1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Jubail Industrial City

Situated on the extreme east coast of Saudi Arabia, Jubail Industrial City is considered the largest and one of the most important industrial cities in Middle East. Jubail was developed during the 1970s in line with the Kingdom's plans to move beyond oil dependency and encourage industrialization [

1]. The city’s location near the head of the Arabian Gulf makes it an important conduit for international shipping routes and trade.

The development was led by the Royal Commission for Jubail and Yanbu to build a world-class industrial center [

2]. Jubail is one of the most populous cities today, housing many petrochemical companies, manufacturing, and heavy industries vital to Saudi Arabia's economy and employment. Despite its industrial base, the planning of the city includes modern infrastructure, residential areas, and recreational facilities all designed to ensure a liveable urban environment [

3,

4,

5]. But rapid industrialization has come with challenges, environmental concerns, housing affordability and social equity issues among them. Tackling these intricacies remains essential for improving urban liveability and for enabling sustainable development within this industrial landscape [

6].

1.2. Study Urban Liveability in the Industrial Context

There are several reasons that studying urban liveability in industrial contexts, such as the city of Jubail, is important:

The Challenge of Balancing Economic Development with Quality of Life: Industrial cities are often focused on economic development with the downside of sacrificing their residents' quality of life. Despite the fact that inhabitants are not at risk of significant health problems as evident by Alzahrani et al. [

7]. Knowing what liveability means can help flag to balance growth with community needs.

Tackling Environmental Issues: Industrial processes can threaten the natural environment, affecting air and water quality and human health. Several reasons contribute to this, including the country's makeup and the sensitivity of its resources [

8,

9,

10]. Research and policies related to liveability allow scholars and decision-makers to respond to these issues and advocate for sustainability.

Social equity: The rapid pace of industrialization can deepen social inequity, resulting in a lack of access to housing, services and opportunities. This, in turn, allows a deeper understanding of such issues and the establishment of approaches that help further social equity.

Contributing to Policy Making: Liveability studies give needed information for city designers and policymakers. Effective policies to enhance liveability. Understand resident needs and perceptions.

Building Resilience within the Community: Economic depressions and industries are always on the verge of being affected and this may impact the people as well [

8,

11]. The study of liveability helps to create resilient communities, able to bend and not break, able to thrive to the best of their ability amongst industrial pressures.

Urban Liveability Research Promotes Sustainable Development: Following the emerging concept of industrial ecology, a focus on urban liveability can strengthen the integration of sustainable development into industrial planning through considering the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Along with smart city assessments six dimensions [

12,

13], more quantitative studies are needed to clarify the interconnections.

Moreover, this study can also inspire future research in liveability in industrial context. This could help with learning lessons in preparing plans for the same industrial setting elsewhere around the globe.

This can create environments that are economically productive, socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable, therefore contributes to high quality life of all residents, focusing on urban liveability in industrial contexts.

1.3. Objectives of the Paper

The main aims of this paper are as follows:

Understand Liveability Dynamics: Explore the dimensions of liveability in Jubail, focusing on housing affordability, environmental sustainability, and social equity.

Identify Challenges: Clarify the top challenges that residents are experiencing due to the rapid industrialization, such as issues with public health and infrastructure.

Collect Empirical Evidence: Employ mixed-methods research to capture residents’ perceptions of liveability through surveys and open-ended questions.

Check Initiatives to improve liveability (public space redevelopment, community engagement, etc.)

Policy Recommendations: Suggest ways that policymakers can work to build sustainable cities.

Share lessons for other industrial cities: (align findings with the LIVABLE CITIES initiative).

These aims are geared towards promoting a comprehensive understanding of liveability within industrial environments and promoting sustainable development for residents.

Theoretical Framework

1.4. What is Urban Liveability?

Urban liveability is the measure of the quality of life of an individual or community in a developed environment [

