Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

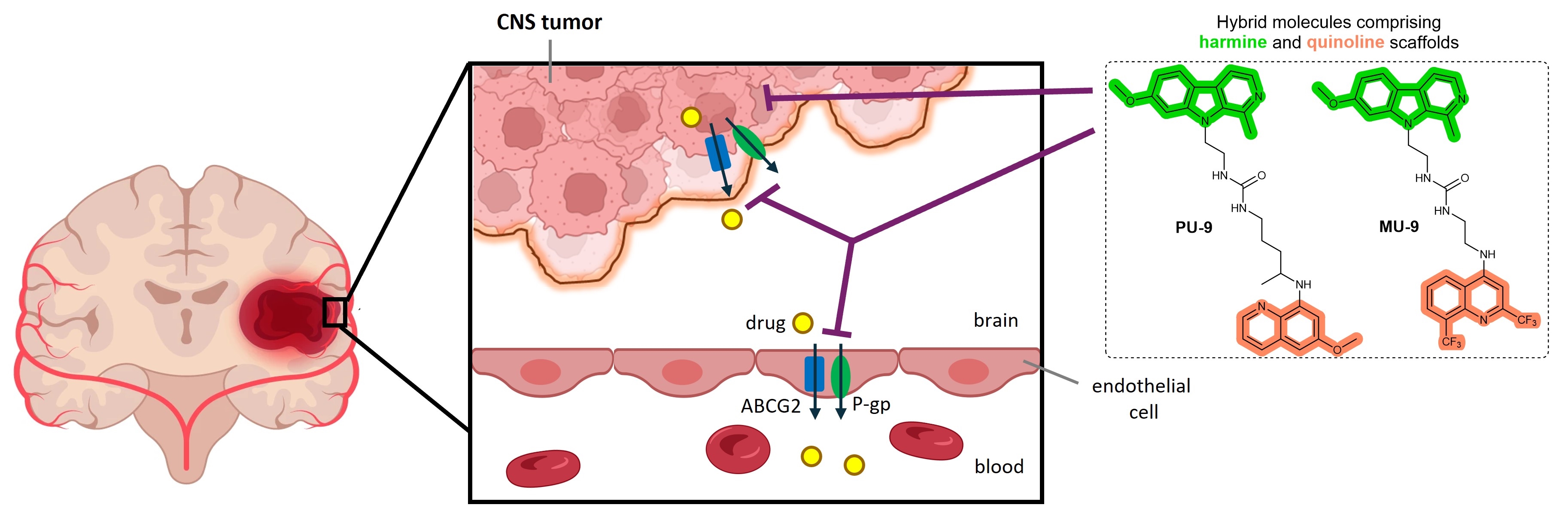

1. Introduction

2. Results

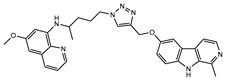

2.1. Synthesis of hybrid compounds

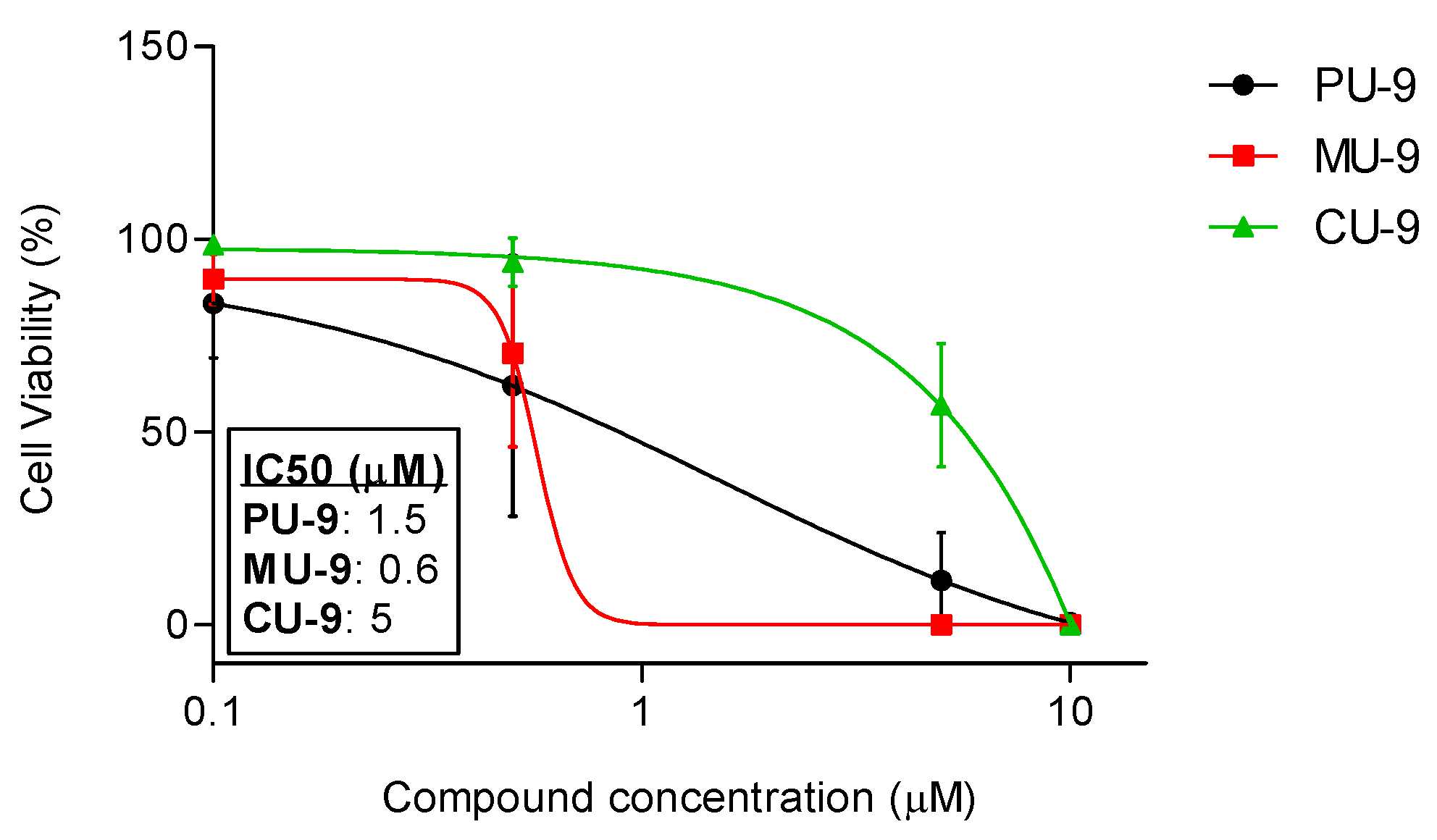

2.2. In vitro antiproliferative activity

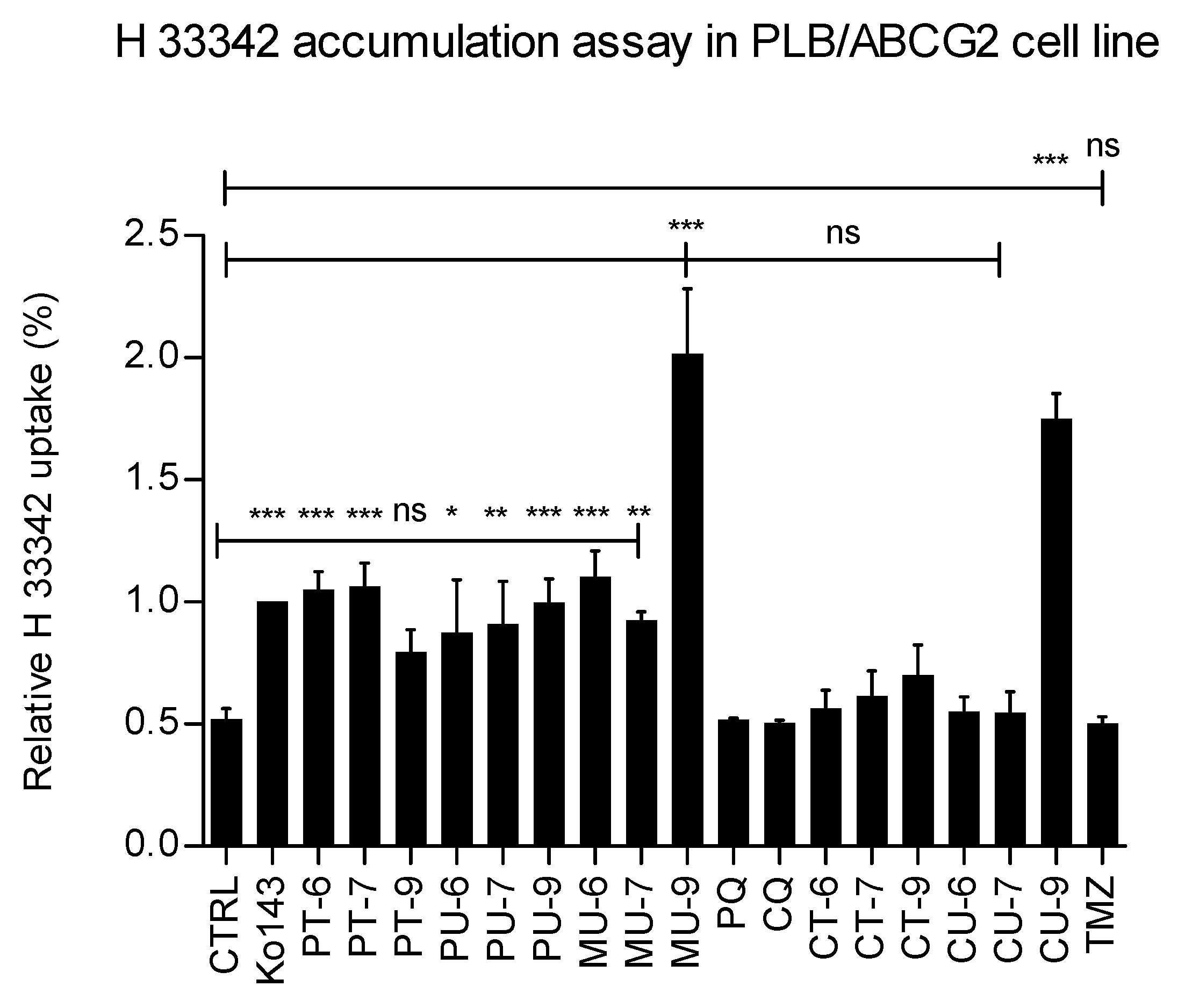

2.3. Effects of hybrids on ABCG2-mediated fluorescent substrate accumulation in model cells

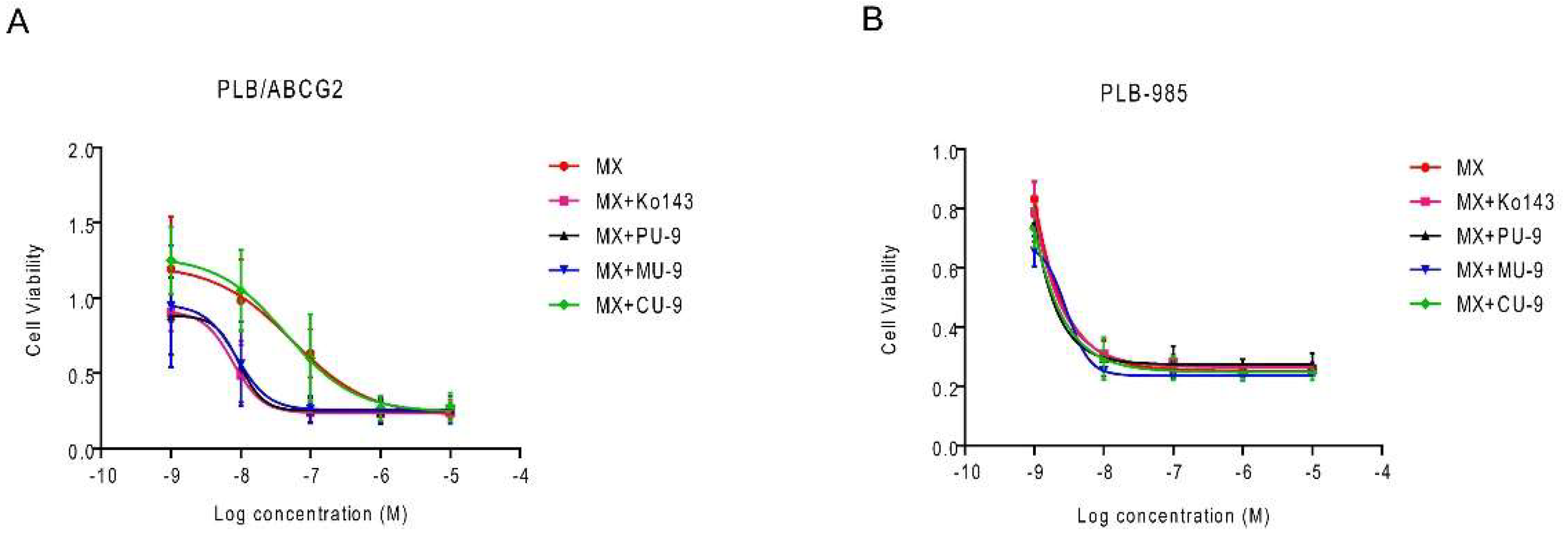

2.4. Sensitization of ABCG2-expressing tumor cells to mitoxantrone by hybrid compounds

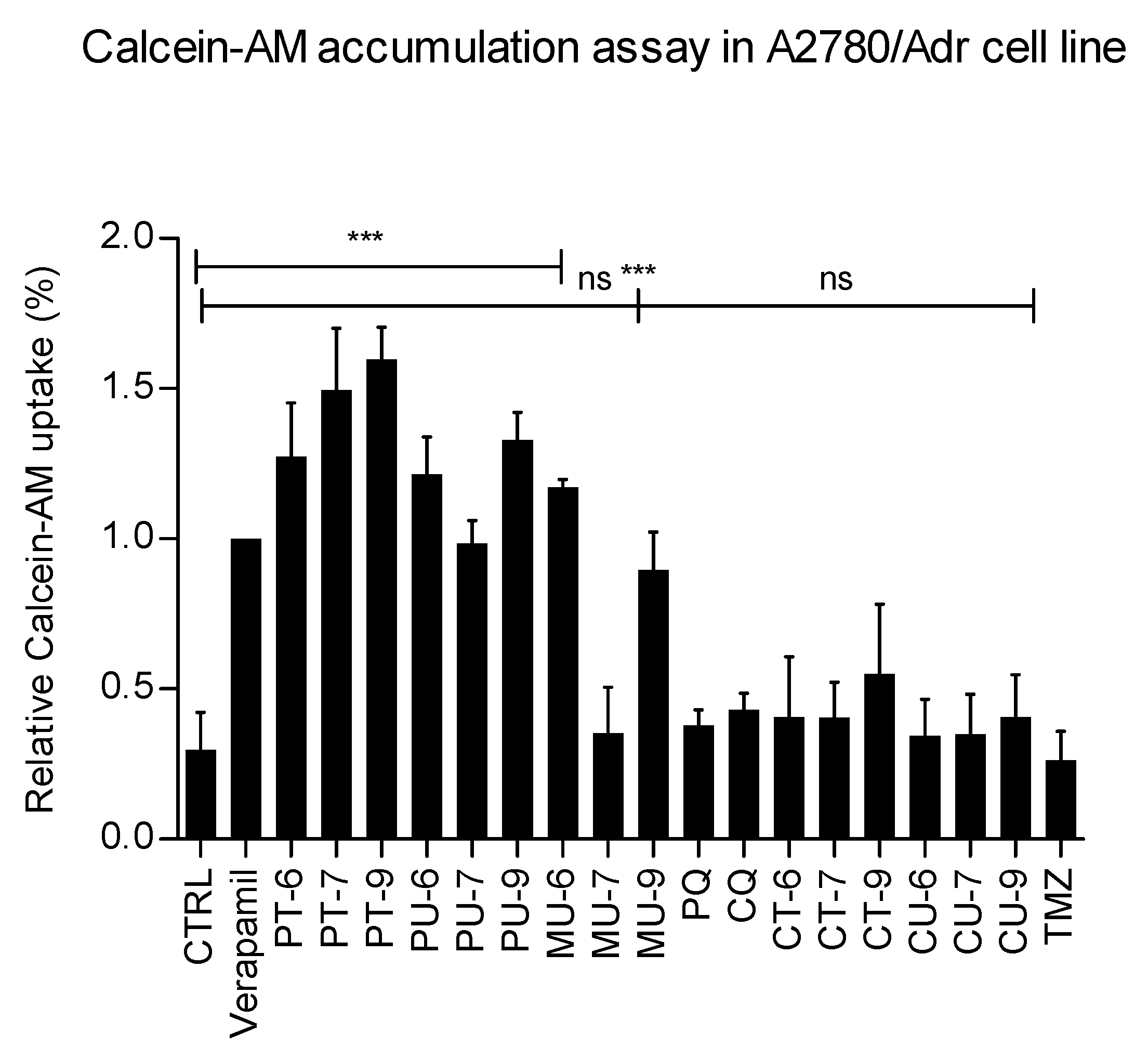

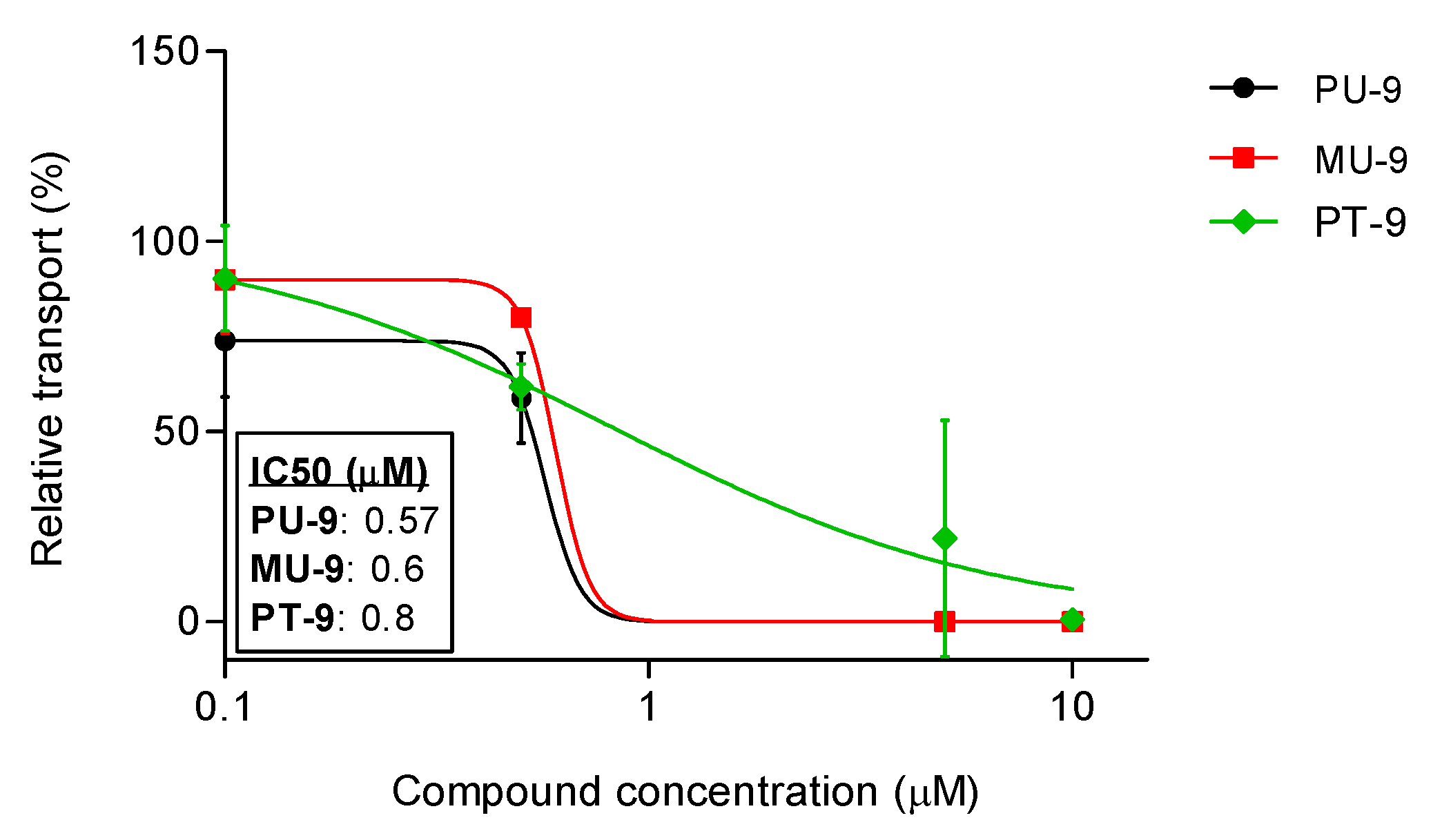

2.5. Effects of hybrids on P-gp-mediated fluorescent substrate accumulation in model cells

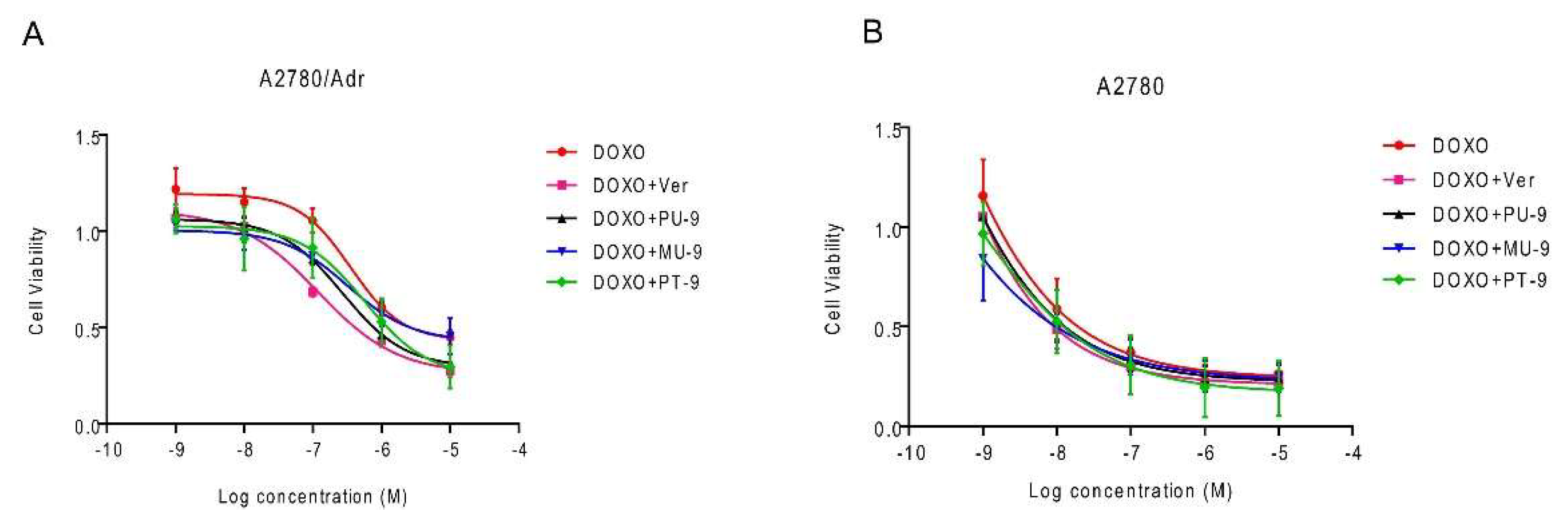

2.6. Sensitization of P-gp-expressing tumor cells to doxorubicine by hybrid compounds

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell lines

4.3. Cell proliferation assay

4.4. Calcein-AM accumulation assay

4.5. Hoechst 33342 uptake assay

4.6. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kucuksayan, E.; Ozben, T. Hybrid Compounds as Multitarget Directed Anticancer Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavić, K.; Poje, G.; Pessanha de Carvalho, L.; Tandarić, T.; Marinović, M.; Fontinha, D.; Held, J.; Prudêncio, M.; Piantanida, I.; Vianello, R.; et al. Discovery of Harmiprims, Harmine-Primaquine Hybrids, as Potent and Selective Anticancer and Antimalarial Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumilak, M.; Wiktorowska-Owczarek, A.; Stanczak, A. Hybrid Drugs—A Strategy for