Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes chronic infections in humans and animals, especially cats and dogs. This bacterium's ability to adapt and acquire antibiotic resistance traits may complicate and exacerbate antibacterial therapy. This study aimed to evaluate the antibiotic resistance patterns, virulence factors and ability to form biofilm of P. aeruginosa strains isolated from Algerian dogs and cats. Methods: Nineteen samples were collected from healthy and diseased dogs and cats. Isolates were studied for their antibiotic resistance patterns (disc diffusion method), biofilm formation (Microtiter assay) and were Whole genome sequenced (MinION). Results: Nineteen P. aeruginosa strains (15 from dogs and 4 from cats) were isolated. Antibiotic resistance phenotypes were observed against amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (100%), meanwhile resistance towards ticarcillin was 40% (dogs) and 25% (cats), ticarcillin-clavulanic acid was 13.33% and 25% for dogs and cats respectively and imipenem was 75% (cats) and 20% (dogs). 95% of strains were biofilm producers. Different antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) were found: beta-lactamase genes mainly PAO, OXA-494, OXA-50 and OXA-396, aminoglycosides gene (aph(3’)-IIb), fosA for fosfomycin and catB7 for phenicol. The main high risk STs were ST244, 2788, 388 and 1247. A large panel of virulence genes was detected: exoS, exoT, exoY, lasA, toxA, prpL, algD, rhIA and others. Conclusions: The genetic variety in antibiotic resistance genes of resistant and virulent P. aeruginosa strains in dogs makes public health protection difficult. Continuous monitoring and research in compliance with the One Health policy are needed to solve this problem.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Population Information

