Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

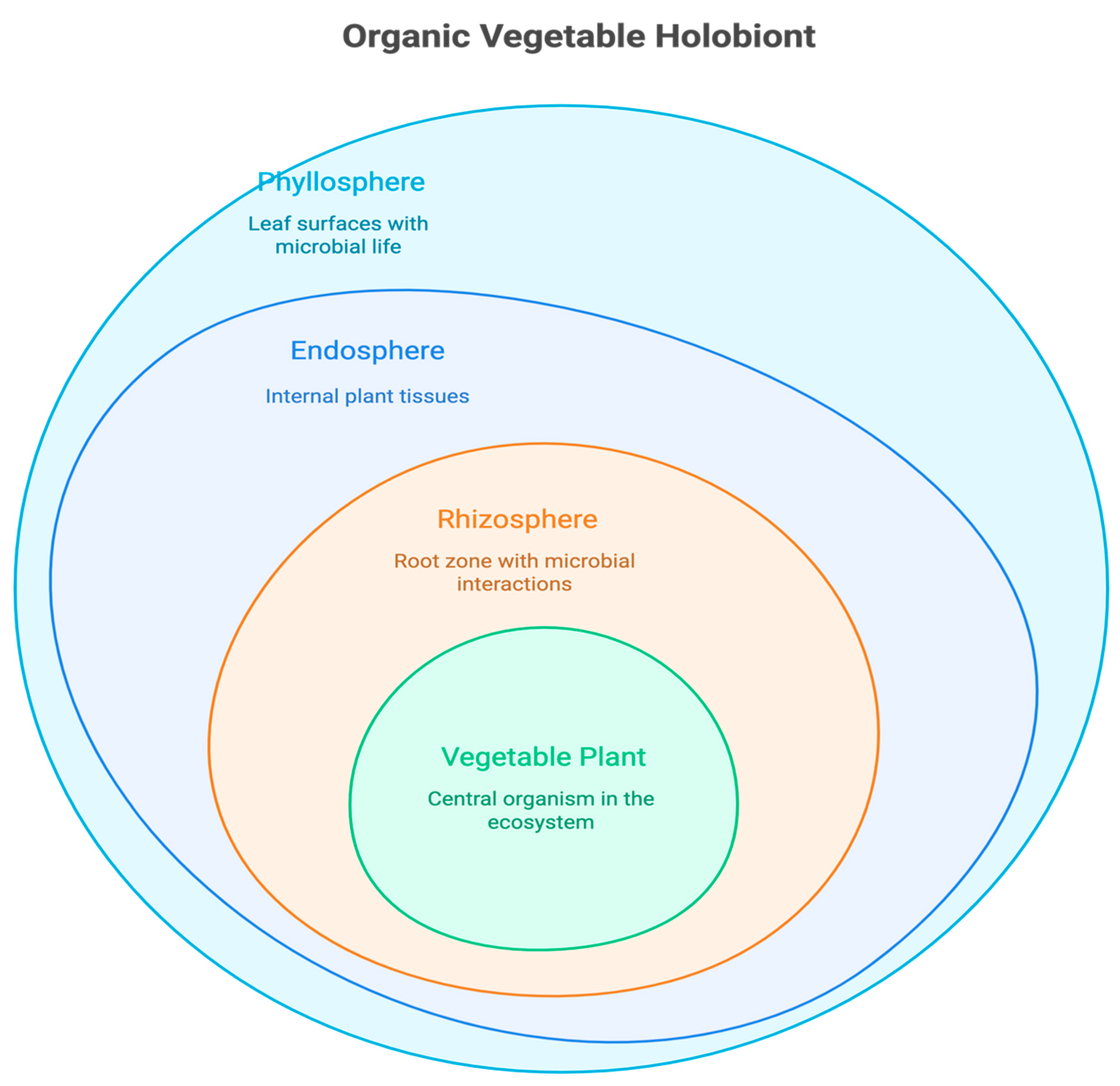

