1. Introduction

Imipridones represent a novel class of small molecule anticancer agents, with high oncotherapeutic potential.

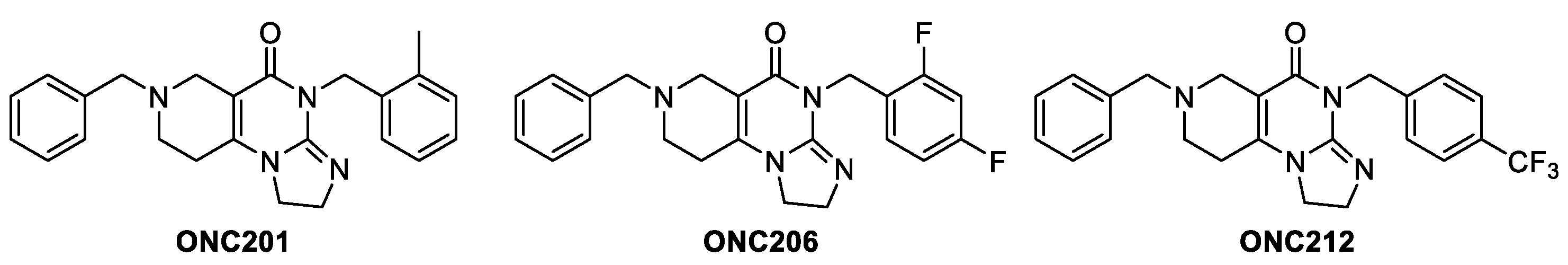

ONC201 is the first-in-class lead compound of the imipridone family, which is currently engaged in multiple clinical trials for solid and hematological malignancies, like gliomas, neuroendocrine tumors, multiple myeloma, breast cancer, endometrial cancer (

https://clinicaltrials.gov/) featuring wide therapeutic windows and an exceptional safety profile [

1]. Accordingly, the FDA has granted

ONC201 Fast Track Designation for the treatment of adult recurrent H3 K27M-mutant HGG, Rare Pediatric Disease Designation for treatment of H3 K27M-mutant glioma, and Orphan Drug Designations for the treatment of glioblastoma and malignant glioma. The anticancer activity of

ONC201 was originally identified in a target-agnostic screen searching for activators of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in tumor cells [

2]. Second-generation imipridones, such as

ONC206 and

ONC212 (

Figure 1) were also identified as highly potent anticancer agents [

3]. Compared to

ONC201,

ONC206 demonstrated improved inhibition of cell migration and was transferred to phase I trials in treatment of diffuse midline gliomas, while

ONC212 was tested in >1000 human cancer cell lines

in vitro featuring the lowest efficient doses in this series, typically in nanomolar range, and evaluated for safety and antitumor efficacy

in vivo. Exhibiting rapid pharmacokinetics,

ONC212 selectively kills tumor cells and has broad-spectrum preclinical activity across both solid tumors and hematological malignancies, including pancreatic cancer and leukemias prioritized for clinical indications [

4].

Molecular targets of

ONC201 and other imipridones have been intensively investigated in the past few years in order to clarify their mechanisms of action. Besides inducing TRAIL,

ONC201 also upregulates the cell surface TRAIL receptor, death receptor 5 (DR5) [

5,

6], acts as a selective antagonist of dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) [

3] and has been identified as an allosteric agonist of mitochondrial protease caseinolytic protease P (ClpP) [

7,

8,

9]. It was also disclosed that

ONC212 selectively activates protein-coupled receptor 132 (GPCR-GPR132) [

10]. However, it was highlighted that, beyond the multiple effects on TRAIL, DRD2 and GPCR-GPR132 signaling pathways, it is the alteration in mitochondrial metabolism initiated by ClpP activation that is by far the most efficient and dominant pathway leading to apoptosis [

11]. While normally ClpP is regulated by the chaperone ClpX, hyperactivation of ClpP by imipridones and related structures causes an unregulated increase in the degradation of mitochondrial respiratory complexes I and II, leading to structural and functional damage of mitochondria and impairing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Degradation of mitochondrial respiratory proteins is accompanied by, among other consequences, lower oxygen consumption rates, ATP depletion, increased amounts of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and depletion of mitochondrial DNA. These effects collectively activate the integrated stress response (ISR), which directs the cell to arrest the cell cycle and induce apoptosis. Cancer cells are highly sensitive to chemical activation of ClpP, while similar treatments do not induce cell death in normal cells despite a detectable degradation of ClpP substrate proteins [

12]. This tumor-specific cytotoxicity and the wide therapeutic window of anticancer activity of imipridones may be due in part to an apparently lower dependence of normal cells on OXPHOS.

Despite the promising anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of ClpP-activators, the resistance of cancer cells to the treatment seems to be a persistent problem. Accordingly, several studies [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] identified imipridones as effective cytotoxic agents in micro- or nanomolar concentrations, however the dose-response curves showed that approximately 10–50% of the cells survived the treatment, even at higher imipridone concentrations and after prolonged exposure times.

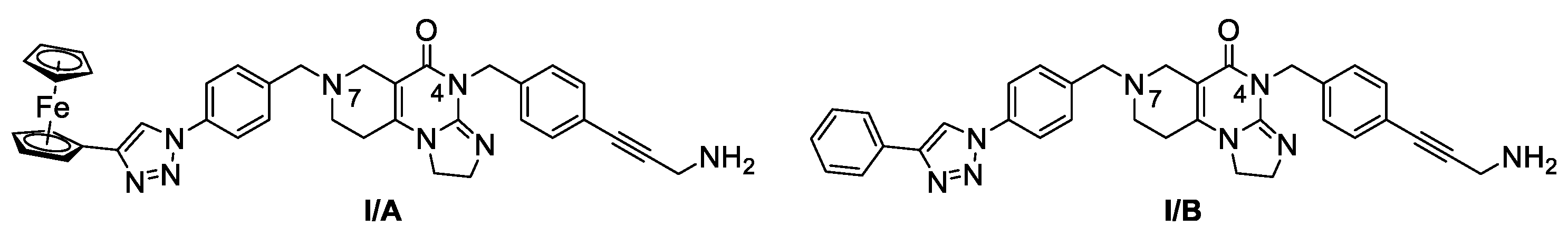

Our research group hypothesized that the tumor cytotoxicity of imipridone derivatives can be improved by boosting ROS formation in the mitochondria through supplementing the hybrid molecule with a ferrocene moiety that activates a Fenton-like pathway. This approach is supported by convincing preclinical evidence for the interplay between TRAIL and redox signaling pathways implicated in cancer [

22]. In this context in a previous article [

23], we have presented ferrocene-impridone derivatives that exhibit much more pronounced long-term cytotoxic effects on A2058 melanoma cell line than

ONC201 and

ONC212. These ferrocenylalkyl-substituted imipridones also displayed a marked efficacy against COLO-205 and EBC-1 cell lines, presumably due to the activation of ROS-implicating apoptotic pathways by the ferrocenyl moieties and their contribution to the antiproliferative effect. Thereafter, inspired by these results, we constructed a small library of organometallic imipridone hybrids, which contain ferrocene fragments tethered by triazole and/or alkyne linkers to different positions of the

N4- and

N5-benzyl groups pending on the imipridone core [

24]. Complex evaluation of this set of hybrids identified propargylamines

I/A and

I/B as the most efficient anti-proliferative agents (

Figure 2).

Contrary to ONC201, these two compounds were able to eliminate the resistance in PANC-1 pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma, Fadu pharyngeal squamous carcinoma, A2058 and EBC-1 cell lines, and no viable cells could be observed after treatments during colony formation assays at 10 µM concentrations. However, the IC50 values of these compounds were found to be 5-10 times higher than those of ONC201. On the other hand, we also demonstrated that in shorter treatment (24 hours exposure time instead of 72 hours) in PANC-1 and A2058 cells, I/A and I/B are far more efficient in apoptosis induction than ONC201, which caused no detectable apoptotic signal in the investigated cells after 24 hours of exposure time. Finally, in comparative cytotoxic studies on PANC-1 and A2058 cells and nontumorous primary fibroblasts, the organometallic derivative I/A emerged as the most potent anticancer agent in the presented research. This ferrocene derivative proved to be capable of complete and selective eradication of the tumor cells at 10 µM concentration without exerting an observable toxicity on the fibroblasts.