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Biofilm Formation

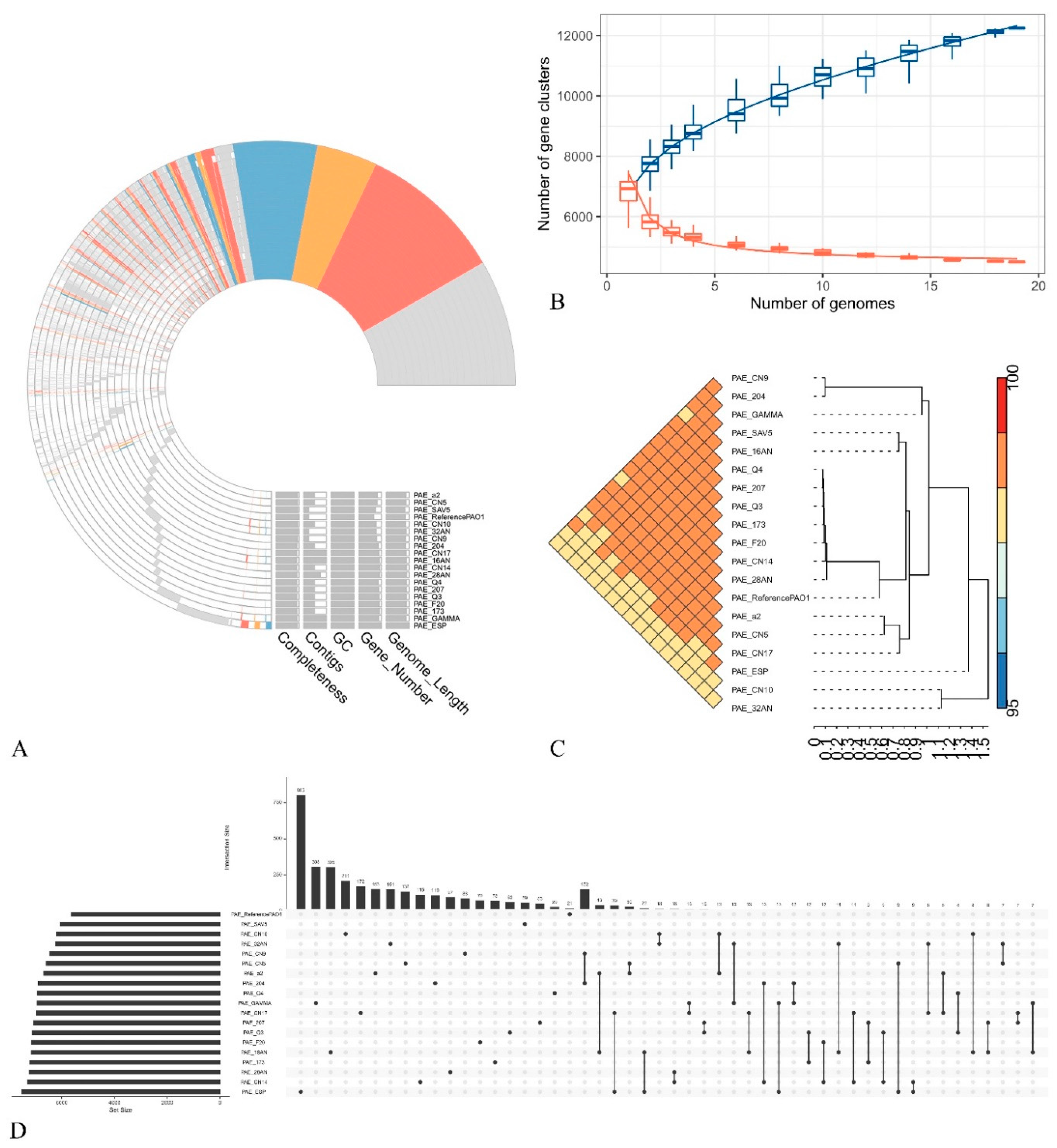

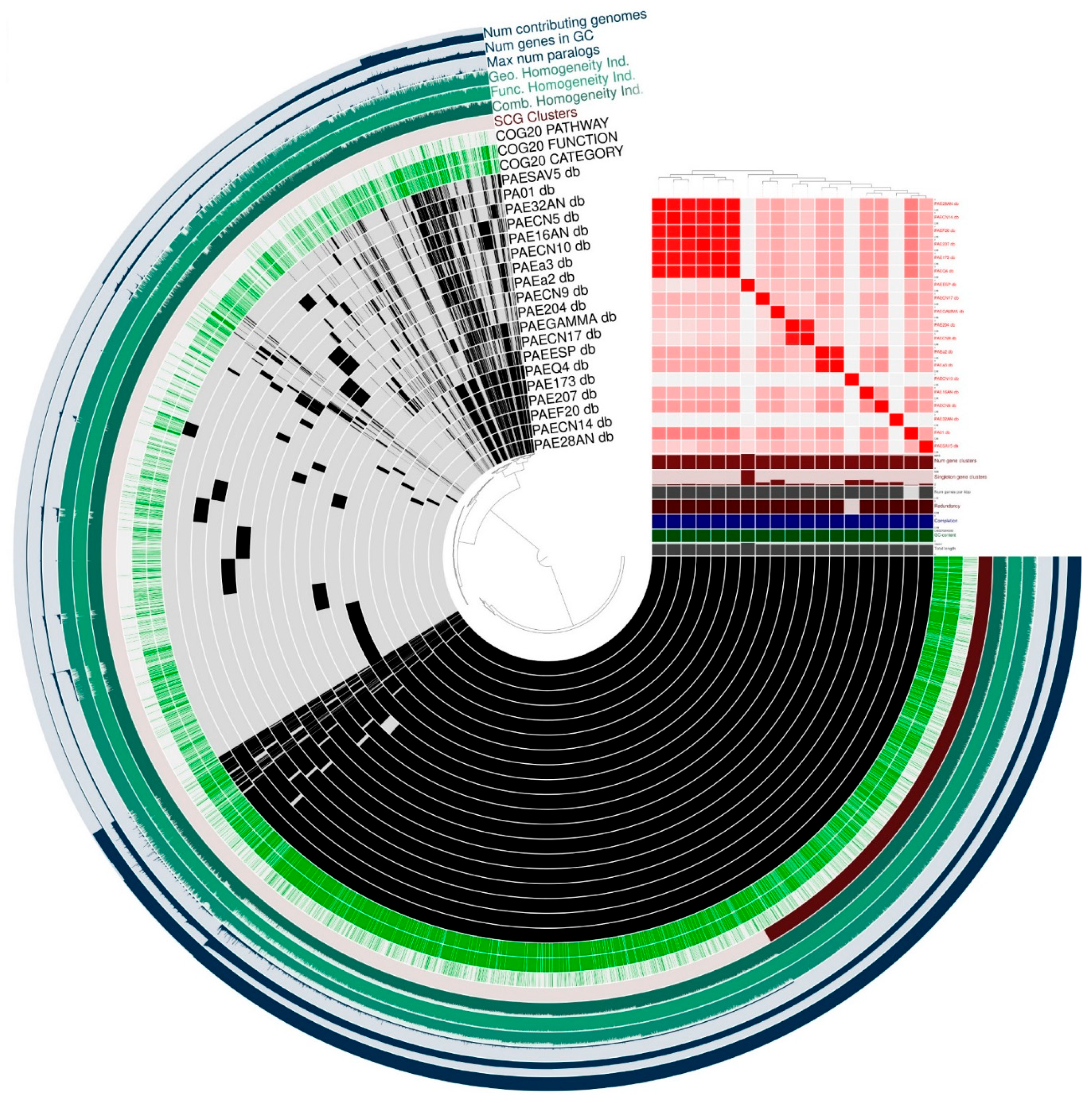

2.3. General Features of the Genomes

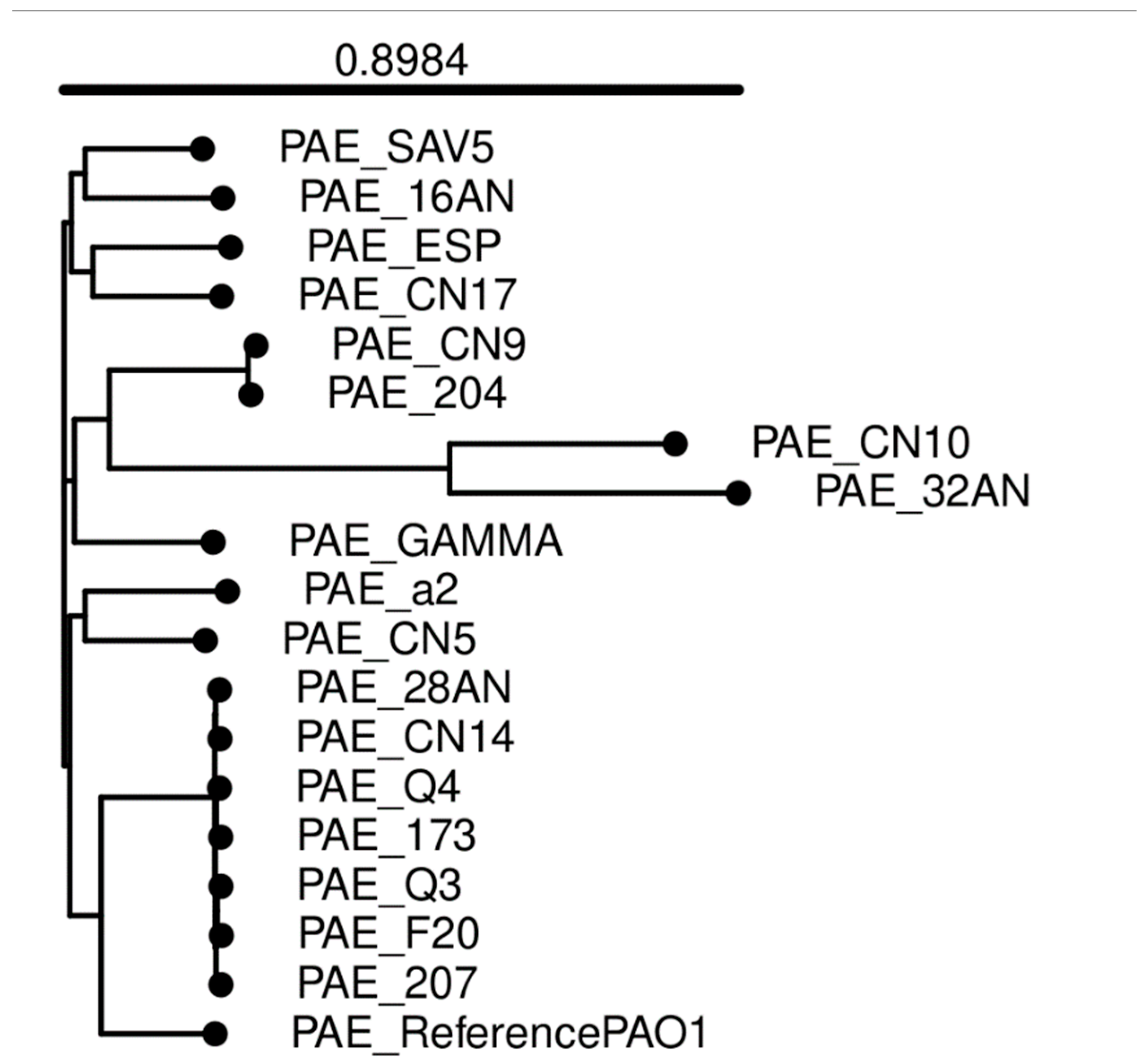

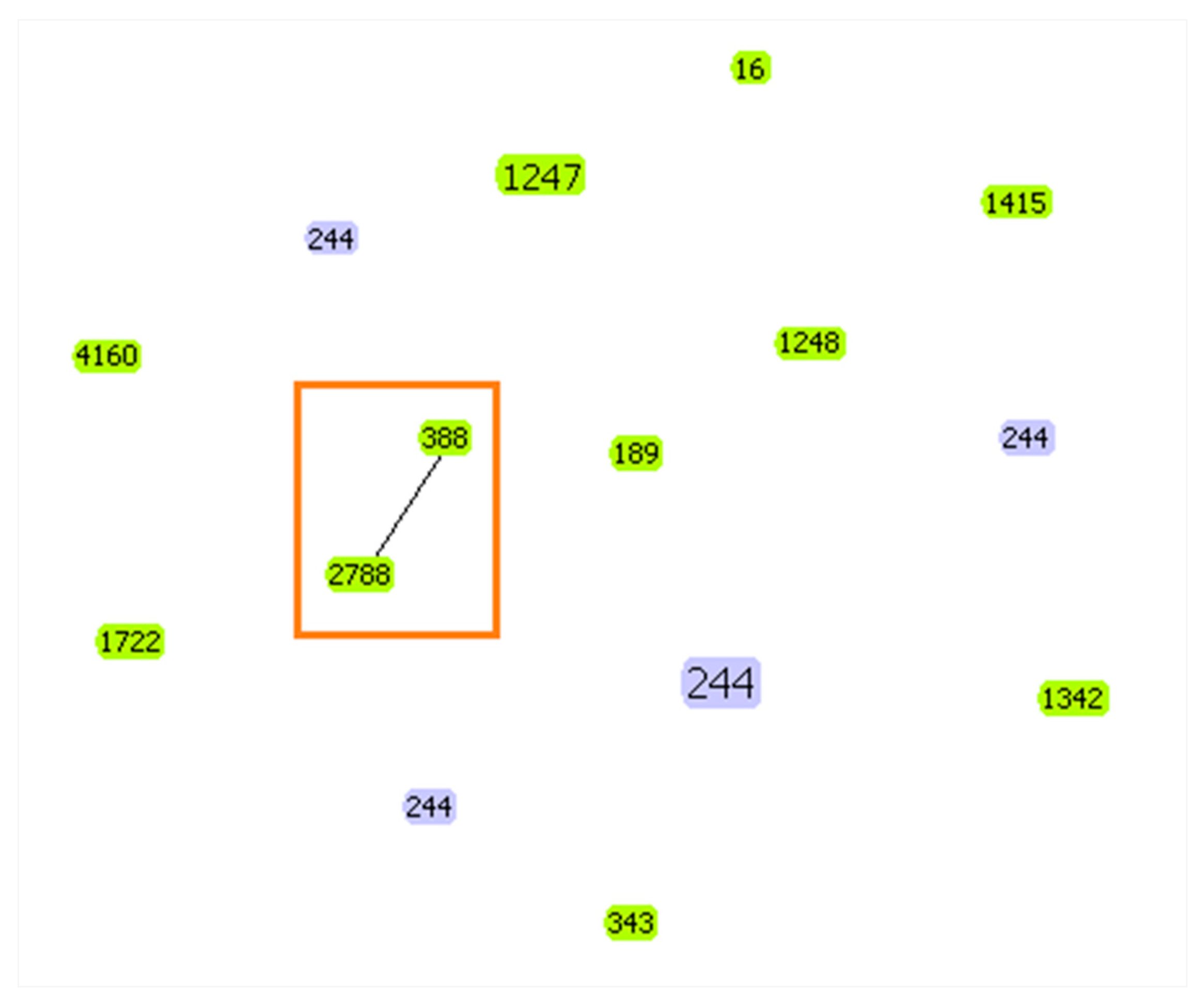

2.4. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

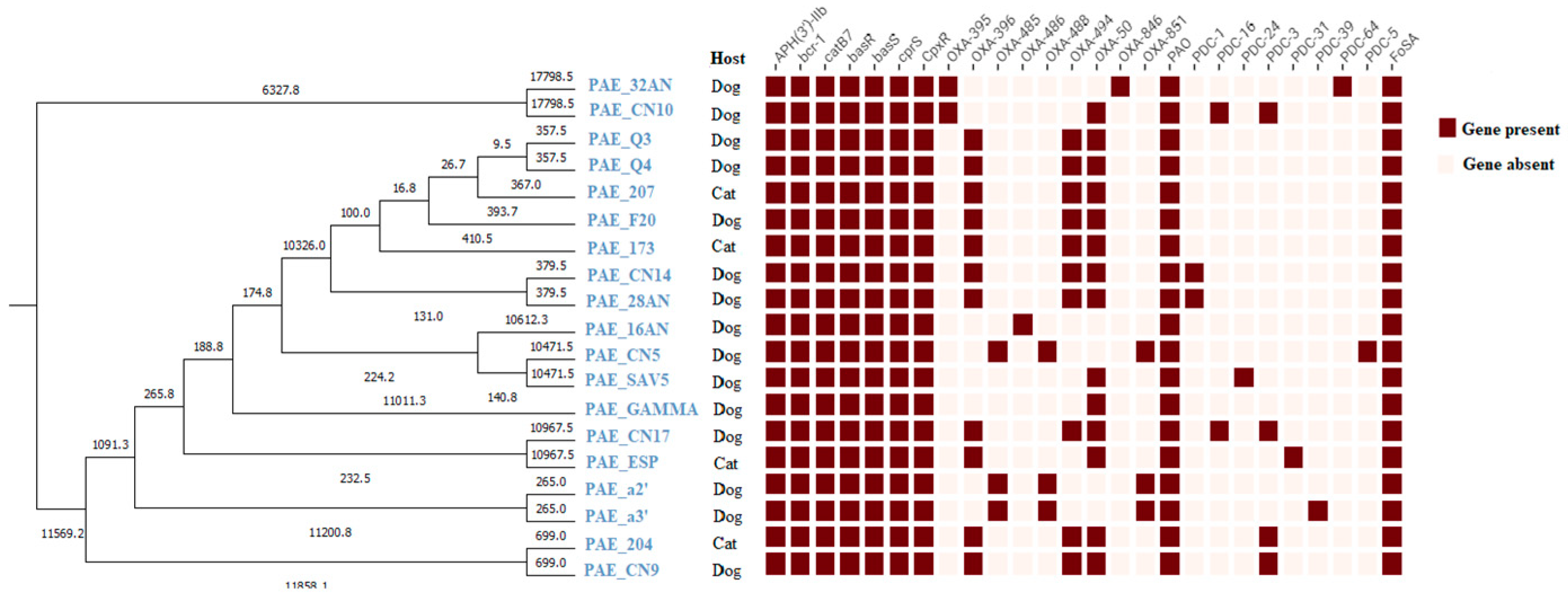

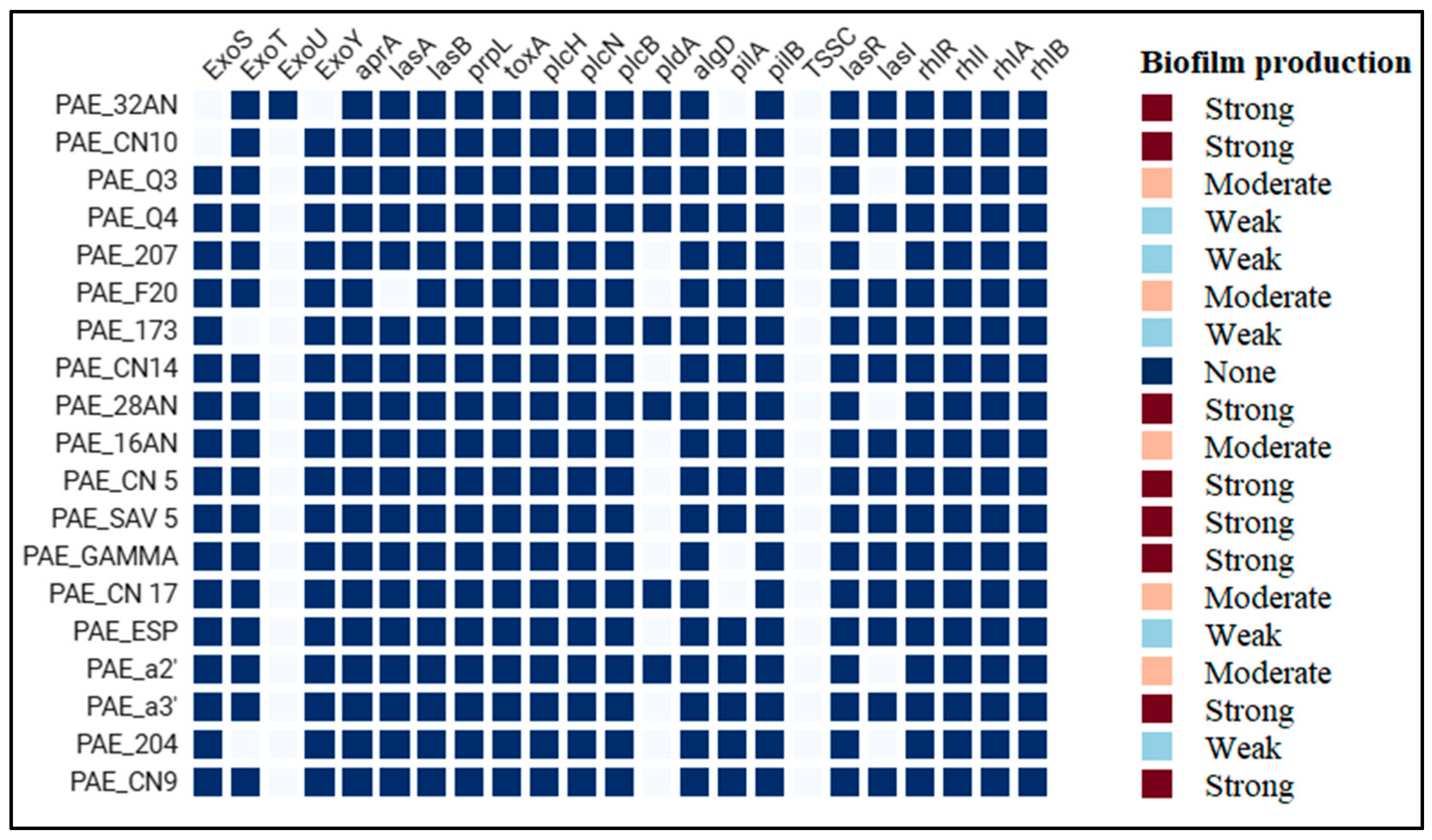

2.5. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

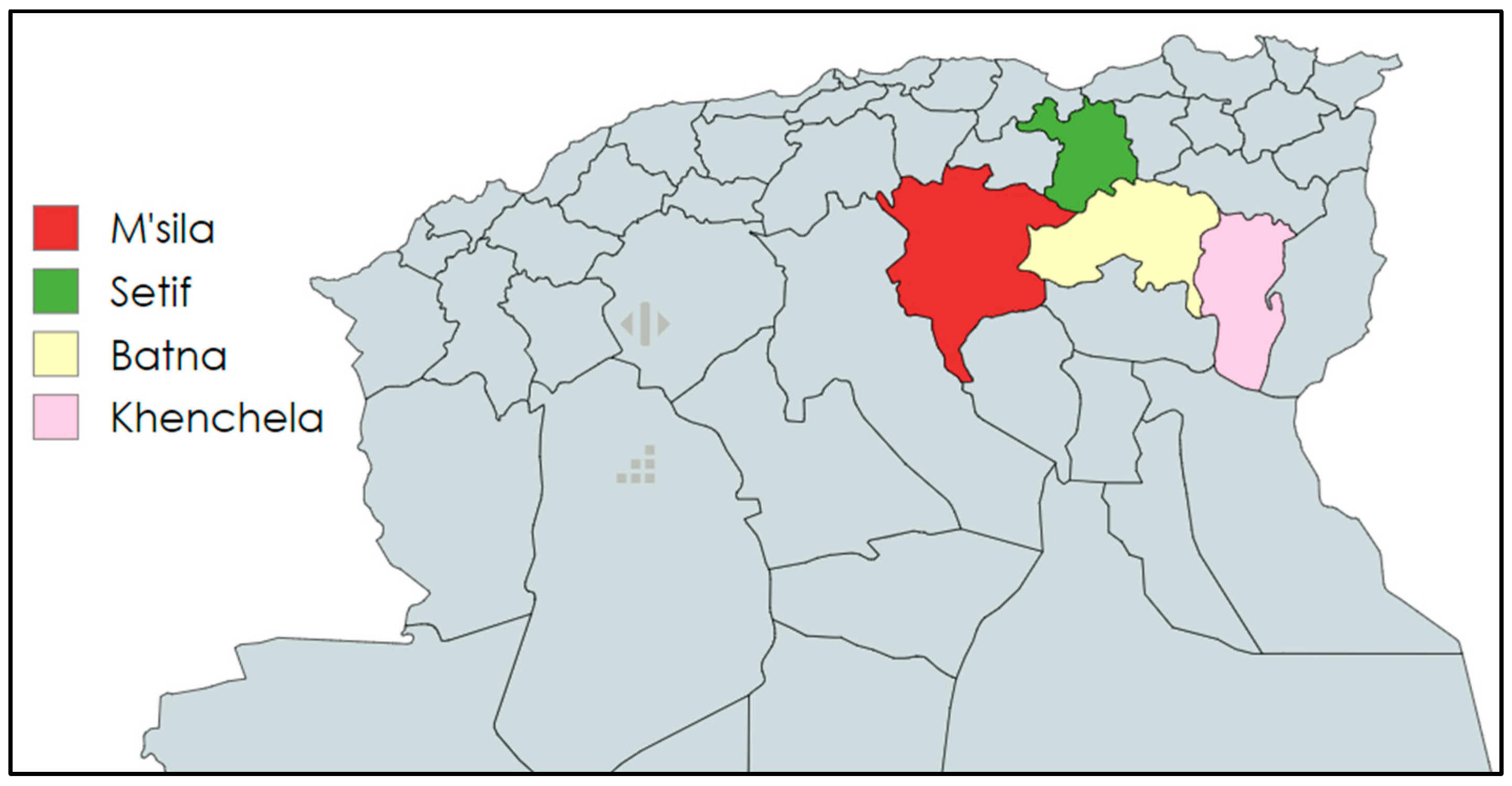

4.1. Population’s Study and Sample Collection

4.2. Culture Conditions and Bacterial Identification

4.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.4. In Vitro Biofilm Formation Assay

4.5. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Bioinformatics Analysis

4.5.1. DNA Extraction

4.5.2. Whole Genome Sequencing

4.5.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.5.4. Bioinformatic Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakamura, K.; Fujiki, J.; Furusawa, T.; Nakamura, T.; Gondaira, S.; Sasaki, M.; Usui, M.; Higuchi, H.; Sawa, H.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Veterinary Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolate, Pa12. Microbiol Resour Announc 2021, 10, e0039821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.S.; Allbaugh, R.A.; Kenne, D.E.; Sebbag, L. Prevalence and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Bacterial Isolates From Dogs With Ulcerative Keratitis in Midwestern United States. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 583965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-M.; Nam, H.-S.; Woo, H.-M. Successful Management of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Pneumonia after Kidney Transplantation in a Dog. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, K.; Leeper, H.; O’Reilly, K.; Jacob, J.; Bermudez, L.E. An Analysis of the Infections and Determination of Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Cats and Dogs with Cancer-Associated Infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenni, M.; Hocquet, D.; Ponsin, C.; Cholley, P.; Guyeux, C.; Madec, J.-Y.; Bertrand, X. Population Structure and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa from Animal Infections in France. BMC Veterinary Research 2015, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, A.; Youala, M.; El Garch, F.; Simjee, S.; Rose, M.; Morrissey, I.; Moyaert, H. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Monitoring of Canine and Feline Skin and Ear Pathogens Isolated from European Veterinary Clinics: Results of the ComPath Surveillance Programme. Vet Dermatol 2020, 31, 431-e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, K.; Fothergill, J.L.; Storrar, J.; Ledson, M.J.; Winstanley, C.; Walshaw, M.J. Transmission of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Epidemic Strain from a Patient with Cystic Fibrosis to a Pet Cat. Thorax 2008, 63, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Petersen-Jones, S.M. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Bacteria Isolated from Cats with Ulcerative Keratitis in Taiwan. J Small Anim Pract 2008, 49, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlandas-Quintana, E.A.; Martinez-Ledesma, J.E. Detection of Carbapenems Resistant K-Mer Sequences in Bacteria of Critical Priority by the World Health Organization (Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Acinetobacter Baumannii). In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS); December 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Santaniello, A.; Sansone, M.