1. Introduction

Urban livability has emerged as a crucial concept in the fields of urban studies, planning, and development, particularly in the context of mid-sized cities in the Global South [

1,

2,

3]. As these cities face fast paced urbanization, concerns about equitable and sustainable livability have gained prominence [

4,

5]. Urban planning in mid-sized cities of the Global South routinely presents unique challenges and opportunities owing to their rapid growth and unplanned physical development [

3,

6]. The present study aims to critically examine urban livability dynamics empirically by assessing both subjective perceptions and objective indicators, a dual approach that acknowledges the complex and interrelated factors shaping urban environments. With increasing urbanization in mid-sized cities of the Global South, inclusive urban planning is crucial as it involves engaging local communities in shaping their environments, understanding their unique needs, and addressing contextual factors such as locational attributes and environmental conditions. Following this, there are two main objectives this study aims to accomplish. First, it examines the spatial dynamics of urban livability within the setting of Khulna City, Bangladesh, to enhance knowledge about the level of urban livability with the depth of nuances conducive to effective planning and design of urban environments. Second, it covers a significant research gap by seeking to determine the degree of concordance between the objective geographical livability ratings of neighborhoods and the subjective opinions of city dwellers and to highlight circumstances conducive to discrepancies. In this endeavor, this research espouses a broad community perspective, underscoring the vital role that both the experts’ opinions and local residents’ personal insights play in urban planning and design. This lens brings into focus the critical role of local communities besides the experts in visioning and shaping the urban environment, thus pointing to a broader commitment towards planning and designing more livable and more sustainable cities. This study underlines the need to adequately represent the variety of urban experiences and perspectives.

In recent years, the notion of "urban livability" has gained significant attention, leading to the emergence of research on the evolving development patterns in rapidly growing urban areas [

7,

8]. It has acquired various meanings, encompassing choices individuals make regarding their residential preferences, as well as the notion of preparing urban areas for better living conditions [

9,

10,

11]. A livable urban setting refers to a location where the physical infrastructure and constructed surroundings are intentionally created to improve the residents' living conditions by satisfying their fundamental requirements. According to this viewpoint, livability may be defined as the degree to which locals engage with their living environment [

12,

13]. Due to its complexity and variety, the concept of livability lacks a precise or universally accepted definition [

14,

15]. Since "livability" is a relative concept, its significance may vary depending on the context of time and culture. The specific definition of livability depends on the context, chronology, and evaluation objective, as well as the valuing structure of the observer. Hence, there is no agreed-upon description of what makes something livable as its outcome. This would typically include a number of dimensions and several criteria and sub-criteria [

16].

Over the last century, urbanization has accelerated significantly in most countries. Not only the rate of geographic extent of cities has soared [

17,

18], but urban areas are also expanding twice as quickly as their population [

19,

20] and by 2050, urban areas are expected to accommodate approximately 68% of the world population [

3]. On the one hand, this expansion of urban areas has resulted in noticeable changes to urban landscapes; experts have noted that uncontrolled expansion and inadequate planning have a significant impact on the life expectancy of its residents, on the other hand [

6,

21,

22,

23]. Also, the lack of proper planning for emerging mid-size cities in developing countries in particular is hampering the living conditions of city dwellers [

5,

24]. The haphazard growth of cities in developing countries like India, Bangladesh, and others has resulted in a range of negative consequences [

5,

25] like traffic congestion [

26], environmental pollution [

27,

28,

29], and increasing pressure on urban ecology [

30], among others. In these circumstances, researchers and policymakers have made strides to enhance the condition of urban life [

31,

32]. Although the idea of a livable city was first advanced to draw and retain multinational firms, it has now developed into a significant driver of the government's adoption of sustainable urban development policies [

33]. This highlights the growing concern regarding effective strategies for overseeing sustainable urban development [

34,

35,

36] and sustainable urban land-use policies to ensure the future well-being of city dwellers [

37].

Livability assessment is gaining increasing importance as a driver for sustainable and livable urban development [

38] and is considered crucial for enhancing urban livability in developing countries [

31,

39]. Tracking urban livability in cities supports efforts to mitigate the detrimental consequences of future urban settlements development [

32,

40,

41]. In this context, it has been noted that livability studies are gaining significance in developing nations [

8,

42]. Urban planners and other practitioners of urban science pay close attention to urban livability as a balanced and harmonious approach to city development [

43,

44]. Many Chinese cities have already started to give heed to this concept and to incorporate it as one of the objectives for long-term sustainable urban development [

8,

39,

45]. Also, the Indian government has recently made the decision to implement an urban livability index based on a variety of variables, including population, basic infrastructure, historic value, heritage preservation, tourism, crime rate, and public transit system [

