Submitted:

31 May 2024

Posted:

31 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

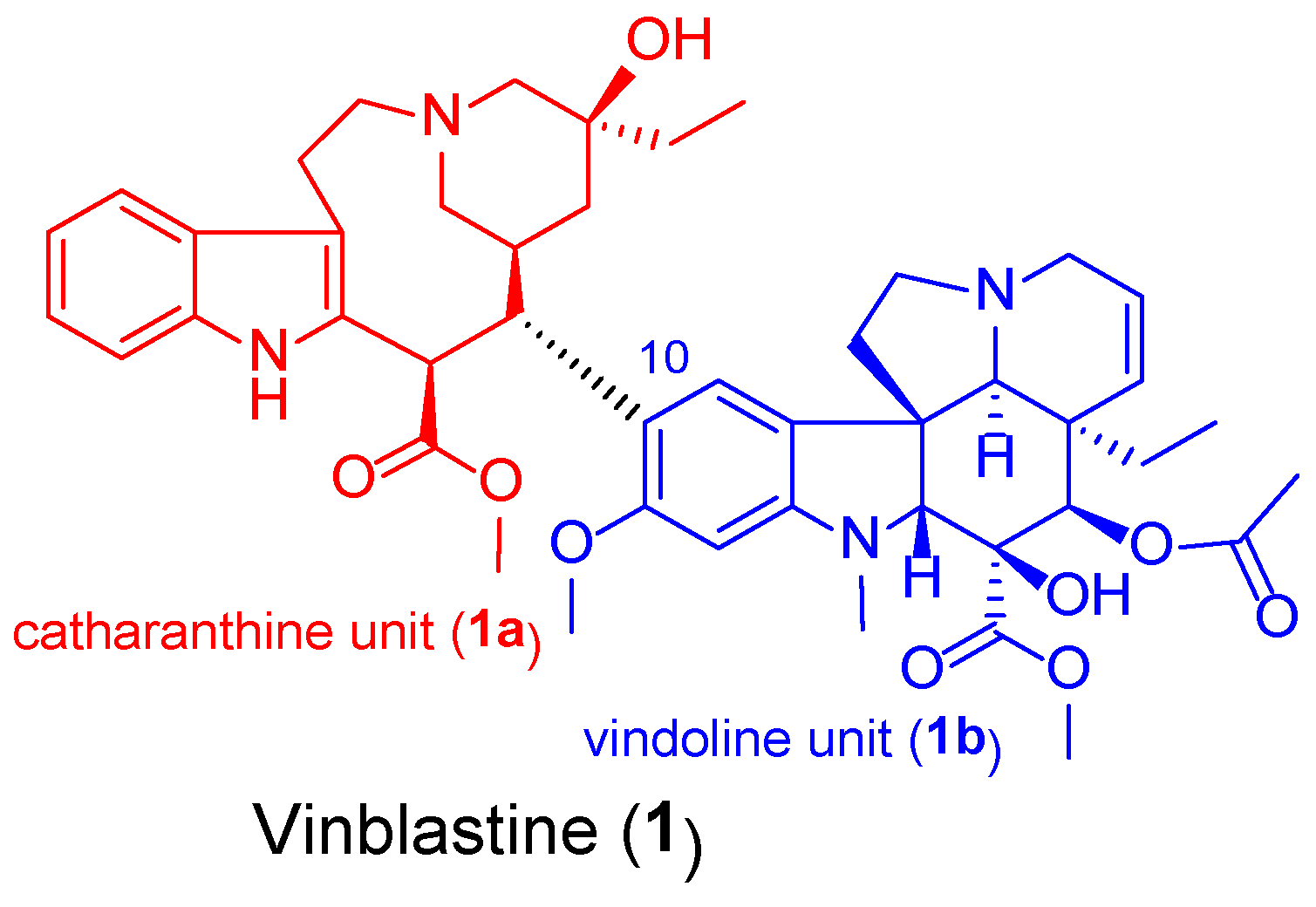

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

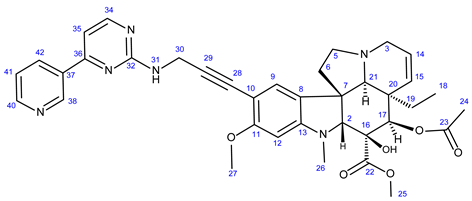

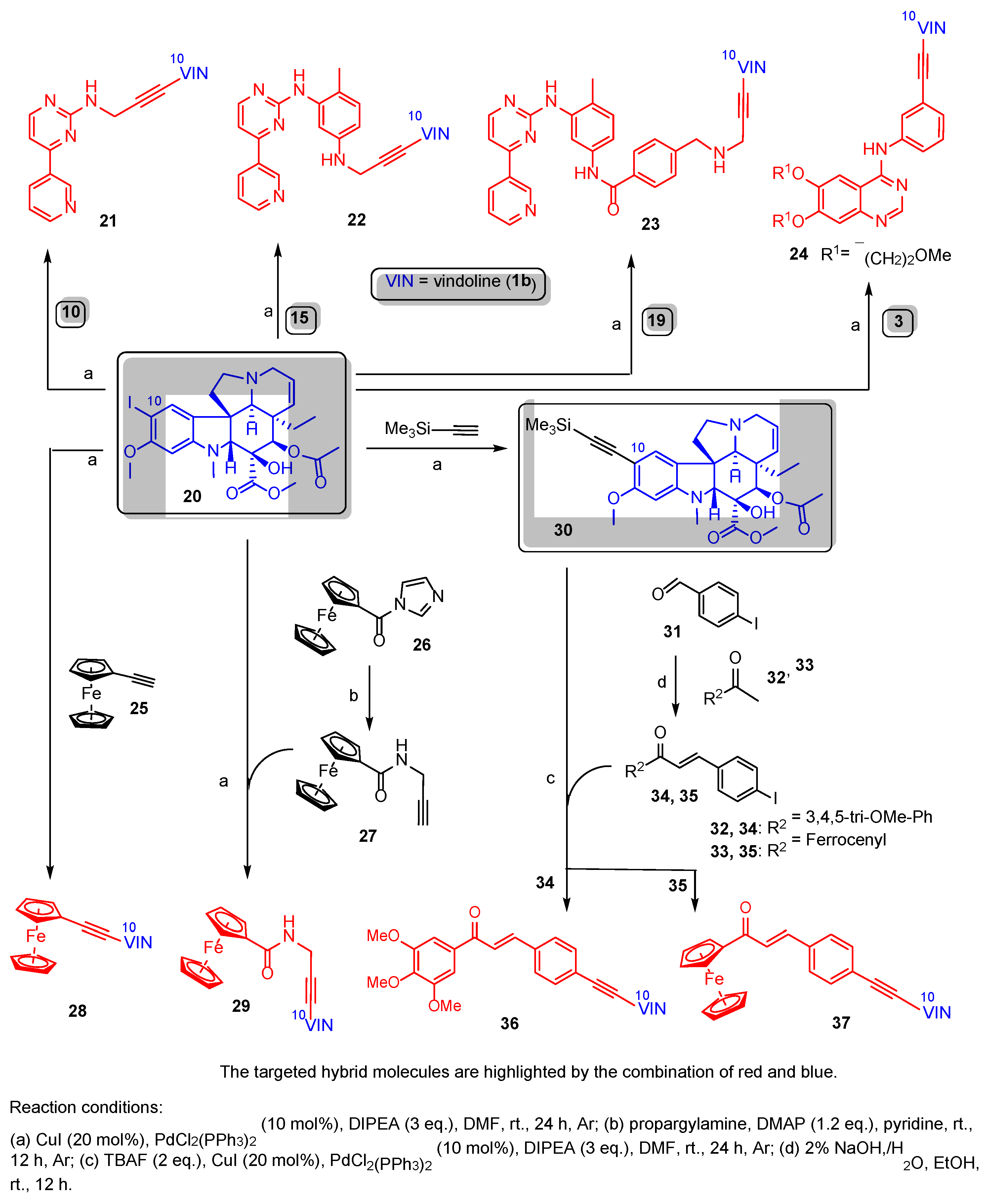

