1. Introduction

Climate change is commonly regarded as the most significant issue facing the globe today due to the significant increase in carbon emissions caused by human activities in recent years (Kaida and Kaida, 2016; Yin and Shi, 2019). The private and public spheres are the two domains into which Mi et al. (2020) have divided pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs). In this context, private-sphere pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) includes things like recycling, water and electricity conservation, waste sorting, and other activities people do in their daily lives and workplaces. Consequently, private-sector PEB has a direct impact on environmental conservation. In contrast, public-sphere PEB involves deliberate efforts to advocate for environmental laws, policies, and programs with the aim of exerting influence on social or political organizations. Thus, public-sphere PEB indirectly promotes environmental conservation.

Stern et al. (1999) expand the sequential process of the original norm activation framework by including values and ecological worldviews in the pro-environmental context, resulting in the development of a Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) framework. The theory’s applicability in different environmental contexts and the sequential procedure of study variables within the VBN theory have been supported by substantial evidence. An ecological worldview encourages individuals to perceive environmental risks, leading to a sense of responsibility and motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, ultimately forming behavioral intentions for sustainable practices. (Stern, 2000; De Groot et al., 2007; Klöckner, 2013). Many factors influence pro-environmental behaviors, such as perceived behavioral control, perceived effectiveness, anticipated positive/negative emotion, environmental attitude, environmental awareness, environmental knowledge, new environmental paradigm, environmental self-identity, personal norm, social norm, ascription of responsibility, biospheric value, egoistic value, altruistic value (Lin et al., 2022). However, there is a limited number of researches that discuss the influence of minimalism and environmental concern on pro-environmental behaviours in collectivist cultures at emerging economy countries (Butt, 2017; De Canio et al., 2021; Esfandiar et al., 2022; Druică et al., 2023). Thus, within the field of environmental psychology, minimalism has gained greater importance as a determinant of pro-environmental behaviours.

Kang et al. (2021) notes that minimalism, a significant lifestyle movement, first became popular in Asian countries, particularly Japan. Minimalism calls for re-evaluating life priorities, moving away from the accumulation of goods, and deriving satisfaction from relationships and activities that bring more substance to life (Matte et al., 2021). However, according to Druică et al. (2023), not many academics investigate minimalism and the adoption of a minimalist lifestyle in collectivist cultures. Furthermore, while minimalism is a worldwide trend, it would be important to investigate whether national cultures have different standards for what constitutes a minimalist consumer and whether the degree of simplicity varies among them, particularly in collectivist cultures (Pangarkar et al., 2021). In additional, minimalism promotes a simplified lifestyle, reducing possessions and avoiding overconsumption, with environmental benefits (Kang et al., 2021; Lee & Ahn, 2016; Pangarkar et al., 2021).

Environmental concern refers to the overall attitude of consumers towards the preservation of the environment (Chen and Chai, 2010; Wei et al., 2018). Specifically, it is well recognised as a powerful factor that shapes consumers’ motivations to embrace a sustainable way of life (Newton et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2018). Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (2012) established a clear connection between individuals’ environmental concern and their likelihood to buy green energy brands. The study conducted by De Canio et al. (2021) investigates how environmental concern acts as a moderator in the relationship between external factors and consumers’ intentions to make pro-environmental purchases. The research findings indicate that environmental concern has a beneficial influence on consumers’ purchase intentions. In contrast, prior research has examined environmental concern in developed countries with individualistic cultures, such as Italy (De Canio et al., 2021) and the Republic of Korea (Ju & Hun Kim, 2022). There has been limited study on the relationship between environmental concern and green purchasing intention in collectivist cultures (Sreen et al., 2018; Tam & Chan, 2018; De Canio et al., 2021).

Green purchasing, as defined by Chan (2001), refers to the procurement of services and items that have minimal negative impact on the environment. Green buying intention refers to customers’ desire to acquire and pay for environmentally friendly items (Zaremohzzabieh et al., 2021). This intention is commonly associated with the colour green. Research on green purchase intention has been conducted in developed countries such as Korea (Han, 2015; Lee, 2017) and Taiwan (Rahimah et al., 2018). However, there is a lack of study on green purchase intention in emerging economy countries (Amin & Tarun, 2020). In additional, there is academic evidence suggesting that pro-environmental behaviour has an impact on green buying intention, as indicated by studies conducted by Barbarossa & Pelsmacker (2016) and Mostafa (2007).

Pro-environmental behaviours refers to any activity that has a beneficial effect on the environment or minimises harm to the environment (Casaló et al., 2019; Lange & Dewitte, 2019; Larson et al., 2015; Steg & Vlek, 2009). These individuals will promote product use in a manner that minimises the use of resources, lowers waste, and conserves materials and energy to have a lesser negative impact on our world (Rahimah et al., 2018). The private and public spheres are the two domains into which Mi et al. (2020) have divided pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs). In this context, private-sphere pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) includes things like recycling, water and electricity conservation, waste sorting, and other activities people do in their daily lives and workplaces. Consequently, private-sector PEB has a direct impact on environmental conservation. In contrast, public-sphere PEB involves deliberate efforts to advocate for environmental laws, policies, and programs with the aim of exerting influence on social or political organizations. Thus, public-sphere PEB indirectly promotes environmental conservation. The studies conducted by Casaló et al. (2019), Irawan et al. (2022), Kronrod et al. (2023), and Kong & Jia (2023) have found that pro-environmental behaviours as outcome in model research. However, there is research suggesting that pro-environmental behaviours can be seen as antecedents, as demonstrated by Composto et al. in 2023. Although many research examine the impact of various factors, they do not consider the mediating effect of pro-environmental behaviours (Bülbül et al., 2023). This study aims to enhance the existing literature by examining the mediation role of pro-environmental behaviours, both in public and private contexts.

This study provides further evidence for green purchase intention in emerging economy countries. In addition, this paper explores the mediating role of pro-environmental behaviours. Specifically, the paper shows how pro-environmental behaviours mediates between minimalism and green purchase intention. Moreover, this paper seeks to advance the existing literature by examining the mediating role of pro-environmental behaviours in the relationship between collectivist cultures and green purchase intention. Lastly, this paper examines the mediating role of pro-environmental behaviours in the relationship between environmental concerns and green purchase intention.

The research is organised as follows: we start by explaining the theoretical foundations of this investigation, and then proceed to formulate our assumptions. Afterwards, we clarify our sample and provide a thorough explanation of our data gathering methodology. The next part provides an analysis of the data and shows the results. Lastly, we analyse the consequences of our discoveries and propose potential avenues for further research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Pro-Environmental Behaviours as Mediator of the Minimalism and Green Purchase Intention Relationship

Minimalism has been defined using several definitions. It may be described as a refined sense of style that is conveyed via minimalistic design, thoughtful longevity, and minimalist aesthetics, such as in the fields of architecture, fashion, and interior decoration (Wilson & Bellezza, 2022). There have been recent studies on minimalism. Several studies indicate that minimalism has a significant influence on consumer happiness and financial well-being (Malik & Ishaq, 2023), as well as contributing to emotional well-being (Kang et al., 2021). Furthermore, Chen and Liu (2023) discovered that individuals with lower socioeconomic status express less positive assessments of brands that utilise minimalist appeals. This is because these consumers typically prioritise quantity over quality in their daily consumption, which contradicts the principles of minimalism. However, according to a recent study by Druică et al. (2023), there hasn’t been much research discussion on minimalism and living a minimalist lifestyle in contexts of collectivist culture to date. The body of research on minimalism that is now available tends to focus primarily on individualistic countries, leaving a gap in understanding of the perspectives and experiences of those who choose minimalist living within collectivist cultural frameworks. Additionally, even though minimalism has clearly become popular worldwide, it would be beneficial to look into whether different national cultures have different ideas about what a minimalist consumer should be like, as well as whether the level of asceticism and simplicity that characterises minimalist lifestyles varies depending on the cultural context, especially in collectivist cultures (Pangarkar et al., 2021).