4]. Recommended by various organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO), this assessment system uses a four-dimensional framework that focuses on the concepts of convenience, amenity, health, and safety. It can be applied to evaluate the livability potential of any city [

7]. Based on this evaluation approach, this study examines the spatial dynamics of livability in Khulna City, Bangladesh, by using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) grounded in expert opinions to conduct an explicitly spatial fine-grain analysis. A suite of variables has been selected by the experts to measure livability, which encompasses the recommended dimensions of livability assessment by WHO. We validate this approach by assessing how closely the objective geographical livability aligns with the subjective perceptions of city dwellers based on their lived experiences with a survey of city dwellers. Thus, this twofold approach provides valuable insights into how residents perceive a place as more livable and underscores the role of bottom-up visions that should frame future urban design and developments.

Research on urban livability has often relied on social statistics or surveys [

32,

46], overlooking the fine-grain geographic information and the sensitivity of community specific factors, which points to a critical research gap [

3,

7]. Indeed, relying solely on subjective measures may not provide urban planners with the precise findings needed for effective planning, given the substantial needs of fast growing Global South cities. While few studies have combined the subjective perception of geographic data at the community level [

47], extending this approach for entire cities, especially in developing countries with unplanned urban growth, remains understudied. Additionally, the exclusion of mid-sized cities from comparative livability assessments neglects their significant role in sustainable city planning, as most studies have focused predominantly on megacities [

48,

49]. Deeply comprehending urban livability and its application in mid-size cities is crucial for supporting sustainable land-use policies and motivating governments to adopt sustainable urban development strategies that mitigate the negative impacts of unplanned development on urban settlements [

32,

33,

45]. Therefore, determining the status of urban livability for mid-sized cities in Bangladesh is fundamental to guiding urban governments in addressing the adverse consequences of unplanned development and fostering sustainable urban growth.

This study offers significant contributions to sustainable urban planning and design in the Global South, emphasizing the importance of integrating both expert insights and local community engagement and their complementarity. No prior studies have systematically examined the coexistence of objective indicators and subjective perceptions of urban livability within the context of mid-sized cities in the Global South, where rapid urbanization and unique socio-environmental challenges demand localized and context-specific solutions. By highlighting the coexistence of subjective perceptions and objective livability indicators, this research acknowledges the intrinsic value of resident’s experiences alongside professional urban assessments. The duality effect strongly aligns with Jane Jacob’s foundational principles of local community engagement [

50] by integrating the perspectives of local citizens into the planning process. It also resonates with the contemporary 15-minute city concept, which emphasizes accessibility and inclusivity in urban design, making it particularly relevant to the challenges faced by mid-sized cities like Khulna. For cities across the Global South, this study also underscores the importance for land-use strategies that prioritize proximity to services and amenities, ensuring that urban planning is both socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable. This approach not only offers a practical framework for policymakers to initiate informed decisions but also serves as a potential model to address the unique needs of mid-sized cities for establishing socially inclusive, environmentally responsible, and high-quality urban living environment, while preserving diversity. Moreover, by advocating for inclusive and planned urban development to city development authorities, this study provides a strategic model to manage and control future development in a planned manner for achieving UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) [

48].

