1. Introduction

Alkali-activated geopolymer binder, identified as an alternative to conventional cement as well as a kind of chemically bonded ceramics, are aluminosilicate inorganic polymers that have the advantages of high strength, good corrosion resistance, and low carbon emission during production and holds amorphous net-work structures, has attracted considerable attention from both the construction and waste management, due to its unique properties compared with Portland cement, such as reduced CO

2 emission, simple technological process, excellent durability, and reduced cost [

1,

2,

3]. Therefore, the recycling of metallurgical solid wastes has intriguing increasing attention for fabricating cementitious materials.

Currently, the global perspective on burgeoning sustainability boosts the development of converting industrial by-products slag derived from blast furnace iron making and fly ash (FA) from coal-fired power plants into cementitious materials, which is very promising to develop solid waste-based pastes without heating curing at about 60 °C [

4], due to the reactive calcium involved in slag. Investigations and wide applications of alkali-activated slag/FA geopolymers [

5,

6,

7] have been hotspots to realize the recycling economy and environmental protection. Meanwhile, silica fume (SF) as an industrial by-product, also possesses an amorphous aluminosilicate nature, due to the more sodium alumino-silicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) network resulting in the increased compressive strength [

8], facilitating the geopolymerization and forming denser structures [

9].

Moreover, the excellent heat resistance of slag/FA geopolymers has been manifested in comparison to traditional Portland cement. Pavel et al. [

10] describe the behavior and structural changes of the alkali-activated slag matrix during and after exposure to temperatures as high as 1200 °C. The effect of elevated temperatures on the chemical stability and residual compressive strength of neat slag pastes manufactured with sodium sulfate activated is reported [

11]. However, the relative strength of the neat alkali-activated slag paste is superior to the counterpart incorporated SF, which exerts an adverse impact on the thermal shock resistance [

12]. Therefore, whether or not the SF generates positive roles in slag/FA geopolymers needs to be clarified to develop multi-component SF/slag/FA binders with outstanding properties, especially for the performance under elevated temperatures.

Consequently, the review of the literature has indicated that few publications report the performance of SF involved in slag/FA pastes after exposure to elevated temperatures. The primary purpose of this paper investigates the effects of SF on the microstructure of slag/FA binders after exposure to elevated temperatures, which are activated by sodium silicate solution with the SF:slag:FA ratio of 10:30:60 (wt.%) [

13]. The characterizations included the residual stresses, mass loss, shrinkage, mineral phase, heat flow, and morphology, with alkali-activated slag/FA (slag:FA = 30:70, wt.%) binder without SF as a control. It explores the effect of SF on the mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag/fly ash pastes subjected to elevated temperatures, prompting the effective recycling approach for metallurgical solid wastes.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Raw materials

FA was obtained from the Hancheng power plant (Shan’Xi province) with Blaine specific surface area of 500 m

2/kg and a mean particle size of 11.2 μm after oven drying at 105 °C and ball-milling for 1 h. Granulated ground blast furnace slag was obtained from Delong powder company with Blaine specific surface area of 420 m

2/kg and a mean particle size of 15.5 μm. SF was collected from Linyuan company with Blaine specific surface area of 25 m

2/g and a mean particle size of 2.6 μm. The chemical compositions of raw materials are shown in

Table 1. Alkali-activator, Na

2SiO

3·9H

2O (A.R.), was purchased from Tianjin Yaohua chemical reagent company.

2.2. Preparation of specimens

The alkali-activated SF/slag/FA pastes were synthesized by adding sodium silicate (15wt% Na

2SiO

3·9H

2O) solution into the uniform mixture of FA, slag, and SF with a water/(SF + salg + FA) ratio of 0.3 to form the slurry in a cement mortar machine, the weight ratio of FA:slag:SF was 6:3:1 [

13], the specimen with a slag/FA ratio of 7:3 was used as a reference. The slurry was poured into the stainless triplet mold of 160 × 40 × 40 mm

3, which was demoulded after curing for one day and cured in a standard cement mortar curing box with a relative humidity of 90% at room temperature (RT) for 28 days. Finally, the specimens were exposed to elevated temperatures with an increment of 350 °C during 150-1200 °C and a heating rate of 5 °C/min, maintaining 2 h at various elevated temperatures of 150, 500, 850, and 1200 °C, air-cooled to RT for evaluation, respectively.

2.3. Characterizations

Compressive strength was tested by a full-automatic cement mortar compressive testing machine of YAW-300 type with a pressurization rate of 2.4 kN/s, the error was 0.1 MPa. Flexural strength was measured by a motorized bending tester of DKZ-5000 type, the error was 0.1 MPa. Micro-morphology analysis of samples was conducted on a Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope (SEM) with a working condition of 20 kV voltage. X-ray diffraction patterns of specimens were measured on a D/MAX-2400 X-ray diffractometer equipped with a rotation anode using Cu Kα radiation.

Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TG) of Mettler was used to measure the mass loss and heat flow of specimens during the heating process of 50-950 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 30 °C/min. Digital photos were shot by a Fujifilm AV100 camera. FTIR spectrum was measured using a spectrometer (FTIR-650) in absorption mode, it was conducted in the range of 3000~500 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1, and samples were mixed with KBr with a sample/KBr weight ratio of 1/100. Pore size distributions of samples after 28 days of curing were tested by AUTOPORE 9500 mercury porosimetry under a nitrogen pressure of 0.3 MPa.