2.1. Multistep Synthesis of the Alkyne-Tethered Vindoline Hybrids

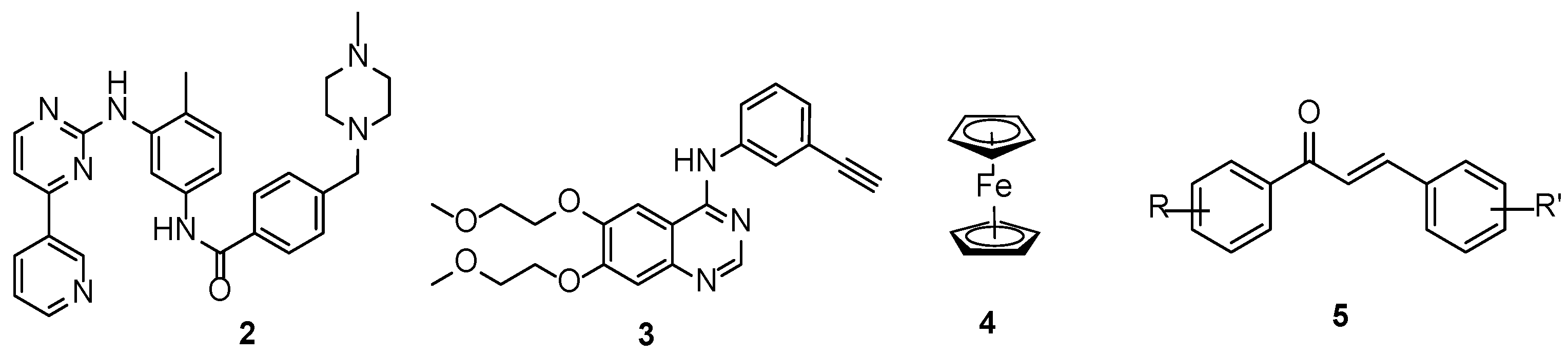

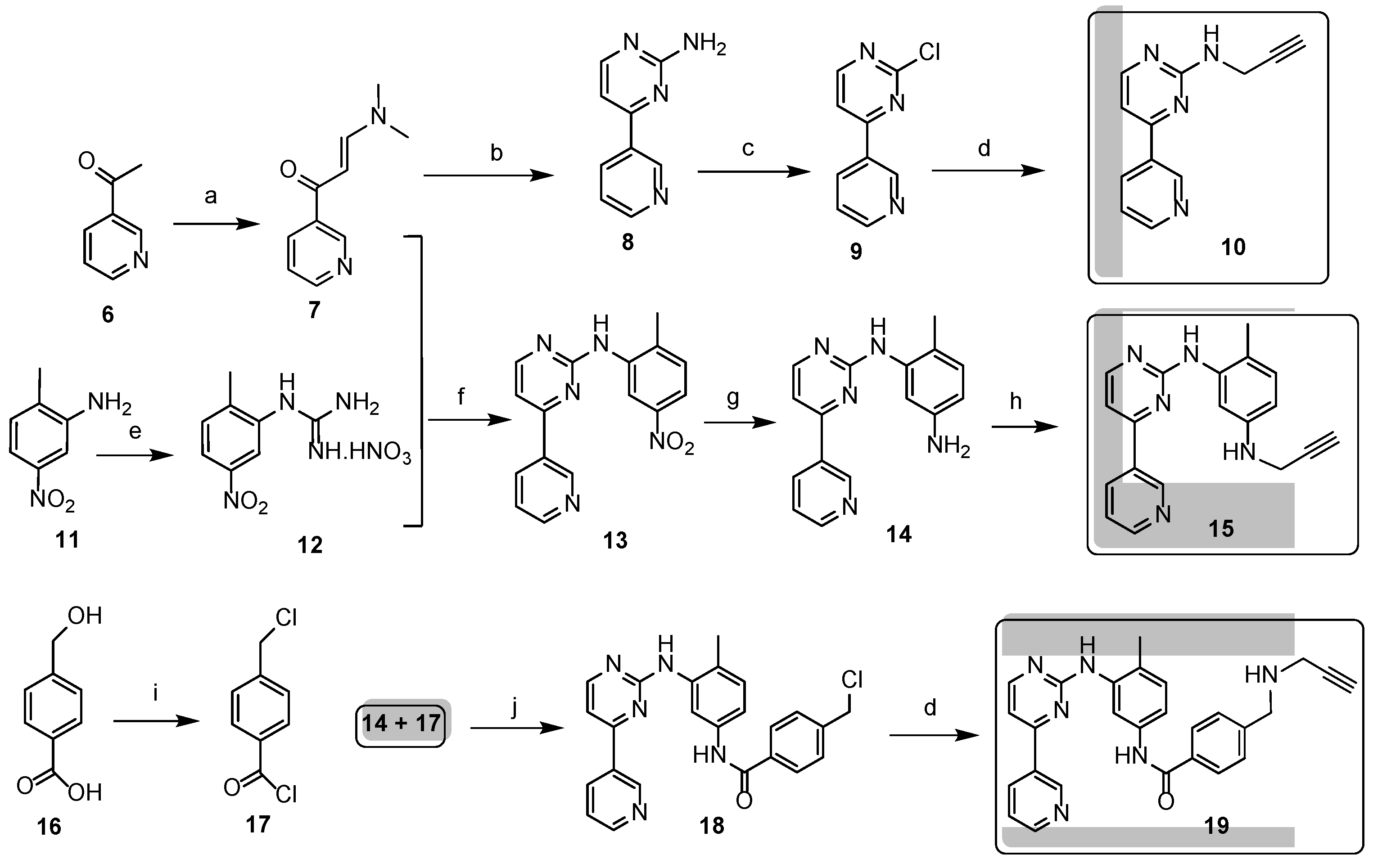

2.1.1. Synthesis of Propargylated Imatinib Fragments

2.1.2. Sonogashira Coupling Reactions Terminating the Synthetic Pathways to the Targeted Alkyne-Tethered Vindoline Hybrids

2.2. In Vitro Antiproliferative Evaluation of the Novel Vindoline Hybrids and Reference Compounds

4. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Propargylated Imatinib Fragments 10 and 19