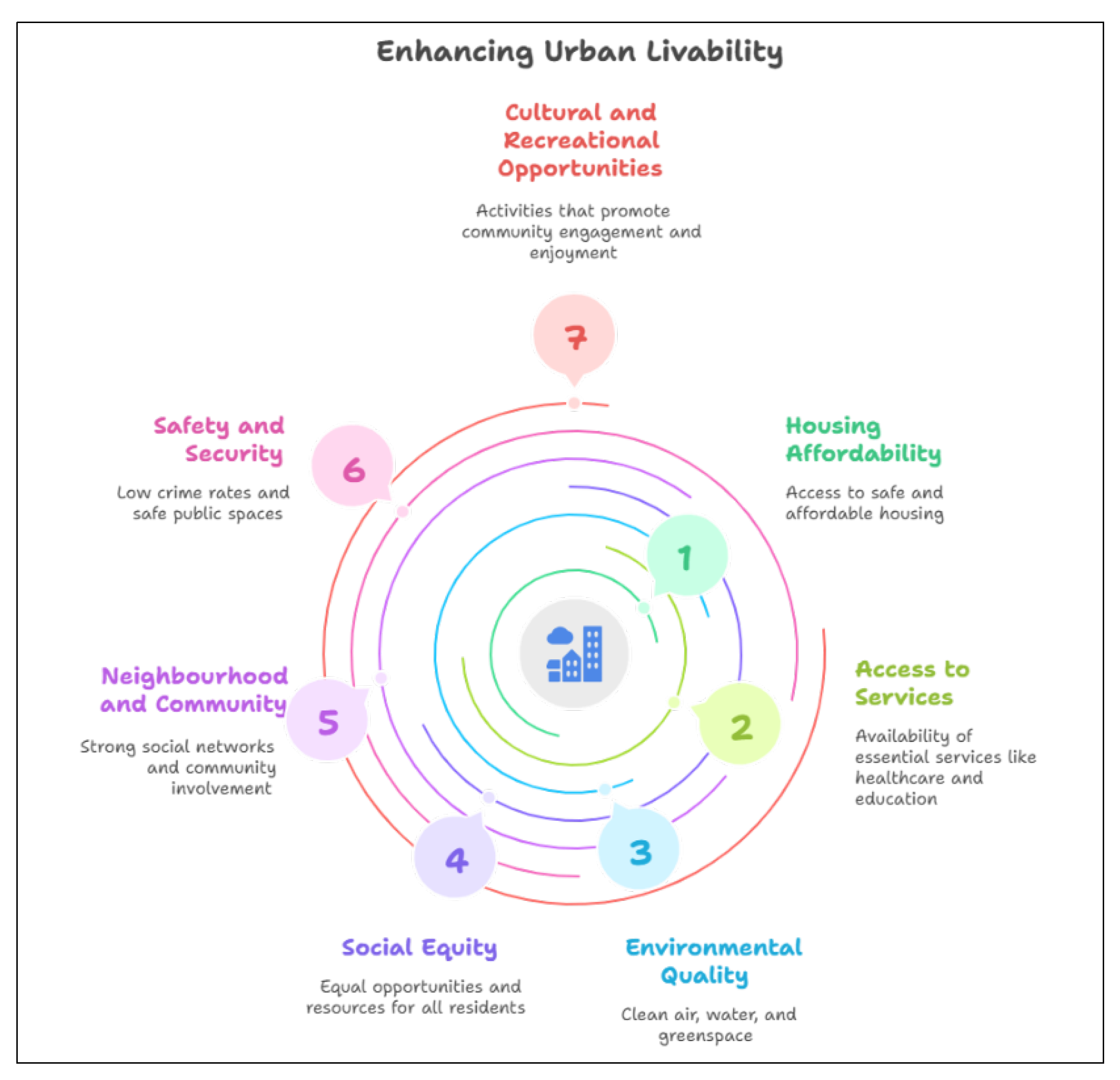

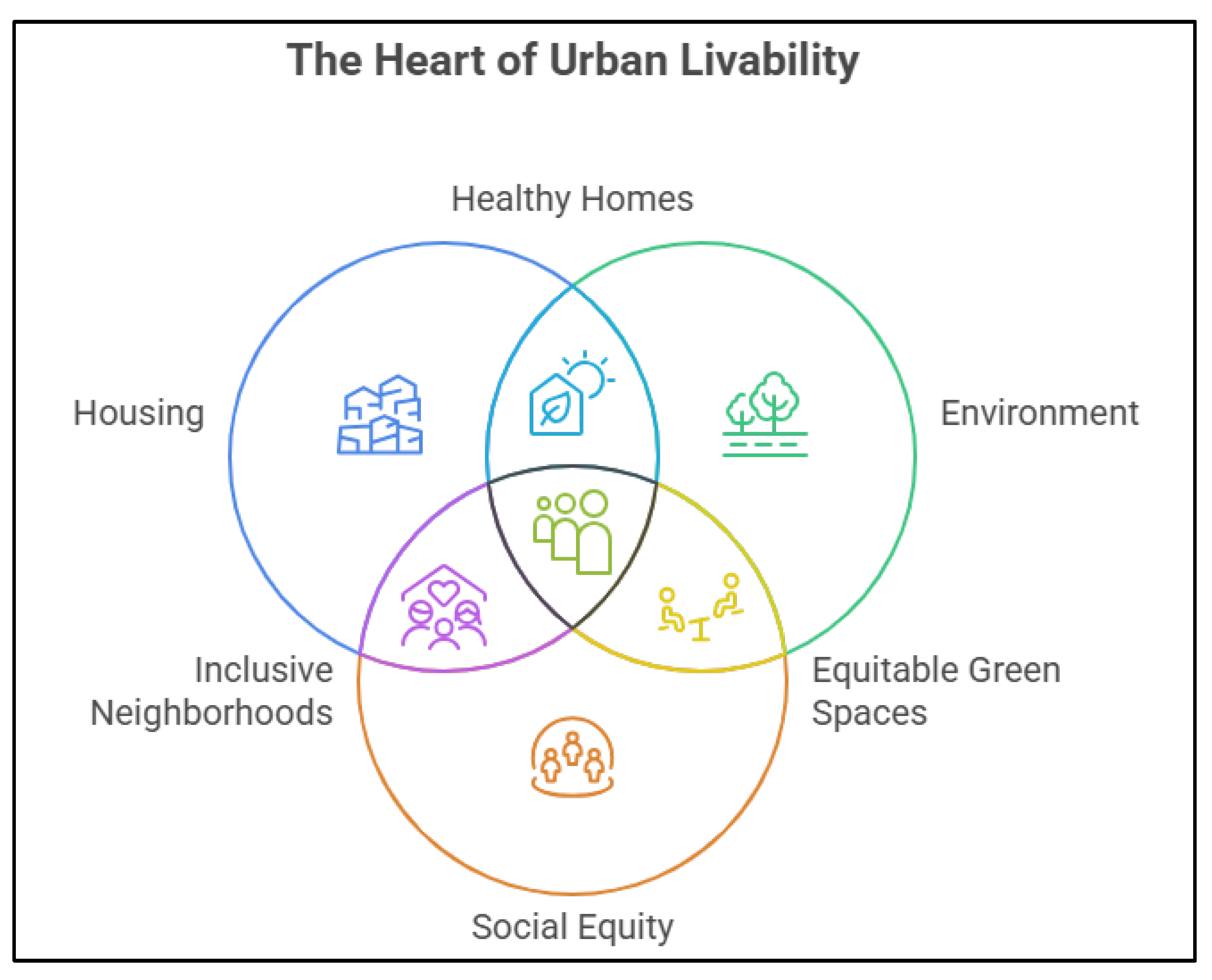

14]. It includes several elements shown in

Figure 1 that affect the residents by, for example, contributing to their general well-being and satisfaction with their home environment. Key dimensions include:

Housing Affordability: Access to safe, affordable and adequate housing is fundamental to liveability, taking into account space, quality and cost relative to income [

15].

Access to Services: The availability of essential services like healthcare, education, transport facilities and recreational locations play an important role. Cities that are liveable ensure that residents are able to access such services easily [

16,

17].

Environmental Quality: Clean air, water and greenspace are key components of health and well-being; hence, a healthy environment is essential to ensure health both physically and mentally [

18].

Social Equity: An equitable city prioritizes inclusion and is designed to offer all of its residents’ equal opportunities and resources [

19,

20].

Neighbourhood and Community: Good social networks and other community involvement increase Liveability, creating a sense of belonging and ownership [

21,

22].

The safety and security of an area can be another important factor in whether a resident feels secure; crime rates along with the safety of public spaces can contribute to better overall quality of life [

23,

24,

25].

Cultural and Recreational Opportunities: Availability of cultural and recreational activities that promote community engagement and enjoyment [

26,

27].

Figure 1.

Urban liveability elements.

Figure 1.

Urban liveability elements.

Overall, urban liveability is a mixture of these factors, which further reveals the interdependence of urban planning and policies aimed at improving the well-being of residents.

1.5. Dimensions of Liveability:

Urban Liveability is multidimensional as it comprises several dimensions which interplay to determine holistic Liveability in a city. Of these, housing, environment, and social equity, shown in

Figure 2, are especially key [

28,

29,

30].

1.5.1. Housing:

Affordability: Housing costs need to be reasonable compared to residents’ incomes.

Quality: Housing must be of reasonable human, health and safety standards; adequate space and utility [

31].

Diversity: A mix of housing types supports a mixed-income community [

32].

Location: Proximity/Access to jobs and critical services.

1.5.2. Environment:

Air and Water Quality: Air quality and safe drinking water are prerequisites for public health [

30].

