Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

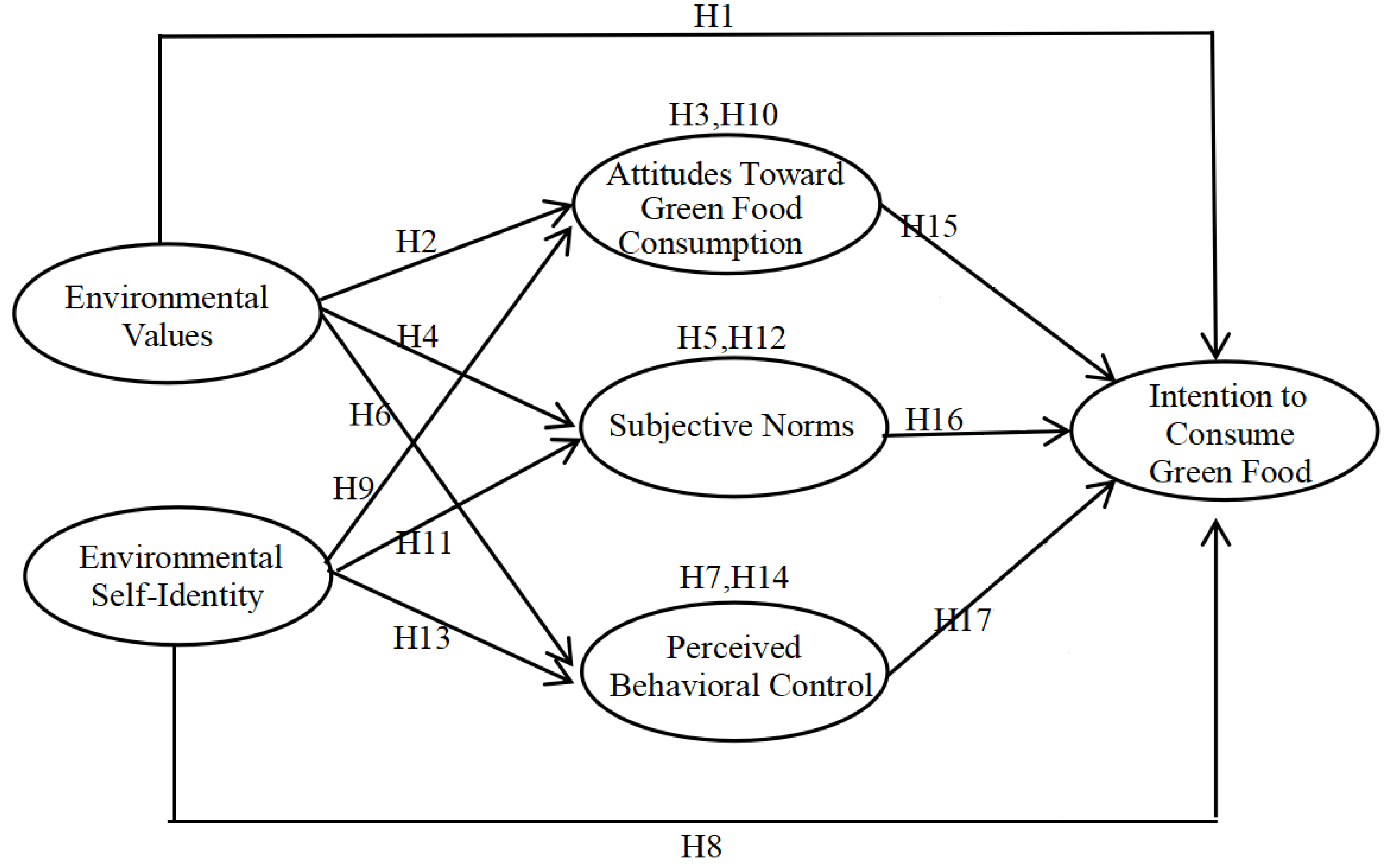

Sustainable development purposes require strong emphasis on green food promotion as an essential component. The decision-making process of Generation X members toward green food consumption creates important effects on both personal health and environmental sustainability and social programs and economic stability. This research examines environmental self-identity and environmental values as predictors of green food consumption intentions with analysis of attitude and relevant intermediate factors include personal standards as well as perceived control over behavior. The researcher gathered data through convenience sampling from 480 Chinese Generation X participants. Statistical analysis followed the pretest to perform assessments for reliability and validity testing. Structural equation modeling (SEM) processed the data while validating confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis testing. Data analysis validates environmental values drive green food consumption intentions through their impact on green food attitudes and the reinforcement of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control which results in ecological and social benefits promoting pro-environmental choices. The research shows self-identity as an environmental entity positively affects green food consumption because it strengthens users' self-belief as eco-conscious consumers leading to intensified attitudes and subjective norms and perception of behavior control. The research enriches the TPB (theory of planned behavior) by proving that environmental attitudes respond to environmental factors including social environments along with economic capacity and living conditions to shape generation X consumers' intentions to buy green food. The results enable both policymakers and marketers to create effective strategies in green food consumption of promotion.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The research evaluates both environmental value influence and Generation X consumption intentions toward green foods;

- The research examines how environmental self-identity influences Generation X members when it comes to intentions about green food consumption;

- The studies investigate the relationship between mindset, personal standards, and what is considered behavioral management. function as mediators when predicting intentions to consume green foods;