Minimalism encompasses several characteristics, such as personal development and environmental sustainability (Kropfeld et al., 2018; Kasser, 2017). When consumers experience the negative effects of environmental degradation in their daily lives, individuals who prioritise self-improvement and minimalism are more likely to be concerned about environmental issues (Kuanr et al., 2020). They also tend to engage in pro-environmental behaviours such as recycling, conserving water and electricity, sorting waste, and other similar activities both at home and in their workplaces (Legere and Kang, 2020; Mi et al., 2020). In additional, individuals with pro-environmental behaviors will purchase and consume green-positioned products, such as eco-friendly tissue paper, biodegradable detergents, and energy-saving light bulbs (Barbarossa & Pelsmacker, 2016), and eventually, green purchase intention will be formed inside them.

Additionally, Dagiliūtė’s (2023) study examines the influence of various environmental information sources on pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) among citizens of the EU. Television, internet, and newspapers are seen as the main sources, whereas scientific literature is deemed the most substantial predictor of pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs). Gender, age, and income are all significant sociodemographic characteristics that influence environmental behaviour. Furthermore, Li et al. (2024) investigate the effect of environmental rules and green marketing on Chinese consumers’ willingness to purchase eco-friendly things. It shows that both environmental restrictions and green marketing considerably increase customer intentions to buy eco-friendly items, with regional differences in efficacy.

The term “green purchase intention” describes consumers’ propensity to purchase environmentally friendly products because of their favourable health impacts and ability to protect the environment for future generations (Fraj and Martinez, 2007; Benvenuti et al., 2016). This study will bring something special and practical to the body of current knowledge. Consequently, we recommend the following:

H1: Pro-environmental behaviours have a positive mediating relationship between minimalism and Green purchase intention.

2.2. Pro-Environmental Behaviours as Mediator of Collectivist Culture and Green Purchase Intention

Collectivism refers to the extent to which individuals in a society are incorporated into various social groupings (Sreen et al., 2018). In a collectivist cultures, individuals are automatically part of close-knit social groupings and frequently have large extended families from the moment they are born. In this type of culture, the in-group provides absolute allegiance and protection to all its members (Sreen et al., 2018). The notion of collectivist cultures is based on the idea that individual behaviours should be guided by the interests of the community first (Mi et al., 2020). Studies on consumers’ intentions to buy green products have been carried out in developed countries like Taiwan and South Korea. For instance, research on South Korean customers’ inclination to make green purchases was carried out by Han (2015) and Lee (2017). The study found that factors such as environmental consciousness, perceived efficacy, and social influence can impact the tendency of South Korean consumers to purchase green products. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of research investigating the inclination to make green purchases intention in developing countries and collectivist cultures. Amin and Tarun (2020) observed that prior studies on green purchase intention have predominantly concentrated on developed countries and individualistic cultures, highlighting the necessity for further investigation into green purchasing intention in emerging economy countries and collectivist cultures. In additional, previous studies have shown that those who identify as collectivists show more concern for environmental (Arısal & Atalar, 2016). Furthermore, collectivist cultures has a favorable impact on pro-environmental behaviours (Segev, 2015), green purchase intentions (Sheng et al., 2019), and green purchasing behaviours (Kim, 2011; Wang, 2014). On the other hand, there will be some behavioral impact from government groups that promote pro-environmental behavior patterns. Similarly, a well-known individual’s pro-environmental behaviours also have a cascading influence on the community under collectivist cultures. In addition, those who embrace collectivist cultures may minimise any personal advantages or individual outcomes that arise from their environmentally conscientious purchases. Undoubtedly, individuals are prepared to relinquish their own interests if it leads to advantageous outcomes for the broader population (Le et al., 2019).

Customers in individualist cultures tend to directly purchase green products, as they believe purchasing green products is a good idea and have a favorable attitude towards purchasing a green version of a product (Cho et al., 2013). On the other hand, customers in collectivist cultures are inspired by their society and prefer to engage in pro-environmental behaviours. In additional, the study of Mi et al. (2020) suggests that people who adhere to collectivist cultures are more likely to engage in public-sphere pro-environmental behaviours such as participating in signing together to support pro-environmental policies or regulations, participate in environmental complaints or proactively reporting pollution incidents, participating in green donation activities organized by community. This, in turn, leads to a desire to make green purchases intention because of the shared aims of the community. (Sreen et al., 2018). Standardisation is a crucial technique for promoting pro-environmental behaviours since the political beliefs of individuals have an impact on their attitudes towards consumption (Pandey & Yadav, 2023). Pandey & Yadav’s (2023) research demonstrated a favourable correlation between political concern and green purchase intention.

In additional, the study by Sova et al. (2024) examines disparities in green innovation across nations with individualistic and collectivist cultural orientations. It concludes that individualistic nations, on average, excel in green innovation, propelled by superior socioeconomic growth and more R&D spending. Collectivist nations, although being more focused on group dynamics, often have lower green innovation scores owing to a lack of support for innovation within their cultural paradigms. The research highlights the relevance of socioeconomic success in promoting green innovation in a range of cultural situations. Furthermore, Riaz et al. (2023) investigate the influence of individual cultural value discrepancies on pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) among international students attending Korean colleges. Collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation all have a positive effect on both private and public-sphere pro-environmental activity, but masculinity has a negative impact on public-sphere pro-environmental behaviour. Power distance has no significant impact on any kind of pro-environmental behaviour (PEB).

On the other hand, the impact of collectivist cultures on green purchase intention has been the subject of conflicting findings in the context of emerging markets in earlier research. Varshneya et al. (2017) proposed that collectivist cultures has no effect on green purchase behaviour or intention for products that have not yet been widely available. However, a different study on emerging markets (Nguyen et al., 2017) demonstrates that communities that collectivst cultures have a great green purchase intention. This research will make a distinct and valuable contribution to the current body of knowledge. Thus, we propose the following:

H2: Pro-environmental behaviours have a positive mediating relationship between Collectivist culture and Green purchase intention.

2.3. Pro-Environmental Behaviours as Mediator of Environmental Concern and Green Purchase Intention

Environmental concerns indicate a community’s “attitudes about environmental issues or perceptions that such issues are important” (Cruz, 2017), such as worries over anthropogenic climate change (Howe et al., 2015). For example, environmental concern might heighten social pressure regarding limiting the use of pesticides and trash (Farrow et al., 2017). Moreover, environmental concern may strengthen community cohesion and collaboration (Longhofer et al., 2019). Environmental concern has explicit components that include energy conservation, clean energy and alternative energy source awareness, and sensitivity to climate change challenges (Zimmer et al., 1994), engaging in environmentally conscious actions, and endorsing environmental advocates (Alzubaidi et al., 2020; Polonsky et al., 2014; Yadav & Pathak, 2016). Overall, environmental concerns in a community are likely to be positively related to environmentally-friendly consumption. Residents in communities with stronger environmental concerns are more aware of sustainability issues and believe to a greater degree that protecting the environment is the right thing to do, thus exhibiting a greater tendency to purchase green products (Ajzen, 1991). On the other hand, the research of Maduku (2024) shows that environmental concern, which are largely self-serving, reflect a person’s concern about the environment because of the effects that environmental degradation may have on them. In additional, according to scholars like Alzubaidi et al. (2020), Polonsky et al. (2014), and Yadav & Pathak (2016), environmental concerns have a direct and indirect influence on promoting pro-environmental behaviors, such as purchasing environmentally friendly products, embracing low-carbon lifestyles, making sustainable purchases. For over 30 years much social research has explored the roots of direct and indirect environmental behaviour, specifically looking at the relationship between concern for the environment and pro-environmental behaviour. As mentioned in the previous section, pro-environmental behaviour is often defined as behaviour that minimises an individual’s negative impact on the natural world (Rhead et al., 2015). Furthermore, conformance standards stemming from environmental concerns among consumers with pro-environmental behaviors may promote green purchase intention (Delmas & Lessem, 2014; Mont, 2004).

Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (2012) established a clear and direct relationship between the extent of customers’ environmental concern and their inclination to purchase brands associated with green energy. Their study unveiled that customers’ heightened environmental awareness and concern directly led to a greater propensity to choose energy products that are environmentally beneficial. Expanding on previous research, De Canio et al. (2021) performed a study that further examined the influence of environmental concern on the connection between external conditions and consumers’ propensity to make environmentally friendly choices. Research indicates that environmental concern positively influences customers’ propensity to participate in sustainable purchasing activities. Previous research on this subject have mostly concentrated on developed countries with individualistic culture, such as Italy (De Canio et al., 2021) and the Republic of Korea (Ju & Hun Kim, 2022).

Kosic et al. (2024) investigate how social anxiety, self-efficacy, comprehension of global warming, and environmental concern impact public-sector pro-environmental behaviours. According to study, social anxiety harms PBS-PEBs, but knowledge of global warming enhances them. Self-efficacy and traditional environmental concern had minimal direct impact, emphasising the need of reducing social anxiety and increasing awareness of global warming in order to increase PBS-PEBs. In addition, Cui et al. (2024) investigate the association between green buying intention, compensating spending, and pro-environmental behaviour. It discovers that customers with stronger green buying intents may engage in compensating spending to alleviate guilt about environmental damage. Pro-environmental behaviour modifies this link, emphasising the psychological and social variables that drive green consumption.

However, there has been a lack of academic focus on investigating the relationship between environmental concern and the desire to green purchase intention in emerging economy countries (Sreen et al., 2018; Tam & Chan, 2018; De Canio et al., 2021). Numerous studies attest to the fact that consumers’ concerns about the environment affect their decisions to buy ecologically friendly items (Balderjahn, 1988; Roberts & Bacon, 1997). This research will make a distinct and valuable contribution to the current body of knowledge. Thus, we propose the following:

H3:

Pro-environmental behaviours have a positive mediating relationship between Environmental concern and Green purchase intention.

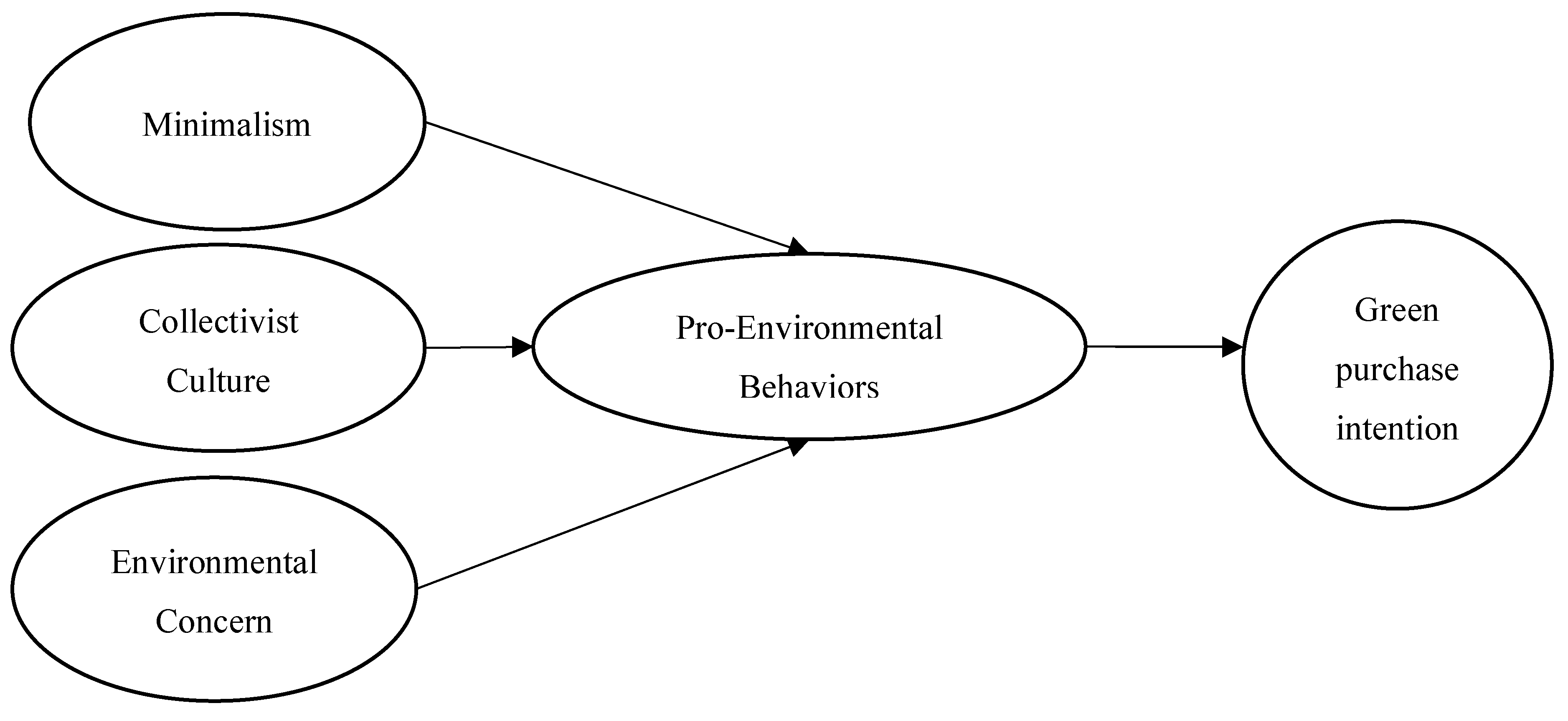

Figure 1.

Research model and proposed hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Research model and proposed hypotheses.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

In accordance with Yamane Taro’s methodology (1967), when the population size is unknown, the sample size (n) can be determined using the formula:

Where:

Z is the critical value obtained from the Z-distribution table, typically chosen to correspond to a 95% confidence level, denoted as Z = 1.96.

represents the estimated success rate, and a common practice is to set to maximize the product , ensuring prudence in sample size estimation.

is the margin of error, often expressed as a percentage, with popular choices being ±0.01 (1%), ±0.05 (5%), or ±0.1 (10%).

Hence, the minimum required sample size The study sample was mostly drawn from Vietnam’s cities of Hanoi, Da Nang, and Ho Chi Minh. The three cities selected are representative of the northern, central, and southern regions of Vietnam, and therefore the sample will be broadly representative of the entire country of Vietnam.

The sample carried out in these cities is considered comprehensive and indicative of the many demographic groupings in the country. The convenience sample approach was employed for those aged twenty years and above. The survey locations were strategically chosen to prioritise significant industrial zones, popular tourist destinations, large commercial centres, and heavily inhabited residential regions.

A strong dataset for the investigation was ensured by the collection of 385 genuine questionnaires for processing. This method makes it easier to grasp the thoughts and actions of the participants in connection to their surroundings while also offering a clearer knowledge of the larger context of these significant Vietnamese cities.

3.2. Scale Operationalization and Questionnaire Design

In order to assess the components under investigation, it was imperative to make suitable adjustments to pre-existing measuring scales. The three antecedents, namely environmental concern, minimalism, and collective culture, were assessed utilizing an instrument called the 5-point Likert scale. The study articles from which these scales were derived were Le et al. (2019) 5-item scale, Ju & Hun Kim (2022) 3-item scale, and Kang et al. (2021) 6-item scale.

The mediator of the study, Pro-Environmental Behaviours, was divided into two distinct dimensions: Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Private) and Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Public). The dimensions under consideration were assessed utilizing a 5-point Likert scale, in accordance with the methodology devised by Mi et al. (2020), wherein each dimension comprises four to five items. In additional, the outcome variable, Green Purchase Intention, was also assessed using a three-item scale derived from the work of Pandey and Yadav (2023).

Considering that the data collection was conducted in Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, and Da Nang, a locale where English is not the native language, a systematic translation process was implemented to accurately translate the scale items into Vietnamese.

