the significance and strength of direct, mediating, and moderating relationships were evaluated through a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples, interpreting each path based on its t-statistic and p-value. The model’s explanatory power was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R²). Furthermore, the predictive relevance of the model was determined using the Stone-Geisser Q² statistic, with values greater than zero indicating adequate predictive accuracy. Collectively, this two-stage analytical process ensured a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of both the measurement and structural components, thereby reinforcing the validity, reliability, and overall credibility of the research findings.

4. Results

This section articulates the empirical results obtained through the application of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), adhering to the established two-stage analytical procedure. The first stage entails a meticulous evaluation of the measurement model to ensure the reliability, validity, and overall robustness of the constructs. Subsequently, the second stage focuses on the assessment of the structural model, wherein the hypothesized relationships, along with the mediation and moderation effects, are rigorously tested to validate the proposed conceptual framework

4.1. Sample Demographics and Green Consumption Inclination

The dataset reveals a significant concentration of younger respondents, with Millennials (78.6%) forming the largest group, followed by Generation Z (21.2%). Together, these two generational cohorts constitute 99.8% of the sample, aligning with the study’s emphasis on understanding green consumption behaviors in younger, environmentally conscious consumers. The male respondents comprise 74.2% of the sample, while females account for 25.6%, with a slightly lower mean Green Consumption Intention (GCI) score of 4.13 compared to males (4.16). Income distribution reveals a diverse set of respondents across varying economic strata. The largest group is represented by those earning between Rs. 100,001–Rs. 200,000 (32.2%), followed by those in the Rs. 50,001–Rs. 100,000 range (18.3%). A notable trend emerges wherein higher-income groups, particularly those in the Rs. 200,001–Rs. 300,000 and Rs. 300,000 or more brackets exhibit higher mean GCI scores (4.21 and 4.22, respectively). Conversely, lower-income respondents (earning less than Rs. 50,000) report a comparatively lower GCI score (4.02). These findings suggest a positive relationship between income levels and the intention to engage in green consumption, highlighting that respondents with greater economic means demonstrate a stronger inclination toward purchasing environmentally sustainable products. Overall, the data underpins the premise that younger age and higher income are critical determinants in shaping individuals’ propensity for green consumption behaviors.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Mean Green Consumption Intention (GCI).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Mean Green Consumption Intention (GCI).

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

Mean GCI (M ± SD) |

| Generation |

Millennials (1981–1996) |

859 |

78.6 |

4.16 ± 0.73 |

| |

Generation Z (1997–2012) |

231 |

21.2 |

4.13 ± 0.73 |

| |

Other |

2 |

0.2 |

4.07 ± 0.70 |

| Gender |

Male |

810 |

74.2 |

4.16 ± 0.73 |

| |

Female |

282 |

25.8 |

4.13 ± 0.73 |

| Monthly Income |

Less than Rs. 50,000 |

280 |

25.6 |

4.02 ± 0.73 |

| |

Rs. 50,001–Rs. 100,000 |

200 |

18.3 |

4.17 ± 0.72 |

| |

Rs. 100,001–Rs. 200,000 |

352 |

32.2 |

4.14 ± 0.71 |

| |

Rs. 200,001–Rs. 300,000 |

243 |

22.3 |

4.21 ± 0.74 |

| |

Rs. 300,000 or more |

17 |

1.6 |

4.22 ± 0.72 |

| Total |

— |

1092 |

100.0 |

4.15 ± 0.73 |

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model was meticulously evaluated to ensure the reliability and validity of the latent constructs.

Table 2 summarizes the results of internal consistency and convergent validity assessments. All indicator loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 (ranging from 0.784 to 0.880), affirming strong item reliability. Measures of internal consistency, including Cronbach’s alpha (minimum 0.757) and Composite Reliability (CR) (minimum 0.861), surpassed the 0.70 criterion, demonstrating robust construct reliability. Moreover, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.648 to 0.738, all above the 0.50 benchmark, thereby confirming satisfactory convergent validity and the adequacy of each construct in explaining the variance of its indicators.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics, affirming that all variables display distributional properties consistent with normality, as reflected by acceptable skewness and kurtosis values, an expected outcome for large-sample survey data. The constructs exhibit mean scores exceeding 4.083 on a five-point Likert scale, suggesting a generally high level of respondent agreement with the measurement statements. Furthermore, the correlation matrix reveals that all constructs are positively and significantly interrelated, underscoring the coherence and theoretical alignment among the study’s key variables.