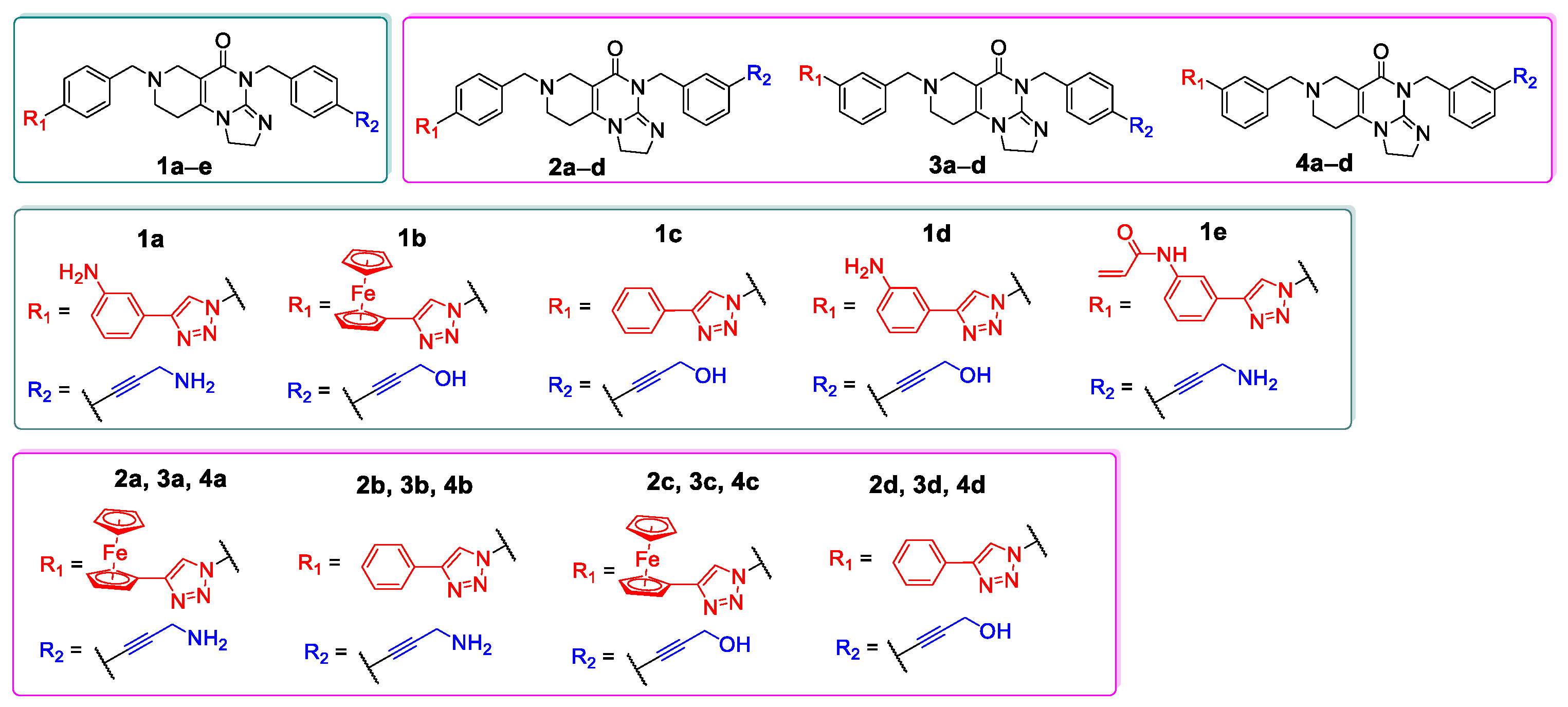

In our current work, we aim to expand the library of imipridone derivatives with members that not only have the potency to eradicate cancer cells completely and selectively, but also lower efficient doses and IC50 values compared to I/A and I/B.

In the initial phase of our diversity-oriented research, we synthesized an array of imipridone hybrids structurally related to

I/A and

I/B carrying identical or systematically modified substituents in different positions of the terminal benzyl groups (

1a–

e,

2a–

d,

3a–

d and

4a–

d:

Figure 3). Compounds

1a–

e can be regarded as the derivatives of

I/A and

I/B with

para-substituted benzyl groups on the terminals of the imipridone scaffold ensuring maximal spatial separation of the arytriazole- and alkyne-containing functional groups, the two potential pharmacophoric warheads. Compounds

2a–

4a and

2b–

4b, containing at least one meta-substituted benzyl group, are regioisomers of

I/A and

I/B, respectively, with spatially less separated and differently oriented pharmacophoric warheads. As an additional variation, we introduced a 3-hydroxypropynyl group into hybrids

1b–

d,

2c,

d 3c,

d and

4c,

d replacing the 3-aminopropynyl moiety to investigate the role of basicity of this outward-protruding functional group. Moreover, for this comprehensive study, which also aimed at a preliminary investigation of the mechanism of action, we synthetized hybrid

1e, the acroylamino analogue of

I/B, which might be capable to covalently bind to cysteine-containing cellular targets.

4. Materials and Methods

All chemicals were obtained from commercially available sources (Merck, Budapest, Hungary; Fluorochem, Headfield, UK; Molar Chemicals, Halásztelek, Hungary; VWR, Debrecen, Hungary) and used without further purifications. Merck Kieselgel (230–400 mesh, 60 Å) was used for flash column chromatography. Melting points (uncorrected) were determined with a Büchi M-560. The 1H and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or in DMSO-d6 solution in 5 mm tubes at room temperature on a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Karlsruhe, Baden Württemberg, Germany) at 500 (1H) and 125 (13C) MHz, with the deuterium signal of the solvent as the lock and TMS as internal standard (1H and 13C). The 2D-HSQC and HMBC spectra, which support the exact assignments of 1H- and 13C NMR signals, were registered by using the standard Bruker pulse programs. Exact mass measurements were performed on a high-resolution Waters ACQUITY RDa Detector (Waters Corp., Wilmslow, UK) equipped with electrospray ionization source using on-line UHPLC coupling. UHPLC separation was performed on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC H-Class PLUS system using a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 x 150 mm, 1.7 µm). Samples were dissolved in MeOH/Water 5:95 V/V, 5-5 µL sample solutions were injected. Linear gradient elution (0 min 5% B, 1.0 min 5% B, 7.0 min 80% B, 7.1 min 100% B, 8.0 min 100% B, 8.1 min 5% B, 12.0 min 5% B) with eluent A (0.1% formic acid in water, V/V) and eluent B (0.1% formic acid in Methanol, V/V) was used at a flow rate of 0.200 mL/min at 45 °C column temperature. High-resolution mass spectra were acquired in the m/z 50-2000 range in positive ionization mode. Leucine enkephalin peptide was used for single Lock Mass calibration correction.

A detailed spectral characterization with the

1H-,

13C-NMR and HRMS data of the targeted hybrid compounds screened in the biological assays (

Table 1 and 2) are listed in the Supplementary Material (S1). The structures of other intermediates can be regarded as chemically evidenced through the spectroscopically confirmed structures of the derived imipridone hybrids.

For each spectroscopically characterized compound the numbering of atoms used for the assignment of 1H- and 13C NMR signals do not correspond to IUPAC rules reflected from the given systematic names (Supplementary Material).

Assignments of the NMR data, copies of the NMR spectra of the novel screened imipridone hybrids (S2–S13), the copies of the

