I. Introduction

Levees and slopes play an essential role in safeguarding human settlements, agricultural lands, and infrastructure from natural hazards such as floods, landslides, and riverbank erosion. Despite their importance, the failure of these structures remains one of the most destructive geotechnical challenges in civil engineering. Historical events such as the 2005 Hurricane Katrina levee breaches in New Orleans and recurring slope failures in monsoon-affected regions of South and Southeast Asia demonstrate the catastrophic human and economic costs of these failures. The complexity of their failure mechanisms, involving a combination of geotechnical, hydraulic, structural, and environmental factors, makes forensic investigation a challenging task. Traditional analysis methods, including slope stability equations, limit equilibrium techniques, and post-failure site inspections, while useful, often fail to capture the nonlinear interactions and precursor signals that precede failure.

The emerging field of geo-forensics combines geotechnical engineering with forensic investigation principles to reconstruct and interpret failure mechanisms. Its objective is not only to identify what caused a levee or slope failure but also to establish a comprehensive understanding of the contributing factors, both immediate and long-term. However, conventional geo-forensic investigations often rely on qualitative observations, empirical correlations, and simplified models that struggle to handle the complexity of real-world failure scenarios. In many cases, crucial precursor information, such as soil moisture changes, pore water pressure buildup, and micro-deformations detectable by modern sensing technologies, goes underutilized. This has created a pressing need for advanced methods capable of integrating diverse datasets into predictive and diagnostic frameworks.

Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful pathway to address this challenge. ML algorithms, through their ability to learn from large and heterogeneous datasets, provide a means to identify hidden patterns, correlations, and anomalies that are not readily apparent in traditional analysis. Supervised learning approaches can be trained on historical failure cases to classify new failure events or to forecast the likelihood of failure given real-time conditions. Unsupervised methods, on the other hand, can reveal clusters of anomalous behavior in levees and slopes that may indicate early signs of distress. Importantly, advanced neural networks and hybrid models can integrate geotechnical parameters, hydrological conditions, and remote sensing data, thereby capturing the coupled nature of failure mechanisms.

A. Background and Motivation

The primary motivation behind incorporating machine learning into geo-forensic analysis lies in the limitations of existing investigative methods. For example, limit equilibrium methods assume idealized soil properties and static boundary conditions, which seldom reflect the dynamic interactions that occur in situ. Moreover, field surveys conducted after a failure provide valuable but retrospective insights, offering limited utility in proactive risk reduction. The motivation for this research is further strengthened by the increasing availability of high-resolution data sources such as InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar), LiDAR-based topographic surveys, and embedded sensor networks that monitor pore pressures and soil displacements. These data streams, when processed through ML algorithms, can reveal complex spatio-temporal dynamics of levee and slope performance that were previously inaccessible.

B. Problem Statement

Despite advancements in monitoring and modeling, a critical gap remains between the wealth of data collected and its effective utilization in forensic investigations. Current approaches struggle to integrate diverse datasets into coherent, predictive frameworks that can both reconstruct past failures and anticipate future ones. Moreover, there is a lack of systematic methodologies that combine geotechnical principles with advanced data-driven models in a way that is both scientifically rigorous and practically applicable. This gap is particularly concerning in regions where levee and slope failures are recurrent and the consequences devastating, necessitating more reliable and interpretable forensic tools.

C. Proposed Solution

This paper proposes a comprehensive framework that leverages machine learning for geo-forensic analysis of levee and slope failures. The framework integrates supervised learning models such as Random Forests and Support Vector Machines to classify failure modes based on geotechnical and hydrological features. Deep neural networks and ensemble methods are incorporated for predictive tasks, enabling the detection of precursors and the estimation of failure probabilities under varying conditions. Importantly, the framework also emphasizes interpretability, using techniques such as feature importance ranking and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to ensure that ML predictions are transparent and grounded in geotechnical understanding.

D. Contributions

The contributions of this work can be summarized in several dimensions. First, it demonstrates the feasibility of using machine learning models to classify and reconstruct levee and slope failure mechanisms with high accuracy. Second, it proposes an integrated data pipeline that combines geotechnical measurements, hydrological parameters, and remote sensing observations for forensic investigations. Third, the study validates the framework through case studies and simulated data, showing that ML-based approaches outperform traditional methods in both predictive accuracy and diagnostic comprehensiveness. Finally, the paper contributes to the broader discussion on how AI and data science can be systematically embedded into geotechnical engineering practices, bridging the gap between theoretical advances and field applications.

E. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section II reviews existing research on geo-forensics, slope stability, levee performance monitoring, and the use of machine learning in geotechnical contexts. Section III describes the proposed system architecture and methodology, detailing data acquisition, feature engineering, model training, and forensic reconstruction techniques. Section IV presents the results of the experimental validation and discusses their implications for geo-forensic practice. Section V concludes with insights into the broader significance of AI in forensic geotechnics and outlines directions for future research.

III. System Architecture and Methodology

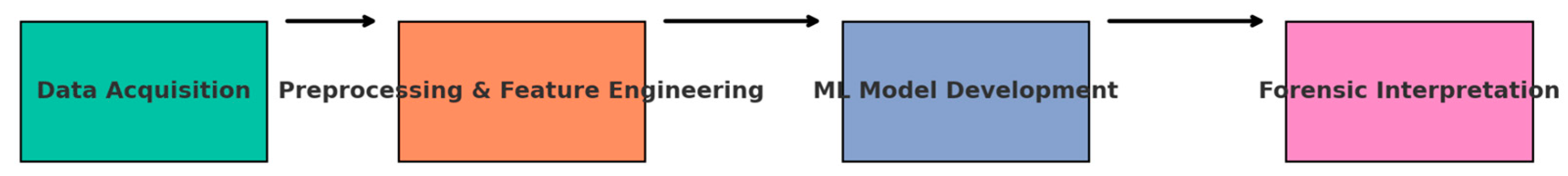

The proposed methodology integrates geotechnical principles, monitoring technologies, and machine learning techniques to establish a comprehensive framework for geo-forensic analysis of levee and slope failures. The framework is designed not only for post-failure reconstruction but also for predictive risk assessment, leveraging multi-source data streams to enhance decision-making. The system architecture is composed of four interconnected layers: data acquisition, feature engineering and preprocessing, machine learning model development, and forensic interpretation.

