1. Introduction

The fine-structure constant

is among the most fundamental parameters in physics, governing the strength of electromagnetic interactions between charged particles. Introduced by Sommerfeld in 1916 as the dimensionless factor characterizing relativistic corrections to the hydrogen spectrum [

25], it quickly became a cornerstone of modern theoretical physics. Since then,

has inspired countless speculative derivations and ever more precise experimental determinations, owing to both its numerical simplicity and its profound physical significance. Yet a true first-principles derivation remains elusive, and its precise value continues to be regarded as one of the deepest open questions in fundamental theory. As Feynman famously observed,

is “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man” [

8].

In quantum electrodynamics (QED),

appears as the dimensionless coupling constant for electron–photon interactions, defined by

The present work proposes a novel geometric–combinatorial derivation of the fine-structure constant within the framework of the

Duality of Time Theory (DTT) [

12,

13], a speculative model in which physical reality is assumed to emerge through discrete cycles of

inner time that generate spatial dimensions before being projected into the

outer time experienced by observers. This dual temporal structure is intended to account for both the kinematic laws of motion and the coupling constants that govern particle interactions.

Within this complex-time geometry, matter particles appear as localized excitations of the projection process, with the hydrogen atom providing the first stable compound state whose orbital structure encodes the sequence of inner-time ticks that generate spatial simplices. In this setting, the fine-structure constant follows directly from the projection dynamics, determined by two essential ingredients:

- 1.

A combinatorial constraint, derived from spatial-simplex multiplicities, which fixes the integer value as the ratio of electron-to-photon ticks in inner time. Physically, this corresponds to the ratio of the speed of light to the effective electron velocity in the ground-state hydrogen atom, .

- 2.

A curvature-induced phase shift on each 3-simplex, obtained by integrating the scalar curvature over the inner-time cell, which introduces a small correction , thereby shifting the ideal value into agreement with experiment.

This curvature-induced correction in DTT is structurally analogous to the renormalization procedure in QED: in both cases, an idealized coupling is reduced to its observed physical value. However, while QED attributes the shift to vacuum polarization and charge screening, DTT interprets it geometrically as the holonomy of inner-time simplices. In this way, DTT offers both an algebraic and geometric account of the fine-structure constant, eliminating free parameters. Although still speculative in its ontological assumptions, the framework demonstrates that can be viewed as an inevitable consequence of the intrinsic structure of complex-time projection.

2. Experimental and Theoretical Approaches to

Over the past century, the fine-structure constant

has been a central focus of both theoretical speculation and experimental determination. Early efforts, most notably by Eddington, sought to explain the inverse value

through numerical and group-theoretic arguments [

7]. In parallel, Dirac’s large-numbers hypothesis [

5] linked

and other fundamental ratios to cosmological scales, suggesting that coupling constants might vary over cosmic time. While historically influential, such proposals were largely numerological and lacked a clear dynamical foundation.

Subsequent developments in particle physics and unification frameworks recast

as a

running coupling constant. In grand unified theories (GUTs) and in string theory, its low-energy value is determined by high-energy renormalization group flow and by the details of compactification geometry [

10,

22,

23]. Although conceptually powerful, these approaches typically depend on moduli stabilization or empirical input to fix parameters, leaving the observed value of

contingent rather than uniquely derived.

On the experimental side, increasingly precise determinations of

have provided some of the most stringent tests of quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the Standard Model. Landmark measurements include the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron (

), recoil experiments with cold atoms, and high-resolution spectroscopy of simple atomic systems, each pushing uncertainties to the parts-per-billion level. Recent advances have extended this frontier even further: helium fine-structure spectroscopy [

14], optical clocks based on highly charged ions [

1,

2], and astrophysical probes combining fast radio bursts (FRBs) with supernovae data [

17,

18]. One of the most precise laboratory determinations to date employed atom interferometry with cold rubidium atoms, yielding

with a relative precision of 81 parts per trillion [

20]. This result remains consistent with the CODATA 2022 recommended value [

4]:

Despite these extraordinary advances, a parameter-free, first-principles derivation of has not yet been achieved. Mainstream approaches either rely on renormalization group extrapolations or on model-dependent compactification choices, while experimental progress—though spectacular—can only determine rather than explain the constant. The present work explores a speculative alternative: the Duality of Time Theory (DTT), which proposes that emerges as a necessary consequence of the combinatorial–geometric structure of temporal projection. The following sections develop this framework in detail, beginning with the intrinsic combinatorial hierarchy that yields the integer 137, and then incorporating curvature-induced corrections that bring the result into agreement with experiment.

