Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

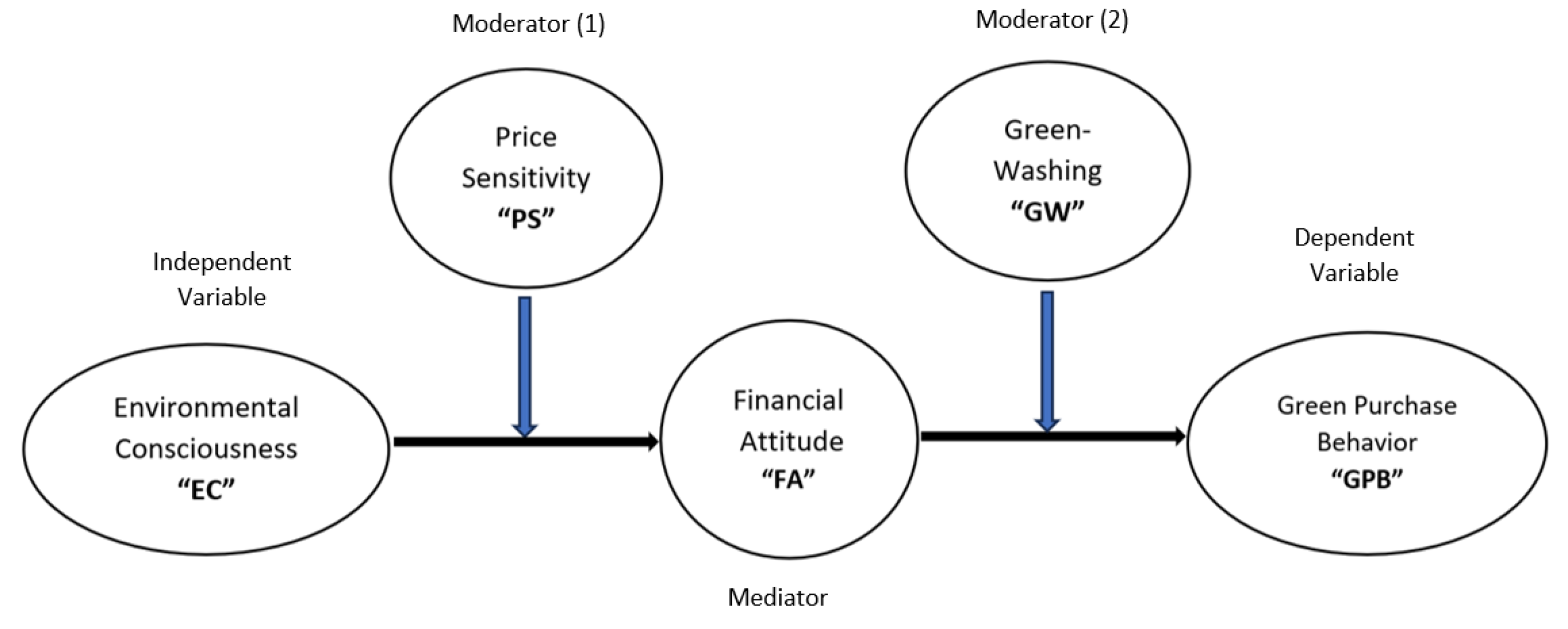

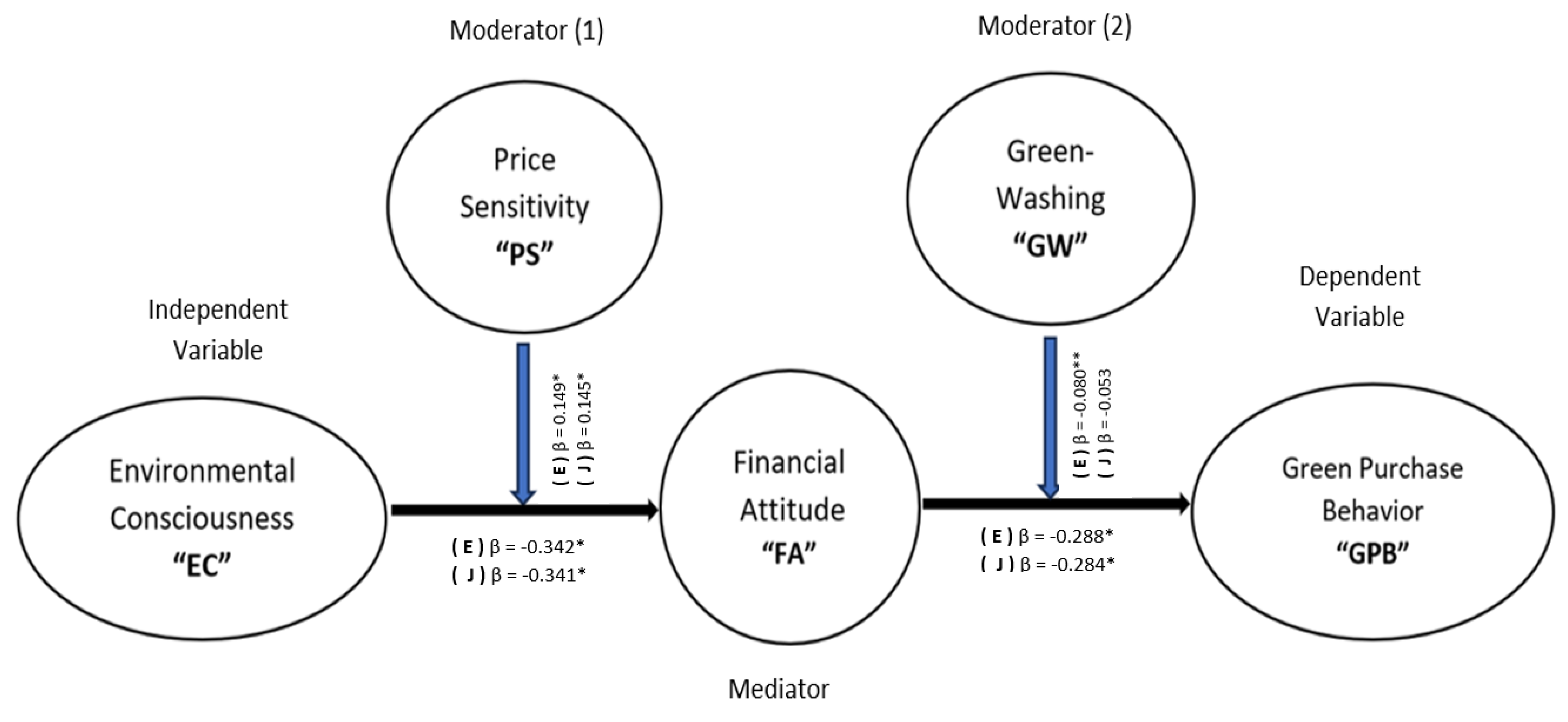

2.1. The Environmental Consciousness and Green Purchase Behaviour: Mediating Role of Financial Attitude

2.2. Moderating effects of Price Sensitivity

2.3. Moderating effects of Greenwashing

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Sample and procedures

3.3. Research instrument

3.4. Pre Test and Pilot study

- Price Sensitivity (PS) showed strong agreement, with PS1 in Jordan loading at 0.932 and PS3 in Egypt at 0.951;

- Greenwashing demonstrated stronger loadings in Egypt, particularly GW1 (0.914) compared to Jordan’s GW1 (0.790);

- Financial Attitude (FA), Egypt’s FA1 reached 0.931, slightly higher than Jordan’s FA1 (0.906), while Jordan displayed more consistent item loadings, such as FA3;

- Green Purchase Behaviour items loaded highly in both contexts, with Jordan’s GPB3 achieving a loading of 0.873;

- Environmental Consciousness was comparable between countries, with Egypt’s EC4 at 0.866 and Jordan’s EC5 at 0.840;

