Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

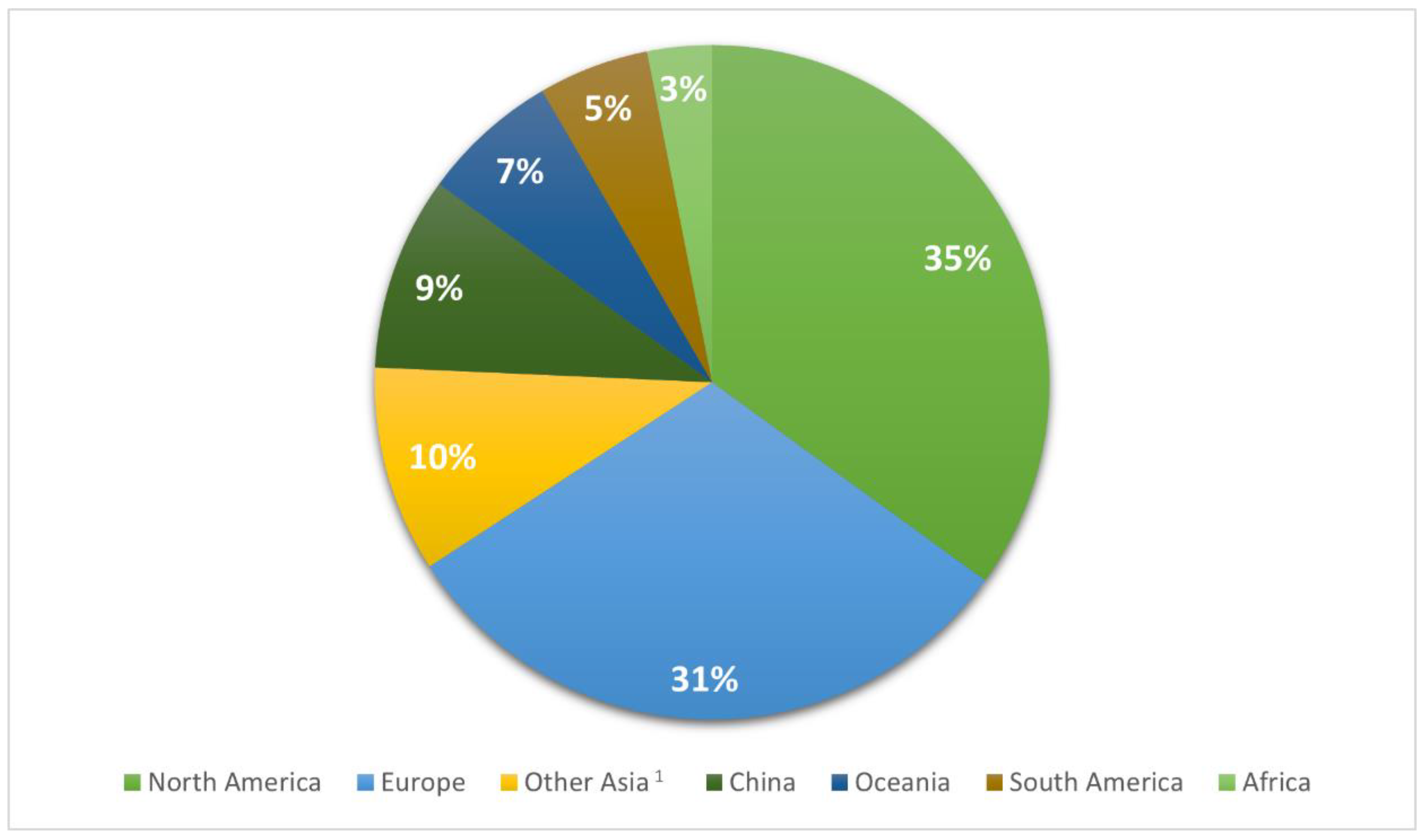

2.1. Data description

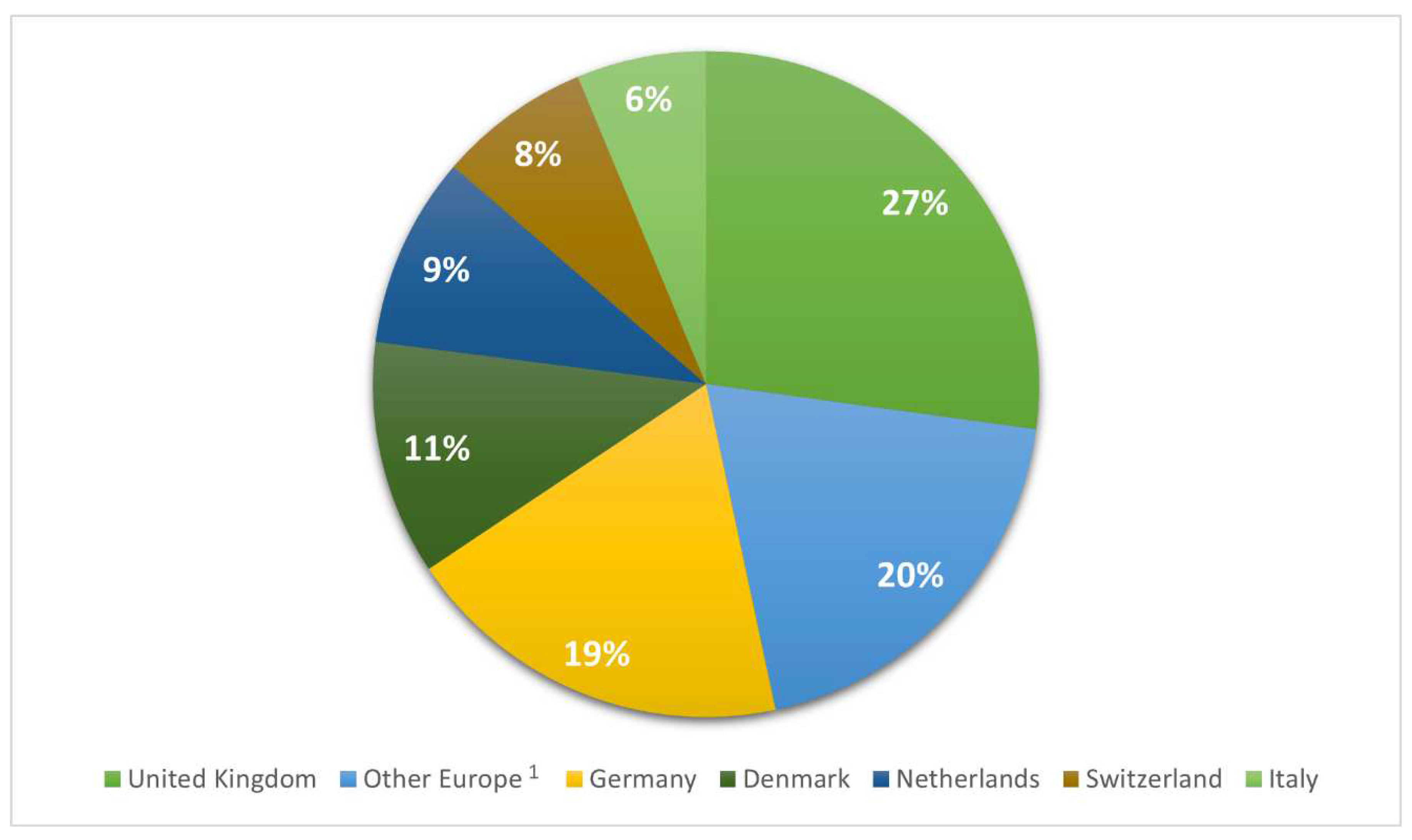

2.2. European isolates

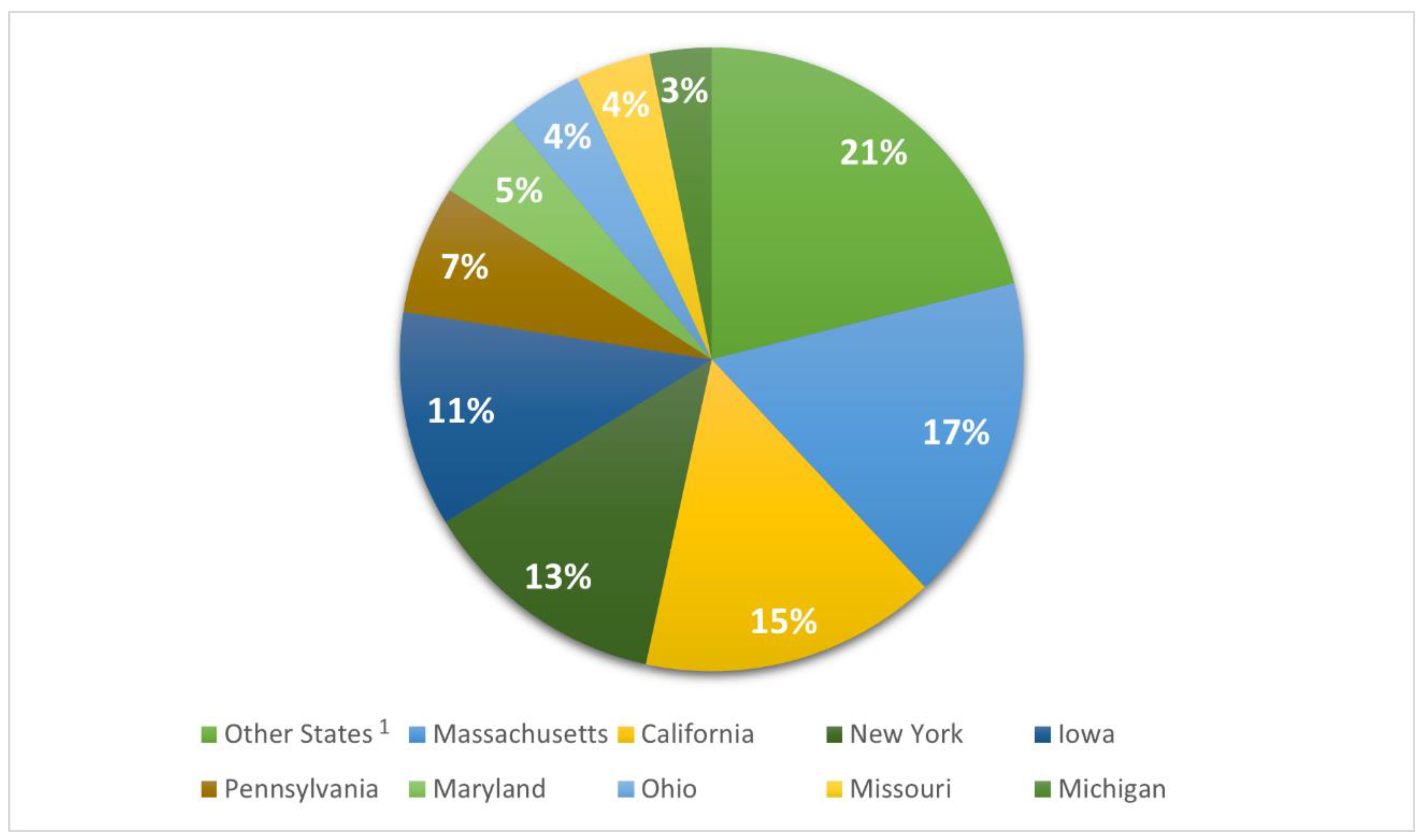

2.3. USA isolates

2.4. Resistance gene distribution

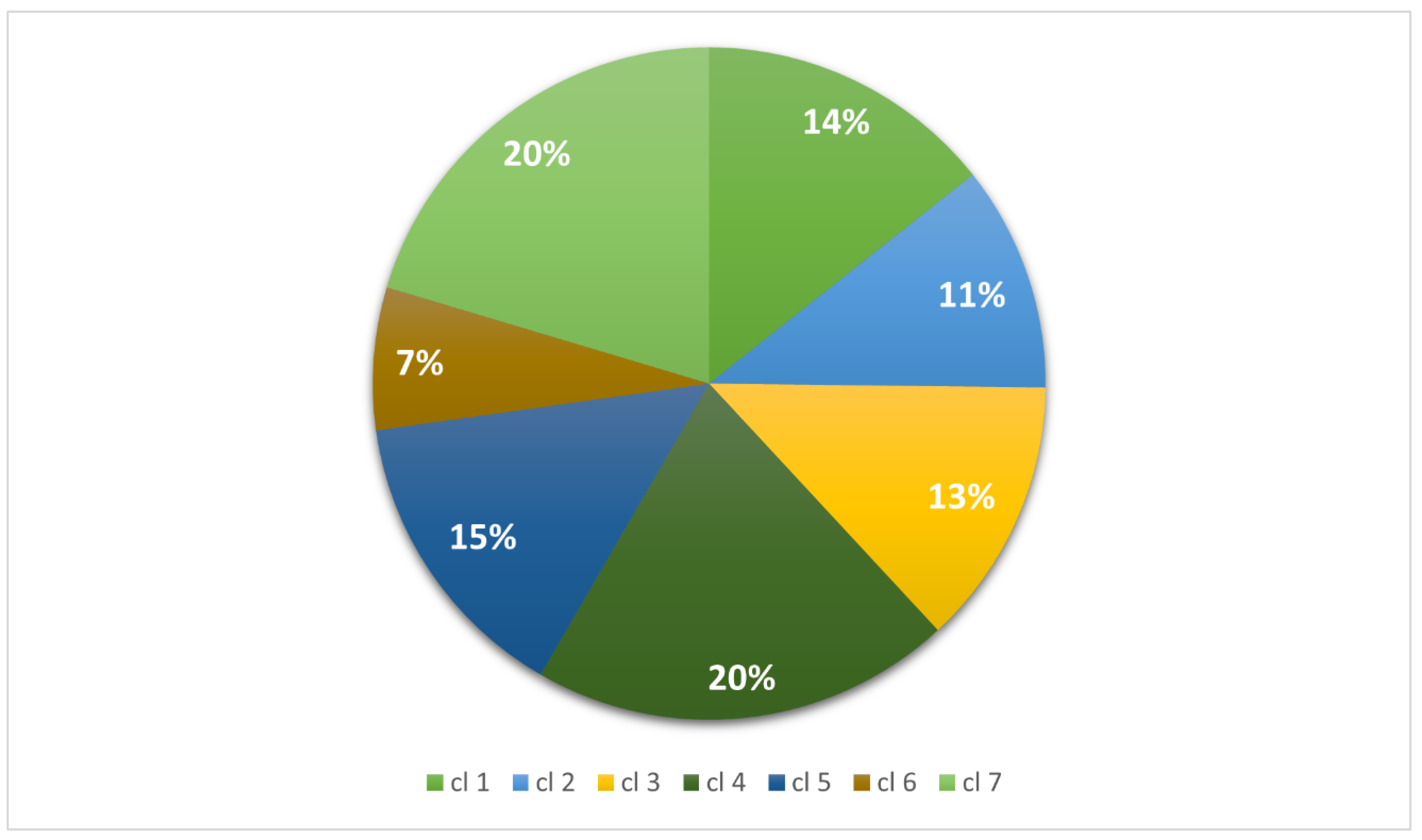

2.5. Cluster analyses

2.5.1. Association between gene-cluster and geographical area of submission

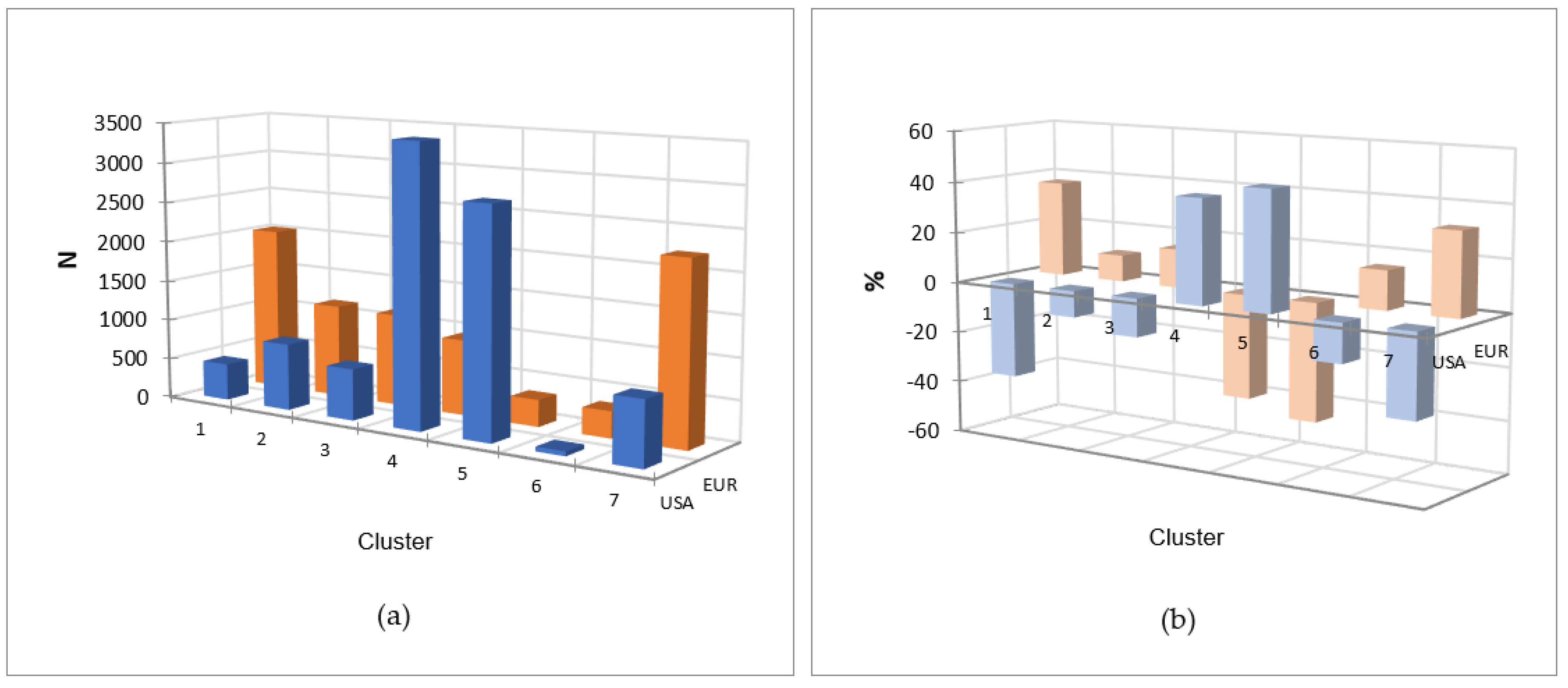

