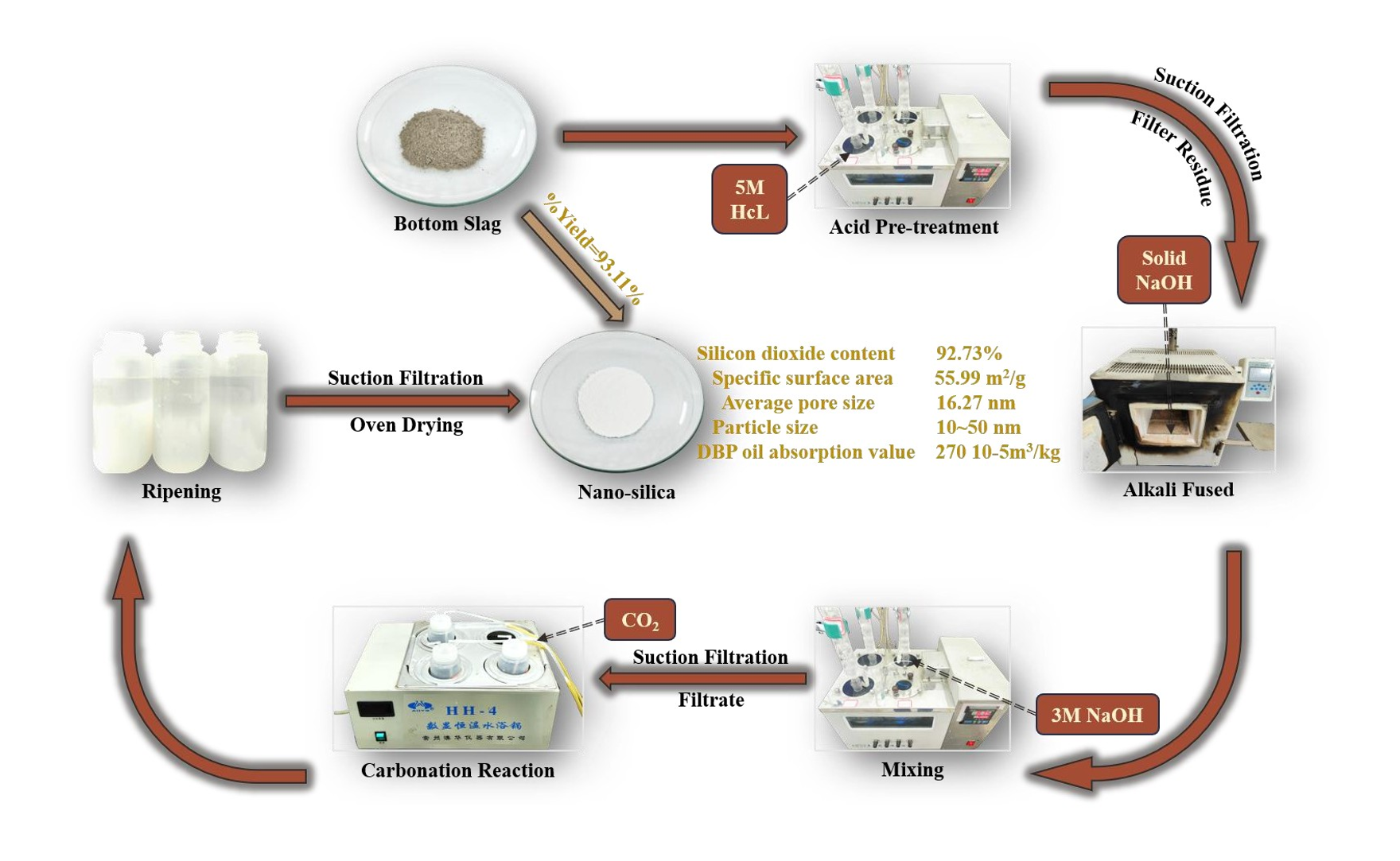

3.1. Effects of Acid Pretreatment

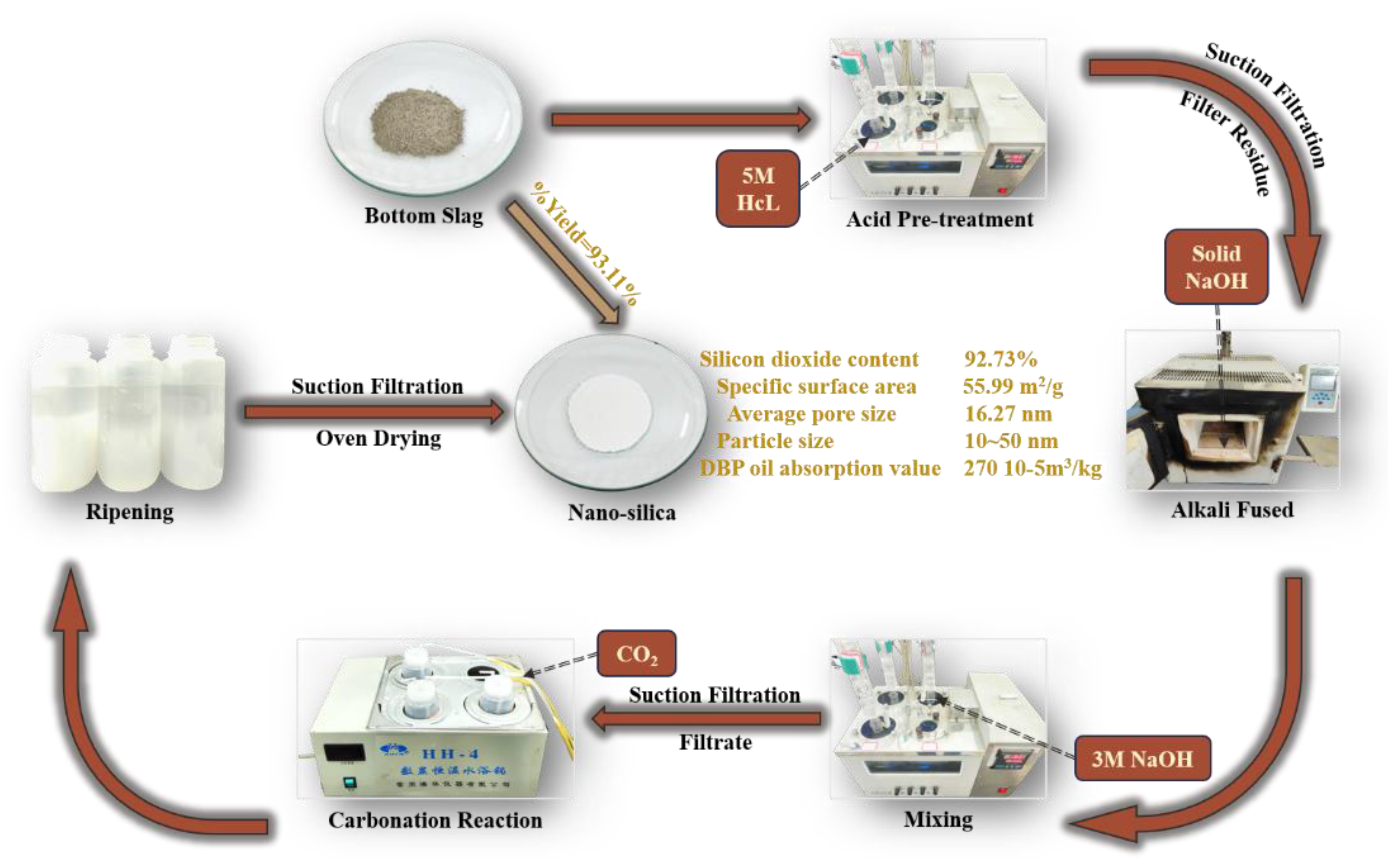

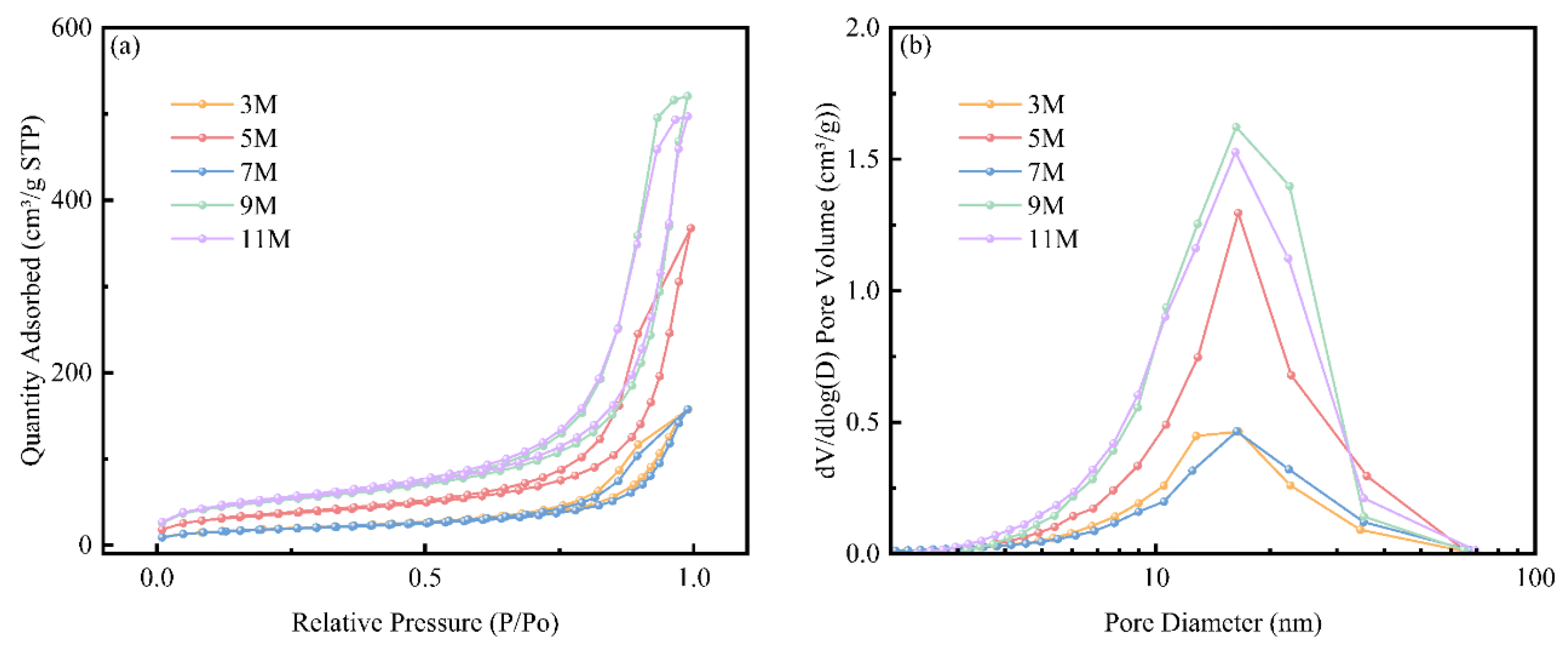

The effects of different acid concentrations on the final product were illustrated in

Figure 2. It could be observed from

Figure 2 that as the concentration of hydrochloric acid increased, both the extraction yield and purity of nano-silica initially increased, then decreased, and subsequently increased again, with the first peak occurring at a concentration of 5 M. This trend aligned with the findings of Teymouri et al. [

22]. At a hydrochloric acid concentration of 1 M, the extraction yield was relatively low, and the purity was only 53.2%. As the concentration of hydrochloric acid increased, when it reached 5 M, the extraction yield significantly increased to 61.1%, and the purity also substantially improved to 86.92%. This was because, in the initial stages of concentration increase, hydrochloric acid significantly dissolved other oxides in the bottom slag, effectively removing the other oxides that encapsulated the silica and thereby significantly increasing the reactive surface area of the silica. However, when the hydrochloric acid concentration increased further to 7 M, both the extraction yield and purity decreased to 52.66% and 70.32%, respectively. This was attributed to the high concentration hydrochloric acid beginning to react directly with silica, leading to its dissolution in the solution, which was then removed in the subsequent filtration step, thus lowering the extraction yield. Furthermore, excessive reaction of hydrochloric acid may have triggered a series of side reactions, such as the reaction between the acid and metal oxides like calcium, magnesium, and aluminum present in the residue, resulting in the formation of insoluble by-products. This reduced the proportion of silica in the final product, thereby decreasing its purity. As the concentration was further increased to 9 M, the purity reached its maximum value of 94.38%, while at 11 M, the extraction yield reached its peak of 66.71%. Due to the acid concentration reaching a higher level, it provided enhanced dissolving and complexing abilities, consistent with the findings of Steven et al. [

23]. Extremely concentrated hydrochloric acid could dissolve silicates that were previously difficult to process or disrupt the formation of silica gel, thereby increasing the purity and extraction yield of SiO

2.