3.5. Main study

3.5.1. Non-response Bias and Common Method Bias

3.5.2. Hypothesis testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Research Findings

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Practical Contributions

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, S.-W.; Chiang, P.-Y. Exploring the Mediating Effects of the Theory of Planned Behavior on the Relationships between Environmental Awareness, Green Advocacy, and Green Self-Efficacy on the Green Word-of-Mouth Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. Journal of business ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, B. Impact of greenwashing perception on consumers’ green purchasing intentions: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarky, S.; Elgamal, S.; Hamdi, R.; Barakat, M.R. Green supply chain: the impact of environmental knowledge on green purchasing intention. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S. Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egyptian journal of petroleum 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human ecology review 1999, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; El-Manstrly, D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Ramayah, T. Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 262, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Organic green purchasing: Moderation of environmental protection emotion and price sensitivity. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 368, 133113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabees, A.; Lisec, A.; Elbarky, S.; Barakat, M. The role of organizational performance in sustaining competitive advantage through reverse logistics activities. Business Process Management Journal 2024, 30, 2025–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. Journal of Business Research 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, M.H.; Tariq, B.; Azhar, S.; Ahmed, K.; Khuwaja, F.M.; Han, H. Predicting consumer purchase intention toward hybrid vehicles: testing the moderating role of price sensitivity. European Business Review 2022, 34, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Pang, X. Investigation into the factors affecting the green consumption behavior of China rural residents in the context of dual carbon. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, F.; Adhikari, A. Antecedents affecting consumers’ green purchase intention towards green products. American Journal of Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation 2023, 1, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; El-Rouby, H.S.; El-Gamal, S.Y.; Zaghloul, A.S. The Tendency Toward Producing Ecologically Friendly Products at Toshiba in the Middle East. In Cases on International Business Logistics in the Middle East. In Cases on International Business Logistics in the Middle East, Abdelbary, I., Haddad, S., Elkady, G., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Cam, L.N.T. A rising trend in eco-friendly products: A health-conscious approach to green buying. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Tong, X. Factors influencing college students’ purchase intention towards Bamboo textile and apparel products. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 2016, 9, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laheri, V.K.; Lim, W.M.; Arya, P.K.; Kumar, S. A multidimensional lens of environmental consciousness: towards an environmentally conscious theory of planned behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2024, 41, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahma, B.; Kramberger, T.; Barakat, M.; Ali, A.H. Investigating customers’ purchase intentions for electric vehicles with linkage of theory of reasoned action and self-image congruence. Business Process Management Journal 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.K.; Teo, T.S. Sex, money and financial hardship: An empirical study of attitudes towards money among undergraduates in Singapore. journal of Economic Psychology 1997, 18, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanji, H.; Sarin, V. Relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchase behaviour among youth. International Journal of Green Economics 2018, 12, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.M.; Barky, S.S.S.E.; Barakat, M.R. Exploring Egyptian Consumers’ Drive for Sustainable Purchases through Financial Empowerment and Environmental Awareness: The Moderating Role of Demographic Characteristics. Journal of Sustainability Research 2025, 7, e250011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AKBAR, N.; GHUTAI, G.; YOUSAFZAI, M.T.; AHMAD, S. Pricing the Green Path: Unveiling the role of Price Sensitivity as a Moderator in Environmental Attitude and Green Purchase Intentions. International Review of Management and Business Research 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Guath, M.; Stikvoort, B.; Juslin, P. Nudging for eco-friendly online shopping–Attraction effect curbs price sensitivity. Journal of environmental psychology 2022, 81, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu, V.M.H.; Mat, N.K.N. Predictors of green purchase intention in Nigeria: The mediating role of environmental consciousness. American journal of economics 2015, 5, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, M.; Ali, A.; Madkour, T.; Eid, A. Enhancing operational performance through supply chain integration: the mediating role of resilience capabilities under COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.-I.; Ioanid, A. Factors influencing consumer behavior toward green products: A systematic literature review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.A.; Kramberger, T.; Barakat, M.; Ali, A.H. Barriers to Applying Last-Mile Logistics in the Egyptian Market: An Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabieh, S. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, Green perceived risk, and green trust. Management Science Letters 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Kassinis, G.; Papagiannakis, G. The impact of perceived greenwashing on customer satisfaction and the contingent role of capability reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 2023, 185, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, P.; Tare, H. Green marketing and corporate social responsibility: A review of business practices. Multidisciplinary Reviews 2024, 7, 2024059–2024059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.; Obrecht, M.; Ali, A.H.; Barakat, M. Does environmental knowledge and performance engender environmental behavior at airports? A moderated mediation effect. Business Process Management Journal 2024, 30, 671–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.; Salah, M.; Barakat, M.; Obrecht, M. Airport Sustainability Awareness: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishal, A.; Dubey, R.; Gupta, O.K.; Luo, Z. Dynamics of environmental consciousness and green purchase behaviour: an empirical study. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2017, 9, 682–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N.; Ishaq, M.I.; Raza, A. How anticipated pride and guilt influence green consumption in the Middle East: The moderating role of environmental consciousness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 68, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Arshad, A.; Anwar ul Haq, M.; Akram, B. Role of environmentalism in the development of green purchase intentions: a moderating role of green product knowledge. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2020, 15, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, I.; Serra, P.; Iskander, J.; Gamboa-Zamora, S.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Knez, M. Is the inland waterways system primed for mitigating road transport in Egypt? International Business Logistics 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment, J.M.o. Waste Sector Green Growth National Action Plan 2021-2025; the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Amman: 2020.

- Azab, S.; Rabie, A.E.; Hafez, F.; Mostafa, A.H.; El Rayes, A.H.; Awad, M.M. Decent Life Initiative and Sustainable Development Goals: A systems thinking approach. Systems 2023, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, N. Financing Sustainable Development in Egypt Report; 2022.

