1. Introduction

Modern physics rests on two pillars: General Relativity (GR), which models spacetime as a smooth differentiable manifold curved by energy and momentum [

1,

2], and Quantum Mechanics (QM), which describes matter and fields in discrete states [

3,

4]. Despite their successes, GR and QM remain incompatible in extreme regimes such as near singularities or at the Planck scale [

5,

6]. This tension motivates alternative frameworks that reconceptualize spacetime and its relation to quantum structures.

Historically, mathematics and geometry have been grounded in the ideal of continuity, from the Euclidean tradition [

7] and the calculus of Newton and Leibniz [

8,

9], to modern analysis based on infinitesimals and limits [

10]. By contrast, physics at the quantum scale demands discreteness, quanta, and finite transitions [

11,

12]. Reconciling these apparent opposites—continuity and discreteness—remains one of the deepest challenges in the philosophy of physics [

13,

14].

Non-commutative geometry (NCG), pioneered by Connes [

15], provides a natural mathematical framework for unifying discrete and continuous aspects of physical reality. By replacing commutative coordinate algebras with non-commutative operator algebras, NCG encodes geometry algebraically in a way that reflects quantum principles, particularly the Heisenberg uncertainty relation. At the Planck scale, where spacetime may be fundamentally quantized, such structures become indispensable for reconciling discreteness with continuity. Non-commutative geometry guarantees a minimal length scale and avoids singularities by replacing pointwise spacetime with algebraic and spectral structures, making it well-suited for Planck-scale physics.

In this context, the Duality of Time Theory (DTT) [

16], grounded in the Single Monad Model (SMM) [

17], offers an ontological realization of non-commutative geometry. The SMM postulates sequential re-creation in inner time, and in DTT the core operators that generate these cycles and project them into outer-time flow are intrinsically non-commutative. This captures the algebraic tension between re-creation and observed continuity. Non-commutativity here is not externally imposed but arises directly from temporal ontology: spacetime is not primary but emergent, with geometry unfolding from nested temporal dynamics.

As we shall demonstrate in

Section 7, the stability of emergent space within the SMM/DTT framework is guaranteed only when its operator algebra is both associative and non-commutative. This Minimal Stability Theorem provides a structural explanation for why precisely three spatial dimensions persist, linking dimensionality directly to algebraic coherence in temporal re-creation.

This perspective situates SMM/DTT within the broader family of emergent-spacetime approaches, yet it remains distinct in both logic and ontology. Loop quantum gravity encodes non-commutativity through holonomy–flux algebras that discretize geometric areas and volumes [

18], causal set theory replaces the manifold with discrete partially ordered sets capturing causal relations [

19], and tensor-network holography reconstructs geometry from entanglement patterns organized through non-commutative tensor contractions [

20]. These approaches employ non-commutativity as a structural or mathematical tool introduced to model quantum geometry. By contrast, SMM/DTT grounds non-commutativity in the ontology of time itself: the algebra of inner-time cycles and their projection into outer time is intrinsically non-commutative, reflecting the ordered yet recurrent nature of temporal re-creation. In this way, the stability of three-dimensional space, the quantization of mass and charge, and the emergence of gauge symmetries all follow as consequences of temporal algebra rather than as postulated geometric constraints.

In this work, we formulate these ideas within the rigorous framework of NCG, employing Connes’ spectral triple construction [

15,

21,

22], which has already been applied to unify gauge symmetries and gravity. Our contribution situates SMM/DTT in this landscape, offering a time-grounded alternative to the conventional geometric-first paradigm.

2. The Foundations of the SMM/DTT Framework

The Duality of Time Theory (DTT) provides a novel ontological and mathematical framework for the emergence of space, matter, and motion. It is grounded in the Single Monad Model (SMM), which posits that existence is being continuously and sequentially re-created at each instant of normal time. This principle unifies discreteness and continuity within a coherent temporal ontology.

The SMM itself was inspired by profound philosophical interpretations of the “Oneness of Being,” reformulated for modern scientific discourse [

17]. Its central thesis is that all multiplicity in the universe arises from the ongoing re-creation of a single fundamental entity—the Monad. The Monad is not a physical particle but an ontological principle, giving rise to diversity through temporal unfolding. Every physical event or particle can thus be understood as a projection of the Monad across successive temporal cycles.

