Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enterococcus faecalis Isolates and Susceptibility Testing

2.2. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis of Whole-Genome Sequences

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Antimicrobial Resistance

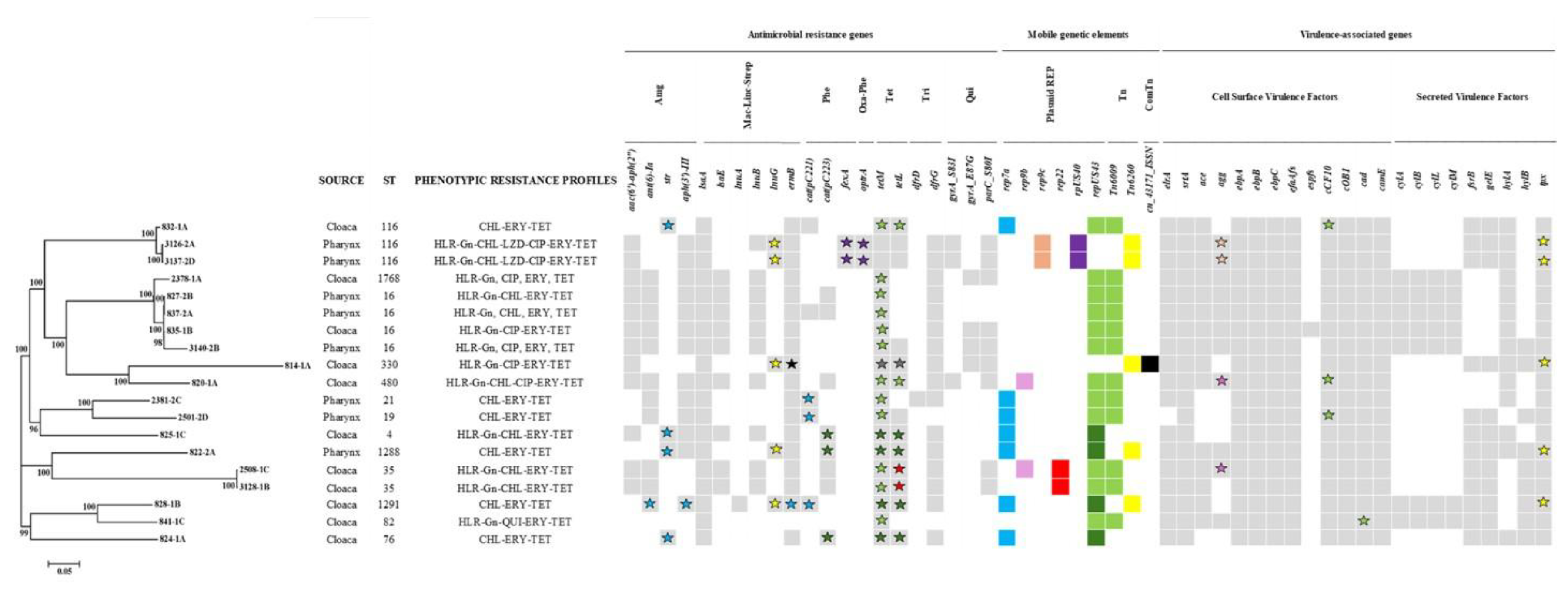

3.2. Molecular Characterization of the Isolates

3.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Mobile Gene Elements (Plasmids, Transposons, and Integrative and Conjugative Elements)

3.4. Virulence Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ARBs | Antibiotic-resistant bacteria |

| ARGs | AMR genes |

| HGT | Horizontal gene transfer |

| MGEs | Mobile genetic elements |

| HLR | High-level resistance |

| ECOFF | Epidemiological cut-off |

| ECVs | Epidemiological cut-off F values |

| MICs | Minimal inhibitory concentrations |

| WT | Wild-type |

| NWT | non-WT |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| STs | Sequence types |

| GD | Genetic diversity |

| CCs | Clonal complexes |

| DLVs | Double-locus variants |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| SNPs | Single-nucleotide polymorphisms |

| TET | Tetracycline |

| ERY-TET | Erythromycin- tetracycline |

| A/R | Antibiotic/reserpine |

| Tns | Transposons |

| ComTn | Composite transposons |

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (AMR Col). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization 2014.