More specific green spaces: Access to parks and recreational areas provides opportunities for socializing and exposure to nature [

5,

33].

Urban development should promote sustainability. Every good urban planning must consider climate resilience [

34,

35].

1.5.3. Social Equity:

Equity through Access to Services: Ensuring access to necessary services [

36].

Community Engagement: Involve the community in the decision-making process [

37].

Helping to address inequalities: Promoting the importance of diversity.

Inclusive Cultural Identity: When varied cultural traditions are honored, social bonds are created.

Housing, environment, and social equity can therefore serve as fundamental elements of Liveability that can influence the experience of the city. To create vibrant, inclusive and sustainable cities, it is important to look at these aspects in a holistic way.

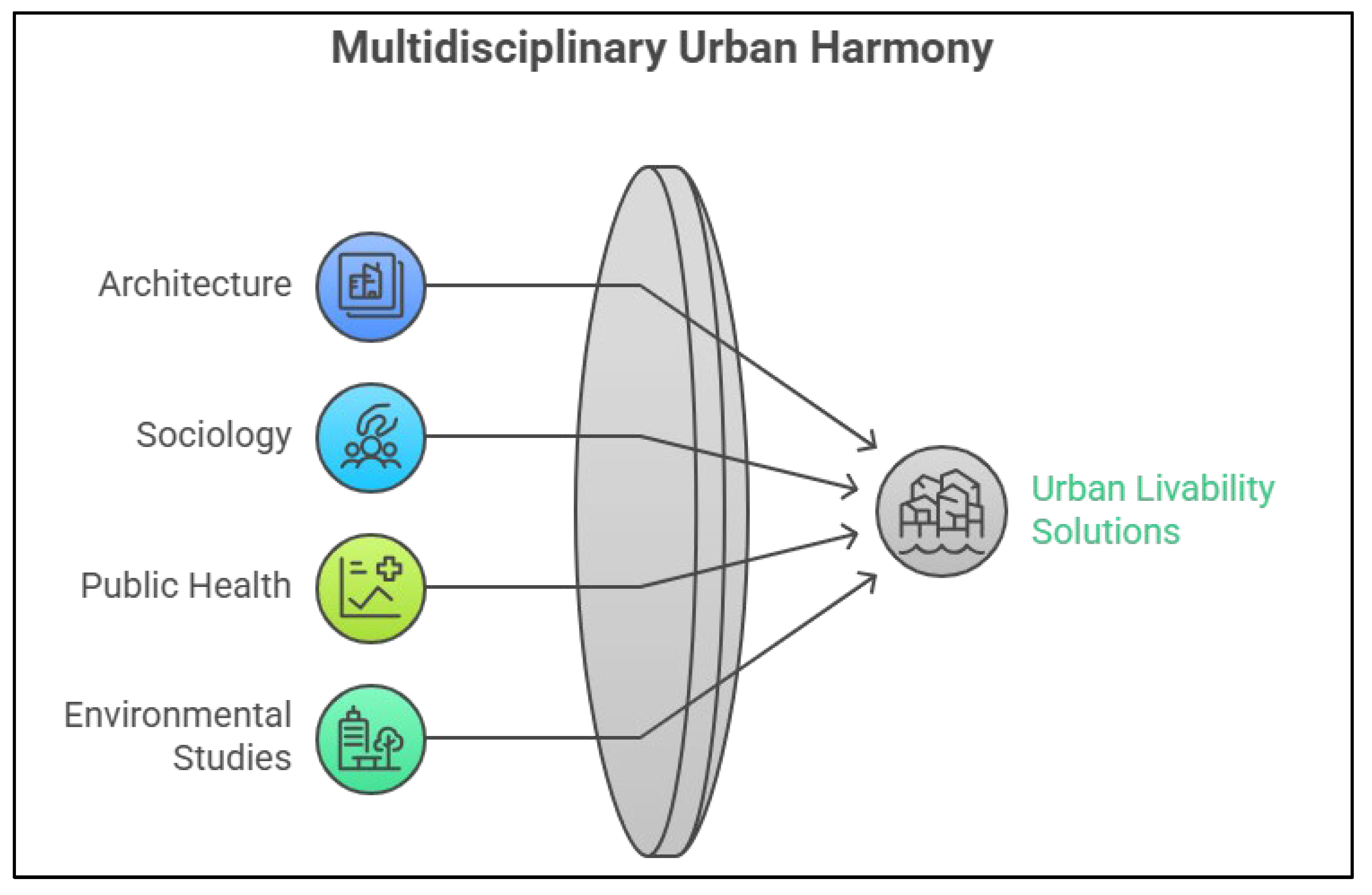

1.6. Interdisciplinary: Architecture, Sociology, Public Health, and Environmental Studies

The multidisciplinary approach shown in

Figure 3, including architecture, sociology, public health, and environmental studies, is crucial for creating urban Liveability solutions. The knowledge in each discipline is distinct and specific.

1.6.1. Architecture:

Architects establish spaces that are both functional and well designed for the benefit of community. The use of sustainable materials and energy-efficient designs help in promoting health and saving the environment [

38,

39]. The city planning is also essential and is to harmonize residential, commercial and recreational spaces.

1.6.2. Sociology:

Identifying Needs of Community Groups: Sociologists examine the needs and priorities of community groups.

Social Cohesion: Studies investigate how urban settings shape social engagement [

40].

Equity and Justice: Sociological research enlightens policies advancing equity.

1.6.3. Public Health:

Health Impact Assessments: Assessing health outcomes as they relate to urban design is critical.

Advocacy for Health Equity: Public health advocates work toward systemic changes that promote health equity [

41].

Environmental Health: It is important to know how environmental factors can affect health.

1.6.4. Environmental Studies:

Infrastructure: Pushing for minimal ecological impact in urban development.

Climate Resilience(s): Strategies such as green infrastructure to address climate challenges are critical [

42].

It is all about the Resource Management Process: The effective management of resources for a company to be sustainable.

In conclusion, a multi-faceted approach to a studied urban Liveability is integral to creating well-rounded spaces for diverse communities.

2. Materials and Methods

In the study, a mixed methods approach was used to explore Liveability in Jubail in detail. First, a review of literature summarizes what is known of urban Liveability and its dimensions. In addition, quantitative data from surveys sent to residents and collected to assess their perceptions and experiences with housing, environmental quality, and community engagement. Moreover, the qualitative data collected through open-ended questions give a rich understanding of individual experiences and perspectives. Data Collection techniques such as survey have a standard format with structured questionnaires and semi-structured format is used for open ended questions ensuring diversity and robustness of the data collected. Quantitative and qualitative data are crucial to this analytical framework as they allow for an integrated analysis of the Liveability determinants of Jubail.

