1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive type of primary brain tumor, with approximately 12,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States [

1]. Despite advances in surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, GBM remains highly lethal due to its rapid progression and resistance to conventional treatments. The median survival time for patients with GBM remains poor, typically ranging from 12 to 18 months [

2]. Temozolomide (TMZ), an oral DNA-alkylating agent, which can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), is the standard chemotherapeutic used in GBM treatment [

2]. By interfering with DNA replication in cancer cells, TMZ induces cell death and helps slow tumor growth. However, its clinical effectiveness is often limited by the development of resistance mechanisms within tumors. As a result, TMZ rarely extends patient survival beyond 15 months [

2]. The emergence of TMZ resistance poses a major challenge in GBM therapy, highlighting the urgent need for novel, potent small molecules capable of effectively targeting GBM cells. Developing such agents to overcome the limitations of current treatments, particularly TMZ resistance, is a critical focus in GBM research.

Microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs) have become a significant area of focus in the development of anticancer drugs. Microtubules are dynamic heteropolymers composed of α- and β-tubulin subunits [3-5]. These structures play a pivotal role in various cellular processes, including maintaining cell shape, enabling intracellular transport, and facilitating cell division [

6]. MTAs disrupt polymer dynamics, triggering cell cycle arrest that leads to cell death. Thus, microtubules are a good target for anticancer therapy. Three major binding sites have been identified in tubulins: the taxane [

7], vinca alkaloid [

8], and colchicine sites [

9]. A broad variety of small molecule tubulin-binding agents have been developed as therapeutics for a variety of other cancers. Hence, developing novel compounds that can induce cell death without resistance is crucial for improving outcomes in GBM therapy. In this study, we have selected a series of MTAs that were developed in our laboratory for melanoma, breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers and we selected nine of the most potent microtubule inhibiting molecules to test against two glioblastoma cell lines.

2. Results

2.1. MTAs reduce GBM cell viability in vitro.

Over the past decade, our laboratory has developed a series of small-molecule tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site, potentially offering therapeutic advantages over other MTAs [

10,

11,

12,

13]. To advance these compounds as pharmacological agents against glioblastoma (GBM), we focused on our most potent derivatives containing pyrimidine and dihydroquinoxalinone moieties with diverse functional groups. From this library, nine analogs (compounds 1–9,

Table 1) were selected and tested for their effects on the viability of two GBM cell lines (U251 and LN229) using the Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, a standard method to measure cytotoxicity in cell-based assays. TMZ, the current anti-glioma drug, was included as an internal control.