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Approach

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis Tool

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Statistical Analysis

4.2. Reliability Test

4.3. Validity Analysis

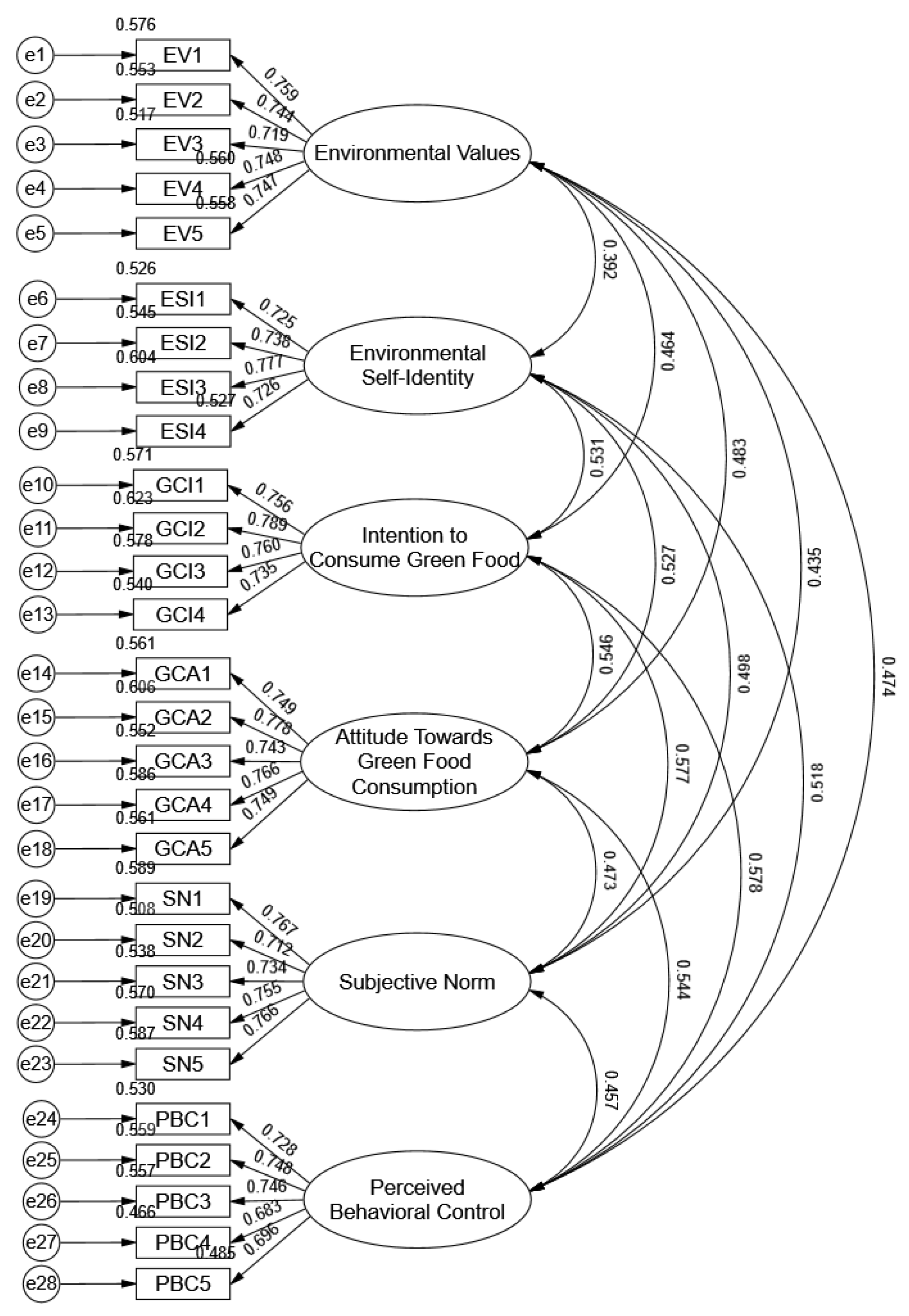

4.4. Measurement Model

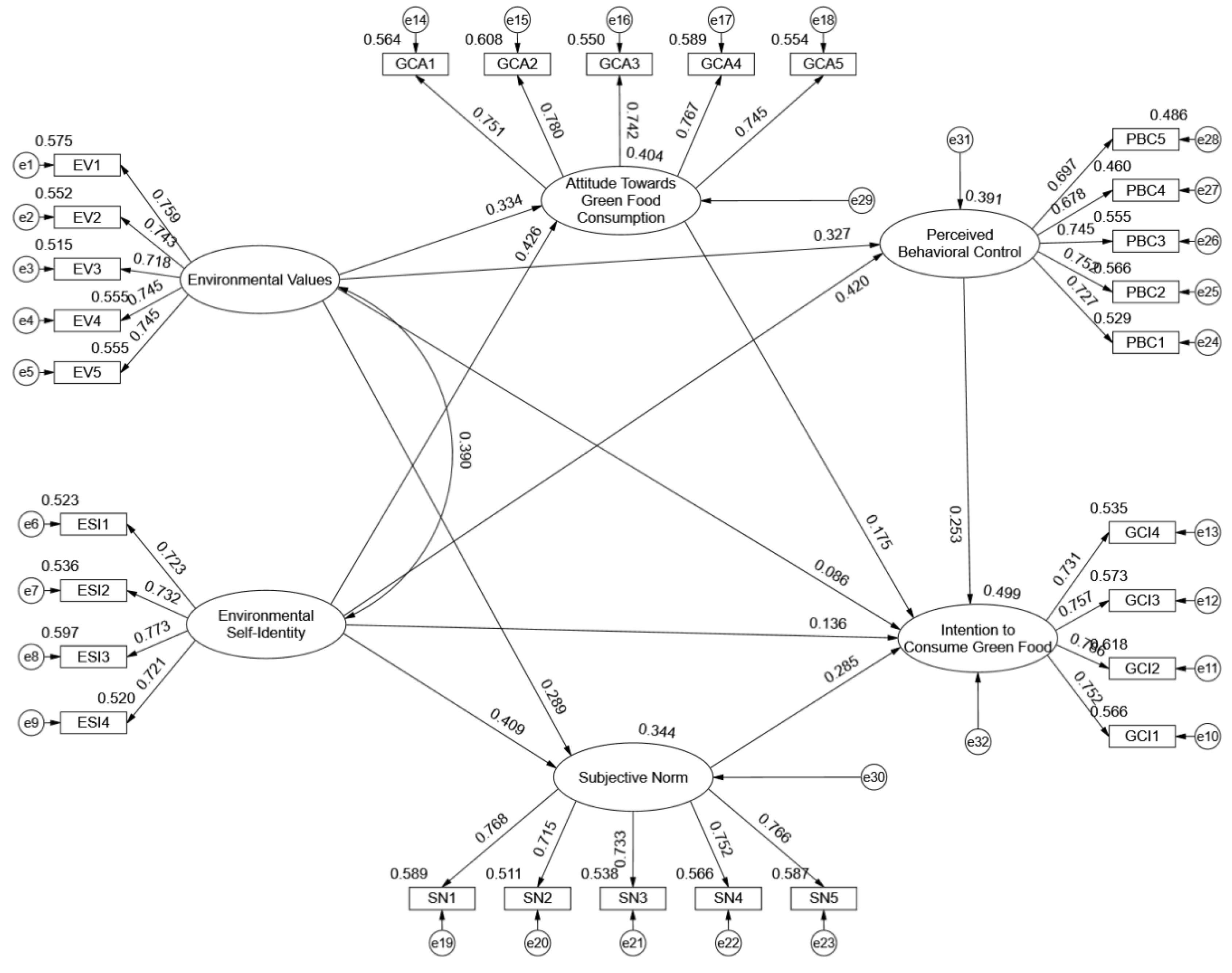

4.5. Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Conclusion

| Variable | Items |

| Environ-mental Values | EV1: It is important to me that my consumption does not cause harm to the environment. |

| EV2: When making many decisions, I consider the potential impact of my actions on the environment. | |

| EV3: My consuming habits are influenced by my concern for the environment. | |

| EV4: I worry about wasting our planet's resources. | |

| EV5: I am willing to make it inconvenient to take more environmentally friendly actions. | |

| Environmental Self-Identity | ESI1: I consider myself a consumer who actively chooses environmentally friendly products. |

| ESI2: I consider myself a person who is very concerned about environmental issues, and this concern influences many choices in my daily life. | |

| ESI3: If others praise me for having an environmentally friendly lifestyle, I can feel proud. | |