4.4. Discriminant Validity (Fornell-Larcker Criterion)

Table 4 reports the assessment of discriminant validity based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion. For each latent construct, the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), represented by the diagonal elements, exceeds its corresponding inter-construct correlation coefficients across both rows and columns. This result substantiates that all constructs are empirically distinct, thereby affirming their ability to capture unique and non-overlapping theoretical dimensions within the measurement model.

4.5. Structural Model Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

The structural model was examined to evaluate the hypothesized relationships proposed within the conceptual framework. The model demonstrates substantial explanatory power for the dependent variable, Green Consumption Intention (GCI), with an R² value of 0.277, indicating that the predictor constructs collectively account for 27.7% of the variance in GCI. Similarly, the mediator, Green Self-Identity (GSI), exhibits an R² value of 0.323, underscoring its central role in the model. The predictive relevance (Q²) for GCI stands at 0.347, confirming strong out-of-sample predictive capability, while the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values (≤ 2.315) fall well within acceptable limits, indicating the absence of multicollinearity concerns.

The results of the direct effects, including the influence of control variables, are summarized in

Table 5. The findings provide robust empirical support for Hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c (CSC → GCI), as all three dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness exert a positive and highly significant impact on GCI. Specifically, H1a (β = 0.207, t = 6.456, p < 0.001), H1b (β = 0.119, t = 4.704, p < 0.001), and H1c (β = 0.104, t = 3.655, p < 0.001) are supported, with Sense of Retribution emerging as the most influential predictor (β = 0.207). Furthermore, Green Self-Identity (GSI → GCI) is identified as the strongest direct determinant of GCI (β = 0.268, t = 8.868, p < 0.001), reaffirming its pivotal mediating role within the structural model.

Regarding the control variables, Income exerts a negative and significant effect (β = −0.063, t = 2.450, p = 0.014), suggesting that, when other variables are held constant, individuals in higher income brackets exhibit a slightly lower predicted level of green consumption intention (as per the coding scheme). In contrast, the Millennials/Gen Z variable shows a non-significant influence (β = 0.047, t = 1.708, p = 0.088), implying no statistically meaningful difference in GCI based on generational cohort within the sample.

4.6. Mediation Analysis (H2)

Hypothesis H2 posited that Green Self-Identity (GSI) mediates the relationship between the dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC) and Green Consumption Intention (GCI). The bootstrapping results, presented in

Table 6, confirmed the statistical significance of all specific indirect effects, thereby validating the presence of mediation. The indirect effect of Sense of Retribution on GCI through GSI was 0.092 (t = 6.945, p < 0.001), Access to Information exerted an indirect effect of 0.061 (t = 6.471, p < 0.001), and Labelling and Peer Pressure demonstrated an indirect effect of 0.047 (t = 5.250, p < 0.001). As the direct effects of these dimensions on GCI also remained significant, the results indicate partial mediation across all three pathways. Hence, Hypothesis H2 is fully supported, underscoring the mediating role of GSI in strengthening the link between sustainability consciousness and green consumption intention.

4.7. Moderation Analysis (H3)

Hypothesis H3 proposed that Social Influence (SI) exerts a positive moderating effect on the direct relationships between the dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC) and Green Consumption Intention (GCI). This proposition was empirically examined through the significance testing of the respective interaction terms within the structural model.

Table 7.

Moderation Analysis.

Table 7.