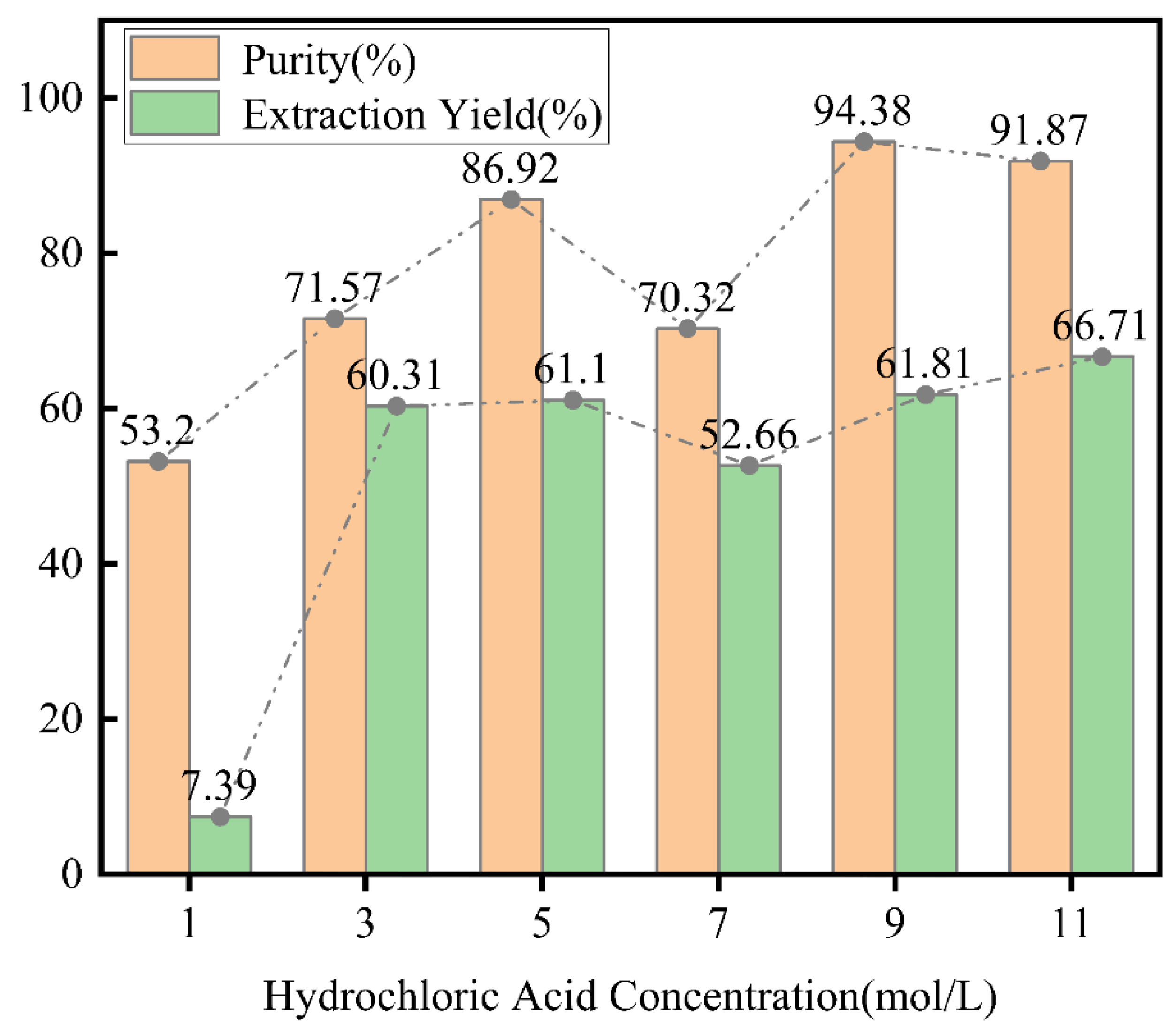

The BET test results of nano-silica extracted after treatment with different acid concentrations were shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3(a) showed the nitrogen adsorption isotherms of nano-silica extracted after treatment with different acid concentrations. All curves displayed clear Type II nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms, with an H3-type mesoporous hysteresis loop appearing at P/P0 = 0.8-1.0. This was attributed to capillary condensation of nitrogen in the interstitial pores of mesoporous silica particles [

24]. This result indicated the presence of a distinct adsorption saturation plateau on the isotherms, reflecting a uniform pore size distribution in the nano-silica samples, which was consistent with the pore size distribution shown in

Figure 3(b) for different concentrations of hydrochloric acid treatment. Typically, in the absence of surfactants, the pore size distribution of nano-silica ranged from 2 to 100 nm [

19]. In this study, the pore size distribution obtained from 3 M to 11 M acid treatment was within the range of 2 to 100 nm. As the concentration of hydrochloric acid increased, the pore size distribution remained relatively unchanged, while the pore volume showed an increasing trend.

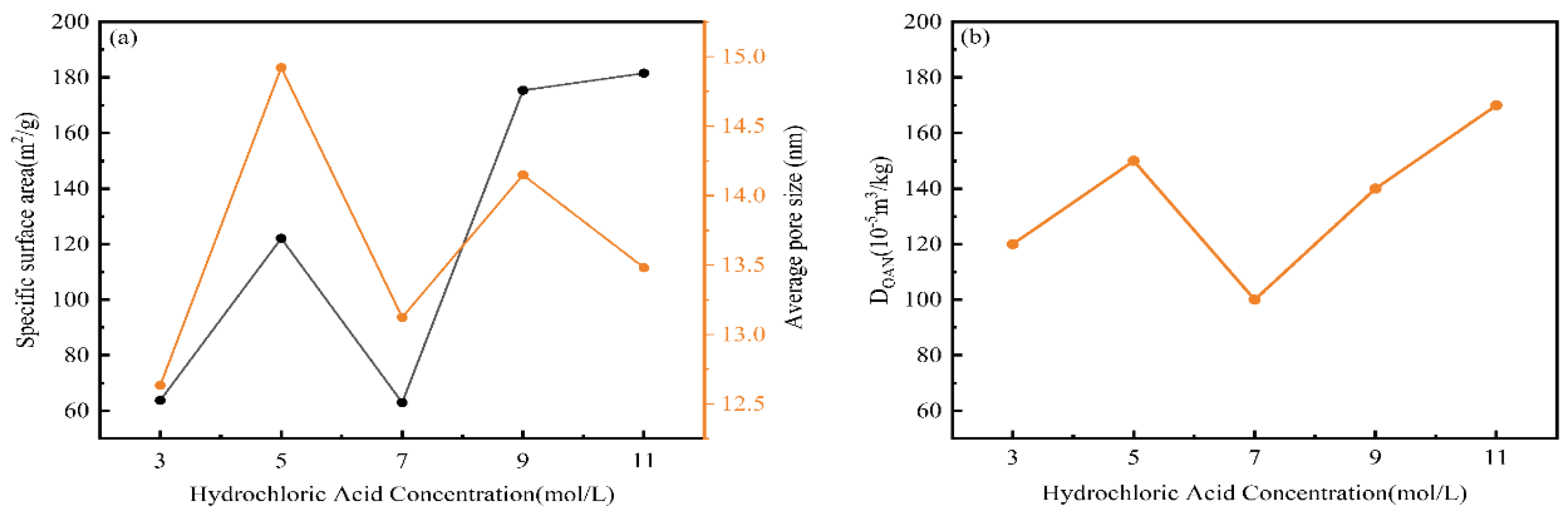

The changes in specific surface area, average pore size, and oil absorption values of nano-silica extracted after treatment with different acid concentrations were shown in

Figure 4. Figures 4(a) and (b) indicated that as the concentration of hydrochloric acid pretreatment increased, the trends in oil absorption value, specific surface area, and average pore size corresponded to the changes in extraction yield, purity, and pore volume. These values increased up to 5 M, then decreased before increasing again. This was because the obtained silica consisted of fine and uniform nano-silica particles with small diameters, which had a large specific surface area. Hydrochloric acid effectively removed other impurities from the residual ash, leading to higher-purity silica with a looser structure, further increasing its specific surface area and average pore size. Additionally, the oil absorption value was positively correlated with the average pore size. This was because larger pore sizes and pore volumes could accommodate more oil, leading to higher oil absorption values. Therefore, the trend in the oil absorption curve aligned with the trend in the average pore size curve, which was consistent with previous studies [

25]. In conclusion, acid treatment could improve the purity and extraction efficiency of nano-silica and enhance its specific surface area, average pore size, oil absorption value, and other physicochemical properties.

