Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Food contact surfaces (FC): cutting equipment (knives, saws) and hair removal equipment (brushes or whips)

- Non-food contact surfaces (NFC): walls near the stunning and killing area, walls and drain surface of the pre-chilling area

- Scalding water (SW): approximately 100 mL of scalding water, collected using a sterile sampler (Bibby Scientific Limited, Stone, UK).

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

2.3. Whole Genome Sequencing

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Farms

3.2. Microbiological Analysis

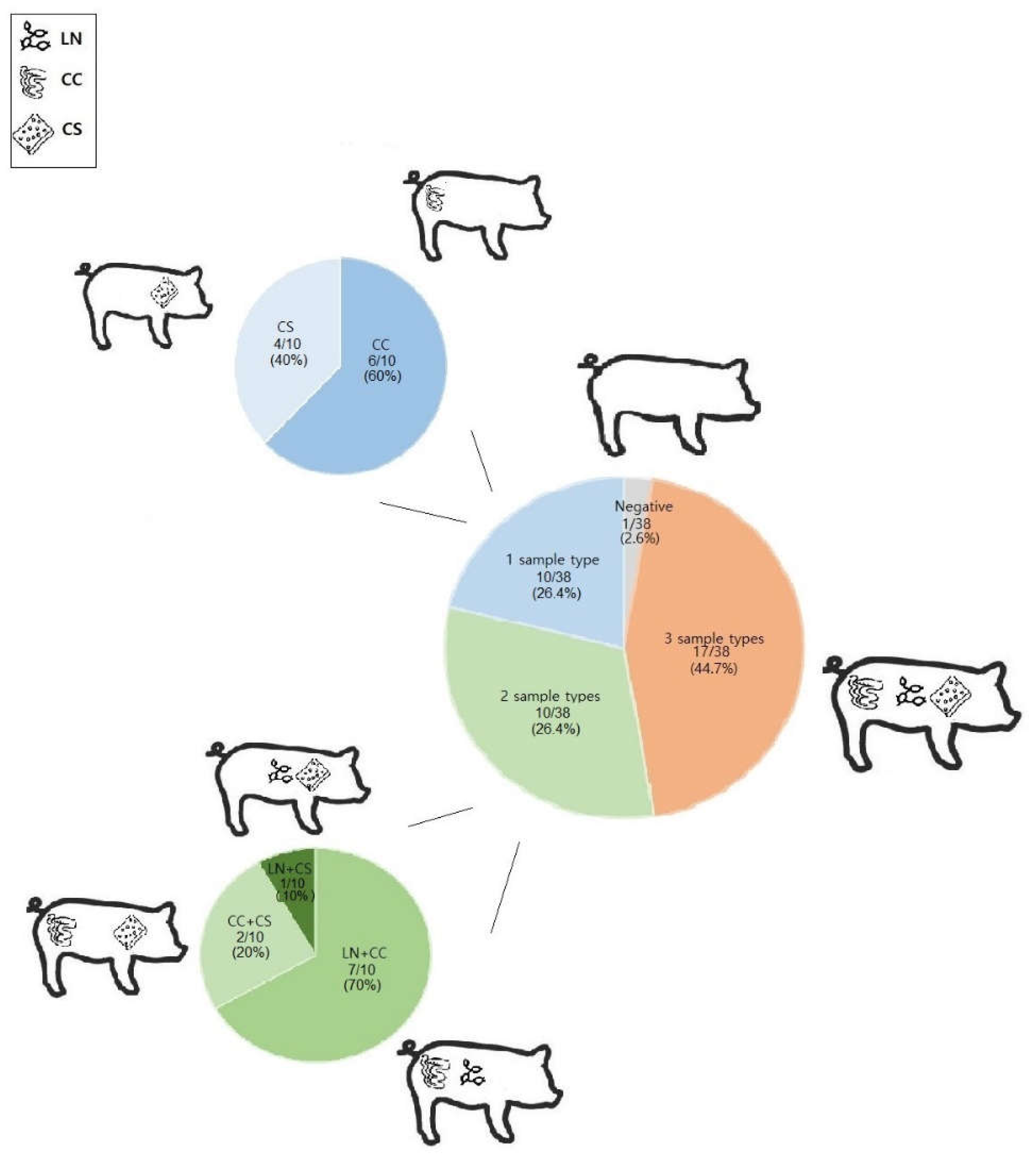

