Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

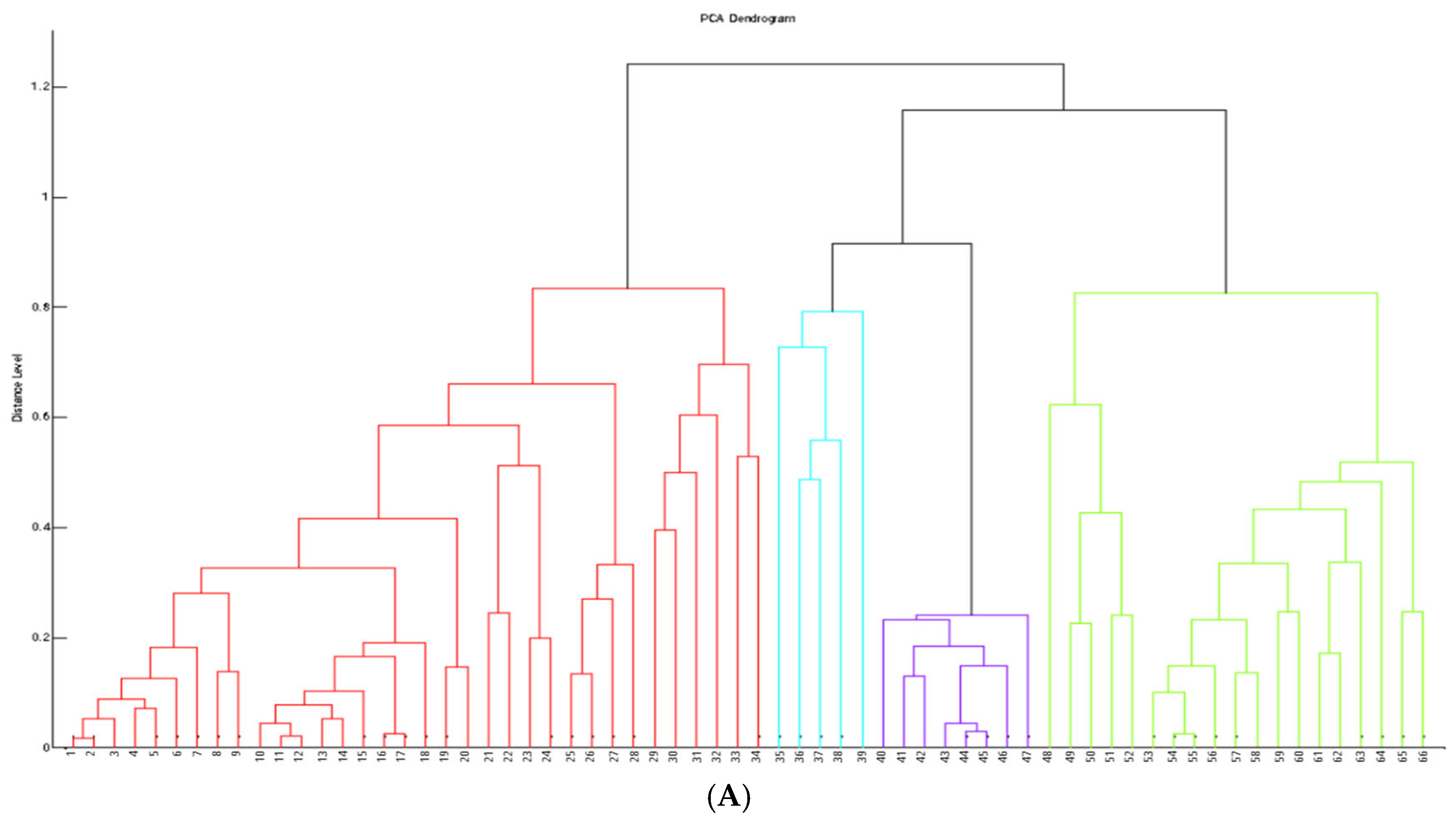

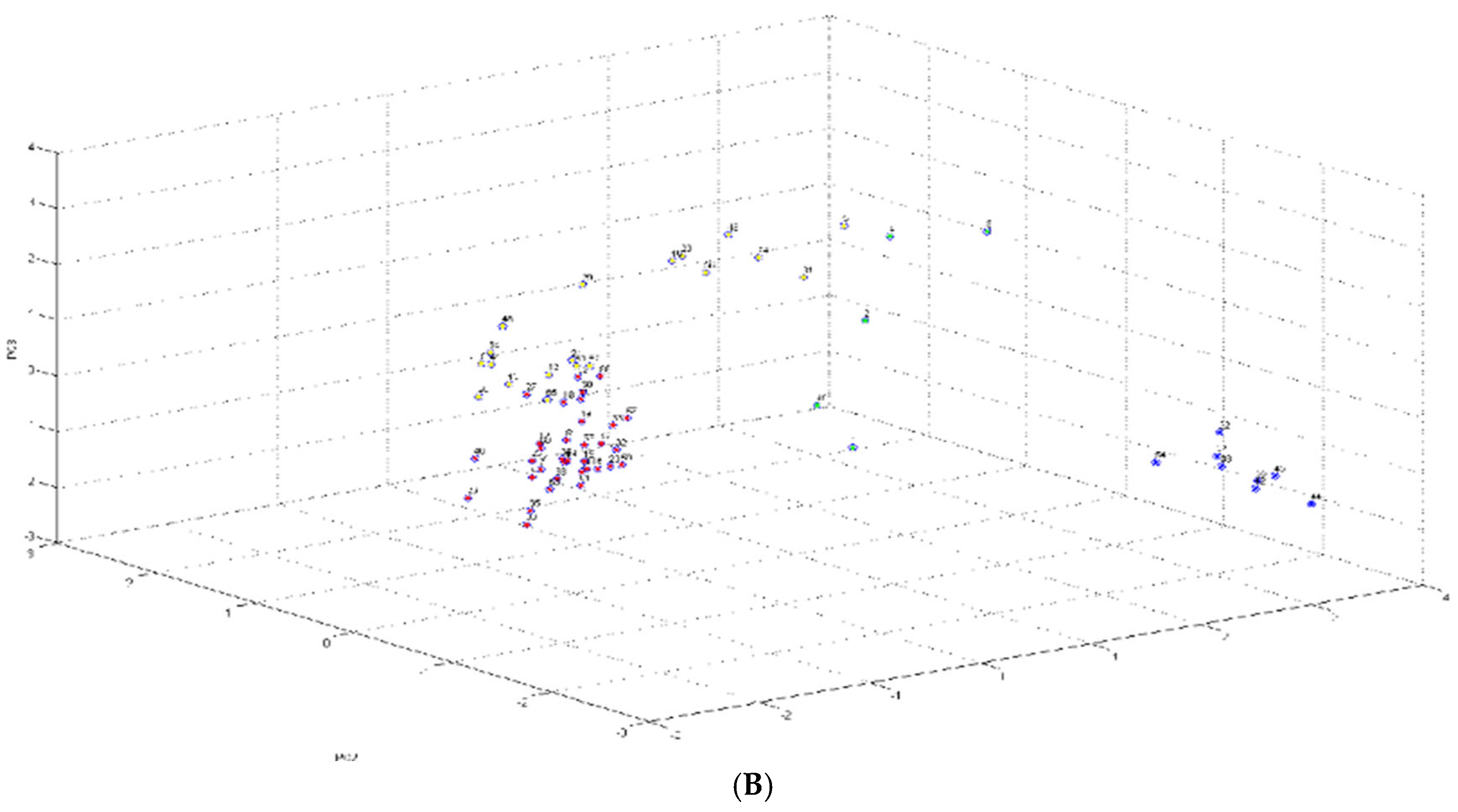

2.1. Identification and Cluster Analysis

2.2. Antimicrobial Phenotyping Testing