Moderation Analysis.

| Structural Path |

β |

t |

p-value |

Remarks |

| SR×SI→GCI |

7.051 |

9.417 |

0.000 |

H3 Supported |

| AI×SI→GCI |

6.756 |

7.069 |

0.000 |

H3 Supported |

| LPP×SI→GCI |

6.505 |

9.589 |

0.000 |

H3 Supported |

The findings reveal nuanced insights into the moderating role of Social Influence (SI) within the proposed framework. The interaction between Sense of Retribution and Social Influence is positive and statistically significant (β = 7.051, t = 9.417, p = 0.000), indicating that stronger social influence enhances the impact of intrinsic, emotionally driven motivations on Green Consumption Intention (GCI). Similarly, the interaction between Access to Information and Social Influence is also positive and significant (β = 6.756, t = 7.069, p = 0.000), suggesting that heightened social influence amplifies the translation of cognitive environmental awareness into actual consumption intentions. Likewise, the moderating effect of Social Influence on the relationship between Labelling & Peer Pressure and GCI is significant (β = 6.505, t = 9.589, p = 0.000). This finding implies that as labelling and peer pressure (LPP) are combined with a sense of information (SI), individuals are more inclined to adopt green consumption behaviors. Taken together, these results substantiate the integrity of the moderated mediation model, underscoring Green Self-Identity as a key transformative conduit between sustainability consciousness and green consumption. Moreover, they highlight Social Influence as a potent contextual amplifier that reinforces the emotional and informational underpinnings of sustainable consumer behavior.

5. Discussion

This study was designed to unravel the complex psychological pathway that translates consumer sustainability consciousness into a firm intention to engage in green consumption within the urgent environmental context of Pakistan. By proposing and testing a moderated mediation model, we sought to understand how the dimensions of Consumer Sustainability Consciousness (CSC) foster Green Consumption Intention (GCI), through the pivotal mediating role of Green Self-Identity (GSI) and under the conditional effect of Social Influence (SI). The empirical analysis yielded robust support for the proposed conceptual framework, which demonstrated substantial explanatory power, accounting for 27.7% of the variance (R2=0.277) in Green Consumption Intention. The findings confirm that the journey from environmental consciousness to consumption intention is a deeply personal and socially embedded process. Specifically, all three dimensions of CSC, Sense of Retribution, Access to Information, and Labelling & Peer Pressure emerged as significant direct antecedents of GCI. More critically, Green Self-Identity was validated as a powerful partial mediator, functioning as the strongest single predictor of pro-environmental intent. Finally, the moderating effect of Social Influence was partially confirmed, revealing that it acts as a potent amplifier for the emotional and informational drivers of sustainability consciousness. These results offer a more nuanced understanding of the architecture of pro-environmental intent, providing a mechanism-based explanation that moves beyond traditional linear models of awareness and behavior.

The confirmation of direct, positive relationships between the dimensions of CSC and GCI (H1a, H1b, H1c) provides a strong foundation for our model. This aligns with a vast body of literature demonstrating that environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, and peer influence are significant antecedents of green consumption intention (Lin & Niu, 2018; Mohd Suki & Mohd Suki, 2019; S. T. Wang, 2014). The finding that Sense of Retribution, reflecting intrinsic moral and emotional rewards, was the most influential direct predictor (β=0.207) underscores the power of affective motivations. This resonates with research highlighting the role of positive moral emotions, such as anticipated pride, in driving green purchase intention (Xie et al., 2015). The significance of Access to Information reinforces the established link between environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior (Michel et al., 2023), while the effect of Labelling & Peer Pressure is consistent with studies confirming the positive impact of eco-labels and peer influence on green purchasing (Chi, 2021; Lee, 2010).

However, the centerpiece of our research, and its most compelling finding, is the powerful mediating role of Green Self-Identity (H2). GSI was not only the single strongest predictor of GCI in the model (β=0.268) but was also confirmed as a significant partial mediator for all three CSC pathways. This result is strongly corroborated by a burgeoning stream of literature that has consistently identified GSI as a pivotal psychological mechanism in green consumption (Barbarossa et al., 2017; Confente et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Silintowe & Sukresna, 2022). Scholars have repeatedly demonstrated GSI’s mediating role between various antecedents such as biospheric values (Van der Werff et al., 2013), consumption values (Bhutto et al., 2022; Qasim et al., 2019), and environmental knowledge (Silintowe & Sukresna, 2022) and pro-environmental intentions and behaviors. Our finding of partial mediation is particularly insightful. It suggests that while external triggers like information and social cues have a direct, albeit weaker, influence on intention, their primary and most powerful effect is indirect: they help to shape and cultivate a consumer’s green self-concept, which then becomes the primary engine driving behavioral commitment. This empirically demonstrates that for sustainability consciousness to be truly effective, it must be internalized by the consumer, transforming from a set of external triggers into a core part of their self-concept (Sharma et al., 2020).

