Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Collection and Transportation of Samples

Sample Processing and Identification

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Biofilm Production

DNA Extraction from Isolates

Detection of Operon Genes ica (icaA and icaD)

Statistics

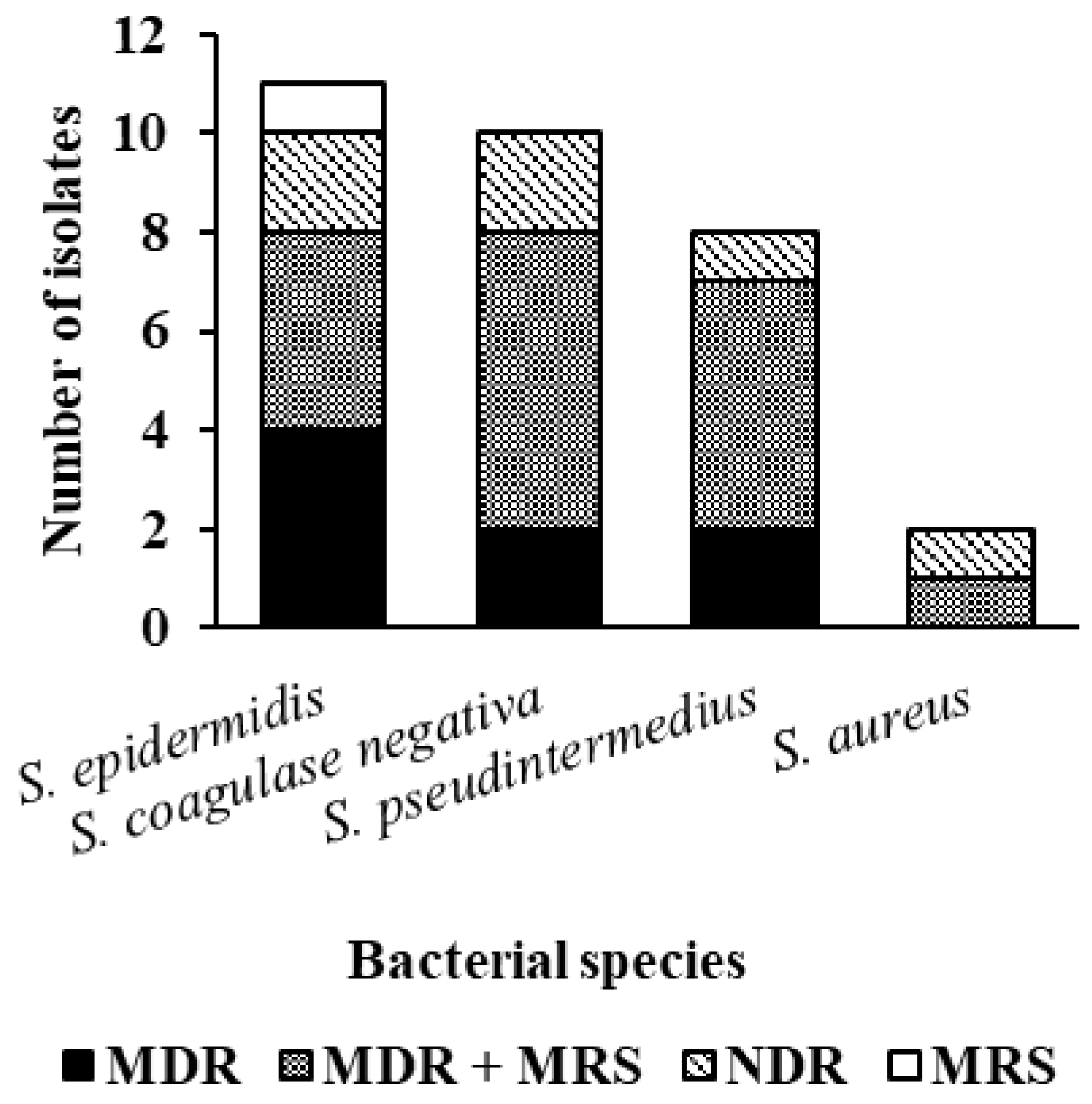

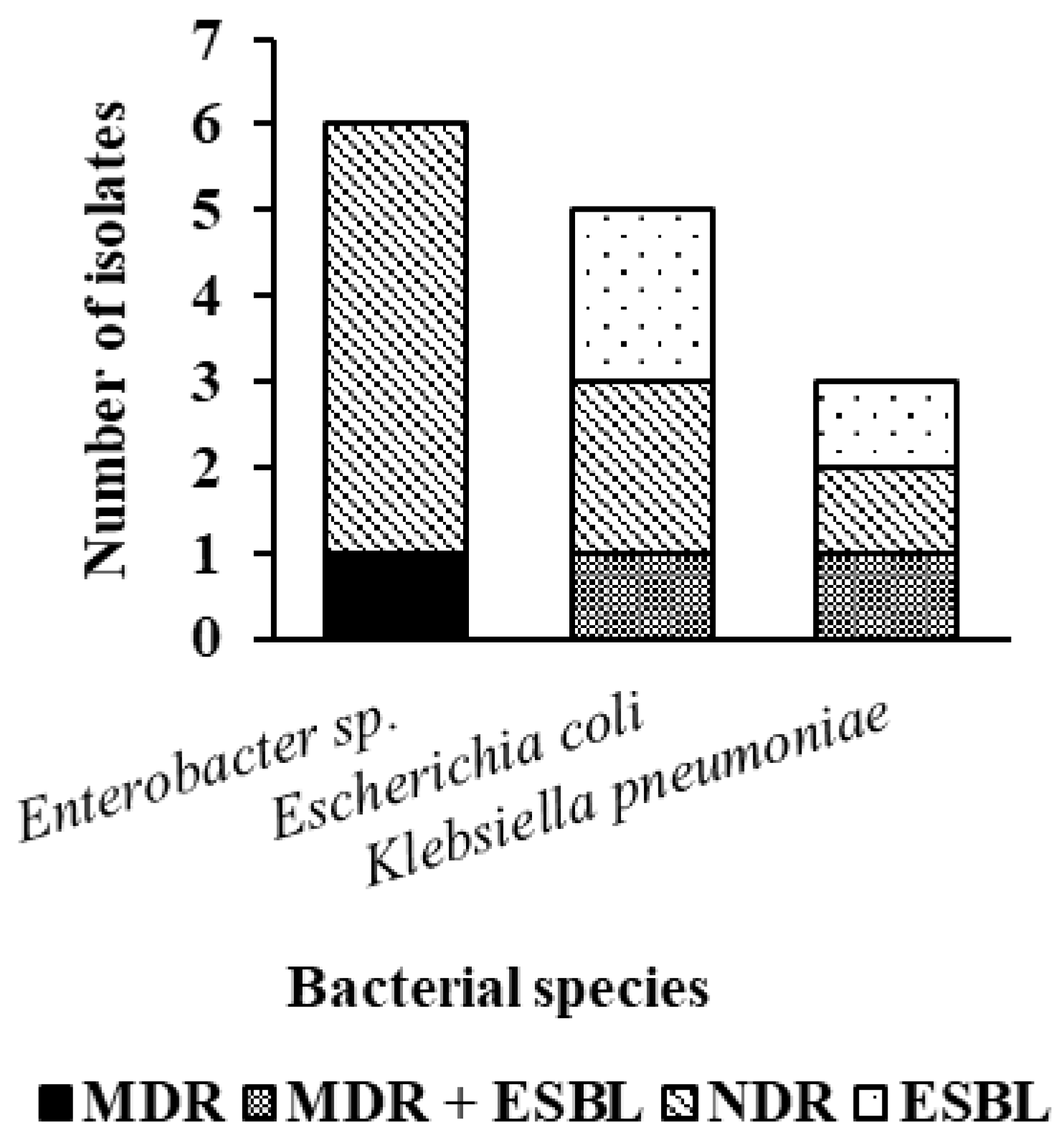

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MRSP | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius |

| MRS | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus sp., |

| ESBL | Extended spectrum β-lactamase |

| NDR | Does not present multidrug resistance |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

| PDR | Pandrug-resistant |

| HAIs | Healthcare-Associated Infections |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substance |

| PIA | Polysaccharide intercellular adhesin |

| ICA | ica operon |

| BHP | Homologous biofilm-associated protein |

| AAP | Accumulation-associated protein |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| BrCAST | Brazilian Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| dNTP | deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates |

References

- Brasil (1998). Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 2.616 de 12 de maio de 1998. Dispõe sobre as diretrizes e normas para a prevenção e o controle das infecções hospitalares. Brasília, DF.