3. Results

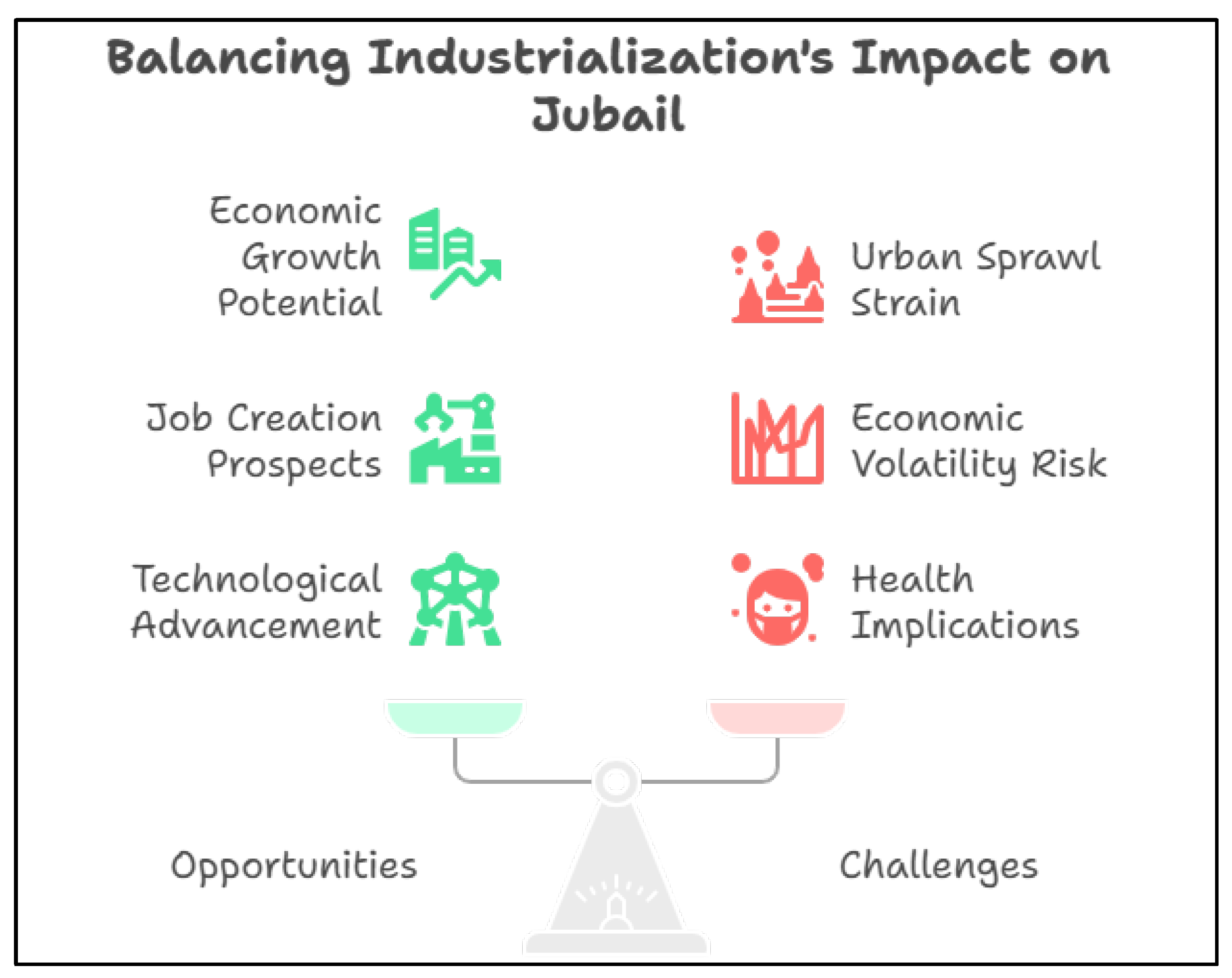

Despite falling within the world’s largest industrial area in Jubail Industrial City, the city of Jubail is beset by numerous urban Liveability challenges and opportunities shown in

Figure 4. These topics comprise housing affordability, environmental sustainability, social equity and the impact that remake of the industrial revolution.

3.1. Current Challenges in Jubail

3.1.1. Housing Affordability

As of the 2025, Jubail Industrial City in Saudi Arabia population is estimated at 711.800 people [

43]. There are a variety of factors that can influence this number, including the economy and migration patterns.

Housing affordability is a major concern in Jubail, influenced by multiple factors:

Increased Demand for property: During the construction phase workers came in from all over to work on the buildings resulting in demand for housing which the market could not keep up with resulting in the skyrocketing of property prices and rental costs.

Few housing options: Affordable housing for low- and middle-income families is still limited, causing many to look for substandard housing in near places such as Jubail town.

Economic Disparities: Higher incomes are not evenly distributed across cities, while the cost of housing continues to rise, resulting in an affordability crisis for lower income workers.

3.1.2. Impact on Environment Sustainability

Environmental sustainability is a second significant challenge for Jubail:

Pollution: Air and water pollution from industrial activities can be a concern for residents' health.

Resource Management: Water and energy are intensive resources and need to be effectively managed; otherwise, shortages would create a business continuity issue.

Green Spaces: The emphasis on industrial development frequently results in the loss of green areas, restricting recreational possibilities for the population.

3.1.3. Social Equity and Inclusion

Social equity and inclusion are essential for creating a unified community:

Inequitable Access to Services: Limited access to healthcare, education, and public transportation may exclude low-income residents from full participation in urban life.

The population is diverse, and there must be strategies to ensure inclusion and cohesion.

Lack of access to Decision Making Processes: Limited opportunities for participation in decision-making processes can lead to disenfranchisement.

3.1.4. Impacts of Rapid Industrialization

Jubail’s swift industrialization arguably offers both opportunities and challenges:

Urban Sprawl Industrial facilities usually require large areas of land, leading to urban sprawl which causes strain on existing infrastructure and services.

Economic volatility: With industrial sector dependence, local economy faces vulnerability considering global market changes.

Health Implications: Higher rates of respiratory diseases and other pollution-related health problems could increase long-term public health costs.

Figure 4.

Current challenges and opportunities in Jubail.

Figure 4.

Current challenges and opportunities in Jubail.

3.2. What Residents Say About Liveability

To identify strengths and weaknesses in Liveability, it is necessary to understand the residents' point of view on Liveability in Jubail. This portion details the survey results, housing conditions, services access, and qualitative relationships identified through open-ended questions.

