Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Problem Statement

1.2. Urban Heat Mitigation Technologies

- Small Water Paths: These passive cooling solutions use water channels in urban parks and public spaces to cool surrounding air through evaporative effects.

1.3. Research Objectives

- Evaluate the temperature reduction capabilities of each technology in urban settings.

- Compare the effectiveness of active cooling technologies (cooling fog) with that of passive solutions (cool roofs, shading structures, and small water paths).

- Provide actionable insights for urban planners and policymakers on the deployment of these technologies to protect vulnerable populations from extreme heat.

1.4. Significance of the Study

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Urban Heat Island (UHI) Effect and Climate Change

2.2. Urban Heat Island Effect

2.3. Climate Change and Heat Stress

2.4. Principles and Effects of Urban Heat Mitigation Technologies

- Cooling Fog Systems: This technology disperses fine water droplets into the air, which cools the surrounding environment as they evaporate. Cooling fog is particularly effective in public spaces, offering immediate temperature reduction in high-traffic outdoor areas.

- Shading Structures: Shading structures block direct sunlight and reduce the temperature in the shaded areas. These structures are commonly installed in parks, playgrounds, bus stops, and other public spaces to reduce the heat stress. Studies have shown that shading can significantly lower the ambient air temperature and perceived discomfort.

- Cool Roofs (Reflective Paint): Reflective coatings applied to building exteriors reflect solar radiation, reducing surface and indoor temperatures. This technology is especially effective in lowering the energy demand for cooling during summer and mitigating UHI effects.

- Small water paths: These small artificial water channels help to absorb and dissipate heat from the surrounding environment. They provide cooling in urban parks and public spaces and offer psychological benefits by creating tranquil, pleasant environments for rest and relaxation.

2.5. Review of Previous Studies

- Shading Structures: Shading structures are well known for their ability to reduce solar exposure, but there is relatively little research quantifying their specific temperature reduction effects. Studies suggest that the material and design of the shading structure significantly impact its effectiveness. For instance, natural tree shade can reduce surrounding air temperatures by up to 5°C, while artificial shading structures demonstrate similar temperature reductions. [27,28].

- Cool Roofs: Cool roofs have been extensively studied and are shown to reduce surface temperatures by up to 15°C by reflecting solar radiation, which significantly lowers the amount of heat absorbed by the building. This reduction in surface temperature leads to a decrease in energy demand for cooling, particularly during summer months[26,29].

- Cooling Fog: Cooling fog systems are effective in lowering ambient temperatures, particularly during heatwaves, with reductions of 4°C to 6°C reported in various studies. However, here are concerns regarding water consumption, prompting further research into optimizing these systems to balance cooling efficiency with resource conservation[30,31].

- Waterway Shelters: Water features such as small water paths consistently reduce both surface and air temperatures by 2°C to 4°C through evaporative cooling. These features are particularly effective in parks and outdoor spaces, providing not only passive cooling but also aesthetic and psychological benefits. However, challenges such as maintenance and ensuring that the system operates effectively under all conditions have been noted[32,33].

2.6. Significance of the Study

- Integrated Approach: Unlike previous research that focused on individual technologies, this study evaluated multiple technologies in combination, providing a holistic analysis of their collective impact on urban heat mitigation.

- Field-tested Validation: The field tests conducted in collaboration with the Korean Ministry of Environment over multiple years (2021–2023) offer valuable practical data. This data demonstrates how these technologies perform in real-world urban settings, offering insights that can inform future urban planning and policy efforts.

- Policy Implications: The findings from this study provide actionable insights for local governments in Korea and globally, particularly those aiming to implement heat mitigation strategies to protect vulnerable populations. This study sets a benchmark for other local governments and provides a reference for large-scale heat-mitigation initiatives that require significant investment, energy, and time.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of Technologies Evaluated

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.2.1. Cool Roof (Reflective Paint) Experimentation

- ■

- H1: Cool roof and cool wall applied.

- ■

- H2: Cool wall only.

- ■

- H3: Control site (non-applied).

- ■

- Surface temperatures of rooftops and walls, indoor temperatures, and ambient air temperatures above 1.5M from the surface were measured using T&D TR-71wf Data logger temperature sensors from August 27 to September 1, 2021.

3.2.2. Cooling Fog Experimentation in Yechun-gun

- Objective: To assess the cooling effects of a cooling fog system installed in a public outdoor space specifically designed to improve thermal comfort for vulnerable populations and high-traffic areas such as playgrounds.

-

Study Location: A cooling fog system was deployed at a children's playground in Yechun-gun (also spelled Yecheon-gun), located in the northern part of Gyeongsangbuk-do province, South Korea. This region experiences a temperate climate with four distinct seasons (Dwa, according to the Köppen climate classification), with hot, humid summers and cold winters.In recent years, climate change has contributed to a noticeable rise in the frequency and intensity of heatwaves in this region, especially during the summer months, making the area increasingly susceptible to heat-related risks. Yechun-gun is primarily a rural area with a significant aging population, which adds to the vulnerability of the region in terms of climate change adaptation. Elderly residents are particularly at risk from extreme heat, as they are more sensitive to heat stress. The rise in temperatures due to climate change has increased energy demand, particularly for cooling, and has also heightened health risks for both elderly populations and children. These conditions make Yechun-gun a strategic location to deploy cooling technologies such as cooling fog systems, which are designed to mitigate heat stress in public spaces, especially during peak summer months. The implementation of cooling fog systems is particularly crucial in regions like Yechun-gun, where local populations are heavily reliant on outdoor public spaces for daily activities, and where public health infrastructures may not be as readily equipped to handle the intensifying climate conditions[35,36,37].

| Section | Site | Address | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 |  |

13, Jinyeongsanbok-ro 72beon-gil, Jinyeong-eup, Gimhae-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, South Korea | Coolwall+roof |

| H2 | 9, Jinyeongsanbok-ro 72beon-gil, Jinyeong-eup, Gimhae-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, South Korea | Coolwall | |

| H3 | 4-1, Jinyeongsanbok-ro 72beon-gil, Jinyeong-eup, Gimhae-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, South Korea | Non applied |

- •

- Experimental Design:

- ■

-

Monitoring Equipment: IoT temperature sensors were placed at different distances from the fog system and sunny zone 9m to measure the cooling effect.