3. Results

3.1. XRD

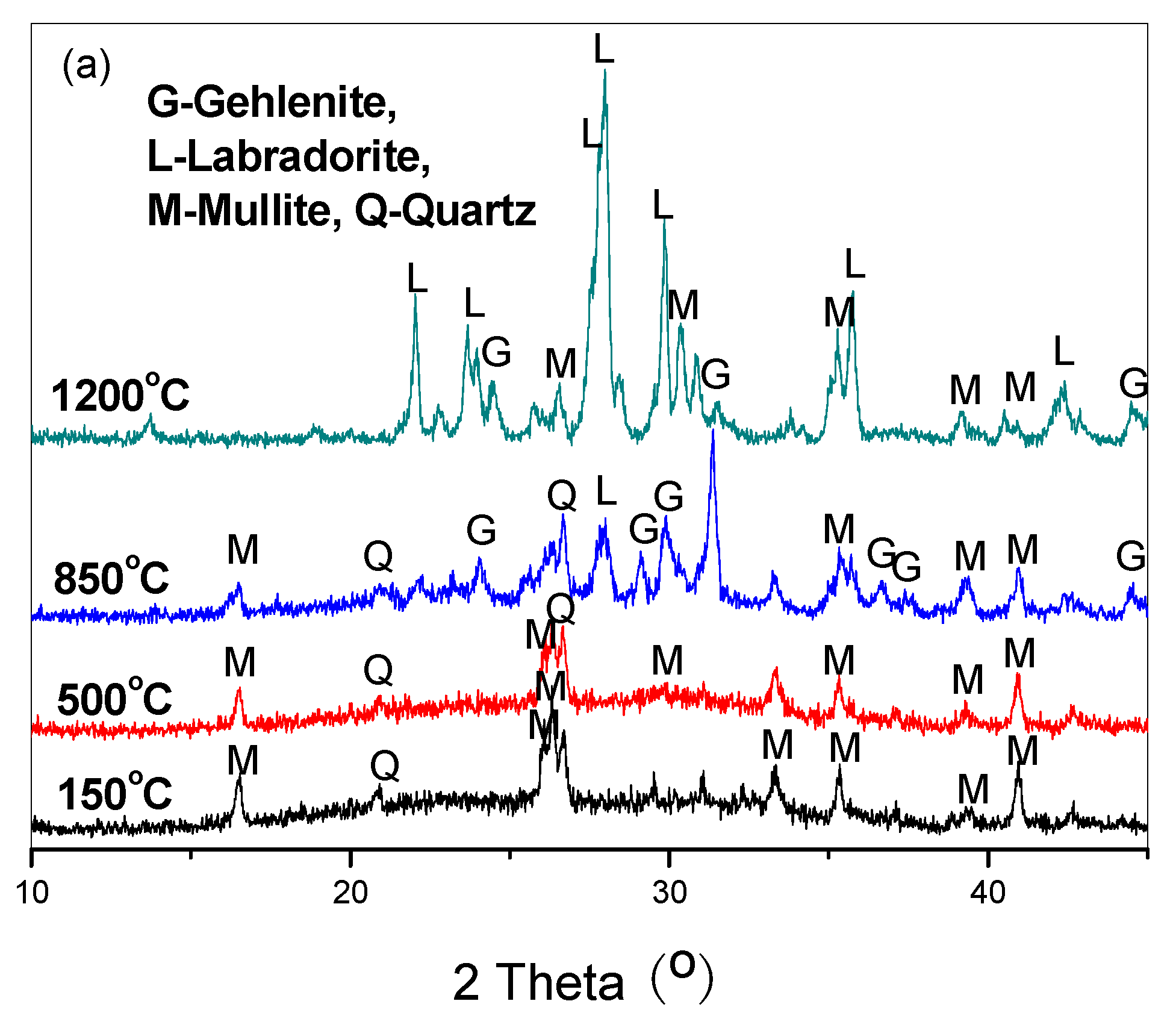

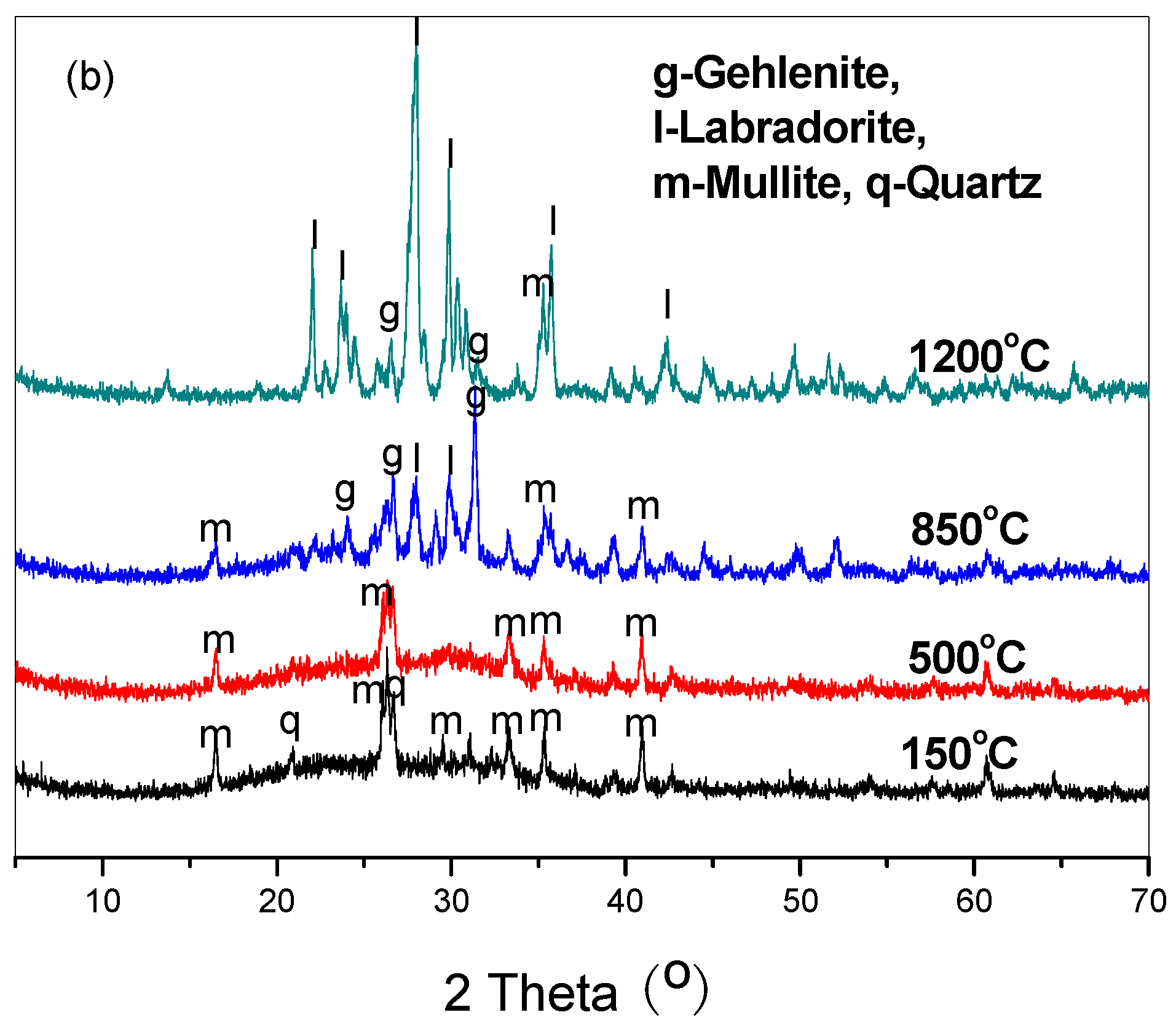

XRD patterns of specimens after exposure to elevated temperatures are shown in

Figure 1, it is noted that the patterns of specimens with SF are similar to that of specimens without SF, indicating no new mineral formed after incorporating SF. However, the Gehlenite as Ca

2Al(AlSiO

7) (No. of JCPDS:98-000-0226) and labradorite as (Ca, Na)(Si, Al)

4O

8, (No. of JCPDS:98-000-0272) form as predominant mineral phase after 850 °C and 1200 °C treatment, it demonstrates that the exposure to 850 °C induces transformation of gehlenite and labradorite, which is enhanced by the heating treatment of 1200 °C, and the molar ratio of CaO/SiO

2 and Al

2O

3/SiO

2 decreases from gehlenite to labradorite.

Meanwhile, there are the diffraction peaks of quartz (SiO

2, No. of JCPDS: 98-000-0369) and mullite (Al

4+2xSi

2-2xO

10-x(x~0.4), No. of JCPDS:98-000-0319) in XRD patterns of specimens after exposure to 850 °C and 1200 °C, but their diffraction intensity of peaks significantly weaken. Bernardo et al. [

14,

15] demonstrate that the mixture of water glass/soda–lime–silica/clay, as well as a mixture of red mud/fly ash/porcelain stoneware tiles, could transform into labradorite with good mechanical strength after calcination. Segui et al. [

16] suggest that labradorite grows into a binder composed of pozzolan, lime, and gypsum. Because kaolin clay promotes the formation of labradorite in glass–ceramics [

17], Fang et al. [

18] suggest the released CaO together with unreacted portlandite and gypsum, interacting with N–A–S–H to form labradorite after calcination at 1050 °C. Therefore, it determines that activated CaO, Al

2O

3, and SiO

2 could transform into the labradorite after high-temperature treatment.

Figure 1.

XRD of sample including (a) Slag/FA binders and (b) SF/slag/FA binders.

Figure 1.

XRD of sample including (a) Slag/FA binders and (b) SF/slag/FA binders.

Because the content of quartz in the fly ash of C type decreases on sintering above 850 °C and transforms into new crystallite structures [

19]. The finding of our research is in agreement with the report that gehlenite is drastically reduced as it starts to react with quartz towards wollastonite and anorthite at 1050 °C in the Fe

2O

3-SiO

2-Al

2O

3 clay [

20]. And Ding et al. [

21] also suggest that mullite and corundum of FA could dissolve and transform into calcium sodium hydrate silicate (NaCaHSiO

4). It confirms that quartz and mullite could transform into feldspar above 850 °C in an alkali-activated slag/FA binder system.