- organization, L.I. The Green Economy in Jordan: Sustainability Leading the Way for Growth. Available online: https://leadersinternational.org/results-insights/the-green-economy-in-jordan-sustainability-leading-the-way-for-growth/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 7/5/2025).

- Lis, A.M.; Rozkwitalska, M. Technological capability dynamics through cluster organizations. Baltic Journal of Management 2020, 15, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of business research methods; Routledge: 2019.

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. International journal of market research 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisschoff, C.; Liebenberg, P. Identifying factors that influence green purchasing behavior in South Africa. Society for Marketing Advances 2016, 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.S.; Kar, S.K.; Rai, P.K. Why do consumers buy recycled shoes? An amalgamation of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behaviour. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 1007959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturan, U. How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention? An empirical research. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2018, 36, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, D.M.; Bearden, W.O. The use of expert judges in scale development: Implications for improving face validity of measures of unobservable constructs. Journal of business research 2004, 57, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling; Guilford publications: 2023.

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological methods 1996, 1, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language; Scientific software international: 1993.

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological bulletin 1990, 107, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook; Springer Nature: 2021.

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Heck, A. Multivariate data analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012; Volume 131.

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series). New York: Taylor & Francis Group 2010, 396, 7384. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook 1978, 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Huo, B. The impact of green supply chain integration on sustainable performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2020, 120, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Merchant, H. A causal analysis of the role of institutions and organizational proficiencies on the innovation capability of Chinese SMEs. International Business Review 2020, 29, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of retailing and consumer services 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egypt-Today. Egypt targets green investments to 50% of public spending in 24/25 economic, social development plan. Available online: https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/3/137364/Egypt-targets-green-investments-to-50-of-public-spending-in?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- CSREGYPT. Available online: https://www.csregypt.com/en/idsc-report-egypts-public-private-investments-in-plastic-recycling-hit-egp-1-2bn-in-2022-2023/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- State-Information-Service. Ministry of Environment: LE 250M investment to launch advanced waste recycling plant in Assiut. Available online: https://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/202578/Ministry-of-Environment-LE-250M-investment-to-launch-advanced-waste-recycling-plant-in-Assiut?utm_source=chatgpt.

| Egypt (n=828) | Jordan (n=776) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Specifications | Frequency | Percentage | Specifications | Frequency | Percentage |

| City | Cairo Alexandria Giza Other |

292 252 215 69 |

35.3 30.4 26 8.3 |

Amman Zarqa Irbid Other |

298 226 199 53 |

38.4 29.1 25.6 6.8 |

| Gender | Male Female |

440 388 |

53.1 46.9 |

Male Female |

428 348 |

55.2 44.8 |

| Age | 18-29 30-40 41-50 |

318 333 177 |

38.4 40.2 21.4 |

18-29 30-40 41-50 |

292 333 151 |

37.6 42.9 19.5 |

| Education | Undergraduate Graduated Postgraduate |

169 566 93 |

20.4 68.4 11.2 |

Undergraduate Graduated Postgraduate |

143 555 78 |

18.4 71.5 10.1 |

| Construct | Code | Measurements | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Consciousness | EC1 | I can do a lot to protect the environment in my community. | [49] |

| EC2 | I am willing to pay more environmental taxes to protect the environment. | ||

| EC3 | I think the government should reallocate existing money to protect the environment. | ||

| EC4 | I am very concerned about environmental issues in my community. | ||

| EC5 | I will make personal sacrifices if I could help protect the environment. | ||

| Green Purchase Behaviour | GPB1 | I try to buy green products. | [1] |

| GPB2 | I’ve turned to buying green products because of the benefits of environmental conservation. | ||

| GPB3 | When deciding between identical products, I choose the one that presents to have lower environmental impact. | ||

| GPB4 | Even though green products are somewhat more expensive than non-green ones, I prefer to buy green products. | ||

| Financial Attitude | FA1 | I check prices for every product I purchase. | [1,50] |

| FA2 | I notice when products I regularly buy change prices or are discounted. | ||

| FA3 | I compare prices between similar products to get the best value for money. | ||

| Price Sensitivity | PS1 | For me, it is acceptable to pay more for green products than for non-green products. | [13] |

| PS2 | I am willing to pay more for green products than for non-green products. | ||

| PS3 | I can afford to spend extra money to buy green products. | ||

| Greenwashing | GW1 | I can recognise that the product is clearly misleading regarding its environmental features. | [51] |