3.3. E. coli Characterization

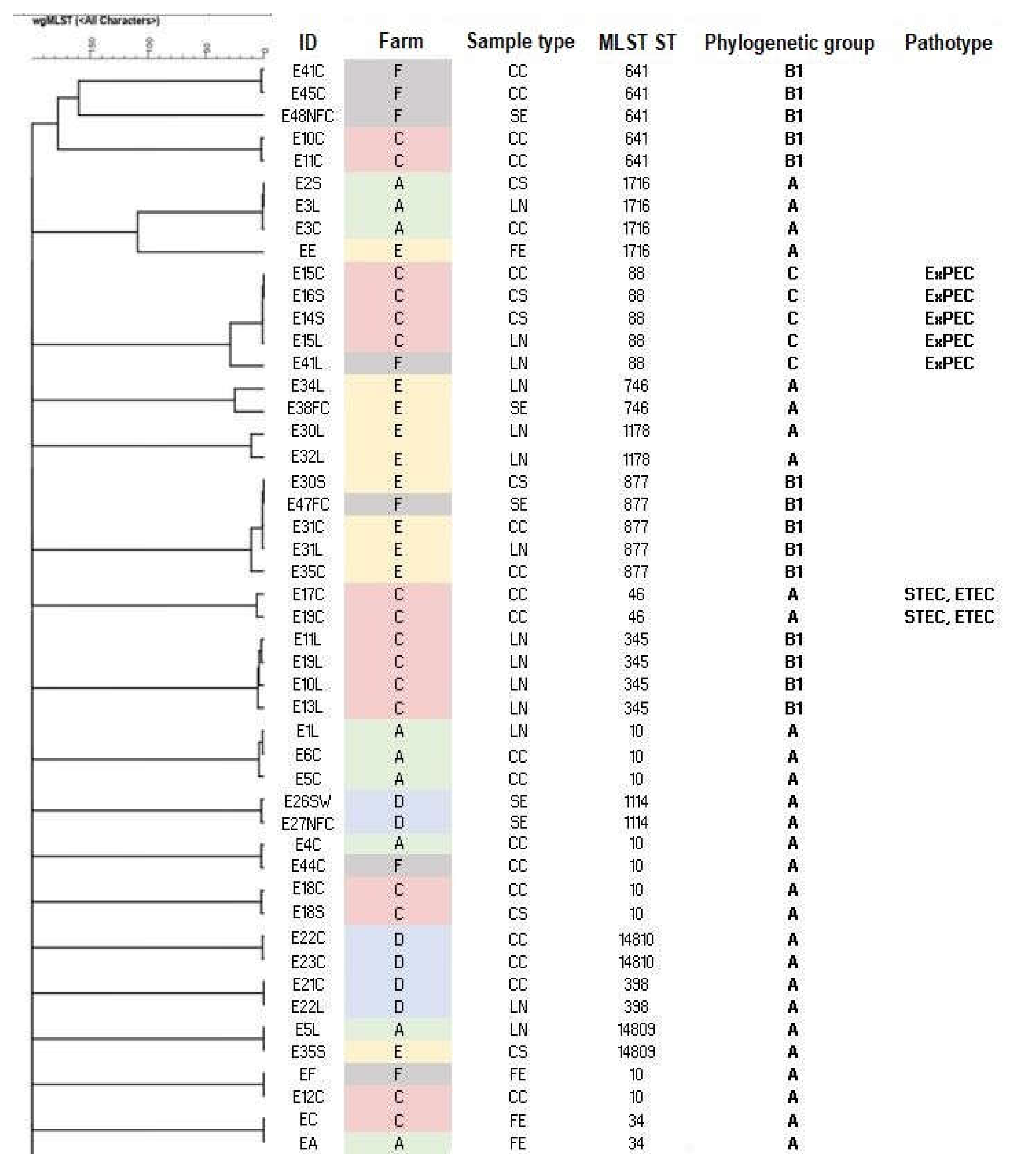

3.4. Cluster Analysis

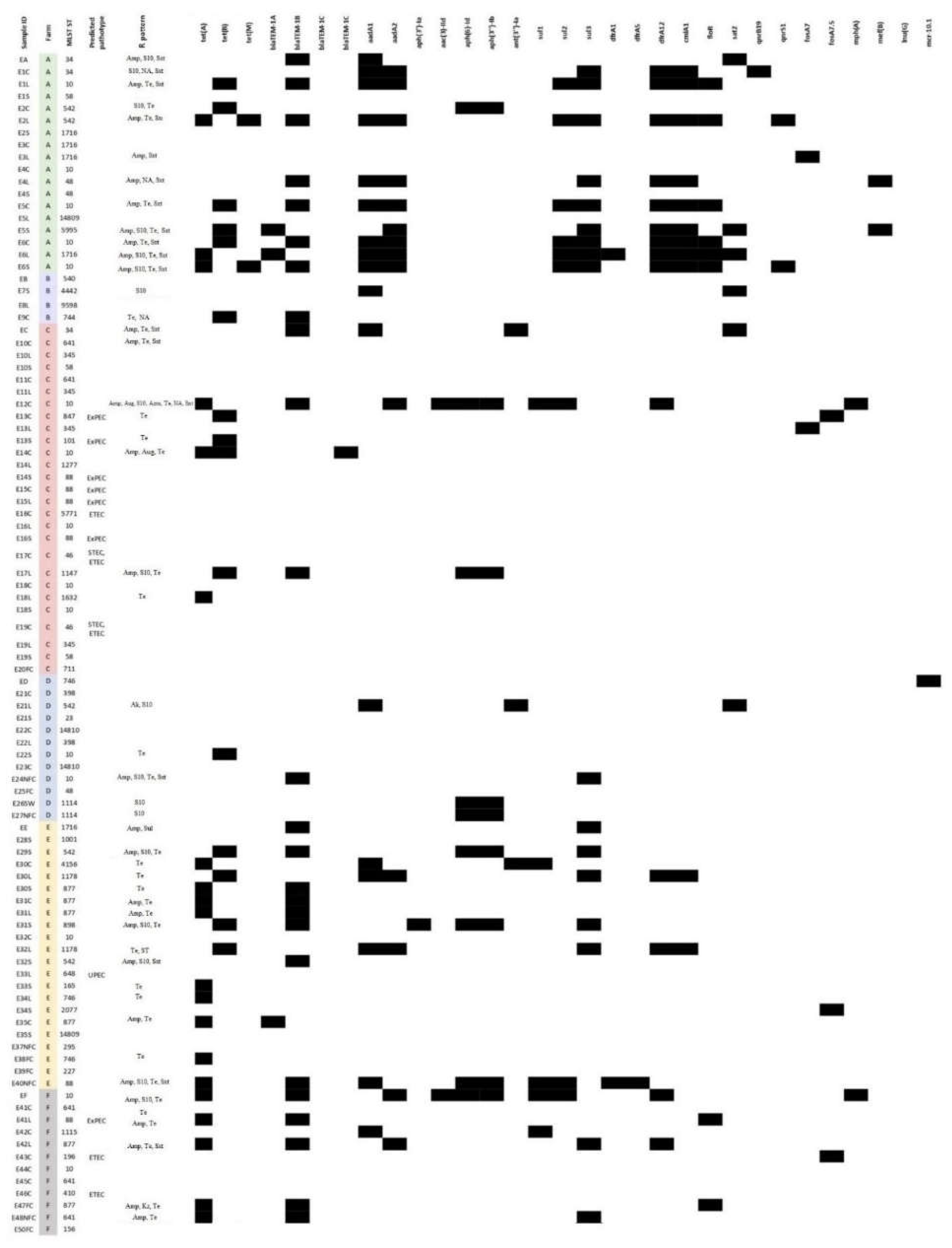

3.5. AMR Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaper, J.B.; Nataro, J.P.; Mobley, H.L. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.M. The ecology of Escherichia coli. In Escherichia coli: Pathotypes and Principles of Pathogenesis, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 3–20. ISBN 9780123970480. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, D.; Greune, L.; Heusipp, G.; Karch, H.; Fruth, A.; Tschäpe, H.; Schmidt, M.A. Identification of unconventional intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates expressing intermediate virulence factor profiles by using a novel single-step multiplex PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3380–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, J.M.; Nadeau, E.; Gyles, C.L. Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2005, 6, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, M.; Fratamico, P.M.; Manning, S.D.; Funk, J.A. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in swine: the public health perspective. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EMP-IAU-2017.12.