| ESI4: Purchasing green food makes me feel that I am an environmentally friendly consumer. | |

| Green Food Consumption Intention | GCI1: I am willing to choose and purchase green food continuously. |

| GCI2: I purchase green food even if the price is higher than typical food. | |

| GCI3: I plan to purchase green food in the near future. | |

| GCI4: I buy green food because it are eco-friendly. | |

| Attitude Towards Green Food Consumption | GCA1: I strongly support the behavior of purchasing green food. |

| GCA2: I believe that consuming green food can help to reduce pollution and also help to improve the environment. | |

| GCA3: I believe that consuming green food can help conserve natural resources. | |

| GCA4: Considering the potential health benefits of green food, I am willing to try and adopt this consumption choice. | |

| GCA5: I feel good about myself When I buy green food. | |

| Subjective norm | SN1: Most people who are important to me think I should consume green food. |

| SN2: Most people who are important to me advise me to consume green foods. | |

| SN3: Most people whose opinions I value advise me to choose green food. | |

| SN4:Most of the people I respect and admire choose green foods. | |

| SN5: I feel under social pressure to preserve the environment. | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1: Given my pension and savings, I tend to purchase green food. |

| PBC2: I have the resources, time and willingness to purchase green food. | |

| PBC3: If stores near my home sell green food and are easily accessible, I can regularly purchase green food. | |

| PBC4: I believe that with clear labeling, Generation X can quickly identify and choose green food. | |

| PBC5: There are likely to be plenty of opportunities for me to purchase green food. | |

| Green Food Knowledge |

GFK1: I am quite familiar with green food. |

| GFK2: I often see green food in shopping places. | |

| GFK3: I have often observed green food, although I did not make purchases. | |

| GFK4: I have often read articles or news about or have learned about green food. | |

| GFK5: It frightens me to imagine that many of the products I use disrupt the environment. | |

| GFK6: Humans are really abusing the environment. | |

| GFK7: The balance of nature is easily disrupted, especially by human activity. | |

| GFK8: It should take responsibility for environmental issues as we are the cause of the environment. |