- ■

- Ecowitt WS69 IoT-based temperature sensors were installed around the cooling fog zone (W1) and a sunny control zone (W2).

- ■

- Data Collected:

- ■

- Measurement Period: The IoT sensors monitored temperature and humidity levels from September 13, 2021, focusing on peak afternoon hours.

| Section | Rooftop | Indoor | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 |  |

|

Coolwall+roof |

| H2 | Coolwall | ||

| H3 | Non applied |

| Section | Site | Address | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| W1 |  |

Hancheon Sports Park 166-1, Cheongcheon-ri, Yecheon-eup, Yecheon-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea |

Cooling fog zone |

| W2 |  |

Hancheon Sports Park 166-1, Cheongcheon-ri, Yecheon-eup, Yecheon-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea |

Sunny zone |

3.2.3. Shading Structure Experimentation in Geyang-gu

- Objective: To evaluate the impact of shading structures on reducing heat exposure in public outdoor areas, particularly for vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly.

- Study Location: Shading structures were installed in key public spaces within Geyang-gu, a district in Incheon Metropolitan City, located in the northwestern part of South Korea. Incheon has a coastal climate due to its proximity to the Yellow Sea, with warm, humid summers and cold winters. Geyang-gu, being part of a rapidly urbanizing area, experiences the effects of the urban heat island (UHI) phenomenon, which intensifies the already rising temperatures caused by global climate change.

- •

- Experimental Design:

- ■

- Data Collected:

3.2.4. Small water path Experimentation in Sangju-si

- Objective: To assess the cooling effects of waterway shelters designed for passive cooling in public parks, particularly for vulnerable populations such as the elderly and young children

-

Study Location: A small water path was constructed and tested in Namsan Park, located in Sangju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do. Sangju-si is situated in the central part of South Korea and experiences a humid continental climate with hot summers and cold winters. Due to its inland location, Sangju-si is particularly vulnerable to extreme temperatures, with significant heatwaves becoming more frequent during the summer months.The combination of high daytime temperatures and prolonged heatwaves has increased the need for effective climate adaptation strategies in the region.Sangju-si’s rural demographic, with a considerable portion of the population being elderly, amplifies the region’s climate change vulnerability. Elderly residents are more susceptible to heat stress, while the lack of extensive urban infrastructure means the community relies heavily on natural and built cooling features, such as water paths, to mitigate the effects of extreme heat. The introduction of a 150-meter-long water path in Namsan Park aims to provide passive cooling through evaporative effects, offering relief from the high summer temperatures and improving thermal comfort for park visitors. This feature is particularly important as it creates a cooler microclimate in public spaces frequently used by elderly residents and young children, who are most at risk from heat-related health issues.

- •

- Experimental Design:

- ■

- Data Collected:

| Section | Sensor installment | Address | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 |  |

Hyo-seong Daycare Center 280, Hyo-seong-dong, Geyang-gu, Incheon, South Korea |

Cool shadow zone |

| S2 |  |

Hyo-seong Daycare Center 280, Hyo-seong-dong, Geyang-gu, Incheon, South Korea |

Sunny zone |

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Temperature Reduction Comparison:

- Surface and Ambient Temperature: The primary method of analysis was the comparison of surface and ambient air temperatures before and after the installation of each technology. For each experimental site, temperature data were gathered using IoT-based sensors and data loggers at key intervals. Sensors recorded the rooftop surface temperatures (for cool roofs) and ambient air temperatures (for cooling fog, shading structures, and small water paths).

- Baseline vs. Post-Installation: Data were collected continuously both before and after the technology implementations. The temperature reduction effects were measured by comparing the baseline (pre-installation) temperatures with post-installation values under similar environmental conditions.

- Peak Heat Hours: Special emphasis was placed on peak heat periods (typically 12:00–16:00), where temperature reductions were most critical. For example, cooling fog and shading structures were assessed for their ability to reduce midday heat, while small water paths and cool roofs were evaluated for their overall daily temperature performance.

3.3.2. Direct and Indirect Temperature Effects:

- Direct Effects: The direct effects refer to the surface and ambient air temperature reductions caused by the technologies themselves. For example, cooling fog reduced ambient air temperatures in W1 (Cooling Fog Zone) by up to 5°C compared to W2 (Sunny Zone).

- Indirect Effects: Indirect effects were particularly relevant for cool roofs, where the impact on indoor temperatures and potential energy savings were analyzed. Buildings treated with reflective coatings not only experienced surface temperature reductions of up to 5°C but also saw indoor temperature reductions, reducing the demand for cooling.

| Section | Sensor installment | Address | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 |  |

Water Path Rest Area in Namsan Park 3, Namsan-dong, Sangju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea |

Small water path |

| P2 | Water Path Rest Area in Namsan Park 3, Namsan-dong, Sangju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea |

Sunny zone |

3.3.3. Temporal Analysis:

- Daily and Hourly Trends: Temperature data were analyzed in both daily and hourly increments. For example, data collected from August 27 to September 1, 2021 in Gimhae-si showed consistent cooling effects of cool roofs during midday heat, with peak reductions between 12:00 and 15:00.