2.5.2. European and USA isolates

| State | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2 N (%) |

Cluster 3 N (%) |

Cluster 4 N (%) |

Cluster 5 N (%) |

Cluster 6 N (%) |

Cluster 7 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1243e 1 (61.1) |

377b (32.6) |

150d (13.2) |

273e (29.3) |

11b (3.3) |

53b (16.2) |

105f (4.7) |

| Other Europe2 | 408d (20.1) |

252a (21.9) |

266c (23.3) |

157c, e (16.8) |

89a (26.9) |

107d (32.8) |

310d (13.9) |

| Germany | 227 b (11.2) |

164b (14.2) |

210b, c (18.5) |

90b (9.6) |

90a (27.2) |

57b (17.4) |

709b (31.8) |

| Denmark | 90a (4.4) |

153a (13.3) |

289a (25.4) |

12a (1.3) |

61a (18.4) |

3a (0.9) |

320a (14.4) |

| Netherlands | 7c (0.3) |

82b (7.1) |

102b, c (9) |

0d (0.0) |

1b (0.3) |

0a (0.0) |

562c (25.2) |

| Switzerland | 11c (0.5) |

56b (4.9) |

56b,d (4.9) |

364f (39) |

41a (12.4) |

23b, d (7) |

48e (2.2) |

| Italy | 48a (2.4) |

69a, b (6) |

65b, c (5.7 ) |

37b, c (4) |

38a (11.5) |

84c (25.7) |

174a (7.8) |

| Total | 2034 (100) |

1153 (100) |

1138 (100) |

933 (100) |

331 (100) |

327 (100) |

2228 (100) |

| State | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2 N (%) |

Cluster 3 N (%) |

Cluster 4 N (%) |

Cluster 5 N (%) |

Cluster 6 N (%) |

Cluster 7 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other States1 | 95b, d, f, h 2 (20.9) |

