1. Introduction

In high-altitude regions of the Global South, climate change is intensifying due to extreme seasonal variations [

1,

2,

3], disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations dependent on subsistence economies [

4]. This scenario has prompted research into adaptive thermal comfort models [

5,

6], thermal performance evaluations based on leading global standards such as ASHRAE 55 [

7], ISO 7730 [

8], and UNE-EN 16798-1 [

9], and passive solar heating architecture [

10]. In the Andean mountain range, governmental policies in Argentina (2007) [

11], Chile (2011) [

12], and Peru (2014) [

13] have established regulations to ensure adequate thermal performance in buildings, with a priority on high-altitude constructions exposed to low-temperature winter seasons.

In the Peruvian context, approximately 2.8 million people reside between 3,000 and 5,000 meters above sea level (m a.s.l.) [

14], where the winter season brings periods of frost (heladas) [

15] to the high-Andean regions. These conditions particularly affect the health and well-being of vulnerable indigenous rural populations—including children, the elderly, and young adults—who face acute respiratory infections, subsistence economies, and a low quality of life [

16,

17]. In response, studies on thermal comfort in both vernacular indigenous housing and improved housing modules have been conducted by public [

18,

19] and private [

20,

21,

22] university research programs, as well as by governmental and non-governmental mass-scale initiatives [

23] aimed at mitigating the impact of low indoor temperatures.

A subset of this research has applied thermal transmittance calculations according to the 2014 Peruvian Technical Standard EM.110 to determine indoor thermal conditions in the high-Andean climate zone. One study focused on maximum thermal transmittance limits by assessing typical building envelopes (adobe walls, stone floors, and thatched roofs) [

24], while another explained how low-cost insulation solutions were designed to meet the Peruvian standard’s minimum U-value requirements for the region [

25].

However, since the second decade of the 21st century, the impact of climate change has become more pronounced, with winter temperatures dropping to as low as -21°C in high-Andean zones, according to the National Meteorology and Hydrology Service of Peru [

26]. This situation presents significant challenges for rural life and the well-being of indigenous communities. To address this, the Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Sanitation (MVCS) began implementing the "Sumaq Wasi" (a Quechua term for "Beautiful House") housing modules in 2019 to ensure thermal comfort in environments of high climatic vulnerability [

27], an urgency recognized by a state of emergency declaration in 2022 [

28]. This intervention is part of the National Rural Housing Program, which provides social housing for poor and extremely poor indigenous communities in rural or dispersed settlements [

29]. These modules are designed based on standardized models for regional climate variations but lack community participation toward appropriate ethno-development [

30].

Thermal performance studies on the

Sumaq Wasi modules, specifically focusing on thermal transmittance, have been conducted through undergraduate [

31,

32,

33] and postgraduate theses [

34]. Therefore, understanding the thermal performance of these modules across diverse high-altitude regions is a priority, not only due to the public investment involved but also because it is necessary to verify compliance with the Technical Standard EM.110 "Thermal and Luminous Comfort with Energy Efficiency" (2014) [

13], its 2022 amendment to "Thermal Envelope" [

35], and the 2022 draft version of the same standard [

36].

The EM.110 standard, in both its official and draft versions, establishes the relationship between the building envelope and thermal performance by applying technical design requirements aimed at improving thermal well-being and promoting energy efficiency. This relationship is primarily based on three key aspects: limiting heat transfer (Maximum Thermal Transmittance), preventing moisture issues (Surface Condensation), and controlling heat loss or gain from air movement (Infiltration and Air Permeability).

The present study evaluates the thermal performance of an adobe Sumaq Wasi housing module, analyzing its compliance with the Peruvian Technical Standard EM.110 during the 2023 frost season in Kunturkanki, Cusco. It is hypothesized that the standardized design of this dwelling is insufficient for the climatic demands of the high-Andean zone, resulting in non-compliance with regulatory limits and an inability to achieve recommended thermal comfort ranges. To test this hypothesis, the research pursues two main objectives: (1) to compare the results of thermal transmittance and surface condensation risk calculations by applying the methodologies of the EM.110 standard (2014 version and 2022 draft update), in order to quantify the differences and evaluate the implications of each standard; and (2) to assess whether the resulting thermal performance allows for indoor temperatures to be maintained within the adaptive comfort range, and to benchmark these records against the comfort standards recommended by both regulations for the studied climate zone.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the thermal transmittance values of the building envelope components and the surface condensation risk of a Sumaq Wasi module were calculated using both the 2014 version and the 2022 draft update of the Peruvian standard EM.110. To support these calculations, fieldwork was conducted to document the construction materials of the selected module. During this period, from July 23 to 26, 2023—coinciding with the season of lowest temperatures—indoor and outdoor air temperatures, along with other meteorological variables, were continuously monitored. Subsequently, the collected data were used to assess whether the Sumaq Wasi module maintains indoor air temperatures within the adaptive thermal comfort range.

2.1. Study Area: Kunturkanki District and Sumaq Wasi Module

The research was conducted in the Kunturkanki district, located in the Canas province of Cusco, Peru (latitude: 14.47225° S, longitude: 71.29688° W, altitude: 3958 m a.s.l.) (

Figure 1).