- Day-to-Night Temperature Gaps: Additionally, nighttime temperatures were analyzed to determine the lasting effects of each cooling technology. Technologies like cool roofs and shading structures maintained lower temperatures even after peak sunlight hours.

3.3.4. Statistical Analysis:

- Mean Temperature Reductions: The mean temperature reduction for each technology was calculated across the monitoring period. These reductions were averaged across multiple sites and compared to control areas without the cooling technologies. For example, the mean temperature reduction from shading structures was up to 10°C during peak hours.

- Comparison of Temperature Gaps: The temperature gaps between treated and control areas were assessed using graphical analysis (as seen in the previous figures). This was particularly relevant for small water paths and shading structures, where the difference between shaded and sunny zones varied throughout the day.

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Cool Roof (Reflective Paint) Results

4.2. Cooling Fog Results in Yechun-gun

- Pre-activation temperature difference: W1 was already cooler by approximately 1.8°C due to environmental factors.

- Post-activation cooling effect: An additional 1.3°C temperature reduction was achieved after activation, for a total cooling effect of 3.1°C.

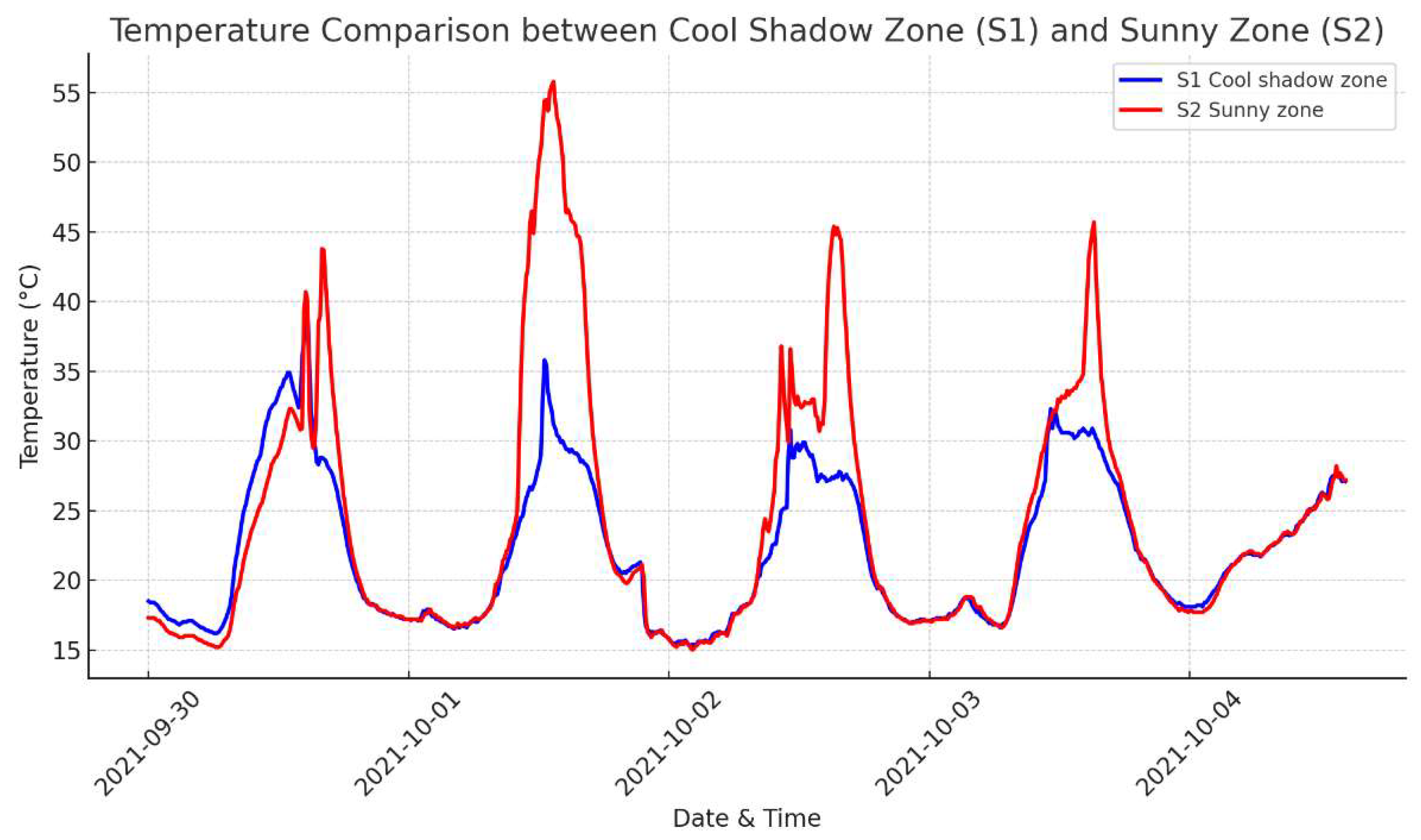