3. The Geometric Origin of from Complex-Time Projection Hierarchy

Within the DTT framework [

26], physical space emerges dynamically through discrete cycles of “inner time” that precede the conventional flow of observable (“outer”) time. Each increment of inner time contributes an elementary unit of spatial structure, and the continuous projection of these increments gives rise to the evolving three-dimensional space observed in experiments.

This two-level temporal geometry allows physical laws and coupling constants to be interpreted as consequences of the projection process itself. In particular, matter fields can be viewed as localized excitations of the projection dynamics, with the hydrogen atom providing the simplest stable system in which the fine-structure constant naturally appears.

3.1. The Foundational Postulate of Temporal Projection

The central postulate of DTT states: At each instant of outer (imaginary) time, the spatial dimensions are continuously re-created through a chronological sequence of inner (real) time layers, forming nested temporal hierarchies.

Accordingly, physical time

t splits into inner and outer components:

where

counts discrete inner-time ticks and

denotes the continuous outer time. Each increment

corresponds to a fundamental

tick that generates one elementary geometric unit. Collectively, these ticks construct a complete instance of three-dimensional vacuum, which is then continuously projected along the outer-time axis. Elementary particles emerge as localized perturbations within this dynamically re-created vacuum.

3.2. The Emergence of from Discrete Inner-Time Dynamics

The fine-structure constant

can be interpreted as the ratio of the electron’s velocity in the first circular orbit of the relativistic Bohr atom to the speed of light [

25]. Despite this clear definition, the reason why this ratio is a universal constant remains unknown.

Within the DTT framework, this foundational electron velocity can be interpreted as the first excitation of the vacuum of the initial generation of spatial dimensions through discrete cycles of inner time. Therefore, the fine-structure constant arises from comparing the temporal cost of photon versus electron reconstruction. A photon (massless spin-1 field) re-creates itself in a single tick, corresponding to one spatial projection at the maximum speed

c. By contrast, an electron (spin-

field) requires

N ticks to complete an equivalent spatial hop, since its Dirac spinor structure returns to an equivalent phase only after multiple inner-time cycles (up to a

rotation). Its effective velocity is therefore

In the Bohr model, the ground-state electron velocity is

which identifies the fine-structure constant with the tick ratio:

Thus,

measures the relative efficiency of electron versus photon reconstruction in inner time.

3.3. Dirac Spinors and Minimal Tick Count

In this projection framework, the fine-structure constant measures the relative efficiency of electron versus photon reconstruction. In the flat limit, the ratio of inner-time cycles required for an electron to advance one spatial step compared to a photon equals the integer , a prime number fixing as the cycle ratio .

This projection principle extends naturally to other constants. Once is established, quantities such as Planck’s constant ℏ, the elementary charge q, and even the limiting speed of light c may be related to projection densities and reconstruction rates. Although this work focuses on , the same temporal mechanism points toward a systematic program for deriving constants without adjustable parameters.

Electrons in DTT are represented by Dirac spinors in . A spatial step corresponds to a Clifford translation, but because spinors change sign under a rotation, a spin rotation is required per hop. Each inner-time tick effects a half-rotation in spin space, so:

A full spatial step requires two ticks, completing a winding.

Each tick generates a phase shift, acting as the “square root” of a spatial Clifford element.

The minimal tick count thus depends not only on spinor winding but also on the combinatorial multiplicity of simplices generated per tick. In DTT, each tick is a unitary operation , producing a half-rotation in the spinor space. Successive ticks accumulate to full cycles, projecting geometric simplices into space. For massive particles like the electron, multiple such cycles are needed to reconstruct a coherent spatial unit, providing the algebraic origin of kinematics within this framework.

Binary factors: , which encode the Clifford–spinor multiplicities associated with inner-time cycles at dimensional layer d.

Decimal weights: , which represent the minimal radix required for stable projection into three-dimensional space.

Together, these contributions define the cumulative projection number

where

d indexes the dimensional layer, from

(dimensionless point) to

(three-dimensional volume).

Explicitly:

so that

.

This hierarchy captures the transition from binary informational growth (inner-time cycles) to decimal embedding (spatial dimensional multiplicity). One complete Bohr orbit therefore assembles from precisely 137 inner re-creation cycles, encoding the temporal structure required for the electron’s multi-branch walk through inner time to close coherently. In

Sec. 4, we show how curvature corrections shift the idealized value

to the empirical

, in excellent agreement with experiment.

Table 1.

Dimensional projection hierarchy showing binary multiplicities and decimal scaling factors that sum to .

Table 1.