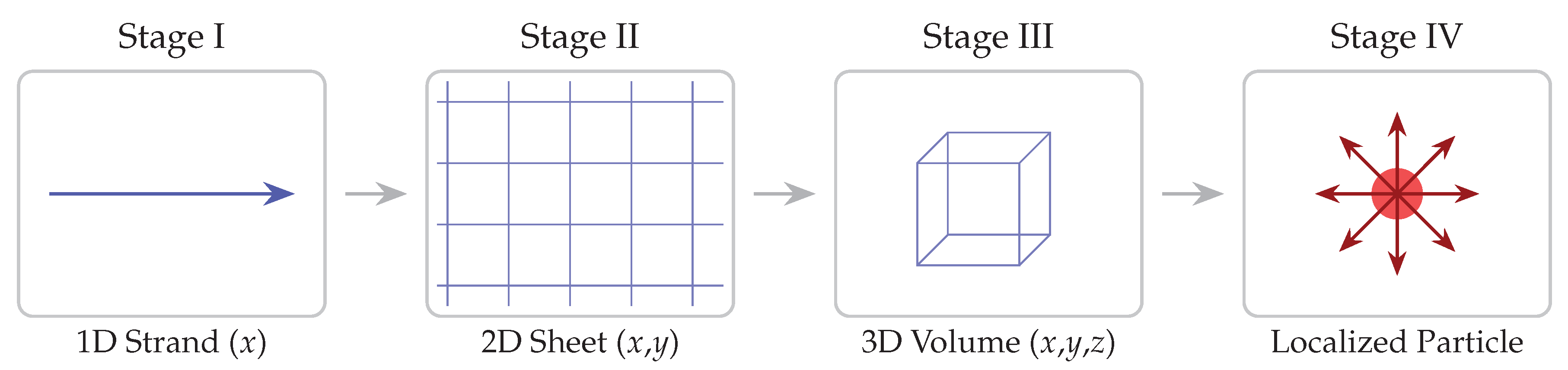

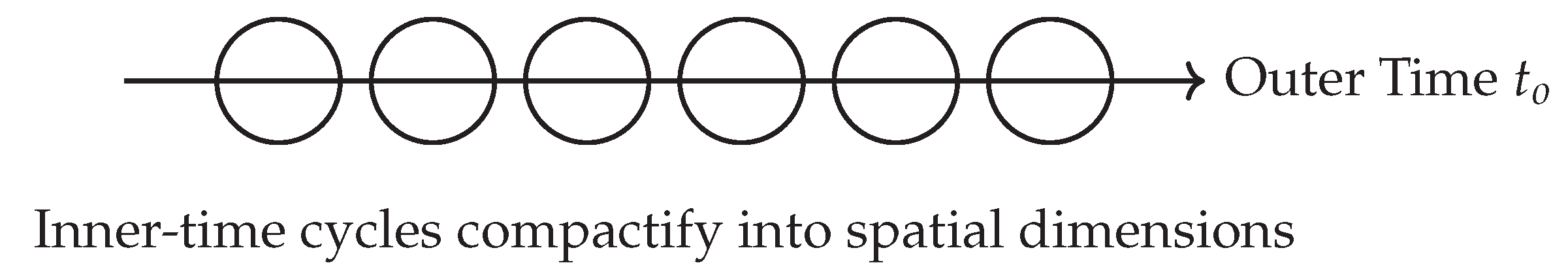

Within this framework, spatial dimensions are generated hierarchically by inner-time cycles: one-dimensional structures emerge from the first two cycles, two-dimensional planes from the next two, and full three-dimensional space from six cycles, while the seventh manifests as outer time. This ontology motivates a hyperbolic complex-time geometry, where one axis corresponds to discrete inner cycles and the other to continuous outer flow.

The discreteness of re-creation explains why physical systems evolve in quantized steps, while the coherence of cycles accounts for the apparent continuity of classical phenomena. In this way, the model provides a philosophical foundation for bridging quantum discreteness with macroscopic continuity.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the inner-time projection process and the sequential formation of spatial dimensions.

2.1. The Foundational DTT Postulate

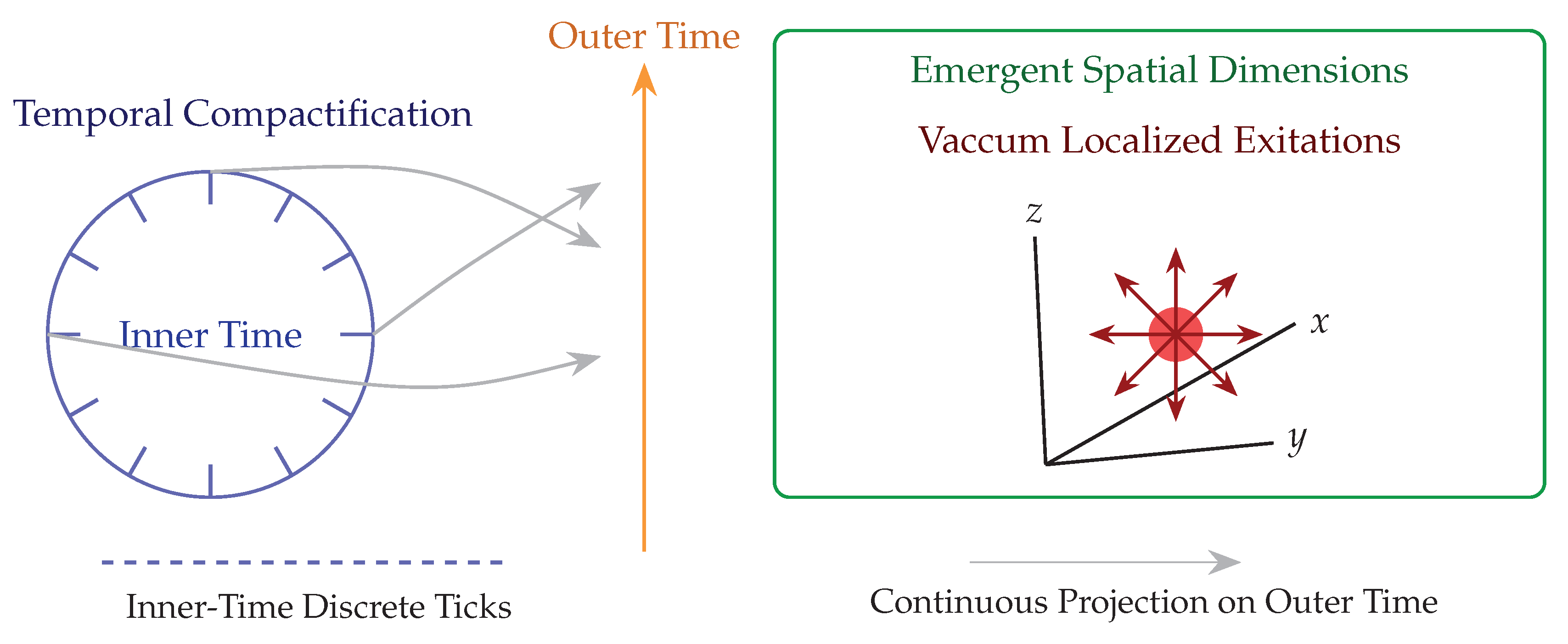

The central postulate of DTT states that at every instant of outer (imaginary) time, spatial dimensions are re-created through a chronological sequence of inner (real) time layers, forming nested temporal hierarchies. This dual structure distinguishes two interwoven levels of time:

- (1)

Inner Time: Compactified cycles that re-create existence at each instant. At this level, time is discrete, cyclic, spectral, and foundational.

- (2)

Outer Time: The extended, continuous unfolding of events that manifests as the observable flow of time in physics and perception.

Accordingly, this dual structure is expressed as a hyperbolic split-complex flow:

where

counts discrete inner-time ticks, while

denotes continuous outer time. Each full sequence of inner ticks constructs a three-dimensional vacuum state, which is then continuously projected along the outer-time axis. Localized perturbations within this re-created vacuum give rise to energy, mass, and elementary particles.