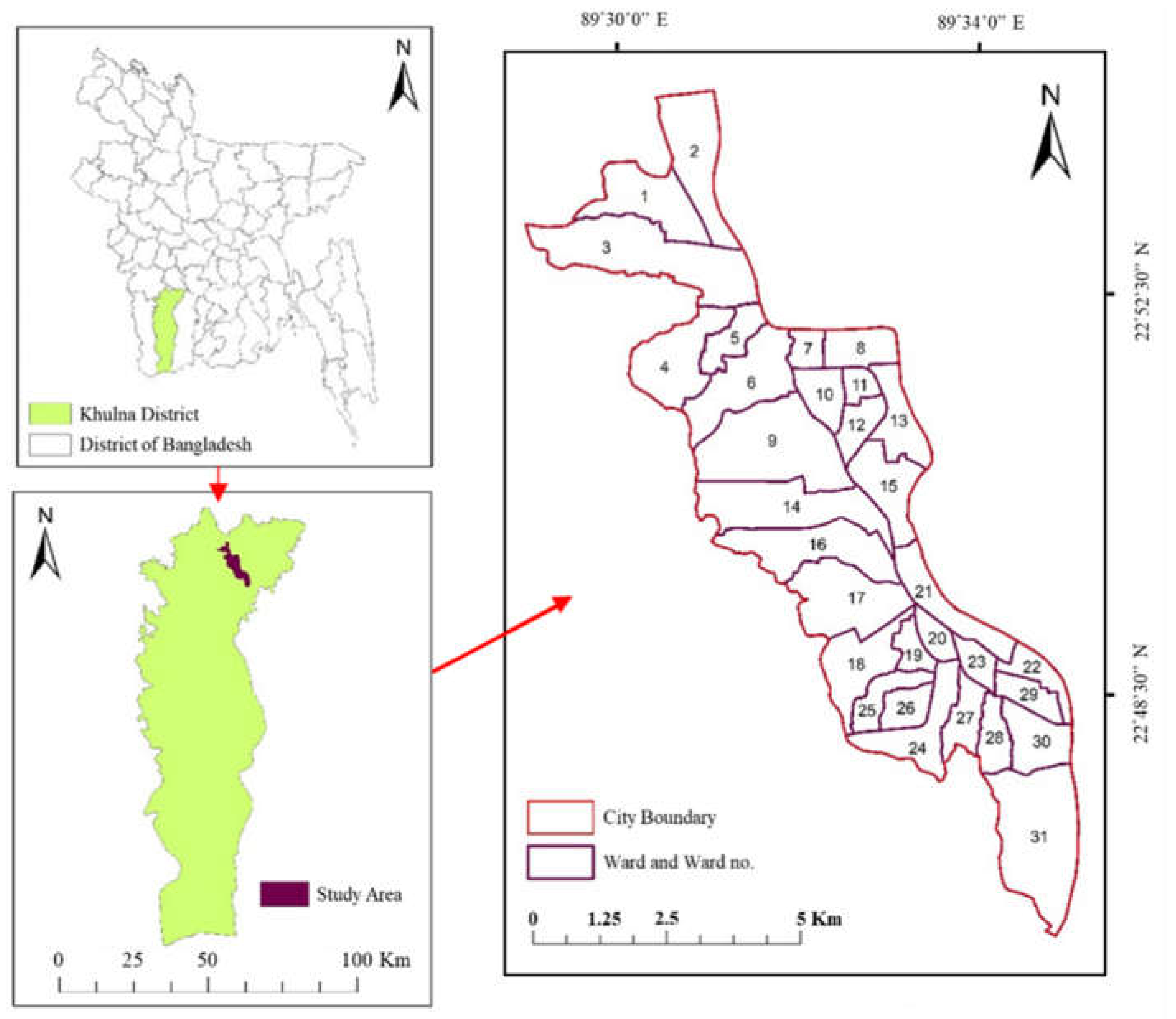

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

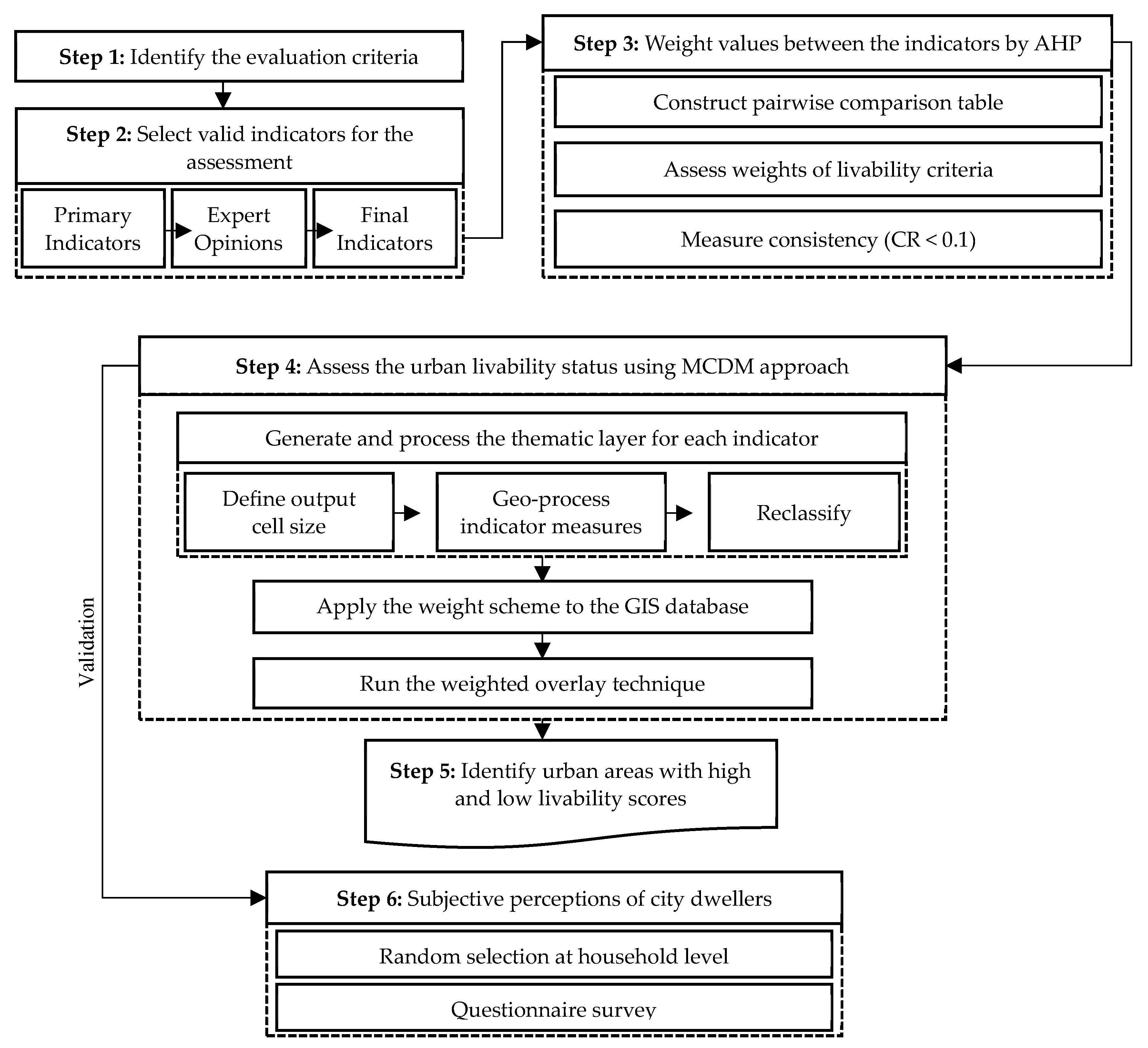

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of research.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of research.