- Warmate, D.; Onarinde, B.A. Food safety incidents in the red meat industry: A review of foodborne disease outbreaks linked to the consumption of red meat and its products, 1991 to 2021. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 398, 110240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Lizarazo, C.M.; Sierra-Cadavid, A. Prevalence of Escherichia coli generic and pathogenic in pork meat: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, T.L.; Blom, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Poulsen, R.L.; Espersen, F. Transient intestinal carriage after ingestion of antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus faecium from chicken and pork. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards. Scientific Opinion on the public health risks of bacterial isolates producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases and/or AmpC β-lactamases in food and food-producing animals. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17604; Microbiology of the Food Chain. Carcass sampling for microbiological analysis. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Siddi, G.; Piras, F.; Gymoese, P.; Torpdahl, M.; Meloni, M.P.; Cuccu, M.; Migoni, M.; Cabras, D.; Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M.; De Santis, E.P.L.; et al. Pathogenic profile and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli, Escherichia marmotae, and Escherichia ruysiae detected from hunted wild boars in Sardinia (Italy). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 421, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enterobase. Available online: https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- SerotypeFinder database. Available online: https://journals.asm.org/doi/pdf/10.1128/jcm.00008-15 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- KMA mapping tool. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2336-6 (accessed on 16 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- AMRFinder tool. Available online: https://github.com/ncbi/amr (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- ResFinder tool. Available online: https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/ (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- PlasmidFinder tool. Available online: https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/ (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- VirulenceFinder tool. 2024. Available online: https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/VirulenceFinder/ (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- EUCAST. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters 2024; Version 14.0. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Schwarz, S.; Silley, P.; Simjee, S.; Woodford, N.; Van Duijkeren, E.; Johnson, A.P.; Gaastra, W. Editorial: Assessing the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria obtained from animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarowska, J.; Futoma-Koloch, B.; Jama-Kmiecik, A.; Frej-Madrzak, M.; Ksiazczyk, M.; Bugla-Ploskonska, G.; Choroszy-Kro, I. Virulence factors, prevalence and potential transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from different sources: recent reports. Gut Pathog. 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlos, C.; Pires, M.M.; Stoppe, N.C.; Hachic, E.M.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Gomes, T.A.T.; Amaral, L.A.; Ottoboni, L.M.M. Escherichia coli phylogenetic group determination and its application in the identification of the major animal source of fecal contamination. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amass, S.F. Biosecurity: stopping the bugs from getting in. Pig J. 2005, 55, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, K.D.; Wingstrand, A.; Dahl, J.; Mogelmose, V.; Lo Fo Wong, D.M. Differences and similarities among experts’ opinions on Salmonella enterica dynamics in swine pre-harvest. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 53, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, M.; Bierbaum, G.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Schmithausen, R.M.; Sib, E.; Schmoger, S.; Käsbohrer, A.; Hammerl, J.A. Clinically relevant Escherichia coli isolates from process waters and wastewater of poultry and pig slaughterhouses in Germany. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.M.; Silva, R.M.; Valiatti, T.B.; Santos, F.F.; Santos-Neto, J.F.; Cayô, R.; Streling, A.P.; Nodari, C.S.; Gales, A.C.; Nishiyama, M.Y., Jr.; et al. Virulence potential of a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strain belonging to the emerging clonal group ST101-B1 isolated from bloodstream infection. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstokstraeten, R.; Crombé, F.; Piérard, D.; Castillo Moral, A.; Wybo, I.; De Geyter, D.; Janssen, T.; Caljon, B.; Demuyser, T. Molecular characterization of extraintestinal and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli blood isolates. Virulence 2022, 13, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewbank, A.C.; Fuentes-Castillo, D.; Sacristán, C.; Esposito, F.; Fuga, B.; Cardoso, B.; Godoy, S.N.; Zamana, R.R.; Gattamorta, M.A.; Catão-Dias, J.L.; et al. World Health Organization Critical Priority Escherichia coli clone ST648 in magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens) of an uninhabited insular environment. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, B.; Gulyás, D.; Szabó, D. Emergence and dissemination of extraintestinal pathogenic high-risk international clones of Escherichia coli. Life 2022, 12, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manges, A.R.; Smith, S.P.; Lau, B.J.; Nuval, C.J.; Eisenberg, J.N.; Dietrich, P.S.; Riley, L.W. Retail meat consumption and the acquisition of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections: A case-control study. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2007, 4, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, L.; Spangholm, D.J.; Pedersen, K.; Jensen, L.B.; Emborg, H.; Agersø, Y.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Hammerum, A.M.; Frimodt-Møller, N. Broiler chickens, broiler chicken meat, pigs and pork as sources of ExPEC related virulence genes and resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from community-dwelling humans and UTI patients. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manges, A.R.; Johnson, J.R. Food-borne origins of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stromberg, Z.R.; Johnson, J.R.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Kilbourne, J.; Goor, A.V.; Mellata, M. Evaluation of Escherichia coli isolates from healthy chickens to determine their potential risk to poultry and human health. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0180599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, L.; Liu, C.M.; Price, L.B. Foodborne urinary tract infections: A new paradigm for antimicrobial-resistant foodborne illness. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba, X.; Guo, Y.; Moran, R.A.; Doughty, E.L.; Liu, B.; Yao, L.; Li, J.; He, N.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Global emergence of a hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli ST410 clone. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydendahl, K. Prevalence of serogroups and virulence genes in Escherichia coli associated with postweaning diarrhoea and edema disease in pigs and a comparison of diagnostic approaches. Vet. Microbiol. 2002, 85, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, S.M.; Danzeisen, J.L.; Isaacson, R.E.; Seemann, T.; Achtman, M.; Johnson, T.J. Genome sequences and phylogenetic analysis of K88- and F18-positive porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 194, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheutz, F.; Teel, L.D.; Beutin, L.; Piérard, D.; Buvens, G.; Karch, H.; Mellmann, A.; Caprioli, A.; Tozzoli, R.; Morabito, S.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2951–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, A.; Bielaszewska, M.; Mellmann, A.; Dierksen, N.; Schierack, P.; Wieler, L.H.; Schmidt, M.A.; Karch, H. Shiga toxin 2e-producing Escherichia coli isolates from humans and pigs differ in their virulence profiles and interactions with intestinal epithelial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8855–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel; Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the pathogenicity assessment of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and the public health risk posed by contamination of food with STEC. EFSA J. 2020, 18, 5967. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HSE-PED-AIP-2014.2 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ghidini, S.; Luca, S.D.; Rodríguez-López, P.; Simon, A.C.; Liuzzo, G.; Poli, L.; Ianieri, A.; Zanardi, E. Microbial contamination, antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation of bacteria isolated from a high-throughput pig abattoir. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, A.; Card, R.; Duggett, N.; Smith, R.; Davies, R.; Cawthraw, S.; Anjum, M.; Rambaldi, M.; Ostanello, F.; Martelli, F. Reduction in antimicrobial resistance prevalence in Escherichia coli from a pig farm following withdrawal of group antimicrobial treatment. Vet. Microb. 2021, 258, 109125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, J.; Muwonge, A.; Hutchings, M.R.; Mainda, G.; Bronsvoort, B.M.; Gally, D.L.; Corbishley, A. Resistance to change: AMR gene dynamics on a commercial pig farm with high antimicrobial usage. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.P.; May, H.E.; AbuOun, M.; Stubberfield, E.; Gilson, D.; Chau, K.K.; Crook, D.W.; Shaw, L.P.; Read, D.S.; Stoesser, N.; et al. A longitudinal study reveals persistence of antimicrobial resistance on livestock farms is not due to antimicrobial usage alone. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1070340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L. Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durão, P.; Balbontín, R.; Gordo, I. Evolutionary mechanisms shaping the maintenance of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Amado, A.; Kassen, R.; Bank, C.; Wong, A. Unpredictability of the fitness effects of antimicrobial resistance mutations across environments in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.L.; Baquero, F. Mutation frequencies and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine, 6th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 14 October 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515528 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.-X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z. Whole genome sequence of an MCR-1-carrying, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli ST746 isolate recovered from a community-acquired urinary tract infection. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 13, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, Y.; Han, D.; Hur, H. Emergence of high-level carbapenem and extensively drug-resistant Escherichia coli ST746 producing NDM-5 in influent of wastewater treatment plant, Seoul, South Korea. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 645411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; Si, H. Antimicrobial resistance and transconjugants characteristics of sul3 positive Escherichia coli isolated from animals in Nanning, Guangxi Province. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarneri, F.; Bertasio, C.; Romeo, C.; Formenti, N.; Scali, F.; Parisio, G.; Canziani, S.; Boifava, C.; Guadagno, F.; Boniotti, M.B.; et al. First detection of mcr-9 in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli of animal origin in Italy is not related to colistin usage on a pig farm. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordoñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the maximum levels of cross-contamination for 24 antimicrobial active substances in non-target feed. Part 12: Tetracyclines: tetracycline, chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, and doxycycline. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, 6864. [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordoñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the role played by the environment in the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through the food chain. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, 6651. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, P.; Bosco, C.; Bonilauri, P.; Luppi, A.; Fontana, M.C.; Fiorentini, L.; Rugna, G. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors Assessment in Escherichia coli Isolated from Swine in Italy from 2017 to 2021. Pathogens 2022, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) & ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2021–2022. EFSA Journal 2024, 22, e8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.B.; Marshall, B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: Causes, challenges and responses. Nature Medicine 2004, 10(12 Suppl), S122–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, E.; Veres, A.; Michel, J.; Chait, R.; Hartl, D.L.; Kishony, R. Evolutionary paths to antibiotic resistance under dynamically sustained drug selection. Nature Genetics 2011, 44, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.A.; Anantham, S.; Holt, K.E.; Hall, R.M. Prediction of antibiotic resistance from antibiotic resistance genes detected in antibiotic-resistant commensal Escherichia coli using PCR or WGS. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2017, 72, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Farm | Herd size (n) | Fattening pigs (n) | Fattening period (days) | Floor of the fattening pen | Cleaning of the fattening pen | Feed | Water | Pest control | Antibiotic compounds used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 300 | 220 | Approx. 150 | S | Daily, AFAE | CP | Well | Rodents | Aug, Sxt |