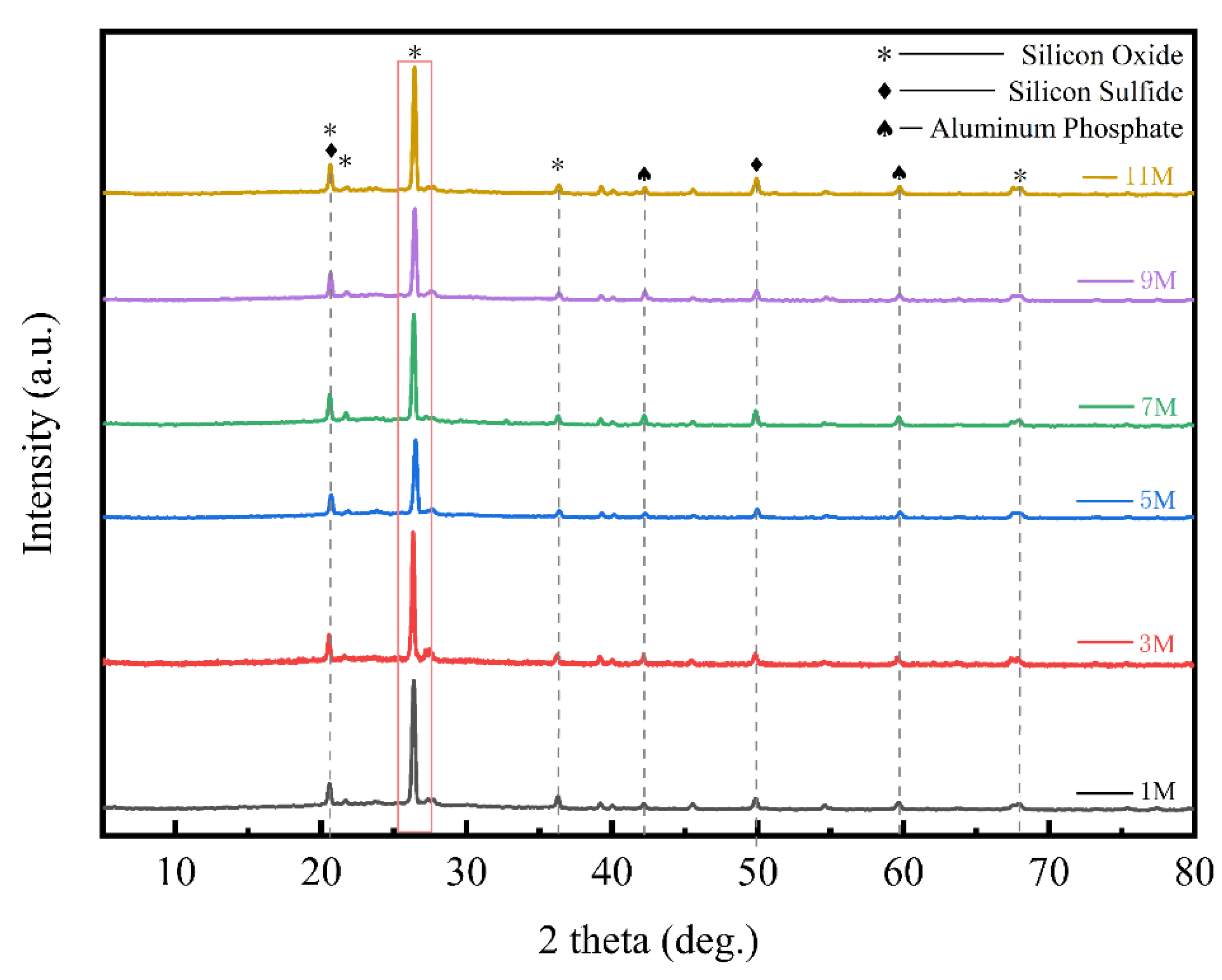

To determine the optimal acid concentration for the pretreatment step, this study further investigated the effects of different acid concentrations on the physicochemical properties of the ash. To characterize the changes in the crystalline form and degree of crystallization of silica in the residual ash after pretreatment with varying concentrations of hydrochloric acid, XRD diffraction experiments were conducted on the BS treated with different concentrations of hydrochloric acid. The experimental results were shown in

Figure 5. Multiple distinct peaks appeared between diffraction angles of 20° and 70°, representing primarily silica, silicon sulfide, and aluminum phosphate. The main peak was located at a diffraction angle of 27°, and the high, narrow peak indicated a high degree of crystallinity in the silica at this location. It was noteworthy that although different concentrations of hydrochloric acid treatment did not significantly affect the types of substances present, the peak height of the main peak representing silica at a diffraction angle of 27° showed a clear decreasing trend with increasing acid concentration. This directly reflected a significant reduction in crystallinity, as the crystal structure of minerals was disrupted during hydrochloric acid treatment, leading to a disordering of the originally ordered crystal structures, which in turn reduced the crystallinity of the silica. This phenomenon was most pronounced in the XRD diffraction pattern of the BS treated with 5 M hydrochloric acid. The decrease in crystallinity suggested that the silica in the BS became easier to extract during subsequent processing, indicating that the activity of the silica in the BS was significantly enhanced after acid pretreatment, facilitating an increase in extraction efficiency.

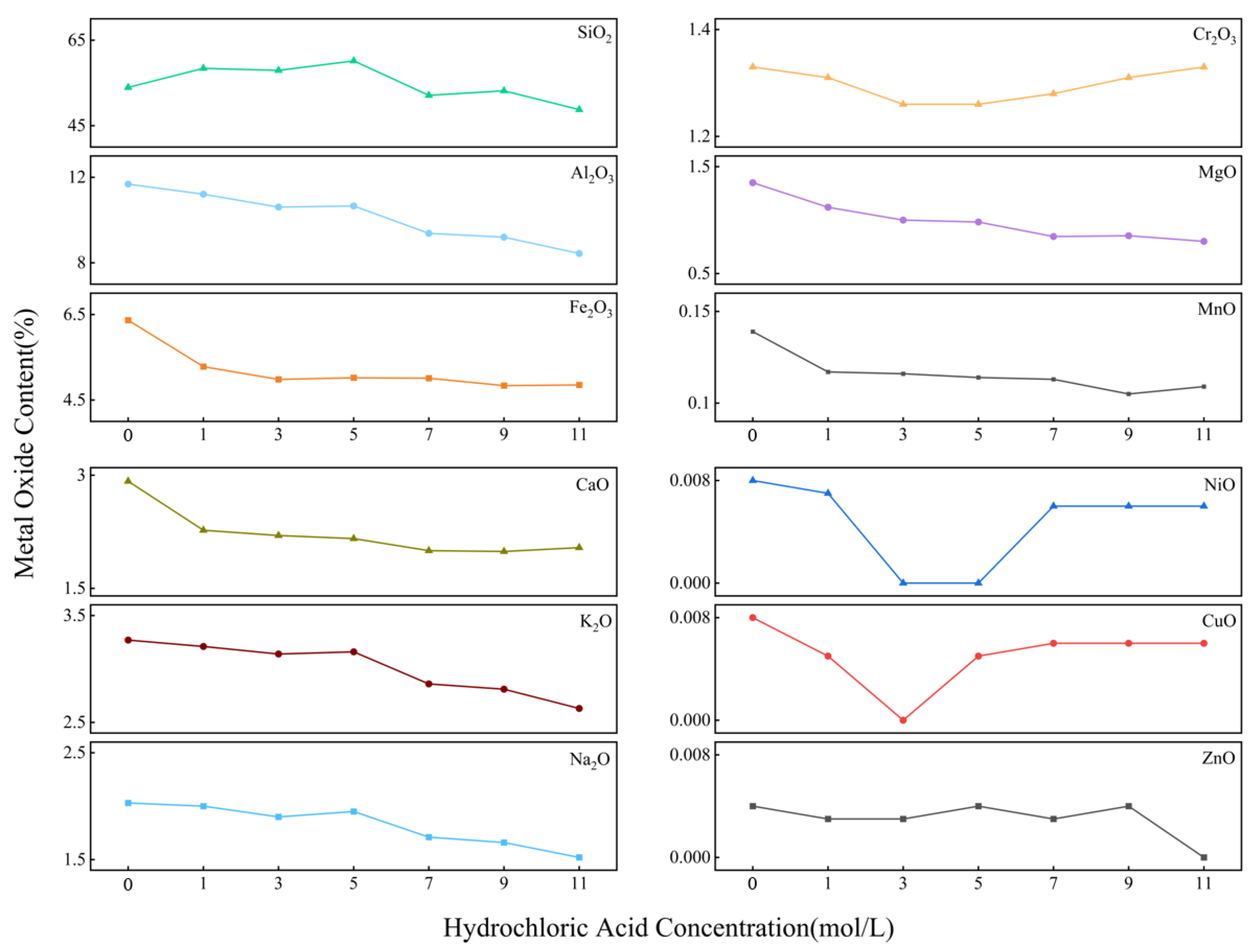

To characterize the changes in the main ash components and heavy metal content in the ash after treatment with different acid concentrations, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy was performed on the ash before and after acid treatment. The experimental results were shown in