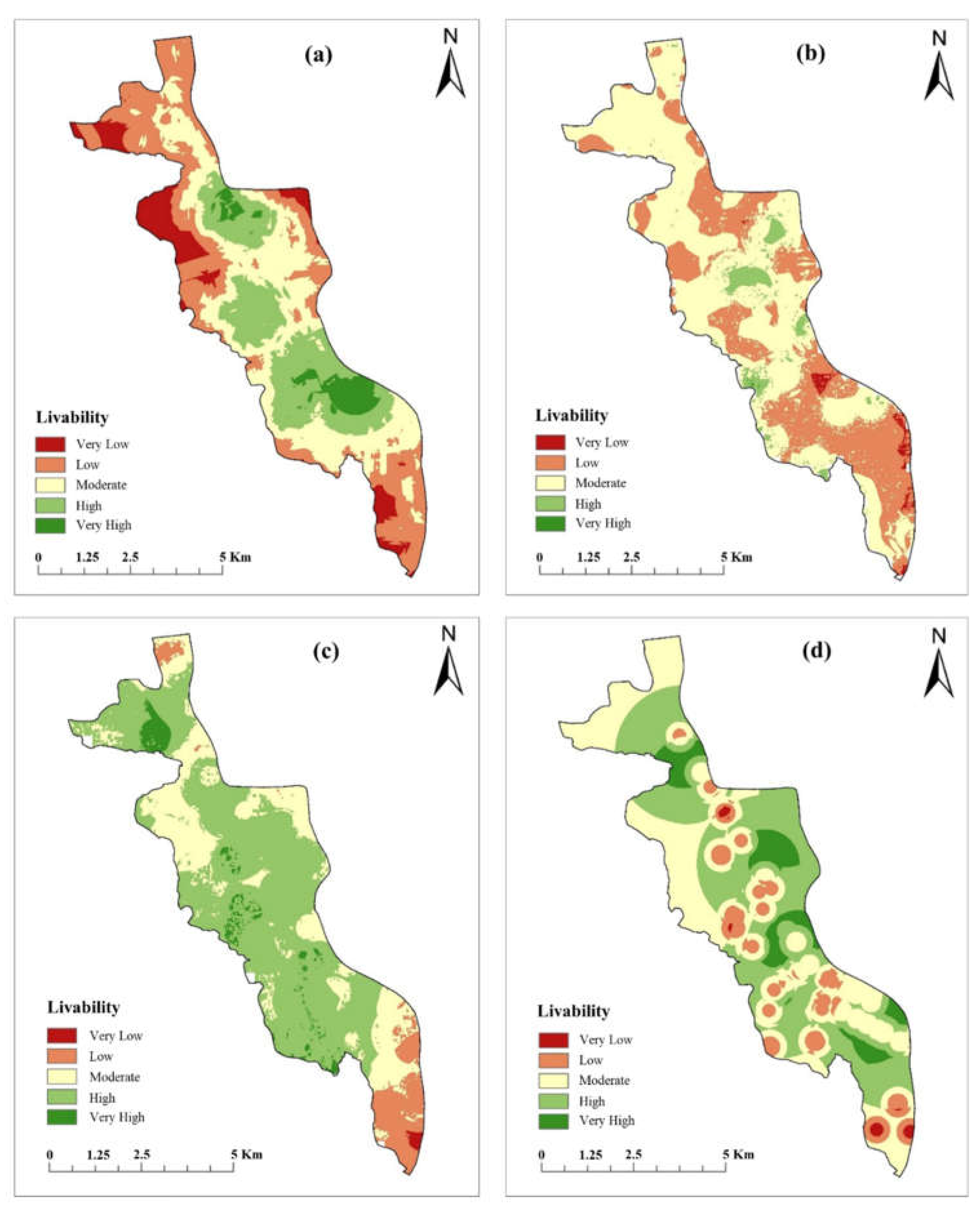

Figure 3.

Livability status of Khulna City in terms of (a) Convenience, (b) Amenity, (c) Health and (d) Safety.

Figure 3.

Livability status of Khulna City in terms of (a) Convenience, (b) Amenity, (c) Health and (d) Safety.

