Introduction

Mexico, as a developing country, has begun to implement various sustainability practices in recent years. However, the scope of these initiatives has remained limited due to inefficient organization and a lack of comprehensive knowledge on the subject. A clear example of this is the management of solid waste: instead of using a system that separates waste by type, the country predominantly relies on a generalized model that sends mixed waste to conventional landfills, thus missing opportunities for recycling and composting (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, 2020).

In terms of renewable energy, some municipalities have distributed solar water heaters free of charge, but this practice is not as widespread as in other countries with similar systems. Moreover, technologies such as solar panels or rainwater harvesting systems require a significant financial investment that remains out of reach for most of the population. On the other hand, the development of urban gardens—although a promising solution for promoting food self-sufficiency and strengthening social cohesion—faces challenges due to a lack of community organization in many neighborhoods across the country.

Meanwhile, other nations are developing and implementing highly effective sustainability strategies in both architecture and urban planning. A prominent example is Vauban, Germany—known as “the city of the future”—which integrates a holistic approach to reducing environmental impact while improving residents’ quality of life (Barrio de Vauban: la ciudad del futuro está en Friburgo, n.d.).

This article aims to analyze such strategies and propose adaptations for already consolidated neighborhoods in Mexico, where limited access to sustainable solutions could be transformed into economic, social, and—above all—environmental benefits through the implementation of the eco-neighborhood model.

Analysis of a Comparable Case Study

As part of this study, a comparative analysis was conducted on several internationally recognized ecodistricts, including BedZED in London, San Antonio in Colombia (considered the only eco district in Latin America), and Vauban in Freiburg, Germany (Seis casos de éxito de ecobarrios sostenibles | Connections by Finsa, n.d.). Among these, Vauban stands out for its advanced organization and sustainable approach, making it a key reference for this analysis.

Vauban—known as “the city of the future”—is located in Freiburg, a city that has led urban sustainability efforts since the 1970s. This district combines innovative urban planning with a strong sense of community, prioritizing residents' quality of life through architectural, social, and environmental solutions.

One of Vauban’s most notable features is its transportation system, which promotes sustainable mobility through an efficient tram network, dedicated bicycle lanes, and extensive pedestrian zones. Motorized vehicles have restricted access to the neighborhood and must be parked in designated areas outside the residential core, significantly reducing pollution and improving air quality. In addition, the district includes over 600 hectares of green areas and 160 playgrounds—spaces that encourage community interaction and enhance residents’ well-being.

From an architectural perspective, Vauban is distinguished by its energy-efficient buildings. More than 100 structures generate more energy than they consume, while another 45 buildings meet the Passivhaus standards, designed to maximize solar orientation, natural ventilation, and thermal insulation. These practices not only reduce energy consumption but also lower long-term costs (Fastenrath & Braun, 2018).

In terms of resource management, the ecodistrict implements organic waste recycling systems and reuses greywater for garden irrigation. These measures, combined with green spaces and limited vehicular circulation, have contributed to the area’s outstanding air quality.

Freiburg’s history is a key factor in understanding Vauban’s success. Since the 1970s, social movements led by environmental and anti-nuclear activists have shaped the adoption of sustainable policies. These grassroots efforts eventually led to the creation of local energy regulations that exceeded national standards.

On one hand, citizen initiatives and experimentation in small-scale projects were crucial in the early stages; on the other, political will and municipal policies ensured the institutionalization of these practices. This interaction between local actors and authorities illustrates how urban sustainability transitions require a co-evolution of social, economic, and institutional actions (Fastenrath & Braun, 2018).

As a comparable model, Vauban offers valuable lessons for adapting the ecodistrict approach in Mexico. Its success demonstrates the importance of community organization, participatory design, and political commitment in overcoming social and economic barriers—elements that could be replicated in existing neighborhoods within the Mexican context.

To explore the feasibility of adapting the ecodistrict model in Mexico, a follow-up case study was carried out in the state of Querétaro. This location was selected due to its rapid urban growth, increasing environmental challenges, and the presence of active civil society initiatives focused on sustainability. As part of this analysis, a survey was designed to assess public awareness, attitudes, and willingness to adopt sustainable practices at the household level. The findings would serve to inform context-sensitive strategies that reflect both the limitations and opportunities of Mexican urban environments.

Surveys

A survey was conducted via Google Forms, designed with a series of closed-ended questions and a final open-ended question to gather additional comments. The survey was completed by 63 residents of Mexico and aimed to identify both the environmental practices currently being implemented in the country and those that participants consider feasible to adopt in their own homes.

The majority of respondents were young people, with 72% falling within the 18 to 29 age range. This demographic provided a broader perspective on current environmental practices and helped shape recommendations aligned with the preferences and needs of younger populations, thereby encouraging greater acceptance and practical application.

Figure 1.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 1.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 2.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 2.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 3.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 3.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 4.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 4.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 5.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 5.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

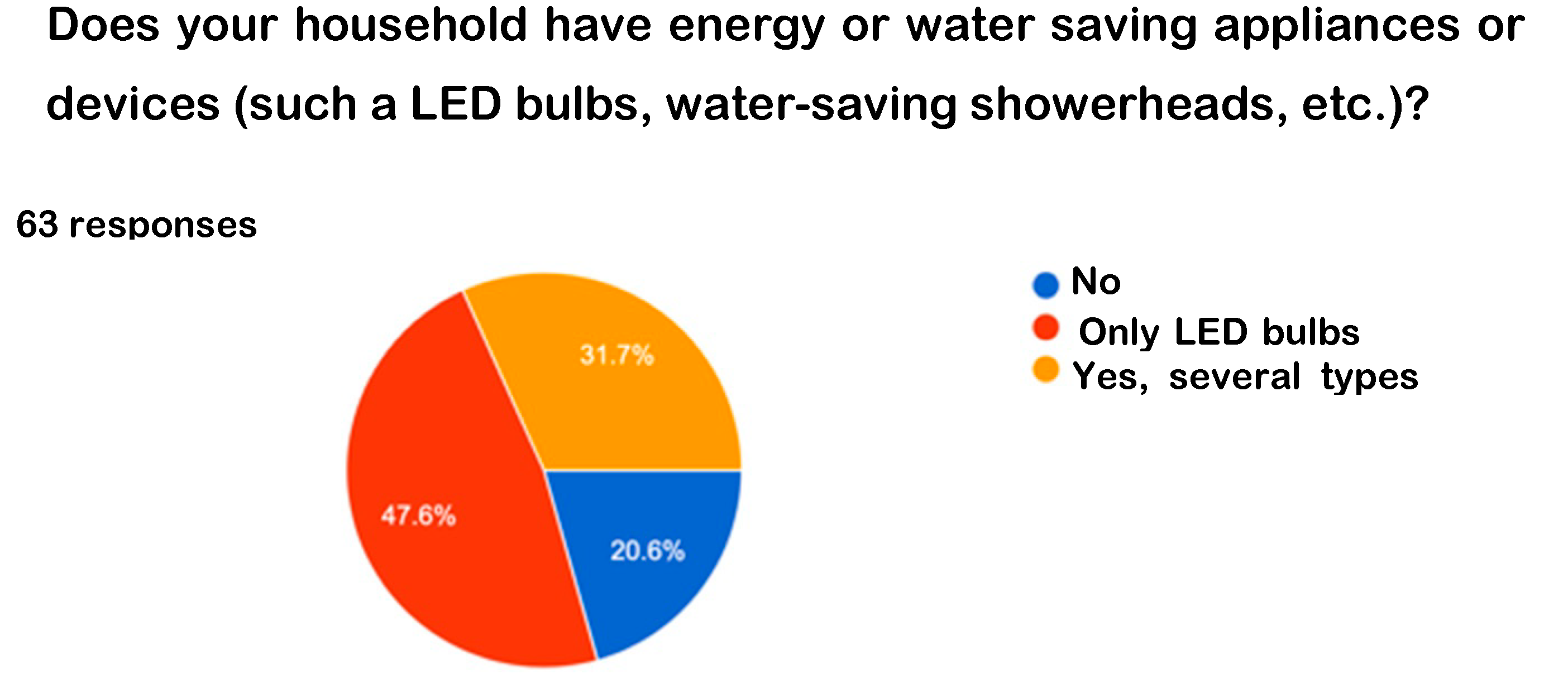

Figure 6.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 6.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