4. Results

This research predominantly utilized Partial Least Squares (PLS) structural equation modeling, specifically employing SmartPLS 4.0 software, for the analysis of the collected data.

4.1. Demographics Scale

The demographic analysis of this study indicates a nearly equal distribution of genders, with both males and females being represented in roughly equal amounts. The majority of the sample is made up of individuals who have completed an undergraduate degree, which accounts for 36.9% of the total. The age group between 30 and 39 comprises the largest proportion, accounting for 47.5% of the respondents in the sample. Furthermore, the people who were polled own a mean monthly wage ranging from 10 to 20 million VND (equivalent to around 390 USD to 785 USD).

Table 1.

Demographics scale.

Table 1.

Demographics scale.

| Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Gender |

|

|

| Male |

196 |

50.9 |

| Female |

189 |

49.1 |

| Total |

385 |

100 |

| Education Background |

|

|

| Junior high or below |

80 |

20.8 |

| Senior high |

106 |

27.5 |

| Undergraduate |

142 |

36.9 |

| Graduate and above |

57 |

14.8 |

| Total |

385 |

100 |

| Age |

|

|

| 20-29 |

34 |

8.8 |

| 30-39 |

183 |

47.5 |

| 40-49 |

137 |

35.6 |

|

50 |

31 |

8.1 |

| Total |

385 |

100 |

| Monthly income (Million VNĐ) |

|

|

|

10 |

34 |

8.8 |

|

|

152 |

39.5 |

|

|

104 |

27 |

|

30 |

95 |

24.7 |

| Total |

100 |

385 |

4.2. Structural Model Assessment and Direct Effects Examination

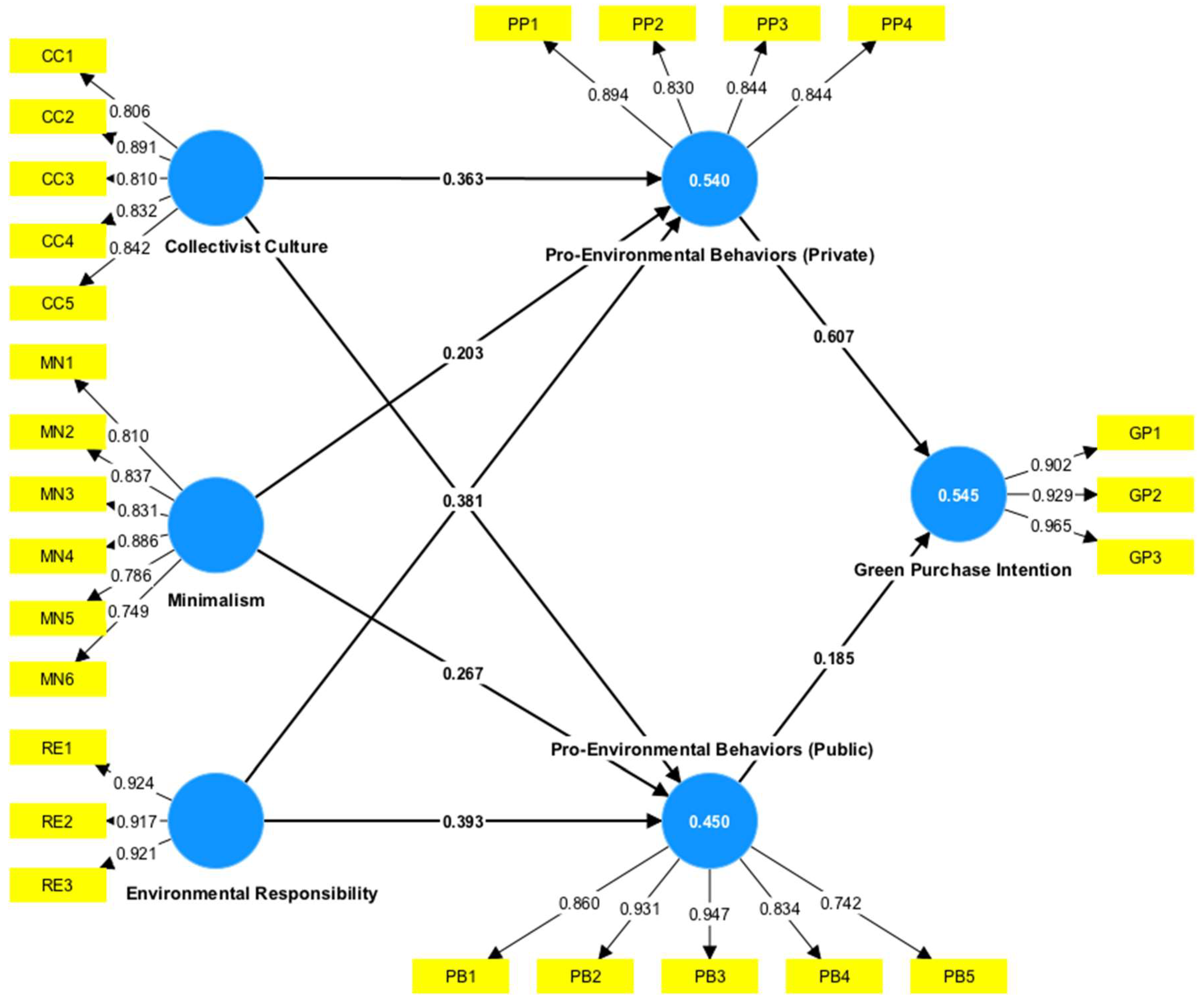

In “A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM),” Hair et al. (2017) described a framework for evaluating the reflective scale quality of observed variables. The outer loading coefficients were computed using the PLS-SEM technique in order to ascertain the relevance of these observable factors. A benchmark of 0.7 or above was proposed by Hair et al. as a good significance measure for the variables that were observed. In additional, the study’s observed variables for the following constructs showed outer loadings between 0.806 and 0.891, 0.902 to 0.965, 0.749 to 0.886, 0.742 to 0.947, 0.830 to 0.894, and 0.917 to 0.921, respectively: Collectivist Culture; Green purchase intention; Minimalism; Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Public); Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Private); and Environmental Concern. These results show that every observed variable in the study model met Hair et al.‘s proposed criterion for strong significance.

Table 2.

Outer loadings.

| |

Collectivist Culture |

Green Purchase Intention |

Minimalism |

PEBs (Public) |

PEBs (Private) |

Environmental Concern |

| CC1 |

0.806 |

|

|

|

|

|

| CC2 |

0.891 |

|

|

|

|

|

| CC3 |

0.810 |

|

|

|

|

|

| CC4 |

0.832 |

|

|

|

|

|

| CC5 |

0.842 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GP1 |

|

0.902 |

|

|

|

|

| GP2 |

|

0.929 |

|

|

|

|

| GP3 |

|

0.965 |

|

|

|

|

| MN1 |

|

|

0.810 |

|

|

|

| MN2 |

|

|

0.837 |

|

|

|

| MN3 |

|

|

0.831 |

|

|

|

| MN4 |

|

|

0.886 |

|

|

|

| MN5 |

|

|

0.786 |

|

|

|

| MN6 |

|

|

0.749 |

|

|

|

| PB1 |

|

|

|

0.860 |

|

|

| PB2 |

|

|

|

0.931 |

|

|

| PB3 |

|

|

|

0.947 |

|

|

| PB4 |

|

|

|

0.834 |

|

|

| PB5 |

|

|

|

0.742 |

|

|

| PP1 |

|

|

|

|

0.894 |

|

| PP2 |

|

|

|

|

0.830 |

|

| PP3 |

|

|

|

|

0.844 |

|

| PP4 |

|

|

|

|

0.844 |

|

| RE1 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.924 |

| RE2 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.917 |

| RE3 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.921 |

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, which ranges from 0 to 1, measures the internal consistency or dependability of a set of observable variables within a construct. A value of 1 indicates complete correlation between the observed variables, while 0 indicates no correlation at all. Values at these extremes are not often seen in data analysis. According to Nunnally’s (1978) theory, a scale must have a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.7 or above in order to be deemed credible. Similarly, a unidimensional and trustworthy scale should fulfil or beyond a 0.7 criterion, according to Hair et al. (2010). Nonetheless, 0.6 is sometimes considered enough for Cronbach’s Alpha in the context of exploratory study. In additional, within this investigation, the constructs of Minimalism, Green Purchase Intention, Environmental Concern, Collectivist Culture, Pro-Environmental Behaviours (PEB) Private, and PEB Public have Cronbach’s Alpha values ranging from 0.875 to 0.924. The scales connected to these variables have a high degree of dependability, as shown by these values.