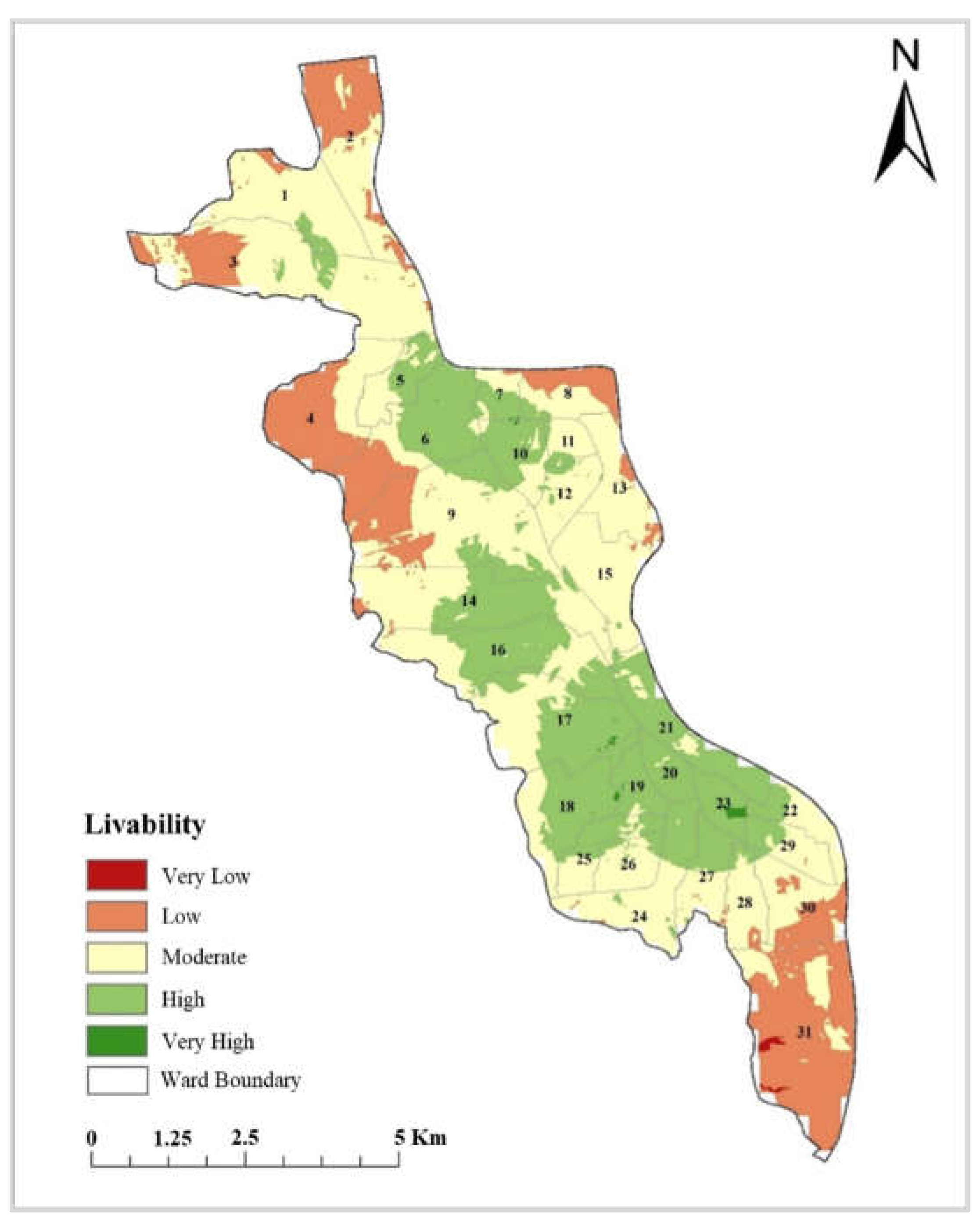

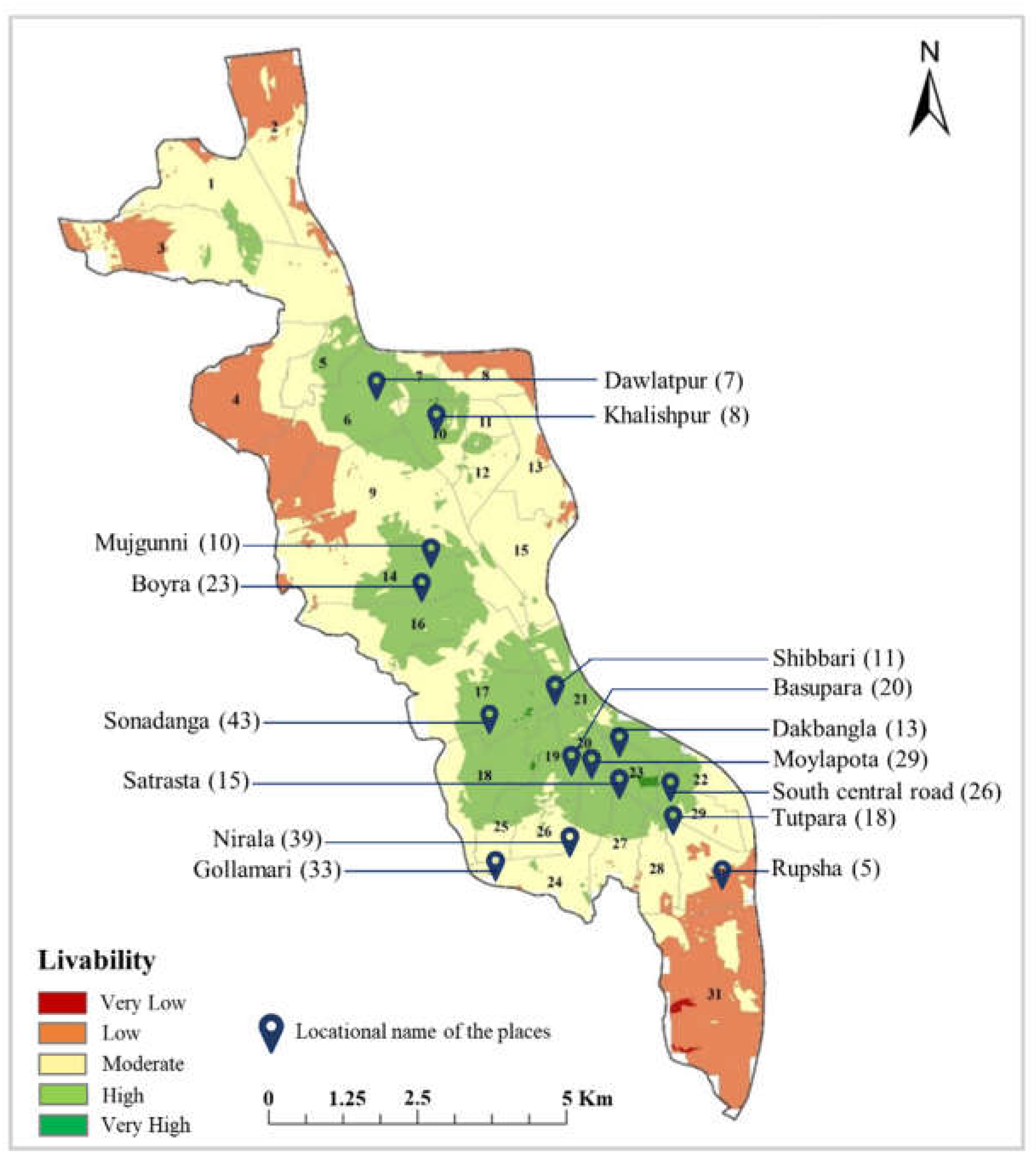

Figure 4.

Urban livability mapping for Khulna City.

Figure 4.

Urban livability mapping for Khulna City.