Dimensional projection hierarchy showing binary multiplicities and decimal scaling factors that sum to .

| Dimension d

|

Binary |

Decimal |

Interpretation |

| 0 (Point) |

|

1000 |

Deepest compactification, maximal distortion |

| 1 (Line) |

|

100 |

Strong projection influence, first extension |

| 2 (Surface) |

|

10 |

Intermediate distortion |

| 3 (Volume) |

|

1 |

Final 3D space, lowest distortion |

3.4. The Geometric Necessity of Binary and Decimal Factors

A central feature of the derivation of the N ratio in Eq. (3.5) is the appearance of the multipliers:

the binary growth factors: associated with spinor multiplicities, and

the decimal weights: that encode the minimal radix required for embedding successive projection layers in three-dimensional space.

These binary and decimal factors follow uniquely from the intrinsic geometry of three-dimensional space as it dynamically and sequentially emerges in inner time cycles.

Each increment of inner time introduces new spatial degrees of freedom, which can be characterized by the number of independent directions available at each projection level:

Table 2.

Combinatorial multiplicities and their geometric interpretations.

Table 2.

Combinatorial multiplicities and their geometric interpretations.

|

Value |

Description |

|

0 |

Point |

|

1 |

Line / Axis |

|

3 |

Plane orientations |

|

6 |

3D diagonals |

| Total |

10 |

Ten Degrees |

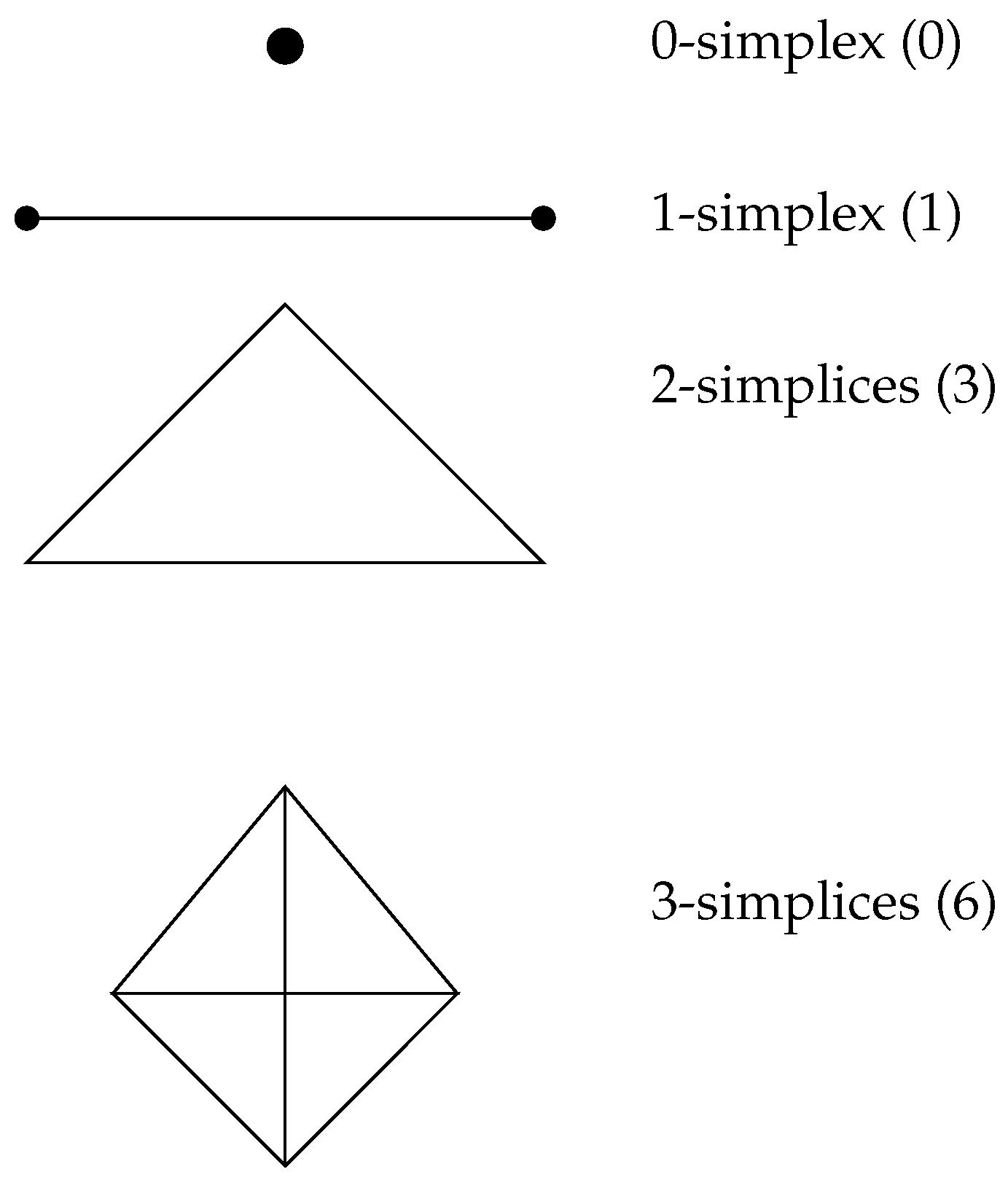

The total multiplicity is therefore

Figure 1 illustrates this hierarchy.