3.2. Physical properties of specimens subjected to high temperatures

3.2.1. Residual stress of specimens

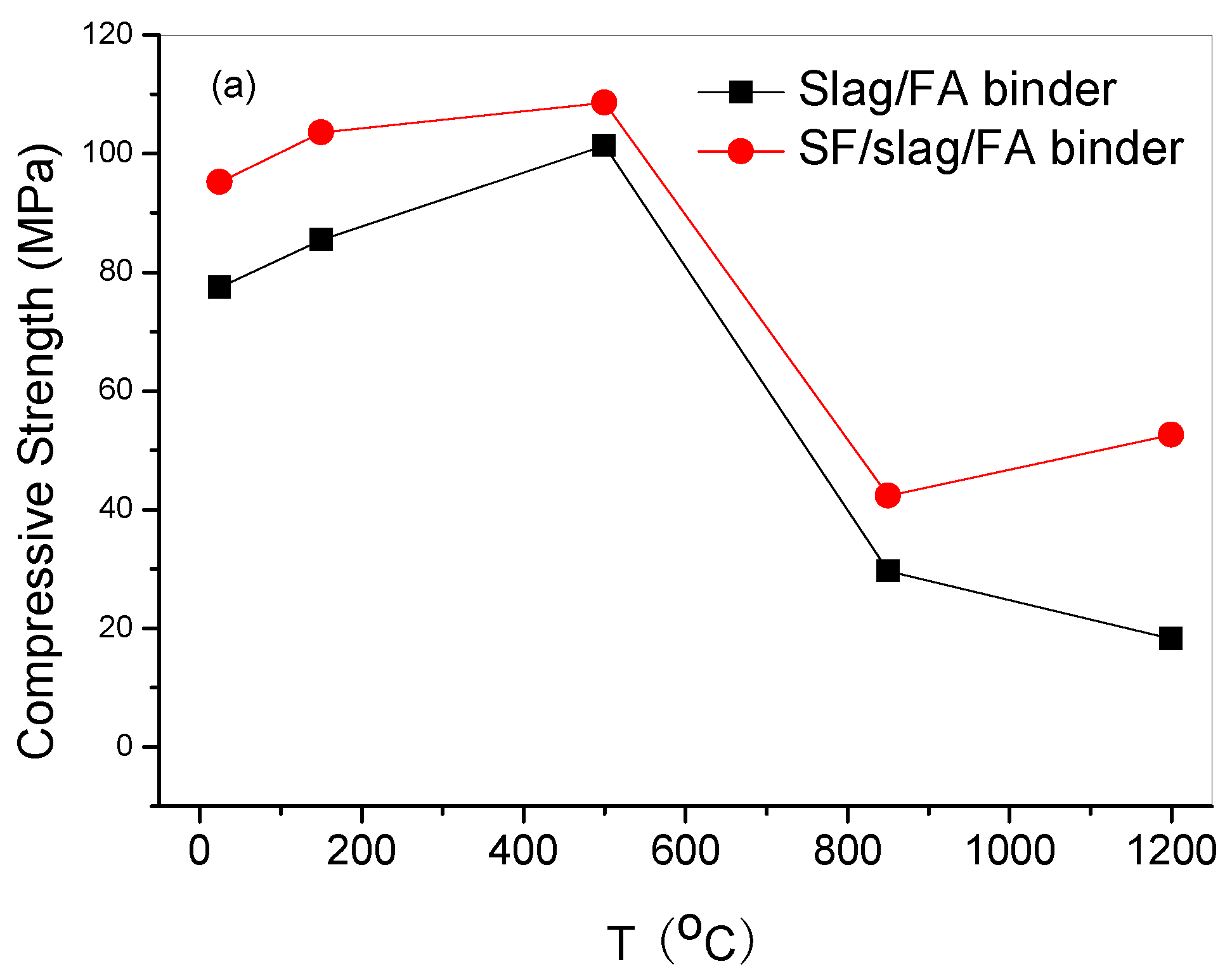

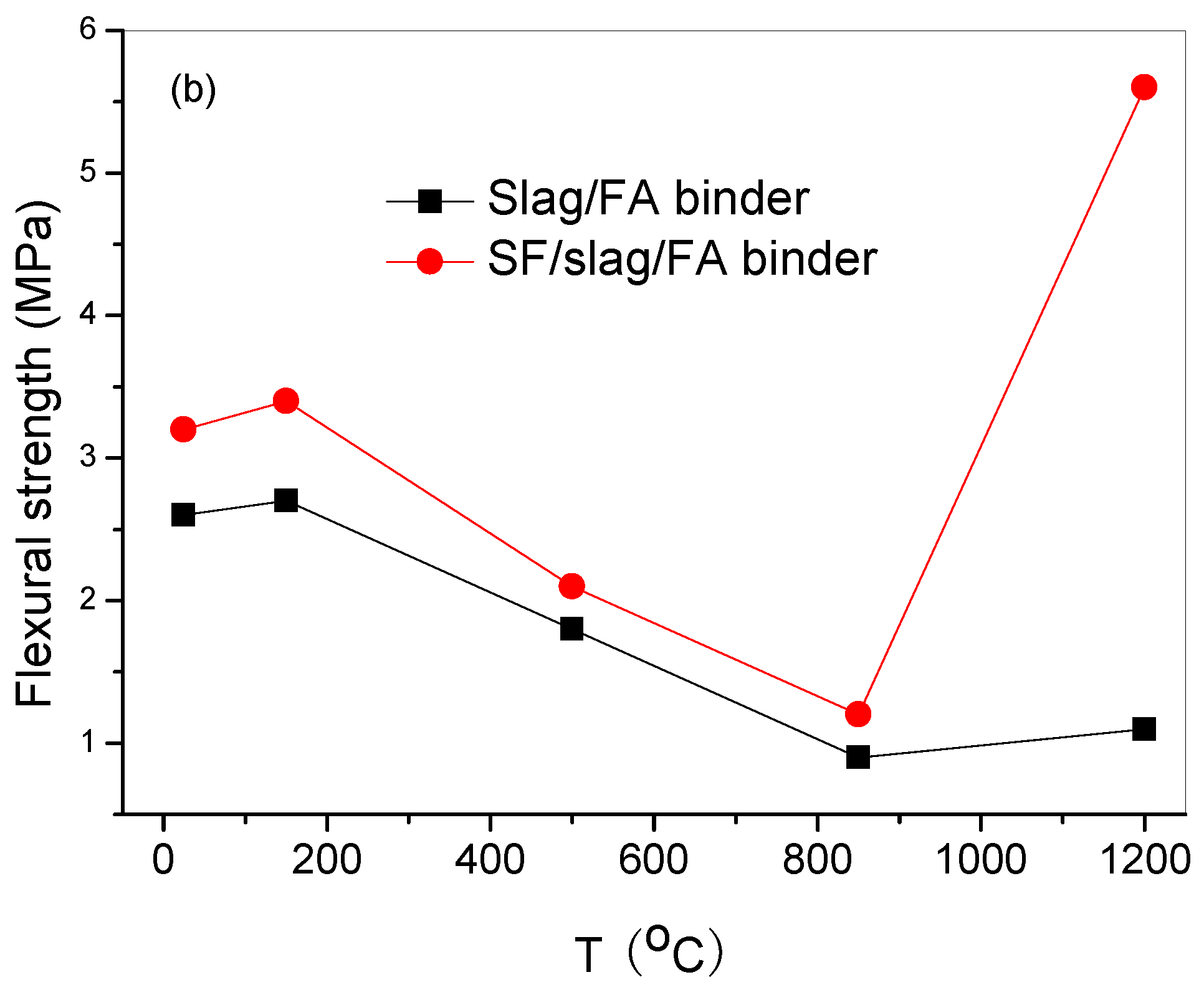

The residual stress of specimens exposed to elevated temperatures is shown in

Figure 2, the specimen with SF displays higher mechanical performance than the specimen without SF, indicating that SF imparts a strengthening effect to the slag/FA binder, as well as after exposure to various elevated temperatures. The residual compressive strengths are improved after heat treatment of 150 and 500 °C compared with the specimen at RT, corresponding to 105.6 MPa (increased by 8.8%, 150 °C) and 108.6 MPa (increased by 14.1%, 500 °C) for the specimen incorporated SF. Given the decomposition [

22] of C-S-H/C-A-S-H after 850 °C treatment, a rapid decline of residual stress presents for both specimens. However, the flexural strength of the specimen with SF after 1200 °C treatment climbs to 5.6 MPa sharply, while that of the specimen without SF is only 1.1 MPa, which might be attributed to the transformation of labradorite combined with the XRD results.

Figure 2.

Mechanical properties of specimens subjected to high temperatures including (a) Compressive strength and (b) Flexural strength.

Figure 2.

Mechanical properties of specimens subjected to high temperatures including (a) Compressive strength and (b) Flexural strength.