The climate of the Kunturkanki district is characterized by two distinct seasons: a rainy season and a dry season. The dry season (June–August) features the lowest temperatures and experiences cold spells, known locally as heladas (frosts). According to data from the nearest meteorological station (Payapunku, located 4 km away at an altitude of 3982 m a.s.l.), the average air temperature during this period is 6.81 °C, with an average relative humidity of 46.50%. The daily thermal behavior, as illustrated in

Figure 2, exhibits a marked diurnal oscillation. Temperatures drop to their lowest point between midnight and 8:00 a.m., reaching a critical minimum of -4.6 °C between 5:00 and 7:00 a.m. Subsequently, a gradual increase is recorded, culminating in maximum peaks of 17 °C to 19.7 °C in the afternoon (2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.).

The

Sumaq Wasi housing modules are designed as one component of a typical high-Andean rural dwelling, which is often configured with dispersed domestic, productive, and sanitary spatial units (

Figure 3). The specific Sumaq Wasi module studied was built in 2022, has a floor area of 33 m², a ceiling height of 2.12 meters, and comprises three spaces: two bedrooms and a dining area (

Figure 4). Its building envelope is primarily constructed with adobe blocks, a concrete floor, and a roof made of zinc corrugated sheets with an expanded polystyrene (EPS) board (

Table 1). During the site visit, it was verified that the dwelling's construction corresponds to the information provided in the government's technical documents.

During the fieldwork, indoor and outdoor temperatures, as well as relative humidity, were measured using ELITECH RC-4HC hygrothermal data loggers. Sensors were installed both inside and outside the dwelling. The measurements were recorded over three consecutive days, from July 23 to 26, 2023, at 15-minute intervals. The monitoring was conducted under unoccupied conditions with all doors and windows closed.

2.2. Assessment of Thermal Transmittance and Surface Condensation according to Standard EM.110-2014 and the Draft Update EM.110-2022

2.3.1. Evaluation of Thermal Transmittance (U-value)

The calculation of thermal transmittance (U-value) was performed following the procedures established in both the Technical Standard EM.110 (2014) and its draft update (2022). The process began with the classification of the site into its corresponding bioclimatic zone: 'High-Andean' for the 2014 standard and 'Very Cold Continental' for the 2022 draft. Subsequently, each component of the building envelope (wall, roof, and floor) was analyzed, assigning the values for internal surface resistance (Rsi) and external surface resistance (Rse) as stipulated by each regulation. The U-value of each element was determined by calculating the reciprocal of its total thermal resistance. A weighted average U-value was then obtained for each assembly and compared against the maximum allowable limits. The final values obtained for each methodology must not exceed the limits specified for each bioclimatic zone according to the selected standard (

Table 2).

A lthough the general procedure is similar, the two standards present substantial methodological differences that influence the results. The 2022 draft update introduces a higher level of detail by requiring a differentiated calculation for heterogeneous elements, including both horizontal and vertical heat flows, in contrast to the more simplified approach of the 2014 version. Furthermore, the 2022 version eliminates the exclusion of surface resistances for thermal bridges (e.g., beams, columns) and mandates a specific calculation for openings, as opposed to the tabulated values used in the previous standard. Finally, the approach for the floor assembly changes radically: the 2014 standard requires a calculation based on the material layers, whereas the 2022 draft assigns a predetermined U-value based on the type of perimeter insulation (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

To perform the calculations for this study, information was gathered from both technical documents and a site visit, during which building materials were observed (Figure 8) and data loggers were installed. Subsequently, a matrix was developed to group each building component by its envelope assembly and its interaction with the surrounding environment, aligning with the requirements of each methodology. Field data, such as the layer composition of each building component (

Figure 7), material thickness, and exposed area, were also collected. The thermal conductivity coefficients for the materials were obtained from the current EM.110 standard.

2.3.2. Verification of Surface Condensation Risk

To prevent the degradation of building components due to moisture from condensation, it must be ensured that the internal surface temperature (Tsi) of each element is higher than the dew point temperature (Tr) (Tsi > Tr). This requirement is mandatory for heated buildings in any bioclimatic zone.

The verification was performed following the "Methodology for the Calculation of Surface Condensation Risk" (Annex No. 4 in the 2014 standard[

13]; Annex IV in the 2022 draft [

36]), which references the IRAM 11630 standard [

39]. This method consists of two main calculations:

1. Internal Surface Temperature (Tsi): This was calculated for each envelope assembly using the formula Tsi = Ti − (Rsi × (Ti − Te) / Rt). The methodological differences between the two Peruvian standards lie in the input values for this formula: both the internal surface resistance (Rsi) and the total thermal resistance (Rt) of each element vary, as the latter is a result of the previously described thermal transmittance calculation.

2. Dew Point Temperature (Tr): This was determined from the design indoor temperature (Ti) and the design indoor relative humidity (HRi) stipulated for the bioclimatic zone, using a psychrometric chart.

Compliance is confirmed if the calculated Tsi for each component consistently exceeds the determined Tr (see

Figure 8).