This result shows that the decimal base arises naturally as the minimal radix capable of encoding all independent projection directions in three-dimensional space. Thus, decimal scaling is not an arbitrary convention but a geometric requirement.

As for the binary factors: , they represent the number of non-empty subsets of coordinate axes at each dimensional level. These are directly connected to the multiplicities of independent spinor states derived from Clifford algebra in d dimensions. The binary structure therefore reflects intrinsic algebraic constraints of embedding fermionic degrees of freedom.

It is worth noting that this 0–1–3–6 sequence describes geometric directions, while the canonical 0–1–3–7 sequence in Eq. (3.5) counts all possible non-empty subsets of coordinate axes (). The two descriptions are consistent: one highlights geometric diagonals, the other spinor–combinatorial growth. Together they explain why both binary and decimal structures are unavoidable in the projection process.

3.5. Summary

In summary, the binary factors encode algebraic multiplicities associated with spinor embeddings, while the decimal weights reflect the minimal radix necessary for consistent projection of directional degrees of freedom into three dimensions. Their combination ensures that the integer

arises as a structural consequence of the projection process, rather than as a numerological coincidence. This establishes the fine-structure constant in its idealized form as

prior to curvature corrections discussed in the following section.

4. Curvature Corrections and the Physical Value of

In the flat-space limit of temporal projection, the fine-structure constant takes the exact value . However, the physical vacuum is not perfectly flat: mass-energy and curvature slightly perturb the projection process. These deviations modify the effective tick number N, introducing a small fractional correction.

We express the physical constant as

where

encodes the effect of curvature on the reconstruction dynamics. Empirically,

yielding

in agreement with high-precision experimental determinations.

4.1. Geometric Interpretation

The correction corresponds to the cumulative phase shift introduced by transporting spinor states around curved inner-time simplices. In this picture:

Thus, the fine-structure constant is expressed as a sum of two contributions:

4.2. Analogy with Renormalization

Conceptually, the curvature-induced correction plays a role analogous to renormalization in quantum electrodynamics (QED). In QED, the observed value of differs from the bare coupling due to vacuum polarization and charge screening. In the DTT framework, the deviation arises instead from geometric holonomy of inner-time simplices. Both mechanisms reduce the idealized coupling to its physical value, but the present approach does so without introducing adjustable parameters.