1H- and

13C-NMR spectra (S14–S50) and the HRMS spectra (S51–S87) are included in the

Supplementary Materials

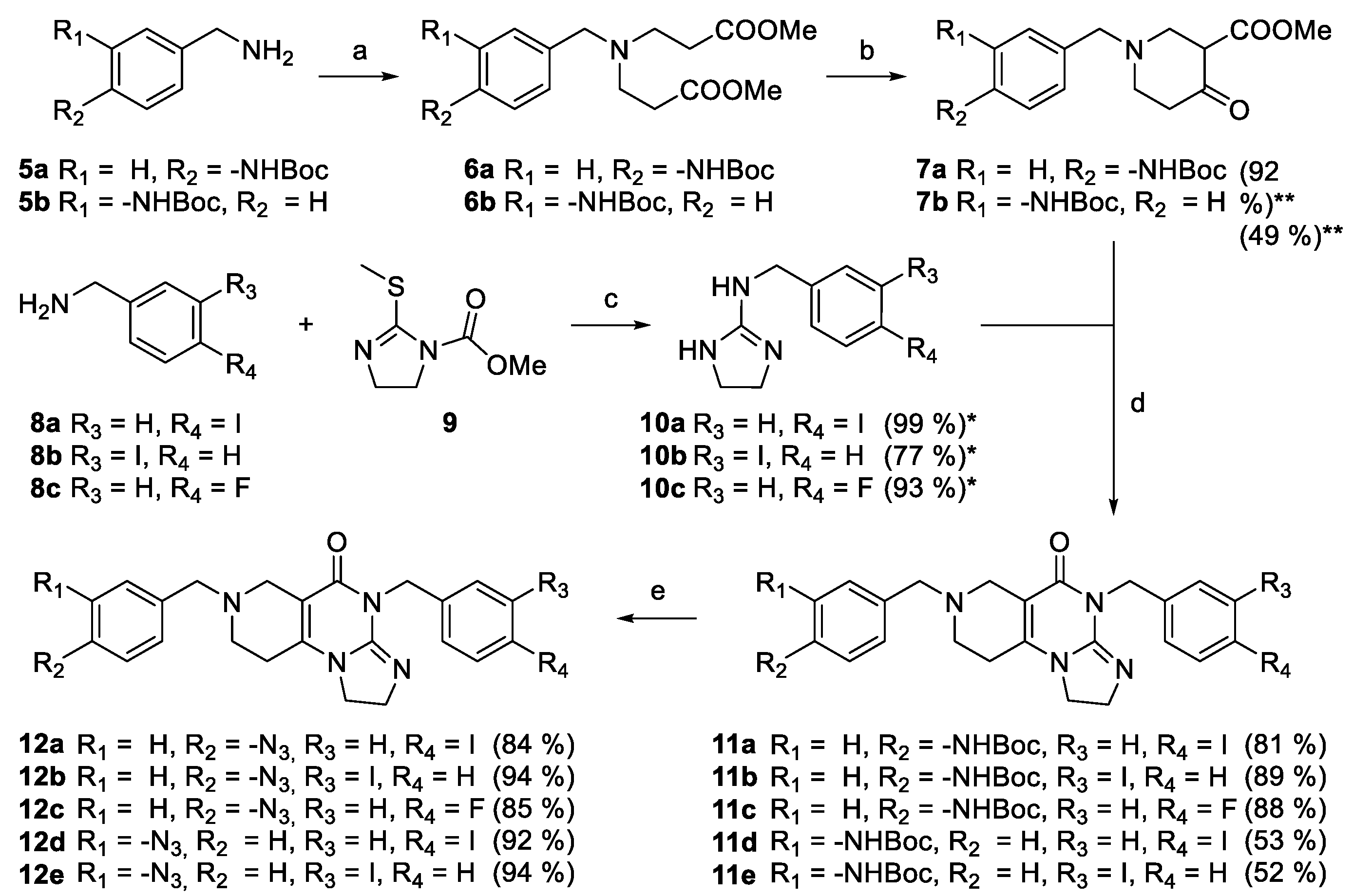

4.1. Synthetic Procedures

4.1.1. Methods (a) and (b) – General procedure for the synthesis of the methyl 1-(tert-butoxycarbonylaminobenzyl)-4-oxopiperidine-3-carboxylates 7a,b (Methods a. and b.)

Methyl acrylate (15 mmol, 5 eq.) was added to a solution of a 3-(Boc-amino)benzylamine (5a) or 4-(Boc-amino)benzylamine (5b) (3 mmol, 1 eq.) in methanol (5 mL), and the mixtures were stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The solutions were concentrated in vacuo to obtain the crude diester products (6a,b). Without further purification, they were dissolved in dry THF (8 mL), and NaH (15 mmol, 5 eq.) was added to the solutions gradually at 0 °C while stirring the mixtures. The suspensions were cooled down to room temperature. After stirring for an additional 2 h, the suspensions were poured over crashed ice (100 g), and the pH of the resulting slurry was set to 7 with acetic acid. The aqueous phases were extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 40 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness in vacuo to obtain the 7a,b, which were used without further purification in the subsequent cyclization step.

4.1.2. Synthesis of 2-(Methylthio)-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate (9)

2-Methylthio-4,5-dihydroimidazolium iodide (50 g, 0.205 mol, 1 eq.) and triethylamine (70 mL, 50.8 g, 0.502 mol, 2.45 eq.) were dissolved in DCM (250 mL). The solution was cooled down to 0 °C. Methylchloroformate (22 mL, 27 g, 0.28 mol, 1.4 eq.) was added dropwise to this cold solution which was then allowed to warm up to room temperature stirred overnight and concentrated in

vacuo. After addition of EtOAc (400 mL) the suspension was stirred for 30 min. The precipitated ammonium salts were filtered off and washed with EtOAc (2 × 50 mL). The combined solution was evaporated to dryness. The solid residue was triturated with water (200 mL), filtered off and dried under

vacuo to obtain

9 as a white solid (27.2 g, 0.156 mol, 76%) [

23].

4.1.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Cyclic Guanidines 10a–d (Method c)

Primary amines (

8a–

d) (10 mmol, 1 eq.) were dissolved in a mixture of methanol (24 mL) and acetic acid (6 mL). To the solutions, 2-(methylthio)-4,5-dihydro-1

H-imidazole-1-carboxylate (

9) (2.18 g, 12.5 mmol, 1.25 eq.) was added, and the resulting mixtures were stirred at reflux for 18 h. The solutions were concentrated in vacuo, and the oily residues were dissolved in DCM (100 mL) and were washed with 3 M NaOH solution (2 × 10 mL), and brine (1 × 10 mL). The organic phases were dried over Na

2SO

4 and concentrated in

vacuo. The products were used without further purification in the subsequent step [

23].

4.1.4. Method (d) – General Procedure for the Synthesis of Imipridone Scaffold 11a–f (Method d).

The appropriate N-substituted methylcarboxylate piperidone 7a,b (2 mmol, 1 eq.) and cyclic guanidine (10a–d) (2 mmol, 1 eq.) were dissolved in methanol (10 mL). To this mixture a 3.6 M methanolic solution of NaOMe was added (0.69 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.25 eq.) and stirred at reflux temperature for 12 h. In case of reactions with 10a, the mixture was cooled after 12 h, and the precipitated white crystalline product (11a, 11d) was filtered off, washed twice with cold methanol (2 × 1 mL) and dried in vacuo. In other cases, the mixtures were cooled, concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in DCM (100 mL), washed with water (2 × 10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude yellow oily products were purified with column chromatography on silica using DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 15:1:0.1) as eluent. The collected band was crystallized from Et2O to obtain 11b–c and 11e,f, as yellowish white powder.

4.1.5. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Azidoimipridones 12a–f (Method e)

The appropriate N-Boc protected compound 11a–f (1 mmol, 1 eq.) was dissolved in cc. HCl (5 mL). After stirring for 30 min at 0 °C, using a syringe aqueous NaNO2 solution (2 mmol, 2 eq. in 1.5 mL water) was added dropwise to the solution which was then stirred for 45 min at 0 °C. To the resulting cold mixture solid NaN3 (10 mmol, 10 eq.) was added in portions over 15 min, stirred for further 30 min at 0 °C, then allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for an additional 1 h. The acidic mixture was neutralized with Na2CO3 and extracted with DCM (3 × 40 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with water (2 × 10 mL) and brine (1 ×10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The products were crystallized from Et2O to isolate 12a–f as white solids.

4.1.6. General Procedure for Copper(I) Catalyzed 1,4-Azide-alkyne Cycloadditions (Method f)

The appropriate azidoimipridone (12a–f) (0.5 mmol, 1 eq.), alkyne component (13–15, 34a–c) (0.5 mmol, 1 eq.) and CuI (9.5 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.1 eq.) were dissolved in DMSO (2 mL) and stirred for 12 hours at room temperature in a closed vial. After 12 hours, the mixture was poured in water (20 mL) and stirred for 20 min. The precipitate was filtered off and washed with water (5 × 10 mL). The filter was washed with DCM (4 × 10 mL). The combined organic filtrates were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified using column chromatography (silicagel, DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 15:1:0.1) and crystallized from Et2O to yield amber/orange (in case of ferrocene-containing compounds – 16a, 16d, 16g, 16i, 37a) or white powder (16b–c, 16e–f, 16h, 16j, 35a–c, 37b).

4.1.7. General Procedure for the Sonogashira coupling reactions (Method g)

The appropriate iodoimipridone (16a–e, 16g–j, 22a,b, 32a,b or 35a–c) (0.2 mmol, 1 eq.), propargyl derivative (17a–g or 18) (0.2 mmol, 1 eq.), CuI (7.6 mg, 0.04 mmol, 0.2 eq.), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (14.0 mg, 0.02 mmol, 0.1 eq.) and DIPEA (129 mg, 1 mmol, 5 eq.) were dissolved in DMF (2 mL) and stirred for 24 h. After 24 h, the mixture was poured in water (30 mL) and stirred for 20 min. The precipitate was filtered off and washed with water (5 × 10 mL). The filter was washed with DCM (4 × 20 mL). The combined organic filtrate was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified using column chromatography (silicagel, DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 15:1:0.1), and crystallized from Et2O to yield amber/orange (in case of ferrocene-containing compounds – 1b, 2a, 2c, 3a, 3c, 4a, 4c, 23a, 33a, 38a, 39a, 40a, 41a, 42a) or white powder (1a, 1c, 2b, 2d, 3b, 3d, 4b, 4d, 19, 23b, 33b, 36a–c, 38b, 39b, 40b, 41b, 42b, 43a–c).

4.1.8. Synthesis of acrylamido imipridone 1e (Sequential application of Methods h. and i)

Compound 1e was accessed by sequential acylation and deprotection procedures.