Perhaps the most nuanced finding relates to the moderating role of Social Influence (H3), which was fully supported. The analysis revealed that SI significantly amplifies the positive effects of both Sense of Retribution (p=0.000) and Access to Information (p=0.000) on GCI. The significant and powerful role of social influence is a robust and recurring finding in the green consumption literature (Hu & Meng, 2023; Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Salazar et al., 2013). It operates through both informational influence (accepting information from others) and normative influence (conforming to the expectations of others), both of which have been shown to be highly significant drivers of sustainable choices (Salazar et al., 2013). Our results provide strong empirical support for the idea that a supportive social context acts as a powerful catalyst, strengthening the translation of internal motivations (both affective and cognitive) into consumption intentions. Similarly, SI moderates the relationship between Labelling & Peer Pressure and GCI (p=0.000). This non-significant result is logical; when labeling and peer pressure team up with a sense of informed awareness, people are far more likely to embrace green consumption habits.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research makes several important contributions to the existing body of literature on sustainable consumption and environmental psychology. First and foremost, it advances a more integrated theoretical model by synthesizing the Consumer Sustainability Consciousness framework (De Carvalho et al., 2015) with Identity Theory (Stets & Burke, 2000) and Social Influence Theory (Johnstone & Hooper, 2016; Salazar et al., 2013). While previous studies have often examined these concepts in isolation, our model demonstrates their synergistic interplay. By positioning GSI as a central mediator, we provide a crucial psychological bridge that helps to resolve the persistent “attitude-behavior gap” (Nguyen et al., 2019). Our findings suggest this gap may exist precisely because many interventions focus on shaping attitudes rather than cultivating identities. When pro-environmentalism becomes part of the self-concept, as suggested by early work on the topic (Sparks & Shepherd, 1992), intentions become more stable and less susceptible to situational barriers. Our model thus offers a mechanism-based explanation for how consciousness is translated into commitment, adding explanatory depth that moves beyond the purely cognitive calculations of the Theory of Planned Behavior (S.-I. Wu & Chen, 2014).

Second, the study provides robust empirical support for the application of Identity Theory in the context of a developing nation facing palpable environmental threats. It validates GSI as a powerful explanatory variable, reinforcing the theory’s central tenet that individuals are motivated to act in ways that are congruent with their most salient identities (Stets & Burke, 2000). The consistent emergence of GSI as a key determinant in recent literature (Confente et al., 2020; Neves & Oliveira, 2021; Sharma et al., 2020) underscores its importance in explaining the motivation to act sustainably. Our study reinforces this growing consensus, showing that consumption is not merely a calculated decision but can be an affirmation of “who I am.”

Third, by confirming the partial moderating role of social influence, this study refines our understanding of how social context interacts with individual psychology. It suggests that identity-based motivations are not formed in a vacuum; they are nourished and amplified by social validation. This contributes a more nuanced perspective to Social Influence Theory, highlighting its role as a facilitator of the self-verification process central to Identity Theory. It also extends the CSC framework by demonstrating that its “triggers” are not only internalized into an identity but that this entire process is sensitive to the surrounding social climate.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer clear, actionable insights for a range of stakeholders aiming to foster sustainable consumption in Pakistan and other developing countries. For marketers and businesses, the message is unequivocal: move beyond feature-based marketing to identity-building. Given that GSI is the strongest predictor of GCI, campaigns should aim to help consumers build and affirm a green self-identity. Messaging could frame the purchase of green products not as a sacrifice, but as an act of self-expression and an affirmation of a desirable personal identity (Tawde & ShabbirHusain, 2024). Furthermore, the moderating effect of social influence highlights the importance of leveraging social norms and communities. Brands can foster a sense of community around their sustainable products through social media campaigns featuring credible “green influencers” (Cui et al., 2024) and user-generated content that normalizes green consumption and creates a sense of collective identity.