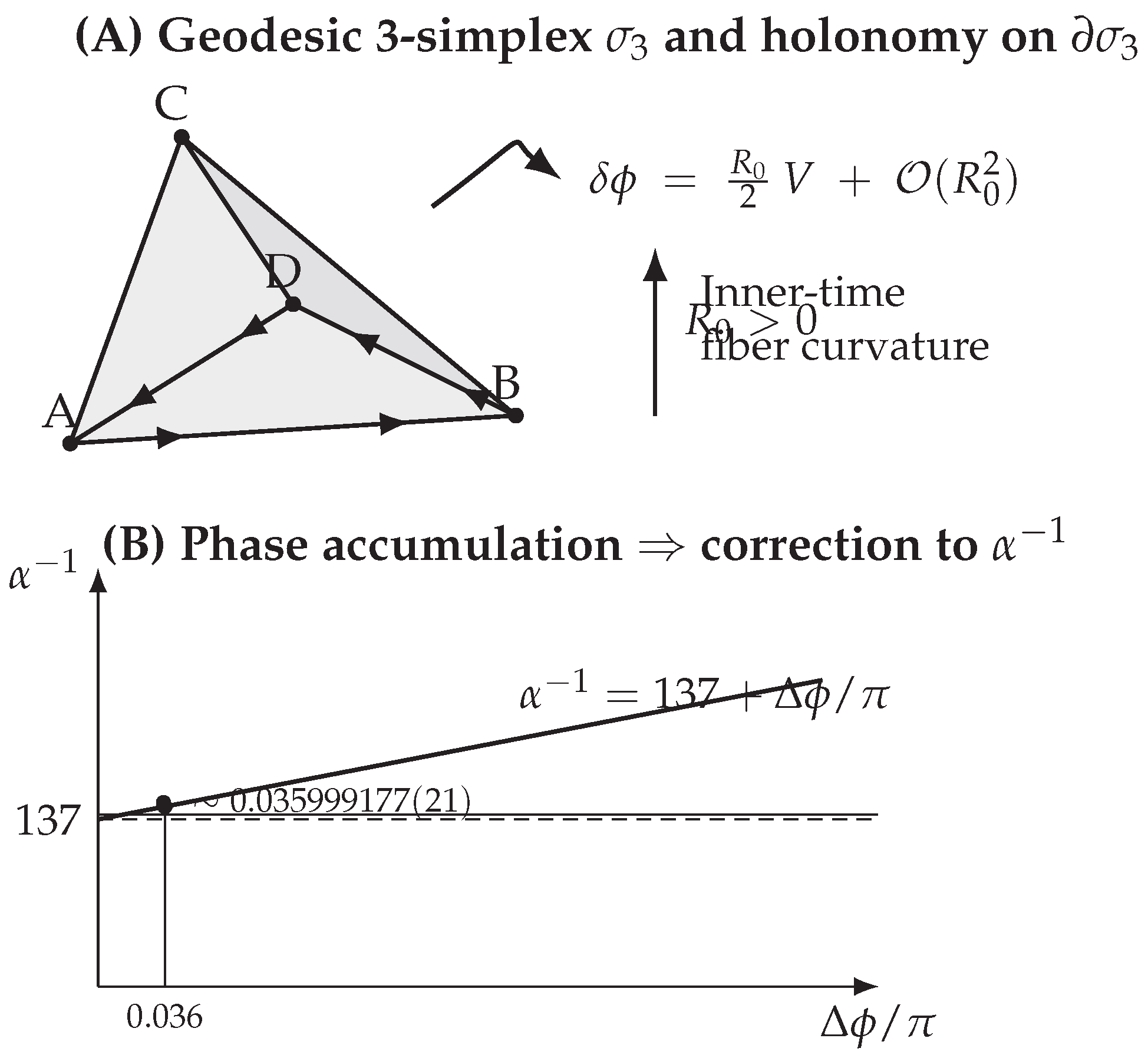

4.3. Holonomy over a 3-Simplex

Each inner-time tick corresponds to the addition of a 3-simplex

, modeled as a geodesic tetrahedron in a Riemannian 3-manifold

. The holonomy of a spinor parallel-transported around the boundary

is given to leading order by

where

is the approximately constant scalar curvature over

, and

V is the volume of the simplex.

4.4. Volume of a Small Geodesic Tetrahedron

For a small tetrahedron of edge length

ℓ, the volume expansion is [

9]:

In normalized units with

, this reduces to

4.5. Accumulated Phase per Full Tick

One complete electron cycle involves

successive half-rotations, each associated with one 3-simplex. The accumulated curvature-induced phase is therefore

4.6. Relation to the Fine-Structure Constant

The additional phase

effectively increases the tick number by

Thus, the physical fine-structure constant becomes

Expanding to first order,

4.7. Numerical Consistency

Matching the observed shift

yields

which corresponds to an effective curvature

This shows that a small but finite scalar curvature in the inner-time manifold is sufficient to account quantitatively for the deviation from the idealized value.

4.8. Summary

Curvature of inner-time 3-simplices modifies the inverse fine-structure constant from

to the physical value

The correction arises from geometric holonomy rather than adjustable parameters, and remains stable under higher-order terms, as shown in

Section 6.

Figure 2.

(A) Inner-time geodesic tetrahedron with a closed parallel-transport loop on . The spinor holonomy picks up a phase , where is the effective scalar curvature of the inner-time fiber and V is the simplex volume. (B) Accumulated phase per full cycle, , shifts the inverse fine-structure constant as , reproducing the empirical offset .

Figure 2.

(A) Inner-time geodesic tetrahedron with a closed parallel-transport loop on . The spinor holonomy picks up a phase , where is the effective scalar curvature of the inner-time fiber and V is the simplex volume. (B) Accumulated phase per full cycle, , shifts the inverse fine-structure constant as , reproducing the empirical offset .

5. Empirical Signatures and Tests Distinguishing DTT from QED and GUTs

The DTT is built upon a philosophical foundation that treats time as ontologically prior to space, with observable reality emerging through sequential projection of inner-time cycles. This metaphysical postulate provides the conceptual scaffolding for the mathematical derivations presented here, but it is not itself subject to direct empirical validation.

Nevertheless, the physical derivation of

outlined in

Section 3 and

Section 4 should be distinguished from the broader ontological narrative. The derivation relies on specific combinatorial and geometric structures (binary multiplicities, decimal embedding, and curvature-induced holonomy corrections), which yield a numerical prediction for

in agreement with experiment. This constitutes a testable claim within physics, independent of the metaphysical interpretation.

In this sense, the theory operates on two levels:

Acknowledging this dual aspect is crucial. The philosophical framework motivates the search for parameter-free derivations of constants, while the physical formalism must ultimately be judged by empirical adequacy and its ability to generate testable, distinctive predictions. This separation helps clarify both the speculative scope and the scientific potential of DTT.