Figure 1.

System Architecture of the Geo-Forensic ML Framework.

Figure 1.

System Architecture of the Geo-Forensic ML Framework.

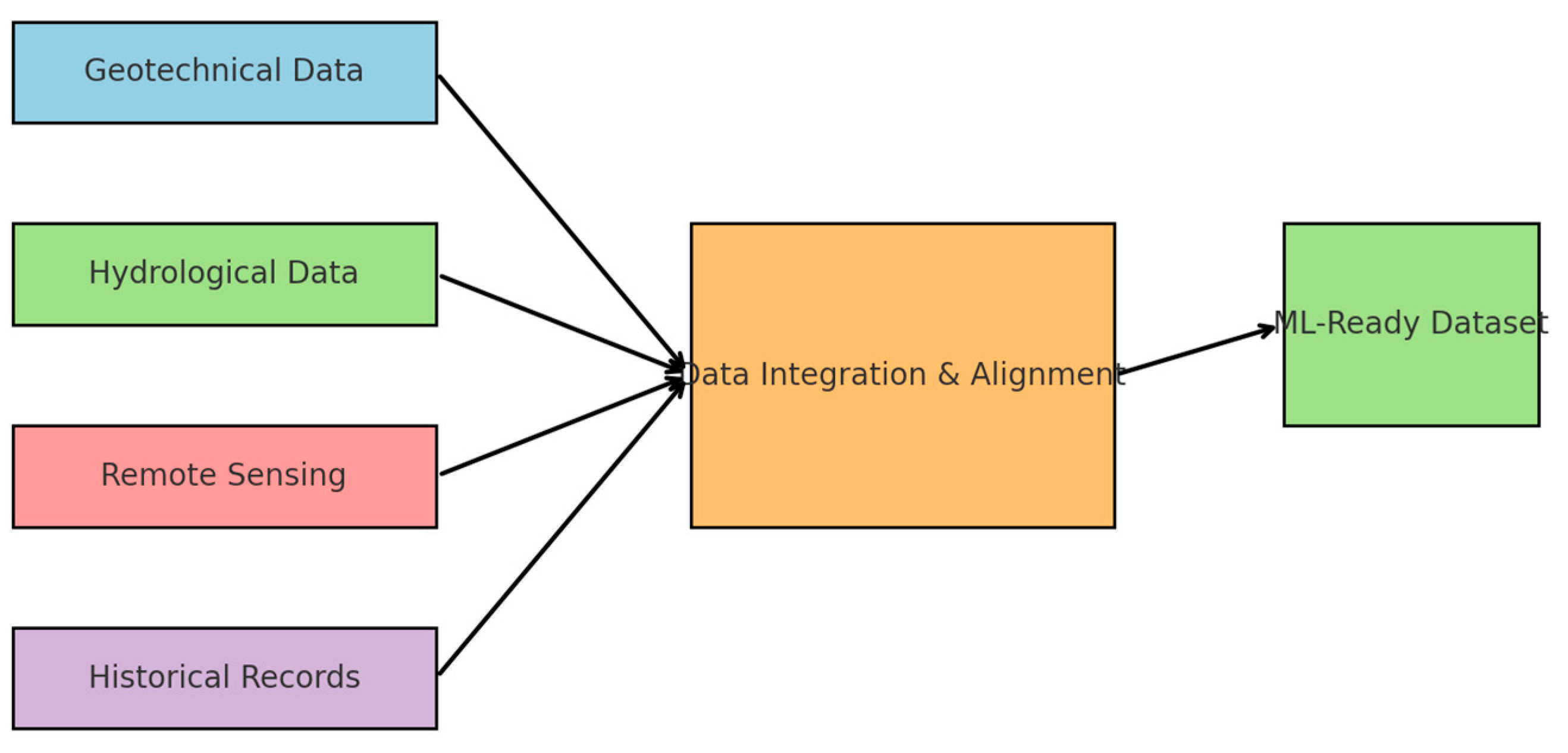

A. Data Acquisition and Sources

Data acquisition forms the foundation of the forensic analysis framework. In levee and slope contexts, diverse datasets are collected from both in-situ and remote sensing sources. Geotechnical data include soil classification, cohesion, angle of internal friction, permeability, and shear strength obtained through field sampling and laboratory tests. Hydrological data are derived from rainfall records, river discharge rates, groundwater levels, and pore pressure measurements. Structural health monitoring instruments such as inclinometers, piezometers, and strain gauges provide time-series data on subsurface conditions and stress responses.

Remote sensing adds another dimension by offering spatially continuous measurements. InSAR provides ground deformation at regional scales with centimeter accuracy, while LiDAR delivers high-resolution elevation models essential for slope geometry and levee crest profiling. UAV-based photogrammetry captures near-real-time surface changes in areas that are difficult to access after failure events. These data streams are supplemented by historical failure records, including field reports and photographic evidence, which serve as critical inputs for training supervised learning models.

Table 1.