290a (35.2) |

253d (39.9) |

496c (14.4) |

387b (13.8) |

13a, b, c (22.7) |

365b (46.1) |

| Massachusetts | 15i (3.3) |

7g (0.8) |

18a (2.8) |

1191b (34.4) |

268b (9.6) |

1c (1.8) |

30a, b, c (3.8) |

| California | 87a, b, c, d, e, f, g (19.1) |

170a, b (20.6) |

10a (1.6) |

587a (17) |

492a (17.5) |

20a (35.1) |

22a (2.8) |

| New York | 101 c, g (22.2) |

122a, b, c (14.8) |

97b (15.3) |

114e (3.3) |

661c (23.6) |

13a, b (22.7) |

52c (6.6) |

| Iowa | 31h (6.8) |

90b, c, d, e, f (10.9) |

78b (12.3) |

402a (11.6) |

227b (8.1) |

1b, c (1.8) |

178b (22.5) |

| Pennsylvania | 54a, c, e, g (11.9) |

37c, d, e, f (4.5) |

36b (5.7) |

231a (6.7) |

221a (7.9) |

5a, b, c (8.8) |

18a, c (2.3) |

| Maryland | 35e, f, g (7.7) |

18e, f (2.2) |

21b (3.3) |

85c (2.5) |

251c (9) |

3a, b, c (5.3) |

16a, c (2) |

| Ohio | 11b, d, f, h, i (2.4) |

32a, b, c, d, e, f (3.9) |

19b (3) |

143a (4.1) |

122a (4.4) |

0a, b, c (0.0) |

36d (4.5) |

| Missouri | 9d, h, i (2) |

46a, b (5.6) |

86c (13.6) |

20e (0.6) |

120a (4.3) |

1a, b, c (1.8) |

70b (8.8) |

| Michigan | 17a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h (3.7) |

12d, f (1.5) |

16b (2.5) |

185d (5.4) |

49b (1.8) |

0a, b, c (0.0) |

5a, c (0.6) |

| Total | 455 (100) |

824 (100) |

634 (100) |

3454 (100) |

2798 (100) |

57 (100) |

792 (100) |

2.6. Isolates from humans (clinical sources)

| State | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2 N (%) |

Cluster 3 N (%) |

Cluster 4 N (%) |

Cluster 5 N (%) |

Cluster 6 N (%) |

Cluster 7 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 880e 1 (75.5) |

244b (40.6) |

39f (8.1) |

217g (65.7) |

7c (4.5) |

25a, c (26.3) |

28c (4.6) |

| Other Europe2 | 122d (10.5) |

122b, c (20.3) |

97a, c, d, e (20.2) |

69f, g (20.8) |

21a (13.4) |

14a, b, c (14.7) |

148a (24.2) |

| Germany | 74b (6.4) |

106b, c (17.6) |

132d, e (27.4) |

15d, e (4.5) |

47b (29.9) |

14a, b, c (14.7) |

198b (32.4) |

| Denmark | 53a (4.5) |

9a (1.5) |

37a, b, c, d, e (7.7) |

2a, b, c, d, e (0.6) |

14a (8.9) |

2a, b, c (2.1) |

36a, b (5.9) |

| Netherlands | 7c (0.6) |

72c (12) |

97b (20.2) |

0b, e (0.0) |

0c (0.0) |

0c (0.0) |

106b (17.3) |

| Switzerland | 5b, c (0.4) |

6a (1) |

31a, b, c, d, e (6.4) |

8a, c, d, f, g (2.4) |

41d (26.1) |

7b, d (7.4) |

17a (2.8) |

| Italy | 24b (2.1) |

42a, b, c (7) |

48c, e (10) |

20c, f (6) |

27b (17.2) |

33d (34.8) |

78a, b (12.8) |

| Total | 1165 (100) |

601 (100) |

481 (100) |

331 (100) |

157 (100) |

95 (100) |

611 (100) |

| State | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2 N (%) |

Cluster 3 N (%) |

Cluster 4 N (%) |

Cluster 5 N (%) |

Cluster 6 N (%) |

Cluster 7 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other States1 | 56b, d, f, g, h, i, j, k 2 (16.4) |

166a(27) |

145d (29.3) |

363f (12.9) |

204b, c (9.2.) |

10a, b, c (20.8) |

209b (34.7) |

| Massachusetts | 10l (2.9) |

6g (1) |

13b (2.6) |

974b (34.7) |

207c (9.3) |

1c (2.1) |

28a (4.7) |

| California | 49a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k (14.3) |