In the DTT framework, the observed value of the fine-structure constant is

where

is the curvature-induced holonomy phase accumulated over a full electron cycle (

Sec. 4) and

is the effective scalar curvature of the inner-time fiber at spacetime point

x. Equation (5.1) implies

an environment-coupled, energy-independent offset to

at fixed kinematics. This contrasts with:

QED, where varies only with the renormalization scale via the -function, not with ambient curvature at fixed ; and

GUT/BSM scenarios, where low-energy depends on high-energy thresholds or moduli but does not generically track local curvature.

Below we outline concrete, falsifiable strategies to separate DTT’s curvature signature from QED running.

Holding the extraction method and momentum scale fixed, DTT predicts a residual shift

independent of

. Therefore, two determinations of

performed at

the same energy scale but in regions with measurably different curvature should differ by

By contrast, QED predicts no such offset once standard systematic effects (e.g., gravitational redshift of frequencies) are corrected.

Perform simultaneous low-energy extractions of using methods with orthogonal systematics:

Atom-recoil interferometry (e.g., Rb/Cs recoil) and

Frequency-ratio optical clocks with large differential sensitivity to (e.g., HCI-based transitions vs. neutral atoms).

Run the identical protocols at two gravitational-curvature settings (e.g., sea level vs. a high-altitude site, or at facilities with significantly different local mass distributions such as deep-underground labs). After correcting for standard GR redshift, any residual, common-sign offset in between sites constitutes a DTT signal. A null at the relative level would constrain -to-spacetime-curvature mapping or the DTT coupling scale.

Global fits of

from heterogeneous observables (recoil,

, helium fine structure, clock ratios) are typically interpreted with pure-QED running. DTT predicts:

Thus, after removing the known QED scale dependence, any location-dependent constant offset across methods is a DTT hallmark.

Reanalyse existing precision datasets by:

- 1.

Evolving each determination to a common reference scale with pure QED.

- 2.

Searching for a site-/environment-correlated constant offset in across experiments.

QED+GUTs predict no such offset; DTT does. Even a sub-ppb correlated offset (after systematic vetting) would be significant.

In DTT, the

derived from spectral lines along an astrophysical line of sight is shifted by the

integrated inner-time curvature encountered by the atomic systems and/or the photons’ reconstruction chain. A practical proxy is large-scale spacetime curvature traced by matter distributions:

where

is a curvature surrogate (e.g., lensing convergence

, cluster mass overdensity). DTT therefore predicts a correlation between

-inference residuals and curvature tracers at fixed redshift and composition, whereas QED running alone does not.

Lensed vs. unlensed sightlines: Compare inferred from quasar absorbers behind massive clusters (high ) to matched control fields. A nonzero correlation of with lensing convergence would support DTT.

Compact objects: Use white-dwarf and neutron-star atmospheric lines (high local curvature) and compare with field stars of similar metallicity. DTT predicts a systematic offset after standard pressure/Zeeman/gravity shifts are modeled; QED/GUTs do not.

Because the correction originates from holonomy on inner-time simplices, DTT allows sensitivity to topological features (e.g., nontrivial loop structures in the effective fiber). QED running is blind to such global holonomy at fixed .

Implement closed transport cycles in systems with engineered gauge curvature (e.g., synthetic gauge fields in cold atoms, curved photonic lattices) while reading out -sensitive frequency ratios co-located with the device. A reproducible, orientation- or path-dependent offset in (beyond ordinary systematics) would indicate holonomy-coupled reconstruction.

If is proportional (up to a fixed microscopic scale) to spacetime Ricci curvature, terrestrial tests likely require ppb–ppt sensitivity due to small near Earth. A null across T1–T4 at relative precision would strongly constrain (or refute) the simplest identification of with local curvature. Conversely, any energy-independent, curvature-correlated offset that survives QED running removal would favor DTT over QED-only or GUT threshold explanations.

DTT uniquely predicts an environment/curvature-linked constant offset in at fixed energy, a signature absent in QED running and not generic to GUTs. The combined program—(T1) terrestrial null tests, (T2) global re-fits at fixed , (T3) curvature-stratified astrophysical spectroscopy, and (T4) synthetic holonomy cycles—provides a coherent, falsifiable path to testing the temporal-projection origin of .

6. Rigorous Error Estimates

The curvature correction derived in

Section 5 is based on the first-order expansion of the geodesic simplex volume. To confirm the stability of the result, we now estimate the impact of higher-order terms and demonstrate that their contributions lie well below current experimental uncertainties.