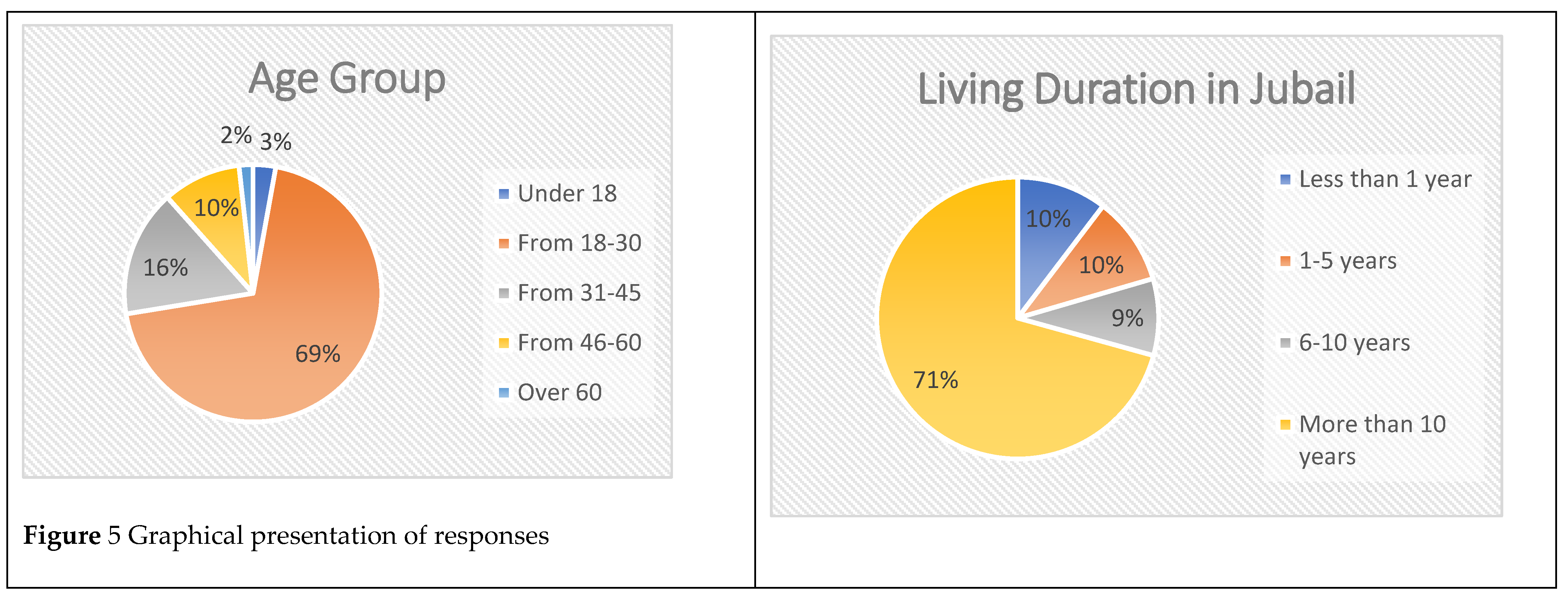

3.2.1. Opinion Survey on Perceptions of Liveability

The survey conducted among residents of Jubail with 457 respondents, the demographic results in

Figure 5 shows the age group and the duration they live in Jubail. The results revealed a mixed but positive picture of Liveability. Many residents enjoy economic options but have mixed feelings about the quality of their lives, with pollution and housing costs at the top of their concerns. The survey results revealed a satisfaction mean of 4.13 out of 5. This high satisfaction rate indicates that the quality-of-life level is promising and fulfils residents’ needs in different respects.

Housing affordability, air pollution and access to parks can be common issues. The mean of rating the air quality decreased to be 3.21 out of 5. This neutral feedback indicates the concerns residents have when living in an industrial area. Despite having an average of 4.34 out of five when they evaluated the availability of green spaces (parks, gardens) in their areas.

Community Engagement: Residents want to be more engaged in community decision-making processes. They are also neutral with 3.07 out of 5 rating to their involvement and opportunities to participate in community decision-making.

3.2.2. Analysis of Housing Conditions and Access to Services

The analysis identifies key challenges:

High numbers of overcrowded households, housing quality, and affordability concerns persist. Access to critical services is highly reliant on where someone lives, and in some neighborhoods, it can degrade a person’s quality of life. Residents show a satisfaction rate of 4.02 out of 5 with the availability of essential services (healthcare, education, transportation).

Table 1.

Means of responses.

Table 1.

Means of responses.

| Area Evaluated |

Satisfaction Mean |

| How satisfied are you with your overall quality of life in Jubail? |

4.13 |

| How would you describe the level of safety in your area? |

4.70 |

| How do you rate the air quality in Jubail? |

3.21 |

| Do you feel you have opportunities to participate in community decision-making? |

3.07 |

| How satisfied are you with the availability of essential services (healthcare, education, transportation) in your area? |

4.02 |

| How do you rate the availability of green spaces (parks, gardens) in your area? |

4.34 |

| How would you rate your social interaction with your neighbor? |

3.18 |

| How much does the surrounding environment affect your mental wellbeing? |

3.74 |

3.2.3. Qualitative insights from open-ended questions.

The open-ended questions provided a deeper look:

Residents referenced challenges like how long commutes worked and where to find affordable housing. Especially when they live in Jubail town. Additionally, several respondents cited community support networks and cultural diversity as positive features of living in Jubail. Moreover, respondents expressed a strong desire for environmental improvements and greater government transparency.