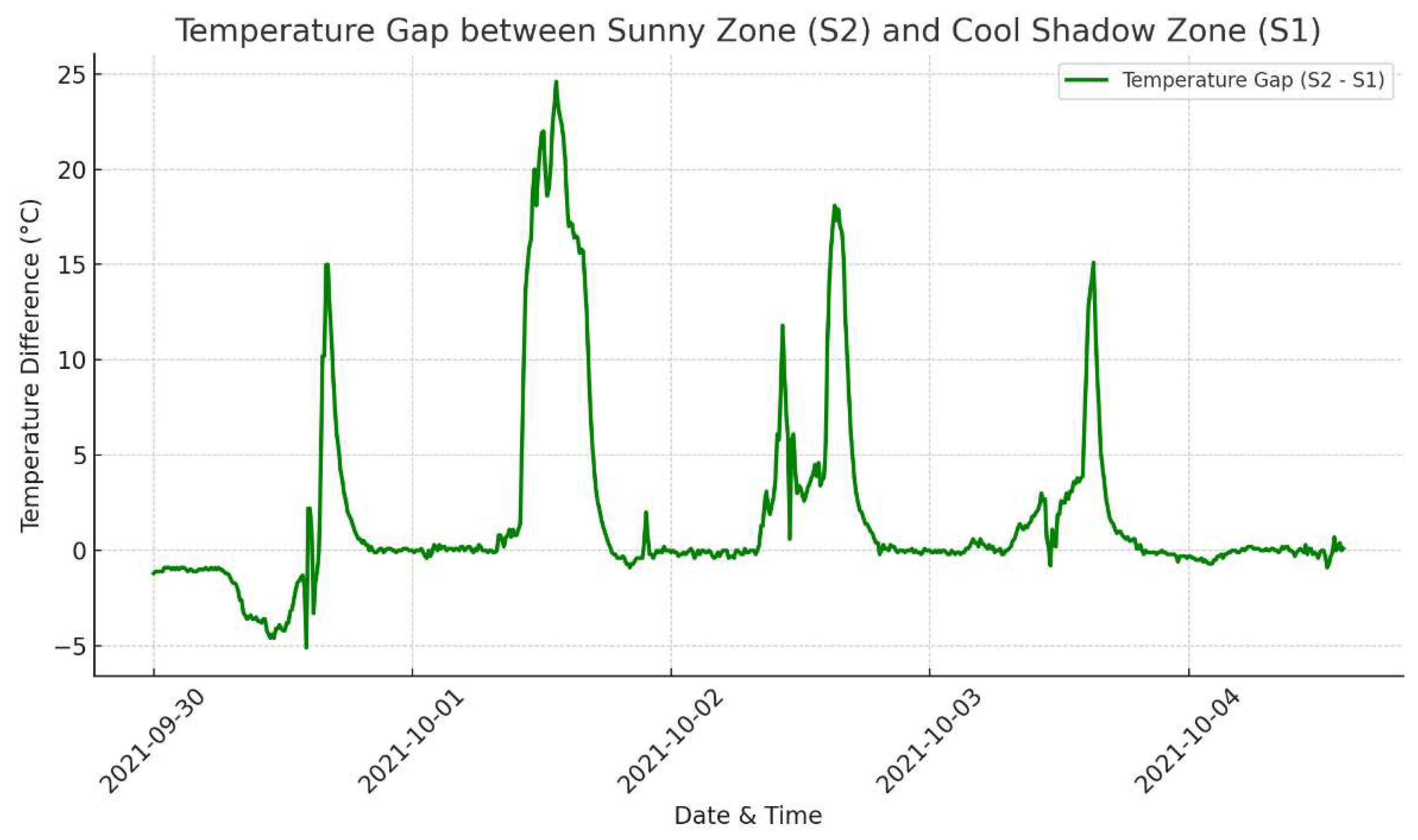

4.3. Shading Structure Results in Geyang-gu

- Pre-peak temperature difference: S1 was cooler by an average of 2°C to 3°C in the morning.

- Peak sunlight cooling effect: S1 surfaces were up to 10°C cooler than S2 during peak sunlight hours.

- Overall cooling efficiency: The shading structure provided a substantial cooling effect, with up to 10°C surface temperature reduction compared to unshaded surfaces.

- Surface Temperature Reduction: The shading structure led to a notable reduction in surface temperature within the shaded zone (S1). During the hottest part of the day, the temperature in S1 was reduced by as much as 10°C compared to the sunny zone (S2), proving the structure's effectiveness in moderating surface heat.

- Sustained Cooling Impact: Even after peak sunlight hours, the cooling effect in S1 persisted. The surface temperatures in the shaded zone remained significantly lower than those in the sunny zone, indicating a lasting cooling impact provided by the shading structure.

- Comparison with Sunny Zone (S2): While the sunny zone (S2) experienced extremely high surface temperatures during midday (up to 55°C), the shaded surfaces in S1 remained much cooler. This demonstrates that shading is a critical factor in reducing surface temperatures in public spaces, making them safer and more comfortable for users.