- Dias, D. , Fonseca, C., Caetano, T., Mendo, S. Oh, deer! How worried should we be about the diversity and abundance of the faecal resistome of red deer? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 153831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolejska, M. , Guenther, I. Wildlife is overlooked in the epidemiology of medically important antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e0116719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.K. , Donato, J., Wang, H.H., Cloud-Hansen, K.A., Davies, J., Handelsman, J. Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, T. , Silva, N., Igrejas, G., Rodrigues, P., Micael, J., Rodrigues, T., Resendes, R., Gonçalves, A., Marinho, C., Gonçalves, D., Cunha, R., Poeta, P. Dissemination of antibiotic resistant Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli from wild birds of Azores Archipelago. Anaerobe 2013, 24, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vittecoq, M. , Godreuil, S., Prugnolle, F., Durand, P., Brazier, L., Renaud, N., Arnal, A., Aberkane, S., Jean-Pierre, H., Gauthier-Clerc, M., Thomas, F., Renaud, F. Antimicrobial resistance in wildlife. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień-Pyśniak, D. , Hauschild, T., Nowaczek, A., Marek, A., Dec, M. Wild birds as a potential source of known and novel multilocus sequence types of antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. J. Wildl. Dis 2018, 54, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhouani, H. , Silva, N., Poeta, P., Torres, C., Correia, S., Igrejas, G. Potential impact of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife, environment and human health. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, J.A. , Salgado-Caxito, M., Torres, C., Godreuil, S. Public health implications of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife at the One Health Interface. Med. Sci. Forum 2024, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Slotta-Bachmayr, L., Bögel, R., Camiña, C.A. The Eurasian Griffon vulture in Europe and the Mediterranean. Status Report & Action Plan. EGVWG; Salzburg, Austria, 2005.