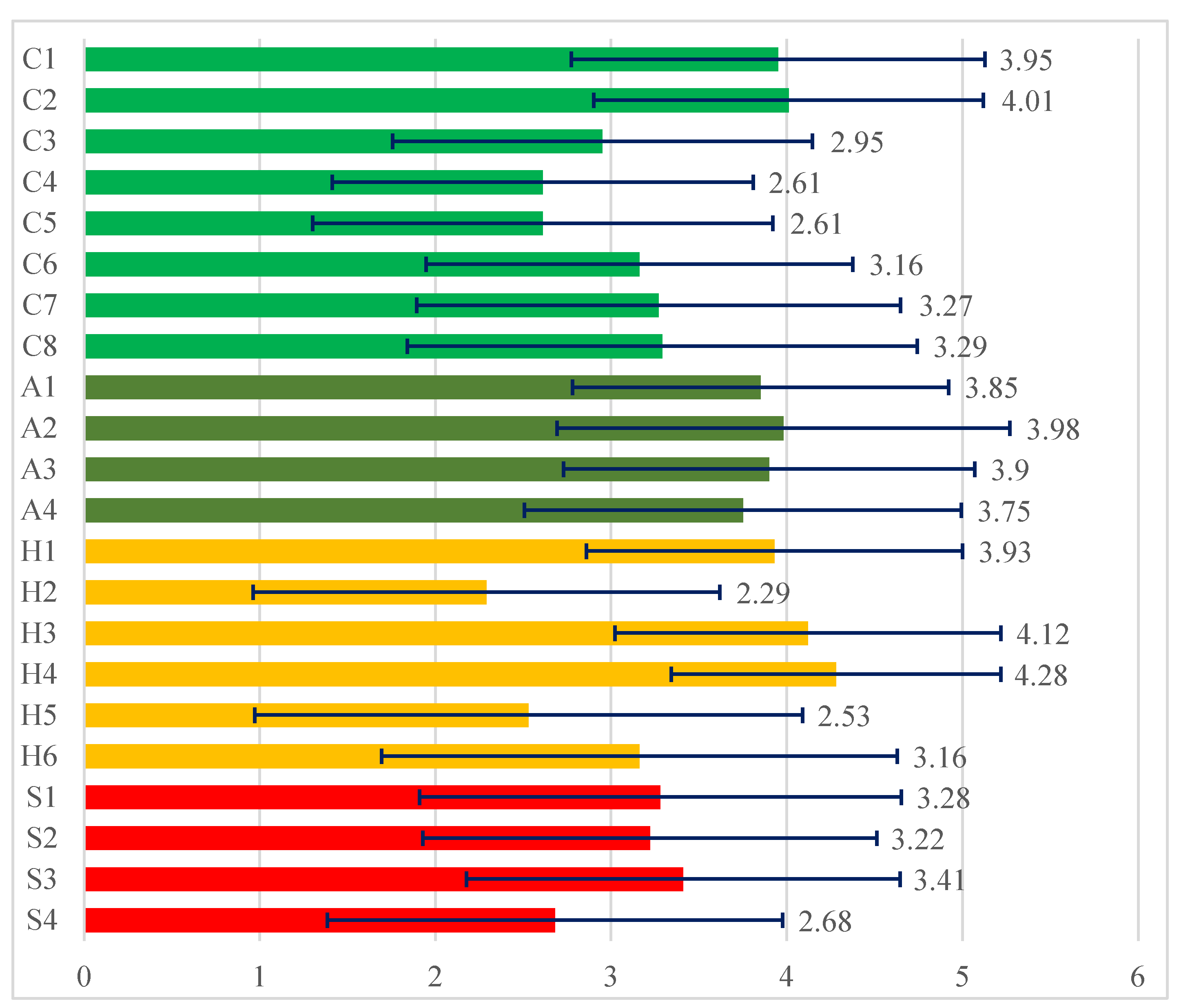

Figure 5.

Average subjective scoring on the indicators of urban livability and their standard deviation: (C1) Distance to city center, (C2) Distance to major road, (C3) Distance to bus terminal, (C4) Distance to train station, (C5) Distance to post office, (C6) Distance to library, (C7) Distance to secondary school, (C8) Distance to primary school, (A1) Vegetation coverage, (A2) Availability of open space, (A3) Availability of water areas, (A4) Distance to recreation facilities, (H1) Distance to hospital, (H2) Distance to manufacturing district, (H3) Air quality, (H4) Drinking water quality, (H5) Soil salinity, (H6) Urban heat island, (S1) Distance to major road intersections, (S2) Distance to police station, (S3) Distance to fire station, (S4) Distance to gas station.

Figure 5.