Overcoming Anticancer Drug Resistance? Mol. 2021, Vol. 26, Page 2601 2021, 26, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C.; et al. Drug Repurposing: Progress, Challenges and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorc, B.; Perković, I.; Pavić, K.; Rajić, Z.; Beus, M. Primaquine Derivatives: Modifications of the Terminal Amino Group. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Q.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Xu, Z.; Feng, L.S.; Wu, X.; Zhao, F. Quinoline Hybrids and Their Antiplasmodial and Antimalarial Activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 139, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, D.J.; Jaszczak, M.K.; Boratyński, P.J. A Review of Modifications of Quinoline Antimalarials: Mefloquine and (Hydroxy)Chloroquine. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.; Eze, E.; Raimi-Abraham, B.T. Malaria and Cancer: A Critical Review on the Established Associations and New Perspectives. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2021, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Woon, C.Y.N.; Liu, C.G.; Cheng, J.T.; You, M.; Sethi, G.; Wong, A.L.A.; Ho, P.C.L.; Zhang, D.; Ong, P.; et al. Repurposing Artemisinin and Its Derivatives as Anticancer Drugs: A Chance or Challenge? Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 828856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.S.; Zou, C.; Zhang, J. Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Song, X. A Comprehensive Overview of β-Carbolines and Its Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Yu, S. Pharmacological Effects of Harmine and Its Derivatives: A Review. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2020 4312 2020, 43, 1259–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahinas, D.; MacMullin, G.; Benedict, C.; Crandall, I.; Pillaid, D.R. Harmine Is a Potent Antimalarial Targeting Hsp90 and Synergizes with Chloroquine and Artemisinin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wink, M. The Beta-Carboline Alkaloid Harmine Inhibits BCRP and Can Reverse Resistance to the Anticancer Drugs Mitoxantrone and Camptothecin in Breast Cancer Cells. Phyther. Res. 2010, 24, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, G.; Marinović, M.; Pavić, K.; Mioč, M.; Kralj, M.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Held, J.; Perković, I.; Rajić, Z. Harmicens, Novel Harmine and Ferrocene Hybrids: Design, Synthesis and Biological Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, K.; Poje, G.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Held, J.; Rajić, Z. Synthesis, Antiproliferative and Antiplasmodial Evaluation of New Chloroquine and Mefloquine-Based Harmiquins. Acta Pharm. 2023, 73, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, G.; Pessanha de Carvalho, L.; Held, J.; Moita, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Perković, I.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Rajić, Z. Design and Synthesis of Harmiquins, Harmine and Chloroquine Hybrids as Potent Antiplasmodial Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džimbeg, G.; Zorc, B.; Kralj, M.; Ester, K.; Pavelić, K.