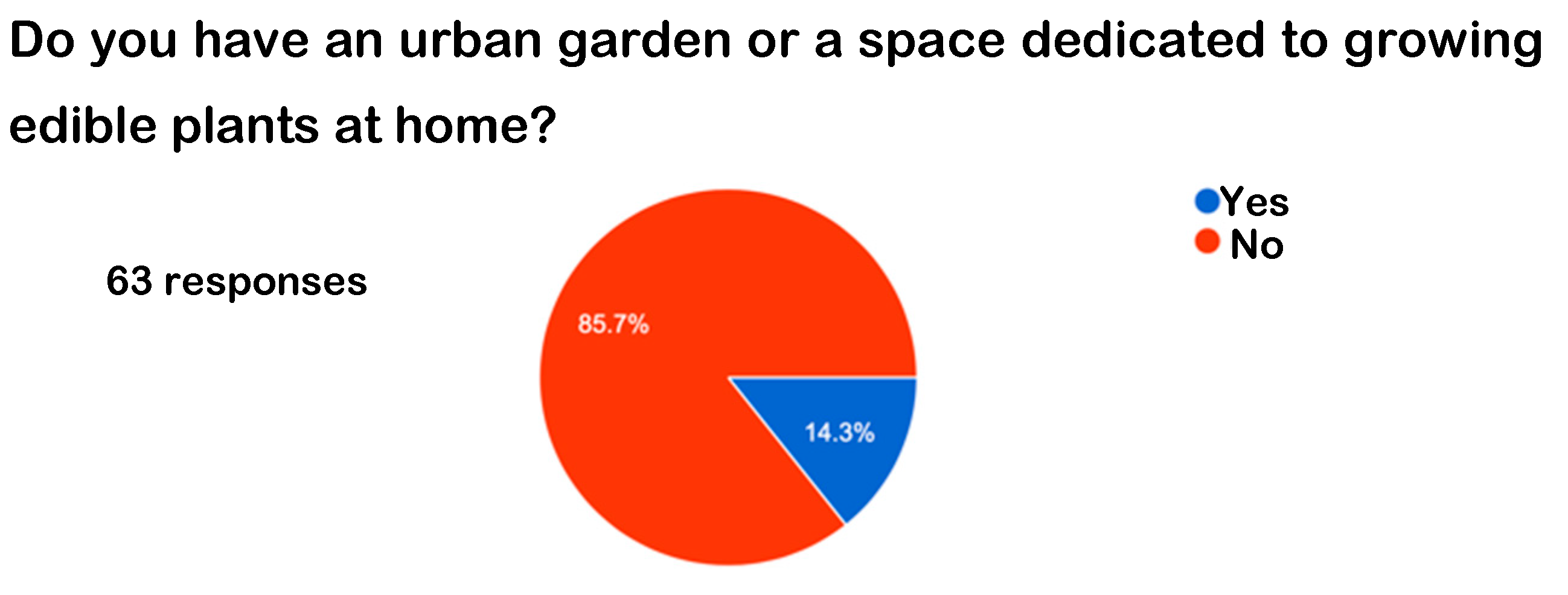

Figure 7.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 7.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

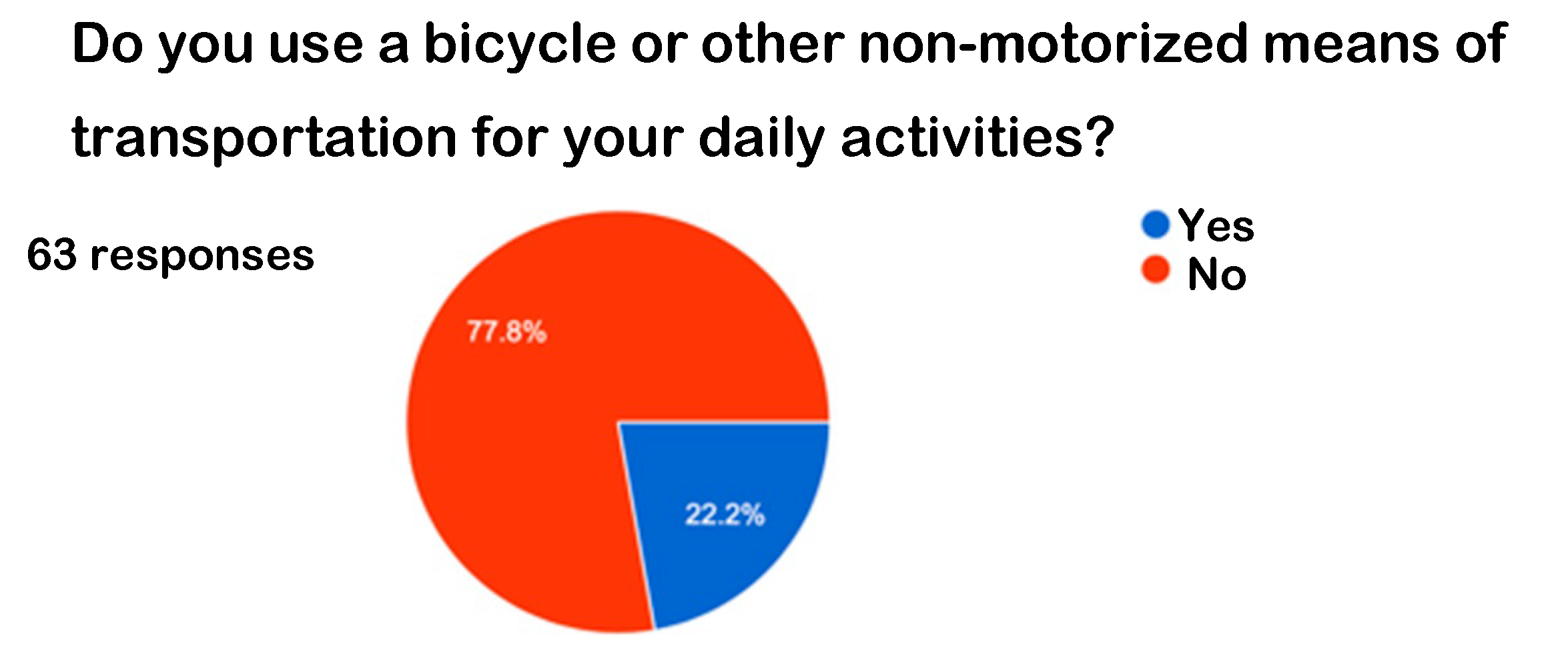

Figure 8.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 8.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