2.3. Modelo Evaluación del Confort Térmico Adaptativo

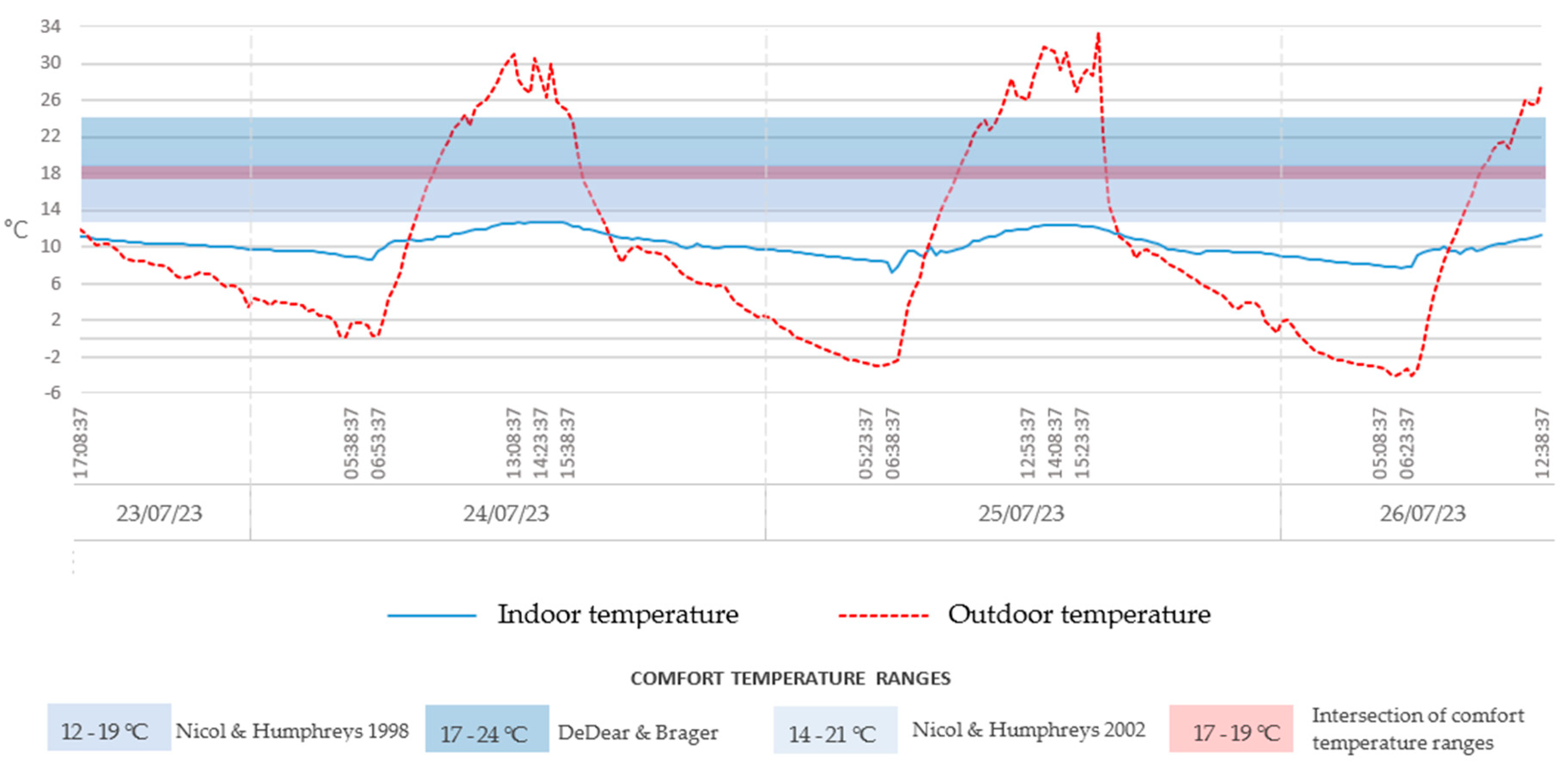

The assessment of thermal comfort was based on recognized adaptive models, such as those developed by de Dear and Brager (1998) and Nicol and Humphreys (1998, 2002) [