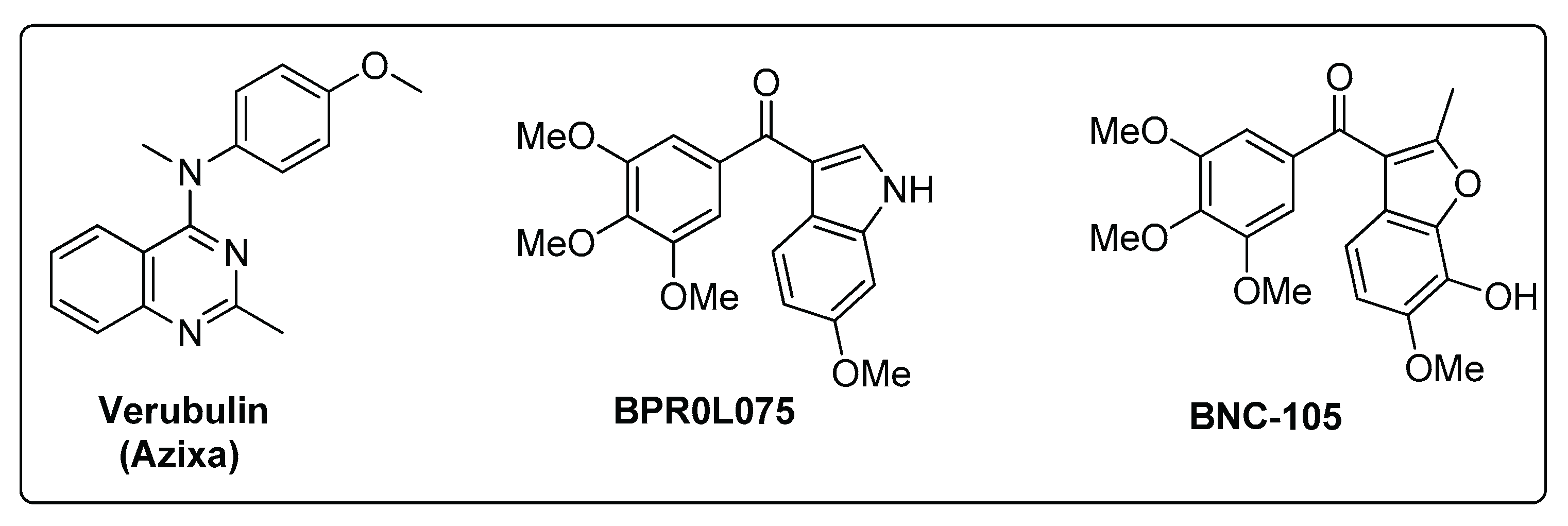

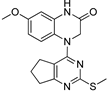

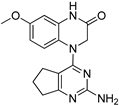

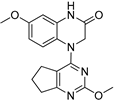

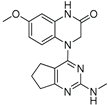

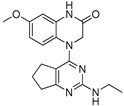

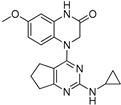

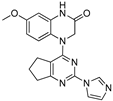

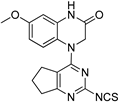

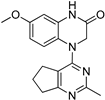

Based on the structures of previously characterized compounds such as Verubulin, BPR0L075, and BNC105 (

Figure 1), which demonstrated preclinical efficacy, we hypothesized that the methoxy (OMe) group on the aromatic ring is critical for biological potency. We selected compound 3, which contains this group, and found it exhibited moderate cytotoxic activity with IC₅₀ values of 15.6 and 80.1 nM in the two glioma cell lines, respectively. Modification of the OMe group in compound 3 to a thioether (SMe, compound 1) markedly increased potency, with IC₅₀ values of 1.88 and 2.49 nM in the respective cell lines.

Encouraged by these results, we then examined various pyrimidine analogs with primary (1°) and secondary (2°) amine substitutions at the 2-position of the pyrimidine ring. Interestingly, secondary amine-bearing pyrimidine analogs showed strong potency. Compound 4 exhibited IC₅₀ values of 2.09 and 2.36 nM, compound 5 had 3.1 and 3.15 nM, and compound 6 showed 0.81 and 5.82 nM in the two glioma cell lines, respectively. In contrast, the primary amine analog (compound 2) was biologically inactive (IC₅₀ > 1000 nM). Incorporation of nitrogen at the 2-position as part of a heterocyclic ring improved potency, as demonstrated by compounds 4 and 5. Additionally, derivatives containing isothiocyanate and methyl groups (compounds 8 and 9) displayed significant cytotoxic activity (IC₅₀ values ranging from 2.09 to 5.71 nM). The IC₅₀ values for all compounds are summarized in

Table 1.

