1. Introduction

Comfort in urban public spaces is a key indicator of the overall quality of life in cities and serves as a critical factor in assessing the effectiveness and appeal of public spaces [

1,

2]. High levels of comfort directly reflect the success of urban design, influencing how people engage with and experience their environment. Consequently, it plays a dominant role in the evaluation of public space quality, shaping perceptions of urban livability and community well-being [

3]. Urban well-being and health are closely linked to outdoor activity, which provides significant social and economic benefits to cities [

4,

5]. To promote outdoor activities, public spaces should be attractively designed, with thermal comfort being a key factor in ensuring their usability[

6]. The degree of comfort that people feel in public areas impacts their usage patterns and their perception of the quality of urban spaces [

7,

8]. Concerning climate change, a variety of biometeorology studies have explored how urban climates vary spatially, with a primary focus on thermal comfort. Recent years have seen a marked surge in interest within this research domain, as reflected by a substantial increase in related scholarly publications [

9]. Thermal comfort is typically assessed through thermal indices, though not all of the 165 proposed indices are suitable for outdoor environments, as some overlook essential factors like solar radiation and wind speed [

6].

In addition to environmental factors, human-related aspects such as activity levels and clothing insulation—which influences resistance to heat exchange—also contribute to thermal comfort. Together, these six factors are known as the "six basic parameters" that shape an individual's thermal environment [

10,

11]. Thermal sensation, or how a person feels in a particular thermal setting, is largely psychological and cannot be directly measured through physical or physiological terms alone [

12]. A commonly used method for evaluating thermal environments is the application of thermal indices, although the term "thermal index" is rarely explicitly defined in academic literature [

6,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The heat index and analogous metrics have been criticized for their restricted generalizability. These indices often depend on "ideal" conditions and overlook contextual variables, as well as disregarding the psychological and behavioral factors that influence individual comfort. Thermal stress, on the other hand, quantifies the effect of the six basic parameters on the human body by assessing the thermal strain experienced [

9]. This process is also influenced by physiological factors such as gender, age, and acclimatization. Studies show however that especially age plays a significant role in thermal comfort variations [

17,

18].

Studies centered on age differences substantiate the notion that older adults are notably more vulnerable to heat-related stress. This is largely due to age-related declines in thermoregulatory capabilities, such as reduced sweat response and compromised vasodilation [

19,

20]. The research further highlights that older individuals correctly perceive their heightened risk of heat but often face barriers to adaptive action [

21]. Children, contrastingly, showed no marked differences in subjective thermal perception compared to adults, even though their physiological susceptibility to extreme temperatures is acknowledged [

22]. Overall, the data conforms to the consensus that age is a critical factor in determining thermal comfort and physiological resilience, especially under heatwave conditions [

17].

The studies focusing on gender differences in thermal sensations and comfort generally found minimal significant differences between men and women. The variations observed in some contexts were attributed more to physiological responses rather than a distinct difference in perceived comfort [

23]. Another important finding was that while older women showed slightly higher vulnerability to heat stress, direct thermal perception differences were not substantiated extensively [

24]. Overall, the research challenges traditional assumptions about gender-based thermal comfort, indicating that perceived comfort is more closely aligned with individual and circumstantial factors than gender [

19].

Outdoor thermal environments, in comparison to controlled indoor settings, show greater variability in environmental conditions [

25]. Dynamic and non-uniform microclimatic conditions in public spaces can lead to an imbalance in the heat exchange between the human body and its environment [

9,

26]. The most common urban activities in outdoor spaces—such as standing and walking—are important considerations when assessing outdoor thermal comfort [

27]. Additionally, clothing behavior varies with the seasons, depending on the climate zone of each city. Notably, even in hot climates, individuals maintain minimum clothing insulation of 0.2 clo (with 1.0 clo representing a short-sleeve shirt and shorts, according to de Freitas, 1987). Another important concept in evaluating outdoor thermal comfort is the "thermal history" of an individual [

28]. For example, whether someone has recently exited an air-conditioned building significantly influences their thermal experience. However, gathering such information is difficult, and the computational simulations required for such analysis are often resource-intensive [

6].

Among the tools used to assess thermal stress, the PET (Physiologically Equivalent Temperature) and UTCI (Universal Thermal Climate Index) are widely recognized [

29,

30]. Both measure the body’s strain responses to calculate the equivalent thermal effect in both reference and actual environments and are acknowledged as reliable indices for evaluating thermal comfort and discomfort in outdoor settings. For analyzing data related to thermal comfort in various spatial configurations, ENVI-met is an exceptionally valuable tool. It provides detailed insights into how different environmental factors influence comfort levels, making it highly effective for evaluating urban design and optimizing spaces for better microclimate performance [

31,

32,

33]. A substantial body of literature employs ENVI-met to explore the effects of urban greenery on microclimatic conditions during Mediterranean heat waves. Studies like those by Magliocco and Perini and Salvalai et alutilize ENVI-met simulations to demonstrate how different configurations and densities of urban vegetation can reduce air temperatures and alleviate the urban heat island effect. These studies provide foundational insights into how strategic use of greenery, such as green roofs and facades, can effectively cool urban environments during heat waves, revealing significant temperature reductions and improvements in thermal comfort indices like the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) [

34,

35].

Furthermore, studies by Tousi et al. and Tseliou et al. delve into comparative analyses of varying greening scenarios, investigating how changes in vegetation type and albedo affect microclimatic conditions. These simulations show that increasing tree cover or integrating green facades can significantly lower air temperatures and enhance pedestrian thermal comfort [

33,

36].

The current body of literature reveals a notable gap in studies that specifically utilize ENVI-met to analyze how different demographic factors, such as gender and age, influence human heat emission through simulation, as opposed to on-site empirical measurements. While ENVI-met is widely recognized as a powerful 3D microclimate simulation tool, it is more commonly applied to assess urban environmental conditions. Researchers frequently use it to explore the impact of urban design elements, such as the presence of vegetation, the configuration of buildings, and materials used in urban settings, on the microclimate. These studies often focus on factors like heat islands, thermal comfort, and energy consumption in urban spaces, but the potential of ENVI-met to simulate human heat dissipation concerning demographic variations remains underexplored.

A study on the thermal comfort of the elderly in Sao Paulo uses ENVI-met but lacks a comprehensive approach covering a variety of demographic factors [

37]. It is one of the few that begins to explore demographic differences. This indicates that while ENVI-met is widely used for evaluating thermal comfort improvements through urban interventions, existing literature does not sufficiently address how different demographic factors such as age and gender affect thermal comfort perceptions. This remains an underexplored area warranting further research, especially in regions beyond the Mediterranean Sea.

This lack of focused research underscores an opportunity for further investigation, particularly in urban health studies where understanding how various groups experience and cope with heat could improve city planning, thermal comfort strategies, and public health interventions. Furthermore, advancing the application of ENVI-met in this direction could help bridge the knowledge gap in how age and gender-specific physiological differences manifest in microclimate interactions. This would be particularly useful in the context of rising temperatures and the increasing focus on urban resilience in response to climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

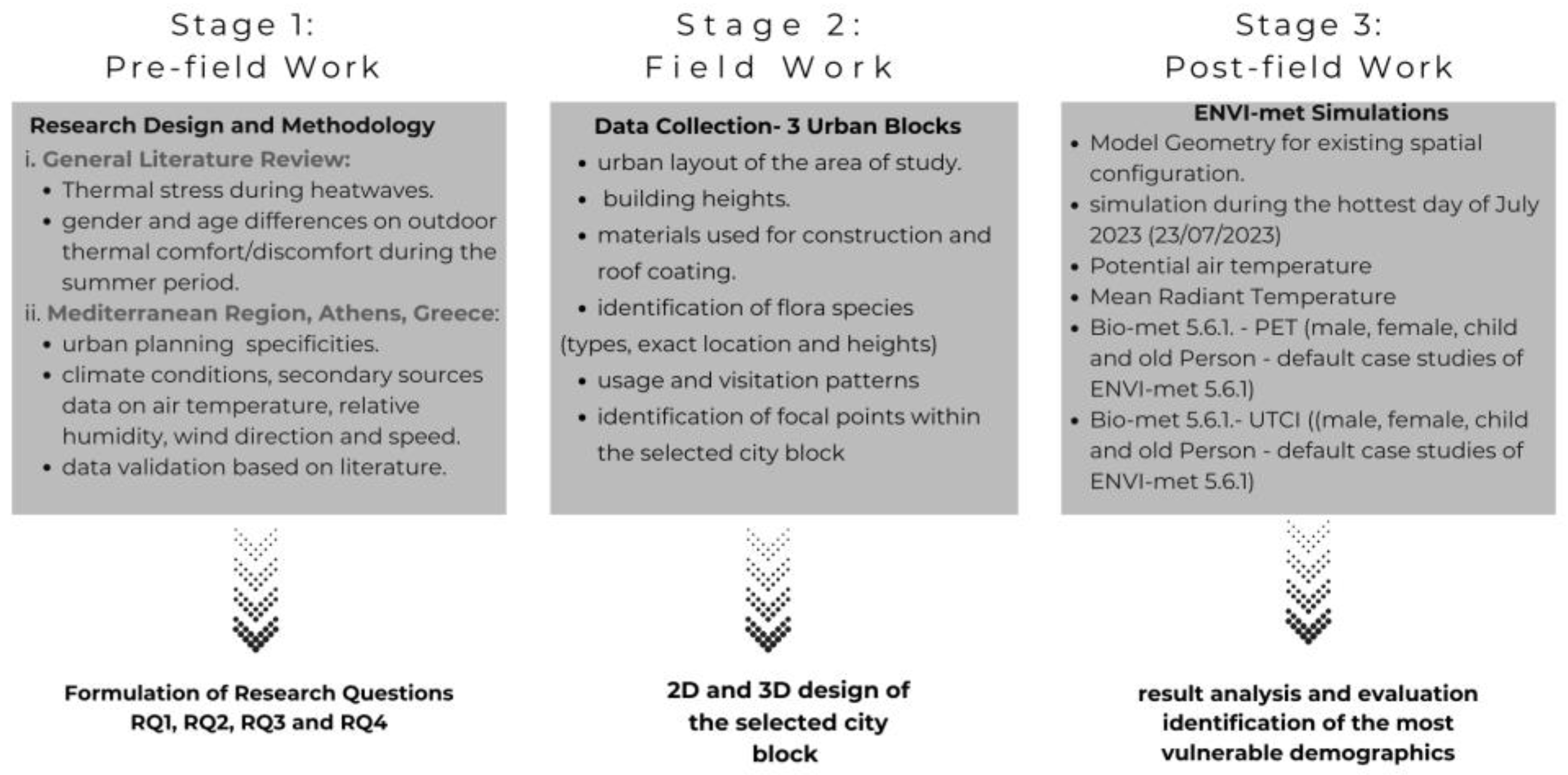

The research is structured into three distinct phases, as outlined in

Figure 1. The first phase involves pre-fieldwork analysis, which includes a comprehensive literature review with a particular emphasis on thermal stress analysis during heatwaves in the Mediterranean region. This review focuses specifically on studies examining gender and age differences in thermal comfort during such extreme weather events. The first phase concludes with the formulation of four key research questions.

RQ1:Are there any notable differences in PET and UTCI values between 35-year-old adult males and females during Mediterranean heatwaves in ENVI-met simulations?

RQ2: Are there any significant differences in PET and UTCI values during Mediterranean heatwaves between 35-year-old adult males and females, and 80-year-old elderly individuals in ENVI-met simulations?

RQ3:Are there any significant differences in PET and UTCI values during Mediterranean heatwaves between 35-year-old adult males and females, and 8-year-old children in ENVI-met simulations?

RQ4: Based on ENVI-met simulations, which demographic group—35-year-old males, 35-year-old females, 80-year-old elderly, or 8-year-old children—is the most vulnerable to heat stress during Mediterranean heat waves?

Stage 2 places a strong emphasis on data collection through fieldwork. Specifically, the authors have gathered key information pertinent to the analysis of urban geometry and the characteristics of both the built and natural environments within the study area. This includes data on flora species, construction materials, and the volumes and heights of buildings, culminating in the development of 2D and 3D models of the selected city blocks.