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

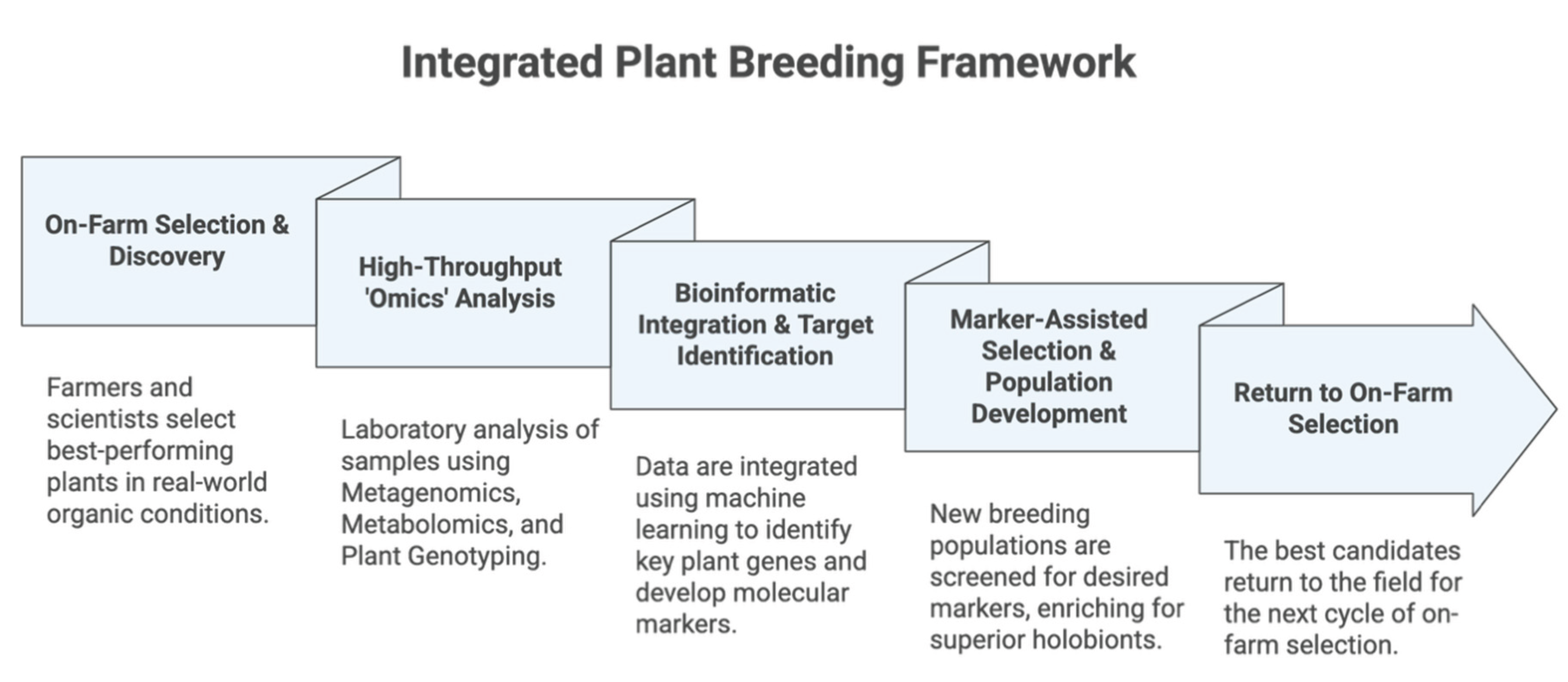

Abstract

Keywords:

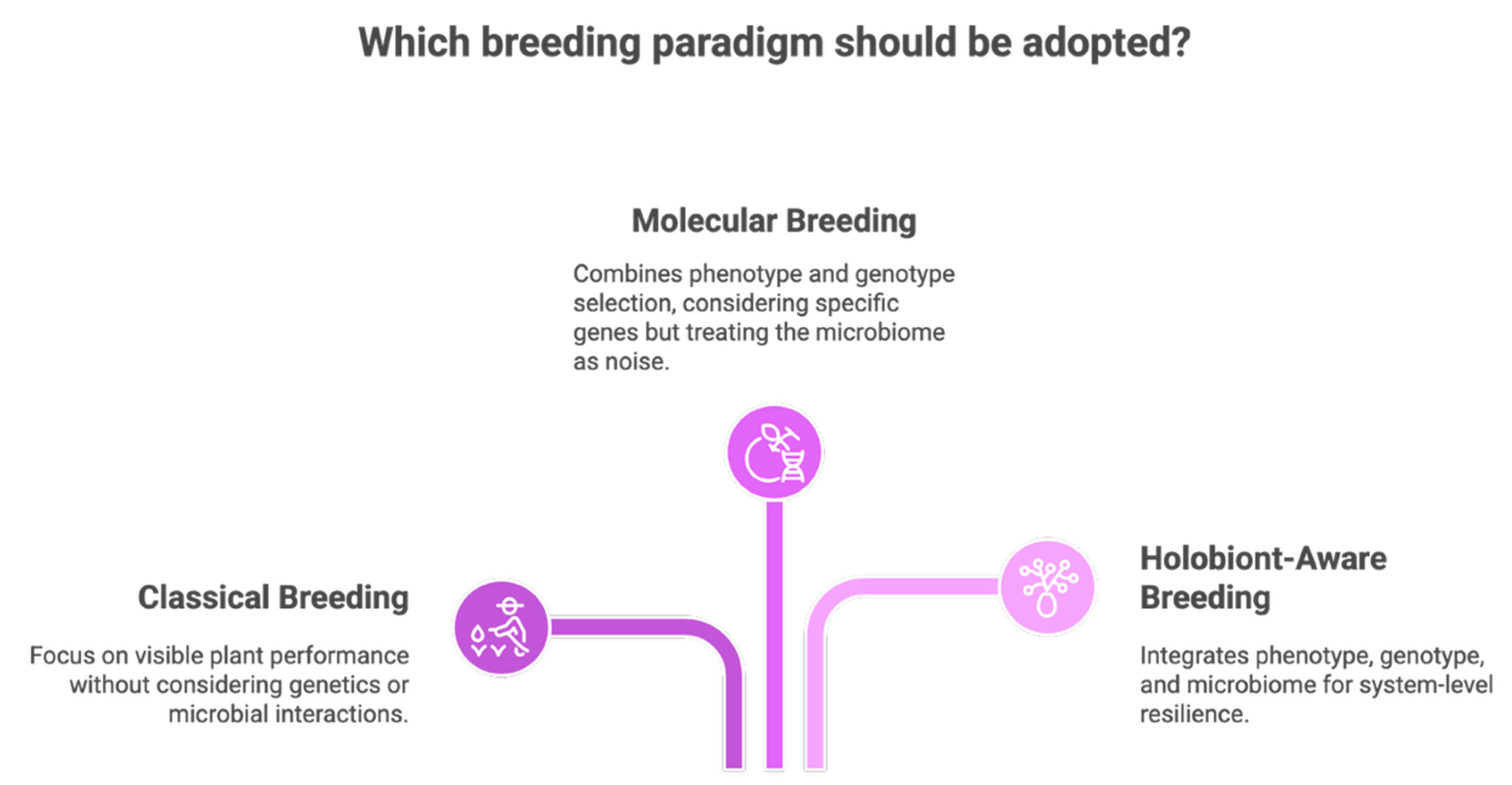

1. Introduction: A Paradigm Shift for Organic Breeding

2. The Organic Agroecosystem as a Unique Selective Environment

3. The Phytobiome: An Untapped Resource for Trait Improvement

4. Root Exudates: The Language of Plant-Microbe Communication

5. A New Breeding Paradigm: Integrating 'Omics' with On-Farm Expertise

6. Challenges and Future Directions

7. Conclusion: Co-Evolving Crops for a Sustainable Future

References

- Alori, E. T., Glick, B. R., & Babalola, O. O. (2017). Microbial phosphorus solubilization and its potential for use in sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 971. [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, A., Trakunjae, C., & Tisa, L. S. (2022). The plant holobiont: the next-generation of agricultural biotechnology. Biotechnology Advances, 54, 107871.

- Berendsen, R. L., Pieterse, C. M., & Bakker, P. A. (2012). The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends in Plant Science, 17(8), 478-486. [CrossRef]

- Bitas, V., Kim, H. S., Chelius, M. K., & Vivanco, J. M. (2013). The rhizosphere microbiome and its potential to enhance plant resistance to pathogens. Plant Disease, 97(3), 292-303.

- Bonfante, P., & Genre, A. (2010). Mechanisms underlying beneficial plant–fungus interactions in mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature Communications, 1(1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D., Schlaeppi, K., Spaepen, S., van Themaat, E. V. L., & Schulze-Lefert, P. (2013). Structure and functions of the bacterial root microbiota. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 64, 325-353.