References

- Tan, B.C.; et al. The effects of consumer consciousness, food safety concern and healthy lifestyle on attitudes toward eating “green”. British Food Journal 2022, 124, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; et al. Exploring the role of green and Industry 4.0 technologies in achieving sustainable development goals in food sectors. Food Research International 2022, 162, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; et al. The past, present, and future of sustainability marketing: How did we get here and where can we go? Journal of Business Research 2025, 187, 115056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M. Cultivating sustainable global food supply chains: A multifaceted approach to mitigating food loss and waste for climate resilience. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 442, 141037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K. Sustainable chemistry in adaptive agriculture: A review. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2024, 46, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; et al. Towards environmentally sustainable food systems: Decision-making factors in sustainable food production and consumption. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 26, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wen, J. Green public procurement and corporate environmental performance: An empirical analysis based on data from green procurement contracts. International Review of Economics & Finance 2024, 96, 103578. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; et al. Trends and challenges on fruit and vegetable processing: Insights into sustainable, traceable, precise, healthy, intelligent, personalized and local innovative food products. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 125, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; et al. Uncover the flavor code of strong-aroma baijiu: Research progress on the revelation of aroma compounds in strong-aroma baijiu by means of modern separation technology and molecular sensory evaluation. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 109, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Song, T. Green finance and food production: Evidence from cities in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 458, 142423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Y.; Liang, Q.-M.; Liu, L.-J. Impact of population ageing on carbon emissions: A case of China's urban households. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2023, 64, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X. Generational differences in automobility: Comparing America's Millennials and Gen Xers using gradient boosting decision trees. Cities 2021, 114, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.; et al. The generational cohort effect in the context of responsible consumption. Management Decision 2019, 57, 1162–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.A.; et al. Environmental sustainability and sustainable consumption: The perception of baby boomers, generation x and y in Brazil. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental 2017, 11, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; et al. Generational Differences in Sustainable Consumption Behavior among Chinese Residents: Implications Based on Perceptions of Sustainable Consumption and Lifestyle. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.M.; Rausch, T.M.; Brandel, J. The importance of sustainability aspects when purchasing online: Comparing generation X and generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synodinos, C.; Moraes, G.H.S.M.D.; Prado, N.B.D. Green food purchasing behaviour: A multi-method approach of Generation Y in a developing country. British Food Journal 2023, 125, 3234–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Shan, Z.; Wei, Z. Research on the construction and measurement of the indicator system for green low-carbon circular developing economic system in Southwest China. Ecological Indicators 2024, 160, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; et al. Optimal eco-label choice strategy for environmentally responsible corporations considering government regulations. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 418, 138013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. What does it take to drive young consumers to purchase green food? Perceived usefulness, environmental problem, or fear of pandemic recurrence? Cogent Food & Agriculture 2024, 10, 2413917. [Google Scholar]