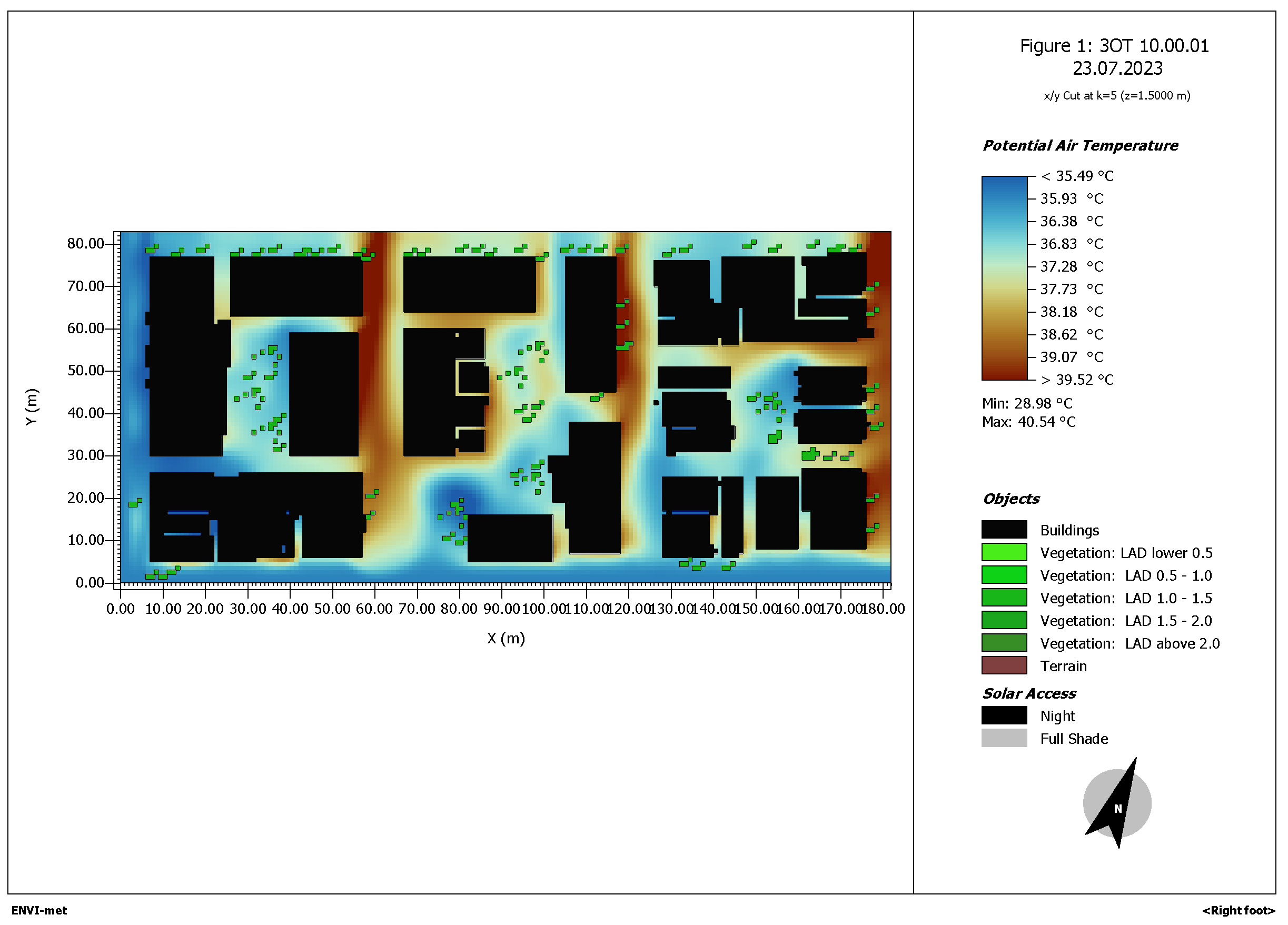

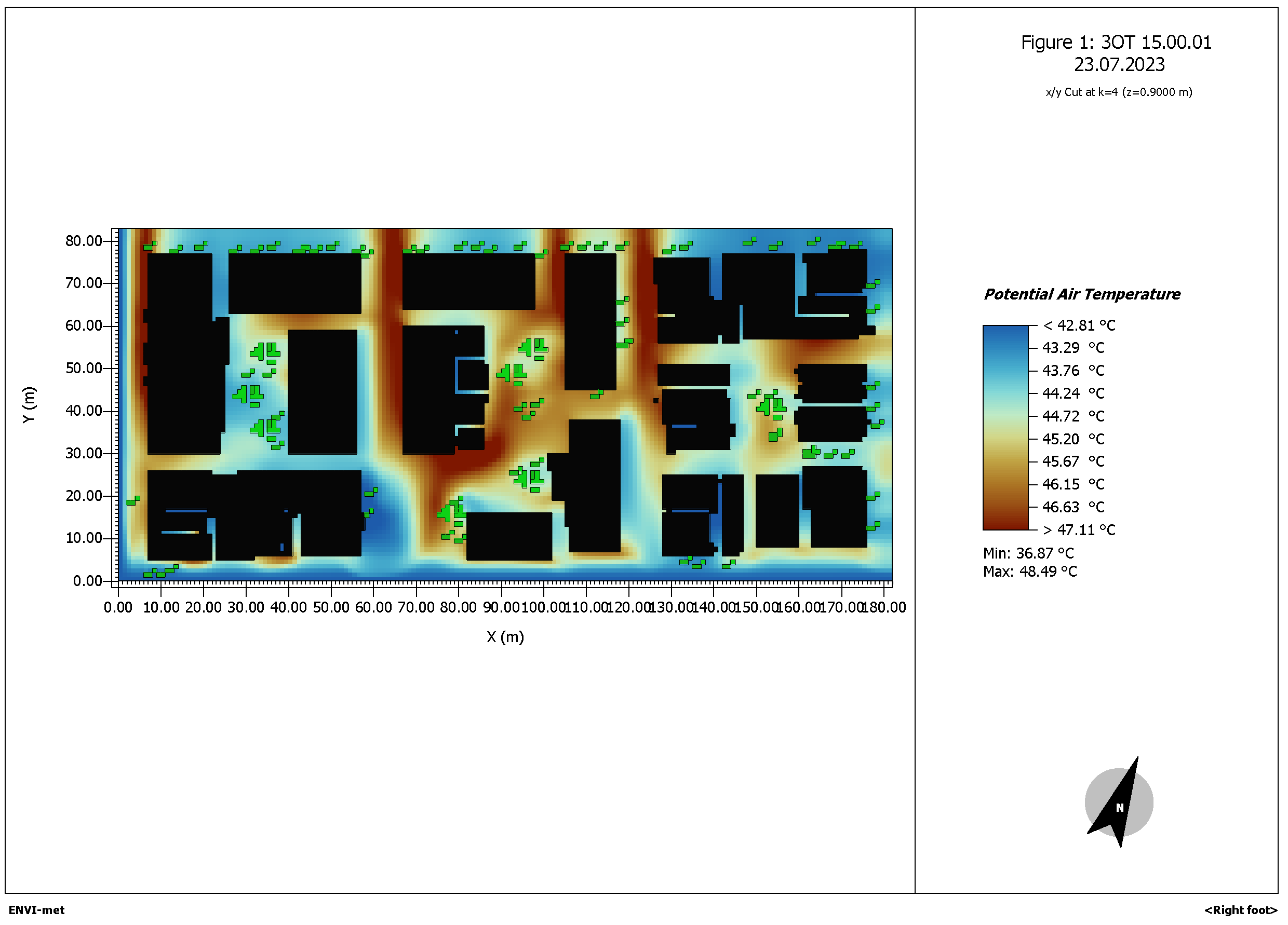

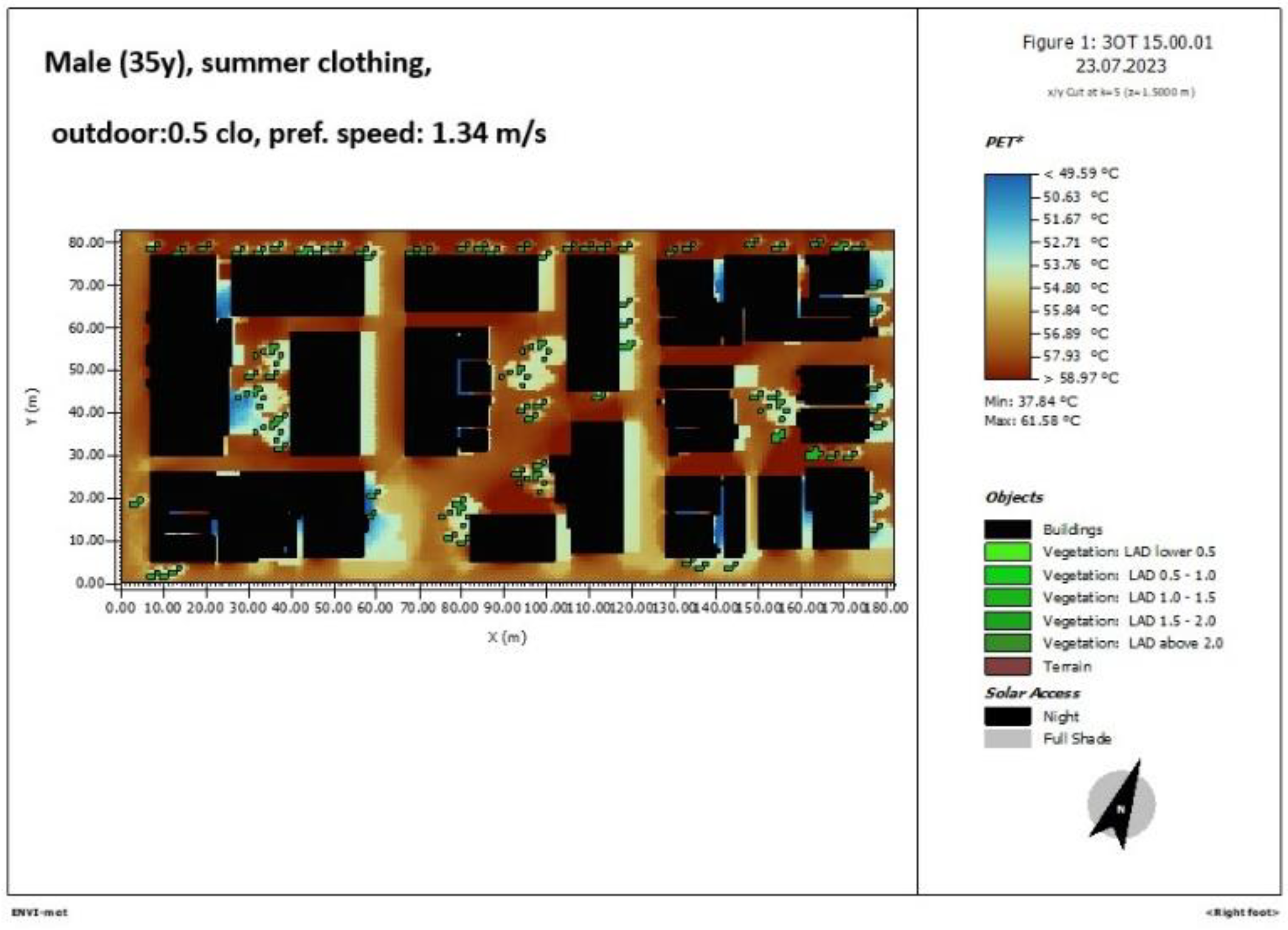

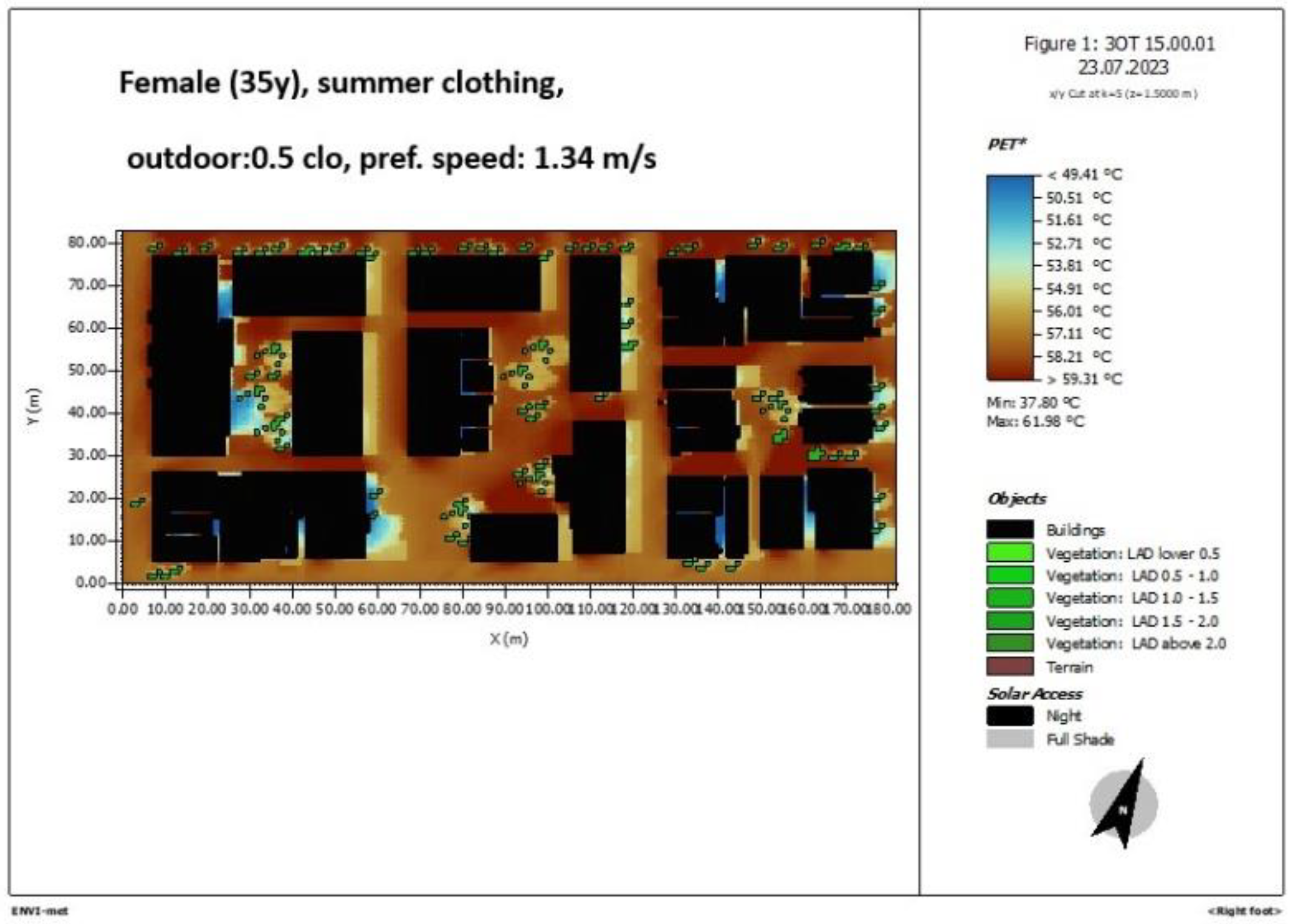

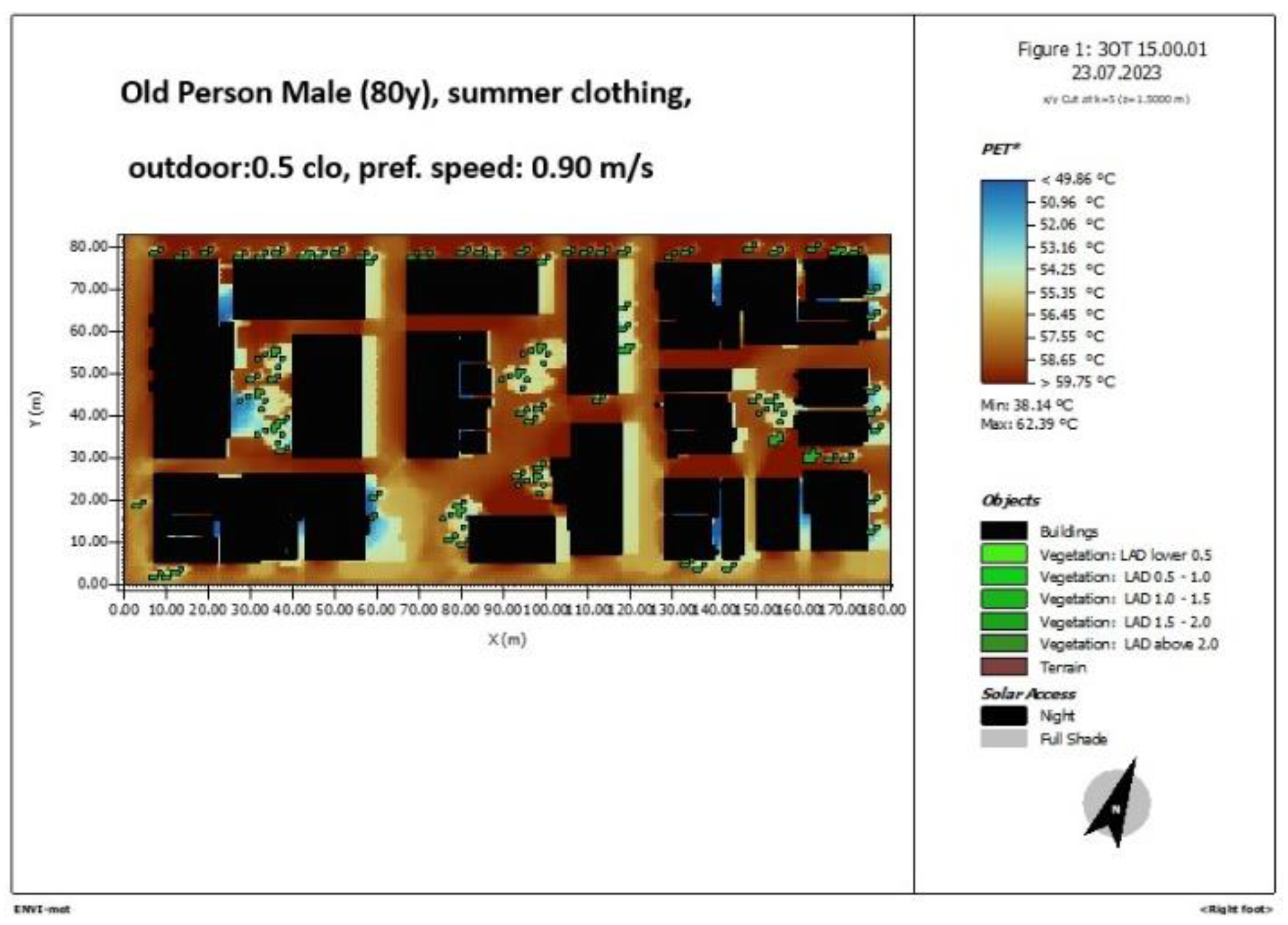

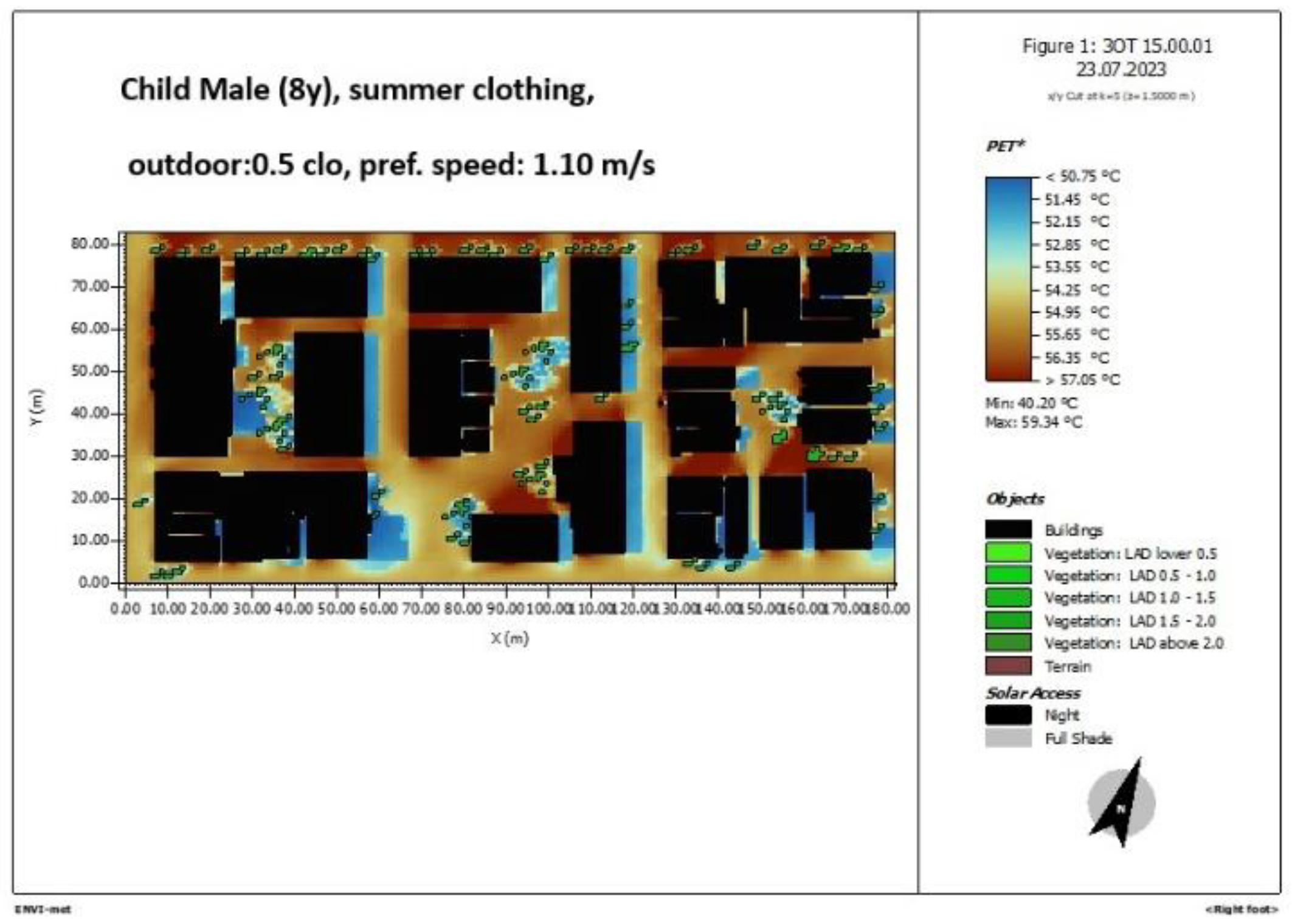

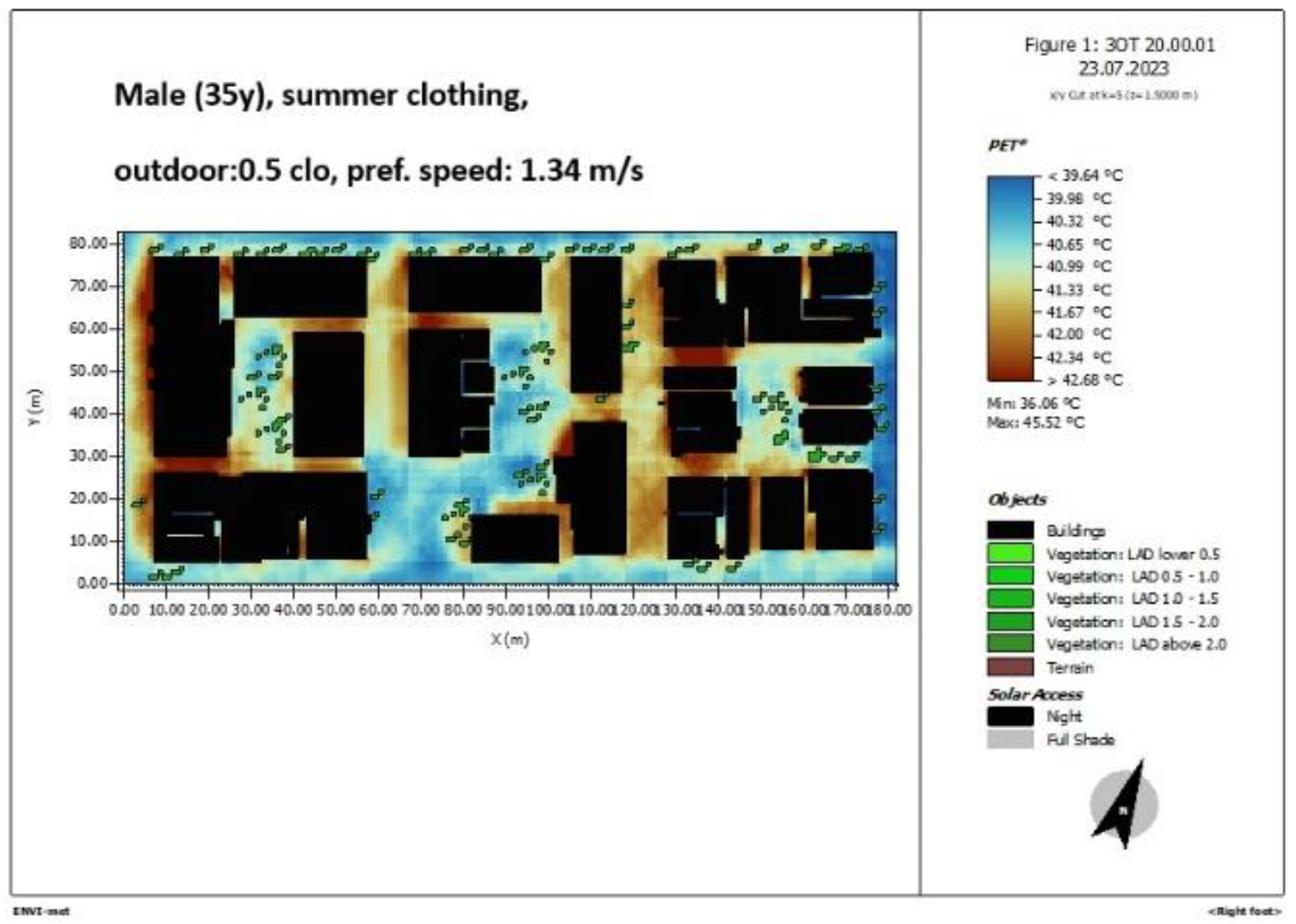

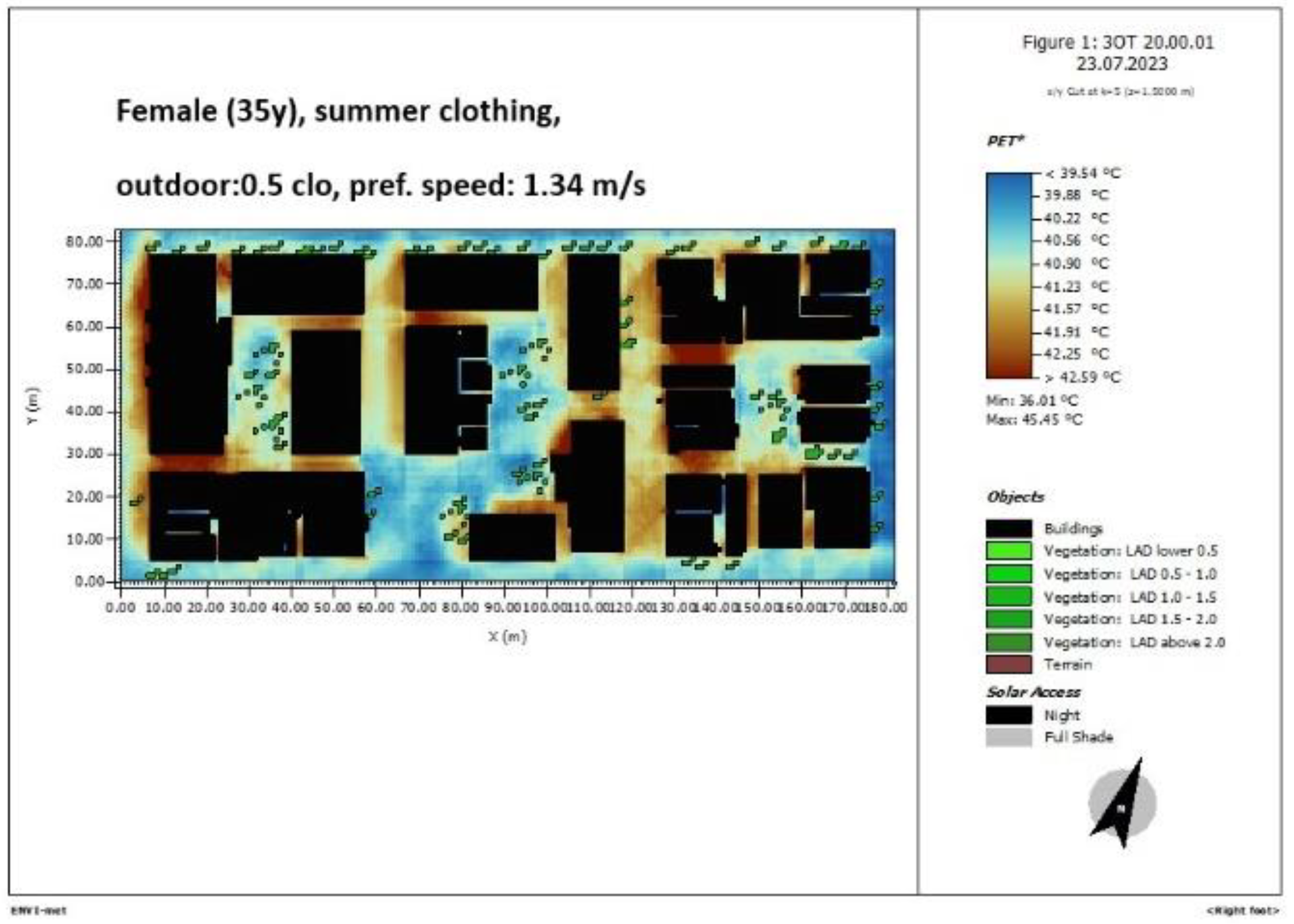

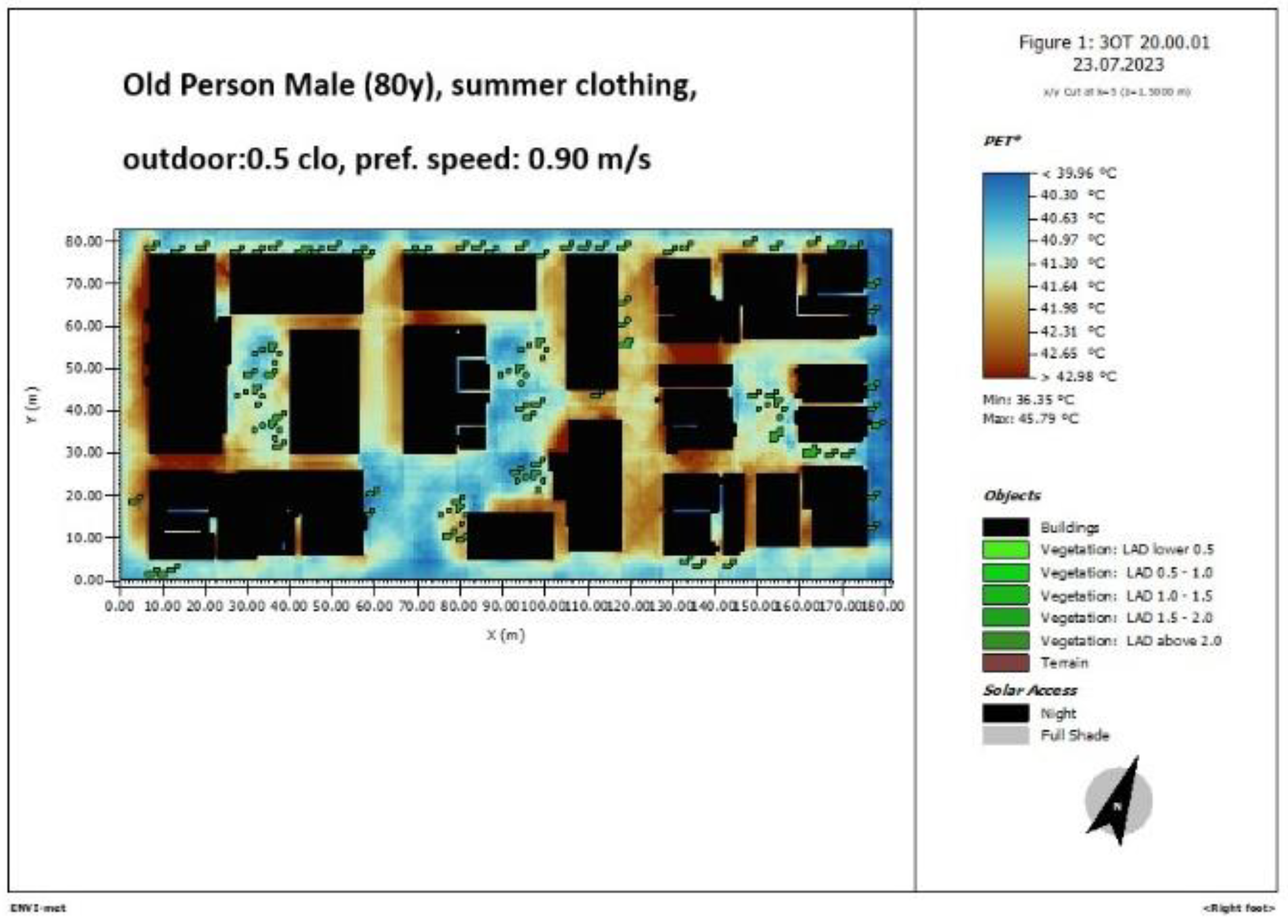

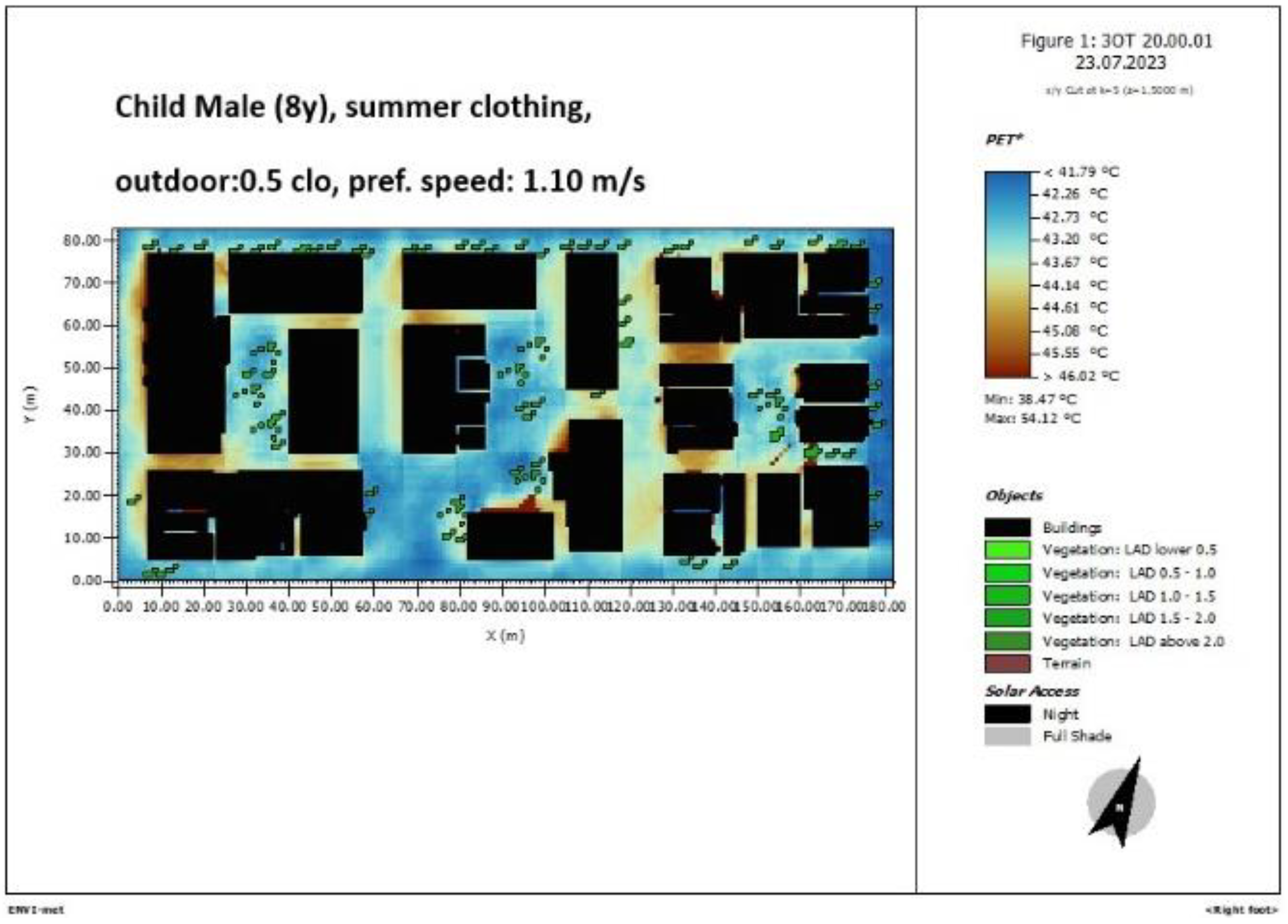

Stage 3 focuses on post-fieldwork analysis, during which ENVI-met simulations were conducted. The authors selected the hottest day in July 2023, specifically the 23rd of July, to examine thermal stress variations across different demographic groups. On that day, the maximum air temperature was recorded at 41.7°C at 3 p.m., while the minimum air temperature was documented