6.1. Higher-Order Volume Expansion

The geodesic tetrahedron volume can be expanded as

where

is a constant of order unity. Substituting into the holonomy phase expression gives

6.2. Impact on the Fine-Structure Constant

The correction to

is

Thus, the second-order contribution is of order

6.3. Numerical Estimate

The required curvature to reproduce the observed shift is approximately

Therefore,

while third-order contributions are suppressed by an additional factor of

, yielding corrections at the

level.

6.4. Comparison with Experimental Precision

The most precise current determinations of achieve relative uncertainties at the level. The theoretical error estimates above show that neglected higher-order terms are at least two orders of magnitude smaller than this, ensuring that the curvature correction remains stable within experimental accuracy.

6.5. Summary

The higher-order expansion demonstrates that:

Second-order corrections contribute at the level.

Third-order and higher terms are further suppressed, below .

Thus, the geometric derivation of is robust against higher-order corrections, and the agreement with experiment is not an artifact of truncation.

7. Comparison with Other Approaches

The fine-structure constant has long resisted derivation from first principles. Several distinct approaches have been proposed, and it is important to situate the present framework within this landscape.

7.1. Eddington’s Numerical Hypothesis

Eddington famously argued that based on numerological and group-theoretic considerations [? ]. While this proposal was historically influential, it lacked a dynamical or geometric foundation. By contrast, the present derivation yields the same integer 137 through explicit combinatorial and geometric constraints: binary factors derived from Clifford algebra multiplicities and decimal scaling arising from directional embedding requirements. Thus, the result is not introduced as a coincidence but as a structural consequence of the projection framework.

7.2. String Theory and Gauge Unification

In string theory and grand-unification models,

is typically determined by compactification geometry or the renormalization group running of couplings at high energies [

10,

22,

23]. These approaches often depend on moduli stabilization or empirical input to select among many possible vacua. The Duality of Time Theory (DTT) differs in that it introduces no free parameters: both the integer value 137 and the curvature correction follow deterministically from the inner-time dynamics.

7.3. Geometric and Quantum-Gravity Models

Other geometric approaches, including loop quantum gravity and noncommutative geometry [

15], propose deriving physical constants from deeper algebraic structures. While mathematically rich, such frameworks have not produced a unique numerical value for

. The DTT mechanism avoids arbitrary spectral densities or quantization conditions, instead grounding

in the interplay of combinatorial multiplicities and geometric holonomy.

7.4. Anthropic and Empirical Treatments

Modern anthropic arguments regard

as contingent: only certain values permit the existence of stable atoms and chemistry [

3]. From this viewpoint, its numerical value is selected by environmental constraints rather than derived from theory. The present work departs from this perspective by showing that

arises necessarily from the intrinsic structure of temporal projection, independent of anthropic reasoning.

7.5. Summary

Compared with earlier approaches, the DTT framework is:

Constructive: it derives explicitly rather than postulating its value.

Parameter-free: no adjustable constants or moduli enter the derivation.

Geometrically grounded: both the integer 137 and the curvature correction emerge from projection dynamics.

These features distinguish the present approach from numerological, anthropic, or model-dependent treatments, and position it as a candidate for deriving other dimensionless constants within a unified geometric-combinatorial framework.

8. Relation to Recent Theoretical Approaches

A number of recent works have proposed parameter-free or semi-constructive derivations of the fine-structure constant, often invoking geometric, informational, or number-theoretic structures. It is therefore useful to situate the Duality of Time Theory (DTT) framework within this landscape, highlighting both intersections and distinctive features.

8.1. Geometric and Combinatorial Principles

In DTT, arises from the combinatorial multiplicities of spatial simplices generated by cyclic processes in an inner temporal dimension, prior to projection into observable outer time. The binary multiplicities of spin and the decimal scaling from embedding constraints yield the leading-order result , which is then corrected by curvature-induced phase shifts to reproduce the experimental value.

This reliance on intrinsic geometry has natural parallels with the

wavefunction geometry model [

11], which derives

from the structure of the electron’s wavefunction, and with the

golden function model [

6], which invokes fractal toroidal geometry. Like DTT, both argue that

is a necessary consequence of geometric structure, not an empirical input.

8.2. Projection and Information Balance

A distinctive aspect of DTT is its dual-level temporal ontology: matter arises as localized excitations of the inner-time projection. This interpretive framework is closely aligned with holographic bit-mode balance derivations [

21], which regard

as an equilibrium between surface information and interior modes. In both cases, the constant emerges from a fundamental ratio between projected and projecting structures.

8.3. Parameter-Free Determinism

Another point of intersection is methodological: DTT, the Kosmoplex deterministic framework [

19], and the granular charge model [

16] all claim to produce

without free parameters. Each treats the constant not as contingent but as a necessary outcome of deeper combinatorial or structural principles.