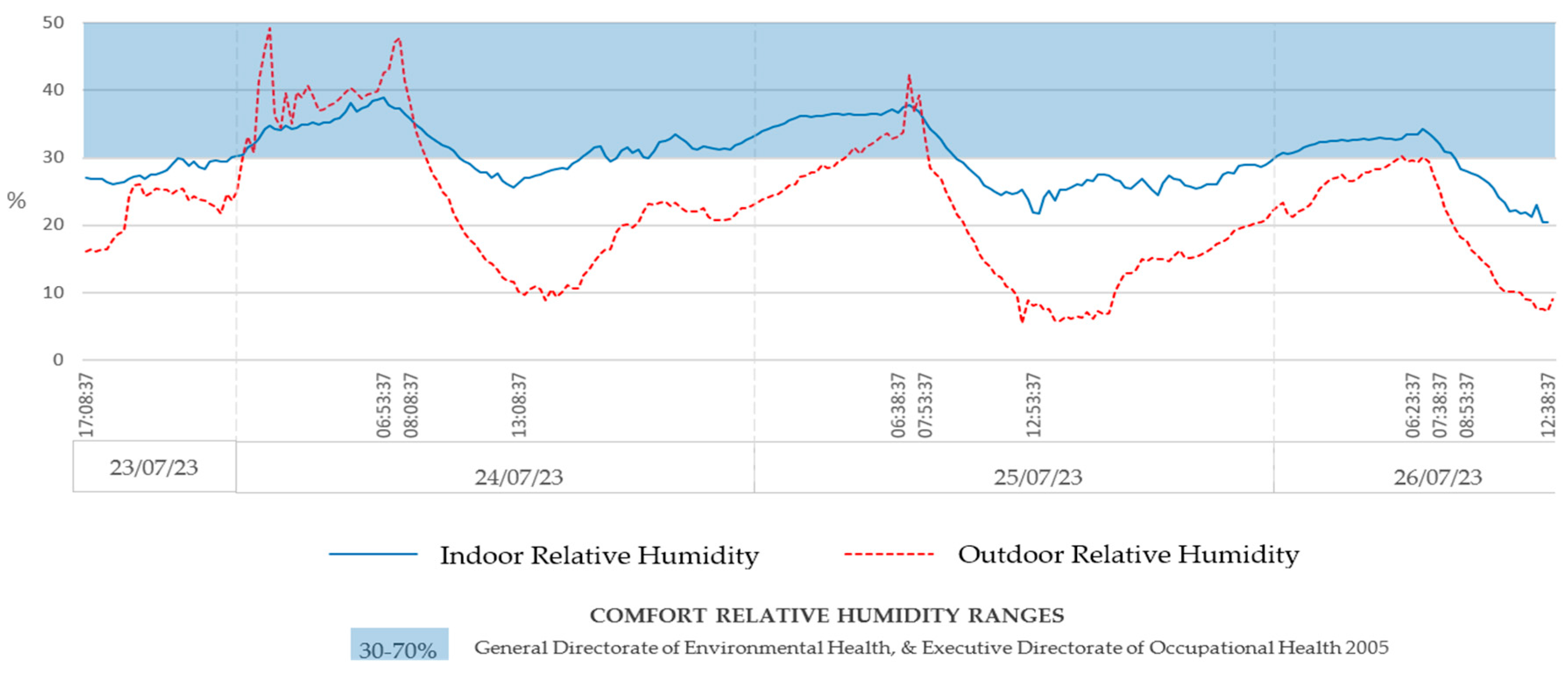

21] . The model inputs utilized the outdoor temperature conditions during the frost season (June, July, and August) obtained from the nearest meteorological station (Payapunku). A satisfaction criterion for 80% of occupants was established, which corresponds to an acceptable comfort range of ±3.45 °C from the neutral temperature. Based on these models, to achieve thermal well-being for 80% of users in the relevant bioclimatic zone, indoor temperatures should be maintained between 12 °C and 24 °C, with a more convergent optimal range of 17 °C to 19 °C during the frost season. For additional context, the current Occupational Health manual in Peru specifies an optimal effective temperature in winter ranging from 17 °C to 22 °C, with comfort zones located between 30% and 70% relative humidity (RH) [

38].

3. Results

The results of the thermal performance assessment of the adobe-built Sumaq Wasi housing module, which include analyses of thermal transmittance, surface condensation risk, and adaptive thermal comfort, indicate a notable non-compliance with Peruvian regulations and an inability to ensure thermally comfortable conditions for its occupants.

