Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

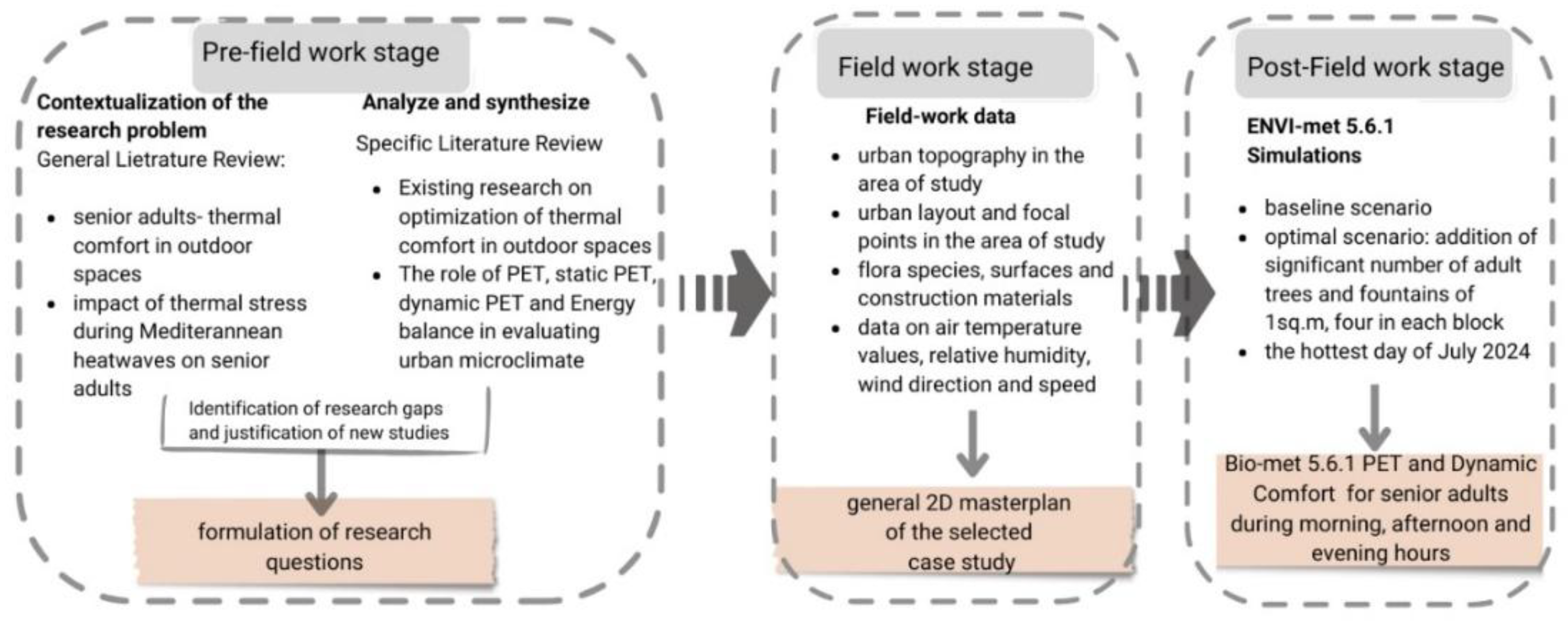

2. Materials and Methods

- RQ1: What is the impact of existing urban conditions in a densely built neighborhood of Greater Athens on the outdoor thermal comfort of senior adults during extreme heat events?

- RQ2: How do nature-based interventions, such as mature trees and water features, mitigate thermal stress by reducing Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) and enhancing dynamic thermal comfort for elderly individuals?

- RQ3: How effective are established urban design strategies in enhancing thermal resilience for vulnerable populations, such as senior adults?

| PET (°C). | Mediterranean Scale b | Thermal comfort Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Original Scale a | ||