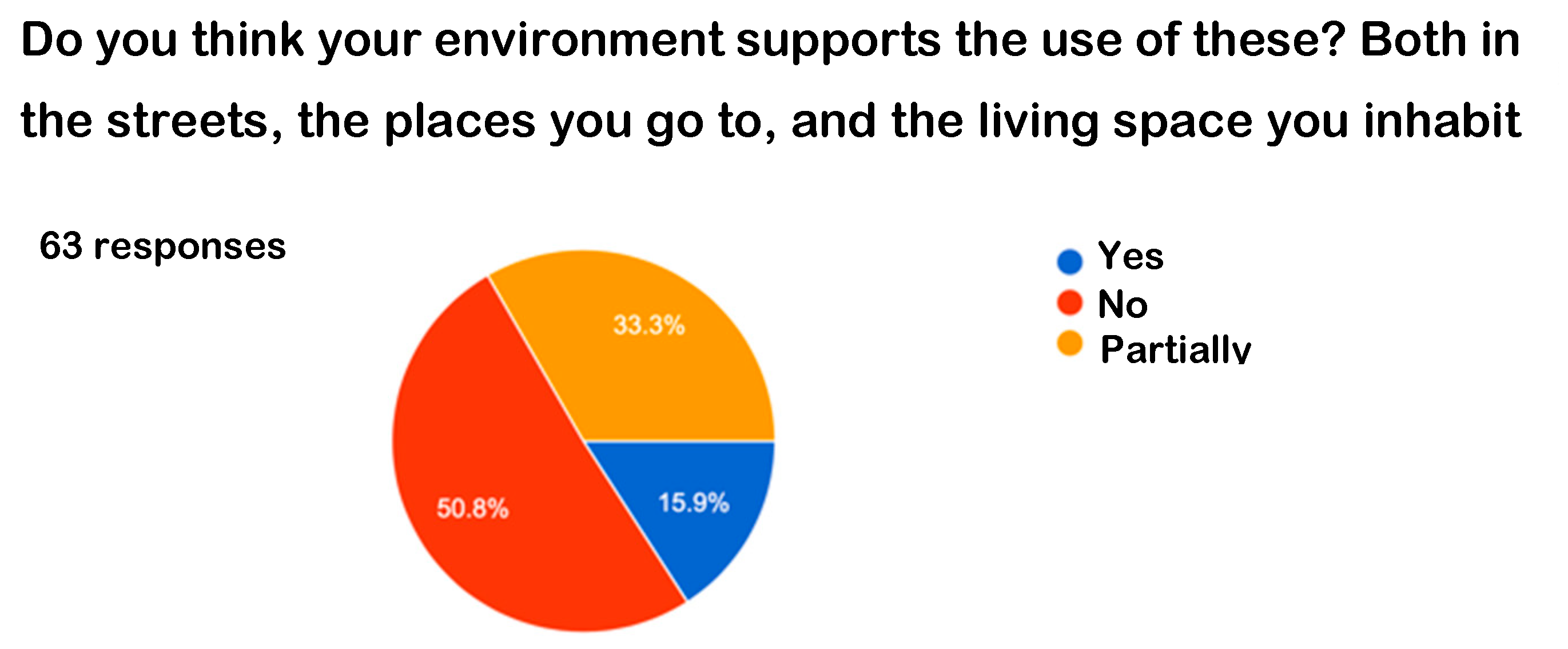

Figure 9.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024) (López, 2024).

Figure 9.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024) (López, 2024).

Figure 10.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 10.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 11.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 11.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 12.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 12.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 13.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 13.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 14.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

Figure 14.

Own elaboration based on the results of a survey conducted via Google Forms (López, 2024).

The following section presents the survey results, beginning with those that offer a current assessment of housing conditions.

The following charts present the data from the interviews conducted, specifically focusing on the section that explores participants’ willingness to implement sustainable strategies in their homes.

Survey Analysis and Comparison with the Vauban Case Study and Mexican Neighborhoods