Figure 6. The content of major oxides such as Al

2O

3, Fe

2O

3, CaO, K

2O, and Na

2O decreased significantly after acid washing, with the decrease becoming more pronounced as acid concentration increased. The concentrations of major heavy metals such as Cr, Mg, Mn, Ni, Cu, and Zn also decreased significantly after acid washing. This was because these oxides reacted with hydrochloric acid to form chlorides and water, allowing them to be removed with the filtrate from the solid ash. However, the SiO

2 content in the ash increased from 53.96% to 60.16% after treatment with 5 M hydrochloric acid. This was because silica did not react with hydrochloric acid, and as the content of other oxides decreased, the proportion of silica increased. This indicated that the acid washing process could significantly increase the proportion of silica, reduce the impact of other oxides on silica purity, and thus enhance the final purity and extraction efficiency of nano-silica.

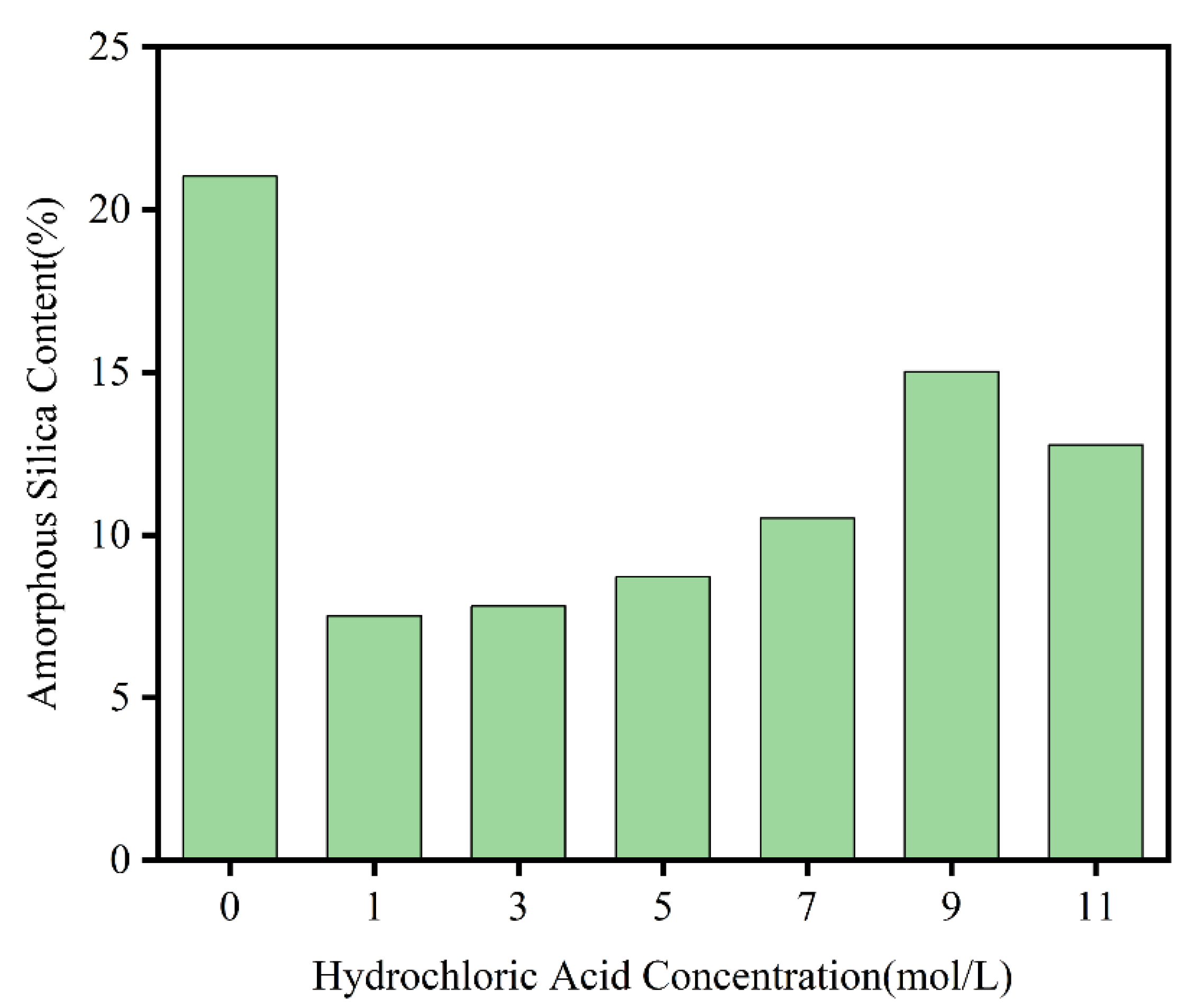

To determine the trend in the proportion of easily extractable amorphous silica in the BS after acid treatment, the content of amorphous silica in the BS treated with different acid concentrations and in the untreated BS was measured based on the method for detecting silicon-containing fertilizers published by Japan’s Food and Agricultural Materials Inspection Center (FAMIC) (4.4.1-c). As shown in

Figure 7, the content of amorphous silica gradually increased with increasing hydrochloric acid concentration, reaching a peak at 9 M. However, even at the peak, the content of amorphous silica remained lower than that in the untreated BS sample. The acid treatment step dissolved part of the silica, which was removed with the filtrate during filtration. This dissolved portion was actually the easily extractable amorphous silica present in the raw BS. As the acid concentration increased, the higher concentration of hydrochloric acid reacted with silica, directly converting some other forms of silicon into amorphous silica. Although this conversion increased the total amount of amorphous silica, part of the initially easily extractable amorphous silica was dissolved and removed during the initial acid treatment, resulting in a final measured content of amorphous silica that remained lower than that of the untreated BS sample after reaching a certain peak.

In summary, while acid pretreatment resulted in some loss of the original amorphous silica in the BS, the amount lost was relatively small in the overall silica content. As discussed earlier, the acid washing step helped improve purity, extraction efficiency, and the physicochemical properties of silica. By adjusting the acid concentration, the activity of silica in the BS could be regulated, making it easier to extract. From the perspective of economic production, an increase in hydrochloric acid concentration led to higher costs and greater experimental risks. Therefore, the most suitable concentration of hydrochloric acid for pretreatment was ultimately determined to be 5 M.