| > 41.1 | > 40.0 | Very hot |

| 35.1 to 41.0 | 34.0 to 40.0 | Hot |

| 29.1 to 35.0 | 28.0 to 34.0 | Warm |

| 23.1 to 29.0 | 26.0 to 28.0 | Slightly warm |

| 18.1 to 23.0 | 19.0 to 26.0 | Neutral |

| 13.1 to 18.0 | 15.0 to 19.0 | Slightly cool |

| 8.1 to 13.0 | 12.0 to 15.0 | Cool |

| 4.1 to 8.0 | 8.0 to 12.0 | Cold |

| <4.0 | <8.0 | Very cold |

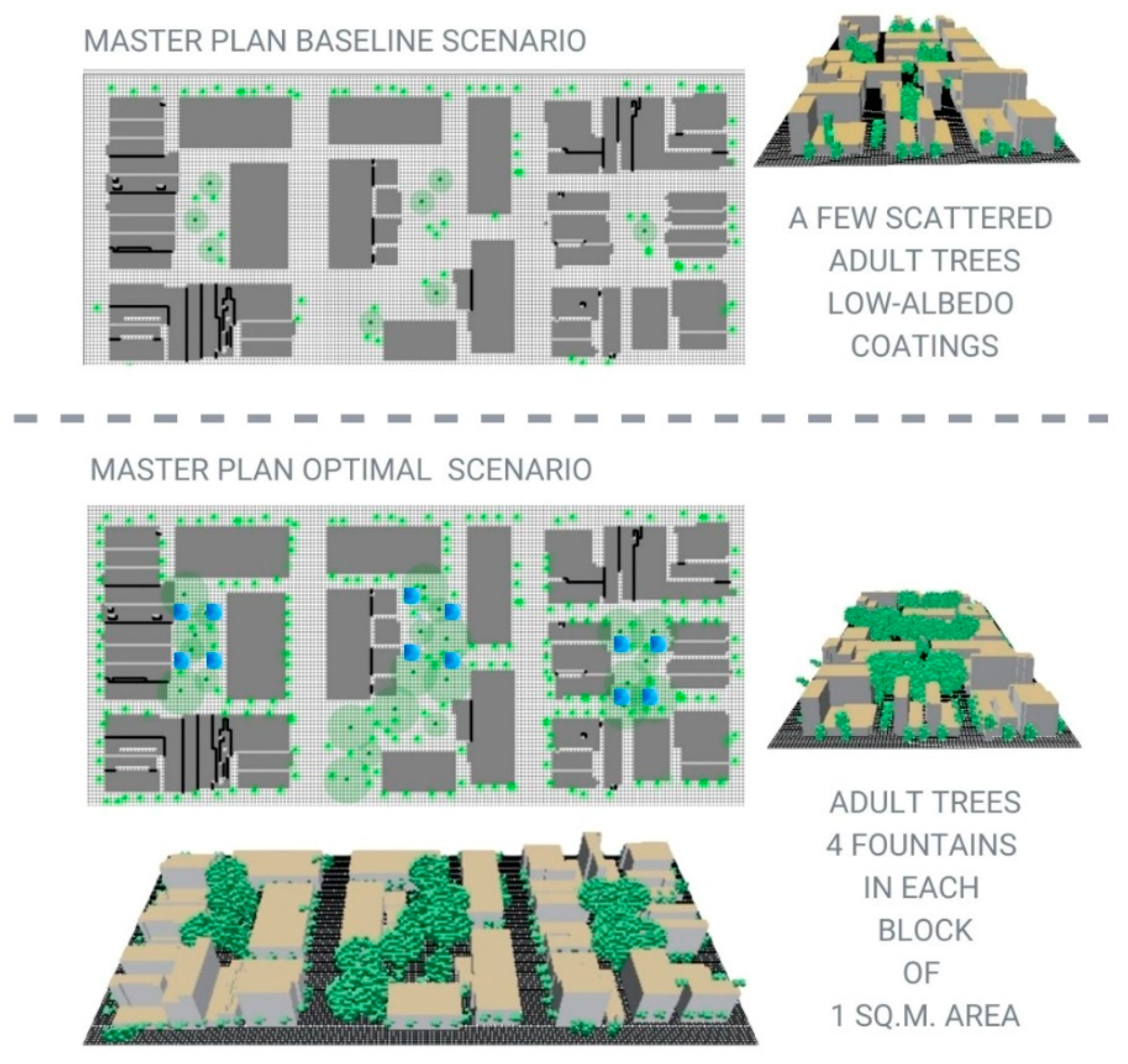

3. Results

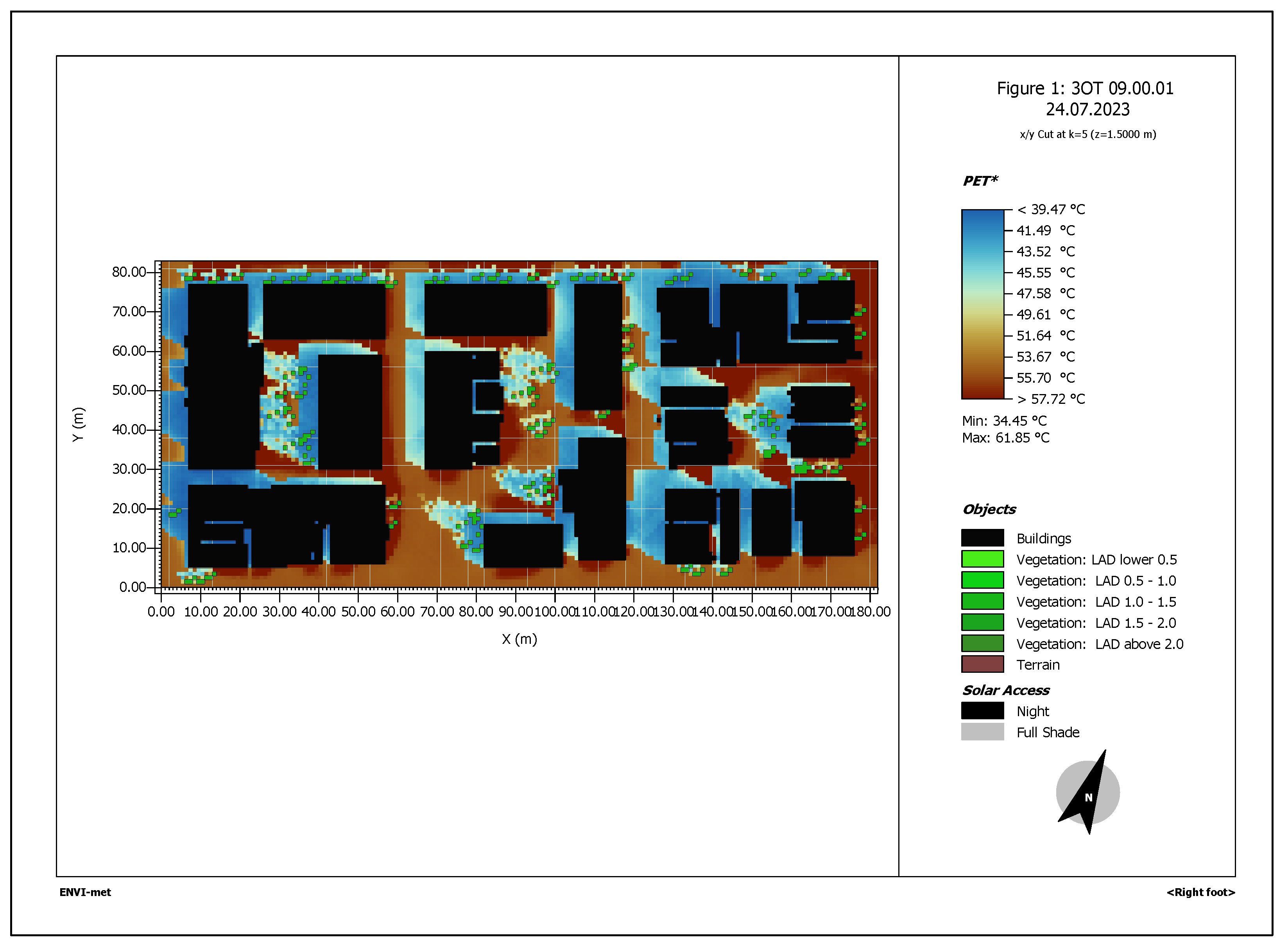

3.1. Baseline Scenario—9 a.m.

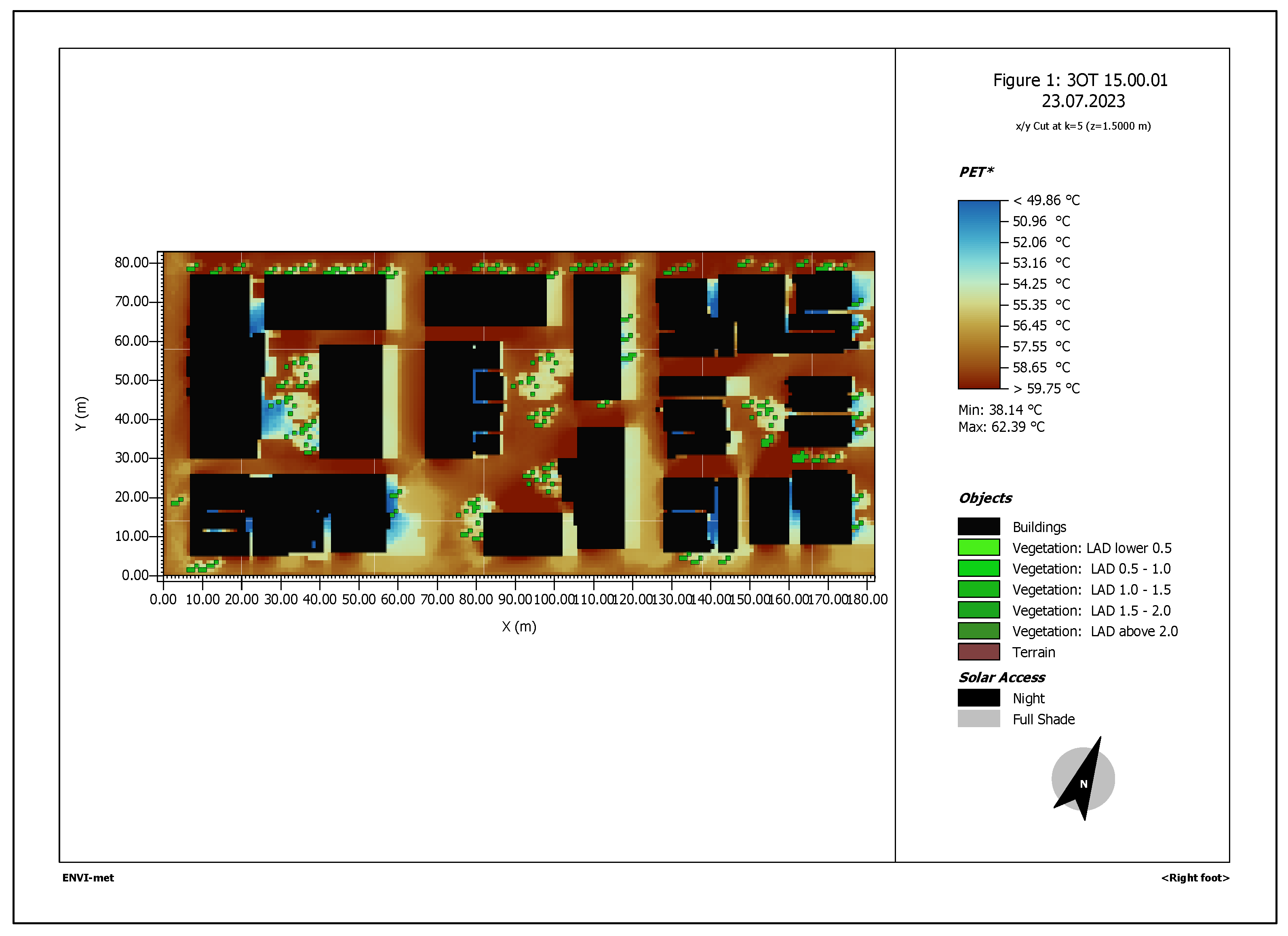

3.2. Baseline Scenario, 3 p.m.

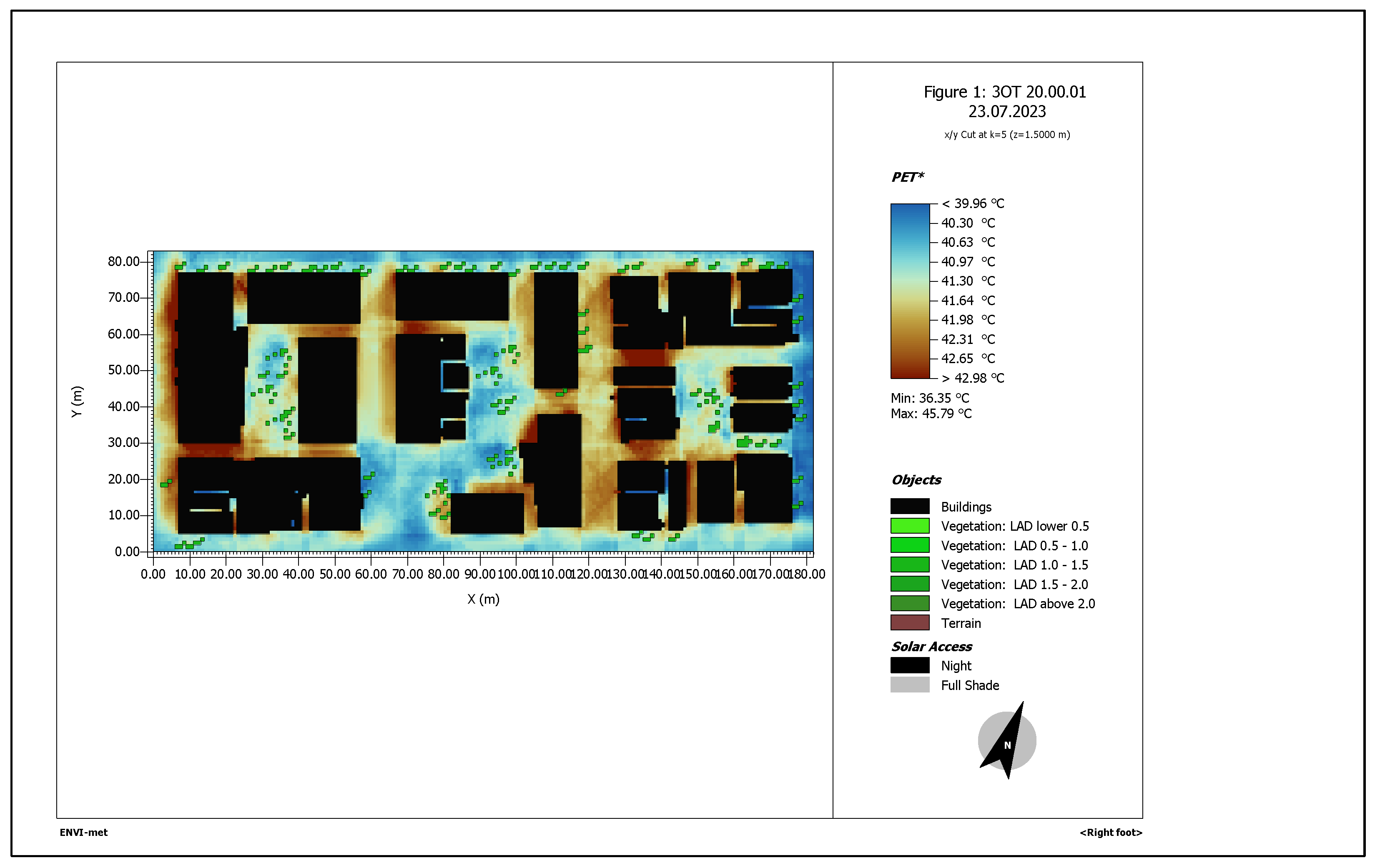

3.3. Baseline Scenario, 8 p.m.

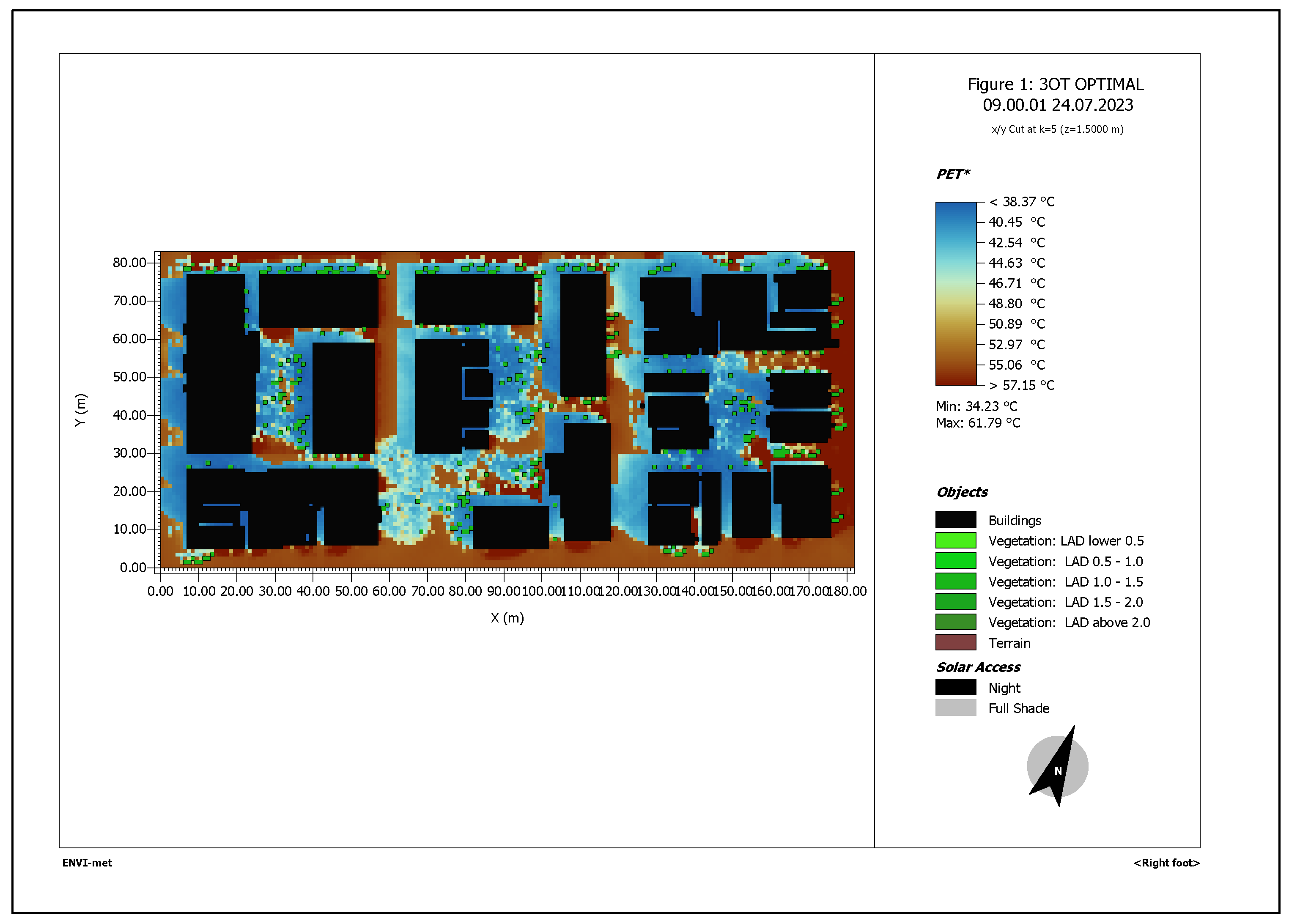

3.4. Optimal Scenario—9 a.m.

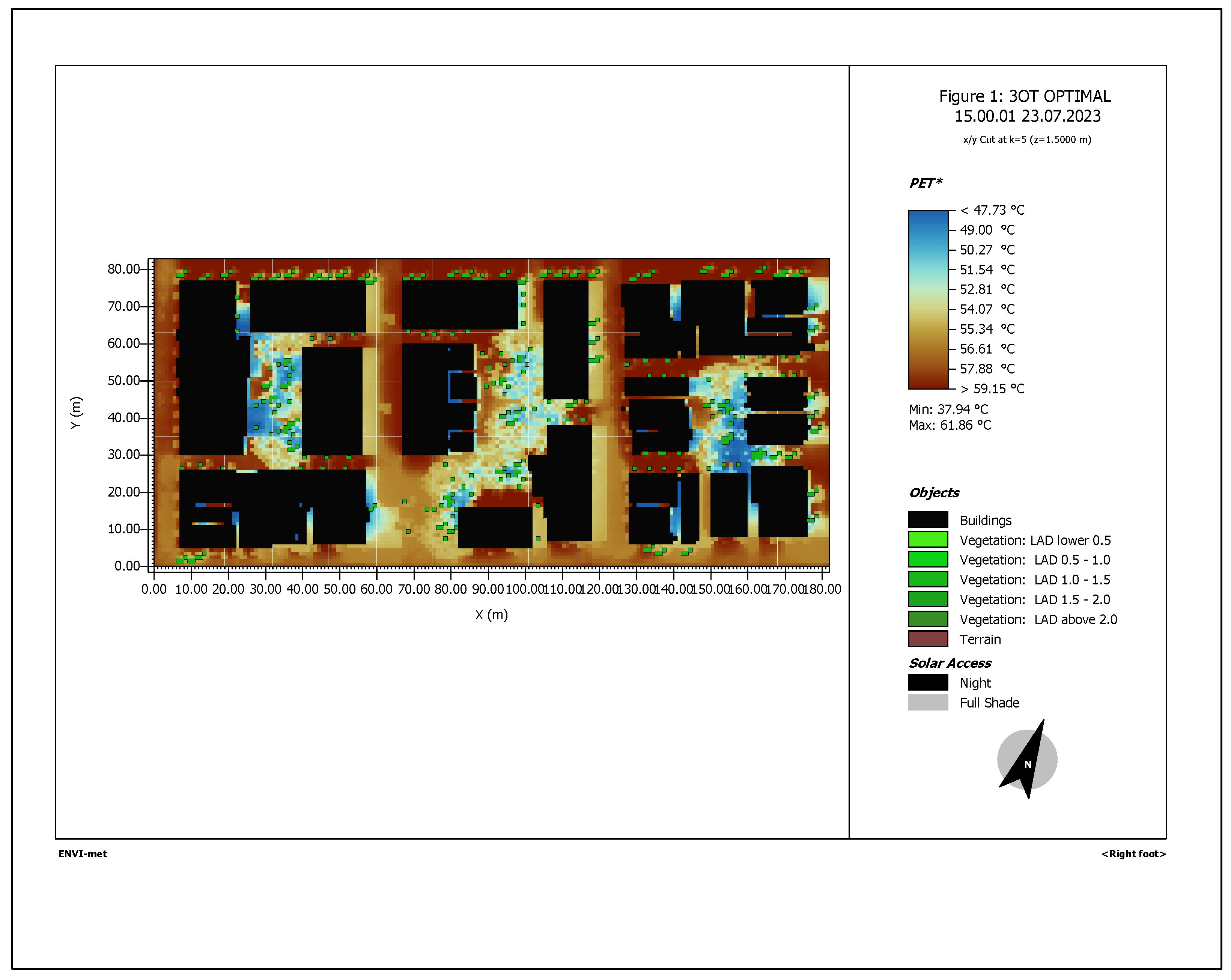

3.5. Optimal Scenario—3 p.m.

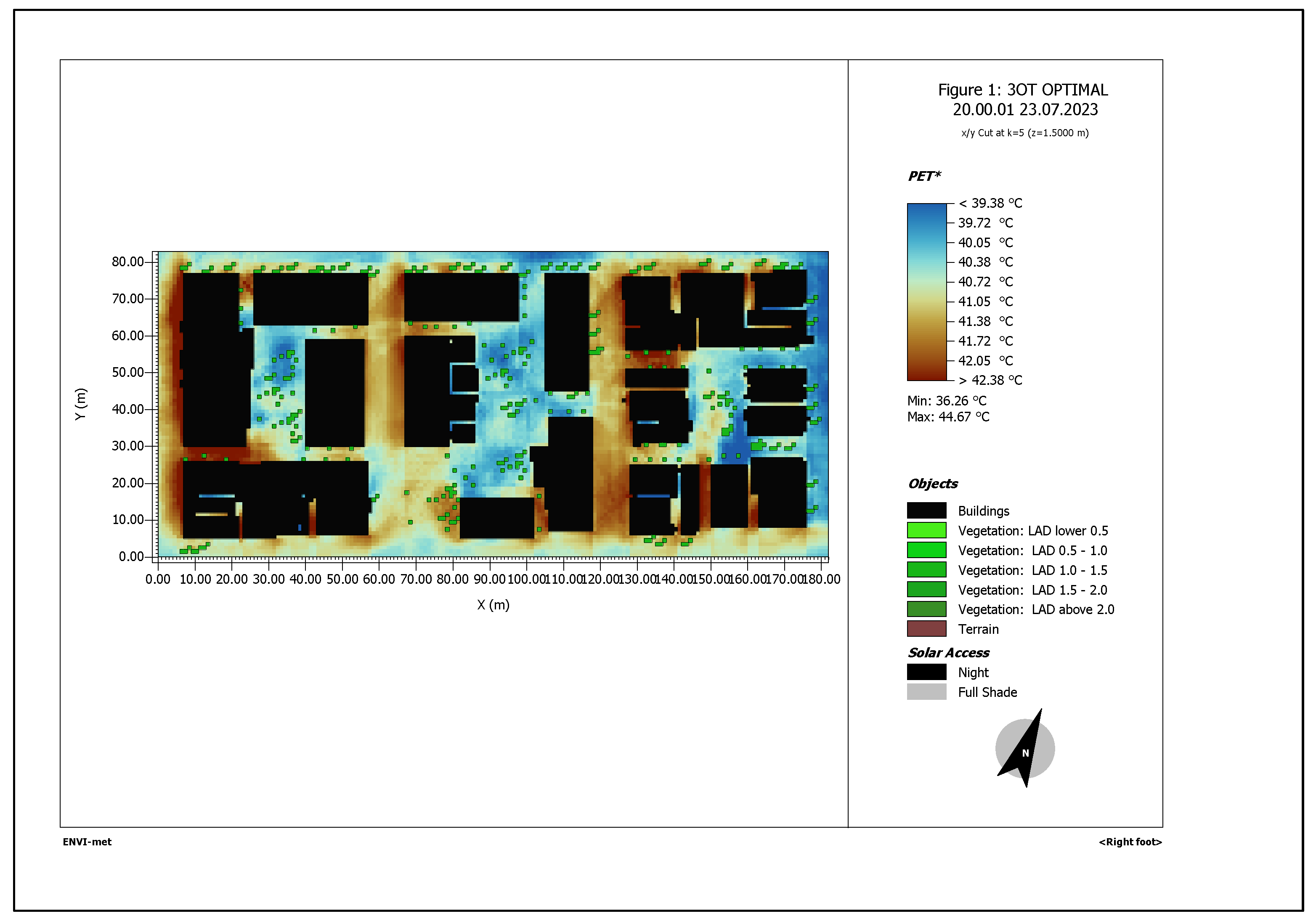

3.6. Optimal Scenario—8 p.m..

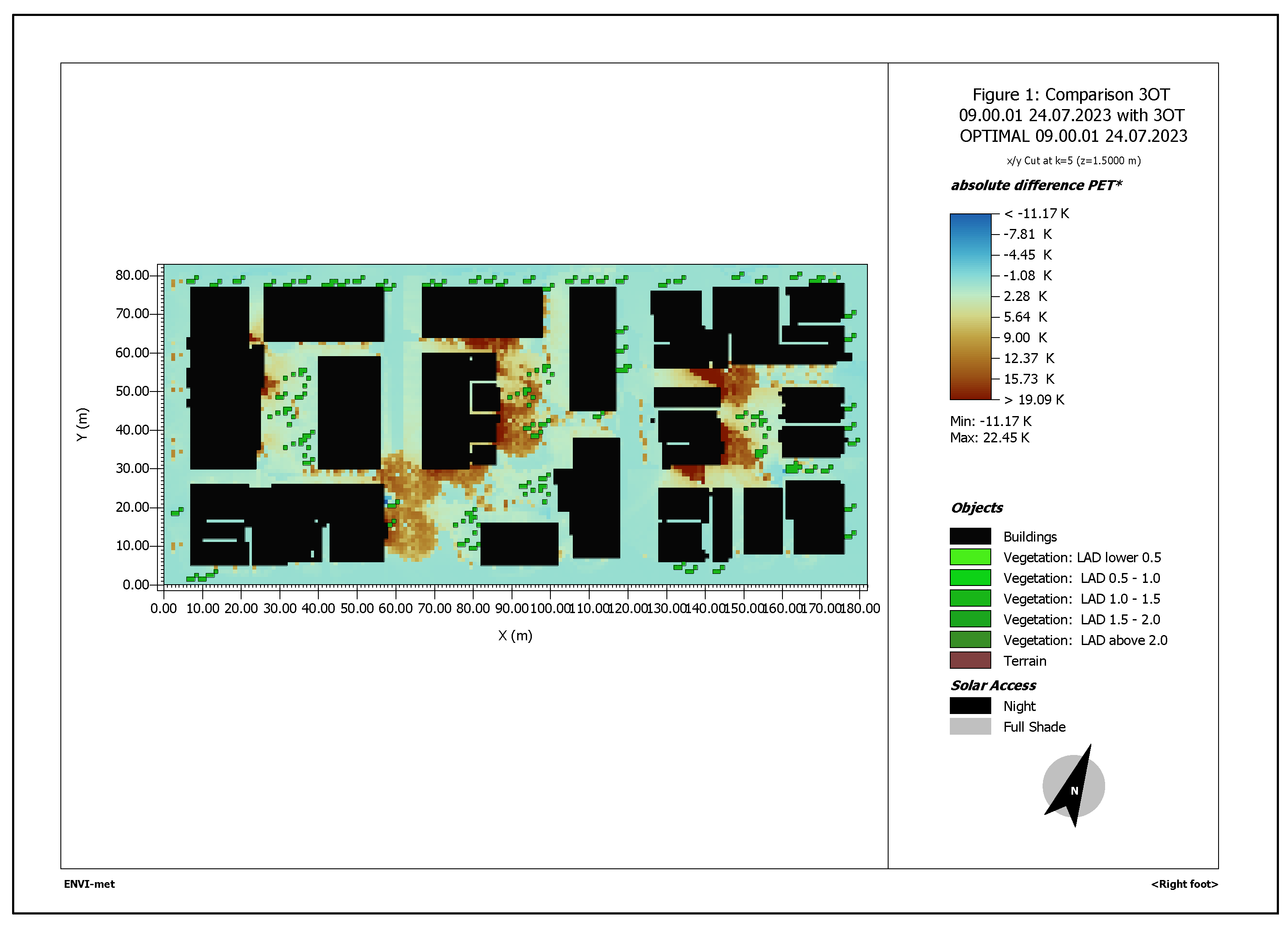

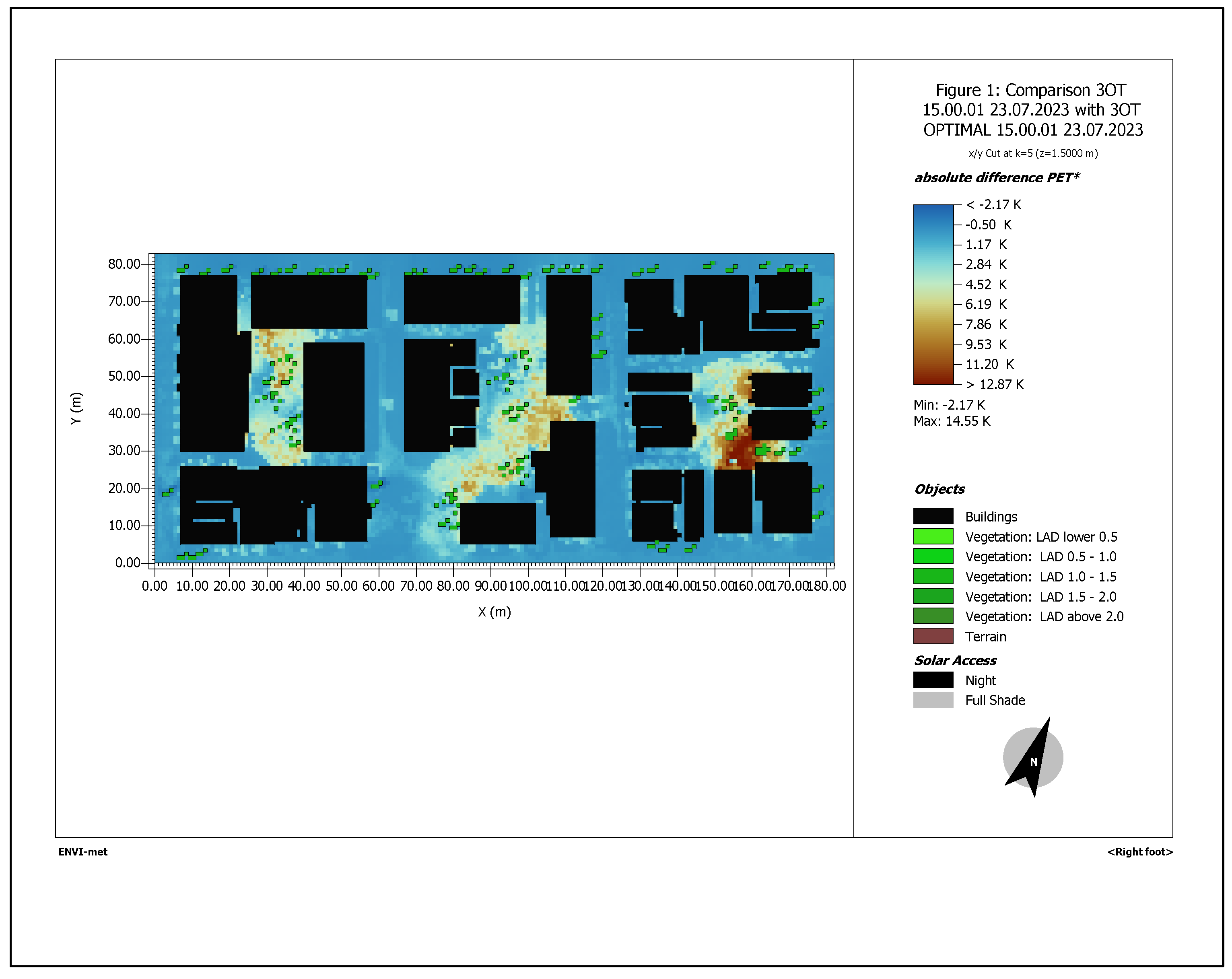

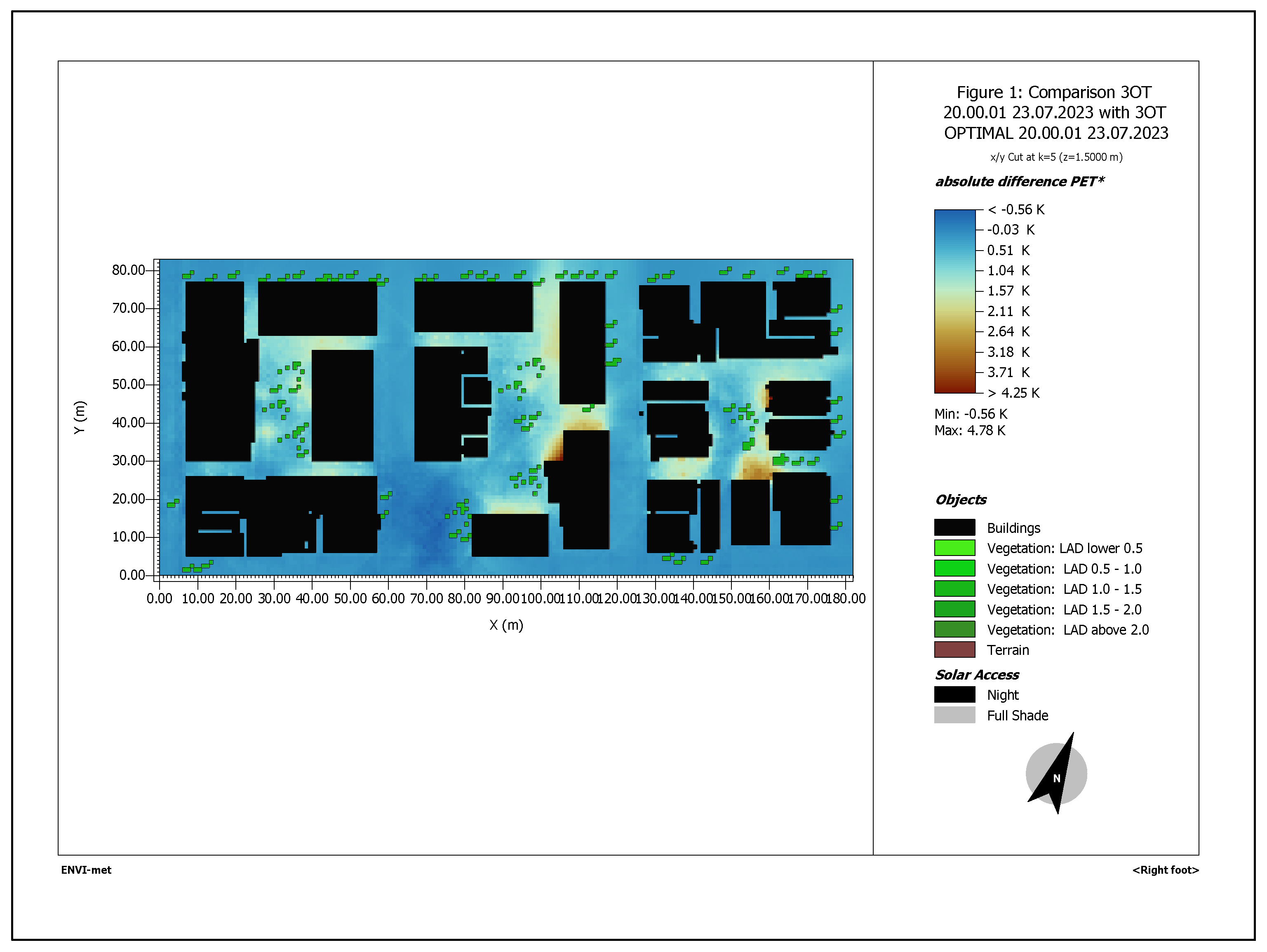

3.7. Comparison Between Baseline and Optimal Scenarios

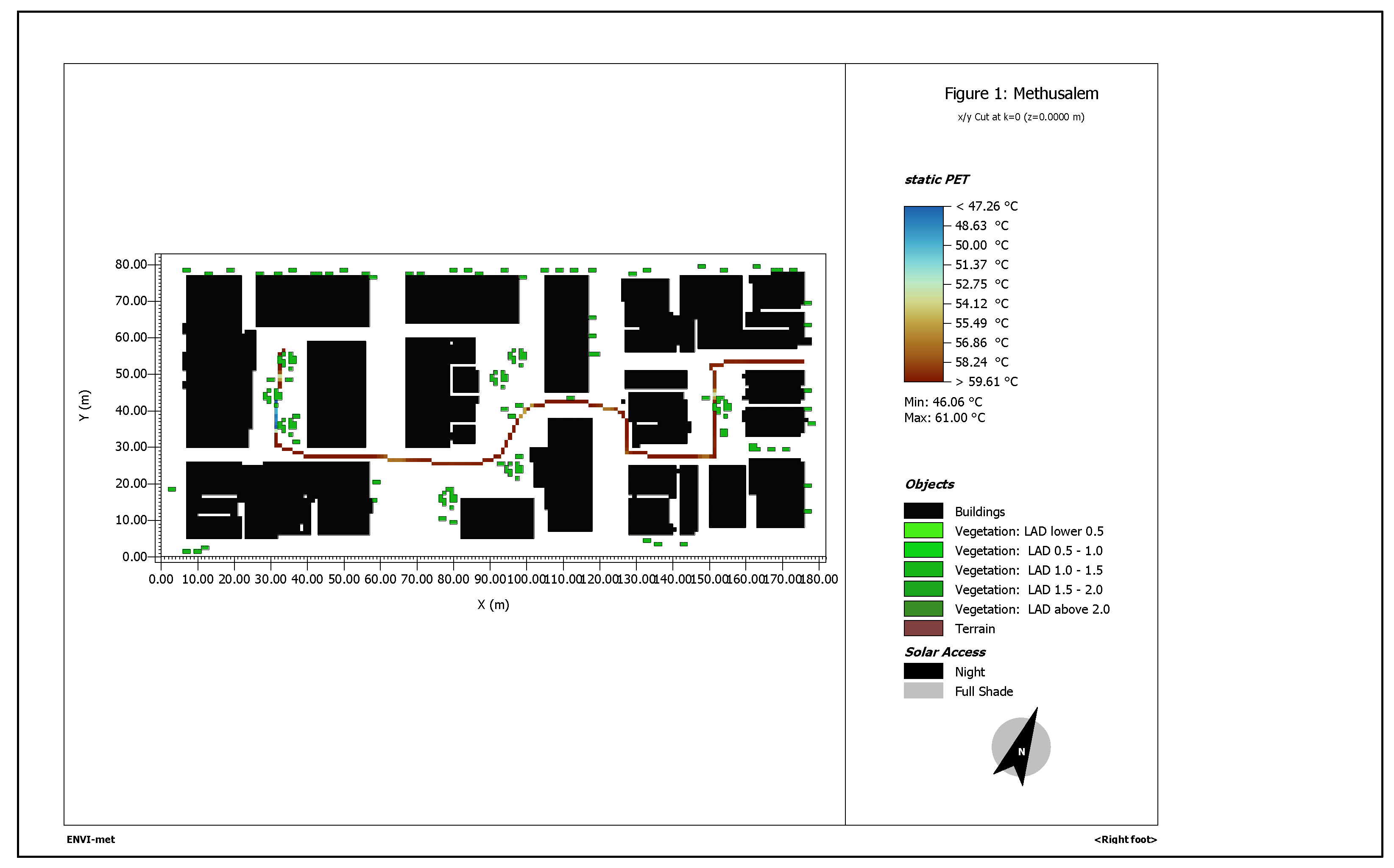

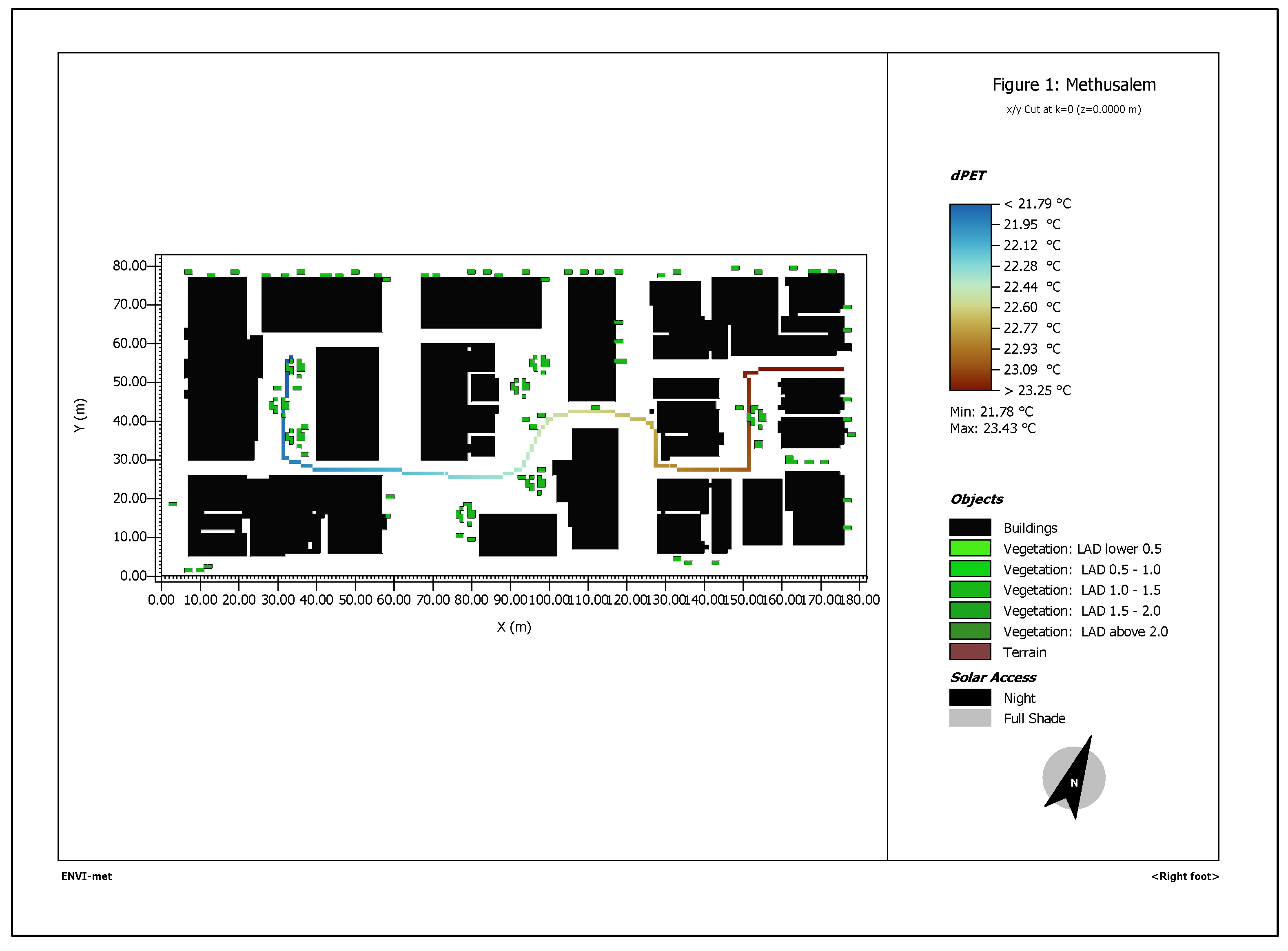

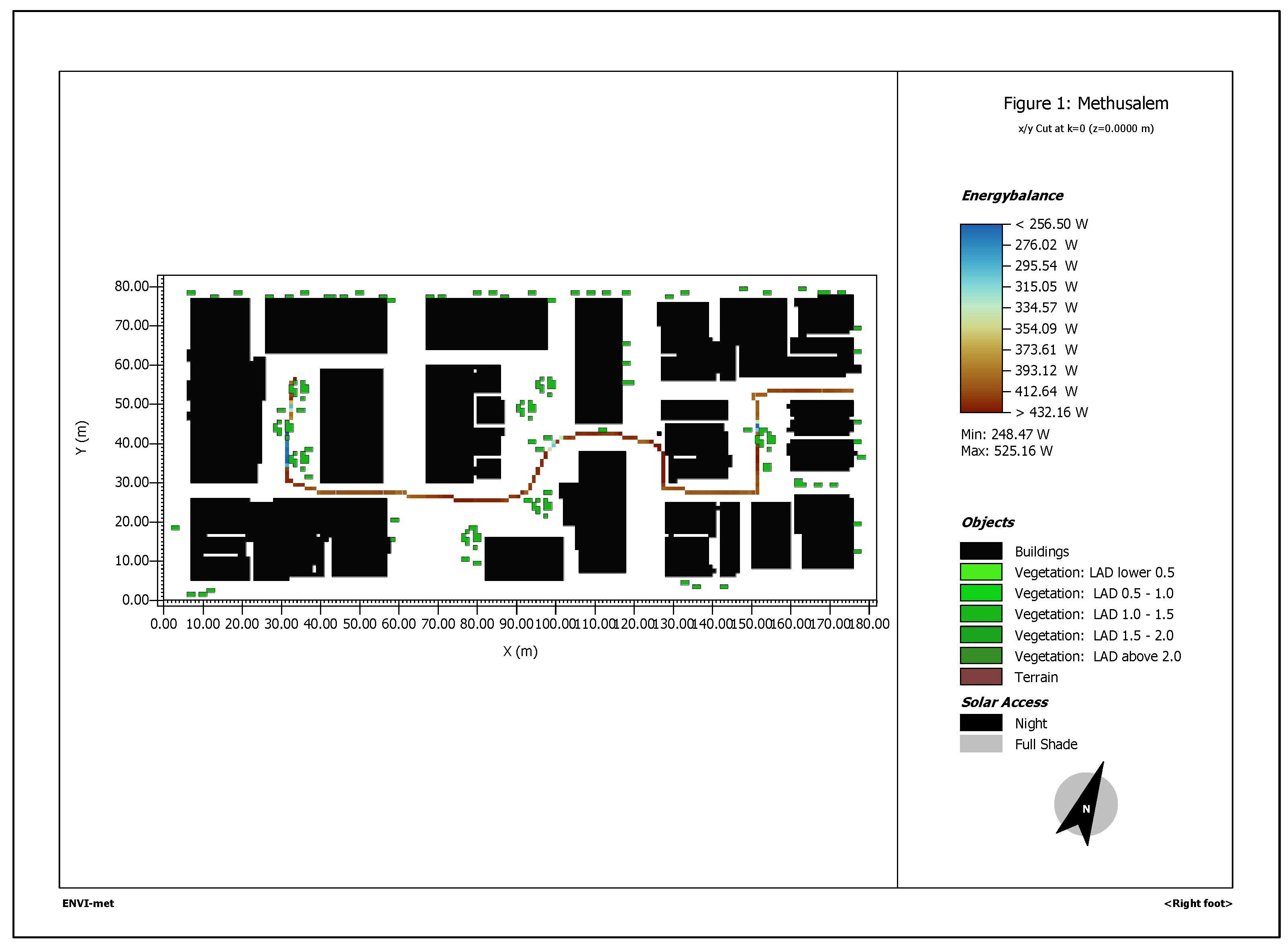

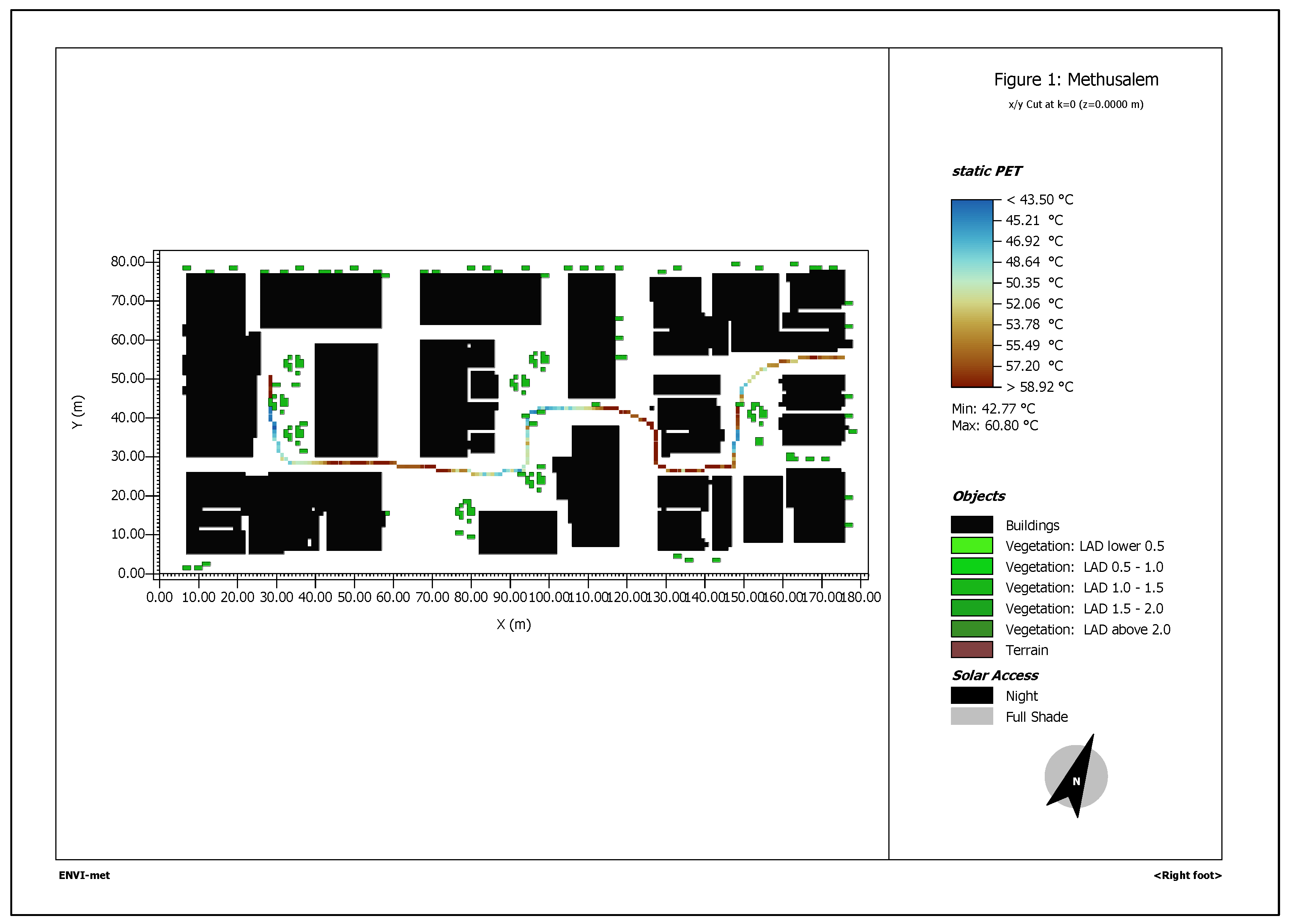

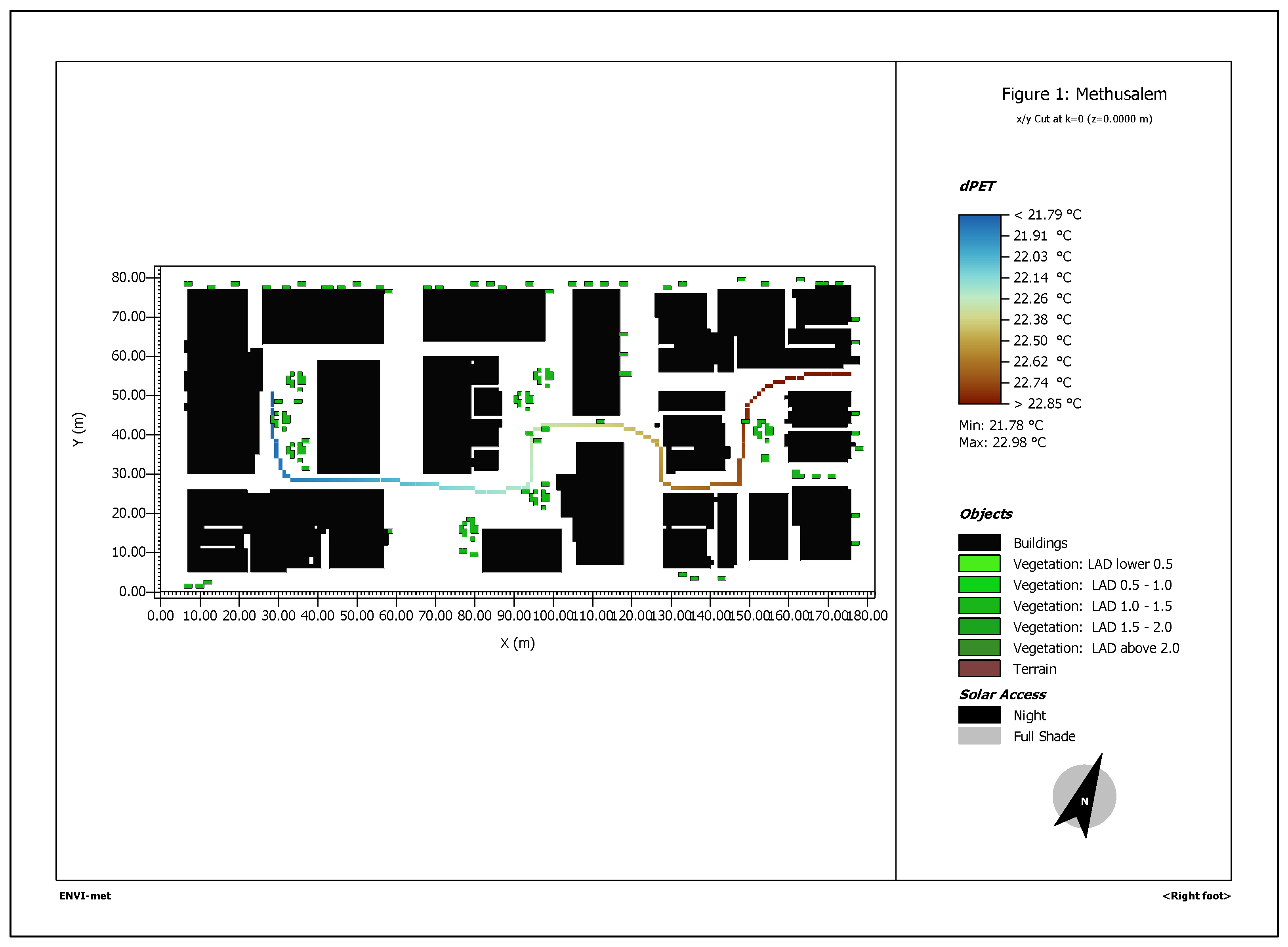

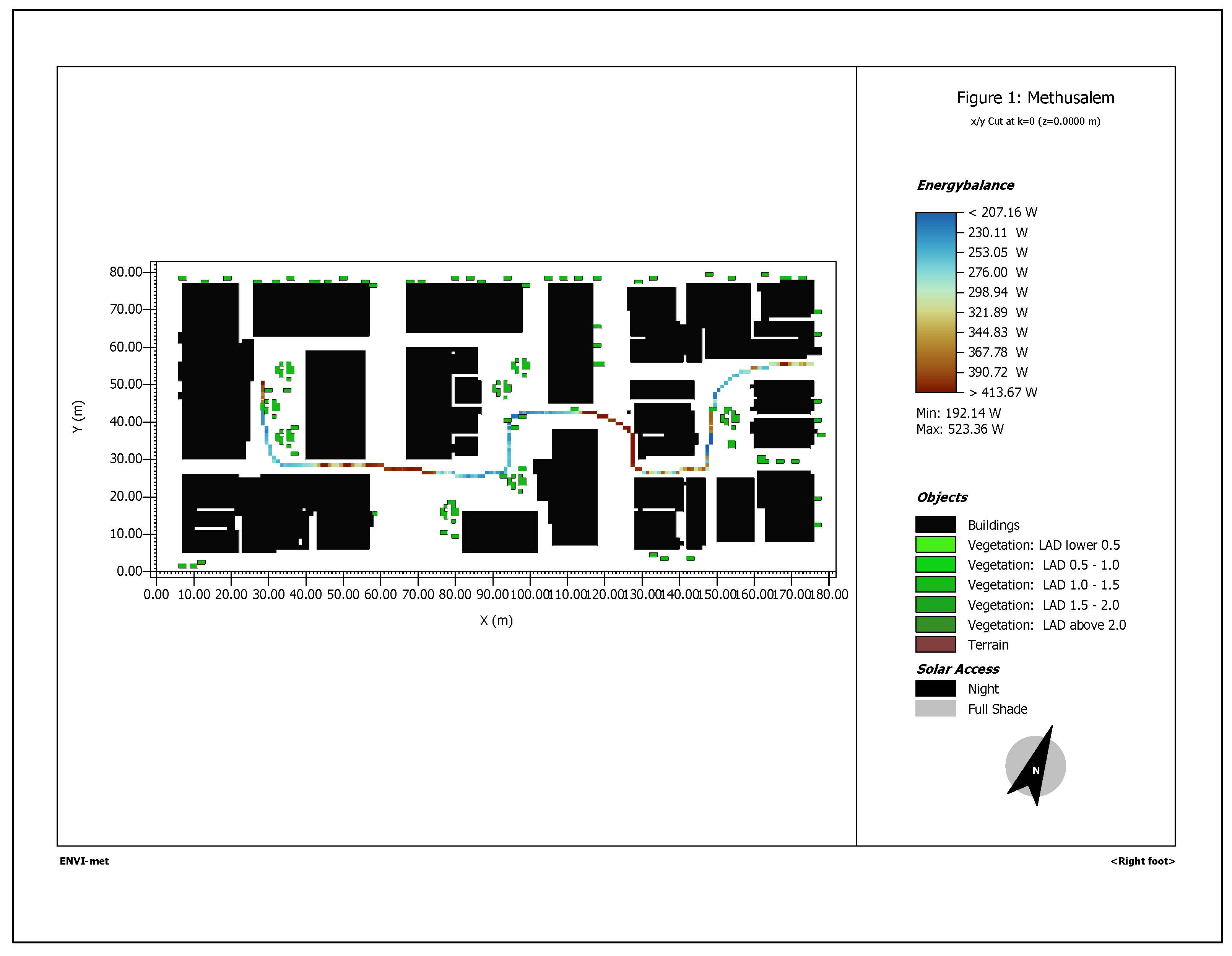