- Hayashi CMT, Silva PS, Silva RM, Ribeiro T (2017). Prevenção e controle de infecções relacionadas a assistência à saúde: fatores intrínsecos ao paciente. HU revista., 43(3):277-283.

- Stull JW, Weese JS (2015). Hospital-Associated Infections in Small Animal Practice. The Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice, 45(2):217–233. [CrossRef]

- Verdial CSS (2020). Prevenção de Infecções Nasocomiais: Controle bacteriológico de superfícies hospitalares de unidade de isolamento e contenção biológica do hospital escolar da FMV-ULisboa. Dissertação de mestrado integrado em medicina veterinária—Universidade de Lisboa.

- Rowlinson MC, Lebourgeois P, Ward K, Song Y, Finegold SM, Bruckner DA (2006). Isolation of a strictly anaerobic strain of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Clin. Microbiol.,44:857–860. [CrossRef]

- Arnaouteli S, Bamford NC, Stanley-Wall NR, Kovács ÁT (2021). Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation and social interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 2021, 19(9):600–614. [CrossRef]

- Ciofu O, Tolker-Nielsen T (2019). Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents-how P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Frontiers in Microbiology., 10:913. [CrossRef]

- Chiba A, Seki M, Susuki Y, Kinjo Y, Mizunoe Y, Sugimoto S (2022). Staphylococcus aureus utilizes environmental RNA as a building material in specific polysaccharide-dependent biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes., 8(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Yin W, Wang Y, Liu L, He J (2019). Biofilms: the microbial “protective clothing” in extreme environments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences., 20(14): 3423. [CrossRef]

- Abebe GM (2020). The role of bacterial biofilm in antibiotic resistance and food contamination. Int. J. Microbiol.. doi: 2020:1705814. [CrossRef]

- Zhao A, Sun J, Liu Y (2023). Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front. Cell Infect Microbiol., 13:1137947. [CrossRef]

- François P, Schrenzel J, Götz F (2023). Biology and Regulation of Staphylococcal Biofilm. Int J Mol Sci., 9;24(6):5218. [CrossRef]

- Cataneli Pereira V, Pinheiro-Hubinger L, de Oliveira A, Moraes Riboli DF, Benini Martins K, Calixto Romero L, Ribeiro SCML (2020). Detection of the agr System and Resistance to Antimicrobials in Biofilm-Producing S. epidermidis. Molecules. 3;25(23):5715. [CrossRef]

- Ruhal R, Kataria R (2021). Biofilm patterns in gram-positive and gram-negative bactéria. Microbiological Research, 251:126829. [CrossRef]

- Stull JW, Bjorvik E, Bub J, Dvorak G, Petersen C, Troyer HL (2018). AAHA Infection Control, Prevention, and Biosecurity Guidelines. Journal of the Americam Animal Hospital Association., 54(6):297–326. [CrossRef]

- Gaschen F (2008). Nosocomial Infection: Prevention and Approach. Dublin (IE): World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress.

- Portner JA, Johnson JA (2010). Guidelines for reducing pathogens in veterinary hospitals: disinfectant selection, cleaning protocols, and hand hygiene. Compend Contin Educ Vet., 32(5):E1-11.

- Mann A (2018). Hospital-acquired infections in the veterinary establishment. Vet Nurs J., 33(9):257– 261. [CrossRef]

- Anvisa (2013). Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Microbiologia Clínica para o controle de infecção Relacionada à Assistência a Saúde. Módulo 6: Detecção e identificação de bactérias de importância médica. Brasília.

- Brazilian Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibily Testing, BRCast. (2023). Orientações do EUCast/BRCast para a detecção de mecanismos de resistência e resistências específicas de importância clínica e/ou epidemiológica. Versão 2.0. 2023.

- Magiorakos AP et al. (2012). Bactérias multirresistentes, extensivamente resistentes e pan droga resistentes a medicamentos: uma proposta internacional especializada para definições padrão provisórias para resistência adquirida. Clinical Microbiology and Infection., 18(3):268–281.