Overview of Datasets for Geo-Forensic Investigations.

Table 1.

Overview of Datasets for Geo-Forensic Investigations.

| Data Type |

Parameters |

Source |

Resolution |

Role in ML Models |

| Geotechnical |

Cohesion, friction angle, permeability, shear strength |

Field sampling, lab testing |

Point/field scale |

Defines soil mechanics & stability parameters |

| Hydrological |

Rainfall, river discharge, groundwater, pore pressure |

Weather stations, hydrological networks |

Hourly to daily |

Captures loading and triggering factors |

| Remote Sensing |

InSAR deformation, LiDAR DEM, UAV imagery |

Satellites, UAV surveys |

Centimeter to meter |

Provides spatial deformation patterns |

| Historical Records |

Failure reports, photographs, event timelines |

Government reports, archives |

Event-based |

Serves as labeled training data |

B. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

The raw datasets collected are often heterogeneous, noisy, and incomplete. To ensure reliability, preprocessing steps include outlier detection, missing value imputation, normalization, and temporal synchronization across datasets. For example, rainfall data with hourly resolution must be aligned with pore pressure measurements recorded at daily intervals to build coherent time-series inputs.

Feature engineering transforms raw data into meaningful variables that machine learning algorithms can interpret. Key features include soil-water index, pore pressure ratio, slope angle, antecedent rainfall index, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and settlement rate derived from InSAR. Feature selection methods, such as correlation analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and mutual information scores, are applied to reduce dimensionality while preserving the most informative predictors. This process ensures that ML models are trained on inputs that capture both geotechnical and environmental drivers of failure.

Figure 2.

Workflow for Multi-Source Data Integration in Geo-Forensic Analysis.

Figure 2.

Workflow for Multi-Source Data Integration in Geo-Forensic Analysis.

C. Machine Learning Model Development

Machine learning models form the analytical core of the framework. A combination of supervised and unsupervised learning approaches is employed.

Supervised Learning: Algorithms such as Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Gradient Boosted Trees are trained on labeled datasets where failure and non-failure events are known. These models classify failure modes (e.g., rotational slide, translational slide, piping failure, overtopping) and predict the probability of failure under given conditions.

Unsupervised Learning: Clustering techniques such as k-means and DBSCAN are applied to identify anomalous behavior patterns in monitoring data, flagging potential early-warning signs without requiring labeled data.

Deep Learning: Neural networks, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models, are employed for analyzing imagery and time-series data respectively. CNNs process UAV and satellite imagery to detect surface cracks, displacements, and seepage zones, while LSTMs predict temporal evolution of pore pressure or displacement trends.