2.2.1. Disk Diffusion Method

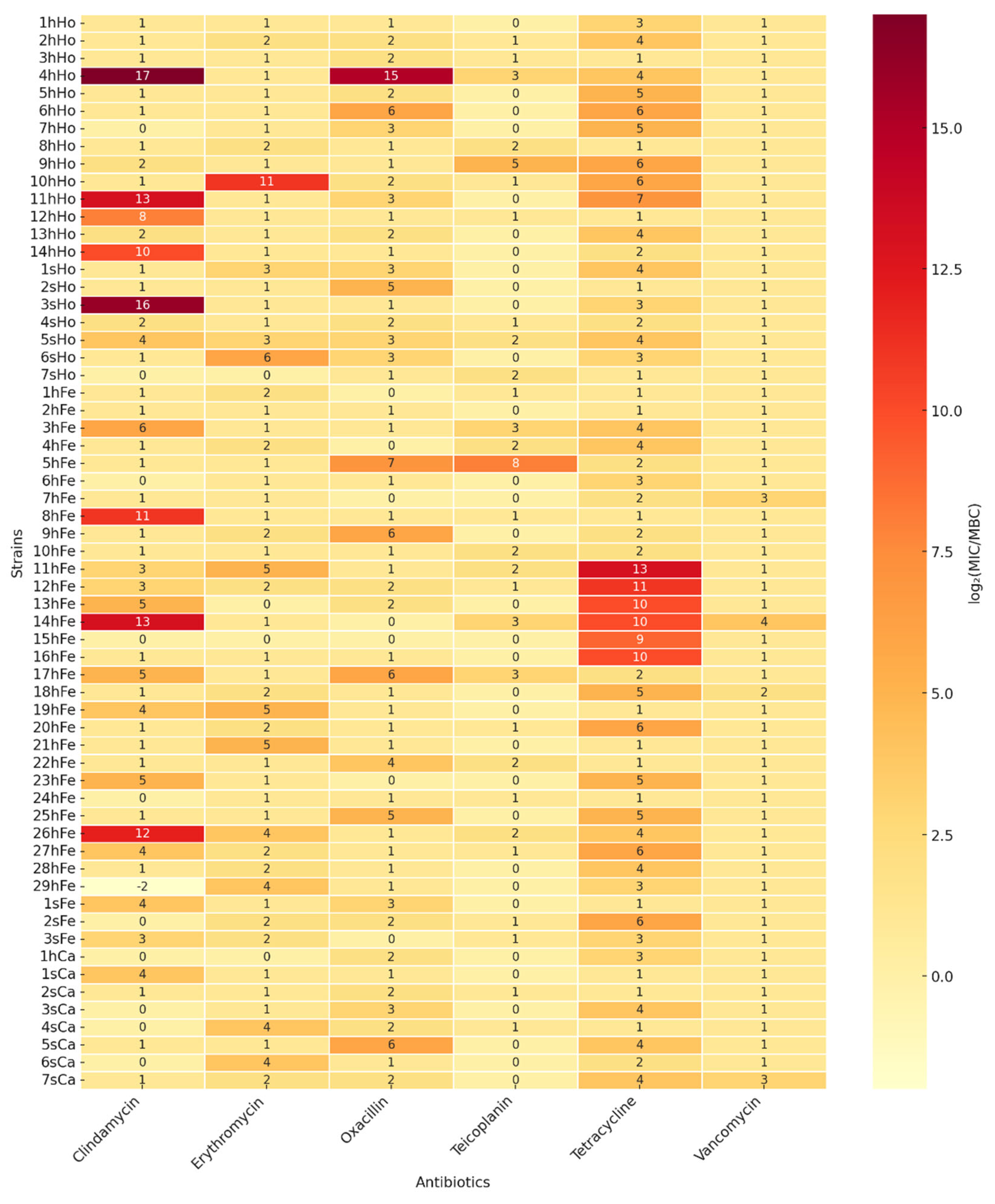

2.2.2. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration and Minimal Bactericidal Concentration for Selected Antimicrobials