as 30.9°C at 6 a.m. Relative humidity reached a maximum of 54% at 6 a.m. and dropped to a minimum of 23% at 3 p.m. The average wind speed was measured at 4.6 km/h (1.27 m/s), with a wind direction of 180°. The total simulation time spanned 48 hours. Mean radiant temperature and potential air temperature were evaluated for three specific times of the day: 10 a.m., 3 p.m., and 8 p.m. In ENVI-met simulations, Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT) represents the combined effect of all surrounding surface temperatures and radiation (both direct solar and reflected). It quantifies the heat exchange between an individual and the environment, offering a key measure of thermal exposure and human comfort in outdoor spaces. Additionally, the ENVI-met Bio-met tool was employed to assess heat stress levels among various demographic groups, including 35-year-old males (summer clothing, 0.5 clo, preferred speed of 1.34 m/s), 35-year-old females (same settings), an 80-year-old male (0.5 clo, preferred speed of 0.9 m/s), and an 8-year-old male child (summer clothing, 0.5 clo, preferred speed of 1.10 m/s). It is important to note that these demographic settings are based on Bio-met’s default parameters. The authors evaluated PET (Physiological Equivalent Temperature) and UTCI (Universal Thermal Climate Index) values for the three selected times of the day to address the four research questions outlined earlier. For the analysis of PET and UTCI results the Mediterranean scale has been employed as in similar studies in the Mediterranean Region (Table 1)[

38].