Convergent validity is achieved when the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of a scale reaches or exceeds 0.5, as stated by Hock and Ringle (2010). According to this standard, it is suggested that the underlying concept should, on average, explain at least 50% of the differences in its measurable factors. For the constructs of Collectivist Culture, Environmental Concern, Green Purchase Intention, Minimalism, Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Private), and Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Public) in the present research, the AVE values are 0.7, 0.847, 0.869, 0.668, 0.728, and 0.750, in that order. Since all of these results significantly above the 0.5 threshold, all of the measurement scales used in this study are shown to have convergent validity.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

| |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Average variance extracted (AVE) |

| Collectivist Culture |

0.893 |

0.700 |

| Environmental Concern |

0.910 |

0.847 |

| Green Purchase Intention |

0.924 |

0.869 |

| Minimalism |

0.900 |

0.668 |

| PEB (Private) |

0.875 |

0.728 |

| PEB (Public) |

0.915 |

0.750 |

The heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) index is a technique introduced by Henseler et al. (2015) to evaluate the extent to which different traits are distinct from each other. The underlying idea of this technique is that the average correlations inside a concept have greater significance than the average cross-correlations across various notions. A greater mean correlation within the construct indicates a stronger degree of shared variance across the latent variables of a concept, indicating its robustness in terms of internal consistency. Smaller average cross-correlations, on the other hand, show less shared variance with other latent variables, which is indicative of discriminant validity. In additional, a breach of discriminant validity is indicated, according to Henseler et al. (2015), if the HTMT index for a pair of constructs is more than 0.9. The opposite is also true: a low HTMT score (less than 0.85) indicates strong discriminant validity. For the purpose of guaranteeing discriminant validity, a range of 0.85 to 0.9 is thus deemed suitable. Additionally, the current investigation shows that all of the construct average correlation coefficients are below the 0.9 cutoff. According to this finding, the constructs used in this study provide sufficient evidence of their discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

| |

Collectivist Culture |

Environmental Concern |

Green Purchase Intention |

Minimalism |

PEB (Private) |

PEB (Public) |

| Collectivist Culture |

|

|

|

|

| Environmental Concern |

0.510 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Green Purchase Intention |

0.530 |

0.636 |

|

|

|

|

| Minimalism |

0.259 |

0.421 |

0.403 |

|

|

|

| PEB (Private) |

0.663 |

0.699 |

0.803 |

0.484 |

|

|

| PEB (Public) |

0.492 |

0.643 |

0.616 |

0.516 |

0.708 |

|

Due to variations in complexity among models, Hair et al. (2017) argue that it is challenging to define a universal criterion for accepting R-squared values. This complexity can be attributed to several factors that impact the dependent variable, the presence of mediating relationships, and changes in study domains. Due to this, it is not feasible to create a universally applicable criterion that can conclusively determine if R-squared values are sufficient. In additional, the R-squared value, ranging from 0 to 1, indicates the extent to which the variance in the dependent variable is accounted for. Values nearing 1 imply greater levels of explained variation, whereas values nearing 0 indicate lower levels of explained variance. Furthermore, SMARTPLS 4 provides both the corrected R-squared coefficient and the R-squared (R²) value. Typically, the adjusted coefficient is favored over the unadjusted R-squared as it provides a more accurate evaluation of the explanatory capability of the independent variables. To illustrate, in this empirical investigation, the adjusted R-squared values for Green Purchase Intention, Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Private), and Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Public) were found to be 0.543, 0.537, and 0.446, respectively. Based on this data, environmental concern, minimalism, and collectivist culture explain 44.6% and 53.7% of the differences in pro-environmental behaviors in the public and private domains, respectively. Furthermore, the combination of both Public and Private Pro-Environmental Behaviours accounts for 54.3% of the variation in Green Purchase Intention.

Table 5.

R-square.

| |

R-square |

R-square adjusted |

| Green Purchase Intention |

0.545 |

0.543 |

| Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Private) |

0.540 |

0.537 |

| Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Public) |

0.450 |

0.446 |

| |

|

|

The f-square coefficient, which measures the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable, can be calculated using a formula created by Chin (1998). Lachenbruch and Cohen (1989) presented a method for computing f-square values to determine the significance of the effects of independent variables. The subsequent instructions are applicable: A number below 0.02 indicates an exceedingly modest or insignificant impact. An f-square value ranging from 0.02 to 0.15 signifies a small effect. A f-square score between 0.15 and 0.35 indicates a moderate effect. A f-square value of 0.35 or above indicates a substantial effect. All factor pairs in this investigation exhibit f-square coefficients that exceed 0.02. The f-square coefficient between Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Private) and Green Purchase Intention is remarkably strong, measuring 0.479. The substantial magnitude of this figure suggests that engaging in pro-environmental behaviours (private) has a noteworthy influence on the inclination to engage in green purchase intention.

Table 6.

f-square.

| |

Collectivist Culture |

Environmental Concern |

Green Purchase Intention |

Minimalism |

PEB (Private) |

PEB (Public) |

| Collectivist Culture |

|

|

|

|

0.224 |

0.060 |

| Environmental Concern |

|

|

|

|

0.222 |

0.198 |

| Green Purchase Intention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Minimalism |

|

|

|

|

0.076 |

0.110 |

| PEB (Private) |

|

|

0.479 |

|

|

|

| PEB (Public) |

|

|

0.044 |

|

|

|

The path coefficients’ standard errors-obtained via bootstrapping in SMARTPLS 4-are used to determine the route coefficients’ relevance in structural models. Finding t and p-values for each route coefficient is made easier using this strategy. By default, SMARTPLS 4 also uses the well recognised significance threshold of 5% (p = 0.05). A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates that a route coefficient is statistically significant. An absence of statistical significance is shown by a p-value larger than 0.05. P-values for the following components in this study: Environmental Concern, minimalism, green purchase intention, collectivist culture, and public and private pro-environmental behaviour. All of these values are below 0.05. Thus, these variables’ effects seem to be statistically significant. Also, every original sample coefficient is positive, indicating that connections in the model are positive directionalities: Environmental Concern (0.381), collectivist culture (0.363), and minimalism (0.203) had the highest and lowest effect on the Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Private) component, respectively. The impact on the Pro-Environmental Behaviours (Public) component is ranked as follows: Collectivst Culture (0.205), Environmental Concern (0.393), and Minimalism (0.267). Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Private) (0.607) had a higher effect on Green Purchase Intention than Pro-Environmental Behaviors (Public) (0.185).

Figure 2.

Effect coefficients and R square.

Figure 2.

Effect coefficients and R square.

Table 7.

Path coefficients.

Table 7.