- Stepanovic S, Vukovic D, Hola V, Bonaventura GD, Djukic S, Cirkovic I, Ruzicka F (2007). Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by Staphylococci. APMIS. 115(8):891-899. [CrossRef]

- Olsvick O, Strockbine NA (1993). PCR detection of heat-stable, heat-labile, and Shiga-like toxin genes in Escherichia coli. In: Diagnostic Molecular Microbiology: Principles and Applications. American Society for Microbiology, 271–276.

- Proietti PC, Stefaneti V, Hyatt DR, Marenzoni ML, Capomaccio S, Coletti M, Bietta A, Franciosini MP, Passamonti F (2015). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of canine pyoderma isolates of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius for biofilm formation. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 77(8): 945-951. [CrossRef]

- Pereira MG (1999) Epidemiologia: Teoria e Prática. Guanabara Koogan, Rio de Janeiro.

- Mahl S, Rossi EM (2017). Suspectibilidade antimicrobiana de bactérias isoladas de colchões hospitalares. RBAC., 49(4): 371-375. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira FA, Stella AE (2019). Enterobactérias multirresistentes presentes em ambiente hospitalar veterinário. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira.

- Palácio PB, Aquino PEA, Silva ALA, Sousa KRF, Leandro LMG, Guedes TTAM, Macedo RO (2018). Perfil de resistência em bactérias isoladas de superfícies de um hospital público de Juazeiro do Norte-CE. Revista Saúde (Sta. Maria).,44(2). [CrossRef]

- Renner JDP, Carvalho ED (2013). Microrganismos isolados de superfícies da UTI adulta em um hospital do Vale do Rio Pardo—RS. Revista de Epidemiologia e Controle de Infecção., 3(1): 40-44.

- Sfaciotte RAP, Passurolo L, Melo FD, Bordignon G, Israel ND, Salbego FZ, Wosiacki SR, Ferraz SM (2021). Detection of the main multiresistant microorganisms in the environment of a teaching veterinary hospital in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research., 41:e06706, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Souza SGP, Santos IC, Bondezan MAD, Corsatto LFM, Caetano ICS, Zaniolo MM, Matta R, Merlini LS, Barbosa LN, Gonçalves DD (2020) Bacteria with a Potential for Multidrug Resistance in Hospital Material. Microbial Drug Resistance. [CrossRef]

- Anvisa (2017). Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Critérios diagnósticos de infecção relacionada a assistência à saúde. 2.ed. Brasília: Anvisa, 2017. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov. br/documents/33852/3507912/Caderno+2+-, 2017.

- Rosa NOM, Costa CP, Castro MFL, Gaggini MCR, Favaleça MF, Andreani DIK (2021). Análise Microbiológica de Bioaerossóis em uma Unidade de Tratamento Intensivo de Pacientes Afetados por COVID-19. International Journal of Development Research., 11(11): 51938-51941.

- Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice AS, Kjelleberg S (2016). Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nature Reviews Microbiology.,14(9):563–575.

- Damasceno Q (2010). Características epidemiológicas dos microrganismos resistentes presentes em reservatórios de uma Unidade de Terapia Intensiva. Dissertação. Belo Horizonte: Escola de Enfermagem/UFMG.

- Bender JB, Schiffman E, Hiber L, Gerads L, Olsen K (2012). Recovery of Staphylococci from computer keyboards in a veterinary medical centre and the effect of routine cleaning. Vet Rec.,170(16): 414–414. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro LAO, Oliveira MM, Fernandes JD, Marinho CS, Barros A, Castro LMC (2015).Equipment contamination in an intensive care unit. Acta Paul Enferm.,8(2):160-165. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa ER, Machado AP, Bortolini J, Miraveti JC, Corrêa LVA, Valim MD (2021). Bactérias resistentes isoladas de superfícies inanimadas em um hospital público. Cogitare enferm., 26:e74774. [CrossRef]

- Shoen HRC, Rose S, Ramsey AS, Morais H, Bermudez LE (2019). Analysis of staphylococcus infections in a veterinary teaching hospital from 2012 to 2015. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 66:101332. [CrossRef]