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; Balzarini, J.; De Clercq, E.; Mintas, M. The Novel Primaquine Derivatives of N-Alkyl, Cycloalkyl or Aryl Urea: Synthesis, Cytostatic and Antiviral Activity Evaluations. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perković, I.; Raić-Malić, S.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Pessanha de Carvalho, L.; Held, J.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Zorc, B.; Rajić, Z. Harmicines − Harmine and Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Novel Antiplasmodial Hits. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 187, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinović, M.; Perković, I.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Held, J.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Zorc, B.; Rajić, Z. Novel Harmicines with Improved Potency against Plasmodium. Mol. 2020, Vol. 25, Page 4376 2020, 25, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajić, K.P.Z.; Mlinarić, Z.; Uzelac, L.; Kralj, M.; Zorc, B. Chloroquine Urea Derivatives: Synthesis and Antitumor Activity in Vitro. Acta Pharm. 2018, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, G.; Šakić, D.; Marinović, M.; You, J.; Tarpley, M.; Williams, K. P.; Golub, N.; Dernovšek, J.; Tomašić, T.; Bešić, E.; Rajić, Z. Unveiling the Antiglioblastoma Potential of Harmicens, Harmine and Ferrocene Hybrids. Acta Pharm. 2024, 74, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guberović, I.; Marjanović, M.; Mioč, M.; Ester, K.; Martin-Kleiner, I.; Šumanovac Ramljak, T.; Mlinarić-Majerski, K.; Kralj, M. Crown Ethers Reverse P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Faujdar, C.