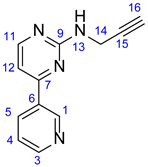

3.1.1. N-(Prop-2-yn-1-yl)-4-(Pyridin-3-yl)Pyrimidin-2-Amine (10)

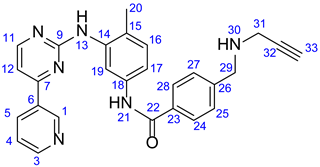

3.1.2. N-(4-Methyl-3-((4-(Pyridin-3-yl)Pyrimidin-2-yl)Amino)Phenyl)-4-((Prop-2-yn-1-Ylamino)-Methyl)- Benzamide (19)

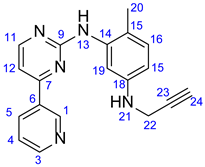

3.2. 4-Methyl-N1-(Prop-2-yn-1-yl)-N3-(4-(Pyridine-3-yl)Pyrimidine-2-yl)Benzene-1,3-Diamine (15)

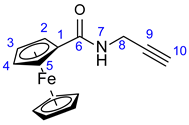

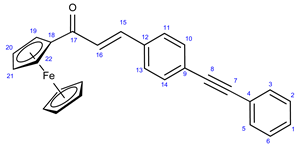

3.3. Synthesis of N-Propargylferrocenecarboxamide (27)

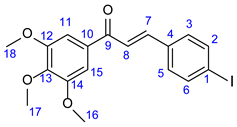

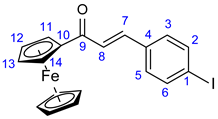

3.4. Synthesis of Iodochalcone Intermediates 34 and 35

3.4.1. (E)-3-(4-Iodophenyl)-1-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)Prop-2-en-1-one (34)

3.4.2. (E)-3-(4-Iodophenyl)-1-Ferrocenylprop-2-en-1-one (35)

3.5. General Procedure for the Sonogashira Reactions Using 10-Iodovindoline (20) as Coupling Partner. Synthesis of Hybrids 21–24, 28, 29 and Silyl-Protected Intermediate 30

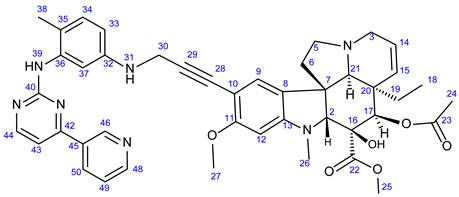

3.5.1. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-(3-((4- Methyl-3-((4-(Pyridin-3-yl)Pyrimidin-2-yl)Amino)Phenyl)Amino)Prop-1-yn-1-yl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (21)

3.5.2. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-(3-((4- Methyl-3-((4-(Pyridin-3-yl)Pyrimidin-2-yl)Amino)Phenyl)Amino)Prop-1-yn-1-yl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (22)

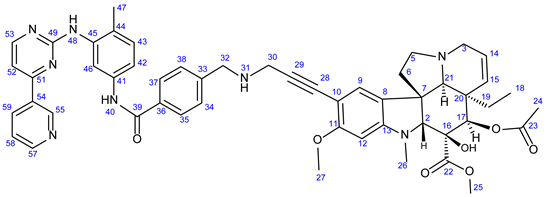

3.5.3. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-(3-((4- ((4-Methyl-3-((4-(Pyridin-3-yl)Pyrimidin-2-yl)Amino)Phenyl)Carbamoyl)Benzyl)Amino)Prop-1-yn-1-yl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (23)

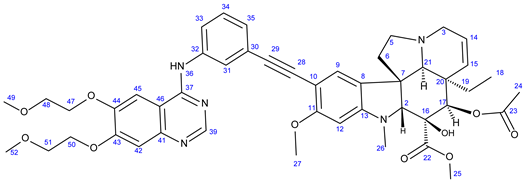

3.5.4. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-9-((3-((6,7-bis(2-Methoxyethoxy)Quinazolin-4-yl)- Amino)Phenyl)Ethynyl)-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (24)

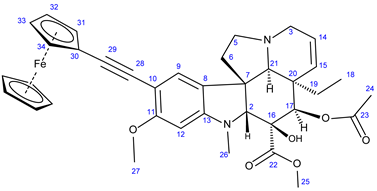

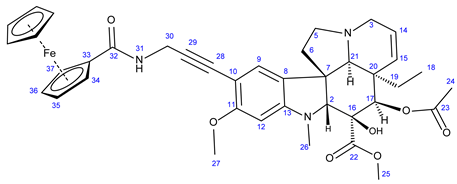

3.5.5. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-(Ferro- Cenylethynyl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (28)

3.5.6. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-9-(3-Ferroceneamidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-3a-Ethyl-5- Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (29)