This dual structure offers a spectral perspective on the tension between discreteness and continuity in physics. Spatial dimensions emerge dynamically from the compactification of inner-time cycles (

Figure 3), while outer-time organizes these emergent structures into observable phenomena [

16]. The resulting complex-time geometry—combining inner (real) and outer (imaginary) components—provides a natural mathematical language for describing this duality.

Observable dynamics, whether described by Schrödinger evolution or Einstein field equations, are interpreted as emergent from accumulated inner-time cycles. These events form a directed, ordered sequence and naturally give rise to a non-commutative temporal algebra.

In this framework, the algebra is generated by projection operators representing inner-time re-creation states, acting on a Hilbert space of temporal configurations. The Dirac operator D acts as a spectral gradient across these states, encoding inner-time frequencies whose growth determines emergent geometric quantities. Embedding this dual-time logic into Connes’ spectral triple formalism provides a rigorous algebraic account of emergent geometry and opens pathways toward reconciling quantum physics with a complex-time ontology.

2.2. Implications for Physics

Unlike conventional models that treat space and time as fundamental, DTT posits the primacy of time as the source from which spatial dimensions, matter, and interactions emerge. This shift carries several consequences:

Origin of Spatial Dimensions: Dimensions emerge from the compactification of inner-time cycles, rather than being postulated a priori. This resonates with other emergent-spacetime approaches in quantum gravity, but here the mechanism is explicitly temporal [

16].

Mechanism for Quantization and Entanglement: Discrete re-creation naturally accounts for quantization, entanglement, and coherence, with quantum phenomena interpreted as projection dynamics across nested temporal layers [

23,

24].

Mass, Inertia, and Vacuum Energy: DTT derives inertia and mass generation from spectral properties of inner-time operators. Vacuum energy and the cosmological constant problem are addressed through projection density, avoiding fine-tuning issues of metric-based models [

25,

26].

Reformulation of Physics via Projection Dynamics: Fundamental physics is recast in terms of projection dynamics, where inner-time operators play a role analogous to field operators in quantum theory, linking non-commutative geometry with temporal ontology [

15,

21,

22].

Bridging Continuity and Discreteness: By reconciling mathematical continuity with physical discreteness, DTT provides an ontological foundation for unifying relativity and quantum mechanics [

5,

8,

9,

10].

Connections to Open Problems: The spectral properties of inner-time operators connect directly to major open problems, including the Yang–Mills mass gap and the Riemann Hypothesis [

27,

28,

29]. These links will be explored further in

Section 8.

This foundation paves the way for embedding SMM/DTT into non-commutative geometry, where spectral triples formalize the interplay of operators, states, and emergent metric structures, and where physical constants and interactions can be derived from temporal constructs rather than imposed externally.

2.3. From Temporal Re-Creation to Non-Commutative Algebra

The core innovation of SMM/DTT lies in treating re-creation events as primitive ontological operations. Within non-commutative geometry, this is modeled by an operator algebra

acting on a Hilbert space

, generated by a sequence of orthogonal projection operators

indexed by discrete inner-time steps

:

Each projection represents a holistic ontological state—a complete re-instantiation of the universe at a specific cycle. These projections form a temporally ordered sequence directed by inner-time flow.

While the projections themselves commute, non-commutativity arises with temporal transition operators. Define the shift operator

U and its adjoint

acting on the canonical basis

of

by

and the inner-time generator

T by

where

is the fundamental frequency of the inner temporal cycle. These operators obey the commutation relations

which mirror the canonical commutation relations of quantum mechanics and encode the directed, irreversible nature of inner time in DTT.

To capture internal symmetries, the algebra may be enriched by phase operators

, assigning charge-like properties to each re-creation event. Outer-time evolution is described by a self-adjoint Hamiltonian

acting on the continuous time space

. The total Hilbert space is then

and the complete algebra

is generated by

. This algebra forms the foundation of the non-commutative structure of complex-time space.

In Section ??, we extend this framework to construct a spectral triple in the sense of Connes, thereby endowing time itself with a geometric, operator-theoretic structure.

3. Comparison with other Emergent Spacetime Theories

The SMM/DTT framework and its spectral formulation contribute to a growing body of research exploring the emergence of spacetime from algebraic, quantum, and pre-geometric foundations. Here we contextualize this approach within key directions in the literature and highlight conceptual distinctions.

3.1. Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG)

Loop Quantum Gravity discretizes spacetime geometry via spin networks, where geometric operators have quantized spectra [

30,

31]. The key structure is a holonomy–flux algebra that encodes the parallel transport and area/volume elements on a background-independent space. Unlike LQG, which builds geometry from quantized flux lines in 3D space, SMM/DTT derives spatial dimensions from inner-time cycles and spectral operator growth. Both models emphasize discreteness, but DTT roots it in a temporal ontology rather than spatial triangulations.

3.2. Causal Set Theory (CST)

CST posits that spacetime is a discrete, partially ordered set representing causal relations [

32]. Geometry emerges statistically from the order structure. Like DTT, CST treats temporal precedence as fundamental. However, CST does not use operator algebras or spectral triples, whereas DTT embeds temporal generation into Connes’ non-commutative geometric formalism, allowing direct connections to gauge theory and quantum field spectra.

3.3. Tensor Networks and Holography

Tensor networks and holographic entanglement formalisms reconstruct emergent space from quantum entanglement patterns (e.g., MERA, AdS/CFT) [

33]. These models often exploit non-commutative tensor contractions to encode curvature and dimension. While DTT shares the goal of deriving geometry from non-spatial inputs, it uses spectral algebra rather than entanglement entropy as the fundamental mechanism. The re-creation process of DTT differs ontologically and algebraically from entanglement-driven networks.

3.4. Spectral Action Models

The non-commutative geometry (NCG) approach of Connes and Chamseddine derives the Standard Model and gravity from a spectral triple over a finite internal space and a continuous spacetime manifold [

34,

35]. The key distinction is that Connes’ approach postulates spacetime geometry and embeds internal symmetries via matrix algebras, while SMM/DTT inverts this logic: spacetime itself is emergent from temporal spectral dynamics. Your model thus offers a "time-first" variant of the spectral paradigm.