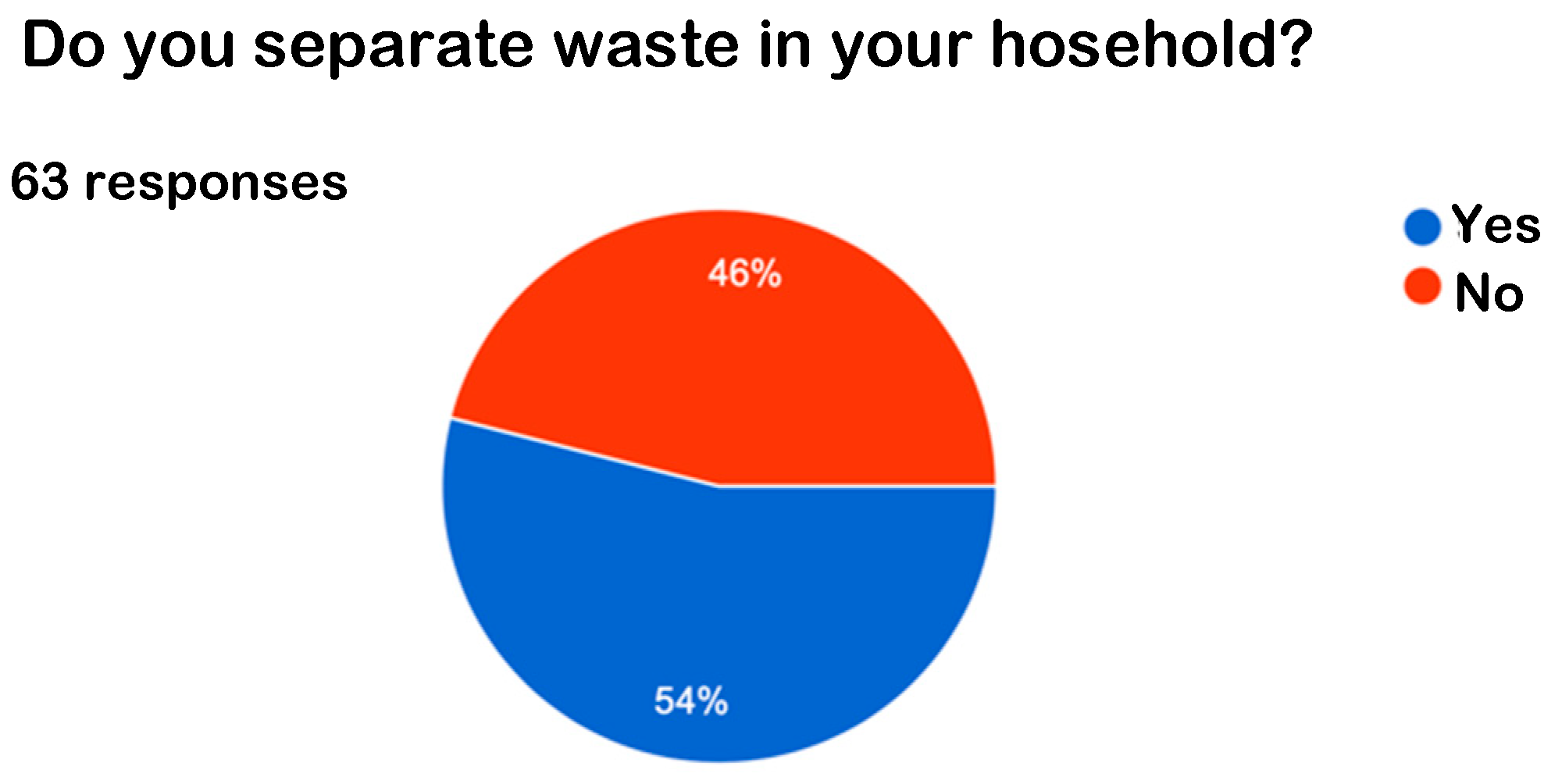

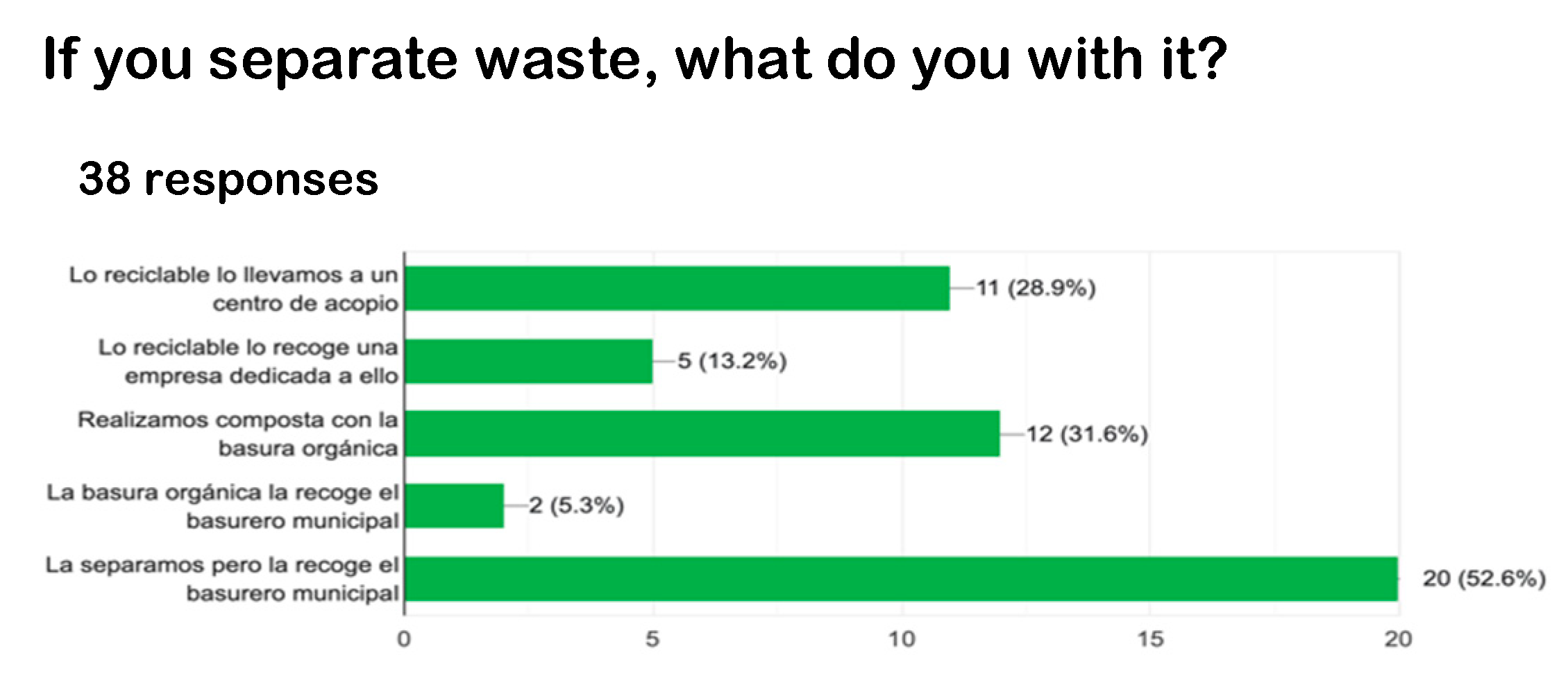

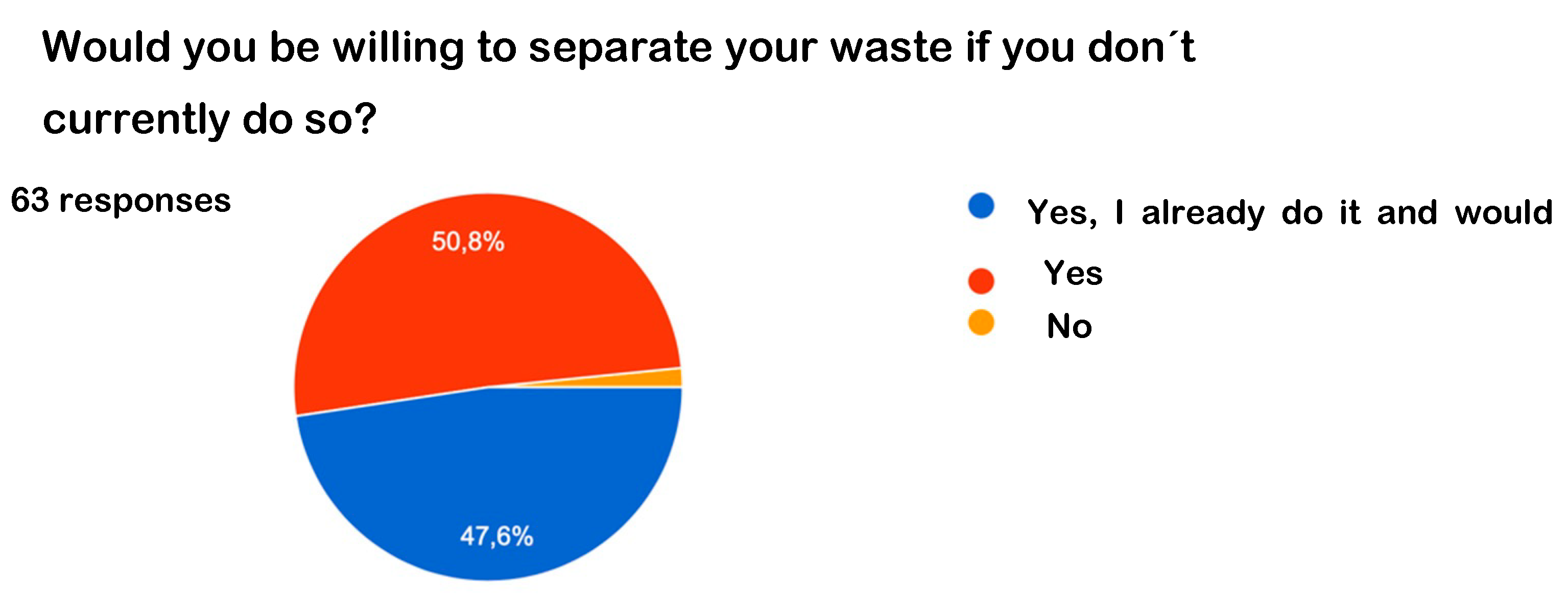

Following the analysis of the survey results, several key aspects were identified to guide the implementation of environmental strategies. One such aspect is waste separation: 54% of surveyed households reported separating their waste, but among them, 53% rely on municipal collection services—where proper sorting only occurs in some areas of Mexico City. In many other states, this practice is still lacking.