8.4. Numerical and Number-Theoretic Structures

Finally, DTT emphasizes the emergence of the decimal factor (10) from binary projection over three dimensions (0+1+3+7), linking

to intrinsic number structures. This perspective resonates with approaches that express

in terms of transcendental and irrational constants such as

and

[

24]. Both suggest that

is rooted in unavoidable numerical identities.

9. Conclusion

We have presented a derivation of the fine-structure constant based on the Duality of Time Theory, where space emerges from discrete inner-time cycles projected into outer time. The integer value arises deterministically from binary spinor multiplicities combined with a minimal radix structure required for dimensional projection. A small curvature-induced holonomy correction then shifts this idealized value to , in agreement with experimental measurements. Rigorous error estimates indicate that higher-order terms remain negligible at the scale, well below current experimental limits.

This framework demonstrates that need not be treated as a free empirical parameter but can be derived from the intrinsic combinatorial and geometric properties of temporal projection. While the model is still preliminary, it highlights a potential route toward parameter-free derivations of other constants such as Planck’s constant, the elementary charge, and possibly gravitational couplings. Future work should focus on formalizing the mathematical structure of inner-time dynamics and testing whether the approach yields independent predictions that can be distinguished from existing quantum field theory.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

The present work builds upon the foundational insights of the Single Monad Model (SMM) and the Duality of Time Theory (DTT), originally developed by the author in his doctoral dissertation and subsequently advanced through independent research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author employed OpenAI tools to assist in clarifying language, enhancing structure, and refining both the philosophical and technical presentation of ideas. All content was thoroughly reviewed and edited by the author to ensure accuracy, coherence, and originality. The author assumes full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

References

- A. Allehabi and colleagues. High-accuracy optical clocks with sensitivity to the fine-structure constant variation based on sm10+. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics, 2024. arXiv:2404.00854.

- A. Allehabi and colleagues. High-accuracy optical clocks with sensitivity to the fine-structure constant variation. arXiv preprint, 2025. arXiv:2506.18328.

- Bernard Carr. Anthropic Principle: From Philosophical Controversy to Experimental Science. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants. 2022 codata recommended values of the fundamental physical constants. 2022. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/index.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- P. A. M. Dirac. The cosmological constants. Nature, 139(3512):323, 1937. [CrossRef]

- R. Doe. Golden function model for deriving the fine-structure constant. SSRN Preprint, 2025.

- Arthur S. Eddington. The Philosophy of Physical Science. Cambridge University Press, 1939.

- Richard P. Feynman. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Alfred Gray. The volume of a small geodesic ball of a riemannian manifold. Michigan Mathematical Journal, 20(4):329–344, 1973.

- Michael B. Green, John H. Schwarz, and Edward Witten. Superstring Theory. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- P. Haahan. Calculating α as an emergent constant from wavefunction geometry. Medium.com, 2025.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef. The Single Monad Model of the Cosmos: Ibn Arabi’s View of Time and Creation. Routledge, 2017.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef. Duality of Time: Complex-Time Geometry and Perpetual Creation of Space. CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2019.

- M. Heydarizadmotlagh and colleagues. Precision measurement of helium fine-structure splitting. Physical Review Letters, 132:163001, 2024.

- H. Blaine Lawson and Marie-Louise Michelsohn. Spin Geometry. Princeton University Press, 1989.

- K. Lee. Granular charge model and a first-principles derivation of the fine-structure constant. Zenodo, 2025.

- P. Lemos and colleagues. A search for the fine-structure constant variation using fast radio bursts and supernovae data. arXiv preprint, 2024. arXiv:2406.11691.

- P. Lemos and colleagues. Using fast radio bursts and supernovae data to probe fine-structure constant variations. arXiv preprint, 2025. arXiv:2506.18328.

- J. Macedonia. A first-principles derivation of the fine-structure constant from the axioms of kosmoplex theory. Preprints.org, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Morel, Z. Yao, P. Cladé, and S. Guellati-Khélifa. Determination of the fine-structure constant with an accuracy of 81 parts per trillion. Nature, 588(7836):61–65, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Nagy. A first-principles derivation of the fine-structure constant from holographic bit-mode balance. arXiv preprint, 2025. arXiv:2404.00854.

- Joseph Polchinski. String Theory, Volume 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Joseph Polchinski. String Theory, Volume 2: Superstring Theory and Beyond. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- J. Smith. A high-precision mathematical expression for the fine-structure constant. SSRN Preprint, 2025.

- Arnold Sommerfeld. Zur quantentheorie der spektrallinien. Annalen der Physik, 356(17):1–94, 1916.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef. The dynamic formation of spatial dimensions in the inner levels of time, 2025. Preprint, version 1, posted 24 July 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).