2.3. Detection of Resistance Genes Using PCR–Based Genotypic Analysis

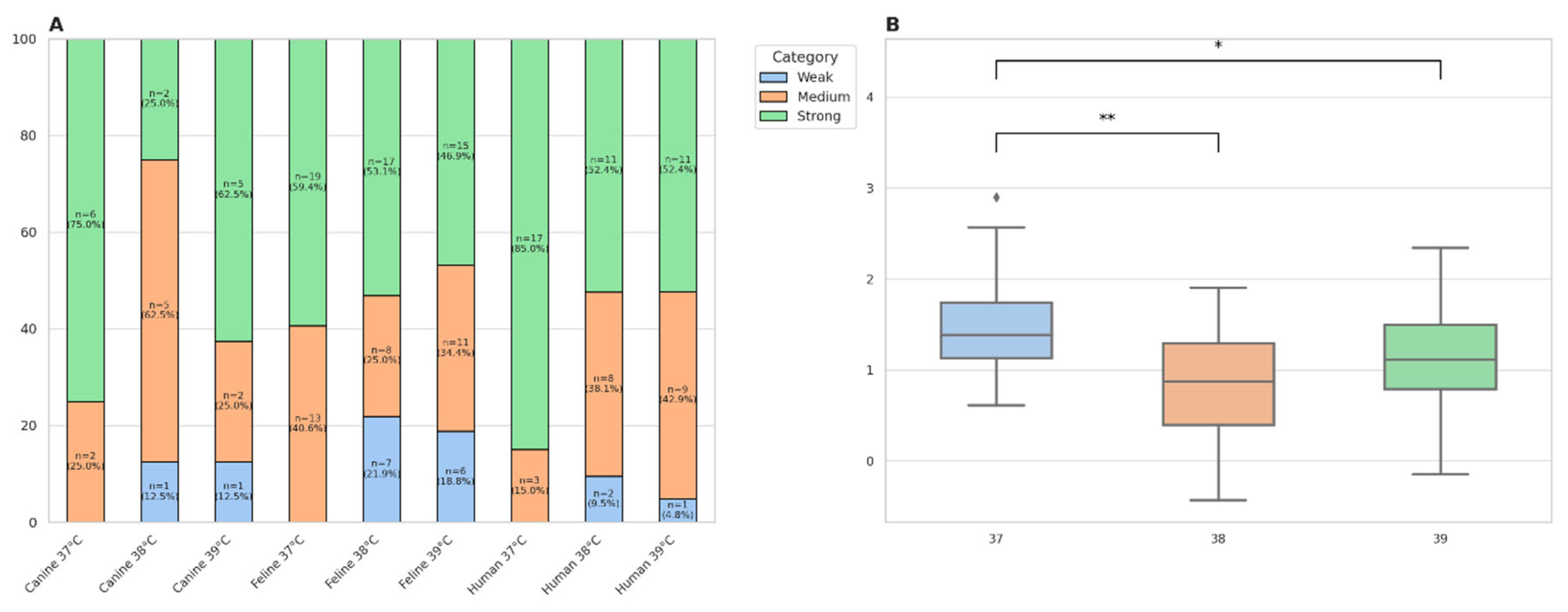

2.4. Bacterial Growth Curves and Biofilm Formation

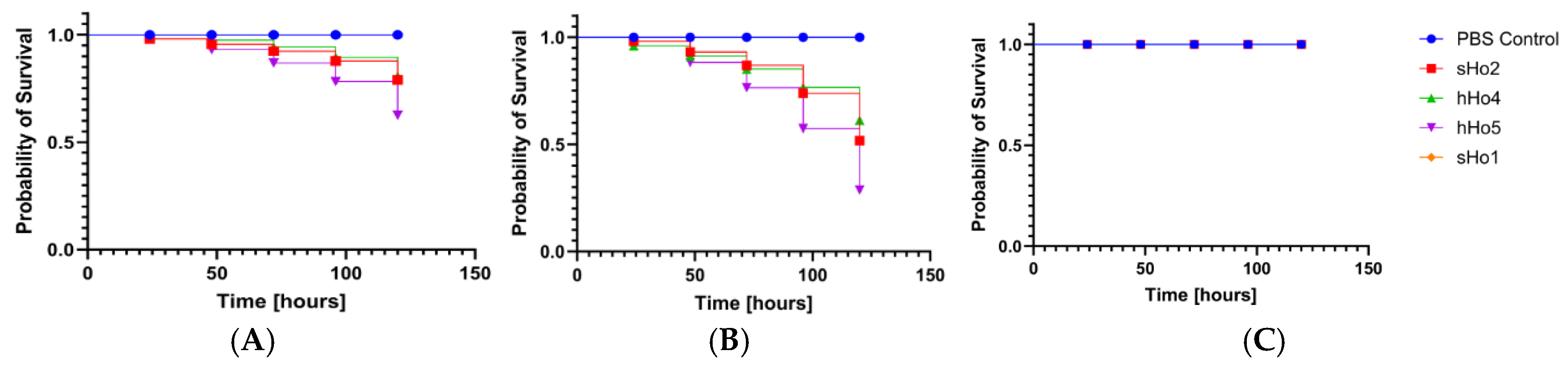

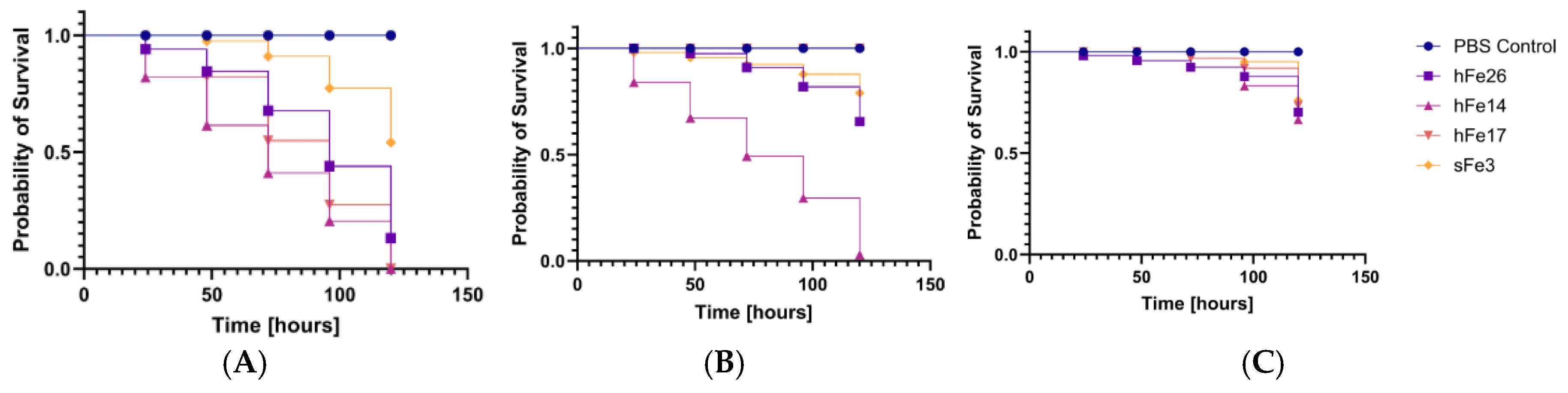

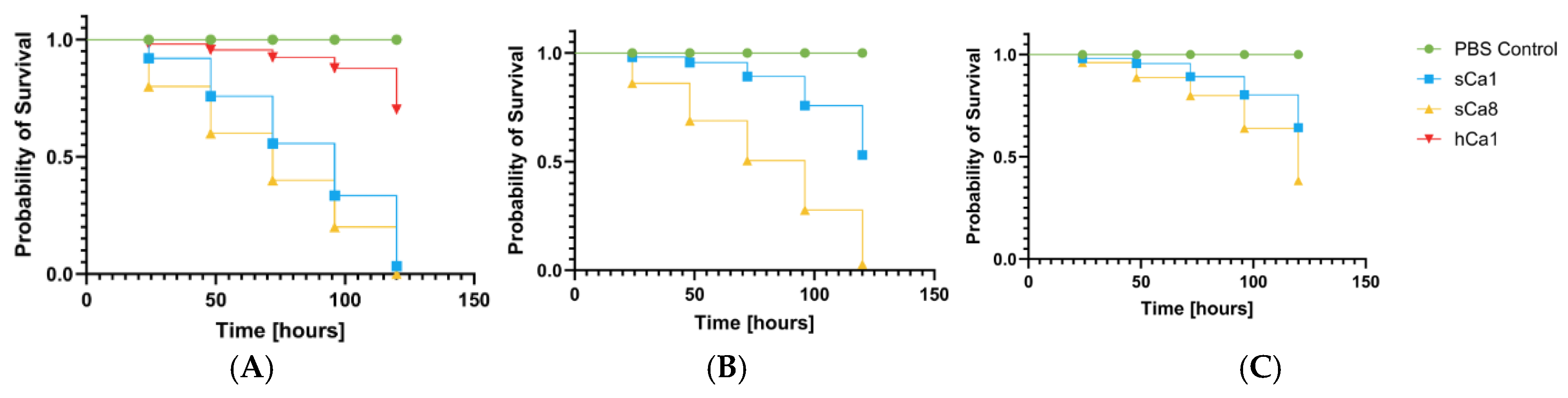

2.5. Pathogenicity Tests on Galleria mellonella Larvae Model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. S. saprophyticus Strains Collection

4.2. Identification of S. saprophyticus

4.3. Detection of hrcA and Resistance Genes Using PCR-Based Genotypic Analysis

4.4. Antimicrobial Phenotypic Testing

4.5. Bacterial Growth Curves and Biofilm Formation

4.6. Pathogenicity Tests on Galleria mellonella Larvae Model

4.7. Statistical Methods

Supplementary Materials

References

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase–negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 870–926. [PubMed].