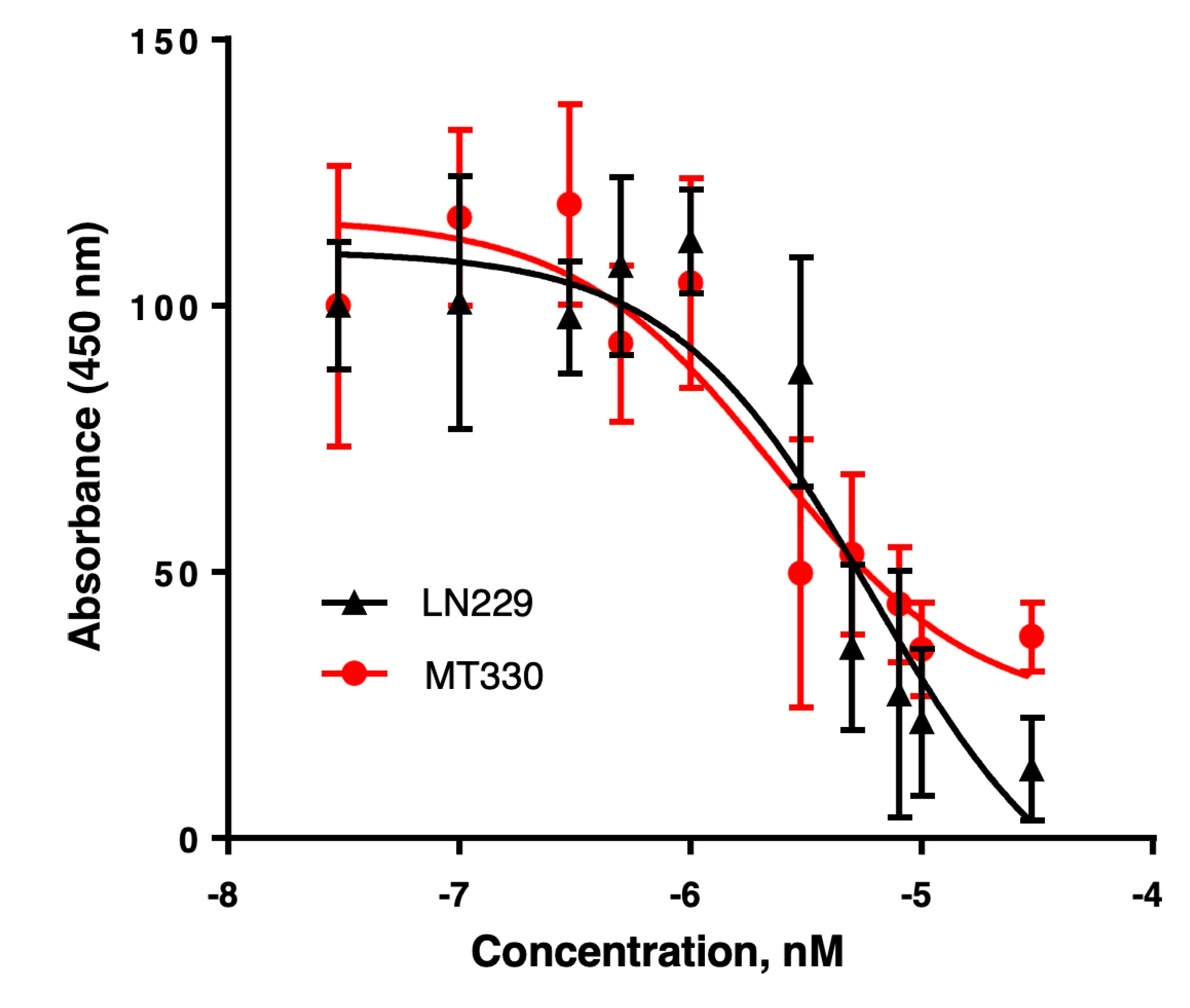

For reference, TMZ, the standard DNA-alkylating agent used to treat GBM, required concentrations at least 1000-fold higher to induce cytotoxicity (IC₅₀ of 20–400 µM). This study revealed that most of the tested compounds induced cytotoxicity in GBM cells with nanomolar potency. Based on these promising results, we selected compound 4 for further investigation of its anticancer activity. The complete dose-response curve for compound 4 in the SRB assay is shown in

Figure 2.

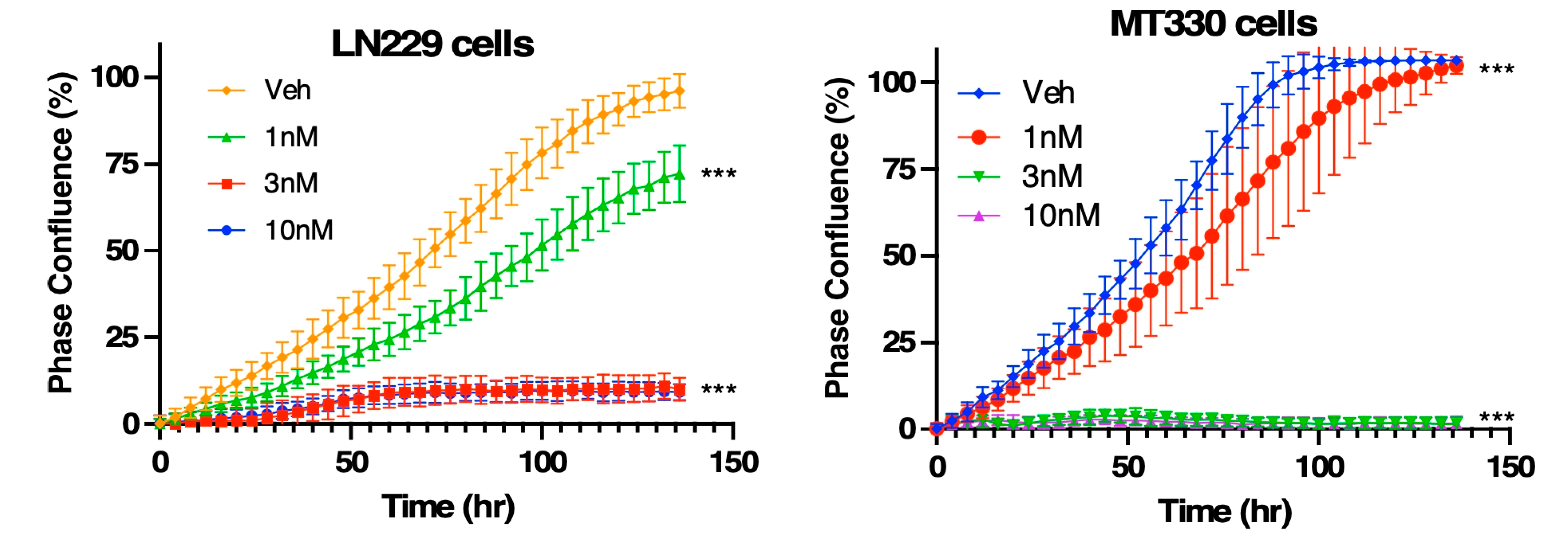

2.2. Compound 4 reduces the proliferation of GBM cells in vitro.

We next employed the IncuCyte Live-Cell Imaging System to monitor GBM cell proliferation and morphology in real time over a 5-day period. LN229 and MT330 GBM cells were seeded into 96-well plates and treated the following day with compound 4 at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 nM. MT330 cells were also examined because they are a clinically relevant