- Pirastru, M. , Mereu,, P., Manca, L., Bebber, D., Naitana, S., Leoni, G.G. Anthropogenic drivers leading to population decline and genetic preservation of the Eurasian Griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 1038. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, G. , Bautista, L.M. Avian Scavengers as Bioindicators of Antibiotic Resistance Due to Livestock Farming Intensification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 2020 17, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, A.K. , Smith, R.K., Rush, S., Naveda-Rodriguez, A., Brooks, J.P. The role of New World vultures as carriers of environmental antimicrobial resistance. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G. Supplementary feeding as a source of multiresistant Salmonella in endangered Egyptian vultures. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, M.R. , Suárez-Pérez, A., Álamo-Peña, A., Valverde Tercedor, C., Corbera, J.A., Tejedor-Junco, M.T. Antimicrobial susceptibility of enterococci isolated from nestlings of wild birds feeding in supplementary feeding stations: the case of the Canarian Egyptian vulture. Pathogens 2024, 13, 855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EFSA). The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2011. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbroek, L. , Mac, K.N., Peters, J., Hultquist, L. Hazard potential from antibiotic-resistant commensals like Enterococci. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 2004, 51, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela, A.I. , Casas-Díaz, E., Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F., Serrano, E., Agustí, S., Porrero, M.C., Sánchez del Rey, V., Marco, I., Lavín, S., Domínguez, L. Estimation of cultivable bacterial diversity in the cloacae and pharynx in Eurasian Griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus). Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, S.R. , Kwong, S.M., Firth, N., Jensen, S.O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00088–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: A risk management tool for mitigating antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use. Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals, fourth edition. CLSI Approved Standard M31-A4; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1729 of 17 November 2020 on the monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and commensal bacteria and repealing Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU (2020/1729/EU). Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 8–21.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI Approved Standard M100-S15; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bast, D.J. , Low, D.E., Duncan, C.L., Kilburn, L., Mandell, L.A., Davidson, R.J., de Azavedo, J.C.S. Fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Contributions of type II topoisomerase mutations and efflux to levels of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 3049–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G. , Harel, J., Lacouture, S., Gottschalk, M. Genetic diversity of Streptococcus suis serotypes 2 and 1/2 isolates recovered from carrier pigs in closed herds. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2002, 66, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, M. , Sousa, A., Ramirez, M., Francisco, A.P., Carriço, J.A., Vaz, C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: Providing scalable data integration and visualization for multiple phylogenetic inference methods. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M. , Yuan, J., Lin, Y., Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasman, H. , Clausen, P.T.L.C., Kaya, H., Hansen, F., Knudsen, J.D., Wang, M., Holzknecht, B.J., Samulioniene, J., Roeder, B., Frimodt-Møller, N., Lund, O., Hammerum, A.M. LRE-Finder, a web tool for detection of the 23S rRNA mutations, and the optrA, cfr, cfr(B) and poxtA genes, encoding linezolid resistance in Enterococci from whole genome sequences. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 1473–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J. , Nash, J.H.E. MOB-suite: Software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genomics 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N. , Dehal, P.S., Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2 –Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnoli, G. , Bertelloni, F., Interrante, P., Ceccherelli, R., Marzoni, M., Ebani, V.V. Antimicrobial-resistant Enterococcus spp. in wild avifauna from central Italy. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.A.R. , Faria, A.R., Mendes, L.T., Merquior, V.L.C., Neves, D.M., Pires, J.R., Teixeira, L.M. The gut microbiota of wild birds undergoing rehabilitation as a reservoir of multidrug resistant enterococci in a metropolitan area in Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3849–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, W.P. , Sinwat, N., Bitrus, A.A., Angkittitrakul, S., Prathan, R., Chuanchuen, R. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene, and class 1 integrons of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis from pigs, pork and humans in Thai-Laos border provinces. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 18, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Literak, I. , Dolejska, M., Janoszowska, D., Hrusakova, J., Meissner, W., Rzyska, H., Bzoma, S., Cizek, A. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli bacteria, including strains with genes encoding the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and QnrS, in water-birds on the Baltic Sea coast of Poland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8126–8134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guenther, S. , Grobbel, M., Heidemanns, K., Schlegel, M., Ulrich, R.G., Ewers, C., Wieler, L.H. First insights into antimicrobial resistance among faecal Escherichia coli isolates from small wild mammals in rural areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3519–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Avizanda, G. , Blanco, B., Deault, T.L., Markandya, A., Virani, M.Z., Donázar, J.A. Supplementary feeding and endangered avian scavengers: Benefits, caveats and controversies. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, M. , Ramstad, S.N., Rudi, K., Porcellato, D., Ravi, A., Ludvigsen, J., das Neves, C.G., Tryland, M., Ropstad, E., Slettemeås, J.S., Telke, A.A. Plasmid-associated antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Escherichia coli in a high Arctic reindeer subspecies. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 26, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, S. , Kehrenberg, C., Doublet, B., Cloeckaert, A. Molecular basis of bacterial resistance to chloramphenicol and florfenicol. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engelen, E. , Mars, J., Dijkman, R. Molecular characterisation of Mycoplasma bovis isolates from consecutive episodes of respiratory disease on Dutch veal farms. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 298, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.L. Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, M. , Yasir, M., Al-Hindi, R.R., Farraj, S.A., Jiman-Fatani, A.A., Alawi, M., Azhar, E. Genomic analysis of multi-drug-resistant clinical Enterococcus faecalis isolates for antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors from the western region of Saudi Arabia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. , Lv, Y., Cai, J., Schwarz, S., Cui, L., Hu, Z., Zhang, R., Li, J., Zhao, Q., He, T., Wang, D., Wang, Z., Shen, Y., Li, Y., Feßler, A.T., Wu, C., Yu, H., Deng, X., Xia, X., She, J. A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2182–2190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A. , Jensen, L.B. Analysis of gyrA and parC mutations in enterococci from environmental samples with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 231, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuasi, G.R. , Dsani, E., Owusu-Nyantakyi, C., Owusu, F.A., Mohktar, Q., Nilsson, P., Adu, B., Hendriksen, R.S., Egyir, B. Enterococcus species: Insights into antimicrobial resistance and whole-genome features of isolates recovered from livestock and raw meat in Ghana. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1254896. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, K.J. , Rather, P.N., Hare, R.S., Miller, G.H. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 57, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munita, J.M. , Arias, C.A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, VMBF–0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W. , Huda, N., Kuroda, T., Mizushima, T., Tsuchiya, T. EfrAB, an ABC multidrug efflux pump in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3733–3738. [Google Scholar]