For policymakers and consumer organizations, the implications are equally clear. Public awareness campaigns should not just disseminate information but also appeal to citizens’ sense of moral responsibility and pride (Sense of Retribution) while highlighting positive social norms (Jaca et al., 2018). Environmental education programs, particularly for younger generations, should focus on linking environmental stewardship to personal values and identity. Critically, while marketers and NGOs can promote social norms, their effect may be limited without systemic support. As Johnstone & Hooper (2016) argue, greater government involvement is crucial for creating a supportive “choice architecture” through regulations, infrastructure, and subsidies that make green choices easier and more accessible, thereby translating social influence into widespread behavior change. To close the green gap, policymakers must work to reduce the “reasons against” green consumption, such as high prices and lack of availability, while promoting the “reasons for,” such as environmental and health benefits (J. Wang et al., 2021).

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, which in turn suggest promising avenues for future inquiry. First, the cross-sectional research design precludes definitive claims of causality. A longitudinal study would be beneficial to track how consumer consciousness, identity, and intentions evolve over time. Second, the study relies on self-reported measures of intention, which are subject to social desirability bias and do not capture actual behavior. The well-documented intention-behavior gap remains a challenge (ElHaffar et al., 2020), and future research could incorporate experimental designs or use real purchase data to measure actual green consumption behavior.

Furthermore, future studies could explore other critical factors identified in the literature. For instance, Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE) and Green Product Availability (GPA) have been shown to be key moderators of the intention-behavior relationship (Nguyen et al., 2019) and their inclusion could provide a more complete picture. Another critical area for future investigation is the potential for behavioral rebound effects. Research on energy-efficient products has shown that consumers sometimes increase their overall consumption after purchasing a “green” product, feeling licensed to use it more (Mizobuchi & Takeuchi, 2016), which can undermine the net environmental benefits. Finally, our model treats GSI as a single construct, yet research suggests that green identities can be segmented into different types (e.g., eco-social, eco-centric, ego-centric), with varying motivations (Costa Pinto et al., 2016). Exploring these different facets of green identity could enable more targeted and effective interventions to foster a truly sustainable consumer culture.

References

- Ali, M., Ullah, S., Ahmad, M. S., Cheok, M. Y., & Alenezi, H. (2023). Assessing the impact of green consumption behavior and green purchase intention among millennials toward sustainable environment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(9), 23335–23347. [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C., De Pelsmacker, P., & Moons, I. (2017). Personal Values, Green Self-identity and Electric Car Adoption. Ecological Economics, 140, 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, M. Y., Khan, M. A., Ertz, M., & Sun, H. (2022). Investigating the Role of Ethical Self-Identity and Its Effect on Consumption Values and Intentions to Adopt Green Vehicles among Generation Z. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Chi, N. T. K. (2021). Understanding the effects of eco-label, eco-brand, and social media on green consumption intention in ecotourism destinations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 321. [CrossRef]

- Confente, I., Scarpi, D., & Russo, I. (2020). Marketing a new generation of bio-plastics products for a circular economy: The role of green self-identity, self-congruity, and perceived value. Journal of Business Research, 112, 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Costa Pinto, D., Nique, W. M., Maurer Herter, M., & Borges, A. (2016). Green consumers and their identities: how identities change the motivation for green consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(6), 742–753. [CrossRef]

- Cui, T., Tang, S., & Iqbal, Q. (2024). The role of green influencers on users’ green consumption intention: an empirical study from China and Pakistan. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, B. L., Salgueiro, M. D. F., & Rita, P. (2015). Consumer Sustainability Consciousness: A five dimensional construct. Ecological Indicators, 58, 402–410. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M., Wang, P., & Kuah, A. T. H. (2021). Why wouldn’t green appeal drive purchase intention? Moderation effects of consumption values in the UK and China. Journal of Business Research, 122, 713–724. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., & Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19(5), 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141. [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G., Durif, F., & Dubé, L. (2020). Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 275). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. In Long Range Planning (Vol. 46, Issues 1–2, pp. 1–12). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., & Meng, H. (2023). Digital literacy and green consumption behavior: Exploring dual psychological mechanisms. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(2), 272–287. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A., Abbas, M., & Kabir, M. (2025). Smog Pollution in Lahore, Pakistan: A Review of the Causes, Effects, and Mitigation Strategies. [CrossRef]