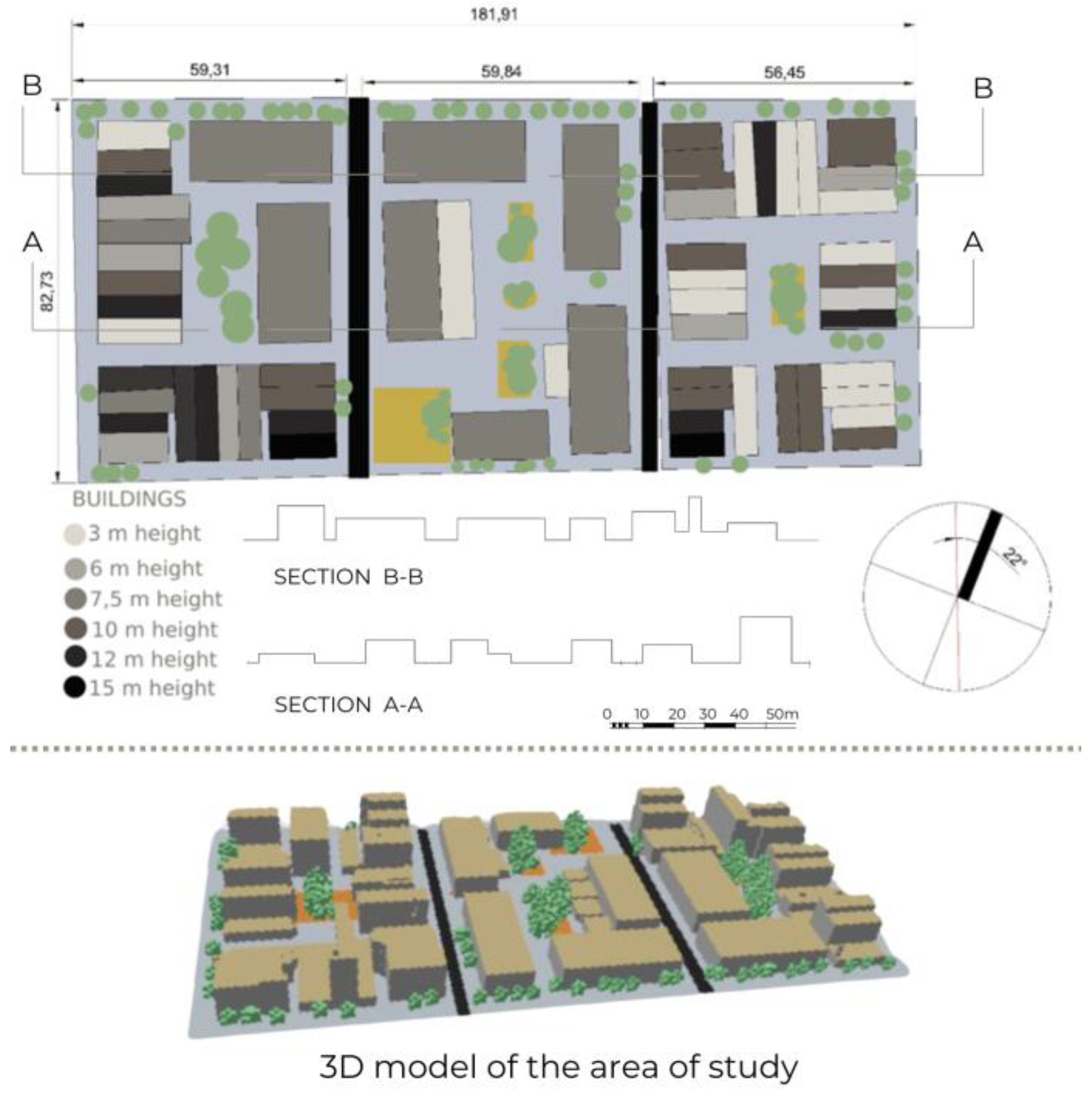

The spatial analysis of the study area, encompassing three city blocks, is illustrated in

Figure 2. This area, located in the Greater Athens Region, is a post-refugee urban settlement designed according to the principles of the Hippodamian grid during the interwar period. Characterized by high building and population density, it is home to vulnerable households [

33]. The layout includes a communal open space in the interior of each block, with a mixture of typical blocks of flats and refugee housing organized along the perimeter.

4. Discussion

Based on research findings, the elderly population is more vulnerable to heat waves compared to the younger population. This finding aligns with previous research, which has shown that the elderly population is especially vulnerable to high temperatures, particularly during heat waves. [

39,

40,

41]. It is important to note though that children experience significant thermal stress, with both their baseline and peak exposure levels exceeding those of elderly individuals. Children display a wider range of PET values, reflecting greater variability in their thermal stress levels, characterized by higher minimum values and substantial stress. In contrast, elderly individuals, as well as 35-year-old males and females, experience more moderate and stable levels of thermal stress. Overall, while the cooling effect of the evening mitigates thermal stress for all groups, children remain subject to more pronounced stress compared to elderly individuals, males, and females. To be more specific, the PET analysis across the four selected demographic groups at 10 a.m. demonstrates only slight variations in thermal values, with the spatial distribution of heat exhibiting comparable patterns across all examined categories. This suggests a uniform distribution of thermal stress during morning hours, irrespective of demographic distinctions. PET analysis at 3 p.m. however, shows that minimum PET values for children are significantly higher than those for adults, indicating a heightened baseline level of thermal stress. Their mean and maximum PET values are lower than those observed in other demographic groups, although still considerable, underscoring notable heat exposure in this age group. In summary, while all demographic groups experience substantial thermal stress, its magnitude and variability differ according to age. The elderly are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat, as reflected by their higher maximum PET values, whereas children face a greater baseline thermal stress in comparison to adults. The evening PET values demonstrate varying levels of thermal stress across different demographic groups, as measured by the Mediterranean PET scale. Children exhibit a wider range of PET values, indicating greater variability in thermal stress, with higher minimum values and significant levels of exposure. In contrast, elderly individuals, along with 35-year-old males and females, experience more moderate and consistent thermal stress levels. Overall, although the cooling effect of the evening mitigates thermal stress for all groups, children are subject to more pronounced stress compared to elderly individuals, males, and females.

In addition, research findings showed that females are more vulnerable to heat compared to males. This finding is consistent with numerous studies showing that women are at a higher risk of thermal stress and heat-related mortality. However, a smaller body of research suggests that men may be more vulnerable than women in some cases [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. It is important to mention that, while the UTCI values for all four demographic groups fall within a similar range (morning, afternoon, and evening hours), the implications of these values vary significantly. For 35-year-olds, elevated UTCI values tend to result in less severe effects compared to older adults and children. Older adults are at greater risk of heat stress, whereas children exhibit heightened sensitivity to high UTCI values. Recognizing these differences is critical for the development of age-specific strategies aimed at managing heat stress and ensuring thermal comfort across various demographic groups. By considering these variations alongside the UTCI Mediterranean scale, more effective measures can be implemented to address the distinct needs of each group, ultimately improving overall thermal comfort and health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Methodology scheme.

Figure 1.

Methodology scheme.

Figure 2.

Spatial layout of the area of study, 2D and 3D models.

Figure 2.

Spatial layout of the area of study, 2D and 3D models.

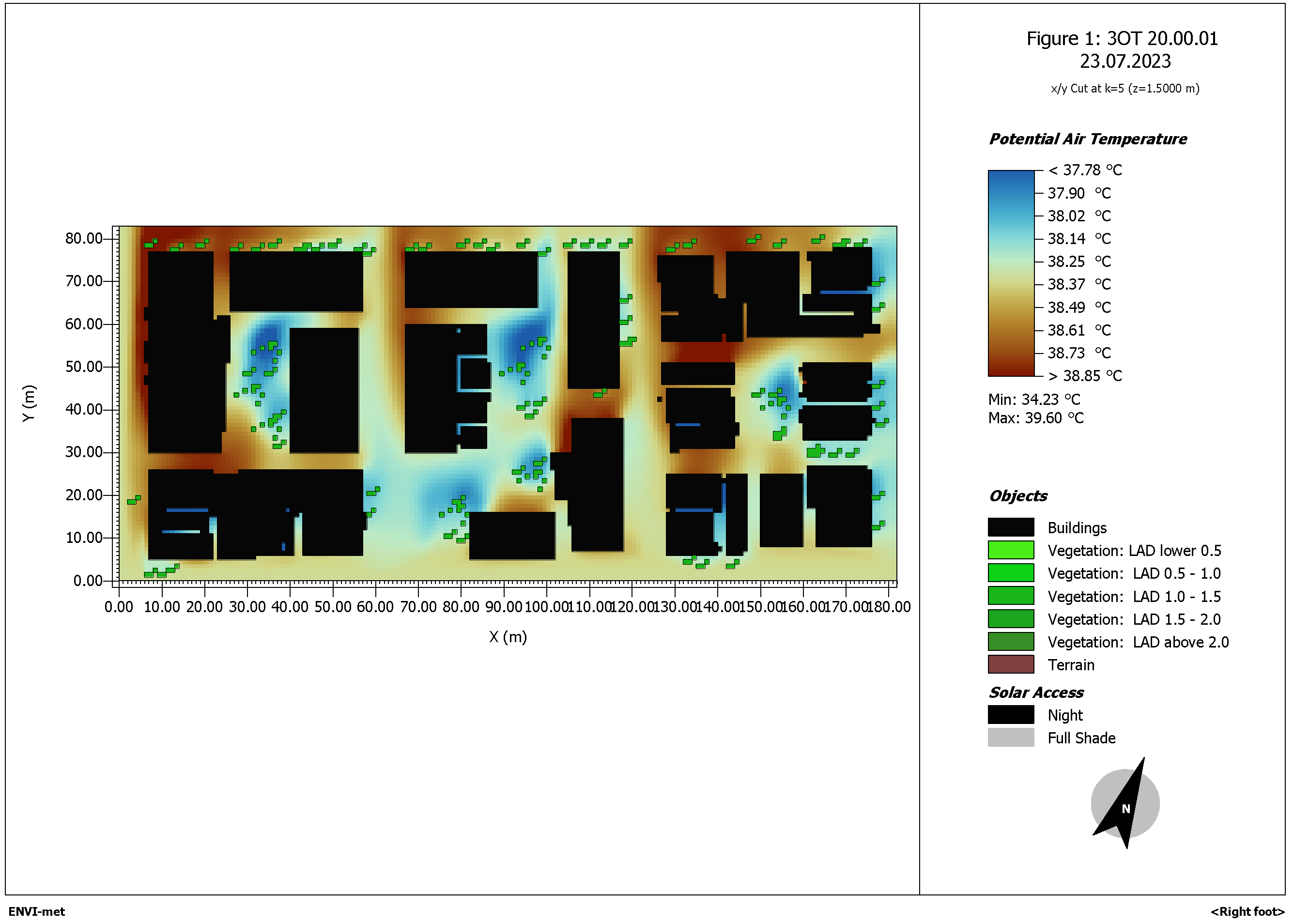

Figure 3.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 10 a.m.

Figure 3.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 10 a.m.

Figure 4.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 10 a.m.

Figure 4.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 10 a.m.

Figure 5.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 8 p.m.

Figure 5.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Potential air temperature at 8 p.m.