3.5. Group Field Theory and Matrix Models

Group Field Theory (GFT) and matrix/tensor models describe spacetime as a condensate of pre-geometric degrees of freedom [

36]. These models also use spectral methods (e.g., Laplacians on group manifolds) to encode geometric observables. DTT contributes to this family with a distinct temporal generator algebra, suggesting a spectral gap as the origin of particle mass and dimensional stability. The stability mechanism of DTT via associativity and non-commutativity offers a new constraint not previously explored in GFT.

3.6. Quantum Graphity and Other Pre-Geometric Models

Quantum graphity and similar frameworks propose that geometric space arises from symmetry-breaking in non-spatial networks [

37]. These models appeal to combinatorial and algebraic phase transitions. DTT differs in grounding geometry in **ordered spectral time**, rather than emergent locality from undirected graphs. However, the shared interest in dynamic topology invites comparative studies.

3.7. Comparison Summary

Table 1.

Comparison of key features across emergent spacetime frameworks. SMM/DTT is distinct in deriving geometry, gauge symmetries, and dimensionality from a spectral algebra of time.

Table 1.

Comparison of key features across emergent spacetime frameworks. SMM/DTT is distinct in deriving geometry, gauge symmetries, and dimensionality from a spectral algebra of time.

| - |

Time |

Spectral |

Geometry |

Dimensionality |

| Framework |

Primary? |

Methods |

Emergent? |

Explained? |

| Loop Quantum Gravity |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Tensor Networks |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Group Field Theory |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Quantum Graphity |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Spectral Action (NCG) |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

| Causal Set Theory |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| SMM/DTT (this work) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

4. Non-Commutative Framework for Complex-Time Space

We now construct a non-commutative representation of dual-time space. The temporal Hilbert space is defined as

where

spans the discrete inner-time eigenstates

and

encodes the continuous outer-time evolution.

4.1. Operator Structure

We introduce three fundamental operators:

with

denoting the fundamental inner-time frequency.

These satisfy non-trivial commutation relations:

for constants

determined by representation choices and scaling. Together,

generate a non-commutative associative algebra

.

4.2. Self-Adjointness and Operator Domains

On , the operator T acts multiplicatively and U is a unitary shift. On , is essentially self-adjoint on the Schwartz space .

The composite Hilbert space admits a dense domain

on which all operators are well-defined. This provides the foundation for constructing self-adjoint extensions of the Dirac operator in the next section.

5. Spectral Triple Construction

A spectral triple provides a generalization of a Riemannian manifold to non-commutative geometry, encoding geometrical data in the algebraic and spectral properties of operators on a Hilbert space. In the context of the SMM/DTT framework, this triple formalizes the emergence of geometry from the algebra of inner and outer time operators, with the Dirac operator D capturing both the discrete and continuous components of temporal evolution.

5.1. Algebra

Let be the involutive unital *-algebra generated by the following operators:

Orthogonal projections representing re-creation states at inner-time step n

The unilateral shift operator , with adjoint

The diagonal inner-time generator , where is a fixed fundamental frequency

The outer-time Hamiltonian acting on smooth functions in

Phase operators , encoding internal symmetries

These operators satisfy non-trivial commutation relations:

The algebra is represented on the Hilbert space defined below and acts via bounded or unbounded densely defined operators.

5.2. Hilbert Space

We define the Hilbert space as the tensor product:

where:

We define a common dense domain for all unbounded operators as:

where

is the Schwartz space. This domain is dense in

and invariant under all operators in

.

5.3. Dirac Operator D

We define the Dirac operator as:

where

are fixed Clifford matrices satisfying:

with

the Minkowski metric. The operator

D acts on the spinor space

, and is initially defined on

.

5.3.1. Essential Self-Adjointness

Each term in D has the following properties:

is essentially self-adjoint on

T is a diagonal multiplication operator on , hence self-adjoint

is bounded and self-adjoint on

Since T and H are self-adjoint on their respective domains and commute with on , and since is invariant under all terms, it follows that:

Proposition 5.1. The Dirac operator D is symmetric and essentially self-adjoint on , and therefore admits a unique self-adjoint extension.

5.3.2. Compact Resolvent

The spectrum of T consists of isolated eigenvalues , which diverge as . The operator H has continuous spectrum, but in bounded subspaces (e.g., periodic functions), its restriction yields discrete modes.

Since T has discrete spectrum, H is essentially self-adjoint, and U is bounded, it follows that D has discrete spectrum with eigenvalues accumulating only at infinity. Thus:

Proposition 5.2. The Dirac operator D has compact resolvent, i.e., for all .

5.3.3. Bounded Commutators

To satisfy the spectral triple condition

for all

, we compute the basic commutators:

for some real constants

. Each of these is bounded on

, and since

is generated by compositions and combinations of these operators, it follows that:

Proposition 5.3. For all , the commutator extends to a bounded operator on .

5.4. Spectral Action and Physical Interpretation

Following Connes’ spectral action principle, we define the action functional:

where

f is a positive cut-off function and

is a high-energy scale. The eigenvalues of

D encode geometric and physical data:

Frequencies of inner-time cycles determine rest mass:

Phase operators generate internal symmetries, with gauge interactions arising from inner fluctuations of D

Gauge curvature is given by , with , for ,

This structure reproduces key features of the Standard Model and gravitational interactions, embedding them into a time-generated operator algebra.

5.5. Philosophical Interpretation

The spectral triple is not only a formal mathematical structure but a conceptual bridge linking temporality to physical structure. The algebra encodes the logic of re-creation, while the operator D encodes the frequency content of the inner-time cycles that give rise to mass, charge, and geometry. From this perspective, space and physical fields emerge not as fundamental, but as spectral projections from the more primitive layer of temporal generation.

6. Spectral Geometry of Temporal Space

The spectral triple constructed in Section ?? provides a rigorous framework for interpreting geometry in a non-commutative and temporally emergent setting. In classical Riemannian geometry, distances are derived from the metric tensor on a smooth manifold. In non-commutative geometry, by contrast, distance is defined spectrally through the Dirac operator D.

Using Connes’ spectral distance formula, the separation between two pure states associated with

is

where the supremum is taken over normalized vectors

. This yields a generalized notion of distance that depends not on point-set structure, but on the algebra of operators and their commutators with

D.