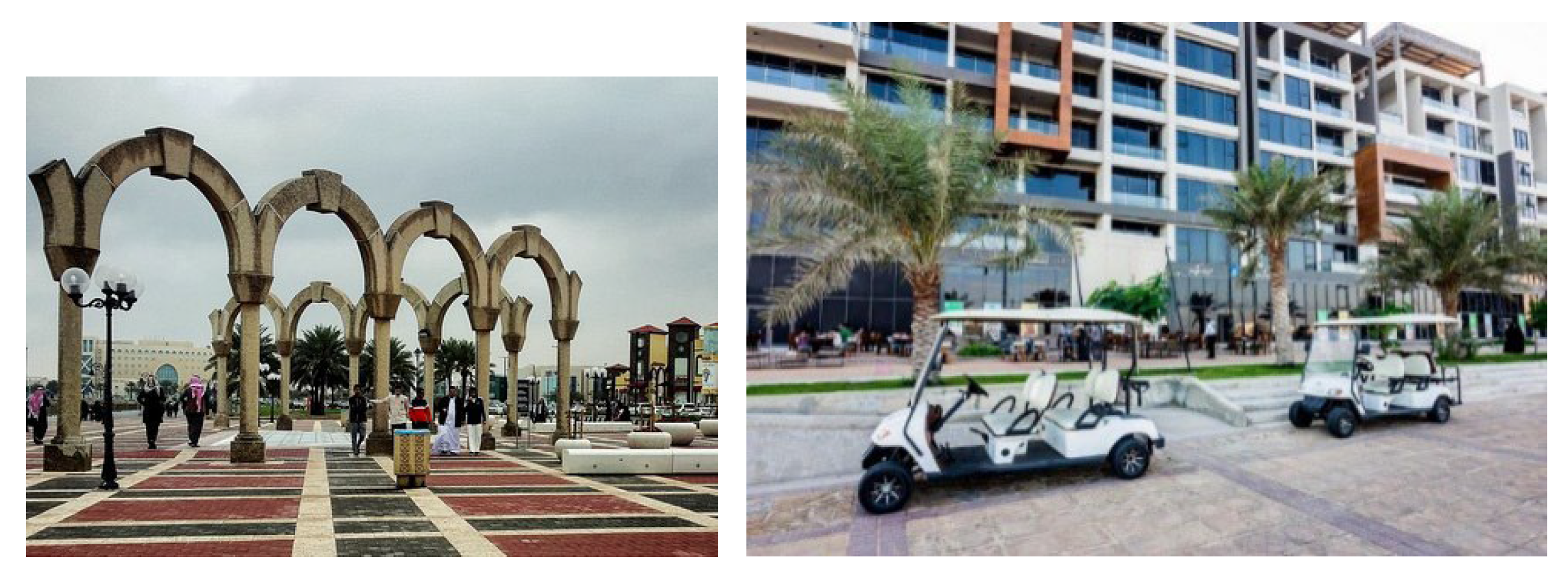

The city center, which has changed dramatically over the past few years, was evaluated with a sense of satisfaction. Recently, there have been a lot of entertainment facilities opened shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, such as coffee shops, malls, and shops. Consequently, people were able to interact more effectively, and services were of higher quality.

4. Discussion

In Jubail, many projects have provided inspiration in challenges, prioritization, and engagement in public space redevelopment and liveability. Redevelopment of public space seeks to re-create areas with low congregation traffic into bustling areas full of people. Parks development and renovation initiatives give residents space for leisure and social interaction. This took place in having Alfanteer area renovated into a public community space to accommodate residents’ needs and aspirations as shown in the

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 below.

Community centers bring cultural activities and recreational activities, helping people to belong. While emphasizing walkability and access encourage walking and biking like Dareen area.

Figure 8.

Alfanteer and Dareen Areas.

Figure 8.

Alfanteer and Dareen Areas.

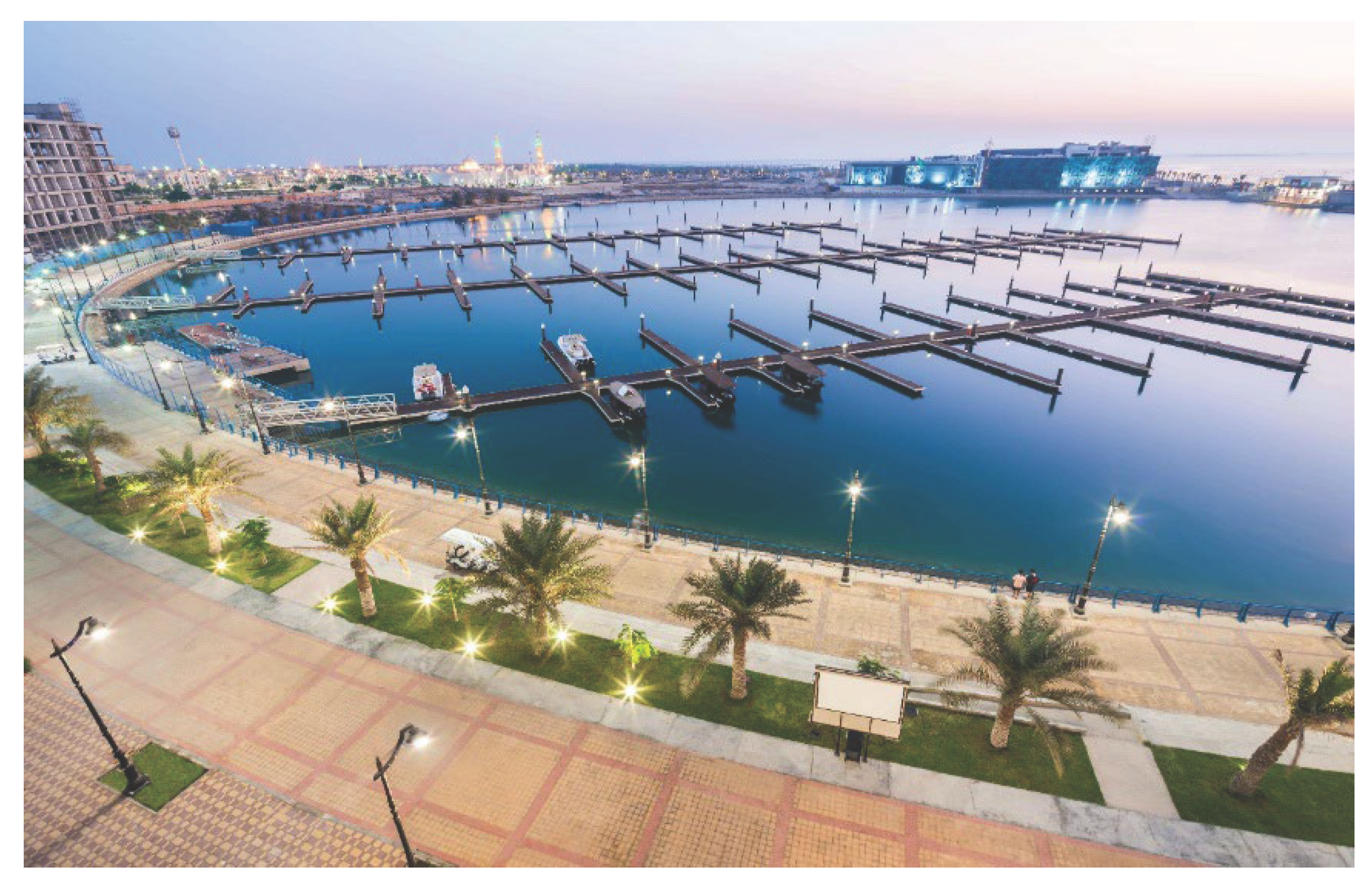

Figure 9.

Jubail beach and recreational activities.

Figure 9.

Jubail beach and recreational activities.

Community engagement programs aim to engage residents in decision making. Initiatives enable residents to be part of urban planning dialogues, guaranteeing diverse voices are considered. Programs support community service projects that improve local environments and build relationships. In addition to cultural festivals that demonstrate cultural diversity and help in building social inclusion.