3.8. Further Analysis of Peak Temperature Hours. Dynamic Comfort, Dpet, Static PET, and Energy Balance. Comparison Between Baseline and Optimal Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Melas, E.; Varelidis, G. Spatial Distribution and Quality of Urban Public Spaces in the Attica Region (Greece) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey-Based Analysis. Urban Sci 2023;8:2. [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Varelidis, G. Assessing Urban Public Space Quality: A Short Questionnaire Approach. Urban Sci 2025;9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Z. Change of Residents’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Urban Green Space Pre- and Post- COVID-19 Pandemic. Land 2022;11:1051. [CrossRef]

- Eady, A.; Dreyer, B.; Hey, B.; Riemer, M.; Wilson, A. Reducing the risks of extreme heat for seniors: Communicating risks and building resilience. Heal Promot Chronic Dis Prev Canada 2020;40:215–24. [CrossRef]

- Tousi, E.; Mela, A. Supralocal Role of medium to large scale Urban Parks, in Attica Greece. Issues of meso car dependence during the Covid-19 Pandemic. (pending publication 2023-2024). J Sustain Archit Civ Eng 2024;2:201–15. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.T.; Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. Encycl Environ Heal 2019;80:465–9. [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.; Cambra, P.; Gonçalves, A.B. Measuring walkability for distinct pedestrian groups with a participatory assessment method: A case study in Lisbon. Landsc Urban Plan 2017;157:282–96. [CrossRef]

- Zysk, E.; Zalewska, K. The Methodology for Assessing the 15 Minute Age-Friendly Walkability (AFW) of Urban Public Spaces. Sustain 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E. Safe and Inclusive Urban Public Spaces: A Gendered Perspective. The Case of Attica ’s Public Spaces During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. J Sustain Archit Civ Eng 2023;2:5–14. [CrossRef]

- Sobouti, H.; Alavi, P. Evaluation of Quality Elderly of Public Open Spaces for the Case Study : (sheet-e- Bazaar in Zanjan) 2017;7:47–56.

- Ebi KL, Vanos J, Baldwin JW, Bell JE, Hondula DM, Errett NA, et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu Rev Public Health 2020;42:293–315. [CrossRef]

- Kovats, R.S.; Hajat, S. Heat stress and public health: A critical review. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:41–55. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Ng, E.Y.Y.; Xu, Y. Urban heat islands in Hong Kong: statistical modeling and trend detection. Nat Hazards 2016;83:885–907. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.P.; Yardley, J.; Brown, C.; Sigal, R.J.; Jay, O. Heat stress in older individuals and patients with common chronic diseases. C Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:1053–60. [CrossRef]

- Kenney, W.L.; Craighead, D.H.; Alexander, L.M. Heat waves aging and human cardiovascular health. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1891–9. [CrossRef]

- Yardley, J.E.; Stapleton, J.M.; Sigal, R.J.; Kenny, G.P. Do heat events pose a greater health risk for individuals with type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Technol Ther 2013;15:520–9. [CrossRef]

- Wee J, Tan XR, Gunther SH, Ihsan M, Leow MKS, Tan DSY, et al. Effects of Medications on Heat Loss Capacity in Chronic Disease Patients: Health Implications Amidst Global Warming. Pharmacol Rev 2023;75:1140–66. [CrossRef]

- Malmquist, A.; Hjerpe, M.; Glaas, E.; Karlsson, H.; Lassi, T. Elderly People’s Perceptions of Heat Stress and Adaptation to Heat: An Interview Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E.; Koukoufikis, G. The persistence of energy poverty in the EU. vol. 41. 2024.

- Joshi, K.; Khan, A.; Anand, P.; Sen, J. Understanding the synergy between heat waves and the built environment: a three-decade systematic review informing policies for mitigating urban heat island in cities. Sustain Earth Rev 2024;7. [CrossRef]

- Hien, W.N.; Kardinaljusuf, S.; Samsudin, R.; Eliza, A.; Ignatius, M. A climatic responsive urban planning model for high density city: Singapore’s commercial district. Int J Sustain Build Technol Urban Dev 2011;2:323–30. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Milan, B.; Creutzig, F. Reducing urban heat wave risk in the 21st century. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2015;14:221–31. [CrossRef]

- Ingole, V.; Sheridan, S.C.; Juvekar, S.; Achebak, H.; Moraga, P. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature in Pune city, India: A time series analysis from 2004 to 2012. Environ Res 2022;204:112304. [CrossRef]

- Kent, E. Leading urban change with people powered public spaces. The history, and new directions, of the Placemaking movement. J Public Sp 2019;4:127–34. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Piloting Nature-based Solutions for Urban Cooling. ESMAP 2022.

- Almeida, M.F. Age-Friendly Walkable Urban Spaces : A Participatory Assessment Tool Age-Friendly Walkable Urban Spaces : A Participatory. J Hous Elderly 2017;30:396–411. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R. Mapping neighbourhood outdoor activities: space, time, gender and age. J Urban Des 2019;24:715–37. [CrossRef]

- Tousi, E.; Tseliou, A.; Mela, A.; Sinou, M.; Kanetaki, Z. Exploring Thermal Discomfort during Mediterranean Heatwaves through Softscape and Hardscape ENVI-Met Simulation Scenarios. Sustainability 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, F.; Cueva, A.P.; Valcuende, M.; Matzarakis, A. Research on ecological design to enhance comfort in open spaces of a city (Valencia, Spain). Utility of the physiological equivalent temperature (PET). Ecol Eng 2013;57:27–39. [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A.; Amelung, B. Seasonal Forecasts, Climatic Change and Human Health. Seas Forecast Clim Chang Hum Heal 2008. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.S.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Matzarakis, A. The application of the physiologically equivalent temperature to determine impacts of locally defined extreme heat events within vulnerable dwellings during the 2020 summer in Ankara. Sustain Cities Soc 2022;81:103833. [CrossRef]

- Deb, C.; Alur, R. The significance of Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) in outdoor thermal comfort studies. Chirag Deb et Al / Int J Eng Sci Technol 2010;2:2825–8.