3.1. Thermal Transmittance (U-value)

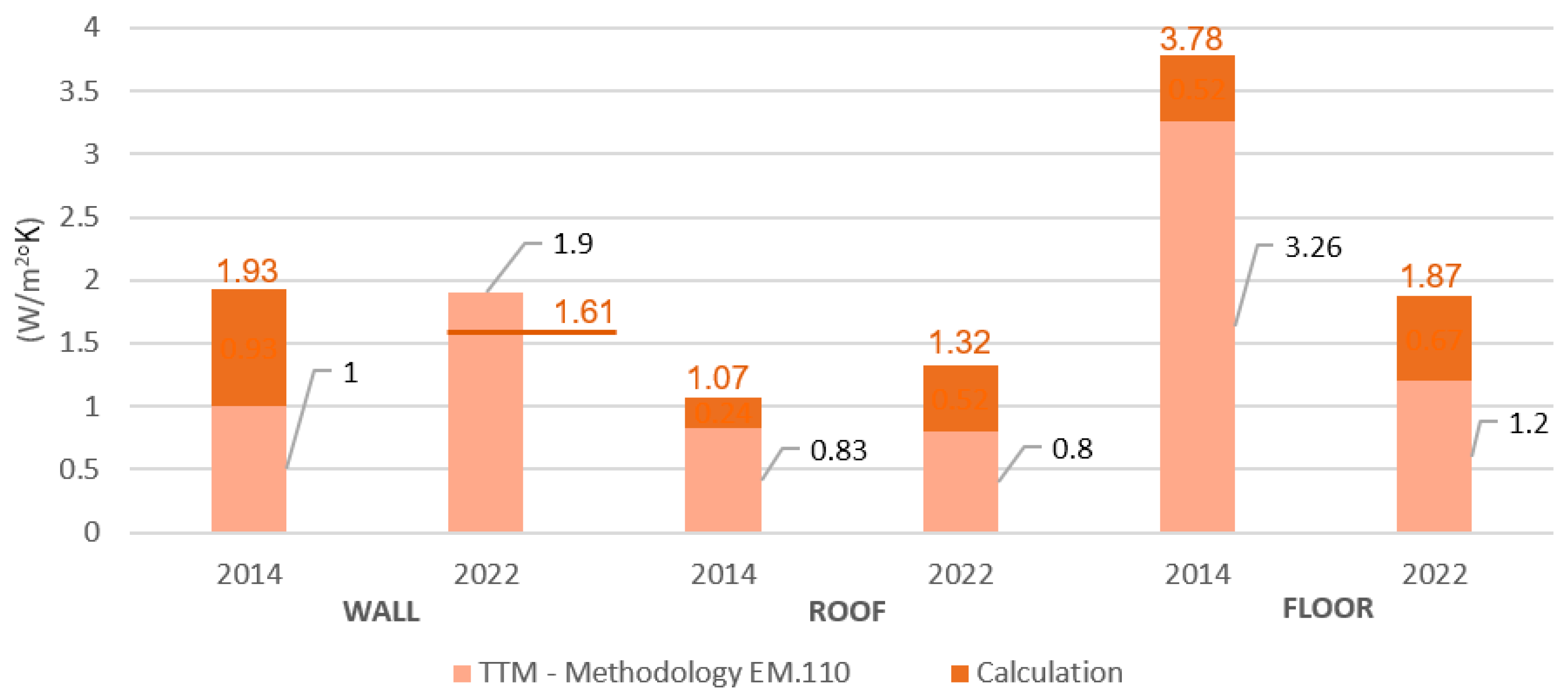

The thermal transmittance calculations reveal deficient insulation in most of the building envelope. The wall, with a U-value of 1.93 W/m²K, exceeds the limit of the 2014 standard (1.00 W/m²K), although its recalculated value under the 2022 draft update (1.61 W/m²K) does meet the more flexible threshold of 1.90 W/m²K. However, both the roof and the floor fail under both assessments. The roof significantly exceeds the limits for both 2014 (1.07 vs. 0.83 W/m²K) and 2022 (1.32 vs. 0.80 W/m²K). Similarly, the floor surpasses the corresponding thresholds with values of 3.78 vs. 3.26 W/m²K (2014) and 1.87 vs. 1.20 W/m²K (2022) (see

Figure 9).

3.2. Surface Condensation Risk

3.2.1. Calculation of Dew Point Temperature (Tr)

Using field data, the dew point temperature (Tr) was determined. Considering the minimum recorded indoor temperature of 7.30 °C (

Table 3 and Figure 11) and its corresponding indoor relative humidity of 36.7%, the resulting Tr was -6.70 °C.

3.2.2. Calculation of Internal Surface Temperature (Tsi)

The internal surface temperature (Tsi) was calculated for each envelope assembly based on the formulas presented in the methodology section. The key input values, which differ between the two standards, were as follows:

- -

EM. 110 - 2014: The internal surface resistance (Rsi) was set at 0.11 m²K/W for the wall and 0.09 m²K/W for the roof and floor.

- -

EM. 110 - 2022: The Rsi values were obtained from Table 5 of the draft standard, establishing 0.13 m²K/W for the wall, 0.10 m²K/W for the roof, and 0.17 m²K/W for the floor.

The most critical recorded field data were used for the indoor (Ti) and outdoor (Te) temperatures, which were 7.30 °C and -3.00 °C, respectively (

Table 4). The total thermal resistance (Rt) for each assembly was derived from the previously calculated thermal transmittance values.

Under both methodologies, the calculated Tsi values for each envelope assembly were higher than the dew point temperature (Tr). Although the Tsi values differed slightly between the two standards, both scenarios indicated that the risk of surface condensation was avoided (

Table 4).

3.3. Adaptive Thermal Comfort Assessment

The collected data show that the adobe housing module fails to reach the target comfort temperature range of 17–19 °C at any point during the day. Instead, it recorded average indoor temperatures between 8.7 °C and 11.4 °C during the occupants' resting hours (17:00 to 05:00) (

Figure 10). Regarding indoor relative humidity, the module was partially within the comfort limits, with average values ranging from 26.7% to 37.8% during the hours of greatest use (

Figure 11).

4. Discussion

The findings on the thermal performance of the adobe Sumaq Wasi module indicate a significant discrepancy with the requirements of the Peruvian regulations, as well as the dwelling's limited capacity to maintain comfortable conditions for its occupants.

The thermal transmittance analysis shows that the main components of the building envelope—the wall, roof, and floor—exceed the maximum allowable values stipulated by the 2014 standard's methodology. This trend continues under the 2022 draft methodology, with the sole exception of the wall assembly.

Regarding the results for the wall, the value obtained using the 2014 standard's methodology is 1.93 W/m²K, compared to the 1.088 W/m²K value of a typical adobe wall [

21]. Although this value does not meet the strict limit of the 2014 standard (1.00 W/m²K), it does comply with the more flexible criterion of the 2022 draft update (1.90 W/m²K), with a calculated value of 1.61 W/m²K. This finding contrasts with optimized bioclimatic prototypes, such as the one in the locality of Orduña at an altitude of 4670 meters, which achieved an excellent performance of 0.667 W/m²K using adobe and totora reeds, demonstrating that it is feasible to achieve high thermal performance [

21].

For the roof, the results under both the 2014 methodology (1.07 W/m²K) and the 2022 draft update (1.32 W/m²K) are similarly consistent with findings from a study in the Colca Valley at an altitude of 4200 meters (1.80 W/m²K without insulation) [

24]. All these values significantly exceed the high-Andean regulatory limit (0.83 W/m²K), identifying the roof as the most critical point of heat loss. This poor performance is primarily attributed to the use of corrugated zinc sheets (calamina) without adequate insulation. Even improved prototypes, such as the one in Orduña, which reached 0.916 W/m²K, still fail to meet the standard, underscoring the technical challenge of insulating roofs in this region [

21].