3.2.2. Deformation

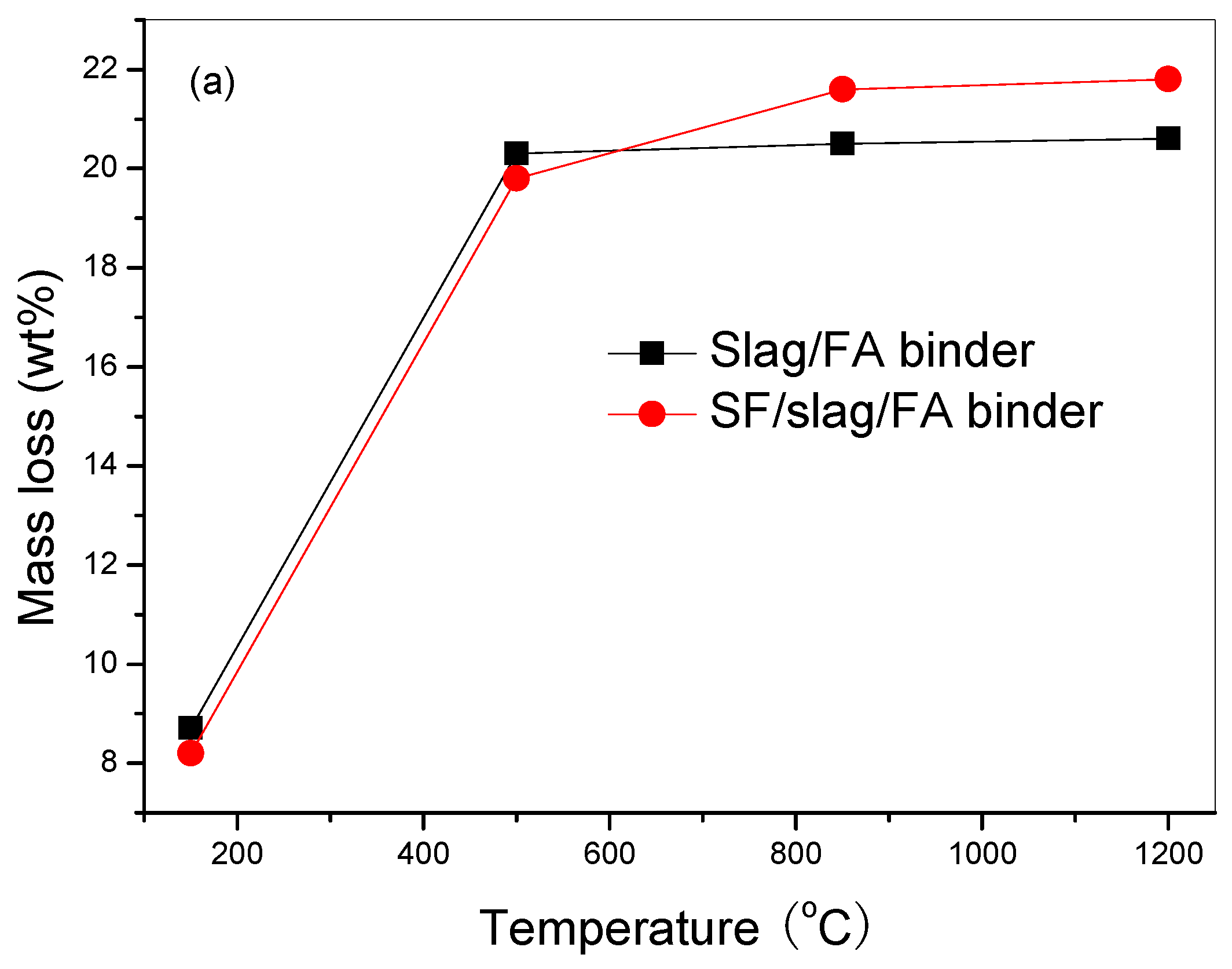

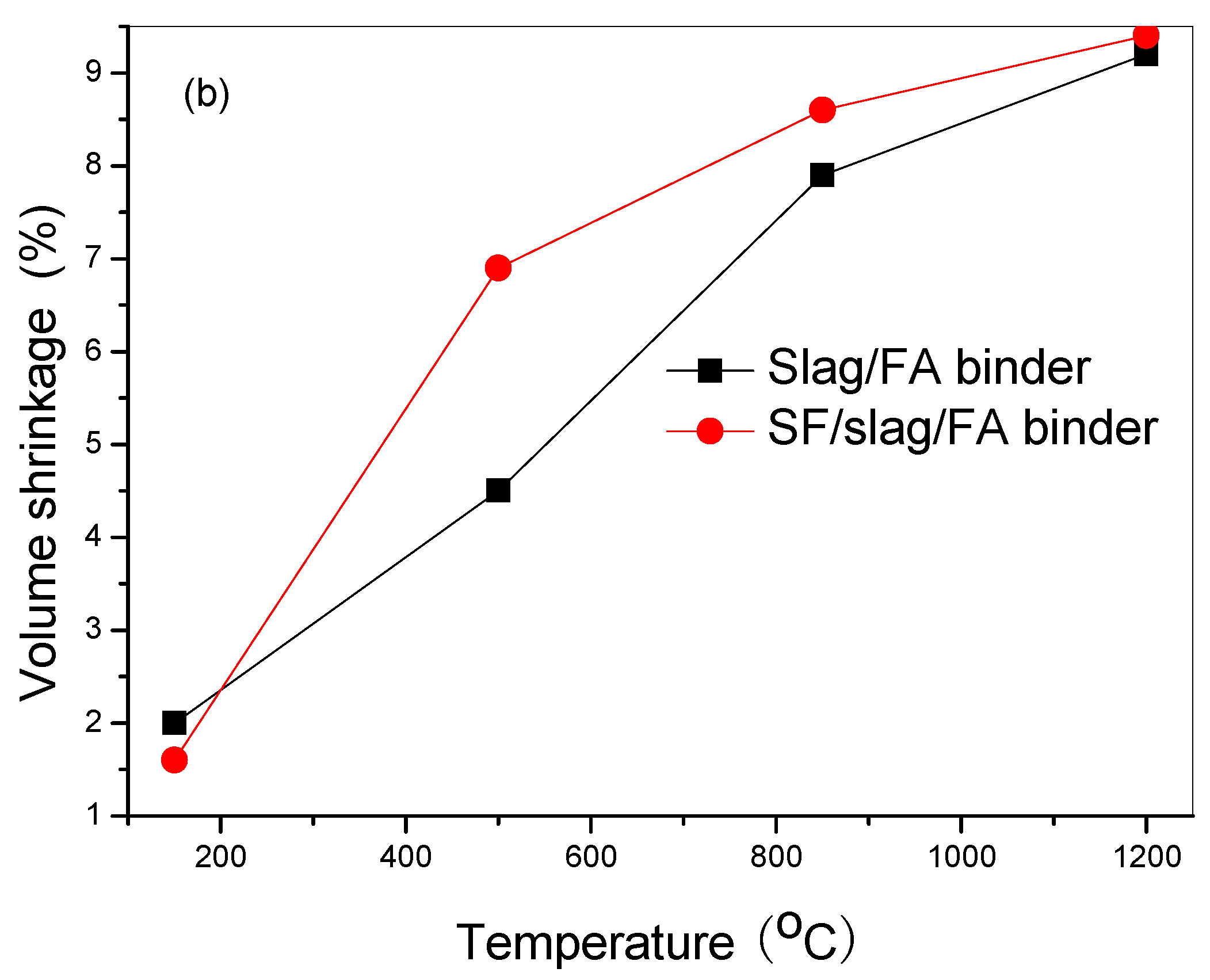

The mass loss of specimens and volume shrinkage of specimens are displayed in

Figure 3. For the specimen with SF, higher stability presents under sub-high temperatures while greater mass loss and shrinkage are observed under high temperatures. The shrinkage approaches 6.9% at 500 °C, 8.6% at 850 °C, and 9.4% at 1200 °C, implying that the replacement with 10 wt% SF triggered more deformation under higher temperatures, compared with the control without SF.

3.3. Morphology and microstructure

3.3.1. Macro-morphologies

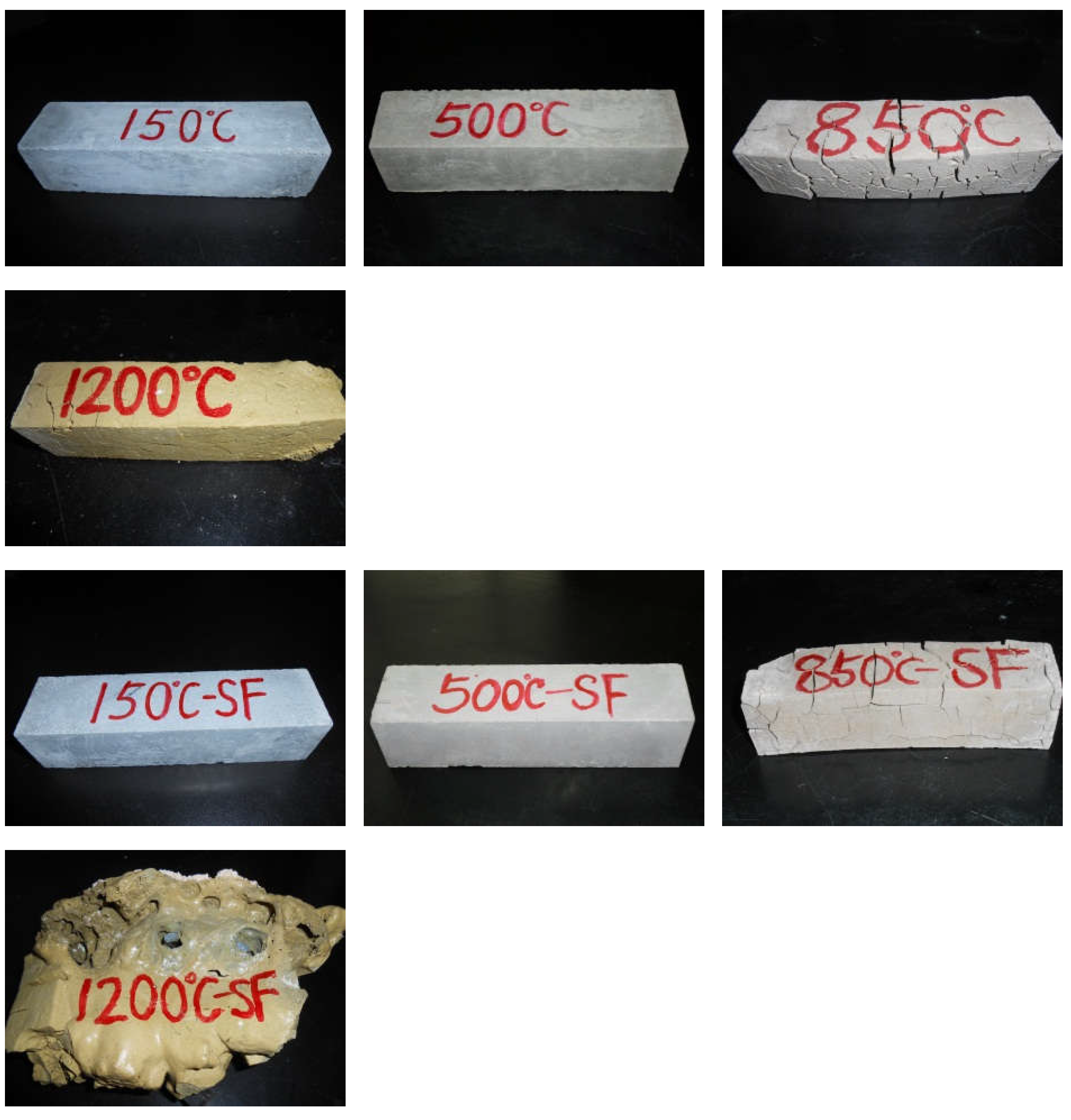

The macro-morphologies of pastes are presented in

Figure 4, the volume of specimens exhibits slight shrinkage in their dimensions continuously and cracks grow with the increasing heat treatment temperatures. The higher temperature leads to bigger cracks as shown in

Figure 4. On the other hand, the specimens with SF display fewer and shallower cracks in comparison to specimens without SF, especially after the treatment of 850 °C. Therefore, the bloating effect on the dimension for specimens with SF occurs after exposure to 1200 °C, while specimens without SF keep the initial shape, revealing the reduced melting point of slag/FA binders incorporated by SF.