- Galluzo, L.; Borin, A. Post-pandemic Scenarios and Design Strategies for Public Space Transformation. Inmaterial 2021;6:72–87. [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, B.; Meier, F.; Hoelscher, M.T.; Scherer, D. Evaluating the effects of façade greening on human bioclimate in a complex Urban environment. Adv Meteorol 2015;2015. [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, B.; Milošević, D.; Manavvi, S. Review of user-friendly models to improve the urban micro-climate. Atmosphere (Basel) 2021;12:1–22. [CrossRef]

- Gatto E, Ippolito F, Rispoli G, Carlo OS, Santiago JL, Aarrevaara E, et al. Analysis of urban greening scenarios for improving outdoor thermal comfort in neighbourhoods of lecce (Southern Italy). Climate 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Tseliou, A.; Koletsis, I.; Pantavou, K.; Thoma, E.; Lykoudis, S.; Tsiros, I.X. Evaluating the effects of different mitigation strategies on the warm thermal environment of an urban square in Athens, Greece. Urban Clim 2022;44:101217. [CrossRef]

- Elwy, I.; Ibrahim, Y.; Fahmy, M.; Mahdy, M. Outdoor microclimatic validation for hybrid simulation workflow in hot arid climates against ENVI-met and field measurements. Energy Procedia, vol. 153, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Steffan, I.T.; De Salvatore, A.; Matone, F. Improving Accessibility and Usability in the Built Environment. Case Study: Guide Lines by the Lombardy Region, Italy. Stud Health Technol Inform 2022;297:280–7. [CrossRef]

- Noël, C.; Rodriguez-Loureiro, L.; Vanroelen, C.; Gadeyne, S. Perceived Health Impact and Usage of Public Green Spaces in Brussels’ Metropolitan Area During the COVID-19 Epidemic. Front Sustain Cities 2021;3:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Modern compact cities: How much greenery do we need? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Hughes, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Vasenev, V.; Dovletyarova, E. Human dimensions of urban blue and green infrastructure during a pandemic. Case study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia). Sustain 2021;13. [CrossRef]

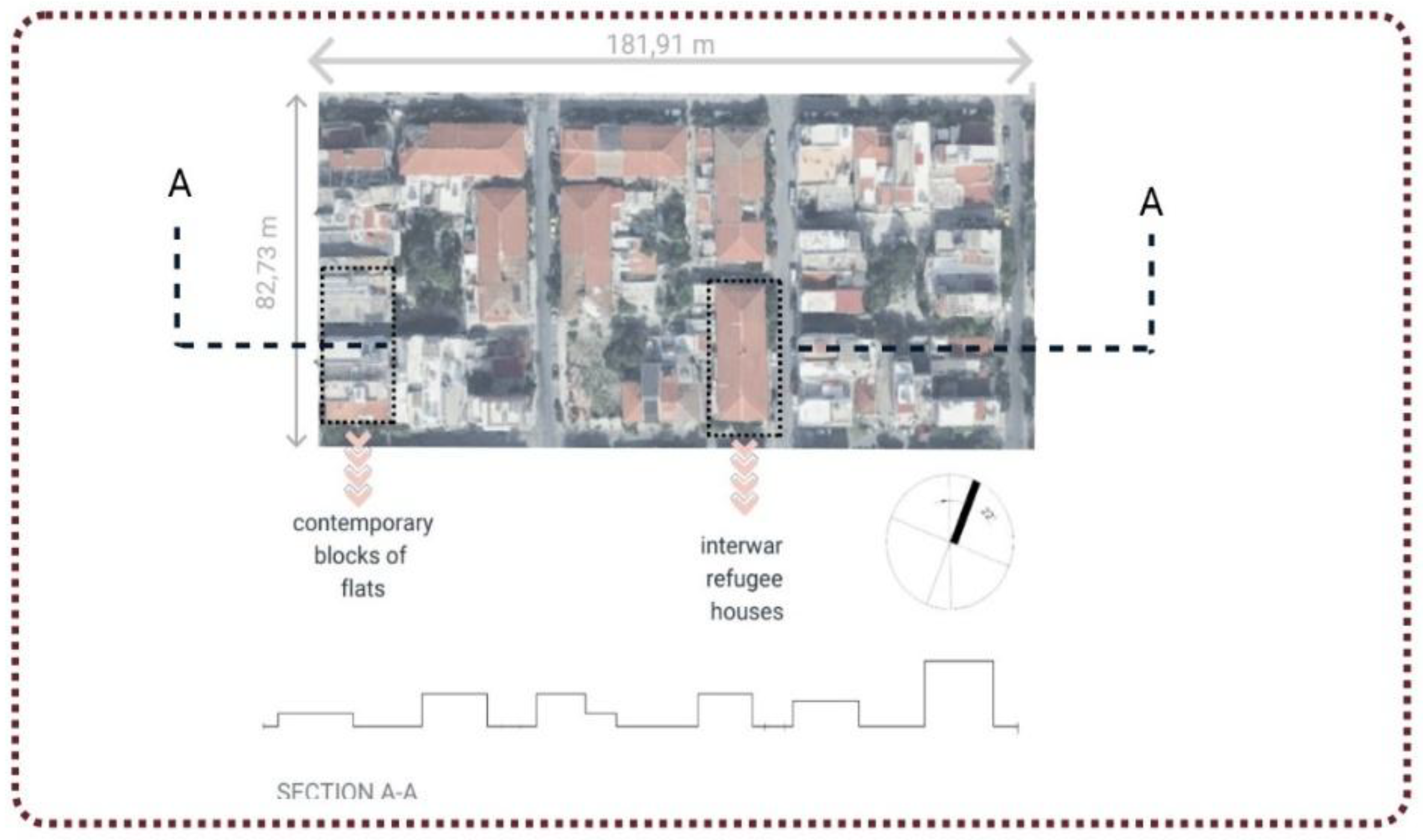

- Tousi, E.; Sinou, M.; Perouli, A. Urban Acupuncture As a Method of Open Space Regeneration in Greek Ex-refugee Areas. The Case of Nikea, Piraeus. J Sustain Archit Civ Eng 2022;30:5–18. [CrossRef]

- Toussi Evgenia. Initial planning and current situation of refugee housing and outdoor public spaces in the post-refugee urban settlement of Nikea in Attica. Athens Soc Atlas 2024. https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/refugee-housing-and-outdoor-public-spaces-in-nikea/.

- Tousi, E.; Mela, A.; Tseliou, A.; Theofili, E.; Varelidis, G. Elements of urban design to ameliorate urban heat island. The Case of. Int. Conf. Chang. Cities VI Spat. Des. Landscape, Herit. Socio-economic Dimens., 2024, p. 5765.

- Tousi, E. Changing Socio-Spatial Identities. The case of the Asia Minor Refugee Urban Settlements in the Greater Athens-Piraeus Region in Greece. J Sustain Archit Civ Eng 2024;35:153–67. [CrossRef]

- Tseliou, A.; Tsiros, I.X. Modeling urban microclimate to ameliorate thermal sensation conditions in outdoor areas in Athens (Greece). Build Simul 2016;9:251–67. [CrossRef]

- Elmarakby, E.; Elkadi, H. Prioritising urban heat island mitigation interventions: Mapping a heat risk index. Sci Total Environ 2024;948:174927. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Zhang, L.; Chang, Q. Nature-based solutions for urban heat mitigation in historical and cultural block: The case of Beijing Old City. Build Environ 2022;225:109600. [CrossRef]

- Hayes AT, Jandaghian Z, Lacasse MA, Gaur A, Lu H, Laouadi A, et al. Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) to Mitigate Urban Heat Island (UHI) Effects in Canadian Cities. Buildings 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Keeffe, G.; Mariotti, J. Nature-Based Solutions for Cooling in High-Density Neighbourhoods in Shenzhen: A Case Study of Baishizhou. Sustain 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Sani, G.M.D.; Giachetta, A.; Perini, K. Nature-based solutions: Thermal comfort improvement and psychological wellbeing, a case study in Genoa, Italy. Sustain 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Sassenou, L.N.; Olivieri, L. Potential of Nature-Based Solutions to Diminish Urban Heat Island Effects and Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Summer: Case Study of Matadero Madrid. Sustain 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Sylliris, N.; Papagiannakis, A.; Vartholomaios, A. Improving the Climate Resilience of Urban Road Networks: A Simulation of Microclimate and Air Quality Interventions in a Typology of Streets in Thessaloniki Historic Centre. Land 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Laureti, F.; Martinelli, L.; Battisti, A. Assessment and mitigation strategies to counteract overheating in urban historical areas in Rome. Climate 2018;6. [CrossRef]

- Tseliou A, Koletsis I, Thoma E, Proutsos N, Lykoudis S, Pantavou K, et al. A model-based study on the impact of different tree configurations on the thermal conditions of an urban square. Proc 17th Int Conf Environ Sci Technol 2022;17:5–9. [CrossRef]

- Koletsis, I.; Tseliou, A.; Lykoudis, S.; Pantavou, K.; Tsiros, I. Testing and validation of ENVI-met simulations based on in-situ micrometeorological measurements: the case of Syntagma square, Athens, Greece. Proc 16th Int Conf Environ Sci Technol 2022;16:1–2. [CrossRef]

- Louafi, S.; Abdou, S. Vegetation Effects on Urban Street Microclimate and Thermal Comfort during Overheated Period under Hot and Dry Climatic Conditions. J New Technol Mater 2016;6:87–94. [CrossRef]

- Gatto E, Ippolito F, Rispoli G, Carlo OS, Santiago JL, Aarrevaara E, et al. Analysis of urban greening scenarios for improving outdoor thermal comfort in neighbourhoods of lecce (Southern Italy). Climate 2021;9:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Pantavou, K.; Santamouris, M.; Asimakopoulos, D.; Theoharatos, G. Empirical calibration of thermal indices in an urban outdoor Mediterranean environment. Build Environ 2014;80:283–92. [CrossRef]

- Tsiros, I.X.; Hoffman, M.E. Thermal and comfort conditions in a semi-closed rear wooded garden and its adjacent semi-open spaces in a mediterranean climate (athens) during summer. Archit Sci Rev 2014;57:63–82. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, A.; Laureti, F.; Zinzi, M.; Volpicelli, G. Climate mitigation and adaptation strategies for roofs and pavements: A case study at Sapienza University Campus. Sustain 2018;10. [CrossRef]

- McKenna ZJ, Foster J, Atkins WC, Belval LN, Watso JC, Jarrard CP, et al. Age alters the thermoregulatory responses to extreme heat exposure with accompanying activities of daily living. J Appl Physiol 2023;135:445–55. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.M.G.; Morley, J.E. Invited review: Aging and energy balance. J Appl Physiol 2003;95:1728–36. [CrossRef]

- Tyrovolas S, Haro JM, Mariolis A, Piscopo S, Valacchi G, Makri K, et al. The Role of Energy Balance in Successful Aging among Elderly Individuals: The Multinational MEDIS Study. J Aging Health 2015;27:1375–91. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).