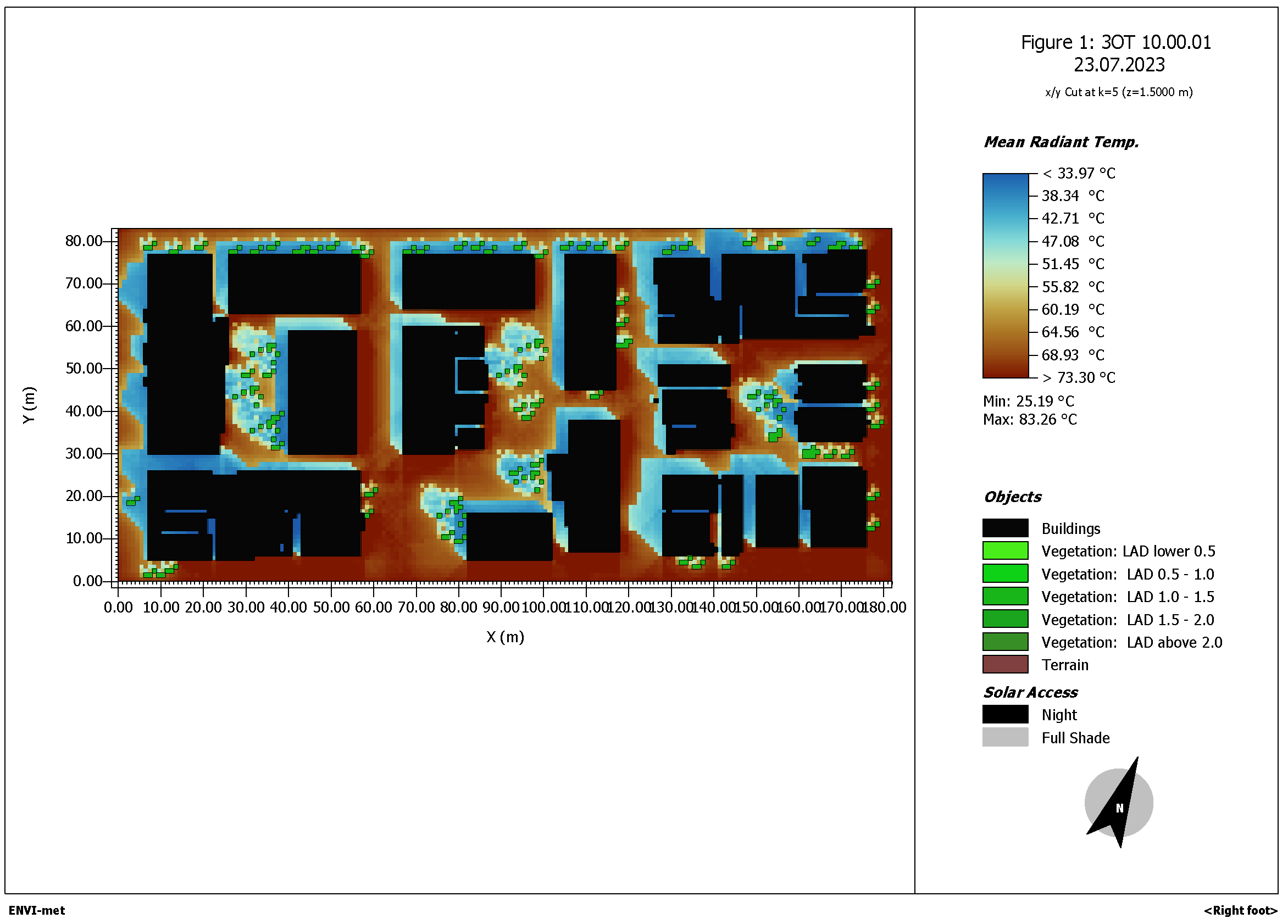

Figure 6.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 10 a.m.

Figure 6.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 10 a.m.

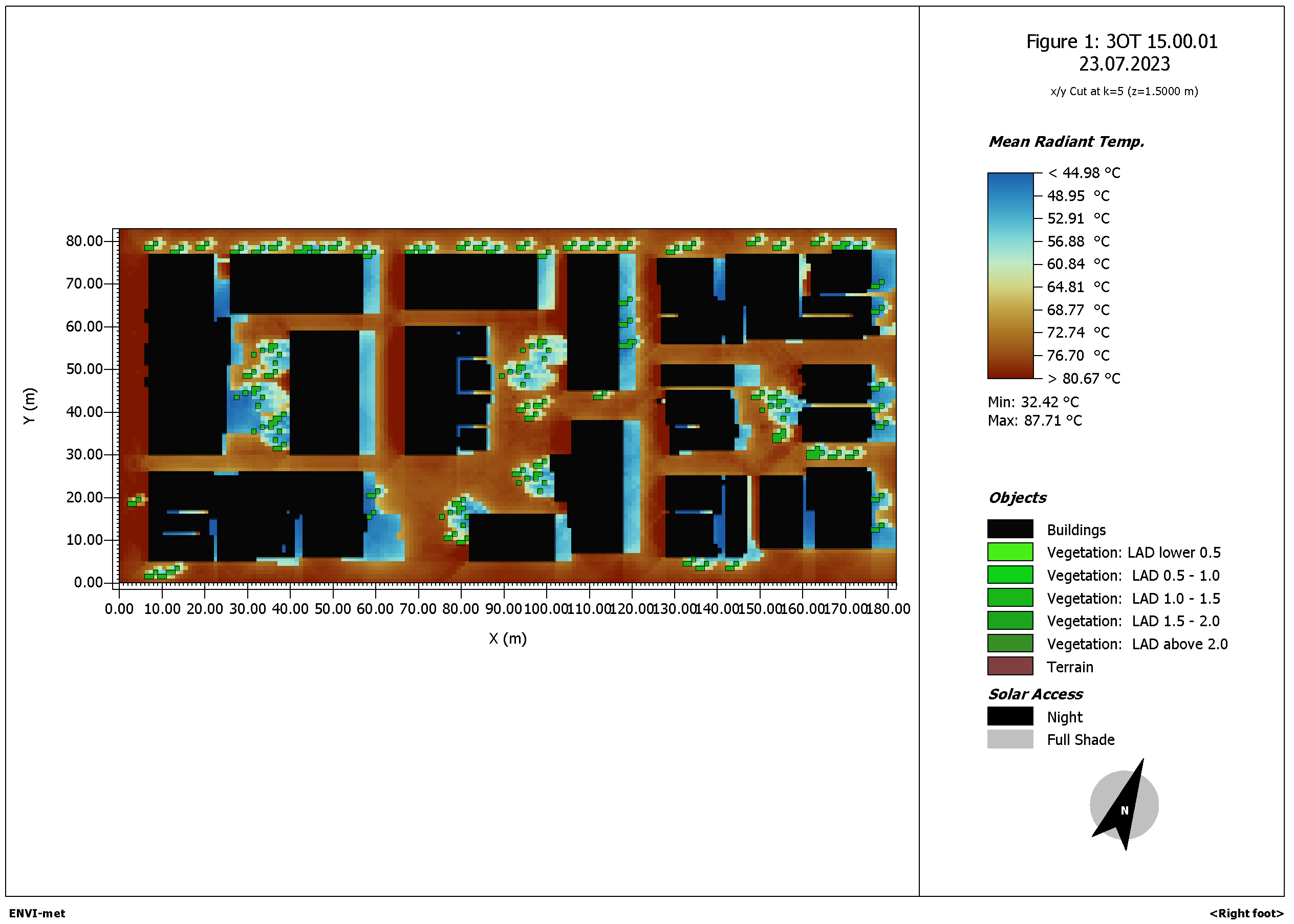

Figure 7.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 3 p.m.

Figure 7.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 3 p.m.

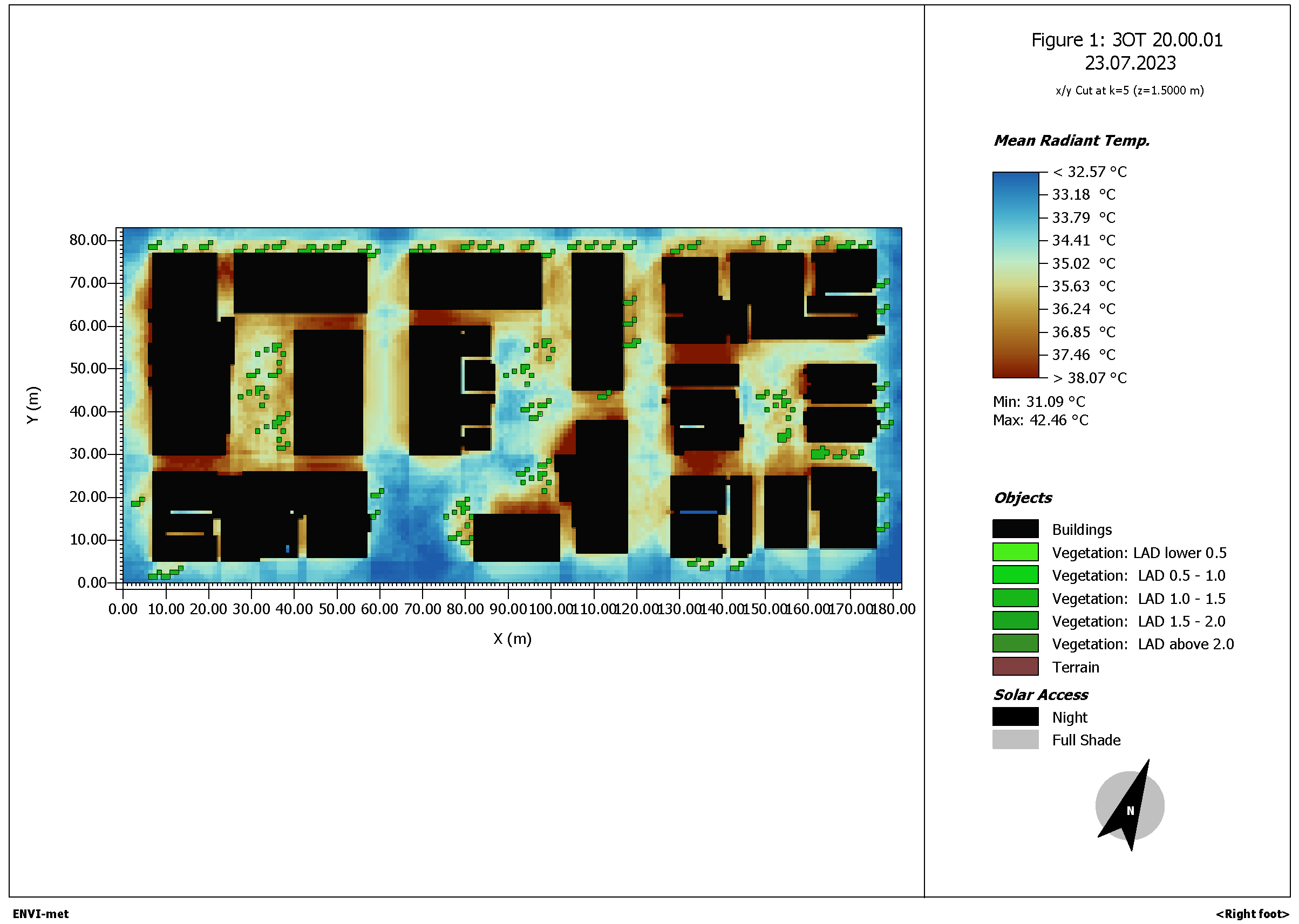

Figure 8.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 8 p.m.

Figure 8.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, Mean Radiant temperature at 8 p.m.

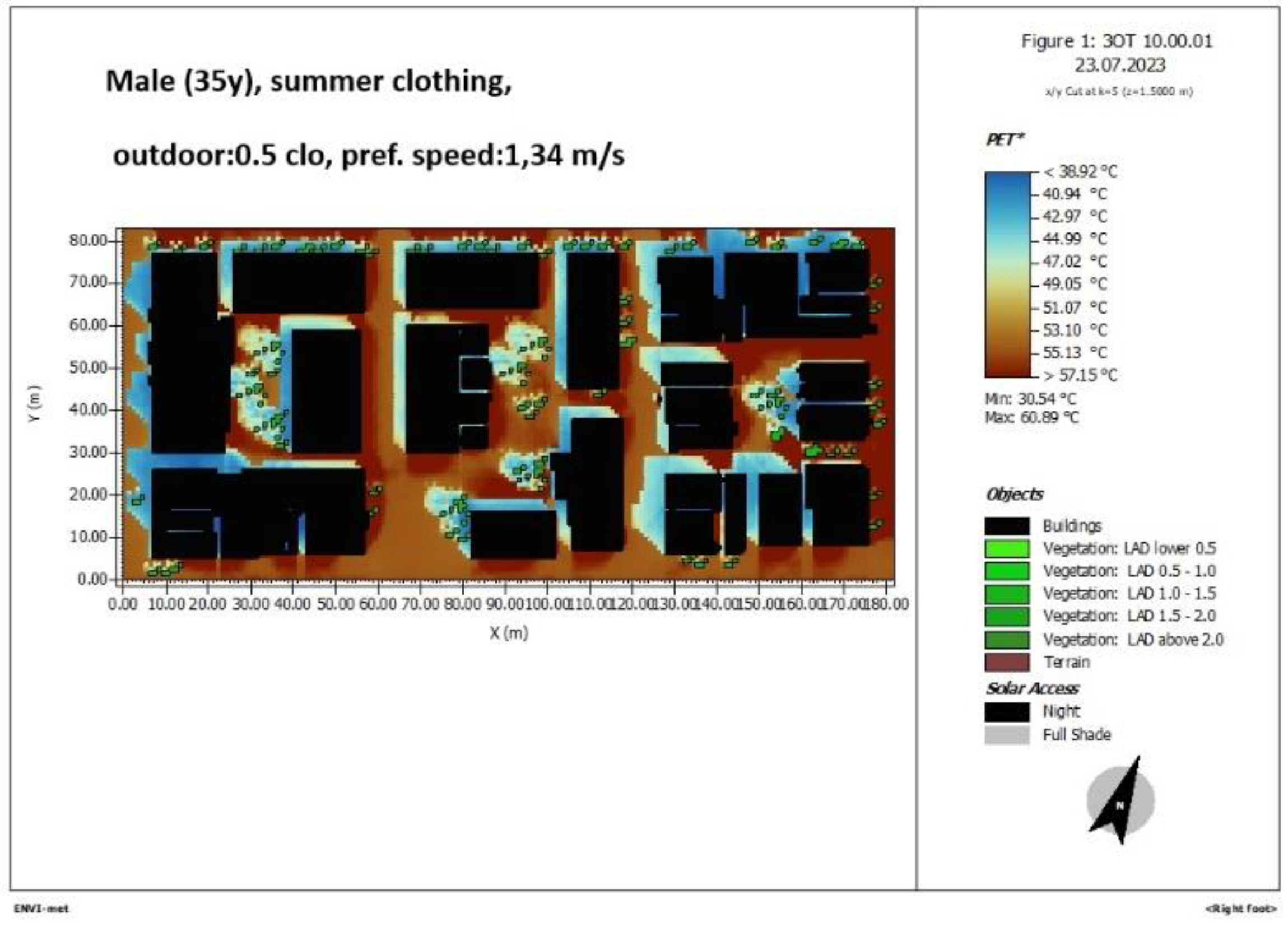

Figure 9.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., male 35 years old, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1,34m/s.