3.6. Synthesis of Chalcone-Containing Hybrids (36 and 37) by Sonogashira Coupling

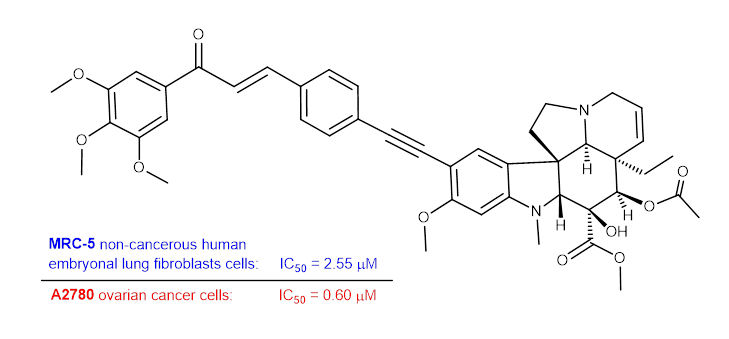

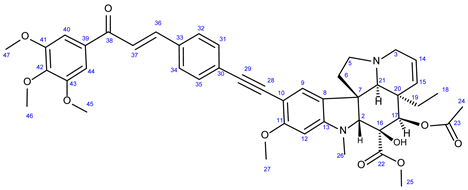

3.6.1. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-((4-((E)- 3-oxo-3-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)Prop-1-en-1-yl)Phenyl)Ethynyl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (36)

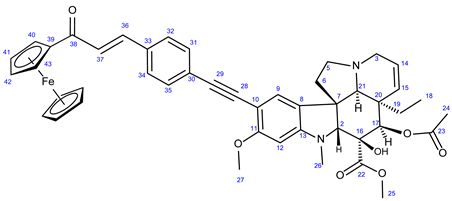

3.6.2. Methyl (3aR,3a1R,4R,5S,5aR,10bR)-4-Acetoxy-3a-Ethyl-5-Hydroxy-8-Methoxy-6-Methyl-9-((4- ((E)-3-oxo-3-Ferrocenylprop-1-en-1-yl)Phenyl)Ethynyl)-3a,3a1,4,5,5a,6,11,12-Octahydro-1H-Indolizino [8,1-cd]Carbazole-5-Carboxylate (37)

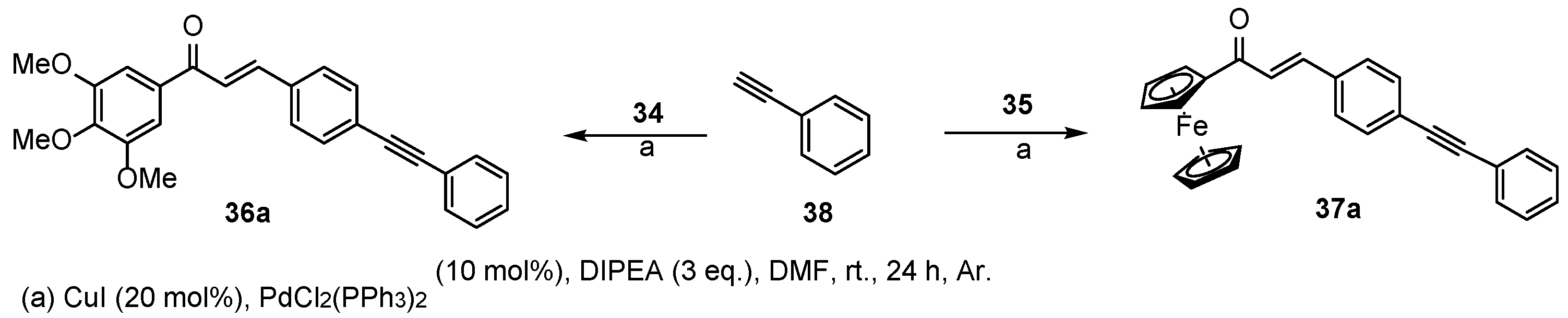

3.7. Synthesis of Reference Chalcone-Containing Hybrids (36a and 37a) by Sonogashira Coupling

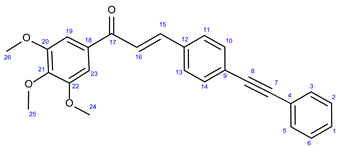

3.7.1. (E)-3-(4-(Phenylethynyl)Phenyl)-1-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)Prop-2-en-1-One (36a)

3.7.2. (E)-1-(Ferrocenyl)-3-(4-(Phenylethynyl)Phenyl)Prop-2-en-1-One (37a)

3.8. Determination of Antiproliferative Activities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. PI3K/AKT pathway as a key link modulates the multidrug resistance of cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mayea, Y.; Mir, C.; Masson, F.; Paciucci, R.; Leonart, M.E. Insights into new mechanisms and models of cancer stem cell multidrug resistance. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020, 60, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuksayan, E.; Ozben, T. Hybrid Compounds as Multitarget Directed Anticancer Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, S.; Bérubé, G. Advances in the development of hybrid anticancer drugs. Expert Op. Drug Disc. 2013, 8, 1029–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, F. Multi-Targeted Anticancer Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 3084–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, P.J.; Phillips, J.R.; Seiner, M.; Cass, C.E. Differential Activity of Vincristine and Vinblastine against Cultured Cells. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 3307–3312. [Google Scholar]