- Busby, P. E., Svedin, E., Bradford, M. A., Craine, J. M., & Peay, K. G. (2017). Tackling the G x E x M: the importance of the microbiome in breeding for crop resilience. Plant Science, 262, 117-123.

- Ceccarelli, S., Grando, S., & Baum, M. (2007). Participatory plant breeding in water-limited environments. Experimental Agriculture, 43(4), 411-435. [CrossRef]

- Compant, S., van der Heijden, M. G., & Sessitsch, A. (2010). Climate change effects on beneficial plant–microorganism interactions. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 73(2), 197-214. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. C., Murphy, K. M., & Jones, S. S. (2008). Decentralized selection and participatory approaches in plant breeding for low-input systems. Euphytica, 160(2), 143-154. [CrossRef]

- Finkel, O. M., Castrillo, G., Paredes, S. H., Salas González, I., & Dangl, J. L. (2017). Understanding and exploiting plant beneficial microbes. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 38, 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J. A., van der Lelie, D., & Zarraonaindia, I. (2014). Microbial terroir for wine grapes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(1), 5-6. [CrossRef]

- Glick, B. R. (2014). Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiological Research, 169(1), 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Hacquard, S., Garrido-Oter, R., González, A., Spaepen, S., Ackermann, G., Lebeis, S., ... & Schulze-Lefert, P. (2015). Microbiota and host nutrition across plant and animal kingdoms. Cell Host & Microbe, 17(5), 603-616. [CrossRef]

- IFOAM. (2005). The IFOAM Norms for Organic Production and Processing. International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements.

- Jacoby, R., Peukert, M., Succurro, A., Koprivova, A., & Kopriva, S. (2017). The role of soil microorganisms in plant mineral nutrition—current knowledge and future directions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 1617. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, L. M., Trexler, R. V., Malik, A. A., Hockett, K. L., & Bell, T. H. (2019). The inherent conflicts in developing soil microbial inoculants. Trends in Biotechnology, 37(2), 140-151. [CrossRef]

- Kloppenburg, J. R. (2010). Seed sovereignty: the promise of open source biology. Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Knight, R., Vrbanac, A., Taylor, B. C., Aksenov, A., Callewaert, C., Debelius, J., ... & Dorrestein, P. C. (2018). Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(7), 410-422. [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K. B., Othman, R., Abdul Rahim, K., & Shamsuddin, Z. H. (2016). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation to enhance vegetative growth, nitrogen fixation and nitrogen remobilisation of maize under greenhouse conditions. PloS one, 11(3), e0152478. [CrossRef]

- Lammerts van Bueren, E. T., Jones, S. S., Tamm, L., Murphy, K. M., Myers, J. R., Leifert, C., & Messmer, M. M. (2011). The need to breed crop varieties suitable for organic farming, using wheat, tomato and broccoli as examples: a review. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 58(3-4), 193-205. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. X., Qin, Y., & Bai, Y. (2019). Reductionist synthetic community approaches in root microbiome research. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 49, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Lori, M., Symnaczik, S., Mäder, P., De Deyn, G., & Gattinger, A. (2017). Organic farming enhances soil microbial abundance and activity—A meta-analysis and meta-regression. PloS One, 12(7), e0180442. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, G. L., Hamblin, M., & Leff, J. W. (2020). The gut microbiome of wild animals. Science, 367(6482), 1113-1115.

- Lugtenberg, B., & Kamilova, F. (2009). Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology, 63, 541-556.

- Mäder, P., Fließbach, A., Dubois, D., Gunst, L., Fried, P., & Niggli, U. (2002). Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science, 296(5573), 1694-1697. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, U. G., & Sachs, J. L. (2015). Engineering complex mutualisms: the promise of synthetic biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30(11), 637-646.

- Murphy, K. M., Campbell, K. G., Lyon, S. R., & Jones, S. S. (2007). Evidence of varietal adaptation to organic farming systems. Field Crops Research, 102(3), 172-177. [CrossRef]

- O'Malley, M. A. (2015). The hologenome concept: a new view of evolution. BioScience, 65(3), 221-222.