- Podkowik, M.; Bania, J.; Schubert, J.; Bystroń, J. Gronkowce koagulazo–ujemne: nowe zagrożenie dla zdrowia publicznego. Życie Wet. 2014, 89, 60–64.

- Huebner, J.; Goldmann, D.A. Coagulase–negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999, 50, 223–236. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C.; Ziebuhr, W.; Becker, K. Are coagulase–negative staphylococci virulent? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25(9), 1071–1080. [CrossRef].

- Otto, M. Virulence factors of coagulase–negative staphylococci. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 1295–1309 .[PubMed ]. [CrossRef]

- Raz, R.; Colodner, R.; Kunin, C.M. Who are you Staphylococcus saprophyticus? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40(6), 896–898. [CrossRef].

- Rupp, M.E.; Soper, D.E.; Archer, G.L. Colonization of the female genital tract with Staphylococcus saprophyticus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30(11), 2975–2979. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Białek, B.; Tyski, S.; Hryniewicz, W.; Kasprowicz, A,; Heczko, P.B. Role of Staphylococcus saprophyticus in human infection. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 1990, 39(3–4), 129135. [PubMed].

- Latham, R.H.; Running, K.; Stamm, W.E. Urinary tract infections in young adult women caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. JAMA 1983, 250(22), 3036–3066. [PubMed].

- Hovelius, B.; Mårdh, P.A. Staphylococcus saprophyticus as common cause of urinary tract infections. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1984, 6(3), 328–337. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.F.; Riley, T.V. Staphylococcus saprophyticus urinary tract infections: epidemiological data from Western Australia. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 12, 51–54. [Springer]. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.A.; Iravani, A.; Richard, G.A.; Baer, H. Urinary tract infection caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. J. Infect. Dis. 1980, 142, 510–515. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Garduño, E.; Márquez, I.; Beteta, A.; Said, I.; Blanco, J.; Pineda, T. Staphylococcus saprophyticus causing native valve endocarditis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 37(9), 690–691. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, D.; Yamane, H.; Tabakodani, H.; Yamagishi, H.; Nakazato, E.; Kimura, Y.; Shinjoh, M.; Yamagata, T. Clinical impact of bacteremia due to Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 11, 6–12. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Lee, A.; Hong, J.; Jo, W.Y.; Cho, O.H.; Kim, S.; Bae, I.G. Staphylococcus saprophyticus bacteremia originating from urinary tract infections: a case report and literature review. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 48(2), 136–139. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.D.; Clarke, A.M.; Anderson, M.E.; Isaac–Renton, J.L.; McLoughlin, M.G. urinary tract infections due to Staphylococcus saprophyticus biotype 3. CMAJ 1981, 124(4), 415–418. [PubMed].

- Golledge, C.L. Staphylococcus saprophyticus bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 157(1), 215. [PubMed].

- Kline, K.A.; Kau, A.L.; Chen, S.L.; Lim, A.; Pinkner, J.S.; Rosch, J.; Nallapareddy, S.R.; Murray, B.E.; Henriques–Normark, B.; Beatty, W.; Caparon, M.G.; Hultgren, S.J. Characterization of a novel murine model of Staphylococcus saprophyticus urinary tract infection reveals roles for Ss pans Sdrl in virulence. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78(5), 1943–1951. [CrossRef].

- Hedman, P.; Ringertz, O.; Lindström, M.; Olsson, K. The origin of Staphylococcus saprophyticus from cattle and pigs. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 25(1), 57–60. [CrossRef].

- Hedman, P.; Ringertz, O.; Erksson, B.; Kvarnfors, P., Andersson, M.; Bengtsson, L.; Olsson, K. Staphylococcus saprophyticus found to be a common contaminant of food. J. Infect. 1990, 21(1), 11–19. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Penna, B.; Varges, R.; Martins, R.; Martins, G.; Lilenbaum, W. In vitro antimicrobial resistance of staphylococci isolated from canine urinary tract infection. Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51(7), 738–742. [PubMed].

- Hauschild, T.; Wójcik, A. Species distribution and properties of staphylococci from canine dermatitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2007, 82(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Mossakowski, P.; Lew–Kojrys, S. Nietypowy rodzaj kamieni moczowych u psa – węglan apatytu. Mag. Wet. 2023; 11.

- Guo, C.; Sun, W.; Cheng, W.; Chen, N.; Lv, Y. Isolation and characterization of Staphylococcus saprophyticus responsible for the death of two six–banded armadillos (Euphractus sexcinctus). Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 2024, 12(1). [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Miszczak, M.; Korzeniowska–Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Gamian, A.; Rypuła, K.; Bierowiec, K. Colonization of methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus species in healthy and sick pets: prevalence and risk factors. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19(1), 85. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Kloos, W.E.; Bannerman, T.L. Update on clinical significance of coagulase–negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 7(1), 117–140. [PubMed].