3.2. Effects of Alkali Fused Materials

In this study, we initially followed the method proposed by An et al. [

26], using conventional alkali leaching followed by a carbonation reaction to extract silica. However, the purity and extraction yield of the obtained silica were only 20%. Based on the property that high-temperature calcination after mixing ash with alkali could alter the crystal form and enhance the activity of silica [

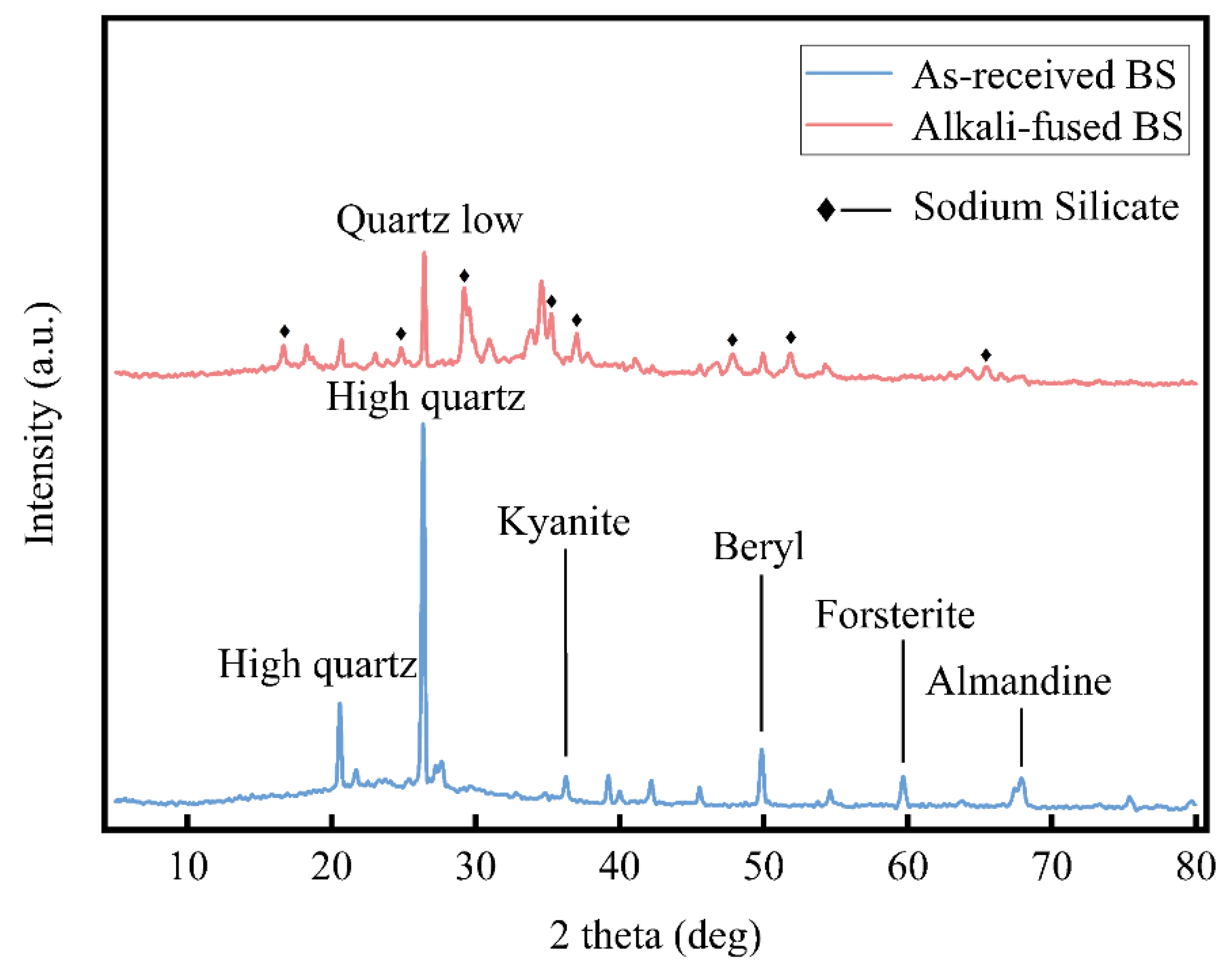

27], this study conducted X-ray diffraction experiments on the BS before and after high-temperature alkali fused. The experimental results, as shown in

Figure 8, indicated that the SiO

2 crystal form in the as-received BS before high-temperature alkali fused mainly consisted of stable forms such as High-quartz, Kyanite, and Beryl. In the alkali-fused BS activated by high-temperature fused, numerous peaks of sodium silicate appeared between diffraction angles of 10° and 70°. The presence of these sodium silicates indicated the transformation of the stable crystal form of SiO

2 into more reactive and easily extractable soluble silicates.

To determine the effects of different alkaline materials used in alkali fused on the purity and extraction yield of the products, a controlled variable method was employed. The variable alkaline materials included three solid alkalis: NaOH, Ca(OH)2, and KOH. The experimental results showed that when NaOH solid was used as the mixing material, the extraction yield of silica significantly increased to 65.09%, with a purity of 86.92%. However, when Ca(OH)2 solid was used as the mixing material, the quantity of solid obtained was relatively low. This was because Ca(OH)2 is a weak base that reacts with silicates to form insoluble calcium silicate, which became mixed with the remaining solids in the ash, making effective separation difficult. Therefore, this study first excluded Ca(OH)2 as a mixing material. NaOH and KOH are strong bases, which, after alkali fused, generated corresponding soluble silicates when added to the liquid, and silica solids were subsequently obtained through a carbonation reaction. In the experiments, the purity of the white solids obtained from both KOH and NaOH was similar; however, the extraction yield using NaOH as the mixing agent was higher.

Consequently, this study adopted a method of co-firing with alkali mixing to achieve the goal of altering the silica crystal form in the BS and enhancing the activity of SiO2. Based on the aforementioned experimental results and an analysis of economic factors, while considering safety, the use of NaOH solid for co-firing proved to be the most effective in enhancing the activity of SiO2 in the BS. Therefore, the alkaline fused material selected for this study was NaOH.