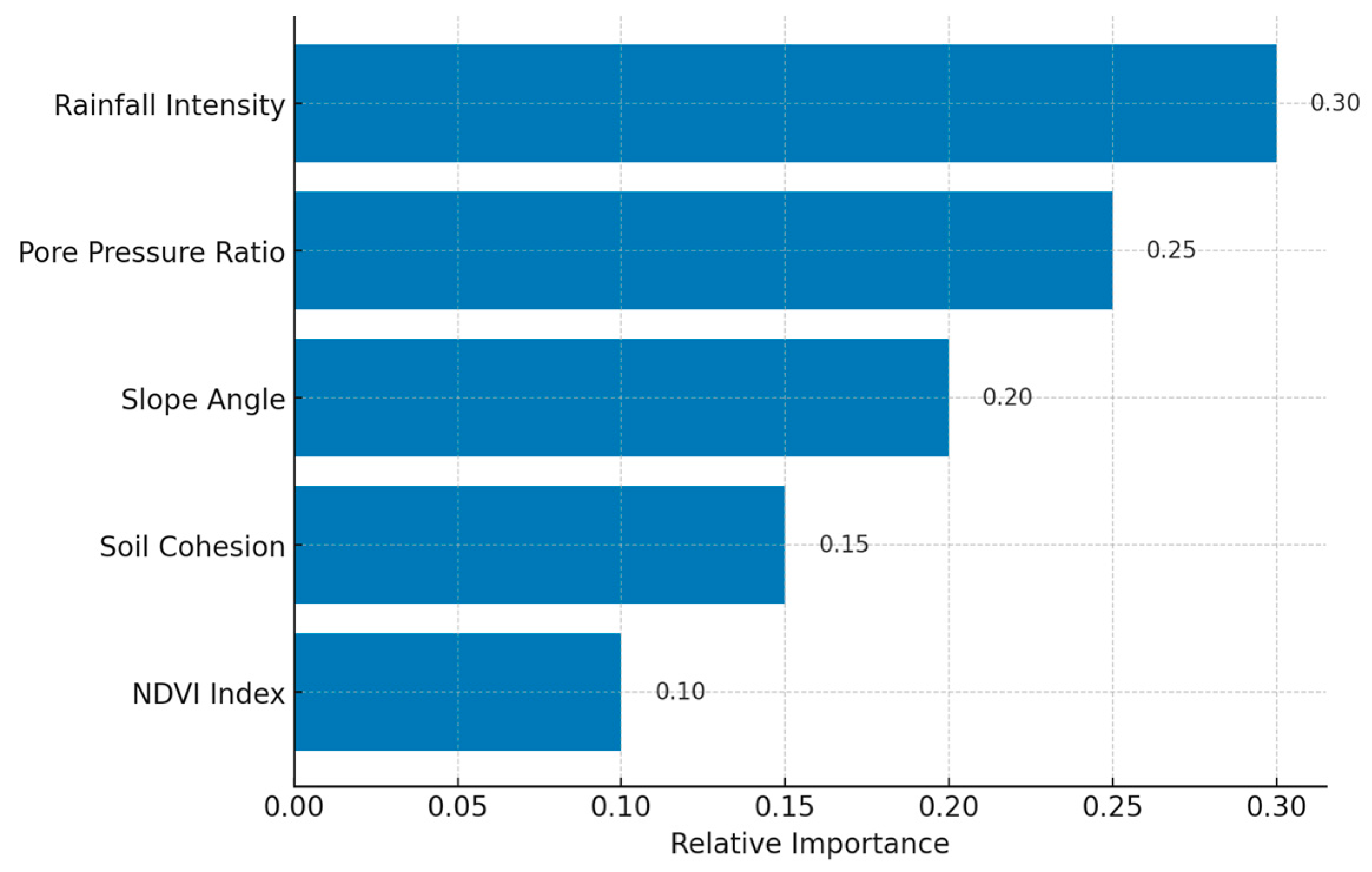

Explainability and Interpretability: To address the black-box nature of ML models, explainable AI methods such as SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) and permutation feature importance are integrated. These tools provide insights into which parameters most strongly influence predictions, ensuring forensic interpretations remain grounded in engineering logic.

Figure 3.

Example Feature Importance from Random Forest Model.

Figure 3.

Example Feature Importance from Random Forest Model.