- Islam, J. U., Thomas, G., & Albishri, N. A. (2024). From status to sustainability: How social influence and sustainability consciousness drive green purchase intentions in luxury restaurants. Acta Psychologica, 251. [CrossRef]

- aca, C., Prieto-Sandoval, V., Psomas, E. L., & Ormazabal, M. (2018). What should consumer organizations do to drive environmental sustainability? Journal of Cleaner Production, 181, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M. L., & Hooper, S. (2016). Social influence and green consumption behaviour: a need for greater government involvement. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(9–10), 827–855. [CrossRef]

- Khare, A., & Pandey, S. (2017). Role of green self-identity and peer influence in fostering trust towards organic food retailers. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 45(9), 969–990. [CrossRef]

- Le, X. C. (2024). Switching to green vehicles for last-mile delivery: why perceived green product knowledge, consumption values and environmental concern matter. International Journal of Logistics Management, 35(6), 2012–2031. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. (2010). The green purchase behavior of hong kong young consumers: The role of peer influence, local environmental involvement, and concrete environmental knowledge. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(1), 21–44. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Li, J., & Lei, Q. (2022). Exploring the Influence of Environmental Values on Green Consumption Behavior of Apparel: A Chain Multiple Mediation Model among Chinese Generation Z. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(19). [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. T., & Niu, H. J. (2018). Green consumption: Environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behavior. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1679–1688. [CrossRef]

- Ling, P. S., Chin, C. H., Yi, J., & Wong, W. P. M. (2024). Green consumption behaviour among Generation Z college students in China: the moderating role of government support. Young Consumers, 25(4), 507–527. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S., Salladarré, F., & Brécard, D. (2018). Green consumption and peer effects: Does it work for seafood products? Food Policy, 76, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Michel, J. F., Mombeuil, C., & Diunugala, H. P. (2023). Antecedents of green consumption intention: a focus on generation Z consumers of a developing country. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(12), 14545–14566. [CrossRef]

- Mizobuchi, K., & Takeuchi, K. (2016). Replacement or additional purchase: The impact of energy-efficient appliances on household electricity saving under public pressures. Energy Policy, 93, 137–148. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N., & Mohd Suki, N. (2019). Examination of peer influence as a moderator and predictor in explaining green purchase behaviour in a developing country. Journal of Cleaner Production, 228, 833–844. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, I., Saeed, A., Abdur, M., Nasir, R., & Naushahi, M. M. (2025). THE IMPACT OF SMOG/AIR QUALITY ON ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES, HEALTH CONDITIONS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY IN PAKISTAN. In CONTEMPORARY JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW (Vol. 03, Issue 01).

- Neves, J., & Oliveira, T. (2021). Understanding energy-efficient heating appliance behavior change: The moderating impact of the green self-identity. Energy, 225. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. V., Nguyen, C. H., & Hoang, T. T. B. (2019a). Green consumption: Closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustainable Development, 27(1), 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. V., Nguyen, C. H., & Hoang, T. T. B. (2019b). Green consumption: Closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustainable Development, 27(1), 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H., Yan, L., Guo, R., Saeed, A., & Ashraf, B. N. (2019). The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioral intention to consume organic food. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7). [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A., Suryavanshi, K., Thapa, S. B., Gahlot, P., & Gandhi, A. (2024). The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Ecoconscious Consumers. 2024 ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems, ICETSIS 2024, 676–681. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, H. A., Oerlemans, L., & Van Stroe-Biezen, S. (2013). Social influence on sustainable consumption: Evidence from a behavioural experiment. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(2), 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, A., Saththsivam, G., Chyi, Y. S., Sin, T. S., & Musa, R. (2022). Factors influence Green Product Consumption Intention in Malaysia: A Structural Approach. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19, 666–675. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N., Saha, R., Sreedharan, V. R., & Paul, J. (2020). Relating the role of green self-concepts and identity on green purchasing behaviour: An empirical analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3203–3219. [CrossRef]

- Silintowe, Y. B. R., & Sukresna, I. M. (2022). Green Self-identity as a Mediating Variable of Green Knowledge and Green Purchase Behavior. Jurnal Organisasi Dan Manajemen, 18(1), 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P., & Shepherd, R. (1992). Self-Identity and the Theory of Planned Behavior: Assessing the Role of Identification with “Green Consumerism”*. In Social Psychology Quarterly (Vol. 55, Issue 4).