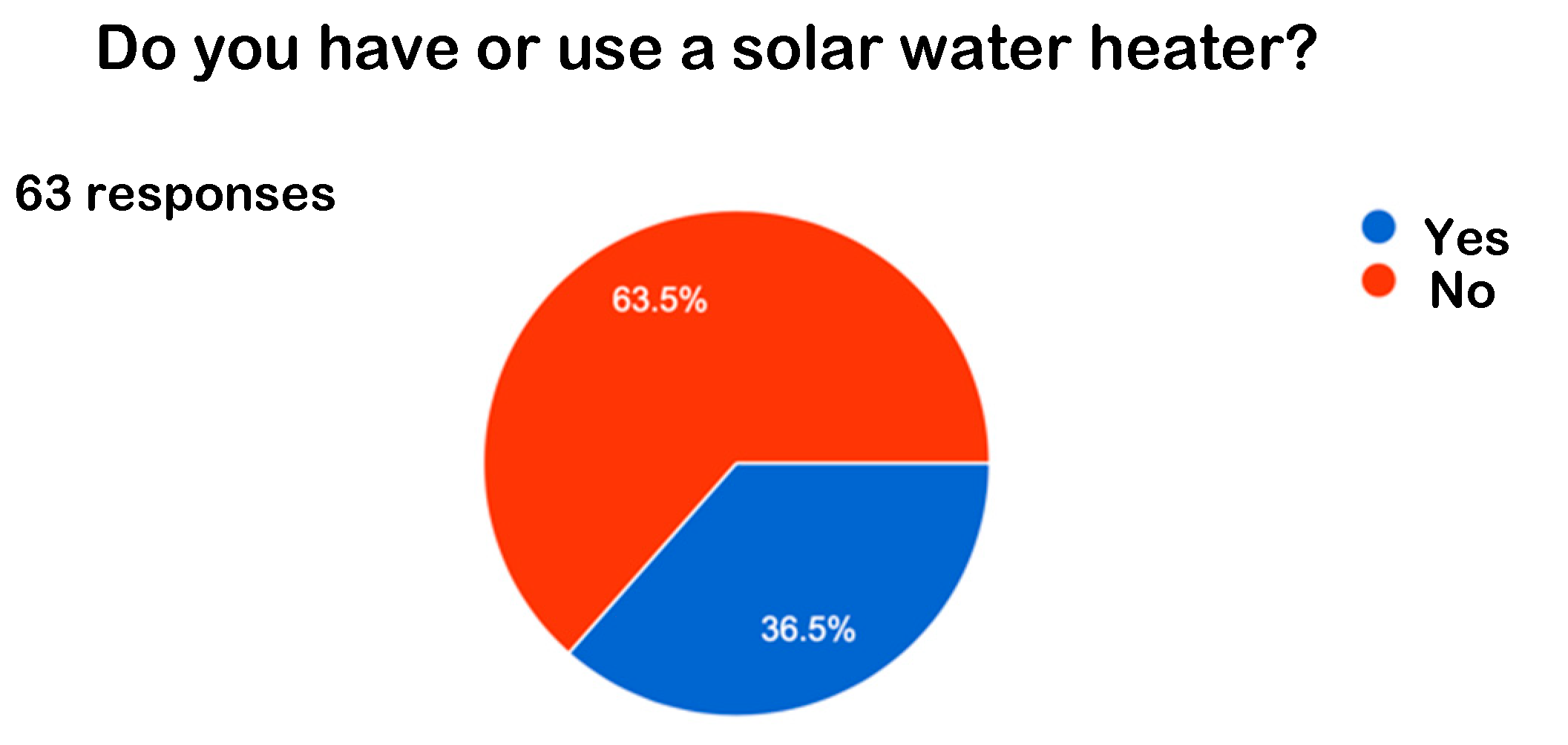

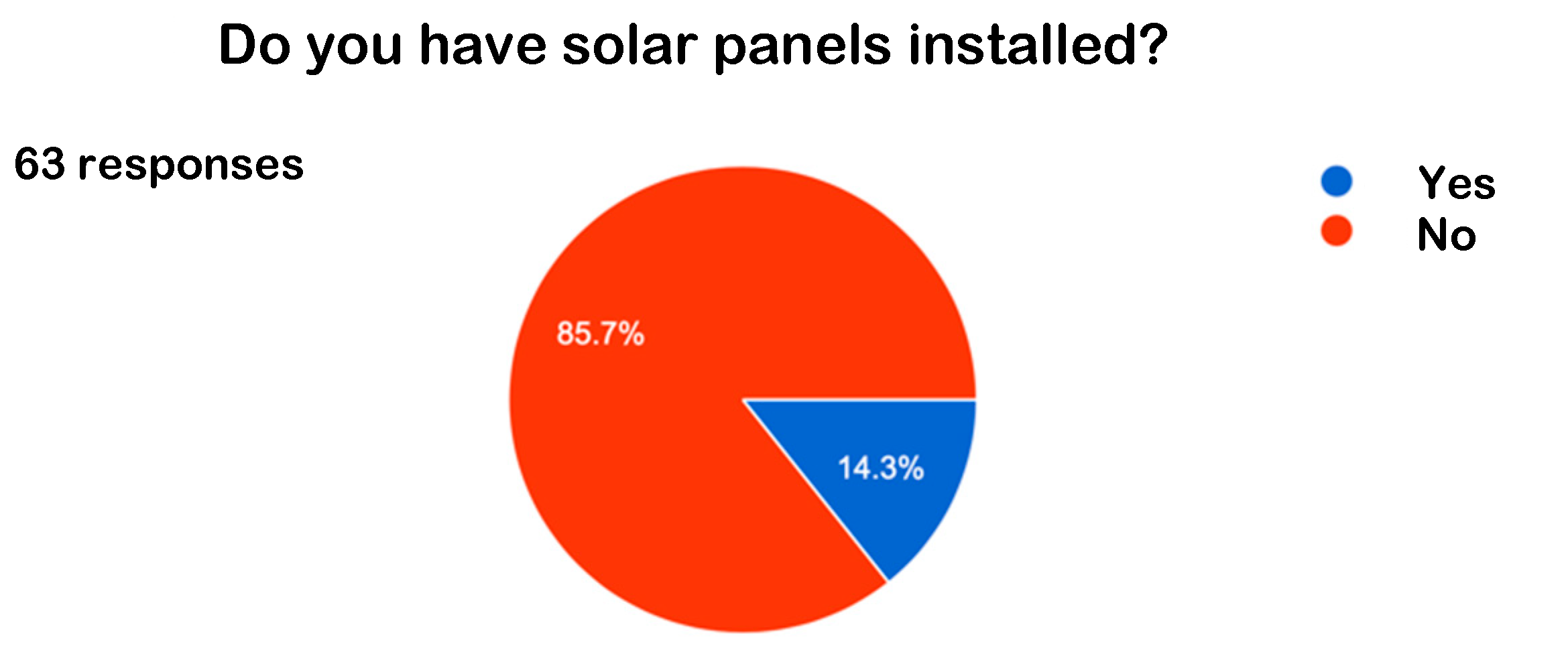

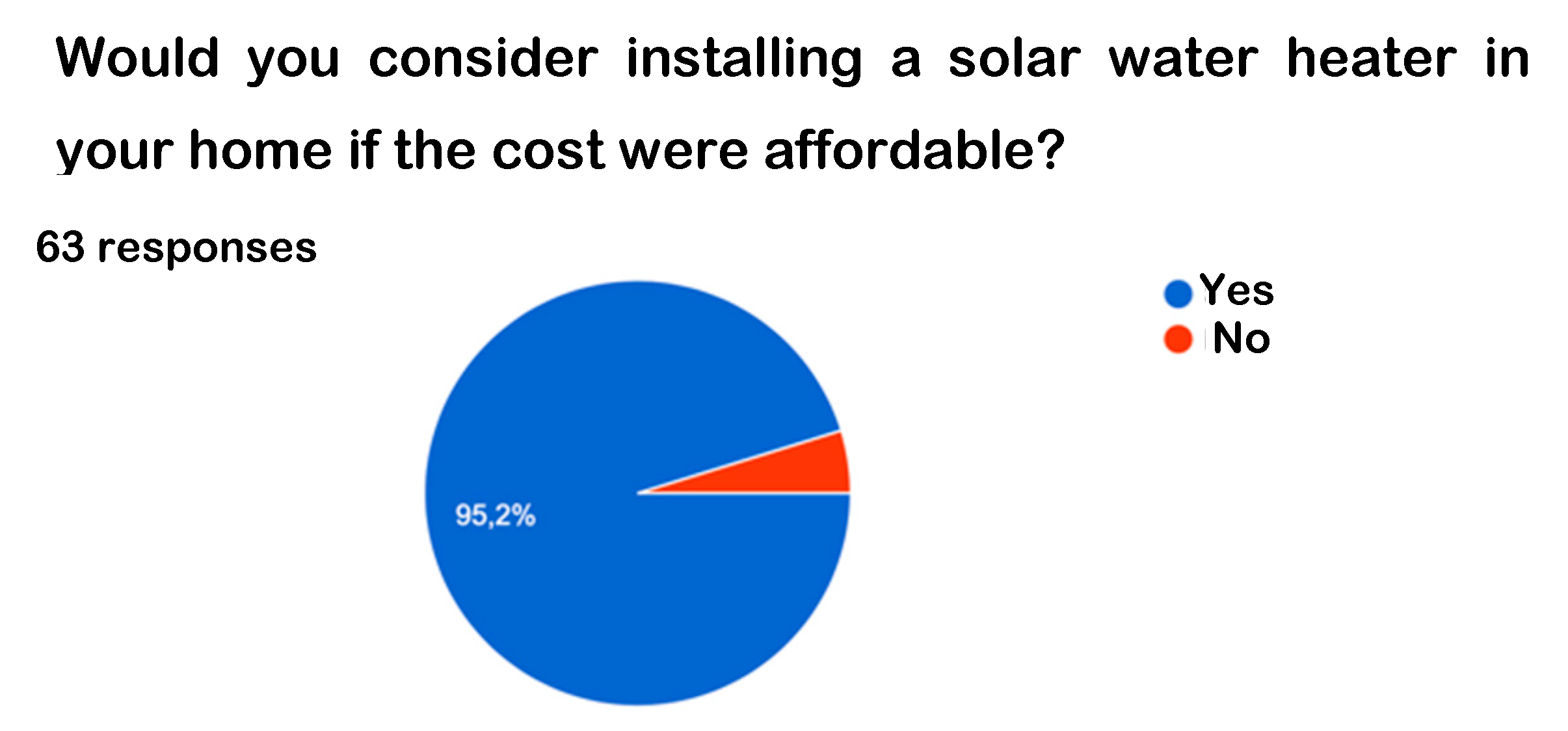

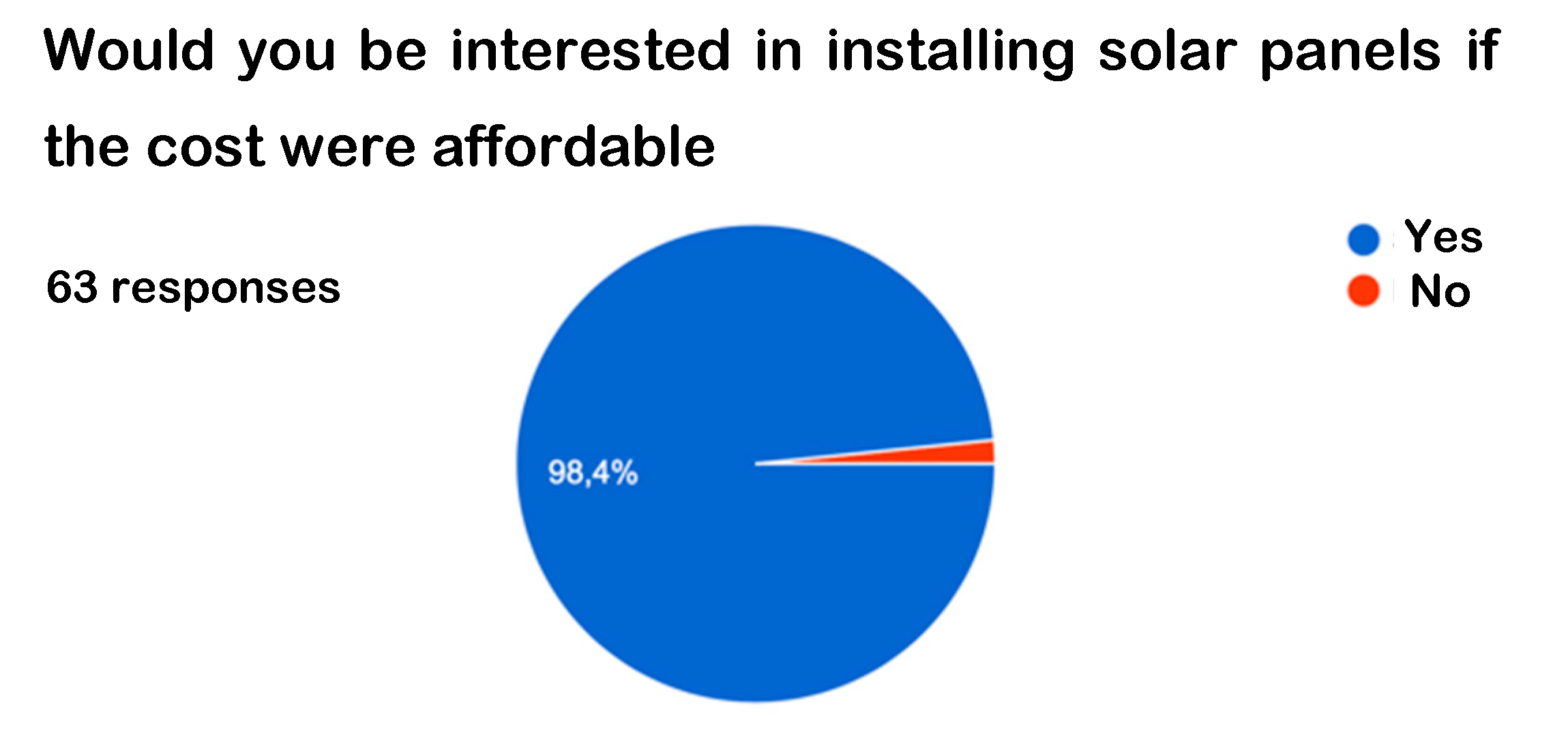

In terms of climate, Mexico holds significant advantages over Germany, with six more hours of sunlight per day and nearly twice the solar radiation—factors that favor the use of solar energy (Radiación solar en México – Amevec, n.d.; Horas de luz solar en Freiburg (Alemania) - Año 2024, n.d.). Despite this, the survey results revealed that only 36% of participants have a solar water heater, and just 14% use solar panels. The main barrier to adoption is the high cost of purchasing and installing such technologies. However, over 95% of respondents stated they would be willing to install them if they were more economically accessible (López, 2024).