Method h.): Aniline derivative 19 (68.3 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1 eq.) and DIPEA (26 mg, 0.2 mmol, 2 eq.) were dissolved in DCM (10 mL). To this mixture a solution of acryloyl chloride (12 mg, 0.13 mmol, 1.3 eq.) in DCM (5 mL) was added dropwise at room temperature under N2 flow. The resulting solution was stirred for 4 h at room temperature, then concentrated in vacuo.

Method i.): To the residue concentrated HCl (2 mL) was added, and the solution was stirred for 20 minutes at room temperature, then diluted with 8 mL of water. The pH was set to 10 with K2CO3 and the mixture was extracted with DCM (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine (5 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM:MeOH:NH3 (10:1:0.1) as eluent. The collected band was evaporated, and the oily residue was crystallized from Et2O to obtain 1e as a white powder.

4.1.9. Deprotection of N-Boc protected iodoimipridone 11b to produce iodinated free amine XIb (Method i)

Compound 11b (500 mg, 0.82 mmol) and concentrated HCl acid (5 mL) were added to a flask and stirred at room temperature. After 20 minutes the solution was diluted with water (45 mL) and the pH was set to 10 with K2CO3. The mixture was extracted with DCM (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (2 × 10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo yielding a white solid (XIb) (414 mg, 0.81 mmol, 99%), which was used in the subsequent acylation reactions without further purification.

4.1.10. Synthesis of amides 22a and 27a,b (Method j)

Acyl chlorides [ferrocenoyl chloride (20) or 4-formylbenzoyl chloride (25)] (0.8 mmol, 2 eq.) were dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and a solution of the appropriate amino compound [XIb, aminoferrocene (26a) or aniline (26b)] (0.4 mmol, 1 eq.) and DIPEA (155 mg, 1.2 mmol, 3 eq.) in DCM (10 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C under N2 flow. The mixtures were stirred at 0°C for 30 minutes, then allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for an additional 1 h. In the course of the synthesis of imipridone compound 22a the reaction mixture was washed with saturated Na2CO3 solution (2 × 5 mL), water (1 × 5 mL) and brine (1 × 5 mL). In the course of the synthesis of compounds 27a,b the reaction mixtures were subsequently washed with 1M HCl (2 × 5 mL) and saturated Na2CO3 solution. The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo to obtain an orange oil (22a) (280 mg), brown-red solid (27a) (127 mg, 0.38 mmol, 95%) or white powder (27b) (88 mg, 0.39 mmol, 98%). Compounds 27a,b were used in the subsequent reductive alkylation step without further purification, while 22a was purified by column chromatography on silicagel using DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 30:1:0.1 as eluent to yield an orange solid foam (61 mg, 0.084 mmol, 21%).

4.1.11. Synthesis of benzamide 22b (Methods k)

Compound XIb (205 mg, 0.4 mmol, 1 eq.), benzoic anhydride (21) (181 mg, 0.8 mmol, 2 eq.) and DIPEA (155 mg, 1.2 mmol, 3 eq.) were dissolved in DCM (20 mL) and the solution was stirred at reflux for 24 h, then cooled down, washed with 10% NaOH solution (2 × 5 mL), water (1× 5 mL) and brine (1× 5 mL). The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, and crystallized from Et2O to obtain 22b (195 mg, 0.316 mmol, 79%) as a white powder.

4.1.12. Synthesis of ferrocenoyl chloride 20 and 4-formylbenzoyl chloride 25 (Method l)

The appropriate carboxylic acid [ferrocene carboxylic acid (460 mg, 2 mmol, 1 eq.) or 4-formylbenzoic acid (24) (300 mg, 2 mmol, 1 eq.)] was added to DCM (10 mL). To this mixture oxalyl chloride (1.02 g, 8 mmol, 4 eq.) dissolved in DCM (5 mL) then 2 drops of DMF were added sequentially at room temperature. The resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h, then concentrated in vacuo yielding an orange-brown oil (20) or a white solid (25), which was then triturated with hexane (10 mL). The insoluble impurities were filtered off and the filtrates were concentrated in vacuo to obtain ferrocenoyl chloride (20) (484 mg, 1.95 mmol, 97%) as an orange red oil or 4-formylbenzoyl chloride (25) (311 mg, 1.84 mmol, 92%) as a white powder.

4.1.13. Synthesis of the methyl N-Boc-4-oxopiperidine-3-carboxylate (30) (Method m)

N-Boc-4-oxopiperidin (28) (3.0 g, 15 mmol, 1 eq.) and dimethyl-carbonate (29) (6.8 g, 75 mmol, 5 eq.) were dissolved in dry toluene (22 mL) under Ar atmosphere. To this solution, NaH (1.8 g, 75 mmol, 5 eq.) was added in small portions and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and refluxed for an additional 2 h under Ar. The mixture was poured over ice (100 g) and the pH was set to 7 with acetic acid. The neutral slurry was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo to yield 30 as a yellow oil (3.48 g, 13.5 mmol, 90%) which was used as cyclisation partner in the subsequent step without further purification.

4.1.14. Synthesis of 4-(3-iodobenzyl)-2,4,6,7,8,9-hexahydroimidazo[1,2-a]pyrido[3,4-e]- pyrimidin-5(1H)-one (31) (sequential application of Methods d. and i.)

Compound 31 was accessed by the sequential procedures used for the construction of the imipridone scaffold.

Method d): Methyl N-Boc-4-oxopiperidine-3-carboxylate (30) (180 mg, 0.7 mmol, 1 eq.) and the appropriate cyclic guanidine (10b) (211 mg, 0.7 mmol, 1 eq.) were dissolved in methanol (10 mL) and 3.6 M NaOMe solution in methanol (0.24 mL, 0.825 mmol, 1.25 eq.) was added. The mixture was stirred at reflux for 12 h, then cooled, concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in DCM (40 mL), washed with water (2 × 7 mL) and brine (7 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude yellow oily product was purified with column chromatography (silicagel, DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 20:1:0.1) yielding a light-yellow solid foam (234 mg, 0.46 mmol, 66%).

Method i.): The product of the previous step was dissolved in concentrated HCl (3 mL) and stirred at room temperature. After 20 minutes the solution was diluted with water (30 mL) and the pH was set to 10 with K2CO3. The mixture was extracted with DCM (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine (5 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo yielding a light-yellow solid foam (31) (178 mg, 0.436 mmol, 95% for the deprotection, 62% cumulative yield), which was used without further purification.

4.1.15. Synthesis of compounds 32a–b by reductive alkylation (Method n.)

The appropriate aldehyde (27a–b, 0.25 mmol, 1 eq.) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL). To this solution 31 dissolved in DCM (10 mL) was added. The mixtures were stirred at room temperature for 20 minutes. Then NaHB(OAc)3 (74 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.4 eq.) was added in small portions over the course of 15 minutes, and the resulting mixtures were stirred for an additional 2.5 hours at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by TLC and upon completion a saturated solution of K2CO3 (10 mL) was added and the mixtures were stirred vigorously for 15 minutes. The organic phases were separated, and the aqueous phases were extracted with DCM (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine (1 × 5 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified using column chromatography (silicagel, DCM:MeOH:NH3 = 15:1:0.1) and crystallized from Et2O to obtain 32a (105 mg, 0.145 mmol, 58%) as an orange and 32b (121 mg, 0.196 mmol, 78%) as a white powder.

4.1.16. Synthesis of propargylamine derivatives 17e–g

The appropriate amine (piperidine, N-methylpiperazine or morpholine) (5 mmol, 1 eq.) was dissolved in acetonitrile (20 mL) and K2CO3 (1.4 g, 10 mmol, 2 eq.), then propargyl bromide (80% in toluene) (820 mg, 5.5 mmol, 1.1 eq.) was added while stirring at room temperature. The resulting suspensions were stirred overnight at room temperature in a closed vial under argon. The mixtures were concentrated in vacuo and triturated with Et2O (30 mL). The insoluble salts were filtered off and the filtrates were concentrated in vacuo and purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM:MeOH:NH3 (15:1:0.1) as eluent to obtain 17e (123 mg, 1 mmol, 20%), 17f (343 mg, 2.5 mmol, 50%) and 17g (463 mg, 3.7 mmol, 74%) as orange-yellow oils.

4.2. Biological Assays

4.2.1. Cell Culturing

Pharynx squamous cell carcinoma cell line Fadu (HTB-43™), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line PANC-1 (CRL-1469™), primary human fibroblasts, and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% (V/V) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. The Fadu and PANC-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and the authentication of these cell lines was validated by STR DNA analysis (Eurofins Scientific, Luxembourg, Luxembourg). All cell lines were routinely screened for the absence of mycoplasma infection (DAPI staining).