in vivo model of GBM tumorigenesis [

14]. As shown in

Figure 3, vehicle-treated LN229 and MT330 cells rapidly entered a rapid exponential growth phase. However, treatment with 1 nM compound 4 significantly reduced cell proliferation compared to controls. At 3 and 10 nM, both cell lines exhibited complete growth arrest within 48 hours of treatment initiation, with a more pronounced response observed in MT330 cells. Photomicrographs taken during this time revealed morphological changes in both cell lines treated with compound 4 suggestive of apoptosis.

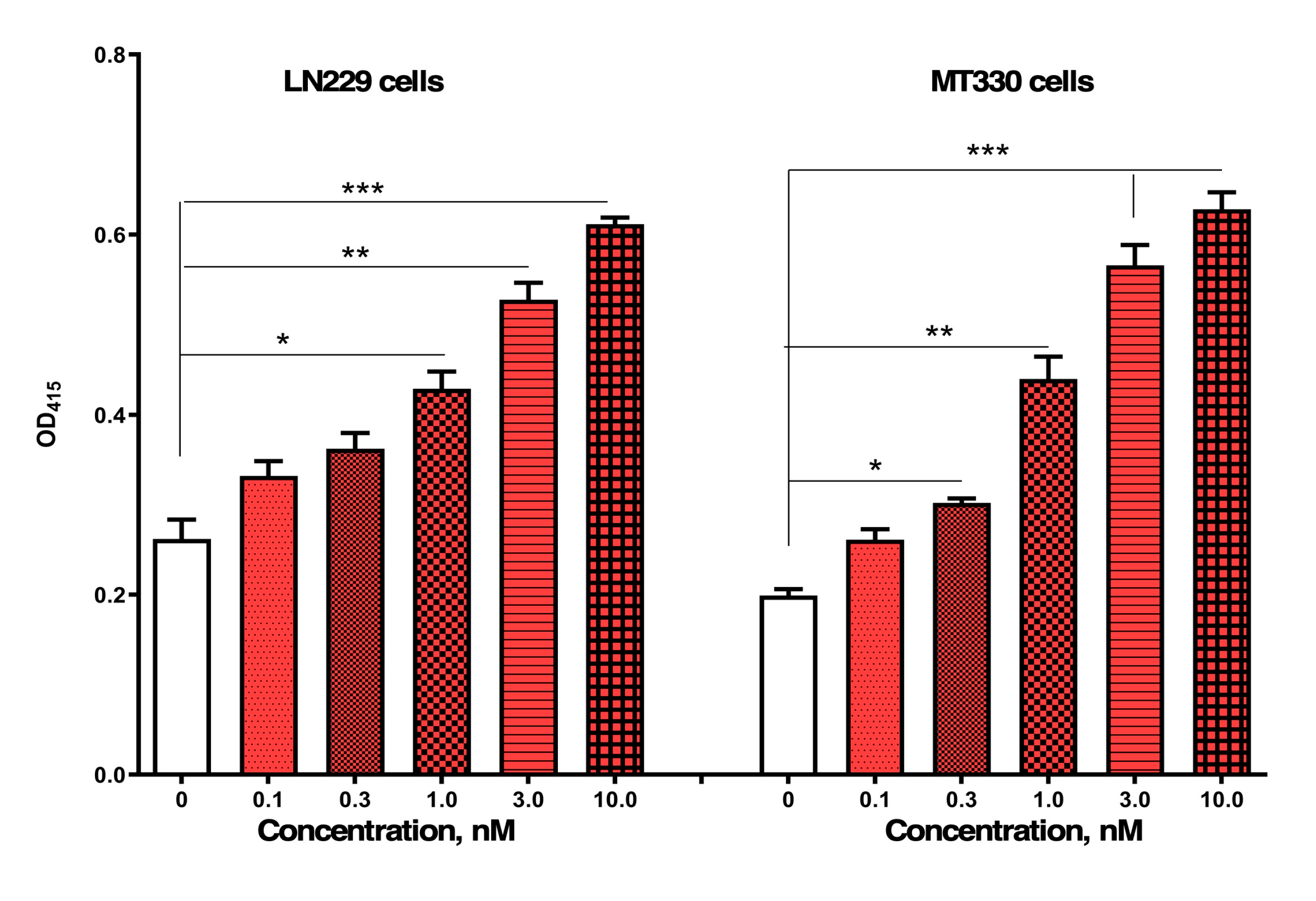

2.3. Compound 4 induces the apoptosis of GBM cells in vitro.

We next investigated whether the reduction in GBM cell viability following compound 4 treatment was attributable in part to the induction of apoptosis. LN229 and MT330 GBM cells were treated with compound 4 for 48 hours, after which apoptosis was assessed using a highly sensitive, cell death ELISA that detects nucleosome release from apoptotic cells, as previously described [