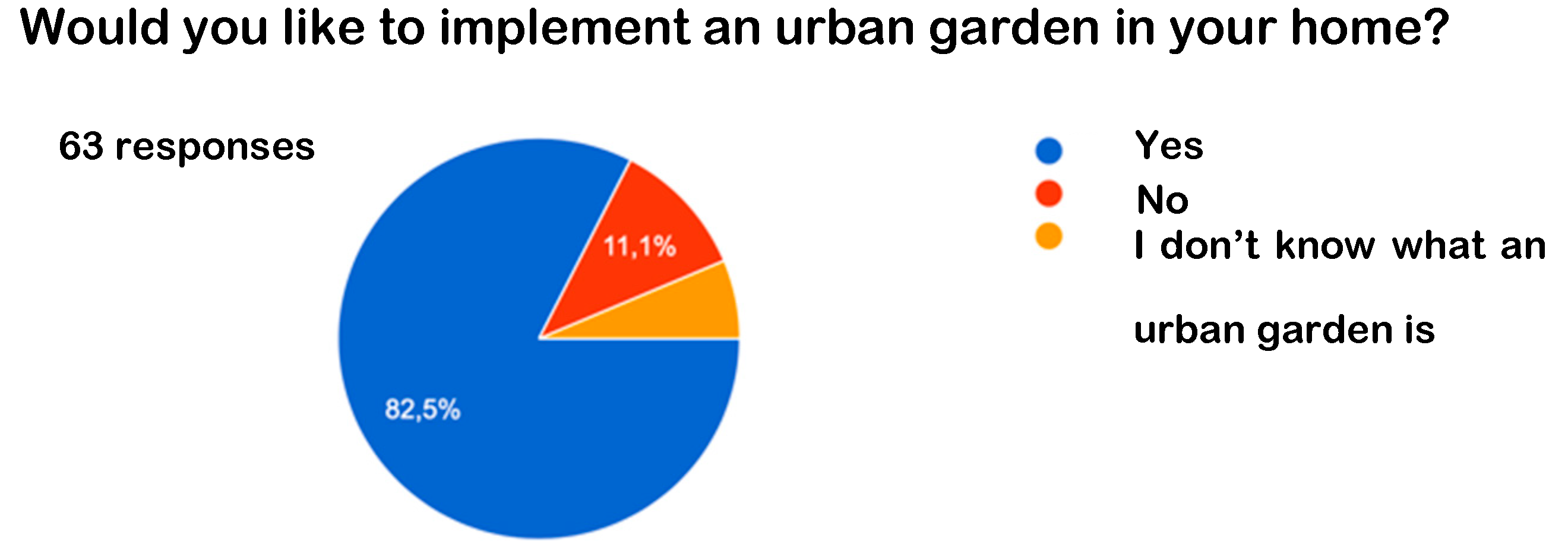

Mexico’s favorable climate and low-cost access to a wide range of fruits and vegetables offer a significant advantage for the development of low-maintenance urban gardens. Many of these crops are readily available in local markets or even grow on street trees. Likewise, aromatic herbs are especially easy to grow—even in small pots. Nonetheless, only 14% of respondents currently have a home garden, while 82% expressed interest in starting one. This suggests that by offering practical ideas and options for creating urban or household gardens, adoption could be strongly encouraged. To achieve this, it would be essential to develop proposals adapted to various housing types, maximizing feasibility and acceptance.