- Turk R, Singh A, Weese JS (2015). Prospective surgical site infection surveillance in dogs. Vet Surg.,44(1):2–8. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh A, Kukanich K, Brown CE, Zurek L (2012). Resident Cats in Small Animal Veterinary Hospitals Carry Multi-Drug Resistant Enterococci and are Likely Involved in Cross Contamination of the Hospital Environment. Frontiers Microbiology., 3:62. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande A, Cadnum J, Fertelli D, Sitzlar B, Thota P, Mana TS, Jencson A, Alhmidi H, Koganti S, Donskey CJ (2017). Are Hospital floors na underappreciated reservoir for transmission of health care-associated pathogens? American Journal of Infection Control. 1;45 (3): 336-338. [CrossRef]

- Ye-In Oh, Baek J, Kim SH, Kang BJ, Youn H (2018). Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Distribution of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms Isolated From Environmental Surfaces and Hands of Healthcare Workers in a Small Animal Hospital. Japanese Journal of Veterinary Research., 66(3): 193-202.

- Paula VG, Quintanilha LV, Silva Coutinho FA, Rocha HF, Santos FL (2016). Enterobactérias produtoras de carbapenemase: prevenção da disseminação de superbactérias em UTI’s. Ciências da Saúde., 14(2): 175-185. [CrossRef]

- Lago A, Fuentefria SR, Fuentefria DB (2010). Enterobactérias produtoras de ESBL em Passo fundo, Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Soc Bras Med Trop., 43(4):430-34. [CrossRef]

- Mahl S, Rossi EM (2017). Suspectibilidade antimicrobiana de bactérias isoladas de colchões hospitalares. RBAC., 49(4): 371-375. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira PSF, Moura ERF, Costa MMF, Monteiro WMS, Brondi L (2009). Perfil da Infecção Hospitalar em um Hospital Universitário. Rev. Enferm. UERJ., 17(1):96-101.

- Oliveira FA, Stella AE (2019). Enterobactérias multirresistentes presentes em ambiente hospitalar veterinário. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira.

- Souza WKS, Santana MMR, Libório RC, Santos HAS, Oliveira KR, Guimarães MD, Shiosaki RK, Naue CR (2021) Avaliação da população bacteriana na superfície de macas de um hospital universitário de Pernambuco. Research Society and Development.,10(14):e20101421509. [CrossRef]

- Samreen I.A. et al. (2021). Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: a potential threat to public health. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance., 27:101-111. [CrossRef]

- Tang kl. et al. (2017). Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health., 1(8):e316-e327. [CrossRef]

- Silva IA, Melo CC, Barbosa TSL, Martins LR, Oliveira SR (2023). Estetoscópios de uso hospitalar como fonte de infecção por bactérias resistentes produtoras de biofilme. RBAC. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z, Yang X, Yang L, Jiang J, Ou Y, Molin S, Qu D. (2007). Formation and properties of in vitro biofilms of ica-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:83–93. [CrossRef]

- Otto M. (2009). Staphylococcus epidermidis—The “accidental” pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 7:555–567. [CrossRef]

| General areas | Operating Room | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection 01 | Collection 02 | Collection 03 | ||||||||