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Occurrence of ESKAPE Bacteria Group in Dogs, and the Related Zoonotic Risk in Animal-Assisted Therapy, and in Animal-Assisted Activity in the Health Context. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW); Nielsen, S.S.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Canali, E.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Gortázar, C.; Herskin, M.; et al. Assessment of Listing and Categorisation of Animal Diseases within the Framework of the Animal Health Law (Regulation (EU) No 2016/429): Antimicrobial-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Dogs and Cats. EFSA Journal 2022, 20, e07310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veetilvalappil, V.V.; Manuel, A.; Aranjani, J.M.; Tawale, R.; Koteshwara, A. Pathogenic Arsenal of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: An Update on Virulence Factors. Future Microbiol 2022, 17, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursina, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Fazeli, F.; Ariaii, P. Assessment of Virulence Factors and Antimicrobial Resistance among the Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated from Animal Meat and Carcass Samples. Vet Med Sci 2022, 9, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart-Boroń, A.; Stankiewicz, K.; Czernecka, N.; Ratajewicz, A.; Bulanda, K.; Heliasz, M.; Sosińska, D.; Dworak, K.; Ciesielska, D.; Siemińska, I.; et al. Wounds of Companion Animals as a Habitat of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria That Are Potentially Harmful to Humans-Phenotypic, Proteomic and Molecular Detection. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Schwarz, S.; Lloyd, D.H. Pet Animals as Reservoirs of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004, 54, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breidenstein, E.B.M.; de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Hancock, R.E.W. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: All Roads Lead to Resistance. Trends Microbiol 2011, 19, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ganiny, A.M.; Shaker, G.H.; Aboelazm, A.A.; El-Dash, H.A. Prevention of Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Soft Contact Lenses Using Natural Compounds. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 2017, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yao, D.; Lu, W. Virulence Factors of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Antivirulence Strategies to Combat Its Drug Resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, G.; Sun, D.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Shi, W.; Ma, J. IPGA: A Handy Integrated Prokaryotes Genome and Pan-Genome Analysis Web Service. Imeta 2022, 1, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A.P.; Bugalho, M.; Ramirez, M.; Carriço, J.A. Global Optimal eBURST Analysis of Multilocus Typing Data Using a Graphic Matroid Approach. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płókarz, D.; Czopowicz, M.; Bierowiec, K.; Rypuła, K. Virulence Genes as Markers for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Formation in Dogs and Cats. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda, P.; Sanz-García, F.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Martínez, J.L. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: An Antibiotic Resilient Pathogen with Environmental Origin. Curr Opin Microbiol 2021, 64, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, A.M.; Elsayed, M.M.; Abd El Tawab, A.A.; Elhofy, F.I.; Soliman, E.A.; Kozytska, T.; Brangsch, H.; Sprague, L.D.; Neubauer, H.; Wareth, G. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Resistance and Virulence in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Poultry Farms in Egypt Using Whole Genome Sequencing. Vet Microbiol 2024, 292, 110063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattab, J.; Mosca, F.; Di Francesco, C.E.; Aste, G.; Marruchella, G.; Guardiani, P.; Tiscar, P.G. Occurrence, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Pathogenic Factors of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Canine Clinical Samples. Vet World 2021, 14, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, S.A.; Abdalshheed, D.A. Detection of Virulence Factors of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa from Dog’s Wound Infections by Using Biochemical and Molecular Methods. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husbandry 2023, 8, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangsangthong, A.; Lugsomya, K.; Apiratwarrasakul, S.; Phumthanakorn, N. Distribution of Sequence Types and Antimicrobial Resistance of Clinical Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates from Dogs and Cats Visiting a Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Thailand. BMC Veterinary Research 2024, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Foley, S.L.; Qi, Y.; Han, J.; Ji, C.; Li, R.; Wu, C.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y. Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Canine Infections. J Appl Microbiol 2012, 113, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Epstein, S.E.; Westropp, J.L. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns in Urinary Tract Infections in Dogs (2010-2013). J Vet Intern Med 2015, 29, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankar, S.; Thresia; Bosewell, A.; Mini, M. Molecular Detection of Carbapenem Resistant Gram Negative Bacterial Isolates from Dogs. Indian Journal of Animal Research 2021.