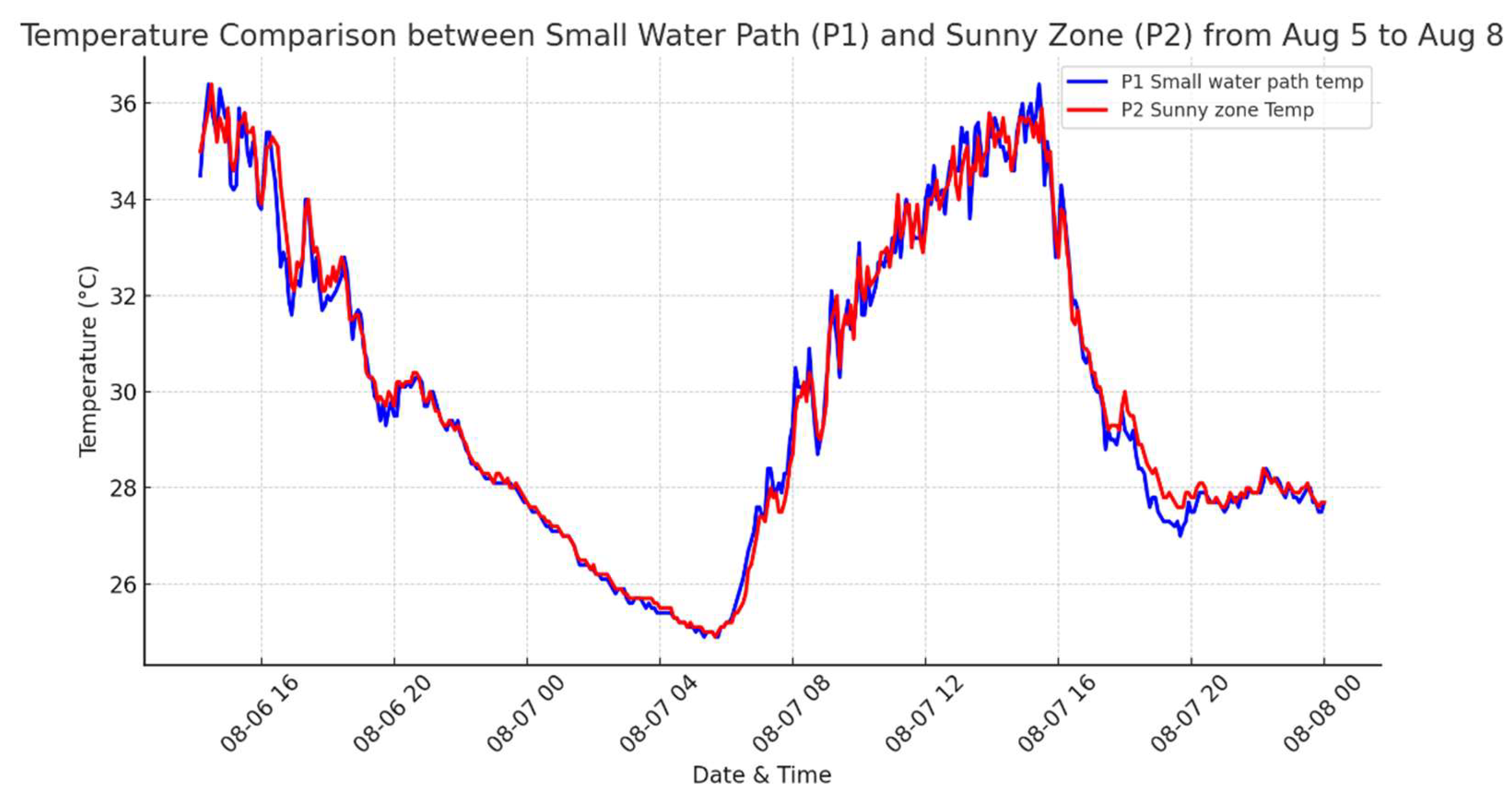

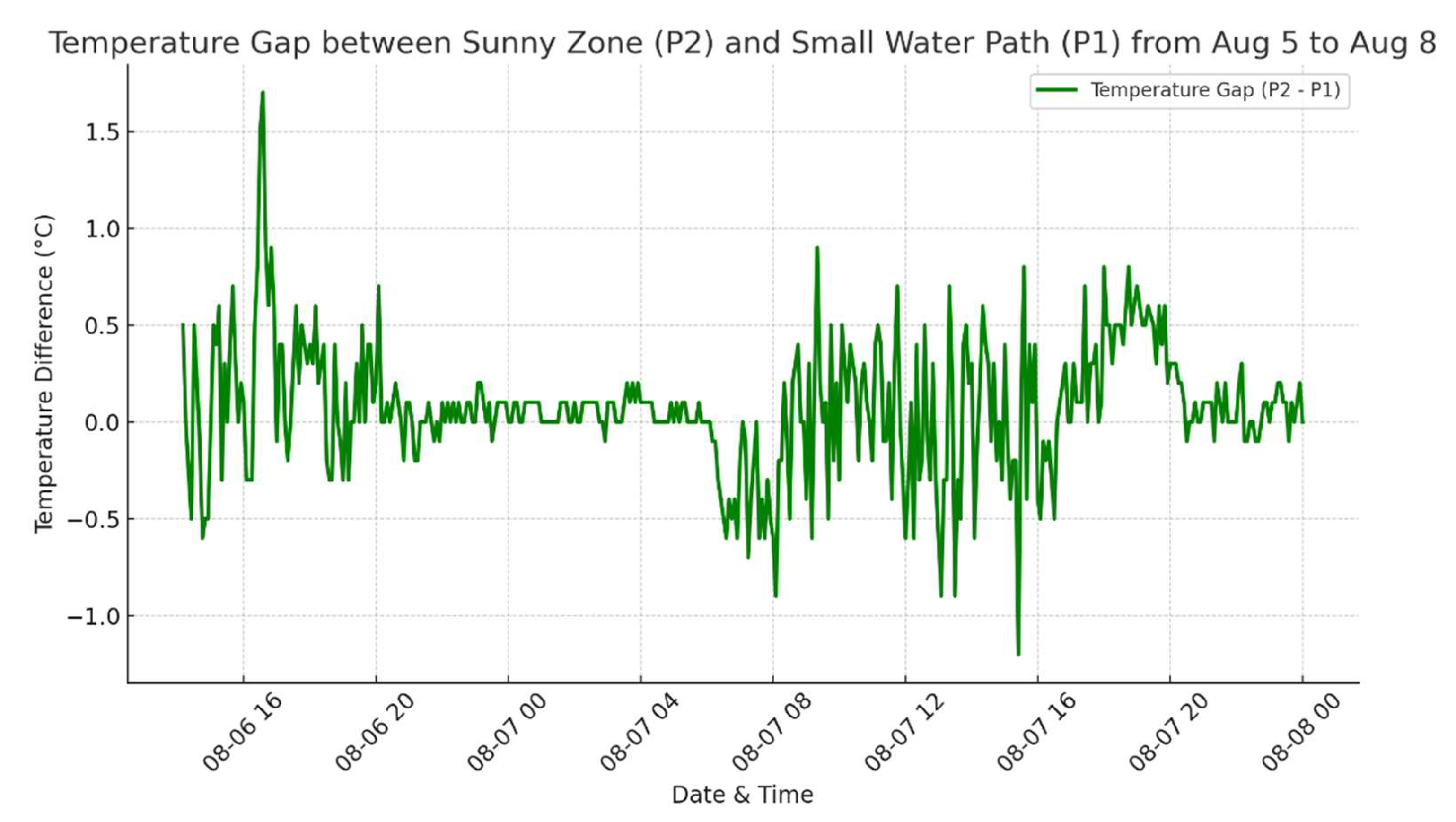

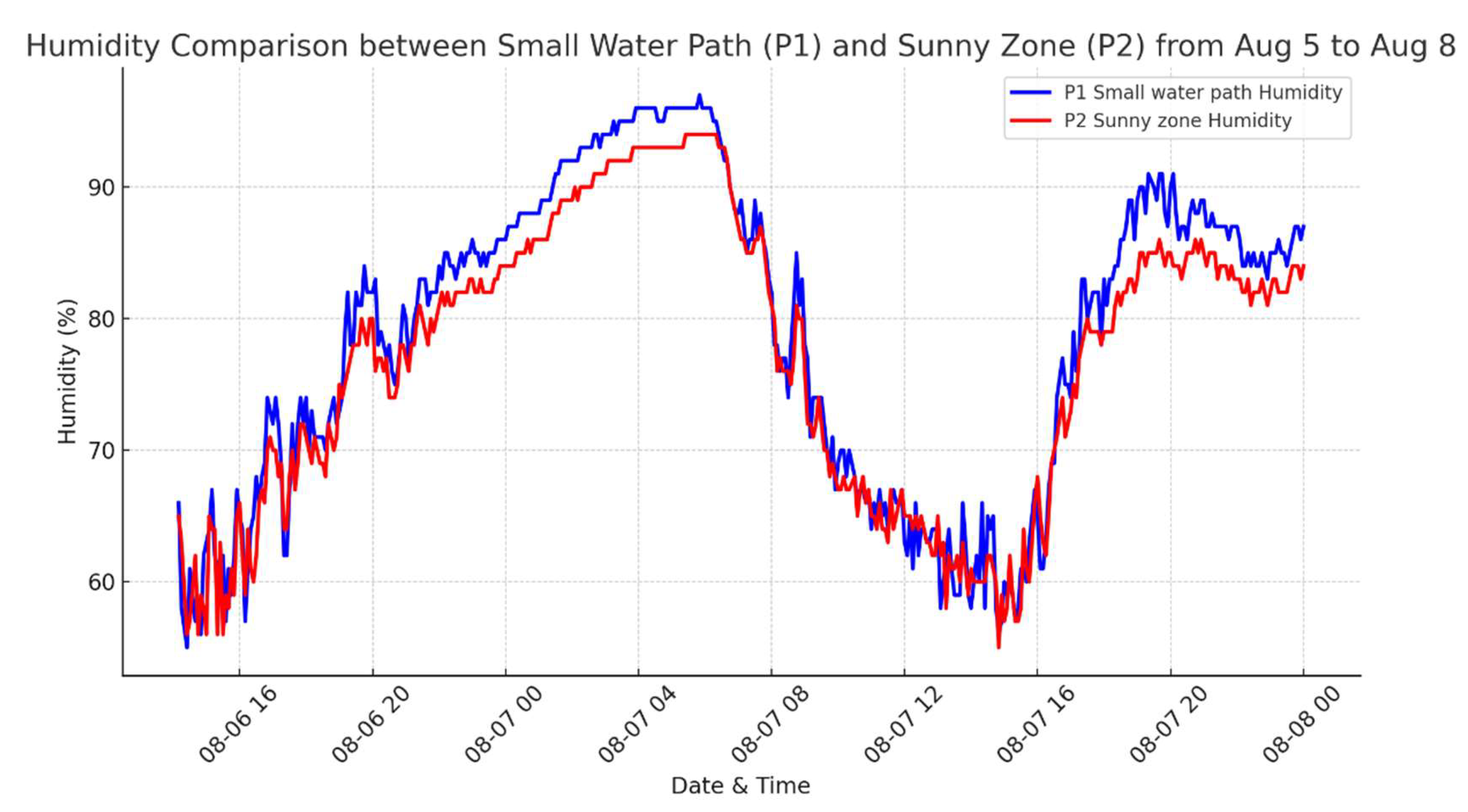

4.4. Small water path Results in Sangju-si

- Initial temperature difference: In the early afternoon, the temperature difference between P1 and P2 was minimal, with P1 being only about 0.5°C cooler.

- Peak cooling effect: The maximum cooling effect was observed in the late afternoon, where P1 was up to 1.5°C cooler than P2.

- Overall cooling impact: The small water path provided a consistent cooling effect, with an average temperature reduction of around 0.5°C to 1°C compared to the sunny zone.

- Temperature Reduction: The small water path demonstrated a significant temperature reduction effect, with air temperatures in P1 being up to 1.5°C cooler than the sunny zone (P2) during peak sunlight hours. This cooling effect was sustained throughout the day, particularly in the late afternoon.