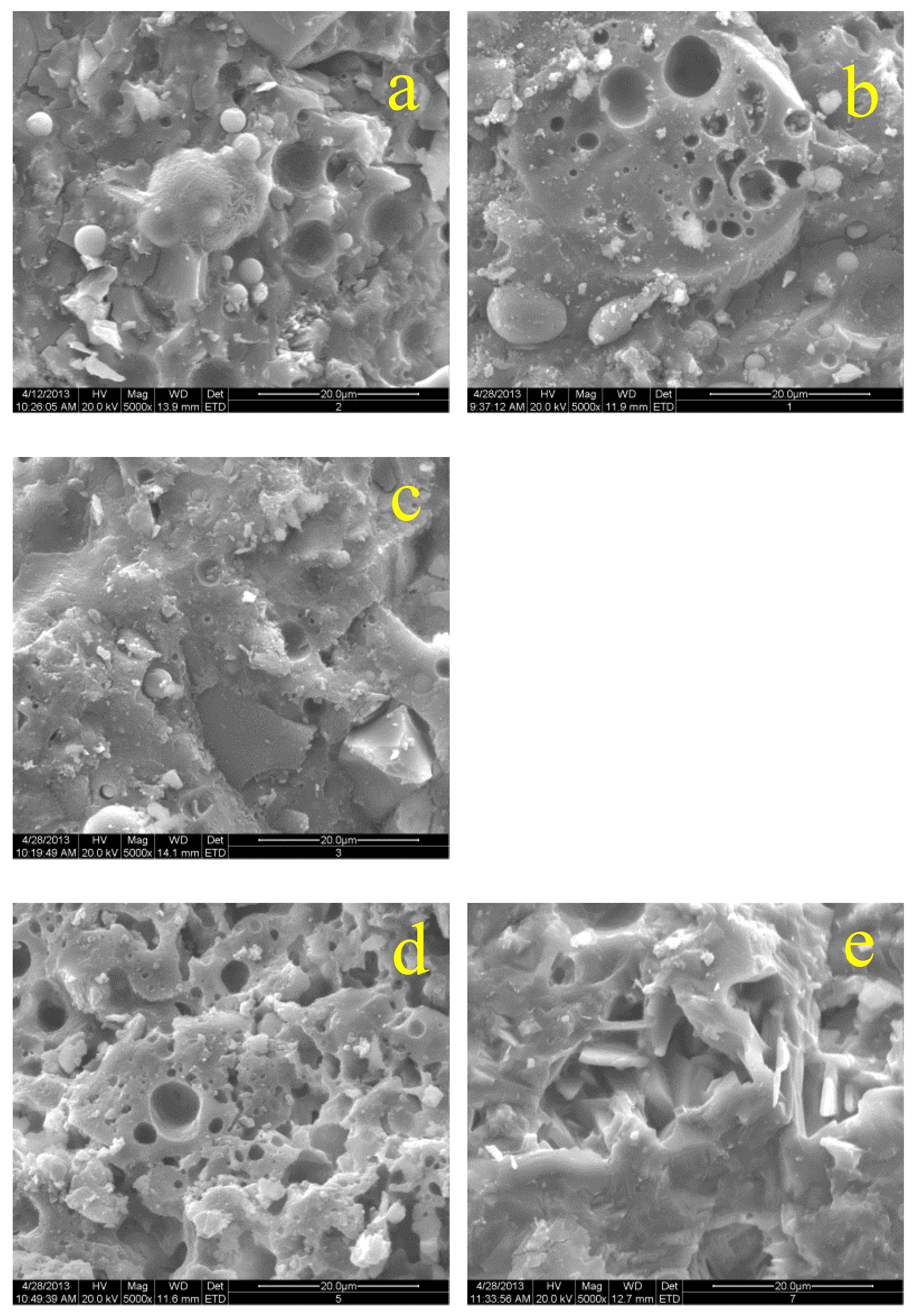

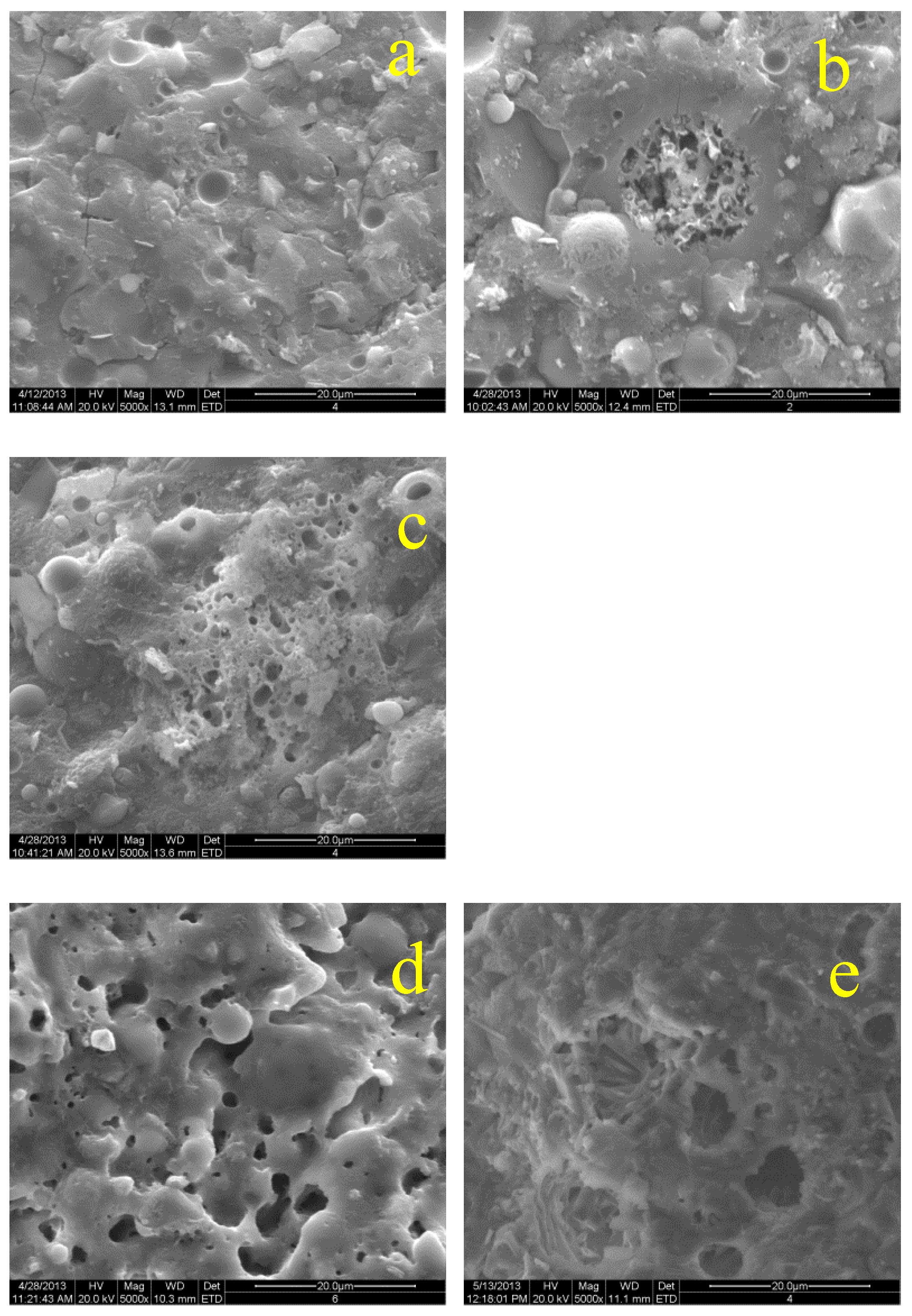

3.3.2. Micro-morphologies

The micro-morphologies of specimens subjected to elevated temperatures are presented as a series of electron micrographs with an amplification of 5000× in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The coexistence of the geopolymer gels and crystals is observed, but unreacted spherical FA particles disappear and the rod-like or needle-like feldspar increases with the increasing treatment temperatures gradually. More and larger pores or holes appear on the fracture surface of specimens after 850 °C heating as shown in

Figure 5d or

Figure 6d. However, denser structures and smaller holes are observed for SF/slag/FA binder (

Figure 6a–c) after sub-high temperature exposure in comparison to the specimen without SF (

Figure 5a–c). Compared with

Figure 5e, the sample with SF held a denser structure after exposure to 1200 °C, the needle-like feldspar is covered and filled by the amorphous silicates as shown in

Figure 6e, revealing that the SF effectively inhibits the cracking and facilitates densification to some extent

3.3.3. Pore size distributions

The replacement with 10 wt% SF favors improving the compactness of slag/FA pastes, the pore volume of 0.2~3 μm exerts an obvious increase as shown in

Table 2, which climbs from 11.39% to 35.81%, indicating the denser and compact structure. The porosity drops from 20.93% to 13.47%, and the median pore diameter decreases from 6.4 to 5.6 nm. Combining with the images of SEM in

Figure 5a and

Figure 6a, confirming again that the incorporated SF plays an effective and crucial role in reinforcing the microstructure of slag/FA pastes.