Path coefficients.

| |

Original sample (O) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T statistics (|O/STDEV|) |

P values |

| Collectivist Culture -> PEB (Private) |

0.363 |

0.363 |

0.048 |

7.593 |

0.000 |

| Collectivist Culture -> PEB (Public) |

0.205 |

0.206 |

0.047 |

4.330 |

0.000 |

| Environmental Concern -> PEB (Private) |

0.381 |

0.378 |

0.045 |

8.506 |

0.000 |

| Environmental Concern -> PEB (Public) |

0.393 |

0.391 |

0.044 |

8.945 |

0.000 |

| Minimalism -> PEB (Private) |

0.203 |

0.203 |

0.036 |

5.590 |

0.000 |

| Minimalism -> PEB (Public) |

0.267 |

0.267 |

0.038 |

7.099 |

0.000 |

| PEB (Private) -> Green Purchase Intention |

0.607 |

0.606 |

0.050 |

12.215 |

0.000 |

| PEB (Public) -> Green Purchase Intention |

0.185 |

0.184 |

0.056 |

3.309 |

0.001 |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Prior studies have frequently neglected to look at developing countries, particularly when it comes to understanding how people in countries like Vietnam that have collectivist cultures and emerging economies see pro-environmental behaviours. Our work aims to address this deficiency by offering insightful information about these processes. Our research shows that engaging in pro-environmental behaviours plays a positive role in mediating role between minimalism and green purchase intention in collectivist cultures. These findings indicate that people who embrace minimalism in collectivist cultures are more inclined to take part in activities that benefit the environment. As a result, they are more likely to opt for eco-friendly products. The role of pro-environmental behaviours in mediating the relationship between environmental concern and green purchase intention in collectivist cultures are explored. A high interest in environmental concerns makes people more likely to do pro-environmental behaviours, which increases their green purchase intention.

The amount of literature already in existence is greatly increased by this research. Using pro-environmental behaviours as a lens, it first presents an alternate perspective on the desire to make green purchases. There have been studies on environmentally friendly conduct, but little emphasis has been placed on how minimalism influences these habits. Extensive and comprehensive. Gao et al. (2023) have conducted studies on the impact of minimalism on customers’ behaviour in adopting low-carbon innovation. Moreover, the study offers valuable understanding of how the notion of mastery is applied in the field of consumer behaviour, specifically in the context of green marketing. Consumer behaviour research has not given as much focus to the idea of mastery when compared to social and clinical psychology. This study builds upon the concepts of Public Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Private Pro-Environmental Behaviours, contributing to the existing body of research. Significant antecedents such as minimalism are also included, since they influence pro-environmental actions directly and the desire to buy environmentally friendly products indirectly. This enhancement deepens our understanding of the ways in which the mastery concept-which embodies a person’s feeling of competence and control-may influence the choices and behaviours of environmentally aware customers.

5.2. Managerial implications

Both public and private consumer pro-environmental actions have been shown to influence green buying intentions. Environmental concern, minimalism, and group culture are three areas where marketers may focus their efforts to encourage customers to be more environmentally conscious. Environmental Concern appears to be the most successful method of motivating pro-environmental behaviours in both the public and private sector. Instead of focusing solely on the benefits of buying green products, marketers should try to raise customer awareness of their environmental responsibilities. Their objective need to be to enlighten clients regarding the impact of their purchases on future generations, as well as the present condition of the environment. It is crucial to inform consumers that they have a responsibility not just to improve the environment but also to preserve an endangered ecosystem. This strategy facilitates a more significant and conscientious relationship between customers and their environmental impact.

Secondly, marketers need to inform customers about minimalism’s long-term benefits. Through this approach, they may convince consumers to change their purchase habits in favour of more environmental conservation. Highlighting the advantages of a minimalist lifestyle for the environment and the individual, such less clutter and a stronger focus on value items, might be useful in influencing consumer behavior in favor of more environmentally friendly habits.

Thirdly, the study’s results indicate that collective culture has a favourable influence on pro-environmental behaviours. People who are kind, helpful, reliant on one another, and sensitive of others’ needs are usually seen as “good” in collectivist cultures. In contrast, societies that emphasise individuality place a higher importance on character traits such as independence and decisiveness. Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan, Venezuela, Guatemala, Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil, and India are among the countries commonly associated with collectivist cultures.

Because collectivist societies have distinct traits, marketers should attempt to conjure up their essence in the minds of their target audience. By employing this strategy, they may convince customers to see the significance of collectivist ideas, hence impacting their pro-environmental behavior. Customers who come from collectivist cultures respond well to marketing methods that emphasize the importance of community welfare, mutual assistance, and collaborative efforts to protect the environment. This might potentially result in an increase in environmentally conscious behaviors and decisions.

Lastly, to ensure that local environmental efforts are in line with broader environmental policies, local communities and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) should set specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) targets. A comprehensive plan outlining the essential steps required to achieve these objectives is a crucial element. This entails the identification of crucial tasks, stakeholders, accessible resources, and any obstacles. By actively collaborating with stakeholders such as government agencies, business sector companies, and other NGOs, one may enhance the availability of resources and wield influence. Effective communication is crucial, encompassing campaigns, seminars, and educational initiatives to underscore the need of pro-environmental actions. Utilising various communication channels, such as social media, newspapers, radio, and community gatherings, can augment involvement. Consistent reporting on progress promotes openness and accountability. Community involvement may be encouraged by empowering local leaders, providing incentives, and involving community members in decision-making. Optimise resource allocation by providing adequate financing, comprehensive training, and enhancing capacity building. Implementing ongoing review, which involves establishing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and performing assessments, enables the adjustment of strategy. Sharing success stories can serve as a source of inspiration for others and establish a collection of exemplary methods for future initiatives.

6. Limitations and Futher of the Researchs

This study has several limitations, which open the path for further researchs. Demographic circumstances varies among districts, meaning that the present sample may not completely reflect the variety and subtleties across them. This needs care when applying the results to the full area of Vietnam or other places globally. Future cross-regions/countries studies is urged to identify possible differences. Identifying these discrepancies would emphasise the need of conducting comparative research and investigating environmental variables. Understanding the dependent roles of green development, the physical environment, and cultural norms in influencing green-product buying intentions would be much improved.

An area that focus for future research is the younger generation, namely those with little financial resources. This particular group is known for being extremely sensitive to pricing, which has a huge impact on their purchasing behaviours, including their acts that support the environment. Due to limited financial resources, young adults with low incomes tend to prioritise cost as the main element when making purchase decisions. Nevertheless, their responsiveness to cost does not automatically prevent individuals from participating in environmentally friendly actions. Indeed, their economic circumstances might occasionally compel individuals to adopt more sustainable behaviours, such as waste reduction and resource conservation, which are in line with both minimalism and environmental awareness. As a result, it is critical to investigate the role of price sensitivity in this demographic’s pro-environmental behaviour. The goal of research should be to understand the specific factors that motivate or impede people’s environmental activities, as well as how economic constraints influence these behaviours. Furthermore, examining how this specific group manages their financial constraints while adhering to their environmental principles may provide valuable insights for developing effective approaches to encouraging sustainable behaviours among young people with limited resources.

Author Contributions

Khanh Huy Nguyen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. Mai Dong Tran: Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City (UEH), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City (UEH).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City (UEH), Ho Chi Minh CITY, Vietnam.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmad, W., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 267, 122053. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H., Slade, E. L., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. Journal of Business Research, 122, 685–699. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S., & Tarun, M. T. (2020). Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: a mediating role of green trust. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(8), 1320–1336. [CrossRef]

- Arısal, B., & Atalar, T. (2016). The Exploring Relationships between Environmental Concern, Collectivism and Ecological Purchase Intention. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 514–521. [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I. (1988). Personality variables and environmental attitudes as predictors of ecologically responsible consumption patterns. Journal of Business Research, 17, 51-56.

- Bamberg, S. (2003). How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(1), 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2016). Positive and negative antecedents of purchasing eco-friendly products: A comparison between green and non-green consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 134, 229-247.