For the floor, the value under the 2014 standard (3.78 W/m²K) exceeds the limit of 3.26 W/m²K, and the value under the 2022 draft (1.87 W/m²K) surpasses the threshold of 1.20 W/m²K. This result is comparable to that of the brick Sumaq Wasi module, which recorded 3.417 W/m²K due to its polished cement floor, and it contrasts with more efficient solutions that use wood or air chambers [

31,

32,

33,

34]. However, it is crucial to interpret this finding with caution. Previous research warns that excessive insulation could be counterproductive, as a poorly insulated floor can leverage the thermal inertia of the ground (16–18 °C) as a passive heat source—a benefit that would be nullified by complete insulation [

24].

Regarding the risk of surface condensation, the results indicate that it is not present under either the 2014 or 2022 methodologies, as the internal surface temperature (Tsi) of the envelope components always remained above the dew point temperature (-6.70 °C). This finding is explained by the region's climatic conditions. The critical outdoor temperature recorded (-3.00 °C) is consistent with typical frosts in the southern high-Andes [

20,

21]. Simultaneously, the indoor relative humidity (36.7%) is low, a characteristic of the dry, high-altitude climate, as corroborated by studies in Imata (RH < 40%) and Uro (winter RH of 27.16%) [

16,

22]. However, moisture can lead to the biodeterioration of building materials, a recurring problem in rural dwellings [

23].

Regarding indoor relative humidity, this study reported a range between 26.7% and 37.8%, values that are situated at the lower end of the comfort ranges proposed for the zone (31.1%–61.3%) [

16]. Although temperature is the most critical factor in dry climates, maintaining humidity within healthy limits is fundamental for preventing respiratory ailments [

17].

For adaptive comfort, the results of this study show that in the housing module, indoor temperatures during early morning resting hours oscillate between 8.7 °C and 11.4 °C at an altitude of 3958 meters, compared to the 18 °C established by the 2014 standard for housing. A similar situation is found in studies that applied the adaptive thermal comfort model in Orduña, establishing ranges of 8 °C to 10 °C at 4260 meters during the early morning [

21]. In Imata, a restricted comfort zone between 9.5 °C and 15.3 °C was proposed at 4500 meters [

16], while in Langui, a comfort range between 11.4 °C and 18.4 °C was established at 3969 meters [

25]. Given this reality, the literature suggests that high-Andean inhabitants are acclimatized to lower indoor temperatures than those prescribed by international standards. The comfort ranges obtained in this study oscillate between 17 °C and 19 °C for Kunturkanki, located at an altitude of 3958 meters. This indicates that while the Sumaq Wasi module does not meet an ideal standard, its thermal performance is comparable to that of other construction solutions adapted to the high-Andean environment [

16,

21].

Furthermore, the comparative application of the EM.110 standard (2014) and its 2022 draft update not only reveals numerical differences in the results but also exposes a clear evolution in the approach to thermal assessment in Peru. The 2022 proposal represents a leap toward a more technically rigorous standard, aligned with international practices such as the ISO 13370 and 13789 standards [

39,

40]. This is evidenced by the requirement for specific calculations for openings, the differentiated treatment of heterogeneous elements, and the inclusion of horizontal and vertical heat flows. While the 2014 standard offers a more simplified method, the 2022 version acknowledges the contribution of all components to the total heat flow, which justifies the discrepancies observed in this study and underscores the need for methodologies that more faithfully capture actual thermal performance.

Particularly revealing is the change in approach for the floor envelope. The 2022 draft, by prioritizing perimeter insulation over the composition of layers, recognizes a more sophisticated design strategy. However, this advancement introduces an apparent contradiction: while the standard becomes more stringent by drastically reducing the U-value limit from 3.26 to 1.20 W/m²K, it could also incentivize over-insulation. As previous research warns, this practice would nullify the passive benefit of the ground's thermal inertia, which acts as a natural heat source [

24]. This tension between strict regulatory compliance and the utilization of passive bioclimatic strategies is one of the most important methodological implications arising from this analysis.

Future studies should conduct more fieldwork and parametric simulations in the high-Andean context to quantify the actual contribution of the ground's thermal inertia to comfort and energy demand. Furthermore, an optimal range of thermal transmittance for floors should be determined to balance insulation against heat loss with the harnessing of passive geothermal heat. These findings would be crucial for refining regulations and design guides, ensuring they promote solutions that are genuinely adapted to the local climate and resources.

In light of these findings, it is recommended that improvements to the Sumaq Wasi module focus on roof insulation, as it is the most critical point of heat loss. The incorporation of low-cost, locally available insulating materials, such as straw, could significantly reduce thermal transmittance without a major increase in cost. For the floor, a balanced approach is suggested that improves airtightness to prevent cold air infiltration but does not completely isolate the ground, in order to continue leveraging its thermal inertia. Finally, it is necessary for future social housing policies in high-Andean zones to adopt regulatory limits and comfort ranges that are adapted to the climatic and cultural reality of the region, prioritizing bioclimatic and passive construction solutions.