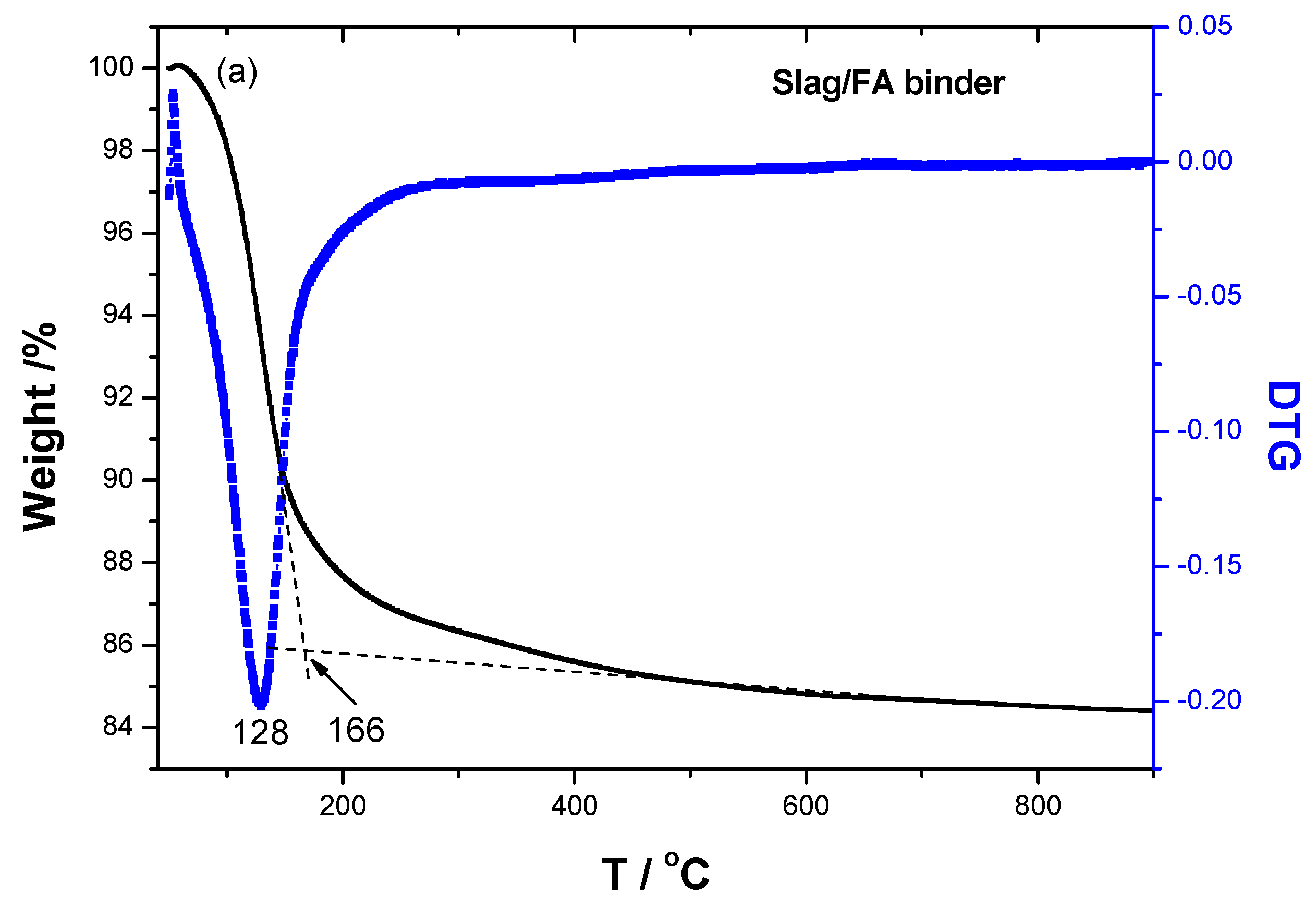

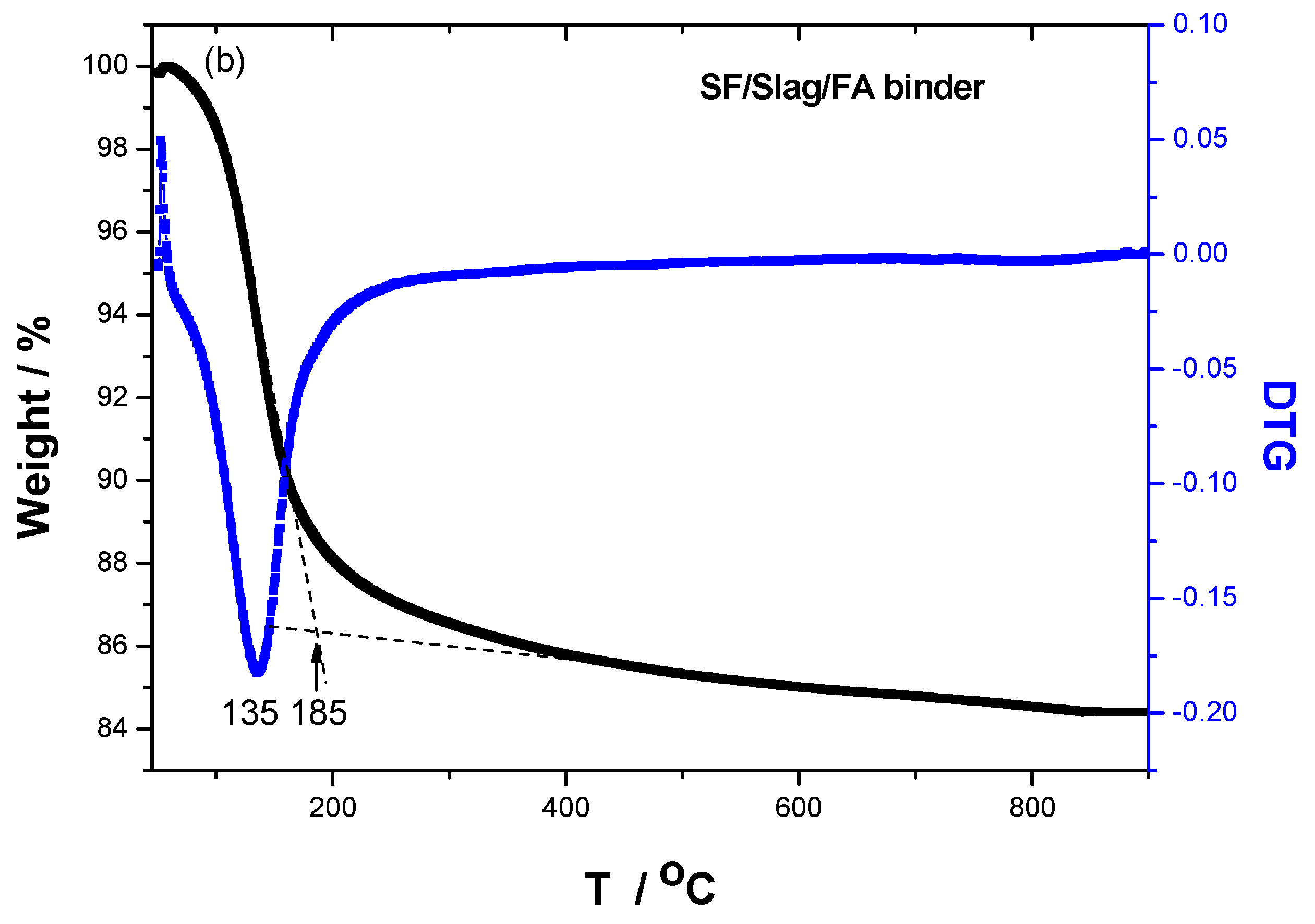

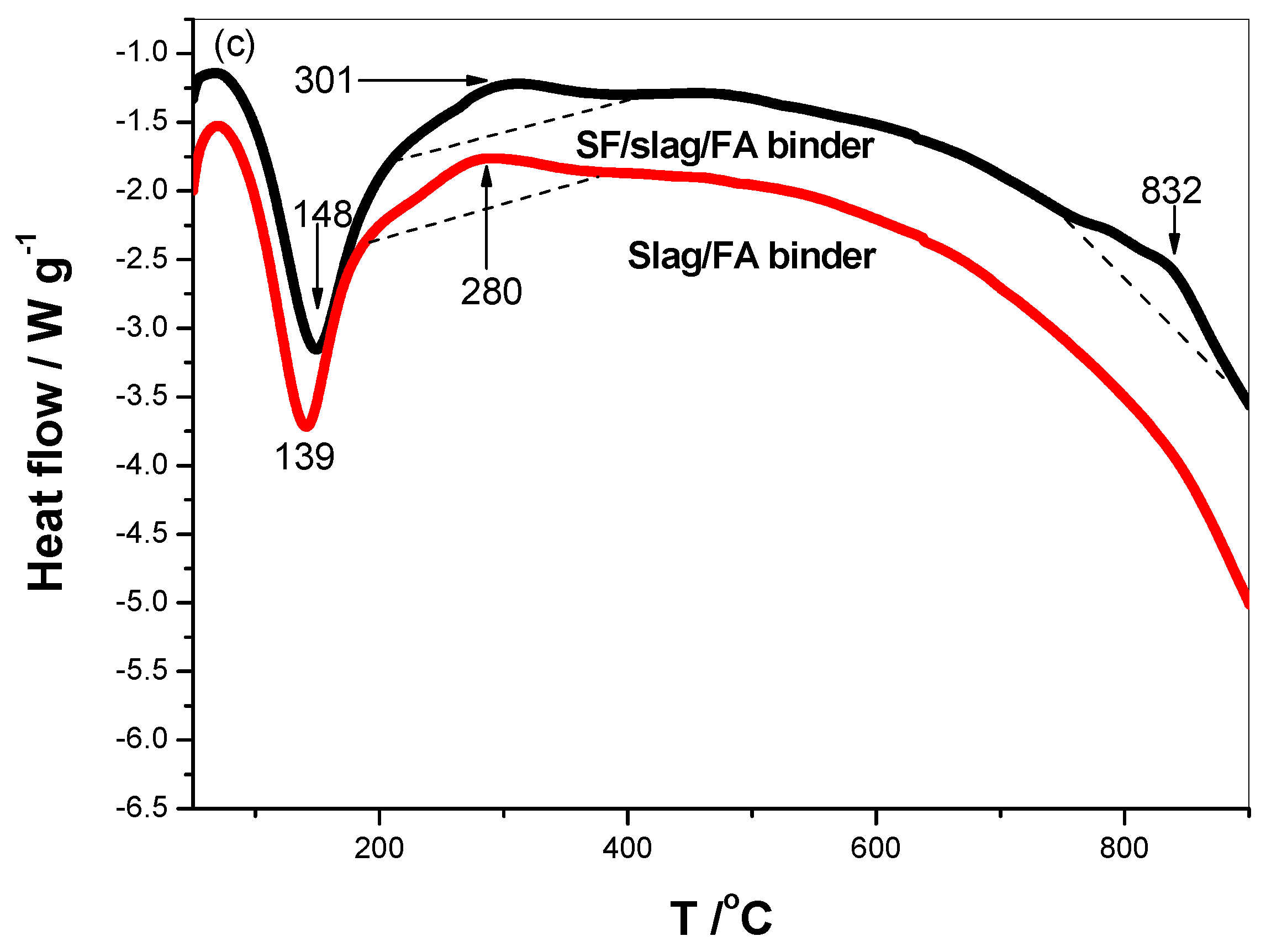

3.4. TG/DTG and DSC

The TG/DTG and heat flow curves of specimens are shown in

Figure 7, the peak shifts from 128 °C to 135 °C after the replacement of 10 wt% SF from the DTG curve, corresponding to the higher thermal stability. Meanwhile, the end temperature of mass loss rises from 166 to 185 °C from the TG in