Primary fibroblast cultures were prepared from human skin biopsies and maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We received HEK293T WT and HEK293T CLPP-/- cells as a gift from Aleksandra Trifunovic for the validation of the CLPP-independent mechanism of action.

4.2.2. CellTiter-Glo Cell Viability Assay Including the Assessment of ClpP-Coupled Action

Effects of the synthesized compounds on cell viability were measured by CellTiter-Glo® luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded onto a flat-bottomed, white 96 well plate (BRANDplates, cat. no.: 781965)), with the following density: PANC-1: 750 cells/well, Fadu: 2000 cells/well, Primary Fibroblast: 2000 cells/well, HEK293T WT: 1000 cells/well, HEK293T CLPP-/-: 2500 cells/well. After seeding, cells were incubated further for 48 h before the treatment. Cells were treated with the compounds for 72h. Three concentrations (25.0 µM; 8.3 µM; 2.8 µM) were applied at the initial cell viability screening, while at the determination of dose response curves 1.5-fold serial diluted compound concentrations were applied (range: 26 µM – 0.7 µM). After the treatment, the luminescence signal was recorded using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Dose–response curves (non-linear regression model) were generated and IC50 values were determined using Graph Pad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The selectivity index (SI) of each molecule tested was calculated as the IC50 on primary fibroblasts / IC50 on cancer cells.

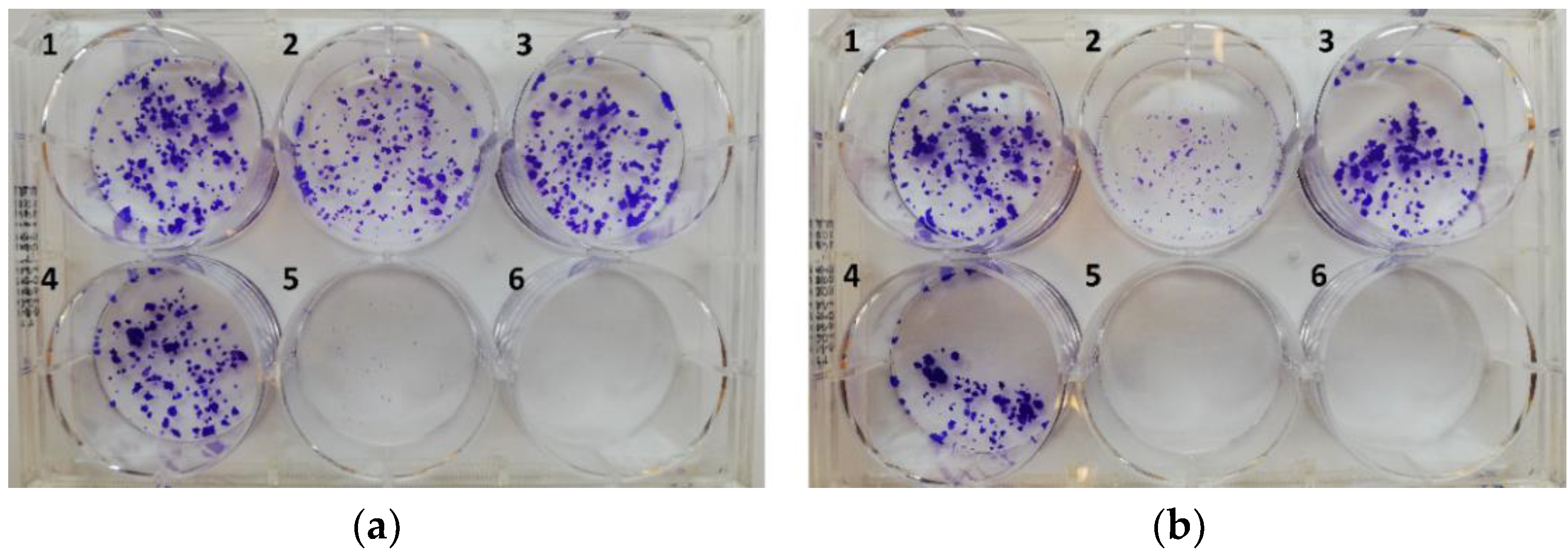

4.2.3. Colony formation assay

Long-term cell survival after treatments was determined by clonogenic assay. PANC-1 cells were seeded in a transparent 6-well cell culture plate (VWR) (density: 1000 cells/well). After seeding, cells were incubated for 72 h before the treatment. Cells were treated with the compounds at 4 µM for 24 h or 72 h. Then, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells formerly treated for 24 or 72 h were further incubated in cell culture medium for 5 or 3 days, respectively. Thereafter, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After fixation, the cells were washed with PBS, and 0.5% w/v crystal violet (CV) solution was added. After 1 h, the CV solution was removed, and the cells were washed thoroughly with water. Images were created by Corel Photo-Paint 2019.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., T.C and J.M.; methodology, T.C., J.M., I.M., B.G., A.V., D.P., and G.S.; validation, B.G, A.V., J.M. I.M. and G.S. formal analysis, B.G, A.V., J.M. I.M. D.P. and G.S; investigation, T.C., J.M., I.M., B.G., A.V. and A.C.; resources, A.C., M.C. and G.S.; data curation, J.M., I.M., B.G., A.V. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., J.M. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, J.M., I.M., B.G., A.V., M.C. and A.C.; visualization, A.C. T.C. and I.M.; supervision, A.C. J.M. and G.S; project administration, T.C.; funding acquisition, A.C., M.C., and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Emblematic imipridones under clinical (ONC201 and ONC206) or preclinical (ONC212) studies.

Figure 1.

Emblematic imipridones under clinical (ONC201 and ONC206) or preclinical (ONC212) studies.

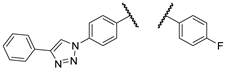

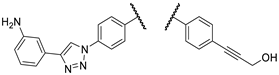

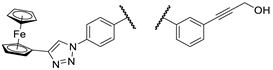

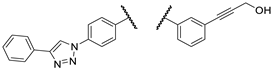

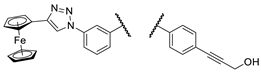

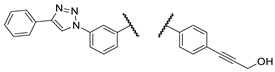

Figure 2.

The most promising compounds identified in our previous work [

24].

Figure 2.

The most promising compounds identified in our previous work [

24].

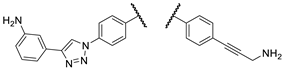

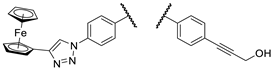

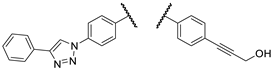

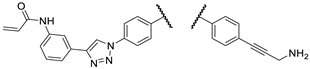

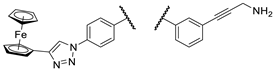

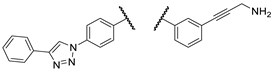

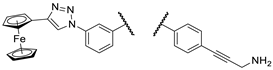

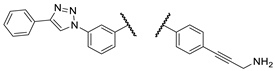

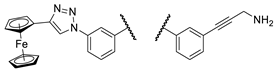

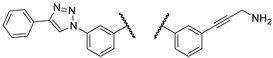

Figure 3.

Various regioisomers and structurally related derivatives of I/A and I/B intended for synthesis and in vitro cell viability screening as members of the first set of compounds.

Figure 3.

Various regioisomers and structurally related derivatives of I/A and I/B intended for synthesis and in vitro cell viability screening as members of the first set of compounds.

Scheme 1.

Convergent synthetic pathway leading to halogenated azidoimipridones. Reaction conditions: (a) methyl acrylate (5 eq.), MeOH, r.t., 48 h; (b) NaH (5 eq.), THF, 0 °C, then r.t., 2 h; (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (e) 1) cc. HCl, r.t., 30 min. 2) NaNO2 (2 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min; 3) NaN3 (10 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min, then r.t., 1 h; (* = crude product; ** = cumulative yield, crude product).

Scheme 1.

Convergent synthetic pathway leading to halogenated azidoimipridones. Reaction conditions: (a) methyl acrylate (5 eq.), MeOH, r.t., 48 h; (b) NaH (5 eq.), THF, 0 °C, then r.t., 2 h; (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (e) 1) cc. HCl, r.t., 30 min. 2) NaNO2 (2 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min; 3) NaN3 (10 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min, then r.t., 1 h; (* = crude product; ** = cumulative yield, crude product).

Scheme 2.

Sequential functionalization reactions on the terminal benzyl groups of the imipridone scaffold affording the first group of the targeted hybrids. Reaction conditions: (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Scheme 2.

Sequential functionalization reactions on the terminal benzyl groups of the imipridone scaffold affording the first group of the targeted hybrids. Reaction conditions: (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of acrylamido derivative 1e employing a three-step procedure supported by selective N-protection strategy: Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (h) acryloyl chloride (1.3 eq.), DIPEA (2 eq.), DCM, r.t, 4 h.; (i) cc. HCl, r.t, 20 min.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of acrylamido derivative 1e employing a three-step procedure supported by selective N-protection strategy: Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (h) acryloyl chloride (1.3 eq.), DIPEA (2 eq.), DCM, r.t, 4 h.; (i) cc. HCl, r.t, 20 min.