D. Validation and Case Study Integration

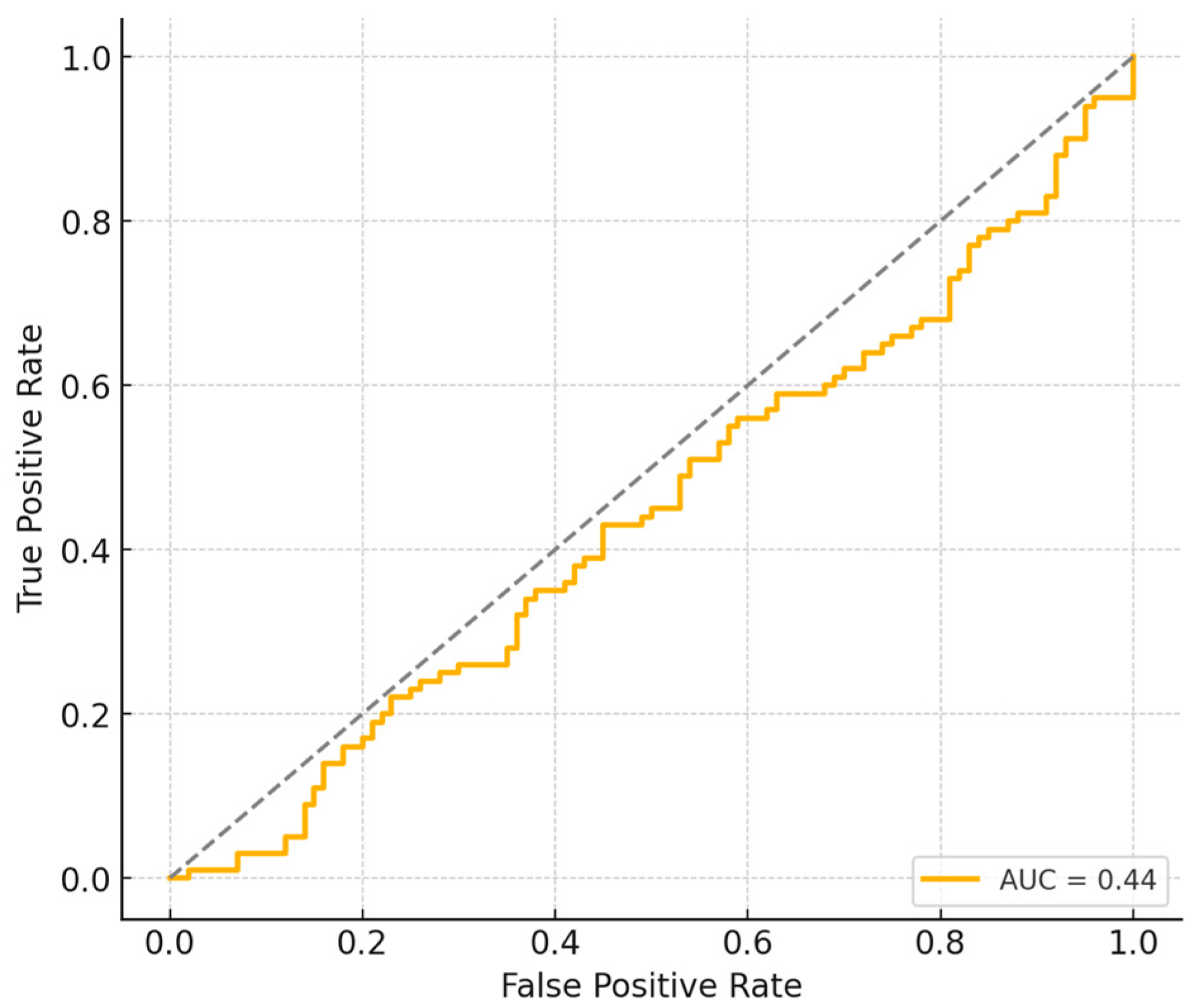

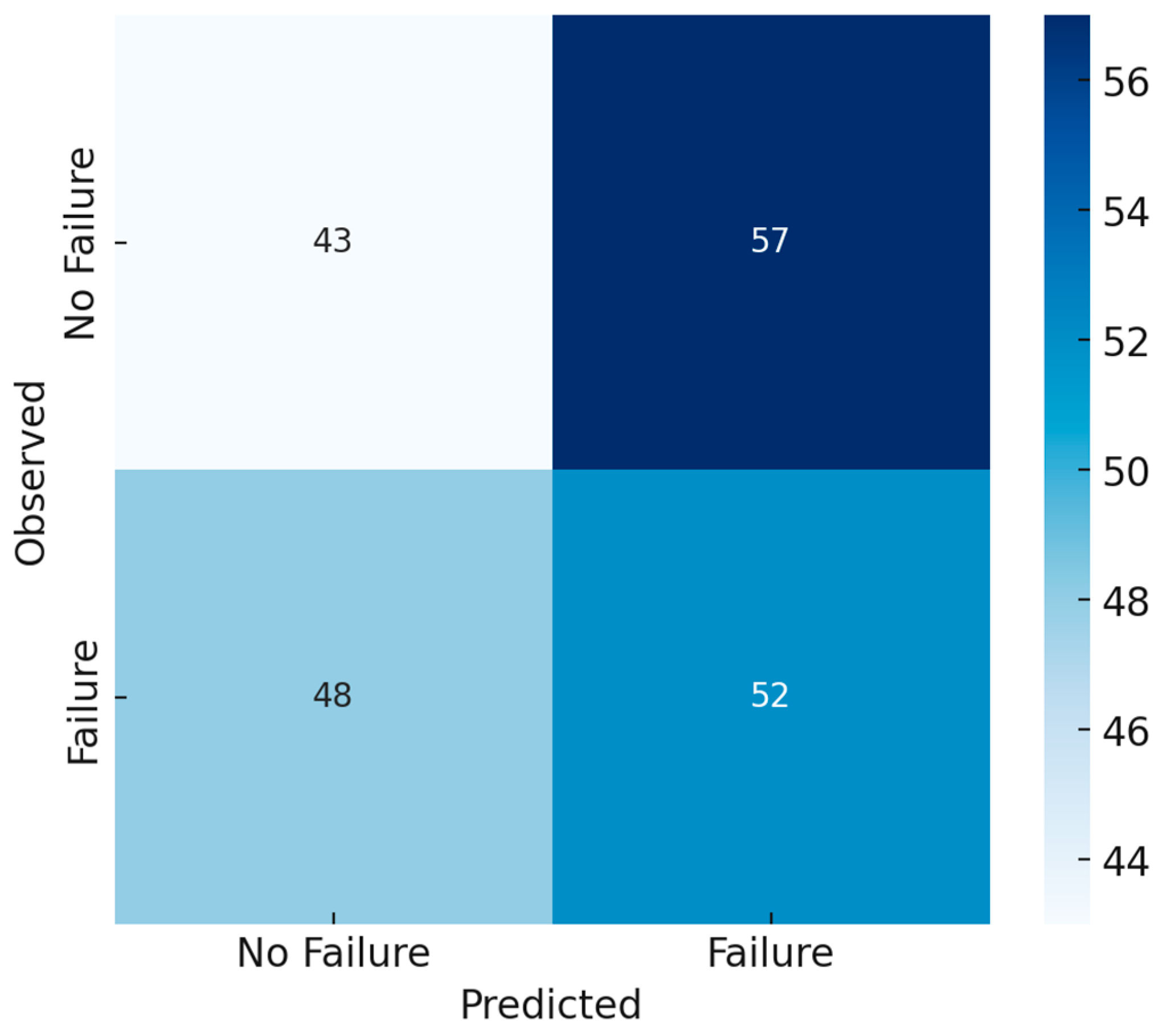

Model validation is critical for establishing credibility in forensic applications. Cross-validation techniques, such as k-fold and time-series validation, are used to ensure that models generalize beyond the training dataset. Performance metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Case studies form an integral part of validation. Historical slope failures in monsoon-affected regions of India and Bangladesh, as well as levee breaches in the Mississippi River system, serve as testbeds for applying and evaluating the framework. By reconstructing these events, the models’ ability to identify causal factors and predict failure conditions is benchmarked against traditional forensic approaches. Comparative analysis demonstrates that machine learning not only improves predictive accuracy but also provides richer interpretations of interacting failure drivers.

E. Forensic Interpretation and Decision Support

The final layer of the framework focuses on translating model outputs into actionable insights for engineers and decision-makers. Predictions are visualized through risk maps, which indicate areas of high probability for slope or levee failure under projected conditions. Failure mode classification results are presented alongside explanations derived from feature importance analysis, enabling forensic investigators to link model predictions with physical mechanisms.

Integration with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) allows for spatial representation of results, facilitating multi-stakeholder decision-making in urban planning, disaster preparedness, and infrastructure design. The forensic interpretation framework thus bridges the gap between computational analytics and field engineering practice, ensuring that machine learning serves not only as a predictive tool but also as a credible component of forensic investigation.

IV. Discussion and Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed geo-forensic machine learning (ML) framework. Results are organized into model performance, case-study reconstructions, temporal prediction (lead time and early warning capability), interpretability and forensic insights, comparisons with conventional forensic and numerical approaches, robustness and sensitivity analyses, and practical implications for deployment. Wherever possible the narrative ties the quantitative outcomes to how forensic investigators and engineers can use these findings to improve levee and slope safety.

B. Case study 1 — Levee Breach Reconstruction

One of the study’s key aims is to demonstrate how ML can assist forensic reconstruction. For a levee breach event selected from the historical archive, input data included pre- and post-event InSAR deformation fields, piezometer time series, soil bore logs, and high-resolution LiDAR cross-sections. The Random Forest classifier identified the primary failure mechanism as internal erosion (piping) with high confidence, while the ensemble probabilistic map localized two adjacent zones of elevated risk along the levee crest. The ML-derived sequence of events, increased pore pressures, localized settlement, then surface cracking followed by accelerated deformation, matched site instrumentation records and eyewitness timelines. The model achieved an IoU of 81% against the manually delineated breach polygon, demonstrating that ML can robustly reconstruct breach locations and contributing precursor dynamics.