5. Conclusions

The thermal performance assessment of the Sumaq Wasi housing module in Kunturkanki, at an altitude of 3958 meters, reveals a notable non-compliance with Peruvian regulations and a limited capacity to ensure comfortable conditions for its occupants. The thermal transmittance analysis demonstrates that the envelope does not meet the requirements of either the 2014 or 2022 standards, identifying the roof as the most critical point of heat loss. Despite this, the risk of surface condensation is low due to the scarce humidity of the high-Andean climate. In terms of habitability, while the dwelling does not meet conventional comfort standards, its nighttime performance (8.7 °C–11.4 °C) is comparable to that of other solutions adapted to the Andean environment, which reinforces the need to adjust comfort models to local realities.

The main contribution of this research lies in the identification of a critical methodological tension within the most recent thermal regulation. While the 2022 proposal advances toward greater technical rigor, its prescriptive approach to floor insulation—by drastically reducing the U-value limit—could incentivize over-insulation solutions that nullify the passive benefit of the ground's thermal inertia. This finding underscores the need for future housing policies and regulations not only to pursue compliance with strict thresholds but also to promote intelligent bioclimatic design, balancing technical calculations with passive strategies adapted to the local context to ensure true energy efficiency and comfort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.-O., M.A.-P. and V.S.-V.; methodology, M.A.-P. V.S.-V., and E.M.-S.; investigation, M.A.-P. and V.S.-V.; resources, E.P.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-P. and V.S.-V.; writing—review and editing, E.P.-O., M.A.-P., V.S.-V., E.M.-S. and E.G.-R.; supervision, E.P.-O. and E.G.-R.; project administration, E.P.-O.; funding acquisition, E.P.-O. and E.G.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Perú, grant number N° 010-2021-UNSAAC and The APC was funded by convocatoria esquema financiero E041-2020-01 denominado proyectos de investigación “Programa Yachayninchis Wiñarinanpaq-UNSAAC”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Manus AI for the purposes of improving the writing and fluency of texts and Notebook LM to have a better management of sources. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UNSAAC |

Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco |

| MVCS |

Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento |

| SENAMHI |

Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología |

References

- R. J. Fuller, A. Zahnd, and S. Thakuri, “Improving comfort levels in a traditional high altitude Nepali house,” Building and Environment, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 479–489, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma et al., “Evaluating the Microclimatic Performance of Elevated Open Spaces for Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Cold Climate Zones,” Buildings, vol. 15, no. 15, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Thapa, “Thermal comfort in high altitude Himalayan residential houses in Darjeeling, India – An adaptive approach,” Indoor and Built Environment, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 84–100, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. , C. Y. , Y. S. , D. C. , & L. Y. Yuan, “Research on the thermal comfort of the elderly in rural areas of cold climate, China,” Advances in Building Energy Research, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 612–642, 2022.

- R. ; B. G. De Dear, “Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference,” ASHRAE Transacciones, vol. 104 (1), p. 145-167, 1998.

- I., & B. E. E. Lourenço Niza, “Development of thermal comfort models over the past years: a systematic literature review,” International Journal of Ambient Energy, vol. 43, no. (1), pp. 8830–8846, 2022.

- ASHRAE 55, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions For Human Occupancy, vol. GAJ0392. 2020.

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 7730., Ergonomics of the thermal environment — Analytical determination and interpretation of thermal comfort using calculation of the PMV and PPD indices and local thermal comfort criteria. 2005.

- UNE-EN 16798-1, Energy performance of buildings - Ventilation for buildings - Part 1: Indoor environmental input parameters for design and assessment of energy performance of buildings addressing indoor air quality, thermal environment, lighting and acoustics - Module M1-6. 2020.

- S. Uniyal et al., “Passive solar heated buildings for enhancing sustainability in the Indian Himalayas,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 200, p. 114586, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Graziani, “NORMAS IRAM SOBRE AISLAMIENTO NORMAS IRAM SOBRE AISLAMIENTO TÉRMICO DE EDIFICIOS TÉRMICO DE EDIFICIOS.”.

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, REGLAMENTACION TERMICA MINVU ORDENANZA GENERAL DE URBANISMO Y CONSTRUCCIONES. 2006. [Online]. Available: www.mart.cl.

- Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones, Norma Em-110 Confort Térmico y Lumínico con Eficiencia Energética. Perú, 2014. Accessed: Mar. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.construccion.org/normas/rne2012/rne2006.htm.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. INEI, “Censos Nacionales 2017: XII de Población, VII de Vivienda y III de Comunidades Indígenas,” Lima, Perú, 2017.

- SENAMHI, “Datos Hidrometeorológicos a nivel nacional,” SENAMHI. Accessed: Aug. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=estaciones.

- J. R. Molina, G. Lefebvre, and M. M. Gómez, “Study of the thermal comfort and the energy required to achieve it for housing modules in the environment of a high Andean rural area in Peru,” Energy Build, vol. 281, p. 112757, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Wieser, A. Garaycochea, and V. Prada, “IMPROVING THE THERMAL PERFORMANCE OF SCHOOLS IN THE HIGH ANDEAN REGION OF PERU. THE CASE OF ‘PRONIED’S PREFABRICATED FROST-TYPE MODULAR CLASSROOMS,’” Habitat Sustentable, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 56–67, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Espinoza, J. Molina, M. Horn, and M. M. Gómez, “CONCEPTOS BIOCLIMÁTICOS Y SU APLICABILIDAD A LA ZONA RURAL ALTOANDINA: CASO COMUNIDAD SAN FRANCISCO DE RAYMINA (SFR)-AYACUCHO BIOCLIMATIC CONCEPTS AND THEIR APPLICABILITY TO ANDEAN RURAL AREA: SAN FRANCISCO DE RAYMINA COMMUNITY (SFR) CASE-AYACUCHO,” Revista Tecnia, 2015.