3.3. Effects of the Mixing Ratio

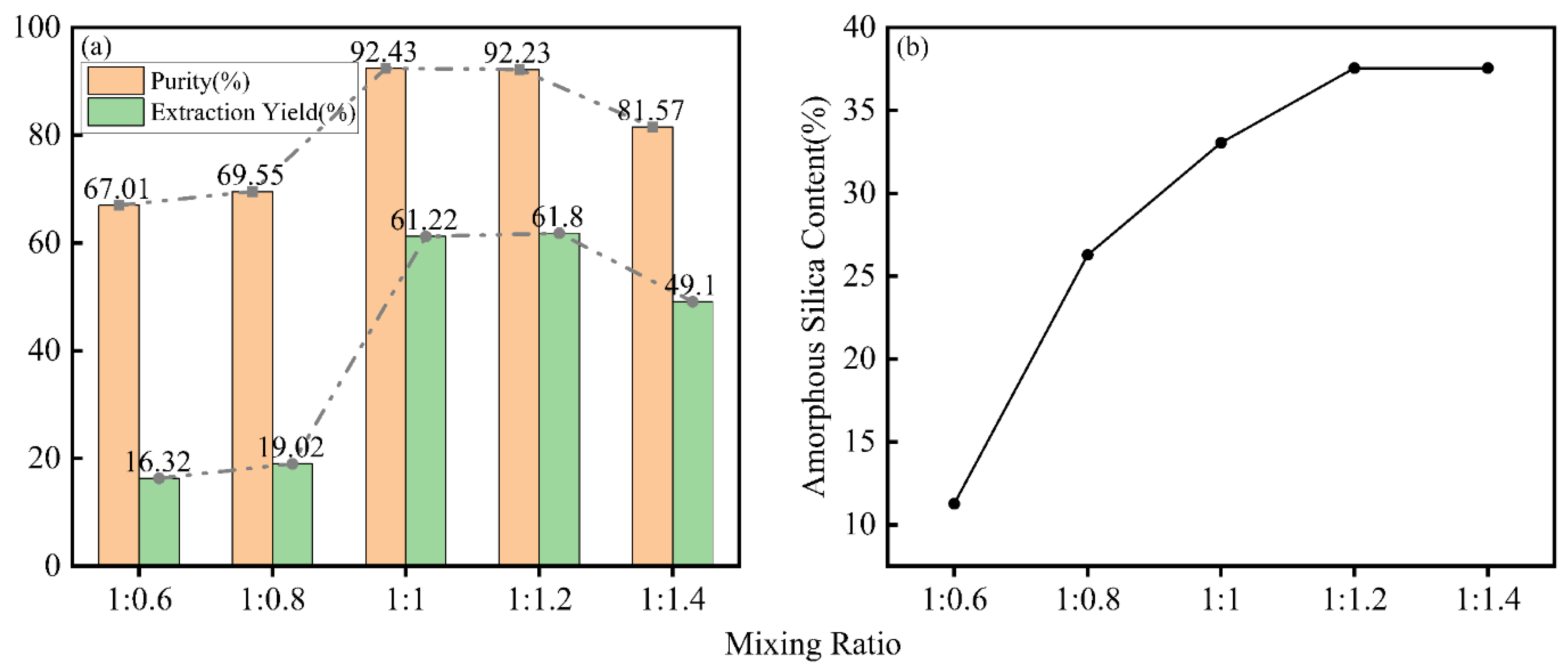

The mixing ratio referred to the different mass ratio of the BS, dried after acid treatment, to solid NaOH during the alkaline fusion process. This study aimed to determine the optimal mixing ratio and its effects on the content of amorphous silica in the BS after alkaline fusion, as well as the purity and extraction yield of the product. Using the method of controlling variables, the mixing ratios were set at 1:0.6, 1:0.8, 1:1, 1:1.2, and 1:1.4. The experimental results, shown in

Figure 9, indicated that as the mixing ratio increased, the extraction yield, purity, and content of amorphous silica initially increased and then decreased. This phenomenon occurred because SiO

2 in the BS existed in stable crystalline forms such as high quartz and sanidine. In a high-temperature environment, these stable crystals reacted with NaOH, transforming into extractable Na

2SiO

3. This conversion process facilitated the extraction of silica, thereby enhancing the overall extraction efficiency. The maximum purity and extraction yield of 92.43% and 61.8% were achieved at mixing ratios of 1:1 and 1:1.2, respectively. However, further increasing the mixing ratio led to an excess of alkali, which existed as Na

2O in the final product and reduced the purity of nano-silica. The detection method for silicon-containing fertilizers published by FAMIC was modified to measure the content of amorphous silica in the BS after alkaline fusion. The variation in the content of amorphous silica indicated changes in the extent to which silica could be extracted. The content of amorphous silica reached its maximum at a mixing ratio of 1:1.2, indicating that the amount of NaOH mixed at this ratio effectively converted the SiO

2 form in the BS into an extractable amorphous state.

Based on the above experimental results, appropriately increasing the mixing ratio could enhance the extraction yield and purity of silica, as well as increase the content of amorphous silica, thereby improving the reactivity of silica in the BS. In this study, a mixing ratio of 1:1.2 was employed for mixed combustion to best enhance the reactivity of SiO2 in the BS, thereby facilitating silica extraction. Therefore, the mixing ratio used in this study was 1:1.2.

3.6. Product Quality and Characterization

The final prepared nano-silica was characterized according to the industry standards HG/T 3062-3072, and the product parameters are detailed in

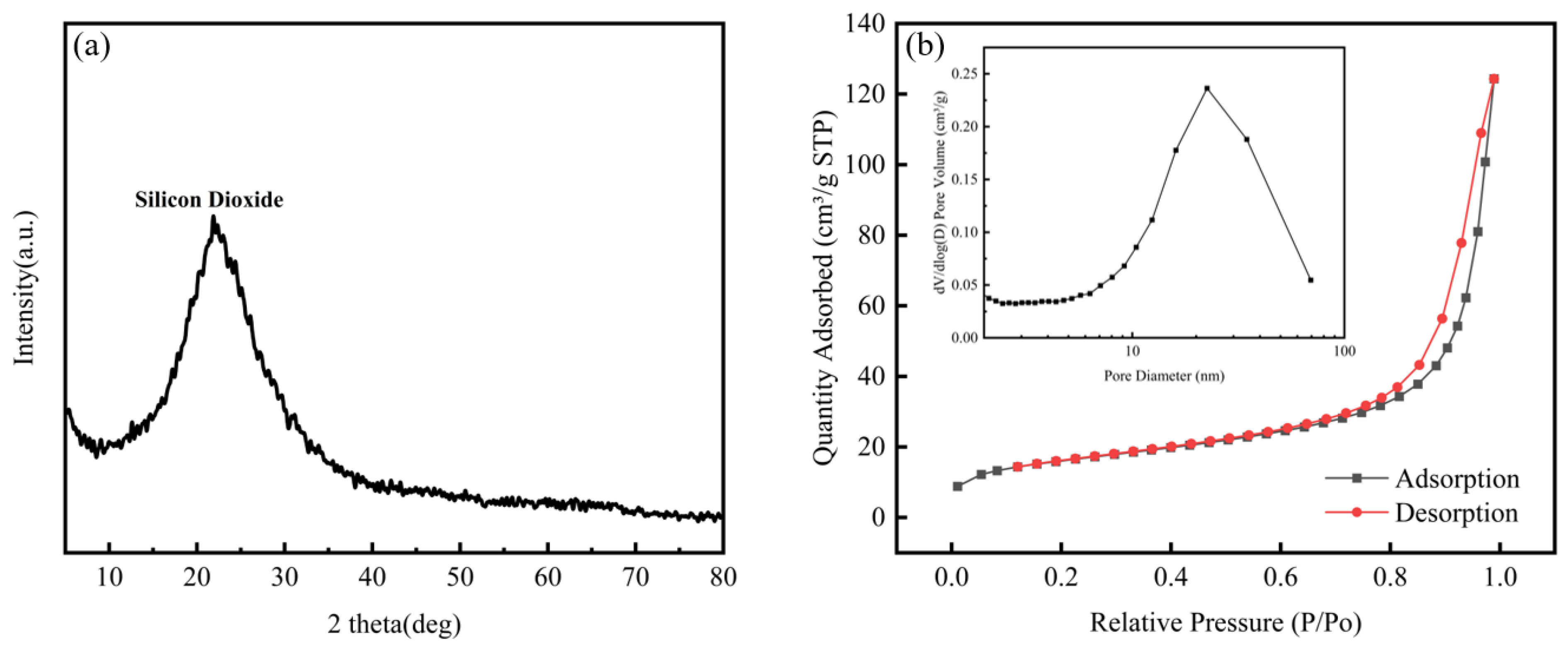

Table 4. A comparison of the parameters with the industry standard HG/T 3061-2020 confirmed that all parameters fell within the prescribed standard ranges. As shown in

Figure 11(a), the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the prepared nano-silica displayed a typical diffuse scattering diffraction pattern. At 2θ = 21°, the curve presented a broad and shallow peak, which corresponded to the position of soluble silicates in the XRD spectrum of the BS treated with hydrochloric acid. No sharp characteristic peaks of crystalline SiO

2 were observed in the figure, indicating clearly that the obtained nano-silica powder was in an amorphous form, with no significant impurities detected. Therefore, it can be concluded that the nano-silica powder was primarily composed of an amorphous material, showcasing the high purity characteristics of the product.