- Palmgren, M. G., Edenbrandt, A. K., Vedel, S. E., Andersen, M. M., Landes, X., Østerberg, J. T., ... & Ammitzbøll, H. (2015). Are we ready for back-to-nature crop breeding? Trends in Plant Science, 20(3), 155-164. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C. M., Zamioudis, C., Berendsen, R. L., Weller, D. M., Van Wees, S. C., & Bakker, P. A. (2014). Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 52, 347-375. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D., Hepperly, P., Hanson, J., Douds, D., & Seidel, R. (2005). Environmental, energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. BioScience, 55(7), 573-582. [CrossRef]

- Ponisio, L. C., M'Gonigle, L. K., Mace, K. C., Palomino, J., de Valpine, P., & Kremen, C. (2015). Diversification practices reduce organic to conventional yield gap. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1799), 20141396. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. (2018). Intensification for redesigned and sustainable food systems. Science, 362(6417), eaav0294.

- Raaijmakers, J. M., Vlami, M., & de Souza, J. T. (2002). Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 81(1-4), 537-547. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. E., Barea, J. M., McNeill, A. M., & Prigent-Combaret, C. (2009). Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant and Soil, 321(1-2), 305-339. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E., & Zilber-Rosenberg, I. (2018). The hologenome concept of evolution, 25 years later. Microbiome, 6(1), 78.

- Sasse, J., Martinoia, E., & Northen, T. (2018). Feed your friends: do plant exudates shape the root microbiome? Trends in Plant Science, 23(1), 25-41. [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J. A. (2012). Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature, 485(7397), 229-232.

- Simon, J. C., Marchesi, J. R., Mougel, C., & Selosse, M. A. (2019). Host-microbiota interactions: from holobiont theory to analysis. Microbiome, 7(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. E., & Read, D. J. (2008). Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Academic press.

- Toju, H., Peay, K. G., Yamamichi, M., Narisawa, K., Hiruma, K., Naito, K., ... & Kiers, E. T. (2018). 'Core microbiomes' for sustainable agroecosystems. Nature Plants, 4(5), 247-257. [CrossRef]

- Tuck, S. L., Winqvist, C., Mota, F., Ahnström, J., Turnbull, L. A., & Bengtsson, J. (2014). Land-use intensity and the effects of organic farming on biodiversity: a hierarchical meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51(3), 746-755. [CrossRef]

- Turner, T. R., James, E. K., & Poole, P. S. (2013). The plant microbiome. Genome Biology, 14(6), 209.

- van der Heijden, M. G., & Hartmann, M. (2016). Networking in the plant microbiome. PLoS Biology, 14(2), e1002378.

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A., & Dufresne, A. (2015). The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytologist, 206(4), 1196-1206. [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F., Sivasithamparam, K., Ghisalberti, E. L., Marra, R., Woo, S. L., & Lorito, M. (2008). Trichoderma–plant–pathogen interactions. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 40(1), 1-10.

- Vurukonda, S. S. K. P., Vardharajula, S., Shrivastava, M., & SkZ, A. (2016). Enhancement of drought stress tolerance in crops by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiological Research, 184, 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J. G., Zhang, X., Beyene, Y., Semagn, K., Olsen, M., Prasanna, B. M., & Buckler, E. S. (2018). The future of agriculture: breeding for resilience. Trends in Genetics, 34(11), 849-852.

- Weller, D. M., Raaijmakers, J. M., Gardener, B. B. M., & Thomashow, L. S. (2002). Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 40(1), 309-348.

- Willer, H., Trávníček, J., Meier, C., & Schlatter, B. (2022). The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2022. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, Frick, and IFOAM – Organics International, Bonn.

- Wolfe, M. S., Baresel, J. P., Desclaux, D., Goldringer, I., Hoad, S., Kovacs, G., ... & Lammerts van Bueren, E. T. (2008). Developments in breeding cereals for organic agriculture. Euphytica, 163(3), 323-346. [CrossRef]

- Wright, D., Scholes, J., & Read, D. (2005). The role of arbuscular mycorrhiza in the growth of a T-DNA mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana deficient in P absorption. Plant, Cell & Environment, 28(7), 879-888.

- Zamioudis, C., & Pieterse, C. M. (2012). Modulation of host immunity by beneficial microbes. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 25(2), 139-150. [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K., Louie, K. B., Hao, Z., Mansoori, N., da Rocha, U. N., Shi, S., ... & Northen, T. R. (2018). Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nature Microbiology, 3(4), 470-480. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).