Average subjective scoring on the indicators of urban livability and their standard deviation: (C1) Distance to city center, (C2) Distance to major road, (C3) Distance to bus terminal, (C4) Distance to train station, (C5) Distance to post office, (C6) Distance to library, (C7) Distance to secondary school, (C8) Distance to primary school, (A1) Vegetation coverage, (A2) Availability of open space, (A3) Availability of water areas, (A4) Distance to recreation facilities, (H1) Distance to hospital, (H2) Distance to manufacturing district, (H3) Air quality, (H4) Drinking water quality, (H5) Soil salinity, (H6) Urban heat island, (S1) Distance to major road intersections, (S2) Distance to police station, (S3) Distance to fire station, (S4) Distance to gas station.

Figure 6.

Aggregated preferences expressed by residents for most livable places to live (endorsement percentages) and geographic distribution of objective livability index.

Figure 6.

Aggregated preferences expressed by residents for most livable places to live (endorsement percentages) and geographic distribution of objective livability index.

Figure 7.

Word cloud of reasons supporting living preferences.

Figure 7.

Word cloud of reasons supporting living preferences.

Figure 8.

Word cloud of reasons for not relocating to favorite living areas.

Figure 8.

Word cloud of reasons for not relocating to favorite living areas.

Table 1.

Dimensions and indicators, relevant literature, and data sources.

Table 1.

Dimensions and indicators, relevant literature, and data sources.

| Dimension |

Indicator |

Measurement Unit |

Data Source |

Note |

Functional Relationship |

Citations |

| Convenience |

Distance to city center |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[3,6,7] |

| Distance to major road |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[32,55] |

| Distance to bus terminal |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[56] |

| Distance to train station |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[56] |

| Distance to post office |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[56] |

| Distance to library |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[6,56] |

| Distance to secondary school |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[6,7,56] |

| Distance to primary school |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[6,7,56] |

| Amenity |

Vegetation coverage |

Index [-1, 1] |

MODIS-Q1 imagery |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) |

Positive |

[7] |

| Availability of open space |

0/1 |

Landsat 8 imagery |

- |

Positive |

[32,57] |

| Availability of water areas |

Index [-1, 1] |

Sentinel-2 imagery |

Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) |

Positive |

[32] |

| Distance to recreation facility |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[3,7] |

| Health |

Distance to hospital |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[3,6,7] |

| Distance to manufacturing district |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Positive |

[3,6,7] |

| Air quality |

Micromoles per 100 m² (µmol/100m²) |

Sentinel-5P imagery |

- |

Positive |

[42,54] |

| Drinking water quality |

Index |

Water Quality Index Data |

Water Quality Index (WQI) |

Positive |

[42,54] |

| Soil salinity |

Index [-1, 1] |

Landsat 8 imagery |

Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI) |

Negative |

[52] |

| Urban heat island |

Degree Celsius |

MODIS-A2 imagery |

Land Surface Temperature |

Negative |

[29] |

| Safety |

Distance to major road intersection |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Positive |

[3,6,7] |

| Distance to police station |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[7,56,57] |

| Distance to fire station |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Negative |

[56] |

| Distance to gas station |

Meter |

KDA |

- |

Positive |

[3] |

Table 2.

Prioritization of dimensions and indicators.

Table 2.

Prioritization of dimensions and indicators.

| Dimension |

Indicator |

Priority

(% in Dimension) |

Rank |

Overall Rank |

| Convenience (60%) |

Distance to city center |

28.52 |

1 |

1 |

| Distance to major road |

22.82 |

2 |

| Distance to bus terminal |

14.16 |

3 |

| Distance to train station |

6.34 |

6 |

| Distance to post office |

1.64 |

8 |

| Distance to library |

3.56 |

7 |

| Distance to secondary school |

9.86 |

5 |

| Distance to primary school |

13.10 |

4 |

Amenity

(6%) |

Vegetation coverage |

52.37 |

1 |

4 |

| Availability of open space |

15.25 |

3 |

| Availability of water areas |

6.09 |

4 |

| Distance to recreation facility |

26.29 |

2 |

Health

(23%) |

Distance to hospital |

24.25 |

2 |

2 |

| Distance to manufacturing district |

17.75 |

3 |

| Air quality |

4.01 |

6 |

| Drinking water quality |

37.91 |

1 |

| Soil salinity |

9.09 |

4 |

| Urban heat island |

6.98 |

5 |

Safety

(12%) |

Distance to major road intersection |

51.43 |

1 |

3 |

| Distance to police station |

30.45 |

2 |

| Distance to fire station |

11.58 |

3 |

| Distance to gas station |

6.54 |

4 |

| Overall Consistency Test: λ max = 4.24; CI = 0.08; RI = 0.9; CR = 0.087 |