| GW2 | Products that display misleading environmental imagery or “green labels” can be easily recognised. | ||

| GW3 | I am able to identify that the product makes a confusing or subjective claim about being green. | ||

| GW4 | It is clear that the product exaggerates how green it is. | ||

| GW5 | It’s evident that the product leaves out or hides essential information in order to exaggerate its green claims. |

| Country | Study Type | Distributed | Collected | Incomplete | Valid Responses | Response Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Pilot | 280 | 262 | 8 | 254 | 90.71 |

| Main | 922 | 865 | 27 | 828 | 89.80 | |

| Jordan | Pilot | 250 | 231 | 4 | 227 | 90.80 |

| Main | 847 | 820 | 44 | 776 | 91.62 |

| Construct | Item | Egypt | Jordan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | ||

| Price Sensitivity | PS1 | 0.867 | 0.887 | 0.725 | 0.932 | 0.887 | 0.726 |

| PS2 | 0.721 | 0.710 | |||||

| PS3 | 0.951 | 0.897 | |||||

| Greenwashing | GW1 | 0.914 | 0.875 | 0.587 | 0.790 | 0.859 | 0.551 |

| GW2 | 0.713 | 0.775 | |||||

| GW3 | 0.788 | 0.762 | |||||

| GW4 | 0.610 | 0.651 | |||||

| GW5 | 0.775 | 0.726 | |||||

| Financial Attitude | FA1 | 0.931 | 0.889 | 0.73 | 0.906 | 0.869 | 0.690 |

| FA2 | 0.923 | 0.866 | |||||

| FA3 | 0.687 | 0.707 | |||||

| Green Purchase Behaviour | GPB1 | 0.766 | 0.88 | 0.648 | 0.792 | 0.895 | 0.682 |

| GPB2 | 0.890 | 0.854 | |||||

| GPB3 | 0.749 | 0.873 | |||||

| GPB4 | 0.807 | 0.780 | |||||

| Environmental Consciousness | EC1 | 0.674 | 0.899 | 0.641 | 0.686 | 0.889 | 0.616 |

| EC2 | 0.841 | 0.773 | |||||

| EC3 | 0.751 | 0.782 | |||||

| EC4 | 0.866 | 0.833 | |||||

| EC5 | 0.855 | 0.840 | |||||

| Construct | Item | Egypt | Jordan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | ||

| Price Sensitivity | PS1 | 0.867 | 0.881 | 0.712 | 0.874 | 0.878 | 0.708 |

| PS2 | 0.779 | 0.773 | |||||

| PS3 | 0.882 | 0.873 | |||||

| Greenwashing | GW1 | 0.848 | 0.888 | 0.615 | 0.841 | 0.889 | 0.617 |

| GW2 | 0.793 | 0.795 | |||||

| GW3 | 0.769 | 0.762 | |||||

| GW4 | 0.688 | 0.694 | |||||

| GW5 | 0.813 | 0.827 | |||||

| Financial Attitude | FA1 | 0.911 | 0.897 | 0.746 | 0.911 | 0.898 | 0.747 |

| FA2 | 0.890 | 0.889 | |||||

| FA3 | 0.784 | 0.787 | |||||

| Green Purchase Behaviour | GPB1 | 0.784 | 0.896 | 0.683 | 0.781 | 0.895 | 0.682 |

| GPB2 | 0.850 | 0.85 | |||||

| GPB3 | 0.818 | 0.816 | |||||

| GPB4 | 0.853 | 0.854 | |||||

| Environmental Consciousness | EC1 | 0.712 | 0.893 | 0.625 | 0.712 | 0.893 | 0.627 |

| EC2 | 0.809 | 0.811 | |||||

| EC3 | 0.780 | 0.776 | |||||

| EC4 | 0.806 | 0.808 | |||||

| EC5 | 0.840 | 0.846 | |||||

| Egypt Main Study | Jordan Main Study | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | GW | FA | EC | GPB | PS | GW | FA | EC | GPB | ||

| PS | (0.790) | (0.791) | |||||||||

| GW | 0.027 | (0.863) | 0.022 | (0.864) | |||||||

| FA | 0.126 | -0.060 | (0.784) | 0.115 | -0.065 | (0.785) | |||||

| EC | 0.119 | 0.062 | -0.314 | (0.843) | 0.124 | 0.088 | -0.310 | (0.841) | |||

| GPB | -0.303 | 0.006 | -0.258 | 0.172 | (0.826) | -0.310 | 0.023 | -0.253 | 0.157 | (0.825) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).