- Shiadeh, S.M.J. , Azimi, L., Azimi, T., Pourmohammad, A., Goudarzi, M., Chaboki, B.G., Hashemi, A. Upregulation of efrAB efflux pump among Enterococcus faecalis ST480, ST847 in Iran. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2020, 67, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweriebor, B.C. , Obi, L.C., Okoh, A.I. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance factors of Enterococcus spp. isolated from fecal samples from piggery farms in Eastern Cape, South Africa ecological and evolutionary microbiology. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoba, D.O. , Amoako, D.G., Akebe, A.L.K., Ismail, A., Essack, S.Y. Genomic analysis of antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus spp. reveals novel enterococci strains and the spread of plasmid-borne tet(M), Tet(L) and erm(B) genes from chicken litter to agricultural soil in South Africa. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.Q. , Wang, X.M., Li, H., Shang, Y.H., Pan, Y.S., Wu, C.M., Wang, Y., Du, X.D., Shen, J.Z. Novel lnu(G) gene conferring resistance to lincomycin by nucleotidylation, located on Tn6260 from Enterococcus faecalis E531. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 993–999. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, I.N. , Lozano, C., Zarazaga, M., Latorre-Fernández, J., Hallstrøm, S., Rasmussen, A., Stegger, M., Torres, C. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus from the nostrils of healthy hosts identifies zoonotic transmission. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Min, S., Sun, Y., Ye, J., Zhou, Z., Li, H. Characteristics of population structure, antimicrobial resistance, virulence factors, and morphology of methicillin-resistant Macrococcus caseolyticus in global clades. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggel, M. , Nüesch-Inderbinen, M., Jans, C., Stevens, M.J.A., Stephan, R. Genetic context of optrA and poxtA in florfenicol-resistant enterococci isolated from flowing surface water in Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0108321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivu, S. , Shourav, A.H., Ahmed, S. Whole genome sequencing reveals circulation of potentially virulent Listeria innocua strains with novel genomic features in cattle farm environments in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2024, 126, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H. Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S. , Silva, V., Dapkevicius, M.d.L.E., Igrejas, G., Poeta, P. Enterococci, from harmless bacteria to a pathogen. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jett, B.D. , Huycke, M.M., Gilmore, M.S. Virulence of Enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 7, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Class | Antimicrobial | No. of isolates with MIC of (μg/ml) | % non-WT isolates | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | ≥2056 | |||

| β-Lactam | AMP | <2 | 38 | 16 | > | 0 | |||||||||||||

| Quinolone | CIP | < | 3 | 35 | 9 | 1 | 2> | 6 | 14.3 | ||||||||||

| Macrolide | ERY | <10 | 8 | 5 | 2 | > | 31 | 58.9 | |||||||||||

| Aminoglycoside | GEN | <31 | 11 | 1 | 1a> | 12a | 25.0 | ||||||||||||

| Liopeptide | DAP | <1 | 4 | 39 | 12 | > | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Tetracycline | TET | <10 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 37> | 2 | 82.1 | |||||||||||

| TGC | < | 16 | 32 | 8 | > | 0 | |||||||||||||

| Phenicol | CHL | <2 | 38 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5> | 25.0 | |||||||||||

| Oxazolidinone | LZD | < | 8 | 45 | 1 | 2 | > | 3.6 | |||||||||||

| Streptogramin | SYN | <3 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 34 | 7 | > | 0 | ||||||||||

| Glycopeptide | TEI | <56 | > | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| VAN | <29 | 20 | 7 | > | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Antimicrobial resistance profile | Nº isolates showing the antimicrobial resistance profile (%) | ST (CC)3 |

|---|---|---|

| WT isolates | 10 (17.9) | ST4 (2; CC16); ST40 (1; CC16); ST441 (1; CC16); ST648 (4; CC16); ST1600 (1; CC860); ST1875 (1; CC863) |

| TET | 13 (23.2) 1 | ST9 (1; CC16), ST40 (1; CC16); ST59 (1; CC16); ST82 (1; CC16); ST200 (1; CC16); ST256 (2; CC16); ST268 (1; CC16); ST631 (1; CC631); ST699 (1; CC1567); ST706 (2; CC376); ST860 (1; CC860) |

| ERY-TET | 14 (25.0)1 | ST7 (1; CC16); ST16 (1; CC16); ST287 (2; CC287); ST300 (8; CC863); ST1287 (1; 1861) |

| GEN-ERY-TET2 | 2 (3.6) | ST16 (2; CC16) |

| CHL-ERY-TET2 | 5 (8.9) | ST19 (1; CC16); ST21 (1; CC16); ST76 (1; CC1688); ST116 (1; CC16); ST1288 (1; CC863) |

| GEN-CIP-TET2 | 1 (1.8) | ST330 (1; CC16); |

| GEN-CIP-ERY-TET2 | 4 (7.1) | ST16 (2; CC16); ST82 (1; CC16); ST1768 (1; CC16) |

| GEN-CHL-ERY-TET 2 | 4 (7.1) | ST4 (1; CC16); ST35 (2; CC57); ST1291 (1; Singleton) |