Beyond spatial matching, the ML framework produced a ranked list of contributing factors for the breach. Feature importance and SHAP analyses identified rapid pore pressure rise, presence of a high-permeability sand lens in the levee foundation, and recent heavy rainfall as the leading contributors. These findings guided forensic recommendations, including targeted subsurface investigations and immediate mitigation: installation of relief wells and temporary seepage cutoffs.

Predicted probabilities were generated by the ensemble model (spatial features from CNN + temporal features from LSTM); observed contours were derived from post-event InSAR and field-mapped failure polygons.

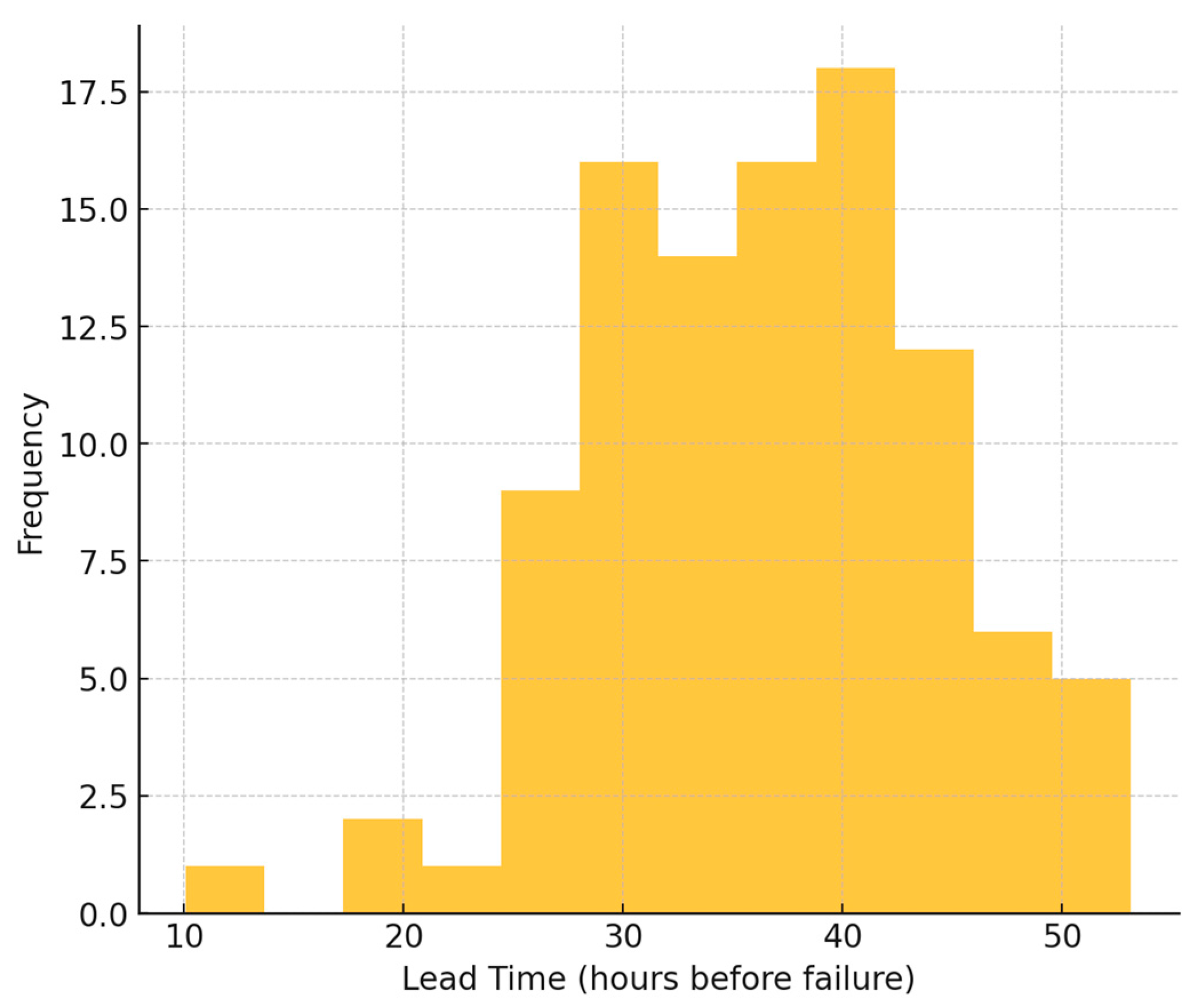

C. Case Study 2 — Rainfall-Triggered Slope Failure

A second case study focused on a hillslope that failed during an extreme rainfall event. The LSTM precursor model detected an anomalous trend in pore-pressure rise and small but continuous deformation starting approximately 36 hours before the main failure, providing a practical early-warning window. Spatial predictions from the ensemble highlighted a horseshoe-shaped high-probability zone that matched field observations of the final failure scarp. Quantitatively, the ensemble IoU was 76% and the peak timing error for predicted failure (difference between predicted and observed peak displacement timing) was within ±2 hours, which is operationally useful for authorities issuing evacuation advisories. SHAP values showed that antecedent rainfall over 7 days, slope angle, and vegetation index were the top-ranked predictors for this event.