113a, b (18.4) |

9a, b (1.8) |

340a (12.1) |

292a (13.2) |

14a (29.1) |

12a (2) |

| New York | 96c (28.1) |

107a, b, c, e (17.4) |

85c (17.1) |

112e (4) |

616d (27.7) |

13a, b (27.1) |

39a (6.5) |

| Iowa | 31h, i, j, k (9) |

89b, c, d, e, f (14.5) |

78c (15.7) |

401a (14.3) |

227b (10.2) |

1b, c (2.1) |

176b (29.3) |

| Pennsylvania | 54a, c, e (15.7) |

36c, d, e, f (5.9) |

35c (7) |

226a, f (8) |

219a (9.9) |

5a, b, c (10.4) |

18a (3) |

| Maryland | 22a, b, c, d, e, f, g (6.4) |

13f (2.1) |

11a, c (2.2) |

56c (2) |

166d (7.5) |

3a, b, c (6.3) |

11a, c (1.8) |

| Ohio | 8b, d, f, g, h, i, j, k, l (2.3) |

28a, b, c, d, e, f (4.6) |

19c (3.8) |

136a, f (4.8) |

119a (5.4) |

0a, b, c (0.0) |

34c (5.7) |

| Missouri | 9d, g, i, k, l (2.6) |

46a, b (7.5) |

86e (17.3) |

20e (0.7) |

120a (5.4) |

1a, b, c, (2.1) |

70b (11.6) |

| Michigan | 8e, f, g, j, k, l (2.3) |

10d, f (1.6) |

16c, d (3.2) |

183d (6.5) |

49b, c (2.2) |

0a, b, c (0.0) |

4a (0.7) |

| Total | 343 (100) |

614 (100) |

497 (100) |

2811 (100) |

2219 (100) |

48 (100) |

601 (100) |

2.7. Isolates from animals, food and environment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. NCBI pathogen detection isolate browser and antibacterial data (NPDIB)

4.2. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gajdács, M. The Continuing Threat of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Antibiotics 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, L.R.; Haack, S.K.; Johnson, H.E.; Brennan, A.K.; Isaacs, N.M.; Spencer, C. Staphylococcus Aureus and Methicillin-Resistant s. Aureus (MRSA) at Ambient Freshwater Beaches. J Water Health 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G. Staphylococcus Aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertheim, H.F.L.; Melles, D.C.; Vos, M.C.; Van Leeuwen, W.; Van Belkum, A.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Nouwen, J.L. The Role of Nasal Carriage in Staphylococcus Aureus Infections. Lancet Infectious Diseases 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Sharara, F.; Mestrovic, T.; Gray, A.P.; Davis Weaver, N.; Wool, E.E.; Han, C.; Gershberg Hayoon, A.; et al. Global Mortality Associated with 33 Bacterial Pathogens in 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2022, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, C.J.; Gerbig, G.R.; Sensius, L.D.; Patel, V.; Smith, T.C. Staphylococcus Aureus Epidemiology in Wildlife: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Ronholm, J. Staphylococcus Aureus in Agriculture: Lessons in Evolution from a Multispecies Pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Moein, K.A.; Samir, A. Isolation of Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus Aureus from Pet Dogs and Cats: A Public Health Implication. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Liao, G.; Wu, Z.; Lv, J.; Chen, W. Prevalence and Characterization of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates from Subclinical Bovine Mastitis in Southern Xinjiang, China. J Dairy Sci 2020, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szafraniec, G.M.; Szeleszczuk, P.; Dolka, B. Review on Skeletal Disorders Caused by Staphylococcus Spp. in Poultry. Veterinary Quarterly 2022, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Rivas, J.M.; Brown, E.L.; Liang, X.; Höök, M. Virulence Potential of the Staphylococcal Adhesin CNA in Experimental Arthritis Is Determined by Its Affinity for Collagen. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2004, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Y.; Islam, M.A.; Muzahid, N.H.; Sikder, M.O.F.; Hossain, M.A.; Marzan, L.W. Characterization, Prevalence and Antibiogram Study of Staphylococcus Aureus in Poultry. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2017, 7, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, F.M.; Soliman, A.A.; Ibrahim, G.A.; Saleh, H.A. Advanced Bacteriological Studies on Bumblefoot Infections in Broiler Chicken with Some Clinicopathological Alteration. Veterinary Science and research 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Duijkeren, E.; Jansen, M.D.; Flemming, S.C.; De Neeling, H.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Schoormans, A.H.W.; Van Nes, A.; Fluit, A.C. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Pigs with Exudative Epidermitis. Emerg Infect Dis 2007, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpa, J.M.; Hermans, K.; Haesebrouck, F. Main Pathologies Associated with Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Rabbits: A Review. World Rabbit Science 2010, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, D.; Selva, L.; Callanan, J.J.; Guerrero, I.; Ferrian, S.; Corpa, J.M. Strains of Staphylococcus Aureus and Pathology Associated with Chronic Suppurative Mastitis in Rabbits. Veterinary Journal 2011, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadariya, J.; Smith, T.C.; Thapaliya, D. Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcal Food-Borne Disease: An Ongoing Challenge in Public Health. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States-Major Pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA Journal 2022, 20. [CrossRef]