| GEN-CIP- CHL-ERY-TET2 | 1 (1.8) | ST480 (1; CC16) |

| GEN-CIP-CHL-LZD-ERY-TET2 | 2 (3.6) | ST116 (2; CC16) |

| Total NWT isolates | 46 (82.1) | |

| Total MDR isolates | 19 (33.9) |

| ST | CC (DVL)a |

Nº vulture isolates | Nº isolates of E. faecalis in the MLST database | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDR | non-MDR | TOTAL | Animalsb | Human | Foods | Environment | Unknown | TOTAL | ||

| 4 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 14 | ||

| 7 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 9 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 2 | 24 | ||||

| 16 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 68 | 1 | 11 | 80 | ||

| 19 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 21 | ||

| 21 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 41 | 23 | 22 | 4 | 90 | ||

| 35 | 57 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 40 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 42 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 74 | |

| 59 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 11 | |||

| 76 | 1688 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||

| 82 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 1 | 25 | 2 | 41 | |

| 116 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 | |

| 200 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 256 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 13 | ||

| 268 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 287 | 287 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| 300 | 863 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| 330 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |||

| 441 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 480 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 16 | |||

| 631 | 631 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 11 | ||||

| 648 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| 699 | 1567 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 706 | 376 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 860 | 860 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1287 | 1861 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 1288 | 863 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| 1291 | singleton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1600 | 860 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1768 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1875 | 863 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Antimicrobial | Nº Isolates | ST (Nº isolates) |

Chromosome | MGEs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QRDRs (Nº isolates) |

ARGs (Nº isolates) |

REP (Nº isolates/ARG) |

Tn (Nº isolates/ARG) | ||||

| Included in the commercial panel | HLR-Gn | 13 | ST4 (1); ST16 (4); ST82 (1); ST35 (2); ST116 (2); ST330 (1); ST480 (1); ST1768 (1) | aac(6’)-aph(2’’) (12) | |||

| CIP | 8 | ST16 (2); ST82 (1); ST116 (2); ST330 (1); ST480 (1); ST1768 (1) | gyrA_E87G/parC_S80I (4) gyrA_E87G/parC_S80I (3) |

||||

| CIP (WT) | 2 | ST35 (2) | parC_S80I (2) | ||||

| CHL | 14 | ST480 (1); ST116 (3); ST4 (1); ST16 (2); ST1291 (1); ST35 (2); ST1288 (1); ST76 (1); ST21 (1); ST19 (1) |

cat(pC221) (1) cat(pC223) (2) |

rep7a (3/cat(pC221)) repUS43 (3/cat(pC223)) rpUS40 (2/fexA) |

|||

| LZD | 2 | ST116 (2) | rpUS40 (2/optrA) | ||||

| TET | 19 | ST4 (1); ST16 (4); ST19 (1); ST21 (1); ST35 (2); ST76 (1); ST82 (1); ST116 (2); ST330 (1); ST480 (1); ST1288 (1); ST1291(1); ST1768 (1) |

tetM (2) tetL (4) |

repUS43 (10/tetM) repUS43 (7/tetM&tetL) rep22 (2/tetL) |

Tn6009 (10/ tetM) Tn6009 (2/tetM&tetL) cn_43171_ISS1N (1/tetM&teL) |

||

| ERY | 19 | ST4 (1); ST16 (4); ST19 (1); ST21 (1); ST35 (2); ST76 (1); ST82 (1); ST116 (2); ST330 (1); ST480 (1); ST1288 (1); ST1291(1); ST1768 (1) | ermB (16) | rep7a (1/ ermB) | cn_43171_ISS1N (1/ermB) | ||

| No included in the commercial panel | STR | - | ant(6)-Ia (10) |

rep7a (1/ant(6)-Ia) rep7a (4/str) |

|||

| KAN | - | aph(3’)-III (12) | rep7a (1/ aph(3’)-III) | ||||

| TRM | - |

dfrD (1) dfrG (16) |

|||||

| LIN | - |

lsaA (19) lsaE (9) lnuA(1) lnuB (10) lnuG (5) |

Tn6260 (5/lnuG) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).