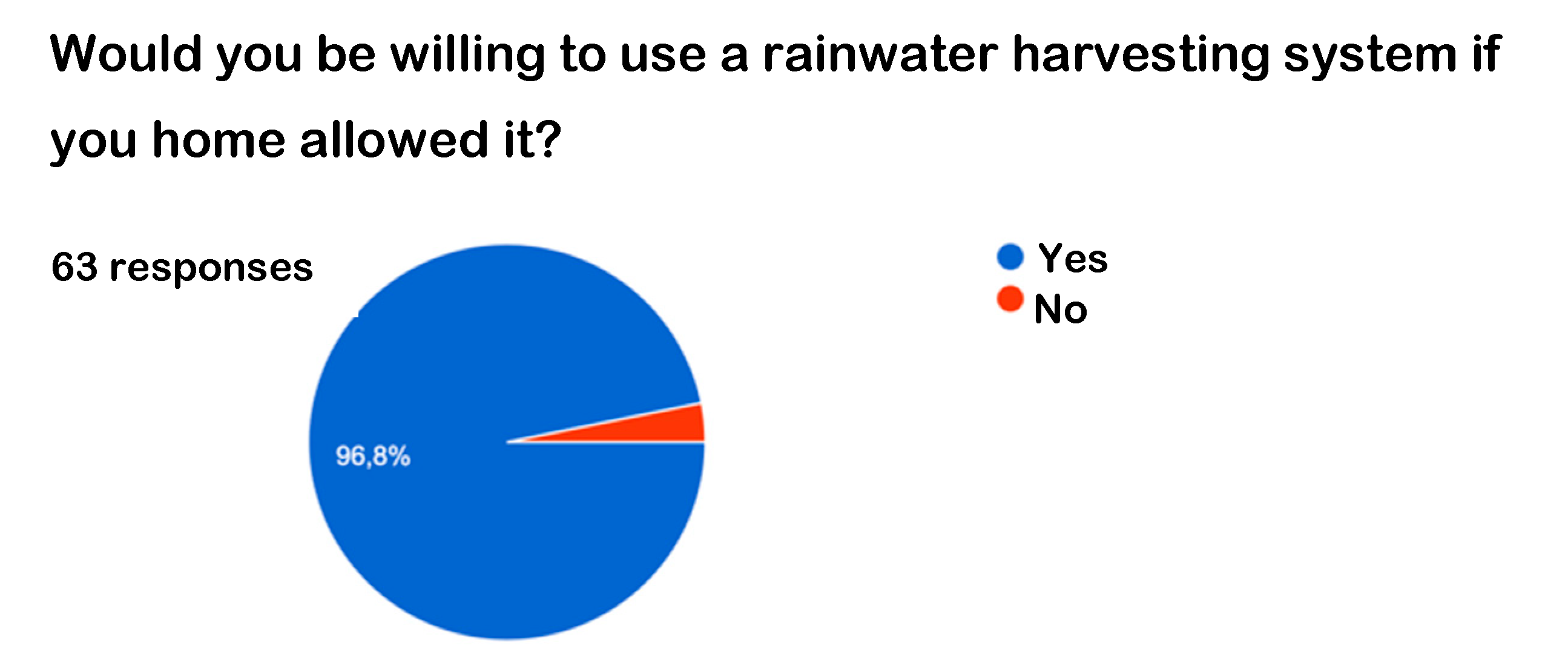

Another aspect analyzed in the study was rainwater harvesting. According to the survey, 82% of participants would be willing to implement a rainwater collection system. However, its economic viability varies by region. In areas with low precipitation, the return on investment is slower, while in regions with favorable weather conditions, this system represents a highly beneficial solution (Clima: Los 5 estados más lluviosos de México, n.d.). Rainwater harvesting is not the only strategy for water conservation; greywater treatment offers another sustainable alternative, allowing for the reuse of water for non-potable purposes such as garden irrigation or toilet flushing. These systems have the advantage of being applicable throughout the country. Survey responses also suggest that most people would be willing to adopt such technologies if affordable and cost-effective options were available.

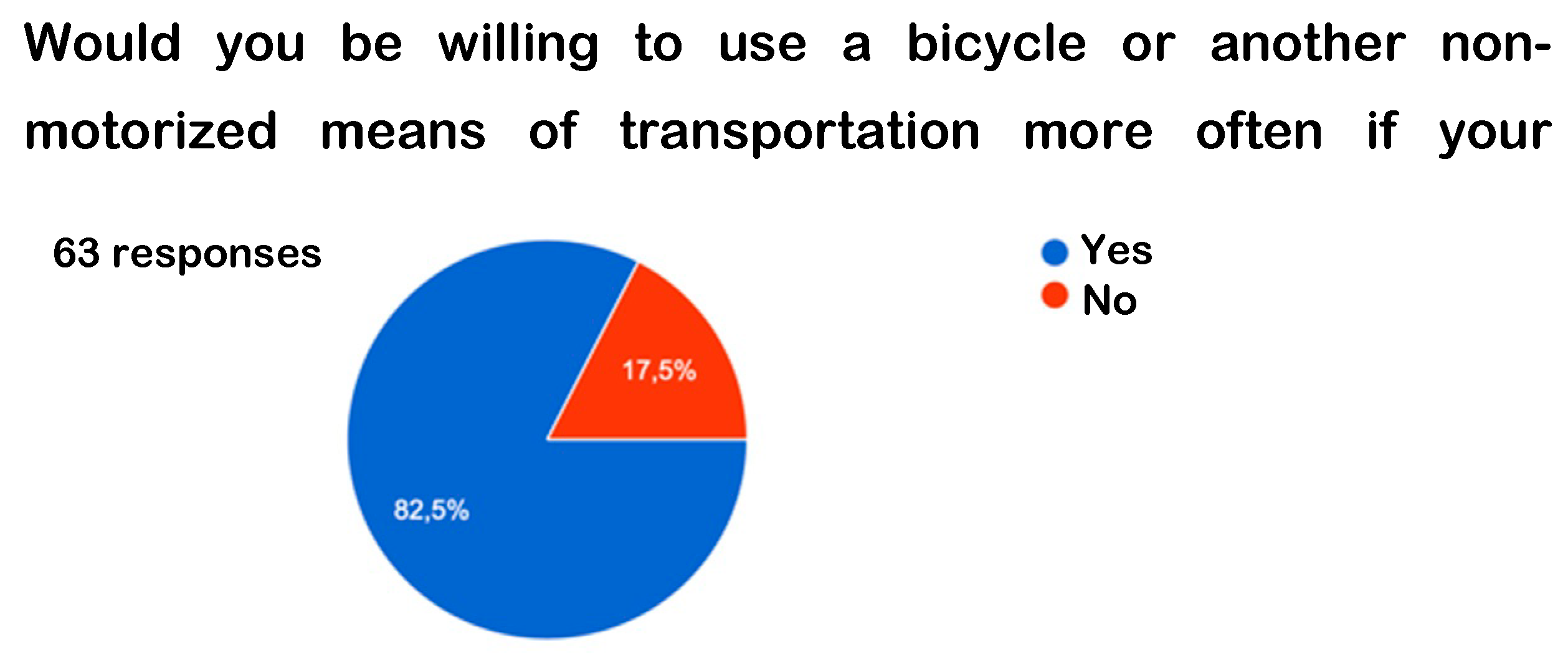

Finally, survey results showed that 77% of respondents do not use non-motorized modes of transport in their daily routines, primarily due to urban environments that do not support them. However, 82% indicated they would be willing to incorporate them into their daily lives if adequate infrastructure existed. While this represents a disadvantage compared to Vauban’s urban model—where the layout and road system are designed to prioritize sustainable mobility—it is still possible to promote improvements both at the household level and within broader urban infrastructure. Such changes could encourage the use of non-motorized transport, fostering more accessible and sustainable urban environments.

Although Germany, as a developed country, benefits from a strong foundation in environmental education, this does not preclude the implementation of effective changes in Mexico. Clearly communicating the individual and national environmental and economic benefits of these strategies could serve as a strong incentive for their adoption.

Development of Recommendations

The proposed recommendations encompass both individual solutions and actions that require the involvement of government institutions. Regarding waste collection, it is essential to demand that municipalities implement proper waste separation services. However, this also calls for greater social responsibility, as many citizens lack both incentives and education on waste management. Therefore, it is necessary to promote environmental education through schools, public workshops, and awareness campaigns, encouraging households to adopt waste separation practices. In parallel, authorities must be urged to change current dynamics and make the necessary investments.

In terms of non-motorized transport, road safety education is required to protect pedestrians and cyclists—an issue often overlooked. Additionally, local governments must be held accountable for the installation of secure bike parking areas, as many existing racks are unsafe or poorly located, increasing the risk of theft. Furthermore, the construction of functional bike lanes and the implementation of public bike-sharing systems should be promoted.

Regarding renewable energy, it is recommended that all municipalities allocate resources for the installation of technologies such as solar water heaters, which offer substantial benefits even if not applied universally. The use of energy-saving lightbulbs should also be encouraged through giveaways or discount programs.

Although these recommendations could significantly improve environmental outcomes, their effective implementation in Mexico will require strong social organization. While international examples like the German ecodistrict demonstrate that change is possible through community involvement, the process is likely to be slower in developing countries.