| Locations of Collection |

Species bacterial |

Resistance Profile | Biofilm production | Locations of Collection |

Species bacterial |

Resistance Profile | Biofilm production | Species bacterial |

Resistance Profile | Biofilm production |

| Reception desk computer keyboard |

K. pneumoniae S. pseudintermedius |

ESBL MDR |

No Weak |

Heart rate monitor cable pigtails |

S. epidermidis (S2) Bacillus sp. (S2) |

MDR MDR |

Weak Moderate |

Bacillus sp. (S1) Bacillus sp.(S2) Enterobacter sp. (S2) |

NDR NDR NDR |

No Moderate No |

| Screening room stethoscope | S. pseudintermedius | MDR | No | Heart monitor |

S. epidermidis (S1) S. epidermidis (S2) |

MDR/MRS MDR |

No Weak |

Bacillus sp.(S1) S. coagulase-negative (S2) Enterobacter sp. (S2) |

NDR MDR/MRS NDR |

No Weak No |

| Reception desk table |

S. pseudintermedius S. epidermidis E. coli |

MDR/MRSP MRS ESBL |

No No Weak |

Anesthesia machine (vaporizer) |

S. coagulase-negative (S2) S. coagulase-negative (S2)S. epidermidis (S2) |

MDR MDR/MRS NDR |

No Moderate No |

S. coagulase-negative (S1)Bacillus sp. (S1) S. epidermidis (S2) |

NDR NDR MDR |

Weak Weak No |

| Office 02 reception desk |

E. coli Bacillus sp. |

ESBL NDR |

Weak Weak |

Operating table |

S. pseudintermedius Acinetobacter sp. (S2) |

NDR NDR |

No Weak |

Bacillus sp. (S1) Bacillus sp.(S2) |

NDR NDR |

No No |

| Office 02 table for animal screening |

Enterobacter sp. S. epidermidis |

NDR MDR/MRS |

No Weak |

Thermal mat | No bacterial growth | - | - |

Enterococcus sp.(S1) Bacillus sp. (S2) |

NDR NDR |

Weak No |

| Marble counter in the admission room | Enterobacter sp. S. pseudintermedius |

MDR/ESBL MDR/MRSP |

Weak Weak |

Table of surgical instruments |

S. epidermidis (S1) S. pseudintermedius (S2) |

MDR MDR/MRSP |

No Weak |

S. pseudintermedius (S2) Bacillus sp.(S2) |

MDR/MRSP MDR |

Weak Weak |

| Animal care table in the admission room |

E. coli S. aureus |

NDR MDR/MRSP |

No Weak |

Marble countertop |

S. epidermidis (S1) K. pneumoniae (S1) coagulase-negative S. (S2) K. pneumoniae (S2) |

MDR/MRS NDR MDR/MRS MDR/ESBL |

Weak Weak No No |

Bacillus sp.(S1) S. epidermidis (S1) Bacillus sp.(S2) |

NDR MDR/MRS NDR |

Weak Weak Weak |

| Microwave in the admission room |

S. aureus Enterobacter sp |

NDR MDR |

Weak Weak |

Surgical light | coagulase-negative S. (S2) | NDR | Weak |

Bacillus sp. (S1) S. epidermidis (S1) S. coagulase-negative (S2) |

NDR NDR MDR/MRS |

Weak No No |

| Animal pen in the admission room |

S. pseudintermedius Enterobacter sp. |

MDR/MRSP NDR |

Weak Weak |

PPE cabinet surface | coagulase-negative S. (S2) S. coagulase-negative (S2) |

MDR MDR/MRS |

No No |

No bacterial growth | ||

| Infectious Diseases Animals pen |

Bacillus sp. Bacillus sp. |

NDR NDR |

Weak No |

*Sink tap and basin | No growth bacterial |

- | - | No bacterial growth | - | - |

| Equipment named preoperative room trachea |

Bacillus sp. Bacillus sp. |

NDR NDR |

Weak Weak |

*Microwave |

E. coli E. coli Enterococcus sp. |

NDR NDR NDR |

No Weak No |

coagulase-negative S. Bacillus sp. |

MDR/MRS NDR |

Weak Weak |

| Collection 1 | Collection 2 | Collection 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial species | Biofilm phenotypic |

Biofilm genotypic |

Bacterial species | Biofilm phenotypic |

Biofilm genotypic |

Bacterial species | Biofilm phenotypic |

Biofilm genotypic |

|

S. pseudintermedius S. pseudintermedius S. pseudintermedius S. epidermidis S. epidermidis S. pseudintermedius S. aureus S. aureus S. pseudintermedius |

Weak No No No Weak Weak Weak Weak Weak |

No No No No No No No No No |

S. epidermidis S. epidermidis S. epidermidis Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. S. epidermidis S. pseudintermedius S. epidermidis S. pseudintermedius S. epidermidis Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. |

Weak No Weak No Moderate No No No Weak Weak No Weak No No |

Ica A and D No Ica D Ica D Ica D Ica D Ica D Ica A and D Ica A and D Ica D No Ica D No No |

Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. S. epidermidis S. pseudintermedius S. epidermidis S. epidermidis Coagulase-negative S. Coagulase-negative S. |

Weak Weak No Weak Weak No No Weak |

No No No No No Ica A and D Ica A and D Ica A and D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).