- Dégi, J.; Moțco, O.-A.; Dégi, D.M.; Suici, T.; Mareș, M.; Imre, K.; Cristina, R.T. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profile of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Canine Isolates from a Multicentric Study in Romania. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Oh, J.; Park, S.; Sum, S.; Song, W.; Chae, J.; Park, H. Antimicrobial Resistance and Novel Mutations Detected in the gyrA and parC Genes of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated from Companion Dogs. BMC Veterinary Research 2020, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, B.; Thomé, S.; Martins, R.; Martins, G.; Lilenbaum, W. In Vitro Antimicrobial Resistance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Canine Otitis Externa in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Microbiol 2011, 42, 1434–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, F.; Turba, M.E.; Pasquali, F.; Mion, D.; Romagnoli, N.; Zambon, E.; Terni, D.; Peirano, G.; Pitout, J.D.D.; Parisi, A.; et al. Hospitalized Pets as a Source of Carbapenem-Resistance. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel Hadj Ahmed, A.; Salah Abbassi, M.; Rojo-Bezares, B.; Ruiz-Roldán, L.; Dhahri, R.; Mehri, I.; Sáenz, Y.; Hassen, A. Characterization of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Various Environmental Niches: New STs and Occurrence of Antibiotic Susceptible “High-Risk Clones”. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2020, 30, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, B.; Moustafa, S.; Shata, R.; Sayed-Ahmed, M.Z.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Ali, M.S.; Alam, N.; Ahmad, S.; Kasem, N.; Elbaz, E.; et al. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Dairy Cattle, Milk, Environment, and Workers’ Hands. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, A.; Isla, A.; Rodríguez-Gascón, A.; Canut, A.; Ángeles Solinís, M. Susceptibility of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Antimicrobial Activity Using PK/PD Analysis: An 18-Year Surveillance Study. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed) 2019, 37, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feßler, A.T.; Scholtzek, A.D.; Schug, A.R.; Kohn, B.; Weingart, C.; Hanke, D.; Schink, A.-K.; Bethe, A.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial and Biocide Resistance among Canine and Feline Enterococcus Faecalis, Enterococcus Faecium, Escherichia Coli, Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter Baumannii Isolates from Diagnostic Submissions. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Walker, R.D.; Blickenstaff, K.; Bodeis-Jones, S.; Zhao, S. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Characterization of Fluoroquinolone Resistance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Canine Infections. Vet Microbiol 2008, 131, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgenedy, E.M.; Abdelmoein, K.A.; Samir, A. Occurrence of Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms among Pet Animals Suffering from Respiratory Illness: A Possible Public Health Risk. Veterinary Medical Journal (Giza) 2024, 70, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellera, F.P.; Da Silva, L.C.B.A.; Lincopan, N. Rapid Spread of Critical Priority Carbapenemase-Producing Pathogens in Companion Animals: A One Health Challenge for a Post-Pandemic World. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021, 76, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castillo, F.Y.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L.; Avelar-González, F.J. An Overview of Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms from Food-Producing Animals, Seafood, Aquaculture, Companion Animals, and Wildlife. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossouvi, K.M.; Ametepe, A.S. Carbapenem Resistance in Animal-Environment-Food from Africa: A Systematic Review, Recommendations and Perspectives. Infect Drug Resist 2024, 17, 1699–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, M.; Touati, A.; Mairi, A.; Brasme, L.; Gharout-Sait, A.; Guillard, T.; De Champs, C. Emergence of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia Coli Isolated from Companion Animals in Algeria. Microb Drug Resist 2016, 22, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousfi, M.; Touati, A.; Muggeo, A.; Mira, B.; Asma, B.; Brasme, L.; Guillard, T.; de Champs, C. Clonal Dissemination of OXA-48-Producing Enterobacter Cloacae Isolates from Companion Animals in Algeria. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018, 12, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfadadny, A.; Uchiyama, J.; Goto, K.; Imanishi, I.; Ragab, R.F.; Nageeb, W.M.; Iyori, K.; Toyoda, Y.; Tsukui, T.; Ide, K.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genotyping of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from the Ear Canals of Dogs in Japan. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.; Garcês, A.; Silva, A.; Lopes, R.; Alegria, N.; Hébraud, M.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. The Impact of the Virulence of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Dogs. Veterinary Sciences 2023, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.T.; Cunha, M.V.; Ferreira, H.; Fonseca, C.; Palmeira, J.D. A High-Risk Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clone Detected in Red Deer (Cervus Elaphus) from Portugal. Sci Total Environ 2022, 829, 154699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Lu, L.; He, L.; Yan, G.; Lu, G.; Zhai, X.; Wang, C. Non-Carbapenem-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Children: Risk Factors, Molecular Epidemiology, and Resistance Mechanism. J Infect Public Health 2025, 18, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, N.-H.; Jang, K.-M.; Jin, H.; Shin, K.; Jeong, B.C.; Kim, D.-W.; Lee, S.H. Prioritization of Critical Factors for Surveillance of the Dissemination of Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio-Tofiño, E.; López-Causapé, C.; Oliver, A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Epidemic High-Risk Clones and Their Association with Horizontally-Acquired β-Lactamases: 2020 Update. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 56, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, J.; Sevillano, G.; Solís, M.B.; Paz Y Miño, A.; Alves, B.R.; Changuan, J.; González, P. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Epidemic High-Risk Clones and Their Association with Multidrug-Resistant. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2024, 38, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, N.; Klockgether, J.; Tümmler, B. Microevolution of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in the Airways of People with Cystic Fibrosis. Curr Opin Immunol 2023, 83, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Mulet, X.; López-Causapé, C.; Juan, C. The Increasing Threat of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa High-Risk Clones. Drug Resist Updat 2015, 21–22, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellouk, F.Z.; Bakour, S.; Meradji, S.; Al-Bayssari, C.; Bentakouk, M.C.; Zouyed, F.; Djahoudi, A.; Boutefnouchet, N.; Rolain, J.M. First Detection of VIM-4-Producing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Northeastern (Annaba, Skikda) Algeria. Microb Drug Resist 2017, 23, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merradi, M.; Kassah-Laouar, A.; Ayachi, A.; Heleili, N.; Menasria, T.; Hocquet, D.; Cholley, P.; Sauget, M. Occurrence of VIM-4 Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in an Algerian Hospital. J Infect Dev Ctries 2019, 13, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Rojo-Molinero, E.; Arca-Suarez, J.; Beşli, Y.; Bogaerts, P.; Cantón, R.; Cimen, C.; Croughs, P.D.; Denis, O.; Giske, C.G.; et al. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles, Resistance Mechanisms and International Clonal Lineages: Update from ESGARS-ESCMID/ISARPAE Group. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2024, 30, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, F.; Snesrud, E.; Hall, L.; Mills, E.; Galac, M.; Stam, J.; Ong, A.; Maybank, R.; Kwak, Y.I.; Johnson, S.; et al. A Panel of Diverse Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates for Research and Development. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2021, 3, dlab179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, P.D.; Wolter, D.J.; Hanson, N.D. Antibacterial-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Clinical Impact and Complex Regulation of Chromosomally Encoded Resistance Mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009, 22, 582–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, B.; Gulyás, D.; Szabó, D. Diversity and Distribution of Resistance Markers in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa International High-Risk Clones. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Bogaerts, P.; Girlich, D.; Huang, T.-D.; Dortet, L.; Glupczynski, Y.; Naas, T. Molecular Characterization of OXA-198 Carbapenemase-Producing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e02496-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, R.P.; Ma, H.; Casas, E.; Lippolis, J.D. Genome Sequence of a Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strain Isolated from a Dairy Cow That Was Nonresponsive to Antibiotic Treatment. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2023, 12, e00289-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaha, E.L.; Mienie, C.; Gonsu, H.K.; Bughe, R.N.; Fonkoua, M.C.; Mbacham, W.F.; Alayande, K.A.; Bezuidenhout, C.C.; Ateba, C.N. Whole-Genome Sequence of Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains UY1PSABAL and UY1PSABAL2 Isolated from Human Broncho-Alveolar Lavage, Yaoundé, Cameroon. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0238390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, L.M.; Turnbull, L.; Katrib, M.; Osvath, S.R.; Losa, D.; Lazenby, J.J.; Whitchurch, C.B. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Is Capable of Natural Transformation in Biofilms. Microbiology (Reading) 2020, 166, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, W.; Izumi, K.; Yoshida, S.; Takizawa, S.; Sakaguchi, K.; Iyori, K.; Minoshima, K.-I.; Takano, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Nagano, Y.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Type III Secretion System Virulotypes of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates from Dogs and Cats in Primary Veterinary Hospitals in Japan: Identification of the International High-Risk Clone Sequence Type 235. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9, e0040821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.; Peña, C.; Oliver, A. Host and Pathogen Biomarkers for Severe Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infections. J Infect Dis 2017, 215, S44–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassuna, N.A.; Mandour, S.A.; Mohamed, E.S. Virulence Constitution of Multi-Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Upper Egypt. Infect Drug Resist 2020, 13, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltman, H.; Schulert, G.; Khan, S.; Jain, M.; Peterson, L.; Hauser, A.R. Prevalence of Type III Secretion Genes in Clinical and Environmental Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microbiology 2001, 147, 2659–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Martín, I.; Sainz-Mejías, M.; McClean, S. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: An Audacious Pathogen with an Adaptable Arsenal of Virulence Factors. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martínez, J.; Rocha-Gracia, R.D.C.; Bello-López, E.; Cevallos, M.A.; Castañeda-Lucio, M.; Sáenz, Y.; Jiménez-Flores, G.; Cortés-Cortés, G.; López-García, A.; Lozano-Zarain, P. Comparative Genomics of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated from Different Ecological Niches. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Espinosa, R.; Delgado, G.; Espinosa-Camacho, F.; Flores-Alanis, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Mendez, J.L.; Gonzalez-Pedraza, A.; Cravioto, A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated from Animal with High Virulence Genes Content and Highly Sensitive to Antimicrobials. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2024, 37, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, P.; Hada, V.; Rath, R.S.; Mohanty, A.; Singh, P.; Rukadikar, A. Interpretation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Using European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Breakpoints: Analysis of Agreement. Cureus 2023, 15, e36977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.A. Microtiter Dish Biofilm Formation Assay. J Vis Exp 2011, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: Population-Scale Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wick, R. Rrwick/Filtlong 2025.