- Ghouse, S.M.; et al. Green purchase behaviour of Arab millennials towards eco-friendly products: The moderating role of eco-labelling. The Bottom Line ahead-of-print. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Roubaud, D.; Grebinevych, O. Sustainable consumption behaviour: Mediating role of pro-environment self-identity, attitude, and moderation role of environmental protection emotion. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 347, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, B.; Chaturvedi, S.; Bhati, N.S. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to predict sustainable food consumption. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26, 31277–31300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martey, E.M. Purchasing behavior of green food: Using health belief model norm activation theory. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-C.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Y.-C. Extending the theory of planned behavior model to explain people’s behavioral intentions to follow China’s AI generated content law. BMC Psychology 2024, 12, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Qi, G. Enhancing sustainable consumer practices: The role of environmental knowledge in adopting BORS services. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenpour, Y.; et al. Towards predicting the pro-environmental behaviour of wheat farmers by using the application of value-belief-norm theory. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-S.; Chao, C.-T. Solutions to food waste: Investigating Taiwanese consumer attitudes and behavioral drivers toward upcycled food. British Food Journal ahead-of-print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; et al. The impact of impression construction consumption on social identity: A research on Chinese female professionals. Journal of Social Marketing 2023, 13, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-W. Utilizing a Hybrid Approach to Identify the Importance of Factors That Influence Consumer Decision-Making Behavior in Purchasing Sustainable Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, E. How Self-Identity and Social Identity Grow Environmentally Sustainable Restaurants’ Brand Communities Via Social Rewards. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2022, 48, 516–532. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Sui, D. Investigating college students' green food consumption intentions in China: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8, 1404465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. An integrated framework to explain consumers’ purchase intentions toward green food in the Chinese context. Food Quality and Preference 2021, 92, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho Filho, M.; et al. Awareness as a catalyst for sustainable behaviors: A theoretical exploration of planned behavior and value-belief-norms in the circular economy. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 368, 122181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and social Psychology 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polisetty, A.; et al. Examining the relationship between pro-environmental consumption behaviour and hedonic and eudaimonic motivation. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 359, 121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; et al. Predicting attitude and intention to reduce food waste using the environmental values-beliefs-norms model and the theory of planned behavior. Food Quality and Preference 2024, 120, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, T. Perceived green psychological benefits and customer pro-environment behavior in the value-belief-norm theory: The moderating role of perceived green CSR. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2023, 113, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; et al. A meta-analytic integration of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm model to predict green consumption. European Journal of Marketing 2024, 58, 1141–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; et al. Information as an enabler of sustainable food choices: A behavioural approach to understanding consumer decision-making. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 31, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Green purchase and sustainable consumption: A comparative research between European and non-European tourists. Tourism Management Perspectives 2022, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Ruepert, A. My company is green, so am I: The relationship between perceived environmental responsibility of organisations and government, environmental self-identity, and pro-environmental behaviours. Energy Efficiency 2021, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; et al. Environmental values and identities at the personal and group level. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 42, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, E.; Carrete, L.; Arroyo, P. A research of the antecedents and effects of green self-identity on green behavioral intentions of young adults. Journal of Business Research 2023, 155, 113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdi, F.M.; Al-Kahtani, S.M.; Abdullah, E.A.M.F. Saudi women’s attitude towards environmental marketing and its relationship to purchasing behavior. Discover Sustainability 2024, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Wu, W. Does green morality lead to collaborative consumption behavior toward online collaborative redistribution platforms? Evidence from emerging markets shows the asymmetric roles of pro-environmental self-identity and green personal norms. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 68, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, J.; et al. Can social information programs be more effective? The role of environmental identity for energy conservation. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2021, 108, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; et al. Activating employee pro-environmental behaviorin the workplace: The effects of environmental self-identity and behavioralintegrity. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; et al. Deciphering the dynamics of human-environment interaction in China: Insights into renewable energy, sustainable consumption patterns, and carbon emissions. Sustainable Futures 2024, 7, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining consumers' intentions towards purchasing green food in Qingdao, China: The amendment and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2019, 133, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; et al. Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to sustainable food consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; et al. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity with the theory of planned behavior. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, L.; Xu, Y. An investigation of determinants of green consumption behavior: An extended theory of planned behavior. Innovation and Green Development 2025, 4, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; et al. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. British Food Journal 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining Chinese consumers’ green food purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalco, A.; et al. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsaichia, S.; et al. Influences of green eating behaviors underlying the extended theory of planned behavior: A research of market segmentation and purchase intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Kim, O.Y.; Shim, S. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine factors influencing processed foods consumption behavior. Nutrition research and practice 2014, 8, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers' Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecological Economics 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaihanchanchai, P.; Anantachart, S. Encouraging green product purchase: Green value and environmental knowledge as moderators of attitude and behavior relationship. Business Strategy and the Environment 2023, 32, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-environmental purchase behaviour: The role of consumers' biospheric values. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 33, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varah, F.; et al. Exploring young consumers’ intention toward green products: Applying an extended theory of planned behavior. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 23, 9181–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Investigating the determinants of consumers’ sustainable purchase behaviour. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2017, 10, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; et al. Understanding the Influences on Green Purchase Intention with Moderation by Sustainability Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.; Salcedo, J. SPSS statistics for data analysis and visualization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; et al. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-F.; et al. Validity and reliability of the spiritual care competency scale for oncology nurses in Taiwan. BMC Palliative Care 2022, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz, K.; et al. Asymmetric impact of fossil fuel and renewable energy consumption on economic growth: A nonlinear technique. Energy 2021, 226, 120357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, G.; Ahmad, M.; Zhang, Q. Perceived critical factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase renewable generation technologies: Rural-urban heterogeneity. Energy 2021, 218, 119494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; et al. The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioral intention to consume organic food. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theory | Research Context | Findings | Source |