- Zaghen, F.; Sora, V.M.; Meroni, G.; Laterza, G.; Martino, P.A.; Soggiu, A.; Bonizzi, L.; Zecconi, A. Epidemiology of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphyloccocus Aureus Isolates from a Public Database in a One Health Perspective—Sample Characteristics and Isolates’ Sources. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.M.L.; Lloyd, D.H.; Lindsay, J.A. Staphylococcus Aureus Host Specificity: Comparative Genomics of Human versus Animal Isolates by Multi-Strain Microarray. Microbiology (N Y) 2008, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepheard, M.A.; Fleming, V.M.; Connor, T.R.; Corander, J.; Feil, E.J.; Fraser, C.; Hanage, W.P. Historical Zoonoses and Other Changes in Host Tropism of Staphylococcus Aureus, Identified by Phylogenetic Analysis of a Population Dataset. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.W.; Bergeron, G.; Bourassa, M.W.; Dickson, J.; Gomes, F.; Howe, A.; Kahn, L.H.; Morley, P.S.; Scott, H.M.; Simjee, S.; et al. Complexities in Understanding Antimicrobial Resistance across Domesticated Animal, Human, and Environmental Systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2019, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennone, V.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Prieto-Maradona, M.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A. Integration of Genomics in Surveillance and Risk Assessment for Outbreak Investigation. EFSA Journal 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meroni, G.; Sora, V.M.; Martino, P.A.; Sbernini, A.; Laterza, G.; Zaghen, F.; Soggiu, A.; Zecconi, A. Epidemiology of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Streptococcus Agalactiae Sequences from a Public Database in a One Health Perspective. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinini, R.; Borromeo, V.; Zecconi, A. Relationship between S. Aureus Gene Pattern and Dairy Herd Mastitis Prevalence. Vet Microbiol 2010, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarestrup, F.M.; Wegener, H.C.; Jensen, N.E.; Jonsson, O.; Myllys, V.; Thorberg, B.M.; Waage, S.; Rosdahl, V.T. A Study of Phage- and Ribotype Patterns of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated from Bovine Mastitis in the Nordic Countries. Acta Vet Scand 1997, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.D.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Jensen, N.E. Geographical Variation in the Presence of Genes Encoding Superantigenic Exotoxins and β-Hemolysin among Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated from Bovine Mastitis in Europe and USA. Vet Microbiol 2002, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppens, J.; Xavier, B.B.; Vlaeminck, J.; Larsen, J.; Lammens, C.; Van Puyvelde, S.; Goossens, H.; Larsen, A.R.; Malhotra-Kumar, S. Genomic Analysis of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Clonal Complex 239 Isolated from Danish Patients with and without an International Travel History. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, S.; Xavier, B.B.; Vanjari, L.; Coppens, J.; Lammens, C.; Vemu, L.; Carevic, B.; Hryniewicz, W.; Jorens, P.; Kumar-Singh, S.; et al. Remarkable Geographical Variations between India and Europe in Carriage of the Staphylococcal Surface Protein-Encoding SasX/SesI and in the Population Structure of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Belonging to Clonal Complex 8. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetsch, A.; Etter, D.; Johler, S. Livestock-Associated Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus—Current Situation and Impact From a One Health Perspective. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Sabokroo, N.; Wang, Y.; Hashemian, M.; Karamollahi, S.; Kouhsari, E. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Epidemiology of Vancomycin-Resistance Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Tong, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Fan, H. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Healthy Chinese Population: A System Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Gandra, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Current Status and Future Directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, O.U.; Ayobami, O.; Abouelfetouh, A.; Mourabit, N.; Kaba, M.; Egyir, B.; Abdulgader, S.M.; Shittu, A.O. A 6-Year Update on the Diversity of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Clones in Africa: A Systematic Review. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, S.; Chung, D.R.; Lindsay, J.A.; Friedrich, A.W.; Kearns, A.M.; Westh, H.; MacKenzie, F.M. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA): Global Epidemiology and Harmonisation of Typing Methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU Veterinary Medicinal Product Database [Internet]. European Medicines Agency; 2019 [Cited 2023 Sep 5]. Available from: Http://Data.Europa.Eu/88u/Dataset/Eu-Veterinary-Medicinal-Product-Database.

- Tiseo, K.; Huber, L.; Gilbert, M.; Robinson, T.P.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis 5th Ed.; 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons 2011, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-74991-3.

| Geographical Region | NHA1 | HUA | UNK | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | N % |

595a 2 (6.4) |

7940b (77.7) |

1470c (15.9) |

9255 (100) |

| Europe | N % |

490a (6) |

3441b (42.3) |

4213c (51.7) |

8144 (100) |

| Other Asia3 | N % |

135a (5.2) |

1832b (70.3) |

639c (24.5) |

2606 (100) |

| China | N % |

685a (27.8) |

802b (32.6) |

974c (39.6) |

2461 (100) |

| Oceania | N % |

85a (4.9) |

1472b (84.6) |

183c (10.5) |

1740 (100) |

| South America | N % |

13a (0.9) |

1369b (98.2) |

12c (0.9) |

1394 (100) |

| Africa | N % |

56a (6.7) |

545a (65.7) |

229a (27.6) |

830 (100) |

| State | NHA1 | HUA | UNK | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | N % |