Figure 4.

Envisaged fragment refinements in 2a,b, the members of the first set of the targeted hybrids, which proved to be prominently efficient in the primary viability screening.

Figure 4.

Envisaged fragment refinements in 2a,b, the members of the first set of the targeted hybrids, which proved to be prominently efficient in the primary viability screening.

Scheme 4.

Synthetic route to the first type of amido-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (i) cc. HCl, r.t., 20 min; (j) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, r.t., 1,5 h; (k) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, reflux, 24 h; * = crude product.

Scheme 4.

Synthetic route to the first type of amido-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (i) cc. HCl, r.t., 20 min; (j) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, r.t., 1,5 h; (k) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, reflux, 24 h; * = crude product.

Scheme 5.

Synthetic route to the second type of amido-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (i) cc. HCl, r.t., 20 min; (j) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, 0°C, 30 min., then r.t., 1 h; (l) oxalyl chloride (2 eq.), DMF (cat.), DCM, r.t., 20 min; (m) NaH (5 eq.), toluene, r.t., 3 h, then reflux 2 h; (n) 1) DCM, r.t, 20 min., 2) NaHB(OAc)3 (1.4 eq.), r.t., 2.5 h.; * = crude product.

Scheme 5.

Synthetic route to the second type of amido-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h; (i) cc. HCl, r.t., 20 min; (j) DIPEA (3 eq.), DCM, 0°C, 30 min., then r.t., 1 h; (l) oxalyl chloride (2 eq.), DMF (cat.), DCM, r.t., 20 min; (m) NaH (5 eq.), toluene, r.t., 3 h, then reflux 2 h; (n) 1) DCM, r.t, 20 min., 2) NaHB(OAc)3 (1.4 eq.), r.t., 2.5 h.; * = crude product.

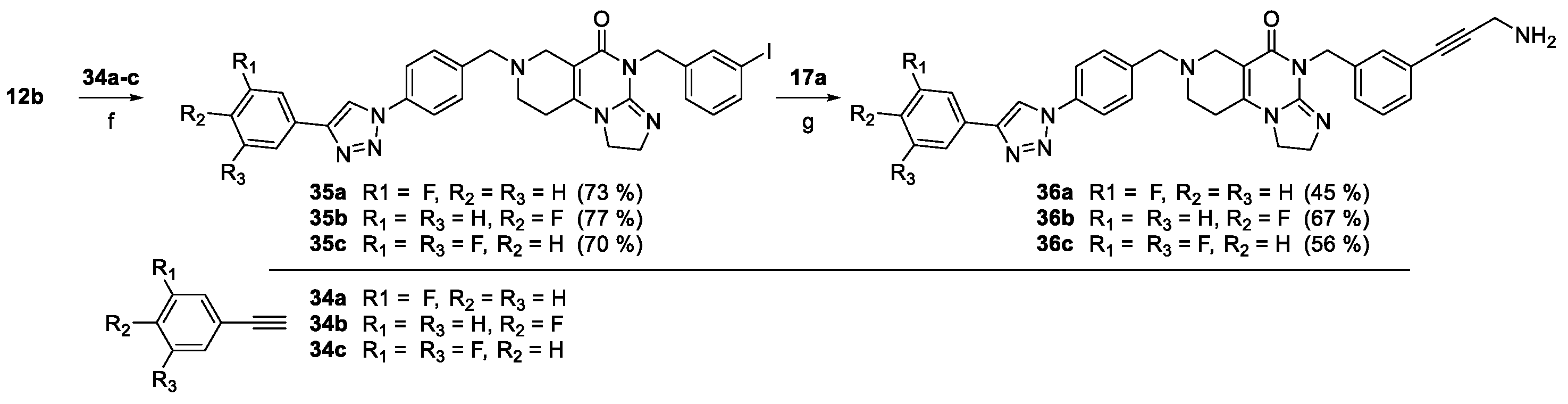

Scheme 6.

Synthetic route to 36a–c, the fluorinated derivatives of 2b. Reaction conditions: (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Scheme 6.

Synthetic route to 36a–c, the fluorinated derivatives of 2b. Reaction conditions: (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; (g) propargylamine (2 eq.), CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

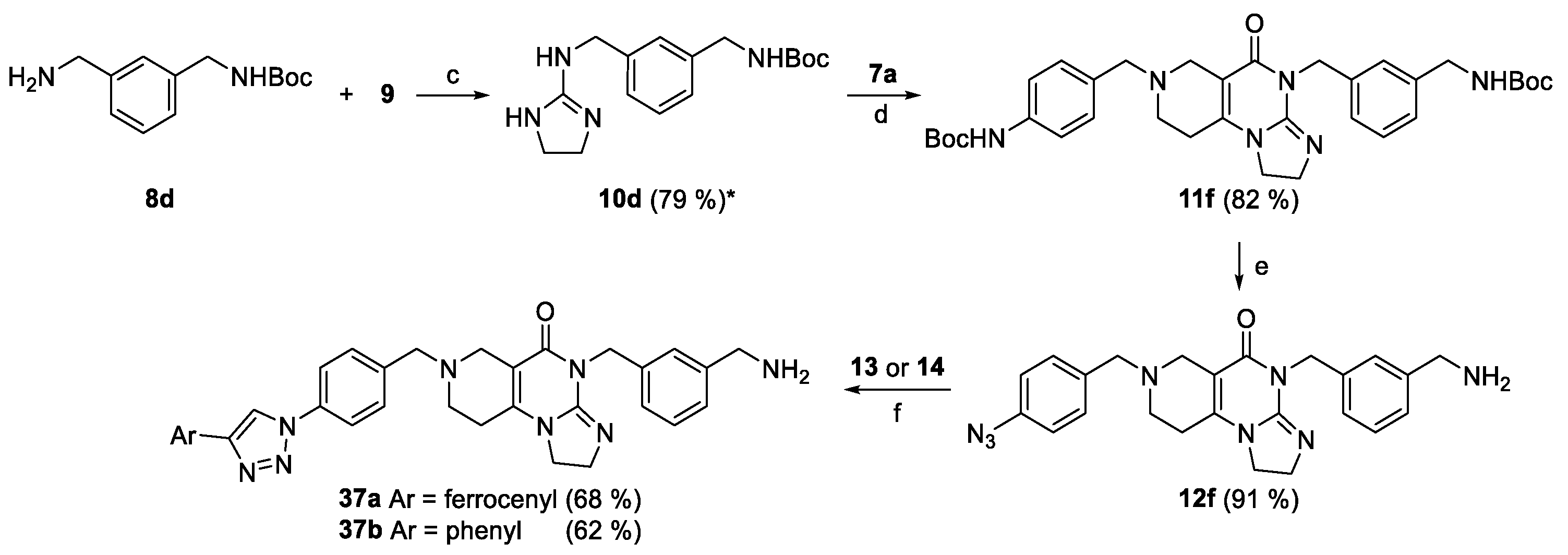

Scheme 7.

Synthetic route to the aminomethyl-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (e) 1) cc. HCl, r.t., 30 min 2) NaNO2 (2 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min 3) NaN3 (10 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min, then r.t., 1 h; (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; * = crude product.

Scheme 7.

Synthetic route to the aminomethyl-imipridone derivatives. Reaction conditions: (c) MeOH/AcOH = 4/1, reflux, 18 h; (d) 3.6 M NaOMe/MeOH (1.25 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 12 h; (e) 1) cc. HCl, r.t., 30 min 2) NaNO2 (2 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min 3) NaN3 (10 eq.), 0 °C, 45 min, then r.t., 1 h; (f) CuI (0.1 eq.), DMSO, r.t., 24 h; * = crude product.