In the DTT framework, a and b may represent projections onto different inner-time states, e.g. and . The spectral distance between these encodes the separation between their corresponding re-creation cycles. Geometry thus becomes an algebraic manifestation of temporal generation.

As outer time

t advances, new projections

emerge from the Monad. The observer experiences a continuously re-generated world in which spatial properties are encoded in the spectral pattern of temporal recurrence.

Figure 3 illustrates how successive inner-time projections

accumulate into an emergent spatial geometry along the outer-time axis.

6.1. Dimensionality from Spectral Growth

Spectral geometry also extracts dimensionality from the growth of eigenvalues. Let

denote the eigenvalue counting function:

The spectral dimension

d is defined by the asymptotic scaling

The asymptotic growth of the eigenvalues provides a concrete diagnostic of emergent dimensionality. If for large n, the eigenvalue counting function scales as , where d defines the spectral dimension of the emergent geometry. In the DTT framework, d reflects the density and structure of re-creation cycles encoded in the Dirac spectrum. For a physical universe, is expected to emerge naturally, recovering three spatial dimensions as a spectral feature of temporal recurrence. Different spectral growth laws correspond to dimensional flow: for instance, a linear spectrum yields , while a cubic-root spectrum gives .

Corrections such as logarithmic factors may induce high-energy dimensional running. Physically, defines effective mass via , while phase factors in the eigenstates encode gauge charges, linking temporal structure to internal symmetries. This demonstrates how macroscopic geometry is encoded in the microscopic scaling of temporal re-creation frequencies, unifying discreteness and continuity within a spectral ontology.

This section has emphasized the geometric interpretation. In the next section, we show how physical observables also arise from the same spectral structure.

6.2. Spectral Derivation of Physical Observables

Building on the spectral-geometric picture, we now examine how mass, charge, and gauge structure emerge from the spectrum of temporal operators in the dual-time framework.

6.2.1. Mass and Energy from Spectral Frequency

The eigenvalues

of

D may be interpreted as temporal frequencies of inner-time cycles. By analogy with

, we define the rest mass of a state as

making mass a spectral property rather than an intrinsic parameter.

Explicitly, if the inner-time generator acts as

for compactification radius

r, then

Mass and energy are therefore encoded in the spectral structure of time itself.

6.2.2. Charge and Gauge Symmetries from Shift Operators

Phase-modified projections

generate

transformations on temporal states. The shift operator

U admits characters

which implement discrete phase rotations. Charge thus acquires a spectral origin through the algebra

.

Gauge symmetries follow from inner fluctuations of

D:

The curvature

then encodes field strengths. Depending on the tensor structure of

, higher gauge groups emerge, e.g.

This provides a temporal–algebraic origin for the internal symmetries of the Standard Model.

6.2.3. Comparison with the Spectral Action Framework

Unlike the Connes–Chamseddine spectral action, where geometry is fundamental and matter is derived, the present framework asserts:

Temporality is ontologically primary,

Mass, charge, and interactions emerge from projection dynamics of time,

Spectral gaps arise from compactified temporal operators rather than external cutoffs.

In this way, the spectral triple formalism yields a bottom-up derivation of physical observables from the algebra of time itself.

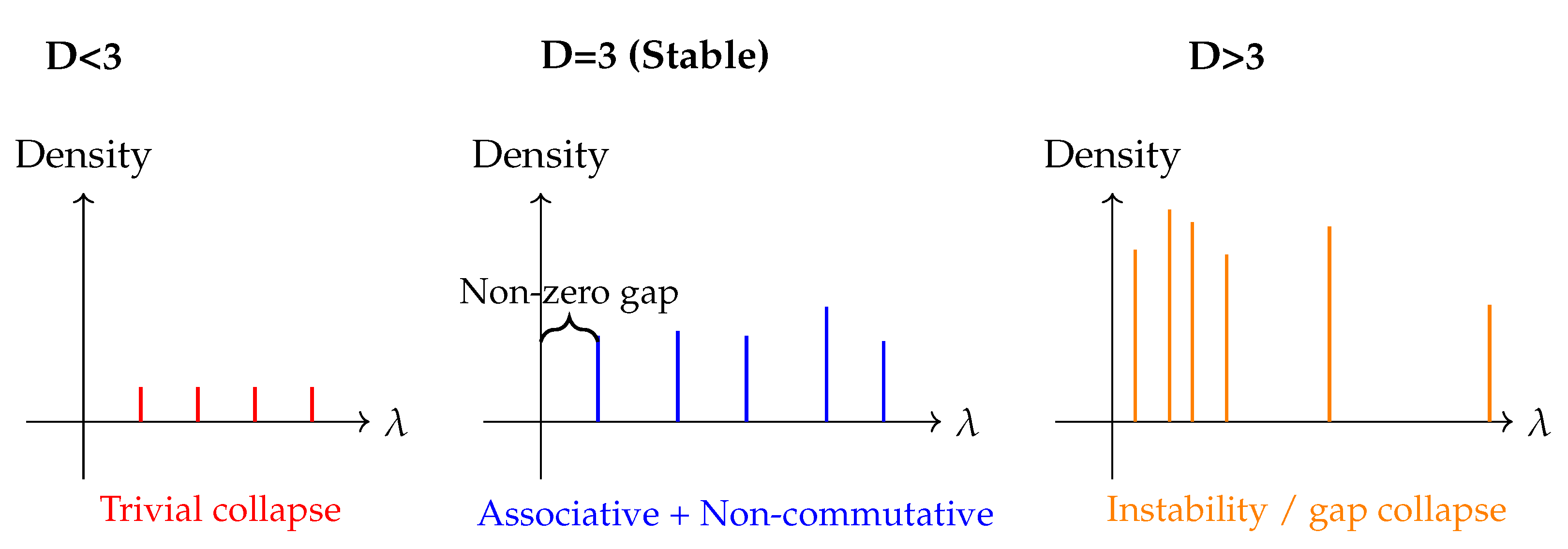

7. The Algebraic Basis for the Stability of 3D Space

A fundamental question for any emergent-spacetime framework is why the universe exhibits precisely three extended spatial dimensions. Within the SMM/DTT framework, this issue is addressed by the Minimal Stability Theorem. We argue that stable spatial geometry arises only when the underlying operator algebra is both associative, ensuring the coherence of nested temporal processes, and non-commutative, generating the spectral richness required for quantization. This algebraic balance uniquely stabilizes the emergent geometry at three dimensions: fewer dimensions collapse into trivial commutative structures, while higher-dimensional extensions require non-associative algebras that lead to instability. In this way, the stability of 3D space is not a contingent fact, but a structural consequence of the underlying algebra of SMM/DTT.