- Huebner, J.; Goldmann, D.A. Coagulase–negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999, 50, 223–236. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Schulin, T.; Voss, A. Coagulase–negative staphylococci as a cause of infections related to intravascular prosthetic devices: limitations of present therapy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2001, 7($), 1–7. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Giormezis, N.; Kolonitsiou, F.; Foka, A.; Drougka, E.; Liakopoulos, A.; Makri, A.; Papanastasiou, A.D.; Vogiatzi, A.; Dimitriou, G.; Marangos, M.; Christofidou, M.; Anastassiou, E.D.; Petinaki, E.; Spiliopoulou, I. Coagulase–negative staphylococcal bloodstream and prosthetic–device–associated infections: the role of biofilm formation and distribution of adhesion and toxin genes. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63(11), 1500–1508. [CrossRef].

- May, L.; Klein, E.Y.; Rothman, R.E.; Laxminarayan, R. Trends in antibiotic resistance in coagulase–negative staphylococci in the United States 199 to 2012. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58(3), 1404–1409. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Marincola, G.; Liong, O.; Schoen, C.; Abouelfetouh, A.; Hamdy, A.; Wencker, F.D.R.; Marciniak, T.; Becker, K.; Köck, R.; Ziebuhr, W. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of coagulase–negative staphylococci in community–based healthy individuals in Germany. Fron. Public Health 2021, 9, 684456. [CrossRef].

- Otto, M. Coagulase–negative staphylococci as reservoir of genes facilitating MRSA infection. Bioessays. 2012, 19, 35(1), 4–11. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.S.; Lai, L.C.; Chen, Y.A.; Lin, K.Y.; Chou, Y.H.; Chen, H.C.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, J.T.; Chang, S.C. Colonization with multidrug–resistant organism among healthy adults in the community setting: prevalence, risk factors, and composition of gut microbiome. Fron. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1402. [CrossRef].

- Diop, M.; Bassoum, O.; Ndong, A.; Wone, F.; Tamouh, A.G.; Ndoye, M.; Youbong, T.; Daffé, S.M.M.; Radji, R.O.; Gueye, M.W.; Lakhe, N.A.; Fall, B.; Ba, P.S.; Faye, A. Prevalence of multidrug–resistant bacteria in healthcare and community settings in West Africa: systematic review and meta–analysis. BMC Infectious Disease. 2025, 292. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Cristino, J.A.; Pereira, A.T.; Andrade, L.G. Diversity of plasmids in Staphylococcus saprophyticus from urinary tract infections ion woman. Epidemiol. Infect. 1989, 102(3), 413–419. [PubMed].

- Vickers, A.A.; Chopra, I.; O’Neill, A.J. Intrinsic novobiocin resistance in Staphylococcuus saprophyticus. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2007, 51(12), 4484–4485. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- De Pavia–Santos, W.; Barros, E.M.; Santos de Sousa, V.; Silva Laport, M.; Giambiagi–deMarval, M. Identification of coagulase–negative Staphylococcus saprophyticus by PCR based on the heat–shock repressor encoding hrcA gene. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 86(3), 253–256. [PubMed].

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Method for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, 10th ed.; CLSI Document M07–Ed10; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Suseptibility Test for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 7th ed.; CLSI Supplement VET01S; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Marques, C.; Belas, A.; Franco, A.; Aboim, C.; Telo Gama, L.; Pomba, C. Increase in antimicrobial resistance and emergence of major international high–risk clonal lineages in dogs and cats with urinary tract infection: 16 year retrospective study. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18(1), 1–12. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Widerström, M.; Wiström, J.; Sjöstedt, A.; Monsen, T. Coagulase–negative staphylococci: update on the molecular epidemiology and clinical presentation with a focus on Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31(7), 1699–1704. [PubMed].

- Cunha, M.L.R.S.; Sinzato, Y.K.; Silveira, L.V.A. Comparsion of methods for the identification of coagulase–negative staphylococci. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2004, 99(8), 855–860. [CrossRef].

- Kleeman, K.T.; Bannerman, T.L. Evaluation of the Vitek System Gram–positive identification card for species identification of coagulase–negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31(5), 1322–1325. [PubMed].

- Mlaga, K.D.; Dubourg, G.; Abat, C.; Chaudet, H.; Lotte, L.; Diene, S.M.; Raoult, D.; Ruimy, R.; Rolain, J.m. Using MALDI TOF MS typing method to decipher outbreak: the case of Staphylococcus saprophyticus causing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in Marseille, France. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2331 2338. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Leyssene, D.; Chacornac, J.P.; Kostrzewa, M.; Schmit, P.O.; Talon, R.; Bonnet, R.; Delmas, J. Identification of a variety of Staphylococcus species by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48(3), 941 945. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Potter, R.F.; Marino, J.; Muenks, C.E.; Lammers, M.G.; Dien B.J.; Dingle, T.C.; Humphries, R.; Westblade, L.F.; Burnham, C.A.D.; Dantas, G. Comparative genomics reveals the correlations of stress response genes and bacteriophages in developing antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus saprophyticus. mSystem. 2023, 8(6). [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Youngblom, M.A.; imhoff, M.R.; Smyth, L.M.; Mohamed, M.A.; Pepperell, C.S. Portrait of a generalist bacterium: pathoadaptation, metabolic specialization and extreme environments shape diversity of Staphylococcus saprophyticus. bioRxiv. 2023. [CrossRef].