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of Long, Error-Prone Reads Using Repeat Graphs. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanoporetech/Medaka 2025.

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the Quality of Microbial Genomes Recovered from Isolates, Single Cells, and Metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncbi/Pgap 2025.

- Eren, A.M.; Kiefl, E.; Shaiber, A.; Veseli, I.; Miller, S.E.; Schechter, M.S.; Fink, I.; Pan, J.N.; Yousef, M.; Fogarty, E.C.; et al. Community-Led, Integrated, Reproducible Multi-Omics with Anvi’o. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Tseemann/Abricate 2025.

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Haft, D.H.; Prasad, A.B.; Slotta, D.J.; Tolstoy, I.; Tyson, G.H.; Zhao, S.; Hsu, C.-H.; McDermott, P.F.; et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e00483-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Raphenya, A.R.; Alcock, B.; Waglechner, N.; Guo, P.; Tsang, K.K.; Lago, B.A.; Dave, B.M.; Pereira, S.; Sharma, A.N.; et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and Model-Centric Curation of the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D566–D573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Padmanabhan, B.R.; Diene, S.M.; Lopez-Rojas, R.; Kempf, M.; Landraud, L.; Rolain, J.-M. ARG-ANNOT, a New Bioinformatic Tool to Discover Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bacterial Genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and Refined Dataset for Big Data Analysis--10 Years On. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doster, E.; Lakin, S.M.; Dean, C.J.; Wolfe, C.; Young, J.G.; Boucher, C.; Belk, K.E.; Noyes, N.R.; Morley, P.S. MEGARes 2.0: A Database for Classification of Antimicrobial Drug, Biocide and Metal Resistance Determinants in Metagenomic Sequence Data. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, D561–D569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolate ID | Animal | Sex | Breed | Age (month) | Sampling source |

| PAE 1 | dog | M | German shepherd | 3 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 2 | dog | M | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 3 | dog | M | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 4 | dog | F | German shepherd | 4 | middle ear |

| PAE 5 | dog | M | German shepherd | 6 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 6 | dog | M | na | 12 | rectum |

| PAE 7 | dog | M | Malinois | 12 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 8 | dog | M | German shepherd | 48 | middle ear |

| PAE 9 | dog | M | Malinois | 18 | middle ear |

| PAE 10 | dog | M | Malinois | 18 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 11 | dog | F | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 12 | dog | M | German shepherd | 4 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 13 | dog | M | Poodle | 8 | middle ear |

| PAE 14 | dog | M | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 15 | dog | F | Crossbred | 48 | nasal cavity |

| PAE 16 | cat | na | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 17 | cat | na | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 18 | cat | F | na | na | rectum |

| PAE 19 | cat | M | na | na | rectum |

| Dogs | Cats | p-value | |||

| Antibiotic | R | S | R | S | |

| Amoxicilin-clavulanic acid (AMC) | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | 0 | - |

| Ticarcillin (TC) | 40 (6) | 60 (9) | 25 (1) | 75 (3) | 0.1 |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid (TCC) | 13,33 (2) | 87(13) | 25 (1) | 75 (3) | 0.530 |

| Cefepim (FEP) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Ceftazidime (CAZ) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Aztreonam (ATM) | 6,6 (1) | 60 | 0 | 75 (3) | 1 |

| Imipenem (IMP) | 20 (3) | 67 | 75 (3) | 25(1) | 0.303 |

| Levofloxacin (LEV) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 75 (3) | 0.2 |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Netilmicin (NET) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Tobramicin (TOB) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Gentamicin (CN) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 100 (4) | - |

| Amikacin (AK) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 75 (3) | 0.211 |

| ID | BioSample Accession | Genome Accession | Comp | Cont | Cov | Contig N50 (bp) | Genome Size (bp) | GC (%) | Contigs | Assembly level |

| PAE_16AN | SAMN43392783 | CP169763 | 98.28 | 1.84 | 186 | 6532852 | 6532852 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_173 | SAMN43392795 | CP169759 | 96.06 | 2.29 | 151 | 6605328 | 6605328 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_204 | SAMN43392797 | CP169760 | 90.89 | 4.27 | 116 | 6366466 | 6366466 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_207 | SAMN43392796 | CP169762 | 93.97 | 2.5 | 114 | 6602785 | 6602785 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_28AN | SAMN43392793 | JBHGZY000000000 | 96.02 | 1.64 | 161 | 6594872 | 6661963 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_32AN | SAMN43392779 | CP169765 | 99.94 | 0.46 | 63 | 6465512 | 6465512 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_a2 | SAMN43392790 | CP169758 | 94.75 | 2.82 | 86 | 6443410 | 6443410 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_a3 | SAMN43392782 | JBHHAE000000000 | 95.94 | 0.95 | 92 | 4124627 | 6542771 | 66 | 5 | Contig |

| PAE_CN10 | SAMN43392780 | JBHHAG000000000 | 99.35 | 1.69 | 70 | 6314619 | 6410152 | 66 | 3 | Contig |

| PAE_CN14 | SAMN43392792 | JBHGZX000000000 | 92.72 | 1.4 | 178 | 6593826 | 6691624 | 66 | 3 | Contig |

| PAE_CN17 | SAMN43392789 | JBHHAC000000000 | 93.18 | 3.98 | 148 | 6510536 | 6570451 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_CN5 | SAMN43392784 | CP169761 | 93.96 | 1.27 | 91 | 6430499 | 6430499 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

| PAE_CN9 | SAMN43392781 | JBHHAF000000000 | 90.65 | 3.41 | 38 | 6365670 | 6382583 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_ESP | SAMN43392794 | JBHHAD000000000 | 99.57 | 2.1 | 171 | 6755612 | 7332217 | 66 | 3 | Contig |

| PAE_F20 | SAMN43392791 | JBHHAB000000000 | 95.06 | 2.26 | 136 | 6596684 | 6701622 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_GAMMA | SAMN43392785 | JBHHAA000000000 | 95.31 | 1.79 | 136 | 6358597 | 6483109 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_Q3 | SAMN43392788 | JBHGZW000000000 | 93.33 | 0.75 | 133 | 3680952 | 6608695 | 66 | 5 | Contig |

| PAE_Q4 | SAMN43392787 | JBHGZZ000000000 | 94.82 | 1.78 | 137 | 6564132 | 6615011 | 66 | 2 | Contig |

| PAE_SAV5 | SAMN43392786 | CP169764 | 95.11 | 1.52 | 78 | 6211070 | 6211070 | 66 | 1 | Chromosome |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).