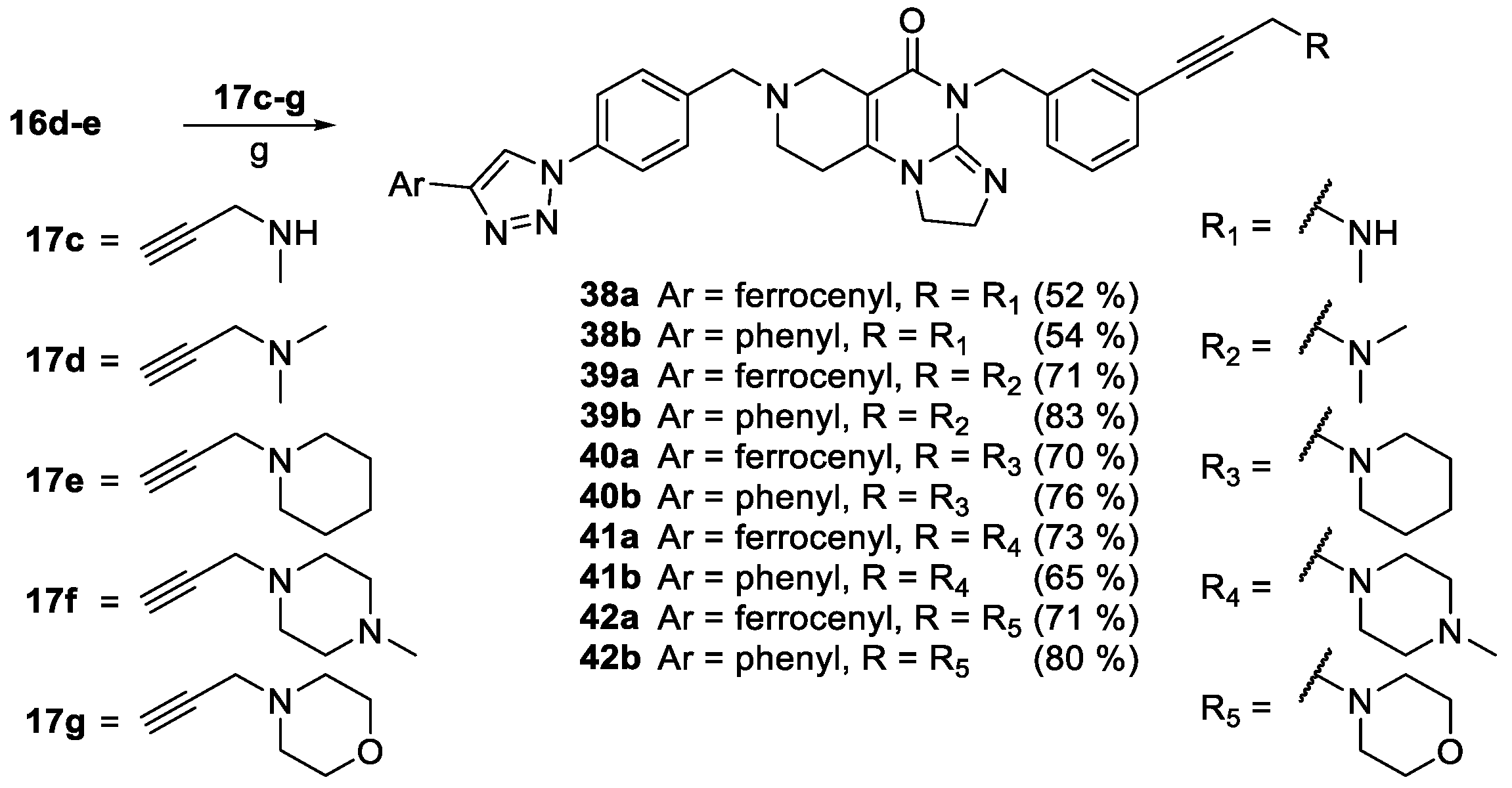

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of N-alkylated derivatives of 2a–b. Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of N-alkylated derivatives of 2a–b. Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Figure 5.

Dose–response curves of selected imipridone hybrids I/A, I/B, 38a,b, 43a–c and ONC201 on PANC-1 and Fadu cells and non-tumorous primary fibroblast cells measured by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay. Curves were fitted by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software using nonlinear regression (variable slope; 95% CI; n = 4). The concentration scale is logarithmic.

Figure 5.

Dose–response curves of selected imipridone hybrids I/A, I/B, 38a,b, 43a–c and ONC201 on PANC-1 and Fadu cells and non-tumorous primary fibroblast cells measured by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay. Curves were fitted by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software using nonlinear regression (variable slope; 95% CI; n = 4). The concentration scale is logarithmic.

Figure 6.

Colony formation assay of selected imipridone derivatives on PANC-1 cell line at 4 µM concentration: (a) 24 h treatment followed by 5 days postincubation; (b) 72 h treatment followed by 3 days postincubation. 1: DMSO (control), 2: ONC201, 3: I/A, 4: I/B, 5: 38a and 6: 38b.

Figure 6.

Colony formation assay of selected imipridone derivatives on PANC-1 cell line at 4 µM concentration: (a) 24 h treatment followed by 5 days postincubation; (b) 72 h treatment followed by 3 days postincubation. 1: DMSO (control), 2: ONC201, 3: I/A, 4: I/B, 5: 38a and 6: 38b.

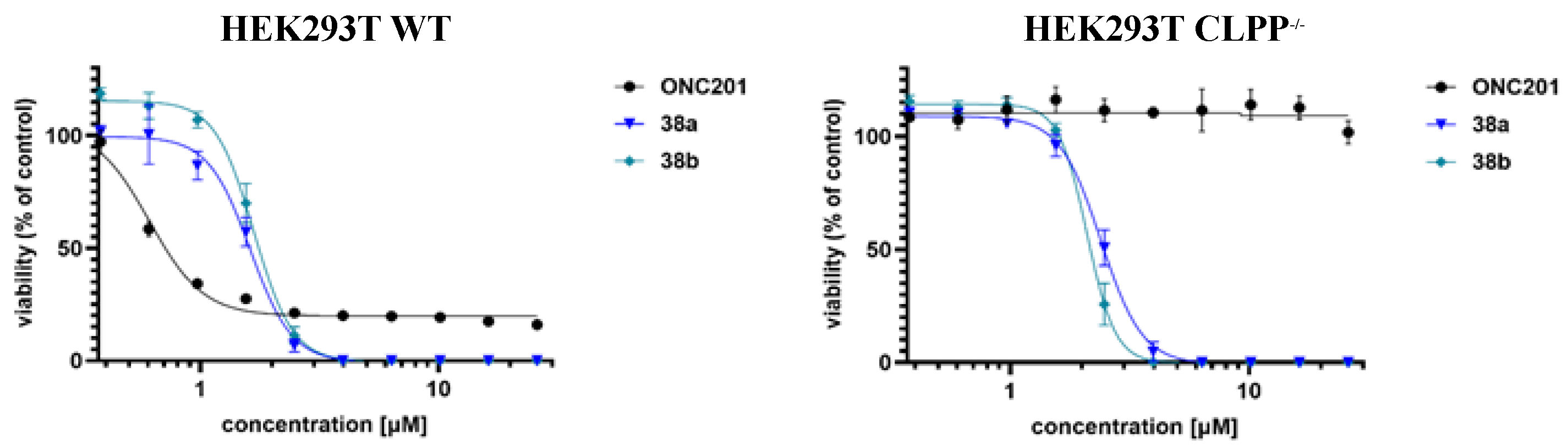

Figure 6.

Dose–response curves of imipridone hybrids 38a,b and ONC201. Viability measured on HEK293T and HEK293T-/- cell lines based on CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay. Curves were fitted by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software using nonlinear regression (variable slope; 95% CI; n = 3). The concentration scale is logarithmic.

Figure 6.

Dose–response curves of imipridone hybrids 38a,b and ONC201. Viability measured on HEK293T and HEK293T-/- cell lines based on CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay. Curves were fitted by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software using nonlinear regression (variable slope; 95% CI; n = 3). The concentration scale is logarithmic.

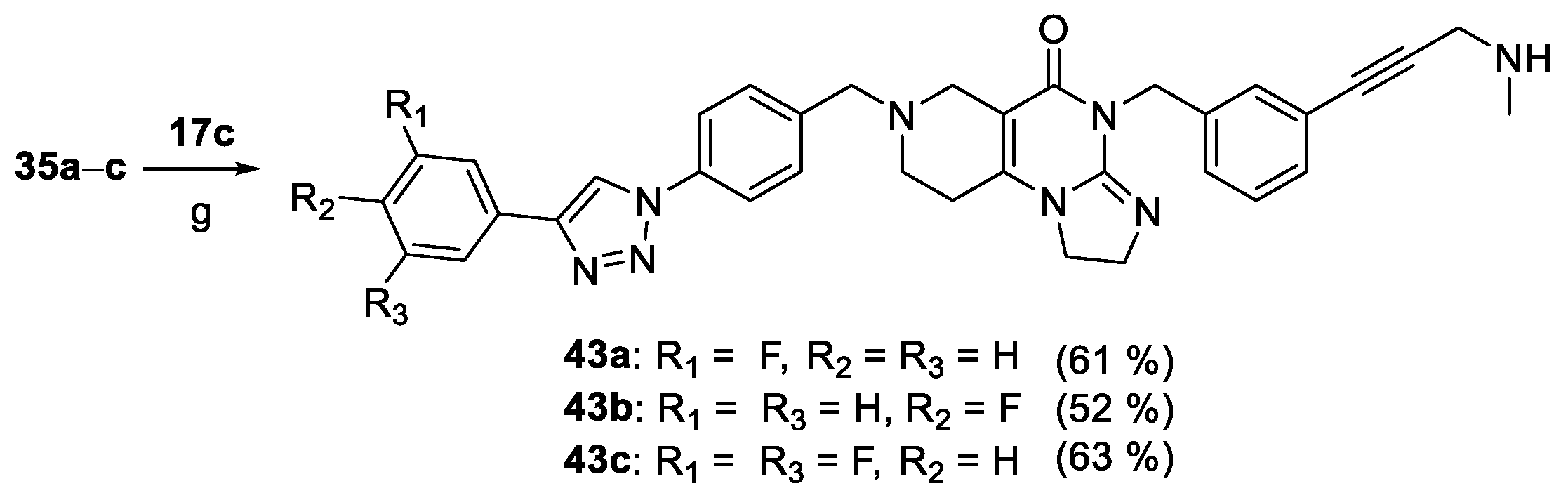

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of N-methylated derivatives 43a–c carrying fluorinated phenyl groups on the triazolyl substituent. Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of N-methylated derivatives 43a–c carrying fluorinated phenyl groups on the triazolyl substituent. Reaction conditions: (g) CuI (0.2 eq.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 eq.), DIPEA (3 eq.), DMF, r.t., 24 h.