- Humidity Increase: The relative humidity in the water path zone (P1) was consistently higher than in the sunny zone (P2), with humidity levels in P1 reaching up to 90% during the hottest part of the day, compared to around 85% in P2. This indicates that the water path not only reduced air temperature but also increased moisture in the surrounding area, enhancing comfort.

- Extended Cooling Impact: The cooling effect of the water path was maintained even after peak sunlight hours, suggesting a lasting cooling impact. As temperatures in P2 began to decline naturally, P1 continued to remain slightly cooler, demonstrating the residual cooling benefit of the water path.

- Comparison with Sunny Zone (P2): While both zones experienced similar temperature trends throughout the day, P2 consistently showed higher temperatures, indicating that the small water path was the primary driver of the cooling effect in P1.

4.5. Comparative Analysis of Technologies

- Temperature Reduction Comparison.

- Thermal Comfort and User Feedback:

| Cooling Solution | Temperature Reduction | Key Observation | Measurement Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cool Roof + Cool Wall | 2-3°C during peak hours | Combining both cool roof and cool walls showed the best reduction in surface and air temperatures. | 27 Aug. 2021 - 1 Sep. 2021 |

| Cool Wall | 1-2°C compared to non-applied surfaces | Effective for reducing wall temperatures but less effective compared to combined treatments. | 27 Aug. 2021 - 1 Sep. 2021 |

| Cooling Fog System | Up to 3.1°C during operational window | Immediate reduction of ambient air temperature after system activation. | 13 Sep. 2021 (2:00 PM – 4:30 PM) |

| Shading Structure | Up to 10°C during peak sunlight | Consistent cooling effect, especially during the hottest part of the day. | 30 Sep. 2021 - 4 Oct. 2021 |

| Small Water Path | Up to 1.5°C during peak sunlight | Moderate temperature reduction with increased humidity levels in the surrounding area.1 | 5 Aug. 2023 - 8 Aug. 2023 |

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

- Cooling Fog was one of the most effective solutions for providing immediate temperature reductions in high-traffic outdoor areas, reducing ambient temperatures by up to 3.1°C during operational periods, which greatly improved perceived comfort.

- Cool Roofs (Reflective Paint) offered significant reductions in both surface and indoor temperatures, contributing to long-term energy savings. Buildings treated with reflective coatings experienced surface temperature reductions of 2-3°C.

- Shading Structures provided a low-maintenance solution for mitigating solar exposure and improving thermal comfort in outdoor public spaces. Surface temperature reductions of up to 10°C were recorded in shaded areas, particularly during peak sunlight hours.

- Waterway Shelters offered steady passive cooling, with air temperature reductions of up to 1.5°C and humidity increases that enhanced thermal comfort for park visitors. This cooling effect was particularly noticeable in the late afternoon and evening hours.

5.2. Recommendations

- 1.

- Adopt a Holistic Approach to Urban Heat Mitigation

- 2.

- Prioritize Vulnerable Populations in Heat Mitigation Efforts

- 3.

- Incorporate Heat Mitigation into Urban Planning Policies

- 4.

- Monitor and Evaluate the Effectiveness of Cooling Technologies

- 5.

- Collaborate with International Cities to Share Best Practices

5.3. Future Research

- Long-term Monitoring: The monitoring period should be extended to assess the year-round performance of cooling technologies and their effectiveness under different seasonal conditions.

- Cost–benefit Analysis: Future studies should conduct detailed cost-benefit analyses of cooling technologies to determine the most cost-effective solutions for urban areas with varying budget constraints.

- Integration of Green Infrastructure: Research should explore how cooling technologies can be combined with green infrastructure (e.g., urban forests and green roofs) to maximize their cooling potential while enhancing biodiversity and environmental sustainability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LEAL FILHO, W.; Karimi, A.; Mohajerani, A.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. Addressing the Urban Heat Island Effect: A Cross-Country Assessment of the Role of Green Infrastructure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Mohajerani, A.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. New Developments and Future Challenges in Reducing and Controlling Heat Island Effect in Urban Areas. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2023, 25, 10485–10531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Bakaric, J.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. The Urban Heat Island Effect, Its Causes, and Mitigation, with Reference to the Thermal Properties of Asphalt Concrete. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 197, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, A.; Almusaed, A. The Urban Heat Island Phenomenon upon Urban Components. In Biophilic and Bioclimatic Architecture: Analytical Therapy for the Next Generation of Passive Sustainable Architecture; Springer, 2011; pp. 139–150.

- Santamouris, M. Recent Progress on Urban Overheating and Heat Island Research: Integrated Assessment of the Energy, Environmental, Vulnerability, and Health Impact. Synergies with the Global Climate Change. Energy and Buildings 2020, 207, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, S.; Mall, R.K. Urban Ecology and Human Health: Implications of Urban Heat Island, Air Pollution, and Climate Change Nexus. In Urban Ecology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 317–334.