This balance between associativity and non-commutativity not only explains why space stabilizes uniquely at three dimensions, but also implies testable spectral signatures: departures from the associative–non-commutative regime predict vacuum instabilities, collapse of spectral gaps, or anomalous dimensional flow at high energies. Such effects, if observed, would provide empirical access to the underlying temporal algebra and its role in shaping physical reality.

7.1. Temporal Algebraic Requirements

Let denote the algebra generated by the temporal operators of DTT: the inner-time generator T, the shift operator U, and the outer-time Hamiltonian H, along with their adjoints and phase extensions. For the emergent geometry to be physically viable, the algebra must satisfy two essential conditions:

-

Associativity: For any

,

This ensures that sequential temporal compositions yield unambiguous states. Associativity guarantees coherence of nested inner-time cycles and the consistency of projection dynamics.

-

Non-commutativity: There exist

such that

Non-commutativity reflects the ordered, irreversible nature of inner-time re-creation. In particular, encodes the algebraic tension between discrete succession and continuous flow, a structural feature indispensable to the DTT ontology.

Together, these two requirements ensure both the stability and the dynamical richness of emergent space: associativity prevents collapse of structure, while non-commutativity generates spectral content.

7.2. Minimal Stability Theorem (DTT Formulation)

Theorem 7.1 (Minimal Stability Theorem). Within the SMM/DTT framework, the emergent spatial geometry stabilizes if and only if its temporal operator algebra is both associative and non-commutative. Moreover, the unique dimension at which this balance is achieved is , corresponding to the minimal stable embedding of inner-time cycles into outer-time flow.

7.2.1. Supporting Lemmas

Lemma 7.2 (Necessity of Associativity).

If is not associative, temporal nesting becomes ambiguous. In particular, for operators ,

implies inconsistent projection outcomes, destroying coherent evolution. Therefore, associativity is necessary for global stability.

Lemma 7.3 (Necessity of Non-Commutativity).

If is commutative, then

In this case, the algebra reduces to trivial commuting projectors, eliminating the quantization of mass, charge, and energy. Hence non-commutativity is necessary for physical discreteness.

Lemma 7.4 (Dimensional Closure).

Let N denote the number of compactified inner-time cycles required to generate an extended spatial dimension. The emergent dimension d satisfies

with cycles , cycles , and cycles . At , the operator algebra closes consistently under associativity and maintains non-trivial commutators. For , closure requires non-associative relations (octonionic-type), inducing instability.

7.2.2. Proof Sketch of Theorem 7.1

Sketch For , the operator set is under-constrained. Enforcing associativity collapses non-commutativity, leading to trivial spectra without stable excitations. For , extension of the operator set requires non-associative closure (e.g. octonionic relations), which spoils coherent nesting of re-creation cycles. Thus stability fails unless , where both associativity and non-commutativity are simultaneously preserved. □

7.2.3. Corollaries and Physical Signatures

Corollary 7.5 (Dimensional Instability for ). If the emergent spatial algebra fails to be simultaneously associative and non-commutative, the corresponding geometry is dynamically unstable.

Corollary 7.6 (Spectral Gap Criterion). Stable three-dimensional geometry is characterized by a non-zero spectral gap in the Dirac spectrum of the temporal triple . Perturbations that reduce either associativity or non-commutativity predict:

vacuum instabilities (loss of coherence in re-creation cycles),

collapse of spectral gaps (massless or anomalously light modes),

dimensional flow at high energies.

Figure 4.

Spectral stability of emergent space as determined by the associative–non-commutative balance. Only in three dimensions does the temporal operator algebra yield a coherent, stable spectrum with a non-zero gap. Lower-dimensional cases collapse into trivial commutative structures, while higher-dimensional extensions become unstable due to non-associativity, leading to vacuum instabilities and spectral gap collapse. This predicts observable signatures of instability if the associative–non-commutative balance is perturbed, providing a possible empirical probe of the underlying temporal algebra.

Figure 4.

Spectral stability of emergent space as determined by the associative–non-commutative balance. Only in three dimensions does the temporal operator algebra yield a coherent, stable spectrum with a non-zero gap. Lower-dimensional cases collapse into trivial commutative structures, while higher-dimensional extensions become unstable due to non-associativity, leading to vacuum instabilities and spectral gap collapse. This predicts observable signatures of instability if the associative–non-commutative balance is perturbed, providing a possible empirical probe of the underlying temporal algebra.

7.3. Connections to Known Algebraic Structures

This result resonates with well-studied algebraic systems:

Matrix algebras are associative and non-commutative, forming the foundation of spectral triples in Connes’ non-commutative geometry.

Quaternions, the unique normed division algebra of dimension four, are associative and non-commutative, and intimately tied to three-dimensional rotations (via ).

Octonions are non-associative and correspond to unstable or higher-dimensional extensions, reflecting the failure of stability beyond three spatial dimensions.

Thus, the SMM/DTT prediction that stable emergent space requires an associative, non-commutative algebra not only explains why three dimensions are privileged but also aligns with deep mathematical constraints on division algebras and operator theory.

7.4. Physical Interpretation

The Minimal Stability Theorem formalizes the claim that the universe stabilizes in three spatial dimensions because only at this level do temporal re-creation cycles generate an operator algebra that is both associative (globally coherent) and non-commutative (spectrally rich). In this way, the dimensionality of space is not a contingent fact but a structural consequence of the algebra of time.

Corollary 7.7 (Dimensional Instability for ). If the emergent spatial algebra fails to be simultaneously associative and non-commutative, then the corresponding geometry is dynamically unstable. In particular, for one of the following occurs:

Loss of associativity

(e.g., non-associative extensions needed to close operators) ⇒ failure of coherent nesting of inner-time cycles, leading to projection ambiguity and breakdown of global states;

Collapse of non-commutativity

(commutator norms tend to zero) ⇒ vanishing spectral gaps and trivialization of mass/charge spectra.