- Isah, T. Anticancer Alkaloids from Trees: Development into Drugs. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2016, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, C.O.; Guo, Z.; Hayes, M.E.; Marks, J.D.; Park, J.W.; Benz, C.C.; Kirpotin, D.B.; Drummond, D.C. Characterization of Highly Stable Liposomal and Immunoliposomal Formulations of Vincristine and Vinblastine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009, 64, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, S.; Chaineau, E.; Fellous, A.; Lataste, H.; Krikorian, A.; Couzinier, J.P.; Meininger, V. Immunofluorescence study of the action of navelbine, vincristine and vinblastine on mitotic and axonal microtubules. Int. J. Cancer 1990, 46, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owellen, R.J.; Owens, A.H.; Donigian, D.W. The binding of vincristine, vinblastine and colchicine to tubulin, Biochem. and Biophys. Res. Comm. 1972, 47, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudi, M.; Go, R.; Yien, C.Y.; Nazre, M. Vinca Alkaloids. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 1231–1235, PMID: 24404355; PMCID: PMC3883245. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, E.; Casamassiva, G.; Castiglione, S.; Cellupica, E.; Pantalone, S.; Papagni, F.; Rui, M.; Siciliano, A.M.; Collina, S. Vinca alkaloids and analogues as anticancer agents: Looking back, peering ahead. Bioorg & Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2816–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keglevich, A.; Dányi, L.; Rieder, A.; et al. ; Synhesis and Cytotoxic Activity of New Vindoline Derivatives Coupled to Natural and Synthetic Pharmacophores. Molecules. 2020, 25, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, A.; Zsiros, V.; Keglevich, P.; Szigetvári, Á.; et al. ; Synthesis and In Vitro Antitumor Effect of New Vindoline-steroid Hybrids. Curr. Org. Chem. 2019, 23, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Keglevich, P.; Hazai, L. Vinca Hybrids with Antiproliferative Effect. Med. Res. Arch. 2022, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Iqbal, N. Imatinib: a breakthrough of targeted therapy in cancer. Chemotherapy research and practice 2014, 357027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Kong, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Shen, H. Severe megaloblastic anemia in a patient with advanced lung adenocarcinoma during treatment with erlotinib: a case report and literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, P.; Hazai, L.; Gorka-Kereskényi, Á.; Péter, L.; Gyenese, J.; Lengyel, Z.; Kalaus, G.; Dubrovay, Z.; Dékány, M.; Orbán, E.; Bánóczi, Z.; Szántay, Cs., Jr.; Szántay, C. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor effect of new vindoline derivatives coupled with amino acid esters. Heterocycles 2013, 87, 2299–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, A.; Dányi, L.; Rieder, A.; Horváth, D.; Szigetvári, Á.; Dékány, M.; Szántay, C., Jr.; Latif, A.D.; Hunyadi, A.; Zupkó, I.; Keglevich, P.; Hazai, L. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of New Vindoline Derivatives Coupled to Natural and Synthetic Pharmacophores. Molecules 2020, 25, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keglevich, A.; Zsiros, V.; Keglevich, P.; Szigetvári, Á.; Dékány, M.; Szántay, C., Jr.; Mernyák, E.; Wölfling, J.; Hazai, L. Synthesis and In Vitro Antitumor Effect of New Vindoline-steroid Hybrids. Current Organic Chemistry 2019, 23, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpf-Maier, P.; Köpf, H.; Neuse, E.W. Ferricenium complexes: A new type of water-soluble antitumor agent. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1984, 108, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoupilova, H.; Bartosik, M.; Sommerova, L.; Pinkas, J.; Vaculovic, T.; Kanicky, V.; Karban, J.; Hrstka, R. Ferrocenes as new anticancer drug candidates: Determination of the mechanism of action. Eur. J. Pharm. 2020, 867, 172825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Věžník, J.; Konhefr, M.; Fohlerová, Z.; Lacina, K. ; Redox-dependent cytotoxicity of ferrocene derivatives and ROS-activated prodrugs based on ferrocenyliminoboronates. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 224, 111561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, J.; Das, R.; Kamble, S.; Chowdhury, M.G.; Kapoor, S.; Gupta, A.; Vyas, H.; Shard, A. Ferrocene-based modulators of cancer-associated tumor pyruvate kinase M2. J. Organomet. Chem 2022, 968–969, 122338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yue, K.; Fan, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Qin, M.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of ferrocene-based hydroxamic acids as selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 246, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Weitao, W.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y. Ferrocene-containing hybrids as potential anticancer agents: Current developments, mechanisms of action and structure-activity relationships. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 190, 112109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnier, P.; Galopin, N.; Yann Sibiril, Y.; Clavreul, A.; Cayon, J.; Briganti, A.; Legras, P.; Vessières, A.; Montier, T.; Jaouen, G.; Benoit, J.-P.; Passirani, C. Efficient ferrocifen anticancer drug and Bcl-2 gene therapy using lipid nanocapsules on human melanoma xenograft in mouse. Pharmacological Res. 2017, 126, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornelas, C. Application of ferrocene and its derivatives in cancer research. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.S.; Silva, A.M.S. A New Age for Iron: Antitumoral Ferrocenes. Organometallics 2013, 32, 5626–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirante, J.; Dubar, F.; González, A.; Lopez, C.; Cascante, M.; Cortés, R.; Forfar, I.; Pradines, B.; Biot, C. Ferrocene-indole hybrids for cancer and malaria therapy. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Vick, J.; Acevedo, C.; Melendez, E.; Singh, S. Cytotoxicity and Reactive Oxygen Species Generated by Ferrocenium and Ferrocene on MCF7 and MCF10A Cell Lines. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2012, 4, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Renschler, M.F. The emerging role of reactive oxygen species in cancer therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2004, 40, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, S.; Vessières, A.; Leclercq, G.; Quivy, J.; Tang, J.; Vaissermann, J.; Huché, M.; Jaouen, G. Synthesis, biochemical properties and molecular modelling studies of organometallic specific estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), the ferrocifens and hydroxyferrocifens: evidence for an antiproliferative effect of hydroxyferrocifens on both hormone-dependent and hormone-independent breast cancer cell lines. Chemistry 2003, 9, 5223–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csókás, D.; Károlyi, B.I.; Bősze, S.; Szabó, I.; Báti, G.; Drahos, L.; Csámpai, A. 2,3-Dihydroimidazo [1,2-b]ferroceno[d]pyridazines and a 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrimido [1,2-b]ferroceno[d]pyridazine: Synthesis, structure and in vitro antiproliferation activity on selected human cancer cell lines. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 750, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernei, T.; Bősze, S.; Szabó, R.; Hudecz, F.; Majrik, K.; Csámpai, A. N-ferrocenylpyridazinones and new organic analogues: Synthesis, cyclic voltammetry, DFT analysis and in vitro antiproliferative activity associated with ROS-generation. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 6181–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, N.-E.E.; Boulhaoua, M.; Hutai, D.; Oláh-Szabó, R.; Bősze, S.; Hudecz, F.; Csámpai, A. Synthetic and DFT Modeling Studies on Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions of 4,5-Dibromo-2-methylpyridazin-3(2H)-one with Ferrocene Boronates, Accompanied by Hydrodebromination and a Novel Bridge-Forming Annulation In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of the Ferrocenyl–Pyridazinone Products. Catalysts 2022, 12, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, P. Heterocyclic chalcone analogues as potential anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 422–432. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Moorthy, N.S.; Ramasamy, S.; Vanam, U.; Manivannan, E.; Karunagaran, D.; Trivedi, P. Advances in chalcones with anticancer activities. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov 2015, 10, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, D.K.; Bharti, S.K.; Asati, V. Anti-cancer chalcones: Structural and molecular target perspectives. Eur J Med Chem 2015, 98, 69–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Huang, G.; Xiao, J. Chalcone hybrids as potential anticancer agents: Current development, mechanism of action, and structure-activity relationship. Med Res Rev 2020, 40, 2049–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Sood, A.K.; Goyal, K.; Singh, A.; Sharma, V.; Guliya, N.; Gulati, S.; Kumar, S. Chalcone Scaffolds as Anticancer Drugs: A Review on Molecular Insight in Action of Mechanisms and Anticancer Properties. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1650–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernei, T.; Duró, C.; Dembo, A.; Lajkó, E.; Takács, A.; Kőhidai, L.; Schlosser, G.; Csámpai, A. Synthesis, Structure and In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of Novel Cinchona-Chalcone Hybrids with 1,4-Disubstituted- and 1,5-Disubstituted 1,2,3-Triazole Linkers. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, B.; Johnson, T.E.; Lad, R.; Xing, C. Structure-activity relationship studies of chalcone leading to 3-hydroxy-4,3’,4’,5’-tetramethoxychalcone and its analogues as potent nuclear factor kappaB inhibitors and their anticancer activities. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7228–7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Iqbal, M.; Ullah, R.; Zahra, R.; Chotana, G.A.; Faisal, A.; Saleem, R.S.Z. Synthesis and evaluation of novel α-substituted chalcones with potent anticancer activities and ability to overcome multidrug resistance. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Gao, M.; Diao, Q.; Gao, F. Chalcone Derivatives and their Activities against Drug-resistant Cancers: An Overview. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Li, C.; He, L.; Lei, K.; Wang, F.; Pu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cao, D.; Ma, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of pyrano chalcone derivatives containing indole moiety as novel anti-tubulin agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2060–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, J.; Huang, L.; Li, X. Synthesis, Evaluation, and Mechanism Study of Novel Indole-Chalcone Derivatives Exerting Effective Antitumor Activity Through Microtubule Destabilization in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 5264–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.D.; Sohn, J.-H.; Rawal, V.H. Synthesis of C-15 Vindoline Analogues by Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7899–7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, A.; Dembitsky, V. Acetylenic anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 132–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Park, E.J. Cytotoxic anticancer candidates from natural resources. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 2002, 2, 485–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Bioactive C(17) and C(18) Acetylenic Oxylipins from Terrestrial Plants as Potential Lead Compounds for Anticancer Drug Development. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Dong, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W. Synthesis of novel natural product-like diaryl acetylenes as hypoxia inducible factor-1 inhibitors and antiproliferative agents. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13878–13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shao, Y.; Li, K.; Xia, W. Bioactive selaginellins from Selaginella tamariscina (Beauv.) Spring. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1884–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.G.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, H.M.; Ma, E.L.; Guan, J.; Xue, F.N.; Liu, H.X.; Sun, X.Y. Isolation and cytotoxic activity of selaginellin derivatives and biflavonoids from Selaginella tamariscina. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Carter-Cooper, B.; Du, Y.; Zhou, J.; Saeed, M.A.; Liu, J.; Guo, M.; Roembke, B.; Mikek, C.; Lewis, E.A.; et al. Alkyne-substituted diminazene as G-quadruplex binders with anticancer activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 118, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Said, R.; Falchook, G.; Naing, A.; Moulder, S.; Tsimberidou, A.-M.; Galluppi, G.; Dakappagari, N.; Storgard, C.; Kurzrock, R.; et al. Phase I Study of BIIB028, a Selective Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor, in Patients with Refractory Metastatic or Locally Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4824–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, J.; Carter, T.R.; Cohen, M.S.; Blagg, B.S.J. Old and New Approaches to Target the Hsp90 Chaperone. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2020, 20, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, C.; Song, C. Pan- and isoform-specific inhibition of Hsp90: Design strategy and recent advances. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-F.; Wang, C.-L.; Bai, Y.-J.; Han, N.; Jiao, J.-P.; Qi, X.-L. A Facile Total Synthesis of Imatinib Base and Its Analogues. Organic Process Research & Development. 2008, 12, 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, C.; Cook, L.; Levendis, D.C. An investigation of the chemistry of ferrocenoyl derivatives. The synthesis and reactions of ferrocenoyl imidazolide and its derivatives. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 637–639, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Conc. (µM) | Mean Growth Inhibition (%) ± SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRC-5 | MDA-MB-231 | HeLa | A2780 | SH-SY5Y | ||