| B | 180 | 130 | Approx. 180 | NS, external paddock | Daily | CP + whey | Mains | Rodents | - |

| C | 150 | 80 | Approx. 210 | S, external paddock | Twice a day | CP | Mains + well | Rodents | Aug, Ox |

| D | 150 | 80 | Approx. 270 | NS | AFAE | CP + whey | Well | Rodents | Aug |

| E | 5000 | 500 | Approx. 120 | NS | Daily, AFAE | CP | Well | Rodents | - |

| F | 1400 | 700 | Approx. 120 | S | Daily, AFAE | CP | Mains | Rodents | - |

| Farm | Slaughterhouse | Number of tested pigs | Number of positive lymph nodes samples (pathogenic isolates) | Number of positive colon content samples (pathogenic isolates) | Number of positive carcass surface samples (pathogenic isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | S1 | 6 | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) |

| B | S1 | 3 | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 |

| C | S2 | 10 | 9 (1 ExPEC) | 10 (2 ExPEC, 2 STEC-ETEC, 1 ETEC) | 6 (3 ExPEC) |

| D | S3 | 3 | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) |

| E | S4 | 10 | 4 (1 UPEC) | 5 (0) | 9 (0) |

| F | S5 | 6 | 2 (1 ExPEC) | 6 (2 ETEC) | 0 |

| ID | Sample type | Farm | Slaughterhouse | MLST ST | Serotype | Phylogenetic group | Predicted pathotype |

Virulence genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | E | A | S1 | 34 | O101:H37 | A | - | acrF, astA, cea, emrE, fdeC, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E1C | CC | A | S1 | 34 | O9:H10 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E1L | LN | A | S1 | 10 | O?:H9 | A | - | acrF, cea, fdeC, hra, iss, mdtM, terC |

| E1S | CS | A | S1 | 58 | O8:H30 | B1 | - | capU, cba, cia, cma, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, hlyF, iroBCDEN, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT |

| E2C | CC | A | S1 | 542 | O?:H45 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, mdtM, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRs, terC |

| E2L | LN | A | S1 | 542 | O?:H45 | A | - | acrF, mdtM, pcoBCDER, silAF, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E2S | CS | A | S1 | 1716 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, iss, mdtM, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E3C | CC | A | S1 | 1716 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, iss, mdtM, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E3L | LN | A | S1 | 1716 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, iss, mdtM, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E4C | CC | A | S1 | 10 | O111:H27 | A | - | acrF, astA, iss, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E4L | LN | A | S1 | 48 | O99:H9 | A | - | espX1, fdeC, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E4S | CS | A | S1 | 48 | O26:H12 | A | - | acrF, astA, emrE, fdeC, fyuA, hra, irp2, mdtM, ompT, terC, traT, ybtP, ybtQ |

| E5C | CC | A | S1 | 10 | O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, hra, iss, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E5L | LN | A | S1 | 14809 | O4:H45 | A | - | acrF, mdtM, terC, traT, tsh |

| E5S | CS | A | S1 | 5995 | O?:H27 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, mdtM, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E6C | CC | A | S1 | 10 | O89/O162/O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, cea, fdeC, hra, iss, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E6L | LN | A | S1 | 1716 | O126:H11 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, hra, iss, mdtM, pcoE, terC, ymgB |

| E6S | CS | A | S1 | 10 | O69:H32 | A | - | acrF, cba, cea, celb, cia, cma, fdeC, iss, katP, mdtM, ompT, pcoAER, silBCFRS, terC, ymgB |

| EB | A | B | S1 | 540 | O?:H30 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fyuA, hra, irp2, mdtM, terC, ybtP, ybtQ, ymgB |

| E7S | CS | B | S1 | 4442 | O54:H16 | B1 | - | acrF, cba, celb, cma, cvaC, ehxA, fdeC, iha, ireA, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, terBCDWZ, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E8L | LN | B | S1 | 9598 | O168:H12 | A | - | acrF, astA, emrE, mdtM, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E9C | CC | B | S1 | 744 | O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, astA, fdeC, hra, mdtM, merCPRT, silABCEFPRS, terC, traT, ymgB |

| EC | A | C | S2 | 34 | O?:H37 | A | - | acrF, astA, cea, emrE, fdeC, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E10C | CC | C | S2 | 641 | O121:H10 | B1 | - | fedF, lpfA, sepA, terC, traT |

| E10L | LN | C | S2 | 345 | O8:H45 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, hlyA-alpha, iss, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, sepA, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E10S | CA | C | S2 | 58 | O25:H21 | B1 | - | acrF, afaA, afaB, astA, emrE, f17AG, fdeC, hra, iss, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, papC, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E11C | CC | C | S2 | 641 | O121:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, astA, f17AG, fdeC, fedF, lpfA, mdtM, sepA, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E11L | LN | C | S2 | 345 | O8:H45 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, hlyA-alpha, iss, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, sepA, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E12C | CC | C | S2 | 10 | O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, cea, emrE, espX1, fdeC, fyuA, irp2, iss, iucC, iutA, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E13C | CC | C | S2 | 847 | O?:H2 | B1 | ExPEC | acrF, cia, cma, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, hlyF, hra, iroN, iss, iucABCCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papA_F13, papC, sitA, terC, traT, ybtP, ybtQ, ymgB |