73a 2 (3.3) |

1440b (65.1) |

699a (31.6) |

2212 (100) |

| Other Europe3 | N % |

129a (8.1) |

593b (37.3) |

867c (54.6) |

1589 (100) |

| Germany | N % |

135a (8.7) |

586b (37.9) |

826c (53.4) |

1547 (100) |

| Denmark | N % |

3a (0.3) |

153b (16.5) |

722c (83.2) |

928 (100) |

| Netherlands | N % |

8a (1.1) |

282b (37.4) |

464c (61.5) |

754 (100) |

| Switzerland | N % |

81a (13.5) |

115b (19.2) |

403c (67.3) |

599 (100) |

| Italy | N % |

61a (11.8) |

272b (52.8) |

182c (35.3) |

515 (100) |

| State | NHA1 | HUA | UNK | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other States2 | N % |

243a 3 (12.8) |

1153b (60.7) |

503c (26.5) |

1899 (100) |

| Massachusetts | N % |

0a (0.0) |

1239b (81) |

291c (19) |

1530 (100) |

| California | N % |

0a (0.0) |

829b (59.7) |

559c (40.3) |

1388 (100) |

| New York | N % |

74a (6.4) |

1068a (92.1) |

18b (1.6) |

1160 (100) |

| Iowa | N % |

0a (0.0) |

1003b (99.6) |

4a (0.4) |

1007 (100) |

| Pennsylvania | N % |

2a (0.3) |

593b (98.5) |

7a (1.2) |

602 (100) |

| Maryland | N % |

121a (28.2) |

282b (65.7) |

26c (6.1) |

429 (100) |

| Ohio | N % |

0a (0.0) |

344b (94.8) |

19c (5.2) |

363 (100) |

| Missouri | N % |

0a (0.0) |

352b (100) |

0a (0.0) |

352 (100) |

| Michigan | N % |

3a (1.1) |

270b (95.1) |

11a (3.9) |

284 (100) |

| Geographical Region | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2 N (%) |

Cluster 3 N (%) |

Cluster 4 N (%) |

Cluster 5 N (%) |

Cluster 6 N (%) |

Cluster 7 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 456e 1 (12.1) |

977c (34.1) |

651c (19.1) |

3471f (64.9) |

2802f (73.5) |

59f (3.3) |

839e (15.6) |

| Europe | 2034b (53.7) |

1153a (40.3) |

1138d (33.3) |

933a (17.5) |

331d (8.7) |

327d (18.1) |

2228a (41.4) |

| Other Asia2 | 229a (6) |

193b (6.7) |

225c (6.6) |

236b, d (4.4) |

255a (6.7) |

1019c (56.2) |

449d (8.3) |

| China | 622b (16.4) |

159b (5.5) |

468b (13.7) |

359e (6.7) |

28b (0.7) |

38b (2.1) |

787b (14.6) |

| Oceania | 335c (8.8) |

122b (4.3) |

401a (11.7) |

131c, d (2.4) |

43e (1.1) |

33b (1.8) |

675c (12.5) |

| South America | 38a (1) |

127b, c (4.4) |

344c (10.1) |

136a, b, c, d (2.5) |

289e (7.6) |

256e (14.2) |

204d (3.8) |

| Africa | 75a (2) |

136a (4.7) |

188a, b (5.5) |

84a, b, c, d (1.6) |

66a (1.7) |

77a (4.3) |

204a (3.8) |

| Total | 3789 (100) |

2867 (100) |

3415 (100) |

5350 (100) |

3814 (100) |

1809 (100) |

5386 (100) |

| Geographical Region | Cluster 1 N (%) |

Cluster 2N (%) | Cluster 3N (%) | Cluster 4N (%) | Cluster 5N (%) | Cluster 6N (%) | Cluster 7N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 344a 1 (14.7) |

631a (39.6) |

508d (25.5) |

2824d (76) |

2222e (76.7) |

49b (3.3) |

612d (23.3) |

| Europe | 1165f (49.6) |

601d (37.7) |

481b (24.3) |

331a (8.9) |

157c (5.4) |

95d (6.4) |

611c (23.3) |

| Other Asia2 | 161c (6.8) |

43c (2.7) |

37c (1.9) |

187a, c (5) |

141a (4.9) |

989e (66.7) |

274c (10.4) |

| China | 328d (13.9) |

56a, b (3.5) |

89b (4.5) |

109c (2.9) |

5b (0.2) |

4b,c (0.3) |

211a (8) |

| Oceania | 288e (12.2) |

83b (5.2) |

386a (19.5) |

87b (2.4) |

42c (1.4) |

28c, d (1.9) |

558b (21.2) |

| South America | 37b (1.6) |

121a (7.6) |

340a (17.1) |

133a, c (3.6) |

287d (9.9) |

250f (16.9) |

201c (7.7) |

| Africa | 29a, b, c, d (1.2) |

59a (3.7) |

142a (7.2) |

45a, b, c (1.2) |

43a (1.5) |

67a (4.5) |

160a (6.1) |

| Total | 2352 (100) |

1594 (100) |

1983 (100) |

3716 (100) |

2897 (100) |

1482 (100) |

2627 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).