The survey shows improved satisfaction with living conditions and community relationships. Parks and community centers with higher foot traffic indicate more socialization. Engagement programs help cultivate stronger sense of belonging amongst residents. When it comes to the evidence, the correlation test between the satisfaction rate and the community engagement, p-value achieved 6.26 * 10-20 which indicates a very strong relationship between the rate of social interaction with neighbours and the rate of living satisfaction in general.

4.1. Environmental Analysis

Jubail is an industrial city, thus an environmental assessment of it, is of urgent and pivotal necessity in terms of the health effects of industrial activity on the people as well as sustainability.

4.1.1. Impact of Industrial Activities on Public Health

Rapid industrialization has important consequences.

Table 2 outlines residents' perceptions of the major challenges affecting quality of life in Jubail. The most frequently reported issues were housing affordability (62.5%) and air quality (58.7%), followed by limited access to services (36.5%) and overcrowding (27.2%). Despite this, only 12.7% of respondents reported a lack of green spaces as an existing issue.

These findings suggest that while environmental and infrastructural factors (e.g., housing and air quality) are of primary concern to residents, aspects related to green space availability are less frequently perceived as problematic. The distribution reveals a central tendency towards moderate satisfaction with air quality, highlighting a paradox typical of industrial cities—where infrastructural advancements coexist with environmental strain. This pattern underscores the need for continuous air monitoring and urban greening initiatives to sustain liveability in the city.

Industry between Environmental Pollution Vulnerable Populations: Children and the elderly are some vulnerable groups against pollutants in industrial pollution.

Health Tracking and Monitoring: Periodic health assessments are necessary to assess the immediate effects of industrialization.

Using qualitative coding of open-ended responses revealed recurring themes. The most anticipated changes included improvements in transportation, expansion of green spaces, and initiatives to reduce pollution. These themes highlight residents’ priorities for enhancing quality of life in Jubail.

4.1.2. Analysis of air and water quality data

There are important insights to be gathered from analyzing air and water quality data and using spearman correlations shown in

Table 3:

Air Quality Monitoring Report: Fluctuations in air quality are often tied to changes in industrial output which is detrimental to human health with the highest influential factor.

Assessment of services, ongoing monitoring is needed to ensure levels are satisfactory.

Foster Public Awareness Air and water quality data must be transparent and made available to residents so they can take steps to protect themselves.

Table 3.

Correlation of quality of life with different factors.

Table 3.

Correlation of quality of life with different factors.

| Area Evaluated |

|

How would you describe the level of safety in your area?

(Safety) |

How do you rate the air quality in Jubail?

(Air Quality) |

Do you feel you have opportunities to participate in community decision-making?

(Community Participation) |

How satisfied are you with the availability of essential services (healthcare, education, transportation) in your area?

(Services) |

| How satisfied are you with your overall quality of life in Jubail? |

Correlation Coefficient |

.352**

|

.459**

|

.330**

|

.514**

|

| |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.000

(8.71E-15) |

0.000

(3.48E-25) |

0.000

(4.26E-13) |

0.000

(3.94E-32) |

| |

N |

457 |

457 |

457 |

457 |

4.1.3. Sustainability Implications

Environmental challenges have wide-reaching implications for sustainability:

Resource Management: Unsustainable practices can lead to depletion of natural resources, making management necessary. However, the construction and operation of industrial plants cause changes in the natural state of the environment, emitting greenhouse gases, and even adding to the climate crisis which calls for mitigation strategies in urban planning.

SDGs: Aligning industrial practices with SDGs fosters a balanced approach to economic growth and environmental protection.

5. Conclusions

Findings from the study reveal a complex balance between satisfaction with urban systems and persistent environmental and social concerns. Most residents reported a relatively positive quality of life, particularly in relation to safety and access to essential services. However, perceptions of air quality and housing affordability emerged as significant challenges, with over half of respondents identifying them as existing issues. In contrast, issues such as overcrowding and lack of green spaces were reported less frequently, suggesting localized but significant spatial inequalities in liveability. These patterns illustrate the paradox of Jubail’s urban model: a city that achieves high standards of infrastructure and safety while grappling with the ecological pressures of industrial development. The results demonstrate how perceptions of liveability are shaped not only by physical amenities, but also by environmental quality and affordability dimensions that require cross-disciplinary collaboration to sustain well-being in industrial cities.

The need of the hour is for the policymakers to start implementing practical solutions towards the environmental adversities to make Jubail a more livable place.

Regulatory Frameworks: More stringent environmental regulations on industrial emissions should be a priority.

Health Impact Assessments: Notifying and/or requiring health assessments for new industrial projects can reveal potential threats to public health.

Green Infrastructure: Sustainable practices lead to reduced environmental footprints and improved resource conservation.

How everyone can work towards a lower carbon footprint, such as reducing one’s private transportation emissions. Working for public transportation projects.

Community Engagement: Getting residents and businesses involved in decision-making builds trust and deepens relationships.

Education and Awareness Campaigns: Keeping residents informed about environmental problems can enable communities to become a part of the solution.

Housing Affordability Struggles: Increasing real estate prices and a shortage of affordable housing present major obstacles.

Environmental Development: Industrialization creates worries for air and water quality.

Social equity and inclusion –Policies ensuring access to services for all, as there are differences in access.

Community Initiatives: Redevelopment and engagement programs have improved residents' quality of life.

A systematic mapping of Liveability factors in Jubail as part of the study indicates. This study contributes to LIVABLE CITIES developing an extensive analysis of Liveability factors in Jubail. These findings can guide policymakers and urban planners in developing strategies to improve quality of life. With the responsiveness of housing, environmental, and social issues, Jubail can be a model for other industrial cities.

Future research agendas should include:

Longitudinal Studies: Exploring the long-term effects of industrialization on health and environmental quality.

Other Industrial Cities: Comparative Analyses

Community-Based Research: Involving residents as partners in participatory programs to inform community-responsive policymaking.

This study is a guiding star for a livable Jubail. Not only does this study inform the LIVABLE CITIES initiative, but it also lays the foundation for future research that can result in positive outcomes for cities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this research are available from the corresponding author and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- I. M. Al-But’hie and M. A. Eben Saleh, "Urban and industrial development planning as an approach for Saudi Arabia: the case study of Jubail and Yanbu," Habitat International, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1-20, 2002/01/01/ 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. Al-Hathloul and M. Aslam Mughal, "Creating identity in new communities: case studies from Saudi Arabia," Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 199-218, 1999/09/01/ 1999. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Aina, A. Wafer, F. Ahmed, and H. M. Alshuwaikhat, "Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia," Cities, vol. 90, pp. 272-281, 2019/07/01/ 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. S. ALRUWAILI, "Observing the Enablers for Achieving Sustainability in Saudi Oil Industry Cities According to Vision 2030 Aspirations: A Case Study of Jubail Industrial City," Emirates Journal for Engineering Research, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 4, 2025, https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/ejer/vol30/iss1/4/.