Thus, the proposed solutions involve both the private sector and accessible options for different types of housing in Mexico. The strategies are categorized into four key areas: waste separation, clean energy use, efficient transportation, and urban gardening. Each category includes specific recommendations adapted for both stand-alone homes outside of residential complexes and those located within gated communities or condominiums.

For homes in residential complexes, a case study was developed based on a housing cluster of 92 units located in the historic center of Querétaro. This case provides a more concrete analysis, including cost estimates, benefits, and a realistic and comprehensive proposal.

- 1)

Recommendation for Waste Separation and Collection:

- a)

In Gated Communities:

In this context, it is recommended to start with an informational session or workshop led by specialists within the community, in order to raise awareness and present the suggested changes.

Following this, the implementation of a designated area for the proper disposal of each type of waste is advised, clearly labeled with appropriate signage to ensure effective sorting.

To ensure compliance with waste separation, it is recommended to establish a monitoring system accompanied by internal penalties that encourage proper implementation. Once waste has been sorted, it becomes necessary to hire a specialized waste collection service. In Mexico, there are several companies dedicated to this task, although their availability and service features vary depending on the state. It is important to note that most of these services involve a cost, which is directly linked to the volume of waste generated and the location of the residential area.

For organic waste, a specific strategy is proposed: the implementation of a composting container. This container should include simple instructions (e.g., adding soil or dry leaves each time organic matter is deposited), enabling the production of compost suitable for use in gardens or green areas within the residential complex.

It is essential that this process be carried out under controlled conditions to prevent pest proliferation. The location of the composting container should be planned to ensure functionality and avoid inconvenience. With adequate space and efficient waste management, high-quality compost can be produced, benefiting green spaces and potential cultivation areas within the community.

b) In standalone homes (outside residential complexes):

In most municipalities across Mexico, there are recycling centers that accept various types of recyclable materials such as paper, cardboard, plastic, glass, and metals. However, their use remains limited due to the lack of a well-established culture of waste separation at the source, and a general scarcity of public information.

Therefore, it is recommended to implement information and awareness campaigns that actively promote household-level waste separation, emphasizing environmental, economic, and social benefits to motivate families to bring their sorted waste to designated recycling centers.

Additionally, neighborhood-level organizational models should be encouraged to allow residents to collectively hire private recycling collection services. This strategy would not only facilitate the proper disposal of recyclable materials but also foster a sense of shared responsibility, thereby promoting more effective local environmental management.

- 2)

Recommendation for renewable energy:

In both residential complexes and standalone homes:

A shared installation model is proposed for both contexts. The suggested photovoltaic system is designed to serve 12 people (approximately four homes) with a 6 kWp solar system, consisting of approximately 12 solar panels.

Estimated cost of the full system: $6335.67 USD(includes panels, inverter, mounting structure, installation, and grid connection to CFE)

Cost per household: $1583.92 USD

In residential complexes, installation costs may be lower due to standardized roof conditions, easier access, and the ability to centralize the system. Shared infrastructure can reduce logistics, maintenance, and installation costs by up to 15%, lowering the cost per home to approximately $ 1346.33 USD (López, 2024).

Estimated savings and payback period:

Average monthly electricity bill: $7.92 USD

Monthly savings per household: $7.92 USD

Annual savings: $95.04 USD

-

Initial investment per household:

- ○

Residential complexes: $1346.33 USD

- ○

Standalone homes: $1583.92 USD

Payback period:

Additional benefits:

System lifespan: 25 to 30 years

Property value increase: 3% to 6%

CO₂ reduction: 1,200 kg per year per system

3)

Recommendation for water use and treatment:

It is proposed to implement rainwater harvesting systems, combined with simple filters, to reuse water for non-potable purposes such as irrigation and cleaning. These systems can be installed on sloped roofs with gutters and storage tanks for shared or individual use.

In residential complexes, water harvesting can be implemented collectively, while in standalone homes, it can be adapted to patios or rooftops. The main benefits include reducing potable water consumption, increasing resilience during water supply interruptions, and fostering greater awareness of the water cycle among residents. Basic treatment through sand filters, activated carbon, and chlorine ensures water quality for selected domestic uses.

- 4)

Recommendation for non-motorized transportation:

To promote non-motorized transport, the design and implementation of safe, shaded pedestrian and cycling paths is recommended within and around residential complexes. These paths should include signage, night lighting, and vegetation to provide thermal comfort.

For standalone homes, strategies may focus on encouraging bicycle use through the installation of secure bike racks, community campaigns, and local “bike routes” (bici-rutas). Beyond economic savings, benefits include improved cardiovascular health, reduced vehicle congestion, and stronger community engagement.

- 5)

Recommendation for urban and backyard gardens:

Finally, the integration of urban gardens in residential complexes and backyard gardens in standalone homes is proposed. These gardens can be adapted to rooftops, shared green areas, or small backyard spaces, depending on the housing type.

The benefits of gardening are not only nutritional, but also social, educational, and psychological. Gardening fosters neighborly cooperation, promotes environmental education, and reduces stress. Furthermore, green areas act as microclimates, helping to regulate local temperature and enhance urban biodiversity.

Conclusion

The Vauban eco-neighborhood in Freiburg, Germany, is a successful model of sustainable urban development that effectively integrates waste separation, clean energy, efficient transport, urban gardens, and social cohesion. Its experience demonstrates that the combination of innovative urban design, active community organization, and institutional support is essential for achieving environmentally responsible and socially inclusive urban growth.

By comparing this model to the current state of Mexican neighborhoods, several challenges are identified, including limited waste management infrastructure, high costs and low access to renewable technologies, poor promotion of non-motorized transport, and underdeveloped urban gardening initiatives—despite favorable climate and space availability.

Survey results show that young Mexican residents are highly willing to adopt sustainable practices, provided there are economic incentives and appropriate institutional and community support. Therefore, adapting the Vauban model to the Mexican context requires scalable strategies that combine individual actions with public policy and education programs to overcome socioeconomic and cultural barriers.

In conclusion, the proposed recommendations, tailored for different housing types and neighborhood contexts, demonstrate that transitioning toward eco-neighborhoods in Mexico is both viable and beneficial. Achieving this transformation will depend on the development of a strong environmental culture and collaborative efforts among citizens, private sectors, and governments, converting current challenges into real opportunities for sustainable urbanization.

References

-

Barrio de Vauban: la ciudad del futuro está en Friburgo. (s/f). Retrieved November 24, 2024. Available online: https://viajes.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/barrio-vauban-ciudad-futuro-esta-friburgo_17680.

-

Clima: Los 5 estados más lluviosos de México. (s/f). Retrieved December 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.informador.mx/mexico/Clima-Los-5-estados-mas-lluviosos-de-Mexico-20240529-0118.html.

-

Contenedores en Islas de Reciclaje. (s/f). Retrieved December 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.contenedoresdebasura.com.mx/reciclajedebasura.html.

-

En promedio, cada persona genera diario 994 gramos de basura en México: CRIM-UNAM – La Crónica de Hoy México. (s/f). Retrieved December 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.cronica.com.mx/academia/promedio-persona-genera-diario-kilo-basura-mexico-crim-unam.html.

- Fastenrath, S., & Braun, B. (2018). Sustainability transition pathways in the building sector: Energy-efficient building in Freiburg (Germany). Applied Geography, 90, 339–349. [CrossRef]

-

Horas de luz solar en Freiburg (Alemania) - Año 2024. (s/f). Retrieved November 24, 2024. Available online: https://www.tutiempo.net/horas-luz-solar/freiburg.html.

-

Radiación solar en México – Amevec. (s/f). Retrieved November 24, 2024. Available online: https://amevec.mx/radiacion-solar-en-mexico/#.

-

Recolección De Basura - Grupo Resica. (s/f). Retrieved December 9, 2024. Available online: https://gruporesica.com.mx/.

- Secretaria de medio ambiente y recursos naturales. (2020). Diagnóstico básico para la gestión integral de los residuos. Libro digital. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/554385/DBGIR-15-mayo-2020.pdf.

-

Seis casos de éxito de ecobarrios sostenibles | Connections by Finsa. (s/f). Retrieved November 24, 2024. Available online: https://www.connectionsbyfinsa.com/seis-ejemplos-ecobarrios/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).