14]. As shown in

Figure 4, compound 4 induced apoptosis in LN229 GBM cells in a dose-dependent manner, with significant activity observed at concentrations between 1 and 3 nM, which is consistent with its IC₅₀ values from SRB assays. In addition to LN229 cells, we also examined MT330 GBM cells. Similar to LN229, MT330 cells exhibited a robust, dose-dependent apoptotic response to compound 4. However, TMZ, which is the standard-of-care chemotherapy for GBM, does not induce apoptosis in either LN229 or MT330 GBM cells even at micromolar concentrations [

15], underscoring the distinct and potent pro-apoptotic activity of compound 4.

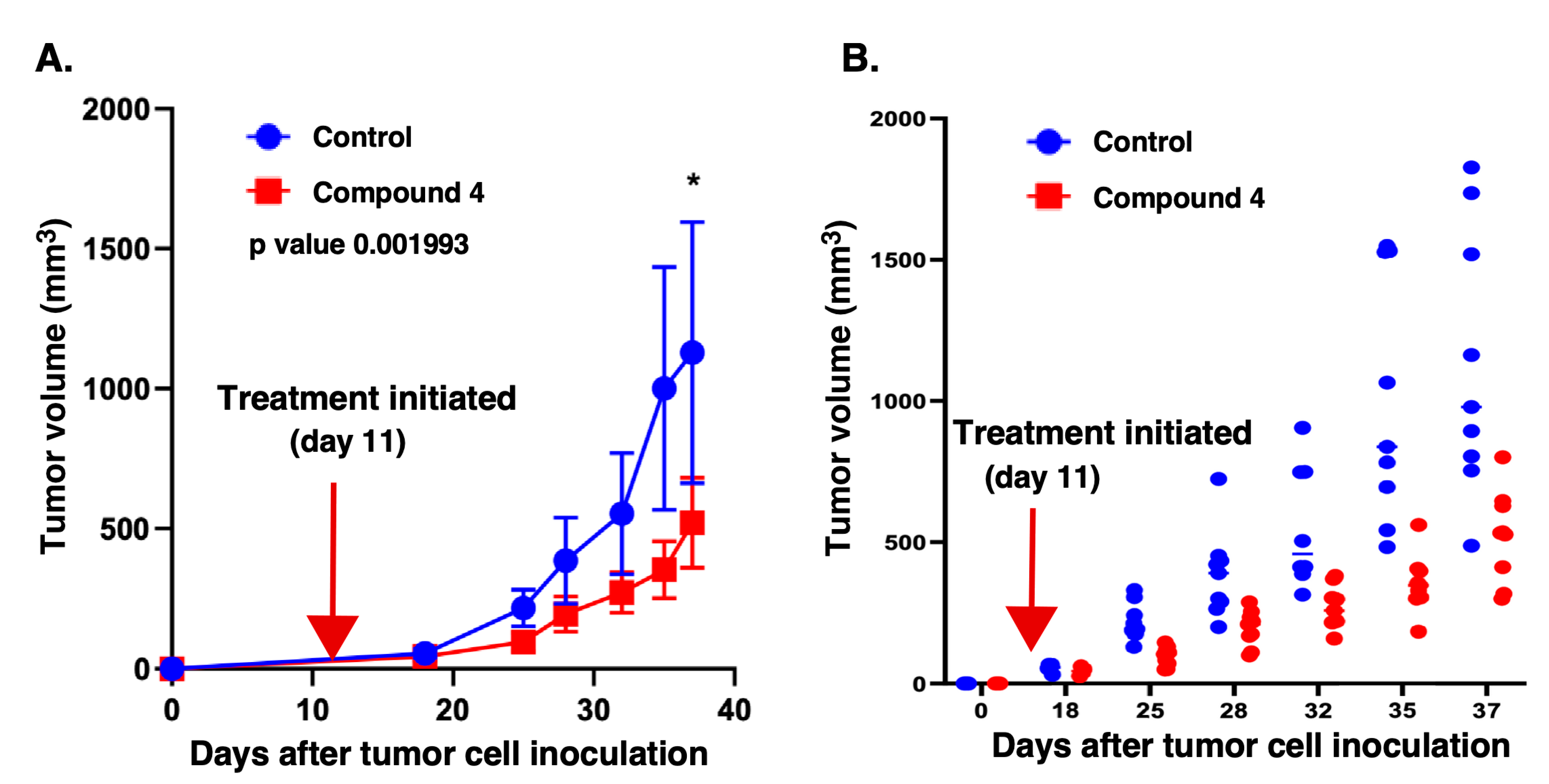

2.4. Compound 4 exhibits potent anticancer activity against GBM tumors in vivo

We have demonstrated that compound 4 significantly reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis in GBM cells in vitro, suggesting its potential as an anticancer agent. To further evaluate its efficacy, we tested compound 4 in a GBM xenograft model. MT330 GBM cells were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of immunocompromised mice. Eleven days post-engraftment, mice were randomized into two groups: (a) vehicle control (PEG-saline mixture), and (b) compound 4-treated (5 mg/kg, administered intraperitoneally twice weekly). Treatment continued until a humane endpoint was reached in either group.