- R. M. Alshehri et al., "Impact of Urban Green Spaces on Social Interaction Among People in Neighborhoods: Case Study for Jubail, Saudi Arabia," Sustainability, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Yassin, "Livable city: An approach to pedestrianization through tactical urbanism," Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 251-259, 2019/03/01/ 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Alzahrani, A. S. El-Sorogy, and S. Qaysi, "Assessment of human health risks of toxic elements in coastal area between Al-Khafji and Al-Jubail, Saudi Arabia," Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 196, p. 115622, 2023/11/01/ 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Aina, "Achieving smart sustainable cities with GeoICT support: The Saudi evolving smart cities," Cities, vol. 71, pp. 49-58, 2017/11/01/ 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Al-Shihri, "Impacts of large-scale residential projects on urban sustainability in Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia," Habitat International, vol. 56, pp. 201-211, 2016/08/01/ 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Altouma et al., "An environmental impact assessment of Saudi Arabia's vision 2030 for sustainable urban development: A policy perspective on greenhouse gas emissions," Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, vol. 21, p. 100323, 2024/02/01/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Karim Magdy Shafiq, "Liveable City Centre: Livability through The Lens of The Singaporean Experience (Case of Singapore City Center)," Engineering Research Journal, vol. 176, pp. 16 - 28 , publication_type = article, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C.-W. Chen, "Can smart cities bring happiness to promote sustainable development? Contexts and clues of subjective well-being and urban livability," Developments in the Built Environment, vol. 13, p. 100108, 2023/03/01/ 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, Y. Wang, K. Wu, X. Yue, and H. o. Zhang, "Livability-oriented urban built environment: What kind of built environment can increase the housing prices?," Journal of Urban Management, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 357-371, 2024/09/01/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Jodder, M. Z. Hossain, and J.-C. Thill, "Urban Livability in a Rapidly Urbanizing Mid-Size City: Lessons for Planning in the Global South," Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 1504, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Mehdipanah, "Without affordable, accessible, and adequate housing, health has No foundation," The Milbank Quarterly, vol. 101, no. Suppl 1, p. 419, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Edwards and A. D. Tsouros, Promoting physical activity and active living in urban environments: the role of local governments. WHO Regional Office Europe, 2006.

- E. Marchigiani, "Healthy and caring cities: accessibility for all and the role of urban spaces in re-activating capabilities," in Care and the City: Routledge, 2021, pp. 75-87.

- D. Efroymson, M. Rahman, and R. Shama, Making Cities More Liveable: Ideas and Action. HealthBridge, 2009.

- E. Harris, A. Franz, and S. O’Hara, "Promoting social equity and building resilience through value-inclusive design," Buildings, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 2081, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Meerow, P. Pajouhesh, and T. R. Miller, "Social equity in urban resilience planning," Local Environment, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 793-808, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K.-y. E. Lee and W.-w. V. Chan, "Inclusive Management and Neighborhood Empowerment," in Inclusive Housing Management and Community Wellbeing: A Case Study of Hong Kong: Springer, 2024, pp. 259-307.

- L. Mahmoudi Farahani, "The value of the sense of community and neighbouring," Housing, theory and society, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 357-376, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Beck, "Linking the quality of public spaces to quality of life," Journal of Place Management and Development, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 240-248, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Deniz, "Improving perceived safety for public health through sustainable development," Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 216, pp. 632-642, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Antolín-López, M. d. M. Martínez-Bravo, and J. A. Ramírez-Franco, "How to make our cities more livable? Longitudinal interactions among urban sustainability, business regulatory quality, and city livability," Cities, vol. 154, p. 105358, 2024/11/01/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Kurniawan, A. Srijaroon, and S. H. Mousavi, "Exploring the Benefits of Recreational Sports: Promoting Health, Wellness, and Community Engagement," Journal Evaluation in Education (JEE), vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 135-140, 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Stodolska, "Recreation for all: Providing leisure and recreation services in multi-ethnic communities," World Leisure Journal, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 89-103, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. John, S. Turaev, S. Al-Dabet, and R. Abdulghafor, "Multidimensional Assessment of Public Space Quality: A Comprehensive Framework Across Urban Space Typologies," arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.21555, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Kashef, "Urban livability across disciplinary and professional boundaries," Frontiers of architectural research, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 239-253, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Martino, C. Girling, and Y. Lu, "Urban form and livability: socioeconomic and built environment indicators," Buildings & Cities, vol. 2, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Neuhuber and A. E. Schneider, "Stratification of Livability: A Framework for Analyzing Differences in Livability Across Income, Consumption, and Social Infrastructure," Social Indicators Research, vol. 177, no. 3, pp. 1051-1080, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Leby and A. H. Hashim, "Liveability dimensions and attributes: Their relative importance in the eyes of neighbourhood residents," Journal of construction in developing countries, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 67-91, 2010, doi: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46817848_Liveability_dimensions_and_attributes_Their_relative_importance_in_the_eyes_of_neighbourhood_residents.

- D. Zhan, M.-P. Kwan, W. Zhang, J. Fan, J. Yu, and Y. Dang, "Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China," Cities, vol. 79, pp. 92-101, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Ali, H. Niaz, S. Ahmad, and S. Khan, "Investigating how Rapid Urbanization Contributes to Climate Change and the Social Challenges Cities Face in Mitigating its Effects," Review of Applied Management and Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1-16, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Mitchell, S. Enemark, and P. Van der Molen, "Climate resilient urban development: Why responsible land governance is important," Land Use Policy, vol. 48, pp. 190-198, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Perikangas, A. Määttä, and S. Tuurnas, "Ensuring social equity through service integration design," Public Management Review, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 452-472, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Geekiyanage, T. Fernando, and K. Keraminiyage, "Assessing the state of the art in community engagement for participatory decision-making in disaster risk-sensitive urban development," International journal of disaster risk reduction, vol. 51, p. 101847, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Lehmann, "Sustainable building design and systems integration: combining energy efficiency with material efficiency," in Designing for Zero Waste: Routledge, 2013, pp. 209-246.

- A. K. M. Yahia and M. Shahjalal, "Sustainable materials selection in building design and construction," International journal of science and engineering, vol. 1, no. 4, p. 10.62304, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Qi, S. Mazumdar, and A. C. Vasconcelos, "Understanding the relationship between urban public space and social cohesion: A systematic review," International Journal of Community Well-Being, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 155-212, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Northridge and L. Freeman, "Urban planning and health equity," Journal of urban health, vol. 88, pp. 582-597, 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Pamukcu-Albers, F. Ugolini, D. La Rosa, S. R. Grădinaru, J. C. Azevedo, and J. Wu, "Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics," Landscape ecology, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 665-673, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. World Population, "Jubayl Population 2025," ed, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).