- Lawal, O.U.; Fraqueza, M.J.; Bouchami, O.; Worning, P.; Bartels, M.D.; Gonçalves, M.L.; Paixão, P.; Gonçalves, E.; Toscano, C.; Empel, J.; Urbaś, M.; Domínguez, M.A.; Westh, H.; de Lancastre, H.; Miragaia, M. Foodborne origin and local and global spread of Staphylococcus saprophyticus causing human urinary tract infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 880 893. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.S.; Rabello, R.F.; Dias, R.C.S.; Martins, I.S.; Santos, L.B;G.S.; Alves, E.M.; Riley, L.W.; Moreira, B.M. Time based distribution of Staphylococcus saprophyticus pulsed field gel electrophoresis clusters in community acquired urinary tract infections. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2013, 108(1), 73 76. [CrossRef].

- Rafiee, M.; Tabarraei, A.; Yazdi, M.; Mohebbi, A.; Ghaemi, E.A. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolates causing urinary tract infections in Gorgan, North of Iran. Med. Lab. J. 2023, 17(2), 33 38. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Haadi, S.; Khan, F.A.; Shakir, J.; Shafiq, M.; Tariq, S.; Ahmad, J.; Afzal, Q.; Khan, A.A.; Afridi, P. Antibiotic susceptibility profile of Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolated from clinical samples in Peshawar, Pakistan. The Sciencetech. 2023, 4(1), 75-80. [CrossRef].

- Marepalli, N.R.; Nadipelli, A.R.; Jain, M.K.; Parnam, L.S.; Vashyani, A. Antibiotic resistance in urinary tract infections: a retrospective observational study. Cureus. 2024. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Bonesso, M.F.; Mondelli, A.L.; Camargo, C.H.; Cunha, M.L.R.S. Oxacillin resistance and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Chemotherapy. 2002, 48, 267-270. [CrossRef].

- Chambers, H.F. The changing epidemiology of staphylococcus aureus? Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7(2):178–182. [CrossRef].

- Lee, B.; Jeong, D.W.; Lee, J.H. Genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus saprophyticus from fermented foods and clinical samples. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2015, 58, 659–668. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.Y.L.; Yang, M.; Wong, L.; Knox, J.; Lee, L.Y. Antimicrobial resistance and its detection in Staphylococcus saprophyticus urinary isolates. Pathology 2023, 55, 1013–016. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, F.J.; Theis, S.; Fluit, A.C.; Verhoef, J.; Heinz, H.P.; Jones, M.E. Antimicrobial susceptibility of coagulase–negative staphylococci isolated between 1991 and 1996 from a German university hospital. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 1999, 5(7), 436–439. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Katayama, Y.; Matsuo, M.; Sasaki, T.; Morimoto, Y.; Sekiguchi, A.; Baba, T. Multi-drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and future chemotherapy. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20(10):593–601 [ PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Archer, N.K.; Mazaitis, M.J.; Costerton, J.W.; Leid, J.G.; Powers, M.E.; Shirtliff, M.E. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation and roles in human disease. Virulence. 2011, 2(5), 445–459. [PubMed].

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence profiles of staphylococci from clinical bovine mastitis in Ningxia Hui autonomous region of China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2023, 14. [CrossRef].

- Amiri, R.; Alipour, M.; Engasi, A.K.; Amiri, A.R.; Mofarrah, R. Monitoring and investigation of resistance genes gyrA, parC, blaZ, ermA, ermB and ermC in Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolated from urinary tract infections in mazandaran province, Iran. Infect. Epidemiol. Microbiol. 2023, 9, 117–125. [CrossRef].

- Yang, Y.; Hu, X/; Cai, S.; Hu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mi. J.; Liao, X. Pet cats may shape the antibiotic resistome of their owner’s gut and living environment. Microbiome 2023, 11, 235. [ PubMed ]. [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Schwarz, S.; Lloyd, D.H. Pet animals are reservoirs of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Review. J. Antimicrob. Chemotherapy. 2004, 54(2), 321–332. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Yazdankhah, S.P.; Asli, A.W.; Sorum, H.; Oppegaard, H.; Sunde, M. Fusidic acid resistance, mediated by fusB in bovine coagulase–negative staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58(6), 1254–1256. [CrossRef].

- Patel, J.B.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Jernigan, J.A. Mupirocin resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49(6), 935–941. [CrossRef ].

- Doudoulakakis, A.; Spiliopoulou, I.; Spyridis, N.; Tsabouri, S.; Ntziora, F.; Pana, Z.D.; Michail, G. Emergence of a Staphylococcus aureus clone resistant to mupirocin and fusidic acid carrying exotoxin genes and causing mainly skin infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55(8), 2529–2535. [CrossRef].

- Tsai, C.J.Y.; Loh, J.M.S.; Proft, T. Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence. 2016, 7(3), 214–229. [CrossRef].

- Koksal, F.; Yasar, H.; Samasti, M. Antibiotic resistance patterns of coagulase–negative Staphylococcus strains isolated from blood cultures of septicemic patients in Turkey. Microbiological Research. 2009, 164(4), 404–420. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Bierowiec, K.; Korzeniowska–Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Rypuła, K.; Gamian, A. Prevalence of Staphylococcus species colonization in healthy and sick cats. Biomed Res int. 2019. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Samad, R.; Al Disi, Z.; Mohammad Ashfaq, M.Y.; Wahib, S.M.; Zouari, N. The use of principle component analysis and MALDI-TOF MS for the differentiation of mineral forming Virgibacillus and Bacillus species isolated from sabkhas. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14606–14616. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Amini, R.; As, A.; Chung, C.; Jahanshiri, F.; Wong, C.B.; Poyling, B.; Hematian, A.; Sekawi, Z.; Zargar, M.; Jalilian, F.A. Circulation and transmission of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among college students in Malaysia (cell phones as reservoir). Asian Biomedicine. 2012, 6(5), 659–673.