Figure 7a,b. Because of the pozzolan and filling effects of SF, which could react with the Si-O-Al sols or Ca(OH)

2 to form more gels, and also it could insert or fill the space left by the geopolymerization [

8,

9].

The heat flow of the specimen reveals that the SF postpones the thermal exchange between the matrix and surrounding in the sub-high temperature, the endothermic peak shifts from 139 to 148 °C, and the tiny exothermic peak shifts from 280 to 301 °C as shown in

Figure 7c. It is reported that dehydration of specimens occurs below 300 °C, dehydroxylation derived from SiO

4 or AlO

4 tetrahedron occurred at about 500 °C, and on the order of 900 °C is required for complete decomposition of the C-S-H/C-A-S-H [

23]. It is appropriate to emphasize that no endothermic peak at around 450 °C caused by the dehydration of Ca(OH)

2 is detected, revealing that no Ca(OH)

2 formed [

24]. There is no endothermic peak at around 500 °C, presenting few SiO

4 or AlO

4 tetrahedrons. Interestingly, the tiny exothermic peak at 832 °C might be attributed to the melting of amorphous SiO

2 involved in SF.

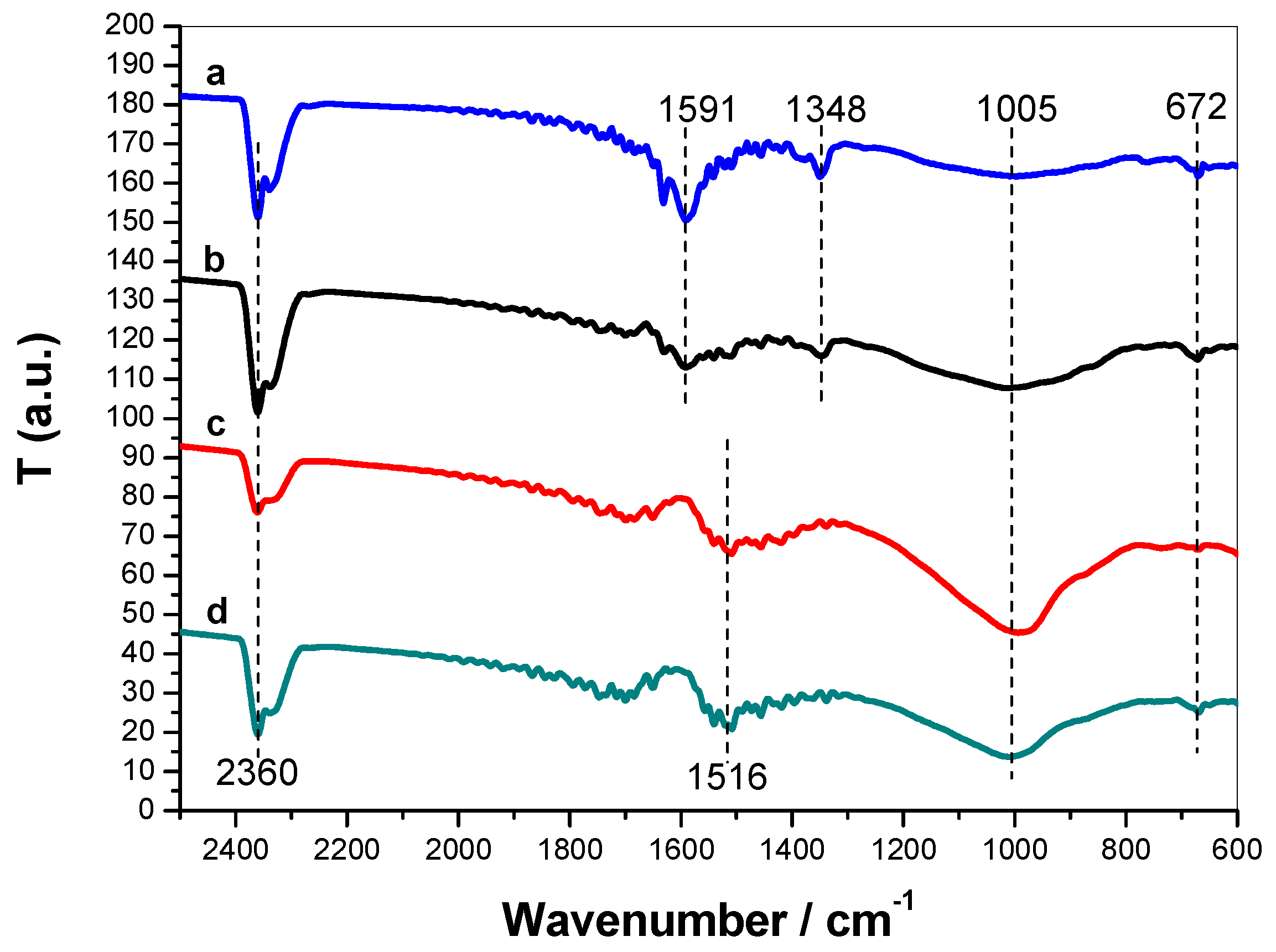

3.5. FTIR analysis

The band at 1005 cm

−1 is assigned to the oligomeric Si-O vibration [

25], which shifts to a lower wavenumber after incorporation of SF due to the increasing content of monomeric Si(OH)

4 as shown in

Figure 8c,d. The absorption peak at 2360 cm

−1 is attributed to the CO

2 in the environment, and the new peak at 1348 cm

−1 is assigned to vibration of [SiO

4]

4− and [AlO

4]

5− [

26], the peak at 672 cm

−1 is associated with M–O stretching vibrations (M=Si or Al) [

27]. It determines that the combination reactions between [SiO

4]

4− and [AlO

4]

5− occur during the heat treatment of 1200 °C.

4. Discussions

4.1. Mechanical properties and elevated temperatures

During the sub-high temperature, the pozzolan and filling effects of SF could promote the formation and transformation of amorphous silicates within the slag/FA binder, which is beneficial for the enhancement of mechanical properties. The amorphous SiO

2 involved in the SF is a typical forming agent of the network, the enrichment of Si(OH)

4 accelerates the forming of a silicate network by extending Si–O–Si bonds and creating bridging oxygen groups, which could trap the Ca

2+ for equilibrium charge. Actually, a moderate temperature treatment (⩽100 °C) may enhance the tensile properties of FA/cement binder due to the formation of more micro-cracks [

28].

When the temperature is above 800 °C, the mechanical strength of specimens suffers a dramatic drop. It is in agreement with Su [

29], implying that the heat treatment at about 800 °C is fatal for geopolymer. On the other hand, replacement with 10 wt% SF lowers the CaO/SiO

2 and Al

2O

3/SiO

2 molar ratios, which are 0.297 and 0.528, and that of the specimen without SF are 0.325 and 0.638 according to the chemical composition. The former holds a lower melting point and a higher deformation and attains a denser structure at 1200 °C. Wu et al [

30] suggest that lower CaO/SiO

2 and Al

2O

3/SiO

2 could enhance the viscosity in the system of SiO

2–Al

2O

3–CaO–MgO–Na

2O–K

2O. A lower melting point induced by substitution with 10 wt% SF promotes the increasing content of silicate melts, which could “seal” the cracks, improving the temperature-induced dehydration, dehydroxylation, and thermal incompatibility [

31], as well as the stress induced by varying degrees of shrinkage within matrix during the cooling process [

32].

4.2. Microstructure and elevated temperatures

Because the dehydration of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) occurs at 135–150 [

33], the SF could react with activated calcium oxide or Ca(OH)

2 and form C–S–H, leading to a denser and compact micro-structure, presenting a right shift of endothermic peak form the result of DTG, as well as increases in the mechanical properties. Meanwhile, an empirical relationship between the flexural strength and porosity (

p) is shown in Equation (1), where

σ0 and n are two constants determined experimentally [

34]. It follows that the flexural strength decreases exponentially with porosity. The replacement with SF favors a lower porosity and an increase in the pore volume of 0.2~3μm, as well as retardance of water evaporation due to denser structures [

35].

During the heat treatment of sub-high temperature, the mechanical properties are improved due to the enhanced geopolymerization further within the slag/FA paste matrix, with “right shifts” of mass loss peak and the endothermic peak of heat flow, leading to the denser and smooth fracture surface of microscopic morphology.