Figure 9.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., male 35 years old, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1,34m/s.

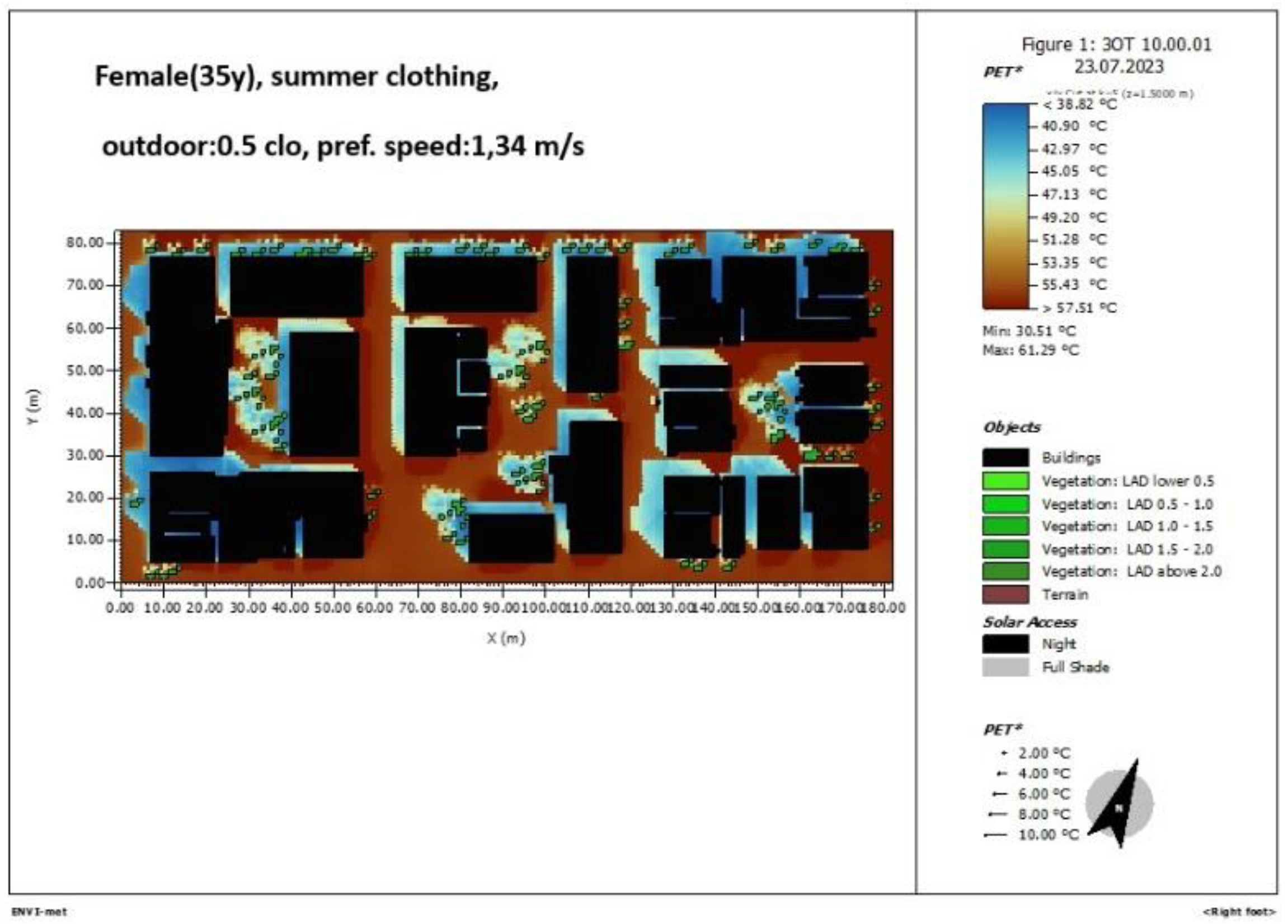

Figure 10.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., female 35 years old, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1,34m/s.

Figure 10.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., female 35 years old, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1,34m/s.

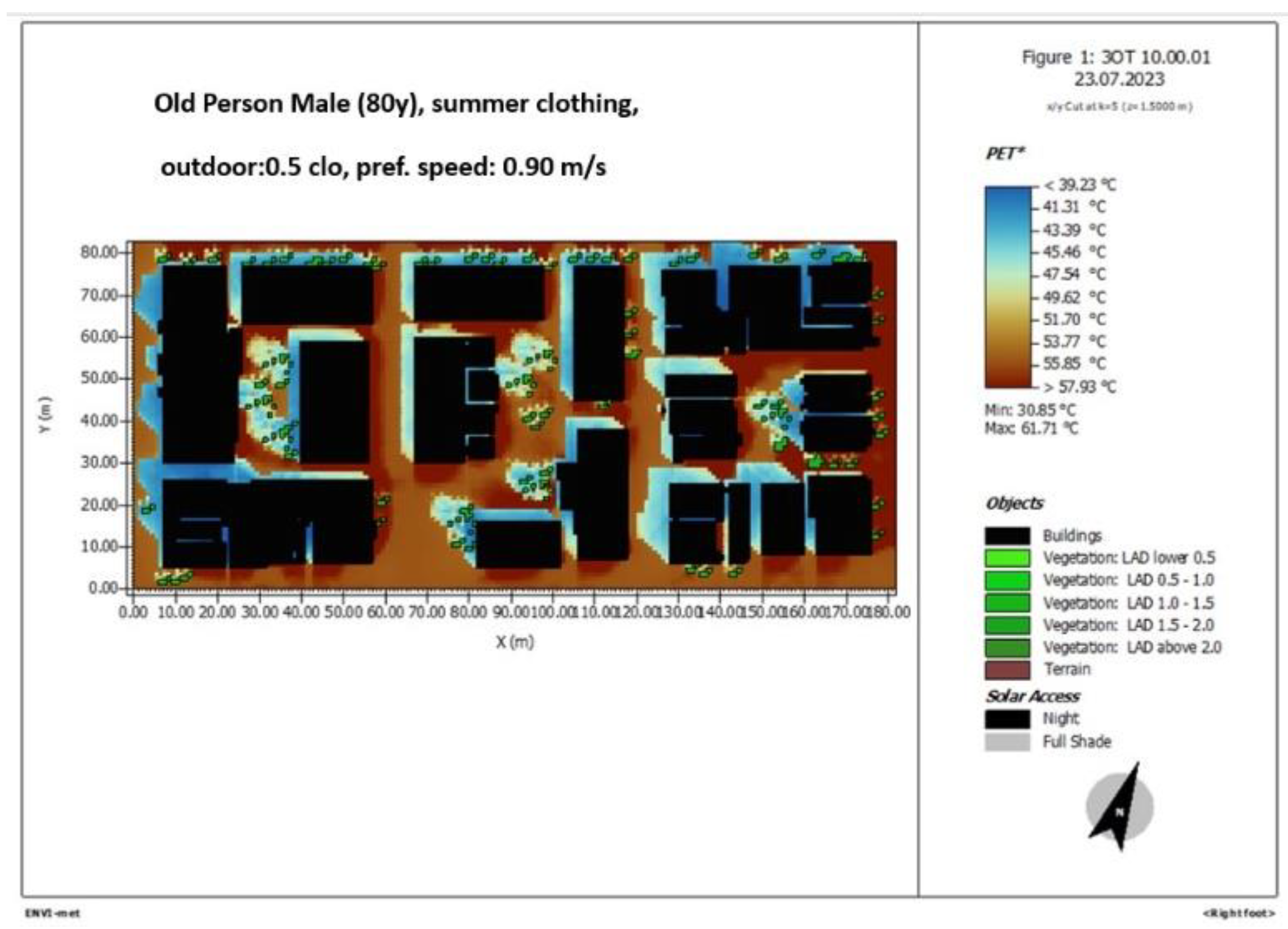

Figure 11.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., old person 80y male, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

Figure 11.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., old person 80y male, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

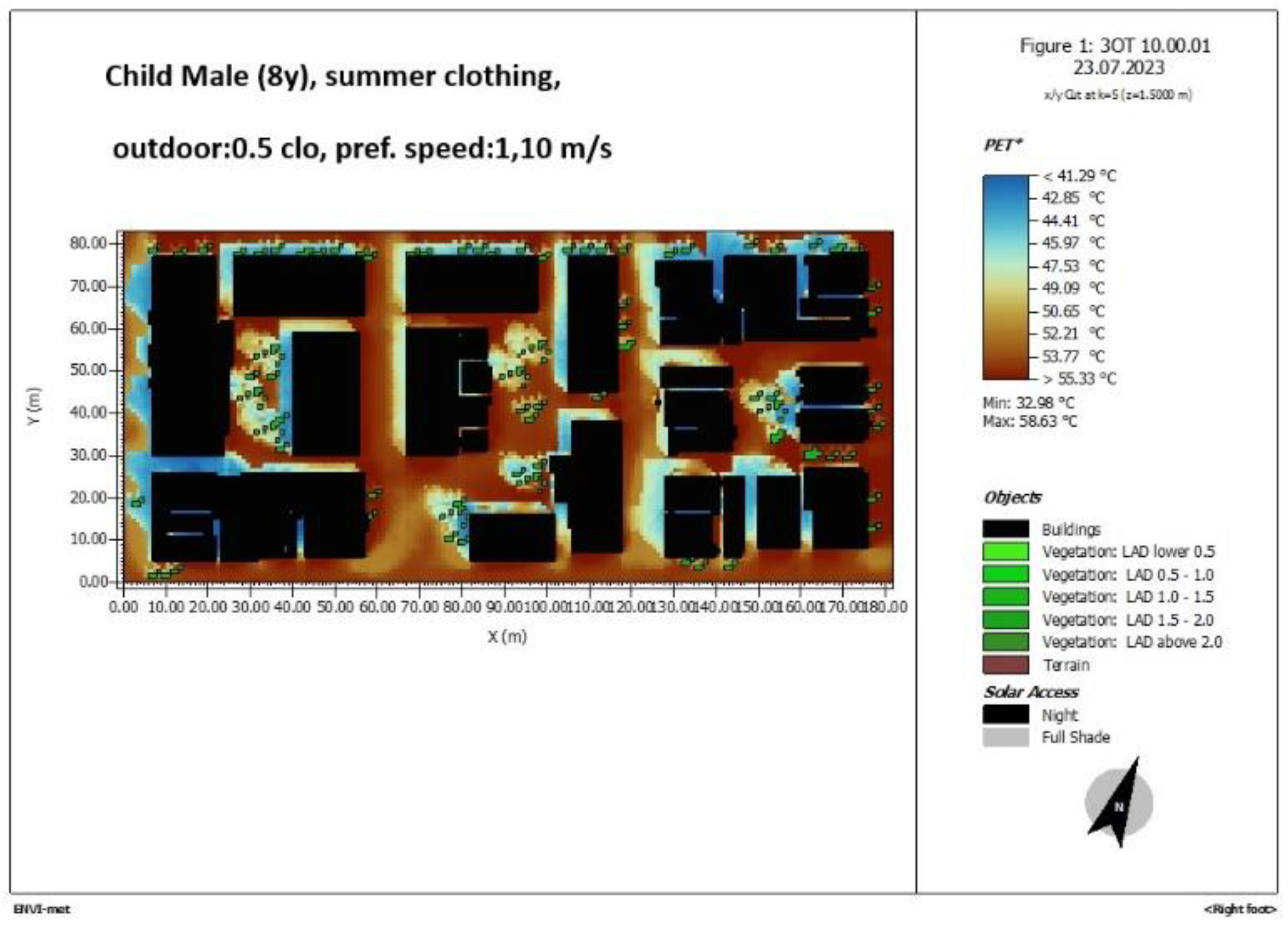

Figure 12.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., child male 8y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

Figure 12.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 10 a.m., child male 8y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

Figure 13.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., male 35y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s .