| E13L | LN | C | S2 | 345 | O8:H45 | B1 | - | acrF, cvaC, emrE, fdeC, iroBCDEN, iss, iucABCD, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papACEG-IIIH, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E13S | CS | C | S2 | 101 | O11:H10 | B1 | ExPEC | acrF, cba, cia, cma, cnf1, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, hra, iroN, irp2, iss, iucC, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papA_F1651A, papC, sitA, terC, tsh, tsh, ymgB |

| E14C | CC | C | S2 | 10 | O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, aslA, csgA, cvaC, emrE, fdeC, fimH, gad, hlyA-alpha, hlyE, iroBCDEN, iucABCD, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, papCEFG-IIIH, terC, traJ, tsh, ybtPQ, yeh, ymgB |

| E14L | LN | C | S2 | 1277 | O?:H28 | A | - | aslA, csgA, espY, fimH, hlyE, terC, yeh |

| E14S | CS | C | S2 | 88 | O8:H9 | C | ExPEC | acrF, astA, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroB, iroCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtP, ybtQ, ymgB |

| E15C | CC | C | S2 | 88 | O8:H9 | C | ExPEC | acrF, astA, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E15L | LN | C | S2 | 88 | O8:H9 | C | ExPEC | acrF, astA, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, gad, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E16C | CC | C | S2 | 5771 | O7:H24 | D | ETEC | anr, aslA, astA, chuA, cia, csgA, eilA, eltlAB, espY, estb-STb1, fdeC, fimH, hha, hlyE, kpsEMII, lpfA, neuC, sitA, terC, traT, yeh |

| E16L | LN | C | S2 | 10 | O84:H21 | A | - | acrF, cea, emrE, gad, mdtM, ompT, terC, ymgB |

| E16S | CS | C | S2 | 88 | O8:H9 | C | ExPEC | acrF, astA, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E17C | CC | C | S2 | 46 | O9:H4 | A | STEC, ETEC | acrF, cba, cma, iss, mdtM, ompT, sepA, sta1, stb, stx2Ae, stx2e, terC,traT, ymgB |

| E17L | LN | C | S2 | 1147 | O128:H2 | B1 | - | fdeC, gad, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E18C | CC | C | S2 | 10 | O?:H40? | A | - | acrF, cea, hra, mdtM, terC |

| E18L | LN | C | S2 | 1632 | O182:H38 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, hra, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E18S | CS | C | S2 | 10 | O?:H40? | A | - | acrF, cea, hra, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E19C | CC | C | S2 | 46 | O9:H4 | A | STEC, ETEC | acrF, cba, cma, iss, mdtM, ompT, sepA,s ta1,stb, stx2Ae, stx2e, terC,traT, ymgB |

| E19L | LN | C | S2 | 345 | O8:H45 | B1 | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, iss, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E19S | CS | C | S2 | 58 | O165:H25 | B1 | - | acrF, cea, ehxA, fdeC, focCG, iroBCDEN, iss, lpfA, mchBCF, mcmA, mdtM, ompT, sfaDEF, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E20FC | FC | C | S2 | 711 | O120:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| ED | E | D | S3 | 746 | O21:H10 | A | - | acrF, arsADR, astA, fdeC, fyuA, irp2, iss, kpsEM_K11, mdtM, sitA, terC, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E21C | CC | D | S3 | 398 | O8:H20 | A | - | acrF, astA, cma, cvaC, emrE, hra, iucABCD, iutA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E21L | LN | D | S3 | 542 | O179:O8:H45 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, hra, terC, ymgB |

| E21S | CS | D | S3 | 23 | O9:H32 | C | - | acrF, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E22C | CC | D | S3 | 14810 | O?:H45 | A | - | cia, cma, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, hlyF, iroBCDEN, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E22L | LN | D | S3 | 398 | O8:H20 | A | - | acrF, astA, cma, cvaC, emrE, hra, iucABCD, iutA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ymgB |

| E22S | CS | D | S3 | 10 | O160:H4 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, fyuA, hra, irp2, mdtM, terC, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E23C | CC | D | S3 | 14810 | O?:H45 | A | - | cia, cma, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, hlyF, iroBCDEN, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E24NFC | SE | D | S3 | 10 | O13:H11 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, fyuA, irp2, mdtM, ompT, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E25FC | SE | D | S3 | 48 | O8:H18 | A | - | acrF, astA, fdeC, hra, mdtM, terC |