- Belaïd, F., & Massié, C. (2023). Driving forward a low-carbon built environment: The impact of energy context and environmental concerns on building renovation. Energy Economics, 124, 106865. [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, L., De Santis, A., Santesarti, F., & Tocca, L. (2016). An optimal plan for food consumption with minimal environmental impact: the case of school lunch menus. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 704–713. [CrossRef]

- Bülbül, H., Topal, A., Özoğlu, B., & Büyükkeklik, A. (2023). Assessment of determinants for households’ pro-environmental behaviours and direct emissions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 415, 137892. [CrossRef]

- Butt, A. (2017). Determinants of the Consumers Green Purchase Intention in Developing Countries. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 217–236. [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L. V., Escario, J. J., & Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. (2019). Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 149, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J., Testa, F., & Rizzi, F. (2018). The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. Journal of Cleaner Production, 175, 343–353. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R. Y. K. (2001). Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 18(4), 389–413. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. B., & Chai, L. T. (2010). Attitude towards the Environment and Green Products: Consumers’ Perspective. 4(2), 27-39. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., & Liu, J. (2023). When less is more: Understanding consumers’ responses to minimalist appeals. Psychology & Marketing, 40(10), 2151–2162. [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Cho, Y. N., Thyroff, A., Rapert, M. I., Park, S. Y., & Lee, H. J. (2013). To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1052–1059. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. F., Kotchen, M. J., & Moore, M. R. (2003). Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(3), 237–246. [CrossRef]

- Composto, J. W., Constantino, S. M., & Weber, E. U. (2023). Predictors and consequences of pro-environmental behavior at work. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 4, 100107. [CrossRef]

- Costantini, V., Crespi, F., Martini, C., & Pennacchio, L. (2015). Demand-pull and technology-push public support for eco-innovation: The case of the biofuels sector. Research Policy, 44(3), 577–595. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M., Li, Y., & Wang, S. (2024). Environmental Knowledge and Green Purchase Intention and Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Moral Obligation. Sustainability, 16(14), 6263. [CrossRef]

- Dagiliūtė, R. (2023). Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours? Sustainability, 15(20), 14773. [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F., Martinelli, E., & Endrighi, E. (2021). Enhancing consumers’ pro-environmental purchase intentions: the moderating role of environmental concern. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(9), 1312–1329. [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J. I. M., Steg, L., & Dicke, M. (2007). Morality and reducing car use: testing the norm activation model of prosocial behavior. Transportation Research Trends, NOVA Publishers, 2(1), 12-32.

- Delmas, M. A., & Lessem, N. (2014). Saving power to conserve your reputation? The effectiveness of private versus public information. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 67(3), 353–370. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M., Russo, M. V., & Montes-Sancho, M. J. (2007). Deregulation and environmental differentiation in the electric utility industry. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 189–209. [CrossRef]

- Druică, E., Ianole-Călin, R., & Puiu, A. I. (2023). When Less Is More: Understanding the Adoption of a Minimalist Lifestyle Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Mathematics, 11(3), 696. [CrossRef]

- Ek, K. (2005). Public and private attitudes towards “green” electricity: the case of Swedish wind power. Energy Policy, 33(13), 1677–1689. [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K., Pearce, J., Dowling, R., & Goh, E. (2022). Pro-environmental behaviours in protected areas: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 41, 100943. [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2017). Social Norms and Pro-environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecological Economics, 140, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Felix, R., Hinsch, C., Rauschnabel, P. A., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2018). Religiousness and environmental concern: A multilevel and multi-country analysis of the role of life satisfaction and indulgence. Journal of Business Research, 91, 304–312. [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E., & Martinez, E. (2007). Ecological consumer behaviour: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(1), 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N., & Gärling, T. (1999). Environmental concern: conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19(4), 369–382. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Tang, L., & Lyu, Y. (2023). Impact of minimalism on consumers’ low-carbon innovation behavior: Interactive role of quantitative behavior. Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment, 21(2), 82–91. [CrossRef]

- García-De-Frutos, N., Ortega-Egea, J. M., & Martínez-Del-Río, J. (2018). Anti-consumption for Environmental Sustainability: Conceptualization, Review, and Multilevel Research Directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 411–435. [CrossRef]

- García-Granero, E. M., Piedra-Muñoz, L., & Galdeano-Gómez, E. (2020). Measuring eco-innovation dimensions: The role of environmental corporate culture and commercial orientation. Research Policy, 49(8), 104028. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Black, B., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., & Krey, N. (2017). Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling in theJournal of Advertising: Review and Recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2015). Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management, 47, 164–177. [CrossRef]

- Hansla, A., Gamble, A., Juliusson, A., & Gärling, T. (2008). The relationships between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1254–1263. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Crespo, J., Coello-Pisco, S., Reyes-Venegas, H., Bermeo-Garay, M., Amaya, J., Soto, M., & Hidalgo-Crespo, A. (2022). Understanding citizens’ environmental concern and their pro-environmental behaviours and attitudes and their influence on energy use. Energy Reports, 8, 103–109. [CrossRef]

- Hock, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2010). Local strategic networks in the software industry: an empirical analysis of the value continuum. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 4(2), 132. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications.

- Howe, P. D., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J. R., & Leiserowitz, A. (2015). Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nature Climate Change, 5(6), 596–603. [CrossRef]

- Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2008). Toward a Model of Cross-Cultural Business Ethics: The Impact of Individualism and Collectivism on the Ethical Decision-Making Process. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 293–305. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N., & Wilson, J. (2016). I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 111, 349–359. [CrossRef]

- Irawan, N., Elia, A., & Benius, N. (2022). Interactive effects of citizen trust and cultural values on pro-environmental behaviors: A time-lag study from Indonesia. Heliyon, 8(3), e09139. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R., & Muncy, J. A. (2009). Purpose and object of anti-consumption. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 160–168. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J., & Dorrepaal, E. (2015). Personal Norms for Dealing with Climate Change: Results from a Survey Using Moral Foundations Theory. Sustainable Development, 23(6), 381–395. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H. (2018). Green Travel Behavior in Urban China: Influencing Factors and their Effects. Sustainable Development, 26(4), 350–364. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Ding, Z., & Liu, R. (2019). Can Chinese residential low-carbon consumption behavior intention be better explained? The role of cultural values. Natural Hazards, 95(1–2), 155–171. [CrossRef]

- Ju, N., & Hun Kim, S. (2022). Electric vehicle resistance from Korean and American millennials: Environmental concerns and perception. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 109, 103387. [CrossRef]

- Kaida, N., & Kaida, K. (2016). Pro-environmental behavior correlates with present and future subjective well-being. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(1), 111–127. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Martinez, C. M. J., & Johnson, C. (2021). Minimalism as a sustainable lifestyle: Its behavioral representations and contributions to emotional well-being. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 802–813. [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. (2017). Living both well and sustainably: a review of the literature, with some reflections on future research, interventions and policy. Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society. Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences/Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society. Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 375(2095), 20160369. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2011). Understanding Green Purchase: The Influence of Collectivism, Personal Values and Environmental Attitudes, and the Moderating Effect of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness. Seoul Journal of Business, 17(1), 65–92. [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C. A. (2013). A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1028-1038.

- Kong, X., & Jia, F. (2023). Intergenerational transmission of environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior: A dyadic relationship. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 89, 102058. [CrossRef]

- Kosic, A., Passafaro, P., & Molinari, M. (2024). Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Public Sphere: Comparing the Influence of Social Anxiety, Self-Efficacy, Global Warming Awareness and the NEP. Sustainability, 16(19), 8716. [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A., Tchetchik, A., Grinstein, A., Turgeman, L., & Blass, V. (2023). Promoting new pro-environmental behaviors: The effect of combining encouraging and discouraging messages. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 86, 101945. [CrossRef]

- Kropfeld, M. I., Nepomuceno, M. V., & Dantas, D. C. (2018). The Ecological Impact of Anticonsumption Lifestyles and Environmental Concern. Journal of Marketing & Public Policy, 074867661881044. [CrossRef]

- Kuanr, A., Pradhan, D., & Chaudhuri, H. R. (2019). I (do not) consume; therefore, I am: Investigating materialism and voluntary simplicity through a moderated mediation model. Psychology & Marketing, 37(2), 260–277. [CrossRef]

- Lachenbruch, P. A., & Cohen, J. (1989). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(408), 1096. [CrossRef]

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Larson, L. R., Stedman, R. C., Cooper, C. B., & Decker, D. J. (2015). Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 112–124. [CrossRef]