Consequently, stable extended spatial geometry does not arise for .

Sketch For , the operator set is underconstrained: maintaining associativity forces commutators to trivialize, eliminating spectral gaps and obstructing stable excitations. For , closing the enlarged operator set while preserving nontrivial commutators generically requires non-associative or overcomplete relations, which spoil coherent nesting of temporal projections; this induces dynamical inconsistency in the re-creation sequence. Hence stability fails unless . □

Phenomenological Signatures and Tests.

The instability mechanisms above have observational consequences:

Vacuum instability / decoherence: Non-associative closures () predict accelerated loss of spectral coherence (off-diagonal suppression in temporal correlators), testable as excess dephasing in analogue simulators (photonic or superconducting lattices) implementing .

Spectral-gap collapse: Reduced non-commutativity () implies shrinking gaps in the D-spectrum; in effective field analogues this appears as softened dispersion or anomalously light modes.

Dimensional flow bounds: If logarithmic corrections induce high-energy dimensional running, stability requires flow back to in the infrared; this constrains permissible asymptotics (e.g., ) to avoid long-time decoherence.

Remark (Quaternionic cue).

The privileged role of echoes the associativity and non-commutativity of quaternions (linked to and 3D rotations), whereas octonionic () structures are non-associative and therefore incompatible with stable temporal nesting in DTT.

8. Connections to Foundational Open Problems in Physics and Mathematics

The spectral framework developed here enables fresh perspectives on several longstanding open problems in physics and mathematics. By replacing continuum assumptions with temporal operator dynamics, the dual-time spectral triple reformulates mass, energy, gauge symmetries, and geometry as spectral features of time itself. Below we outline its implications for five canonical challenges.

8.1. Yang–Mills Mass Gap

In conventional approaches, the Yang–Mills mass gap remains elusive because no non-perturbative mechanism guarantees a finite excitation spectrum. In the dual-time setting, however, the non-commutativity

implies bounded commutators

, producing an intrinsic spectral gap:

Here r is the compactification scale of inner-time cycles. Thus, the gap is non-perturbative and background-independent, matching the Clay Institute’s mass gap formulation but rooted in temporal ontology.

8.2. Riemann Hypothesis

We associate to the inner-time generator

T a spectral zeta function

and a determinant

. By introducing a modular symmetry operator

, we define a Hilbert–Pólya-type operator

whose spectrum conjecturally coincides with the imaginary parts of the non-trivial zeros of

. This proposal unifies Connes’ trace formula and the Berry–Keating

model within a temporal framework: primes correspond to oscillatory phases of projection dynamics, linking arithmetic to re-creation cycles.

8.3. Navier–Stokes Regularity

The existence and smoothness problem for Navier–Stokes can be rephrased spectrally. Let

denote fluid observables at cycle

n. Smooth flow corresponds to spectral coherence:

while singularities arise when decoherence between cycles becomes large:

Thus, turbulence and blow-up are interpreted as failures of temporal coherence rather than singular fields, offering a quantized operator perspective on fluid stability.

8.4. Black Hole Information

In this framework, black hole entropy reflects degeneracy in temporal spectra near critical inner-time frequencies. As cycles approach

(with

the Schwarzschild scale), overlaps decay:

suppressing temporal interference. Hawking radiation arises from outer-time phase fluctuations, while entropy counts indistinguishable spectral states:

This suggests a unitary spectral evolution in which information is preserved in temporal rather than spatial modes.

8.5. Cosmological Constant

Finally, the cosmological constant may be reinterpreted as a residual of global phase imbalance. With phase operators

, define

Dark energy then emerges as an interference effect of microscopic temporal phases, linking vacuum energy to projection density rather than fine-tuned metric contributions.

In summary, by grounding geometry, mass, and gauge symmetries in the spectral properties of dual time, the SMM/DTT framework offers new routes into problems that have resisted traditional approaches. Each is recast not on a spatial manifold, but within the algebraic logic of temporal re-creation.

9. Physical and Observational Predictions

The spectral structure of the Dirac operator D in the SMM/DTT framework gives rise to physically meaningful quantities that, in principle, are testable or constrainable by observation. We outline below key examples that connect the formal spectral data to empirical scales and phenomena.

9.1. Mass Scales from Spectral Gaps

Let

denote the

n-th eigenvalue of

D. We define rest mass via the standard Planck relation:

In this model, mass is not an externally inserted parameter but emerges from the **frequency content** of inner-time cycles. The lowest non-zero eigenvalue corresponds to the lightest possible massive excitation.

9.1.0.3. Prediction:

A non-zero **spectral gap**

implies a minimum mass scale

below which no particle states exist. This can potentially be tied to neutrino mass lower bounds or dark sector thresholds:

9.2. Spectral Density and Dimensionality Flow

The asymptotic behavior of the spectral counting function

defines the **spectral dimension**

d:

This allows for the possibility of **dimensional flow** at high energy scales, where may decrease or increase. Such flow could manifest in:

9.2.0.4. Prediction:

If the spectral growth law shifts from (3D) to a different power, it may result in observable **anomalies in high-energy particle spectra or gamma-ray bursts**.

9.3. Gauge Structure from Temporal Tensor Products

The internal gauge symmetries (U(1), SU(2), SU(3)) arise from **tensorial multiplicity of temporal modes**:

This allows prediction of the **minimal symmetry group** based on the spectral multiplicity of D.

9.3.0.5. Prediction:

Spectral clustering in the low-lying eigenmodes should reflect the charge group structure observed in particle physics. Deviations from this pattern (e.g., missing multiplicities) would imply modified gauge groups or symmetry breaking not captured by the Standard Model.

9.4. Cosmological Constant from Temporal Phase Variance

Define a phase operator

, with

encoding spectral phases. Then, the cosmological constant

can be estimated as:

Prediction:

If the temporal spectrum exhibits **non-vanishing variance in phase**, this yields a small but positive , in line with observations of dark energy. Fine-tuning problems are avoided since arises from global phase interference, not from ad hoc potential terms.