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, S.; Malik, B.; Nepali, K.; Liou, J.P. Glioblastoma: Current Status, Emerging Targets, and Recent Advances. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8596–8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gooijer, M.C.; de Vries, N.A.; Buckle, T.; Buil, L.C.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Boogerd, W.; van Tellingen, O. Improved Brain Penetration and Antitumor Efficacy of Temozolomide by Inhibition of ABCB1 and ABCG2. Neoplasia 2018, 20, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Lv, Y.X.; Guo, C.Y.; Xiao, Z.M.; Jiang, Q.G.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, W.H.; Hu, P. Harmine Inhibits the Proliferation and Migration of Glioblastoma Cells via the FAK/AKT Pathway. Life Sci. 2021, 270, 119112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyerhäuser, P.; Kantelhardt, S.R.; Kim, E.L. Re-Purposing Chloroquine for Glioblastoma: Potential Merits and Confounding Variables. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; De Gooijer, M.C.; Roig, E.M.; Buil, L.C.M.; Christner, S.M.; Beumer, J.H.; WEurdinger, T.; Beijnen, J.H.; Van Tellingen, O. ABCB1, ABCG2, and PTEN Determine the Response of Glioblastoma to Temozolomide and ABT-888 Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2703–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, J.; Fukuda, Y.; Schuetz, J.D. Obstacles to Brain Tumor Therapy: Key ABC Transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, Vol. 18, Page 2544 2017, 18, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréan, A.; Rosenberg, S.; Lejeune, F.X.; Goli, L.; Nadaradjane, A.A.; Guehennec, J.; Schmitt, C.; Verreault, M.; Bielle, F.; Mokhtari, K.; et al. ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters: Expression and Clinical Value in Glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2018, 138, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, A.; Rahman, H.; Ambudkar, S. V. Advances in the Structure, Mechanism and Targeting of Chemoresistance-Linked ABC Transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mioč, M.; Telbisz, Á.; Radman, K.; Bertoša, B.; Šumanovac, T.; Sarkadi, B.; Kralj, M. Interaction of Crown Ethers with the ABCG2 Transporter and Their Implication for Multidrug Resistance Reversal. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begicevic, R.R.; Falasca, M. ABC Transporters in Cancer Stem Cells: Beyond Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radtke, L.; Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Awortwe, C.; Vater, I.; Nagel, I.; Sebens, S.; Cascorbi, I.; Kaehler, M. CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Knockout Reveals the Role of ABCB1 in the Response to Temozolomide, Carmustine and Lomustine in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 185, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, A.R.; Kim, Y.K.; Yoon, S. Co-Treatment with the Anti-Malarial Drugs Mefloquine and Primaquine Highly Sensitizes Drug-Resistant Cancer Cells by Increasing P-Gp Inhibition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 441, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, I.; Beus, M.; Stochaj, U.; Le, P.U.; Zorc, B.; Rajić, Z.; Petrecca, K.; Maysinger, D. Inhibition of Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation, Invasion, and Mechanism of Action of a Novel Hydroxamic Acid Hybrid Molecule. Cell Death Discov. 2018 41 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, A.; Stefan, K.; Wiese, M. Synthesis and Investigation of Tetrahydro-β-Carboline Derivatives as Inhibitors of the Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2). J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6121–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Solórzano, D.; Stark, S.A.; König, B.; Sierra, C.A.; Ochoa-Puentes, C. ABCG2/BCRP: Specific AndNonspecific Modulators. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 987–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujhelly, O.; Özvegy, C.; Várady, G.; Cervenak, J.; Homolya, L.; Grez, M.; Scheffer, G.; Roos, D.; Bates, S.E.; Váradi, A.; et al. Application of a Human Multidrug Transporter (ABCG2) Variant as Selectable Marker in Gene Transfer to Progenitor Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003, 14, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telbisz, Á.; Ambrus, C.; Mózner, O.; Szabó, E.; Várady, G.; Bakos, É.; Sarkadi, B.; Özvegy-Laczka, C. Interactions of Potential Anti-COVID-19 Compounds with Multispecific ABC and OATP Drug Transporters. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IC50/µM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. | Cell line | |||