| E26SW | SE | D | S3 | 1114 | O117:H5 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, mdtM ,terC |

| E27NFC | SE | D | S3 | 1114 | O117:H5 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, gad, mdtM, terC |

| EE | FE | E | S4 | 1716 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, emrE, fdeC, iss, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E28S | CS | E | S4 | 1001 | O40:O8:H2 | B1 | - | acrF, cea, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E29S | CS | E | S4 | 542 | O184:H30 | A | - | acrF, astA, fdeC, mdtM, pcoABCDERS, silABCEDPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E30C | CC | E | S4 | 4156 | O113:H32 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, mdtM, merCPRT, terC, ymgB |

| E30L | LN | E | S4 | 1178 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, hra, mdtM, merCPRT, pcoABCDERS, silABEFPRS, terC, traT, tsh |

| E30S | CS | E | S4 | 877 | O?:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E31C | CC | E | S4 | 877 | O?:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPR, terC, ymgB |

| E31L | LN | E | S4 | 877 | O?:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E31S | CS | E | S4 | 898 | O?:H48 | A | - | acrF, emrE, espX1, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E32C | CC | E | S4 | 10 | O71:H27 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, fyuA, irp2, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, silS, terC, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E32L | LN | E | S4 | 1178 | O130:H26 | A | - | acrF, hra, mdtM, merCPRT, pcoABCDERS, silABEFPRS, terC, traT, tsh |

| E32S | CS | E | S4 | 542 | O8:H45 | A | - | acrF, fdeC, gad, hra, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E33L | LN | E | S4 | 648 | O2:H42 | F | UPEC | acrF, air, chuA, cia, eilA, emrDE, fdeC, iss, kpsEMII, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, terC, traT, yfcV, ymgB |

| E33S | CS | E | S4 | 165 | O180:H51 | A | - | aaiC, acrF, astA, cba, cea, emrE, katP, mcbA, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E34L | LN | E | S4 | 746 | O?:H19 | A | - | acrF, astA, emrE, fdeC, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E34S | CS | E | S4 | 2077 | O?:H8 | B1 | - | acrF, cea, emrE, fdeC, gad, iss, lpfA, mdtM, pcoABCDERS, pcoS, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E35C | CC | E | S4 | 877 | O?:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E35S | CS | E | S4 | 14809 | O4:H45 | A | - | acrF, mdtM, terC, traT, tsh |

| E37NFC | SE | E | S4 | 295 | O?:H16 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E38FC | SE | E | S4 | 746 | O?:H19 | A | - | acrF, astA, emrE, fdeC, mdtM, terC, traT |

| E39FC | SE | E | S4 | 227 | O162:H10 | A | - | acrF, capU, emrE, etpD, fdeC, katP, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E40NFC | SE | E | S4 | 88 | O?:H12 | C | - | acrF, cia, cib, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, merPRT, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| EF | FE | F | S5 | 10 | O101:H9 | A | - | acrF, cea, fdeC, fyuA, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E41C | CC | F | S5 | 641 | O121:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E41L | LN | F | S5 | 88 | O8:H9 | C | ExPEC | acrF, cea, cib, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchF, mdtM, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

| E42C | CC | F | S5 | 1115 | O102:H40 | A | - | acrF, cea, clpK, fdeC, hdeD-GI, hsp20, kefB-GI, mdtM, merCPRT, psi-GI, shsP, terC, trxLHR, yfdX1X2, ymgB |

| E42L | LN | F | S5 | 877 | O7:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, astA, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, terC, ymgB |

| E43C | CC | F | S5 | 196 | O?:H7 | B1 | ETEC | acrF, astA, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, stb, terC, ymgB |

| E44C | CC | F | S5 | 10 | O111:H27 | A | - | acrF, astA, iss, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E45C | CC | F | S5 | 641 | O121:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, terC, ymgB |

| E46C | CC | F | S5 | 410 | O15:H12 | C | ETEC | acrF, astA, emrE, fdeC, iss, lpfA, mdtM, stb, terC, ymgB |

| E47FC | SE | F | S5 | 877 | O?:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, lpfA, mdtM, ompT, pcoABCDERS, silABCEFPRS, terC, ymgB |

| E48NFC | SE | F | S5 | 641 | O121:H10 | B1 | - | acrF, fdeC, fedF, lpfA, mdtM, terC, traT, ymgB |

| E50FC | SE | F | S5 | 156 | O?:H28 | B1 | - | acrF, astA, cea, cvaC, emrE, etsC, fdeC, fyuA, hlyF, iha, iroBCDEN, irp2, iss, iucABCD, iutA, lpfA, mchBCF, mdtM, ompT, sitA, terC, traT, tsh, ybtPQ, ymgB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).