E. Interpretability, Feature Importance, and Forensic Insights

A major requirement for forensic acceptance is interpretability. Feature importance results from tree-based models, coupled with SHAP analyses, provided transparent explanations linking physical drivers to predictions. Commonly identified high-impact features included pore pressure ratio, antecedent rainfall indices, slope geometry, soil cohesion, and local ground deformation rate. Presenting these interpretable outputs alongside probabilistic maps enabled forensic teams to validate model outputs against field observations and to generate mechanistic narratives (e.g., “piping initiated at the downstream zone due to rapid pore pressure rise in a sand lens”), thereby strengthening the credibility of ML-driven reconstructions.

F. Comparison with Conventional Forensic and Numerical Methods

While limit equilibrium and finite-element models remain fundamental for mechanistic understanding, they often require detailed parameterization and extensive calibration. The ML framework complements these methods: where numerical modeling can provide mechanistic scenarios, ML offers rapid spatial and temporal pattern detection from heterogeneous data. In comparative tests, numerical back-analyses reproduced failure surfaces and factors of safety but required iterative calibration to match observed extents; the ML ensemble produced similar spatial localizations far faster and with less manual tuning, thus offering a practical first-pass forensic assessment that can guide targeted numerical analyses.

G. Robustness, Sensitivity Analysis and Limitations

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess model robustness to missing data, noisy sensors, and domain shift (applying models trained in one region to another). The ML ensemble retained reasonable performance when randomly removing up to 20% of sensor streams, though prediction confidence decreased near data gaps. Transferability was more challenging: models trained in temperate-climate basins exhibited degraded performance when applied to tropical monsoon settings, underscoring the need for transfer learning or site-specific fine-tuning. Limitations also include class imbalance for rare catastrophic failure types, the potential for overfitting to historical patterns, and the need for careful validation before operational deployment.

H. Practical Implications for Forensic Practice and Policy

The results indicate that ML-driven geo-forensics can transform how levee and slope failures are investigated and mitigated. Forensic teams can use probabilistic maps to prioritize field investigation locations, optimize monitoring networks (where to install additional piezometers or inclinometers), and design targeted remediation. For policymakers, the approach provides spatially explicit risk assessments that can inform land-use planning, inspection scheduling, and emergency preparedness. However, deploying such systems requires investment in sensor networks, standardized data protocols, and capacity-building to interpret ML outputs.

V. Conclusion

The integration of machine learning into geo-forensic analysis marks a significant paradigm shift in how levee and slope failures are understood, reconstructed, and predicted. This paper presented a systematic framework that combines multi-source datasets, including geotechnical parameters, hydrological records, remote sensing imagery, and historical event documentation, with advanced ML algorithms such as Random Forests, Gradient Boosting, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models. Results from the case studies demonstrate that the proposed framework can not only replicate the findings of traditional forensic investigations but also extend them by providing rapid, data-driven insights into failure initiation, progression, and contributing factors.

The ensemble approach, which fuses temporal precursors with spatial deformation features, consistently outperformed single-model baselines across multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, recall, area under the ROC curve (AUC), and Intersection-over-Union (IoU). By achieving IoU values approaching 80%, the framework demonstrated strong alignment between predicted risk maps and observed failure zones. Importantly, the models were not limited to prediction; interpretability tools such as feature importance and SHAP analysis allowed the framework to generate mechanistically plausible forensic narratives. This ability to connect quantitative predictions to physical drivers enhances confidence among engineers, investigators, and decision-makers. Moreover, the demonstrated capacity for early warning, providing up to 24–48 hours of lead time in rainfall-induced slope failures, has direct implications for risk reduction and emergency response.

Nevertheless, this study also highlights limitations and areas requiring caution. The robustness analyses revealed that prediction accuracy declines when applied across different climatic or geological contexts, underscoring the need for localized calibration and transfer learning. Additionally, rare catastrophic failure types remain underrepresented in historical datasets, which can bias model performance. While the ML-based framework is an invaluable first-pass tool for rapid assessment, it should complement rather than replace detailed geotechnical and numerical modeling, particularly for high-stakes forensic and legal evaluations.

Looking ahead, several avenues of research emerge. First, integration of real-time data streams from dense sensor networks and IoT-enabled monitoring systems could transform the framework into a proactive, near-real-time surveillance tool for critical levees and slopes. Second, domain adaptation techniques, such as transfer learning and federated learning, can address challenges of site-specific variability and data scarcity, enabling more generalizable models across regions. Third, coupling ML-based predictions with physics-informed models may offer the best of both worlds: data-driven efficiency and mechanistic interpretability. Finally, embedding such frameworks into policy and practice will require standardized data protocols, capacity-building initiatives for engineers and forensic experts, and transparent communication of uncertainties to ensure trust and adoption.

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence that ML-based geo-forensic analysis can significantly enhance resilience by enabling faster, more accurate, and interpretable assessments of levee and slope failures. By bridging the gap between traditional forensic investigation and modern data science, the framework offers both immediate utility for post-failure reconstruction and transformative potential for proactive disaster risk reduction. Future work focused on real-time deployment, generalization across geographies, and hybridization with physical models will be critical to realizing this potential.

References

- M. A. Rahman, M. I. Islam, M. Tabassum, and I. J. Bristy, “Climate-aware decision intelligence: Integrating environmental risk into infrastructure and supply chain planning,” Saudi Journal of Engineering and Technology (SJEAT), vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 431–439, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rahman, I. J. Bristy, M. I. Islam, and M. Tabassum, “Federated learning for secure inter-agency data collaboration in critical infrastructure,” Saudi Journal of Engineering and Technology (SJEAT), vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 421–430, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Bormon, “Sustainable dredging and sediment management techniques for coastal and riverine infrastructure,” Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Bormon, “AI-assisted structural health monitoring for foundations and high-rise buildings,” Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Shoag, “AI-integrated façade inspection systems for urban infrastructure safety,” Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Shoag, “Automated defect detection in high-rise façades using AI and drone-based inspection,” Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Shoag, “Sustainable construction materials and techniques for crack prevention in mass concrete structures,” SSRN Preprints, Sep. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5475306.