Because the SF begins to fuse at 1100 °C and forms a viscous liquid phase [

36]. However, when the specimen is exposed to 1200 °C heat treatment for 2h, the melting of the amorphous silicates at 1000~1100 °C occurs, which boosts a bloating effect within the matrix. While the specimen without SF possesses little melt, based on the tension induced by the escaping O

2, which promotes more cracks and accelerates a fast deterioration of the matrix, matching the lower flexural strength. Tsai et al. [

37] find that bloating effect occurs in municipal solid waste, and the finding of our research is amorphous SiO

2 lowers the melting point, which boosts the reaction between [SiO

4]

4− and [AlO

4]

5− and the formation of labradorite. As a kind of phase change material, the bloating SF holds beneficial effects of crack blunting and twisting [

38] as a liquid phase.

On the whole, SF plays a strengthening role in the slag/FA paste due to the filling effect and pozzolan reactivity during the sub-high temperature. The filling effect could insert the gap or holes and form micro-cracks, and pozzolan reactivity promotes more amorphous gels through geopolymerization, which favors the increasing pore volume of 0.2~3 μm, resulting in a continuous increase in the mechanical properties, favoring “right shifts” of endothermic peak and the initial and final temperature of mass loss, presenting a denser and smooth fracture surface. Meanwhile, during the heat treatment above 850 °C, the substitution with 10 wt% SF diminishes the melting point of slag/FA binder, the unreacted SF is prone to fuse and transforms into a liquid phase with a certain viscosity, which could generate crack blunting and twisting, leading to the occurrence of bloating effect and a greater deformation, promoting the formation of labradorite between [SiO4]4− and [AlO4]5−, evidenced by the results of XRD.

5. Conclusions

The effect of silica fume on the microstructure of alkali-activated slag/FA pastes after exposure to elevated temperatures (150, 500, 850, and 1200 °C) is investigated by XRD, SEM, TG, MIP, and FTIR spectroscopy, the following conclusions are drawn.

(1) Due to the filling and pozzolan effect, the replacement with 10 wt% SF promotes the increasing pore volume of 0.2~3 μm during the sub-high temperature, leading to a continuous increase in the mechanical properties, “right shifts” of endothermic peak and the initial-final temperature of mass loss, presenting a denser and smooth fracture surface.

(2) During the elevated temperature above 850 °C, the transformation of gehlenite and labradorite occurs. When the specimen is subjected to the exposure of 1200 °C, due to the formation of a liquid phase from the unreacted SF altogether with the amorphous silicates, the bloating effect occurs, leading to a greater deformation and enhancement of restructuring involved in the [SiO4]4− and [AlO4]5−.

References

- Habert, G.; Lacaillerie, J.B.; Roussel, N. An environmental evaluation of geopolymer based concrete production: Reviewing current research trends. Journal of Cleaner Production 2011, 19, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wen, Q.; Lu, X.; Xiao, K.; Ekberg, C.; Zhang, S. Application of geopolymers for treatment of industrial solid waste containing heavy metals: State-of-the-art review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 390, 136053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmal, A.; Khouchani, O.; El-Korchi, T.; Tao, M.; Walker, H.W. Bioinspired brick-and-mortar geopolymer composites with ultra-high toughness. Cement and Concrete Composites 2023, 137, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, A.N.; Murmu, A.L.; Alomayri, T. Physico-Mechanical and thermal behavior of prolong heat Cured geopolymer blocks. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 370, 130309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.E.; Monteiro, P.J.; Jun, S.S.; Choi, S.; Clark, S.M. The evolution of strength and crystalline phases for alkali-activated ground blast furnace slag and fly ash-based geopolymers. Cement and Concrete Research 2010, 40, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, J.; Bai, E.; Li, W. Systematic study on the basic characteristics of alkali-activated slag-fly ash cementitious material system. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 29, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithiraputhiran, S.; Neithalath, N. Isothermal reaction kinetics and temperature dependence of alkali activation of slag, fly ash and their blends. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 45, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, A.; Öz, A.; Bayrak, B.; Kaplan, G.; Aydın, A.C.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Performance evaluation and cost analysis of prepacked geopolymers containing waste marble powder under different curing temperatures for sustainable built environment. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2023, 192, 106910. [Google Scholar]

- Hossein, H.A.; Hamzawy, E.M.; El-Bassyouni, G.T.; Nabawy, B.S. Mechanical and physical properties of synthetic sustainable geopolymer binders manufactured using rockwool, granulated slag, and silica fume. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 367, 130143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnaník, P.; Bayer, P.; Rovnaníková, P. Characterization of alkali activated slag paste after exposure to high temperatures. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 47, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.; Bai, Y.; Basheer, P.; Collier, N.; Milestone, N. Chemical and mechanical stability of sodium sulfate activated slag after exposure to elevated temperature. Cement and Concrete Research 2012, 42, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Khalil, M.H. A preliminary study of alkali-activated slag blended with silica fume under the effect of thermal loads and thermal shock cycles. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 40, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilar, F.A.; Ganachari, S.V.; Patil, V.B.; Reddy, I.N.; Shim, J. Preparation and validation of sustainable metakaolin based geopolymer concrete for structural application. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 371, 130688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, E.; Dal Maschio, R. Glass–ceramics from vitrified sewage sludge pyrolysis residues and recycled glasses. Waste Management 2011, 31, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, E.; Esposito, L.; Rambaldi, E.; et al. Sintered esseneite–wollastonite–plagioclase glass–ceramics from vitrified waste. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2009, 29, 2921–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segui, P.; Aubert, J.E.; Husson, B.; Measson, M. Utilization of a natural pozzolan as the main component of hydraulic road binder. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 40, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, E.; Bonomo, E.; Dattoli, A. Optimisation of sintered glass–ceramics from an industrial waste glass. Ceramics International 2010, 36, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Kayali, O. The fate of water in fly ash-based geopolymers. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 39, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G. Structural characterization of glass–ceramics made from fly ash containing SiO2–Al2O3–Fe2O3–CaO and analysis by FT-IR–XRD–SEM methods. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2012, 1019, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathossi, C.; Pontikes, Y. Effect of firing temperature and atmosphere on ceramics made of NW Peloponnese clay sediments. Part I: Reaction paths, crystalline phases, microstructure and colour. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2010, 30, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ma, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Shen, S.; Liu, Z. Study of extracting alumina from high-alumina PC fly ash by a hydro-chemical process. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 161, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikal, M.; El-Didamony, H.; Sokkary, T.; Ahmed, I. Behavior of composite cement pastes containing microsilica and fly ash at elevated temperature. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 38, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, M.; Sanjayan, J.G. Behavior of combined fly ash/slag-based geopolymers when exposed to high temperatures. Fire Mater. 2010, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Sadek, D.M.; Hassan, H.A. An investigation on blast-furnace slag as fine aggregate in alkali-activated slag mortars subjected to elevated temperatures. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 112, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yan, W.; Duan, J. Polymerization of silicate on TiO2 and its influence on arsenate adsorption: An ATR-FTIR study. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2015, 469, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penilla, R.; Bustos, A.; Elizalde, S. Zeolite synthesized by alkaline hydrothermal treatment of bottom ash from combustion of municipal solid wastes. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2003, 86, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lin, Q.; Lu, S.; He, Y.; Liao, G.; Ke, Y. Effect of CaO/SiO2 ratio on the preparation and crystallization of glass-ceramics from copper slag. Ceramics International 2014, 40, 7297–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, V.C. Mechanical performance of ECC with high-volume fly ash after sub-elevated temperatures. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 99, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Xu, J.; Ren, W. Mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete exposed to dynamic compression under elevated temperatures. Ceramics International 2016, 42, 3888–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yazhenskikh, E.; KlausHack, E.; et al. Viscosity model for oxide melts relevant to fuel slags. Part 1: Pure oxides and binary systems in the system SiO2–Al2O3–CaO–MgO–Na2O–K2O. Fuel Processing Technology 2015, 137, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Kodur, V.; Wu, B.; Cao, L.; Wang, F. Thermal behavior and mechanical properties of geopolymer mortar after exposure to elevated temperatures. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 109, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.-X.; Liu, J.-H. Effects of Fe2O3 content on microstructure and mechanical properties of CaO−Al2O3−SiO2 system. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Sun, W.; Xiao, H.; et al. Effects of nano-SiO2 particles on the mechanical and microstructural properties of ultra-high performance cementitious composites. Cement & Concrete Composites 2015, 56, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, N.; Ru, H.; Liang, B.; Chen, D. Mechanical properties and toughening mechanisms of silicon carbide nano-particulate reinforced Alon composites. Materials Science and Engineering A 2012, 538, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Xu, D.L.; Li, S. Mechanical performance and hydration mechanism of geopolymer composite reinforced by resin. Materials Science and Engineering 2010, A257, 6574–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, F.; Guo, Q.; Yu, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, F. Characterization of the melting behavior of high-temperature and low-temperature ashes. Fuel Processing Technology 2015, 134, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-C.; Wang, K.-S.; Chiou, I.-J. Effect of SiO2–Al2O3–flux ratio change on the bloating characteristics of lightweight aggregate material produced from recycled sewage sludge. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2006, B134, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Manari, S.; Aguayo, M.; Santos, K.; Oey, T.; Wei, Z.; Falzone, G.; Neithalath, N.; Sant, G. On the feasibility of using phase change materials (PCMs) to mitigate thermal cracking in cementitious materials. Cement & Concrete Composites 2014, 51, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).