| Value-Attitude-Behavior (VAB) Model | Taiwanese consumers' behavioral intentions towards up cycled foods | Eco-conscious values significantly influence consumer attitudes and anticipated guilt, which in turn shape behavioral intentions towards up cycled foods. Product knowledge and green perceived quality are crucial in decision-making. | Chen [30] |

| VAB Model | Chinese consumers' willingness to pay for eco-agricultural products | Cultural values and trust in green food labels positively affect consumers' willingness to pay for green food, mediated by attitudes towards eco-agricultural innovations. | Li, Lin [25] |

| Social Identity Theory (SIT) | Social identity and green food consumption in Australia | Social identity significantly impacts sustainable food consumption behaviors; When green consumption is in line with the norms and values of their social group, people are more likely to practice it. | Jang and Kim [31] |

| TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior) | Sustainable food consumption behaviors among young consumers in India | Biospheric, egoistic, and hedonic values, along with environmental concern and identity, significantly shape beliefs, the impression of behavioral control and arbitrary standards. | Arya, Chaturvedi [23] |

| TPB + Norm Activation Theory | Green food consumption intentions among Chinese college students | Subjective norms, behavioral attitudes, and personal norms favorably impact consumers' intentions to buy green foods, highlighting the enhanced explanatory power of integrated frameworks. | He and Sui [32] |

| TPB (Meta-analysis) | Sustainable food consumption across different countries | There exists a substantial correlation between intentions and attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control to purchase green food, demonstrating TPB’s adaptability across cultures. | Qi and Ploeger [33] |

| Features | Frequency | Proportion | |

| Gender | Male | 232 | 48.3 |

| Female | 248 | 51.7 | |

| Age | 44-49 | 150 | 31.3 |

| 50-55 | 188 | 39.2 | |

| 56-59 | 142 | 29.6 | |

| Average Monthly Income | Below 2000 RMB | 11 | 2.3 |

| 2001-4000 RMB | 45 | 9.4 | |

| 4001-6000 RMB | 95 | 19.8 | |

| 6001-8000 RMB | 151 | 31.5 | |

| Above 8001 RMB | 178 | 37.1 | |

| Education Level | Junior High School or below | 148 | 30.8 |

| High School | 135 | 28.1 | |

| University | 128 | 26.7 | |

| Master's degree or above | 69 | 14.4 | |

| Research variables | Number of questions | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Values | 5 | 0.860 |

| Environmental Self-Identity | 4 | 0.830 |

| Intention to Consume Green Food | 4 | 0.846 |

| Attitude Towards Green Food Consumption | 5 | 0.870 |

| Subjective Norm | 5 | 0.863 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 5 | 0.843 |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.929 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 12232.550 |

| df | 630 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Fit index | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | NFI | TLI | CFI |

| Reference standards | <3 | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Result | 1.080 | 0.013 | 0.951 | 0.941 | 0.945 | 0.995 | 0.996 |

| Latent variables | Observation indicators | Factor loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Values | EV1 | 0.759 | 0.861 | 0.553 |

| EV2 | 0.744 | |||

| EV3 | 0.719 | |||

| EV4 | 0.748 | |||

| EV5 | 0.747 | |||

| Environmental Self-Identity | ESI1 | 0.725 | 0.830 | 0.551 |

| ESI2 | 0.738 | |||

| ESI3 | 0.777 | |||

| ESI4 | 0.726 | |||

| Intention to Consume Green Food | GCI1 | 0.756 | 0.846 | 0.578 |

| GCI2 | 0.789 | |||

| GCI3 | 0.760 | |||

| GCI4 | 0.735 | |||

| Attitude Towards Green Food Consumption | GCA1 | 0.749 | 0.870 | 0.573 |

| GCA2 | 0.778 | |||

| GCA3 | 0.743 | |||

| GCA4 | 0.766 | |||

| GCA5 | 0.749 | |||

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | 0.767 | 0.863 | 0.558 |

| SN2 | 0.712 | |||

| SN3 | 0.734 | |||

| SN4 | 0.755 | |||

| SN5 | 0.766 | |||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | 0.728 | 0.844 | 0.519 |