Figure 11(b) presented the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm and the corresponding desorption pore volume curve for the nano-silica obtained through the optimal process. Using a BET physical adsorption apparatus, the specific surface area of the obtained nano-silica was measured to be 55.9916 m

2/g, with an average pore diameter of 16.2717 nm. The presented adsorption-desorption curve in the figure corresponded to Type II isotherms defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and prominently exhibited characteristics of an H3-type hysteresis loop. This result indicated the presence of a distinct plateau in the adsorption isotherm, reflecting a uniform pore size distribution in the nano-silica samples, as well as a large specific surface area and moderate pore volume. This characteristic not only enhanced the ability to adsorb macromolecules but also effectively facilitated the mass transfer process.

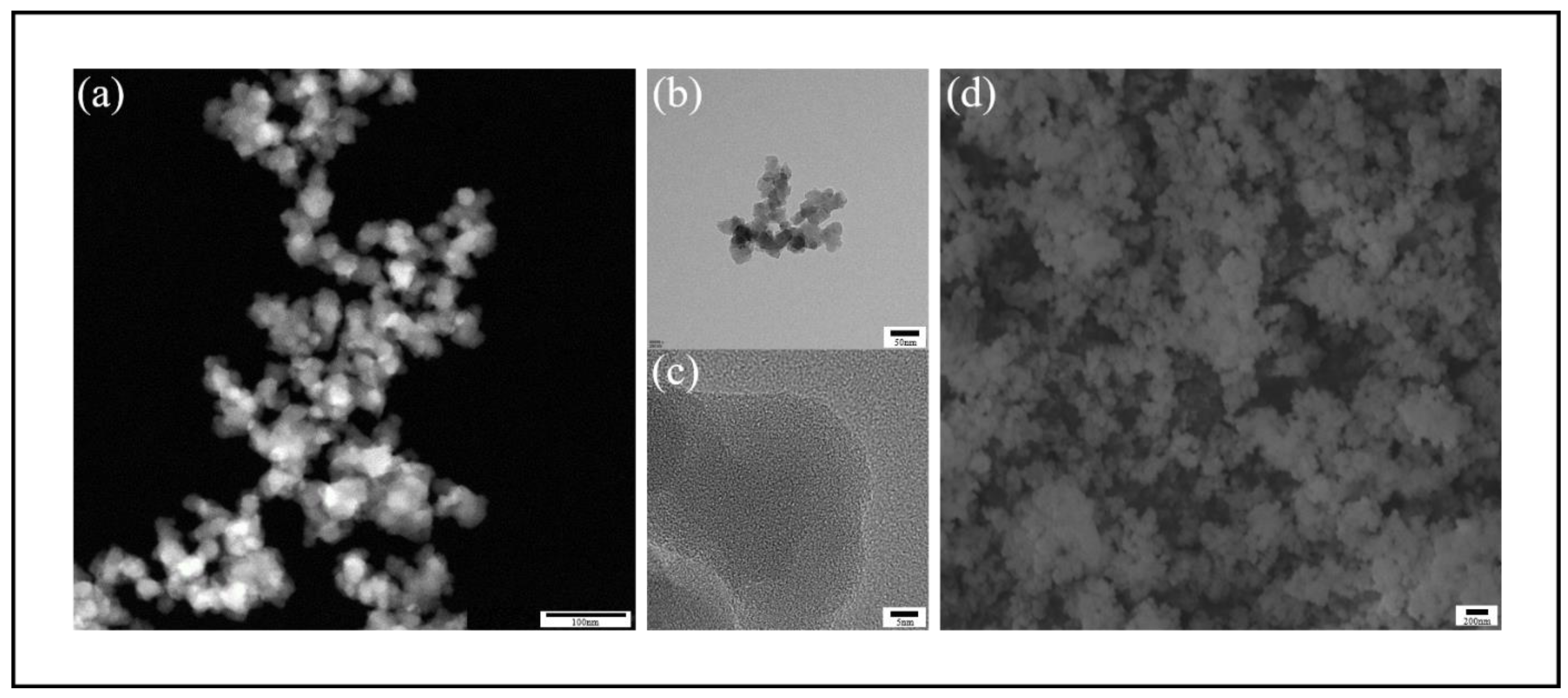

To confirm that the extracted silica from the optimal process consisted of nanoparticles and to observe the microscopic structure and morphological characteristics of the nano-silica, this study employed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for examination, as illustrated in

Figure 12(d). Under the scanning electron microscope, the silica appeared as aggregates of smooth, spherical particles. The transmission electron microscopy images clearly revealed the high-resolution microstructure of silica derived from CSA. At a magnification of 300,000 times in

Figure 12(a), we observed that the nano-silica particles exhibited a quasi-spherical morphology, along with a certain degree of aggregation. Further examination of

Figure 12(b) revealed that these silica particles were composed of interconnected quasi-spherical particles with a wide size range, distributed between 10 and 50 nanometers, consistent with the definition of “nano-silica.” In the high-resolution image shown in

Figure 12(c), all samples exhibited a disordered state, with no discernible crystal structure. This observation indicated that the prepared nano-silica was entirely amorphous, further confirming its non-crystalline nature.

To clarify the superiority of the silica prepared in this study, various properties of the silica obtained from this research were compared with those derived from different silicon sources, as shown in

Table 5. In terms of silica content among the prepared samples, the silica synthesized in this study achieved a purity of 92.73%, surpassing that of most other silica derived from different sources listed in the table. Furthermore, under the condition of high purity, this study reported a silica extraction yield of 92.73%, which was the actual yield obtained during the experimental process. Due to certain losses in the experimental procedure, the theoretical extraction yield should exceed 92.73%. Nevertheless, the extraction yield of nano-silica synthesized in this study was significantly higher than that of other methods; for instance, the extraction yield reported by Piela et al. was 47%, Chen et al. achieved 68.01%, and Liang et al. reported a yield of 20.45%. Although Estevez et al. also reported an extraction yield of 88%, the purity of their product was unknown, and their synthesis process took as long as five months. Consequently, the extraction yield reported in this study was far superior to those previously documented in the literature for synthesizing nano-silica, and this high extraction yield further reduced the production costs of nano-silica. In comparison to silica produced from BPP straw ash with particle sizes greater than 100 nm, this study produced nano-silica with smaller particle sizes (10 nm–50 nm), which has higher added value and broader application potential. Additionally, when compared to nano-silica prepared from biomass that had been calcined in a laboratory, the properties of the nano-silica synthesized in this study using direct combustion ash from BPP as the silicon source were similar, providing strong evidence for the feasibility of using direct combustion ash to produce nano-silica in practical production settings. Therefore, the superiority of this study lay in the utilization of direct combustion ash from BPP as a silicon source, which significantly enhanced the extraction yield of nano-silica to over 90% while ensuring high purity and other important characteristics.