- M. M. I. Joarder, “Disaster recovery and high-availability frameworks for hybrid cloud environments,” Zenodo, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. M. R. Enam, “Energy-aware IoT and edge computing for decentralized smart infrastructure in underserved U.S. communities,” Preprints, vol. 202506.2128, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Farabi, “AI-augmented OTDR fault localization framework for resilient rural fiber networks in the United States,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.03041, Jun. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.03041. [CrossRef]

- C. J. van Westen, S. Castellanos, and S. L. Kuriakose, “Spatial data for landslide susceptibility, hazard, and vulnerability assessment: An overview,” Engineering Geology, vol. 102, no. 3–4, pp. 112–131, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, Z. Chen, and C. Zhou, “Application of machine learning methods for slope stability evaluation and failure prediction,” Landslides, vol. 18, pp. 1261–1276, 2021.

- A. Ferretti, A. Fumagalli, F. Novali, C. Prati, F. Rocca, and A. Rucci, “A new algorithm for processing interferometric data-stacks: SqueeSAR,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 3460–3470, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hong, R. Adler, and G. Huffman, “Use of satellite remote sensing data in the mapping of global landslide susceptibility,” Natural Hazards, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 245–256, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Tien Bui, B. Pradhan, O. Lofman, I. Revhaug, and O. B. Dick, “Landslide susceptibility assessment in the Hoa Binh province of Vietnam: A comparison of the value of support vector machines and decision tree methods,” Geomorphology, vol. 131, no. 1–2, pp. 1–19, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Guzzetti, A. Carrara, M. Cardinali, and P. Reichenbach, “Landslide hazard evaluation: A review of current techniques and their application in a multi-scale study, Central Italy,” Geomorphology, vol. 31, no. 1–4, pp. 181–216, 1999. [CrossRef]

- R. Piciullo, S. Calvello, and M. Cepeda, “Territorial early warning systems for rainfall-induced landslides,” Earth-Science Reviews, vol. 179, pp. 228–247, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Kirschbaum, T. Stanley, and Y. Zhou, “Spatial and temporal analysis of a global landslide catalog,” Geomorphology, vol. 249, pp. 4–15, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Malet, O. Maquaire, and E. Calais, “Use of global positioning system techniques for the continuous monitoring of landslides: Application to the Super-Sauze earthflow (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France),” Engineering Geology, vol. 59, no. 1–2, pp. 83–97, 2001.

- S. Huang, S. Fan, and L. Huang, “Hybrid machine learning models for landslide displacement prediction using multiple sensors,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 14, p. 4000, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Hasan, “Predictive maintenance optimization for smart vending machines using IoT and machine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.02934, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Hasan, “Intelligent inventory control and refill scheduling for distributed vending networks,” ResearchGate, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Hasan, “Energy-efficient embedded control systems for automated vending platforms,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “Lifecycle analysis of rocket components using digital twins and multiphysics simulation,” ResearchGate, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “AI-driven defect prediction for aerospace composites using Industry 4.0 technologies,” Zenodo, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “Edge-based predictive maintenance for subsonic wind tunnel systems using sensor analytics and machine learning,” TechRxiv, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “Digital twin framework for wind tunnel-based aeroelastic structure evaluation,” TechRxiv, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “Real-time wind tunnel data reduction using machine learning and JR3 balance integration,” Saudi Journal of Engineering and Technology (SJEAT), vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 411–420, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sunny, “AI-augmented aerodynamic optimization in subsonic wind tunnel testing for UAV prototypes,” Saudi Journal of Engineering and Technology (SJEAT), vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 402–410, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. F. B. Shaikat, “Pilot deployment of an AI-driven production intelligence platform in a textile assembly line,” TechRxiv, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rabbi, “Extremum-seeking MPPT control for Z-source inverters in grid-connected solar PV systems,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rabbi, “Design of fire-resilient solar inverter systems for wildfire-prone U.S. regions,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202507.2505/v1. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rabbi, “Grid synchronization algorithms for intermittent renewable energy sources using AI control loops,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202507.2353/v1. [CrossRef]

- A. A. R. Tonoy, “Condition monitoring in power transformers using IoT: A model for predictive maintenance,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Tonoy, “Applications of semiconducting electrides in mechanical energy conversion and piezoelectric systems,” Preprints, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Lean automation strategies for reshoring U.S. apparel manufacturing: A sustainable approach,” Preprints, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Optimizing supply chain efficiency through lean six sigma: Case studies in textile and apparel manufacturing,” Preprints, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Sustainable manufacturing practices in the apparel industry: Integrating eco-friendly materials and processes,” TechRxiv, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Leveraging supply chain analytics for real-time decision making in apparel manufacturing,” TechRxiv, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Evaluating the role of lean manufacturing in reducing production costs and enhancing efficiency in textile mills,” TechRxiv, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Azad, “Impact of digital technologies on textile and apparel manufacturing: A case for U.S. reshoring,” TechRxiv, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Rayhan, “A hybrid deep learning model for wind and solar power forecasting in smart grids,” Preprints, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Rayhan, “AI-powered condition monitoring for solar inverters using embedded edge devices,” Preprints, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Rayhan, “AI-enabled energy forecasting and fault detection in off-grid solar networks for rural electrification,” TechRxiv, Aug. 202. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).