Figure 13.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., male 35y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s .

Figure 14.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., female 35y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s .

Figure 14.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., female 35y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s .

Figure 15.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., old person male 80y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

Figure 15.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., old person male 80y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

Figure 16.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., child male 8 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

Figure 16.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 3 p.m., child male 8 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

Figure 17.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., male 35 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s.

Figure 17.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., male 35 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s.

Figure 18.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., female 35 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s.

Figure 18.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., female 35 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.34 m/s.

Figure 19.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., old person male 80 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

Figure 19.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., old person male 80 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 0.90 m/s.

Figure 20.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., child male 8 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

Figure 20.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, PET 8 p.m., child male 8 y, summer clothing, 0.5 clo, pref.speed 1.10 m/s.

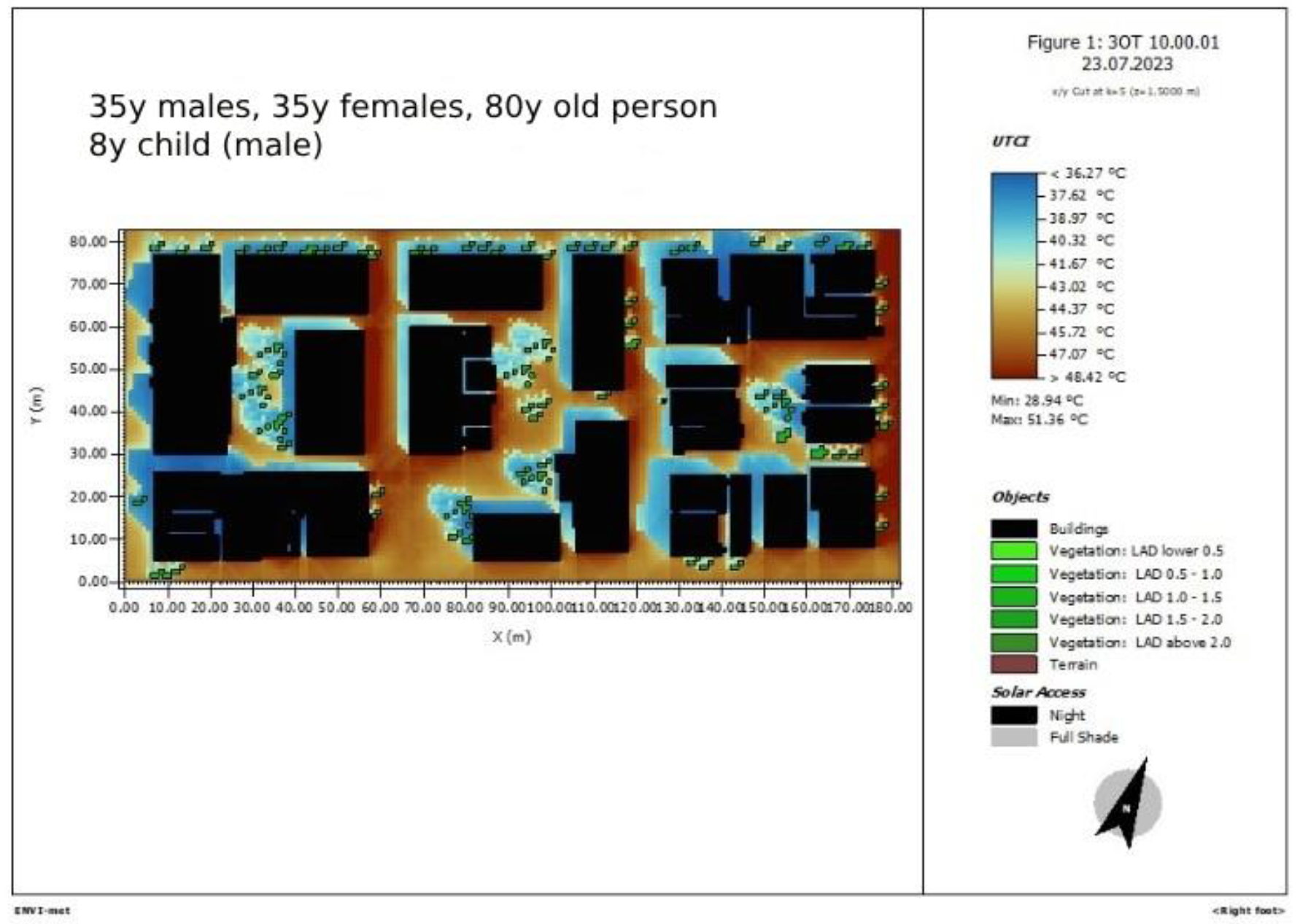

Figure 21.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 10 a.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.

Figure 21.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 10 a.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.

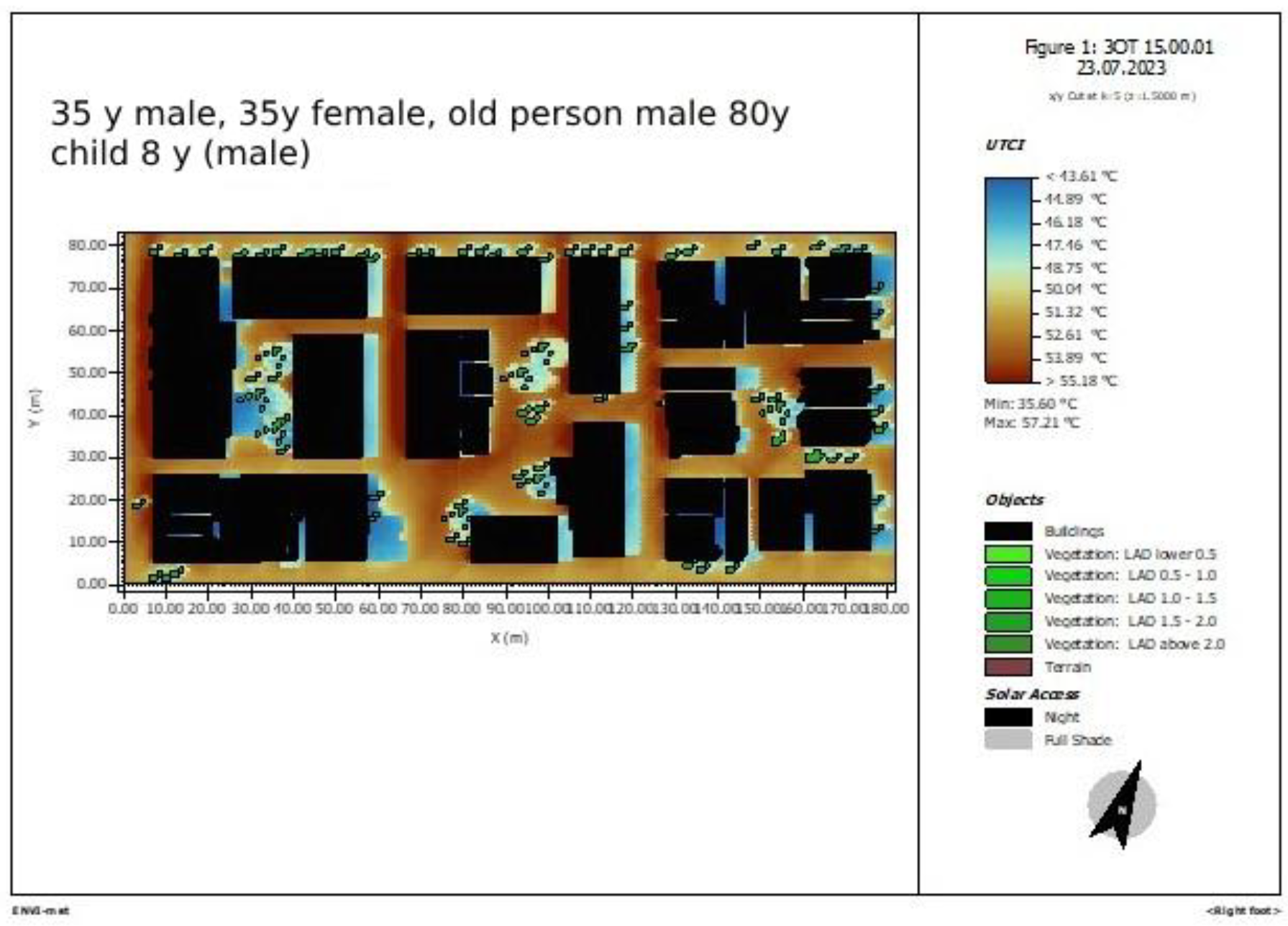

Figure 22.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 3 p.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.

Figure 22.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 3 p.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.

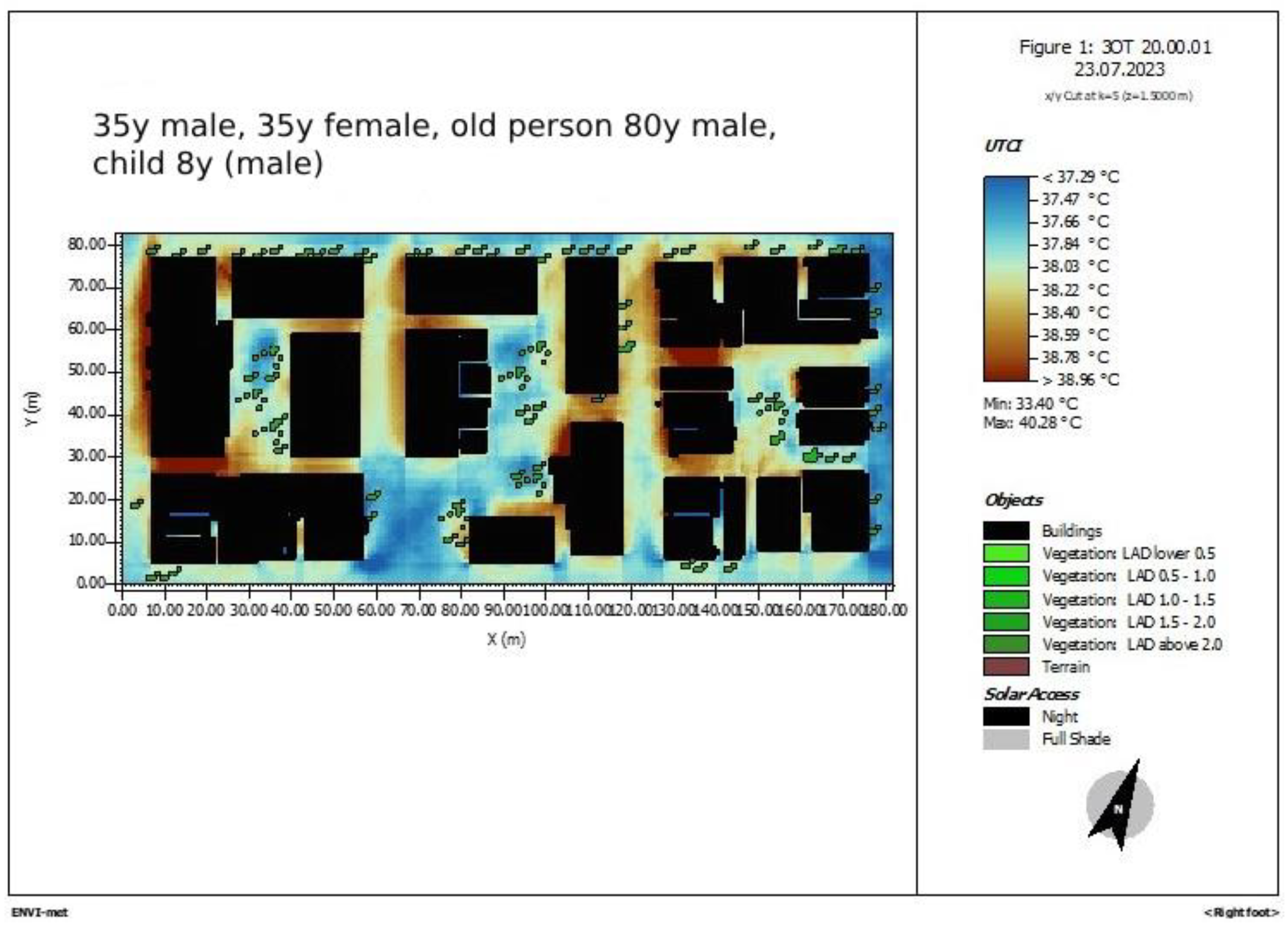

Figure 23.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 8 p.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.

Figure 23.

ENVI-met simulation of the area of study, UTCI 8 p.m., male 35y, female 35y, old person male 80y and child male 8y.