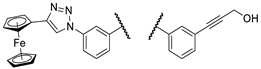

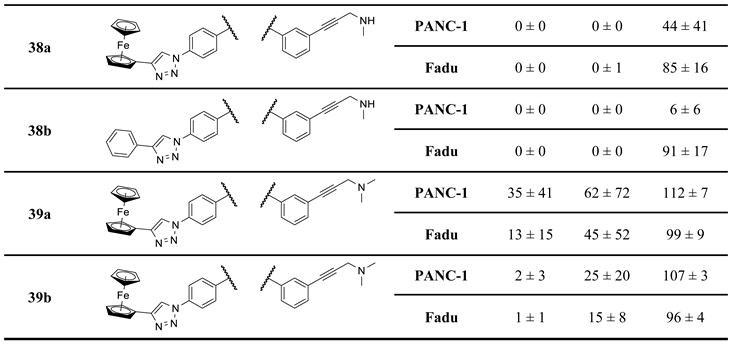

Table 1.

Results of the initial viability screening of the first set of novel imipridone derivatives on PANC-1 and Fadu cancer cell lines.

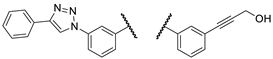

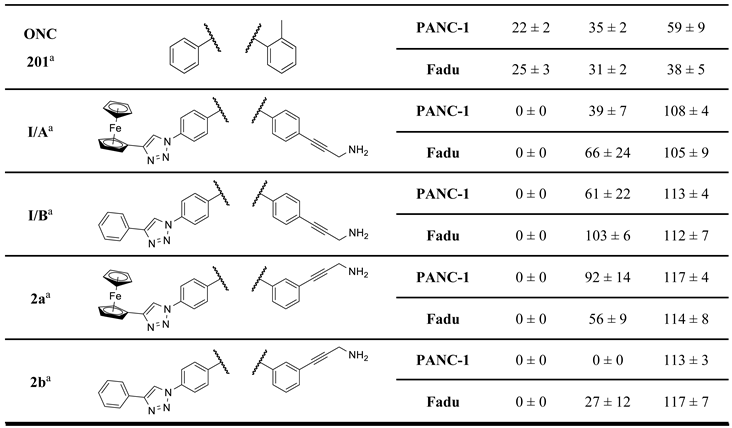

Table 2.

Results of the initial viability screening of the second set of novel imipridone derivatives on PANC-1 and Fadu cancer cell lines.

Table 2.

Results of the initial viability screening of the second set of novel imipridone derivatives on PANC-1 and Fadu cancer cell lines.

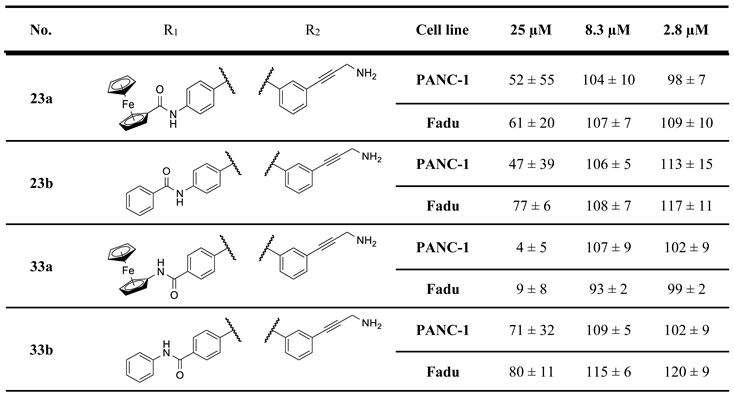

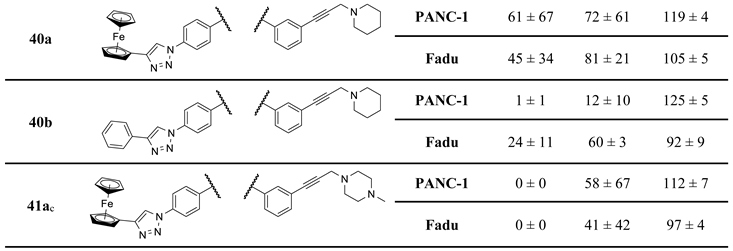

Table 3.

IC50 values (µM) of the selected imipridone derivatives and reference compounds on PANC-1 and Fadu cell lines obtained by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay after 72 h treatment using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software (nonlinear regression; variable slope; best-fit values; n = 4).

Table 3.

IC50 values (µM) of the selected imipridone derivatives and reference compounds on PANC-1 and Fadu cell lines obtained by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay after 72 h treatment using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software (nonlinear regression; variable slope; best-fit values; n = 4).

| |

IC50 value |

Selectivity index (SI)a

|

| |

PANC-1 |

Fadu |

Primary

fibroblast |

Fibroblast / PANC-1 |

Fibroblast / Fadu |

| ONC201 |

3.1 |

1.3 |

26 < b

|

1.6 < |

3.9 < |

| I/A |

10.7 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

| I/B |

8.2 |

10.3 |

11.0 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

| 38a |

2.7 |

2.9 |

4.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

| 38b |

2.5 |

3.3 |

4.4 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

| 43a |

2.5 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

| 43b |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

| 43c |

2.6 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

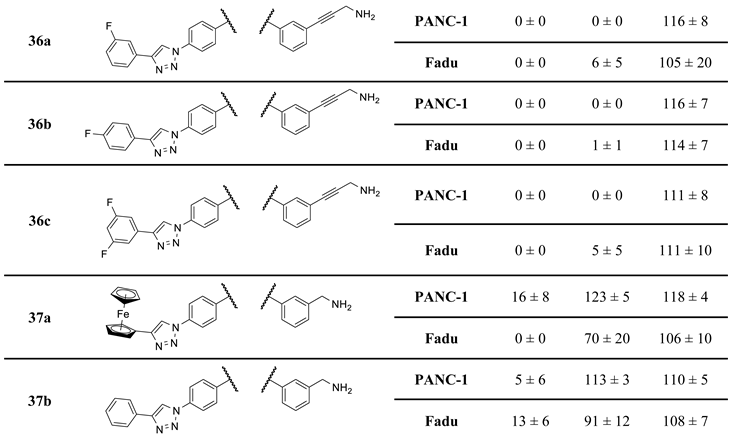

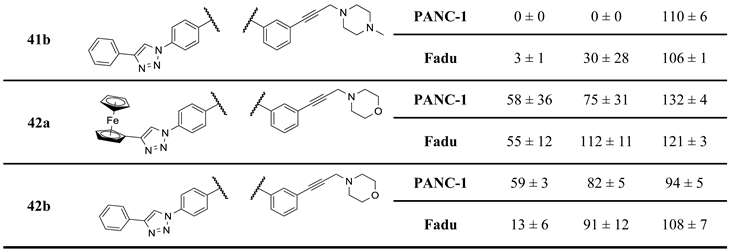

Table 4.

IC50 values (µM) of 38a,b and ONC201 on HEK293T WT and CLPP-/- cells measured by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay after 72 h treatment. IC50 values were determined by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software (nonlinear regression; variable slope; best-fit values; n = 4).

Table 4.

IC50 values (µM) of 38a,b and ONC201 on HEK293T WT and CLPP-/- cells measured by CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay after 72 h treatment. IC50 values were determined by GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software (nonlinear regression; variable slope; best-fit values; n = 4).

| |

IC50 (µM) |

| |

HEK293T WT |

HEK293T CLPP-/- |

| ONC201 |

0.6 |

n. d. |

| 38a |

1.6 |

2.4 |

| 38b |

1.7 |

2.1 |