- J. Molina, G. Lefebvre, R. Espinoza, M. Horn, and M. Gómez, “Bioclimatic approach for rural dwellings in the cold, high Andean region: A case study of a Peruvian house,” Energy Build, vol. 231, Jan. 2021.

- C. Moncloa, “Confort Térmico: Un sistema aislante para la vivienda alto andina fabricado con materiales reciclados,” Módulo Arquitectura-CUC, vol. 18 (1), pp. 73–90, 2017.

- M. Wieser, S. Rodriguez, and S. Onnis, “Estrategias bioclimáticas para clima frío tropical de altura. Validación de prototipo en Orduña, Puno, Perú.,” Estoa N°19, vol. 10, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Joará. ; H. S. C. H. A. L. Pari, “Percepción térmica de usuarios en la vivienda vernácula de la comunidad Uro del Lago Titicaca en Perú,” Revista Hábitat Sustentable, vol. 14,1, pp. 22–33, 2021.

- J. R. Molina, J. O. Molina, M. J. Piñas, M. Horn, and M. Gómez, “High Andean bioclimatic dwellings in Peru: climatic conditions, vulnerability of the population and review of academic studies and massification programmes,” Jul. 01, 2025, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- C. Iruri, P. Domínguez, and F. Celis, “Envelope improvements for thermal behavior of rural houses in the Colca Valley, Perú,” Estoa, vol. 12, no. 23, pp. 113–124, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Mejia-Solis, J. Arias, and B. Palm, “Simple solutions for improving thermal comfort in huts in the highlands of Peru,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú, “Aviso meteorológico: Heladas y friaje en la sierra sur del Perú,” Portal web SENAMHI. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/main.php?dp=cusco&p=estaciones.

- Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural, “Información Institucional,” Plataforma digital única del Estado Peruano. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pnvr/institucional.

- Centro de Operaciones de Emergencia Nacional and Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil, “INFORME DE EMERGENCIA N° 988 - 2/7/2022 / COEN - INDECI / 23:40 HORAS (Informe N° 1),” Perú, Jul. 2022. Accessed: Apr. 17, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://portal.indeci.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/INFORME-DE-EMERGENCIA-N%C2%BA-988-2JUL2022-BAJAS-TEMPERATURAS-EN-EL-DEPARTAMENTO-DE-CUSCO-1-2.pdf.

- C. y S. Ministerio de Vivienda, “Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural.” Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pnvr/institucional.

- V. M. Salas Velásquez, “Assisted ethnodevelopment? The case of housing in peasant communities in the Peruvian Andes.” [Online]. Available: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6501-787X.

- F. Huamani, Y. Taipe, and J. Ugarte, “Análisis del confort térmico en las viviendas ‘Sumaq Wasi’, Misquipata, distrito de San Juan de Jarpa, provincia Chupaca, región Junín,” Tesis para optar el Título Profesional de Arquitecta, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, 2021.

- P. Herencia and P. Palomino, “EVALUACIÓN COMPARATIVA DE LOS VALORES DE TRANSMITANCIAS TÉRMICAS DE LOS MÓDULOS SUMAQ WASI EN CCATCCA-QUISPICANCHI, SEGÚN LA NORMA EM.110,” Universidad Andina del Cusco, Cusco, 2023. Accessed: Jul. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12557/5544.

- F. Pacha, “Evaluación del confort térmico en las viviendas rurales Sumaq Wasi en los centros poblados de Pucri y Challamayo pata, Tiquillaca, Puno - 2023.,” Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, Puno, Tiquillaca, Puno, 2024.

- J. Rabanal, “Análisis del desempeño térmico y de la percepción del confort en los Módulos Habitacionales Sumaq Wasi del Centro poblado Chuna, distrito de Chavín de Huántar,” Universidad Pontificia Católica del Perú, 2025.

- Decreto Supremo N°001-2022-Vivienda, Decreto supremo que modifica la denominación de la Norma Técnica EM.110, Confort térmico y lumínico con eficiencia energética y la incorpora en el índice del Reglamento nacional de edificaciones, aprobado por el Decreto Supremo N° 015-2004-Vivienda. 2022.

- C. y S. Ministerio de Vivienda, Proyecto Norma Técnica EM.110, Envolvente Térmica del Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones. Lima, Perú: Diario Oficial El Peruano, 2022. Accessed: Mar. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/vivienda/normas-legales/3302388-197-2022-vivienda/.

- Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural, Especificaciones Técnicas Adobe 25.09. Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento, 2020.

- Dirección General de Salud Ambiental and Dirección Ejecutiva de Salud Ocupacional, Manual de Salud Ocupacional. Lima: PERUGRAF IMPRESORES, 2005.

- International Organization for Standardization, ISO 13370. Thermal performance of buildings — Heat transfer via the ground — Calculation methods. https://www.iso.org/standard/65716.html, 2017.

- International Organization for Standardization., ISO 13789. Thermal performance of buildings — Transmission and ventilation heat transfer coefficients — Calculation method. https://www.iso.org/standard/65713.html, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).