Tumor volumes were measured two times a week using calipers. As shown in

Figure 5A, throughout the 25-day time course of treatment with compound 4 there was a significant reduction in mean tumor volume compared to controls. Individual tumor volumes throughout the time course of drug treatment are depicted in

Figure 5B, which further confirmed markedly reduced growth in the compound 4-treated group.

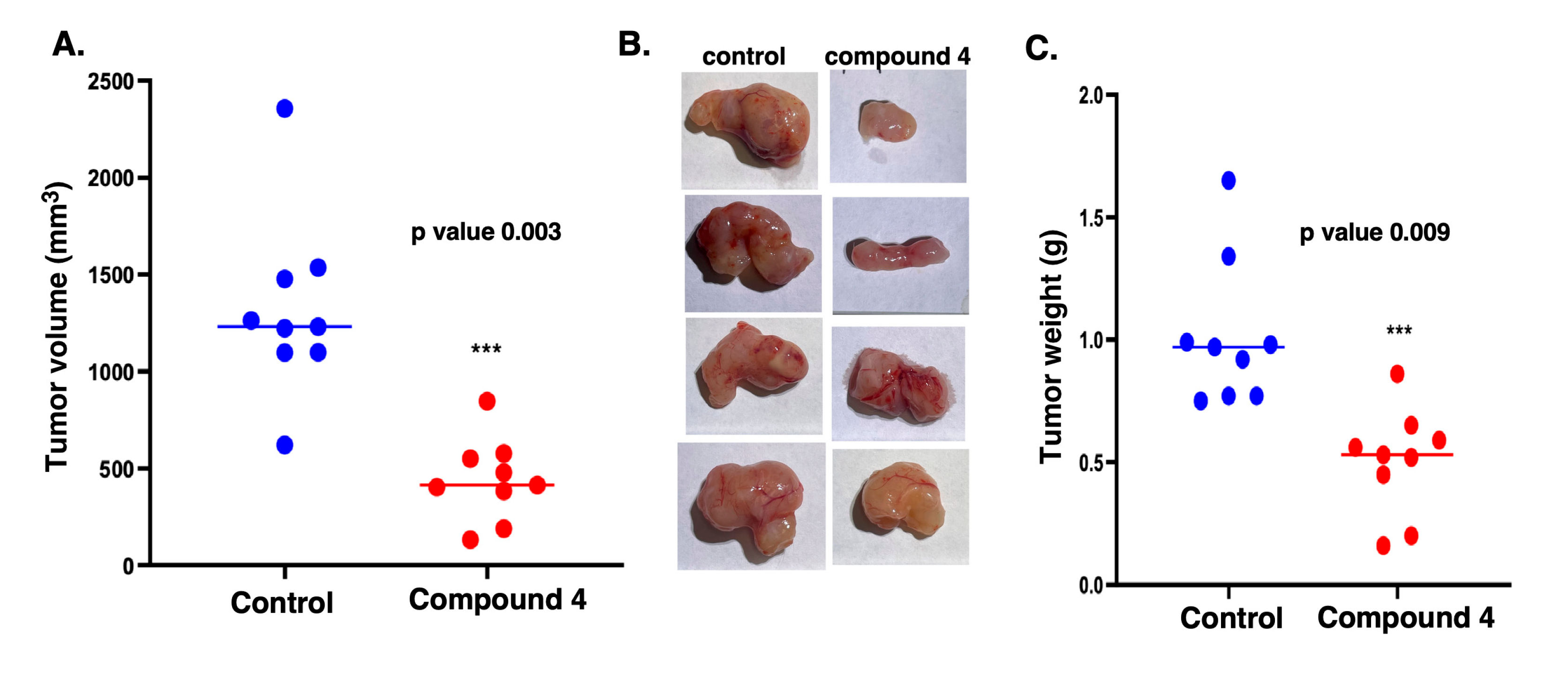

At day 36 post-injection, several mice in the control group reached the humane endpoint (tumor volume equal to or greater than 1000 mm³), whereas none of the compound 4-treated mice did. At this time point, all mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised, measured, and weighed.