- Ullah, F.; Malik, S.A.; Ahmed, J.; Ullah, F.; Shah, S.M.; Ayaz, M.; Hussain, S.; Khatoon, L. Investigation of the genetic basis of tetracycline resistance in staphylococcus aureus from Pakistan. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 2012, 11(6), 925–931. [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.; Solhjoo, K.; Norooz–Nejad, M.J.; Kazemi, A. VanA and VanB positive vancomycin resistant staphylococcus aureus among clinical isolates in shiraz, south iran. Oman Med J. 2014, 29(5), 335–339. [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Ciesielczuk, H.; Xenophontos, M.; Lambourne, J. Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus harboring mecC still eludes us in east London, united Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol. 2019, 57(6). [PubMed].

- O’neill, A.; Chopra, I. Molecular basis of fusB mediated resistance to fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Molecular Microbiology. 2006, 59(2), 664–676. [CrossRef].

- Tasara, T.; Cernela, N.; Stephan, R. Function impairing mutations in blaZ and blaR genes of penicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis. Veterinary Microbiology. 2017, 211, 52–56. [CrossRef]

- Płoneczka-Janeczko K, Bierowiec K, Lis P, Rypuła K. Identification of bap and icaA genes involved in biofilm formation in coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from feline conjunctiva. Vet Res Commun. 2014;38(4). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4231282/ [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobial agent tested | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | AMP | AMC | MUP | P | FD | MAR | CIP | OX | LZD | DA | E | C | RD | CN | SXT | TGC | TET |

| Healthy humans (n=14) |

7 (50.0%) |

2 (14.29%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (35.71%) |

4 (28.57%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (42.86%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (7.14%) |

7 (50.0%) |

2 (14.29%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Sick humans (n=7) |

3 (42.86%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

3 (42.86%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

3 (42.86%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (57.14%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

| Healthy cats (n=29) |

6 (20.69%) |

2 (6.9%) |

2 (6.9%) |

7 (24.14%) |

5 (17.24%) |

2 (6.9%) |

4 (13.79%) |

9 (31.03%) |

1 (3.45%) |

3 (10.34%) |

9 (31.03%) |

2 (6.9%) |

1 (3.45%) |

2 (6.9%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (17.24%) |

| Sick cats (n=3) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (33.33%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (66.66%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (33.33%) |

1 (33.33%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (33.3%) |

| Healthy dogs (n=1) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Sick dogs (n=7) |

1 (14.29%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (28.57%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (85.71%) |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (42.86%) |

7 (100.0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

| All (n=61) |

17 (27.87%) |

4 (6.56%) |

2 (3.28%) |

13 (21.31%) |

15 (24.59%) |

3 (4.92%) |

5 (8.20%) |

26 (42.62%) |

1 (1.64%) |

9 (14.75%) |

29 (47.54%) |

5 (8.20%) |

1 (1.64%) |

3 (4.92%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (1.64%) |

8 (13.11%) |

| Antimicrobial resistance gene tested | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | blaZ | mecA | mecC | aac* | ermA | ermB | ermC | tetK | tetL | tetM | tetO | fusB | vanA | vanB | mupA |

| Healthy humans(n=14) |

14 (100%) |

14 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

13 (92.86%) |

13 (92,86%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

10 (71.43%) |

14 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (7,14%) |

0 (0%) |

| Sick humans(n=7) |

7 (100%) |

7 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

6 (85,71%) |

4 (57.14%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

7 (100%) |

7 (100%) |

2 (28,57%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Healthy cats(n=29) |

29 (100%) |

29 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

4 (13.79%) |

25 (86,21%) |

20 (68,97%) |

4 (13,79%) |

0 (0%) |

8 (27.59%) |

28 (96.55%) |

5 (17.24%) |

4 (13.79%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (6,9%) |

| Sick cats(n=3) |

3 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (100%) |

1 (33,3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (66.67%) |

3 (100%) |

1 (33.33%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Healthy dogs(n=1) |

1 (100%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Sick dogs(n=7) |

7 (100%) |

7 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

6 (85,71%) |

3 (42,86%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

5 (71.43%) |

7 (100%) |

1 (14.29%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (14.29%) |

0 (0%) |

|

All (n=61) |

61 (100.0%) |

61 (100%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (6.56%) |

54 (88.52%) |

41 (67.21%) |

4 (6.56%) |

0 (0%) |

32 (52.46%) |

60 (98.36%) |

11 (18.03%) |

4 (6.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (3.28%) |

2 (3.28%) |

| Groups | No data |

Oral cavity |

Nostrils | Anus | Wound | Skin |

Ear canal |

Conjunctival sac |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthy humans Sick humans Healthy cats Sick cats Healthy dogs Sick dogs |

0 5 0 0 0 0 |

2 0 2 0 0 0 |

4 1 6 3 0 1 |

0 0 2 0 0 0 |

0 0 0 0 0 1 |

4 1 6 0 0 0 |

4 0 5 0 0 2 |

0 0 8 0 1 3 |

14 7 29 3 1 7 |

| All | 5 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).