- Harlan, S.L.; Ruddell, D.M. Climate Change and Health in Cities: Impacts of Heat and Air Pollution and Potential Co-Benefits from Mitigation and Adaptation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2011, 3, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, G.M.; Brazel, A.J. The Urban Physical Environment: Temperature and Urban Heat Islands. Urban Ecosystem Ecology 2010, 55, 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, H.; et al. Impact of Global Climate Change on Pulmonary Health: Susceptible and Vulnerable Populations. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2023, 20, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leap, S.R.; et al. Effects of Extreme Weather on Health in Underserved Communities. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

- Nasrollahi, N.; et al. Heat-Mitigation Strategies to Improve Pedestrian Thermal Comfort in Urban Environments: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; et al. Facing the Urban Overheating: Recent Developments, Mitigation Potential, and Sensitivity of the Main Technologies. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment 2018, 7, e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Jo, H.; Lim, Y. Research on the Development of Simulation Equipment for Measuring the Effect of Urban Shade Structures. Journal of Environmental Technology 2022, 23, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, T.; et al. Analysis of the Effectiveness of a Heat Insulation Project Supporting Vulnerable Populations Through IoT Monitoring Systems: A Case Study of Residential Areas in Jinyeong-eup, Gimhae-si. Journal of Climate Change Research 2022, 13, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, M.E. Preventing Disasters: Public Health Vulnerability Reduction as a Sustainable Adaptation to Climate Change. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2011, 5, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamouris, M. Cooling the Cities: A Review of Reflective and Green Roof Mitigation Technologies to Fight Heat Island and Improve Comfort in Urban Environments. Solar Energy 2014, 103, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; et al. Overview of Urban Heat Island (UHI) Phenomenon Towards Human Thermal Comfort. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal 2017, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Cotrim Pezzuto, C.; Alchapar, N.L.; Correa Cantaloube, E.N. Urban Cooling Technologies Potential in High and Low Building Densities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2301. [Google Scholar]

- Monge-Barrio, A.; Gutiérrez, A. S.-O. Passive Energy Strategies for Mediterranean Residential Buildings: Facing the Challenges of Climate Change and Vulnerable Populations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bom, G. J. (Ed.) . Evaporative Air-Conditioning: Applications for Environmentally Friendly Cooling; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A.; Al-Nimr, M.A. The Effectiveness of Multi-Stage Dehumidification–Humidification for Improving the Cooling Ability of Evaporative Air Conditioning. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy 2009, 223, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.; Singh, R.N. A Study on the Comparative Review of Cool Roof Thermal Performance in Various Regions. Energy and Built Environment 2022, 3, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinzi, M.; Fasano, G. Properties and Performance of Advanced Reflective Paints to Reduce the Cooling Loads in Buildings and Mitigate the Heat Island Effect in Urban Areas. International Journal of Sustainable Energy 2009, 28, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minangi, F.S.; Alibaba, H.Z. Effect of Shading on Thermal Performance of Dormitory Building in Hot Climate. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation 2018, 6, 610–621. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S. Fixed External Shading and Daylight Quality: Four Case Studies. MS Thesis, Kansas State University, 2016.

- Santamouris, M.; Synnefa, A.; Karlessi, T. Using Advanced Cool Materials in the Urban Built Environment to Mitigate Heat Islands and Improve Thermal Comfort Conditions. Solar Energy 2011, 85, 3085–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Pomerantz, M.; Taha, H. Cool surfaces and shade trees to reduce energy use and improve air quality in urban areas. Solar Energy 2001, 70, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Ali-Toudert, F. Effects of street design on outdoor thermal comfort. Landscape, Environment and Society 2006, 45.

- Levinson, R.; Akbari, H. Potential Benefits of Cool Roofs on Commercial Buildings: Conserving Energy, Saving Money, and Reducing Emissions of Greenhouse Gases and Air Pollutants. Energy Efficiency 2010, 3, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Fayaz, R.; Zolfaghari, S.A. Analyzing Outdoor Thermal Comfort Conditions in a University Campus in Hot-Arid Climate: A Case Study in Birjand, Iran. Urban Climate 2022, 43, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Brown, R.D. Integrating Microclimate into Landscape Architecture for Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Systematic Review. Land 2021, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban Greening to Cool Towns and Cities: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence. Landscape and Urban Planning 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising Green and Bluespace to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Intensity. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 584, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kang, J.E. Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into Community Planning Using a Participatory Process: The Case of Saebat Maeul Community in Busan, Korea. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2018, 45, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.W. Assessing Strategies for Urban Climate Change Adaptation: The Case of Six Metropolitan Cities in South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, T.Y. Assessing Health Sector Climate Vulnerability in 226 Local Entities of South Korea Based on Principal Component Analysis. Urban Climate 2023, 49, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.P.; et al. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Hong, J.W.; et al. Temporal Dynamics of Urban Heat Island Correlated with the Socio-Economic Development Over the Past Half-Century in Seoul, Korea. Environmental Pollution 2019, 254, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, Y.H. Urban Effect on Sea-Breeze-Initiated Rainfall: A Case Study for Seoul Metropolitan Area. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; et al. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Lee, S.; Paavola, J.; Dessai, S. Deeper Understanding of the Barriers to National Climate Adaptation Policy: The Case of South Korea. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2023, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.G. An Analysis of Regional Climate Change Vulnerability in Korean Agriculture. MS Thesis, Seoul National University, 2019.

| Measurement | Range | Accuracy | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind Speed | 0 m/s ~ 50 m/s | ± 1 m/s (speed < 10 m/s); ± 10% (speed ≥ 10 m/s) | 0.1 m/s |

| Wind Direction | 0° ~ 359° | ± 15° | 1° |

| Temperature | -40°C to 60°C | ± 0.3°C (± 0.6°F) | 0.1°C (0.1°F) |

| Humidity | 1% to 99% | ± 3.5% | 0.01 |

| Light | 0 Klux to 200 Klux | ± 25% | 0.1 Klux |

| UVI (Ultraviolet Index) | 1 ~ 15 | ± 2 | 1 |

| Rainfall | 0 ~ 9999 mm | ± 10% | 0.3 mm (volume < 1000 mm); 1 mm (volume ≥ 1000 mm) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).