| PBC2 | 0.748 | |||

| PBC3 | 0.746 | |||

| PBC4 | 0.683 | |||

| PBC5 | 0.696 |

| Latent variables | EV | ESI | GCI | GCA | SN | PBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Values | 0.744 | |||||

| Environmental Self-Identity | 0.392 | 0.742 | ||||

| Intention to Consume Green Food | 0.464 | 0.531 | 0.760 | |||

| Attitude Towards Green Food Consumption | 0.483 | 0.527 | 0.546 | 0.757 | ||

| Subjective Norm | 0.435 | 0.498 | 0.577 | 0.473 | 0.747 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.474 | 0.518 | 0.578 | 0.544 | 0.457 | 0.720 |

| Fit index | TLI | GFI | AGFI | CFI | RMSEA | χ2/df | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference standards | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.08 | <3 | >0.9 |

| Result | 0.989 | 0.946 | 0.935 | 0.990 | 0.013 | 1.179 | 0.939 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimate | β | S.E. | C.R. | P | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EV→GCI | 0.336 | 0.334 | 0.053 | 6.341 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | EV→GCA | 0.428 | 0.409 | 0.060 | 7.182 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | EV→SN | 0.344 | 0.327 | 0.057 | 6.050 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | EV→PBC | 0.296 | 0.289 | 0.055 | 5.417 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | ESI→GCI | 0.439 | 0.426 | 0.058 | 7.603 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | ESI→GCA | 0.451 | 0.420 | 0.062 | 7.296 | *** | Supported |

| H11 | ESI→SN | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.059 | 2.965 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H13 | ESI→PBC | 0.281 | 0.285 | 0.056 | 4.995 | *** | Supported |

| H15 | GCA→GCI | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.059 | 1.462 | 0.144 | Non-supported |

| H16 | SN→GCI | 0.140 | 0.136 | 0.071 | 1.973 | 0.048 | Supported |

| H17 | PBC→GCI | 0.243 | 0.253 | 0.058 | 4.188 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Mediation path | Size Effect | S.E. | Bias-Corrected | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95%CI | ||||||

| H3 | EV→GCA→GCI | 0.059 | 0.032 | 0.003 | 0.128 | Supported |

| H10 | ESI→GCA→GCI | 0.077 | 0.042 | 0.004 | 0.174 | Supported |

| H5 | EV→SN→GCI | 0.083 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.141 | Supported |

| H12 | ESI→SN→GCI | 0.120 | 0.050 | 0.035 | 0.230 | Supported |

| H7 | EV→GCA→GCI | 0.084 | 0.035 | 0.019 | 0.158 | Supported |

| H14 | ESI→PBC→GCI | 0.110 | 0.044 | 0.029 | 0.199 | Supported |

| Path effect | Size Effect’s | SE | Bias-Corrected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95%CI | ||||

| EV→GCA | 0.336 | 0.071 | 0.186 | 0.471 |

| ESI→GCA | 0.439 | 0.075 | 0.298 | 0.579 |

| EV→PBC | 0.344 | 0.075 | 0.197 | 0.488 |

| ESI→PBC | 0.451 | 0.084 | 0.294 | 0.619 |

| EV→SN | 0.296 | 0.070 | 0.141 | 0.413 |

| ESI→SN | 0.428 | 0.087 | 0.265 | 0.615 |

| EV→GCI | 0.312 | 0.071 | 0.169 | 0.453 |

| ESI→GCI | 0.447 | 0.083 | 0.296 | 0.633 |

| GCA→GCI | 0.175 | 0.088 | 0.007 | 0.355 |

| PBC→GCI | 0.243 | 0.085 | 0.066 | 0.398 |

| SN→GCI | 0.281 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.482 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).