| Structure | U251 | SH-SY5Y | Hek293T | |

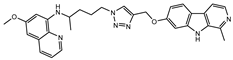

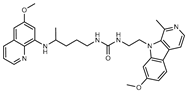

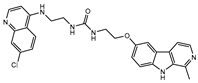

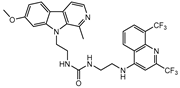

| PT-6 |  |

4.4±0.3 | >100 | 25.2±3.6a |

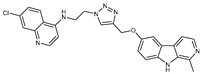

| PT-7 |  |

2.9±1.7 | >100 | 7.6±0.01a |

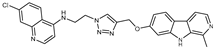

| PT-9 |  |

33.5±3 | >100 | >50a |

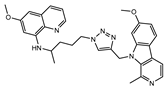

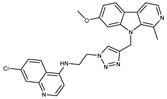

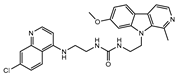

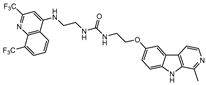

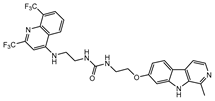

| PU-6 |  |

4±0.4 | 8.2±0.9 | 12±0.9a |

| PU-7 |  |

4±0.5 | 7.4±0.3 | 7.6±0.007a |

| PU-9 |  |

4±0.6 | 7.5±0.7 | 13±0.06a |

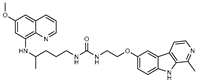

| CT-6 |  |

5±0.4 | 72±28 | >50 |

| CT-7 |  |

3.6±0.4 | 8.6±0.5 | 5.7±0.13 |

| CT-9 |  |

4.5±0.09 | 8.8±1 | 26.1±0.4 |

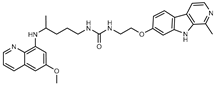

| CU-6 |  |

35.7±25.3 | >100 | >50b |

| CU-7 |  |

6.3±0.8 | >100 | 38.8±.5b |

| CU-9 |  |

4.6±0.4 | >100 | 5.5±0.3b |

| MU-6 |  |

1.8±0.3 | 6.2±0.04 | 3.1±0.03b |

| MU-7 |  |

0.6±0.2 | 7.5±4.5 | 16.8±0.2b |

| MU-9 |  |

4±0.3 | 7.9±1.6 | 7.8±0.1b |

| PQc | 44.3±3 | >100 | 37.6±0.6a | |

| CQd | 24±0.95 | 77.8±18 | n.te | |

| HARf | 20 ± 1.7g | n.te | 21±3.04a | |

| TMZh | >100 | >100 | >100 | |

| IC50 (µM) | ||

| treatment | PLB/ABCG2 | PLB-985 |

| MX | 0.20±0.17 | 0.004±0.001 |

| MX + Ko143 | 0.006±0.002 | 0.004±0.001 |

| MX + PU-9 | 0.006±0.003 | 0.005±0.003 |

| MX + MU-9 | 0.005±0,003 | 0.002±0.0004 |

| MX + CU-9 | 0.14±0.1 | 0.003±0.0001 |

| IC50 (µM) | ||

| treatment | A2780/Adr | A2780 |

| DOXO | 4.57±3.0 | 0.01±0.003 |

| DOXO+Ver | 0.58±0.1 | 0.01±0.007 |

| DOXO + PU-9 | 0.95±0.3 | 0.01±0.003 |

| DOXO + MU-9 | 1.56±0.4 | 0.02±0.01 |

| DOXO + PT-9 | 1.9±1 | 0.02±0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).