Figure 6A shows the dot plots of the tumor volumes in individual mice showing the trend of smaller tumors in compound-4 treated mice. The average tumor size in the compound 4-treated group being 441.3 mm³, compared to 1333.6 mm³ in the control group—a 66% reduction.

Figure 6B visually illustrates the difference in tumor size with those in compound 4-treated mice being substantially smaller than those from control mice. Furthermore, as shown in Fig 6C the weight of the tumors was markedly lower in compound 4-treated mice as compared to control (0.50 g versus 1.12g)

Taken together, the results in

Figure 5 and 6 clearly demonstrate that compound 4 exhibits potent anticancer activity against GBM tumors

in vivo.

3. Discussion

Gliomas—particularly high-grade variants such as GBM—are among the most aggressive and treatment-resistant tumors of the central nervous system. Despite advances in surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, including the use of temozolomide (TMZ), the prognosis for GBM patients remains poor, with median survival rarely exceeding 15 months [

10]. A major challenge in treating gliomas is their highly proliferative, invasive, and heterogeneous nature, compounded by the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which restricts effective drug delivery to tumor sites [

11].

In recent years, microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs) have emerged as a promising class of chemotherapeutics capable of disrupting cancer cell division, migration, and intracellular transport. These agents act by binding to tubulin—the structural component of microtubules—thereby interfering with microtubule dynamics essential for mitotic spindle formation and cellular integrity [

11]. Given the pivotal role of microtubules in glioma cell proliferation and migration, tubulin inhibitors offer potential to address critical therapeutic gaps in glioma treatment. However, translating the success of tubulin inhibitors from other cancer types to glioma therapy has proven difficult. Challenges such as limited BBB penetration, neurotoxicity, and the molecular heterogeneity of glioma cells have hindered clinical efficacy. Several tubulin inhibitors have demonstrated anticancer activity. For instance, Verubulin (MPC-6827, Azixa), a pyrimidine-derived small molecule, inhibits microtubule formation, crosses the BBB, and induces mitotic arrest and apoptosis in various cancer cell lines. Nevertheless, Verubulin failed in phase II clinical trials for recurrent GBM due to insufficient efficacy and unacceptable toxicity [

12]. Similarly, BPR0L075 (SCB01A) and BNC105 showed preclinical efficacy in multiple cancer models, including GBM, but did not achieve success in clinical trials [

13,

14,

15].

Recent studies have continued to explore colchicine-binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) as viable alternatives for GBM therapy. Liu et al. reported that 2-aryl-4-amide-quinoline derivatives exhibited potent antiproliferative activity and favorable pharmacokinetics in breast cancer models, suggesting broader applicability of strategies [

10]. Weng et al. emphasized the structural flexibility and strong cytotoxicity of CBSIs, positioning them as a mainstream approach for overcoming multidrug resistance [

11]. In GBM-specific research, Manzoor et al. identified pyrimidine-based CDK6 inhibitors with high binding affinity and stability, reinforcing the therapeutic relevance of pyrimidine scaffolds [

12]. Byrne et al. developed

pyrazolopyrimidinone swith selective cytotoxicity against GBM cells in vitro, further validating nitrogen-containing heterocycles as promising platforms for drug development [

13].

In this study, we targeted the colchicine-binding site on tubulin with a focused library of pyrimidine- and dihydroquinoxalinone-based analogs. Compound 4, a pyrimidine analog with a secondary amine, emerged as the lead candidate, demonstrating nanomolar IC₅₀ values and superior efficacy compared to TMZ. Structural modifications—particularly secondary amine substitutions and heterocyclic enhancements—were key contributors to its cytotoxic potency.

Live-cell imaging revealed that compound 4 rapidly inhibited GBM cell proliferation, while apoptosis assays confirmed a robust, dose-dependent induction of cell death at concentrations far lower than those required for TMZ. Importantly, in vivo studies using a GBM xenograft model showed that compound 4 reduced tumor volume by 66% and tumor weight by over 50%, without apparent toxicity.

Taken together, these findings validate colchicine-site tubulin inhibition as a compelling strategy for GBM treatment and support the continued preclinical development of compound 4. Its potent activity, favorable pharmacodynamics, and ability to overcome TMZ resistance position it as a strong candidate for future translational and clinical studies.

4. Experimental methods

4.1. Biological reagents and cell cultures

U251 and LN229 GBM cell lines (ATCC, Manassas, VA), along with the MT330 cell line (Department of Neurosurgery, UTHSC), were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) analysis.

4.2. SRB assays

LN229 and U251 GBM cells were plated at a density of 5,000 to 10,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate and treated with various concentrations of MTAs. After 4 to 5 days of incubation, cells were fixed with trichloroacetic acid, and the plates were washed thoroughly. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) dye was then added to stain the cellular proteins. Following extensive washing to remove unbound dye, the bound SRB was solubilized, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm on a plate spectrophotometer. IC₅₀ values were determined using GraphPad Prism software.