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. In Quarterly (Vol. 63, Issue 3).

- Sun, Y., Liu, N., & Zhao, M. (2019). Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 209, 481–493. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L. P., Johnstone, M. L., & Yang, L. (2016). Barriers to green consumption behaviours: The roles of consumers’ green perceptions. Australasian Marketing Journal, 24(4), 288–299. [CrossRef]

- Tawde, S. G., & ShabbirHusain, R. V. (2024). How does green consumers’ self-concept promote willingness to pay more? A sequential mediation effect of green product virtue and green perceived value. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(4), 2110–2129. [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E., Steg, L., & Keizer, K. (2013). The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 34, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Van Liere, K. D., & Dunlap, R. E. (1981). Environmental Concern. Environment and Behavior, 13(6), 651–676. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Shen, M., & Chu, M. (2021). Why is green consumption easier said than done? Exploring the green consumption attitude-intention gap in China with behavioral reasoning theory. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 2. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. T. (2014). Consumer characteristics and social influence factors on green purchasing intentions. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 32(7), 738–753. [CrossRef]

- Weigel, R., & Weigel, J. (1978). Environmental concern: The Development of a Measure. Environment and Behavior, 10(1), 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L., & O’Neill, S. (2010). Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., & Yang, Z. (2018). The impact of moral identity on consumers’ green consumption tendency: The role of perceived responsibility for environmental damage. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 59, 74–84. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I., & Chen, J.-Y. (2014). A Model of Green Consumption Behavior Constructed by the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(5). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., Yang, Z., Li, Z., & Chen, Z. (2023). A review of social roles in green consumer behaviour. In International Journal of Consumer Studies (Vol. 47, Issue 6, pp. 2033–2070). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Grønhaug, K. (2015). The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(3), 333–356. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., Li, Y., Geng, Y., & Qi, Y. (2013). Green food consumption intention, behaviors and influencing factors among Chinese consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 28(1), 279–286. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Measurement Model.

Table 2.

Measurement Model.

| Construct |

Item |

Loading |

Indicator Reliability |

AVE |

Cronbach’s α |

Composite Reliability (CR) |

| SR |

SR1 |

0.778 |

0.605 |

0.648 |

0.891 |

0.917 |

| |

SR2 |

0.835 |

0.697 |

|

|

|

| |

SR3 |

0.810 |

0.656 |

|

|

|

| |

SR4 |

0.808 |

0.653 |

|

|

|

| |

SR5 |

0.801 |

0.642 |

|

|

|

| |

SR6 |

0.795 |

0.632 |

|

|

|

| AI |

AI1 |

0.818 |

0.669 |

0.680 |

0.843 |

0.895 |

| |

AI2 |

0.851 |

0.724 |

|

|

|

| |

AI3 |

0.829 |

0.687 |

|

|

|

| |

AI4 |

0.799 |

0.638 |

|

|

|

| LPP |

LPP1 |

0.794 |

0.630 |

0.658 |

0.827 |

0.885 |

| |

LPP2 |

0.844 |

0.712 |

|

|

|

| |

LPP3 |

0.784 |

0.615 |

|

|

|

| |

LPP4 |

0.822 |

0.676 |

|

|

|

| GSI |

GSI1 |

0.838 |

0.702 |

0.738 |

0.822 |

0.894 |

| |

GSI2 |

0.880 |

0.774 |

|

|

|

| |

GSI3 |

0.858 |

0.736 |

|

|

|

| SI |

SI1 |

0.828 |

0.686 |

0.688 |

0.850 |

0.898 |

| |

SI2 |

0.837 |

0.701 |

|

|

|

| |

SI3 |

0.865 |

0.748 |

|

|

|

| |

SI4 |

0.787 |

0.619 |

|

|

|

| GCI |

GCI1 |

0.797 |

0.635 |

0.674 |

0.757 |

0.861 |

| |

GCI2 |

0.809 |

0.654 |

|

|

|

| |

GCI3 |

0.855 |

0.731 |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix.

| Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

SR |

AI |

LPP |

GSI |

SI |

GCI |

| SR |

4.087 |

0.53 |

−0.21 |

−0.26 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| AI |

4.091 |

0.54 |

−0.23 |

−0.06 |

0.383 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| LPP |

4.093 |

0.53 |

−0.19 |

−0.33 |

0.345 |

0.260 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| GSI |

4.090 |

0.57 |

−0.24 |

−0.28 |

0.491 |

0.403 |

0.350 |

1.000 |

|

|

| SI |

4.087 |

0.54 |

−0.20 |

−0.30 |

0.305 |

0.266 |

0.227 |

0.208 |

1.000 |

|

| GCI |

4.083 |

0.51 |

−0.02 |

−0.10 |

0.417 |

0.323 |

0.298 |

0.451 |

0.138 |

1.000 |

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity (Fornell–Larcker Criterion).

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity (Fornell–Larcker Criterion).

| Construct |

SR |

AI |

LPP |

GSI |

SI |

GCI |

| SR |

0.805 |

|

|

|

|

|

| AI |

0.385 |

0.825 |

|

|

|

|

| LPP |

0.346 |

0.261 |

0.811 |

|

|

|

| GSI |

0.417 |

0.405 |

0.354 |

0.859 |

|

|

| SI |

0.305 |

0.265 |

0.227 |

0.208 |

0.830 |

|

| GCI |

0.417 |

0.325 |

0.301 |

0.453 |

0.139 |

0.821 |

Table 5.

Structural Model Analysis (Direct Effects).

Table 5.

Structural Model Analysis (Direct Effects).

| Structural Path |

β |

SD |

T |

P-VALUES |

5.00% |

95.00% |

R2 |

f2 |

VIF |

REMARKS |

| SR→GCI |

0.207*** |

0.032 |

6.456 |

0.000 |

0.147 |

0.274 |

0.277 (GCI) |

0.026 |

2.315 |

H1a Supported |

| AI→GCI |

0.119*** |

0.025 |

4.704 |

0.000 |

0.071 |

0.169 |

0.323 (GSI) |

0.017 |

2.262 |

H1b Supported |

| LPP→GCI |

0.104*** |

0.028 |

3.655 |

0.001 |

0.048 |

0.158 |

|

0.01 |

2.302 |

H1c Supported |

| GSI→GCI |

0.268*** |

0.03 |

8.868 |

0.001 |

0.209 |

0.324 |

|

0.072 |

2.146 |

Supported |

| SI→GCI |

-0.038 |

0.027 |

1.378 |

0.168 |

-0.091 |

0.015 |

|

0.003 |

1.967 |

Not Supported |

| SR→GSI |

0.343*** |

0.03 |

11.332 |

0.000 |

0.285 |

0.401 |

|

0.231 |

2.031 |

Supported |

| AI→GSI |

0.228*** |

0.026 |

8.784 |

0.000 |

0.177 |

0.277 |

|

0.104 |

2.029 |

Supported |

| LPP→GSI |

0.176*** |

0.027 |

6.467 |

0.001 |

0.125 |

0.23 |

|

0.052 |

2.162 |

Supported |

Table 6.

Mediation Analysis (Specific Indirect Effects).

Table 6.

Mediation Analysis (Specific Indirect Effects).

| Structural Path |

β |

SD |

t |

p-value |

5.00% |

95.00% |

Remarks |

| SR → GSI → GCI |

0.092 |

0.013 |

6.945 |

0.000 |

0.065 |

0.117 |

H2 Supported (Partial) |

| AI → GSI → GCI |

0.061 |

0.009 |

6.471 |

0.001 |

0.043 |

0.080 |

H2 Supported (Partial) |

| LPP → GSI → GCI |

0.047 |

0.009 |

5.250 |

0.000 |

0.029 |

0.063 |

H2 Supported (Partial) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).