- Le, A. N. H., Tran, M. D., Nguyen, D. P., & Cheng, J. M. S. (2019). Heterogeneity in a dual personal values–dual purchase consequences–green consumption commitment framework. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(2), 480–498. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. K. (2017). A Comparative Study of Green Purchase Intention between Korean and Chinese Consumers: The Moderating Role of Collectivism. Sustainability, 9(10), 1930. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. K., Kim, S., Kim, M. S., & Choi, J. G. (2014). Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research, 67(10), 2097–2105. [CrossRef]

- Legere, A., & Kang, J. (2020). The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120699. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Zhao, L., Ma, S., Shao, S., & Zhang, L. (2019). What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 146, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Yang, D.; Meng, F.; Huang, Y. (2024). Environmental Regulations, Green Marketing, and Consumers’ Green Product Purchasing Intention: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 16, 8987. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. T., Zhu, D., Liu, C., & Kim, P. B. (2022). A meta-analysis of antecedents of pro-environmental behavioral intention of tourists and hospitality consumers. Tourism Management, 93, 104566. [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G., Liobikas, J., Brizga, J., & Juknys, R. (2020). Materialistic values impact on pro-environmental behavior: The case of transition country as Lithuania. Journal of Cleaner Production, 244, 118859. [CrossRef]

- Longhofer, W., Negro, G., & Roberts, P. W. (2019). The Changing Effectiveness of Local Civic Action: The Critical Nexus of Community and Organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64(1), 203–229. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Liu, X., Chen, H., Long, R., & Yue, T. (2017). Who contributed to “corporation green” in China? A view of public- and private-sphere pro-environmental behavior among employees. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 120, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Malik, F., & Ishaq, M. I. (2023). Impact of minimalist practices on consumer happiness and financial well-being. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103333. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Woodhead, A. (2022). Limited, considered and sustainable consumption: The (non)consumption practices of UK minimalists. Journal of Consumer Culture, 22(4), 1012–1031. [CrossRef]

- Matte, J., Fachinelli, A. C., De Toni, D., Milan, G. S., & Olea, P. M. (2021). Relationship between minimalism, happiness, life satisfaction, and experiential consumption. SN Social Sciences, 1(7). [CrossRef]

- Meissner, M. (2019). Against accumulation: lifestyle minimalism, de-growth and the present post-ecological condition. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12(3), 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Mi, L., Qiao, L., Xu, T., Gan, X., Yang, H., Zhao, J., Qiao, Y., & Hou, J. (2020). Promoting sustainable development: The impact of differences in cultural values on residents’ pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainable Development, 28(6), 1539–1553. [CrossRef]

- Mont, O. (2004). Institutionalisation of sustainable consumption patterns based on shared use. Ecological Economics, 50(1–2), 135–153. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M. M. (2007). A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the Egyptian consumer. Psychology & Marketing, 24(5), 445–473. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M. M. (2007). Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: the effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(3), 220–229. [CrossRef]

- Newton, J. D., Tsarenko, Y., Ferraro, C., & Sands, S. (2015). Environmental concern and environmental purchase intentions: The mediating role of learning strategy. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1974–1981. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N., Lobo, A., Nguyen, H. L., Phan, T. T. H., & Cao, T. K. (2016). Determinants influencing conservation behaviour: Perceptions of Vietnamese consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(6), 560–570. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N., Lobo, A., & Greenland, S. (2017). The influence of cultural values on green purchase behaviour. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(3), 377–396. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook, 97-146.

- Pandey, M., & Yadav, P. S. (2023). Understanding the role of individual concerns, attitude, and perceived value in green apparel purchase intention; the mediating effect of consumer involvement and moderating role of generation Z&Y. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 9, 100120. [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, A., Shukla, P., & Taylor, C. R. R. (2021). Minimalism in consumption: A typology and brand engagement strategies. Journal of Business Research, 127, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M., Kilbourne, W., & Vocino, A. (2014). Relationship between the dominant social paradigm, materialism and environmental behaviours in four Asian economies. European Journal of Marketing, 48(3/4), 522–551. [CrossRef]

- Rahimah, A., Khalil, S., Cheng, J. M., Tran, M. D., & Panwar, V. (2018). Understanding green purchase behavior through death anxiety and individual social responsibility: Mastery as a moderator. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(5), 477–490. [CrossRef]

- Rhead, R., Elliot, M., & Upham, P. (2015). Assessing the structure of UK environmental concern and its association with pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 175–183. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, W., Gul, S., & Lee, Y. (2023). The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities. Sustainability, 15(5), 4490. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A., & Bacon, D. R. (1997). Exploring the Subtle Relationships between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior. Journal of Business Research, 40(1), 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative Influences on Altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 221–279. [CrossRef]

- Segev, S. (2015). Modelling household conservation behaviour among ethnic consumers: the path from values to behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(3), 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, N., & Balakrishnan, J. (2023). Influence of pro-environmental behaviour towards behavioural intention of electric vehicles. Technological Forecasting & Social Change/ Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 187, 122206. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G., Xie, F., Gong, S., & Pan, H. (2019). The role of cultural values in green purchasing intention: Empirical evidence from Chinese consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(3), 315–326. [CrossRef]

- Sine, W. D., & Lee, B. H. (2009). Tilting at Windmills? The Environmental Movement and the Emergence of the U.S. Wind Energy Sector. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(1), 123–155. [CrossRef]

- Sova, A., Rožman, M., & Vide, R. K. (2024). Exploring Differences in Green Innovation among Countries with Individualistic and Collectivist Cultural Orientations. Sustainability, 16(17), 7685. [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N., Purbey, S., & Sadarangani, P. (2018). Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41, 177–189. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C., Dietz, T., Abel, T.D., Guagnano, G.A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6, 81-97.

- Tam, K. P., & Chan, H. W. (2017). Environmental concern has a weaker association with pro-environmental behavior in some societies than others: A cross-cultural psychology perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 53, 213–223. [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. P., & Chan, H. W. (2018). Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Global Environmental Change, 48, 182–194. [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. (2009). The Motivational Roots of Norms for Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31(4), 348–362. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werff, E., Steg, L., & Keizer, K. (2013). It is a moral issue: The relationship between environmental self-identity, obligation-based intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behaviour. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1258–1265. [CrossRef]

- Varshneya, G., Pandey, S. K., & Das, G. (2017). Impact of Social Influence and Green Consumption Values on Purchase Intention of Organic Clothing: A Study on Collectivist Developing Economy. Global Business Review, 18(2), 478–492. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. T. (2014). Consumer characteristics and social influence factors on green purchasing intentions. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(7), 738–753. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Sun, Q., Wang, B., & Zhang, B. (2019). Purchasing intentions of Chinese consumers on energy-efficient appliances: Is the energy efficiency label effective? Journal of Cleaner Production, 238, 117896. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S., Ang, T., & Jancenelle, V. E. (2018). Willingness to pay more for green products: The interplay of consumer characteristics and customer participation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 45, 230–238. [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. (2009). Behavioural responses to climate change: Asymmetry of intentions and impacts. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(1), 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Wichman, C. J. (2016). Incentives, green preferences, and private provision of impure public goods. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 79, 208–220. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. V., & Bellezza, S. (2022). Consumer Minimalism. Journal of Consumer Research, 48(5), 796–816. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 732–739. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, Taro. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd Edition, New York: Harper and Row.

- Yin, J., & Shi, S. (2019). Analysis of the mediating role of social network embeddedness on low-carbon household behaviour: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 234, 858–866. [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Ismail, N., Ahrari, S., & Samah, A. A. (2021). The effects of consumer attitude on green purchase intention: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Business Research, 132, 732–743. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhou, G. (2013). Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy, 62, 1120–1127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhou, G. (2014). Determinants of employee electricity saving: the role of social benefits, personal benefits and organizational electricity saving climate. Journal of Cleaner Production, 66, 280–287. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M. R., Stafford, T. F., & Stafford, M. R. (1994). Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 30(1), 63–74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).