9.5. Signatures of Dimensional Instability

The Minimal Stability Theorem predicts that 3D space is stable due to the balance of associativity and non-commutativity. Perturbations away from yield:

Loss of spectral gap (ultralight or massless particles)

Vacuum instability (enhanced decoherence)

Dimensional flow (non-standard scaling of )

Prediction:

These could be observed as:

Softening of particle spectra near UV or IR cutoffs

Anomalous entanglement entropy growth in analogue systems

Running of effective dimensionality in cosmological or lattice gravity models

10. Conclusion and Outlook

In this work, we have developed a spectral triple over a hyperbolic complex dual-time space, embedding the Duality of Time Theory (DTT) within the operator-algebraic framework of non-commutative geometry. This construction unifies quantum discreteness and classical continuity within a layered temporal ontology: inner-time cycles encode discrete re-creation, while outer-time provides continuous evolution. The result is a temporally grounded foundation that dispenses with the need for an a priori spacetime background.

The spectral triple formalizes this structure. The algebra , generated by projections, phase shifts, and time-evolution operators, encodes the logic of re-creation and internal symmetries. The Hilbert space accommodates the dual temporal scales, while the Dirac operator D captures both discrete and continuous dynamics. This framework not only models temporal succession algebraically but also derives geometry, dimensionality, and physical observables from spectral properties alone.

We have shown that:

Mass and energy arise from the spectral compactification of inner-time, with eigenvalues of D interpreted as temporal frequencies yielding rest mass via dimensional analysis.

Gauge symmetries such as U(1), SU(2), and SU(3) emerge from representations and tensor products of temporal phase and shift operators, offering an intrinsic origin for internal charges and interactions.

Inertia and interactions can be interpreted through inner fluctuations of the Dirac operator, as in Connes’ spectral action framework, yielding curvature and field-theoretic structures without classical differential geometry.

Spectral gaps suggested by bounded commutators provide a candidate mechanism toward addressing the Yang–Mills mass gap via intrinsic time quantization.

Arithmetic structure appears through the spectral interpretation of Riemann zeta zeros, where a Hilbert–Pólya-type operator in dual-time geometry may realize the critical line spectrum.

Together, these results suggest that spacetime, matter, and interactions may be understood as emergent from the spectrum of temporal re-creation. The SMM/DTT framework thus offers a shift from geometric ontology to temporal generation—a move that may illuminate paradoxes of locality, causality, and the unification of quantum and gravitational regimes.

Future Directions

The framework invites a wide range of further investigations, both mathematical and physical:

Spectral Modeling and Simulation: Construct finite-dimensional approximations and numerical studies of to probe eigenvalue distributions, spectral gaps, and signatures of inner-time compactification.

Fundamental Constants and Cosmology: Derive quantities such as the fine-structure constant , Planck units, and the cosmological constant as spectral ratios or interference effects of temporal operators, linking microscopic dynamics to large-scale cosmology.

Standard Model and Beyond: Incorporate fermionic generations, chiral symmetry breaking, and Higgs-like interactions into higher-order temporal tensor sectors, potentially shedding light on flavor hierarchies and mass matrices.

Quantum Information and Decoherence: Investigate how inner-time cycles underlie entanglement, measurement, and information loss, with spectral decoherence providing a natural mechanism for the quantum-to-classical transition.

Mathematical and Experimental Foundations: Extend the study of using K-theory, cyclic cohomology, and index theory, while exploring analog realizations in photonic lattices, superconducting qubits, and synthetic gauge systems that could mimic temporal projection dynamics.

Ultimately, this work provides both a metaphysical reorientation of physics around temporality and a rigorous spectral framework capable of deriving and explaining fundamental structures. By rooting physical law in spectral coherence across time rather than geometric points in space, the DTT/SMM paradigm opens a coherent path toward unification—from quantum mechanics and field theory to cosmology and number theory.

References

- Einstein, A. The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity; Vol. 49, 1916; pp. 769–822.

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; W.H. Freeman, 1973.

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Oxford University Press, 1930.

- Bohr, N. The Quantum Postulate and the Recent Development of Atomic Theory. Nature 1928, 121, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity; Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Euclid. The Thirteen Books of the Elements, 1956.

- Newton, I. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica; Royal Society, 1687.

- Leibniz, G.W. Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis. Acta Eruditorum 1684. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. Non-standard Analysis; North-Holland, 1966.

- Planck, M. On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum. Annalen der Physik 1901, 4, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1927, 43, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, C.J. Lectures on Quantum Theory: Mathematical and Structural Foundations; Imperial College Press, 1995.

- Smolin, L. The Trouble with Physics; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

- Connes, A. Noncommutative Geometry; Academic Press, 1994.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The Duality of Time Theory; CreateSpace, 2017.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The Single Monad Model of the Cosmos; AuthorHouse, 2007.

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53–R152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R.D. Space-time as a Causal Set. Physical Review Letters 1987, 59, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swingle, B. Entanglement Renormalization and Holography. Physical Review D 2012, 86, 065007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Connes, A. The Spectral Action Principle. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1997, 186, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Suijlekom, W.D. Noncommutative Geometry and Particle Physics; Springer, 2014.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The Dynamic Formation of Spatial Dimensions in the Inner Levels of Time. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. Projection Coherence Reformulation of the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture. SSRN Electronic Journal 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. Emergent Gravity from Inner-Time Compactification: Deriving Newton’s Law and the Cosmological Constant from Temporal Geometry. SSRN Electronic Journal 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. Projection Coherence Reformulation of the Hodge Conjecture. SSRN Electronic Journal 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Clay Mathematics Institute. Millennium Prize Problems, 2000. Available at: http://www.claymath.org/millennium-problems.

- Edwards, H.M. Riemann’s Zeta Function; Dover, 2001.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. A Complex-Time Geometry for the Dynamic Formation of Spatial Dimensions and Its Implications for Quantum Gravity. Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity; Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R.D. Space-time as a causal set. Physical Review Letters 1987, 59, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swingle, B. Entanglement renormalization and holography. Physical Review D 2012, 86, 065007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Connes, A. The spectral action principle. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1997, 186, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Suijlekom, W.D. Noncommutative Geometry and Particle Physics; Springer, 2014.

- Oriti, D. Group field theory and loop quantum gravity. Philosophy Compass 2014, 9, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- T. Konopka, F. Markopoulou, L.S. Quantum graphity: A model of emergent locality. Physical Review D 2008, 77, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).