4.3. Cell proliferation assays

For cell proliferation assays, LN229 and MT330 GBM cells were seeded at 2 × 10³ cells per well in 96-well plates. After 24 hours, plates were treated with or without compound 4 and placed in the Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI). Cells were incubated at 37°C, and proliferation was monitored over time by cell confluency using the manufacturer’s software tools.

4.4. Cell death assays

For cell death assays, LN229 and MT330 GBM cells were seeded at 1 × 10⁴ cells per well in 48-well plates. Following 2 days of drug treatment, apoptosis in the adherent cell population was assessed using the Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay quantifies cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments, a hallmark of apoptotic cell death [

14].

4.5. Mouse xenograft experiments

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UTHSC (Protocol #17-098). Xenograft tumors were established in five-week-old female NOD.Cg-

Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ immunocompromised mice (Jackson Laboratory) . For xenograft studies, MT330 cells (5 × 10

5) were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of mice, as previously described [

15]. Once tumors became palpable (usually within 10 to 14 days), mice were randomly assigned to the two treatment groups (9 mice per group) and received intraperitoneal injections of compound 4 (5 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (DMSO) twice per week. Tumor volumes were measured weekly using calipers (calculated as width

2 x length ÷ 2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.M., L.M.P., and W.L.; methodology, S.P., D.H.; validation, M.D., J.I.J., A.S., H.R.K., D.N.P.; formal analysis, M.D., J.I.J., A.S., H.R.K., C.H.Y., D.N.P.; resources, S.P., D.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., L.M.P and D.D.M.; writing—review and editing, S.P., D.H., W.L.; D.D.M. and L.M.P.; supervision, D.D.M., W.L. and L.M.P.; project administration, D.D.M., W.L. and L.M.P.; funding acquisition, D.D.M., W.L. and L.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1CA281977> (L.M.P. and D.D.M.). Additional supports were provided by the NIH grants R01CA148706 and R01CA276152 (W.L. and D.D.M), and the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy Drug Discovery Center. The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH/NCI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (protocol code 23-0472, 10/19/2024) for studies involving animals.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The animal work herein was supported by the Animal Models Shared Resource Core of UTHSC Center for Cancer Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBM |

Glioblastoma |

| TMZ |

Temozolomide |

| MTAs |

Microtubule-targeting agents |

| IC50

|

half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| SRB |

Sulforhodamine B |

| NSG |

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ6+ |

References

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surawicz, T.S.; Davis, F.; Freels, S.; Laws, E.R., Jr.; Menck, H.R. Brain tumor survival: results from the National Cancer Data Base. J Neurooncol 1998, 40, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, M.A.; Wilson, L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumontet, C.; Jordan, M.A. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmanova, A.; Steinmetz, M.O. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, R.H. Microtubules: an overview. Methods Mol Med 2007, 137, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreu, J.M.; Barasoain, I. The interaction of baccatin III with the taxol binding site of microtubules determined by a homogeneous assay with fluorescent taxoid. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 11975–11984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.S.; Wolff, J. Localization of the vinblastine-binding site on beta-tubulin. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 14707–14711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ter Haar, E.; Rosenkranz, H.S.; Hamel, E.; Day, B.W. Computational and molecular modeling evaluation of the structural basis for tubulin polymerization inhibition by colchicine site agents. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 1996, 4, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shan, S.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, F.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Gui, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, C.; Ren, T.; et al. Mitophagy bridges DNA sensing with metabolic adaption to expand lung cancer stem-like cells. EMBO Rep 2023, 24, e54006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, W.; Meng, T.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, Y.; Fu, G.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Pan, R.; et al. Antibody-Exatecan Conjugates with a Novel Self-immolative Moiety Overcome Resistance in Colon and Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 950–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, H.; Khan, M.U.; Rehman, R.; Shabbir, C.A.; Ullah, M.I.; Ghanem, H.B.; Alameen, A.A.M.; Javed, M.A.; Ali, Q.; Haider, N. Identification and evaluation of pyrimidine based CDK6 inhibitors against glioblastoma using integrated computational approaches. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 25387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, K.; Bednarz, N.; McEvoy, C.; Stephens, J.C.; Curtin, J.F.; Kinsella, G.K. Development of Novel Anticancer Pyrazolopyrimidinones Targeting Glioblastoma. ChemMedChem 2025, e202500337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Sims, M.M.; Sacher, J.R.; Raje, M.; Deokar, H.; Yue, P.; Turkson, J.; Buolamwini, J.K.; Pfeffer, L.M. SS-4 is a highly selective small molecule inhibitor of STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation that potently inhibits GBM tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett 2022, 533, 215614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Yue, J.; Sims, M.; Pfeffer, L.M. The curcumin analog EF24 targets NF-kappaB and miRNA-21, and has potent anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).