| 21 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 < 20 |

| 30 | < 20 | 21.41 ± 1.22 | 29.46 ± 1.03 | |||

| 22 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | 24.69 ± 2.03 | < 20 94.91 ± 1.85 |

| 30 | 89.92 ± 0.65 | 43.95 ± 1.74 | 97.13 ± 0.40 | |||

| 23 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 < 20 |

| 30 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |||

| 24 | 10 | < 20 | 47.84 ± 2.98 | < 20 | 75.74 ± 2.55 | 53.41 ± 0.89 |

| 30 | < 20 | 80.37 ± 1.83 | < 20 | 88.05 ± 1.08 | 82.74 ± 2.85 | |

| 28 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 |

| 30 | < 20 | < 20 | 49.19 ± 1.98 | < 20 | ||

| 29 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 91.64 ± 1.10 |

| 30 | 23.99 ± 0.81 | < 20 | 68.02 ± 1.37 | |||

| 36 | 10 | 87.09 ± 2.73 | 86.22 ± 0.79 | 89.62 ± 0.75 | 95.09 ± 0.50 | 89.00 ± 2.61 |

| 30 | 88.90 ± 2.80 | 85.01 ± 0.87 | 89.98 ± 0.46 | 94.50 ± 0.35 | 89.10 ± 2.74 | |

| 36a | 10 | 46.14 ± 2.17 | 86.37 ± 0.71 | 90.55 ± 0.72 | 95.53 ± 0.34 | 90.01 ± 2.84 |

| 30 | 89.88 ± 3.24 | 86.28 ± 0.47 | 90.29 ± 0.28 | 95.07 ± 0.27 | 91.67 ± 3.36 | |

| 37 | 10 | Not tested | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 < 20 |

| 30 | < 20 | < 20 | 31.96 ± 2.40 | |||

| 37a | 10 | 27.48 ± 2.20 | 70.70 ±1.61 | 51.26 ± 0.79 | 57.17 ± 1.48 | < 20 |

| 30 | 52.25 ± 2.01 | 80.99 ± 1.49 | 71.19 ± 2.86 | 81.63 ± 2.56 | 51.77 ± 3.06 | |

| 1b | 10 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 |

| 30 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |

| Compound | IC50 (µM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 | HeLa | A2780 | SH-SY5Y | MRC-5 | |

| 29 | 11.78 | n.d. | 5.62 | 10.33 | n.d. |

| 36 | 1.15 (2.22a) | 1.57 (1.62a) | 0.60 (4.25a) | 1.26 (2.02a) | 2.55 |

| 36a | 4.22 (2.59a) | 4.54 (2.40a) | 3.26 (3.35a) | 5.60 (1.95a) | 10.92 |

| 37a | 7.79 (3.52a) | 11.47 (2.39a) | 8.84 (3.10a) | 29.16 (0.94a) | 27.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).